ABSTRACT

The Ukrainian far right has attracted massive media interest, from Russian media condemning Ukraine’s alleged Nazi takeover to international media warning of it becoming a transnational far-right hotspot. Countering these misconceptions, this article empirically studies the Ukrainian far-right movement to explain its mobilisation dynamics 2004–2020. Why did mobilisation peak in 2010–2014, and decline after? I argue that a combination of political and discursive opportunities offers an answer. However, these opportunities played out differently in Ukraine – a hybrid regime at war – than conventional social movement theory suggests. The Ukrainian case thus furthers our understanding of far-right movements beyond consolidated democracies.

Introduction

At the onset of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin claimed that the aim was to “de-Nazify” Ukraine (Fried Citation2022). This narrative has roots in the Soviet era when Ukrainian nationalists and pro-independence activists were branded “fascist” by Soviet authorities (Kuzio Citation2015). It was revived in 2014, when sustained protests on Kyiv’s Maidan square led to an overthrow of then-President, pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych, an event Russian state media framed as a “fascist coup” (Lucas Citation2016). Interpreting Maidan as a Western anti-Russian plot, the Russian disinformation campaign aimed to destabilise Ukraine, weaken international support for the post-Maidan government, and justify Russian military intervention (Lucas Citation2016).

While Russian media participated in state propaganda, Ukraine and its far right also attracted attention beyond Russia, as foreign fighters from far-right milieus participated in the conflict in eastern Ukraine (Rekawek Citation2015). Moreover, Ukraine was portrayed as a far-right tourist hotspot: extremists from all around the world travelled to Kyiv to attend Asgardsrei, a National Socialist black metal festival (Colborne Citation2020).

While the Ukrainian far right is largely understudied, intensified media attention – either as propaganda or a byproduct of sensationalism – creates multiple misconceptions about it. The problem with both media narratives about the Ukrainian far right is that they are not primarily about the Ukrainian far-right movement itself. That is, however, what this article is about, aiming to empirically investigate the movement’s activities for almost two decades. How has far-right mobilisation in Ukraine evolved over the years, and how can we explain this evolution?

Besides mapping the actual landscape of the Ukrainian far right, then, this article seeks to explain why far-right mobilisation, operationalised as a set of extra-parliamentary protest events, peaked between 2010 and 2014 – just as the movement experienced an electoral breakthrough – but has declined since. To account for this pattern, I examine the movement’s extra-parliamentary activity and the context in which it operates. To do so, I rely on an original database of far-right protest events from the onset of the Orange Revolution in 2004–2020, and trace variation over time through protest event analysis (PEA).

I apply the political process approach within social movement theory. This approach places the far-right movement into its wider environment and argues that, along with grievances creating necessary conditions for movements to emerge, mobilisation varies depending on the extent to which the surrounding environment enables it (Tarrow Citation2011). I find that political and discursive opportunities can help explain not only the 2010–2014 peak in protest, but also the relative decline since. An important reason is that the Ukrainian far-right movement’s ideology is centred around anti-Russian sentiments, unlike most other far-right movements. Therefore, its mobilisation was shaped by opportunities related to a pro-Russian government and the war with Russia. This finding highlights the relevance of the movement’s rather unique anti-Russian ideology for understanding its mobilisation dynamics, in contrast to popular (mis)conceptions created through Russian propaganda or sensationalist media.

The article begins by conceptualising the far right and introducing the contemporary Ukrainian far-right movement. I also briefly describe how Ukraine’s recent history has created considerable grievances serving as necessary conditions for far-right mobilisation. Next, I discuss how social movement theory is designed to explain protest mobilisation, focusing on how changing opportunities may account for variation in mobilisation patterns across time and space. In doing so, I emphasise how most existing research relies on findings from Western consolidated democracies and question whether similar dynamics are to be expected in hybrid regimes at war. In other words, to what extent can social movement theory be applied to volatile non-democratic contexts? I then move on to explain how my data on far-right protest and mobilisation opportunities in Ukraine were collected and analysed. Finally, I present key findings from my analysis and then draw on these findings to illustrate how the Ukrainian case – a hybrid regime and a country at war – can enrich our understanding of far-right movements more generally.

The far-right social movement in Ukraine

As most other concepts in social sciences, the terms used to describe far-right politics are debated. However, as Carter (Citation2018) has found, there is more commonality among definitions than often assumed. Most cited conceptualisations cover the same three core elements: nationalism, authoritarianism, and anti-democracy. Accordingly, I use the term “far right” in this article to refer to a range of actors that share ideological foundations in exclusionary nationalism, prioritising “natives” over “foreigners”, and authoritarianism, the belief in a strict societal order, where anything considered deviant should be punished harshly (Mudde Citation2019). In terms of anti-democracy, the umbrella term “far right” includes radical right parties that largely abide by the democratic rules of the game but oppose liberal democracy and minority rights, as well as extreme right groups that oppose the democratic system as a whole (Pirro Citation2023). Until recently, the dominant practice in the social sciences has been to distinguish between the two. However, scholars are increasingly recognising that such a distinction can be redundant and obscure the blurring boundaries between radical and extreme right actors in terms of both ideology and collective action (see e.g. Castelli Gattinara, Froio, and Pirro Citation2021; Volk and Weisskircher Citation2023). This is especially the case in Central and Eastern European far-right movements (see e.g. Minkenberg Citation2017). Therefore, I use the umbrella term “far right” to refer to all actors combining nativist and authoritarian ideologies.

The application of this umbrella term can be contested. Indeed, some authors argue that the left-right distinction is not applicable to post-Soviet politics at all (e.g. Lawson, Römmele, and Karasimeonov Citation1999). One possible criticism against placing the Ukrainian far right in the wider literature on far-right movements, then, is that the far right in the post-Soviet space may not be comparable to that in Western democracies. That said, the political position of an actor should be based on its political ideology, rather than the political context in which it operates. As such, all actors included in adhere to far-right ideology in the sense of promoting nativism and authoritarianism. Thus, rather than separating these actors from the wider literature on far-right movements, I seek to situate them within it (see also Minkenberg Citation2017). Doing so also helps avoid the already problematic specialisation of the literature on the far right and its divorce from wider social science debates (see Mudde Citation2010 and Castelli Gattinara Citation2020).

Figure 1. Far right movement in Ukraine, 1990s–2020. Some actors from early 1990s (marked in grey) do not exist anymore or have disappeared from public space. Actors marked in squircles are the most prominent far-right parties as of 2020, while squares represent non-party organizations.

The contemporary Ukrainian far right includes parties, organisations, and informal groups (see ). Despite ideological differences and interpersonal conflicts, the movement shares a commitment to nativist and authoritarian ideas. Parties like Freedom, Right Sector, and National Corps have previously participated in elections, although they have assumed “movement party” roles, navigating between institutional and extra-institutional politics (Pirro and Castelli Gattinara Citation2018). The rest of the movement includes small, overlapping groups like Tradition and Order, White Hammer, Sokil, etc., with little electoral ambition. Instead, these groups have organised cultural and sports events and engaged in contentious politics, e.g. by mobilising against LGBTQ + activism (Tradition and Order) or attacking Roma camps (C14). Some groups are often hired as thugs to defend business interests (Likhachev Citation2019).

The movement’s roots go back to the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), established in 1929. The OUN has a controversial history, including an explicit – albeit short-lived – plan of establishing Ukraine as an ally of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union (Motyl Citation2010; Rudling Citation2013; Gomza Citation2015). Many contemporary far-right actors in Ukraine have claimed to continue the OUN’s legacy, for example, by finding justification of their own ideological positions in the texts written by OUN leaders (Rudling Citation2013; Iovenko Citation2015; Mierzejewski-Voznyak Citation2018).

