ABSTRACT

The paper explains how states and international organisations interact in policy making by focusing on five countries of the post-Soviet space. Based on in-depth interviews conducted in Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan, we explore different patterns of state-IO interactions and explain the determinants of these patterns' formation. We demonstrate that these patterns arise from a combination of two country-level factors: political openness of the system and national regulation of international actors' involvement into the policy process. However, the patterns of state-IOs relations prove strongly mitigated by the intervening variable of the national reform ecosystem's configuration and resource endowment.

Introduction

It is recognised that the policy process does not occur in isolation, engaging actors as diverse as decision-makers and journalists, governmental officials and independent scholars, etc. (Freeman and Parris Stevens Citation1987; Weible, Sabatier, and McQueen Citation2009). Yet, and symptomatically, while recognising the involvement of a multitude of actors eager to influence policy outcomes, classical theories of policy process pay almost no attention to the impact international organizations (IOs), both governmental and non-governmental, have upon national policy making.Footnote1

Critical development studies (CDS) and the global governance perspective (GGP) – two major (but not exhaustive) strands of research into IO policy engagement – partly compensate for this inattention. Authors within the CDS tradition focus on the “weak” states (where the IOs’ influence proves more visible), and critically analyze the actions of a particular IO on the ground: its “recipes,” leverage with the national government, the strategies it employs to promote its policy prescriptions, and finally, the policy outcomes it produces (Molla Citation2014; Shahjahan Citation2016; Stubbs et al. Citation2017). The GGP looks at the role played by IOs in the national policy making from a different angle. It examines how policy solutions advocated by the established global/regional regimes or by the IOs influential in a particular field are then transferred and localised at a national level with the aid of international organizations (Ancker and Rechel Citation2015; Walt, Lush, and Ogden Citation2004). The locus classicus is the role the International Monetary Fund has been playing in promoting neoliberal economic and social policies across the globe (a subject also covered in CDS) (Kaiser Citation1996; but also, Kentikelenis, Stubbs, and King Citation2016). Another instance is the European Union using a versatile toolkit of external governance instruments (Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2010) to spread its policy regimes beyond its borders in areas as diverse as migration and food safety (Delcour Citation2017).

While borrowing from each of these perspectives, in this paper we break away from the compartmentalising tradition of studying particular policy domains and the actors’ constellations and patterns of interaction therein, typical of both policy studies literature and the CDS and GGP traditions. Instead, we attempt to bring the whole of a political system back in to show how characteristics of a given system and their interplay at the policy making level define the roles and functions IOs perform in the policy process; how the system accommodates them; and how the IOs work with whatever space the system leaves them with. To do that, we take a comparative approach to IOs’ involvement in the national policy process, with the national policy making scene as a unit of analysis.Footnote2 We explore the observed patterns of IO engagement as a feature of the national policy process, focusing on post-Soviet Eurasia.

The countries of the post-Soviet space present scholars with a vast variety of system-level characteristics, institutional settings, and policy outcomes (Frye Citation2012; Mandel Citation2012). The five countries that we study – Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan – also differ in the degree of IOs’ involvement into their domestic policy processes, which allows for a meaningful comparison of the differences in the patterns of interaction between the states in question and diverse IOs present in the region, and the ways IOs adapt to the different environments they are embedded in.

The paper proceeds as follows. We start by theorising the determinants of IO involvement in the national policy process. The two basic factors we expect to influence such involvement are the political system’s formal permissiveness towards the IOs and its pluralism. Their observed patterns of involvement should be mediated by the third factor of interest – the national reform ecosystem that we define broadly as the type and number of local actors available for an IO to work with, as well as the resources they are endowed with.Footnote3 We then describe our research design and the process of data collection and analysis, and classify the cases we work with according to their permissiveness and pluralism. This provides us with three clusters of cases. The analysis of the patterns of IO policy involvement within each of these three clusters follows. It is informed by the extensive fieldwork in the five countries under study. Finally, we conclude by summarising the patterns of involvement observed and relating similarities and differences in these patterns within the clusters to the three factors established in the theoretical section.

Determinants of IOs’ involvement in policy process

The role of IOs depends on where in the policy process they choose to, or are allowed to, enter, and on which grounds; which function they perform therein; and to what extent they are formally allowed to participate in the national policy process. Conceptually, all these questions lie in the theoretical focus of policy studies – a discipline studying the process of producing new policies for the society. At the same time, policy studies mostly focus on internal actors, while the influence of external actors falls into the scope of international studies which often seem to lack interest in the national policy process per se, and rather focus on the IOs’ strategies, the international regimes they create and uphold, and the national-level consequences of such regimes. This paper treats IOs as just another actor on the internal policy arena. To describe their place therein and indicate the conditions for the IOs’ involvement we shall borrow from a number of theories focusing on different stages of the policy process (Weible and Sabatier Citation2018).

The three main avenues for an IO to participate in the national policy making are the initial formulation or reform of a policy, its implementation, and its appraisal and evaluation (Brewer Citation1974; Lasswell Citation1956). The stage at which IOs enter the policy process, and even specific venues they are allowed to use, are most straightforwardly determined by the national regulation of IOs’ activity,Footnote4 which can both make IOs an integral element of the policy process (Carothers Citation1999, 157–252), or raise their operational costs and push them out or into low-level covert activity. A harshly restrictive regulation of IOs’ involvement, if implemented effectively, can exclude IOs from the policy process altogether: E.g. Turkmenistan’s policy of “positive neutrality” under Saparmurat Niyazov resulted in sealing off all foreign influences including those of IOs (Anceschi Citation2008).Footnote5

At which stage an IO manages to enter also depends on the political system’s pluralism that determines the number and configuration of “gatekeepers” in the political system (Easton Citation1965, 87–99). We expect the less pluralist political systems to prove less workable for the IOs’ involvement in the earlier stages (policy formulation and enactment),Footnote6 thus potentially pushing IOs into the later stages of the policy process where, by working with the bureaucracies and civil society groups, they could influence the policy implementation and assessment.Footnote7

The formal national regulation of foreign involvement, and political pluralism together determine the stage where an IO enters the policy process, whether it does so openly, and at which cost. We expect IOs to participate most actively in the earlier stages of the policy process in the more permissive and more pluralist political contexts, and to be present covertly and at higher cost, in the later stages of the policy process if the context is more restrictive towards international agents and less pluralist. We summarise these expectations in below.

Table 1. Formal permissiveness and pluralism as determinants of IO involvement.

These institutional features together represent the national-level political opportunity structure for IOs. Yet, at no stage in the policy process can IOs act directly. Local actors must assist with their involvement. This lack of self-sufficiency (of all policy actors only characteristic of IOs) makes availability and placement of potential local partners and their willingness to cooperate the paramount factor of IOs’ involvement. As countries differ in the type and number of local actors available for an IO to work with, so would the patterns of IOs’ involvement vary across nations.

Such local partners all act as policy entrepreneurs in the broadest meaning of the term (Kingdon Citation1984) seeking a policy change, and only engaging IOs as their potential allies. An IO could thus enter the policy process through the front door, invited by the government to help reform certain policy area (Fang and Stone Citation2012). But it could also be brought in against the will of the government – e.g. by the opposition. An IO’s involvement could even happen without the central government knowing – for instance, if it assists lower-level authorities in policy implementation, possibly seeking to reshape the policy. IOs could also team up with NGOs seeking policy change.

When these alliances are struck, they often seek complementarities in resources that their participants command (Brugha and Varvasovszky Citation2000). The three particular types of resources provided by IOs are material resources (e.g. NGO grants or financial assistance to the government); expertise (especially with IOs specializing in specific policy areas, see Herold et al. Citation2021; Littoz-Monnet Citation2017); and legitimacy – partly based on the expertise (Korneev Citation2018), and partly on reputation and prestige certain IOs enjoy (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004, 156–174; Broome Citation2008). Some IOs might also provide local actors with access to the national decision-makers in some countries.

