ABSTRACT

Viktor Orbán has been a key figure in increasing the role Euroscepticism plays in European integration. By developing a new relational approach to rhetorical political analysis, this article examines how Orbán uses Eurosceptic rhetoric to move the largely pro-EU Hungarian public towards an EU-critical position. By analysing the Hungarian Prime Minister's speeches and interviews, it identifies three strategies of Eurosceptic positioning, political, cultural, and democratic, by which Orbán strategically creates distance between the EU and Hungarian voters regarding the EU's migration policy. Orbán's dynamic positioning expressed through his Eurosceptic rhetoric allows him to be pro- and anti-integrationist simultaneously.

1. Introduction

The progressive narrative of building an “ever closer Union”, over the last decade, has been shaken. Whether we think of the Eurozone and the 2015–2016 migration/refugee crisis, Brexit, the COVID-19 pandemic, or Russia's invasion of Ukraine, countless examples of friction and, sometimes, outright opposition between member states and EU institutions attest to the fact that the future of a political union is far from certain. Even prior to the crisis-ridden 2010s, there were political signs (i.e. the French and Dutch rejection of the EU constitution) that the elite-driven legitimacy of European integration had been put under public pressure (De Vries Citation2018; Hobolt and De Vries Citation2016). As a result, opposition to the EU, often labelled as “Euroscepticism” (Leconte Citation2010; Leruth, Startin, and Usherwood Citation2017; Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2008; Taggart Citation1998), has become embedded (Usherwood and Startin Citation2013) and increasingly mainstream by gaining electoral legitimacy and salience both at European and national levels (Brack and Startin Citation2015). In light of the 2018 European Parliament Elections, Treib (Citation2021) argues that as a result of the increasing centralisation of the last six decades in the EU, Euroscepticism has emerged as a political force of opposition to further integration and it is, likely, here to stay.

Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian Prime Minister (PM), has actively contributed to the mainstreaming of Eurosceptic discourse by being a prominent and vocal critic of the EU and its institutions. The political acts of Orbán and his party Fidesz are, however, more frequently analysed in the populism literature (Batory Citation2016; Csehi Citation2019; Csehi and Zgut Citation2021; Enyedi Citation2016; Hegedüs Citation2019; Jenne, Hawkins, and Silva Citation2021; Visnovitz and Jenne Citation2021) and the literature on democratic backsliding (Bánkuti, Halmai, and Scheppele Citation2012; Bozóki and Hegedűs Citation2018; Dimitrova Citation2018; Greskovits Citation2015; Kelemen Citation2017; Meijers and Van der Veer Citation2019) that partially overlap with Euroscepticism but primarily focus on different political and legal issues.Footnote1 Orbán is less frequently given in-depth analytical space within the literature of Euroscepticism. There are a few individual case studies on Hungarian Euroscepticism (i.e. Batory Citation2002, Citation2008) and regional and continent-wide comparative studies that also include Fidesz (Dúró Citation2017; Kopecký and Mudde Citation2002; Styczyńska Citation2017; Szczerbiak Citation2021; Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2013, Citation2018), but there is no detailed analysis looking at Orbán's Eurosceptic politics.

Orbán's Euroscepticism presents an interesting case because his criticisms aimed at the EU are made despite consistently pro-EU Hungarian public opinion; there is a large distance between the positions of leader and electorate. Subsequently, to successfully legitimise a Eurosceptic discourse in the public domain, Orbán would have to move the Hungarian electorate, or at least his constituency, to a more proximal position to his own but without appearing to jeopardise and reject Hungary's EU membership, which enjoys the overwhelming support of Hungarians, including Fidesz voters (Kolosi and Hudácskó Citation2020). Can the gap between Orbán and the Hungarian electorate be bridged? In other words, can Orbán move his supporters, or indeed a large section of the Hungarian population, towards a more critical stance in relation to the EU, without rejecting Hungary's membership? If he can, how? I argue that his rhetorical practice was the means by which he effected this strategic move. By exploring Orbán's rhetorical interventions during his third term, I answer these questions. Between 2014 and 2018, Orbán successfully monopolised the issue of the 2015–2016 migration crisis domestically and as a result, turned it into his “political jackpot” (Bíró-Nagy Citation2022). An important element of this jackpot was the wider European and EU framework within which the crisis was interpreted, which provides an excellent case study to explore Orbán's increasingly Eurosceptic rhetoric. By deploying a relational approach to rhetorical political analysis (RPA), I investigate how Orbán used Eurosceptic rhetoric to manage the pre-existing distance between the Hungarian government, the Hungarian electorate, and the EU.

First, I address the scholarly literature about party-based Euroscepticism and how the successive Orbán governments, with unconditional backing from Fidesz, can be located within the literature. I also demonstrate how an analysis of Orbán's Eurosceptic rhetoric can enhance our knowledge. Second, I provide an overview of Fidesz's political identity and its relationship to the EU to provide a short historical background to Orbán's Eurosceptic strategies. Third, I explain how the chosen method of a relational approach to RPA can support my analysis, followed by a summary of the case study. Fourth, I systematically analyse the political rhetoric of Orbán during the 2014–2018 governing cycle, first by outlining the national rhetorical situation followed by a special focus on Orbán's rhetorical strategies on the relationship between Hungary and the EU. I find that Orbán used three strategies of distanciation, political, cultural, and democratic, embedded in his Eurosceptic discourse that helped him influence a significant portion of Hungarian voters to oppose the EU's migration policy. The article concludes with important contributions to research on Euroscepticism.

2. Party-based Euroscepticism and Orbán's Eurosceptic rhetoric

The most influential approach (Leconte Citation2010; Leruth, Startin, and Usherwood Citation2017; Vasilopoulou Citation2017) to theorising, defining, and empirically testing party-based Euroscepticism is based on the soft/hard distinction (Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2008, Citation2017). Hard Euroscepticism is understood as “principled opposition to the project of European integration as embodied in the EU based on the ceding or transfer of powers to a supranational institution such as the EU”, while soft Euroscepticism refers to “opposition to the EU's current or future planned trajectory based on the further extension of competencies that the EU was planning to make” without “principled objection to the European integration project of transferring powers to a supranational body such as the EU” (Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2017, 13). In other words, the degree of criticism and opposition levelled against the EU by political parties ranges from advocating for membership withdrawal in hard Euroscepticism, while soft Euroscepticism may be understood in terms of parties who substantially criticise the current or future state of the EU but with an intent to remain within the EU system (Taggart Citation2020). In essence, the former opposes both the idea and practice of European integration representing a “not at all” position, while the latter opposes “only” the practice representing a “not like this” position. While hard Euroscepticism is rare, soft Eurosceptic parties are present in most EU member states (Taggart Citation2020).

Throughout the last two decades, scholars have identified an increasingly Eurosceptic trajectory in Fidesz's attitudes towards the EU. In the early 2000s, Fidesz was simultaneously categorised as soft Eurosceptic (Batory Citation2002) and as Euroenthusiast (Kopecký and Mudde Citation2002), based on different interpretations of the available discursive data. Since then, with the exception of Dúró (Citation2017) who categorise Fidesz as Europragmatist, Fidesz has been referred to as taking a soft, albeit increasingly vocal, Eurosceptic stance (Batory Citation2008, Citation2016; Szczerbiak Citation2021; Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2013).

