ABSTRACT

After decades of leftist quiescence in Croatia, new social movements have created viable political alternatives. This paper analyses the New Left's electoral support using 2021 survey data. The findings show greater support from younger, urban, and culturally liberal individuals, who do not favour increased state market intervention. While some New Left factions support neoliberal policies, this stance must be viewed in the context of high corruption in Croatia, as New Left voters care about socio-economic inequality. These findings align with recent qualitative studies, suggesting further research into the links between corruption, individual attitudes, and support for the New Left.

Introduction

The ascent of illiberal right-wing parties in post-communist countries since 2008 has sparked significant democracy concerns among scholars and citizens. Political responses to the Global Financial Crisis varied between older EU member states and newer ones (Kriesi and Pappas Citation2015). While Southern European states initially leaned left, post-communist countries largely favoured right-wing options, voting for political parties that exhibited illiberal tendencies shortly after their respective elections (Kelemen Citation2017). Yet, in recent years, New Left political parties have emerged in post-communist countries, securing parliamentary seats as evidenced by the Left in Slovenia (Levica), We Can in Croatia (Možemo), the Left in North Macedonia (Levica) and Green-Left Coalition in Serbia (Zeleno-Leva Koalicija Kralj Citation2022; Milan and Dolenec Citation2023).Footnote1

The sustained influence of right-wing parties has prompted a plethora of research into voting behaviour and the factors contributing to their success (Muis, Brils, and Gaidytė Citation2022; Santana, Zagórski, and Rama Citation2020; Zagórski and Santana Citation2021). Moreover, radical right parties in Central Eastern Europe have received more scholarly attention than the New Left, which is tied to the novelty of the New Left (Buštíková Citation2020; Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023; Minkenberg Citation2017; Pirro Citation2015; Santana, Zagórski, and Rama Citation2020; Zagórski and Santana Citation2021). As Gomez and Ramiro (Citation2023, 23) state, the recent success of a novel form of New Left parties in post-communist Europe could potentially signify the onset of a new chapter in post-communist party politics and the establishment of truly left-wing political parties, which deserves our scholarly attention.

Prior research on this region expected distributive conflicts and the experience of the 1990s to strengthen the socio-economic cleavage, and therefore, to the emergence of left-wing political parties. However, until relatively recently, this has not been the case, with the partial exception of the Czech Republic and Slovenia (Dolenec Citation2012; Zakošek Citation2001; Citation1998). Despite prolonged leftist inactivity in the Yugoslav successor states, recent protests and the emergence of new social movements have coalesced into political entities. This transformation is most clearly exemplified by the green-left coalition in Croatia between three leftist parties (i.e. Možemo, Nova Ljevica and OraH), securing parliamentary representation for the first time since 1991.

In comparison to their Western counterparts, left-wing actors face numerous obstacles in the electoral arena. Beyond the formidable financial and institutional challenges, left-wing actors are frequently subjected to attacks and instances of violence in Croatia, whereby the state of democracy is particularly dire in the Yugoslav successor states (Bieber Citation2018; Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021; Kralj Citation2022). The legacy of war and the predominance of cultural identity issues in the electoral discourse render electoral mobilisation along socioeconomic lines challenging, discrediting the left for its link with Yugoslavia and depicting it as being anti-Croatian (Glaurdić and Vuković Citation2016; Jou Citation2010). Moreover, the pervasiveness of corruption further complicates the electoral competition, creating an uneven playing field between established political parties and new entrants into the political arena (Kralj Citation2022; Vukelić and Pesˇić Citation2023). Thus, the odds are strongly stacked against the emergence, let alone the electoral success, of left-wing political parties in the post-Yugoslav context.

Consequently, the pivotal question that emerges is: Who supports the New Left in Croatia? Given that Croatia was formerly part of the Yugoslav socialist federation, an analysis of the electoral behaviour presents a unique opportunity to gain insights into the driving forces behind New Left-wing voters in the post-socialist context. Unlike other Eastern European systems, Yugoslavia’s distinct socialist model fostered social movements. However, political opportunities varied widely among post-Yugoslav republics: Slovenia and pre-war Croatia bore more similarities to other Central Eastern European countries, while parts of Serbia and North Macedonia aligned more with other Southeast European states in terms of their political opportunity structure (Fink-Hafner Citation2015; Petrović Citation2024). Moreover, post-Yugoslav successor states are typically underrepresented in post-communist party politics studies due to data limitations. In addition, since the New Left has its roots in recent social movements and has only transformed into political parties in the last couple of years, the datasets represent one of the first attempts to collect data on the attitudes of the new left-wing voters.

This paper reveals that supporters of the New Left typically espouse culturally liberal attitudes, exhibit lower levels of religiosity, and tend to reside in urban areas, aligning thus with findings on features that characterises the West European radical left (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023). Surprisingly, the findings report no statistical significance of two items measuring economic attitudes. However, individual’s perception of inequality matters for New Left vote. This paper contributes to the contemporary body of literature on party politics and democratisation, with a specific focus on new social movements and the New Left in the South-eastern European context. It corroborates the qualitative insights of prior studies while concurrently providing empirical evidence pertaining to the micro-level factors that influence individuals’ attitudes and support for the New Left within Croatia (Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021; Kralj Citation2022; Vukelić and Pesˇić Citation2023).

The remainder of this paper is structured into five distinct sections. Sections 2 and 3 undertake a comprehensive review of electoral dynamics and existing explanations for the absence of left-wing political initiatives and the salient cleavages within Croatia. Section 4 outlines the research methodology, while Section 5 presents the empirical findings. The paper concludes by summarising the results and identifying avenues for future research.

