ABSTRACT

Following Russia's invasion, Ukraine exemplifies presidential leadership during full-scale war. This study examines executive coordination from Zelenskyi's mid-2019 election to the February 2022–July 2023 war period, using media sources and official data. It introduces three new leadership models – figurehead-leader, arbiter-management and leader-implementer – to capture evolving intra-executive relations in semi-presidential systems. Power centralisation around the president has accelerated, fitting the leader-implementer model. However, in accordance with the arbiter-manager model, a stricter division of labour, especially in domestic policy, is evident. Despite semi-presidentialism's perceived conflict-proneness, the study shows it can function efficiently and allow executive flexibility during significant crisis.

Introduction

Following Russia’s brutal invasion in February 2022, Ukraine provides an unsolicited case of executive leadership during conditions of a full-scale war. From presidential regimes, in particular the United States, we know that in times of war, the president’s power increases significantly through a rally-round-the-flag effect of citizen support and the centralisation of power as extraordinary procedures and emergency powers come into effect (Devine et al. Citation2020; Kassop Citation2003). Similarly, crises and war in parliamentary systems tend to concentrate powers in the hands of the prime minister and the government (Chowanietz Citation2010; Raunio and Wagner Citation2017).

In semi-presidential regimes, however, where a popularly elected president shares executive power with a prime minister, the situation is less obvious. In semi-presidential countries where presidential powers are weak, such as Finland and Slovakia, the prime minister tends to be the focal point of executive leadership also during crisis – as observed for example during the financial crisis 2008–2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic 2020–2022 (Nemec Citation2021; Peters Citation2011), while in semi-presidential countries where presidential powers are stronger, such as France, the president tends to dominate the executive scene also during extraordinary situations such as COVID-19 (Benamouzig Citation2023). A recent study on Taiwan during COVID-19, moreover, suggests that the division of powers between the president and prime minister can become more distinct during a crisis. According to Yan (Citation2023), the president focused primary on foreign affairs and defence, while the government wielded greater discretionary power in handling epidemic prevention measures and addressing internal affairs. Yet, the literature on semi-presidentialism in the context of crisis is scarce, and, from what we know, non-existent in the context of full-scale war (cf. Åberg and Sedelius Citation2020).

Alongside Armenia, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine changed its post-Soviet constitution in the wake of popular uprisings (2004 and 2013), shifting from a president-parliamentary model of extensive presidential powers and a government accountable to both the president and the parliament, to premier-presidentialism where a directly elected but weaker president shares executive power with a cabinet exclusively dependent on parliament for survival (Elgie Citation2011; Shugart Citation2005). It is also during the formally weaker presidency (2006–2010 and 2014 onwards) that Ukraine has experienced significant improvements in the level of democracy (Nations in Transit Citation2022; V-Dem Citation2023). Yet, Ukrainian politics has faced several challenges including presidents that have, frequently, fallen prey to autocratic tendencies (Choudhry, Sedelius, and Kyrychenko Citation2018); a fragmented and weak party system that has undermined the capacity of the legislature to act coherently (Krol Citation2021) and a fragile constitutional culture, manifested by irregular, politically motivated constitutional reforms (Fruhstorfer and Hein Citation2016). Many of these challenges have surfaced in recurring political infightings between president, parliament and government (Hale and Orttung Citation2016).

Against this background of turbulence, the landslide victory of President Volodymyr Zelenskyi and his party, Servant of the People, in the 2019 elections provided favourable conditions for governance with a unified executive backed by a strong one-party parliamentary majority – something that none of Ukraine’s previous presidents had enjoyed. As a result, and despite the constitutionally weaker presidency since 2014, the scene was set for strong presidential leadership already before the full-scale invasion. Similar to unified government in France, the prime ministers appointed by Zelenskyi (first Oleksiy Honcharuk and then Denys Shmyhal) and the government were expected to implement the president’s programme.

This study addresses the following research question: how has executive coordination in Ukraine been (re-)organised during the full-scale war and how has this influenced the balance of executive power between the president and his office on the one hand, and the prime minister and government on the other? In addition to analysing formal changes in institutional structures and procedures, it uncovers interaction between key actors within the president’s office – an institution of substantial influence already prior to the war – and its relation to other executive units. While also acknowledging the substantial role of the legislature, this study mainly focuses on intra-executive relations between the president and the government.

Our study contributes to research on semi-presidentialism through an in-depth examination of the dynamics of executive power and decision-making during a major crisis. On the one hand, it represents an extreme scenario, involving a full-scale invasion where the survival of the Ukrainian state has been at stake. One could hence argue that the case has limited relevance beyond Ukraine, contending that a war threatening the survival of the state is markedly different from other crises, such as an economic crisis or a pandemic. On the other hand, we demonstrate that the findings observed in Ukraine regarding the balance between the president and the government carry implications for our understanding of the strengths and weaknesses inherent in a dual executive structure under maximum pressure. On a more general level, the study engages with questions of wartime leadership and governance, a relevant topic regardless of regime type.

Theoretically, our key contribution is that we outline and apply a new conceptualisation to distinguish between three different leadership models – figurehead-leader, arbiter-manager and leader-implementer. These labels are used to characterise the relationship between the president and prime minister in premier-presidential and president-parliamentary regimes. Our findings, based on two main hypotheses, indicate that the conditions of war accelerated a pre-existing tendency in Ukraine towards a leader-implementer dynamic centralising powers around the president at the expense of the prime minister. Yet, the war has also compelled a stricter division of labour, where the president, in accordance with an arbiter-manager dynamic of semi-presidentialism, accepts that the main responsibility for domestic policy rests with the prime minister. These conceptual labels require further elaboration in future studies, but we assert that they hold potential beyond the case of Ukraine for developing more fruitful typologies of leadership relations in semi-presidential regimes.

The theoretical framework in the next section first introduces the leadership models before discussing executive coordination during times of crisis and war and proposing two guiding hypotheses. Following a section on method and data, we contextualise our case study of Ukraine, providing basic indicators and political conditions. The empirical section focuses on executive coordination and division of policy domains, with a distinction between Zelenskyi’s presidency before (2019–2021) and during (2022–2023) the full-scale war. We specifically examine the key institutions involved in executive governance and analyse the distribution of powers between the president and his administration on the one hand, and the prime minister and government on the other. Finally, we summarise our main findings.

Theoretical framework

Semi-presidentialism and leadership models

By adopting a pragmatic new institutional approach, we assume that institutions generate behavioural predispositions, inducing certain regularities and thereby reducing the level of causal complexity (Elgie Citation2018). At the same time, a reasonable expectation is that during extreme political events such as wars, the institutional rules and roles provide the framework, but individual political leaders’ personal capacities and actions acquire particular importance. Under such circumstances, there are reasons for researchers to prioritise agency over institutions. Thus we have already seen several studies of Zelenskyi’s leadership during the war, including more journalistic investigations (e.g. Bryzhko-Zapur Citation2023; Derix and Shelkunova Citation2023; Rudenko Citation2022; Shuster Citation2024; Urban and McLeod Citation2022) and Zelenskyi’s rhetoric and communication strategies (Ash and Shapovalov Citation2022; Serafin Citation2022; Viedrov Citation2022; Yanchenko Citation2022), while others have focused on the broader context of the Russian–Ukrainian war (D’Anieri Citation2023; Kuzio and Jajecznyk-Kelman Citation2023; Plokhy Citation2023) and its relationship to Zelenskyi’s presidency (Onuch and Hale Citation2023; Pisano Citation2022; Reichardt and Stępniewski Citation2022).

Following recent studies on presidential activism in semi-presidential countries, our theoretical starting point is to underline agency, particularly that of the presidents. It is well established in the literature that there can be notable discrepancy between the letter of the constitution and actual use of presidential powers, with much depending on the political cultures of the respective semi-presidential countries. Particularly in less institutionalised contexts, such as Ukraine, agency should matter more as the president is less constrained by various formal and informal rules (Brunclík et al. Citation2023; Elgie Citation2018; Grimaldi Citation2023; Köker Citation2017; Raunio and Sedelius Citation2020). As a result, we are interested in how the dual institutional structure between the president and the government has actually operated in Ukraine during the war, both in terms of leadership and the division of responsibilities within domestic politics on one hand, and foreign, security, and defence policies on the other.

