ABSTRACT

People seem to trust the president more than other national political institutions. In the context of semi-presidential regimes, it is plausible that the role of the president being “above party politics” is an explanatory factor behind this pattern. This study challenges the argument by analysing the impact of citizens' party preferences and attitudes towards the political system on trust in president in select CEE countries. The results confirm that trust in president is often context specific and cannot be disassociated from partisan factors. In general, similar patterns are found between trust in president and trust in prime minister.

Introduction

In many European semi-presidential countries, presidents possess relatively weak constitutional powers, they are less attached to political parties than prime ministers, and in the end, more popular than other national political institutions. In such regimes, the position of the president as standing “above party politics” has been argued to be a key factor behind the president’s favourable public position (e.g. Duvold and Sedelius Citation2022; Raunio and Sedelius Citation2020; Tavits Citation2009). This reflects the “Gaullist” idea of a presidency being above parties and representing the whole nation, which separates the office from other political institutions. Presidents do, however, vary in terms of their relations with political parties and the level of their political “activeness”, which may as well impact public opinion on them.

Scholars have examined presidents in European semi-presidential regimes from many perspectives, yet not very systematically in the context of public opinion. The lack of studies may relate to the scarcity of cross-national public opinion surveys including questions about presidents, which in Tavits’s words can be regarded as “another example of the low regard of this office among political scientists” (Tavits Citation2009, 143). Moreover, apart from simple comparisons of the percentages of trust in president versus other institutions, we lack systematic empirical evidence of the differences between individuals in terms of trust in president.

Drawing on the literature on political trust and semi-presidentialism, this study discusses different aspects potentially related to trust in president from general explanations associated with political trust to dynamics between the executives. Empirically, it investigates the impact of various individual-level factors from sociodemographic variables to partisan preferences and political attitudes. The empirical analysis is mainly explorative due to the lack of studies in the context of semi-presidentialism. The research question is “Which individual-level factors drive trust in president in semi-presidential regimes?”. The main contribution of this study is to reveal patterns between individuals in terms of trust in president in European semi-presidential regimes, which should increase our understanding about the public role of the president in general.

The focus is on a group of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries with a semi-presidential constitution: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. The determinants of trust in president across the CEE countries are examined in relation to trust in prime minister, which enables us to investigate to what extent the role of the president differs from more explicitly partisan actors in the eyes of the citizens. Analysing only the determinants of trust in president does not provide this information. This relates to the theory of presidential leverage by Ponder (Citation2018), suggesting that president’s political capital increases only if the president is relatively more popular than the government, and thus trust in president should not be examined in isolation. Second, prime minister represents a more specific political institution than for example the government or the parliament, since only one person can hold the office. As the head of national government, prime minister is usually politically stronger than the president and her/his public position is therefore different from the president, providing an intuitive point of reference in the empirical analysis.

The empirical analysis relies on Social-Political Survey from 2016 (Ekman, Duvold and Berglund Citation2023a) and Baltic Barometer from 2014 (Ekman, Duvold and Berglund Citation2023b), but the results of the main analysis are compared with data from New Europe Barometer (Citation2001) and the Finnish National Election Survey from 2019 (Grönlund and Borg Citation2019). This procedure allows us to examine the trust patterns in two time points and compared to another semi-presidential country outside the CEE region. Whereas the select CEE countries share the history of communism and democratic transition at the beginning of 1990s, which have impacted on the culture of political trust in these systems (e.g. Mishler and Rose Citation1999), Finland represents an established democracy with high levels of trust in public institutions and is therefore treated as an “opposite” reference case within the regime type.

The results of the empirical analysis show that while some general factors associated with political trust such as satisfaction with democracy and social trust explain trust in both examined institutions, not only trust in prime minister but also trust in president is affected by political factors and party preferences, which challenges the idea of the president standing “above party politics” in the eyes of the citizens. At the same time, the presidents gain support broadly from different sociodemographic groups, as age, gender, education and income produced weak and inconsistent results, supporting the theory that political trust is more connected to political factors rather than social or economic factors (Norris Citation1999).

This article continues as follows. In the next section, I briefly discuss the historical and cultural differences and similarities between the examined countries in the light of political trust and semi-presidentialism to further justify the case selection. In the following section, I introduce the theoretical background concentrating on explanations of political trust provided in the earlier literature and on the role of the president in semi-presidential regimes. Then I introduce the research design, including data and methods, followed by the results. Finally, I discuss the findings of the explorative analysis in the concluding section of this article.

Case selection

Being the most common regime type in Europe (Anckar Citation2022), semi-presidentialism covers a wide range of political systems with different political cultures and practices, ranging from established democracies to regimes that became democratic since the early 1990s (not to mention autocracies). By definition, semi-presidential regimes include “both a directly elected fixed-term president and a prime minister and cabinet who are collectively responsible to the legislature” (Elgie Citation2011, 3). In practice, the separation of powers in the executive branch distinguishes semi-presidentialism from presidentialism and the mode of the presidential election separates semi-presidentialism from parliamentarism (Shugart and Carey Citation1992). These core features of semi-presidentialism (separation of executive powers and direct elections) should impact the relationship between the president and the public, which guides the selection of the regime type in this study.