While scholars tend to agree on Fidesz's Eurosceptic position on the soft/hard taxonomy, I argue that an in-depth study of Orbán's Eurosceptic rhetoric can enhance, and potentially qualify, our knowledge. First, the above-mentioned studies focus on party-positions and as such tend to leave the abundance of rhetorical data in individual politicians’ interventions underexplored. Subsequently, studying Orbán's rhetoric provides an opportunity to analyse the individual arguments and strategies put forward by, undoubtedly, the most salient and powerful political speaker in Hungary (Szilágyi and Bozóki Citation2015). Second, the scholarly judgements on individual party positions on the soft/hard taxonomy are primarily based on discursive party documents, i.e. party manifestos, leader statements, and parliamentary debates (Taggart and Szczerbiak Citation2008, 8). Fidesz, however, has not published either a national election or an EP election manifesto since 2014, which would otherwise have been a major source of data on the party's EU positions. In a hyper-centralised and personalised political party such as Fidesz, where nothing “can happen within the party, in government, or in other segments of the state without Orbán's permission or approval” (Körösényi, Illés, and Gyulai Citation2020, 98), by analysing Orbán's arguments in detail, we not only develop a more accurate view of his ideas and position in relation to the EU, but we can also extrapolate our findings to his entire political party and the government he heads.Footnote2 Finally, Orbán is not simply a prolific speaker – he delivers hundreds of speeches every election cycle –, but many of his speeches are carefully staged major political events with tens of thousands of his supporters attending and showing their loyalty to the party. Such performative elements further elevate the weight and direction of the political agenda that is expressed in his speeches.

3. Fidesz's political identity and relationship to the EUFootnote3

Fidesz spent the 1990s becoming a conservative catch-all party by strategically absorbing competing right-wing parties through integrating their political elites, and constituents of moderate liberal-conservatives, religious voters, the elderly, people with lower levels of education, and rural residents (Fowler Citation2004). In the mid-1990s when the Hungarian Democratic Forum, the first governing party post-regime change, was disintegrating and the nationalist position became up for grabs, Fidesz took the opportunity (Wéber Citation2010). They successfully reconstructed the centre-right around a cohesive political strategy of ethnonationalism and subsequently made that position the fundamental source of governmental authority (Fowler Citation2004). From the early 2000s, under the unquestionable leadership of Orbán (Balázs Citation2018), Fidesz actively pursued a strategy of political polarisation by rhetorically claiming exclusive ownership of the nation (Palonen Citation2018). As a result, the position of cultivating and representing the interests of the ethnic Hungarian nation – a commonly recalled justificatory narrative for the party's relevance (13DEC15) – became the ultimate source of legitimacy for any present and future political action (Egedy Citation2013).

Defining political legitimacy in terms of pursuing the national interest also meant that Fidesz moved towards a conservative interpretation of the EU early on (Navracsics Citation1997). Fidesz (Citation1996) approached European integration not as an end in itself, but a powerful means to pursue national interests. However, the position of pursuing national interests also requires protecting the sovereignty of the nation, which is not fully compatible with the EU's goal of an “ever closer Union”. Fidesz's solution (Citation2002) to this dilemma is that integration does not entail relinquishing Hungary's sovereignty, but that certain elements of it are exercised together with other EU states. In other words, sovereignty can be pooled in certain spheres, but not in others. Integration is supported, argues Orbán, if it contributes to “strengthening of the nations and the enhancement of their economic performance and potential” (29FEB16). This is an economically driven and instrumental view of integration that limits integration to specific spheres. From this position, the continued pooling of national powers to EU institutions, i.e. political integration, cannot be perceived as inevitable progress towards superior supranationalism but as increasing limitations on national sovereignty (03DEC15, 23JUL16). For Orbán, manifestations of political integration, i.e. the idea of “United Nations of Europe”, are “madness” (23OCT17), “utopia” and “suicide” (08NOV14). But opposing political integration does not entail that Fidesz's commitment to the European Project has ever been in doubt (25AUG14, 29MAY15). According to Orbán (29MAY15), the conflictual nature of integration, i.e. the perpetual struggle for pursuing national interests as a member state (08DEC02), should never push Hungary towards considering exiting. Instead, Hungary's interests lie in pushing for an alternative idea of integration in the form of “Europe of nations” (02DEC15, 12SEP16), by which Orbán means reinforcing the bargaining power of individual member states, while reducing the power of supranational institutions (23JUL16). Such ideas of institutional reorganisations, however, do not amount to an anti-EU position. Orbán does not contest the EU per se, he, instead, challenges its liberal and cosmopolitan interpretation (Mos Citation2020; Sadecki Citation2022; Scott Citation2021) and the “supranationalisation” of such an understanding of EU politics because of their capacity to limit national sovereignty.

In sum, Fidesz and Orbán's approach to the EU displays both pro- and anti-integrationist features. But even their anti-integrationist stance must be qualified by Orbán's ideas to imbue the EU with a new conservative interpretation. Nevertheless, Orbán's broader strategy of legitimation through promoting nationalism and sovereignty (and Fidesz as the tribunes of these) puts him and his party in opposition with any form of political integration that poses a threat Hungary's national interests. The EC's proposal of a permanent relocation mechanism (quota) in 2015 (EC Citation2015), which aimed to ease migratory pressures experienced by frontline member states through mandatory distribution, was interpreted by Orbán as a step towards political integration threatening national sovereignty. Orbán's Eurosceptic rhetoric needs to be situated and analysed in this context.

4. Methods and case study

Politics is the field of situations of uncertainty, verisimilitude, and probability (Meyer Citation1996), and as such, political actions and developments have multiple interpretations. To manage the emerging contingency, political actors or speakers use rhetoric to justify their actions and policies and persuade citizens of the validity and legitimacy of their position. Speakers, via rhetoric, construct social identities around given issues and aim to persuade their audience to identify with those positions, which can then pave the way for collective action (Atkins Citation2022). RPA explores this process of legitimation-through-argumentation by attending to the formation, development, propagation, and change of ideas present in political arguments (Atkins and Finlayson Citation2013; Finlayson Citation2007, Citation2012; Martin Citation2013). To explore the speaker's strategies of legitimation, RPA reintroduces the three primary modes of persuasive appeals to political analysis: ethos, logos, and pathos. Appeals to logos offer logical justifications, appeals to ethos rely on the values and character of the speaker, and appeals to pathos play on the emotions of the audience (Finlayson Citation2007). These appeals, however, cannot be analysed independently of their context. RPA emphasises that political arguments and the social identities they aim to create are time- and space-specific (Atkins and Finlayson Citation2013), which means that rhetorical interventions are “situated social practices” (Martin Citation2013, 9) within given sociocultural and political contexts. In other words, to explain the success or failure of political arguments, their immediate rhetorical context or situation (Bitzer Citation1968) also needs to be incorporated into the analysis.

To analyse the outcome of the rhetorical encounter between speaker and audience, I argue, we need to complement RPA's toolkit with a relational understanding of rhetoric. Meyer’s (Citation2017, xiv) approach that sees rhetoric as “the negotiation of the distance between protagonists on a given question” emphasises the same identity-constructing character of rhetoric as Atkins’s (Citation2022) but it does so via the concept of managing distance. In this framework, the social goal of rhetoric is managing the implicit social distance between speaker and audience (their pre-existing social, economic, cultural, and political embeddedness relative to one another) via the treatment of an explicit social or political question (Turnbull Citation2014). In political rhetoric, this explicit question is represented by the topic the speaker brings in front of their audience. In addressing the topic, the implicit social distance is translated into explicit political positions taken up by the interlocutors. This dynamic negotiation of social distance, also called “distanciation” (Price-Thomas and Turnbull Citation2018), can result in three possible outcomes: it is maintained ( = ), decreased to bring interlocutors closer (−), or increased to drive them further apart (+) (Meyer Citation2017; Turnbull Citation2014). It follows from this that distanciation as the fundamental goal of rhetoric not only offers ordinal measures of effects of a more distal or proximal relationship between speaker and audience, but it also broadens our analytical scope beyond that of persuasion.

A relational approach to RPA is ideal to explore Orbán's rhetorical strategies. Before returning to power in 2010, Orbán (17APR09) argued that EU membership would eventually lead to the blurring of the traditional dividing line between domestic and foreign policy and as a result, national and EU politics would become intertwined. For strategies of distanciation, a logical consequence of Orbán's argument is that recalibrating social distance at the EU-level would simultaneously recalibrate them at the national level. In other words, by increasing the distance via Eurosceptic rhetoric (logos) between the Hungarian government, and Orbán per se, as the representatives of Hungarian national interests and values (ethos), and external players, such as the European Commission (EC), the European Parliament (EP), and heads of member states, Orbán would simultaneously create a proximal relationship with the Hungarian electorate (pathos). In other words, Orbán would construct a match “Hungarians with Orbán contra EU”, where he would deploy Eurosceptic rhetoric to manage the distance between the parties involved.