Adhering to a commonly applied framework, there are two main subtypes of semi-presidentialism: (a) president-parliamentary, where both the legislature and the popularly elected president have the authority to dismiss the prime minister; and (b) premier-presidential, where only the legislature, but not the popularly elected president, has the power to dismiss the prime minister (Shugart Citation2005). Beyond the power of cabinet dismissal, president-parliamentary constitutions usually provide the president with quite extensive powers to influence both domestic and foreign and defence policy. Premier-presidential constitutions, on the contrary, usually provide for a more balanced distribution of power where the president’s influence is predominantly confined to foreign, security and defence, whereas the prime minister is the main director of domestic policy.

Both subtypes leave considerable room for agency. An underlying constitutional notion of semi-presidentialism is that the roles of the president and the prime minister should be complementary and clearly delineated. In practice, however, the separation of their roles is rarely straightforward, as policy domains tend to overlap and as the two executives – mainly the president – often strive for influence beyond their defined power spheres. As mentioned above, this built-in potential for conflict is higher in countries with lower levels of institutionalisation (e.g. Ukraine), where the distribution of authority is more dependent on contextual factors. And indeed, intra-executive conflict over policy domains has been a frequently occurring phenomenon in especially younger semi-presidential regimes (Elgie Citation2018; Kudelia Citation2018; Moestrup and Sedelius Citation2023; Sedelius and Mashtaler Citation2013; Yan Citation2021).

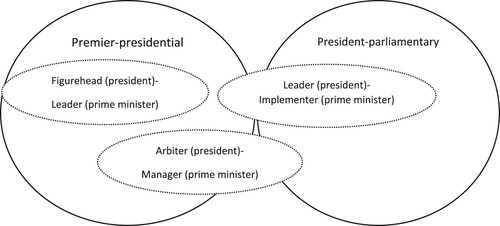

Still lacking in the literature, however, are useful labels for categorising relations between the president and prime minister within the two subtypes of semi-presidentialism. In , we therefore attempt to categorise the relationship into three ideal-type models: figurehead-leader, arbiter-manager and leader-implementer. This conceptualisation provides the framework for examining power-sharing within dual executives, both according to the constitution (de jure) and in practice (de facto). A constant challenge in the literature on semi-presidentialism revolves around understanding the difference between constitutional and actual power distribution. While the distinction between premier-presidentialism and president-parliamentarism indicates the constitutional form of semi-presidentialism, our typology offers the opportunity to demonstrate how three different leadership models can occur both within and between these two sub-types. is tentative, and our labelling is a modified version of partly different labels used by Choudhry and Stacey (Citation2014) and Choudhry, Sedelius, and Kyrychenko (Citation2018).Footnote1

Figure 1. Models of president-prime minister relations in semi-presidential regimes. Source: Authors’ elaboration partly based on Choudhry, Sedelius, and Kyrychenko (Citation2018, 51–52).

An institutional option that can mitigate the risk of intra-executive conflict is to constitutionally establish weaker presidential powers, adopting a figurehead-leader model where the president serves as a little-more-than ceremonial head of state with limited and mainly representative responsibilities related to foreign and security policy. This is a constitutional model employed in several premier-presidential countries in Central and Eastern Europe, such as in Bulgaria, Slovakia and Slovenia. However, in the post-Soviet context of weak parties and an inherent norm of strong presidential leadership, the figurehead-leader model has not been preferred. Ukraine’s premier-presidential constitution as established by amendments in 2004 and again in 2014 rather outlines an arbiter-manager model granting the president and prime minister overlapping but complementary powers (see below). According to this model, the president focuses on foreign and defence policy, while the prime minister takes the lead in domestic matters, with the president, if needed, exercising an arbitration role in these domains to ensure the efficient functioning of government. Such a model is found in, e.g. Lithuania, Portugal and Romania (cf. Amorim Neto and Anselmo Citation2023; Raunio and Sedelius Citation2020). For example, the Romanian constitution (Art 80:2) assigns the president “to guard the observation of the Constitution and the proper functioning of the public authorities” and “to act as a mediator between the Powers in the State”.

However, in practice and driven by an implicit norm of strong presidential leadership among elites and the population, Ukraine has predominantly followed a leader-implementer logic, where the president is perceived as the ultimate authority in both foreign and domestic policy, and the government is expected to implement the president’s agenda. This model was formally envisioned in Ukraine’s president-parliamentary constitution (1996–2006, 2010–2014, during Kuchma’s and Yanukovych’s presidencies), where the government’s actual subordination to the president was crucial for its political survival (cf. Protsyk Citation2003, Citation2006). However, even under the premier-presidential constitution (2006–2010, 2014-, during Yushchenko’s, Poroshenko’s, and Zelenskyi’s presidencies), and regardless of parliamentary majorities, presidents have strived for executive leadership, leading to recurring conflicts among the president, prime minister and parliament (cf. Kudelia Citation2018).

Thus a constitution may prescribe an arbiter-manager model, as in the cases of, e.g. Moldova, Romania and Ukraine, but in practice operate according to the leader-implementer logic, where the prime minister is clearly subordinated to the president’s actual leadership, even in areas constitutionally assigned to the prime minister. Several factors may facilitate development in the direction of a leader-implementer practice of premier-presidentialism. These include executive unity, where the president and prime minister belong to the same political camp (non-cohabitation), a strong parliamentary majority supporting the president, and presidential influence over the leading party in parliament (Passarelli Citation2015; Samuels and Shugart Citation2010). The strong popular mandate and the countrywide victory of Zelenskyi and his party, Servant of the People, in the 2019 elections met these criteria, resulting in a situation where a unified executive was backed by a strong one-party parliamentary majority.Footnote2

Crisis, war and centralisation of executive leadership

Boin and ‘t Hart (Citation2012, 179) define crisis as “when a threat is perceived against the core values or life-sustaining functions of a social system, which requires urgent remedial action under conditions of deep uncertainty”. This definition aptly applies to Ukraine’s situation with Russia's invasion. During times of war, the executive not only has more autonomy but also finds it easier to navigate policies through the legislature where members of parliament themselves may understand the urgency of the situation and allow the executive more discretion (Raunio and Wagner Citation2017). Party-political contestation is set aside and presidents benefit from their role as head of state standing above political parties. International crises thus bring about, at least temporarily, a “rally-around-the-flag” effect that makes criticism of the executive look inappropriate (Mueller Citation1973; Oneal, Brad, and Joyner Citation1996), leaving also more room for agency by the president. Considering the pre-existing tendency in Ukraine towards a leader-implementer model along with an institutional context characterised by one-party majority and strong popular mandate for Zelenskyi, and recognising that the president’s primary domains of foreign affairs and defence are particularly prominent during a military invasion, we establish our first hypothesis regarding executive empowerment:

H1: The full-scale war in Ukraine has accelerated centralisation of executive governance and powers around the president, thereby further strengthening the president’s executive leadership over the prime minister and government and enhancing a leader-implementer model of semi-presidentialism.

A stricter division of policy domains during war?

Examining semi-presidentialism and executive coordination is ultimately research about leadership. Coordination can take various forms, ranging from formal rules to informal conventions and ad hoc practices. Coordination can occur bilaterally between the president and the prime minister, as well as between their respective offices and political advisers. The level of coordination can also vary across different policy sectors, with foreign and security policies being domains where both the president and the prime minister typically share powers, and where countries are expected to present a unified front in external relations (Helms Citation2012; Rhodes and ‘t Hart Citation2014). Typically, countries utilise specialised coordination mechanisms for these policy areas, such as ministerial committees or defence councils that bring together representatives from political leadership, bureaucracy, and armed forces to regularly review security developments (Drent and Meijnders Citation2015; Raunio Citation2016).

