ABSTRACT

Political parties use electoral clientelism to mobilise their core voters and to persuade swing voters to support them. Earlier research shows that clientelism occurs more often in highly competitive elections. Against these conclusions, this article argues that a large margin of victory can drive the use of electoral clientelism irrespective of the type of constituency. The analysis uses county-level data from the 2020 election campaign in Romania and shows that electoral clientelism is used more in those constituencies with a clear winner. These effects are robust when controlling for socio-economic vulnerability and the percentage of the urban population.

Introduction

Electoral clientelism is the process through which political parties use public resources to increase support in society, mobilise voters and maintain access to political power (Piattoni Citation2001; Carreras and İrepoğlu Citation2013; Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Citation2014). The literature focusing on which voters are targeted by electoral clientelism goes in three directions. First, the core voter model argues that political parties are likely to distribute benefits primarily to their loyal voters. This happens because the party knows them well and the voters are embedded in partisan networks. As such, electoral clientelism can be used effectively to maintain loyalty and to mobilise them (Cox and McCubbins Citation1986; Cox Citation2009; Calvo and Murillo Citation2013; Diaz-Cayeros, Estevez, and Magaloni Citation2016). Second, the swing voter model claims that political actors could target voters who are open to political alternatives and who support different competitors over time. Electoral clientelism would be used in this case to persuade citizens how to vote. This applies both to voters of other parties hoping to determine a change of preferences or to persuade voters who are undecided (Dixit and Londregan Citation1996; Dahlberg and Johansson Citation2002; Stokes et al. Citation2013). These two models illustrate that clientelism can be used to mobilise own voters or to chase opposition or undecided voters (Rohrschneider Citation2002; Nichter Citation2008). A third possibility is the combination of the core and swing voter approach to augment electoral support. Diversified approaches include targeting different types of voters with different types of goods or distributing benefits selectively (Calvo and Murillo Citation2013; Stokes et al. Citation2013; Diaz-Cayeros, Estevez, and Magaloni Citation2016; Corstange Citation2018).

Much research on the core vs. swing voter models of clientelism tests them in conditions related to poverty, weak partisan attachment or low propensity for turnout (Nichter Citation2008; Collier and Vicente Citation2012; Diaz-Cayeros, Estevez, and Magaloni Citation2016). However, much less attention is paid to what happens when electoral competition is considered. The few studies on the topic outline that political parties campaign more in competitive areas, but have difficulties in targeting resources evenly across electoral areas (Casey Citation2015). Previous research also distinguishes between the types of incentives provided in the electoral strongholds vs. competitive districts (Corstange Citation2018). The existing line of enquiry considers that electoral competitiveness occurs outside party strongholds, where core voters are placed. This article extends this literature by offering a different perspective. Unlike the existing wisdom in the literature concluding that clientelism occurs more in competitive constituencies (Lindberg and Morrison Citation2008; Weitz-Shapiro Citation2012; Poteete Citation2019), we argue that clientelism is used more in those constituencies where there was a large margin of victory in the previous elections. We analyse if the mechanism is similar irrespective of the type of constituencies (core vs. swing). In brief, this study seeks to answer the following research question: What are the effects of constituency type and margin of victory on the use of clientelism at the constituency level?

Empirically, we focus on the 2020 legislative election in Romania and use aggregate data of electoral clientelism at the constituency (county) level. The constituency is the appropriate level of analysis because it allows observing the margin of victory, which is calculated for each constituency in the Romanian electoral system and links the constituency type with party strategies. Romania is the most likely case to observe the expected effects due to its high use of electoral clientelism, weak partisan ties and the existence of party strongholds (core constituencies). Although the evidence is limited to one election and to a relatively limited number of observations, it is an important exploratory test of our argument. We assess the level of clientelism with the help of primary data from an original survey conducted in January 2021 on a nationally representative sample of 4,316 respondents. We use secondary data for the electoral performance of parties, which inform about both the type of constituency and the margin of victory. Secondary data at the county level are used to assess the control variables: economic vulnerability, the share of urban areas inhabitants, voter turnout, the winning party and the average age of the population. We focus on the positive – as opposed to coercive – forms of electoral clientelism (Mares and Young Citation2019), which include a wide range of actions from goods and money to preferential access to social benefits and jobs. Positive clientelism is much more common in elections and voters in Europe are usually exposed more to its forms than to coercive clientelism.

The next section discusses the theoretical connection between core constituencies, electoral competition and the use of clientelism. This includes a discussion about hypotheses. The third section is devoted to case selection, variable measurement and methods of data analysis. Next, we present and interpret the main results, while also embedding them in the broader literature. The conclusions cover the implications of our findings for the broader field of study and discuss directions for further research.

Core constituencies, electoral competition and clientelism

There are two categories of citizens that are targeted by electoral clientelism: core and swing voters. Core voters are supporters who identify culturally, ideologically and politically with a political actor (Corstange Citation2018). They develop partisan feelings and support a party for what it represents and not for what they can gain if they support it. In their case, political actors use electoral clientelism as a strategy to enforce their partisanship and to make sure that they will remain loyal to them (Hicken Citation2011). This could be done by providing them with material (e.g. goods, money) or non-material (e.g. welfare policies) benefits that enforce the belief that political actors value them beyond ideological and political reasons (Stokes Citation2009; Gherghina Citation2013). Core voters are easier to target by the political actors because they are embedded in party networks and they do not risk wasting resources (Mares and Young Citation2018; Rauschenbach and Paula Citation2019).