Electoral dynamics and the New Left in Croatia

Defining political parties as part of the New Left necessitates analysing their origins and ideological characteristics (Backes and Moreau Citation2008; March Citation2011). According to March (Citation2008; Citation2011), Radical, Extreme and New Left parties are part of the “Far Left” political spectrum, with the first two party groups differing from the latter in that they generally advocate fundamental changes to capitalism, supporting as well grassroot democratic structures. Thus, the New Left, which emerged after the 2008 GFC in the post-Yugoslav successor states, distinguishes itself from the Old and Radical Left in its lack of a radical anti-capitalist agenda and its general acceptance of liberal democracy (Pešić and Petrović Citation2020, 2–3). Economic inequality remains a common focus across all new left-wing denominations, with New Left parties equally problematising issues that typically emerged from social movements, like feminism, disarmament, environmentalism, or minority rights (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023, 9; Fagerholm Citation2017). However, it is important to clarify that differences among the New Left parties in the post-Yugoslav countries exist. The Slovenian Left might be more closely aligned with the Radical Left, while in Croatia, the Left represents a blend of Left-wing and Green Left policies, indicating a slightly more moderate stance.Footnote2

One of the leading New Left parties in contemporary Croatian politics is the 2019-founded party Možemo (We Can). In its party manifesto, Možemo advocates, inter alia, for environmentalism, policies that decrease all sorts of inequality, a larger role of the state in the economy, public housing and a reform of the health care sector, reduction of corruption and clientelism, decentralisation as well as minority rights (Možemo Citation2024). The party is currently part of a leftist-green coalition, consisting of the “New Left” party (Nova Ljevica) and the green alternative (OraH).Footnote3 The genesis of this coalition should be understood within the context of civil society development, particularly the social movements that arose after the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008. These movements emerged in response to the loss of homes and the enduring adverse effects of the privatisation process and neo-liberal policies implemented by the Croatian government since the dissolution of socialist Yugoslavia (Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021; Katsambekis and Kioupkiolis Citation2019). Thus, the GFC in 2008 exacerbated the plight of already impoverished societies grappling with existential uncertainty regarding jobs and housing (Milan and Dolenec Citation2023). According to Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković (Citation2021), household debt surged between 2000 and 2018, rising from 15.8% to 40% in Croatia. While these figures may not appear exceptionally high compared to other European nations, the risk of poverty and social exclusion are more pronounced in South-eastern Europe compared to other European regions (Celi, Petrović, and Sušova-Salminen Citation2022). Consequently, the loss of homes, the 2008 global financial crisis, and the absence of effective state policies to address these challenges laid the groundwork for the emergence of social movements, which subsequently transitioned into political parties (Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021).Footnote4

The relatively late electoral success of the New Left in post-communist states is tied to several factors. On the one hand, elites of the mainstream left parties (i.e. the SDP) implemented neo-liberal reforms upon assuming power after 2000, emulating patterns observed in other post-communist nations, occupying thus a rightist position on the economic dimension. While the HDZ initiated partial neoliberal economic reforms in the 1990s, war veterans’ groups assumed a pivotal role as a constituency for the HDZ, with the party endorsing expansive welfare measures specifically targeting this demographic. Veterans’ organisations also enjoyed special privileges concerning employment opportunities, state-subsidised loans, and numerous other benefits (Dolenec Citation2017; Henjak Citation2007). Proposals to curtail the benefits for war veterans have consistently faced rejection by all major parties and veterans’ associations (Stubbs and Zrinsˇcˇak Citation2015). On the other hand, the political opportunity structure in post-communist states diverges from that of their Western counterparts, characterised by various challenges ranging from institutional impediments to the official registration of political parties due to substantial financial and logistical barriers. It also encompasses issues such as death threats and restrictions on the freedom of expression and association for leftist activists (Dolenec, Kralj, Balković Citation2021; Kralj Citation2022; Bieber Citation2018). Among the Yugoslav successor states, Slovenia boasts the most favourable political structure for new political parties, exemplified by the left-wing party Levica, which secured parliamentary representation already in 2014 (Dinev Citation2023; Toplišek Citation2019).

Past research on the Croatian party landscape have indicated that the terms “Left” and “Right” were mostly entwined with cultural matters. Therefore, the political arena after Croatia’s authoritarian period has been structured by a very strong polarisation between left and right-wing parties competing over cultural issues, such as the role of religion in society or interpretations of the (pre-) socialist past (Čular Citation1999; Henjak and Vuksan-Ćusa Citation2019; Kasapović Citation1996; Raos Citation2020; Sorić, Henjak, and Čižmešija Citation2023), as well as Croatian national identity and reproductive rights regulation (Henjak, Zakošek, and Čular Citation2013; Jou Citation2010). Dominant camps during the 1990s and after 2000 were on the one hand the nationalist conservative HDZ and on the other hand the culturally liberal Social Democratic Party SDP (i.e. the Croatian communist successor party). The key differentiating factor between the two camps pertained to cultural and identity questions as mentioned above, as well as their stance on cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the extent of welfare provisions for war veterans and their families (Glaurdić and Vuković Citation2016; Stubbs and Zrinsˇcˇak Citation2015). Traditionally, supporters of the mainstream left embodied by the SDP typically demonstrate culturally liberal perspectives, possess higher levels of education, reside in urban areas, and are less religious (Bagić Citation2007; Čular and Gregurić Citation2007; Dolenec Citation2012; Glaurdić and Vuković Citation2016; Jou Citation2010).Footnote5

Despite empirical studies confirming strong preferences for egalitarian policies in Croatia as well as its increasing socioeconomic stratification and rising inequality since the 1990s, economic issues do not serve as a primary driver of political party competition, especially given that the transition process was expected to produce winners and losers (Dolenec Citation2012; Domazet, Dolenec, and Ančić Citation2012; Bagić Citation2007; Čular and Gregurić Citation2007; Štulhofer, Citation2001). Similarly to the Western context, winners would be individuals who benefited from the transition in multiple ways or possessed the skills and assets necessary to thrive in a market economy. Conversely, losers would encompass those who fared worse as a result of the transition, whether due to job and income loss or the inadequacy of their skills in an increasingly globalised market (Čular and Gregurić Citation2007; Kitschelt Citation1992; Kitschelt et al. Citation1999; Rohrschneider and Whitefield Citation2009). Researchers attribute the late emergence of socio-economic cleavage to two key factors. Firstly, the dominance of cultural issues in politics stemmed from wartime impacts in the 1990s, which politicised ethnicity (Dolenec Citation2012; Sorić, Henjak, and Čižmešija Citation2023). This particularly affected regions devasted by war, which had been multi-ethnic and are now stronghold of the HDZ (Glaurdić and Vuković Citation2016). Secondly, the HDZ established strong connections with the electorate through clientelist social security programmes in the 1990s, shaping politics to this day (Čular and Gregurić Citation2007; Vidacˇak and Kotarski Citation2019). It was only after the GFC in 2008 which brought about a substantial worsening of circumstances in the already impoverished society that sparked social mobilisation and new social movements in Croatia, culminating in (inter alia) the New Left, which was able to enter the electoral arena (Milan and Dolenec Citation2023).

