ABSTRACT

Do Europeans think about EU sanctions against member states and third countries in the same way? The EU regularly uses economic sanctions against third countries to promote democracy. Yet today with democracy being challenged within its borders by Hungary and Poland, the EU also resorts to coercive measures to react to norm violations among its members. Taking the case of Poland, we investigate public reactions to EU intentions to impose sanctions against EU members, non-members and Poland. Using a survey experiment in Poland, we study factors influencing how respondents think about EU sanctions, and whether the sanctions target matters.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) is a well-known democracy promoter both within and outside its borders and uses a diverse set of instruments to promote democracy to pressure other states to democratise or to protect the rule of law or respect human rights (Youngs Citation2009; Citation2010). These range from incentives to more coercive measures, such as conditionality, aid, sanctions or military interventions. Externally, the EU has an old tool to address the rule of law issues in its neighbourhood – sanctions (Giumelli Citation2011; Citation2013; Giumelli, Hoffmann, and Książczaková Citation2021; Portela Citation2012). Within the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), the EU imposed financial sanctions, freezing of assets, investment bans, flight bans, or embargoes on arms or other specific goods in non-member countries. Today, the EU is the only regional organisation that uses sanctions exclusively outside of its membership and against third countries (Hellquist and Palestini Citation2020).

Internally, the EU has also developed a growing set of mechanisms that can be used to sanction its member states, for example for breaches of EU fiscal rules (e.g. Van der Veer Citation2022). The EU also uses political conditionality as a part of the accession process; such tools were considered as the most effective instruments in the EU’s toolkit to promote democracy among the Central and Eastern European (CEE) states that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 (Pevehouse Citation2002; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2005; Vachudova Citation2005). Yet, in recent years, democracy and rule of law were serious curtailed in some CEE countries (Meunier and Vachudova Citation2018), and the EU has responded by introducing new internal sanctioning mechanisms in these areas, such as a rule of law conditionality mechanism in the EU budget to complement the existing Article 7 procedure.

Especially the serious violations of democratic norms and values by the “illiberal democracies” of Hungary under FIDESZ and Poland under Law and Justice (PiS), led by conservative-populist governments, have caused a dilemma for the EU: either it tolerates these regimes or enacts sanctions against its own member states. The European Commission, spurred on by the European Parliament, has already proposed sanction procedures under Art. 7 of the TFEU against Hungary and Poland, which are blocking adoption in the Council. The European Commission also decided to block transfers of national recovery funds to Poland for the purpose to rebuild the economy after the pandemic. The EU is holding up transfers to Poland under the National Recovery Plan because Warsaw threatens to undermine the EU’s legal order and fails to meet EU conditions on the rule of law, including implementing a European Court of Justice (CJEU) ruling on liquidation of the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court (Court of Justice of the European Union Citation2019).

The politicisation of such pending sanctions makes their application into an extremely sensitive issue for EU institutions. The EU’s authority to infringe on national sovereignty remains a topic of heavy political contestation (De Vries, Hobolt and Walter Citation2021) and nationalist populists like Orbán and Kaczynski have been keen to portray EU institutions as elitist foreign agents when they propose coercive measures against member states (Csehi and Zgut Citation2021). Recent research on the application of internal sanctions finds that EU institutions factor such dynamics into their decision making on whether or not to pursue them (e.g. Closa Citation2019; Mérand Citation2022; Van der Veer Citation2022).Footnote1 This creates a dilemma in which both the adoption and non-adoption of such sanctions potentially constitute existential threats to the EU itself.

In our study, we aim to connect three bodies of literature: democracy promotion, sanctions and their politicisation among mass publics. We do so to examine a crucial yet understudied factor when it comes to sanctions: the role of domestic audiences and their support for internal and external sanctions. Our approach seeks to address three lacunae of the existing literature, which has (1) treated the work on internal and external sanctions separately and (2) thus far focused mainly on states’ perspective when it comes to the latter. Our research design permits us to study attitudes towards internal and external sanctions and compare them to see whether the same characteristics of public opinion or different ones drive attitudes toward sanctions. We are therefore asking the following question: To what extent does the sanction’s target matter for public attitudes towards EU sanctions? In light of the findings in the literature, we also find it important to investigate factors affecting public opinion toward internal versus external actors, and the degree to which such factors are comparable.

To do so, we conducted a survey experiment in Poland in July 2021, when internal sanctions were not in force yet, and before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. We asked the respondents about their views on hypothetical EU sanctions against a non-EU country, other EU member states, and Poland itself. Poland appeared to be success story of democratisation; however, three decades after the fall of communism, Poland is experiencing the rise of right-wing populism strongly linked to nationalism and/or conservatism (Hanley and Vachudova Citation2018; Mudde Citation2007; Wodak Citation2015). Polish government attempts to dismantle democratic institutions, violate rule of law and limit the space for civil society are a part of a broader crisis of democracy, called de-democratisation, democratic-backsliding or “democratic rollback”Footnote2 in the CEE countries that joined the EU within so-called Eastern Enlargement.

Our findings indicate that contrary to our expectations, the nature of the sanction's target does not affect the individual attitudes toward the coercive measure used by the EU. By contrast, we find that satisfaction with democracy, support for the incumbent government, trust in institutions and support for the EU membership drive the support for sanctions. When it comes to differences between support for external, internal sanctions and sanctions against Poland, we find that individuals scoring high on populism tend to support external sanctions (but such populism is not linked to support of the other two types of sanctions). Support for current government is associated with lowered support for internal sanctions and sanctions against Poland.

EU internal and external sanctions

There are two international organisations that have used sanctions the most, namely the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU) Weber and Schneider (Citation2020) . Whereas the United Nations, as well as many other regional organisations, issue sanctions especially against member states, EU stands apart because it often imposes sanctions on non-members. We refer to the former as internal sanctions: punitive measures imposed by EU executive actors on individual member states that usually entail restrictions on the benefits of EU membership (such as cuts in funding or barring of voting rights).Footnote3 External sanctions, by contrast, are punitive measures imposed by EU executive actors on non-member states, which usually entail restrictions on the targets’ economic and political linkages to the EU and its member states (such as the right to enter the Schengen Area, conduct financial transactions with EU entities, or to trade with them).

While the literature on EU internal and external sanctions have largely developed independently from one another, internal and external sanctions share important commonalities. Foremost, both types of sanctions have the same goals: they aim to (1) signal norm violations and (2) coerce and (3) constrain a target into changing its behaviour.Footnote4 Second, both internal and external sanctions restrict targets of certain benefits: for member states it would be those benefits resulting from membership, such as funding or participation in decision-making; for non-member states, however, it would be a deprived access to EU territory (e.g. travel bans, ban on the overflight of EU airspace) or denied privileged economic (e.g. withdrawing benefits under the Generalised System of Preferences, economic sanctions, asset freeze) and political relations (suspended accession talks). In the latter group of sanctioning countries, we also include those countries that have prospect of membership, due to human rights violations or deficit in the rule of law and insufficient congruence with conditions for accession, accession negotiations with them have stalled. As an example may serve Turkey.