The clientelistic political machines include three types of actors and the relations between these. These actors are the patrons (political parties or candidates) who distribute material or non-material goods and provide preferential access to services with the help of brokers (partisan intermediaries) to their clients (voters) (Muñoz Citation2014; Schaffer and Baker Citation2015). The systematic distribution of clientelistic offers enforces the partisanship of loyal supporters and is mostly employed as a strategy to reward loyal voters who become aware of the benefits of clientelism (Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Citation2014; Yıldırım and Kitschelt Citation2020). Machine parties engage in turnout buying for core constituents who would not otherwise vote (Nichter Citation2008). While it makes little sense for political parties to use clientelism in their core constituencies in the case of single-shot elections (Stokes Citation2005), elections are iterated games in which parties and voters meet regularly. Consequently, the forward-looking parties cement their relationship with the loyal voters through clientelistic inducements.

Electoral clientelism can also work as a persuasion instrument meant to stimulate political participation and influence vote choice (Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Citation2014). Swing voters do not have political affiliations or partisan feelings. They change their political preferences and usually support only those actors that promote policies that are in line with their expectations or that give them something (Weghorst and Lindberg Citation2013). They are still available on the electoral pool and are highly targeted with clientelist practices by those who want to maximise their votes (Stokes Citation2009; Hicken et al. Citation2022).

However, unlike core voters, electoral clientelism is more costly for swing voters. Political actors risk to waste resources if they failed to identify the swing voters and their expectations or needs (Weghorst and Lindberg Citation2011; Rauschenbach and Paula Citation2019; Hicken et al. Citation2022). Swing voters are motivated by short-term rewards and could be more rational and sophisticated in their political choice because they are not constrained by political ideologies or group loyalties (Dassonneville and Stiers Citation2018). Following these arguments, we expect:

H1: Core constituencies favoiur the use of electoral clientelism.

Electoral competition

The degree of electoral competition can influence the use of clientelism. The latter is likely to occur when there is strong electoral competition and large numbers of undecided voters whose engagement would change the political outcome (Hicken Citation2011; Weghorst and Lindberg Citation2011). Under these circumstances, the single machine assumption according to which only one political party engages in clientelism (Stokes Citation2009; Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Citation2014) is replaced by competitive clientelism in which several party machines bid for voters (Lust Citation2009). In competitive constituencies the use of clientelism could maximise the vote shares for those political actors using it. When the race is tight, the distribution of resources could be the supplementary incentive to persuade voters to sway.

However, there are reasons for which electoral clientelism can be used extensively in non-competitive constituencies. Both the winner and the challengers can gain from engaging in such practices. On the one hand, the winner in electoral strongholds may use clientelism to secure its dominance. Political parties cannot take for granted that electoral support will be at similar levels over time. By maintaining a large share of votes in the constituency, parties have two main benefits. First, they ensure continuous support, send a signal of symbolic legitimacy to the electorate and to other parties, and thus strengthen their position in the political system. In doing so, parties target both core and swing voters. Core voters are unlikely to remain loyal if clientelistic benefits are aimed only at swing voters (Nichter Citation2008). At the same time, winning parties may also target the supporters of other parties hoping to increase their ranks and to compensate for potential losses from their own electorate (e.g. people leave the constituency and change preferences).

The signal of legitimacy could create domino effects in future among the electorate, i.e. voters would keep supporting these parties to be on the winning side. It could also provide other parties with incentives to engage in (coalition) agreements with the winners (Corstange Citation2018). Second, the winners cultivate an image of invincibility in that constituency, which decreases the likelihood of internal conflict and the costs of competition in future (Magaloni Citation2006; Szwarcberg Citation2015; Corstange Citation2018). The frequent targeting of own voters with clientelistic inducements gets voters used to certain types of goods and services. It also keeps the costs under control in future by preventing voters from demanding more expensive treats.

On the other hand, challenger parties provide clientelistic inducements to secure the runner-up position in the constituency and to diminish the strength of the winner. First, they use clientelism as a mobilising strategy aimed at their own voters who may change their preferences if only the winner party distributes resources in the constituency. This strategy is reactive to electoral pressure and reflects a bandwagon effect in which the winner sets a trend and the challengers follow to avoid higher electoral losses. Moreover, the challenger parties could be inclined towards clientelism out of the fear that other competitors – not only the winner – may use it, which may result in vote loss for themselves. In this case, clientelism is rooted in credible threats from competitors.

Second, challenger parties may use clientelism to court either the winner’s supporters or the undecided voters. Political responsiveness and clientelism can coexist rather than being opposite forms of political mobilisation (Poteete Citation2019). Even in elections that render outcomes certain, challenger parties may strive to lower the dominance of one competitor and to narrow the margin of victory. They do so by complementing their programmatic appeals with clientelistic inducements. Without such efforts, voters may perceive that the challengers gave up and accepted defeat. Equally important, political parties that are challengers in some electoral strongholds are likely to have safe constituencies elsewhere in the country. Parties are inconsistent if they provide clientelistic inducements in those constituencies in which they are safe winners, but do proceed differently in constituencies where they are runners-up or lower. Such inconsistency may be perceived negatively by the electorate and have negative effects that are difficult to anticipate. According to all these arguments, we expect:

H2: High margin of victory in previous elections favours the use of electoral clientelism.

Controls

In addition to these main effects, we control for several variables that were considered usual suspects in the literature: economic development, rural population, turnout, winning party and the average age of the population. The level of economic development is one of the most common explanations in the literature. Some argue that economically deprived communities and individuals receive clientelistic inducements (Auyero Citation1999; Weitz-Shapiro Citation2012; Sugiyama and Hunter Citation2013). There is also a higher demand for clientelism among the socially and economically deprived segments of society (Nichter Citation2010; Weitz-Shapiro Citation2014; Kao, Lust, and Rakner Citation2017). However, the evidence is mixed (Hicken Citation2011) and some studies find no evidence of income effects (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al. Citation2012).

