ABSTRACT

Is Covid-19 undermining European democracies? Recent scholarship overlooks the fact that most pandemic-related erosions of democracy can be attributed to illiberal inertia long in place before 2019. Did the democratic decay occur during the pandemic or due to the pandemic? We analyse the extent to which pandemic power grabs succeeded and failed in Europe with special attention to the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia. The executive power of the purse was an opportunity to abuse state resources. Governments that engage in the “pandemic heist” with impunity can be directly linked to a power grab due to the pandemic.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic eroded democracy worldwide (Coppedge et al. Citation2021) and followed a trend of democratic deterioration in the twenty-first century.Footnote1 Democratic quality decreased in established and new democracies as countries faced dual challenges of public health crisis and economic stagnation. Many rights were violated during the pandemic, such as restrictions of movement, association and business freedoms (NIT Citation2022). At the same time, institutional checks and balances eroded, civic engagement and press freedoms were limited, and opportunities for executive aggrandizement were expanded (Edgell et al. Citation2020; Guasti Citation2020). In overall, established democracies were largely immune to pandemic backsliding when compared to democracies in transitions. However, a set of new and older democracies decayed during the pandemic (Edgell et al. Citation2021; Engler et al. 2021).

Pandemics strengthen governments, weaken parliaments and test the judiciary (Petrov Citation2020). When the health care system and the economy are at the brink of collapse and executives cling to power, democracies become vulnerable. (Maerz et al. Citation2020; Petrov Citation2020). As institutional safeguards are pressured by the executive, the diversity of the public forum is reduced (Afsahi et al. Citation2020). A pandemic is a stress test: liberal democracy remains resilient during a pandemic only when mechanisms of horizontal and diagonal accountability can avert efforts to erode democratic institutions – the opposition, courts and the civil society must hold governments in check. A pandemic is an opportunity to consolidate and even expand power (Aktürk and Lika Citation2022; Guasti Citation2020; Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020; Guasti and Bilek Citation2021; Marinov and Popova Citation2021).

Is Covid-19 undermining European democracies? And if so, how? Is there a causal link between the pandemic and democratic decay? Recent scholarship on the political effects of the coronavirus crisis overlooks the fact that most pandemic-related erosions of democracy are continuations of previous trends. Did the democratic decay occur during the pandemic or due to the pandemic? We show that many efforts to undermine formal institutions and accountability linkages occurred during the pandemic, not due to it, and erosion of pluralism during the pandemic can be attributed to illiberal inertia that has already been initiated before 2019.

We analyze the extent to which pandemic power grabs succeeded and failed in Europe. We pay special attention to changes in executive dominance in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia and show that civic activism is a necessary, but not a satisfactory condition for democratic resilience. We suggest that corruption, the “pandemic heist,” is a pathway to link opportunities created by the pandemic to power grabs. The distribution of pandemic relief funds can be used to reward loyalists and to weaken political opponents. As such, it is a power grab due to the pandemic.

This paper is structured as follows. We discuss the literature on pandemic democratic erosion with special attention to horizontal and diagonal accountability as safeguard mechanisms. The analytical part proceeds in three parts. First, we analyze backsliding during the pandemic. Assaults on formal institutions were rare and often met with resistance. Furthermore, we conclude that they were mostly continuations of pre-pandemic trends. Second, we identify markers of backsliding that can be attributed to the pandemic, and we find almost none. Third, we suggest that the executive discretion over the “pandemic purse” is a new opportunity for executive power grabs. We conclude with suggestions on how to study democratic erosion directly attributable to the Covid-19 crisis.

Pandemic distortions of democratic accountability

Accountability constraints the use of power (Lindberg, Citation2013) and comprises of three components: horizontal, vertical, and diagonal. Vertical accountability centres on the relationship between voters and elected representatives mediated via elections. Horizontal accountability accounts for the balance of power between institutions, such as parliaments and courts. Diagonal accountability covers the extent to which media and civil society hold governments accountable (Bernhard et al., Citation2020; Weyland Citation2020). Vertical accountability can erode with the imposition of limits on electoral competition. Horizontal accountability can be distorted due to the executive overreach that undermines legislative oversight and judicial independence. Diagonal accountability is distorted by limits imposed on civil society and the media.

All forms of accountability can erode and the erosion of accountability has a deleterious influence on democracy (Ruth Citation2018; Ruth-Lovell, Lührmann, and Grahn Citation2019). In countries where elections took place during the pandemic, vertical accountability has eroded if it disproportionately advantaged incumbents in campaigning (Pirro and Stanley Citation2022). Horizontal accountability was undermined by efforts to weaken institutional safeguards (cf. Bermeo Citation2016), by attempts to delay the adaptation of laws by the legislatures (Cormacain and Bar-Siman-Tov Citation2020), and by efforts to slow down the courts (Petrov Citation2020). Diagonal accountability was undermined when limits were placed on core civil liberties and freedoms, including protest and association, and by governments’ lack of transparency vis-à-vis the media (Habersaat et al. Citation2020; Edgell et al. Citation2020; Guasti Citation2020).

Core civil rights and liberties were suspended during the pandemic states of emergency (Engler et al. Citation2021). Some (populist) governments instrumentalized pandemic restrictions to push through new policies, laws, regulations, or held elections to supervisory boards that would – in a non-pandemic context – have resulted in a backlash by civil society (Guasti Citation2020). Emergency powers also gave leaders the ability to bypass checks and balances and eroded horizontal accountability. Accountability deteriorated more in countries where institutional guardrails were weaker, and backsliding was already ongoing (Lührmann et al. 2020; Engler et al. Citation2021; Edgell et al. Citation2021). Sebhatu et al. (Citation2020) found that democratic countries were slower to react and initiated lockdowns and school closures with delays (cf. Cheibub, Jean Hong, and Przeworski Citation2020). Edgell et al. (Citation2021) have shown that infringement of the media was the most common violation during the pandemic.

The distortions of accountability during the pandemic are therefore well documented. However, they omit two important issues. First, the accounts of pandemic distortions do not differentiate between erosions of accountability during and due to the pandemic. Second, violations of accountability are mostly depicted in the domain of formal institutions. This overlooks the role of informal norms and practices, as well as the emergence of opportunities associated with increased state spending. When urgency and accelerated speed of public procurement limit oversight, financial valves open up for executives. Covid-19 gave rise to new opportunities to allocate resources, to increase spending, and reward loyalists with government contracts (cf. Gallego, Prem, and Vargas Citation2020). In order to understand executive power grabs, we should turn towards the study of the pandemic political economy and less institutionalized pathways to amass resources that facilitate power expansions.

In our analysis, we rely on multiple sources of data, mostly the V-Dem project (Coppedge et al. Citation2021) to identify changes in liberal democratic scores and the degree of pandemic backsliding. We pay close attention to changes in media and we rely on widely available indices as well as country reports that describe changes in the media landscape in the past ten years. In the last analytical section of the paper, we use multiple country reports from Transparency International, Freedom House Reports (NIT) and Bertelsmann Foundation reports, as well as area expertise, to identify sources of accountability distortions associated with the pandemic.

