ABSTRACT

Grzegorz Ekiert argues that the organisational trajectory of civil society in Poland has fundamental features directing it towards political polarization. According to the author, Polish civil society has evolved into an organisational form that can be described as a “pillarized civil society”. Despite the formulation of a strong thesis for “pillarized civil society”, it has not yet been empirically verified. Using a selection of protest events from daily newspapers, I use social network analysis to map the protest coalitions of 2020. I pose the question to what extent coalitions of protest in Polish civil society form a pillarised, vertical structure.

Introduction

As noted by Cohen and Arato (Citation1992), the idea of civil society in Eastern Europe was revived in the 1970s as a result of the emergence of new opposition movements and the revival of organisations building autonomous and horizontal social networks. Their leaders defined civil society in opposition to a totalitarian state. The strongly emphasised elements of this discourse, rooted in nineteenth-century liberalism, included the idea of human rights, the concept of an individual's inalienable freedom, non-violence, and the recognition of public debate as a means of conflict resolution (Ekiert and Kubik Citation2001). The basis of democracy was understood as spontaneous social organisation and a spirit of cooperation, through which people would be able to implement the ideals of self-organisation at a local level. This construct was also defined by the concept of desired cooperation between the state and society. The Solidarity Movement was meant to be the embodiment of these ideals and, above all, the link that would unite citizens across political divisions and class differences (Osa Citation2003).

Following the fall of communism, during the 1980s and 1990s, the idea of civil society became entrenched in the discourse of successive governments. As a result, states, development agencies and foundations in Western Europe supported the construction of a liberal civil society as the best remedy for social inequalities, weakness of local governments, and the shortcomings of democratic institutions. Foundations, in an effort to build a civil society according to Western fashion, have increased support for national and international NGOs in an attempt to institutionalise partnerships between grassroots organisations and the state in the delivery of public services (Ekiert, Kubik, and Wenzel Citation2017).

Countering this dominant discourse, Ekiert (Citation2020) claims that scholars have overlooked the actual structural directions of the development of Polish civil society, which were far removed from the assumptions of the political ideology of systemic transformation. From the beginning of the democratic transformation in 1989, Polish civil society, instead of representing various political circles opening up to each other, has evolved towards closing in on itself. Instead of the anticipated broad collaboration, we observed their increasing autonomy and the strengthening of ties between social organisations and political parties. The deepening of cultural and political polarisation followed. Polish civil society has evolved into an organisational form that can be described as “pillarized civil society” – civil society which is vertically segmented and marked by extreme cultural and political polarisation.Footnote1

The concept of pillarisation advocated by Ekiert has several characteristics (Citation2020) that were adopted here. First of all, he sees the origins of this phenomenon in the culture wars of the 1980s and 1990s. The new conservative movements and civic groups emerging at the time were integral part of the global retreat from Western liberal democratic norms. In many countries in the postcommunist worlds these movements were closely aligned with illiberal political actors. The formation of separate pillars (liberal and conservative) has been reinforced by the digital revolution. According to Ekiert (Citation2020), the burgeoning social media scene has facilitated the process of pillarisation, enabling the construction of distinct “cultural silos” with their own narratives, symbols and internal communications. Consequently, the intensified exchange of information translated into a growing ability of such environments to mobilise protests. This had serious consequences for the shape of the political scene in the former Eastern Bloc countries. Political life is governed by a vision of a zero-sum game, which weakens moderate centrist political parties. All forces are directed at weakening their political opponent and providing their side with the resources needed for political mobilisation. In such configuration the illiberal pillar is particularly bent on supporting radical populist parties. When populist parties get into parliament, the liberal pillar is deprived of resources and public funds are redirected to conservative organisations. As indicated by Ekiert a further consequence of this condition is that “[…] the legal framework regulating civil society activities is purposefully altered to restrict the liberal pillar and to expand opportunities for illiberal movements and organizations”.

The consequence of such a process is the re-etatization of one of the pillars, which means, in the Polish case, the strengthening of ties between the conservative political parties and the sector of organisations they support. According to the author, this process deepened further after 2015, when the parliamentary coalition of the United Right [Zjednoczona Prawica], led by the Law and Justice party, implemented the “good change” [dobra zmiana] programme. The ruling coalition made personnel changes in many public institutions, including the civil service, state-owned companies, the judiciary, and cultural institutions. These changes did not bypass the non-governmental organisation sector either and aimed to eradicate the civil society elites favoured by the former liberal government (Bill Citation2020). In other words, the ideal of liberal democracy in which citizenship is a virtue that mandates political participation is reduced to a sphere encompassed by participation in only one type of pillar, which has a well-defined core of political identity. Such structural configuration facilitates coalitional protest mobilisation of far-right, nationalist and conservative religious movements, as well as opposing, left and liberal actors.

In this study, I propose to extend the concept of pillarisation to collective actions. In this sense, we can understand pillarisation as a structural configuration linking political elites (parliamentary political parties) with protest actions. The concept of “pillarized protest” is based on three dimensions: (1) horizontal; (2) vertical and (3) the roles of political parties as brokers. Pillarisation means including various organisations and social movements – from conservative and extreme-right to left and liberal origins – into the stream of protests. Furthermore, organisational circles in the extra-parliamentary arena enjoy the support of groups exercising state power: political parties and non-governmental organisations associated with the ruling coalition. I hypothesise that “pillars of protest” will consist not only of strong horizontal ties between actors cooperating in coalitions and sharing similar goals and ideological positions, but also vertical ties to corresponding political parties, which will integrate various smaller protest communities. Vertical actors also have certain brokerage roles in the overall network. The three dimensions of pillarisation will be described in detail in the operationalisation section of this study.

In 2020, extraordinary political opportunities have arisen for the formation of broad protest coalitions, which should, according to the theory adopted here, reflect the pillar shape of protesting civil society. Most notably, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the government introducing regulations which provoked objections from many social groups. Dozens of existing organisations that had not been active in the streets before, as well as new initiatives that formed directly in response to new regulations, mobilised in response to government actions. The right side of the political spectrum reacted particularly fiercely, entering into coalitions with organisations protesting against the closure of small businesses and the anti-vaccination movement. In April, the Law and Justice government took advantage of anti-Covid regulations that restricted the freedom of public assembly and introduced a ban on abortion. The informal Women's Strike [Strajk Kobiet] movement quickly mobilised opponents of the anti-abortion law. Protests against the tightening of the abortion law were joined by dozens of organisations that had no involvement with this issue in the past. As part of the nationwide protest in major Polish cities, repertoires such as car rallies, street-blocking, and “queue protests” – during which protesters line up in long queues – were utilised (Kowalewski Citation2020). In August, a wave of mass protests in defence of the repressed LGBTQ activist Margot commenced. Throughout the year, left-wing protesters opposed the interference of the Roman Catholic Church in public affairs and scandals related to sexual abuse within the institution, the destabilising of the education system by the Minister of Education, and the government's further attempts to gain control of the courts. Leftist movements were opposed by pro-life coalitions and far-right activists. Disgruntled farmers also carried out protests along with entrepreneurs, who organised a nationwide campaign under the banner of the “Entrepreneurs’ strike!”. The context introduced by the coronavirus pandemic created a set of social issues that all sectors of civil society had to deal with, and the state became the target of accusations and attacks. As a result, the pandemic, instead of hindering civic activity, only intensified it. The 2020 protests focused on social issues that had built up since 2015, during the rule of the Law and Justice government. The issue of abortion was nothing new, but the government's sudden decision to introduce an almost entire ban sparked massive protests. Similarly, the issue of LGBTQ rights has long occupied activists from various social organisations, from student initiatives to left-wing political parties, but the government's repression of LGBTQ activists reinforced the alliance between organisations typically involved with other issues.