An IO’s usefulness for the local actors should be determined by the resources at its command, but also depends on these resources’ internal supply: Where material resources, expertise, legitimacy, and political connectedness necessary for reform or active policy making are not scarce and are properly provided by the local actors, the IOs’ role would not exceed general coordination and assistance in reforms pertaining to these IOs’ jurisdiction (but see Korneev Citation2017). Lack of some of these crucial resources invites the IOs’ more intensive involvement.

The somewhat simplified generalised picture therefore entails three dimensions: (1) the IOs’ formal access to policy process and (2) the political system’s degree of pluralism, which together determine where in the policy process the IOs can enter, how easily, and on what grounds; but also (3) the structural dimension of the nation’s endowment with resources necessary to conduct reforms – mainly, the material resources and expertise, but also political connectedness for those internal actors aspiring to get engaged with reforms, and legitimacy. The resource endowment is crucial in determining the actual set of local actors willing to partner up with IOs, and the grounds for such partnership.

While the effects and interplay of the first two dimensions are straightforward, the third is more subtle. The various combinations of these factors would provide for outcomes as diverse as a resource-rich pluralistic system where IOs are formally allowed, but cannot practically participate in the policy process because their input is not valued by the local actors; and the resource-poor and politically restrictive systems where IOs cannot enter – either because their involvement is repressed, or because there are no points of entry into the policy process, or because there are no internal actors to ally with.Footnote8 In between these two extremes lies a whole continuum of possibilities whereby the IOs’ position is either enhanced by the political pluralism, or a higher demand for IOs’ involvement due to lack of internal resources to conduct reforms, or a combination of the two. Observing the interplay between these factors and the patterns of IOs’ involvement in national reform and policy process is the empirical goal of this paper.

Research design

The five countries chosen for this study are Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. The list of potential cases initially included all the countries of the former Soviet Union excluding Turkmenistan, Russia, and the Baltic states. It was then reduced to these five with a view on variation in intensity of the reform process, diversity of political conditions, and practical access to the field.

The fieldwork, conducted in May-September 2019, was organised in a series of five country trips each lasting about one week. Extensive desk research preceded each field trip. We prearranged the interviews with those experts and policy makers we had an easier access to. They also facilitated entering the field, and most of the interviews were arranged while already in the field. In every country we achieved a relatively broad coverage in terms of occupations of the informants (which included government officials, acting and retired politicians, policy experts, local NGO and IO employees, journalists, and scholars), as well as their political allegiances (supporting the government or the opposition, or not aligning with either). Occupations of the informants are summarised in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

The interviews were semi-structured and started with the common introductory part (focusing on the most recent reforms in the interviewee’s country of origin or area of expertise), followed with questions on examples of reform success and failure, and then a block of detailed questions about the reforms the informant was involved in.Footnote9 Occasionally, we asked about the reasons the reforms in question succeeded or failed, and the hurdles the reformers faced to launch and conduct their reforms.Footnote10 Interviews also included a segment where the informants were asked to reconstruct the events of a reform in question and the behaviour of all parties involved, including IOs.Footnote11 We tentatively approached the IO engagement as a potential driver of reform and a factor in policy making and implementation, while IOs were perceived as agents which could both be actively engaged in the reform and policy making process, and could contribute to the broader reform agenda in the country.

Many interviews were arranged while already in the field, involving an element of chain referral, so some would have to be conducted simultaneously. To have this flexibility a group of two or three interviewers participated in each field trip except Belarus. Sharing the individual interviewers’ observations after each day of interviews to reconstruct the field provided for an additional element of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967, 226). Every field trip was followed up by a summary note. Overall, we conducted 99 interviews, around 20 in each country. All the interviews were then transcribed and coded using ATLAS.ti software.

The five countries covered provide for eight distinguishable cases since three of them (Armenia in 2018, Georgia in 2012 and Uzbekistan in 2016) saw the change of government akin to a regime change.Footnote12 To classify these eight cases by their political openness and pluralism we use the World Bank’s Voice and Accountability score which measures “perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media” (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Citation2011, 223). For all countries the VA score is averaged for the 2010s. For the split cases (such as Armenia before and after 2018, or Uzbekistan before and after 2016) we included the dividing year only into the later period’s average. The score for Georgia under Saakashvili is averaged for 2003–2012. Extending the timeframe into the 2000s and even the 1990s for the countries where regimes did not change during these decades does not change the average VA score substantially.

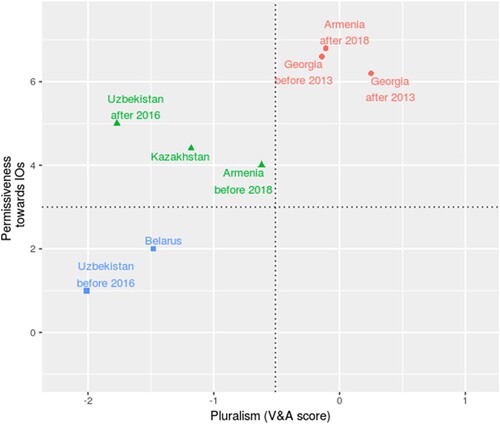

The regulation of IOs’ presence in the national policy process is harder to capture: It includes such features as existence of formal restrictions on foreign organizations operating in the country, restrictions on their incorporation under the national legislation, informal hurdles to their work, as well as the ease of entering and staying in the country for foreign nationals. Measuring these parameters and putting them into a single metric amount to creating a rigorous index of the countries’ exposure to international organizations (both governmental and INGOs) – a task far too ambitious for our study, especially since we only need that to preliminarily locate the cases relative to each other. Instead we chose to perform a “back-of-the-envelope” ranking of our cases on the degree of their restrictiveness (formal or informal) to potential IOs’ policy involvement by having all participants of the project who participated in the fieldwork rank the cases independently (whereby the most restrictive case gets one point, and the least restrictive gets eight), and then averaging the rankings.Footnote13 We have also performed a cluster analysis to group cases into categories. presents the results of this exercise.

Figure 1. Cases clustered according to permissiveness towards IO involvement and political pluralism.

The two dimensions prove correlated (r = 0.8). Unsurprisingly, international permissiveness and pluralism seem to go hand in hand, and no country in our sample combines pluralism with restrictiveness. At the same time, the cases of Armenia before 2018, Uzbekistan after 2016, and Kazakhstan constitute a separate cluster and can be classified as belonging to the non-plural permissive category – autocracies which are relatively open to international involvement in their policy process.

In the next section we, first, substantiate this preliminary classification by turning to the interviews. We observe the effect of a jurisdiction’s permissiveness and pluralism on the patterns of IOs’ involvement in the national policy process. We also check if the internal supply of the resources available in the political systems under investigation alters the outcomes for IOs, to unpack the actual patterns of IO policy involvement in different circumstances.

Testing the hypotheses

Now that we have placed the cases into categories, our empirical strategy is to test the hypotheses that: first, the commonalities between cases in terms of their pluralism and permissiveness would result in similar patterns of IO engagement, conditioning the strategies followed by IOs in terms of the openness and costs of their actual policy involvement, as well as the stage at which they enter the policy process; and second, that the variation in the patterns of IOs’ involvement within categories would stem from the varying resource endowment and the availability of internal actors willing to partner up with IOs within any given country.

Internationally restrictive non-pluralist regimes

The cases of Uzbekistan and Belarus rank the lowest in the VA score, and also appear most restrictive to international involvement in our own ranking. Our expectation is that in restrictive non-pluralist regimes the IOs’ observed participation would either be reduced to activities sanctioned by the government, and would therefore depend on the government’s actual desire to engage IOs into certain reforms, or be covert and costly, focusing on the later stages of the policy process.