The specific case study under investigation is the 2015–2016 migration crisis; primarily its broader implications for Hungarian-EU relations, as they were interpreted by the Hungarian PM. The migration crisis happened during the third term of Viktor Orbán (2014–2018), my analysis, therefore, covers Orbán's rhetorical interventions from the entire four-year governing cycle. By focusing on the European and EU framework of Orbán's discourse on the migration crisis, I provide an in-depth analysis of the evolving Eurosceptic politics and rhetoric of the Hungarian government. My paper extends a recent and novel line of enquiry that explores Orbán's rhetorical interventions in relation to questions, such as the rule of law (Mos Citation2020), LGBQI and gender equality (Mos Citation2022), and redefining Europe (Sadecki Citation2022).

I compiled a corpus of Orbán's speeches, press conferences, and interviews. First, I collected 39 texts that discussed matters related to European integration, at both domestic and international platforms (see table below for an overview). The majority of the texts are from the period of 2014–2018, spanning the entire four years of the third Orbán government, but I also relied on speeches from earlier periods to provide necessary historical context to Orbán and Fidesz's political identity. I used the original Hungarian-language version of all speeches for data collection. When I used quotations in the article, I either relied on the English-language version (if available) of the speeches after making sure that each translation provides an accurate representation of the original text, or, as in the case of earlier speeches, I translated the quotes myself. Both Hungarian- and English-language versions were retrieved from the official website of the Hungarian government, https://2015–2019.kormany.hu/hu and https://2015–2019.kormany.hu/en, respectively. When quoted, the texts are referenced in brackets by the day, month, and year (e.g. 08DEC02).

Rhetorical political analysis should focus on three distinct moments of speech interventions: (1) the rhetorical context, (2) the rhetorical argument, and (3) the rhetorical effects (Martin Citation2013, 100). For (1), I used secondary data to establish the political context faced by Orbán and Fidesz immediately before the onset of the migration crisis. I also complemented this mapping exercise by providing a concise qualitative analysis of Orbán's conflictual relationship with the EU and his views on migration. For (2), I first specified a corpus of texts discussing the migration crisis, as a particular issue. I then focused on the texts’ more universal relevance (Finlayson Citation2007, 555) to the question of EU-Hungary relations, identifying references to Europe and the EU. I carried out a close reading of all speeches and interviews with the objective of uncovering patterns of rhetorical management of social distance, with a particular focus on Orbán's “composite, multi-layered performance embodied in communication” (Martin Citation2013, 94), including the type of ethos, logos, and pathos mobilised. By focusing on the character and judgement of the speaker (ethos), the logic or reason (logos) they mobilise, and the emotions and feelings of the audience (pathos) to which the speaker aims to appeal, I explore how these individual appeals were deployed by Orbán to construct distance between the EU and the Hungarian public. Finally, for (3), I use findings by Hungarian public opinion and EU experts and polling companies to explore the relationship between the changes in public opinion and Orbán's rhetorical interventions ().

Table 1. Overview of speeches of Viktor Orbán.

5. The rhetorical situation and Orbán's Eurosceptic rhetoric of distanciation

To fully appreciate the rhetorical strategies of distanciation and the type of ethos, logos, and pathos involved in Orbán's Eurosceptic rhetoric in relation to the refugee/migrant crisis, a brief elaboration on the broader rhetorical situation of the national context of the crisis is needed.

5.1. Domestic rhetorical situation

Returning to power in 2010 after 8 years in opposition, Orbán radically changed the underlying rhetoric of Hungarian EU policy in comparison to previous governments. In Orbán's understanding the foreign policy tradition of the socialist-liberal governments had been “euroservile” (Fidesz Citation2002; Orbán [08DEC02]) rooted in “inferiority complex” (18MAY03) and “conformism” (07SEP15). If Fidesz, which has built its political credo on standing up for the interests of the Hungarian nation under any circumstance (03JUL11), wanted to increase the distance between the EU and the Hungarian electorate, continuing the policy tradition of previous governments would not have been a useful political strategy. Also, in a political climate where power-projecting leader-centred politics still enjoyed significant electoral purchase (Valuch Citation2015), not standing up to the EU could potentially ignite feelings of contempt (pathos) from parts of the electorate. Orbán succinctly reflected the authoritarian undertone of his government's EU policy: “those who do not face up to arguments and do not stand up for themselves are pushovers and losers, and are not qualified to [lead] their own nations” (23MAY14). Consequently, to increase distance between the Hungarian government and EU institutions, conflicts with Brussels were necessary (23MAY14). Pre-2014, such conflicts were embedded in an economic and constitutional “freedom fight” rhetoric against the IMF and the EU, arguing that Hungary “will not be a colony” (15MAR12).

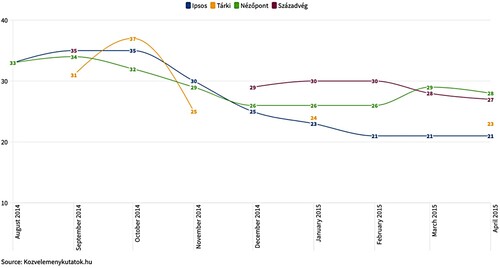

After a triple victory of general, EP, and local elections in 2014, Fidesz, fuelled by a sense of electoral justification, opted for continuing their freedom-fight rhetoric, but a series of domestic issues started to erode their voter share. As a result of the government's proposal to levy a fee on internet data transferred, the so-called “internet tax”; the US government's visa ban on Hungarian tax officials; the open-air dispute between Orbán and Fidesz's former treasurer and head of the country's most powerful business lobby, Fidesz lost multiple by-elections in a row. Having lost yet another one in early 2015, Fidesz also lost their supermajority in the Parliament and with that the ability to enact constitutional change. By initially projecting an ethos of confidence that such issues did not deserve attention and attempting to divert the focus of the public to more positive developments, like the economy (23DEC14), Orbán and Fidesz, inadvertently, increased their distance (+) from multiple segments of the electorate. Fidesz's political problems were further exacerbated by the increasing popularity of far-right Jobbik, partly due to their recent move to rhetorically rebrand themselves as a “people's party” in order to improve their public perception and future electability (Bíró-Nagy and Boros Citation2016). The popularity of Fidesz was eroding quickly, and by January 2015, the polling company Ipsos found that Fidesz had lost almost 1 million voters compared with polling data from September 2014 (HVG Citation2015). Orbán and Fidesz were struggling domestically, and they urgently needed a strategy that could help them re-establish their credibility and electoral support ().

Figure 1. Changes in Fidesz's public support, September 2014 to April 2015 (percentage) based on the data of four Hungarian polling companies.

The question of migration, an issue traditionally owned by Jobbik in Hungarian politics pre-2015 (Bíró-Nagy Citation2022), is not a new theme in Orbán's rhetoric. While the issue had not been politicised anywhere near to the degree as it was between 2015 and 2018, migration has been, from early on, situated within the triangle of demographic decline, (im)migration, and family policy in Orbán's rhetoric. The future of any ethnic population is dependent on their demographic capacity, which, in Orbán's and Fidesz's ethnonationalist view, can and should only be sustained and increased via pro-natalist family policies. Orbán (30MAR07, 25SEP15, 25MAY17) explicitly argued that immigration cannot be the solution to demographic decline either at the national or at the EU level. The timeliness of any political position is crucial in its electoral success, and for Orbán's pro-natalist and anti-immigration position, with the onset of the migration crisis, an opportunity opened at the beginning in 2015. However, the circumstances that open moments of opportunity, or exigence (Bitzer Citation1968), need to be matched by appropriate interventions. Developing and enacting the right framing, or the “appropriateness of the discourse to the particular circumstances of the time, place, speaker, and audience involved” (Kinneavy Citation1986, 84), was the political undertaking waiting for Orbán. By appropriating the question of migration and embedding it in Eurosceptic rhetoric, Orbán chose a political strategy popular among many populist radical right parties (Pirro, Taggart, and van Kessel Citation2018). This political strategy, for Orbán and Fidesz, had the potential to not only instil distance between Hungary and the EU but also squeeze out the potential threat of Jobbik and maintain their monopoly over the ethnonationalist political space.

