ABSTRACT

The historic King’s Fund complex in central London was the venue for the Eleventh Annual European CME Forum (11ECF) held 7–9 November 2018. The diverse group of international participants engaged in lively discussion during presentations, workshops, poster displays, a panel discussion and an interactive session with an eloquent local learner. This year’s workshop themes considered the CME acronym as a representation of a Change Management Engine. Each workshop developed these themes by providing practical examples and discussion points for the various stakeholder groups in attendance. Presenters from around the world covered a wide range of topical issues including outcomes planning and evaluation, CPD for CME professionals, collaboration, independence and commercial support, the patient voice, publishing in CME, and CME as a driver of behavioural change. Participants' level of engagement was deemed to be very high, leading to a consensus that the Forum’s second decade has started with a bold commitment to further collegiality among providers to foster collaboration in providing high-quality independent CME/CPD in Europe and beyond.

Many of the attendees at the 11th Annual European CME Forum (#11ECF) were probably unaware of the initial controversy surrounding an architectural feature above eye-level as they passed under the archway in Dean’s Mews leading to the King’s Fund buildings in London where Sir Jacob Epstein’s imposing Madonna and Child can be found. The buildings were previously occupied by the Convent of the Holy Child of Jesus which was damaged by bombing raids over London during World War II and Epstein was commissioned to design a statue to be cast from roofing lead acquired from the bombed building. Three tons of lead were used to cast the statue that appears to hover over the archway ().

Figure 1. Epstein’s Madonna and Child Sculpture, Dean’s Mews, Cavendish Square, London https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/about-us/who-we-are/our-building.

Details of the controversy surrounding the statue have been reviewed by Cronshaw [Citation1].

The 11th Annual European CME Forum, held 7–9 November 2018, was based on the premise that the acronym for Continuing Medical Education (CME) could also represent CHANGE MANAGEMENT ENGINE as follows:

CHANGE: Practical techniques to promote change including educational design, outcomes evaluation and the infusion of education into the professional setting;

MANAGEMENT: Provision and management of resources to fulfil the needs of stakeholders in the CME arena including patients, learners, accreditors, industry and regulators; and

ENGINE: Implementation of innovative ideas and practices.

These three terms were used to provide the framework for three sets of workshops held on Days 1 and 2 of the Forum.

Responses from the pre-meeting needs assessment provided the organisers with a set of topics to be addressed and, in order to provide as much interactivity and engagement as possible, a varied combination of sessions was offered to participants who came from across Europe, the USA, Canada and as far away as Australia and Uruguay.

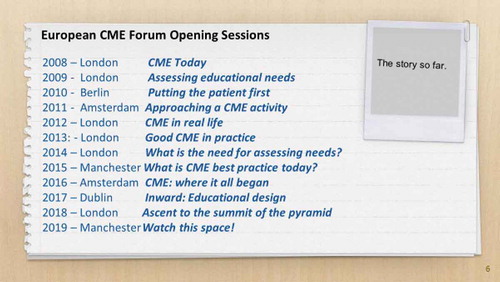

Day 1 began with a new component of the meeting stemming from the responses from the needs assessment conducted after the 2017 meeting. Chris Bolwell and Ron Murray presented a pre-conference orientation session for interested delegates new to CME/CPD and/or first-time attendees. The history of the forum was outlined (see ), and some jargon-busting was conducted to set the scene for subsequent sessions on outcomes, accreditation and the role of industry.

For the opening session of the main conference Don Moore of Vanderbilt University summarised a range of literature sources dealing with his promulgated outcomes framework [Citation2] or “CME pyramid” and suggested that the ideal approach should be to aim for higher level outcomes in trying to achieve an “ascent to the summit” as summarised in and described in his more recent publications [Citation3,Citation4]. Moore moderated table discussions among the delegates on the “backward planning” approach and then contributed to a panel discussion with colleagues Celine Carrera of the European Society of Cardiology and Melania Istrate of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine who presented a number of case studies to illustrate results in practice when applying the backwards planning model to address outcomes at the top four levels of the CME Pyramid, namely Community Health, Patient Health, Performance and Competence. This and other sessions throughout #11ECF were expertly moderated by Chris Elmitt of Crystal Interactive, making full use of the interactive technology provided for the meeting, to poll participants and provide almost instant feedback and summary information.