The type of community in which voters live could influence the extent of electoral clientelism. The tight social structure and community cohesion of rural areas provide the possibility of establishing emotional long-term ties between parties and voters (Koter Citation2013). Clientelistic linkages can be stronger in rural areas characterised by low literacy or limited modes of communication (Cinar Citation2016). However, evidence also indicates that clientelism thrives in urban settlements, especially in the provision of land and services (Deuskar Citation2020).

We also control voter turnout because this can be one of the aims of electoral clientelism. When receiving inducements voters are asked to turn out, to stay home or to change their vote choices (Stokes Citation2005; Nichter Citation2008; Larreguy, Marshall, and Querubín Citation2016). Turnout buying rewards demobilised supporters for showing up to the polls, while abstention buying is a demobilisation strategy that rewards individuals for not voting (Schedler and Schaffer Citation2007; Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter Citation2014; Hagene Citation2015). The winning party may also make a difference in the use of clientelism since large parties have a higher access to resources. Some of the large parties are in office at the time of elections and incumbents engage more often in clientelistic exchanges compared to opposition parties (Larreguy, Marshall, and Trucco Citation2012). Finally, the population age might make a difference regarding the use of clientelism because young people put pressure on politicians to provide jobs and access to services (Keefer Citation2005). At the same time, young people are more informed, better organised, more critical and more demanding towards, which could make them less desirable targets for clientelism (Loughlin Citation2020).

Research design

Our exploratory endeavour draws on evidence regarding the use of clientelism in Romanian counties during the most recent legislative elections (December 2020). We focus on Romania as the most likely case in which they may be observed. There are three elements that are relevant: the use of electoral clientelism, weak partisan ties/electoral volatility and the party strongholds (core constituencies). First, there is extensive use of electoral clientelism in the country. Earlier evidence shows how political parties use it regularly since 2008 (Gherghina Citation2013; Gherghina and Volintiru Citation2017; Mares and Young Citation2019). Second, there are high levels of electoral volatility documented both at the individual and party level (Chiru and Gherghina Citation2012; Gherghina Citation2014; Marian Citation2018; Gherghina and Soare Citation2021), which indicate the existence of many swing voters. This volatility is reflected in the high number of entries and exits from the political scene, and in the alternation in government. Since 1992, there was no instance in which the party leading the government coalition for a full term in office joined the coalition government after the legislative elections. This happened despite that the social democrats won the popular vote in eight out of the nine national legislative elections organised since the regime change. Although this is the party with the lowest electoral volatility in the country, it had an important variation of electoral support in the two most recent legislative elections: in 2016 slightly more than 45% of the votes, while in 2020 slightly less than 30%. Third, the territorial distribution of votes changes over time. Empirically, in 2020 half of the constituencies were electoral strongholds, while the others are competitive.

The unit of analysis is the constituency. There are 43 electoral constituencies that correspond to the 41 counties, which are the territorial-administrative divisions of the country, one for the capital city Bucharest and one for the Romanians in the diaspora. The constituencies are represented in each Chamber proportional to the share of its population. There is an electoral threshold of 5% for political parties and one of 8–10% for electoral alliances and coalitions, depending on the number of parties. For this study we look at the 42 constituencies within the country’s territory; we do not include the diaspora constituency due to its heterogenous character and limited use of clientelism.

The dependent variable of this study is the use of electoral clientelism. We measure it with the help of a survey conducted on a representative sample at a national level of 4316 citizens in Romania in January 2021. The survey was conducted immediately after the 2020 legislative elections and included roughly 100 respondents from each of the 41 counties plus roughly 200 from the capital city Bucharest. The sample was not representative at the county level, but there is great variation in terms of age, education and areas of residence. The respondents had to indicate if they knew someone who was offered during the election campaign money, food, transportation to the polls, the promise of a job after the election, access to welfare benefits or preferential access to public services by political parties in exchange for their votes. We treat the distribution of jobs, social benefits or access to funds as important as vote-buying (money), food provision or transportation because they are forms of rational clientelism (Yıldırım and Kitschelt Citation2020). We coded 1 all those respondents who indicate knowing the recipients of at least one form of positive clientelism and then we aggregated the answers at the county level. For example, 16 out of 100 respondents in Alba (AB) county indicated that they knew someone who was offered clientelistic inducements, and that results in a percentage of 16% clientelism for that county.

We use this indirect measurement of clientelism in which individuals are asked about clientelism for the people they know because the direct question does not work.Footnote1 The sensitivity of the topic determines people to limit drastically the self-reporting and thus induce social desirability bias (Gonzalez-Ocantos et al. Citation2012). Moreover, when asked if they received clientelistic inducements, very few people admit it because in many countries (including Romania) it is illegal. We asked the direct question in our survey but the results were as expected. To use the same example of Alba, only two out of 100 persons acknowledged that they were offered clientelistic goods in exchange for their votes. There are three caveats of the measurement used in this article. First, it assumes that the people known by the respondents live in the same county with the respondent. This is a realistic assumption for Romania since the counties are large – average population size around 450,000 – and very few respondents work in a different county than the one of residence. As such, it is likely that their acquaintances live in the same county. There is no official statistics about the share of people working in a different county, but many of the work-related documents are linked to the county of residence. This limits the mobility of the population across counties. Second, there is a possibility of underestimation of clientelism because people may be ashamed to admit that they know someone who was offered clientelistic inducements. While this is something likely to occur, it is a random error that can be overcome through our large sample size (averaging over a large number of observations). Third, there is a possibility of overestimation of clientelism if the respondents refer to the same person as a potential recipient of clientelistic inducements. This is possible to occur but highly improbable since the counties are large and the respondents come from different localities.