As Ukraine became independent, the OUN’s successors fighting for independence gradually lost salience. To some extent, this also applies to scholarly interest in the Ukrainian far right; unlike Ukrainian nationalism of the early 1900s, the contemporary far right and its political participation is relatively under-researched (Umland Citation2020). There has been a surge in interest following the 2012 electoral success of Freedom and the far right’s participation in the Maidan revolution and war efforts since 2014 (Likhachev Citation2013; Umland and Shekhovtsov Citation2013; Bustikova Citation2015; Ishchenko Citation2016; Kudelia Citation2018; Risch Citation2021; Gomza and Zajaczkowski Citation2019; Colborne Citation2022; Mutallimzada and Steiner Citation2023). Yet the literature on the far right in general, greatly inspired by the electoral success of Western European parties after the Cold War, remains dominated by studies on the electoral performance of these parties to this day (Castelli Gattinara Citation2020). As a result, far-right social movements generally, and those beyond the region of Western Europe specifically, remain underexplored in comparison (Castelli Gattinara Citation2020). Empirical research on the extra-parliamentary far right in Ukraine has been relatively rare, as much of the literature seems to assume that a lack of sustained electoral success implies a lack of political relevance (Mierzejewski-Voznyak Citation2018; Ishchenko Citation2018; Umland Citation2020).

While understudied by scholars, the extra-parliamentary far right in Ukraine and its transnational links have attracted considerable international media attention. However, this attention has been rather sensationalist, overlooking what the movement actually looks like at the national level. This has produced a series of misconceptions, ready to be exploited by the Russian propaganda machinery. To help correct such misconceptions, I take a national perspective, mapping the actual landscape of the Ukrainian far right in a longitudinal perspective and examining its extra-parliamentary activity for almost two decades since the onset of the Orange Revolution.

Ukraine after the orange revolution

The dissolution of the Soviet Union triggered political, economic, and cultural transformations in its former members, creating fertile grounds for far-right mobilisation instrumentalising resentment toward rapid change (Minkenberg Citation2017). Ukraine was no exception.

Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, following Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution, reignited hopes of democratic transformation in the former Soviet Union. However, post-revolutionary Ukraine has been marred by political and economic crises hindering substantive reforms (Kuzio Citation2016). In this sense, Ukraine resembles other regimes emerging from the third wave of democratisation that combine both authoritarian and democratic features. In general, scholarship has treated these regimes as diminished subtypes of either democracy or autocracy, transitional regimes, or regime types in their own right. Recognising their durable quality and recurring fluctuations between democratic and authoritarian tendencies, scholars have increasingly argued towards conceptualising hybrid regimes as an in-between regime type (Bogaards Citation2009; Mufti Citation2018). Like other hybrid regimes, over the years Ukraine has manifested a combination of democratic features like competitive elections together with weak rule of law and formal institutions, as well as widespread corruption (Levitsky and Way Citation2010; Matsiyevsky Citation2018).

The Orange Revolution highlighted polarisation between the pro-Western national democratic camp – the Orange coalition – and the pro-Russian camp dominated by the Party of Regions (PoR). Polarisation intensified after the 2006 elections, when PoR obtained 32% of the vote, forming a government with pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych as Prime Minister. The aftermath of the revolution was thus marked by power struggle between the PoR-majority government and parliament (Verkhovna Rada) and the Orange coalition president, Viktor Yushchenko.

Hopes of further structural and economic reforms waned as the Orange coalition succumbed to internal conflicts. The conflict culminated in a split in late 2008 (Diuk Citation2014). Dividing the Orange vote, the breakup facilitated the election of former Prime Minister Yanukovych as president in 2010.

Under Yanukovych, Ukraine drifted toward the pro-Russian orbit, alienating the pro-Western electorate. In 2013, Yanukovych refused to sign Ukraine’s association agreement with the EU. His decision prompted protests at Kyiv’s Maidan square. Protest spread to other cities and culminated in his overthrow in February 2014 (Diuk Citation2014).

Declaring Euromaidan a “fascist coup,” Russia annexed Crimea, a region in Southern Ukraine. The conflict escalated when Russia-backed “separatists” in Donetsk and Luhansk regions proclaimed independence and fighting evolved into an interstate war. Ukraine launched a military operation against pro-Russian forces, while Russia claimed it was forced to “defend Russian speakers” (Coalson Citation2014). Despite ceasefire agreements, the conflict remains unresolved. In February 2022, the conflict escalated further, with Russian recognition of separatist regions of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent republics and the subsequent full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Following Yanukovych’s ouster, the PoR dissolved. This left political space generally Western-oriented, but gradually split between nationalist and liberal camps (Interview with Umland, 2021; Interview with Bukkvoll, 2022). The former was dominated by Petro Poroshenko, elected president in 2014, while the latter has been led by the Servant of the People party of Volodymyr Zelenskyy who defeated Poroshenko in the 2019 presidential elections.

Ukraine’s post-independence history has thus been anything but stable. Undergoing “quadruple transition” – political and economic transformation and simultaneous state- and nation-building – Ukraine has endured continuous crises hindering structural reforms (Kuzio Citation2016). Consequently, it remains among the poorest and most corrupt countries in Europe (Kuzio Citation2016), offering fertile grounds for far-right mobilisation to instrumentalise these grievances.

Theoretical framework: explaining far-right mobilisation

How has far-right mobilisation in Ukraine evolved over time, and how can we explain this evolution? Explanations of far-right mobilisation include two overarching and complementary approaches. The first includes collective behaviour and modernisation theories positing that movements emerge because of grievances, such as poverty or relative deprivation (see, e.g. Gurr Citation1971; Merkl Citation2003). The central argument is that rapid transformation leaves parts of society behind, fuelling resentment and support for actors wishing to undo these changes (Golder Citation2016). In Europe, cultural grievances stemming from increased immigration have sparked far-right protest (Castelli Gattinara, Froio, and Pirro Citation2021). In the former Communist states specifically, the far right has capitalised on resentment toward rapid post-Communist modernisation (Minkenberg Citation2017).

However, far-right mobilisation varies across space and time. Considering this, a second set of theories takes a complementary, political process approach, focusing on the environment surrounding the movement (Tarrow Citation2011). This approach argues that explanations focusing exclusively on grievances are incomplete. Grievances are necessary for a far-right movement to emerge, but they alone cannot account for variation in far-right protest. To engage in collective action, a movement needs to operate in an enabling environment (Tarrow Citation2011).

Indeed, despite the volatile recent history, economic and cultural grievances in Ukraine have remained relatively stable since 2004: poverty, unemployment, and immigration levels do not fluctuate much (“Ukraine Poverty Rate Citation1992–Citation2022” Citation2021; “Ukraine – Unemployment Rate Citation1999–Citation2020” Citation2021; “Ukraine: Key Migration Statistics” Citation2021). Nonetheless, as this article will show, far-right protest has varied over time. To explain changing protest dynamics, we need to place the movement in its context, connecting macro-level grievances with micro-level behaviour, that is, non-parliamentary mobilisation.

Paying attention to the environment surrounding social movements, I take the political process approach that emphasises mobilisation opportunities. Opportunities refer to aspects of the wider environment that enable or hinder collective action (McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald Citation1996; Tarrow Citation2011). In their study of the far-right in Germany, Italy, and the US, Caiani and colleagues (Citation2012) identify a set of legal, political, and discursive opportunities that may enable or hinder far-right mobilisation specifically:

Among legal constraints, prohibition of discrimination and fascist and racist speech and actions are expected to hinder far-right mobilisation (Caiani, Della Porta, and Wagemann Citation2012; Caiani and Della Porta Citation2018). We would therefore expect mobilisation to decline as such laws are introduced. However, in contrast to consolidated democracies, legal opportunities may be less decisive in hybrid regimes (Gelashvili Citation2022).