Democratic decay during the pandemic

The pandemic was eventful for many illiberal leaders in Eastern Europe. In the spring of 2022, parliamentary elections were held in Hungary and Poland. Viktor Orbán scored a major victory, but Slovenian voters ousted Janez Janša. Whereas presidential elections in Poland afforded Duda and PiS to achieve a narrow victory by exploiting incumbency benefits during the pandemic, voters in Slovakia rejected corrupt SMER in 2020 right before the onset of the pandemic. In Bulgaria, the populist GERB narrowly lost power in the spring of 2021, and the Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš and ANO were defeated in the general elections in October 2021. Moreover, since 2018, thousands have mobilised for democracy, the rule of law, and media freedoms across the region (e.g. in Poland, Ukraine, Serbia, Czech Republic, Romania, Hungary, and Slovakia). Civic mobilisation and contestation in Central and Eastern Europe are at the highest levels since the fall of communism. These protests reflect the societal demand for democratic governance, transparency, and fairness. A firewall civil society has emerged to fight illiberalism (Bernhard Citation2020).

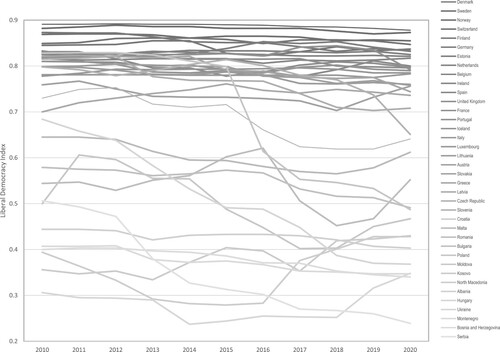

Is there any evidence that European democracies are plummeting during the pandemic? Not really, according to the index of liberal democracy from the V-Dem project (Coppedge et al. Citation2021). plots changes in Liberal Democratic Scores between 2018 and 2021. A negative value indicates an erosion – a decrease of the current liberal democratic score when compared to 2018. The minimum value of the index is 0, the maximum is 1. Therefore, the maximum possible change theoretically ranges from −1 to +1. In general, scores in most countries deteriorated, but the change is negligible. Slovenia, Poland, and Greece deteriorated the most. However, the scores of twelve countries improved, and seven of these countries are in Eastern Europe. Democracies in Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, Malta, and Slovakia improved the most. Yet, most of the improvements are marginal. Overall, the pandemic did not significantly erode or improve democracies.

Figure 1. Changes in Liberal Democratic Scores between 2018 and 2021. Note: The countries are sorted according to their liberal democratic scores in 2018 from highest to lowest. The change (blue bars) is calculated as a change between 2021–2018. Negative values stand for deterioration, positive values indicate improvements in liberal democratic scores. Source: V-Dem, March 2022. Version 12.

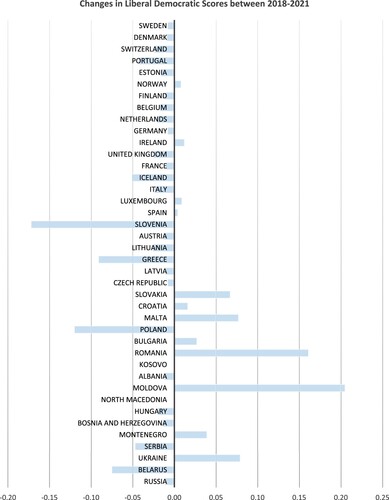

Figure A1 (in the Appendix) plots a decade of trends of liberal democracy in Europe. Most countries either stayed at their pre-pandemic levels of liberal democracy or followed a trajectory set into motion well before the pandemic. There are no ruptures in the indices and there is little evidence of decay. A few countries deviated from path dependency as some democracies slightly decayed, but others improved. Between 2018 and 2021, the quality of liberal democracy declined in Slovenia, Poland, Portugal, Greece, and Serbia in 2020, but their democratic decline was modest. At the same time, during the pandemic, Croatia, Malta, Slovakia, Moldova, Ukraine and Romania improved their liberal democracy scores. Yet, these improvements were also modest and of equal magnitude to the magnitude of decay in the first group of countries. On average, the pandemic is a wash: most countries stayed at their levels of democracy or modestly deviated in both directions.

Despite the observed stability, it is erroneous to conclude that the pandemic has no direct, discernible, effect on the quality of democracy. In order to further examine if Covid-19 harms not only lungs but also democracies, we turn to the index of pandemic violations of democratic standards (). The index of pandemic violations “captures the extent to which state responses to Covid-19 violate democratic standards for emergency responses … It is not intended to measure a level of democracy” (Edgell et al. Citation2020).Footnote2 suggests, however, that there is a relationship between the index of pandemic violations and the quality of democracy.Footnote3 Old democracies, such as Switzerland, are unaffected by Covid-19 while violations flourish in countries with weaker democratic institutions, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina. also shows that pandemic violations do occur but they are not very common. Most European countries fall into the category of “no” or “only minor violations”. Countries with resilient democratic institutions, such as Germany or Finland have no violations and their democratic standards did not suffer during the pandemic.

Table 1. Pandemic Violations of Democratic Standards in Europe (2020–2021).

Major violations are experienced by countries that have already been on a downward trajectory before the pandemic, such as Serbia and Greece. These countries (among others) significantly violated democratic standards during the pandemic. Despite this, during Covid-19, democracy in Greece and Serbia deteriorated only mildly and other countries that violated democratic standards stayed on their pre-pandemic sub-par levels of democracy (). If pandemic violations in Europe are mostly subtle and uncommon in old democracies, countries with middling violations and some democratic infractions are mostly suitable for understanding the mechanics of pandemic-related democratic decay.

The Visegrad Four countries, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, occupy the middle category of minor to some pandemic violations and therefore are more suited for inspection than stable democracies with no infractions, or countries currently undergoing a fast-paced erosion (). These countries share broad similarities in terms of state capacity and levels of development, as well as a political tendency to insulate themselves using tough measures right at the onset of the pandemic (Anghel and Jones Citation2022; Aktürk and Lika Citation2022; Guasti Citation2020). In all four countries, democracy has been eroding for almost half of a decade, but the process of erosion has stabilised (NIT Citation2022). What is the “value-added effect” of the pandemic if the determinants of democratic trajectories are path-dependent? Hypothetically speaking, would countries with illiberal leaders, such as Hungary, continue their decay at the same rate if it was not for the shock of Covid 19?

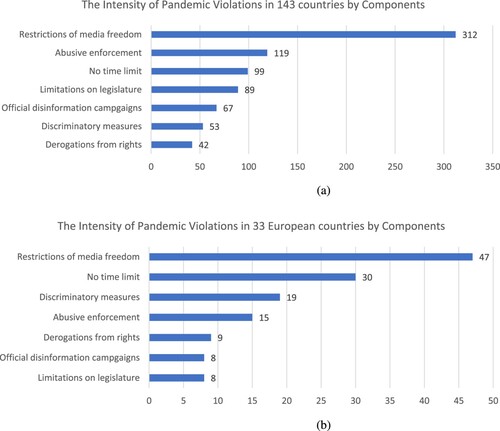

Before we proceed further, we look closer at the specific sources of democratic erosion. A more detailed view allows us to determine whether accountability weakened during the pandemic or due to the pandemic. The pandemic violations index has seven sub-components, one of which is restrictions on media freedoms. Infringements on media freedoms greatly influence the overall index of pandemic violations both in Europe and worldwide. (a,b) deconstruct the index to its components to show that media violations are a substantial driver of the index. It is important to note that the pandemic violations index is only supposed to capture media violations “attributable” to the pandemic.