Finally, a third important commonality between these sanctions is that both internal and external are mostly imposed by the EU to promote and protect democracy within its borders and beyond. This is the case for external EU sanctions imposed on autocratic regimes, such as Belarus and Russia (Portela et al. Citation2021; Cardwell and Moret Citation2023), many years before the Russian aggression against Ukraine beginning in 2014. Belarus especially was sanctioned in relation to the violent repression and intimidation of opposition members, protestors and journalists, and also in relation to election falsification.Footnote5 To protect and safeguard democracy within its community, the EU has threatened or imposed the internal sanctions when its member states breach fiscal rules (Van der Veer Citation2021), misrepresent official statistics (Savage and Howarth Citation2018) or weaken the rule of law (Closa Citation2019).

The commonalities between internal and external sanctions are most visible in the area of democracy promotion and protection and this is also something that distinguishes the EU from other sanction senders. Thanks to its differentiated mandate, the EU can implement sanctions on the ground of human rights violations or to promote democracy, unlike the UN. Although CFSP objectives [TEU, Art. 21(2)] stress the need to “preserve peace, prevent conflicts and strengthen international security,” these concerns are only mentioned later, thus implying that rule of law concerns should be prioritised by the EU. This contrasts with the UN sanctions, which tend to prioritise peace and security needs (UN Charter Chapter VII, Art. 39) over concerns related to the rule of law. Indeed, the EU treats human rights violations, rule of law infringement and democracy breaches as important rationales behind sanction imposition. The EU hence not only implements the UN sanctions but also adds to them or develops completely new sanctions regimes (Pospieszna and Portela Citation2020; Portela Citation2021).

The EU is also fairly unique in that it has, thus far, imposed sanctions in reaction to a variety of democratic crises exclusively on non-members. Today, however, the EU faces rule of law violation also among its membership. The European Union portrays itself as a community of democracies, where the rule of law is a cornerstone of the community (Closa and Kochenov Citation2016). The European Court of Justice proclaimed that European Community was “a Community based on the rule of law” over 35 years ago, and upheld this view ever since (Pech Citation2009, 3). Hence, the rule of law can be considered a core community norm.

While in the past the EU was perceived as a relatively homogenous regional organisation, today it faces serious internal disagreements over democratic conditionality and breaches of democratic norms. Countries that were considered a success story of third wave democratisation now are part of a third wave of autocratisation (Lührmann and Lindberg Citation2019; Meunier and Vachudova Citation2018). Literature on backsliding shows that governments in countries like Poland undermine judicial independence, limit the powers of the Constitutional court and restrict the activity of non-governmental organisations that promote liberal values (Grudzińska-Gross Citation2014; Kotwas and Kubik Citation2019). Several specific features of the EU’s political system, including EU’s political reluctance to intervene in domestic affairs of its members and ability of EU’s authoritarians to steer the financial flows, contribute to the perpetuation of such authoritarian tendencies (Kelemen Citation2020). This is a new situation for the organisation to apply internal sanctions.

The decision-making process and mechanisms to apply external sanctions differ from those to impose internal EU sanctions. External sanctions are established through unanimous decisions by the European Council, requiring the consent of all member nations. Certain measures, such as arms embargoes and travel restrictions, are subsequently enforced by individual EU member states without the need for additional EU-level decisions. Economic sanctions, on the other hand, require the enactment of implementing legislation, known as a European Council regulation, which has immediate legal authority over EU citizens and businesses (Farrall Citation2016). Ultimately, the target is deprived benefits resulting from the relations with the EU as an organisation but also from relations with EU member states, which also might affect them if economic sanctions are employed. The EU’s first internal sanctions mechanisms were related to the European Monetary Union (EMU) and were introduced with the Maastricht Treaty. Yet in developing a sanction regime for liberal democracy promotion in its member states, the EU was relatively late: it included a suspension clause (Article 7) in the Treaty of Amsterdam (1997/1999) and later amendments in the Treaty of Nice (2001/2003). Intergovernmentalism and intra-institutional bargaining are the dominant dynamics as regards the application of these sanctions (Closa Citation2020). But considerations are not only utilitarian. Supranational institutions like the European Parliament (EP) and (especially) the non-majoritarian Commission must tread carefully or risk being portrayed as foreign agents and elitist institutions overstepping their mandates to claw powers away from national governments in the eyes of publics, increasingly divided over a transnational cleavage. Especially exclusive conceptions of national community are “weaponised” by those who view the nation state as the sole legitimate vessel of government to politicise any attempt at infringing on the sovereignty of those national communities (Hooghe and Marks Citation2020, p. 824).

Because the EU’s internal sanctions are relatively new and have never been applied for violations of democracy and rule of law, there is comparatively more scholarship on the external sanctions. The only previous situation when the EU considered sanctioning a member state happened in 2000, when Austrian Freedom Party became part of the Austrian ruling coalition (Merlingen, Mudde, and Sedelmeier Citation2001). However, today there is an opportunity to fill this gap as the EU threatens its two member states, Poland and Hungary, with the activation of the new conditionality mechanism, which came into effect in 2021, and which allows the EU to cut funding in cases when certain rule-of-law breaches take place.

By triggering a mechanism, which the EU has never used before, the EU hoped to influence the Polish right-wing government to take appropriate measures to improve judicial independence. There have been a series of questions over alleged rule of law violations in Poland, including subordination of the judicial branch.Footnote6 Thus Poland has been under pressure now to dismantle a controversial disciplinary chamber for judges, which the European Court of Justice has found to be illegal. Moreover, Warsaw showed disrespect for EU law, especially when Polish Constitutional Court ruled that key elements of EU law were incompatible with the country’s constitution. Given these developments, the Polish case seems to be particularly interesting to investigate, especially the public views on EU sanctions in this likely-to-be sanctioned country.

Public support for EU sanctions

One of the main research gaps currently existing in the study of EU sanctions is the relative absence of work on public views on EU sanctions. Scholars have recognised the central role the public opinion plays in European foreign policy (Faust and Garcia Citation2014; Gravelle, Reifler, and Scotto Citation2017; Oppermann and Viehrig Citation2009). Yet, the studies regarding public opinion vis-à-vis sanctions are scarce. While the study of public opinion has been very popular in other aspects of EU policy, there are comparatively fewer studies on public opinion on EU foreign policy in general and on external sanctions specifically (Seitz and Zazzaro Citation2020; Onderco Citation2017). This is somewhat mirrored by the absence of studies on the EU’s internal sanctions imposition. For these reasons, we focus on mapping and explaining the public views on EU sanctions – both internal and external.