Many CEE countries became semi-presidential by adopting a new post-communist constitution after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 (Elgie Citation2011). This wave of new semi-presidential constitutions also resulted in an increasing number of studies focusing on semi-presidentialism in the post-communist region (Åberg and Sedelius Citation2020). Comparative studies have shown that political trust is comparatively low and volatile in post-communist countries, shaped by the history of communism and transition to democracy (e.g. Mishler and Rose Citation1999; Norris Citation2011; Závecz Citation2017). Over the last decades, there has been a decline in the levels of political trust in the post-communist countries, although the trend does not apply only to this region. Economic performance, corruption and institutional challenges have impacted the level of institutional trust, and at the individual level the volatility of trust also relates to the shared experiences living under the old regime, scepticism about the new one and general well-being. (Catterberg and Moreno Citation2005; Mishler and Rose Citation1999, Citation2001; Závecz Citation2017),

Sharing this background, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia are included in this study to examine more systematically the determinants of trust in president within the semi-presidential regime type. Of course, the democratisation process has been unique in each country and the presidencies differ in terms of constitutional powers, which purportedly impacts not only the dynamics between the president and other political institutions but also the public role of the president given that constitutionally weaker presidents seem to enjoy higher popularity ratings than their more powerful counterparts (Kujanen Citation2024). According to various studies measuring presidential powers, presidents in the select countries possess “medium-level” presidential powers, with the Slovenian president having the weakest and Romanian president having the strongest powers. In comparison, the Finnish president possesses comparatively weak constitutional powers, having practically no legislative ones, but still leads the country’s foreign policy in cooperation with the government, and the French president stands out from most European semi-presidential systems with its relatively strong powers in both foreign and domestic politics. (e.g. Doyle and Elgie Citation2016; Metcalf Citation2000; Shugart and Carey Citation1992; Siaroff Citation2003). Similarly, the level of attachment to political parties and relations with government and parliament varies between the presidents (e.g. Brunclík and Kubát Citation2019), which may as well have an impact on public opinion on presidents.

The examined countries share the same subtype of semi-presidentialism, premier-presidentialism, where the prime minister and cabinet are collectively responsible to the legislature but not to the president. The other subtype, president-parliamentarism, would put the president to a relatively more powerful position as the prime minister and cabinet are not only responsible to the legislature but to the president as well (Elgie Citation2011; Shugart and Carey Citation1992). The selected countries, including the year when they adopted semi-presidentialism and presidential power scores from two common sources, are presented in .

Table 1. Case selection.

Whereas in the younger democracies in Central and Eastern Europe the rules and practices of political institutions may be less established, in Western Europe the development has been distinctively different. This is connected to various social and cultural aspects of the societies, starting from lower level of corruption and stronger economic development to generally higher level of trust in institutions among the citizens (e.g. Torcal Citation2017). As a Nordic welfare state and established democracy, Finland represents a reference case in this study. This means that patterns found in the post-communist semi-presidential regimes regarding the determinants of trust in president are compared with the Finnish case, and if similar findings occur in both CEE countries and in Finland, it would strengthen the applicability of the offered explanations in a wider context. In terms of public opinion, Finland could be also described as an “exceptional case” as the Finnish presidents have enjoyed extremely high and stable popularity ratings throughout the first two decades of the twenty-first century (Kujanen Citation2024), while trust in other political institutions has remained at more moderate levels over the same period (Bäck and Kestilä-Kekkonen Citation2019).

Common explanations of political trust

Political trust is a well-researched topic among political scientists. The importance of studying political trust relates to the functioning of democracy and maintaining the “stability, viability and legitimacy” of a political system (Van der Meer and Zmerli Citation2017, 1). Public opinion surveys asking about public trust usually include a range of political actors and institutions (government, parliament, parties, prime ministers and presidents) and public authorities (police, army and court). In such surveys, presidents systematically score quite well (e.g. Duvold and Sedelius Citation2022, 10; Raunio and Sedelius Citation2020, 67; Tavits Citation2009, 144). In contrast, the more partisan the institution is the less people seem to trust it. This is reflected in relatively low trust ratings for politicians and political parties.

In the literature, political trust is strongly associated with partisan factors such as general party identification, party-ideological orientations and support for the “winning” parties (Norris Citation1999, Citation2011; Zmerli and Van der Meer Citation2017). On the one hand, citizens who identify at least with some party are expected to express stronger political trust than those who do not identify with any of the parties. The explanation is that political parties integrate people to the political system and thus cause feelings of trust among the public (Miller and Listhaug Citation1990). This relates also to more general political attachment and feelings of belonging to the society. On the other hand, the level of political trust is expected to be stronger among people who identify with parties that are represented in the government (winners) instead of parties in the opposition (losers) (Newton Citation1999; Norris Citation1999, Citation2011). This applies to trust in elected officials, such as the government, but also to trust in the political system in general.

According to this theory, what counts is the citizens’ beliefs of whether their interests are represented by the elected politicians. Consequently, winners who support the governing parties tend to trust the political system more than losers who identify with the opposition. Norris (Citation1999, 219) described the logic as follows:

At the simplest level, if we feel that the rules of the game allow the party we endorse to be elected to power, we are more likely to feel that representative institutions are responsive to our needs so that we can trust the political system. If we feel that the party we prefer persistently loses, over successive elections, we are more likely to feel that our voice is excluded from the decision-making process, producing dissatisfaction with political institutions.