This study presents an empirical analysis of the phenomenon of “pillarization of protest”, which is a manifestation of the wider phenomenon of “pillarization of civil society” described by Ekiert (Citation2020). This is the first analysis to show the relationship between protest coalitions, political parties, and social organisations in Poland. I combine the protest event analysis (PEA) research technique with social network analysis. In order to determine to what extent the 2020 protest coalitions were internally cohesive and what role political parties played in the integration of coalition actors, I will map the network of actors participating in the protests. I employ social network measures such as centralisation, betweenness, and brokerage roles to demonstrate the degree of internal cohesion and top-down integration of protesting actors by political parties. The analysis is based on a unique set of data on protest events and coalition networks in 2020.

Given the explorative approach of this study, it is important to be wary of drawing conclusions that are too far-reaching. Since I cannot compare different time periods, I am unable to discover their durability over time. Due to the lack of a comparative period, this study focuses on measures of internal cohesion of pillars and measures of vertical integration of the field, instead of coalition-forming patterns. A more advanced time-oriented analysis is needed to identify the extent to which differences between protest coalitions can be generalised beyond the case of the year 2020.

Political parties and protest coalitions

McAdam, Tilly, and Tarrow (Citation2001) emphasised the need to understand the relationship between movements and political parties, as “the two sorts of politics interact incessantly and involve similar causal processes” (6–7). The interactions between movements and parties are often mutually beneficial: social movements provide mass support during elections, helping mobilise people to vote for a particular party (McAdam and Tarrow Citation2010; Schlozman Citation2015). In turn, political parties legitimize movements and support their goals in the field of extra-parliamentary politics (Kriesi Citation2004, Citation2015). The analysis of these relations has become an important area of research in the contemporary sociology of social protests (Heaney and Rojas Citation2015; Skocpol and Williamson Citation2012). The adoption of social network analysis has allowed researchers to investigate how social movements are related to each other and to other types of organisations (Diani Citation2003). Interactions between parties and social movements take place not only among the elites, where individuals act as intermediaries (Schlozman Citation2015), but also during collective actions, where politicians represent political parties by participating in demonstrations (Heaney and Rojas Citation2007, Citation2011). These relationships evolve over time as a result of changes in the structures of political opportunities, which can both improve and limit the mobilisation of social movements and political parties (Meyer and Minkoff Citation2004; Tarrow Citation1998).

In many Western democracies, the relationships between parliamentary and non-parliamentary spheres have recently been strengthened. This process has been particularly noticeable in Germany in the revival of the extreme right (Akkerman, de Lange, and Rooduijn Citation2016; Mudde Citation2016; Muis and Immerzeel Citation2017). In combination with the growing importance of the anti-Islamic protest movement PEGIDA (Stier et al. Citation2017), the anti-immigration party Alternative for Germany (AfD) achieved an unprecedented election result. Another example is the conservative campaign in the United States, followed by the presidency of Donald Trump, which was marked by anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric and accompanied by protests of white nationalists from the “alt-right” movement (Nagle Citation2017).

Borbath and Hutter (Citation2020) argue that increasing participation of political parties in protest activities within European societies – resulting from weaker democratic institutions – is even more evident in Central and Eastern Europe. A good example is Hungary, where the shift towards authoritarian rule has coincided with the political changes occurring in Poland. Since 1998, the Hungarian parliamentary system has been one of the most institutionalised systems in the region (Pirro et al. Citation2021). This is a result of voters’ persistent alignment with two main parties – the national-conservative Fidesz and Magyar Szocialista Part (the Hungarian Socialist Party – MSZP). The 2006 elections significantly undermined the Hungarian left; MSZP began to decline in the face of political scandals and allegations of introducing drastic cuts in social spending (Enyedi Citation2015). The breakthrough 2010 elections ensured the domination of Fidesz and allowed the far-right Jobbik Magyarorszagírt Mozgalom (Jobbik: Movement for a Better Hungary) to enter parliament. Ever since, the dominance of the right has gone unchallenged, and benefited from the continued support of more than two-thirds of the electorate voting for one of these two right-wing parties in the subsequent national parliamentary elections.

In Poland, the two-party conflict on the political scene has been growing since 2001. In 2005, the largest social democratic party (SLD) joined the opposition, and the Law and Justice party won the elections and established a government. For two consecutive terms (2007–2015), Law and Justice was the largest opposition party to the liberal government of Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska – PO). In 2015, Law and Justice managed to win a parliamentary majority again. As Kotwas and Kubik (Citation2019) argue, the intensification of the existing nationalistic and religious tendencies in some sections of Polish society created the possibility of deepening the fundamental dichotomy promoted by Law and Justice – the clash between the “corrupt elites of the liberal establishment” and the “nation” and “church”. Hostility towards “gender ideology”, “cultural neo-Marxism” and LGBTQ rights were the other key factors in the conservatives’ war against liberal civil society in both Poland and Hungary (Jacobsson and Korolczuk Citation2017). Simultaneously, the United Right government led by Law and Justice began implementing reforms aimed at conservative “reinforcement” of civil society organisations. To this end, the National Freedom Institute [Narodowy Instytut Wolności], whose primary goal was to free the sector from the domination of liberal values and the financial influence of foreign foundations, was established in 2017. In practice, this means the promotion of Catholic organisations, support for communities associated with the Catholic Church, and financing extreme right-wing organisations (i.e. the Independence March) (Graff and Korolczuk Citation2021). The result of Law and Justice propaganda activities is the deep polarisation of public opinion into two factions: the nationalist-Catholic camp, which adopted the narrative of the far-right groups from the period of the first Law and Justice period in government (2005–2007), and the liberal camp, which supports democratic values and the policies of the European Union.

Fringe parties and protest coalitions

Following the 2015 parliamentary elections, another important phenomenon related to pillarisation surfaced – fringe parties. Electoral systems in Central and Eastern Europe favour the existence of many minority parties on the edges of mainstream coalitions (Bakke and Sitter Citation2003). The smaller parties orbiting the periphery of large government and opposition parties are often referred to as fringe parties (Arzheimer Citation2011; Wodak Citation2015). These are frequently single-issue parties focusing on populist messages aimed at ensuring quick electoral success (Daniel Citation2016, 807). Such parties emerged in both Poland and Hungary. In Hungary, Jobbik is the largest party of this kind and, in recent years, it has been repositioning moving closer or further from its largest political partner, Fidesz (Pirro et al. Citation2021). In Poland, on both sides of the political divide, a number of small parties have emerged in recent years. These parties have either entered parliament or remained closely connected to parliamentarians, but not all of them have been single-issue parties. For example, on the left-liberal side there is Polish Initiative [Inicjatywa Polska], established in 2019; considering itself a centrist party Poland 2050 [Polska 2050], originating from the political movement of the same name the social democratic Spring [Wiosna], established in 2019; and older, small political parties, such as the Green Party [Zieloni], and the left-wing Razem [Together]. On the right side of the political spectrum, there are also some smaller groups that belong to parliamentary opposition, but most groups support the ruling coalition. These include Confederation [Konfederacja] and Kukiz’15, which was formed as an organisation promoting the introduction of single-mandate electoral districts.