Who supports the New Left? Deriving hypotheses for the Croatian context

Since a significant part of the New Left parties in Croatia are based on urban grassroots movements such as “Zagreb is Ours”, (Zagreb je Naš), a notable segment of their supporters are city dwellers who espouse culturally liberal views (Sarnow and Tiedemann Citation2023). Recent qualitative research on the New Left in the South-eastern European region reveals that these new social movements were primarily spearheaded by the educated middle class, with a predominant presence of the youth, students, and urban residents participating in these protests (Dolenec, Doolan, and Tomašević Citation2017; Kirn Citation2018; Kralj Citation2022; Vukelić and Pesˇić Citation2023). In Slovenia, Dinev (Citation2023) shows that the Left (Levica), born out of the protest movement in 2012, garners significant support from urban residents, with its core being educated young people and the middle class. These limited results on the characteristics of New Left voters in the South-East European region appear to partially align with empirical observations from Western European democracies on the New Left (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023).

When it comes to perspectives on cultural matters such as immigration, LGBTQ rights or the role of the church in society, the voter base of the New Left in Western European democracies generally leans towards a libertarian position, prioritising individuals’ freedom (Lachat and Dolezal Citation2008; Oesch Citation2012). Furthermore, voters of the New Left typically support secular, cosmopolitan, and progressive ideals, advocating for policies that promote environmentalism, feminism, and minorities’ rights (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023). With regards to attitudes towards supranational integration, research in the Western European and Eastern European region has presented mixed evidence among the New Left voter base (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023; Gomez, Morales, and Ramiro Citation2016; Wagner Citation2022). Generally speaking, individuals in post-communist Europe exhibit “soft” Eurosceptic attitudes, even among the right-wing populist voters (Muis, Brils, and Gaidytė Citation2022; Stojić Citation2018). Rather than advocating for full departure of their country from the EU, a “soft” Euroscepticism is observed among critical individuals. While critique towards the EU and the EU accession process has been on the rise in Croatia since 2008, the New Left is generally in favour of supranational integration (Blanuša Citation2011; Szczerbiak and Taggart Citation2024). To summarise, previous and related research has found that the New Left voter base in both Western and Eastern European regions tend to hold culturally liberal positions and displays varying degrees of Euroscepticism. Therefore, I expect to find that new left-wing voters in Croatia also lean towards culturally liberal views and exhibit “soft” Eurosceptic attitudes. The following hypotheses evaluate these expectations among new left-wing voters:

H1: Individuals with weaker anti-immigrant attitudes are more likely to vote for New Left political parties than for non-New Left parties.

H2: Individuals with stronger support for LGBTQ-rights are more likely to vote for New Left political parties than for non-New Left parties.

H3: Individuals with weaker Eurosceptic views are more likely to vote for the New Left parties rather than for non-New Left parties.

Concerning the economic dimension, party manifestos of the New Left typically incorporate a state interventionist position advocating for a greater role of the state in the economy and broader society. In the Western European context, voters of the New Left are strongly in favour of economic redistribution and support thus a stronger role of the state in the economy (Oesch Citation2012). Evidence for a state interventionist position with regards to economic policies is however, mixed in the broader post-Yugoslav region. Qualitative research has shown that working-class demands are rather marginal at protests of these new social movements in post-Yugoslav successor states, such as Serbia and Croatia (Kralj Citation2022; Pešić and Petrović Citation2020; Vukelić and Pesˇić Citation2023). However, when looking at the New Left’s party manifesto in Slovenia (i.e. Levica) or in Croatia (i.e. Možemo), the parties clearly supports state interventionism (Dinev Citation2023; Možemo Citation2024; Toplišek Citation2019). Yet, individuals’ subjective perceptions of inequality and experiences of declining social status also appear to play a significant role in shaping their vote preferences (Engler and Weisstanner Citation2021; Häusermann et al. Citation2023; Rooduijn and Brian Citation2018). Hereby, both voters of the New Left and Radical Right do perceive economic inequality as a problem (and might support welfare policies) (Oesch and Line Citation2018), but only for selective in-group members, i.e. native citizens, war veterans, or the elderly, while occupying opposite poles on the cultural dimension (Petrović, Walo, and Fritsch Citation2024; Steiner et al. Citation2023). One explanation pertains to the fact that better educated individuals (i.e. members of sociocultural professions) also problematise sociocultural inequality, i.e. inequalities based on gender, sexual orientation or migration background, advocating therefore for human or LGBTQ rights (Häusermann et al. Citation2023). Thus, following the literature, two hypotheses test economic attitudes and perceptions on inequality on the propensity to vote for the New Left:

H4: Individuals with weaker neoliberal economic attitudes are more likely to vote for the New Left rather than for other political parties.

H5: Individuals with the perception that the gap between the rich and the poor has become bigger in Croatia, are more likely to vote for the New Left parties rather than for non-New Left parties.

Looking at socio-economic characteristics, New Left parties attract significantly higher support from the highly educated middle classes, notably socio-economic professionals (Oesch Citation2012; Rooduijn et al. Citation2017). Concerning age, Oesch argued that the New Left garners notably support from younger individuals than older ones in Western European democracies. Similarly, women tend to show more support for the New Left than men (Oesch Citation2012). Yet, comparing New Left voters to voters of the Old Left, Gomez, Morales, and Ramiro (Citation2016) do not find substantial difference with regard to the effect of age and gender (365-366). The authors argue however that New Left political parties do demonstrate greater appeal among highly educated voters (Gomez, Morales, and Ramiro Citation2016; Oesch Citation2012; Kriesi et al. Citation2008). Moreover, the proportion of non-religious supporters is higher among the New Left supporters, indicating a higher degree of secularisation among this segment of the society (Gomez, Morales, and Ramiro Citation2016). Therefore, the usual variables on socio-economic status, such as education, age, gender, residency, and religiosity, are included in the regression analyses testing their effect on New Left vote.