Figure 3. Ascent to the summit of outcomes measurement [Citation5].

![Figure 3. Ascent to the summit of outcomes measurement [Citation5].](/cms/asset/7f1736f6-3e8e-492e-ac7b-a30a225f1c67/zjec_a_1613861_f0003_oc.jpg)

Day 1 concluded with four concurrent workshops based on the theme of CHANGE. These workshops were led by presenters from European and USA-based organisations as follows.

C1. Accreditation criteria as a roadmap: designing education that matters

Kate Regnier, Executive Vice President of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), put forward some observations on the characteristics of effective education. She pointed out that:

Continuing education is a professional responsibility of healthcare professionals;

Learning can be a fulfilling experience, can promote collegiality and can improve performance;

Clinical practice environments and expectations have changed dramatically while learning environments have changed very little;

Many clinicians have poor self-awareness of their need for performance improvement;

Effective learning is best achieved if it is individualised, including periodic performance comparisons, team- and group-learning, and aggregation of data using appropriate technology.

She then went on to illustrate how the accreditation criteria established by ACCME provide a framework for providers to plan, implement and evaluate all aspects of their educational portfolio. Various criteria can be applied to components such as an organisation’s mission, their educational planning procedures, their ability to ensure independence, and their ability to conduct organisational reflection and improvement. Application of the criteria as a framework is summarised in .

Figure 4. The use of Accreditation Criteria as a change management engine [Citation6].

![Figure 4. The use of Accreditation Criteria as a change management engine [Citation6].](/cms/asset/43a33f83-8e2f-4346-8a20-40a061ed655f/zjec_a_1613861_f0004_oc.jpg)

C2. Medical Societies and CME objectives, challenges and aspirations

Carine Pannetier, Director of Science and Education at the European Respiratory Society, led a workshop with the support of a number of colleagues from European Specialist Societies that allowed participants to consider and discuss the changing culture of medical societies in Europe. A consensus emerged that the focus of many of these societies’ educational activities was moving away from knowledge transfer, towards providing a framework to help improve the performance in practice of their membership. The need for collaboration among societies was emphasised, as well as the importance of outcomes measurements as outlined in Don Moore’s previously described pyramid. A final area identified as an objective was the need for a coordinated approach to the interaction between executive staff and the governing boards of European medical societies.

C3. Professional Development of the Continuing Education professional

Steven Kawczak, outgoing president of the Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions (ACEhp), acknowledged some differences between the USA and Europe in terms of accreditation (provider versus activity) and the role of industry but posited the general applicability of the Alliance’s approach to job descriptions, performance expectations and a career pathway for healthcare education professionals. During his workshop, he introduced the set of competency areas and specific learning competencies within each area that have been developed by ACEhp as a set of skills required by healthcare educators at each stage of their career as outlined in the Dreyfus model shown in . The competencies that are deemed applicable to each stage of the progression from novice to expert were outlined in detail and participants were given the opportunity to work in teams to design strategies for professional development activities for CE professionals based on case studies. The main benefits of using the competency model were listed as:

Incorporating adult learning principles.

Providing a template for planning.

Professional development.

Staffing & Recruiting.

Being the “gold standard” for a Continuing Education professional.

Figure 5. ACEhp’s career path stages for CE professionals [Citation7].

![Figure 5. ACEhp’s career path stages for CE professionals [Citation7].](/cms/asset/2fa98d8f-7e60-4b6e-9cd9-602d270589e0/zjec_a_1613861_f0005_oc.jpg)

C4. CME as the appropriate engine for effective education that changes behaviour

Representatives of the Good CME Practice group (www.gcmep.org) conducted an experiential learning group workshop on “designing appropriate and effective CME” and asked participants to consider the following aspects of appropriate education, which is one of the four pillars of quality and effective CME as set out by the Good CME Practice group [Citation8]:

Is there a gap in clinical knowledge, competence and performance, and need for instruction?