Previous studies have also shown that general trust in the political system turns into trust in incumbent officeholders, and vice versa, people who do not trust the system probably feel distrust towards the specific actors as well (Zmerli and Hooghe Citation2011). Similarly, political trust is connected to satisfaction with democracy, measuring peoples’ evaluation of the ability of the current system (and its institutions) to solve important problems (e.g. Newton and Zmerli Citation2011; Norris Citation1999, Citation2011). In other words, if citizens are satisfied with how democracy works in their country, it should be more probable that they express trust rather than distrust towards political institutions.

Other individual-level explanations emphasise for example citizens’ sociodemographic background, social trust and general political attitudes. For example, higher level of political interest, education, more stable income, higher social class, and trust in other citizens are associated with higher level of political trust (e.g. Goubin and Hooghe Citation2020; Mayne and Hakhverdian Citation2017; Newton and Zmerli Citation2011). The partisan dimension does, however, explain political trust better than the social or economic factors, the impact of which are more random (Norris Citation1999). This seems to apply in both established democracies and in post-communist countries (Závecz Citation2017).

Trust in president – a different case?

What drives trust in president in semi-presidential regimes? We have good reasons to expect that some of the common explanations associated with political trust apply to trust in president as well, yet we should also consider the special features of the office. On the one hand, the “symbolic” nature of the institution and the expected role of the president as operating “above party politics” might benefit the president at the expense of other political institutions. On the other hand, not all presidents operating alongside the prime ministers match this description, as some presidents tend to keep close party ties and even publicly intervene in the government’s work. In other words, the president’s more favourable public position in comparison with the prime minister does not seem to generate disagreement among scholars, yet we lack empirical evidence to support the claims that the presidents would be above parties in the eyes of the citizens.

Going further into the mechanisms of trust in president specifically in semi-presidential regimes, we should indeed consider the position of the president in comparison with other political institutions, primarily the prime minister and the government. In premier-presidential democracies, the executive power is shared by the popularly elected president and the government. Prime minister typically leads the government and is responsible for domestic matters, while the president is more concentrated on foreign policy issues and representing the country abroad. This “dual executive structure” with limited presidential powers and the nature of direct presidential elections seems to benefit the president in relation to the prime minister, as described by Raunio and Sedelius (Citation2020, 29): “The presidents’ greater popularity may be attributed to their limited powers and to their status as being above party politics, elevated from the usual political quarrels. Prime ministers, on the contrary, experience the dilemma of exercising their power in areas of controversy policies, such as those related to social and economic issues, thereby often eroding their popular support”. In a similar vein, Tavits (Citation2009, 142) argued that “Because of the generally noncontroversial nature of the office of the president and its distance from the day-to-day politics, the president is less likely to be faced with difficult policy decisions and harmed by partisan mudslinging”.

This line of argument emphasises the less “partisan” feature of the presidency, where the president is expected to represent the whole nation across party boundaries. Rather than being a party-political actor, presidents are expected to behave like “statespersons” who uphold “the ‘common good’ of the state by not allowing any one particular interest to dominate it internally” (Beardsworth Citation2017, 114). According to this logic, if the president is truly “above party politics” and the public trusts the president to look after all citizens’ interests, the president’s party background should not be a significant factor when people are evaluating the incumbent president. On the contrary, trust in institutions that are more partisan, such as the prime minister, should be more dependent on citizens’ party-political attitudes.

Lithuanian presidency is a good example of this perspective due to its tradition of non-partisan presidents. It is stated in the country’s constitution that the presidents must suspend their activity in political parties after being elected, and the presidents seem to implement this strategy. This together with the general distrust in political parties has been connected to the success of non-partisan presidents and presidential candidates (Jastramskis Citation2021, Citation2022) and presidential activism: “Some presidents in semi-presidential republics have their parties in the government and can act through them. This road is closed for Lithuanian presidents: however, non-partisan status almost guarantees higher support from the public, as Lithuanians do not trust the parties. Therefore, the incentives for presidents in Lithuania to go public are really strong” (Jastramskis and Pukelis Citation2023, 9).

However, the extent to which the president adopts this ideal role of a statesperson varies across different countries, and so does the extent to which citizens “tolerate” the president’s party background or political behaviour. Furthermore, in many semi-presidential countries in Central and Eastern Europe, the presidents are publicly attached to party politics. As an example, the two latest Czech presidents, Václav Klaus and Miloš Zeman, were both former party chairs and former prime ministers when entering the presidential office. Both tried to somewhat distance themselves as presidents from parties in their public statements yet simultaneously supported particular politicians and parties, especially Zeman (Brunclík and Kubát Citation2019). Also, in Romania the presidents have kept closer party ties and have tried to politically benefit from them and have also directly intervened in government’s work (Brunclík and Kubát Citation2019; Gherghina, Tap, and Farcas Citation2023; Raunio and Sedelius Citation2020). Furthermore, both Traian Băsescu and Klaus Iohannis were involved in the processes of electing their successors as party leaders, nominated prime ministers mostly from their own political camps, influenced government coalition agreements and in connection with elections supported their former parties (Gherghina, Tap, and Farcas Citation2023). Similar examples of such presidential activism can be found in several CEE countries from presidents vetoing the legislation (Köker Citation2017) to engaging in conflicts with prime ministers (Sedelius and Mashtaler Citation2013).