Political opportunities, in turn, refer to access of far-right actors to political institutions and decision-making bodies, (in)stability of political elite alignments, and the extent to which far-right actors are repressed. In Western democracies, far-right movements are more likely to mobilise and turn to violence when they lack access to formal politics (Koopmans Citation1996; Hutter Citation2014). A far-right party represented in the parliament or in decision-making bodies can voice the grievances of the movement, mitigating a relatively costlier strategy of street-level action. Indeed, Minkenberg (Citation2019) has found that countries with strong far-right parties (with more than 4% vote in parliamentary elections) tend to have a marginal extra-parliamentary movement. However, whereas this pattern largely holds in Western Europe, some Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries with strong far-right parties, like Poland and Hungary, also have strong movements (Minkenberg Citation2019). Largely investigated in the context of consolidated democracies, far-right movement–party interaction remains underexplored in hybrid regimes.

Finally, discursive opportunities refer to general acceptance of the far right, i.e. whether it has political allies and whether its ideas resonate or are stigmatised. Far-right protest usually follows increased immigration and rises as nativist and authoritarian opinions prevail. However, radicalised public discourse can work both ways: sometimes, the far right gains salience as mainstream parties move to the right, adopting parts of far-right ideology, while in others, mainstream parties effectively absorb far-right supporters (Bustikova Citation2018). As with political opportunities, research on the impact of discursive opportunities focuses on consolidated democracies in (Western) Europe, leaving hybrid regimes underexplored.

Thus, research on far-right mobilisation opportunities has mostly been based on Western democracies and has so far found mixed results. As a hybrid regime, Ukraine offers an interesting case to study how changing opportunities shape far-right mobilisation. Examining how opportunities play out in a hybrid regime context is relevant for our understanding of the far right in general, especially as many formerly consolidated democracies have been backsliding in recent years (Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2018).

The Ukrainian case is interesting not only as a hybrid regime, but also as a country experiencing war. As social movement theorists have argued, opportunities fluctuate with important destabilising events, like wars and economic crises (McAdam and Tarrow Citation2018). However, research has yet to explore the effect of wars on far-right mobilisation: on the one hand, having an external enemy to the nation could be a powerful source of negative mobilisation, and activists may benefit from the “weakening of the state” to advance their agenda (McAdam and Tarrow Citation2018). On the other hand, wars can close off mobilisation opportunities as citizens “rally around the flag”. Looking at how opportunities can help explain variation in far-right protest in the Ukrainian case, I aim to contribute to far-right scholarship, expanding the social movement approach to a hybrid regime and a country at war.

Research design

In line with recent literature studying the far right as a social movement (see also Castelli Gattinara, Froio, and Pirro Citation2021), I operationalise mobilisation as a set of extra-parliamentary protest events in which far-right groups participate. I use Protest Event Analysis (PEA), a method of content analysis of contentious action, to examine mobilisation over time. PEA entails gathering and analysing data on various characteristics of protest events, such as date, location, size, participants, issue, countermobilisation, police presence, and event type. Importantly, the method helps track different types of events: conventional (e.g. press conferences), confrontational (sit-ins, barricades), demonstrative (rallies, petitions), and violent (including light, symbolic violence, such as burning flags, and heavy violence, i.e. physical attacks). Thus, PEA expands far-right scholarship beyond an exclusive focus on either electoral behaviour or violent action, incorporating a broader action repertoire.

A protest event is defined broadly to include any public contentious act, occurring within a 24-hour timespan and in specific areas, with mostly similar aims and participants (Hutter Citation2014).Footnote1 Thus, if a far-right group organises rallies on the same issue in two locations simultaneously, both rallies will be coded as a single protest event.

For PEA, I created a database of far-right protest events in Ukraine between 2004, the onset of the Orange Revolution, and 2020. The database includes events organised by active far-right actors in Ukraine.Footnote2 While PEA databases can be constructed via three alternative sources of data (media sources, police records, and activist group accounts), I have chosen to rely on media reports due to their advantages over both police- and activist records. Media sources are both more regular over time and less prone to under- and over-reporting. While police records only include violent and criminal incidents, underestimating the total number of events, both far-right groups and their challenger groups tend to exaggerate protest prevalence. By contrast, events not appearing in the media are considered as non-events as they will rarely reach, let alone elicit response from, authorities (Koopmans Citation2004). Moreover, quality media sources tend to be more comparable across countries than police records or activist accounts. Police definitions vary from country to country, as do activist groups and their archiving practices. The latter are often also unsystematic and incomplete, rendering long-term analysis difficult, if not impossible.

This is certainly not to say that media sources are unbiased. Importantly, though, media is biased systematically, not randomly: negative, large-scale, and conflict-related events consistently attract more attention (Koopmans Citation1998). Media also tends to be consistent in terms of reporting PEA-relevant aspects – “hard facts,” or information on the time, place, announced goal, etc., of protest. Arguably, even “hard facts” are interpreted by the journalist, especially when it comes to aspects like the number of participants. Although impossible to resolve, I account for this challenge by creating a coding process that makes the potential bias systematic, so that general dynamics can be analysed. I also include data over a period long enough to permit the detection of significant trends and variation.

To create the database, I coded more than 4,000 articles from the news agency UNIAN (Ukrainian Independent Information Agency of News). After a pilot study comparing the coverage of far-right events by different media sources in Ukraine, I opted for UNIAN, for several reasons. Along with its nationwide coverage in Ukrainian and Russian, trustworthy reputation, and archive accessibility, I selected UNIAN considering the advantages of online versus print media: more frequent publication and continuous updates. UNIAN articles were retrieved from the Factiva database using an actor-focused search string.Footnote3

There are two possible criticisms for this research design. First, using a single news source does not take advantage of recent advances in automatic text retrieval and coding. Indeed, automatic coding would have generated more data from various sources. However, such a research design would by definition have different ontological, epistemological, and methodological underpinnings. For the purposes of this article, I rely on one resource to collect data that lends itself to not only quantitative, but also qualitative analysis by one person. This was imperative for a deeper look into the organisation and framing of protest events and their targets, as well as qualitative changes in similar protest events over time.

Second, using an actor-focused search string excludes events whose organisers news articles describe in generic terms, e.g. “nationalists”, “radicals”, etc. For the purposes of this article, I exclude these terms for three reasons. First, the use of such generic terms is highly subjective, depending on individual journalists covering the issue. Second, it can also change significantly over time, depending on what issues are salient at any given point. For example, the same far-right actor can be described as “anti-immigrant” when rallying against asylum seekers and “anti-LGBTQ+” when rallying against a Pride event. Third, it can vary significantly from country to country. An actor-focused search string avoids these issues and makes the dataset more comparable to similar studies in other country cases.

To account for protest variation, I trace legal, political, and discursive opportunities, looking at how they affect protest. Importantly, opportunity structures are dynamic, changing with political, social, and economic processes – arguably more so in hybrid regimes than in consolidated democracies. To reflect the dynamic nature of opportunities, I observe their evolution over time. Note also that opportunities do not automatically translate into political action: indeed, as McAdam argued in his original formulation of the political process model (Citation1982, 48), the opening of opportunities offers potential for mobilisation, but what stands between opportunity and action is the actors’ own perception of the former. Thus, opportunities have to be visible to social movement actors and perceived as opportunities in order to lead to collective action. While an overly structuralist view of “objective” opportunities would assume that opportunities automatically lead to action, in this article, I take the actual mobilisation of the far-right movement as a proxy of opportunities being visible to the movement, as well as the movement interpreting them as open.