Gap analysis Needs assessment

For whom should the programme be developed?

Characteristics of learners, target audience

What do you want the learners/HCPs to learn or demonstrate?

Learning objectives

How is the medical subject content or skill best learned?

Educational strategies

How do you determine the extent to which learning is achieved?

Outcomes measurement, Evaluation procedures

The main challenges identified during the workshop are summarised in , and the participants were left with the following commitment to change to consider:

Figure 6. Challenges associated with the design and implementation of effective CME that changes behaviour [Citation9].

![Figure 6. Challenges associated with the design and implementation of effective CME that changes behaviour [Citation9].](/cms/asset/5d12c086-1d02-4d1b-91d4-f0b20cf89ec1/zjec_a_1613861_f0006_oc.jpg)

“Following today’s workshop, what is the one thing that you will change when you next plan an educational intervention?”

Day 2 opened with a reflection session presented by the workshop leaders from the previous day’s CHANGE workshops. The common theme that emerged was that incremental changes in the CME arena have been taking place but that much remains to be achieved in engaging both educators and learners using research-based frameworks for professional development and performance improvement in practice.

Oral Presentations

With a record number of posters on display at #11ECF, three authors were invited to make brief oral presentations to the assembled participants during two separate sessions on Days 2 and 3.

Sarah Drumm of the Irish Institute of Pharmacy (IIOP), Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin presented “How do we recognise Continuing Education within a Continuing Professional Development system that is reflective and outcomes-focused? A case study from Irish Pharmacy.”. She provided results from the main elements of their CPD programme i.e. accreditation, portfolio review and practice review showing that:

almost 10,000 certifications have been achieved in CE courses accredited by the IIOP;

Almost 3,000 pharmacists have been selected for an ePortfolio review since 2016;

Results for the 2017/18 review show a high level of engagement;

Feedback from the April practice review was largely positive, with participants commenting that it gave them confidence in their abilities.

In the second oral presentation, “Who am I to evaluate my doctor?” Carolin Sehlbach of Maastricht University described a study looking at how evaluation of physicians by patients might contribute to physician learning and performance. She described three identifiable types of patient:

Active consumers who consider themselves to be in a power equilibrium, able to provide feedback for insight and improvement that is a personal investment for them, and other patients;

Confident consumers who regard their interaction with their physician as representing a dependent power imbalance, trusting the system and doubting any influence they might have;

Outsiders who have limited contact and see themselves as being incapable of making any judgement on physician performance.

Various methods, such as anonymous feedback, were reported that seem to enhance the ability of patients to provide evaluations and improve the doctor–patient relationship.

MANAGEMENT workshops completed the morning of Day 2 as follows:

M1. Can balanced CME truly be achieved without independence?

Toby Borger of Springer Healthcare IME, Thomas Kleinoeder of KWHC, Margarita Velcheva of Kenes Education and members of the Good CME Practice group, collaborated to present athought-provoking workshop, engaging participants in a debate format between those who would argue either for or against the motion that “Balance in CME can only be truly achieved with independence”. The workshop facilitators provided the following Good CME Practice group definitions of these terms.

Balance:

Educational content is fair, unbiased, and reflects the full clinical picture within the framework of the learning objectives.

Independence:

Supported by an independent educational grant, but without direct involvement by industry in faculty selection or content development.

The main conclusions that emerged from this workshop were:

the need to focus on the quality standards that should be applied to CME;

balance is based on quality standards;

learner perception needs to be managed;

standards may well be perceived in the same way by different stake holders but are not always applied the same way;

balance and independence are totally different phenomena.

M2. Collaboration in lifelong learning: making it work

Dale Kummerle, President of the Global Alliance for Medical Education (GAME), and colleagues outlined the history of the organisation and its current plans as shown in .