Data and methods

To address the above-mentioned questions, I draw on original survey data collected in 2021 as part of the INVENT project funded by Horizon 2020.Footnote6 The sampling procedure included online participation, computer-assisted telephone interviews, computer-assisted personal interviews, and personal interviews, conducted by the IPSOS Agency in Croatia during May/June 2021, whereby a total of 1200 respondents aged 18 years or older were sampled (Petrović et al. Citation2024).Footnote7 My target population (i.e. those individuals voting in the election) consists of 680 respondents. I filtered out missing values in any of the used variables, resulting in a final sample of 579 respondents employed for the analysis.

The dependent variable distinguishes between voters for the New Left (Y = 1) and voters of any non-leftist party. Based on the literature on rare events data in logistic models, the decision was made to use conventional logit models (King and Zeng Citation2001). Hence, binary logit models are used to test the hypotheses.Footnote8 The coding of the New Left is based on recent research in Croatia, which consists of “We Can” (Možemo), and the “New Left” (Nova Ljevica, Kralj Citation2022; Milan and Dolenec Citation2023). Out of 680 votes, 121 individuals support the New Left, which makes up 17.8%. Footnote9

Independent and control variables

To assess policy-related motivations behind left-wing voting, I incorporated variables that differentiate between cultural and economic issues. Attitudes toward immigration are gauged by the item asking whether individuals “feel that their way of life is threatened by foreign cultures”. Attitudes concerning LGBTQ rights are quantified using the statement: “Same-sex marriage should be permitted throughout Europe”, while Euroscepticism is evaluated based on the assertion that “It is beneficial/would be beneficial for [Country] to be part of the European Union/It is not beneficial that [Country] is not part of the European Union” (Swimelar Citation2019). Three items are employed to gauge economic issues and the perception of inequality, specifically: “Government regulation of business does more harm than good”, and “The unemployed should not receive benefits if they do not make an effort to find work.” The item on the perception of inequality states that “the gap between poor and the rich has become bigger in [Country]”. All items use a 1–5 scale, with 1 indicating “strongly agree” and 5 indicating “strongly disagree”. In the ensuing analyses, all variables underwent recoding such that higher values signify stronger support.

Additionally, I included standard socio-demographic variables such as income, education, place of residence (urban/rural), religiosity (yes/no), age (measured in years), and gender (female = 1). Income is consistently measured across countries using national deciles, ranging from 1 to 10. Education spans from “no formal education” to “Doctoral degree” and is categorised into three groups, encompassing the lowest category (based on ISCED levels 0-2), the middle category (ISCED levels 3-5) and the highest category (ISCED levels 6–8; see Petrović, Walo, and Fritsch Citation2024). Place of residence (urban/rural) is coded as a dummy variable, with 1 indicating individuals living in a large city, suburbs of a large city or a town/small city, and 0 for others (Muis, Brils, and Gaidytė Citation2022). Social class, and particularly socio-economic professionals are said to be the core of the New Left voters (Häusermann et al. Citation2023 Kralj Citation2022; Oesch and Line Citation2018; Vukelić and Pešić Citation2023;). While the dataset included an open question on the individual’s occupation, a high number of missing values did not allow to include this variable in the regression analyses.Footnote10 Nevertheless, I recoded all the occupations mentioned according to the eight class-scheme of Oesch (Citation2006), and used the available information in the descriptive section below. Lastly, religiosity encompasses individuals who hold religious or spiritual beliefs (=1). Table A1 in the Appendix presents summary statistics, while Table A2 depicts the correlation matrix for all the variables used.

Empirical results

Descriptive results

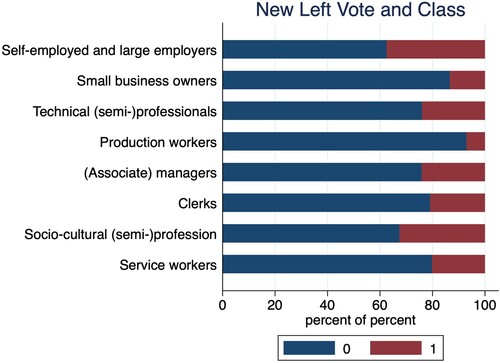

illustrates the primary battery items measuring individuals’ attitudes toward cultural and economic questions, where higher values indicate stronger agreement (i.e. strongly agree). The first item, whether the way of life is threatened by foreign cultures, demonstrates lower approval rates among Non-New Left voters vs. New Left voters. The item measuring LGBTQ rights (same-sex marriage), reveals particular large disparities between the two voting populations. On average, individuals voting for non-New-Left parties do not endorse the statement “same-sex marriage should be permitted throughout Europe” (Swimelar Citation2019). In contrast, individuals from both political spectrums show on average high level of support for the EU. With regards to the economic dimension, both, New Left voters, and Non-New Left voters exhibit rather rightist economic attitudes, with the majority of individuals believing that “government regulation of business does more harm than good” and expressing strong support for the assertion that “people who are unemployed should not receive benefits if they do not actively seek employment”. At the same time, both voter segments do show concern for rising inequality, whereby New Left voters demonstrate slightly higher approval rates than Non-New Left voters. This is consistent with results observed in research regarding the perception and problematisation of inequality (Häusermann et al. Citation2023; Petrović et al. Citation2024). As Häusermann et al. write (Citation2023), individuals voting for the New Left typically see various types of inequalities as problematic, caring thus not only for economic inequalities but also socio-cultural ones, such as gender and race. Consequently, interpreting the graph, individuals voting for the New Left espouse more liberal cultural values and greater support for neoliberal economic policies, problematising however rising inequality in the country. This aligns with findings from other studies on individuals’ attitudes in Croatia (i.e. see for example Dolenec Citation2012; Glaurdić and Vuković Citation2016; Henjak Citation2010, Citation2007).

Figure 1. Battery items (cultural and economic) with 95% confidence intervals for Croatia, 2021. Source: INVENT Database.