5.2. Refugee or migration crisis? Laying the ground for distanciation

In this section, I demonstrate how Orbán politicised the issue of migration embedded in his Eurosceptic discourse. Orbán's aim was to counter the moral framing of the debate and instead focus on the political ramifications of the Commission's relocation mechanism. This allowed him to lay the ground for instilling increased distance (+) between the EU and Hungarians.

The central problem of the crisis focused on who should bear the monetary, social, and political responsibility for migrants and refugees entering the EU and how they should be distributed among member states (Greenhill Citation2016). From the onset of the crisis, there were two identifiable approaches to these problems. The supranational one was articulated by EC President Jean-Claude Juncker (EC Citation2015), “This is … a matter of humanity and of human dignity … a matter of historical fairness”. He framed the problem as a moral issue that could only be solved by supranational solutions, “We need more Europe in our asylum policy. We need more Union in our refugee policy”. The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel (Citation2015), also reinforced Juncker's moral framing by arguing for “fairness and solidarity in sharing the burdens” between member states, while also adding that member states have “to deal responsibly with Europe's gravitational pull … to take greater care of those who are in need”. From Merkel's viewpoint, delivering on Europe's moral duty must be achieved through the supranational solution of “more Europe”. In contrast, “the temptation to fall back on national government action”, such as the Hungarian government's decision to erect a fence at the Southern border of country in 2015, would mean “retreating from the world and shutting ourselves off … abandoning our values … losing our identity”.

By presenting the problem of responsibility and its distribution as a moral issue of fairness and solidarity (ethos) with refugees, migrants, and member states, Juncker and Merkel aimed to ignite empathy and compassion (pathos) based on geographical proximity and the idea of the EU as a community of shared values. Emphasising the moral frame was a conduit to depoliticising the issue of responsibility because it called on politicians’ and citizens’ moral conscience to act immediately as required by their shared European values and identity. Logically, if such European values and identity were indeed shared, then adhering to them and carrying them out was a not a matter of choice or deliberation, but of duty. The most effective way to live up to such duty on a European scale is via the technocratic, rule-based model of supranational decision-making, epitomised by the Commission's permanent relocation mechanism.

From an opposite viewpoint, the migration crisis appeared as a political issue touching on the core competences of member states, such as statehood, borders, national community, and sovereignty. To keep these powers within national jurisdiction, altering the pre-existing distance between member states and the EU seemed necessary. This second sovereigntist or identitarian approach was first represented by Orbán and his government (28FEB16, 23JUN17) and later also adopted by Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Poland (Hokovský Citation2016). For Orbán, accepting Juncker and Merkel's moral framing could not deliver the political space needed to re-establish Fidesz's national legitimacy because the inherent difficulty of challenging moral positions would place him in a defensive position (“We do not have hearts of stone either” [28FEB16]). An alternative route was to politicise the issue via a Eurosceptic rhetorical (logos) framework. Consequently, Orbán, via appealing to passions, proceeded to instil as much distance as possible by calling the Commission's proposal “nothing short of absurd, bordering on the insane” (19MAY15). Delivering his explicit and damaging judgment (ethos) in Strasbourg by playing on the personal proximity to the addressees, the Commission surely received Orbán's distanciation (+) as an insult (pathos). From a rhetorical viewpoint, Orbán's outright rejection of the quota (+) did not only put the mechanism into question, but it also signalled the personal rejection (pathos) of its most important supporters (Juncker and Merkel).

However, to successfully undermine the moral framing of Juncker and Merkel, at least in Hungary, required more than insults and rejection; it needed a counter-narrative (logos). Early in the crisis, Orbán used paradiastole, a rhetorical technique of evaluative redescription, to shift the debate from an issue of refugees to a question of EU migration. He did this for two reasons. First, he aimed to counter the positive undertone of Juncker and Merkel's moral framing by attaching an alternative meaning to the phenomenon with a negative evaluative force (+). Orbán's redescription purposefully appealed to the anti-immigrant sentiments prevalent in Hungarian society, i.e. intolerance and prejudice towards “indigenous others” and foreigners (Valuch Citation2015), that are primarily rooted in economic and cultural fears (Barna and Koltai Citation2019; Sík, Simonovits, and Szeitl Citation2016). To tap into these dormant but historically embodied sociocultural sentiments (pathos), Orbán not only imbued the term “economic migration” (02FEB15, 19MAY15) with multiple layers of economic and cultural risk (25JUL15, 05SEP15), he also attributed blame (+) for the current situation to a failed EU leadership (23JUL16). Second, the intended negative connotation of the terms “migrant” (migráns) or “immigrant” (bevándorló) (Bocskor Citation2018) allowed Orbán to situate the issue within Fidesz's ideological position on (im)migration, demographic decline, family policy (“we do not want an EU regulation which would force us, also, to solve our country's [demographic] problems through immigration”, 25SEP15) and thus immediately elevate the issue to a matter of sovereignty and national interest in opposition to Brussels (15FEB16). In sum, marrying the question of migration with Euroscepticism laid down the groundwork for increasing the political distance between Hungarians and the EU.

5.3. Political distanciation: “National Consultation on Illegal Immigration and Terrorism”

To reinforce the discursive link between EU migration, economic and cultural fears, and the EU's responsibility among Hungarians, Orbán had to manufacture public consensus around the issue (“[immigration] can only be tackled if we identify points on which we can all agree as a community”, 25JUL15). One of the primary tools for this political move was a series of national consultations. The political idea behind national consultations is to create a link between “the people” and “politics” (16FEB05) by eliciting answers from citizens via a series of (directed) questions that then become a pretext for democratic politics and the subsequent justification for future actions of government. The National Consultation on Illegal Immigration and Terrorism of 2015 (Prime Minister’s Office Citation2015), the first of three consultations, not only laid the Hungarian government's groundwork to securitise the issue of migration for the next three years (Szalai and Gőbl Citation2015), but it was also the first step towards performing the issue. By camouflaging the consultation as a genuine deliberation between government and the Hungarian people, Orbán and Fidesz performed a politics of action (ethos), projecting determination and competence, which was then contrasted (+) with European politics that was “suffering from a dangerous paralysis, of procrastination, of complete ineptitude” (13DEC15). Not leaving the outcome of the consultation to chance, the securitised Eurosceptic message was reiterated in a letter attached to every consultation form with a photo and signature of Orbán. In that he emphasised the threat (pathos) to the economic wellbeing of Hungarians, while also stressed that Hungary had to act on its own because “Brussels had failed” (+) to manage migration (25APR15). Such strong priming was no doubt crucial in delivering results.