Our interviews confirm pre-2016 Uzbekistan’s attribution as restrictive towards IOs. The interviewees refer to president Karimov’s policies as “rational isolationism.” Indeed, Uzbekistan under Karimov has followed the policies of mustaqillik (“self-reliance” or “self-sufficiency”) and avoided or limited all sorts of international engagement in its internal affairs (Fazendeiro Citation2017). The meagre IO policy involvement under president Karimov also readily contrasts with his successor Mirziyoyev’s significantly more open policies after 2016. The latter are even characterised as a “thaw” which brought “openness to the world to a country which was previously rather closed.”Footnote14 Another interviewee estimates that after 2016 “interactions with the international financial institutions grew not simply several times more intense, but several dozen times – measured not even in the money [attracted], but simply in the fact the government started engaging them at all.”Footnote15

The interviewees’ assessment of Belarus proves somewhat more nuanced. On the one hand, the possibilities of international involvement in the Belarusian policy process are limited, and furthermore “the state is not always friendly to donors, and [national] regulation pertaining to international grants, technical assistance and so on, is extremely and excessively demanding.”Footnote16 On the other hand, what makes the picture less clear-cut is the government’s dependence on foreign assistance. This does not show too much when such assistance comes from Russia but may result in significant elements of conditionality when assistance is provided by the West and when the government has to begrudgingly allow some international presence in its policy process.Footnote17

Indeed, the nature of these two cases’ restrictiveness is different. The international pressures present in the Eastern European countries and the Southern Caucasus often simply did not reach out to Uzbekistan. Belarus, to the contrary, by virtue of its geographic location between Russia and the rest of Europe sought to pursue the more independent international policy, and at times used its inbetweenness to its benefit by leveraging both Russia and the West (Nice Citation2012), which resulted in more openness and even certain permissiveness towards IOs. The differences observed in the IO involvement in these two cases could be attributed to these occasional openings in the Belarusian policy process due to lack of financial resources.Footnote18

Another important distinction between Uzbekistan and Belarus lies with the availability and strength of local actors, both state and non-state, who can assist international involvement by providing localised expertise and information and doing the legwork involved in the policy process, on behalf of IOs – we suggest calling this network of actors involved in policy making the reform ecosystem. In Uzbekistan this ecosystem of internal actors has remained underdeveloped throughout the Karimov years (Ubaydullaeva Citation2021). The near absence of non-state actors, as well as the unpreparedness of the state actors for reforms and cooperation with international actors, appear as one recurring theme in our Uzbekistani interviews. One interviewee mentions when talking of the Karimov years that IOs “could give you technical assistance, but whether you can take benefit of it depends on … how competent you are,”Footnote19 implying that the local actors lacked in skill and competence to take benefit of such cooperation. And indeed, it is to fill in this void that the Mirziyoyev government would launch a programme to reengage with the Uzbekistani expatriates working abroad – a development we return to in the next subsection.

Belarus, on the other hand, developed a viable ecosystem of local policy actors despite the formal restrictiveness of its legislation (Astapova et al. Citation2022). As one interviewee explains, the NGOs working in Belarus “are almost all formally registered in Poland and Lithuania” and sustain themselves through financing they get from the embassies working in Belarus – especially since “almost all embassies are willing to provide such financing.”Footnote20 Combined with stronger international leverage through conditionality, and with existence of an actual reform agenda (effectively absent in Uzbekistan under Karimov), this resulted in a more efficient and visible IO involvement in Belarus, even though such involvement still very strongly depends on the government’s goodwill.Footnote21

This combination of favourable factors occasionally results in patterns of interaction between IOs and the local actors which normally only arise under the more pluralist and permissive political circumstances (e.g. in Armenia and Georgia). In particular, the Belarusian NGOs get to influence the policy process that they are effectively cut off from by the government, whenever an IO allowed into the process contacts them for their expertise (which happens “quite often”Footnote22). The NGOs channel their initiatives through the IOs involved (such as the IMF or the World Bank) by getting these initiatives included into the IOs’ recommendations. In the end, they sometimes resurface in the government’s policies.Footnote23 In Uzbekistan, we did not come across situations like that, partly because of the poorer development of the local nongovernmental actors.

Curiously, even in Uzbekistan under Karimov the IOs’ engagement was not limited to responding to the requests by the government, as the IOs pursued outreach activities aimed at providing the lower-level officials with policy solutions that they could use if a reform were launched. An interviewee notices how the official plans for road and infrastructural development prepared by the city authorities of Tashkent, the capital city of Uzbekistan, in 2019 “were exactly the same” with the documentation provided by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) around 2014, under Karimov:Footnote24 Not only the IO penetration on different levels of government is not that low, even in restrictive regimes like Uzbekistan, but the officials also respond to IOs’ demands and accommodate them.

Internationally permissive non-pluralist regimes

After Karimov’s death in 2016 Uzbekistan undergoes a mild liberalisation and, following a radical change in its foreign policy orientations under Mirziyoyev, joins the group of countries which we classify as internationally permissive non-pluralist regimes. The two other cases within this cluster are Armenia before the 2018 Velvet revolution, and Kazakhstan – both authoritarian states which nevertheless pursued consistently more permissive policies towards IOs. With this group we expect to observe the IOs’ more overt participation in the later stages of the policy process, and their generally more active involvement. Overall, our interviews confirm this expectation.

In Uzbekistan after 2016 the main driver of such involvement proves the government’s strong orientation on international rankings.Footnote25 The new president issued a decree listing the indices of interest (such as the Corruption Perception Index or Doing Business ranking), as well as the bodies and agencies charged with scoring better at these rankings. As one interviewee observes, this gave the IOs compiling those indices (such as the World Bank, for instance) a stronger indirect influenceFootnote26 on Uzbekistani home policies that would now have to be specifically tailored to look better in the indices’ methodologies.Footnote27

This new fixation on the indices was motivated by the wish to “change the international perception of Uzbekistan which formed under Karimov” (an interviewee characterises it candidly as “somewhat negative”) rather than the need for financial assistance.Footnote28 The resource that Mirziyoyev, the architect of this new openness craved is therefore primarily legitimacy. However, to improve its standing in international rankings, Uzbekistan would also need expertise – a resource that, too, proves in short supply after Karimov’s rule. To make up for this shortage the Mirziyoyev government “started engaging the [foreign] institutions [in the reform process directly]: the Asian [Development] Bank prepares privatisation; the European [Reconstruction and Development] Bank drafts the program on oil, gas, and chemical industry … ; BCG, the World Bank, Asian Bank, Islamic Bank are all given some sectoral tasks.”Footnote29 Meantime, the new government also seeks to make up for the internal shortage of expertise by putting foreign experts in charge of specific reforms, as well as repatriating Uzbekistani policy experts based abroad and hiring them as high ranking officials at the ministries and as experts of the Buyuk Kelajak expert council – a newly established quasi-NGO drafting the all-embracing programme of political and economic reforms for Uzbekistan till 2035.Footnote30

None of these measures seem to contribute to developing Uzbekistan’s own internal reform ecosystem though. The non-state actors, while not specifically barred from entering the policy field, are simply non-existent since it remains “rather difficult to register an NGO.”Footnote31 As a result, the IOs, now engaged much more intensely, cooperate almost exclusively with the state officials (who now “perceive such cooperation significantly more positively”Footnote32).