But the public views matter, not only because the voters vote leaders into the office but also because the EU relies heavily on output legitimacy. Existing scholarship has shown that citizens’ perception may challenge sanction policies making it hard for the EU to keep consensus and overall sanction policy fragile (Portela et al. Citation2021). The effectiveness of foreign policymaker’s actions is evaluated by the public, and their opinion may pressure leaders to act in a certain manner to gain more supporters. Moreover, sanctions may also prove reactions from other like-minded member states who oppose the action, and as the sanctions become politicised.

Public opinion also matters because although the EU’s external and internal sanction mechanisms are both weak, their activation is often opposed by actors in both the target and sender polities. Sanctions’ imposition triggers contestation regarding the interpretation of the crisis, violations of norms, and such contestation usually comes from the governments that are targeted with sanctions. In case of internal sanctions, democratic backsliding is an important factor which affects contestation of sanctions. Recent research also finds that the perceptions of domestic audiences shape the willingness of EU institutions to resort to sanctions – at least internally (e.g. Van der Veer Citation2022; Mérand Citation2022). It is thus important to find out what citizens think about sanctions and whether they support or oppose these sanctions.

We believe that it is important to distinguish between the types of targets, as the nature of the actor may matter for whether citizens approve the use of sanctions. Almost a decade ago, Portela and Orbie (Citation2014) remarked that there is a remarkable coherence between how the EU “sanctions” its trade partners by withdrawing benefits under the Generalised System of Preferences and how it punished norm-breaking abroad by using sanctions. However, as Hellquist (Citation2019) remarked, the EU has been at the same time highly willing to sanction external actors but reluctant to sanctioned own member states. The difference comes from the different ostracising norms of behaviour applied to different groups of states.

Such an explanation would be also consistent with the so-called signalling purpose of sanctions. In this reading, the purpose of sanctioning is to indicate the importance of the particular norm (Giumelli Citation2013) but also whether the state is to be considered as a member of the in-group or the out-group. Sanctions are meant to stigmatise the out-group members (Sjoberg Citation2006). The use of sanctions is then seen as an enforcement of particular norms in the international community (Homolar Citation2011; Nossal Citation1989). As the international relations scholarship building on constructivist insights argued, based on the interactionist perspectives on deviance in sociology (Becker Citation1963; Durkheim Citation1973), the application of sanctions on norm-breakers is associated with normative opprobrium (Wagner Citation2014). Interactionism recognises that norms – as well as punishment – are time and space dependent (Ben-Yehuda Citation1990). Punishment communicates who deserves it (Van Prooijen Citation2018).

It is therefore understandable that the members of the community would hold stronger feelings against the members of out-groups. As behavioural economists demonstrated, in-groups behave with hostility against out-groups which threaten the in-group norms (Akerlof and Kranton Citation2000; Citation2005; McLeish and Oxoby Citation2007). These findings also gel with the findings from psychology where different norms of punishment between in- and out-group are found (Van Prooijen Citation2018). We therefore expect that respondents will have more negative views, the more outside the target is outside their in-group.

H1 Ceteris paribus, EU citizens will have strongest punitive impulses towards non-EU countries, followed by other EU countries, and weakest towards their own country.

Given the nature of internal sanctions, which are imposed against the member states, we look for possible factors affecting the support for these coercive measures in extant research on public opinion towards the EU. Individual support may be dependent on socio-demographic and socio-economic background factors, such as age and levels of education and income, and also to a large extent on political and identarian attitudes (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016; Lauterbach and De Vries Citation2020). Drawing on these insights, we conceptualise the drivers of public views of sanctions along four lines: (a) satisfaction with democracy; (b) support for the incumbent government; (c) populism and (d) attitudes towards the EU.

Citizens hold views about normative issues related to government and democracy. Scholars in the field of European studies suggest that satisfaction with democracy and policy performance at the national level is an important factor in explaining the support for integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2020, Carey Citation2002; McLaren Citation2006). The link between negative evaluations of democracy and of the incumbents on one hand and Eurosceptical attitudes on the other hand has been well established (Gabel Citation1998; McLaren Citation2006). We hypothesise that citizens satisfied with the level of democracy in their country will be obviously less supportive of sanctions against their country but also against other EU members as they are satisfied with the rule of law. However, we hypothesise that they would be more supportive of external sanctions, because they would perceive the norm-breaking by external actors as a threat to the in-group norms that they value.

H2a EU citizens who are satisfied with the state of democracy in their own country are less likely to support the EU internal sanctions, regardless sanctions being imposed against their own country or another EU member state.

H2b EU citizens who are satisfied with the state of democracy in their own country are more likely to support the EU external sanctions.

We believe that the approval of the incumbent government matters for sanction approval for two reasons. First, for internal sanctions, government approval functions through the rallying-round-the-flag effect (Galtung Citation1967; Grossman, Manekin, and Margalit Citation2018). Together with Hungary, Poland is one of the two countries currently facing EU internal sanctions. These governments engage in an elaborate domestic game to influence public opinion and to strengthen their political legitimacy (Soyaltin-Colella Citation2020). Governments might invoke the rally-round-the-flag by presenting internal sanctions as too much of the intervention of the EU into the domestic affairs and even violation of national interest. Second, for external sanctions, because the external sanctions are approved by the EU together with other member states, the positive views of the national government should translate into political support for the nations’ foreign policy. Because external sanctions have to be approved by all EU member states, the trust in national government should translate into higher support for such sanctions (see also Onderco Citation2017).

H3a The higher EU citizens’ support for the incumbent government the lower the support for EU internal sanctions, regardless sanctions being imposed against their own country or another EU member state.

H3b The higher EU citizens’ support for the incumbent government the higher the support for EU external sanctions

The emergence of populist political parties (Taggart Citation1998; Hooghe Citation2007) challenges support for the EU policies and reinforces Euroscepticism, and thus it might be expected that populism also affects the support for EU sanctions. In recent years, scholars have also highlighted that populist ideology influences governments’ foreign policies (Destradi, Cadier, and Plagemann Citation2021; Verbeek and Zaslove Citation2017). Populism is often understood as a thin ideology which concentrates around the ideas of opposition to the elites and focus on “the people” (Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove Citation2014; Mudde Citation2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Citation2013).