Parties of this type are particularly relevant for the purposes of this analysis. I hypothesise that fringe political parties will play an important role in the formation of a coalition around the right- and left-wing pillars and may serve as a bridge between the largest parliamentary parties and social groups organising protests.

Operationalization and hypotheses

Researchers of social movements endeavour to understand how protest coalitions are formed and under what circumstances they lead to successful collective actions (Van Dyke and McCammon Citation2010). Some authors emphasise that coalitions are formed on the basis of a shared ideology, collective identity, or shared frames (Snow Citation2006; Van Dyke and McCammon Citation2010; Pfaff Citation1996). The sense of collective identity creates unity among the participants and leads to the establishment of more rigorous actions in the name of particular goals. A common ideology can be the strongest foundation upon which different actors create long-lasting protest coalitions (Poletta and Jasper Citation2001). This arrangement allows coalition partners to work towards a common goal, putting aside other issues on which their opinions differ. Sometimes, however, collaboration fails despite such similarities. In interwar Europe, ideological differences prevented the socialist, communist and anarcho-syndicalist parties from joining forces against fascism (Berman Citation2006). In other cases, coalitions may function without a shared ideology and identity, relying solely on strategic alliance (Behrooz Citation2012). Coalitions based solely on ideology and purely strategic coalitions are two extremes that rarely occur in reality. Much more often we observe coalitions that are formed somewhere in between these extremes, but the pillarised structure of protest examined in this study is one rare example of such an extreme protest coalition. I argue that if within a given social environment coalitions are formed in a “pillarized” manner, the actors will form groups based on their common affiliation to a single political pole. This results from the structure of the political and social world in which these organisations function. Organisations will protest together within a single pillar, even if political opportunities encourage actors from different backgrounds to undertake joint, strategic protest actions.

Consequently, hypothesis 1 will state that the boundaries of each pillar are impenetrable and based on specific internal identity (i.e. political ideology embodied in the protested claims and political identity of the organisations appearing in coalitions).Footnote2 Thus, pillar affiliation is defined on the basis of supporting one of the political environments (despite possible internal differences) and, joining smaller or larger protest coalitions within the wider environment (highlighted by community detection algorithm). In this sense, the existence of separate network components is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the existence of pillars. There is also a need to determine the “strength” of consistency of the identified environments that make up the pillars.

To define to what extent we are dealing with consistent protest environments, which can be conceptualised as pillars I refer to two analytical concepts that correspond to the aforementioned dimensions of analysis: cohesion (horizontal dimension) and integration (vertical dimension) of the protest coalition. Social network analysts have long argued that cohesion between network actors is a prerequisite for agreement on how and why they should act together (Friedkin and Johnsen Citation2011). Cohesion is typically measured by the degree to which actors are connected through meaningful relationships. The more individuals are connected through interpersonal ties, the easier it is to exchange information and reduce uncertainty (Reagans and McEvily Citation2003). In cohesive networks, the members are usually more involved in the activities of the organisation (Diani and McAdam Citation2003, 307), and the possibilities for coordinated and long-term actions are increased (Osa Citation2003, 24). Many existing analyses have operationalised cohesion as the strength of ties between actors expressed through network centralisation (Osa Citation2003; Diani Citation2015), where centralisation “measures the dispersion of centralization scores relative to the most central score in the network” (Sinclair Citation2011, 30).

According to this notion, a star-shaped network is the network with the most unequal degree of centralisation for any number of actors (Freeman Citation1979). In such a network, all actors except the central actor have a relationship degree of one, and the central actor has a relationship degree equal to the number of all actors minus one. By this definition, a star-structured network is most conducive to collective action. In such networks, the pressure to mobilise emanates from the centre. In the operationalisation adopted here, I use this understanding of centralisation to demonstrate the level of cohesion in which a given political environment will take on the pillar shape. From this I derive the second hypothesis:

H2: If we are really dealing with a pillar-shaped coalition, it will be a highly centralized (cohesive) network (over 50%), as described above.

Some predictions can also be made about the cohesion of the network on the right and left side of the political spectrum. As substantiated by Gattinara and Pirro (Citation2019, 451), far-right parties in Europe not only regularly garner strong electoral support, but also mobilise local communities around their goals. Strong interaction between organisations at the national and local levels fosters a deep consolidation of the far right around the largest groups and parties. Platek's analyses (Citation2020) covering the years 1990–2013 indicate that in the extreme right movement strong consolidation takes place over time, as the configuration of protesting organisations in the coalitions has not changed over the years. A similar phenomenon has not yet been identified in relation to left-wing/liberal organisations, despite the greater interest of scholars in studying social movements in progressive organisations rather than the extreme right (Rydgren Citation2007). These arguments suggest another hypothesis:

H3: Both political pillars should be characterized by a high degree of centralization, but the right-wing pillar will be stronger as it has long been consolidated around central organizations.

The vertical dimension (integration) concerns the interaction between two indirectly related actors. Some individual actors are able to influence other actors through their special position in the network. It is therefore an influence that organisations have indirectly on other organisations within the network. In the coalition protest network, the central position is occupied by those organisations that integrate a given protest environment by playing the role of intermediaries in establishing links between relatively distant organisations. The best-known measure for value networks that reflects this concept is “flow betweenness centrality” (Freeman, Borgatti, and White Citation1991). Centralisation of this type is based on the assumption that the actors will use all the links (in our case, protest events) that connect them proportionally to the length of those links. The coefficient of centralisation of a given actor within the network is measured by the proportion of the flow of each pair of actors in the entire network (i.e. flowing through all links connecting them, and not just the shortest paths as in the case of betweenness centrality) (Borgatti Citation2005). Thus, hypotheses 4 and 5 state:

H4: Pillarized coalitions will be strongly integrated through intermediaries (over 50%), approaching the maximum level of the star-shaped structure.

H5: The right-wing pillar will be more integrated than the liberal/left pillar.

Let us now turn to the hypotheses related to the role played by political parties in the structure of protest coalitions. This is an individual dimension of the network, which consists in tracking the position of individual actors in the structure. Although the entire network may be consolidated or integrated to a low degree, some organisations may have more “power” stemming from centralisation. In other words, even if there is a low degree of centralisation (cohesion) and flow betweenness centralisation (integration) in the overall structure, some actors may still be more relevant than others. When it comes to pillarised protest, political parties will be such actors. Hypothesis 6 predicts that:

H6: Political parties (especially fringe parties) will play a much greater role as actors contributing to the cohesion and integration of the pillars than other types of protesting organizations.

Simultaneously, and in line with the previous predictions:

H7: Political parties will concentrate more integration and cohesion in the right-wing pillar than in the liberal/left pillar.