Here lies the main difference with the otherwise very similar case of Kazakhstan, where such pattern of IO involvement has existed at least since the then president Nazarbayev proclaimed the goal of making Kazakhstan one of the world’s 30 most developed economies, in 2012. Following this pattern, the government engages with reputable IOs (such as the World Bank, OECD, or UNICEF) that endow the government-sponsored reforms with legitimacy and supply their expertise. Unlike Uzbekistan, however, Kazakhstan sports a significantly more developed and diverse reform ecosystem:Footnote33 Apart from the state officials, who command sufficient expertise of their own and still play the central role in the reform process, there are also NGOs, civic activists and independent experts that IOs and the government can interact with (Knox and Yessimova Citation2015; but see Nezhina and Ibrayeva Citation2013). This influences the way IOs are involved in the policy process quite visibly.

Five specific patterns arise. The first (also observed in Belarus) is IOs commissioning “shadow reports” from local NGOs and activists to keep track of the pace and direction of the reform. This also allows the NGOs to have their voices heard and even amplified when IOs incorporate their findings into recommendations for the government. Furthermore, IOs encourage the government officials to cooperate with local activists directly, and to create forums for activists to articulate their positions thus anticipating the criticism the government would otherwise hear from the IOs.

Officials also use the expertise supplied by IOs and local NGOs as a source of inspiration for the reforms they promote. This is especially the case when officials need to come up with a reform proposal urgently following an internal shock. The time-strapped officials often have no solution of their own in store, and just use the materials prepared by IOs or local NGOs beforehand and supplied at the spot. An important feature of Kazakhstan in this respect is that the president is incessantly adopting new national development programmes, with a detailed section covering each major policy area. Ministries have to submit their contributions almost on a yearly basis, and on some occasions rely heavily on ideas and expertise supplied by the local branches of IOs and local NGOs, almost as a matter of symbiosis with them.

A different form of symbiosis arises when a high-ranking official proactively takes an IO or NGO-promoted initiative under their wing for further development. The penitentiary reform launched in 2013 is a good illustration: Campaign to reduce prison population was initiated in 2011 by a group of Kazakhstani lawyers affiliated with the Penal Reform International (PRI). In 2012 the newly appointed Deputy Prosecutor General Zhakyp Asanov approached one of these lawyers and suggested they work together. As part of this work, Kazakhstan held a series of high-profile international Prison forums in 2013–2017 and conducted a complex reform of the penal procedure, reducing the prison population from 50,000 to about 35,000. Effectively, Asanov put together the expertise developed by locally based but internationally affiliated experts, the international dimension provided by the IOs such as the OSCE and the EU, and his own political and managerial skills. In turn, improving Kazakhstan’s standing in international rankings contributed to Asanov’s promotion to Prosecutor General, and then to Supreme Court chairman.

The lower-level officials also engage with IOs to overcome internal resistance to their proposals. This both “gives [the proposal] more weight and has some practical value.” Thus, national agencies sometimes ask international experts (e.g. from the OECD) to feature specific policies in their recommendations, because otherwise “the government won’t hear them.”Footnote34 An interviewee’s department devised an e-governance mechanism they thought could be blocked by the other ministries, so they asked an international agency they worked with to present this model as the “global best practice” instead.Footnote35

These complex forms of cooperation stem from high demand for reform combined with uneven resource endowment and low political throughput capacity. Closedness and centralisation make Kazakhstani policy process seem like a toll road with only one tollbooth opening occasionally. To get through, various actors within the ecosystem have to pool their resources together. This involves forms of carpooling, seeking bypasses, as well as a lot of “honking” to be noticed at the tollbooth.

Compare that to the case of pre-2018 Armenia. With a relatively well-developed reform ecosystem (Stefes and Paturyan Citation2021), it also featured a complete lack of political will to engage in reforms. The Armenian “tollbooth” was closed: partly because of the Nagorno-Karabakh military conflict with Azerbaijan and the country’s strong orientation towards Russia and away from other international influences (that could incentivize the government to launch reforms)Footnote36 – as an interviewee puts it, “Karabakh is the main handicap of reform;”Footnote37 but also partly because the government chose to strategically postpone all reforms until after the constitutional reform would enter into force in spring 2018.Footnote38

Absent any reform agenda, all the actors involved or potentially interested in reforms were stalling. The IOs involvement is still instrumentalized by internal actors: e.g. the civil society activists would have IOs list certain measures as prerequisites for providing financial assistance, thus putting pressure on the government indirectly. The authorities, too, would frame unpopular initiatives as imposed by IOs.Footnote39 But the actual function IOs perform is different, and interviewees consistently characterise them as donors of financial and other resources used by the internal actors in their own interests, rather than for reform. The IO representatives, too, fully understand that the government only engages in reforms “to save face.”Footnote40

Under these conditions, all an IO could do was to push the government closer to formulating a policy program (authored by the governmental officials with the use of expertise supplied by local NGOs), with no clear perspectives of enactment. Thus, contrary to our expectation, the IOs’ influence in pre-2018 Armenia only covered the agenda-setting stage, and mostly failed to extend into the later stages of the policy process.Footnote41

Internationally permissive pluralist regimes

The 2018 revolution moves Armenia into the category of internationally permissive pluralist regimes. In this group the IOs’ participation should be most open and active and embrace all stages of the policy process. The revolution also ended the pre-2018 stalling abruptly, creating an opening for reforms. At the same time, all reform plans carefully drafted and stored in anticipation of the 2018 constitutional transition were now put aside, and even disposed of.

Strikingly, after the revolution the overall structure and logic of the policy process does not change. Other than the prime minister now replacing the president as the key political figure, the ecosystem remained the same. Ministers remain initiators of policy change in their sphere of responsibility. Their deputies and heads of departments, together with local NGOs, provide policy expertise.Footnote42 The place of IOs did not change either: they are still expected to simply finance those policy programs which would be written, adopted, and implemented by local actors.

An illustrative example is the program of development in the sphere of school education, launched before the revolution and then restarted after it. Financial assistance to design the program was provided by the Asian Development Bank that traditionally contributes to the sphere of social infrastructure in Armenia. Together with the Ministry of Education, the ADB formulated the call to hire local experts and selected them. Then, the Ministry coordinated the work of those experts to get a draft policy program, and then transferred it to the political level – to the Minister, the Prime Minister, and the Parliament. When the program is approved, the government would negotiate with the donor organizations once again – this time to get implementation funding.

Given the IOs’ detachment, the local experts remain quite critical of their role in Armenia’s reform process even after the revolution. Their collaboration with the government produces poor results, and their involvement is perceived as perfunctory and easily misguided by the authorities. As one interviewee puts it, in this relationship “the ball is always in the government’s court.”Footnote43

Our field trip to Armenia took place in June 2019, only one year after the revolution, which partly explains why we did not observe any significant changes to the IO engagement in Armenia after 2018.Footnote44 Another explanation though lies with the lack of changes in the national political process: following the revolution, the revolutionary forces had obtained a monopoly of power which was further consolidated after the landslide victory in the 2018 parliamentary elections. The reform ecosystem did not change either, resulting in almost no adjustments to the policy process.

The two other cases populating the internationally permissive pluralist cluster are those of Georgia before and after 2013. In fact, Georgia is the only country in the sample consistently characterised as an internationally permissive pluralist regime. Since the Rose Revolution that brought Mikheil Saakashvili to presidentship in 2003, Georgia has always scored high in the VA index, but especially so after the change of power in 2012–2013 when the Georgian Dream coalition led by Bidzina Ivanishvili, the wealthiest man in the country, won the parliamentary elections and outnumbered the MPs elected on Saakashvili’s then ruling United National Movement (UNM) ticket.

Given Georgia’s position in the upper right corner of the graph (), we expect that both before and after 2013 IOs would openly participate in all stages of the policy process, including the most lucrative ones of policy formulation and adoption, and that in general, their involvement with the national policy making process under Saakashvili and Ivanishvili would be rather similar.