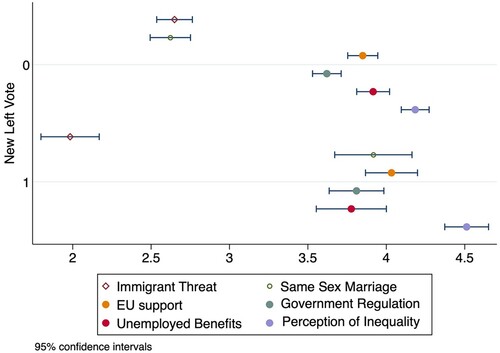

illustrates the eight-class scheme by Oesch (2006) and New Left vs. Non-New Left vote.Footnote11 According to the figure, biggest support for the New Left comes from associate managers and socio-cultural professionals, indicating relatively higher support among the middle classes for the New Left.Footnote12 As previous research on Western Europe showed, socio-cultural professionals are particularly likely to vote for the New Left (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023; Oesch and Line Citation2018). The limited data availability on social class further substantiates existing qualitative studies on the new social movements in Croatia. These studies indicate that these movements predominantly draw participation from better educated individuals, ascribing the movements thus a middle class – based character (Kralj Citation2022; Milan and Dolenec Citation2023).

Regression results

presents the findings from the INVENT dataset regarding new left voting. In all seven models, the dependent variable is the endorsement of a new left-wing political party (=1) compared to non-new left-wing parties. Models 1–6 individually incorporate items measuring policy-related motivations regarding cultural and economic issues. Model 7 is a comprehensive model that includes all variables simultaneously, along with control variables.

Table 1. New Left-wing vote versus non-new left-wing votes in Croatia, 2021.

The first model examines the impact of anti-immigrant attitudes on left-wing party support versus non-support. The negative and statistically significant coefficient indicates that perceiving immigrants as a threat reduces the likelihood of supporting new left-wing political parties compared to non-new leftist ones. The second model assesses the effects of support for LGTBQ rights, revealing a positive and statistically significant coefficient, thus increasing the likelihood of supporting left-wing political parties versus non-support. Both variables, anti-immigration attitudes and support for LGBTQ rights, remain consistent and statistically significant in the full model (Model 7).

The third model explores the influence of EU support on new left-wing voting versus non-voting, demonstrating that this variable does not differentiate between new left voters and non-left ones. Models 4 and 5 both include two items measuring policy-related motivations behind left-wing support. Model 4 examines the impact of advocating for less government intervention in the economy on new left voting versus non-voting, Model 5 analyses the effect of supporting unemployment benefits for individuals who do not actively seek work, while model 6 measures the impact of inequality perception on new left versus non-voting for the new left.

The results reveal that two items measuring economic attitudes, i.e. government intervention and unemployment benefits are not statistically significant. Neither Left-wing nor right-wing economic attitudes seem to be associated with New Left vote. While respondents agree on average with the statement that “government regulation of business does more harm than good”, they disagree with the second item saying that “people who are unemployed should not receive benefits if they do not actively seek employment”. Moreover, both items are not statistically significant. In the Croatian context, it is conceivable that the two items not only assess neoliberal economic attitudes, but also touch upon other issues, such as the country’s high levels of corruption and extensive patronage networks in the economy, which is why individuals tend to be against government intervention in business (Vidacˇak and Kotarski Citation2019; Vučković and Šimić Banović Citation2021). Yet, economic questions are not irrelevant for voters of the New Left: the perception of inequality is statistically significant on a p-value of 0.001. Thus, individuals that problematise economic inequality tend to vote rather for the New Left than for non-New Left parties. Lastly, when examining the control variables, a distinct pattern emerges. The propensity to vote for left-wing parties versus non-left-wing ones rises with education and residence in urban areas (education, however, loses its statistical significance in the full model). Conversely, the propensity diminishes with religiosity. These findings align with more recent research on Western Europe (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023) as well as with qualitative studies in the region (Kralj Citation2022; Vukelić and Pesˇić Citation2023). In contrast, age nor gender are statistically significant in the models.

Conclusion

This paper investigates the New Left’s electorate in Croatia. Drawing on original survey data, the findings in this paper demonstrate that culturally liberal attitudes differentiate between voters of the New Left and non-New Left. Individuals with less-pronounced anti-immigrant attitudes and those who support LGBTQ rights are more likely to support the New Left than non-New Left parties. Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis that individuals with varying attitudes regarding foreign culture and LGBTQ rights do not differ in their inclination to vote for the New Left versus non-New Left parties, providing strong evidence for Hypotheses one and two. Conversely, evidence presented in this paper does not support the third hypothesis: Individuals with strong EU support do not differ significantly from those with weak EU support concerning their backing for left-wing parties. While Croatians are on average pro-EU, New Left voters might also exhibit critical positions towards the EU due to the recent crises, such as the Global Financial Crisis, Migration, or the Covid-19 Pandemic.

In contrast to studies on older democracies, which establish a significant correlation between state interventionist positions and left-wing votes (Gomez and Ramiro Citation2023; Gomez, Morales, and Ramiro Citation2016), the results in this paper provide statistical significance neither for state interventionist nor for neo-liberal economic attitudes and the propensity for New Left vote, suggesting thus weak evidence for hypothesis four. However, the results strongly support hypothesis five: Individuals who agree with the statement that the gap between the rich and the poor has become bigger in Croatia, are more likely to vote for the New Left parties rather than for non-New Left parties. As shown in the section with the descriptive results, economic inequality is seen as a general problem in Croatia, both by New Left voters and voters of other political parties.

Regarding the socio-economic factors, New Left supporters do exhibit differences in terms of their education, place of residence and religiosity. Qualitative studies on social movements and the New Left in Croatia depict supporters as predominantly urban, middle-class, and students, with those more educated being more likely to participate in left-wing social movements (Kralj Citation2022). The quantitative findings in this paper align with the recent literature on social movements and the New Left in the post-Yugoslav successor states.

Finally, the emergence of the New Left and its electoral breakthrough cannot be understood without considering its organic connections to grassroots movements and its struggle for democratisation in Croatia (Bosilkov Citation2021). If these new parties aspire to establish meaningful party-voter linkages, these findings must be considered, serving as motivation for the New Left to formulate suitable economic policies for the future, particularly in light of the salience of economic inequality. The limited evidence for neoliberal economic attitudes among New Left voters suggests potential differences in their preferred policies to address economic inequalities, warranting further scholarly investigation. The results in this paper hold significance when analysing new left-wing voters in a post-socialist context, which might partially differ from that of older democracies. Furthermore, it carries relevance for future studies and surveys conducted in the region, emphasising the need to consider the specific conditions and interpretation of item batteries in surveys.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Simon Bornschier, Hanspeter Kriesi and Jörg Rössel as well as the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on earlier drafts of the article. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Serbian Political Science Associations in Belgrade on October 21st – 22nd, 2023, and Italian Political Science Association in Genova on September 14th, 2023. I would like to thank all conference participants who provided very constructive feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data are blocked until mid-2025.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Valentina Petrović

Valentina Petrović is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Sociology at the University of Zurich. She completed her PhD at the European University Institute in Florence. Her research interests lie at the intersection of comparative politics, political sociology and political economy, with a regional focus on Eastern European countries. She is the author of the book Structural Origins of Post-Yugoslav Regimes. Elites, Civil Society and the State, published in 2024 by Routledge.