To measure changes in opportunity structures, my original plan was to combine secondary and primary sources: published work on Ukraine and its far-right movement and expert interviews with researchers working on Ukrainian nationalism and far right that would supplement and contextualise data from secondary sources. However, my planned extensive fieldwork in Ukraine in late February 2022 had to be cancelled due to the Russian invasion. In addition to logistical difficulties, the war also made it unreasonable and insensitive to interview Ukrainian experts and researchers who were going through a difficult time. Thus, in the analysis of opportunities, I rely on previously published work and my pre-February 2022 pilot interviews with 5 experts (see the list of interviewees in Appendix 1).

Protest event analysis 2004–2020

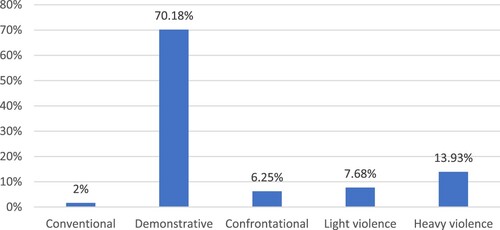

Let us begin with the evolution of far-right mobilisation over time. Through PEA of the extra-parliamentary activity of the Ukrainian far right, I identified 560 events. Most of these events were demonstrative (see ), involving non-violent rallies. Conventional and confrontational events were rare, while violent events (both light and heavy violence) constituted around 21% of all recorded events. This finding challenges the conceptualisation of far-right politics as limited to electoral politics or violence, as demonstrative non-violent events are the most prominent manifestation of far-right politics in Ukraine.

Freedom seems to be the most visible actor. This finding questions the dichotomous view of far-right actors as either parties engaged in electoral politics or movements engaged in contention. As a movement party, Freedom seems to also drive contentious politics, both inside and outside the electoral arena.

Most events took place without counterdemonstrations or police interference. Only a minority (16%) was opposed by a counter-rally. In some cases, the far right counterprotested Communist or liberal demonstrations (e.g. feminist marches or LGBTQ + Pride). Police presence was recorded for around 30% of events; however, the police only interfered when events turned violent.

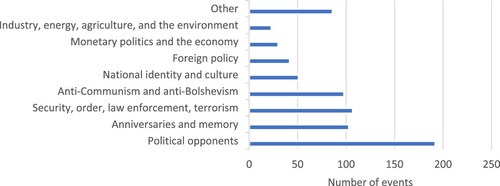

PEA shows that the Ukrainian far right is first and foremost anti-Russian. Qualitative analysis of events shows that protest against Russia is expressed in different kinds of events, e.g. rallies opposing political actors considered pro-Russian, vandalism/demolitions of Soviet memorials, and opposition to Russian foreign policy against Ukraine (see ). In comparison, protest against ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities in Ukraine remains low over the years.

This sets the Ukrainian far-right apart from the dominant stream of research: in most Western democracies, research on which informs our understanding of the contemporary far-right, the defining feature of the movement has been its vehement opposition to immigration (Castelli Gattinara, Froio, and Pirro Citation2021). While the Ukrainian far-right shares an ideological foundation in nativism and authoritarianism with these movements, it hardly ever rallies against immigration. Instead, its nativist core is mostly channelled through anti-Russian attitudes. This distinguishes it from not only its Western European counterparts, but also similar movements in CEE, with an ambiguous, at best, stance toward Russia (Shekhovtsov Citation2018). Interestingly also, the movement differs from its CEE counterparts in terms of relatively rare anti-Semitic and anti-Roma protest. Furthermore, the Ukrainian far right focuses less on religious events and anti-LGBTQ + rallies.

Instead, the movement focuses on Ukraine’s internal and foreign policy challenges. While international media paints the picture of a highly transnational movement, PEA shows that the Ukrainian far right mostly mobilises around Ukraine-specific issues, voicing disagreement with political opponents (other parties, officials, etc.) and raising issues related to security, order, and law enforcement (see ). These two issues account for 34% and 19% of all protest events, respectively. Other issues dominating far-right protest are anniversaries and memory and anti-Communism and anti-Bolshevism, each accounting for 18% of protest events.

Anniversary and memory events include tributes to OUN and its insurgent army, UPA (Ukrayins’ka povstans'ka armiya). Some events, previously celebrated only by far-right groups, gradually become more prominent. One illustration is January 1, OUN leader Stepan Bandera’s birthday, which was usually celebrated in Western Ukraine with several hundred far-right activists and former UPA veterans calling for recognition of Bandera as Hero of Ukraine. After President Yushchenko awarded this title to Bandera in 2010, the celebrations extended to the capital and beyond, gathering thousands. Similarly, October 14, the Day of the Defenders of Ukraine that marks the creation of the UPA, usually celebrated with a couple hundred far-right activists, has evolved into a national holiday, gathering thousands. The day is associated with military struggle for independence, including the Crimean and Donbas conflicts, overshadowing its far-right origins (Interview with Likhachev, 2021).

Similarly to anniversary events, anti-Communist and anti-Bolshevist events also increase over time. In the aftermath of the Orange Revolution, the far right organised rallies calling for “decommunisation”, a process of removing all monuments and symbols associated with the Communist regime. After the law was adopted in 2015, the number of anti-Communist rallies grew: these events involved vandalism or destruction of Soviet memorials and statues.

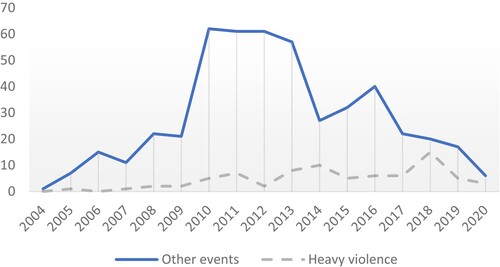

Another puzzling finding is the temporal variation of protest. As shows, the level of physical violence remains low over time, while protest in general peaked 2010–2014Footnote4 and has gradually declined since.

This pattern contradicts much of the existing research on far-right party-movement relationships. In Western democracies, far-right movements are more likely to mobilise when they lack access to formal politics and vice versa, having a far-right party in the parliament with more than 4% of the vote can voice the movement’s grievances, mitigating the relatively costlier strategy of street-level activism (Caiani, Della Porta, and Wagemann Citation2012; Minkenberg Citation2019).

In Ukraine, protest peaked when the movement had unprecedented access to formal politics: in 2009, Freedom obtained 34.7% vote in the Ternopil region, and in the 2012 parliamentary elections, it received 10.5% vote nationwide. However, contrary to previous research, more access did not discourage mobilisation. While heavy violence remained relatively stable throughout (see ), protest peaked when the movement had more representation in formal institutions. Correspondingly, while the failure of Freedom to get re-elected in the 2014 and 2019 elections should have reignited street-level activism, protest has in fact declined since 2014. Can changing opportunities help explain this pattern?

Mobilisation opportunities 2004–2020

Legal opportunities

Legal opportunities for the Ukrainian far-right have not changed substantially over time. The Constitution of Ukraine (Article 24) and the Criminal Code (Article 161) protect equality to a certain extent, prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of race, skin colour, language, and religious, political, and other beliefs. The incitement of “national, racial, or religious enmity and hatred” is also banned. Importantly, however, this refers only to direct incitement to violence and is rarely executed (Interview with Likhachev, 2021). In addition, gender and sexual orientation are not included.