In reality, however, the two cases prove quite different. Indeed, the very dynamic of policy making under the two governments turns out to differ substantially. One interviewee describes decision making under Saakashvili as “unilateral,” not involving any consultations, and unfolding “in a very close-knit circle … of seven guys charged … with policy goal formulation, decision taking and, then, enforcement:” very much goal-oriented and not process-oriented at all.Footnote45 This approach would obviously leave little space for any non-governmental actors, both local and international, to participate in the actual policy process (see also Kakachia and Lebanidze Citation2016, 140).

Initially, what distinguished IOs in their ability to get involved with the government was the type of resources they possessed. Although Saakashvili was from the outset not interested in additional legitimacy boost or any outside expertise,Footnote46 he still needed financial support in the first years of his rule. There even was a competition between the government and the NGOs for international support initially, and Saakashvili had to convince the donors that “the best part of the civil society is [now] in the government,” and that therefore “now most of the money should come to the government”Footnote47 (see also Muskhelishvili and Jorjoliani Citation2012, 695).

This changed after the government “learned how to raise money from taxes,”Footnote48 from “selling state property,”Footnote49 or forcing businesses to finance governmental initiatives (e.g. building the so called “Houses of justice,” part of Saakashvili’s single-window administrative reform).Footnote50 When that happened, “they relied on the donors much less”Footnote51 compared to what had been happening immediately after the Rose Revolution.

The government also “stopped listening to the donors […] because of the competence that their people had.”Footnote52 The Rose Revolution brought a lot of new blood into the system (Nodia Citation2005), and Saakashvili pinned his hopes on the very young generation of Georgians, preferably with Western education, whom he often hand-picked “spontaneously.”Footnote53 Often these new recruits had experience of working for the Georgian-based INGOs, like the Open Society Foundation, or intergovernmental international organizations, like the OSCE or UNDP. These active young professionals, eager and able to use their skills and international connections to raise money in order to push forward their policy initiatives, ended up in the government (Broers Citation2005; Cheterian Citation2008, 699).Footnote54 And while they would often depend on some financial support from the West to implement these initiatives, the ownership they felt about their pet projects and their expertise did produce a paradoxical effect of generally lowering the actual leverage IOs had with the government.

With the high level of popular support and legitimacy, internal expertise, a clearly articulated vision for a small libertarian government, and sufficient financial resources, Saakashvili’s regime had little practical interest in engaging with IOs on their terms.Footnote55 Open to the West, having “concrete ambitions” to join the EU and NATO,Footnote56 and willing to “constantly blink on the radars of international organizations and big countries,”Footnote57 Georgia under Saakashvili had, of course, to listen to the most important IOs, but at the same time, as it turns out, the government could still afford keeping the policy process rather isolated from the direct command of international actors.

Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream – the political force that came to crush the Saakashvili regime – is widely recognised as “an ‘anti’ movement, united not by policy positions or constituencies but by disgust with the government” and with Saakashvili personally (Fairbanks Jr and Gugushvili 2013, 119). Symptomatically, Ivanishvili’s rule is also the opposite of the Saakashvili regime in terms of its policy making process. The adjectives our interviewees use to describe it include: “incremental,” “slow,” “cautious,” “ain’t-broke-don’t-fix-it,” “risk-averse,” “easily rolled back,” “ideology-free,” “oligarchic,” “unofficial.” All of that is combined with the lack of transparency and enormous uncertainty pertaining to the way decisions are taken: As one interviewee puts it, Ivanishvili’s governance is “totally opaque and nobody knows … how it works really.”Footnote58 This uncertainty creates

a problem of making decisions: people in the government are afraid to assume responsibility … , and they wait for Ivanishvili to make decisions, and either … cannot get in touch with him … , or he cannot make up his mind, but you see that they cannot make decisions.Footnote59

The most obvious form of such partnership is the IOs’ financing of the local civil society organizations’ projects aimed at reforming some particular policies at the national level. Foreign aid to the NGO sector starts to grow already after 2007–2008.Footnote60 But coupled with the change of power in 2012–2013 and the subsequent mushrooming of diverse working groups and other consultative venues under the auspices of the government and in the parliament, it resulted in the local NGOs’ extensive involvement in policy design, with a twin goal of ensuring “that the proposed laws and policies, on the one hand, comply with the international best practices … , and also that they … reflect the current realities of the country … : that the situation on the ground is taken [into account].”Footnote61

This aspiration to localise (or “georgianize”) international policy recipes sometimes produces tensions between local actors and IOs.Footnote62 However, generally the IOs and NGOs work in symbiosis, producing another pattern of IO involvement (also observable in the internationally restrictive and permissive non-pluralist regimes, but curiously not in Saakashvili’s Georgia) – when civil society organizations or the opposition or the media, whenever ignored by the authorities, bring IOs in to put international pressure on the national government. (For instance, the NGOs involved in judicial reform, while cooperating with the Venice Commission directly, would also often demand that the Speaker of the Parliament requests the Commission’s opinion about new legislation that they contest.)

A reverse pattern also exists when IOs commission the NGOs, either openly or covertly, to prepare the “shadow reports” on Georgia’s compliance with its international commitments. Positions and recommendations from the shadow reports then pop up on the pages of the organization’s own country reports – this is the case with the OECD, and even more so with the European Union after signing of the Association Agreement with Georgia.

Sometimes a shadow report is not enough to ensure that the government delivers on its commitments. This makes IOs turn to more covert instruments at the later stages of the policy process. E.g. given Georgia’s “conservative” public opinion regarding the LGBTQ + rights and active local resistance to legislative changes in this domain propelled by the ever authoritative Georgian Orthodox Church (Shevtsova Citation2023), along with attempts to influence policy makers when they adopt laws, IOs try to influence the outcomes at the implementation stage by engaging the police, investigators, prosecutors, and other street-level bureaucrats in trainings, seminars and other activities in an attempt to socialise them into a more accepting culture.Footnote63

Many interviewees believe the overall openness of the policy process under Ivanishvili and a broader involvement of NGOs and IOs in reforms stems from the lack of independently earned popular support. As the Georgian Dream coalition has come to power as “an ‘anti’ movement,” it is doomed to gain support and legitimacy not from its own agenda but mostly by contrasting itself with Saakashvili, his closed non-deliberative decision-making style included.

At the same time, when conducting an unpopular or technical reform, and engaging IOs for their expertise and financial assistance, the government often tries to avoid broader consultations with the local actors, sometimes dealing with international experts behind closed doors, without publicising their involvement. This was the case with the 2018 pension reform aimed at infusing “long money” into the financial sector of the Georgian economy which only involved international experts and a limited number of local consultants hired by the donor organizations and functioning as a bridge between the donors and the Ministries of Economy and Finance. Similar strategy was used during the 2015 civil service reform: Even the NGOs active in this particular policy area had little idea of how governmental representatives worked with international consultants at the policy design stage.

Georgia thus has transitioned from a very uniform pattern whereby the IOs’ interactions were centered on the government officials, under Saakashvili, and IOs did not have much substantive leverage over the policy outcomes, to a whole multitude of patterns of interaction invoked by the IOs under Ivanishvili, directed at different actors across the political system and involving exchange of a variety of resources.

Conclusion

We observe a wide variety of patterns of IO involvement into reform and policy process in the five post-Soviet states. These patterns include: IOs commissioning information from local NGOs in the form of the shadow reports; NGOs using IOs allowed into the policy process to make the government hear their demands; IOs, NGOs and lower-level state bureaucracies striking alliances to achieve their specific policy goals at the implementation stage; governments using the internationally connected NGOs to finance their reforms; higher-level bureaucrats using IOs to promote their agenda and make the reforms they conduct more visible for the politicians; and even everybody imitating a reform process when it is known that the reform would not be conducted due to political reasons (as in the case of Armenia before 2018).