The existence of strongholds is measured by comparing the winner of popular votes in each country in 2008, 2016 and 2020.Footnote2 In 2008 the elections were organised under a system of mixed-member proportional representation. In 2016 and 2020 the electoral system was proportional representation with blocked lists.Footnote3 In 2008, the major party contesting the elections was the Democratic Liberal Party (PDL), which merged with the National Liberal Party (PNL) in 2014. If a county had the same winner in all three elections, then we consider that county an electoral stronghold. Those counties in which the PDL won in 2008, and the PNL won in 2016 and 2020 were considered strongholds because the two parties merged. All other counties, in which the winner of the popular vote varies, were considered swing counties. The coding shows that for this time period half of the counties (21) are electoral strongholds, while the remaining half are swing counties. The electoral strongholds belong to three political parties: social-democrats (PSD) has 14, PNL has three and the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR) has four.

The margin of victory at the county level is calculated as the difference in the share of votes between the first- and second-ranked parties in the 2016 elections. We use the 2016 elections as a point of reference because those indicate the clarity of preferences in those counties and how close the race was in the previous elections. These factors could influence parties’ decisions to use clientelism at the beginning of the 2020 election campaign.

The share of unemployed people relative to the county population, the percentage of people in urban areas and the average population age per county are straightforward measures. The data for all three come from the National Institute of Statistics in Romania. The party winning the elections in the county in 2020 is a nominal variable that differentiates between the four possible winners: PSD, PNL, Save Romania Union – Freedom, Unity and Solidarity Party (USR PLUS) and UDMR. A fifth political party gained seats in the 2020 election (Alliance for the Union of Romanians, AUR), but it did not win any county. The voter turnout is measured as the percentage of those individuals who voted out of the voting-age population. The data for all three variables come from the website of the Romanian Permanent Electoral Authority. For descriptive statistics that include the mean, the standard deviation and minimum and maximum values, please see Appendix 1.

We use a method of analysis multivariate OLS regression. We are aware of the limited number of observations included in the analysis (42) and we are cautious when making inferences about the causal relationships. We run three regression models: (1) with the two main effects hypothesised in this article, (2) a model with the main effects and those controls that highly correlate with the use of clientelism and (3) a model with the main effects and all controls. In the analysis, the outcomes are estimates (averages per county) and there is some uncertainty associated with them. As such, we compute alternative heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors that allow us to account for the uncertainty associated with using estimates as outcomes (Lewis and Linzer Citation2005). We observe that the model with the uncorrected standard errors and the model with standard errors adjusted to be heteroscedasticity-consistent provide similar results. We report the model with uncorrected errors since there is no statistically significant heteroscedasticity in our data. The test for multi-collinearity shows that the independent variables and controls are not highly correlated: the highest value of the correlation coefficient is 0.51 (margin of victory and share of unemployed people in the county) and the VIF values are lower than 1.94.

Political parties and clientelism in Romania

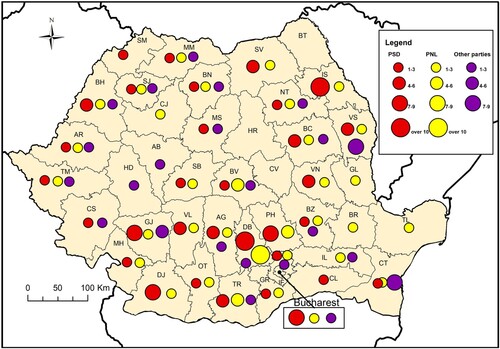

The use of clientelism in the 2020 elections continues a practice documented for roughly 15 years. Although in 2016, the Campaign Finance Guide elaborated by the electoral authority put an end to any gifts (Permanent Electoral Authority Citation2016) and a law that punishes the use of clientelism, electoral clientelism continued to be used. presents cases of electoral clientelism documented in the national media for both local and national elections between 2012 and 2020. They are supplementary data used exclusively for illustrative purposes and they are not included in the analysis. We collected the data systematically from national and local press outlets (the online version) and the dots reflect the frequency of unique cases. When one case was reported by several media outlets, we do not count it twice. The red (PSD) and yellow (PNL) dots indicate that almost every county is targeted by at least one of these two parties. Very often, the two parties target the same counties. The distribution also illustrates that other parties also use clientelism in many constituencies. There are several constituencies in which none of the two major parties use clientelism but where other parties do that. This broad category of “other” includes the main political parties running in those elections at local and national levels; two of these are UDMR and USR, which are included in this analysis. There is only one constituency in which there is no clientelism documented by local or national media (BT).

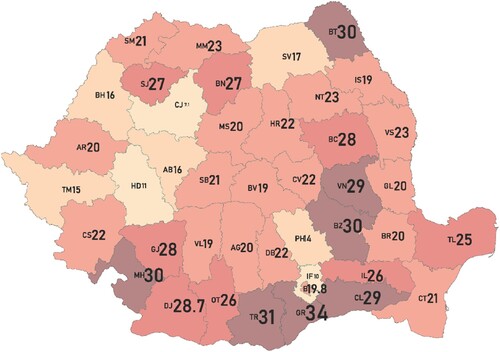

depicts the use of electoral clientelism across the Romanian counties, based on the answers to the survey. There is great variation between the counties. At one extreme, only 7% of the respondents in Cluj (CJ) county acknowledged the offering of clientelistic inducements to their acquaintances during the 2020 election campaign. At the other extreme, 34% of the respondents in Giurgiu (GR) county claimed that they knew someone who was offered clientelistic goods by political parties. The average percentage of clientelism for the 42 observations (41 counties plus the capital city Bucharest) is 22. This means that throughout the country one in five citizens is offered clientelistic inducements by political parties in exchange for his/her vote.