Notes

1 Initially, the emergence of North Macedonia’s New Left was interpreted as signs of change in its party system, but the takeover of the party by a controversial figure after 2019 casts a shadow on its political programme due to the leader’s xenophobic statements and his open support for right-wing parties. This turn in the North Macedonian “Left” sets it apart from the other post-Yugoslav cases (Jacobin Citation2022).

2 The author thanks the anonymous reviewer for pointing out this difference.

3 The composition of the left-wing coalitions has evolved over the years, whereby in 2024 it consists of We Can (Možemo), the New Left (Nova Ljevica), and the Green Alternative (ORaH – Sustainable Development of Croatia). The Workers’ Front (Radnička Fronta) was previously a part of the coalition but is no longer involved since 2020.

4 Not only have New Left parties emerged in light of these challenges, but new Right ones as well, such as Ključ Hrvatske, (former Živi Zid) who were particularly active in anti-eviction protests.

5 The Croatian SDP, in contrast to the Serbian communist successor party, significantly enjoyed support from its large Serbian ethnic minority during the 1990s and represented thus culturally liberal positions (Rovny Citation2014). The SDP-led government did, however, implement neoliberal economic policies after the end of the authoritarian regime in 2000 adopting therefore a rightist stance on the economic dimension.

7 The quota used by IPSOS in their sampling methodology involved two-way stratification based on six Croatian statistical regions and six categories of settlement size.

8 The formulation of the question in the INVENT Survey was the following: “If there were a general election tomorrow, which political party would you most likely support? Please select ONLY ONE option.” Abstainers were coded as missing.

9 At the national level, the New Left occupies less than 4% of the parliamentary seats, however, at the local level (i.e., in the City Assembly of Zagreb) the Green-Left coalition controls almost 50% of the seats (Državno Izborno Povjerenstvo Republike Hrvatske Citation2024).

10 Most of the individuals (roughly one-third out of 1201 respondents) who did not mention an occupation are aged between 18–23 and 58–80, encompassing most likely students and retired individuals.

11 Out of 890 respondents who mentioned an occupation, 592 participated in voting, with 110 individuals voting for the New Left. Due to the numerous variables included in the regression analyses and the 8 categories in the class scheme, the occupation variable is unsuitable for regression analysis, see also table A3 in the Appendix.

12 I refrain from interpreting the highest class, since only eight individuals are coded as self-employed professionals (and large employers), whereby 3 of them voted for the New Left. See Table A3 in the Appendix.

References

- Backes, Uwe, and Patrick Moreau. 2008. Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

- Bagić, Dragan. 2007. “DrusˇTveni Rascjepi i Stranacˇke Preferencije na Izborima za Hrvatski Sabor 2003. Godine.” Politicˇka Misao XLIV (4): 93–115.

- Bieber, Florian. 2018. “Patterns of Competitive Authoritarianism in the Western Balkans.” East European Politics 34 (4): 337–354.

- Blanuša, Nebojša. 2011. “Euroskepticizam u Hrvatskoj.” In Hrvatska I Europa: Strahovi I Nade, edited by Ivan Šiber, 11–46. Zagreb: Fakultet političkih znanosti Sveučilišta u Zagrebu.

- Bosilkov, Ivo. 2021. “The State for Which People? The (not so) Left Populism of the Macedonian far-Left Party Levica.” Contemporary Southeastern Europe 8 (1): 40–55.

- Buštíková, Lenka. 2020. Extreme Reactions: Radical Right Mobilization in Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Celi, Giuseppe, Valentina Petrović, and Veronika Sušova-Salminen. 2022. 100 Shades of the EU. Mapping the Political Economy of the Euro Peripheries. Brussels: Transform Europe! And Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

- Čular, Goran. 1999. “The Concept of Left and Right in Empirical Political Science: Meaning, Understanding, Structure, Content.” Croatian Political Science Review 36 (1): 153–168.

- Čular, Goran, and Ivan Gregurić. 2007. “How Cleavage Politics Survives Despite Everything: The Case of Croatia.” Paper prepared for the Panel #19:“Politicising Socio-Cultural Structures: Elite and Mass Perspectives on Cleavages” at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, Helsinki, 1-26.

- Dinev, Ivaylo. 2023. “Barricades and Ballots: Exploring the Trajectory of the Slovenian Left.” East European Politics 39 (6): 609–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2022.2152799.

- Dolenec, Danijela. 2012. “The Absent Socioeconomic Cleavage in Croatia: A Failure of Representative Democracy?” Politicˇka Misao 49 (5): 69–88.

- Dolenec, Danijela. 2017. “A Soldier’s State? Veterans and the Welfare Regime in Croatia.” Anali Hrvatskog Politološkog Društva 14:55–77.

- Dolenec, Danijela, Karin Doolan, and Tomislav Tomašević. 2017. “Contesting Neoliberal Urbanism on the European Semi-Periphery: The Right to the City Movement in Croatia.” Europe-Asia Studies 69 (9): 1401–1429.

- Dolenec, Danijela, Karlo Kralj, and Ana Balković. 2021. “Keeping a Roof Over Your Head: Housing and Anti-Debt Movements in Croatia and Serbia During the Great Recession.” East European Politics, 39 (4): 687–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2021.1937136.

- Domazet, Mladen, Danijela Dolenec, and Branko Ančić. 2012. “Why Power is Not a Peripheral Concern: Exploring the Relationship Between Inequality and Sustainability.” In Sustainability Perspectives from the European Semi-Periphery, edited by Mladen Domazet and Dinka Marinović Jerolimov, 173–194. Zagreb: Edition Science and Society (35). Institute for Social Research.