Because of the “people-centrism” of populism, we hypothesise that the impact of populism is conditional upon who the target of sanctions is. If the target is European, populists’ anti-EU attitudes kick-in (Chryssogelos Citation2010; Schlipphak and Treib Citation2017). In the EU setting, the existing rules are seen as dilution of the popular will and hence, the sanctions for violations of such rule of law are seen as reinforcing the EU rules (Chryssogelos Citation2017). In Polish context, populist right-wing government aimed to achieve concentration of power through “neutralisation of external threats” which for Law and Justice party has been the European Union. Moreover, appeals to nationalism as a populist ideological instrument help the current government to make the impact of the EU on Poland ineffective and to counter any leverage that the EU might have on domestic affairs.Footnote7

The imposition of EU sanctions on an EU member state – whether Poland or another country – highlights in the populist mindset the EU’s decision-making and role being placed at the heart of a policy dispute. Individuals who espouse populist views may reject sanctions as a tool of EU policy, because the use of such policy is seen as being done by the unelected elites “in Brussels”. Hence, the populist views may mitigate the willingness of respondents to impose sanctions on other countries.

H4 The higher the inclination toward populism among the EU citizens, the lower the support for EU internal and external sanctions.

Last but not least, citizens might not be aware of what the process of reaching consensus regarding the sanction imposition might look like at the EU level but might be aware of what the European Union is. Citizens do have opinions, perceptions, views of the EU and are able to recognise different EU institutions (see, e.g. van Elsas et al. Citation2020). Thus it is important to consider the views of the EU as the sanctioning source as it might matter for the approval of sanctions. Scholars have studied the legitimacy of sanction senders and found very mixed results. Hurd (Citation2002) argues that the weak representativeness, decision-making bias and lack of reform of the United Nations Security Council, undermines the UN legitimacy. Studying regional organisations as sanction senders, scholars have found that the legitimacy of these organisations is boosted when the sanctions are impartial, transparent, socially accepted and consistent (Soyaltin-Colella Citation2020). The legitimacy of the sender may also increase if sanctions fit the political agenda of the incumbents. Some research shows that if regional sanction senders can operate not as an external intervener but as “peer review”, this will increase their legitimacy (Hellquist Citation2021).

In the EU context, research has found more direct linkages between sanctions and public opinion. Existing cross-national work on the approval of the EU sanctions shows that attitudes towards the EU shape individuals’ views towards the sanctions (Onderco Citation2017). Because such sanctions are decided by the EU and they demonstrate EU activity, they tap into legitimacy beliefs about the European Union. If citizens do not approve of the European Union, they are less likely to approve EU’s actions. That has consequences for sanctioning practice as much as for other EU public policies (De Vries Citation2018). Therefore, if citizens are distrustful of the EU, they can reasonably expected to be less supportive of the EU imposing sanctions, regardless of whether the target is internal or external. The EU in such situations acts as a sanctioning authority, in the perception of the individuals, and therefore their evaluations of the EU factor in their assessment of sanctions. These insights are corroborated by existing work on sanctions attitudes in other settings, which showed that public attitudes towards the sender matter for sanctions approval (Frye, Citation2019; Sejersen, Citation2021).

For this reason, we hypothesise that the higher approval of the EU translates into higher approval of sanctions.

H5 The higher the approval of the EU, the higher the support of EU citizens for both internal and external EU sanctions.

Data and methods

In our study, we aim to study the public opinion vis-a vis sanctions of one of the EU member states against which the EU has aimed to use coercive measures: Poland. We select Poland as a case since at the time, the discussion about the possible EU coercive measures against Poland were less prominent than in the other possible case – Hungary. Only by 2023 did the issue of blocking the contributions from the Recovery and Resilience Fund became a domestically salient issue (Cienski Citation2023).

To investigate the support for sanctions we have conducted a survey experiment among a representative sample of Poles (N = 986). The survey has been administered by a professional public opinion agency and was a part of a regular monthly Omnibus survey conducted in July 2021.Footnote8 The respondents were presented with a vignette, which posed a hypothetical scenario in which a state (our treatment) violates the rule of law and the EU subsequently considers to sanction this state. We then asked respondents regarding their views on the possible imposition of the sanction in this hypothetical scenario. These and the other items listed below all used five-point Likert items, unless stated otherwise.

Support for sanctions is measured in two ways – through a general evaluation of the decision to impose the sanction, and a functional evaluation of the potential outcome. Thus our dependent variable measures the respondent’s agreement to two questions. Sanction approval is captured as follows: Can you indicate whether or not you agree with the EU’s decision to impose sanctions on [a non-EU member state/an EU member state/Poland]? Sanction effectiveness is captured as follows: In your opinion, will these sanctions imposed by the EU be effective in protecting the rule of law in [a non-EU member state/another EU member state/Poland]?

Next to our treatment, our main independent variables are: (1) approval of the incumbent government; (2) satisfaction with the state of democracy; (3) populism and (4) support for EU membership. Our measure captures government support through the following item: Overall, how do you evaluate the government’s activities? The satisfaction with the state of democracy in the one’s country by measuring agreement the following item: Overall, I am pleased with how democracy functions in my country. Populism was measured using the standard six-item scale proposed by Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove (Citation2014). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated that only three of six items loaded onto a single factor to a satisfactory degree (see Appendix). Still, because this scale is the standard means of measuring populist attitudes in political science, we calculate our final populism measure as the average score of a respondent on all six items to maintain theoretical parity (see Discussion). Finally, we used the following item to capture a respondent’s attitudes towards the EU: Overall, I think that Poland’s membership of the EU is a good thing. This measure is the standard in EU scholarship because it taps into both utilitarian as well as identarian dimensions of EU support (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016).

We furthermore control for the level of national institutional trust among respondents, using a scale based on trust in Polish state media, law enforcement, Courts and the Catholic Church. These four items loaded satisfactorily onto a single dimension in a CFA (see Appendix). We also probed the interest in politics of respondents using the following item: Are you interested in politics and to what extent? This item had four response categories, ranging from no interest to very interested. We also include demographics: age, gender, education (recoded to low, middle and high), and a respondent’s assessment of their household’s financial situation as either good, bad or neither good nor bad.

We treat the five-point Likert items as continuous measures in our analysis and recode items with fewer response options to dichotomous measures. We also centre all predictors and standardise the non-binary predictors by two standard deviations (Gelman and Hill Citation2007). Finally, we weigh our observations using stratification weights to ensure the representativeness of our sample with respect to the Polish population. We recode our dependent variables to dichotomous measures indicating agreement with the underlying survey items and use logistic regression models to estimate the effects of our predictor variables on support for sanctions and belief in sanction effectiveness.Footnote9 We initially run models over the full sample while including interaction effects between our treatment variables and our main independent variables of interest, to gauge whether the effects of these variables vary across treatments. These models use “another EU member state” as the control group. We subsequently run split-sample regression analyses per treatment group. No modelling assumptions were violated by the models presented below.

Results

Let us first turn to the results of the overall analysis. offers the overview of the most important results.

Table 1. Full sample logits.