A key challenge for political executives in times of crisis is to achieve effective communication and collaboration among networks and institutions, often including international actors. Executives need to prioritise and focus on the most important decisions. Effective coordination therefore requires that leaders at the core executive level (e.g. president, prime minister, other ministers) avoid micromanaging processes, particularly those less related to the crisis. Otherwise, the executive will be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of communication and urgent demands (‘t Hart, Rosenthal, and Kouzmin Citation1993). Hence, the executive needs to strike a functioning balance between demonstrating executive leadership and control, which is expected by the public at a time of crisis, while at the same time accepting a significant level of delegation to other actors.

Somewhat paradoxically then, the overwhelming demands on the dual executive during a war may necessitate a stricter division of labour where the president focuses more strictly on foreign and defence policies while the main responsibility for directing domestic policy rests with the prime minister and the government. Yan (Citation2023, 164) found that during COVID-19 in president-parliamentary Taiwan, there was a shift of actual power within the executive where “the president remained in charge of foreign affairs and defence, whereas the prime minister was granted more discretionary power to deal with epidemic prevention measures and other internal affairs” and that this shift of power allowed the president “to play the role of checks and balances in resolving executive overreach, […] which in turn helped the government to respond quickly to the crisis” (Citation2023, 148).

By allowing the government to take the lead in domestic issues, while the president focuses on defence, security, and foreign policy, a division of labour can be established that promotes effective leadership. Such a stricter division of labour aligns with the arbiter-manager model of premier-presidentialism where the president serves as an arbiter of the government’s domestic policy while the prime minister functions as the manager, retaining control over domestic programmes. Hence, we hypothesise that:

H2: The urgent and overwhelming demands on the presidency during the war in Ukraine have necessitated a stricter division of labour, where the president, in accordance with an arbiter-manager model of semi-presidentialism, accepts executive power-sharing where the main responsibility for directing domestic policy rests with the prime minister.

Data and method

To analyse changes related to our main hypotheses, our case study compares two periods: first, more briefly, from Zelenskyi’s election in mid-2019 until the end of 2021, and second, the initial one and half year of the full-scale war spanning from February 2022 to July 2023. We examine two sets of factors, tracking the roles, interrelations and activities of key executive actors:

Procedures and institutions: This encompasses key executive bodies, including specific war regulations. We highlight how the presidential administration and its interactions with government ministries have been influenced by the war.

Policy domains: We assess the impact of the war on the division of labour between the president and the government in the domains of foreign, defence and security policy on one hand, and domestic policy on the other. It is crucial to note that the line between foreign and security issues and domestic policy is often blurred, particularly in the context of war. Presidents tend to frame certain issues as foreign or security threats through a process known as “securitisation” in international relations literature (Waever Citation1995) to circumvent restrictions on their influence over domestic policy (Howell, Jackman, and Rogowski Citation2013; Milner and Tingley Citation2015). When referring to domestic policy, we consider matters such as reconstruction, social and economic needs, education, civil health care, housing and transportation. Although these issues are also embedded in Ukraine’s foreign relations during wartime, they are here categorised within the domestic policy sphere, distinct from matters related to military defence and security.

Our data consists of media analyses and news updates, expert comments, reports from direct interviews with high-ranking officials and state bodies’ official data. We recognise the inherent challenges in tracing issues related to informal politics, particularly during times of war and heightened secrecy. We rely quite extensively on analytical articles from “Ukrainska Pravda”, considered among the top three media outlets in Ukraine.Footnote3 This media outlet draws upon insider sources, includes anonymous comments from high-ranking officials, conducts interviews with Ukrainian politicians and frequently engages in investigative journalism. Other sources include Ukrainian think tank reports, results of journalistic investigations and reviews by foreign analytical centres. For the sources in Ukrainian, we provide English translations of key quotes in the running text and English titles in the references.

Context: semi-presidential shifts in Ukraine

After gaining independence, Ukraine adopted a president-parliamentary constitution in 1996. However, in the aftermath of the Orange Revolution, the constitution was amended in 2004 to a premier-presidential system, which was in effect between 2006 and 2010. Subsequently, in October 2010, the Constitutional Court nullified the 2004 constitutional amendments on procedural grounds, leading to a return to the president-parliamentary system from 2010 until 2014. The Euromaidan protests in 2013–14 resulted in the re-enactment of the nullified 2004 amendments, bringing back the premier-presidential system in early 2014. The fluctuations between these two forms of semi-presidential government have centred on the power balance between the president and prime minister, with ongoing debates and calls for further constitutional reforms (Sedelius and Berglund Citation2012). Following the repeated constitutional shifts, Ukraine has also moved back and forth along a continuum between democracy and autocracy (Hale and Orttung Citation2016). Since 2014, Ukraine has experienced diminished levels of intra-executive conflict in contrast to earlier periods when tensions between the president and prime minister were very frequent (cf. Sedelius and Mashtaler Citation2013).

reports presidential power scores for 11 semi-presidential countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Prior to the 2004 constitutional reforms, the Ukrainian president had extensive powers including appointing and dismissing the prime minister, cabinet members and local administration heads (with parliamentary consent). However, with the adoption of the premier-presidential system, the parliament became the primary institution determining the government’s activities, resulting in significant curtailment of presidential powers. Consequently, Ukraine’s aggregated presidential power scores now align with those of, e.g. Lithuania, Poland and Romania.

Table 1. Shugart and Carey’s presidential power scores in semi-presidential countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

The reformed Ukrainian constitution assigns foreign affairs, security and defence policies to the president, while domestic policy falls under the government’s jurisdiction. Only the Minister of Defence and Minister of Foreign Affairs are proposed by the president, while the prime minister forms the rest of the government. However, the constitution still includes norms that result in overlapping powers between the president and the government. This potential for intra-executive conflict has been criticised by the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission Citation2010). For instance, the constitution explicitly designates the president’s responsibilities for national security (article 106 § 1), foreign policy and international relations (106 § 3), and the appointment and dismissal of diplomats and officials (106 § 5). At the same time, the constitution assigns responsibility to the Cabinet of Ministers (led by the prime minister) for the implementation of domestic and foreign policies (116 § 1), defence and national security (116 § 7), and foreign economic activity (116 § 8).

The president’s formal powers, combined with a political norm that grants the president principal decision-making authority in areas of shared responsibility, have resulted in a system where the president often functions as the de facto chief executive in both foreign and domestic policies. This was particularly evident under the president-parliamentary constitution but has also been the norm under the premier-presidential system. Presidential dominance has been reinforced by the influential role of the presidential administration.Footnote4 As the constitution does not provide explicit regulations or detailed functions for this body, its authority is established through presidential decrees. Consequently, the presidential administration has exerted significant control in areas of shared responsibilities. In addition, Ukrainian presidents have often leveraged their influence through entities subordinated to or appointed by the president, such as the National Security and Defence Council, General Prosecutor’s Office, Security Service of Ukraine and other similar bodies (Choudhry, Sedelius, and Kyrychenko Citation2018).

Empirical analysis

Executive coordination during Zelenskyi’s pre-war period 2019–2022

Zelenskyi’s presidential campaign in 2019 relied heavily on positioning himself as the champion of “the people” against the “old elites” (Mashtaler Citation2021). Zelenskyi proclaimed that appointments would be based on merit rather than on personal connections. However, the power structure surrounding Zelenskyi largely consisted of his colleagues and friends from show business industry (BIHUS Info Citation2021). Members of his comedy troupe “Kvartal 95” formed the backbone of his headquarters during the election campaign. Among these were Andriy Bohdan, who led Zelenskyi’s campaign and was subsequently appointed as the Head of the Presidential Office, Dmytro Razumkov, who became the Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada (the parliament) after the parliamentary elections, and Zelenskyi’s two close friends, Serhiy Shefir and Ivan Bakanov, who respectively were assigned as the First Assistant to the President and the Head of the Security Service of Ukraine.