Though the response rate to the consultation was relatively low (1,312,000 peopleFootnote4 out of approximately 8 million responded to the government's questionnaire), there was a clear tendency to identify with the government's position (-) to pursue active measures to protect the Hungarian nation. There was an almost unanimous agreement (90%+) with most (directed) questions inciting general fear (pathos) of terrorism around Europe and in Hungary, whilst also linking terrorism to the failed immigration policy of Brussels. A huge majority of the respondents also agreed to stricter governmental action against immigrants in general and illegal economic immigrants in particular, backing a stronger military presence at the Southern border. The public support for deployment of the armed forces was a symbolic act of revealing and reaffirming their difference from outsiders ( = ) and was generated by what Aristotle calls the regime-preserving character of fear in politics (Pfau Citation2007). Fear is dependent on the perception of distance; the geographically distal source of fear that is made proximal through rhetoric creates a sense of urgency for political action (“we are inundated with countless immigrants: there is an invasion” [05SEP15]). The subsequent existential fear felt by citizens tends to lead to a rally-around-the-flag effect (-) of increased public support for leaders who project determination (Schlipphak and Treib Citation2017). However, as Aristotle (Pfau Citation2007, 223) explains, “no one deliberates about hopeless things”, thus existential dread cannot be overwhelming to the point of resignation, which would undermine faith in action and leadership. Consequently, demonstrating political strength (ethos) is needed to restore hope: “I can assure you that we shall … protect Hungary … and the Hungarian people” (21SEP15).

With the first consultation, Orbán created a two-pronged political device to facilitate the entrenching of his Eurosceptic message. First, he could point at the overwhelmingly favourable results and claim to have the democratic mandate of his political leadership and his political position reaffirmed (-). Second, he created a risky dilemma for EU institutions. The Consultation not only openly defied an emerging EU policy, but the accusatory language and directed nature of its questions could not have been ignored by the EP and the Commission. However, any line of criticism from these institutions would appear as questioning the sovereign decision of Hungarians who filled out the questionnaire. Indeed, when the EP (Citation2015) publicly denounced the Hungarian consultation stressing that “the content and language … are … misleading, biased and unbalanced”, and later that year the Commission initiated infringement proceedings against Hungary regarding its asylum legislation, they inadvertently reinforced the ethos of the Hungarian government and alienated the Hungarian public (+). The EU institutions could easily be accused of overstepping their allocated competences in an attempt to override Hungary's right to self-determination (pathos). The accusation (ethos) was even more damning in the case of the Commission because it summoned the EU-wide topos of democratic deficit (“This is why, despite my veto of the … quota system in the Council … the Commission manipulated the system … and so my single veto, Hungary's veto, didn't count. We were cheated and deceived” [22JUL17]). Orbán invoked pathos of unfairness, injustice, and indignation towards the EU institutions (+) feeding into the public view that Hungarian interests are not fully represented by the EU (European Commission Citation2016). Consequently, the EU institutions contributed to legitimising a more proximal political bond between Orbán and his electorate.

5.4. Playing on cultural and democratic distance

In this section I demonstrate how Orbán's political Euroscepticism was expanding into a civilisational narrative, which allowed him to emphasise the cultural and democratic differences he alleged were emerging between Western and Central Europe (Sadecki Citation2022). In other words, beyond political distanciation focusing on the quota mechanism, Orbán also played on cultural and democratic distanciation.

By 2016, when the government's actions successfully curbed immigration, Orbán's rhetoric expanded the frame of the debate. While his rhetoric shifted to appeals of societal faith (pathos) in the government for having found and enacted a solution to the immediate problem of illegal immigration (ethos), he also emphasised that the crisis was not over yet. In Orbán's explanation the migration crisis revealed that the Hungarian nation had to face up to the fact that beyond the immediate risks of migration, there was a more fundamental and long-term threat: the post-Christian and post-national politics (12NOV17) of the West in general and of Brussels in particular (“our problem is not in Mecca, but in Brussels. The obstacle for us is not Islam, but the bureaucrats in Brussels” [23JUL17]). As a result, Orbán elevated his Eurosceptic narrative to a civilisational plane (“Europe and Hungary stand at the epicentre of a civilisational struggle” [15MAR18]), where the cultural distance between Central and Western Europe (12FEB18), unionists and sovereigntists (10FEB17), globalists and nationalists (09NOV17), pro- and anti-immigration nations (21OCT16) could be magnified.

A highly symbolic and non-discursive element of Orbán's civilisational narrative was the government erected fence along the Southern border of Hungary. First and foremost, it promised security (pathos), showcased governmental power (ethos), and revealed and increased (+) the distance between Christian Hungary and the culture of “immigrant invasion” (13DEC15, 23OCT17). In other words, it had a domestic purpose. But it also carried the potential for forging a European cultural and democratic divide because it exposed the large distance between a nationalistic and Christian understanding of Europe emphasising the sovereignty of nations, represented by Hungary and the V4Footnote5, and that of Willkommenskultur's elitist and universalist vision of a supranational Europe (28FEB16). While politicians, such as Merkel (Eder and De La Baume Citation2015) and Juncker (Barigazzi and Cienski Citation2015), criticised the fence on pragmatic grounds of short-sightedness arguing that it could not stop migration, Orbán justified his position on Hungary's border-protecting obligations (ethos) arising from the Schengen Protocol (11JUL16). As a result, he could present himself as a true European who respects and upholds his country's contractual duty to protect the economic wellbeing and security of European citizens (12SEP15) in contrast to those who, according to him (27JUN17), risk European integration by trying to enforce the quota mechanism and thus to take away the sovereign right of Europe's nations to decide their future. The Eurosceptic Orbán did not simply transform himself into the democratic saviour of Europe rhetorically, he also redefined the meaning of Europe by stating that “we [those in Central Europe] are the future of Europe” (22JUL17). Using the simple metonymy of “we” allowed Orbán to identify (−) “Europe” with the anti-immigration rhetoric and policies popular in Hungary and simultaneously reject (+) a more liberal vision present in the West. In other words, Orbán's rhetoric also enabled him to project an ethnonationalist counter-narrative to “Europe”. With 71% of Hungarians approving of Orbán's handling of the migration crisis in contrast to 24% expressing the same view of the EU (Pew Citation2016a), it was evident that Orbán's Eurosceptic distanciation was working.

To reaffirm his national democratic credentials domestically and turn them into political capital at the EU-level, Orbán held a referendum in October 2016 on the (directed) question “Do you want the European Union to be able to mandate the obligatory resettlement of non-Hungarian citizens into Hungary even without the approval of the National Assembly?”. The argument (logos) for the referendum was based on the ethos of democracy and the right to self-determination (28FEB2016). The invocation of democracy and plebiscitary politics was not simply the reaffirmation of the political contract between Orbán (ethos) and the Hungarian public (pathos) ( = ), it also represented outright defiance (+) of the technocratic nature of decision-making at the European level. When polling numbers around Europe showed that there was a growing dissatisfaction towards the EU's approach to handling the migration crisis (Pew Citation2016b), by holding a referendum on this issue, Orbán constructed yet another problem for the EU political elite, similarly to his first national consultation. If the referendum delivered favourable results for Orbán's rhetoric and policies, he could point not simply to his democratic mandate (ethos) at the European Council but also question the democratic legitimacy (pathos) of any other European politician who had chosen not to consult their electorate, as indeed Orbán did with Merkel when he said at a European Council meeting not soon after the Hungarian referendum, “we don't know what the Germans want. What we do know is what the German Chancellor wants” (16DEC16). And although the referendum was invalid because it did not reach the required 50% threshold, the 3.3 million voters of whom 98% voted against the quota mechanism far exceeded the core base of 1.6–1.9 million Fidesz voters. By identifying (-) with the government's rhetorical answer that the quota mechanism should be rejected, 3.3 million Hungarian voters legitimised and reaffirmed their opposition (+) to the EU's policy.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Orbán's strategy to focus on the refugee/migration crisis embedded in his Eurosceptic rhetoric dominated the Hungarian political field from 2015 to 2018 (Bíró-Nagy Citation2022). By monopolising the issue of migration in Hungary, often by expropriating proposals of Jobbik, Fidesz outmanoeuvred the far-right party on its own political territory, while the other opposition parties failed to counter Fidesz's narrative (Bíró-Nagy Citation2022). Although, in any given political field there are several available and acceptable discursive positions that are defined by contextual social norms, the governing party's narrative of economic and cultural threat and the sovereign right of the nation to decide about its own fate rhetorically reconstructed the domestic field so that only one position remained acceptable: Fidesz's own (“there are two political trends in Hungary: one which seeks to protect Hungary and the Hungarian people and one which for some reason works to oppose all this” [21SEP15]). The opposition parties were therefore left to either accept Fidesz's narrative and risk fuelling Fidesz's agenda further or oppose it and made to face governmental accusations of failing to act in the national interest. While Jobbik chose the first option, the leftist-liberal opposition chose the second by adopting a desecuritising frame which rejected any security implications migration might have (Szalai and Gőbl Citation2015). Neither option was electorally favourable.