Since 2014–2015, the Ukrainian parliament has adopted two measures potentially restricting far-right mobilisation: the 2014 Law, “On preventing and combatting discrimination in Ukraine” and the 2015 Law, “On condemnation of communist and national-socialist (Nazi) totalitarian regimes in Ukraine and prohibition of propaganda of their symbols” (hereafter: decommunisation law).

However, the legislative framework of Ukraine falls behind international standards (Gordon Citation2020). To begin with, the 2014 anti-discrimination law was adopted only after Freedom lobbied the removal of controversial norms, e.g. “sexual orientation and gender identity” and “declared intentions to discriminate” (“Anti-Discrimination Legislation” Citation2017).

In addition, the decommunisation law, as the name suggests, was adopted with the aim of eliminating Communist-era monuments and memorials and removing Soviet names from Ukrainian toponymy. While the law also bans Nazi symbols, this extends only to the state symbols of Nazi Germany.

Consequently, Ukrainian far-right groups can use these symbols, at most with tiny modifications (Interview with Umland Citation2020; Interview with Likhachev, 2021). For example, actors like the SNPU (the predecessor of Freedom), Azov, and Social-National Assembly, have used a monogram of Latin letters “I” and “N”, allegedly referring to the slogan “Idea of the Nation,” that mirrors the wolf’s hook, a common neo-Nazi symbol (Citation“Reporting Radicalism in Ukraine” n.d.). The name of Sich (spelled C14), a smaller far-right group, is a coded reference to Adolf Hitler, also alluding to a popular white supremacist slogan, “14 words” (“We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children”).

Despite the 2014–2015 legislative changes, therefore, legal opportunities for far-right mobilisation have not changed substantially over time. Legislative measures that could be expected to hinder far-right mobilisation proved practically ineffective. Unlike consolidated democracies (Caiani, Della Porta, and Wagemann Citation2012), legal opportunities might not be decisive in hybrid regimes like Ukraine.

Political opportunities

In contrast, political opportunities have fluctuated. While state capacity and willingness to repress far-right protest has remained low (Likhachev Citation2019; Gordon Citation2020), instability among political elites has offered a window of opportunity for the far right.

Generally, the movement has been electorally marginal. The only exception was the 2012 election of Freedom to Verkhovna Rada, preceded by similarly unprecedented electoral success in Ternopil. However, Freedom’s electoral success was “exceptional rather than symptomatic” (Umland Citation2020), conditioned by two factors: shifts in elite alignments and Russian threats to Ukraine’s sovereignty.

In the immediate aftermath of the Orange Revolution, polarisation between the pro-Western national democratic camp (the Orange coalition) and the pro-Russian anti-liberal camp (dominated by PoR) restricted space for the far right, especially as the former attracted voters with anti-Russian and far-right ideas (Shekhovtsov Citation2011). Soon after, however, internal conflicts in the Orange camp caused instability in political elite alignments. This carved out space for the far right, especially Freedom. This conflict was evident in Ternopil, dominated by parties sympathetic to the Orange cause: in 2009, Freedom obtained most of its votes at the expense of Orange parties (Shekhovtsov Citation2011).

Although the extraordinary success in Ternopil was a product of elite conflicts, Freedom then began to be taken seriously (Shekhovtsov Citation2011; Likhachev Citation2013). After 2010, when the PoR candidate Yanukovych became president, conflicts within the Orange camp intensified, creating a favourable environment for Freedom and setting the stage for its success in 2012 (Bustikova Citation2015; Kuzio Citation2015; Umland Citation2020). Some have argued that Freedom’s national breakthrough was aided by the PoR, to weaken the Orange forces (Kuzio Citation2016).

Once in parliament, however, Freedom did not live up to the expectations of challenging Yanukovych’s pro-Russian politics. Access to formal politics did not translate into political influence, as Freedom lacked decision-making power; indeed, Freedom representatives were not active in the Verkhovna Rada at all (Interview with Likhachev, 2021). After Maidan, Freedom lost its source of negative mobilisation, with no pro-Russian ruling elite to oppose (Shekhovtsov Citation2015). Furthermore, if before the war, the Russian threat to Ukrainian sovereignty was why people supported Freedom (Bustikova Citation2015), following the annexation of Crimea, all mainstream parties incorporated anti-Russian rhetoric, stripping Freedom of its niche (Shekhovtsov Citation2015; Interview with Bukkvoll 2022). Consequently, Freedom failed to overcome the electoral barrier in subsequent elections.

Similarly short-lived was the access of the far right to executive power. In the interim post-Maidan government, Freedom obtained four ministerial posts (Umland Citation2020), but after the electoral failure in November 2014, they were not reappointed. Moreover, the paramilitary units associated with the far right that participated in the Crimea and Donbas conflicts were integrated into defence and law enforcement bodies (Likhachev Citation2019; Interview with Bukkvoll, 2022). Electorally, however, the post-Maidan period marked a return of far-right actors to political margins.

As we have seen, instability of elite alignments opened a window of opportunity for the far right, enabling access to formal institutions. Yet, this opportunity did not play out as social movement theories would expect. Contrary to consolidated democracies, where salience in one arena often implies decrease of salience in the other (Hutter Citation2014), in Ukraine, access did not imply political power and thus failed to discourage street-level protest. As a “movement party” oscillating between electoral and protest arenas, Freedom played a peculiar role in the opportunity structure: on the one hand, its strategic decisions were conditioned by changing political opportunities, and on the other, its decisions to navigate both arenas of contention also constructed these opportunities. Despite parliamentary representation, Freedom failed to voice the grievances of the movement in conventional politics, and thus resorted to street-level contention. Accordingly, losing access after 2014 did not prompt more protest.

Discursive opportunities

Similarly to political opportunities, discursive opportunities for the far-right have also been fluctuating. Unlike some Western European democracies, mainstream parties in Ukraine have not formed a cordon sanitaire, demarcating the far-right from liberal democratic actors. On the contrary, mainstream actors increasingly incorporate parts of the far-right playbook.

In the last years of his presidency, Yushchenko pursued memory politics that inadvertently legitimised parts of far-right ideology (Ishchenko Citation2011). It glorified the OUN and UPA, brushing off their controversial history, including their collaboration with Nazi Germany and the mass atrocities against Jews and Poles, as well as Ukrainians who opposed it (Rudling Citation2013; Rossolinski-Liebe Citation2014; Shkandrij Citation2015; Motyka Citation2022). Instead, OUN-UPA leaders were lionised as martyrs and protagonists of resistance. In 2010, Yushchenko’s move to posthumously award the Hero of Ukraine title to OUN leader Bandera elicited little criticism from public intellectuals and liberal circles (Rudling Citation2013).

The glorification of OUN-UPA contributed to their acceptance: while in 2009, only 14% of Ukrainians were positive toward them, in 2015, 41% supported the recognition of their struggle for independence (Mierzejewski-Voznyak Citation2018). Far-right actors like Freedom, claiming to continue OUN legacy, were thereby perceived as heirs of the resistance movement, as a “perhaps excessive but still legitimate expression of Ukrainian national identity” (Umland Citation2013; see also Shekhovtsov Citation2011).

After Yanukovych came to power, his controversial policies made nationalist stances even more salient. In 2010, for example, Yanukovych and then-Russian President Medvedev signed the Kharkiv Pact, extending the Russian lease on a naval base in Crimea until 2042. Since Russian presence in the Black Sea had long been perceived in Ukraine as a sovereignty threat, many saw this as “the final nail in the coffin of the Orange Revolution” (Harding Citation2010). In 2012, the parliament adopted a controversial law granting regional authorities the right to declare Russian as the second official language.