Presidential Office renewal and internal tensions 2019–2020

Zelenskyi’s changes in the Presidential OfficeFootnote5 went beyond just renaming institutions – significant shifts in management style and mechanisms were introduced, compared to the previous administration under President Petro Poroshenko. In contrast to Poroshenko, Zelenskyi did not initially organise daily staff meetings. Instead, he invited people to address specific issues and held “brainstorming” sessions with his closest aides, including Shefir, Bohdan, Andriy Yermak, the President’s Aide of Foreign Policy, and the first Deputy Head of the Presidential Office, Serhiy Trofimov (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2019). Bohdan played a key role in setting up the administrative machinery (Romaniuk and Kravets Citation2020a), and Zelenskyi made the main personnel decisions together with Bohdan and Shefir in the first months after the presidential elections (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2019).

The end of 2019 and the beginning of 2020 saw a significant deterioration in the relationship between Zelenskyi and Bohdan. Jokes began circulating that Zelenskyi was merely “working as a president in the Office of Andriy Bohdan” (Reshchuk and Buderatskyi Citation2020). Meanwhile, the consistent presence and successful handling of foreign affairs made Yermak a very influential figure in the president’s inner circle. Subsequently, in mid-February 2020, Bohdan was replaced by Yermak as the new Head of Presidential Office (Romaniuk and Kravets Citation2020b). Media outlets described Bohdan and Yermak as having very different management styles, with Bohdan more hands-on and adversarial while Yermak preferred to solve issues quietly and with minimal public tension (Romaniuk and Kravets Citation2020c). As a result, most important appointments since 2020 have been initiated and organised by Yermak.

Two governments: from “young reformers” to “experienced managers”

After the parliamentary elections of July 2019, the government was headed by Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk, aged 35, who at the time of his appointment was the first Deputy of the Presidential Office. According to one of Zelenskyi’s representatives, Honcharuk was appointed because he agreed to be part of Zelenskyi’s strategy aiming at achieving fast victories (Lukashova and Kravets Citation2019). The government led by Honcharuk underwent restructuring: while the previous government (under Volodymyr Hroisman) had 19 ministries and 25 ministers, this new government had 15 ministries and 17 ministers (Ukrainska Pravda Citation2019). Despite high ambitions, in January 2020, a scandal erupted when an audio recording of Honcharuk was leaked, in which he allegedly described the president as having limited knowledge of how the economy works (Sorokin Citation2020). As a result, Honcharuk submitted his resignation, which was initially not accepted by the president, but eventually confirmed in March 2020.

Denys Shmyhal, who took over as prime minister in March 2020, had previously served as the vice prime minister in Honcharuk’s cabinet. The composition of the new government was a mix of old and new team members, and the appointment of some ministers was perceived as chaotic, indicating a shortage of qualified staff and a lack of clear reform priorities from the president (Iwański et al. Citation2020). Shmyhal positioned himself as an administrator who focuses on implementing policies and routine work. In his words, “I did not come to this position as a politician from the classical Ukrainian political circles who worries about their ratings, PR-actions, or other things. I am more focused on work” (Musaieva and Romaniuk Citation2020). The change of government was an attempt to defuse negative sentiments that had been building up in the Ukrainian society. Also, the COVID-19 was a major challenge. As Ukraine did not receive the initially scheduled support from the International Monetary Fund in spring 2020, there was a pressing need to stabilise the economy and ensure greater consistency in reform efforts. Consequently, the president sought a more experienced manager than Honcharuk (Musaieva and Romaniuk Citation2020).

Reform agenda and policy priorities 2020–2021

In 2020–21, the government’s agenda included a spectrum of issues related to the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. In parallel, the president’s agenda placed significant emphasis on de-oligarchisation and anti-corruption efforts (Minakov Citation2022). In terms of foreign affairs, a significant initiative was the establishment of the Crimea Platform. This international coordination mechanism was officially established in August 2021 with the goal of uniting the international community in efforts to address de-occupation of Crimea. One of the president’s most important infrastructure initiatives was the so-called “Big Construction”, aimed at improving the country’s roads, bridges and other critical civilian infrastructure. However, according to political analysts, “the lack of experience, public scandals, relentless conflicts with older politicians and oligarchs, and the COVID-19 pandemic forced Zelensky to change his policies and slow the pace of reforms” (Minakov Citation2022).

The Agency of Legislative Initiatives, a Ukrainian think tank monitoring the legislative process, observed a decline in Zelenskyi’s legislative initiatives as his presidency progressed. Additionally, there was a noticeable decrease in the number of laws adopted under the government’s initiative as compared to the previous administration (Agency for Legislative Initiatives Citation2020). In 2020, the parliament did not support the program of the Shmyhal government and in 2021, the government did not present a new program. As a result, the government primarily relied on the president’s electoral program for its activities, which effectively consolidated superiority of the president’s policy agenda (Analytical portal “Slovo i dilo” Citation2022). In addition, the National Security and Defence Council was used actively by Zelenskyi to promptly adopt collective decisions convenient to the president. As noted by journalists (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2021), in 2021 this body functioned as an “office of simple decisions”, particularly in response to perceived internal threats or political rivals. For example, the imposition of sanctions against oligarchs (including the former president, Poroshenko) served to achieve such objectives.

Executive coordination during the full-scale war: February 2022–July 2023

Navigating crisis: institutional reorganisation and emergency tools

“I am not Yanukovych; I will not flee anywhere”, Zelenskyi said at a press conference in November 2021 (Analytical portal “Slovo i dilo” Citation2021). In February 2022, in response to an offer from Western colleagues to move to a safer place beyond Ukraine after the onset of full-scale invasion, he said, “I need ammunition, not a ride”. Faced with an existential conflict that threatened the existence of the Ukrainian state, authorities at all levels and society as a whole united in their resistance against the invading enemy.

Importantly, the government continued to work despite the chaos following Russia’s invasion; the parliament maintained its constitutional majority, with over 300 MPs continuing to participate in the plenary sessions. The government was purposely divided into two parts – those who stayed in the capital and another part working primarily from Western UkraineFootnote6 (Komarov Citation2023). When Kyiv’s outskirts were subsequently liberated from Russia in the beginning of April 2022, the staff of the Cabinet of Ministers was asked to return to Kyiv, and the working process returned closer to its usual framework (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2022a).

An emergency regime was introduced already on February 23 followed by martial law the next day, which placed restrictions on certain constitutional rights and freedoms of citizens and streamlined specific procedures (Dorontseva Citation2022). For instance, it facilitated simplified processes in areas such as public procurement, including defence-related procurements that were previously subject to stricter – including parliamentary – control (Ivanov Citation2022). Furthermore, it simplified appointment procedures for positions in public service and expedited the issuance of authorisation documents for construction and other services. The martial law also strengthened central executive control over the regions. This involved establishing military administrations in each region. Coordination at the local level was overseen jointly by government representatives and the Presidential Office. An advisory body, the Congress of Local and Regional Activities under the President of Ukraine, created a year earlier, in February 2021, additionally served as a platform for joint communication.

On February 24th, Zelenskyi signed a decree creating the special body the Staff of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief (“Stavka”).Footnote7 The purpose of this body is strategic management of the Armed Forces and other state military units for the period of martial law. Its legal regulations were developed already in 2017, but after the beginning of the full-scale war the president ended by decree the operation of the Military Cabinet under the National Security and Defence Council and decided on the composition of Stavka. It included the prime minister, Speaker of Parliament, Head of the Presidential Office, Head of the National Security and Defence Council, heads of law enforcement bodies, and some ministers. During the war, Stavka became the main body for collective defence-related decisions.

From the beginning of the invasion, the Presidential Office intensified its focus on communication. An essential element of Zelenskyi’s communication involved daily addresses to citizens to promote unity among the population. Additionally, to ensure coherent communication and a firm international position, the “United News” TV marathon was introduced. This initiative not only harmonised official messages but also granted Zelenskyi control over media accessibility, allowing him also to counter his political opponents (Kravets Citation2022).