Starting with our main hypotheses, surprisingly, our treatments indicate no direct effect of the type of target on support for the sanction or the belief in its success. This runs counter to Hypothesis 1, where we expected that a differentiated approach towards norm-breaking by out-group and in-group actors would lead to differentiated attitudes towards the sanction.

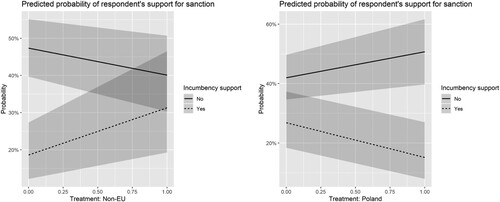

We find that the satisfaction with democracy has a statistically significant and negative effect on the support for sanctions. Respondents who believed democracy in Poland functioned well appear more likely to flat-out reject any form of EU sanction, whether external or internal, thus we have found support for our Hypothesis 2a but not 2b. Relatedly, support for the PiS government has a similar, negative and significant effect on support for the sanctions. Yet the real interesting finding here is the near-significant interaction between incumbent support and our treatments: supporters of the incumbent government are more likely to support sanctions for non-EU member states vis-à-vis EU member states. Moreover, they are less likely to support sanctions against Poland, while those disapproving of the PiS government appear more supportive of sanctioning Poland than another EU member state (see ). Thus, we have found full support for Hypothesis 3b, but only a partial once for Hypothesis 3a. We think that a probable explanation for these findings is that our case is a country which experiences democratic backsliding caused by the PiS governments. This trend has been met with the strong opposition from the pro-democratic forces defending liberal democracy and this strand of civil society is more likely to accept EU sanctions against Poland, as our results show.

Figure 1. Conditional effect of incumbency support and Poland (treatment) on support for EU sanctions.

In terms of beliefs in the effectiveness of sanctions, we find an even stronger, comparable and significant interaction effect between incumbency support and Poland as treatment, suggesting polarisation on the belief that sanctions will have a meaningful impact between those supporting and opposing the PiS government.

We find no overall effect of populism on either outcome, and, more importantly, no relationship between populist attitudes and our treatment variables. Again, this initially disconfirms Hypotheses 4 (but see below). It should be noted that we adopted the Akkerman’s measure of populism, which may not capture all nuanced characteristics of populist attitudes in the Polish context. As Vachudova (Citation2020) noted, PiS represents ethnopopulism – which is an elite strategy of gaining power that is flexible with the truth and with identifying enemies and friends of the people. Importantly, it equips political leaders with greater flexibility than ethnic nationalism in determining friends and enemies. An enemy is inter alia the EU. Thus, because the right-wing government in power is a populist government, it commonly accepted that populists in Poland are people who oppose the EU and who show support for conservatism and nationalism.

Nevertheless, we do find that support for our Hypothesis 5, as EU membership is the strongest predictor of both support for and beliefs in the effectiveness of sanctions. It appears that positive views of the EU have a blanket positive effect on support for EU action and belief in the coercive efficacy of the EU: respondents who have positive views of the EU are, ceteris paribus, more than four times more likely to approve the use of sanctions, and more than twice as likely to believe that sanctions will be effective in achieving the desired policy goals. There appears to be an interaction between this variable and the treatment Poland, suggesting that support for the sanction among those supportive of EU membership is lower when it concerns their country of residence. However, this estimate does not pass conventional thresholds for statistical significance (p = 0.087).

Moving beyond the main hypothesised effects, we also find that respondents with high trust in national institutions are generally supportive of sanctions and believe that sanctions can be successful in delivering change. Finally, those who view the financial situation of their household as poor also tend to be more supportive of EU sanctions.

After presenting the overall data, we then dive into looking more precisely at factors predicting agreement with internal sanctions. For this reason, we split the sample along our three types of sanctions targets. The results from this analysis can be found in .

Table 2. Factors influencing approval of sanctions in individual scenarios.

Starting with the sanctions on non-EU member states in Model 3, our findings indicate that as hypothesised in Hypothesis 4, populist attitudes are statistically significantly positively associated with support for sanctions on non-EU members. Individuals with populist attitudes are about twice as likely to approve the use of sanctions against non-EU members for violations of rule of law. Similarly, satisfaction with democracy is significantly and negatively associated with support for sanctions. Supporters of EU membership are about three times as likely to support the use of sanctions.

Moving on to Model 4 which looks at sanctions on other EU member states, we see that individual-level populism is not statistically significantly associated with approval of sanctions. The only factor which is statistically significantly associated with the approval of sanctions on EU members is satisfaction with EU membership – individuals who see EU membership positively are about four times as likely to support EU sanctions on EU members. Both satisfaction with democracy and support for the incumbent government have near-significant, negative relationships to support for sanctions in this case.

Looking at the approval of the sanctions on Poland itself, we find that the respondents who see EU membership positively are about 2.3 times more likely to support the use of sanctions. By contrast, populism has no statistically significant effect. Unsurprisingly, respondents who supported the PiS government in Poland in power at the time are 70% less likely to approve the use of sanctions, and those who are satisfied with democracy in Poland are 50% less likely to approve of sanctions. Again, those viewing their household’s financial situation negatively are 2.4 times as likely to support sanctions against the PiS government.

Overall, our results suggest that while there are small differences in factors which explain the support of sanctions depending on the sanctions target, overall, the type of target seems not to matter as much as we would expect based on theory. Contrary to the expectations, whether the target of the sanctions is internal or external does not matter too much for Polish respondents. However, the supporters of the PiS government in power at the time of the study were strongly opposed to the imposition of sanctions. Instead, the strongest effect is the blanket effect of support for EU membership, suggesting that those approving of the EU simply support EU action against backsliding – regardless of the target. This finding is seemingly in conflict with the findings of earlier scholarship which argued that EU applies different norms towards internal and external norm-breaking (Hellquist Citation2019). However, our findings also may indicate that there is a greater difference between norms applied at the level of the general public and by elites (cf. Kertzer Citation2020). In a security policy setting, European scholars already indicated that there are systematic differences how European elites and publics think about policy puzzles, and it is not inconceivable that such difference applies in the areas of rules of law as well.

We also find that populism has only limited degree on public attitudes, basically only influencing sanctions against external actors. This may partially be explained by the prevalence of nationalist-populist sentiment in Poland, which heavily relies on the social construction of in- and outgroups. By contrast, we find the approval of EU membership as a very important factor, confirming the earlier scholarship, and confirming that EU sanctions are mainly seen as an EU policy.

Conclusion

In this article, we looked at the public attitudes towards internal and external EU sanctions in Poland. We looked at whether respondents approved the use of sanctions, and whether they thought the sanctions are likely to be successful, depending on who was the target of these sanctions – a non-EU country, an EU member or Poland itself. Our findings indicate that the identity of the target does not necessarily matter. We also find that populism has only limited impact – influencing whether citizens approve sanctions against non-EU members, but not otherwise.