Our empirical analysis shows that even within the permissive pluralist systems patterns of IO involvement can differ substantially. The degree of IOs’ involvement is very much mitigated by the resource endowment in any given country (as the governments appear more or less dependent on resources supplied externally), and by how developed the local policy making ecosystem is (thus providing IOs with natural allies to partner up with).

The case of Georgia under Ivanishvili is probably the most extreme example of an IO-friendly and pluralist regime which provides IOs with multitude of potential forms of engagement – due to the sufficiently well-developed ecosystem of local actors involved in policymaking. Compare that to the case of Uzbekistan under Karimov, with its effectively non-existent ecosystem of policy actors and lack of local resources to sustain one. The two cases are also contrasted in the intensity of the policy process therein: Even if the Karimov regime would be getting more resources from IOs, there would be no policy process to invest these resources into. (The case of pre-2018 Armenia is instructive in this respect.) And conversely there is an ongoing policy process in different areas that could make use of additional resources (and actors to take benefit of these) in the Ivanishvili regime.

As expected, it is not only the two formal institutional dimensions of pluralism and permissiveness that determine the level and patterns of IO involvement in the policy process. It is also the structural dimension of resource endowment and the actual policy ecosystem that can take benefit of these resources, and that creates additional demand for external resources to be supplied. Furthermore, these three dimensions exist in interaction: Lack of internal resources would often force the government to let IOs into the policy process. More IO engagement leads (through conditionality and network governance) to the intensification of the policy process. That, in turn, boosts the policy ecosystem, if there is any ecosystem to start with, and unless the government puts additional effort in suppressing it. With only moderate resource endowment, all of that results in a more intensive policy process, and in higher and more variegated IO involvement therein.

Supplemental Table

Download MS Word (27.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE University). The collection of the empirical data was financed by a generous grant of the Center for Advanced Governance. We are thankful to Mikhail Komin and Kirill Kazantsev for their extensive participation in collecting the data used in this paper, and to Sonia Gubaydullina and Denis Stremoukhov for their research assistance. We would also like to thank the participants of the regular colloquium of the Global Governance unit at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center that took place on February 16, 2023, and in particular, Michael Zürn and Christian Rauh. Their thoughtful suggestions helped to improve the paper at the revision stage as did the comments provided by the anonymous reviewers, whom we are also thankful to.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna A. Dekalchuk

Anna A. Dekalchuk is Senior Lecturer in Critical Area Studies, CEES, School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow.

Ivan S. Grigoriev

Ivan S. Grigoriev is Lecturer in Russian Politics at King's Russia Institute (King's College London).

Andrey Starodubtsev

Andrey Starodubtsev is Associate Professor at the Department of Political Science and International Affairs, HSE University in St. Petersburg.

Notes

1 A review of some of the most influential handbooks on policy process reveals that IOs are almost never mentioned in the policy studies literature (see John Citation2012; Moran, Rein, and Goodin Citation2008; Weible and Sabatier Citation2018). Cerny (Citation2001) was among the first to raise this issue, but even twenty years later Ashley, Kim, and Lambright (Citation2020, 11) still urge the public administration scholars “to scale up the lens of inquiry beyond the nation-state to include global governance actors and organisations,” and Legrand and Stone (Citation2021) in their very recent review of interchanges between the public policy studies and international political economy still show that “the development of these … fields of study … has been commensurate but rarely intersecting” (Legrand and Stone Citation2021, 481). This is not to say that there is no research into the IOs’ influence on the national reform process (see, e.g., Broome, Homolar, and Kranke Citation2018; Fang and Stone Citation2012; Herold et al. Citation2021), but that almost all of it lies outside the subdiscipline of public policy studies.

2 A good alternative research strategy would be to focus on a specific IO and take the IO’s performance across different national contexts as a starting point for comparative enquiry into the factors that influence the IO’s presence in the national policy making. The strongest advantage of such approach is an element of Most Similar Systems (MSS) Design where the IO chosen for analysis would be expected to pursue similar strategies in, and seek the same outcomes for, the countries it works in, so that the observed differences in the IO’s presence could be ascribed to country-level factors. It has been shown, however, that IOs are strategic about the kind of presence they seek to exercise depending on various country-level factors (Dietrich Citation2013; Schlaufer Citation2019; Winters Citation2010), which significantly reduces applicability of the MSS design. At the same time, focusing on the country level instead and theorizing the patterns of IO engagement observed in each individual country case (rather than strategies employed by the IOs across the board) helps avoid this problem. Even where specific IOs are adapting their strategies of presence in different countries for idiosyncratic or strategic reasons, the overall patterns of engagement by all IOs observed in any given country would still constitute a systematic phenomenon.

3 We do not imply that all actors involved in the reform ecosystem necessarily focus primarily (or at all) on reform or have a specific reform agenda. Rather, they either have some valuable resources that can be used to produce reform, or have access to decision making, and therefore can take part in reform making even if their immediate objectives are different (e.g., journalists covering a particular policy area may not want to promote reform in this area but might end up contributing to such reform).

4 Similarly, the NGO or political parties’ involvement is regulated by the (more or less restrictive) national legislation, as well as the role of the media, the experts, or the courts.

5 For the purposes of this paper, we assume that the regulation of IOs’ activity and engagement in the policy making process is uniform across policy areas. Our choice of the unit of analysis necessitates this simplifying assumption. Importantly, this assumption holds for the purposes of this research that did not include what might be labeled as political constitutional reforms, and focused mostly on social and economic policy areas – a point we return to in the Research Design section below. This assumption needs to be relaxed if the politically more sensitive policy areas (that might be regulated more strictly) are analyzed.

6 Entering the policy process in its earlier stages (agenda setting, policy promotion, and enactment) is preferrable because it gives a stronger leverage in promoting specific policy proposals. As Schattschneider (Citation1960; quoted in Mair Citation1997, 947) puts it, “the definition of the alternatives is the supreme instrument of power.”

7 The number of gatekeepers in the political system has been theorized by Tsebelis (Citation2002) as reducing the range of potential policy change – and, as a result, as limiting the opportunity for policy intervention by all actors, including international organizations. (In his theory Tsebelis talks more specifically of “veto-players” who can halt reform that does not lie within their policy preferences.) Note that the higher number of gatekeepers should not be seen as only reducing the range of policy change though: it is often overlooked both in the comparative politics and in the policy studies literatures that the fewer gatekeepers also mean fewer opportunities for societal actors to add items to the reform agenda (even where the veto-players could then block their further promotion and enactment into policies). This is especially true since Easton’s gatekeepers are not always Tsebelis’s veto-players: they do not necessarily have the power to block reforms, but only regulate access into the black box of political system – hence our choice of terms.

8 That such dramatic diversity in conditions can result in essentially the same outcome where IOs remain off limits in the national policy process is a striking example of equifinality (Bennett and Elman Citation2006; Braumoeller Citation2003).

9 We sought to take advantage of the semi-structured format of the interviews and asked about reforms in general, without specifically defining what constituted a proper reform, and thus leaving it to the interviewees to define how big (and what kind of) a policy change would qualify for a reform in their opinion. This was critical for our cross-national design since some of the country cases on our sample proved systematically less prone to full-scale reform than others. As a result, by narrowing the understanding of reform to anything more specific we could possibly direct the interviewees, whereas our goal was to prompt them to share their impression of the policy process in their respective countries, without restricting them by the normative considerations of what is and is not a proper reform. On a linguistic note, we preferred the word “reform” and opted against asking about “policy change” instead since most interviews were conducted in Russian and the Russian analogue (изменение политического курса) is clumsy and non-intuitive.