Managing an overburdened presidency: prioritising and allocating policy domains

The full-scale war brought about significant changes in administration, which aimed at facilitating close interaction between the Presidential Office and the government. Before the war, the government used to align most of its initiatives with the Presidential Office. However, the war demanded accelerated decision-making at all levels and already in the initial days, Zelenskyi and Shmyhal agreed that the president should concentrate on defence and international relations, while the prime minister should take charge of “operational issues” (Romaniuk and Popadiuk Citation2023). According to Yermak (Romaniuk Citation2022a), the president sometimes had up to 10 rounds of negotiations per day in the first months of the war in addition to numerous appeals to the international community. The president’s attention primarily gravitated toward three key areas: (1) foreign affairs; (2) defence; (3) economic policy and restoration issues (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2022b). The president, along with the Presidential Office, typically operated as the central hub, coordinating activities with other executive institutions. Usually, such cooperation involved working teams focused on specific areas, comprising representatives of the Presidential Office, government and parliamentary committees.

Despite Prime Minister Shmyhal’s primary focus on domestic policy, he also engaged in a series of foreign visits, as agreed upon with the president. The urgent restoration of damaged infrastructure and the vision for the country’s future reconstruction became a main task for both the prime minister, government and the president’s team. The government’s plans regarding reconstruction (U-24), presented in the beginning of April 2022, were followed by the creation of a special body, the National Council for Recovery of Ukraine from the War, which became an advisory unit under the president. It was headed by Shmyhal and Head of Presidential Office Yermak and its tasks included developing strategies and action plans for post-war reconstruction, economic recovery and support of vulnerable groups. To develop a vision of future economic policy, two groups were working in the president’s environment: one group focused on developing proposals for public administration reform, deregulation and tax reduction, and a second group focused on developing proposals for legislative initiatives (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2022a). In June 2022, Zelenskyi also initiated a national fundraising platform “UNITED24”, for cooperation with charitable foundations, international and individual donors. An agenda for Ukraine’s reforms and reconstruction was discussed at several international gatherings. In December 2022, these activities were further continued by the establishment of a new ministry, the Ministry for Communities, Territories and Infrastructure Development of Ukraine (briefly labelled “the Ministry of Restoration”), by merging two existing ministries (Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine Citation2022). In addition to addressing challenges arising from the war, the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement remained a central aspect of Ukraine's domestic policy, as it has been since its signing in 2014. Despite the war, the government persistently worked towards fulfilling the commitments: by the end of 2021, the progress in implementing the agreement had reached 63%, and by the end of 2022, it had increased to 72% (Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine Citation2023).

Analysts from the Agency for Legislative Initiatives (Citation2022) have raised concerns about a legislative practice which has emerged during the war. By stuffing various policies under a single topic, laws sometimes include provisions that exceed ordinary legislative norms, thereby extending the constitutional powers provided to specific institutions. One notable example is the law № 2259-ІХ “On introducing changes to some laws of Ukraine on functioning a public service and local self-government under the martial law” (adopted on 12 May 2022). This law de facto expanded both the president and parliament’s authority in appointing and dismissing officials, despite constitutional power changes being prohibited during martial law. Simultaneously, experts observed that the second half of the year following the February invasion witnessed an augmentation of the Cabinet of Ministers’ role in initiating laws. 30% of the adopted draft laws during this period were instigated by the government, the highest percentage since 2019. This trend somewhat reflects the role envisaged for the government in a premier-presidential system (Agency for Legislative Initiatives Citation2023).

Despite Zelenskyi’s active involvement in economic and restoration policy, his main focus has been on defence and foreign affairs. As a result, the government and parliament have been granted more room for independent initiatives. As members of the presidential team explained in the summer of 2022, “now there is a single logic – to run faster to win faster. That’s why the president expects new meanings and new initiatives from the Cabinet of Ministers. [Zelenskyi] has outgrown his old government. He needs a team capable of working at a higher level” (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2022c). The president’s style of governance also underwent a gradual transformation, shifting from team-based discussions to independent decision-making and assertively demanding the implementation of decisions (Kravets Citation2023). At the same time, the war seems to have safeguarded Shmyhal’s position as prime minister. As a member of the Presidential Office explained, “Denys [Shmyhal] has a firm grip on the bureaucracy; he manages to expedite certain issues or solve them immediately. When we call Denys in the morning with a request to adopt something by the government, we have the decision by the evening. He clearly understands his subordination to the Presidential Office and does not refuse” (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2023).

Cooperation between the president and military personnel serves as an example of delegating functions to military specialists. As Time Magazine noted in an article with Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, General Zaluzhnyi in September 2022, “He [Zelenskyi] doesn’t need to understand military affairs any more than he needs to know about medicine or bridge building”, Zaluzhny says” (Shuster and Bergengruen Citation2022). Zaluzhnyi’s strong support among Ukrainians even positioned him as a potential political rival in the eyes of the president’s circle, leading to more tense cooperation between Zaluzhnyi and the president (Skorkin Citation2023). The government has also collaborated with private businesses and volunteer networks to address urgent issues. Volunteer engagement in various logistical chains, especially in assisting the army, has been exceptionally high already since the beginning of the Russian–Ukrainian war in 2014, and has further increased during the full-scale invasion (Zarembo Citation2023).

Executive shifts, corruption scandals and pre-election rivalry

Possible changes in the government were discussed in the Presidential Office in late 2022 and were accompanied by a series of corruption scandals (Ber Citation2023), resulting in the dismissal of several top officials in January 2023, including Kyrylo Tymoshenko, Deputy Head of the Presidential Office. Later in 2023, more dismissals followed. Law enforcement agencies conducted searches at the residences of top officials including former ministries and MPs, as well as oligarch Ihor Kolomoiskyi. Thereby, the president aimed to demonstrate his political determination in the fight against corruption serving his campaign agenda amid possible presidential elections. Under normal circumstances these elections were scheduled for 2024, but they were ultimately postponed until the ending of the martial law (Trubetskoy Citation2023). This action also served as a response to heightened societal sensitivity during the war towards any manifestations of injustice. Additionally, anti-corruption reforms are essential requirements from the European Commission for Ukraine’s eligibility to apply for European Union (EU) membership candidate status (Sydorenko Citation2023).

Tymoshenko’s resignation has become part of a trend known as “deKvartalisation” of the Presidential Office, which began with the appointment of Yermak as its head. Along with strengthening his influence, Yermak has made personnel changes among the staff members who joined the team under Bohdan, the former head. In November 2020, the first Deputy Head, Serhiy Trofimov, was fired. In the summer of 2022, the Head of Security Service, Ivan Bakanov, and the General Prosecutor, Iryna Venediktova, lost their positions, resulting in a further strengthening of the Presidential Office’s control over the law enforcement sphere (Romaniuk Citation2022b; Romaniuk and Kravets Citation2023). During the first year of the full-scale war, Shefir’s political influence, as a member of the former trio that formed the president’s and government’s team, and who previously served as a balancing lever against Yermak, was significantly reduced and he became increasingly sidelined (Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2022b). Instead, close cooperation around the president in the early months of the war led to the emergence of a small community denoted by journalists as the “Bunker Brotherhood” (Romaniuk and Popadiuk Citation2023).

Amid corruption scandals and the awareness of possible presidential and parliamentary elections, Ukraine’s political environment became more polarised in 2023. In the first year of the war, the regime’s opponents refrained from open criticism, but since then critical voices towards Zelenskyi became more pronounced. While these voices could potentially pose challenges to unity and Zelenskyi’s leadership, one might contend that increasing criticism also reflects a healthy maintenance of pluralism and democracy in the Ukrainian society.