From September 2015 onwards, the distance between Orbán and the Hungarian public started to decrease. Fidesz's electoral support was gradually increasing, and by 2016 they were already ahead by 15 points (Závecz Citation2016). Also, while in September 2015, the Commission's quota mechanism was supported by 47% of the population, which was a more favourable position than that of the Orbán government, by spring 2016, 80% of the population rejected the mechanism (Juhász and Molnár Citation2016). In line with this finding, Bíró-Nagy and Laki (Citation2019) evince that the most invoked negative associations among Hungarians regarding the EU were immigration and losing national sovereignty justified by their fear that the EU wanted to force Hungary to accept a large number of migrants. The Orbánian narrative had clearly reached its audience: 84% of Fidesz voters identified with it, while 54% of voters of opposition parties also agreed with it, accepting and legitimising the culpability of the EU. In other words, a large section of the Hungarian population moved closer to Orbán's critical stance in relation to the EU but without the PM ever arguing for leaving the EU. Moreover, Orbán and Fidesz extended their Eurosceptic narrative of the migration crisis up until the elections of 2018 by using variations (i.e. “Let's stop Brussels” and “STOP Soros” national consultations and billboard campaigns) of the rhetorical strategies described above and as a result, they secured their third electoral win with a supermajority (Bíró-Nagy Citation2022).

To bridge the gap between a pro-EU Hungarian public and his own EU-critical stance, Orbán focused on the refugee/migration crisis embedded in Eurosceptic rhetorical strategies of distanciation, in which the Eurosceptic message was a measure of distance between Orbán and the Hungarian public on the one hand, and EU institutions and political leaders on the other. Orbán introduced three forms of distance: political, cultural, and democratic. By redescribing the political debate around the refugee crisis into one around economic migration emphasising the EU's responsibility in it, Orbán first established and increased political distance between Juncker and Merkel's moral interpretation of the crisis and their supranational solution to it and his sovereigntist position that outrightly rejected both the framing and the solution. Second, to push Hungarians towards a more critical stance towards the EU, Orbán used the tool of national consultations. While only over a million Hungarians filled out the first consultation, it provided a democratic guise for Orbán's Euroscepticism, and its language also set a political dilemma for EU institutions that they could not ignore. Thanks to the criticisms levelled against the Hungarian government by EU institutions, the political distance between EU and Hungary was increased. Third, Orbán intensified his Eurosceptic rhetoric by elevating it to a civilisational plane, where he could emphasise the (allegedly emerging) cultural and democratic distance between Western and Central Europe. By erecting a fence at the Southern border and justifying it with reference to the well-being and security of European nations, Orbán transformed his Eurosceptic image into that of a “true European” who represents and protects the “real” culture of Europe. Finally, to emphasise his democratic credentials Orbán also held a referendum on the quota mechanism. Although, legally, the referendum was not successful, the rejection of the quota mechanism by 3.3 million Hungarians demonstrated the political success of performing Eurosceptic politics in the name of democracy. Playing on political, cultural, and democratic distance contributed to influencing a significant portion of Hungarian voters to oppose the EU's migration policy.

Using previous conceptualisations of Fidesz's Euroscepticism in the literature, it can be inferred that Orbán, and thus Fidesz, represent soft Euroscepticism because Orbán is explicitly against leaving the EU. However, I would argue that the soft/hard heuristic cannot fully capture Orbán's position and dynamic positioning. First, he wants to stop transferring certain powers to EU institutions, which is clearly embodied in his ardent and principled opposition to the quota mechanism in particular and the EU's migration policy in general. He also wants to revoke certain powers both from the Commission and the European Parliament to reinforce intergovernmental decision-making. Second, the political, cultural, and democratic arguments he deployed during the migration crisis also point towards a desire to revisit the EU's political and cultural assumptions. Orbán's Europe is a culturally homogeneous, white, Christian Europe with advanced economic but limited political integration. In other words, Orbán takes a “not at all” or hard Eurosceptic position on political integration but remains economically pro-integrationist. The soft/hard heuristic can sometimes overlook such nuances of political positioning. But if we complement it by utilising the abundance of discursive data at our disposal using rhetorical political analysis, we can further enhance our knowledge of Eurosceptic politics.

A relational approach to RPA opens several potential avenues for further research. First, since no political party is uniform, within Fidesz there certainly are dissenting voices (i.e. Tibor Navracsics or János Martonyi) who would question the desirability of increasing distance between the EU and Hungary. Future research should therefore specifically focus on more pro-EU politicians in Fidesz (and KDNP) to explore how they attempt, if at all, to soften or counter the distal relationship constructed by Orbán. Moreover, to gain insight into the wider discursive construction of the migration crisis in the national and supranational political field, investigating the rhetorical strategies of Hungarian opposition parties as well as EU institutions and their interaction with the Orbánian narrative is needed. Finally, since rhetoric is “a political practice that continuously remakes the world anew” (Price-Thomas and Turnbull Citation2018, 212), exploring Orbán's rhetorical interventions regarding Europe and the EU through multiple election cycles would allow us to identify change and stability in his strategic manoeuvring and geopolitical imaginary, especially in relation to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Such a diachronic study would also allow to see whether Orbán's Eurosceptic rhetoric is indeed a matter of degree, i.e. soft/hard, or whether what we are seeing is a qualitatively different kind of rhetoric, a counter-narrative perhaps (McMahon and Kaiser Citation2022) that challenges the dominant European narrative.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the reviewers for their excellent comments and insightful questions, which helped me refine and sharpen the core argument of my paper. I would also like to express my gratitude to my PhD research supervisors for their perceptive comments and generous support, and the intellectually stimulating environment they provide during our discussions. Without them, this paper would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gergely Agoston

Gergely Agoston is a Doctoral Researcher at the Department of Politics, School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester.

Notes

1 Csehi and Zgut (Citation2021) do explore Eurosceptic topoi in Orbán's rhetoric as part of their comparative analysis of Eurosceptic populist narratives.

2 Since 2010, Hungary has been governed by Fidesz alongside their satellite party, the Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP). Also, Orbán's tight control over Fidesz does not mean that there are no internal debates or dissenting voices within the party, including both more pro- (i.e. János Martonyi or Tibor Navracsics) and anti-EU voices (i.e. László Kövér). It is also true, however, that more pro-EU politicians have been gradually side-lined by Orbán over the last decade.

3 It is important to reiterate the point from the previous section that Fidesz, as a political party, is a collective political actor that includes and channels various intra-party interests and positions. However, due to Orbán's indisputable legitimacy within the party, Fidesz's emerging EU position is ultimately defined by the Hungarian PM.

4 Data provided by the Government Spokesperson (available at: https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/hu/a-kormanyszovivo/hirek/a-tobbseg-egyetertett-az-illegalis-bevandorlassal-kapcsolatos-kerdesekben)

5 The V4 refers to the Visegrad Group, including Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary, which is an informal regional initiative to facilitate cooperation and the development of common position on economic, cultural, and political matters related to Central Europe and the EU.

References

- Atkins, J. 2022. “Rhetoric and Audience Reception: An Analysis of Theresa May’s Vision of Britain and Britishness after Brexit.” Politics 42 (2): 216–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395721991411

- Atkins, J., and A. Finlayson. 2013. “‘ … A 40-year-old Black Man Made the Point to Me’: Everyday Knowledge and the Performance of Leadership in Contemporary British Politics.” Political Studies 61 (1): 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00953.x

- Balázs, Z. 2018. “Mi a FIDESZ?” In Várakozások és valóságok: Parlamenti választás 2018, edited by Balázs Böcskei and Andrea Szabó, 127–145. Budapest: MTA TK PTI.