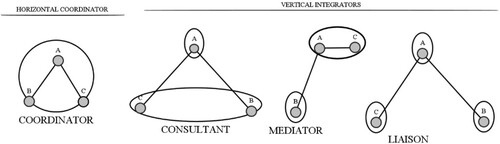

However, this is not all when it comes to analysing individual actors. With regard to the concept of network integration, it will also be useful to identify the specific role that political parties can play in integrating protest communities within pillars. I build upon an analytic strategy designed by Gould and Fernandez (Citation1989) to identify five types of brokers in directed networks (see ).Footnote3 The coordinator appears when an actor connects two other actors, and all three actors are members of the same group (community). A broker that belongs to one group and connects two other actors who are members of another group is a consultant. The five types of brokerage roles have been conceived for directed networks. Note, however, that the direction of relations is only needed to distinguish between the representative and the gatekeeper. The other brokerage roles are also apparent in undirected relations, so we can apply the brokerage roles to undirected networks if we do not distinguish between representatives and gatekeepers. Instead, actors combining gatekeeper and representative functions are positioned in relation to other groups of actors acting as mediators for cooperation between their group of organisations and outside organisations, regardless of the direction of ties. The last role is the liaison, which occurs when all three actors belong to different groups.

From the point of view of this analysis, the roles within the network can be either vertical or horizontal. The role of the horizontal coordinator does not fulfil the integrative function, because the actor only coordinates activities within its group (that is, it contributes to the cohesion of only one group). The proper integrating function occurs for the other three roles, which is why it is so important to observe the behaviour of individual actors. Information about the centralities of particular actors does not provide us with knowledge of their role in relation to various protest communities (clusters, see ). Here, I hypothesise that:

H8: Political parties (especially fringe parties) within both analysed pillars will play primarily vertical roles, being the main integrators between various organisations taking part in the 2020 protests.

As before, I predict that:

H9: Right-wing parties will play a greater part in performing vertical roles than liberal and left-wing parties.

Data and method

The basic unit of analysis used in the study is a protest event. Such events fall within the scope of “unconventional” political participation that takes place in the streets (Hutter Citation2014). Events can range from peaceful demonstrations to violent demonstrations and blockades (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999; Kriesi and Koopmans Citation1995). In preparing the codebook, a list of expressions used by the press to describe protest events was created. The list was based on the press-tagging algorithm used in the Event Registry project (http://eventregistry.org/) run by the University of Ljubljana. The Event Registry allows for the identification of repertories describing collective actions most often appearing in Polish press and television. Next, using the online archives of Gazeta Wyborcza, the largest Polish liberal daily newspaper, I searched for mentions in the newspaper's archives containing the above-mentioned repertories (phrases) describing the protests. Each examined month was supplemented with the electronic databases of Rzeczpospolita, a nationwide economic and legal journal established in 1920 as a medium for the conservative Christian National Party. The operation of Rzeczpospolita in its current form was launched in 1982. Currently, Rzeczpospolita is a centre-right leaning daily. The addition of the second source allowed for minimising the risk of bias in the description and selection of events by a single source with a specific political profile (Hug and Wiesler Citation1998; Barranco and Wisler Citation1999).

However, since the Rzeczpospolita contained only a small percentage of mentions of the 2020 protests, we decided to use local editions of the Gazeta, which ensures that all major protests and protests in smaller cities in 2020 are coveredFootnote4. It is important to mention that there is a debate in the literature about the representativeness of the data obtained from the daily press and the numerous biases in the coverage of events (e.g. reporting mainly on events happening in larger cities or events containing violence, etc.). For the research presented here, as with previous studies of Polish protest, Gazeta Wyborcza appears to be the best available source of information on protests as it contains only a slight bias toward reporting events from major cities and no identified overrepresentation of events containing violence (see Platek Citation2020; Platek and Plucienniczak Citation2017).

All data was manually reviewed and cleared of mentions containing the searched word but not describing actual protest events (e.g. interviews with activists often contained the words “demonstration”, “manifestation”, etc. but did not refer to specific events in 2020). Further selection of protest events was governed by four principles: (a) Since the aim is to collect protest events, only those events that contained more than one participant were taken into account; (b) The second rule for qualifying an event to the database of protest events was the necessity of its taking place in public space (streets, squares, etc.)Footnote5; (c) The events had to contain clearly articulated claims against identifiable targets or in support of specific issues, i.e. they had to meet the definition of an episode of contention (see: McAdam, Tilly, and Tarrow Citation2001) as a specific form of interaction between actor A and actor B, where actor B is usually an institution holding some kind of power. In this case the state was the main actor to whom civil society actors were addressing their claims. These kinds of claims accounted for over 70% of registered events; (d) since my goal was to reconstruct the network of coalitions; only events with at least two unique actors were selected for the sample. The resulting database contains 107 actors participating in a total of 86 coalitional events, which accounted for nearly 50% of all coded events (n = 174). In the group of coalition events, all recorded events were directed against the state or various state agencies (including the Catholic Church linked to the ruling elite). This may be due to the specific circumstances in which they took place (COVID pandemic and government regulations), nevertheless the revealed coalitions indicate the pillar-like nature of the protest structure as pillarisation is linked to political action.

The first step in the analysis was to create a matrix for a bimodal network showing the relationship between actors and events in 2020. On average, 3.6 organisations participated in a single event (minimum 2, maximum 15, standard deviation 2.48). The next step was the procedure of data affiliation, i.e. transformation of a bimodal network into a unimodal network, illustrating the relationships between organisations through the events in which they participated together. The cross-product method offered by the UCInet package (Borgatti, Martin, and Freeman Citation2002) was used. The subsequent result is a unimodal, undirected, valued network showing the distribution of the co-occurrence of actors in protest events.

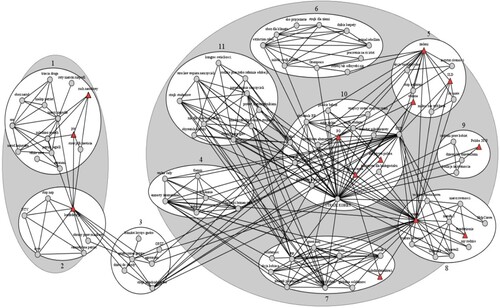

Finally, the Louvain community detection algorithm, which exploits the principle of modularity to discover latent communities within networks, is used (Blondel et al. Citation2008). The Louvain algorithm seeks to optimise the value of ties by assigning nodes to communities so that as many ties as possible appear within and as few as possible between communities. This step identifies distinctive protest communities, referring to groups of actors that share high similarity scores. The network graph is presented in .

Research findings

In 2020, well-defined protest spaces of liberal/left and right-wing circles emerged (). However, despite the clearly defined boundaries, they were not entirely separate components. They were related to cluster (community) number 3, which included the strike of small business owners, an organisation acting on behalf of farmers, an association of gastronomy workers, a trade union (OPZZ), and an association of parents dissatisfied with online education. These organisations were hesitant to take sides. Their supporters participated both in demonstrations organised by the right-wing Confederation party and in Women's Strike protests. They mainly opposed the Covid-19 sanitary regulations introduced by the government, limiting the possibility of running businesses. During the Women's Strike protests, they joined in chanting of anti-government slogans.

The existence of a cluster connecting the pillars proves that favourable political opportunities such as pervasive and burdensome government regulations provide, among organisations lacking a strong political identity, an opportunity to join protests on both sides of the political spectrum. Nevertheless, the protest coalition networks take the shape of two components containing different types of organisations – social movements, associations, and political parties – with a clearly identifiable ideological identity.