The reason why populism has no effect on attitudes toward internal sanctions may be due to the specificity of populism in the Polish context, which is right-wing, strongly linked to nationalism and/or conservatism (Hanley and Vachudova Citation2018; Mudde Citation2007). Nationalism as an ideological instrument is used to make the impact of the European Union (EU) on Poland ineffective and to neutralise any leverage that the EU might have (e.g. rejecting efforts of community to tie the budget to the rule of law) justifying that it is a threat that is violating national values, interests and sovereignty. The logical consequence of the reasoning is that the right-wing government decided what was the national interest that should be protected and who were the enemies that should be eliminated. According to the Polish government in power at the time of the survey, conservative values, which derive from national or religious culture, needed to be protected and this rhetoric was used in the governmental propaganda (e.g. public media). These features are linked to populism in Poland and define the profile of the person that is in favour of populism, however, this might be the case that the adopted measure by us in the study does not capture the specificity of the Polish, and CEE, context.

The strongest factor associated with the approval of the EU sanctions is the view of EU membership: in the case of rule of law violations, EU supporters also support EU sanctions, even against their own member state. This finding is important because it shows that opinions on sanctions within member states may also be more heterogeneous than expected, and suggests the actual imposition of sanctions may not be as harmful to EU legitimacy in the target state as commonly assumed (Closa Citation2019). This invites more research on attitudes towards internal sanctions in other areas, such as economic governance, which concern less fundamental EU values such as balanced budgets.

In our research, we aimed at contributing to the scholarship on EU sanctions, by bridging the scholarship on EU’s internal and external sanctions and bringing more empirical scholarship into the discussion. However, our results indicate that more research is needed to understand the differences between the public and elite levels where the different norms apply (Hellquist Citation2019).

Furthermore, future work should look more explicitly the punitive roots of sanctions approval. Past work has demonstrated that the support of sanctions on international norm-breakers is linked to punitive attitudes, both at the macro- (Stein Citation2015; Wagner and Onderco Citation2014) and micro-levels (Liberman Citation2006; Citation2013). Linking the work on punishment and its roots to EU sanctions is a natural next step for this scholarship. Last but not least, future work should look at the link between internal and external sanctions also in other EU member states. Generalising from a single case is often difficult if not impossible. While Poland is a good country case where both internal and external EU sanctions are salient, and where many factors such as populism and authoritarian tendencies are present, only future studies can confirm (or disconfirm) the generalisability of our findings.

Our work also adds to the scholarship on Art 7 sanctions, as we demonstrate that the opposition to the sanctions is actually closely linked to anti-EU views. The opponents of sanctions are likely negative of the EU itself. This finding supports the earlier work by Schlipphak and Treib (Citation2017) who argued that EU’s steps to address rule of law crises in member states can instead end up with a blow-back. Finally, we believe that our findings are important for the literature on democratic backsliding in Poland which further polarised the society. Illiberal political actors in Poland form a global pushback against Western liberal democratic norms that the European Union has been promoting whereas liberal actors struggle to advocate for a pro-EU stance among civil society. By studying citizens’ perceptions vis-à-vis the EU sanction regime and linking it to overall support for the EU, we also contribute to better understanding of the demand dimension of populist politics and overall erosion of democracy and EU values in Poland and elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

We thank the EEP’s reviewers and editors for excellent comments which helped us to make the article significantly better. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the University of Florence and at Erasmus University Rotterdam in December 2021, International Studies Association Annual Convention 2022, as well as during ECPR Annual Convention 2022. We thank Antonio Bultrini, Navin Bapat, Geske Dijkstra, Tom Etienne, Francesco Giumelli, Markus Haverland, Katharina Meissner, Stefano Palestini, Dursun Peksen, Clara Portela and Asya Zhelyazkova for their great comments and suggestions. All mistakes remain our own. This work was supported by National Science Center (NCN) in Poland under Grant UMO-2014/15/G/HS5/04845; Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence “EU external actions in the contested global order – (In)coherence, (dis)continuity, resilience” under Grant 599622-EPP-1-2018-1-PL-EPPJMO-CoE and Charles University Research Centre program under Grant UNCE/HUM/028. (The European Commission support does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We side-step here the existing scholarship on the EU’s infringement procedures which are different in the sense that their use is much more prevalent, and as such far less politicized. For key works in this field, see for example Mastenbroek (Citation2005), Versluis (Citation2007) and Zhelyazkova and Torenvlied (Citation2009).

2 Some important literature on the topic includes Bermeo (2016, p. 5); Coppedge (2017); Diamond (2008); Lührmann and Lindberg (Citation2019).

3 Please note that we exclude judicial sanctions when referring to internal sanctions: while judicial sanctions have recently indeed been levied against Hungary and Poland in the context of rule of law (Turnbull-Dugarte and Devine, 2021), they are a commonplace feature of a functioning rule of law and concern breaches of secondary or tertiary law. Executive sanctions, on the other hand, relate to primary law: their imposition is a highly political act that involves extensive political deliberation.

4 The coerce–constrain–punish framework was introduced by Giumelli (Citation2011) and is by now broadly accepted in the political science study of sanctions.

5 See the “Timeline – EU restrictive measures against Belarus,” available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/restrictive-measures-against-belarus/belarus-timeline/

6 See European Commission’s press release “Rule of Law: European Commission refers Poland to the European Court of Justice to protect independence of Polish judges and asks for interim measures” available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/CS/IP_21_1524

7 For a detailed analysis of how two ideological instruments, nationalism and conservatism are used by Polish right-wing government see Magyar and Madlovics (2020).

8 The administering agency is compliant with the ICC/ESOMAR International Code on Market and Social Research. The survey instrument was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Albany under nr 21X213.

9 We are well aware that dependent variables based on Likert items are best modelled using ordered logistic regression. However, upon doing so, we found that such models severely violate the proportional odds assumption that underlies such models.

References

- Akerlof, George A., and Rachel E. Kranton. 2000. “Economics and Identity.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (3): 715–753. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554881

- Akerlof, George A., and Rachel E. Kranton. 2005. “Identity and the Economics of Organizations.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 19 (1): 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/0895330053147930

- Akkerman, Agnes, Cas Mudde, and Andrej Zaslove. 2014. “How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (9): 1324–1353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013512600

- Becker, Howard Saul. 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: The Free Press.

- Ben-Yehuda, Nachman. 1990. The Politics and Morality of Deviance: Moral Panics, Drug Abuse, Deviant Science, and Reversed Stigmatization. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Cardwell, Paul James, and Erica Moret. 2023. “The EU, Sanctions and Regional Leadership.” European Security 32 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2022.2085997

- Carey, Sean. 2002. “Undivided Loyalties: Is National Identity an Obstacle to European Integration?” European Union Politics 3 (4): 387–413.