10 Given this focus on reformers’ experiences, the interviews ended up effectively leaving out of the scope of this research what could be called political constitutional reforms (such as those under way in the 2010s in Armenia, Georgia, and Kazakhstan) that aim to change “the basic patterns of power distribution and reproduction” (Golosov Citation2013, 618) in the political system.

11 Similar to our approach to types and degrees of reform (see note 8 above), during the interviews we did not narrow the IOs to governmental or non-governmental. Nor did we limit the list of policy areas those organizations could engage in.

12 A potential transition also started in Kazakhstan in early 2019, only months before our field trip. The changes which followed fall out of our timeframe, and we treat Kazakhstan in the 2010s as a single case.

13 The individual rankings are presented in Table S2 of the Supplementary Material.

14 High-profile UN official in Uzbekistan, Tashkent, June 15th, 2019. Here and below, we use footnotes to provide information about the interviewees that are quoted directly. An attempt was made to triangulate all such statements in other interviews and secondary sources. The additional information is intended for the reader to assess if the interviewee could be biased.

15 Uzbekistani public administration expert, Tashkent, June 13th, 2019.

16 Head of national business association, Minsk, September 11th, 2019.

17 Most recently that has been the case after 2014–2015 when the government had to negotiate a helpline with the IMF. An interviewee (then a member of the National Bank’s advisory board) mentions that these negotiations had become the major driver behind the central bank reform that, following the IMF recommendation, made the Belarusian National Bank an independent body exercising conservative monetary policies.

18 Opportunities for international financial institutions to enter Uzbekistan under Karimov also occasionally arose, but mostly materialized in the form of loans for infrastructural projects. One IO our interviewees single out is the Asian Development Bank (ADB) which backed several projects under Karimov. Importantly, its financial support came without any strings of conditionality attached: “the ADB’s policy often is: [we are okay with] whatever [the government] says, all we want is to come through with the project” (Official at IO representation in Uzbekistan, Tashkent, June 11th, 2019).

19 Uzbekistani official, Tashkent, June 11th, 2019.

20 Belarusian legal expert, Minsk, August 21th, 2019.

21 This changes after the 2020 protests as the government becomes extremely hostile to NGOs and civil society groups (Astapova et al. Citation2022).

22 Head of national business association, Minsk, September 11th, 2019.

23 Campaign to promote the Anti-Discrimination Act in Belarus launched in 2018 by the Belarusian Helsinki Group is one example. An NGO activist behind it traces its appearance in the National Plan for Human Rights to its inclusion into the UN and the Council of Europe’s country reports upon requests from a wide coalition of civic-minded NGOs pushing for reform.

24 Uzbekistani official, Tashkent, June 11th, 2019.

25 In fact, the policy towards international rankings started changing gradually already in 2011–2012 as it went from complete rejection of all indices (as our interviewee, an Uzbekistani administrative law expert puts it, “one was not allowed to even mention those [hostile] indices because Uzbekistan ranked so low, close to Turkmenistan, North Korea and such – which was, of course, offensive”) to “analyzing the state regulation through the prism of the Doing Business index,” (Uzbekistani expert in administrative law, Tashkent, June 10th, 2019) as the president instructed the state bureaucracy in his new decree.

26 Broome, Homolar, and Kranke (Citation2018) theorize this as the IOs’ “indirect power.”

27 Uzbekistani official, Tashkent, June 11th, 2019.

28 Uzbekistani expert in administrative law, Tashkent, June 10th, 2019.

29 Official at IO representation in Uzbekistan, Tashkent, June 11th, 2019. Ubaydullaeva (Citation2021) talks of “early signs of the emergence of civil society groups.”

30 One interviewee – himself an Uzbekistani professional who previously worked in Russia but was reengaged after 2016 to participate in the reform process – frames it as the new president’s personal initiative that he launched after visiting the US, noticing how many Uzbeks with relevant professional experience work abroad, “and inviting them to work for the motherland” (Top-level Uzbekistani official, Tashkent, June 10th, 2019).

31 Official at IO representation in Uzbekistan, Tashkent, June 7th, 2019.

32 Uzbekistani official, Tashkent, June 11th, 2019.

33 The single most important reason for that is the Kazakhstani programme of financing study abroad for its citizens, but also returning them back to Kazakhstan, called Bolashak (but also see Kaiser and Beimenbetov Citation2020).

34 Kazakhstani top-level official, Nur-Sultan, May 19th, 2019.

35 Kazakhstani public administration expert working with IOs, Nur-Sultan, May 14th, 2019.

36 Russian support for Armenia in the conflict worked as a guarantee of its international security. Dependency on Russia resulted in refusal to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union in 2013 and subsequent accession into the Eurasian Economic Union in 2015.

37 Top-level IO representation official in Armenia, Yerevan, June 25th, 2019.

38 The main feature of the planned constitutional reform was transition towards parliamentary system and a “demotion” of the then president Sargsian (whose second presidential term would expire in 2018) to a prime minister.

39 “The government goes to the parliament and says [that] something is an IMF requirement – but in fact the IMF does not require that” (High-ranking official in Karapetyan administration, Yerevan, June 27th, 2019).

40 Top-level IO representation official in Armenia, Yerevan, June 25th, 2019.

41 “They [a UN office] write documents, but when it comes to real things, they do not really look at them” (Armenian MP, Yerevan, June 27th, 2019).

42 After the revolution, this bond grew stronger as NGO activists were drawn into the government as deputy ministers — precisely for their expertise.

43 Armenian NGO activist, Yerevan, June 27th, 2019.

44 In the years following the Velvet Revolution the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict intensified again and, presumably, started to play a similarly debilitating role in the Armenian reform process.

45 “It worked like that: ‘We think that this has to be done like this – here is a fait accompli’” (High-ranking official in the Ivanishvili administration, Tbilisi, June 17th, 2019; also see Mitchell Citation2012).

46 An interviewee who worked with Saakashvili says that “he did not have a high opinion of civil society – he had an opinion about specific persons in the civil society. But civil society … he never took it seriously. And civil society people were very offended by that” (Top-level official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 21st, 2019).

47 Top-level official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 21st, 2019.

48 Top-level official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 21st, 2019.

49 High-profile official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 19th, 2019.

50 Head of a major Georgian NGO, Tbilisi, June 18th, 2019.

51 Independent Georgian consultant working with diverse IOs, Tbilisi, June 20th, 2019.

52 Independent Georgian consultant working with diverse IOs, Tbilisi, June 20th, 2019.

53 An interviewee describes that Saakashvili hired officials after meeting them “on the plane” (Top-level official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 21st, 2019).

54 Compare this to Mirziyoyev’s Buyuk Kelajak policy in Uzbekistan after 2016 (see above).

55 This is how Saakashvili spoke of IOs’ terms and conditions in the later period of his rule: “Time, which we have spent on construction of new homes for IDPs, would have been only enough for the international organizations for their paper work” (“Saakashvili Delivers State of Nation Address” Citation2009).

56 Top-level official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 18th, 2019.

57 High-profile official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 19th, 2019.

58 Top-level official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 21st, 2019.

59 Official at the Georgian branch of an international NGO, Tbilisi, June 17th, 2019.

60 Some believe the fault line lies with the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. Others say it was after the November 2007 Rustaveli Avenue protests and the ensuing police brutality that “the donors again became more looking at the civil society … to balance the government.” (Top-level official in the Saakashvili administration, Tbilisi, June 21st, 2019; Official at the Georgian branch of an international NGO, Tbilisi, June 17th, 2019; Georgian journalist, Tbilisi, June 15th, 2019).