The left side of depicts right-wing coalitions (communities 1 and 2). A characteristic feature of this side of the protest coalition network is the division into long-standing far-right organisations (community 1) and new organisations (community 2) with an anti-vaccination and nationalist profile (e.g. NTV). In the extreme-right component, we will find the largest and oldest extreme-right organisations protesting together. These include: All-Polish Youth [Młodzież Wszechpolska], National-Radical Camp [Obóz Narodowo Radykalny] and National Movement [Ruch Narodowy], as well as neo-Nazis from the autonomous movement, the informal organisation White Crew and the Third Position [Trzecia Droga]. At the centre of the graph is the March of Independence, a cyclical event organised by an association of the same name. It is devoted to the celebration of Polish Independence Day, and attracts tens of thousands of participants every year, including far-right organisations from abroad. In 2020, participants ostentatiously broke the “no gatherings of more than five people” rule introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were acts of violence, damage to property, and slogans chanted against sanitary regulations.

The same community also includes representatives of the Law and Justice party, who are members of the ruling coalition. They protested together with the National Movement and the All-Polish Youth. The new party, Confederation (registered in 2019), took the central position in community 2. Confederation brings together experienced political leaders from the extreme right (members of the National Movement), as well as libertarians from smaller parties that have, for a number of years, formed the political base of the extreme right that has been more or less successful in parliamentary elections. The party was founded as an election committee; in 2020 it had 11 deputies in parliament. It is easy to notice that Confederation is the link between the clusters of the old far right and the “cluster of the undecided” dominated by small business owners. The political nature of this party positions it as a typical fringe party. Its programme is a combination of populist and free-market postulates (e.g. drastic tax cuts for entrepreneurs) with the anti-immigrant rhetoric of the far right. Interestingly, all parties within this network component have representatives in parliament. In this sense, the component is closely related to the parliamentary area.

There are 75 actors on the liberal/left side, compared to 20 actors on the right. This is a much larger component, with eight separate protest communities. Community 6 is dominated by environmental organisations. In cluster 11, associations of parents fighting against the state reform of education are clearly present. Community 4 includes judicial organisations opposing the judicial reform carried out by the Law and Justice government. Communities 5, 7, 8 and 9 mainly include LGBTQ organisations and informal groups of feminist activists. The community in the centre of the component (10) focuses on the Women's Strike and includes organisations that have most often entered into coalitions with the Strike. On the one hand, these are radical left organisations such as the radical youth organisation Sharp Green [Ostra Zieleń], the anarchist trade union Workers’ Initiative [Inicjatywa Pracownicza], and on the other, civil society organisations with liberal origins, such as KOD (Committee for the Defence of Democracy), or Obywatele RP (Citizens of the Republic of Poland). This is also a community that contains the most significant left-wing political parties. As in the case of right-wing coalitions, they all have parliamentary representation, and Civic Platform is the largest Polish liberal oppositional party. In the neighbouring community there are other left-wing parties: Together (Razem), SLD (Democratic Left Alliance) and Spring (Wiosna). They also have representatives in parliament, except for their youth wings, which are treated as political parties here (Przedwiośnie – Early Spring, and Młodzi Demokraci – Young Democrats). The component on the right side of the graph contains easily identifiable political actors that fall on a continuum from radical left to liberal. Some of the communities inside the component highlighted by the Louvaine algorithm are “cleaner” in terms of the content of a particular type of actor. For example, cluster number 6 contains only left-wing environmental organisations, and cluster number 4 contains judicial organisations protesting court reform and working mainly with liberal organisations. Other highlighted clusters do not have such clear ideological assignments, mixing actors with leftist and liberal orientations.

shows that there is little cohesion within the liberal/left network component (12.4%). The entire network is far from concentrating all links on one or just a few organisations. However, some actors stronger than others may be identified, and two actors stand out here: the Women's Strike and the slightly weaker Together party, which are almost twice as strong as the next two strongest organisations (KOD and Kongres Kobiet/Congress of Women). This indicates that the power of attracting protest coalitions is slightly greater in the Women's Strike community (10), because it also contains KOD. If we examine the power of political parties in the left/liberal component, 10 parties account for almost 17% of the cohesion of the entire network, while the Women's Strike alone accounts for almost 10% of its total cohesion, regardless of the kind of organisation.

Table 1. Global and individual levels of cohesion and integration.

On a global level, integration is slightly stronger, 31% of contacts between organisations in the entire liberal/left network are mediated by other organisations. Almost 70% of organisations are directly connected through events in which they participated. Organisations that are stronger than others in integrating the liberal/left space of protests can also be distinguished. The strongest actor again is the Women's Strike (20.6% of the entire network). The four other strong organisations (the Greens, Greenpeace, Together Party, and the environmental activist group Extinction Rebellion) are almost four times weaker than the Women's Strike. Thus, the Women's Strike plays a dominant role, both as a network cohesion centre and its integrator. However, if we take into account global network centralisation, both of these effects turn out to have little impact on the pillarisation of the coalition. As in the case of the cohesion, political parties are responsible for just 18% of total integration within the network, and this is mainly due to the two largest parties with a similar power of integration: Together Party and the Greens.

In relation to hypotheses 2 and 4 posed at the beginning of this article, one can hardly consider the left-wing component as strongly pillarised. The dimensions of cohesion and integration are rather weak and indicate the dispersion of these powers between the various actors of the protests in 2020, rather than the construction of protest coalitions focused on a few organisations. Nevertheless, some parties have a stronger position within the network than other types of organisations, even despite the clear dominance of Women's Strike in the 2020 protest coalition. This seems consistent with hypothesis H6, at least in relation to the left pillar of the protests.

The right side of the political spectrum is almost twice as centralised in terms of cohesion (22%). However, as in the previous case, cohesion does not reach the degree assumed by the second hypothesis. Political parties are also stronger – they are responsible for 21% of the cohesion of the entire network. Confederation is responsible for over 60% of this effect among parties. If we take into account all cohesion, regardless of the kind of organisation, Confederation will be responsible for as much as 13% of the entire network's cohesion. Confederation is the strongest node, attracting coalitions with other organisations. As we remember, all 10 parties on the left side of the political spectrum accounted for just 17% of the entire network's cohesion. Compared to the left side of the political spectrum, the right side of the coalitional protests, while it did not achieve the assumed degree of centralisation to be considered a fully pillarised structure, is much more concentrated around a single political party. Thus, although few parties on the right side of the political spectrum take part in the protests, one of them is almost as powerful as all the parties on the liberal/left side. Therefore, hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

Within the network, almost 58% of organisations protest directly with each other, and 42% of coalition interactions are mediated by other organisations. Hence, hypothesis 4 is not confirmed, but the pillar closely follows the assumed level of integration, which confirms hypothesis 5. Confederation also plays an important role here. Together with other parties, it accounts for as much as 42% of the total strength of network integration. If we look at it individually, we will see that it is responsible for as much as 70% of the integration power among the parties and 31.5% of integration power of the entire network. Both cohesion of the network and network integration are predominantly concentrated on one actor, Confederation, whose integration influence is particularly noticeable, since it is greater than that of the strongest organisations in the liberal/left component of the network. This is consistent with hypotheses 6 and 7.