Figure 2. (a) The intensity of Pandemic Violations in 143 Countries by Sub-components. Minimum: 0 (no violations in 143 countries). Maximum: 3*143 (major violations in 143 countries) in a single component. The value of 492 would therefore mean that there were “major” media violations in all 143 countries. Coded as no violation = 0. Minor violations = 1. Some violations = 2. Major violations = 3. Source: Source: V Dem (index deconstructed by authors). (b) The intensity of Pandemic Violations in 33 European Countries by Sub-components. Minimum: 0 (no violations in 33 countries). Maximum: 3*33 (major violations in 33 countries) in a single component. The value of 99 would therefore mean that there were "major" media violations in all 33 countries. Source: V Dem (index deconstructed by authors).

However, media violations are path dependent and not always easily attributable to the pandemic. For example, in Italy, Poland, Greece and Ukraine, media freedoms are coded as having experienced major pandemic violations. This coding greatly influences the overall index, since other infringements are typically less severe. Media infringements in Ukraine illuminate the dilemma of attributing media decay, and therefore democratic erosion, to Covid-19. Ukraine is coded by V-dem as having no pandemic violations on five components, one minor violation on discriminatory measures and major violations on restrictions of media.Footnote4 A closer read of the pandemic violations coding narrative shows that, despite the fact that, according to the coders, “media freedoms were not affected by the emergency measures”, the index component suggests that government limited access of media due to the Covid-19 related measures. For example, independent media were not allowed to attend municipal council meetings in Kryvyi Rih and Kakhovka. These actions resulted in harsh coding of restrictions of media and, in overall, put Ukraine into a category of pandemic backsliding. Independent media in Ukraine struggled to access government information even before the pandemic (Dovbysh and Lehtisaari Citation2020), but the logic of the index attributes media violations to the pandemic. The coders noted that the overall status quo of media freedoms was preserved, which contradicts the underlying logic of the coding.

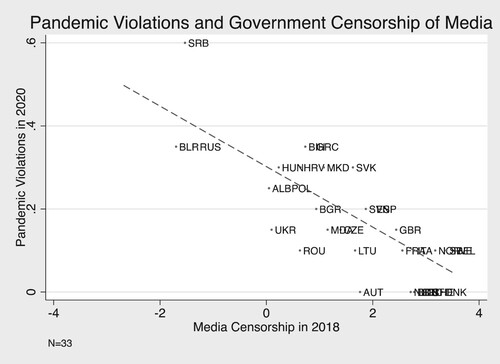

Media freedoms have been deteriorating in the past decade globally, mirroring negative trends in trajectories of liberal democracies. The same path dependency that we observed with respect to the quality of democracy applies to media as well.Footnote5 shows that government censorship before the pandemic (2018) is a robust predictor of pandemic violations. It suggests that media freedom violations merely reflect the relationship between governments and media established before the crisis. Therefore, a practice of past government media abuse and censorship results in a lack of transparency and overall poor performance in the pandemic. Violations of media freedoms, a major driver of an index of pandemic backsliding, are only loosely related to the pandemic, if at all.

Figure 3. Government Censorship of Media and Pandemic Violations in Europe (2020–2021). Data Source: V-Dem.

The relationship between media, governments and transparency raises the following question: How to differentiate between decay that happened during the pandemic or due to the pandemic? How to identify processes and opportunities that would have not happened otherwise? For example, a legal and temporal suspension of the parliament necessitated by the emergency powers to combat the virus is an opportunity, but not necessarily a pandemic power grab. It becomes a power grab when emergency powers are extended outside the formal institutional guardrails. Pandemic media freedom violations and efforts to curb minority rights are frequently consistent with previous policies put in motion well before the outbreak of the novel coronavirus. For example, the hostile takeover of the regional media network Polska Press by the state giant PKN Orlen (controlled by the ruling party) in preparation of the upcoming elections in 2023 was long in the making in anticipation of electoral contestation.Footnote6 We conclude that diagonal accountability eroded during the pandemic, not due to the pandemic.

Our reasoning in the domain of minority rights is similar. For example, a new law passed in Hungary in 2021 – that bundled protection of children against paedophilia with a ban on exposure to LGBTQ curriculum in schools – was drafted to bait the opposition and the European critics before the spring 2022 elections. The law had two political goals. International critique of the law allows Fidesz to claim victimhood status in the European Union with an argument that it infringes upon Hungarian sovereignty. At the domestic level, tying sexual predation on children with LGBTQ issues creates a trap because Fidesz can frame its political opposition that does not support the law as defenders of child abuse and protectors of paedophiles. Furthermore, policies that targeted sexual minorities have been put into motion before 2019. The law is consistent with the pre-pandemic efforts of Fidesz to create new categories of public enemies to crush political opposition. Therefore, we view it as an effort to restrict minority rights that happened during the pandemic, not due to it.

The pandemic is a handful. It affords politicians with new opportunities because parliaments and state institutions are overwhelmed and distracted. Efforts to diminish rights also follow from the pandemic if a new or controversial law or policy is suddenly and quietly proposed. For example, an unsuccessful attempt to sneak in a restriction of abortion in Slovakia into a health bill in 2020 was a (failed) effort to restrict abortion rights. It also indicates resilience, since an attempt in the parliament was made, but failed (if only by one vote). Footnote7

We now turn to the analysis of democratic decay during the pandemic from the perspective of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal accountability. During the pandemic, vertical accountability declined in Poland (2021) and Hungary (2022). Horizontal accountability declined more broadly in Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia. Diagonal accountability was contested. Polish and Hungarian governments continued with the onslaught on media freedoms. Attacks on free media press were absent in Slovakia and (to a degree) in the Czech Republic (with the caveat regarding the Czech TV). Finally, during the pandemic, civil society was significantly mobilised for democracy in all four countries.

Vertical accountability is associated with free elections as it maps voters’ preferences onto electoral outcomes. Multiple elections took place between 2020 and 2022. In 2022, Hungarian parliamentary elections sealed Fidesz’s power with a big win. The heterogenous opposition could not rally behind its anti-Orban candidate. More importantly, the election was an uphill battle due to severe gerrymandering, state-captured media, pre-electoral state spending on voters by Fidesz and Orban’s skilful manoeuvring between Putin and Brussels in the time of war.Footnote8

In Czechia, the democratic opposition was able to dislodge the ruling party ANO in 2021 in free and fair general elections, as two coalitions – a conservative and a liberal – won a majority in the parliament. This was a significant defeat for a populist leader Andrej Babiš. The parliamentary elections halted democratic decay in Czechia. Czech Republic also held regional and Senate elections in October 2020. The Czech government first proposed to exclude COVID-19 positive and quarantining citizens from participation in the elections. Footnote9 Upon backlash from the opposition, the government changed the course by providing necessary protection to poll workers and introduced drive-thru voting. Compared to previous elections, the turnout in Czechia increased by several percentage points (from 34.5% in 2016 to 38% in 2020).