Such policies “radicalised large parts of Ukraine’s patriotic and otherwise non-extremist electorate” (Umland Citation2020) and made mainstream political actors more accepting to the far right. In the run-up to the 2012 elections, for example, the anti-Yanukovych coalition included Freedom, trying to improve its reputation and “whitewash the previous quasi-fascist image” (Umland Citation2013).

The Maidan Revolution and the war further mainstreamed the far right, not least due to its participation in war efforts (Interview with Gentile, 2021; Interview with Bukkvoll, 2022). These events centered the political debate around Ukraine’s sovereignty and geopolitics. As long as the anti-Russian position of the far right coincides with the increasingly nationalist rhetoric of mainstream politicians, mass media, and public intellectuals, the movement is tolerated by liberals and conservatives alike. This blurs the lines between “mainstream and extreme politics, civil and uncivil society, moderate patriotic and ultra-nationalist groups” (Umland Citation2020, 262).

President Poroshenko, coming to power after Maidan, also adopted an increasingly nationalist stance, manifest in his slogan “Army, language, faith!”. This stance was evident in policies promoting Ukrainian language and decommunisation and culminated in the separation of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church from the Moscow Patriarchate (Gordon Citation2020). Thus, Poroshenko took over the nationalist discourse, continuing the legacy of Yushchenko’s last years in power (Interview with Umland Citation2020).

This mainstreaming of the far right does not necessarily warrant acceptance and legitimisation of its ideology, however. While the population seems to agree with the anti-Russian stance of the far-right, with favourable attitudes toward Russia falling from 71% in 2007 to 32% in 2019 (“Global Attitudes & Trends Database” Citationn.d.) and rising confidence in Ukraine’s Western partners, EU and NATO, this did not translate into increased far-right (nativist and authoritarian) attitudes.

Indeed, despite apparent disapproval of Russia, the majority has continued to display a favourable attitude toward Russian people. Up until the full-scale invasion, the rate kept hovering above 85% (“Global Attitudes & Trends Database” Citationn.d.).Footnote5 As for attitudes toward other minorities, a relatively small percentage of the population opposes having immigrants and people of a different race or religion as neighbours: these rates remain around 20% over the years (“WVS Database” Citationn.d.).

Acceptance toward LGBTQ + individuals, another frequent scapegoat of the far right, seems to have increased: in the 2005–2009 wave of World Values Survey, 58% said they would not want homosexuals as neighbours. However, in the 2017–2020 wave, this number decreased to 46%. The number of people who said homosexuality was never justifiable also decreased from 64% in 2005–2009 to 50% in 2017–2020 (“WVS Database” n.d.).

A good illustration of the rising acceptance toward LGBTQ + people is the annual Kyiv Pride. The first large-scale march took place in 2015, with 250 LGBTQ + activists and thousands of couterprotesters (Ukrayinskaya Pravda Citation2015). Since then, however, Kyiv Pride has been gathering more supporters, while far-right counterprotest has been dwindling. In 2020, the Pride march gathered around 8,000 participants, while counterprotest mobilised only around 2,000 far-right activists (Interview with Likhachev, 2021).

Overall, discursive opportunities for the far-right partially open over time. However, these opportunities played out differently in Ukraine than conventional social movement theory would suggest. Somewhat paradoxically, the war became a lost opportunity for the far right. Even though the war could have increased the acceptance of far-right actors in society, the mainstreaming and normalisation of some far-right actors and ideas was centred around the opposition to Russia and memory politics associated with OUN-UPA. At the same time, other tenets of far-right ideology, like opposition to ethnic minorities, immigrants, LGBTQ + individuals, etc., seemed less popular among political elite and the population alike. On the other hand, the acceptance of the anti-Russian agenda also sidelined the far right itself. After the onset of military conflict in 2014 and the subsequent mainstreaming of anti-Russian stances, the far right lost issue ownership.

Opportunities and mobilisation on the far-right

How can we explain the 2010–2014 peak in far-right protest and the decline afterwards? As we have seen, a combination of political and discursive opportunities offers an answer. The anti-Russian core of the far-right movement’s ideology is key to understanding its mobilisation dynamics: the puzzling peak in protest at the height of political representation was shaped by opportunities related to a pro-Russian government in power and the war with Russia.

Importantly, these opportunities played out differently than social movement theories would suggest: first, unlike in consolidated democracies where strong parties lead to weaker movements and vice versa, in hybrid regimes, far-right parties might also drive contentious politics. Indeed, there is no sharp division between radical parties engaging in electoral politics and extreme movements engaging in protest.

Second, access to formal politics may not decrease street-level violence, and conversely, lack of access may not prompt contention. In hybrid regimes like Ukraine, access does not necessarily equal influence, so even parliamentary parties may use the streets as their primary political platform.

Third, the mainstreaming of the far right can be a mixed blessing for the movement. In a peculiar context of a country at war, what could have been an important source of negative mobilisation became a lost opportunity as the increasing acceptance of the anti-Russian agenda meant loss of issue ownership by the far right. The anti-Russian position of the far right converged with the position of the mainstream in the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea. Ironically, the normalisation of nationalist views among politicians, media, and public intellectuals ended up sidelining the far right itself and decreasing the salience of its ideology, particularly its opposition to minorities.

Conclusion

This article set out to study the case of far-right mobilisation in Ukraine, focusing on protest variation over time. Its aim was threefold: first, it challenges misconceptions about the Ukrainian far right, arising from propagandist and sensationalist media coverage. Although Ukraine has been portrayed as a transnational far-right hotspot, I show that mobilisation is primarily explained by national, not transnational factors. Second, it contributes to emerging literature integrating far-right scholarship with social movement studies and addressing the electoralist bias of far-right literature, as well as the left-wing bias of social movement studies (Castelli Gattinara Citation2020). While research on opportunities for far-right mobilisation has mostly been based on consolidated democracies, the article sought to enrich our understanding of the far right in general through the case of Ukraine – a hybrid regime and a country at war – where mobilisation opportunities play out differently. Finally, the empirical contribution of the article lies in the novel protest event database, covering almost two decades of collective action. The database enables longitudinal empirical analysis, setting grounds for further research.

I find that mobilisation of the Ukrainian far right – a primarily anti-Russian movement – was shaped by opportunities related to a pro-Russian ruling elite and military conflict with Russia. This finding emphasises the importance of understanding the anti-Russian core of the movement’s ideology, overcoming popular (mis)conceptions created through Russian propaganda or sensationalist media.

The Ukrainian case has wider implications for research on the far right. As we have seen, mobilisation opportunities in hybrid regimes may play out differently than they would in consolidated democracies. To begin with, legal opportunities may not be as decisive in hybrid regimes. Political opportunities, on the other hand, play a significant role. Yet, the Ukrainian case points to the shortcomings of conceptualising opportunities primarily in terms of access. Instead, more nuance is necessary to understand the actual influence of opportunities and how they may play out beyond consolidated democracies. Similarly important are discursive opportunities; however, in a peculiar context of a country at war, the mainstreaming of far-right views can marginalise, rather than promote, the movement itself. Building on these conclusions, future research should examine what happens to far-right movements when a low-scale conflict evolves into a full-scale war – a question interesting to examine further in light of the Russian invasion in Ukraine in February 2022.

Why do mobilisation opportunities play out differently in hybrid regimes? The Ukrainian case suggests that these differences may be due to different dynamics of contention, party-movement interaction, and destabilising events. To further unpack why this may be the case and better understand the relationship between regime type or degree of democratic consolidation and the effect of opportunities on mobilisation, future research should look deeper into the mechanisms behind these divergent patterns.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Helge Blakkisrud and Jacob Aasland Ravndal for their attentive reading of, and valuable comments on, earlier drafts of this article. Special thanks also go to participants of workshops and seminars at the Center for Research on Extremism (C-REX) for their thoughtful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tamta Gelashvili

Tamta Gelashvili is a PhD candidate in political science at the University of Oslo, affiliated with the Center of Research on Extremism (C-REX). She is also a Research Fellow at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI). Her PhD project focuses on comparative analysis of far-right social movements in Georgia and Ukraine.