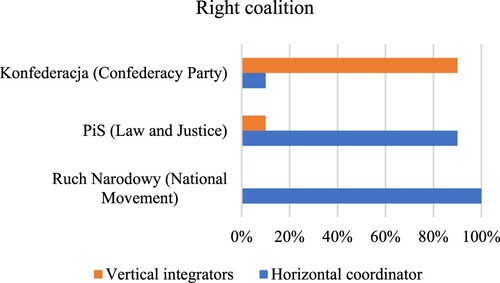

Confederation's integrative role in the coalition protest network will become even more evident when we look at individual parties’ brokerage roles between different protest communities (which confirms hypothesis 9). demonstrates that Confederation is the only party playing the role of a vertical integrator. Other parties focus their efforts on internal (horizontal) coordination of protests in their own community. Without Confederation, the entire component of the right-wing protests would collapse into the new and old organisational components. Since it does not coordinate protests horizontally, Confederation is not deeply embedded in any protest milieu. Instead, it is a flexible political player, combining the various protest claims acceptable within a right-wing political agenda. Its populist message establishes the Confederation as an actor which both strengthens the pillarisation of the right protest coalitions, and as an indispensable actor upon which the existence of the entire protest component depends.

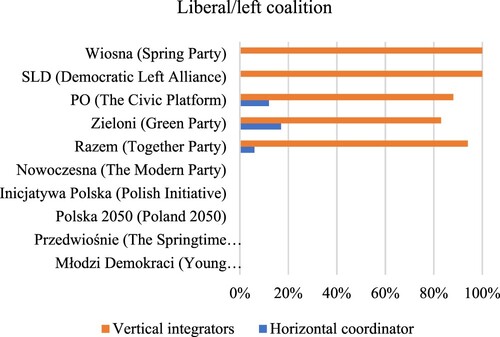

The role of vertical integrator prevails among the left-wing and liberal parties, which is in line with hypothesis 8. However, some also have a certain percentage of horizontal coordinators roles within their communities (). Due to poor positioning within protest circles, two left-wing parties – Spring and SLD – do not play any coordinating horizontal role. Five parties play no brokerage role, either with their closest protest neighbours or with organisations from other protest communities. If we consider the power of political parties’ brokerage (not shown), Together and the Greens will be the strongest integrators for the network, as well as strong protest coordinators within their own communities.Footnote6 Thus, these two parties stand out from other organisations of this type in relation to global and local roles, integrating organisations across the network and coordinating their local protest communities.

Each protesting community in the left/liberal component features several actors with a similar set of roles, with some communities having more organisations with stronger coordination roles, as opposed to integration roles. Certain protest communities form denser communities, which suggests that they may have a long history of participating in joint protest actions. In this respect, a community of environmental organisations (6), a community of feminist organisations (7) and a community of LGBTQ organisations (8) are noticeable. Thanks to the analysis of brokerage roles, we know that Extinction Rebellion (an environmental activist group) focuses mainly on organising protests within its own protest milieu; as such, it is almost 100% a horizontal broker. The same is true of the feminist community, where the trade union Sierpień ‘80 [August ‘80] and the informal group of activists Queerowy Maj [Queer May] stand out as horizontal brokers. In the latter, besides Together – a strong horizontal coordinator – there are also actors who devote their activities exclusively to coordinating protests. These include the Equality March [Marsz Równości] and Tęczowa Częstochowa [Rainbow Częstochowa].

To put it in quantitative terms, none of the sides in the political spectrum exceeded the assumed threshold of pillarisation at the global level. Nonetheless, the two network components analysed in this study differ in the degree of cohesion and integration of the protest structure. With regard to the role of political parties, there are even greater differences between the two coalitional structures. Characteristically, the largest political parties with parliamentary representation from each side of the political spectrum are visible during the protests. The strength of their ties with other organisations within the coalition is also evidenced by the presence of various protest environments united in almost ideal separate network components (disregarding intermediary community 3). Indeed, it is easy to imagine that the organisations presented in are protesting only within their own communities, and never form coalitions with ideologically similar actors. It should also be noted that, as expected, the major parliamentary parties (Law and Justice, and Civic Platform) play a marginal role within protest coalitions. Smaller parties that flank the two sides of the political contention in parliament turned out to be much stronger, some of them contributing significantly to the pillarisation of the protest coalitions.

Furthermore, between left and right protest coalitions, we also observe significant differences. A single political party that plays a cohesive and integrative role in the protests visibly dominates the right side of the political spectrum. In addition, Confederation was the strongest carrier of the vertical integrator brokerage role, connecting the old far right with new nationalists and small business owners. Thus, the right-wing coalition was indeed pillarised, fulfilling the assumption of the domination of one political party. On the left side, the actors focused on the Women's Strike, which occupied the central position of its cluster in attracting protests from various circles and creating a coalition component. Two other parties were also important on the left, although still relatively weaker than Confederation. Together and the Greens, being part of different protest communities, were at the forefront of the integrational role in their component. They also had an important coordinating function within their own communities.

As predicted, the pillarised protest manifested itself more strongly on the right side of the political scene, indicating the importance of one party in cementing the whole environment. The role of parties was more nuanced in the context of the left/liberal protest coalition. Most of them had little relevance as actors forming a cohesive coalition that would resist being broken up. Only two parties played more substantial roles in contributing both to coordinating their own communities and integrating protesting communities within the whole pillar.

Conclusion

This article has examined patterns of segmentation in building protest coalitions in Polish civil society. The general results confirm the formulated hypotheses that the structure of relations in Polish civil society is centred around two political forces. The left and right strengthen relations with their allies through various types of connections and exchanges of resources. These structures are reproduced in various institutional spaces: in the government and social arena and during collective protest actions. The latter are a kind of litmus test reflecting the intensity of political contention in other arenas. Examining the overall field of protest actions allows us to determine how intensive and durable political conflicts are. Pillarisation is best revealed when representatives of various social groups directly express their claims and political views.

In light of my assumptions, the 2020 protests did not create a strong pillarised structure, but some features of this kind of structure are noticeable. On the one hand, Polish protests in 2020 may resemble what some authors call an “event coalition” – short-lived coalitions which are “created for a particular protest or lobbying event” (Levi and Murphy Citation2006; Tarrow Citation2005). On the other hand, the protests in 2020 were more than just a simple response to emerging political opportunities; they reflected long-term structural relations radiating from other areas of civil society, a deep socio-political conflict centred around a government fighting against certain sections of civil society and supporting others. The strong presence of political parties during the protests confirms this diagnosis.

As Pirro et al. argue (Citation2021, 24), an analysis of the relationship between Hungary's mainstream party Fidesz and fringe party Jobbik helped to

understand the underlying practices of fringe actors striving to become mainstream; it casts light on the foothold and links of these actors with the grassroots subaltern operating outside of the mainstream and institutional spheres; and finally, it is illustrative of the inherent fluidity between fringe and mainstream.