Slovak democracy slightly improved, because a former ruling party Smer, marred with corruption scandals, lost power in February 2020 general elections, before the onset of Covid-19. The transfer of power was uneventful and did not hinder the pandemic response. In Poland, presidential elections in 2020 were plagued with chaos. The incumbency gave president Duda an advantage over his challengers, whose campaigns were limited by pandemic restrictions, while the incumbent Duda travelled the country.Footnote10 While Duda’s incumbency advantage is unrelated to the pandemic, the restriction on campaigning that weakened the opposition opponents can be directly attributed to the pandemic.

Horizontal accountability was assaulted in all four countries. Orban initially indefinitely suspended the parliament. Poland was immersed in an ongoing struggle over the control of the Constitutional Tribunal. However, the opposition-controlled Upper Chamber (Senate) in Poland and the Czech Republic was able to serve as an effective constrain against attempts to instrumentalize the pandemic. Constitutional Courts in Czechia and Slovakia corrected governments’ overreach – for example, in Czechia, courts pushed against store closures and unconstitutional travel restrictions. In Slovakia, courts limited mobile phone tracking by government bodies.Footnote11 Czech and Slovak Constitutional Courts sought to balance the protection of public health and constitutional principles. They were remarkably resilient. In Hungary and Poland, where the government control over the Constitutional Courts is significantly advanced, the courts were unable and unwilling to constrain the executives.

Diagonal accountability has two major components: civil society and free media. We analyze them separately. During the pandemic, media freedoms declined both in Poland and Hungary, both governments significantly limited media pluralism in 2020 and 2021. In Hungary, the last independent media outlet was closed (Klubradio in February 2021) as its expiring licence was not renewed. Hungary also amended the Authorisation Act, which was adopted to prevent the spread of “misinformation” during a state of emergency.

In Poland, the government-owned PNP ORLEN company purchased a network of regional media Polska Press, printing, and distribution facilities and the largest domestic network on newspaper kiosks (Ruch). Furthermore, in the summer of 2021, the Polish government took on an American-owned private and independent TV station, TVN24, despite a very strong opposition from the US government. The PiS led-government’s objective was to nationalise TVN24 by selling it to a Polish state company.Footnote12 In a raucous meeting in the Lower Chamber, the government succeeded while bending the vote, but the bill was eventually vetoed by President Duda in December 2021.

There were no major attempts to curtail media freedoms in Slovakia. In the Czech Republic, before ANO lost elections in October 2021, the ruling party ANO led by PM Andrej Babiš spearheaded an attack on the independence of the state TV.Footnote13 This effort to tame the TV failed. Furthermore, Czechia has an independent public and private free press capable of counteracting the former Prime Minister’s (now MP) private media empire. During the pandemic, investigative journalists reported preferential treatment of the MAFRA group (owned by Agrofert, a company controlled by the former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš) by state-owned companies such as the Czech Railways. Furthermore, the MAFRA media group benefited significantly more from the relief package for the media and culture.Footnote14 In Czechia, all attempts to undermine formal institutions were subjected to meticulous scrutiny by the courts and failed.

Civil society was very active in all four countries during the pandemic. In the Czech Republic, civil society rallied to provide DIY masks and protection equipment to healthcare professionals and citizens during the first pandemic wave in the spring of 2020. In Slovakia, anti-corruption groups mounted an unsuccessful campaign against the proposed reform of public procurement. However, the government that rose to power on anti-corruption did not engage with civil society once in power.Footnote15

In Poland, civil society is very polarised and mirrors deep political divisions. During the pandemic, civil society mobilised against scapegoating LGBTQ+ groups and in support reproductive rights (more than 400,000 gathered in 410 locations in October 2020), judicial independence, and the rule of law. However, far-right groups disrupted these demonstrations and clashed with the protestors. The government let far-right groups protest with no inhibitions, but enforced Covid-19 restrictions vis-à-vis anti-government protesters (cf. Bernhard Citation2021).Footnote16

Similarly, in Hungary, while the government curtailed the rights to assembly due to the pandemic, major anti-Roma demonstrations by far-right groups (Our Homeland Movement) took place unconstrained in February 2020, while pro-democratic protestors demonstrating in their cars in April and May 2020 were fined.Footnote17 Protests against curtailing academic freedoms and government takeover of universities included students occupying several university buildings in protest. Contestation and pro-democratic protests preceded the pandemic and were mere continuations of the efforts to weaken Fidesz. Although horizontal accountability eroded and free media were attacked both in Hungary and Poland, civil society mobilised in all four countries. Civic activism also substituted for failures of the states to prevent the spread of Covid-19 and to protect the most vulnerable.

The presence or absence of civil society mobilisation in defence of democracy goes beyond the mere assessment of the strength and weaknesses of civil society. There were many forms of civil society mobilisation during the pandemic: protests for racial justice (Black lives matters), protests against the restriction of reproductive rights (Poland 2020, 2021), illiberal policies (Yellow Vests in France), mask mandates, and other pandemic measures (Germany and elsewhere 2020 and 2021), protests for democracy (Bulgaria 2020 and Czechia 2020, 2021). Protests are complex: anti-government protests in the Czech Republic focused on rule of law and democratic pluralism, in Poland the anti-government protests combined calls to protect minorities, abortion rights, and democratic pluralism (cf. Bernhard Citation2021). Protests are important, however, their ability to prevent decay varies significantly and the link between protests and democratic resilience is complex.

Democratic decay due to the pandemic

The challenge of drawing a causal link between government actions to undermine accountability and the pandemic is significant. In this section, we only identify decay for which the pandemic was conducive – a window of opportunity exploited by the government. The analysis of three forms of accountability shows that decay due to the pandemic was rare. previews our findings. We found only two instances of decay that can be directly attributed to the pandemic. First, the expansion of emergency powers in Hungary is a textbook example of a pandemic power grab. Second, the Polish 2020 presidential election contributed to democratic erosion using opportunities related to Covid-19 related restrictions on public gatherings. The incumbent Andrzej Duda was able to campaign nationwide, regardless of the pandemic, which gave him an advantage over the challenger.Footnote18

Table 2. Democratic Decay in Visegrad Four Countries due to the Pandemic.

The only unquestionable pandemic power grab took place in Hungary. It is the only country where horizontal accountability weakened due to the pandemic (). On 30 March 2020, the Hungarian National Assembly passed a law adopting an indefinite state of emergency, which allowed Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to rule by decree (Vegh Citation2020). Moreover, while the law remained fully in force beyond summer 2020, it shifted power to Prime Minister Orbán. The state of emergency prevented parliamentary oversight (which takes place by regular reauthorization of a fixed-term state of emergency). The law gave state prosecutors new powers to imprison anyone who “spread false information or distorted facts”, which silenced political opponents. With the parliamentary opposition sidelined, the jail penalties provided the government also with opportunities to harass civil society and what is left of the free press. As a result, Hungarian citizens have lost a significant part of their civic rights and gained little protection against Covid-19 (Guasti Citation2020).

Initially, vertical accountability was suspended in Hungary until parliamentary elections in 2022. At the onset of the pandemic, all local and national elections, by-elections, and referenda were postponed. The amendment to the electoral law adopted in December 2020 introduced stricter criteria for registering in general elections but cannot be directly linked to the pandemic. While Hungarian elections in 2022 weakened opposition due to the institutional biases that date back to 2010, the Polish Presidential election of 2020 was highly contested.