Figure 7. Strategic Plan for the Global Alliance for Medical Education [Citation10].

![Figure 7. Strategic Plan for the Global Alliance for Medical Education [Citation10].](/cms/asset/6555908f-7970-4ac9-8d6c-d41f60c71a29/zjec_a_1613861_f0007_oc.jpg)

This information was used to frame the workshop by examining means of collaboration, considering the core values of inclusivity, credibility, integrity and transparency as described in the GAME vision and mission statement. The format was a series of table discussions on the following topics:

How to incorporate the core value of transparency into collaboration;

barriers that inhibit collaboration across stakeholders; and

resources needed for collaboration in lifelong learning.

Roving facilitators helped table groups to brainstorm solutions that might be part of best practices in CME/CPD over the next 10 years.

The main conclusions that emerged were

roles and responsibilities must be defined and documented;

importance of transparency among collaborators first, and then to the world;

ownership and partnership must be established;

recognise that one size does NOT fit all;

identify what each member can bring to the table;

should not assume that transparency equates to trust;

resources include logistical resources (time, money, personnel) but also expertise and intellectual resources; and

we should define and differentiate between partnership and collaboration and decide when each is appropriate.

M3. How influential is the patient voice in affecting clinical practice?

Jeanette Andersen, Chair of Lupus Europe highlighted the patient perspective in CME/CPD by posing several questions, the main one being “why include the patient's voice in clinical practice in the first place?” Workshop participants were asked to consider the fact that it is the patient who undergoes treatments and that several published research articles support the premise that patient involvement improves the outcome of the treatment. Further questions for consideration included the following:

Is the medical profession able to implement potentially time-consuming tasks like patient education, or performance monitoring into clinical practice?

Which member(s) of the care team should perform these tasks?

What role can new media play in patient empowerment? (see )

Figure 8. Some considerations for including the patient voice [Citation11].

![Figure 8. Some considerations for including the patient voice [Citation11].](/cms/asset/b90abff1-e75c-41e5-bc62-5c03c203b3eb/zjec_a_1613861_f0008_oc.jpg)

The main conclusion reached was that patients’ perspectives are not taken into consideration often enough. Although the need exists, the means are possible, and the impact is proven, but the will to make it happen is sometimes missing.

M4. Perspectives on international collaboration of accreditors

This MANAGEMENT workshop was facilitated by members of the International Academy of CPD Accreditation – IACPDA who described the current collaboration and alignment between accreditors and regulators who provide oversight of physicians in practice. Initiatives of IACPDA were discussed such as their glossary of terms and definitions, a consensus statement (see ) and the development of substantial equivalency standards. The work of the recently formed Continuing Medical Education-European Accreditors (CME-EA) was also described, and a case study of the new legal framework for CPD in France was presented.

Figure 9. IACPDA’s consensus statement [Citation12].

![Figure 9. IACPDA’s consensus statement [Citation12].](/cms/asset/8c2f7ade-a9e0-4b3e-88ca-cb53f83b1936/zjec_a_1613861_f0009_oc.jpg)

The main takeaway from this workshop was the need to agree on what good education looks like in Europe, no matter where it is offered.

Lunch with a learner

Lawrence Sherman moderated a very illuminating session with Dr Venkat Reddy, a consultant rheumatologist from University College Hospital in London. Dr Reddy commented on the need for self-awareness among learners about their personal educational needs, given the lack of a recognised curriculum in CME. He described his preferred format for CME to be case-based, utilising a range of learning systems but with a requirement for peer discussion to be part of the process. He acknowledged that assessment of the efficacy of CME is difficult to measure but that educators and learners need to have a long-term vision of what they hope to achieve. He emphasised the need to “tell and sell the story” to address clinical problems and reiterated the importance of learning with and from colleagues.

Day 2 concluded with a final set of concurrent workshops on the ENGINE theme.