- Barigazzi, J., and J. Cienski. 2015. “Orbán and Juncker to Face off on Migration.” Politico, September 2. https://www.politico.eu/article/orban-crash-juncker-party-asylum-council-september-migration/.

- Barna, I., and J. Koltai. 2019. “Attitude Changes towards Immigrants in the Turbulent Years of the ‘Migrant Crisis’ and Anti-Immigrant Campaign in Hungary.” Intersections: East European Journal of Society and Politics 5 (1): 48–70.

- Batory, A. 2002. “Attitudes to Europe: Ideology, Strategy and the Issue of European Union Membership in Hungarian Party Politics.” Party Politics 8 (5): 525–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068802008005002

- Batory, A. 2008. “Euroscepticism in the Hungarian Party System: Voices from the Wilderness.” In The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism Volume 1: Case Studies and Country Surveys, edited by Aleks Szczerbiak and Paul Taggart, 237–276. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Batory, A. 2016. “Populists in Government? Hungary's ‘System of National Cooperation’.” Democratization 23 (2): 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1076214

- Bánkuti, M., G. Halmai, and K. L. Scheppele. 2012. “Hungary’s Illiberal Turn: Disabling the Constitution.” Journal of Democracy 23 (3): 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2012.0054

- Bitzer, L. F. 1968. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 1 (1): 1–14.

- Bíró-Nagy, A. 2022. “Orbán’s Political Jackpot: Migration and the Hungarian Electorate.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (2): 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853905

- Bíró-Nagy, A., and T. Boros. 2016. “Jobbik Going Mainstream. Strategy Shift of the Far-Right in Hungary.” In The Extreme Right in Europe, edited by Jerome Jamin, 242–262. Brussels: Bruylant.

- Bíró-Nagy, A., and G. Laki. 2019. “15 Év után: Az Európai Unió és a magyar társadalom.” Friedrich Ebert Foundation and Policy Solutions. https://www.policysolutions.hu/hu/hirek/486/15evutan_kiadvany.

- Bocskor, Á. 2018. “Anti-Immigration Discourses in Hungary during the ‘Crisis’ Year: The Orbán Government’s ‘National Consultation’ Campaign of 2015.” Sociology 52 (3): 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518762081

- Bozóki, A., and D. Hegedűs. 2018. “An Externally Constrained Hybrid Regime: Hungary in the European Union.” Democratization 25 (7): 1173–1189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1455664

- Brack, N., and N. Startin. 2015. “Introduction: Euroscepticism, from the Margins to the Mainstream.” International Political Science Review 36 (3): 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512115577231

- Csehi, R. 2019. “Neither Episodic, nor Destined to Failure? The Endurance of Hungarian Populism after 2010.” Democratization 26 (6): 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1590814

- Csehi, R., and E. Zgut. 2021. “‘We Won’t Let Brussels Dictate Us’: Eurosceptic Populism in Hungary and Poland.” European Politics and Society 22 (1): 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2020.1717064

- De Vries, C. E. 2018. Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dimitrova, A. L. 2018. “The Uncertain Road to Sustainable Democracy: Elite Coalitions, Citizen Protests and the Prospects of Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe.” East European Politics 34 (3): 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1491840

- Dúró, J. 2017. Ellenzők, kritikusok, kétkedők. Budapest: Századvég Kiadó.

- Eder, F., and M. De La Baume. 2015. “Merkel Slams Eastern Europeans on Migration.” Politico, October 7. https://www.politico.eu/article/merkel-eu-needs-to-consider-treaty-change/.

- Egedy, G. 2013. “Conservatism and Nation Models in Hungary.” Hungarian Review 3: 66–75.

- Enyedi, Z. 2016. “Paternalist Populism and Illiberal Elitism in Central Europe.” Journal of Political Ideologies 21 (1): 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2016.1105402

- European Commission. 2015. “Speech by President Jean-Claude Juncker ‘State of the Union 2015.’ Strasbourg, September 9. https://commission.europa.eu/publications/state-union-2015-european-commission-president-jean-claude-juncker_en.

- European Commission. 2016. “Standard Eurobarometer 86 – Autumn 2016.” National Reports: Hungary. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2137.

- European Parliament. 2015. “European Parliament Resolution on the Situation in Hungary. 2015/2700(RSP).” Strasbourg, June 10. https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/popups/ficheprocedure.do?lang=en&reference=2015/2700(RSP).

- Fidesz. 1996. A polgári Magyarországért. Budapest: Fidesz Központi Hivatal.

- Fidesz. 2002. Európa a jövőnk, Magyarország a hazánk. Vitairat az európai újraegyesítésről. Budapest: Fidesz Központi Hivatal.

- Finlayson, A. 2007. “From Beliefs to Arguments: Interpretive Methodology and Rhetorical Political Analysis.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 9 (4): 545–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2007.00269.x

- Finlayson, A. 2012. “Rhetoric and the Political Theory of Ideologies.” Political Studies 60 (4): 751–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00948.x

- Fowler, B. 2004. “Concentrated Orange: Fidesz and the Remaking of the Hungarian Centre-Right, 1994–2002.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 20 (3): 80–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/1352327042000260814

- Greenhill, K. M. 2016. “Open Arms Behind Barred Doors: Fear, Hypocrisy and Policy Schizophrenia in the European Migration Crisis.” European Law Journal 22 (3): 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12179

- Greskovits, B. 2015. “The Hollowing and Backsliding of Democracy in East Central Europe.” Global Policy 6 (S1): 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12225

- Hegedüs, D. 2019. “Rethinking the Incumbency Effect: Radicalization of Governing Populist Parties in East-Central-Europe. A Case Study of Hungary.” European Politics and Society 20 (4): 406–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2019.1569338

- Hobolt, S. B., and C. E. De Vries. 2016. “Public Support for European Integration.” Annual Review of Political Science 19 (1): 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Hokovský, R. 2016. “How migrants brought Central Europe together”, Politico, February 7. https://www.politico.eu/article/how-migrants-brought-central-europe-together-visegrad-group-orban-poland/.

- HVG. 2015. “Ipsos: Egymillió szavazót vesztett a Fidesz három hónap alatt”, hvg.hu, January 13. https://hvg.hu/itthon/20150113_Ipsos_Egymillio_szavazot_vesztett_a_Fidesz.

- Jenne, E. K., K. A. Hawkins, and B. C. Silva. 2021. “Mapping Populism and Nationalism in Leader Rhetoric across North America and Europe.” Studies in Comparative International Development 56 (2): 170–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09334-9

- Juhász, A., and Cs Molnár. 2016. “Magyarország sajátos helyzete az európai menekültválságban.” In Társadalmi Riport 2016, edited by Tamás Kolosi and István György Tóth, 263–285. Budapest: Tárki.

- Kelemen, R. D. 2017. “Europe’s Other Democratic Deficit: National Authoritarianism in Europe’s Democratic Union.” Government and Opposition 52 (2): 211–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.41

- Kinneavy, J. L. 1986. “Kairos: A Neglected Concept in Classical Rhetoric.” In Rhetoric and Praxis: The Contribution of Classical Rhetoric to Practical Reasoning, edited by Jean Dietz Moss, 79–105. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press.

- Kolosi, T., and Sz Hudácskó. 2020. “Az Európai Unióval és az euróval kapcsolatos vélemények nemzetközi összehasonlításban.” In Társadalmi Riport 2016, edited by Tamás Kolosi and István György Tóth, 453–461. Budapest: Tárki.

- Kopecký, P., and C. Mudde. 2002. “The Two Sides of Euroscepticism: Party Positions on European Integration in East Central Europe.” European Union Politics 3 (3): 297–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116502003003002

- Körösényi, A., G. Illés, and A. Gyulai. 2020. The Orbán Regime: Plebiscitary Leader Democracy in the Making. Oxon: Routledge.