Although “competitive” and “well-organized,” according to the OSCE, presidential elections in Poland during the pandemic presented the incumbent President Duda with advantages to weaken his opponent. The Freedom House lowered the score for the electoral process from 4 to 3 “because the government attempted to bypass the country’s electoral authority to arrange postal voting for the presidential election, delayed the contest extralegally, and misused state resources to benefit the incumbent.”Footnote19 The pandemic measures weakened the opposition because they restricted the ability of Duda’s opponents to rally behind their candidate Trzaskowski and because the incumbent government created uncertainty about the date of the election. Duda won with a thin margin (51%). However, despite these serious flaws, elections were competitive.

The Polish case also demonstrates that civil pushback can fail. The Polish Constitutional Court issued its abortion ruling during the pandemic in October 2020. The de-facto abortion ban in Poland teaches us that parties in power can push through laws, policies, and regulations that would, under normal circumstances, be subjected to more scrutiny.Footnote20 When the rights of assembly are limited, it is more difficult for citizens to mobilise, yet the mobilisation of Polish civil society during the pandemic – inventing new forms of protest such as traffic blocking shows that intense scrutiny occurred regardless. Perhaps the government viewed the pandemic as a window of opportunity, but this calculation did not add up. Overall, Polish democratic erosion during the pandemic was a continuation of long-term illiberal trends rather than an abrupt turn in the era of Covid-19 as we described in the previous section.

The pandemic was filled with protests, counter-protests, efforts to bend institutions as well as remarkable resilience. Crises are opportunities to expand power that can result in democratic decay. Only Orban’s emergency powers in Hungary and presidential elections in Poland qualify as decay directly attributable to pandemic opportunities. While formal institutions are resilient, informal institutions and more bendable and easier to weaken. What are the weak points of governance that can be exploited during the health crisis? The domains most susceptible to abuse are those in which oversight was directly loosened. The most powerful mechanism that allows politicians to use the pandemic to tilt the level playing field against the opposition is for them to use the power of the purse. This aspect of the pandemic, which we call the “pandemic heist,” is not captured by the pandemic violations index.

Pandemic heist

We identified democratic decay during the pandemic, but found very limited evidence of erosions directly attributable to the health crisis. Now, we “follow the money” to identify the sources of pandemic decay. A political economy approach allows us to find a “smoking gun.” We show how loose fiscal rules and weakening of institutional guardrails allowed parties in power to gain the upper hand. Pandemic is a window of opportunity that enables suspension of oversight in purchasing PPE (personal protective equipment) and increased state spending. Covid-related abuse of state resources stems from previous practices, but the crisis enhances non-transparent processes associated with pandemic-related relief efforts.

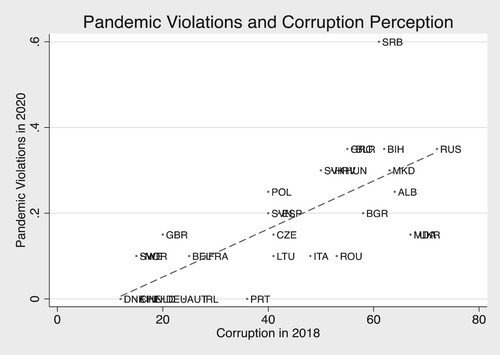

Similar to media freedoms and the quality of democracy, corruption is also path-dependent. shows a strong relationship between pre-pandemic perceived levels of corruption and the degree of pandemic violations. The lack of transparency inherited from the pre-pandemic period is strongly associated with pandemic violations of democratic standards. However, the urgency of government aid during the Covid-19 crisis created new opportunities for pandemic heist, in addition to entrenched processes of fraud and abuse that were already in place. In the next section, we identify areas in which the pandemic deepened underlying trends further and how.

Figure 4. Corruption and Pandemic Violations in Europe (2020–2021). Source: V-Dem. The number of countries = 33.

“Pandemic heist” are actions of executives who use the power of the purse to reward their base and to weaken opponents. Tilted state spending then opens pathways to power grabs due to the pandemic. As the states dramatically expanded state spending to save the economy and propped up the health care sector, three types of pandemic heist emerged: irregularities/corruption in pandemic-related procurement, the use of the pandemic opportunities to rewrite the fiscal rules, and tilting the pandemic relief towards loyalists or regions controlled by the governing party.Footnote21

summarises our findings. Hungarian and Polish governments aggressively used the power of the purse to weaken political opposition. Parties in power provided revenue streams to allies via public procurement irregularities, strategically targeted pandemic relief, and even bent the relief rules. Public procurement irregularities associated with pandemic-related relief and equipment also occurred in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, however, to a lesser degree. In Czechia, we found no evidence that the government tilted the pandemic relief, but the party in power pushed through a new tax reform, which substantively overhauled fiscal rules and centralised power. Slovak new, fragmented government won elections on an anti-corruption platform in 2020. It is the only government in the Visegrad region that was not willing or not capable to use the power of the purse to its benefit.

Table 3. The Power of the Purse: Tilting the Level Playing Field due to the Pandemic.

The pandemic created opportunities to award government contracts without transparent, competitive bidding. In public procurement, the necessity to alleviate the horrific impact of Covid-19 urgently resulted in a significant increase of public contracts awarded without competition. In Hungary, the proportion of state contracts without bidding increased from 19% (pre-pandemic) to 41% (during the pandemic).Footnote22 The contracts were awarded to companies and entrepreneurs with close ties to the government. Subsequent attempts by the institutions of oversight and civil society to provide scrutiny and transparency were dismissed.Footnote23 Similar processes unfolded in Poland. In March 2020, the Polish government adopted a law that provided impunity to public officials who caused a financial loss in acquiring the PPE equipment and other pandemic-related materials.Footnote24 The Polish state de-facto guaranteed immunity from pandemic-related corruption ().

In the Czech Republic, the Supreme Audit Office strongly criticised the lack of preparation for the pandemic, chaos in PPE procurement, price fluctuation, and problems with quality and transport. The most critique was directed toward the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Interior. The two ministries, controlled by two different coalition partners, competed for public support by acquiring PPE and ventilators, especially during the first wave of the pandemic. This resulted in paying inflated prices for masks and other pandemic-related pandemic equipment (Buštíková and Baboš Citation2020). In the second half of 2020 and 2021, similar issues plagued the procurement of antigen and PCR tests for schools and the selection of companies to distribute vaccines across the country.Footnote25 The Supreme Audit Office initiated investigations into procurement. Pandemic-related fraud became a salient issue for some anti-government parties competing in the 2021 parliamentary elections.

However, in most cases, a very small political price was paid for the irregularities in public procurement. An important exception was the purchase of the Sputnik V vaccine by then the Prime Minister of Slovakia Igor Matovič in March 2021. It was a clandestine operation behind the backs of his coalition partners. An anti-establishment advocate Matovič ruled briefly for one year. He faced the challenges of holding together a highly fragmented movement-party OL’aNO and its diverse internal coalition partners. He paid the ultimate political price for his dilettantism and was forced to resign. He was replaced by Eduard Heger in April 2021 (also from OL’aNO).