E1. Intersection of interest: educational needs and commercial support

Representatives from three different pharmaceutical industries provided an overview of best practice CME activity planning, outlining the need for alignment between gaps, learning objectives, educational format and outcomes. They went on to describe the requirements in a grant portal application and companies’ criteria for making decisions on which activities to support. Further discussion dealt with the importance of seeking funds for CME/IME projects that align with the company’s area of interest so that business, patient, healthcare system and healthcare quality needs intersect.

A summary of what industry look for in proposals is shown in .

Figure 10. Industry criteria for awarding funds [Citation13].

![Figure 10. Industry criteria for awarding funds [Citation13].](/cms/asset/a2917d9a-9ff6-4d31-9ba8-8f470d158839/zjec_a_1613861_f0010_oc.jpg)

An important result of the discussion was the importance of disseminating and sharing outcomes data throughout the CME community. Participants were exhorted to consider publishing the results.

E2. Educational design & outcomes measurement: can we afford the resource to do it right?

In a very comprehensive workshop, participants were guided through various phases of planning and implementation of a CME activity and reminded of the principles for quality in medical education (see ) suggested recently by European members of the International Pharmaceutical Alliance for Continuing Medical Education (iPACME) [Citation14].

Figure 11. Principles for quality in industry-based medical education in Europe [Citation15].

![Figure 11. Principles for quality in industry-based medical education in Europe [Citation15].](/cms/asset/377f369e-57c4-4057-832b-d91349fa7bf2/zjec_a_1613861_f0011_oc.jpg)

The principles of instructional design, adult learning principles and outcomes evaluation were the primary components addressed by participants in a series of exercises. Feedback from the participants indicated that qualitative assessment was considered most useful for gap analysis and a telling comment was for the need to “drive the generation of evidence”. The chairs of the session concluded that not all providers in Europe are consistently meeting these expectations.

E3. Why, how and where to publish in CME?

A publisher, an editor and a moderator discussed the opportunities for publishing in the CME field whilst accepting that there is not much of a tradition of publishing about CME in Europe because the CME community is not as accustomed to publishing as physicians in the academic field. The current specialist journals for CME publishing are shown in although many clinical journals do also accept CME/CPD content.

Figure 12. CME Journals [Citation16].

![Figure 12. CME Journals [Citation16].](/cms/asset/3eafd370-9dc2-4d9c-8a3d-868ac1fe6c0d/zjec_a_1613861_f0012_oc.jpg)

Research and publication in the CME field still need to be promoted, and resources were identified to help providers look at ways of pooling outcomes data as a community and publish the results. Participants were encouraged to include budget line items for publishing in grant applications and to act as CME champions and share articles with the broader community so that the CME enterprise is recognised in the wider public arena and data can be used by others.

Day 3

Following reflections on the previous day’s ENGINE workshops, the final oral presentation from the posters saw Barbara Baasch Thomas of the Mayo Clinic describes a study that asked a cross-section of US physicians about past use, current use, and anticipated future use of online learning and simulation-based education. An analysis of the results is shown in .

Figure 13. US physicians’ views on the use of technology in education [Citation17].

![Figure 13. US physicians’ views on the use of technology in education [Citation17].](/cms/asset/3467a41c-dec1-444a-8b93-1b0f5e122585/zjec_a_1613861_f0013_oc.jpg)

An enduring feature of the European CME Forum meetings has been the “CME Unsession” facilitated by Lawrence Sherman where participants can clear up burning questions, uncovered topics, or provide plaudits for aspects of the meeting. All these were achieved this year with the use of technology during the meeting gaining much approval. The size of the meeting was also considered conducive to interactivity and engagement. It was suggested that part of the next needs assessment should look at participants’ ideas on how the workshops should be organised. It was noted that Performance Improvement programmes were becoming more important and that attendees would be willing to participate in a “flipped-classroom” type of activity. The exhortations to publish were reiterated, and the perennial elephant in the room of independence and bias in activities was put forward as a topic for further discussion.