This overview indicates that clientelism is used to a similar extent in electoral strongholds and in swing counties. For example, Arad (AR) is a swing county that had three winners in the elections under scrutiny: PDL in 2008, PSD in 2016 and PNL in 2020. Arges (AG) is an electoral stronghold of the PSD, which won the most votes in all three elections. Both counties have the same level of electoral clientelism (20%). Other examples of the minimum and maximum values of clientelism illustrate the same thing. Cluj (CJ) is an electoral stronghold of the PNL, while Hunedoara (HD) is a swing county. They both have comparable values of electoral clientelism: 7.1 and 11. At the upper limit of clientelism, Giurgiu (GR) is a swing county in which PNL and PSD alternate in winning the popular vote. Teleorman (TR) is an electoral stronghold of the PSD. The two counties have comparable use of clientelism: 34 and 31.

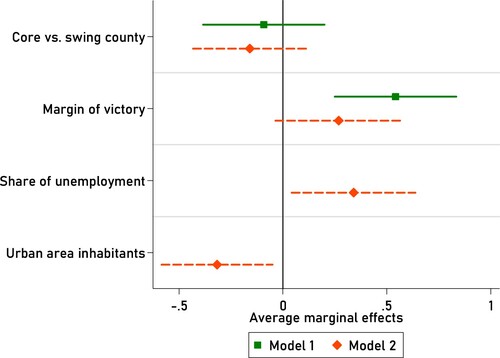

The correlation and regression coefficients in substantiate this observation. There is a very weak positive correlation between core counties and the use of clientelism. This indicates that electoral strongholds may be targeted slightly more than swing counties. However, this relationship is weak and unstable because it changes in the regression analysis when we introduce other variables. For example, when we have a high margin of victory (model 1), the swing counties appear to be targeted more by clientelism. None of these statistics is significant at the accepted levels. These findings indicate that electoral clientelism is used to a similar extent in both core and swing counties.

Table 1. Multivariate regressions for the use of clientelism.

Model 1 includes only the main effects and explains 27% of the use of clientelism at the county level in Romania. Model 2 includes the main effects, the share of unemployment and the percentage of urban area inhabitants since these were the controls with the highest correlation coefficients. This model explains 45% of the variation of clientelism at the county level. Model 3 adds the remaining controls, but their effect is very small and they do not contribute to the explained variance.Footnote4 This has the same value as Model 2. As such, for reasons related to parsimony and to fewer variables in a statistical model with a relatively small N, we focus on Models 1 and 2.

depicts the average marginal effects. Model 1 includes the two main effects and indicates that the type of county (H1) has a weak negative effect, not statistically significant (see ) on the use of clientelism. This means that political parties use slightly more clientelism in those counties that are swing compared to the core (electoral strongholds). The weak effect of the type of constituency can be explained through the electoral system used in elections. Romania uses a closed-list PR with a redistribution of seats at the national level. In theory, winning constituencies does not create a major difference in seat allocation. It is likely to win the elections at the national level without winning the majority of constituencies as long as a runner-up the margin of victory is small in many constituencies. In practice, this has not happened so far and the party winning the elections at the national level won most constituencies.

The margin of victory (H2) has a strong and positive effect on the use of clientelism: The counties in which there was a large difference of votes between the winning party and the runner-up in the 2016 elections are targeted heavily by electoral clientelism compared to those counties where the difference of votes was small. The relationship is strong and statistically significant at the 0.01 level and holds across the regression models 2 and 3 when controlling for the other variables. For example, the Alba (AB) county was very competitive in 2016 and the difference between the two parties was 1.36%. Its level of clientelism is 16 (). In contrast, Buzau (BZ) had a difference of vote shares of 52.97% in 2016 and 30 for the use of clientelism. In all the counties with the use of clientelism 30 or above, the difference in vote shares is higher than 40%.

One explanation for the intensive targeting of the counties with high margins of victory in 2016 is that clientelism fulfils two functions. The winners from 2016 provided clientelistic inducements to their supporters to mobilise them also in the 2020 elections, to ensure that they turn out to vote or do not swing. The challengers used clientelism in the 2020 elections to try to persuade some of the voters to swing, but also to appeal to their voters or to the voters of parties other than the winner. In their case, since the winners use inducements, clientelism can provide a cushion against a bigger fall. In other words, they do not win the elections if they use clientelism, but they may lose voters if they do not. The electoral competition is accompanied by clientelism in many counties with a clear winner, which puts pressure on the other political parties running in those counties.

The main effects hold when controlling for unemployment and urban population in Model 2, but they are somewhat weaker for the margin of victory. This is partly because the share of unemployment and the percentage of inhabitants in the urban area per county have strong and significant effects. The share of unemployed people indicates that clientelism targets to a large extent those counties in which individuals have limited access to jobs. One form of positive clientelism considered in this article is the promise of jobs after elections, which speaks directly to this problem. High unemployment means poor access to resources in general. These findings confirm previous research that refers to the ways in which political parties target deprived communities to get electoral support in the short term and/or generate voting loyalty in the medium to long term.

Clientelism is used extensively in Romanian counties with low percentages of the urban population. The rural area is targeted mode by clientelism for at least two reasons. First, the rural communities are small and socially cohesive and the local patrons (who provide clientelism) are easily identifiable. The identification rests on previous interactions and often on affective ties established between the patron and the client (voter). These ties lead to reciprocity, which is more achievable in rural areas (Finan and Schechter Citation2012). Such ties are also conducive to adherence and commitment to a clientelistic exchange because monitoring is relatively easy in rural communities (Koter Citation2013). Second, the clientelistic linkages involve norms of deference and loyalty in rural areas especially when these are characterised by low literacy or modes of communication. The local patron can act as a connection with the outside world (Cinar Citation2016). The rural areas in Romania face important socio-economic challenges. Compared to urban areas, the average income is roughly 25% lower, the access to daily facilities such as water is 10–15% lower, and the level of employment is half (Fina, Heider, and Raț Citation2021).