In contrast to the fragmented executive in Slovakia, the Hungarian and Polish parties in power are more entrenched and stable. They were in a better position to seize upon pandemic opportunities. To directly reward loyalists, Fidesz and Polish Law and Justice Party rewrote fiscal rules (), which allowed them to channel aid to friendly municipalities and undercut large cities. In Czechia, fiscal rules were also changed, yet there is no evidence that the government provided preferential treatment to local and regional governments it controlled. The opportunity to significantly change the tax code was facilitated by huge budget deficits and a rising need to revamp public finances. ANO introduced a new tax scheme, but the law was supported by two antagonistic parties, the governing ANO and the opposition Civic Democratic Party (ODS). ANO and ODS decreased taxes to 15%.

ANO suffered major losses in the 2020 regional and Senate elections. The new tax law, introduced after the regional elections, was designed to undercut regional autonomy. The law benefits any major party in power by increasing centralisation, which strengthens the executive power of the purse. The rules were changed in December 2020 amidst the pandemic that created significant financial strain on municipalities due to revenue losses (e.g. from tourism) and increases in expenditures (hospitals, schools). The change affects future revenue streams of municipalities, especially in Prague and Central Bohemia (both governed by parties not sympathetic to ANO). Unfortunately for ANO, it lost the 2021 parliamentary elections. Fortunately for ODS, its leader became a new Prime Minister.

In Slovakia, the tension between central and local governments also stems from measures that negatively affected the revenues of local municipalities – such as the government's decision in 2020 to allow seniors and students to use public transport free of charge. However, no major fiscal rules were revamped. Furthermore, there was no indication that relief programmes such as interest-free municipal loans were tilted towards some parties or regions controlled by the ruling party OL’aNO. After February 2020, Slovakia was governed by a fragile coalition. OL’aNO, the populist anti-corruption party in power, is a governmental newcomer with no discernible voter base or a regional pattern of voting that could guide it to tilt Covid-related aid.

The pandemic relief can be used as a carrot and a stick in skillful hands. Using new pandemic fiscal guidelines, strong executives can tilt the pandemic relief: loyalists can be rewarded with resources, and political opponents can be punished with scarcity (). In Hungary, Fidesz government withdrew resources from municipalities and limited their competencies (Martin Citation2021; NIT Hungary Citation2022). The government punished localities controlled by the opposition. For example, oppositional municipalities were targeted to perform additional services during the pandemic. The government abolished parking fees, redirected vehicle tax, and made major changes in the allocation of solidarity tax.

Some competencies of municipalities were revoked and their revenues were diverted to designated special economic zones during the state of danger. These measures were designed to undermine Budapest and other cities, such as Göd, governed by the opposition.Footnote26 According to Martin (Citation2021), “the town of Göd, home to a major Samsung factory, now stands to lose 10% of its annual budget due to being placed in one of these new zones (i.e. an area whose tax income is transferred directly to the county budget instead of the local administration).” The leader of the Hungarian opposition alliance “United for Hungary” Peter Marki-Zay, a mayor of the city of Hodmezovasarhely told to Foreign Policy, that due to the pandemic-era funding reallocations the city will lose 7–8 percent of its overall income. In his words: “It’s a huge blow. … It makes absolutely no sense, except as a political annihilation of opposition political cities … They used the COVID crisis to conduct a smear campaign against opposition mayors and criticise us for anything. … We are very easy to blame” (Foreign Policy Citation2020). Therefore, undercutting municipalities allows Orban to shift responsibility for a bad pandemic response (cf. Chaisty, Gerry, and Whitefield Citation2022).

Similarly, in Poland, pandemic relief rewarded loyalists and punished opponents. The PiS government decided to allocate 50% of the pandemic relief to municipalities based on population size and the other 50% based on “competitive grant procedures.” These allocation formulas are similar to the Local Roads Fund and are skewed significantly towards the municipalities governed by the ruling parties, especially sympathetic to Law and Justice Party (NIT Citation2022). Matuszak, Totleben, and Piątek (Citation2022) analyzed the allocations from the Governmental Fund for Local Investments (GFLI) to Polish municipalities. They find that “municipalities in which a mayor was aligned with the ruling coalition were significantly more likely to receive the second- and third-round GFLI funds than municipalities in which the mayor was either aligned with the opposition or unaligned with any party in the parliament … [and] the coalition municipalities were receiving higher per capita funds than the opposition and unaligned municipalities in round 2” Matuszak, Totleben, and Piątek (Citation2022, 64–65).

Flis and Swianiewicz (Citation2021) reach similar conclusions. Their analysis of the third installment of the Central Governmental Fund for Local Investments paid out in March 2021 concludes that the allocation of funds favoured small municipalities. They also found that the allocation of funds was biased: “Nearly all the municipalities run by PiS mayors received funding, with half of them even receiving it twice. In contrast, in a clear majority of cases, municipalities with mayors from the opposition parties were bypassed in both installments” (Flis and Swianiewicz Citation2021, 3).

The “pandemic heist” is the most common pandemic violation that is both effective and can be directly attributed to opportunities afforded by the health crisis. Some parties use the crisis to use the power of the purse with impunity others are restrained. The Covid-19 crisis legitimises big state spending. Hungary and Poland took advantage of controlling public finances as they allocated pandemic relief. Procurement irregularities and corruption increased in all four countries, but only Slovakia did not use the crisis to overhaul public finances or to construe politicised fiscal laws. In a crisis, government spending is subjected to weaker regulations, and crisis management can easily bypass the confinements of institutional rules. The pandemic necessitates limited oversight and loosens up budgetary constraints. It also allows for a revamp of fiscal policies and facilitates executive dominance as procurement contracts are often awarded to political cronies, allies, and loyalists. Parties in power gain disproportionate access to emergency funds and are tempted to abuse them as they reward allies with a carrot and punish the opposition with a stick. The executive power of the purse is a significant opportunity to channel state resources to loyalists. All governments are tempted by the “pandemic heist,” but those that proceed with impunity can be directly linked to a power grab due to the pandemic.

Conclusion

What is the source of democratic decay in the pandemic? Extraordinary crises, such as Covid-19 outbreak, are opportunities to expand power. We identify two gaps in the literature on pandemic distortions of democratic standards. First, more is needed to identify mechanisms that link power abuses to the pandemic. While the literature can demonstrate decay (Engler et al. 2021; Edgell et al. Citation2021; Guasti Citation2020; Petrov Citation2020), it does not differentiate between processes of decay that are happening during the pandemic or due to the pandemic.

Second, most of the Covid-related research in political science has paid attention to violations of formal institutions, but less attention is devoted to pandemic finances (for an exception, see Bohle et al. Citation2021). This is unfortunate, since pandemic-related spending and limited oversight create new opportunities for corruption in public procurement and distribution of pandemic relief. The executive power of the purse creates opens doors to politicisation and hijacking of the pandemic spending (Bruckner Citation2019; Bustikova and Corduneanu-Huci Citation2017; Kirya Citation2020; Rose-Ackerman Citation2021; Terziev, Georgiev, and Bankov Citation2020; The World Justice Project Citation2020).

We analyze the extent to which pandemic power grabs succeeded and failed in Europe using the new V-Dem dataset on pandemic violations. We then explore the Visegrad Four countries to differentiate between democratic decay that happened during the pandemic from decay due to it. Three findings stand out. First, democratic decay occurs predominantly during the pandemic – as part of a path-dependent process in countries where institutional guardrails have been already weakened (Bustikova Citation2020; Stanley Citation2019; Vachudova Citation2020). We selected Visegrad Four countries as countries with pandemic violations, and we found that democratic decay due to the pandemic is rare. Third, we find evidence that pandemic executives benefited from the power of the purse. The pandemic power grab results from opportunities for governments to bypass institutions of oversight in public procurement and to tilt allocations of public resources during the pandemic.