Second, the article contributes to the development of a new conceptual framework for theorising collective action – a network configuration of collective actions as an integral component of civil society. I propose to move beyond the “sectoral model” of civil society, which locates them in a specific social sphere created by voluntary clubs and associations. Such civil society is understood as a sector of distinct social organisations and institutions that can be distinguished from family, state and economy. It seems that in today's changing world, the rigid, sectoral model of civil society is more capable than ever of grasping the complexities and connections between various social activities (Freise and Hallmann Citation2014). Organisations often cross the boundaries between sectors and even question the very notion of separate, distinct spheres. Moreover, the ideals of voluntary associations and citizenship are refuted by an unprecedented wave of populism, while such “voluntary associations” often carry out violent disintegration of citizenship.

Third, further holistic analyses of the activities of Polish civil society depend on the available data. Most datasets are limited to a few years or a single year of protest. Due to their sources, which are mainly national press agencies, large data pools focusing on protests in Europe, such as POLDEMFootnote7, only have information about events in the largest cities. This prevents a more detailed analysis of the frequency of protests taking place in smaller towns. In order to accurately trace the formation of a pillarised protest and distinguish its permanence over time from the influence of “moments of protest”, we need a dataset covering the years 2010–2020. Such a time frame would allow us to capture the impact of the Law and Justice Party taking power in 2015 – the most important political change that occurred in that period – on the strengthening of pillarised protest in Polish civil society. This creates an important challenge for protest research, which should be central to the general research agenda, not only for the case of Poland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Platek

Daniel Platek – He works in the Institute of Political Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences. He has a longstanding interest in historical sociology, analytical sociology, collective action and social movements theory. His recent publications include Beyond Strikes? Regime and Repertoire of Workers' Protests in Poland 2004–2016 (2022) and Analytical Historical Sociology (2022).

Notes

1 The concept of pillarisation is well-known in the social sciences, especially in relation to Dutch society (Sniderman and Hagendoorn Citation2007). Pillarisation (verzuiling) originated there in the late nineteenth century and became the most dominant feature of social organization by the early twentieth century (Ertman Citation2000). Five distinct social segments, each represented by a political party, constituted pillars of the social structure in the Netherlands: Liberals (secular and middle class), Catholics, orthodox Protestants (Calvinist and Dutch Reformed Church), and social democrats representing the values and interests of industrial labour. However, the concept of pillarisation has never been precisely operationalized. The main characteristic features of pillarisation are vertical segmentation (representation of each segment by a political party) and internal cohesion of each pillar. Individuals within one pillar do not generally interact with individuals in another pillar.

2 It should be noted that the pillar coalition is founded on a shared ideology or on ideological proximity, however, patterns that deviate from complete ideological consistency can be observed over a longer period of time. In this respect, the “pillarized protest” may be a derivative of a certain structural dependence and the resulting configuration of the common pattern of protest of individual organizations. In this article, I emphasize ideological consistency and organizational similarity because, as I mentioned earlier, there are no comparative periods presented here.

3 Since the networks analysed here differ in size, and one of them (right-wing network) contains smaller numbers of relations and does not have high density, final scores consist of brokerage values divided by expected values given group sizes. This approach is called “relative brokerage”, because we examine the actual brokerage relative to the random expectation. Utilizing this approach, we can get a better sense of which parts of which actors roles are significant when the profile of a given actor differs greatly from what could be expected just by chance.

4 Gazeta Wyborcza covered 90% of all obtained protests events. Only Rzeczpospolita contained 3% of unique mentions. The sources shared 7% of all mentions.

5 It was difficult to distinguish between events that took place over several consecutive days. Because many of the events in 2020 – especially those related to the Women's Strike – took place over multiple days, I adopted the interval of a one-day break separating the events. Actors participating in one event could, therefore, join it for numerous consecutive days.

6 The Civic Platform also presents the same combination of roles expressed in percentages, but is not a strong broker.

References

- Akkerman, Tjitske, Sarah de Lange, and Matthijs Rooduijn. 2016. Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream? London: Routledge.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2011. “Fringe Parties.” In The Encyclopedia of Political Science, edited by George Kurian, 639–642. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Bakke, Elisabeth, and Nick Sitter. 2003. “Why do Parties Fail? Cleavages, Government Fatigue and Electoral Failure in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary 1992–2012.” East European Politics 29 (2): 208–225. doi:10.1080/21599165.2013.786702.

- Barranco, Jose, and Dominique Wisler. 1999. “Validity and Systematicity of Newspaper Data in Event Analysis.” European Sociological Review 15 (3): 301–322. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018265.

- Behrooz, Maziar. 2012. “Iran After Revolution (1979–2009).” In The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History, edited by Toiraj Daryaee, 133–164. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Berman, Sheri. 2006. The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe’s Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bill, Stanley. 2020. “Counter-Elite Populism and Civil Society in Poland: PiS’s Strategies of Elite Replacement.” East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 20 (10): 1–23. doi:10.1177/0888325420950800.

- Blondel, Vincent, Jean-Loup Guillaume, Renaud Lambiotte, and Etienne Lefebvre. 2008. “Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 12 (10): 34–40. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008.

- Borbath, Endre, and Sven Hutter. 2020. “Protesting Parties in Europe: A Comparative Analysis.” Party Politics 3 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1177/1354068820908023.

- Borgatti, Steve, Everett Martin, and Linton Freeman. 2002. Ucinet for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis. Harvard, MA: Analytic Technologies.

- Borgatti, S. P. 2005. “Centrality and network flow”. Social Networks 27 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2004.11.008.

- Cohen, Jean, and Andrew Arato. 1992. Civil Society and Political Theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Daniel, William. 2016. “First-order Contests for Second-Order Parties? Differentiated Candidate Nomination Strategies in European Parliament Elections.” Journal of European Integration 38 (7): 807–822. doi:10.1080/07036337.2016.1200569.

- Diani, Mario. 2003. “Leaders or Brokers? Positions and Influence in Social Movement Networks.” In Social Movements and Networks: Relational Approaches to Collective Action, edited by Mario Diani and Doug McAdam, 105–122. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Diani, Mario. 2015. The Cement of Civil Society: Studying Networks in Localities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Diani, Mario, and Doug McAdam2003. Social Movements and Networks: Relational Approaches to Collective Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ekiert, Grzegorz. 2020. Civil Society as a Treat to Democracy. Center for European Studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Ekiert, Grzegorz, and Jan Kubik. 2001. Civil Society from Abroad: The Role of Foreign Assistance in the Democratization of Poland. Working Paper of Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ekiert, Grzegorz, Jan Kubik, and Michał Wenzel. 2017. “Civil Society and Three Dimensions of Inequality in Post-1989 Poland.” Comparative Politics 49 (3): 331–350. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26330961. doi:10.5129/001041517820934230

- Enyedi, Zsolt. 2015. “Plebeians, Citoyens and Aristocrats or Where is the Bottom of Bottom-up? The Case of Hungary.” In Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. Colchester, edited by Hanspeter Kriesi and Takis Pappas, 229–224. Florence: ECPR Press 4.

- Ertman, Thomas. 2000. “Liberalization, Democratization and the Origins of a ‘Pillarized’ Civil Society 19th Century Belgium and the Netherlands.” In Civil Society Before Democracy, edited by Nancy Bermeo and Phillio Nord, 355–364. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Freeman, Linton. 1979. “Centrality in Social Networks Conceptual Clarification.” Social Networks 1: 215–239. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7.