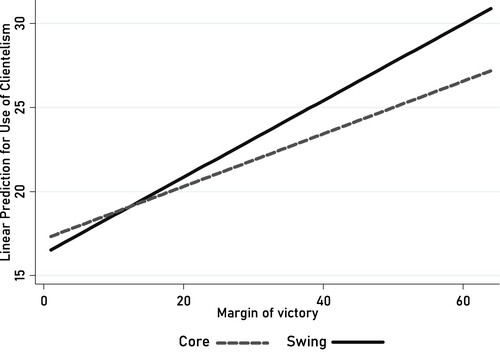

provides supplementary evidence that the clientelistic targeting works similarly across the core and swing counties. It includes the adjusted prediction for the use of clientelism according to the margin of victory. It compares the core and swing counties. Confidence intervals are excluded for a better visualisation, i.e. the lines of the confidence intervals overlap and are difficult to observe. The graph indicates that the trajectories are similar and clientelistic offerings increase in both types of counties proportional to the distance of votes between the top two competitors. In the swing counties the effects of the margin of victory are somewhat stronger especially in those instances with a very clear winner. In the tight races, the level of clientelism in the core counties is slightly higher than in the swing counties. At a difference of roughly 15% between the top competitors, the levels of electoral clientelism are equal in the core and swing counties.

Conclusion

This article aimed to explain the effects of constituency type and margin of victory on the use of clientelism at the constituency level in the 2020 legislative election in Romania. The results indicate that electoral clientelism is used to a similar extent in core and swing constituencies, but the real difference is made by the margin of victory. The existence of clear winners in the previous elections favours high levels of clientelistic inducements in those constituencies. The winners seek to augment their control, while the runner-up and other competing parties seek to narrow the distance of votes or even win the constituency. To some extent, these reactions can be associated with a bandwagon process in which the winner sets a trend that is followed by the competitors. The effect is similar in both core and swing constituencies, which means that parties employ general clientelistic strategies rather than confining it to their own or to the opposition’s electorate. Equally important, these effects hold when controlling for economic deprivation and the share of the population in urban areas.

This article makes several contributions that advance our understanding of electoral clientelism. Theoretically, it develops an argument about how the limited competition in constituencies influences the extent to which political parties use clientelistic inducements to win votes. This argument engages directly with the point of competing clientelistic machines (Weitz-Shapiro Citation2014) and explains that, unlike what was claimed in the literature, the large margins of victory in previous elections could determine parties to use clientelism. Empirically, we show that there is no difference between core and swing constituencies regarding the use of clientelism in the elections organised in a PR system with national redistribution. We also illustrate that parties’ strategies under high margins of victory are used consistently across constituencies when controlling for the development and structure of communities. In this sense, we contradict the conclusions of previous studies according to which high competition drives electoral clientelism.

By pointing at the margin of victory as a potential explanation for the use of clientelism, we add context to research in settings characterised by weak partisanship. We suggest that in addition to links with underdevelopment, previous research ignored the strategic context in which political parties make their targeting decisions. This article moves the discussion about who and how is targeted beyond the types of incentives (Corstange Citation2018). It indicates that the bigger picture of competition matters in a way that major wins or defeats encourage political parties to use clientelism. This taps into the idea of elections as repeated iterations between parties and voters, which are not “all or nothing” contests. Political parties that win big have incentives to engage in electoral clientelism to continue winning and maintaining their dominant position. At the same time, parties that suffer major defeats in constituencies may use clientelism either to limit the scale of electoral disaster or to narrow the gap from the winner. Both approaches create a cycle that is detrimental to political representation in particular and democracy in general.

One limitation of our analysis is the limited number of units of observation (i.e. counties). Further comparative work, either cross-sectional or longitudinal, can address this shortcoming and outline the robustness of these findings. It would be relevant to learn how electoral clientelism develops across constituencies in countries that use a different electoral system. Along similar lines, future research could use individual-level data to reflect the extent to which voters react to party behaviours. While this requires fine-grained information collected through surveys, our findings illustrate that the variation in the use of clientelism deserves intensive exploration. Another avenue for further research could include a qualitative component in which interviews are conducted with party representatives in charge of electoral strategies. These could inform about the reasons behind the use of clientelism and identify the importance paid to the electoral competition within a constituency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sergiu Gherghina

Sergiu Gherghina is an Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the Department of Politics, University of Glasgow. His research interests lie in party politics, legislative and voting behavior, democratization, and the use of direct democracy.

Claudiu Marian

Claudiu Marian is an Assistant Professor at the Department of International Studies and Contemporary Politics, Babes-Bolyai University Cluj. His research interests are political marketing, political parties and electoral behaviour.

Notes

1 Other potential measures such as NGO reports or expert assessments are not available. The media reports used in the overview of the Romanian case do not provide comparable information about clientelism in all the counties.

2 We skipped the 2012 elections because in those elections the first two major parties in the country – the social democrats and the liberals (PNL) – formed an electoral alliance that won roughly 60% of the votes and the vast majority of counties.

3 The existence of strongholds is calculated in the context of limited experience with elections (three decades) and high electoral volatility in Romania. The same winner in three elections over the most recent 12 years shows stable preferences in that county.

4 In model 3, the absence of an effect of the party winning in 2020 on the use of clientelism may be surprising especially that the large parties in the country are associated with the use of clientelism. The limited effect is reflected by the evidence in (widespread use of clientelism by many parties) and by a question from our survey in which we asked the respondents to identify the political parties providing the clientelistic offers during the campaign to their acquaintances. The respondents identified all parliamentary parties as sources of clientelism: PSD (14.6%), PNL (10.6%), USR (7.1%) and UDMR (6.2%).