- Leconte, C. 2010. Understanding Euroscepticism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Leruth, B., N. Startin, and S. Usherwood. 2017. “Defining Euroscepticism: From a Broad Concept to a Field of Study.” In The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism, edited by Benjamin Leruth, Nick Startin, and Simon Usherwood, 3–10. Oxon: Routledge.

- Martin, J. 2013. Politics and Rhetoric: A Critical Introduction. Oxon: Routledge.

- McMahon, R., and W. Kaiser. 2022. “Narrative Ju-Jitsu: Counter-Narratives to European Union.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 30 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2021.1949268

- Meijers, M. J., and H. Van der Veer. 2019. “MEP Responses to Democratic Backsliding in Hungary and Poland. An Analysis of Agenda-Setting and Voting Behaviour.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 57 (4): 838–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12850

- Merkel, A. 2015. “Statement by Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel to the European Parliament.” The Federal Government, October 7. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/chancellor/statement-by-federal-chancellor-angela-merkel-to-the-european-parliament-806312.

- Meyer, M. 1996. “Rhetoric and the Theory of Argument.” Revue Internationale de Philosophie 50 (2): 325–357.

- Meyer, M. 2017. What is Rhetoric? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mos, M. 2020. “Ambiguity and Interpretive Politics in the Crisis of European Values: Evidence from Hungary.” East European Politics 36 (2): 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1724965

- Mos, M. 2022. “Routing or Rerouting Europe? The Civilizational Mission of Anti-Gender Politics in Eastern Europe.” Problems of Post-Communism 70 (2): 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2022.2050927

- Navracsics, T. 1997. “A Missing Debate?: Hungary and the European Union.” SEI Working Paper 1997/21. Sussex: Sussex European Institute.

- Palonen, E. 2018. “Performing the Nation: The Janus-Faced Populist Foundations of Illiberalism in Hungary.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 26 (3): 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2018.1498776

- Pew Research Center. 2016a. “Hungarians Share Europe’s Embrace of Democratic Principles but Are Less Tolerant of Refugees, Minorities.” Pew Research Center, September 30. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/30/hungarians-share-europes-embrace-of-democratic-principles-but-are-less-tolerant-of-refugees-minorities/.

- Pew Research Center. 2016b. “European Opinions of the Refugee Crisis in 5 Charts.” Pew Research Center, September 16. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/16/european-opinions-of-the-refugee-crisis-in-5-charts/.

- Pfau, M. W. 2007. “Who's Afraid of Fear Appeals? Contingency, Courage, and Deliberation in Rhetorical Theory and Practice.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 40 (2): 216–237.

- Pirro, A. L., P. Taggart, and S. van Kessel. 2018. “The Populist Politics of Euroscepticism in Times of Crisis: Comparative Conclusions.” Politics 38 (3): 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395718784704

- Price-Thomas, G., and N. Turnbull. 2018. “Thickening Rhetorical Political Analysis with a Theory of Distance: Negotiating the Greek Episode of the Eurozone Crisis.” Political Studies 66 (1): 209–225.

- Prime Minister’s Office. 2015. “Nemzeti konzultáció a bevándorlásról és a terrorizmusról.” Website of the Hungarian Government, April 24. https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/en/prime-minister-s-office/news/national-consultation-on-immigration-to-begin.

- Sadecki, A. 2022. “From Defying to (Re-)Defining Europe in Viktor Orbán’s Discourse about the Past.” Journal of European Studies 52 (3-4): 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472441221115565

- Schlipphak, B., and O. Treib. 2017. “Playing the Blame Game on Brussels: The Domestic Political Effects of EU Interventions against Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (3): 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1229359

- Scott, J. 2021. “Beyond the Border Fence. The Emergence of Hungary’s Contemporary Bordering Regime.” In In-Security, Symbolism, Vulnerabilities, edited by Andréanne Bissonnette and Élisabeth Vallet, 117–133. Oxon: Routledge.

- Sík, E., B. Simonovits, and B. Szeitl. 2016. “Az idegenellenesség alakulása és a bevándorlással kapcsolatos félelmek Magyarországon és a visegrádi országokban.” REGIO 24 (2): 81–108. https://doi.org/10.17355/rkkpt.v24i2.114

- Styczyńska, N. 2017. “Eurosceptic Parties in the Central and Eastern European Countries: A Comparative Case Study of Poland, Hungary and Bulgaria.” In The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism, edited by Benjamin Leruth, Nick Startin, and Simon Usherwood, 139–154. Oxon: Routledge.

- Szalai, A., and G. Gőbl. 2015. “Securitizing Migration in Contemporary Hungary.” CEU Center for EU Enlargement Studies Working Paper.

- Szczerbiak, A. 2021. “How Is the European Integration Debate Changing in Post-Communist States?” European Political Science 20 (2): 254–260. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00267-w

- Szczerbiak, A., and P. Taggart. 2008. Opposing Europe? The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism, Volume 2: Comparative and Theoretical Perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Szczerbiak, A., and P. Taggart. 2017. “Contemporary Research on Euroscepticism: The State of the Art.” In The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism, edited by Benjamin Leruth, Nick Startin, and Simon Usherwood, 11–21. Oxon: Routledge.

- Szilágyi, A., and A. Bozóki. 2015. “Playing It Again in Post-Communism: The Revolutionary Rhetoric of Viktor Orbán in Hungary.” Advances in the History of Rhetoric 18 (Supplement 1): S153–S166. https://doi.org/10.1080/15362426.2015.1010872

- Taggart, P. 1998. “A Touchstone of Dissent: Euroscepticism in Contemporary Western European Party Systems.” European Journal of Political Research 33 (3): 363–388.

- Taggart, P. 2020. “Europeanization, Euroscepticism, and Politicization in Party Politics.” In The Member States of the European Union, edited by Simon Bulmer and Christian Lequesne, 331–353. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taggart, P., and A. Szczerbiak. 2008. “Introduction: Opposing Europe? The Politics of Euroscepticism in Europe.” In The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism Volume 1: Case Studies and Country Surveys, edited by Aleks Szczerbiak and Paul Taggart, 1–15. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taggart, P., and A. Szczerbiak. 2013. “Coming in from the Cold? Euroscepticism, Government Participation and Party Positions on Europe.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 51 (1): 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02298.x

- Taggart, P., and A. Szczerbiak. 2018. “Putting Brexit into Perspective: The Effect of the Eurozone and Migration Crises and Brexit on Euroscepticism in European States.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (8): 1194–1214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1467955

- Treib, O. 2021. “Euroscepticism Is Here to Stay: What Cleavage Theory Can Teach Us About the 2019 European Parliament Elections.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (2): 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1737881

- Turnbull, N. 2014. Michel Meyer's Problematology: Questioning and Society. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Usherwood, S., and N. Startin. 2013. “Euroscepticism as a Persistent Phenomenon.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 51 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02297.x

- Valuch, T. 2015. A jelenkori magyar társadalom. Budapest: Osiris Kiadó.

- Vasilopoulou, S. 2017. “Theory, Concepts and Research Design in the Study of Euroscepticism.” In The Routledge Handbook of Euroscepticism, edited by Benjamin Leruth, Nick Startin, and Simon Usherwood, 22–35. Oxon: Routledge.

- Visnovitz, P., and E. K. Jenne. 2021. “Populist Argumentation in Foreign Policy: The Case of Hungary under Viktor Orbán, 2010–2020.” Comparative European Politics 19 (6): 683–702. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00256-3

- Wéber, A. 2010. Metamorfózisok: A magyar jobboldal két évtizede. Budapest: Napvilág Kiadó.

- Závecz Research. 2016. “Aktívabbak lettek a választópolgárok.” Závecz Research, October 16. http://www.zaveczresearch.hu/nepszavazas-aktivabbak-lettek-valasztopolgarok/.