Notes

1 This definition excludes individual hate crime incidents, studied in detail by Likhachev (Citation2013).

2 For the purposes of this paper, pro-Russian/Slavic nationalist groups and Ukrainian branches of Russian far-right organisations, mobilising mostly in Donbas and Crimea, are excluded, since these might not be affected by the same opportunity structures. As Umland (Citation2015) argues, their mobilisation is linked more to developments inside Russia and is better understood as part of Russian nationalism studies.

3 To identify Ukrainian far-right actors, I followed a two-step process: first, I reviewed available studies on the movement, especially those that analyse ideological underpinnings in depth, to make sure that the actors identified matched the criteria defined above – ideological foundation in nativism and authoritarianism. Since the Ukrainian far right remains understudied, published works can point to some actors, mostly parties like Freedom, but may overlook smaller, or less formal groups. To make sure all relevant groups were included, I then consulted Vyacheslav Likhachev, an expert on the Ukrainian far right that has been following the movement’s activities for more than two decades. The resulting search string included far-right actors mentioned on and terms like protest, demonstration, rally, etc.

4 When an event goes over 24 h, the recommended procedure is to code it as one event if the participants stay overnight, and to code each day as a separate event if the participants leave the location and come back the next day. The 3-month-long Maidan protests in 2014, when people put up tents and stayed on the square, were thus coded as a single event. Had I coded each day separately, 2014 would have included 90 more events. This is important to clarify because far-right activity in Ukraine peaked 2010–2014, considering that the far right participated in the Maidan actively, and not 2010–2013, as it would appear from this graph.

5 Note: the last wave of this survey was conducted in 2019, so this conclusion does not reflect attitudes after the 2022 invasion.

References

- “Anti-Discrimination Legislation”. 2017. Civic Nation: Unity in Diversity, https://civic-nation.org/ukraine/government/legislation/anti-discrimination_legislation/.

- Bustikova, L. 2015. “Voting, Identity and Security Threats in Ukraine: Who Supports the Radical “Freedom” Party?” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 48 (2): 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2015.06.011.

- Bustikova, L. 2018. “The Radical Right in Eastern Europe.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Caiani, M., and D. Della Porta. 2018. “The Radical Right as Social Movement Organizations.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren.

- Caiani, M., D. Della Porta, and C. Wagemann. 2012. Mobilising on the Extreme Right: Germany, Italy, and the United States. Oxford University Press.

- Carter, E. 2018. “Right-wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.” Journal of Political Ideologies 23 (2): 157–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2018.1451227.

- Castelli Gattinara, P. 2020. “The Study of the Far-Right and Its Three E’s: Why Scholarship Must Go Beyond Eurocentrism.” Electoralism and Externalism.” French Politics 18.

- Castelli Gattinara, P., C. Froio, and A. L. P. Pirro. 2021. “Far-Right Protest Mobilisation in Europe: Grievances, Opportunities and Resources.” European Journal of Political Research.

- Coalson, R. 2014. “Putin Pledges To Protect All Ethnic Russians Anywhere. So, Where Are They?” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-ethnic-russification-baltics-kazakhstan-soviet/25328281.html.

- Colborne, M. 2020. “Dispatches from Asgardsrei: Ukraine’s Annual Neo-Nazi Music Festival." Bellingcat. January 2. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/2020/01/02/dispatches-from-asgardsrei-ukraines-annual-neo-nazi-music-festival/.

- Colborne, M. 2022. From the Fires of War: Ukraine’s Azov Movement and the Global Far Right. ibidem-Verlag.

- Diuk, N. 2014. “Finding Ukraine.” Journal of Democracy 25 (3): 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2014.0041.

- Fried, D. 2022. “Putin’s ‘Denazification’ Claim Shows He Has No Case Against Ukraine.” POLITICO. March 1. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/03/01/ukraine-russia-history-distortion-denazification-00012792.

- Gelashvili, T. 2022. “Opportunities Matter: The Evolution of Far-Right Protest in Georgia.” Europe-Asia Studies, 1–26.

- “Global Attitudes & Trends Database”. N.d. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project, Database, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/question-search/.

- Golder, M. 2016. “Far Right Parties in Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 19 (1): 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042814-012441.

- Gomza, Ivan. 2015. “Elusive Proteus on JSTOR.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 48 (2/3), https://www.jstor.org/stable/48610447?refreqid=excelsior%3A493f0a75184e402d1e438dc2863199a4&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

- Gomza, I., and J. Zajaczkowski. 2019. “Black Sun Rising: Political Opportunity Structure Perceptions and Institutionalization of the Azov Movement in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine.” Nationalities Papers 47 (5): 774–800. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2019.30.

- Gordon, A. 2020. A New Eurasian Far-Right Rising. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/new-eurasian-far-right-rising.

- Gurr, T. R. 1971. Why Men Rebel. Princeton, NJ: Center for International Studies, Princeton University.

- Harding, L. 2010. “Ukraine Extends Lease for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.” The Guardian, April 21.

- Hutter, S. 2014. “Protest Event Analysis and Its Offspring.” In Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research, edited by Della Porta. Oxford University Press.

- Hutter, S. 2014. Protesting Culture and Economics in Western Europe: New Cleavages in Left and Right Politics. Minneapolis-London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Iovenko, A. 2015. “The Ideology and Development of the Social-National Party of Ukraine, and its Transformation Into the All-Ukrainian Union “Freedom,” in 1990–2004.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 48 (2–3): 229–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2015.06.010.

- Ishchenko, V. 2011. “Fighting Fences vs Fighting Monuments: Politics of Memory and Protest Mobilization in Ukraine.” Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 19 (1–2): 369–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965156X.2011.611680.

- Ishchenko, V. 2016. “Far Right Participation in the Ukrainian Maidan Protests: An Attempt of Systematic Estimation.” European Politics and Society 17 (4): 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2016.1154646.

- Ishchenko, V. 2018. “Denial of the Obvious: Far-right in Maidan Protests and Their Danger Today” Vox Ukraine, https://voxukraine.org/en/denial-of-the-obvious-far-right-in-maidan-protests-and-their-danger-today.

- Koopmans, R. 1996. “Explaining the Rise of Racist and Extreme Right Violence in Western Europe: Grievances or Opportunities?” European Journal of Political Research 30 (2): 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1996.tb00674.x.

- Koopmans, R. 1998. “The Use of Protest Event Data in Comparative Research: Cross-National Comparability, Sampling Methods and Robustness.” In Acts of Dissent: New Developments in the Study of Protest, edited by D. Rucht, R. Koopmans, and F. Neidhart. Berlin: Edition Sigma.

- Koopmans, R. 2004. “Movements and Media: Selection Processes and Evolutionary Dynamics in the Public Sphere.” Theory and Society 33 (3/4): 367–391. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RYSO.0000038603.34963.de.

- Kudelia, S. 2018. “When Numbers Are Not Enough: The Strategic Use of Violence in Ukraine’s 2014 Revolution.” Comparative Politics 50 (4): 501–521. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041518823565623.

- Kuzio, T. 2015. “A New Framework for Understanding Nationalisms in Ukraine: Democratic Revolutions, Separatism and Russian Hybrid War.” Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 7 (1): 30–51.