References

- Auyero, Javier 1999. “‘From the Client’s Point(s) of View’: How Poor People Perceive and Evaluate Political Clientelism.” Theory and Society 28 (2): 297–334. doi:10.1023/A:1006905214896

- Calvo, Ernesto, and Maria Victoria Murillo. 2013. “When Parties Meet Voters: Assessing Political Linkages Through Partisan Networks and Distributive Expectations in Argentina and Chile.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (7): 851–882. doi:10.1177/0010414012463882

- Carreras, Miguel, and Yasemin İrepoğlu. 2013. “Trust in Elections, Vote Buying, and Turnout in Latin America.” Electoral Studies 32 (4): 609–619. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.07.012

- Casey, Katherine. 2015. “Crossing Party Lines: The Effects of Information on Redistributive Politics.” American Economic Review 105 (8): 2410–2448. doi:10.1257/aer.20130397

- Chiru, Mihail, and Sergiu Gherghina. 2012. “When Voter Loyalty Fails: Party Performance and Corruption in Bulgaria and Romania.” European Political Science Review 4 (1): 29–49. doi:10.1017/S1755773911000063

- Cinar, Kursat. 2016. “A Comparative Analysis of Clientelism in Greece, Spain, and Turkey: The Rural–Urban Divide.” Contemporary Politics 22 (1): 77–94. doi:10.1080/13569775.2015.1112952

- Collier, Paul, and Pedro C. Vicente. 2012. “Violence, Bribery, and Fraud: The Political Economy of Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Public Choice 153 (1–2): 117–147. doi:10.1007/s11127-011-9777-z

- Corstange, Daniel. 2018. “Clientelism in Competitive and Uncompetitive Elections.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (1): 76–104. doi:10.1177/0010414017695332

- Cox, Gary W., 2009. “Swing Voters, Core Voters, and Distributive Politics.” In Political Representation, edited by Ian Shapiro, Susan Stokes, Elisabeth Wood, and Alexander S. Kirshner, 342–357. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cox, Gary W., and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1986. “Electoral Politics as a Redistributive Game.” Journal of Politics 48 (3): 370–389. doi:10.2307/2131098

- Dahlberg, Matz, and Eva Johansson. 2002. “On the Vote-Purchasing Behavior of Incumbent Governments.” American Political Science Review 96 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1017/S0003055402004215

- Dassonneville, Ruth, and Dieter Stiers. 2018. “Electoral Volatility in Belgium (2009–2014). Is There a Difference Between Stable and Volatile Voters?” Acta Politica 53 (1): 68–97. doi:10.1057/s41269-016-0038-5

- Deuskar, Chandan. 2020. “Informal Urbanisation and Clientelism: Measuring the Global Relationship.” Urban Studies 57 (12): 2473–2490. doi:10.1177/0042098019878334

- Diaz-Cayeros, Alberto, Federico Estevez, and Beatriz Magaloni. 2016. The Political Logic of Poverty Relief.Electoral Strategies and Social Policy in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dixit, Avinash, and John Londregan. 1996. “The Determinants of Success of Special Interests in Redistributive Politics.” Journal of Politics 58 (4): 1132–1155. doi:10.2307/2960152

- Finan, Frederico, and Laura Schechter. 2012. “Vote-Buying and Reciprocity.” Econometrica 80 (2): 863–81.

- Fina, Stefan, Bastian Heider, and Cristina Raț. 2021. România inegală. Disparităţile socio-economice regionale din România [Unequal Romania. The Regional Socio-Economic Disparities in Romania]. Bucharest: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Gans-Morse, Jordan, Sebastián Mazzuca, and Simeon Nichter. 2014. “Varieties of Clientelism: Machine Politics During Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (2): 415–432. doi:10.1111/ajps.12058

- Gherghina, Sergiu. 2013. “Going for a Safe Vote: Electoral Bribes in Post-Communist Romania.” Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 21 (2–3): 143–164. doi:10.1080/0965156X.2013.836859

- Gherghina, Sergiu. 2014. Party Organization and Electoral Volatility in Central and Eastern Europe: Enhancing Voter Loyalty. London: Routledge.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, and Sorina Soare. 2021. “Electoral Performance Beyond Leaders? The Organization of Populist Parties in Postcommunist Europe.” Party Politics 27 (1): 58–68. doi:10.1177/1354068819863629

- Gherghina, Sergiu, and Clara Volintiru. 2017. “A New Model of Clientelism: Political Parties, Public Resources, and Private Contributors.” European Political Science Review 9 (1): 115–137. doi:10.1017/S1755773915000326

- Gonzalez-Ocantos, Ezequiel, Chad Kiewiet de Jonge, Carlos Meléndez, Javier Osorio, and David W. Nickerson. 2012. “Vote Buying and Social Desirability Bias: Experimental Evidence from Nicaragua.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (1): 202–217. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00540.x.

- Hagene, Turid. 2015. “Political Clientelism in Mexico: Bridging the Gap Between Citizens and the State.” Latin American Politics and Society 57 (1): 139–162. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2015.00259.x

- Hicken, Allen. 2011. “Clientelism.” Annual Review of Political Science 14 (1): 289–310. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220508

- Hicken, Allen, Edward Aspinall, Meredith L. Weiss, and Burhanuddin Muhtadi. 2022. “Buying Brokers. Electoral Handouts Beyond Clientelism in a Weak-Party State.” World Politics 74 (1): 77–120. doi:10.1017/S0043887121000216.

- Kao, Kristen, Ellen Lust, and Lise Rakner. 2017. Money Machine: Do the Poor Demand Clientelism? 14. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3581811

- Keefer, Philip. 2005. “Democratization and Clientelism: Why are Young Democracies Badly Governed?” Working Paper 3594. Washington, DC.