The 11th Annual European CME Forum was rounded off with a panel discussion led by Robin Stevenson (JECME) with Michel Ballieu (BioMed Alliance), Andy Powrie-Smith (EFPIA) and Sophie Wilson (IMP, gCMEp). There was discussion about the important role of the European specialist societies in the provision of CME in Europe, including how they may issue their own Requests For Proposals (RFPs) as funders of education to support third parties in their education efforts.

It was also highlighted that there is still a lack of clarity about the types of organisations which are recognised as providing CME in Europe. There is a growing number of non-society organisations, whether professional companies or not-for-profit education organisations that work independently of industry developing education. There is ongoing confusion between CME providers and Medical Communications agencies which work directly for industry. The CME providers were also challenged that they should “up their game” by demonstrating higher quality levels of outcome and good educational design in their work.

Other salient points that emerged from this session were:

the “moment of the meeting” – the lunchtime learner guest communicating with peers to learn;

the importance of collegiality in the workplace;

given the fast pace of emerging scientific knowledge, the CME profession needs to liaise with industry to share the breadth and depth of this knowledge.

The meeting was closed with details about the evaluations carried out during and after the meeting, which will be used for planning the next meeting.

Details of the presentations and access to resources may be accessed at the European CME Forum website: www.europeancmeforum.eu. The 12th Annual European CME Forum will take place at the University of Manchester, UK, 6–8 November 2019.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Cronshaw JL. Carving a legacy: the identity of Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) [dissertation]. Leeds: University of Leeds; 2010 [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/3259/1/uk_bl_ethos_540786.pdf

- Moore Jr DE, Green JS, Gallis HA. Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29(1):1–12. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19288562

- Stevenson R, Moore Jr DE. Ascent to the summit of the CME pyramid. JAMA. 2018;319(6):543–544. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29356817

- Moore Jr DE, Chappell K, Sherman L, et al. A conceptual framework for planning and assessing learning in continuing education activities designed for clinicians in one profession and/or clinical teams. Med Teach. 2018;40(9):904–913. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30058424

- Moore Jr DE, Carrera C, Melania I, et al. Ascent to the summit of the pyramid: a hands-on guide to implementing the outcomes framework. 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/11ECF-Moore1.pdf

- Regnier K. Accreditation criteria as a roadmap: designing education that matters. 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Change-Regnier.pdf

- Kawczak S. Professional development of the continuing education professional. 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Change-Kawczak.pdf

- Farrow S, Gillgrass D, Pearlstone A, et al. Setting CME standards in Europe: guiding principles for medical education. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(11):1861–1871. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23043468

- Wilson S, Clarkson C, van Brakel D CME as the appropriate engine for effective education that changes behaviour. 11th Annual Europen CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Change-Wilson.pdf

- Kummerle D, Sullivan L, Carrera C, et al. Collaboration in lifelong learning: making it work. 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Management-Kummerle.pdf

- Anderson J. How influential is the patient voice in affecting clinical practice? 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Management-Andersen.pdf

- de Andrade F, Depaigne-Loth A, Griebenow R, et al. Perspectives on international collaboration of accreditors. 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Management-de-Andrade.pdf

- Mason P, Skopowski F, Kummerle D. Intersection of interest: educational needs and commercial support. 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [Accessed 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Engine-Mason.pdf

- Allen T, Donde N, Hofstädter-Thalmann E, et al. Framework for industry engagement and quality principles for industry-provided medical education in Europe. J Eur CME. 2017;6(1):1348876. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29644135

- Kellner T, Thalmann E, Jenkins D Putting effort into design and outcomes evaluation: what a waste of resource? 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [Accessed 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/11ECF-Kellner.pdf

- Rundle N, Sherman L, Stevenson R. Why, how and where to publish in CME. 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [Accessed 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Engine-Rundle.pdf

- Baasch Thomas BL Online learning: do physicians see this in their future? 11th Annual European CME Forum; 2018 Nov 7–9; London, UK. [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://europeancmeforum.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/11ECF-Oral-Baasch-Thomas.pdf