It is also a question about the institution and the person in office: which one plays a bigger role and to what extent the nature of the office “protects” the incumbent president. This relates to the discussion of specific versus diffuse support, the classical distinction of political trust by Easton (Citation1965, Citation1975). From these two categories, specific support focuses more on what the institution does, i.e. on the performance of political actors, and diffuse support more on what it represents, dealing with attitudes towards the whole political system (Norris Citation1999; Norris Citation2017, 21). Earlier studies suggesting that presidents enjoy systematically higher trust than other political institutions reflect the latter perspective. In other words, if trust in president is more dependent on the features of the presidential office and less sensitive to the performance of the incumbent office holder, it would support the theory of diffuse support, one interpretation of which is that “political institutions persist even though incumbent leaders are removed from office” (Norris Citation2017, 21).

On the other hand, support for individual presidents may also vary considerably within the same country, raising questions of more specific support. The presidential office is so personalised that in terms of trust people might think about the performance of the current office holder instead of the institution. In general, people do not often distinguish political institutions and political actors when weighting their opinions (Norris Citation2017, 24). According to Duvold and Sedelius (Citation2022, 2), trust in president should be indeed viewed as an intermediate category: “obviously contingent on the popularity of the person in office, but also a symbol of the institution itself”.

Research design

This study employs individual-level opinion surveys from seven semi-presidential countries: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Lithuania. The analysis draws on Social–Political Survey including the first six countries, conducted in autumn 2016 (Ekman, Duvold, and Berglund Citation2023a), and Baltic Barometer including Lithuania, conducted in autumn 2014 (Ekman, Duvold, and Berglund Citation2023b). These datasets were chosen due to the diversity of questions including measurements of trust in president and prime minister, sociodemographic variables, and general political and partisan attitudes.

The empirical results are compared with data from New Europe Barometer from autumn 2001 to control for the possibility of the impact of situational factors on the results, including different incumbents in the office and changes in the national and international political environment. All seven CEE countries are included in the data. Additionally, the results are compared with Finland, an “opposite” reference case, to further examine the compatibility of the results of the regression models in a different context within the regime type. For this purpose, I rely on the Finnish National Election Study from spring 2019 (Grönlund and Borg Citation2019).

The primary dependent variable is trust in president and the secondary dependent variable is trust in prime minister. Both are measured with questions asking to what extent the respondents trust each of the institutions on a scale from 1 to 7, and they are treated as continuous variables. This brings more variation to the dependent variable instead of coding it as a dummy variable (trust/no trust). The independent variables are grouped into two categories: sociodemographic and societal factors, and political factors and party preferences.

Sociodemographic and societal factors include age (as number of years), gender (female or male), education (respondent’s highest completed degree in education), income/respondent’s personal economic situation (whether the respondents get enough money from their main source of income), satisfaction with democracy (whether the respondent feels that the democracy is working in the country) and social trust (trust in most people in the country). These factors stem directly from the literature on political trust, and the aim is to examine whether the same factors apply in the context of trust in president. Other variables associated with political trust exist as well, such as the level of political interest, yet they are not included in the original data and their impact is not thus possible to test in the analysis.

Political factors and party preferences include general party closeness (whether the respondent feels closer to some political party), specific party choice (the specific party the respondent had voted for or was planning to vote, and whether it matches with the party represented by the president or the prime minister), left–right orientation (respondent’s self-placement on a scale from left to right) and indirect measure of satisfaction with the government’s work (sum variable: are people treated equally and fairly by the government + how much influence people have on government). Regarding the first three, the intention is to test does trust in president vary in accordance with the respondent’s self-placement in the party-ideological dimension, while satisfaction with the government performance is included to test to what extent the president is associated with government policies – do feelings of dissatisfaction or scepticism towards the government turn into distrust in president as well or is the president “above” these issues?

Trust in president in relation to other institutions is first examined with descriptive figures and statistics. Second, I utilise Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis with pooled data and separately in each country with representative samples. These are standard methods for analysing political trust and used for similar purposes by many scholars (e.g. Norris Citation2011; Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen Citation2009; and more recently Duvold and Sedelius Citation2022). The basic idea of the model is to test whether the explanations of political trust differ between the institutions, i.e. the president and the prime minister, at the individual level. In the pooled model, the country samples are combined and controlled with dummies for each country. This should control for the contextual effects that are automatically present in such a comparative study.

The independent variables enter the models in three stages, starting with the sociodemographic and societal factors and then moving to political factors and party preferences, with party choice entering the models last as not all presidents or prime ministers have official party affiliations (Dalia Grybauskaitė in Lithuania, Klaus Iohannis and Dacian Cioloș in Romania, and Andrej Kiska in Slovakia). In the pooled regression model, country dummies are included in all stages. Same procedure is used for both dependent variables (trust in president and trust in prime minister), and they are also run separately for each country to examine the country-level patterns in more detail. Söderlund and Kestilä-Kekkonen (Citation2009), for example, followed a similar procedure when analysing political trust in Austria, Denmark and Norway by first employing a pooled OLS regression separately for their two dependent variables (trust in parliament and trust in politicians), and then running the regression models separately for each country. From a comparative perspective, the main interest of this study is in the similarities and differences between the CEE countries, but also how the found explanations of trust in president contrast with the Finnish case.