- Kuzio, T. 2016. “Analysis of Current Events: Structural Impediments to Reforms in Ukraine.” Demokratizatsiya 24 (2): 131–138.

- Lawson, K., A. Römmele, and G. Karasimeonov. 1999. Cleavages, Parties, and Voters: Studies from Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. Westport, Connecticut, London: Praeger. ).

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

- Levitsky, S., and D. Ziblatt. 2018. How Democracies die. Crown.

- Likhachev, V. 2013. “Right-Wing Extremism on the Rise in Ukraine.” Russian Politics & Law 51 (5): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.2753/RUP1061-1940510503.

- Likhachev, V. 2015. “The “Right Sector” and Others: The Behavior and Role of Radical Nationalists in the Ukrainian Political Crisis of Late 2013 — Early 2014.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 48 (2): 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2015.07.003.

- Likhachev, V. 2019. Far-Right Extremism as a Threat to Ukrainian Democracy. Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/analytical-brief/2018/far-right-extremism-threat-ukrainian-democracy.

- Lucas, E. 2016. Winning the Information War. Center for European Policy Analysis. https://cepa.org/winning-the-information-war/.

- Matsiyevsky, Y. 2018. “Revolution Without Regime Change: The Evidence from the Post-Euromaidan Ukraine.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 51 (4): 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2018.11.001.

- Matthijs Bogaards. 2009. “How to Classify Hybrid Regimes? Defective Democracy and Electoral Authoritarianism.” Democratization 16 (2): 399–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340902777800.

- McAdam, D. 1982. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930–1970. University of Chicago Press.

- McAdam, D., J. McCarthy, and M. Zald. 1996. Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements: Political Opportunities, Mobilising Structures, and Cultural Framings. Cambridge University Press.

- McAdam, D., and S. Tarrow. 2018. “The Political Context of Social Movements.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, H. Kriesi, and H. J. McCammon. City: John Wiley & Sons.

- Merkl, P. H. 2003. “Stronger Than Ever.” In Right-Wing Extremism in the Twenty-First Century, edited by P. H. Merkl, and L. Weinberg. London and Portland.

- Mierzejewski-Voznyak, M. 2018. “The Radical Right in Post-Soviet Ukraine.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydgren. Oxford University Press.

- Minkenberg, M. 2017. The Radical Right in Eastern Europe: Democracy Under Siege? Frankfurt: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Minkenberg, M. 2019. “Between Party and Movement: Conceptual and Empirical Considerations of the Radical Right’s Organizational Boundaries and Mobilization Processes.” European Societies 21 (4): 463–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1494296.

- Motyka, G. 2022. From the Volhynian Massacre to Operation Vistula: The Polish-Ukrainian Conflict 1943–1947. Brill Schöningh.

- Motyl, Alexander. 2010. “Stepan Bandera: Hero of Ukraine?” Atlantic Council (Blog). March 15, 2010. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/stepan-bandera-hero-of-ukraine/.

- Mudde, C. 2010. “The Populist Radical Right: A Pathological Normalcy.” West European Politics 33 (6): 1167–1186. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2010.508901.

- Mudde, C. 2019. The Far Right Today. Polity.

- Mufti, M. 2018. “What do we Know About Hybrid Regimes After two Decades of Scholarship?” Politics and Governance 6 (2): 112–119. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v6i2.1400.

- Mutallimzada, K., and K. Steiner. 2023. “Fighters’ Motivations for Joining Extremist Groups: Investigating the Attractiveness of the Right Sector’s Volunteer Ukrainian Corps.” European Journal of International Security 8), https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2022.11.

- Pirro, A. L. 2023. “Far Right: The Significance of an Umbrella Concept.” Nations and Nationalism 29 (1): 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12860.

- Pirro, A. L., and P. Castelli Gattinara. 2018. “Movement Parties of the Far Right: The Organization and Strategies of Nativist Collective Actors*.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 23 (3): 367–383. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-23-3-367.

- Rekawek, K. 2015. “Neither ‘NATO’s Foreign Legion’ Nor the ‘Donbass International Brigades:” (Where Are All the) Foreign Fighters in Ukraine?” https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/%E2%84%96108%3A-Neither-%E2%80%9CNATO%E2%80%99s-Foreign-Legion%E2%80%9D-Nor-the-Are-Rekawek/3c722877ad02172a2bdc20c7d74b30b44227c29e.

- Risch, W. J. 2021. “Heart of Europe, Heart of Darkness: Ukraine’s Euromaidan and Its Enemies.” In The Unwanted Europeanness? Understanding Division and Inclusion in Contemporary Europe, edited by B. Radeljić, 129–158. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110684216-006

- Rossolinski-Liebe, G. 2014. Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist. ibidem Verlag.

- Rudling, P. A. 2013. The Return of the Ukrainian Far-Right: The Case of VO Svoboda. Routledge.

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2011. “The Creeping Resurgence of the Ukrainian Radical Right? The Case of the Freedom Party.” Europe-Asia Studies 63 (2), https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2011.547696.

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2015. “The Spectre of Ukrainian ‘Fascism’: Information Wars, Political Manipulation, and Reality.” European Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep21660.12

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2018. Russia and the Western Far-Right. Tango Noir: Routledge.

- Shkandrij, M. 2015. Ukrainian Nationalism: Politics, Ideology, and Literature, 1929–1956. Yale University Press.

- “Symbols of Azov (Idea of the Nation)”. 2021. Reporting Radicalism, https://reportingradicalism.org/en/hate-symbols/organizations/organization/azov-idea-of-the-nation.

- Tarrow, S. G. 2011. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge University Press.

- “Ukraine Poverty Rate 1992–2022”. 2021. Macrotrends, https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/UKR/ukraine/poverty-rate.

- “Ukraine – Unemployment Rate 1999–2020”. 2021. Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/296132/ukraine-unemployment-rate/.

- “Ukraine: Key Migration Statistics”. 2021. Migration Data Portal, https://www.migrationdataportal.org/international-data.

- Ukrayinskaya Pravda. 2015. “В Киеве радикалы напали на ‘Марш равенства’, ранили милиционера. Есть задержанные,” June 6.

- Umland, A. 2013. “A Typical Variety of European Right-Wing Radicalism?” Russian Politics & Law 51 (5): 86–95. https://doi.org/10.2753/RUP1061-1940510505.

- Umland, A. 2015. “Challenges and Promises of Comparative Research Into Post-Soviet Fascism: Methodological and Conceptual Issues in the Study of the Contemporary East European Extreme Right.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 48 (2/3): 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2015.07.002.

- Umland, A. 2020. “The Far-Right in Pre- and Post-Euromaidan Ukraine: From Ultra-Nationalist Party Politics to Ethno-Centric Uncivil Society.” Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 28 (2): 247–268.

- Umland, A., and A. Shekhovtsov. 2013. “Ultraright Party Politics in Post-Soviet Ukraine and the Puzzle of the Electoral Marginalism of Ukrainian Ultranationalists in 1994-2009.” Russian Politics & Law 51 (5): 33–58. https://doi.org/10.2753/RUP1061-1940510502.

- Volk, S., and M. Weisskircher. 2023. “Defending Democracy Against the ‘Corona Dictatorship’? Far-Right PEGIDA During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Social Movement Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2023.2171385.

- “WVS Database”. n.d. World Values Survey, Database, https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp.

Appendix

1. List of interviewees:

Bukkvoll, Tor (2022). Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, Oslo, Norway.

Gentile, Michael (2021). University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.

Likhachev, Vyacheslav (2021). Center for Civil Liberties, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Shekhovtsov, Anton (2022). University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Umland, Andreas (2021). Swedish Institute of International Affairs, Stockholm, Sweden.