- Chryssogelos, Angelos-Stylianos. 2010. “Undermining the West from Within: European Populists, the USs and Russia.” European View 9 (2): 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12290-010-0135-1

- Chryssogelos, Angelos. 2017. Populism in Foreign Policy (Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics).

- Cienski, Jan. 2023. Duda throws Poland’s EU cash plans into turmoil. Politico. Retrieved from https://www.politico.eu/article/poland-andrzej-duda-eu-recovery-fund-throws-polands-eu-cash-plans-into-turmoil/.

- Closa, Carlos. 2019. “The Politics of Guarding the Treaties: Commission Scrutiny of Rule of law Compliance.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (5): 696–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1477822

- Closa, Carlos. 2020. “Institutional Logics and the EU’s Limited Sanctioning Capacity Under Article 7 TEU.” International Political Science Review 42 (4): 501–515.

- Closa, Carlos, and Dimitry Kochenov. 2016. Reinforcing Rule of Law Oversight in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Court of Justice of the European Union. 2019. Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber). Joined Cases C–585/18, C–624/18 and C–625/18. Retrieved from https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=220770&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=1703222.

- Csehi, Robert, and Edit Zgut. 2021. “‘We won’t let Brussels dictate us’: Eurosceptic populism in Hungary and Poland.” European Politics and Society 22.1 (2021): 53–68.

- Destradi, Sandra, David Cadier, and Johannes Plagemann. 2021. “Populism and Foreign Policy: A Research Agenda (Introduction).” Comparative European Politics 19 (6): 663–682.

- De Vries, Catherine E. 2018. Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- De Vries, Catherine E., Sara B. Hobolt, and Stefanie Walter. 2021. “Politicizing International Cooperation: The Mass Public, Political Entrepreneurs, and Political Opportunity Structures.” International Organization 75 (2): 306–332.

- Durkheim, Emile. 1973. “Two Laws of Penal Evolution.” Economy and Society 2 (3): 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000014

- Farrall, Jeremy. 2016. “Sanctions.” In The Oxford Handbook of International Organizations, edited by Jacob Katz Cogan, Ian Hurd, and Ian Johnstone, 603–621. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Faust, Jörg, and Maria Melody Garcia. 2014. “With or Without Force? European Public Opinion on Democracy Promotion.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (4): 861–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12120

- Frye, Timothy. 2019. “Economic Sanctions and Public Opinion: Survey Experiments from Russia.” Comparative Political Studies 52 (7): 967–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018806530

- Gabel, Matthew. 1998. “Public Support for European Integration: An Empirical Test of Five Theories.” The Journal of Politics 60 (2): 333–354.

- Galtung, Johan. 1967. “On the Effects of International Economic Sanctions: With Examples from the Case of Rhodesia.” World Politics 19 (3): 378–416. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009785

- Gelman, Andrew, and Jennifer Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Giumelli, Francesco. 2011. Coercing, Constraining and Signalling: Explaining UN and EU Sanctions After the Cold War. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Giumelli, Francesco. 2013. ‘How EU Sanctions Work: A New Narrative’. EU ISS Chaillot Paper No.129.

- Giumelli, Francesco, Fabian Hoffmann, and Anna Książczaková. 2021. “The When, What, Where and Why of European Union Sanctions.” European Security 30 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2020.1797685

- Gravelle, Timothy B., Jason Reifler, and Thomas J. Scotto. 2017. “The Structure of Foreign Policy Attitudes in Transatlantic Perspective: Comparing the United States, United Kingdom, France and Germany.” European Journal of Political Research 56 (4): 757–776. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12197

- Grossman, Guy, Devorah Manekin, and Yotam Margalit. 2018. “How Sanctions Affect Public Opinion in Target Countries: Experimental Evidence from Israel.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (14): 1823–1857. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018774370

- Grudzińska-Gross, Irena. 2014. “The Backsliding.” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 28 (4): 664–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325414553886

- Hanley, Seán, and Milada Anna Vachudova. 2018. “Understanding the Illiberal Turn: Democratic Backsliding in the Czech Republic.” East European Politics 34 (3): 276–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1493457

- Hellquist, Elin. 2019. “Ostracism and the EU’s Contradictory Approach to Sanctions at Home and Abroad.” Contemporary Politics 25 (4): 393–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2018.1553083

- Hellquist, Elin. 2021. “Regional Sanctions as Peer Review: The African Union Against Egypt’ (2013) and Sudan (2019).” International Political Science Review 42 (4): 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512120935530

- Hellquist, Elin, and Stefano Palestini. 2020. “Regional Sanctions and the Struggle for Democracy: Introduction to the Special Issue.” International Political Science Review 42 (4): 437–450.

- Hobolt, Sara B., and Catherine E. de Vries. 2016. “Public Support for European Integration.” Annual Review of Political Science 19 (1): 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Homolar, Alexandra. 2011. “Rebels Without a Conscience: The Evolution of the Rogue States Narrative in US Security Policy.” European Journal of International Relations 17 (4): 705–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066110383996

- Hooghe, Liesbet. 2007. “What drives Euroskepticism? Party-public cueing, ideology and strategic opportunity.” European Union Politics 8.1 (2007): 5–12.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2020. “A Postfunctionalist Theory of Multilevel Governance.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 22 (4): 820–826. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120935303

- Hurd, Ian. 2002. “Legitimacy, Power, and the Symbolic Life of the UN Security Council.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 8 (1): 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-00801006

- Kelemen, R. Daniel. 2020. “The European Union's Authoritarian Equilibrium.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (3): 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1712455

- Kertzer, Joshua D. 2020. “Re-Assessing Elite-Public Gaps in Political Behavior.” American Journal of Political Science 66 (3): 539–553

- Kotwas, Marta, and Jan Kubik. 2019. “Symbolic Thickening of Public Culture and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism in Poland.” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 33 (2): 435–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325419826691

- Lauterbach, Fabian, and Catherine E. De Vries. 2020. “Europe Belongs to the Young? Generational Differences in Public Opinion Towards the European Union During the Eurozone Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (2): 168–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1701533

- Liberman, Peter. 2006. “An Eye for an Eye: Public Support for War Against Evildoers.” International Organization 60 (03): 687–722. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830606022X

- Liberman, Peter. 2013. “Retributive Support for International Punishment and Torture.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 57 (2): 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002712445970

- Lührmann, Anna, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2019. “A Third Wave of Autocratization is Here: What is New About It?” Democratization 26 (7): 1095–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029

- Mastenbroek, Ellen. 2005. “EU Compliance: Still a ‘Black Hole’?” Journal of European Public Policy 12 (6): 1103–1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500270869

- McLaren, Lauren M. 2006. “Attitudes to Policy-making in the EU.” Identity, Interests and Attitudes to European Integration (2006): 110–155.