- Državno Izborno Povjerenstvo RH. 2024. Arhiv. https://www.izbori.hr/arhiva-izbora/index.html#/app/home last online accessed on March 25th, 2024.

- Engler, Sarah, and David Weisstanner. 2021. “The Threat of Social Decline: Income Inequality and Radical Right Support.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (2): 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1733636.

- Fagerholm, Andreas. 2017. “What Is Left for the Radical Left? A Comparative Examination of the Policies of Radical Left Parties in Western Europe Before and After 1989.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 25 (1): 16–40.

- Fink-Hafner, Danica. 2015. The Development of Civil Society in the Countries on the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia Since the 1980s. Ljubljana: Zalozˇba FDV.

- Glaurdić, Josip, and Vuk Vuković. 2016. “Voting After War: Legacy of Conflict and the Economy as Determinants of Electoral Support in Croatia After War: Legacy of Conflict and the Economy as Determinants of Electoral Support in Croatia.” Electoral Studies Studies 42:135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.02.012.

- Gomez, Raul, Laura Morales, and Louis Ramiro. 2016. “Varieties of Radicalism: Examining the Diversity of Radical Left Parties and Voters in Western Europe.” West European Politics 39 (2): 351–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1064245.

- Gomez, Raul, and Louis Ramiro. 2023. Radical Left Voters in Western Europe. London: Routledge.

- Häusermann, Silja, Tabea Palmtag, Delia Zollinger, Tarik Abou-Chadi, Stefanie Walter, and Sarah. Berkinshaw. 2023. “Economic Foundation of Sociocultural Politics: How New Left and Radical Right Voters Think about Inequality.” URPP Equality of Opportunity Discussion Paper Series 33, University of Zurich, 1–53.

- Henjak, Andrija. 2007. “Values or Interests: Economic Determinants of Voting Behaviour in the 2007 Croatian Parliamentary Elections.” Politicˇka Misao XLIV (5): 71–90.

- Henjak, Andrija. 2010. “Political Cleavages and Socio-Economic Context: How Welfare Regimes and Historical Divisions Shape Political Cleavages.” West European Politics 33:474–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402381003654528.

- Henjak, Andrija, and Bartul. Vuksan-Ćusa. 2019. “Interesi ili nešto drugo? Ekonomski stavovi I njihova utemeljenost u društvenoj strukturi u Hrvatskoj.” Revija za Sociologiju 49 (1): 37–60. https://doi.org/10.5613/rzs.49.1.2.

- Henjak, Andrija., Nenad. Zakošek, and Gorab. Čular. 2013. “Croatia.” In Handbook of Political Change in Eastern Europe, edited by S. Berglund, J. Erman, and Kevin Deegan-Krause, 443–480. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Jacobin. 2022. “How North Macedonia’s Promising New Left Became a Hateful Chauvinist Party.” An Interview with Dzejlan Veliu. Accessed July 2, 2024. https://jacobin.com/2022/11/levica-north-macedonia-dimitar-apasiev-takeover.

- Jou, Willy. 2010. “Continuities and Changes in Left-Right Orientations in new Democracies: The Cases of Croatia and Slovenia.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 43:97–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2010.01.007.

- Kasapović, Mirjana. 1996. Demokratska tranzicija i politicˇke stranke. Zagreb: Fakultet politicˇkih znanosti Sveucˇilisˇta u Zagrebu.

- Katsambekis, Giorgos, and Alexandros. Kioupkiolis. 2019. The Radical Left in Europe. Oxon: Routledge.

- Kelemen, R. Daniel. 2017. “Europe’s Other Democratic Deficit: National Authoritarianism in Europe’s Democratic Union.” Government and Opposition 52 (2): 211–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.41.

- King, Gary, and Langche. Zeng. 2001. “Logistic Regression in Rare Events Data.” Political Analysis 9:137–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pan.a004868.

- Kirn, Gal. 2018. “In Search of an Alternative in Slovenia.” Jacobin. Accessed March 1, 2024 https://jacobin.com/2018/07/slovenia-election-sds-janez-jansa-levica.

- Kitschelt, Hebert. 1992. “The Formation of Party Systems in East Central Europe.” Politics & Society 20 (1): 7–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329292020001003.

- Kitschelt, Hebert, Zdenka Mansfeldova, Radoslaw Markowski, and Gabor. Toka. 1999. Post-communist Party Systems, Competition, Representation, and Inter-Party Cooperation. Cambridge.: Cambridge University Press.

- Kralj, Karlo. 2022. “How Do Social Movements Take the ‘Electoral Turn’ in Unfavourable Contexts? The Case of ‘Do Not Let Belgrade D(r)own’.” East European Politics 39 (4): 588–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2022.2128338.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Takis Pappas. 2015. European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lachat, Romain, and Martin Dolezal. 2008. “Demand Side: Dealignment and Realignment of the Structural Political Potentials.” In West European Politics in the Age of Globalization, edited by Hanspeter Kriesi Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey, 237–266. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- March, Luke. 2008. Contemporary Far Left Parties in Europe. from Marxism to Mainstream? Belgrade: Friedrich Ebert Stiffing.

- March, Luke. 2011. Radical Left Parties in Europe. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Milan, Chiara, and Danijela Dolenec. 2023. “Social Movements in Southeast Europe: From Urban Mobilisation to Electoral Competition.” East European Politics 39 (4): 577–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2023.2267991.

- Minkenberg, Michael. 2017. The Rise of the Radical Right in Eastern Europe. Between Mainstreaming and Radicalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Možemo. 2024. Statut. https://mozemo.hr/statut-stranke-mozemo-politicka-platforma/last accessed online on March 29, 2024.

- Muis, Jasper, Tobias Brils, and Teodora. Gaidytė. 2022. “Arrived in Power, and Yet Still Disgruntled? How Government Inclusion Moderates ‘Protest Voting’ for Far-Right Populist Parties in Europe.” Government and Opposition 57:749–778. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.46.

- Oesch, Daniel. 2006 Redrawing the Class Map: Institutions and Stratification in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Oesch, D. 2012. “The Class Basis of the Cleavage Between the New Left and the Radical Right. An Analysis for Austria, Denmark, Norway and Switzerland.” In Class Politics and the Radical Right, edited by J. Rydren, 31–51. London: Routledge.