61 Official at the Georgian branch of an international NGO, Tbilisi, June 17th, 2019.

62 E.g., some recommendations provided by the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe regarding the long-lasting judicial reform and the overall positive assessment of the reform progress in the EU Association Implementation reports have been met with a lot of criticism by the NGOs active in this policy field, who point at the international partners’ lack of local knowledge and understanding of the political context, their retrospective approach (when they evaluate the current realities against the judiciary’s performance under Saakashvili), as well as the fact “they do not want to alienate the Georgian government too much, because Georgia still performs better than Ukraine or Moldova – the two other countries in the group” (Official at the Georgian branch of an international NGO, Tbilisi, June 17th, 2019).

63 For instance, in 2017 ODIHR’s Prosecutors and Hate Crime Training Programme was implemented in Georgia (“Georgia | HCRW” Citation2023). Our interviewee who works for one of the most influential human rights Georgian NGOs makes a direct link between these and other efforts on the part of the OSCE and the Council of Europe (see, e.g., “Fighting Discrimination, Hate Crime and Hate Speech in Georgia” Citation2023) and the establishment in 2018 of a special unit to internally monitor the investigation process into hate crimes in the Ministry of Interior (Official at a major Georgian NGO, Tbilisi, June 19th, 2019; for more details see “National Frameworks to Address Hate Crime in Georgia | HCRW” Citation2023).

References

- Anceschi, Luca. 2008. Turkmenistan’s Foreign Policy: Positive Neutrality and the Consolidation of the Turkmen Regime. London and New York: Routledge.

- Ancker, Svetlana, and Bernd Rechel. 2015. “‘Donors Are Not Interested in Reality’: The Interplay Between International Donors and Local NGOs in Kyrgyzstan’s HIV/AIDS Sector.” Central Asian Survey 34 (4): 516–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2015.1091682.

- Ashley, Shena, Soonhee Kim, and William H. Lambright. 2020. “Charting Three Trajectories for Globalising Public Administration Research and Theory.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 43 (1): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23276665.2020.1789482

- Astapova, Anastasiya, Vasil Navumau, Ryhor Nizhnikau, and Leonid Polishchuk. 2022. “Authoritarian Cooptation of Civil Society: The Case of Belarus.” Europe-Asia Studies 74 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.2009773.

- Barnett, Michael, and Martha Finnemore. 2004. Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Bennett, Andrew, and Colin Elman. 2006. “Complex Causal Relations and Case Study Methods: The Example of Path Dependence.” Political Analysis 14 (3): 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj020.

- Braumoeller, Bear F. 2003. “Causal Complexity and the Study of Politics.” Political Analysis 11 (3): 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpg012

- Brewer, Garry D. 1974. “The Policy Sciences Emerge: To Nurture and Structure a Discipline.” Policy Sciences 5 (3): 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00144283.

- Broers, Laurence. 2005. “After the ‘Revolution’: Civil Society and the Challenges of Consolidating Democracy in Georgia.” Central Asian Survey 24 (3): 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634930500310444.

- Broome, André. 2008. “The Importance of Being Earnest: The IMF as a Reputational Intermediary.” New Political Economy 13 (2): 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563460802018216.

- Broome, André, Alexandra Homolar, and Matthias Kranke. 2018. “Bad Science: International Organizations and the Indirect Power of Global Benchmarking.” European Journal of International Relations 24 (3): 514–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117719320.

- Brugha, Ruairí, and Zsuzsa Varvasovszky. 2000. “Stakeholder Analysis: A Review.” Health Policy and Planning 15 (3): 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/15.3.239.

- Carothers, Thomas. 1999. Aiding Democracy Abroad: The Learning Curve. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wpj7p.

- Cerny, Phil. 2001. “From “Iron Triangles” to “Golden Pentangles”? Globalizing the Policy Process.” Global Governance 7 (4): 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-00704005

- Cheterian, Vicken. 2008. “Georgia’s Rose Revolution: Change or Repetition? Tension Between State-Building and Modernization Projects.” Nationalities Papers 36 (4): 689–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905990802230530.

- Delcour, Laure. 2017. The EU and Russia in Their “Contested Neighbourhood”: Multiple External Influences, Policy Transfer and Domestic Change. London and New York: Routledge.

- Dietrich, Simone. 2013. “Bypass or Engage? Explaining Donor Delivery Tactics in Foreign Aid Allocation.” International Studies Quarterly 57 (4): 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12041.

- Easton, David. 1965. A Framework for Political Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Fairbanks, Jr, Charles H, and Alexi Gugushvili. 2013. “A New Chance for Georgian Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 24 (1): 116–127. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2013.0002

- Fang, Songying, and Randall W. Stone. 2012. “International Organizations as Policy Advisors.” International Organization 66 (4): 537–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818312000276.

- Fazendeiro, Bernardo Teles. 2017. “Uzbekistan’s Defensive Self-Reliance: Karimov’s Foreign Policy Legacy.” International Affairs 93 (2): 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiw062

- “Fighting Discrimination, Hate Crime and Hate Speech in Georgia”. 2023. Council of Europe Office in Georgia. https://www.coe.int/en/web/tbilisi/fighting-discrimination-hate-crime-and-hate-speech-in-georgia.

- Freeman, John Leiper, and Judith Parris Stevens. 1987. “A Theoretical and Conceptual Reexamination of Subsystem Politics.” Public Policy and Administration 2 (1): 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/095207678700200102.

- Frye, Timothy. 2012. “In From the Cold: Institutions and Causal Inference in Postcommunist Studies.” Annual Review of Political Science 15 (1): 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-043010-095817.

- “Georgia | HCRW”. 2023. OSCE ODIHR Hate Crime Reporting. https://hatecrime.osce.org/georgia.

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine Publishing.

- Golosov, Grigorii V. 2013. “Authoritarian Party Systems: Patterns of Emergence, Sustainability and Survival.” Comparative Sociology 12 (5): 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-12341274

- Herold, Jana, Andrea Liese, Per-Olof Busch, and Hauke Feil. 2021. “Why National Ministries Consider the Policy Advice of International Bureaucracies: Survey Evidence from 106 Countries.” International Studies Quarterly 65 (3): 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab044.

- John, Peter. 2012. Analyzing Public Policy. 2nd ed. Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge.

- Kaiser, Paul J. 1996. “Structural Adjustment and the Fragile Nation: The Demise of Social Unity in Tanzania.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 34 (2): 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00055300.

- Kaiser, Markus, and Serik Beimenbetov. 2020. “The Role of Repatriate Organisations in the Integration of Kazakhstan’s Oralmandar.” Europe-Asia Studies 72 (8): 1403–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2020.1779183.

- Kakachia, Kornely, and Bidzina Lebanidze. 2016. “Georgia’s Protracted Transition: Civil Society, Party Politics and Challenges to Democratic Transformation.” In 25 Years of Independent Georgia: Achievements and Unfinished Projects, edited by Ghia Nodia, 130–161. Tbilisi: Ilia State University Press.

- Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2011. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues.” Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3 (02): 220–246. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1876404511200046.

- Kentikelenis, Alexander E., Thomas H. Stubbs, and Lawrence P. King. 2016. “IMF Conditionality and Development Policy Space, 1985–2014.” Review of International Political Economy 23 (4): 543–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1174953

- Kingdon, John. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Knox, Colin, and Sholpan Yessimova. 2015. “State-Society Relations: NGOs in Kazakhstan.” Journal of Civil Society 11 (3): 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2015.1058322.

- Korneev, Oleg. 2017. “International Organizations as Global Migration Governors: The World Bank in Central Asia.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 23 (3): 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02303005.

- Korneev, Oleg. 2018. “Self-Legitimation Through Knowledge Production Partnerships: International Organization for Migration in Central Asia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (10): 1673–1690. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1354057.