- McLeish, Kendra N., and Robert J. Oxoby. 2007. ‘Identity, Cooperation, and Punishment.’ IZA Discussion Paper No. 2572.

- Mérand, Frédéric. 2022. “Political work in the stability and growth pact.” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (6): 846–864.

- Merlingen, Michael, Cas Mudde, and Ulrich Sedelmeier. 2001. “The Right and the Righteous? European Norms, Domestic Politics and the Sanctions Against Austria.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 39 (1): 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00276

- Meunier, Sophie, and Milada Anna Vachudova. 2018. “Liberal Intergovernmentalism, Illiberalism and the Potential Superpower of the European Union.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (7): 1631–1647. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12793

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39 (4): 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2013. “Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America.” Government and Opposition 48 (2): 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2012.11

- Nossal, Kim Richard. 1989. “International Sanctions as International Punishment.” International Organization 43 (2): 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300032926

- Onderco, Michal. 2017. “Public Support for Coercive Diplomacy: Exploring Public Opinion Data from Ten European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 56 (2): 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12183

- Oppermann, Kai, and Henrike Viehrig. 2009. “The Public Salience of Foreign and Security Policy in Britain, Germany and France.” West European Politics 32 (5): 925–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903064804

- Pech, Laurent. 2009. “The Rule of Law as a Constitutional Principle of the European Union.” The Jean Monnet Center for International and Regional Economic Law & Justice (NYU), Working Paper 04/09.

- Pevehouse, Jon C. 2002. “Democracy with a Little Help from My Friends? Regional Organizations and the Consolidation of Democracy the Euphoria Third Wave of Democratization Began to Survival.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (3): 611–626. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088403

- Portela, Clara. 2012. European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy: When and Why Do They Work? London: Routledge.

- Portela, Clara. 2021. “The EU Human Rights Sanctions Regime: Unfinished Business.” Revista General De Derecho Europeo 54: 19–44.

- Portela, Clara, and Jan Orbie. 2014. “Sanctions Under the EU Generalised System of Preferences and Foreign Policy: Coherence by Accident?” Contemporary Politics 20 (1): 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2014.881605

- Portela, Clara, Paulina Pospieszna, Joanna Skrzypczyńska, and Dawid Walentek. 2021. “Consensus Against All Odds: Explaining the Persistence of EU Sanctions on Russia.” Journal of European Integration 43 (6): 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1803854

- Pospieszna, Paulina, and Clara Portela. 2020. “Understanding EU Sanctioning Behavior.” Przegląd Zachodni 1: 55–70.

- Sanchez-Cuenca, Ignacio. 2017. “From a Deficit of Democracy to a Technocratic Order : The Postcrisis Debate on Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 20 (1): 351–369. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-061915-110623

- Savage, James D., and David Howarth. 2018. “Enforcing the European Semester: The Politics of Asymmetric Information in the Excessive Deficit and Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedures.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (2): 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363268

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Ulrich Sedelmeier. 2005. The Politics of European Union Enlargement: Theoretical Approaches. Abingdon and New York: Routledge Advances in European Politics.

- Schlipphak, Bernd, and Oliver Treib. 2017. “Playing the Blame Game on Brussels: The Domestic Political Effects of EU Interventions Against Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (3): 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1229359

- Seitz, William, and Alberto Zazzaro. 2020. “Sanctions and Public Opinion: The Case of the Russia-Ukraine Gas Disputes.” The Review of International Organizations 15 (4): 817–843.

- Sejersen, Mikkel. 2021. “Winning Hearts and Minds with Economic Sanctions? Evidence from a Survey Experiment in Venezuela.” Foreign Policy Analysis 17 (1): 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/oraa008

- Sjoberg, Laura. 2006. Gender, Justice, and the Wars in Iraq: A Feminist Reformulation of Just war Theory. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Soyaltin-Colella, Digdem. 2020. “(Un)Democratic Change and Use of Social Sanctions for Domestic Politics: Council of Europe Monitoring in Turkey.” International Political Science Review 42 (4): 484–500.

- Stein, Rachel M. 2015. “War and Revenge: Explaining Conflict Initiation by Democracies.” American Political Science Review 109 (3): 556–573. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055415000301

- Taggart, Paul. 1998. “A Touchstone of Dissent: Euroscepticism in Contemporary Western European Party Systems.” European Journal of Political Research 33: 363–388.

- Vachudova, Milada Anna. 2005. Europe Undivided. Democracy, Leverage, and Integration After Communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vachudova, Anna Milada. 2020. “Ethnopopulism and democratic backsliding in Central Europe.” East European Politics 36.3 (2020): 318–340.

- Van der Veer, Reinout Arthur 2021. “Audience Heterogeneity, Costly Signaling, and Threat Prioritization: Bureaucratic Reputation-Building in the EU.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31 (1): 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa030

- Van der Veer, Reinout Arthur 2022. “Walking the Tightrope: Politicization and the Commission's Enforcement of the SGP.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 60 (1): 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13272

- van Elsas, Erika J., Anna Brosius, Franziska Marquart, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2020. “How Political Malpractice Affects Trust in EU Institutions.” West European Politics 43 (4): 944–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1667654

- Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem 2018. The Moral Punishment Instinct. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Verbeek, Bertjan, and Andrej Zaslove. 2017. “Populism and Foreign Policy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy, 384–405. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Versluis, Esther. 2007. “Even Rules, Uneven Practices: Opening the ‘Black Box’ of EU law in Action.” West European Politics 30 (1): 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380601019647

- Wagner, Wolfgang. 2014. “Rehabilitation or Exclusion? A Criminological Perspective on Policies Towards ‘Rogue States’.” In Deviance in International Relations: ‘Rogue States’ and International Security, edited by Wolfgang Wagner Wouter Werner, and Michal Onderco, 152–170. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Wagner, Wolfgang, and Michal Onderco. 2014. “Accommodation or Confrontation? Explaining Differences in Policies Towards Iran.” International Studies Quarterly 58 (4): 717–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12116

- Weber, P. M., and G. Schneider. 2020. ‘Post-Cold War Sanctioning by the EU, the UN, and the US: Introducing the EUSANCT Dataset’. Conflict Management and Peace Science. Online first.

- Wodak, Ruth. 2015. “The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean.” The Politics of Fear (2015): 1–256.

- Youngs, Richard. 2009. “Democracy Promotion as External Governance?” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (6): 895–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760903088272

- Youngs, Richard. 2010. The European Union and Democracy Promotion: A Critical Global Assessment. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Zhelyazkova, Asya, and René Torenvlied. 2009. “The Time-Dependent Effect of Conflict in the Council on Delays in the Transposition of EU Directives.” European Union Politics 10 (1): 35–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116508099760