Pooling the datasets brings some challenges to the analysis. For example, the New Europe Barometer (Citation2001) does not include questions about party identification or left–right orientation, so the only partisan variable is the respondent’s party choice in relation to the parties of the president and the prime minister. In addition, the Finnish National Election Study (Grönlund and Borg Citation2019) does not include a question about trust in prime minister nor about whether people are treated equally and fairly by the government. Due to these shortcomings, the regression models are run in different stages with some adjustments to the variables which are reported under the results of the models in the Appendix.

Results and discussion

Starting with descriptive figures and statistics, presents the share of respondents expressing trust in national political institutions and other public actors across the surveys. The comparison confirms that people trust the president the most, while more partisan institutions, especially political parties, enjoy significantly weaker trust. Prime ministers, governments and parliaments situate between these two institutions. Although presidents stand out with clearly higher trust ratings when compared to other political institutions, in many cases, presidents “lose” to the so-called “order institutions”, such as the army and the police. In general, trust in many political institutions has decreased in most countries (e.g. Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and Romania), especially when compared to other public institutions. This is in line with findings from recent studies in the context of Baltic countries (including Lithuania) according to which during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, the trust trend pointed downwards for political institutions, including the president, while trust in other public institutions (courts, police, and army) went upwards (Duvold and Sedelius Citation2022).

Table 2. Trust in public institutions, mean comparison.

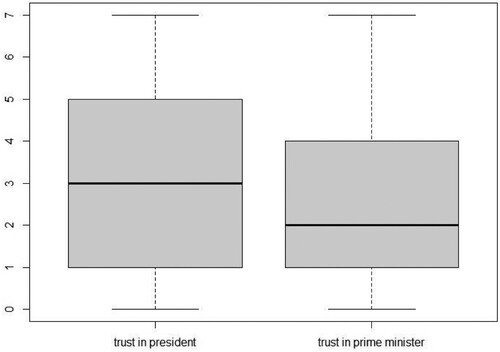

presents the distribution of the mean values for the president and the prime minister in the Social-Political Survey 2016 (Ekman, Duvold and Berglund Citation2023a) with median values (lines inside the boxes). The variables are correlated with each other at statistically significant level (Pearson’s correlation = 0.567, p < 0.001), while the difference between the means of trust in president and trust in prime minister is statistically significant (t-test = 53.702, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Trust in president and trust in prime minister, distribution of values, Social–Political Survey 2016.

and present the results of the regression models examining individual-level differences in terms of trust in president and trust in prime minister in the CEE countries. The interpretation of the results is based on unstandardised beta values with standard errors and p-values. Starting with the pooled models (), both trust in president and trust in prime minister are positively affected by satisfaction with the functioning of the democracy and higher level of social trust, while general sociodemographic factors do not cause major differences between the respondents. Only age makes a difference as an increase in age boosts trust in prime minister but not trust in president. Better income seems to also have a positive effect, but only in the base models (Models 1 and 4).

Table 3. Determinants of trust in president and trust in prime minister in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Romania, pooled OLS models.

Table 4. Determinants of trust in president and trust in prime minister, country-level OLS models.

Moving to political factors and party preferences, both institutions are positively affected by general party closeness, indicating that feeling closer to some specific party increases feelings of trust in president and prime minister, although the impact is stronger in terms of trust in prime minister. Leaning towards political right also seems to increase trust in prime minister but not trust in president. In terms of the government’s work and party choice, more similarities occur. Both the president and the prime minister are negatively affected by dissatisfaction with the government’s work and among people that do not support their parties. Quite logically, however, being the head of the government, trust in prime minister decreases more significantly due to general dissatisfaction with the government, and the impact of party choice is also stronger in the context of trust in prime minister than compared to trust in president.

Results of the country-level regression models in echo these findings. First, the general sociodemographic factors do not seem to explain trust in either institution very well, except for the impact of higher age on trust in president in the Czech Republic and trust in prime minister in Lithuania and Slovakia, and the impact of better personal economic situation on trust in president in Lithuania. This echoes the notion by Norris (Citation1999, 180) that “age, education and income are often related to variations in social and political trust, but the relationships vary from country to country”. Second, positive opinions towards the functioning of the democracy increase trust in both institutions in each country except for trust in president in the Czech Republic. Higher level of social trust also turns out to be a statistically significant factor behind both trust in president and trust in prime minister but not as systematically as the democracy attitudes.

Moving to the political factors and party preferences, interesting differences occur between the executives but also between the countries. First, while general party closeness turns out to be a weak and statistically insignificant factor at the country level, the left–right dimension seems to cause more variation both within and between the countries, although not being statistically significant in half of the models. The direction of the left–right dimension seems to be context specific and reflects the parties’ placement on the same scale. For example, leaning towards right increases trust in president in Bulgaria (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria, right-wing) and decreases it in the Czech Republic (Party of Civic Rights/Zemanovci, social-democratic).Footnote1

Second, negative opinion on the government’s work causes distrust both in president and prime minister in almost all models. This is an interesting finding and indicates that general dissatisfaction with government’s performance impacts the presidency as well. Two exceptions do, however, occur as the Czech and Lithuanian presidents are not affected by dissatisfaction with the government. Interestingly, at the time of the survey there was a cohabitation period in the Czech Republic, i.e. when the president’s party was not represented in the cabinet. Under cohabitation, it might be easier for the presidents to distance themselves from the government’s policies (e.g. Elgie Citation2011). In the other cases, the president’s party was included in the cabinet, possibly leading to distrust in president as well. In Lithuania, in turn, the president’s non-partisan status may favour the president in this case.