Discussion

The starting point of this article was that, as tragic as the situation in Ukraine is, the war provides an opportunity for scholars to examine leadership during extreme conditions. To our best knowledge, this is the first study on executive leadership and power-sharing in a semi-presidential system in the context of a full-scale war. It has represented a novel attempt to uncover executive coordination under Zelenskyi’s presidency during the ongoing war, as a contemporary and challenging case. outlines key observations from our comparison between Zelenskyi’s pre-war period (May 2019–Feb 2022) and the subsequent invasion period until July 2023.

Table 2. Indicators of executive coordination: before and under the war.

Our key theoretical contribution has been the introduction of a new conceptual categorisation of the shifting relations between the president and prime minister within the established sub-categories of premier-presidentialism and president-parliamentarism: figurehead-leader, arbiter-manager and leader-implementer. Ukraine’s premier-presidential constitution as of 2014 outlines an arbiter-manager model where the president has a main responsibility in foreign and defence policy, while the prime minister takes the lead in domestic matters, with the president, if needed, exercising an arbitration role in these domains to ensure the efficient functioning of government. However, in practice and regardless of parliamentary majorities, Ukraine has predominantly followed a leader-implementer model even long before the full-scale war, where the presidents have strived for executive leadership, often leading to conflicts among the president, prime minister and parliament.

With the help of these leadership models and concentrating on the interactions and activities of the key executive leaders in relation to institutional solutions and control over policy domains, we formulated two primary hypotheses to steer our analysis.

In line with H1, our findings indicate that the war conditions have accelerated a pre-existing tendency in Ukraine towards a leader-implementer dynamic, where the prime minister is subordinated to the president. Already before the war, with a solid parliamentary majority, and a government ready to implement the president’s agenda, Zelenskyi had been able to centralise executive governance around himself. Our data, in line with the hypothesis, suggest that the context of war has further consolidated executive powers in the hands of the president and the Presidential Office. During the first year of the full-scale war, the government and to some extent the parliament did function as de-facto subordinated departments under the Presidential Office. This helped to establish a unified position at different levels and to carry out critical policies.

Our second hypothesis (H2) was that the urgent and overwhelming demands on the presidency during the war would necessitate a stricter division of labour, where the president, in accordance with the arbiter-manager model of the premier-presidential constitution, accepts that the main responsibility for directing domestic policy rests with the prime minister. Also this hypothesis was partially confirmed. Somewhat paradoxically, the conditions of imminent crisis, including specific martial law provisions in the hands of the president, have led Zelenskyi to accept a considerable amount of delegation of domestic policy powers to the prime minister. This combination of maintaining control over key processes while delegating certain policy responsibility and avoiding micromanagement surely contributed to Zelenskyi’s successful leadership navigation during the first year of the full-scale war.

We readily acknowledge that this conceptualisation of leadership models requires refinement and more sophisticated testing, beyond this in many respects unusual case. However, we believe that these categories carry potential to better typologise shifting intra-executive relations within and between the general sub-categories of premier-presidentialism and president-parliamentarism that are quite rigid and, in our opinion, fail to capture both the explanatory weight of national political cultures and the dynamic tendencies evident in semi-presidential regimes. Formally powerful presidents can function according to a figurehead-leader model, while constitutionally weaker presidents may be close to arbiter-managers, especially in Central and Eastern Europe. The leadership models also leave room for agency, acknowledging that often the influence of the presidents depends not just on the political context but also on the leadership style of the head of state.

Semi-presidentialism is often viewed negatively as a regime type vulnerable to intra-executive conflicts. Yet our research aligns with the findings of Yan (Citation2023), indicating that during a major crisis a semi-presidential system can operate efficiently and even have its advantages. Zelenskyi has displayed considerable courage and independent agency, but through executive coordination and a division of labour between the president and the government conflicts were largely avoided during the first one and a half year of the war and policymaking continued despite the tragic conditions. Here the “rally around the flag” phenomenon has obviously facilitated cooperation between the main actors, notably given Ukraine’s history of tensions between the president and prime minister. However, an intriguing shift has occurred. Despite having a technocratic prime minister, the war has elevated the army commander to a position second only to the president. In this way, tensions between Zelenskyi and General Zaluzhnyi, who was subsequently dismissed by the president in February 2024, somewhat resemble a transformed version of intra-executive conflict, highlighting the dynamic changes during the crisis.

However, there is a notable distinction between crises such as epidemics and wars, which also differentiates our findings from those of Yan (Citation2023). Typically, health policy falls within the government’s domains, and in semi-presidential countries following the arbiter-manager model, procedural powers to address pandemic challenges rest mainly with the government. Consequently, there is no concentration of procedural authority solely within the president’s domain during epidemics. In contrast, wartime situations necessitate the activation of diplomatic and military efforts, the typical domains of the presidency, leading to executive centralisation around the president.

Based on the case of Ukraine during full-scale war, it may be tempting to argue that a semi-presidential model that largely follows a leader-implementer logic with strong presidential leadership and prime minister subordination, is preferable to a figurehead-leader model where the prime minister has the upper hand, and the president retains mainly representative functions. However, the existing literature does not provide clear evidence that presidential leadership is superior to prime minister leadership in coordinating executive politics during times of crisis or war. And from our single case study, we have no basis for arguing that a figurehead president with a strong prime minister could not be equally effective. In line with expectations of effective semi-presidential government under the leader-implementer model, we can conclude that Zelenskyi’s leadership has benefited from his one-party majority in parliament, which has allowed him to appoint prime ministers tasked with implementing the president’s policy agenda during the most difficult time of Ukraine’s independent statehood. However, a cause for concern is that, using martial law as justification, a series of decisions and legislative changes have de-facto extended presidential powers and influence. These include appointment and resignation powers, as well as increased control over the media sphere, justice and anti-corruption system. Under normal conditions, a more balanced distribution of power between the president, government, and parliament is required to ensure the kind of power-sharing model envisioned by the premier-presidential constitution and, indeed, to safeguard democratic principles.

A noteworthy aspect from among our findings, deserving further examination in future studies across semi-presidential regimes, is the role and position of the presidential administration. The Presidential Office has become the primary decision-making centre in the country, despite lack of constitutional norms that regulate its functions. In Ukraine, as in other post-Soviet countries (Choudhry, Sedelius, and Kyrychenko Citation2018; Jones-Luong Citation2002), these powerful offices have contributed to the presidents surpassing the intended scope of formal presidential prerogatives outlined in premier-presidential constitutions. The substantial expertise and investigative resources at the disposal of these offices have empowered presidents to effectively counterbalance their constitutionally limited authority after shifting from president-parliamentarism to premier-presidentialism.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this study to the participants at the ECPR workshop on “Presidents, Governments and Policymaking” in Toulouse 2022, and to our political science colleagues at Dalarna University, Tampere University and Södertörn University, especially to Jenny Åberg, Maarika Kujanen, Mažvydas Jastramskis and Nicholas Aylott. Finally, we extend our appreciation for the constructive and useful feedback from the anonymous reviewers of East European Politics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thomas Sedelius

Thomas Sedelius is a professor of political science at Dalarna University, Falun, and a project researcher at Södertörn University, Stockholm. Sedelius’ research covers political institutions and democracy with an emphasis on Central and Eastern Europe, Ukraine and presidential politics. He is the chair of the Standing Group on Presidential Politics in the ECPR, and his previous work has appeared in international books and journals, e.g. “Presidential activism in sub-Saharan Africa” (Political Studies Review, 2023, with Sophia Moestrup); “A structured review of semi-presidential studies” (British Journal of Political Science, 2020, with Jenny Åberg); Semi-Presidential Policy-Making in Europe (Palgrave, 2020, with Tapio Raunio) and “Unravelling semi-presidentialism” (Democratization, 2018, with Jonas Linde).

Olga Mashtaler

Olga Mashtaler is a researcher and PhD student at the National University of “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy” (Ukraine). In 2023, she held a guest scholarship at Dalarna University (Sweden) funded by an Erasmus + research exchange program. In 2024, she is conducting her studies at Tampere University (Finland), with support of the Finnish National Agency for Education. Mashtaler’s research covers political institutions, semi-presidentialism, political culture and East European politics. Among her previous publications, she authored “Two decades of semi-presidentialism: issues of intra-executive conflict in Central and Eastern Europe” in East European Politics (2013, with Thomas Sedelius).