- Koter, Dominika. 2013. “Urban and Rural Voting Patterns in Senegal: The Spatial Aspects of Incumbency, c. 1978–2012.” Journal of Modern African Studies 51 (4): 653–679. doi:10.1017/S0022278X13000621

- Larreguy, Horacio, John Marshall, and Pablo Querubín. 2016. “Parties, Brokers, and Voter Mobilization: How Turnout Buying Depends Upon the Party’s Capacity to Monitor Brokers.” American Political Science Review 110 (1): 160–179. doi:10.1017/S0003055415000593

- Larreguy, Horacio, John Marshall, and Laura Trucco. 2012. Breaking Clientelism or Rewarding Incumbents? Evidence from an Urban Titling Program in Mexico.

- Lewis, Jeffrey B., and Drew A. Linzer. 2005. “Estimating Regression Models in Which the Dependent Variable is Based on Estimates.” Political Analysis 13 (4): 345–364. doi:10.1093/pan/mpi026

- Lindberg, Staffan I., and Minion K. C. Morrison. 2008. “Are African Voters Really Ethnic or Clientelistic? Survey Evidence from Ghana.” Political Science Quarterly 123 (1): 95–122. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2008.tb00618.x

- Loughlin, Neil. 2020. “Reassessing Cambodia’s Patronage System(s) and the End of Competitive Authoritarianism: Electoral Clientelism in the Shadow of Coercion.” Pacific Affairscific Affairs 93 (3): 497–518. doi:10.5509/2020933497

- Lust, Ellen. 2009. “Competitive Clientelism in the Middle East.” Journal of Democracy 20 (3): 122–135. doi:10.1353/jod.0.0099

- Magaloni, Beatriz. 2006. Voting for Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival and its Demise in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mares, Isabela, and Lauren E. Young. 2018. “The Core Voter’s Curse: Clientelistic Threats and Promises in Hungarian Elections.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (11): 1441–1471. doi:10.1177/0010414018758754

- Mares, Isabela, and Lauren E. Young. 2019. Conditionality and Coercion: Electoral Clientelism in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marian, Claudiu. 2018. “The Social Democrat Party and the use of Political Marketing in the 2016 Elections in Romania.” Sfera Politicii 26 (3–4): 70–82.

- Muñoz, Paula. 2014. “An Informational Theory of Campaign Clientelism: The Case of Peru.” Comparative Politics 47 (1): 79–98. doi:10.5129/001041514813623155

- Nichter, Simeon. 2008. “Vote Buying or Turnout Buying? Machine Politics and the Secret Ballot.” American Political Science Review 102 (1): 19–31. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080106

- Nichter, Simeon. 2010. “Politics and Poverty: Electoral Clientelism in Latin America.” PhD Dissertation. University of California, Berkeley.

- Permanent Electoral Authority. 2016. Ghidul finanţării campaniei electorale la alegerile locale din anul 2016. https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/geydmmbshezq/ghidul-finantarii-campaniei-electorale-la-alegerile-locale-din-anul-2016-din-18042016.

- Piattoni, Simona, ed. 2001. Clientelism, Interests, and Democratic Representation: The European Experience in Historical and Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poteete, Amy R. 2019. “Electoral Competition, Clientelism, and Responsiveness to Fishing Communities in Senegal.” African Afairs 118 (470): 24–48. doi:10.1093/afraf/ady037

- Rauschenbach, Mascha, and Katrin Paula. 2019. “Intimidating Voters with Violence and Mobilizing Them with Clientelism.” Journal of Peace Research 56 (5): 682–696. doi: 10.1177/0022343318822709.

- Rohrschneider, R. 2002. “Mobilizing Versus Chasing: How Do Parties Target Voters in Election Campaigns?” Electoral Studies 21 (3): 367–382. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(00)00044-5

- Schaffer, Joby, and Andy Baker. 2015. “Clientelism as Persuasion-Buying: Evidence from Latin America.” Comparative Political Studies 48 (9): 1093–1126. doi:10.1177/0010414015574881

- Schedler, Andreas, and Frederic Charles Schaffer. 2007. “What is Vote Buying?” In Elections for Sale: The Causes and Consequences of Vote Buying, edited by Frederic Charles Schaffer, 17–30. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Stokes, Susan C. 2005. “Perverse Accountability: A Formal Model of Machine Politics with Evidence from Argentina.” American Political Science Review 99 (3): 315–325. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051683

- Stokes, Susan C. 2009. “Political Clientelism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by Charles Boix and Susan C. Stokes, 604–627. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stokes, Susan C., Thad Dunning, Marcelo Nazareno, and Valeria Brusco. 2013. Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism: The Puzzle of Distributive Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sugiyama, Natasha Borges, and Wendy Hunter. 2013. “Whither Clientelism? Good Governance and Brazil’s Bolsa Família Program.” Comparative Politics 46 (1): 43–62. doi:10.5129/001041513807709365

- Szwarcberg, Mariela. 2015. Mobilizing Poor Voters. Machine Politics, Clientelism, and Social Networks in Argentina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Weghorst, Keith R., and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2011. “Effective Opposition Strategies: Collective Goods or Clientelism?” Democratization 18 (5): 1193–1214. doi:10.1080/13510347.2011.603483

- Weghorst, Keith R., and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2013. “What Drives the Swing Voter in Africa?” American Journal of Political Science 57 (3): 717–734. doi:10.1111/ajps.12022

- Weitz-Shapiro, Rebecca. 2012. “What Wins Votes: Why Some Politicians Opt Out of Clientelism.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (3): 568–583. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00578.x

- Weitz-Shapiro, Rebecca. 2014. Curbing Clientelism in Argentina: Politics, Poverty, and Social Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yıldırım, Kerem, and Herbert Kitschelt. 2020. “Analytical Perspectives on Varieties of Clientelism.” Democratization 27 (1): 20–43. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1641798

Appendix 1

Table A1. The descriptive statistics for the variables included in the analysis (N = 42).