Third, not supporting the president’s party turned out to be a statistically significant factor in most models if the president had party affiliation, yet the effect seems to be stronger for the prime minister (see, e.g. Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Slovenia), as suggested also by the pooled model. In Slovenia, the party choice did not have any effect on trust in president, while it was stronger in Poland for the president than for the prime minister, both representing the same party (Law and Justice).

Similar patterns are found when conducting the regression models with data from the New Europe Barometer (Citation2001; see Appendix ). First, the explanatory power of the sociodemographic variables (age, gender, education and income) is weak and inconsistent and trust in both institutions is strongly associated with respondents’ views towards democracy and the level of trust in other citizens. Second, political and party-related variables work as explanatory factors for both trust in president and trust in prime minister. Similarly, as in previous analysis, in a situation where the president’s party is represented in the cabinet (no cohabitation), both trust in president and trust in prime minister suffer from negative opinions on the government’s performance (see Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia).

In the context of the partisan dimension, some inconsistencies do, however, occur. First, the impact of dissatisfaction with the government’s work during cohabitation in Bulgaria and Poland is insignificant not only in terms of trust in president but also for the prime minister (Models 1, 2, 7 and 8). Second, in the Czech Republic and Lithuania the same variable has a negative impact on trust in president but not on prime minister (Models 3, 4, 5 and 6), even if the incumbent presidents were in both countries formally non-partisan.

Here comes the question of being formally non-partisan but still associated with the government and party politics. For example, the Lithuanian president Valdas Adamkus, although officially independent, was supported by a centrist party in elections and had a conflict with prime minister Gediminas Vagnorius in 1998 related to the government formation process (Pukelis and Jastramskis Citation2021) and the Czech president Václav Havel had his conflicts with the government and was relatively active in government appointments and dismissals and in legislation at the turn of the twenty-first century (Kopeček Citation2023). This may somewhat explain the results, or at least indicate that the non-partisan status of the president does not guarantee higher trust ratings for the president.

As another robustness check, the results of the determinants of trust in president in comparison with trust in government in Finland support the previous findings (see Appendix ). Moreover, satisfaction with the functioning of the democracy and trust in other people increase feelings of trust in president and trust in government, while both institutions are negatively affected by negative opinion on the government’s work and party choice. Additionally, general party closeness and the left–right dimension are not significant explanatory factors either in terms of trust in president or the government. Most sociodemographic variables do, however, show statistically significant results for both institutions as increases in age and better personal economic situation increase trust in president and trust in government. Interestingly, higher level of education seems to even decrease president’s trust ratings, echoing studies suggesting that the impact of economy on political trust might be context specific (Mayne and Hakhverdian Citation2017).

To conclude the results of the additional analyses, first, despite the gap of 15 years between the two surveys (New Europe Barometer Citation2001 and Social-Political Survey 2016 (Ekman, Duvold and Berglund Citation2023a) and different incumbent presidents and prime ministers, the impact of the explanatory factors remained very similar for both institutions and emphasised the context-specific nature of the partisan and political factors on trust in president, supporting the validity of the results of the main analysis. Second, the results in the context of the Finnish president were mainly in line when compared to the CEE countries, despite the systematic differences between the countries in terms of the democratic development and the general level of political trust. Moreover, it seems that even the Finnish presidents with extremely strong trust ratings and relatively weak constitutional powers are affected by respondents’ party preferences. This, again, boosts the compatibility of the empirical input of the study, given that the Finnish president can be viewed as a more neutral figure in comparison with most CEE presidents, not usually intervening in domestic politics.

In all comparisons, models explaining trust in prime minister performed better than those explaining trust in president, which is an intuitive result given the fact that under semi-presidentialism it is the prime minister who is the head of the government with often stronger constitutional powers compared to the president. The significant similarities between the institutions do, however, offer enough evidence to conclude that in the context of political trust, trust in president is not really a different case.

Conclusion

People tend to trust the president more than other political institutions, yet the explanations behind this pattern have remained uncovered. This study addressed this research gap by exploring the individual-level determinants of trust in president in premier-presidential democracies. The focus was on CEE countries that share the same regime type, history of communism and democratic transition at the beginning of 1990s. The starting point was that the “dual executive structure” within the regime type allows the president to stay “above party politics” and not to take part in domestic issues, while the prime minister, who is allegedly a more partisan figure, is forced to be in a less favourable public position. However, this study challenges this idea by offering empirical evidence of the perspective that presidents are not above parties in the eyes of the citizens.

The results of the empirical analysis show that the same causal mechanisms that apply to more partisan institutions (in this case, the prime minister) touch the presidency as well. Moreover, while some general factors associated with political trust, such as satisfaction with the functioning of the democracy and social trust seem to apply to trust in president as well, the sociodemographic dimension (age, gender, education and income) produced weak and inconsistent results. The most important result of this study is that trust in president is clearly affected by party preferences and political factors, such as the party choice and opinions on the government’s work. The results are in line with the earlier literature emphasising that political trust is more connected to political factors rather than social or economic factors (e.g. Norris Citation1999).