Tapio Raunio

Tapio Raunio is a professor of political science at Tampere University. His research interests cover legislatures and political parties, the European Union, executives, semi-presidentialism, foreign policy decision-making and the Finnish political system. His publications have appeared in journals such as the European Journal of Political Research, Journal of Common Market Studies, Journal of European Public Policy, Party Politics and Scandinavian Political Studies. Recent publications include the book Semi-Presidential Policy-Making in Europe: Executive Coordination and Political Leadership (Palgrave 2020, with Thomas Sedelius).

Notes

1 In their IDEA reports on semi-presidentialism, Choudhry and Stacey (Citation2014) and Choudhry, Sedelius, and Kyrychenko (Citation2018, 51–52) operate with the labels figurehead-principal, arbiter-manager and principal-agent. Although these are informative, there is potential risk of confusion with the extensive principal-agent literature, introducing connotations beyond the specific context of intra-executive relations in semi-presidential regimes.

2 At the second round of the 2019 presidential elections, Zelenskyi received 73.2% of the popular vote. After the subsequent parliamentary elections, the coalition was formed by 254 MPs (out of 450) from “The Servant of the People”. In comparison, after the elections in 2014 the parliamentary coalition included five political parties and included 302 MPs. http://bit.ly/3JmGXwp.

3 According to the Institute of Mass Information, Ukrainska Pravda was the most visited online media outlet in Ukraine in 2020 (Bratushchak Citation2020) and ranked second in terms of compliance with professional standards (Institute of Mass Information Citation2020).

4 The Administration of the President was established by President Leonid Kravchuk in 1991. Following the constitutional amendments of 2004, it was renamed and reorganised into the Secretariat of the President by President Viktor Yushchenko. Then again, President Yanukovych in 2010 restored the original name, the Administration of the President. In 2019 President Zelenskyi signed a decree transforming it into the Office of the President of Ukraine (Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Office_of_the_President_of_Ukraine).

5 For the current management structure of the Presidential Office, see https://www.president.gov.ua/en/administration/office-management.

6 The main working place for the president and part of the country’s top leadership during the first phase of the full-scale war became a bunker, built during the Soviet era and designed for the work of top political and military commanders in the event of a nuclear attack and located on the territory of the Presidential Office (see Kravets and Romaniuk Citation2022a).

7 The Staff of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief (“Stavka”), Ukraine. Wikipedia, https://bit.ly/3YrptoI.

References

- Åberg, J., and T. Sedelius. 2020. “A Structured Review of Semi-Presidential Studies: Debates, Results, and Missing Pieces.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 1111–1136. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000017.

- Agency for Legislative Initiatives. 2020. “The Third Session of the Verkhovna Rada: What Has Changed in the Work of the Parliament?” 31 July. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://parlament.org.ua/en/2020/07/31/the-third-session-of-the-verkhovna-rada-what-has-changed-in-the-work-of-the-parliament/.

- Agency for Legislative Initiatives. 2022. “Voiennyi parlamentaryzm: yak parlamentarii vidpratsiuvaly v umovakh spilnoi zahrozy [War Parliamentarism: How Parliamentarians Worked Amid Common Threat].” Dzerkalo Tyzhnia, 12 December. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://zn.ua/ukr/internal/vojennij-parlamentarizm-jak-parlamentariji-vidpratsjuvali-v-umovakh-spilnoji-zahrozi.html.

- Agency for Legislative Initiatives. 2023. “Monitoring the VRU’s Work During the 8th Session: Stabilisation During Martial Law”. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://parlament.org.ua/en/2023/07/18/monitoring-the-vru-s-work-during-the-8th-session-stabilisation-during-martial-law/.

- Amorim Neto, O., and A. Anselmo. 2023. “Presidential Activism and Success in Foreign and Defence Policy: A Study of Portugal’s Premier-Presidential Regime.” Political Studies Review, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299231183575.

- Analytical portal “Slovo i dilo”. 2021. “Zelenskyi na pres-marafoni dav 16 obitsianok, ale maizhe vsi lunaly ranishe [Zelenskyi Gave 16 Promises at the Press-Marathon. Almost All Were Voiced Earlier].” 26 November. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.slovoidilo.ua/2021/11/26/novyna/polityka/zelenskyj-presmarafoni-dav-16-obicyanok-majzhe-vsi-lunaly-ranishe.

- Analytical portal “Slovo i dilo”. 2022. “Shmyhal tak i ne podav novu prohramu dii uriadu u 2021 rotsi [Shmyhal Still Did Not Submit a New Government’s Action Plan].” 8 January. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.slovoidilo.ua/2022/01/08/novyna/polityka/shmyhal-tak-ne-podav-novu-prohramu-dij-kabminu-2021-roczi.

- Ash, K., and M. Shapovalov. 2022. “Populism for the Ambivalent: Anti-Polarization and Support for Ukraine’s Sluha Narodu Party.” Post-Soviet Affairs 38 (6): 460–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2022.2082823.

- Benamouzig, D. 2023. “France: From Centralization to Defiance?” In Governments’ Responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic in Europe, edited by K. Lynggaard, M. D. Jensen, and M. Kluth, 359–369. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ber, J. 2023. “Ukraine: A Wave of Dismissals Against a Background of Corruption.” Centre for Eastern Studies, 31 January. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2023-01-31/ukraine-a-wave-dismissals-against-a-background-corruption.

- BIHUS.Info. 2021. “Bratstvo Kvartalu [Kvartal’s Brotherhood].” 15 November. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cImG6T2Vgpo.

- Boin, A., and P. ‘t Hart. 2012. “Aligning Executive Action in Times of Adversity: The Politics of Crisis Coordination.” In Executive Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by M. Lodge and K. Wegrich, 179–196. New York: Palgrave.

- Bratushchak, O. 2020. “Reityng Topsaitiv Ukrainy [Ranking of Ukraine’s Top-Sites].” Institute of Mass Information, 11 September. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://imi.org.ua/monitorings/rejtyng-top-sajtiv-ukrayiny-i34992.

- Brunclík, M., M. Kubát, A. Vincze, M. Kindlová, M. Antoš, F. Horák, and L. Hájek. 2023. Power Beyond Constitutions: Presidential Constitutional Conventions in Central Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bryzhko-Zapur, N. 2023. Ya tut. My vsi tut. My vsi – tse Ukraina. Fenomen Volodymyra Zelenskoho [I Am Here. We All Are Here. We All Are Ukraine. Volodymyr Zelenskyi’s Phenomenon]. Kyiv: Akademiia.

- Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. 2022. The Decree #1400 “On Some Issues of Activities of Central Executive Bodies.” 17 December. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1400-2022-%D0%BF#Text.

- Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. 2023. “Annual Report on the Implementation of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement released”. 24 March. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/opryliudneno-shchorichnyi-zvit-pro-vykonannia-uhody-pro-asotsiatsiiu-ukraina-ies.

- Choudhry, S., T. Sedelius, and J. Kyrychenko. 2018. Semi-Presidentialism and Inclusive Government in Ukraine: Reflections for Constitutional Reform. Stockholm: International IDEA.

- Choudhry, S., and R. Stacey. 2014. Semi-Presidentialism as Power Sharing: Constitutional Reform After the Arab Spring. Stockholm: International IDEA.

- Chowanietz, C. 2010. “Rallying Around the Flag or Railing Against the Government? Political Parties Reactions to Terrorist Acts.” Party Politics 17 (5): 673–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809346073.

- D’Anieri, P. 2023. Ukraine and Russia: From Civilized Divorce to Uncivil War. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Derix, S., and M. Shelkunova. 2022. Zelensky. A Biography of Ukraine’s War Leader. London: Canbury Press.