Formal institutions are remarkably resilient during the pandemic as courts, media, civil society, and political opposition push back against governmental over-reach. There are effective pathways to halt pandemic executives. Civic activism is necessary. Political opposition must be willing to overcome fragmentation. Courts must balance the interests of public health and democracy. But the pandemic finds a back door: the health crisis affects democratic decay via informal institutions and the ability of the governments to allocate spending, rewrite fiscal rules of the game, and reward insiders with pandemic contracts when oversight is weakened. Ultimately, this weakens the opposition and strengthens the executive.

In stark opposition to the financial crisis of 2008, the Covid-19 pandemic is the first major crisis after 1989 that necessitates major public spending. The power of the purse creates opportunities to weaken opponents using fiscal tools. A warning is in place. Future major public spending programmes such as the national and the EU recovery programmes will enhance opportunities for power grabs. Without strong oversight, the pouring of new funds onto current governments might accelerate democratic decay in countries with weak institutional guardrails. Future research should focus on mechanisms of democratic decay and resilience, broaden the analysis beyond the study of formal institutions and pay special attention to the relationship between the political economy of pandemic relief and democratic quality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We thank Julia Grantham and Grace Hough for research assistance. We thank Hilary Appel, Marcel Lewandowsky, Jean-Benoit Pilet, Doro Bohle and two anonymous reviewers for comments. The draft of the paper was presented at various conferences including Keck Center for International and Strategic Studies, Claremont McKenna College, 2021; Reset Conference: Still the Age of Populism?, University of Florida, 2022; Technocratic attitudes, technocratic government and support for experts in Europe, CEVIPOL Connference, Brussels, 2022; ECPR GC22, Innsbruck, 2022.

2 The Pandemic Violations of Democratic Standards Index (PanDem). The PanDem index and the Pandemic Backsliding Index “provide a snapshot of how emergency responses to Covid-19 may be affecting the quality of democracy within the country.” The PanDem index has the following seven components: discriminatory measures, derogations from non-derogable rights, abusive enforcement, no time limit, limitations on legislature, official disinformation, restrictions of media freedom. Source: V-Dem. Pandemic Backsliding Index: Democracy During COVID-19 (March to June 2021). Source: https://www.v-dem.net/en/analysis/PanDem/.

3 Moreover, the index of pandemic violations highly correlates with the index of liberal democracy before the pandemic and during the pandemic.

6 Sources: https://www.dw.com/en/poland-state-run-oil-company-buys-leading-media-group/a-55859592 https://balkaninsight.com/2021/04/12/warsaw-court-blocks-takeover-of-polish-regional-media-by-state-owned-orlen/ https://rm.coe.int/poland-reply-en-orlen-s-takeover-of-polska-press-exposes-media-plurali/1680a14141 https://www.article19.org/resources/pkn-orlen-media-purchase-violates-eu-merger-rules/

9 Between 2018–2021, PM Andrej Babis led minority coalition government of ANO and social democrats with the support of the communists. Petr Fiala formed a new government of five center right parties after October 2021 general elections. The new government won the vote of confidence in January 2022.

10 Source: https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/04/28/poland-how-populists-have-exploited-coronavirus-pub-81648

14 These numbers are based on circulation. Source: https://hlidacipes.org/ondrej-neumann-babis-sva-media-uzivi-ze-statu-a-agrofertu-ostatni-hazi-pres-palubu/. Source: https://www.forum24.cz/ministerstvo-posila-evropske-penize-do-agrofertu-pres-mf-dnes-jasny-stret-zajmu-reaguji-europoslanci/

16 During women's protest the police used “the sanitary restrictions in force to stifle protests. The police checked participants' identity documents, detained them, and used direct coercion measures. Some of the interventions were characterized by brutality, which was exceptional for Polish conditions, including beatings of demonstrators by ununiformed officers from anti-terrorist units.” Source: https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/hapscpbs/issue/view/1598/462

19 Freedom House. Poland. 2021. Source: https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/freedom-world/2021

20 Source: https://www.politykazdrowotna.com/71080,aborcja-stala-sie-praktycznie-niedopuszczalna-w-polsce

21 The European countries increased budget deficits during the pandemic. Compared with the first quarter of 2020, all European member states registered an increase in their debt to GDP ratio at the end of the first quarter of 2021 (by 13.7%.). The euro area increased the ratio by 14.4%. Cyprus and Greece increased their debts by almost thirty percent, while Ireland and Norway increased debt by less than two percent. Czechia increased its debt by 11.7%, Hungary by 15.3%, Poland by 11.6% and Slovakia by 10.8%. Source: Eurostat. Government debt up to 100.5% of GDP in euro area. 84/2021– 22 July 2021. Link: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/11563191/2-22072021-AP-EN.pdf/282c649b-ae6e-3a7f-9430-7c8b6eeeee77?t=1626942865088

23 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021SC0714 https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/nations-transit/2022

24 Article 10d reads: “No crime shall be committed by whoever infringes official duties or applicable laws and regulations in order to counteract COVID-19 while acting in the public interest and where such action could not have been possible or had been considerably at risk without such infringement”. Source: https://www.batory.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Tarcze_ENG.pdf Also see: https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/nations-transit/2021.

References

- Afsahi, A., E. Beausoleil, R. Dean, S. A. Ercan, and J.P. Gagnon. 2020. Democracy in a global emergency: five lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Democratic Theory 7 (2): v–xix.

- Aktürk, Şener, and Idlir Lika. 2022. “Varieties of Resilience and Side Effects of Disobedience: Cross-National Patterns of Survival During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Problems of Post-Communism 69 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/10758216.2021.1894405.

- Anghel, Veronika, and Erik Jones. 2022. “Failing forward in Eastern Enlargement: problem solving through problem making.” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (7): 1092–1111.

- Bermeo, Nancy. 2016. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27 (1): 5–19.

- Bernhard, Michael. 2020. “What do we Know About Civil Society and Regime Change Thirty Years After 1989?” East European Politics 36 (3): 341–362.

- Bernhard, M. 2021. “Democratic Backsliding in Poland and Hungary.” Slavic Review 80 (3): 585–607.

- Bernhard, M., A. Hicken, C. Reenock, and S. I. Lindberg. 2020. “Parties, Civil Society, and the Deterrence of Democratic Defection.” Studies in Comparative International Development volume 55: 1–26.

- Bohle, Dorothea, G. Medve-Balint, V. Scepanovic, and A. Toplisek. 2021. “Varieties of Authoritarian Capitalisms? The Covid-19 Response of Eastern Europe’s Right-wing Nationalists.” This special issue.

- Bruckner, Till. 2019. “The Ignored Pandemic: How Corruption in Healthcare Service Delivery Threatens Universal Health Coverage.” Transparency International (2019). http://ti-health.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/IgnoredPandemic-WEB-v2.pdf

- Bustikova, Lenka. 2020. Extreme Reactions: Radical right mobilization in Eastern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Bustikova, Lenka, and Cristina Corduneanu-Huci. 2017. “Patronage, Trust, and State Capacity: The Historical Trajectories of Clientelism.” World Politics 69 (2): 277–326.