- Oesch, Daniel, and Rennwald Line. 2018. “Electoral Competition in Europe’s New Tripolar Political Space: Class Voting for the Left, Centre-Right and Radical Right.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (4): 783–807. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12259.

- Pešić, Jelena, and Jelisaveta. Petrović. 2020. “The Role and the Positioning of the Left in Serbia’s “One of Five Million” Protests.” Balkanologie 15 (2): 1–22.

- Petrović, Valentina. 2024. Structural Origins of Post-Yugoslav Regimes. Elites, Civil Society and the State. London: Routledge.

- Petrović, Valentina, Jörg Rössel, Simon Walo, Tally Katz-Gerro, and Pilar Lopez Belbeze. 2024a. “Perceptions of a Shared European Culture Increase the Support for the European Union.” Journal of Common Market Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13619. Online First.

- Petrović, Valentina, Simon Walo, and Larissa. Fritsch. 2024b. Cultural Unity, Economic Divergence: Unraveling Right-Wing Populist Voter Attitudes in the (South-)East. Paper presented at the Swiss Political Science Association in St. Gallen, February 8th-9th, 2024.

- Pirro, Andrea. 2015. The Populist Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe: Ideology, Impact, and Electoral Performance. London: Routledge.

- Raos, Višeslav. 2020. “Struktura rascjepa i parlamentarni izbori u Hrvatskoj 2020. u doba pandemije.” Anali Hrvatskog Politološkog Društva 17 (1): 7–30. https://doi.org/10.20901/an.17.01.

- Rohrschneider, Robert, and Stephen. Whitefield. 2009. “Understanding Cleavages in Party Systems.” Comparative Political Studies 42 (2): 280–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414008325285.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Burgoon Brian. 2018. “The Paradox of Wellbeing: Do Unfavorable Socio-Economic and Sociocultural Contexts Deepen or Dampen Radical Left and Right Voting Among the Less Well-off?” Comparative Political Studies 51 (13): 1720–1753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017720707.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Brian Burgoon, van Elsas Erika, and Herman van de Werfhorst. 2017. “Radical Distinction: Support for Radical Left and Radical Right Parties in Europe.” European Union Politics 18 (4): 536–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517718091.

- Rovny, Jan. 2014. “Communism, Federalism, and Ethnic Minorities: Explaining Party Competition Patterns in Eastern Europe.” World Politics 66 (4): 669–708.

- Santana, Andrés, Piors Zagórski, and José. Rama. 2020. “At Odds with Europe: Explaining Populist Radical Right Voting in Central and Eastern Europe.” East European Politics 36 (2): 288–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1737523.

- Sarnow, Martin, and Norma. Tiedemann. 2023. “Interrupting the Neoliberal Masculine State Machinery? Strategic Selectivities and Municipalist Practice in Barcelona and Zagreb.” Urban Studies 60 (11): 2231–2250. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221101454.

- Sorić, Petar, Andrija Henjak, and Mirjana Čižmešija. 2023. “The Decoupling of Government Sentiment and the Macroeconomy in a Highly Polarised Political Setting.” East European Politics 39 (3): 523–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2023.2164851.

- Steiner, Nils. D., Lucca Hoffeller, Yannick Gutheil, and Tobias. Wiesenfeldt. 2023. “Class Voting for Radical-Left Parties in Western Europe: The Libertarian Versus Authoritarian Class Trade-off.” Party Politics 30 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688231174798.

- Stojić, Marko. 2018. Party Responses to the EU in the Western Balkans. Transformation, Opposition or Defiance? Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stubbs, Paul, and Siniša Zrinsˇcˇak. 2015. “Citizenship and Social Welfare in Croatia.” European Politics and Society 16 (3): 405.

- Štulhofer, Aleksandar. 2001. Nevidljiva ruka tranzicije. Zagreb: Hrvatsko sociološko Štulhoferdruštvo.

- Swimelar, Safia. 2019. “Nationalism and Europeanization in LGBT Rights and Politics: A Comparative Study of Croatia and Serbia.” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 33:603–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325418805135.

- Szczerbiak, Aleks, and Paul. Taggart. 2024. “Euroscepticism and Anti-Establishment Parties in Europe.” Journal of European Integration, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2024.2329634, online first.

- Toplišek, Alen. 2019. “Between Populism and Socialism. Slovenia’s Left Party.” In The Radical Left in Europe, edited by G. Katsambekis and A. Kioupkiolis, 73–92. Oxon: Routledge.

- Vidacˇak, Igor, and Kristijan. Kotarski. 2019. “Interest Groups in the Policy-making Process in Croatia.” In Policy-making at the European Periphery: The Case of Croatia. New Perspectives on South-East Europe, edited by Zdravko Petak and Kristijan Kotarski, 83–105. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Vučković, Valentina, and Ružica. Šimić Banović. 2021. “Who and What Holds Back Reforms in Croatia? The Political Economy Perspective.” Društvena Istraživanja: Časopis za Opća Društvena Pitanja 30 (4): 675–698.

- Vukelić, Jelisaveta, and Jelena Pešić. 2023. “The Unusual Weakness of the Economic Agenda at Protests in Times of Austerity: The Case of Serbia.” East European Politics 39 (4): 645–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2023.2164850.

- Wagner, Sarah. 2022. “Euroscepticism as a Radical Left Party Strategy for Success.” Party Politics 28 (6): 1069–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540688211038917.

- Zagórski, Piotr, and Andrés. Santana. 2021. “Exit or Voice: Abstention and Support for Populist Radical Right Parties in Central and Eastern Europe.” Problems of Post-Communism 68 (4): 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2021.1903330.

- Zakošek, Nenad. 1998. “Ideolosˇki rascjepi i stranacˇke preferencije hrvatskih biracˇa.” In Biracˇi i demokracija, edited by Mirjana Kasapović, Ivan Sˇiber, and Nenad Zakosˇek, 11–50. Zagreb: Alinea.

- Zakošek, Nenad. 2001. “Struktura biračkog tijela i političke promjene u siječanjskim izborima 2000, Hrvatska Politika 1990-2000.” In političkih znanosti Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, edited by Mirjana Kasapović, 99–122. Zagreb: Fakultet.

Appendix

Table A1. Summary statistics.

Table A2. Correlation matrix.

Table A3. Oesch’s Eight-class scheme and New Left Vote in Croatia, 2021.