- Devine, D., J. Gaskell, W. Jennings, and J. Stoker. 2020. “Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the Consequences of and for Trust?” An Early Review of the Literature.” Political Studies Review 19 (2): 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920948684.

- Dorontseva, Y. 2022. “State Regulation in Wartime: How the President and MPs Managed the Country in the First Hundred Days of Martial law.” Vox Ukraine, 20 June. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://voxukraine.org/en/state-regulation-in-wartime-how-the-president-and-mps-managed-the-country-in-the-first-hundred-days-of-martial-law/.

- Drent, M., and M. Meijnders. 2015. “Multi-year Defence Agreements: A Model for Modern Defence?” Clingendael Report, September. Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations. https://www.clingendael.org/publication/multi-year-defence-agreements-model-modern-defence.

- Elgie, R. 2011. Semi-presidentialism: Sub-Types and Democratic Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elgie, R. 2018. Political Leadership: A Pragmatic Institutionalist Approach. London: Palgrave.

- Fruhstorfer, A., and M. Hein, eds. 2016. Constitutional Politics in Central and Eastern Europe: From Post-Socialist Transition to the Reform of Political Systems. New York: Springer VS.

- Grimaldi, S. 2023. “The Elephant in the Room in Presidential Politics: Informal Powers in Western Europe.” Political Studies Review 21 (1): 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299211041957.

- Hale, H., and R. W. Orttung. 2016. Beyond the Euromaidan: Comparative Perspectives on Advancing Reforms in Ukraine. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

- Helms, L. 2012. Comparative Political Leadership. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Howell, W. G., S. P. Jackman, and J. C. Rogowski. 2013. The Wartime President: Executive Influence and the Nationalizing Politics of Threat. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Institute of Mass Information. 2020. “Compliance with Professional Standards in Online Media. 2nd Wave of Monitoring.” 2 July. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://imi.org.ua/en/monitorings/compliance-with-professional-standards-in-online-media-2nd-wave-of-monitoring-in-2020-i33901.

- Ivanov, O. 2022. “Zakupivli pid chas povnomasshtabnoi viiny [Public Procurement During the Full-Fledged War].” VoxUkraine, 13 October. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://voxukraine.org/zakupivli-pid-chas-povnomasshtabnoyi-vijny.

- Iwański, T., S. Matuszak, K. Nieczypor, and P. Żochowski. 2020. “Neither a Miracle nor a Disaster – President Zelensky’s First Year in Office.” Centre for Eastern Studies, OSW Commentary, 20 May. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2020-05-20/neither-a-miracle-nor-a-disaster-president-zelenskys-first.

- Jones-Luong, P. 2002. Institutional Change and Political Continuity in Post-Soviet Central Asia: Power, Perceptions, and Pacts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kassop, N. 2003. “The War Power and Its Limits.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 33 (3): 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/1741-5705.00004.

- Köker, P. 2017. Presidential Activism and Veto Power in Central and Eastern Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Komarov, D. 2023. Special Project “Year”. Issue “Behind the scenes. The Minister”, 5 May. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kmpy9B7CCH8.

- Kravets, R. 2022. “Televizor i vlada. Yak pratsiuie telemarafor zseredyny ta khto yoho kuruie [TV and Authorities. How the TV-Marathon Is Operating and Who Manages It].” Ukrainska Pravda, 21 June. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2022/06/21/7353715/.

- Kravets, R. 2023. “Oleksandr Martynenko: Yak keruiut prezydenty, rol Yermaka, polityka za lashtunkamy [Oleksandr Martynenko: How Presidents Govern, Yermak’s Role, Politics Behind the Scene].” Ukrainska Pravda, 23 May. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2023/05/23/7403393/.

- Kravets, R., and R. Romaniuk. 2019. “Bohdan, Shefir, Yermak. Yak pratsiyiut naiholovnishi liudy v Ofisi prezydenta [Bohdan, Shefir, Yermak. How the Main People in the President’s Office Work].” Ukrainska Pravda, 11 September. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2019/09/11/7225909/.

- Kravets, R., and R. Romaniuk. 2021. “Minus Medvedchuk, plus Poroshenko: subiektyvni pidsumky 2021go [Minus Medvedchuk, Plus Poroshenko: Subjective Conclusions of the Year 2021].” Ukrainska Pravda, 30 December. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2021/12/30/7318973/.

- Kravets, R., and R. Romaniuk. 2022a. “Vladnyi bunker. Yak Zelenskyi keruie krainoiu za chasiv viiny [Power Bunker. How Zelenskyi Is Governing the Country During the War].” Ukrainska Pravda, 7 April. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2022/04/7/7337694/.

- Kravets, R., and R. Romaniuk. 2022b. “Voiennyi Kvartal. Khto teper holovnyi v otochenni Zelenskoho [Military Kvartal. Who is Now the Main One in Zelenskyi’s Environment]”. Ukrainska Pravda, 2 June. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2022/06/2/7349990/.

- Kravets, R., and R. Romaniuk. 2022c. “Kabinet myru i viiny. Yak Zelenskyi pereris svii uriad [Cabinet of Peace and War. How Zelenskyi Overgrew His Government].” Ukrainska Pravda, 30 June. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2022/06/30/7355491/.

- Kravets, R., and R. Romaniuk. 2023. “Vstyhnuty do kontrnastupu. Posylennia Yermaka, rotatsiia v Kabmini, obrazy deputativ [Make It Before the Counter-Offensive. Yermak’s Strengthening, Rotation in the Cabinet of Minister, MPs’ Resentments].” Ukrainska Pravda, 30 January. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2023/01/30/7387043/.

- Krol, G. 2021. “Amending Legislatures in Authoritarian Regimes: Power-Sharing in Post-Soviet Eurasia.” Democratization 28 (3): 562–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1830065.

- Kudelia, S. 2018. “Presidential Activism and Government Termination in Dual-Executive Ukraine.” Post-Soviet Affairs 34 (4): 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2018.1465251.

- Kuzio, T., and S. Jajecznyk-Kelman. 2023. Fascism and Genocide. Russia’s War Against Ukrainians. Series “Ukrainian Voices”. Stuttgart: Ibidem Press.

- Lukashova, S., and R. Kravets. 2019. “Ze!Premier. Shcho rozpovidaiut pro Honcharuka liudy, yaki yoho znayut’ [Ze!Prime-Minister. What People Who Know Honcharuk Are Telling About Him]. Ukrainska Pravda, 29 August. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2019/08/29/7224703/.

- Mashtaler, O. 2021. “The 2019 Presidential Election in Ukraine: Populism, the Influence of the Media, and the Victory of the Virtual Candidate.” In The Politics of Authenticity and Populist Discourses: Media and Education in Brazil, India and Ukraine, edited by Ch. Kohl, B. Christophe, H. Liebau, and A. Saupe, 127–160. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55474-3_7.

- Milner, H. V., and D. Tingley. 2015. Sailing the Water’s Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Minakov, M. 2022. “Ukraine’s Political Agenda for 2022: European Integration, Deoligarchization, and Economic Growth.” Wilson Center, January 25. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/ukraines-political-agenda-2022-european-integration-deoligarchization-and-economic-growth.

- Moestrup, S., and T. Sedelius. 2023. “Presidential Activism in Sub-Saharan Africa: Explaining Variation among Semi-Presidential Countries.” Political Studies Review, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299231204555

- Mueller, J. E. 1973. War, Presidents, and Public Opinion. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Musaieva, S., and R. Romaniuk. 2020. “Premier Denys Shmyhal: Karantyn vykhidnoho dnia – tse ukrainskyi produkt [Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal: Weekend Quarantine Is an Ukrainian Know-How].” Ukrainska Pravda, 10 December. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2020/12/10/7276448/.

- Nations in Transit. 2022. From Democratic Decline to Authoritarian Aggression. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2022/from-democratic-decline-to-authoritarian-aggression.

- Nemec, J. 2021. “Government Transition in the Time of the Covid-19 Crisis: Slovak Case.” International Journal of Public Leadership 17 (1): 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-05-2020-0040.