The country comparison also revealed that in terms of political factors and party preferences, trust in president is to some extent more context specific than trust in prime minister. For example, while prime ministers were almost without exceptions affected by the respondent’s party choice and negative opinion on the government’s work, there was more variation between the individuals in terms of trust in president. For example, the impact of supporting the president’s party was not as systematic as in the prime minister’s case. President’s party thus matters, but not supporting the president’s party does not automatically turn into distrust in president. Second, negative opinions on the government’s work seemed to decrease the president’s trust ratings, but not necessarily if the president’s party is not represented in the cabinet (i.e. during cohabitation), which needs further attention in future studies.

This does not mean that the president would not enjoy the “benefits” of the office, but rather that the president’s party background is not irrelevant for the citizens in premier-presidential regimes, despite the symbolic features associated with the institution. Moreover, presidents’ relatively higher popularity and trust ratings indicate that even when the people do not trust other political institutions, they might still trust the president, but not “automatically” if they come from a different political camp.

Although merely scratching the surface of the well-researched topic of political trust, this study examined it from a new angle, offering empirical evidence of public opinion on presidents in the context of European semi-presidential regimes with a dual executive. This brings us closer to understanding what drives trust in president in semi-presidential regimes. However, future studies should focus on understanding this puzzle from the perspective of presidency-centered versus president-centered factors (Hager and Sullivan Citation1994), and through closer analysis of the context-specific explanations and mechanisms behind public opinion on presidents in the CEE countries, and outside the region.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my PhD supervisors and colleagues at Tampere University and Dalarna University for their helpful comments to improve this work, as well as participants at the 2023 ECPR Joint Sessions in Toulouse where a previous version of this article was presented.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maarika Kujanen

Maarika Kujanen is a PhD student at Tampere University. Her research focuses on public opinion on political executives, semi-presidentialism and presidential elections. She has published articles for example in European Political Science Review, Political Studies Review and International Political Science Review.

Notes

1 Party family categories are from Parliaments and Governments Database (ParlGov), available here: https://www.parlgov.org/.

References

- Åberg, Jenny, and Thomas Sedelius. 2020. “A Structured Review of Semi-Presidential Studies: Debates, Results and Missing Pieces” British Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 1111–1136. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000017.

- Anckar, Carsten. 2022. Presidents, Monarchs, and Prime Ministers. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bäck, Maria, and Elina Kestilä-Kekkonen. 2019. “Poliittinen ja Sosiaalinen Luottamus: Polut, Trendit ja Kuilut.” Valtiovarainministeriön Julkaisuja 2019:31. Accessed August 3, 2023. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-367-012-9.

- Beardsworth, Richard. 2017. “Towards a Critical Concept of the Statesperson.” Journal of International Political Theory 13 (1): 100–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755088216671736.

- Brunclík, Miloš, and Michal Kubát. 2019. Semi-presidentialism, Parliamentarism and Presidents: Presidential Politics in Central Europe. London: Routledge.

- Catterberg, Gabriela, and Alejandro Moreno. 2005. “The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18 (1): 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edh081.

- Doyle, David, and Robert Elgie. 2016. “Maximizing the Reliability of Cross-National Measures of Presidential Power.” British Journal of Political Science 46 (4): 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000465.

- Duvold, Kjetil, and Thomas Sedelius. 2022. “Presidents between National Unity and Ethnic Divisions. Public Trust Across the Baltic States.” Journal of Baltic Studies 54 (2): 175–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2022.2064523.

- Easton, David. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: John Wiley.

- Easton, David. 1975. “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400008309.

- Ekman, Joakim, Kjetil Duvold, and Sten Berglund. 2023b. “Baltic Barometer 2014 (Public Opinion Data: Representative Samples of the Adult Population in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, including the Russian-speaking and Polish minorities) (Version 1)” (dataset). Södertörns högskola. https://doi.org/10.5878/vam5-jw90.

- Ekman, Joakim, Kjetil Duvold, and Sten Berglund. 2023a. “Multi-Country Social-Political Survey 2016 (Public Opinion Data: Representative Samples of the Adult Population in Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia) (Version 1)” (dataset). Södertörns högskola. https://doi.org/10.5878/jr5z-c660.

- Elgie, Robert. 2011. Semi-Presidentialism. Sub-Types and Democratic Performance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, Paul Tap, and Raluca Farcas. 2023. “Informal Power and Short-Term Consequences: Country Presidents and Political Parties in Romania.” Political Studies Review. https://journals-sagepub-com.libproxy.tuni.fi/doi/full/10.1177/14789299231187220.

- Goubin, Silke, and March Hooghe. 2020. “The Effect of Inequality on the Relation between Socioeconomic Stratification and Political Trust in Europe.” Social Justice Research 33 (2): 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-020-00350-z.

- Grönlund, Kimmo, and Sami Borg. 2019. “Finnish National Election Study 2019.” Finnish Social Science Data Archive. Accessed August 3, 2023. http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:fsd:T-FSD3467.