- Freeman, Linton, Steve Borgatti, and Douglas R. White. 1991. “Centrality in Valued Graphs: A Measure of Betweenness Based on Network Flow.” Social Networks 13 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(91)90017-N.

- Freise, Matthis, and Thorsten Hallmann. 2014. Modernizing Democracy. In Associations and Associating in the Twenty-First Century. New York, NY: Springer.

- Friedkin, Noa, and Eugene Johnsen. 2011. Social Influence Network Theory: A Sociological Examination of Small Group Dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gattinara, Pietro, and Andrea Pirro. 2019. “The far Right as Social Movement.” European Societies 21 (4): 447–462. doi:10.1080/14616696.2018.1494301.

- Gould, Roger, and Robert Fernandez. 1989. “Structures of Mediation: A Formal Approach to Brokerage in Transaction Networks.” Sociological Methodology 19 (3): 89–126. doi:10.2307/270949.

- Graff, Agnieszka, and Elżbieta Korolczuk. 2021. Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment. London: Routledge.

- Heaney, Michael, and Fabio Rojas. 2007. “Partisans, Nonpartisans, and the Antiwar Movement in the United States.” American Politics Research 35 (4): 431–464. doi:10.1177/1532673X07300763.

- Heaney, Michael, and Fabio Rojas. 2011. “The Partisan Dynamics of Contention: Demobilization of the Antiwar Movement in the United States, 2007–2009.” Mobilization 16 (1): 45–64. doi:10.17813/maiq.16.1.y8327n3nk0740677.

- Heaney, Michael, and Fabio Rojas. 2015. Party in the Street: The Antiwar Movement and the Democratic Party After 9/11. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hug, Simon, and Dominique Wiesler. 1998. “Correcting for Selection Bias in Social Movement Research.” Mobilization 3 (2): 141–161. doi:10.17813/maiq.3.2.6ptv3133154x28n5.

- Hutter, Sven. 2014. “Protest Event Analysis and its Offspring.” In Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research, edited by Donatella Della Porta, 335–367. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jacobsson, Kerstin, and Elżbieta Korolczuk. 2017. “Introduction.” In Civil Society Revisited: Lessons from Poland, edited by Kerstin Jacobsson and Elżbieta Korolczuk, 1–39. London: Berghahn Books.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and Paul Statham. 1999. “Political Claims Analysis: Integrating Protest Event and Political Discourse Approaches.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 4 (2): 203–221. doi:10.17813/maiq.4.2.d7593370607l6756.

- Kotwas, Marta, and Jan Kubik. 2019. “Symbolic Thickening of Public Culture and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism in Poland.” East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 33 (2): 435–471. doi:10.1177/0888325419826691.

- Kowalewski, Maciej. 2020. “Street Protests in Times of COVID-19: Adjusting Tactics and Marching ‘as Usual’.” Social Movement Studies 19 (1): 127–143. doi:10.1080/14742837.2020.1843014.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2004. “Political Context and Opportunity.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by David Snow and Sarah Soule, 67–90. Malden: Blackwell.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2015. “Party Systems, Electoral Systems, and Social Movements.” In The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements, edited by Donatella Della Porta, 101–123. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Ruud Koopmans. 1995. New Social Movements in Western Europe: A Comparative Perspective. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Levi, Margaret, and Gillian Murphy. 2006. “Coalitions of Contention: The Case of the WTO Protests in Seattle.” Political Studies 54: 651–670. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00629.x.

- McAdam, Doug, and Sidney Tarrow. 2010. “Ballots and Barricades: On the Reciprocal Relationship Between Elections and Social Movements.” Perspectives on Politics 8 (2): 529–542. doi:10.1017/S1537592710001234.

- McAdam, Doug, Charles Tilly, and Sidney Tarrow. 2001. Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meyer, David, and Debra Minkoff. 2004. “Conceptualizing Political Opportunity.” Social Forces 82 (4): 1457–1492. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3598442. doi:10.1353/sof.2004.0082

- Mudde, Cass2016. The Populist Radical Right: A Reader. London: Routledge Press.

- Muis, Jasper, and Tim Immerzeel. 2017. “Causes and Consequences of the Rise of Populist Radical Right Parties and Movements in Europe.” Current Sociology 65 (6): 909–930. doi:10.1177/0011392117717294.

- Nagle, Angela. 2017. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the AltRight. Winchester: John Hunt Publishing.

- Osa, MaryJane. 2003. Solidarity and Contention. Networks of Polish Opposition. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

- Pfaff, Steven. 1996. “Collective Identity and Informal Groups in Revolutionary Mobilization: East Germany in 1989.” Social Forces 75 (1): 91–117. doi:10.2307/2580758.

- Pirro, Andrea, Elena Pavan, Adam Fagan, and David Gazsi. 2021. “Close Ever, Distant Never? Integrating Protest Event and Social Network Approaches Into the Transformation of the Hungarian far Right.” Party Politics 27 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1177/1354068819863624.

- Platek, Daniel. 2020. “Przemoc Skrajnej Prawicy w Polsce. Analiza Strategicznego Pola Ruchu Społecznego.” Studia Socjologiczne 4 (239): 123–153. doi:10.24425/sts.2020.135140.

- Platek, Daniel, and Piotr Plucienniczak. 2017. “Mobilizing on the Extreme Right in Poland: Marginalization, Institutionalization, and Radicalization.” In Civil Society Revisited. Lessons from Poland, edited by Kerstin Jacobsson and Elżbieta Korolczuk, 257–286. New York: Berghahn Press.

- Poletta, Francesca, and James Jasper. 2001. “Collective Identity in Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (1): 283–305. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.283.

- Reagans, Ray, and Bill McEvily. 2003. “Network Structure and Knowledge Transfer: The Effects of Cohesion and Range.” Administrative Science Quarterly 48 (2): 240–267. doi:10.2307/3556658.

- Rydgren, Jens. 2007. “The Sociology of the Radical Right.” Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 241–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752.

- Schlozman, Daniel. 2015. When Movements Anchor Parties: Electoral Alignments in American History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sinclair, Phillip. 2011. “The Political Networks of Mexico and Measuring Centralization.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 10: 26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.01.005.

- Skocpol, Theda, and Vanessa Williamson. 2012. The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sniderman, Paul, and Louk Hagendoorn. 2007. When Ways of Life Collide: Multiculturalism and Its Discontents in the Netherlands. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Snow, David. 2006. “Framing Processes, Ideology, and Discursive Fields.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by David Snow and Sarah Soule, 380–413. New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing.

- Stier, Sebastian, Lisa Posch, Arnim Bleier, and Markus Strohmaier. 2017. “When Populists Become Popular: Comparing Facebook Use by the Right-Wing Movement Pegida and German Political Parties.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (9): 1365–1388. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328519.

- Tarrow, Sidney. 1998. Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action, and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tarrow, Sidney. 2005. The New Transnational Contention: Movements, States, and Internationalization. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Dyke, Nella, and Holly McCammon. 2010. Strategic Alliances Coalition Building and Social Movements. Cambridge: Minnesota University Press.

- Wodak, Ruth. 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Appendix

Table A1. Left/liberal pillar (sorted in descending order, political parties marked in bold font).

Table A2. Right pillar (sorted in descending order, political parties are shown in bold font).