- Buštíková, Lenka, and Pavol Baboš. 2020. “Best in Covid: Populists in the Time of Pandemic.” Politics and Governance 8 (4): 496–508.

- Chaisty, Paul, Christopher J. Gerry, and Stephen Whitefield. 2022. “The Buck Stops Elsewhere: Authoritarian Resilience and the Politics of Responsibility for COVID-19 in Russia.” Post-Soviet Affairs 38 (5): 366–385.

- Cheibub, Jose A, Ji Yeon Jean Hong, and Adam Przeworski. 2020. “Rights and Deaths: Government Reactions to the Pandemic.” SSRN 3645410.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, Nazifa Alizada, David Altman, et al. 2021. V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v11.1” Varieties of Democracy Project. also V-Dem, version 12 (March 2022). doi:10.23696/vdemds21

- Cormacain, Ronan, and Ittai Bar-Siman-Tov. 2020. “Legislatures in the Time of Covid-19.” Theory and Practice of Legislation 8: 1–2.

- Dovbysh, Olga, and Katja Lehtisaari. 2020. “Local Media of Post-Soviet Countries: Evidence from Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine.” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 28 (3): 335–343.

- Edgell, Amanda B., Jean Lachapelle, Anna Lührmann, and Seraphine F. Maerz. 2021. “Pandemic Backsliding: Violations of Democratic Standards During Covid-19.” Social Science & Medicine 285: Article 114244.

- Edgell, Amanda B., Jean Lachapelle, Anna Lührmann, Seraphine F. Maerz, Sandra Grahn, Palina Kolvani, AnaFlavia Good God, et al. 2020. Pandemic Backsliding: Democracy During Covid-19 (PanDem), Version 6. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, www.v-dem.net/en/our-work/research-projects/pandemic-backsliding/

- Engler, S., P. Brunner, R. Loviat, T. Abou-Chadi, L. Leemann, A. Glaser and D. Kübler. 2021. “Democracy in times of the pandemic: explaining the variation of COVID-19 policies across European democracies.” West European Politics 44 (5–6): 1077–1102.

- Flis, Jarosław, and Paweł Swianiewicz. 2021. The Central Government Fund for Local Investments III – patterns taking hold. Stefan Batory Foundation. Source: https://www.batory.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/The-Government-Fund-for-Local-Investment-III_patters-taking-hold.pdf

- Foreign Policy. 2020. Emily Schultheis. July 28. Viktor Orban Has Declared War on Mayors. Source: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/28/viktor-orban-has-declared-a-war-on-mayors/

- Gallego, Jorge A., Mounu Prem, and Juan F. Vargas. 2020. “Corruption in the Times of Pandemia.” SSRN 3600572.

- Guasti, Petra. 2020. “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Central and Eastern Europe.” Democratic Theory 7 (2): 47–60.

- Guasti, Petra, and Jaroslav Bilek. 2021. “Take a Chance on Me: The Supply Side of Vaccine Politics and Pandemic Illiberalism.” This special issue.

- Habersaat, K. B., C. Betsch, M. Danchin, C. R. Sunstein, R. Böhm, A. Falk, … R. Butler. 2020. “Ten Considerations for Effectively Managing the COVID-19 Transition.” Nature Human Behaviour 4 (7): 677–687.

- Kirya, Monica. 2020. “Anti-corruption in Covid-19 Preparedness and Response.” https://www.u4.no/publications/anti-corruption-in-covid-19-preparedness-and-response.pdf

- Lindberg, S. I. 2013. Mapping accountability: core concept and subtypes. International review of administrative sciences 79 (2): 202–226.

- Maerz, Seraphine F., Anna Lührmann, Jean Lachapelle, and Amanda B. Edgell. 2020. “Worth the Sacrifice? Illiberal and Authoritarian Practices during Covid-19.” Illiberal and Authoritarian Practices during Covid-19 (September 2020). V-Dem Working Paper 110.

- Marinov, Nikolay, and Maria Popova. 2021. “Will the Real Conspiracy Please Stand Up: Sources of Post-Communist Democratic Failure.” Perspectives on Politics, 1–15. doi:10.1017/S1537592721001973.

- Martin, József Péter. 2021. “How Hungary’s Viktor Orban is using Covid to Enrich his Cronies and Clientele. February 3.” https://capx.co/how-hungarys-viktor-orban-is-using-covid-to-enrich-his-cronies-and-clientele/

- Matuszak, Piotr, Bartosz Totleben, and Dawid Piątek. 2022. “Political Alignment and the Allocation of the COVID-19 Response Funds-Evidence from Municipalities in Poland.” Economics and Business Review 8 (1): 50–71.

- NIT. 2022. “Nations in Transit 2022 Report: From Democratic Decline to Authoritarian Aggression.” Washington, DC: Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2022/from-democratic-decline-to-authoritarian-aggression

- NIT Hungary. 2022. “Nations in Transit 2022 Hungary Report.” Washington, DC: Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/nations-transit/2022

- Petrov, Jan. 2020. “The COVID-19 Emergency in the Age of Executive Aggrandizement: What Role for Legislative and Judicial Checks?” The Theory and Practice of Legislation 8 (1-2): 71–92.

- Pirro, A. L., and B. Stanley. 2022. “Forging, Bending, and Breaking: Enacting the “Illiberal Playbook” in Hungary and Poland.” Perspectives on Politics 20 (1): 86–101.

- Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 2021. “Corruption and COVID-19.” EUNOMÍA. Revista en Cultura de la Legalidad 20: 16–36.

- Ruth, Saskia P. 2018. “Populism and the Erosion of Horizontal Accountability in Latin America.” Political Studies 66 (2): 356–375.

- Ruth-Lovell, Saskia P., Anna Lührmann, and Sandra Grahn. 2019. “Democracy and Populism: Testing a Contentious Relationship.” V–Dem Working Paper 91.

- Sebhatu, Abiel, Karl Wennberg, Stefan Arora-Jonsson, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2020. “Explaining the Homogeneous Diffusion of COVID-19 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Across Heterogeneous Countries.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (35): 21201–21208.

- Stanley, Ben. 2019. “Backsliding Away? The Quality of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 15 (4): 343–353.

- Terziev, Venelin, Marin Georgiev, and S. M. Bankov. 2020. “Increasing the Risk of Corruption Activities during a COVID-19 Pandemic (August 12).” https://ssrn.com/abstract=3674427 or doi:10.2139/ssrn.3674427

- Vachudova, Anna M. 2020. “Ethnopopulism and Democratic Backsliding in Central Europe.” East European Politics 36 (3): 318–340.

- Vegh, Zsuzsanna. 2020. “No More Red Lines Left to Cross: The Hungarian Government’s Emergency Measures.” www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_no_more_red_lines_left_to_cross_the_hungarian_governments_emerge

- Weyland, Kurt. 2020. “Populism’s Threat to Democracy: Comparative Lessons for the United States.” Perspectives on Politics 18 (2): 389–406.

- The World Justice Project. (2020). “Corruption and the COVID-19 Pandemic”. https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/2020-07-01%20Corruption%20and%20the%20COVID-19%20Pandemic_1.pdf