- Hager, Gregory L., and Terry Sullivan. 1994. “President-Centered and Presidency-Centered Explanations of Presidential Public Activity.” American Journal of Political Science 38 (4): 1079–1103. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111733.

- Jastramskis, Mažvydas. 2021. “Explaining the Success of Non-Partisan Presidents in Lithuania.” East European Politics 37 (2): 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1756782.

- Jastramskis, Mažvydas. 2022. “Foreign Policy Preferences and Vote Choice under Semi-Presidentialism.” Political Research Quarterly 76 (2): 899–914. https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129221119201.

- Jastramskis, Mažvydas, and Lukas Pukelis. 2023. “Routine Presidential Activism by Going Public under Semi-Presidential and Parliamentary Regimes.” Political Studies Review, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299231185453.

- Köker, Philipp. 2017. Presidential Activism and Veto Power in Central and Eastern Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan

- Kopeček, Ludomír. 2023. “Opportunities and Limits of Presidential Activism: Czech Presidents Compared.” Politics in Central Europe 19 (4): 695–724. https://doi.org/10.2478/pce-2023-0032.

- Kujanen, Maarika. 2024. “Popularity and powers: comparing public opinion on presidents in semi-presidential and presidential regimes.” European Political Science Review 16 (2): 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000280.

- Mayne, Quinton, and Armen Hakhverdian. 2017. “Education, Socialization, and Political Trust.” In Handbook on Political Trust, edited by Sonja Zmerli and Tom WG. Van der Meer, 176–196. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Metcalf, Lee. 2000. “Measuring Presidential Power.” Comparative Political Studies 33 (5): 660–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414000033005004.

- Miller, Arthur H., and Ola Listhaug. 1990. “Political Parties and Confidence in Government: A Comparison of Norway, Sweden, and the United States.” British Journal of Political Science 20 (3): 357–386. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400005883.

- Mishler, William, and Richard Rose. 1999. “Five Years After the Fall: Trajectories of Support for Democracy in Post-Communist Europe.” In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government, edited by Pippa Norris, 78–99. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mishler, William, and Richard Rose. 2001. “What Are the Origins of Political Trust?” Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034001002.

- New Europe Barometer. 2001. “NDB VI Autumn. Dataset SPP 364.” CSPP School of Government & Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde. Available at: https://www.cspp.strath.ac.uk//nebo.html.

- Newton, Kenneth. 1999. “Social and Political Trust in Established Democracies.” In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government, edited by Pippa Norris, 169–187. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Newton, Kenneth, and Sonja Zmerli. 2011. “Three Forms of Trust and Their Association.” European Political Science Review 3 (2): 169–200. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773910000330.

- Norris, Pippa. 1999. Critical Citizens Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Norris, Pippa. 2011. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, Pippa. 2017. “The Conceptual Framework of Political Support.” In Handbook on Political Trust, edited by Sonja Zmerli and Tom W. G. Van der Meer, 19–32. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Ponder, Daniel E. 2018. Presidential Leverage: Presidents, Approval, and the American State. Sanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Pukelis, Lukas, and Mažvydas Jastramskis. 2021. “Prime Ministers, Presidents, and Ministerial Selection in Lithuania.” East European Politics 37 (3): 466–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2021.1873776.

- Raunio, Tapio and Thomas Sedelius. 2020. Semi-Presidential Policy-Making in Europe: Executive Coordination and Political Leadership. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sedelius, Thomas, and Olga Mashtaler. 2013. “Two Decades of Semi-Presidentialism: Issues of Intra-Executive Conflict in Central and Eastern Europe 1991–2011.” East European Politics 29 (2): 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2012.748662.

- Shugart, Matthew Soberg, and John M. Carey. 1992. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional design and Electoral Dynamics. West Nyack: Cambridge University Press.

- Siaroff, Alan. 2003. “Comparative Presidencies: The Inadequacy of the Presidential, Semi-Presidential and Parliamentary Distinction” European Journal of Political Research 42 (3): 287–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00084.

- Söderlund, Peter, and Elina Kestilä-Kekkonen. 2009. “Dark Side of Party Identification? An Empirical Study of Political Trust among Radical Right-Wing Voters.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 19 (2): 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457280902799014.

- Tavits, Margit. 2009. Presidents with Prime Ministers: Do Direct Elections Matter? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Torcal, Mariano. 2017. “Political Trust in Western and Southern Europe.” In Handbook on Political Trust, edited by Sonja Zmerli and Tom W. G. Van der Meer, 418. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Van der Meer, Tom W. G., and Sonja Zmerli. 2017. The Deeply Rooted Concern with Political Trust. 1–16 Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Závecz, Gergõ. 2017. “Post-communist Societies of Central and Eastern Europe.” In Handbook on Political Trust, edited by Sonja Zmerli and Marc Hooghe. Colchester: ECPR.

- Zmerli, Sonja, and Marc Hooghe. 2011. Political Trust: Why Context Matters. Colchester: ECPR.

- Zmerli, Sonja, and Tom W. G. Van der Meer. 2017. Handbook on Political Trust. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Appendix

Table A1. Determinants of trust in president and trust in prime minister, New Europe Barometer (Citation2001), country-level OLS models.

Table A2. Determinants of trust in president and trust in government, Finnish National Election Study (2019), OLS models.