?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Intergenerational families play an important role in providing informal care and support. However, how the intergenerational living arrangements shape the time allocation of young couples remains unclear, and a more comprehensive analysis, where downward support and upward support are distinguished, is needed. Using the “2008 Chinese Time Use Survey” and the seemingly unrelated regression, we document how paid work time, housework and adult care time, and childcare time differ for working-age couples who live with none, relatively young, and relatively old parents. We find that the direction of support changes according to the age of the coresident parents. Compared with those who do not live with parents, couples who live with relatively young parents spend less time on housework and adult care, and those who live with relatively old parents have less paid work time, more housework and adult care time, and those rural wives living with elderly parents even spend less time on childcare. These findings highlight the importance of distinguishing the direction of help for studying intergenerational families and the high time cost of adult care in China.

Introduction

It is common in modern societies that family members live together or live nearby to support each other. In China, the multi-generational family is a family ideal and plays an important function in supporting and providing care to family members (Whyte Citation2004). The phenomenon of parents living with married children is more common in China than in Western societies. In 2011, 41% of China’s population over 60-years-old lived with children.Footnote1 In contrast, the percentages of France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States were 10.2, 6.9, 27.4, 10.9, and 19.4%, respectively (United Nations, Population Division Citation2017).

Usually, married adult children (young couples) live with their parents for two reasons. The first is to provide upward support to the older generation. In a developing and aging society like China, when parents need care, their children are their primary source of support. Intergenerational co-residence implies additional care responsibilities on adult children’s shoulders, and those unpaid caregivers are known to be less active in the labor market and have lower income and deteriorated psychological and physical health (Bauer and Sousa-Poza Citation2015). However, we know little about how adult children’s time use, especially their domestic time, is affected by the assistance provided to the elderly parents.

The second reason is the downward support where parents offer help in domestic work to their adult children. This type of living arrangement is referred to as the “child-centered” co-residence (Chen Citation2005a). This arrangement could be temporary, but as housing prices rise and the fertility levels decline, this intergenerational living arrangement formed of young children, married couples, and relatively healthy and young grandparents is rising (Pilkauskas and Cross Citation2018; Zhang Citation2004). A growing body of research examines how intergenerational co-residence and childcare responsibilities affect employment outcomes of young couples (Chan and Ermisch Citation2015; Lumsdaine and Vermeer Citation2015; Raymo et al. Citation2014; Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016; Smits, Van Gaalen, and Mulder Citation2010; Yu and Xie Citation2018), but research on receiving help from parents on adult children’s domestic time use is limited, and the findings are mixed (Craig and Powell Citation2012; Ta, Liu, and Chai Citation2019; Tan, Ruppanner, and Wang Citation2021).

In a rapidly developing and aging society like China, the issue of intergenerational families is becoming more important. In 2010, there were more than 171 million Chinese people over the age of 60, accounting for 13.3% of the Chinese population. By the end of 2017, this number had reached 241 million (17.4%). Life expectancy has increased from 69.29 years in 1990, 71.96 years in 2000, and 75.24 years in 2010 to 76.79 years in 2019. On the one hand, the rapidly aging Chinese society means that more people are living healthy lives at older ages. They can provide help to support their adult children and grandchildren. On the other hand, the delay in the age of first marriage and childbirth and the one-child policy led to more “sandwich generations,” where childcare and adult care needs compete with each other (Zhang and Goza Citation2006).Footnote2 Studying how co-residing with parents shapes young couples’ paid work, housework, and childcare activities can thus help us understand how Chinese families respond to various challenges that emerged from the family life cycle.

In this article, we provide an encompassing study of the time use patterns in three different family living arrangements in China. These living arrangements include (1) not living with parents (collectively referred to as “nuclear” couples in this article), (2) living with parents under the age of 75 (mainly “child-centered” families), and (3) living with parents aged 75 and over (mainly couples who provide adult care, including “sandwich families” who take care of children and adults at the same time). We analyze time diary data collected in 2008 to report the time spent by urban and rural wives and husbands on paid work, housework and adult care, and childcare.

This paper depicts the lives of working-age couples with different living arrangements in China and clarifies the role of intergenerational co-residence in providing both upward and downward support. Our findings will also have important policy implications by assessing the impact of intergenerational co-residence on the time use of the population of the prime working and childbearing age.

Theoretical model and previous work

Intergeneration relationship changes over the life course. The flow of intergenerational support reverses as parents age (Rossi and Rossi Citation1990). When children are young adults, they are more likely to set up a new house, have a child to look after while working, or need help and guidance in making important life decisions. As parents get older, they leave paid work with their health declining and support network shrinking. Therefore, family needs change with time, and intergenerational support flows to the older generation as parents age.

Several theories explain why different generations support each other. The first is the normative-integrative approach. Different generations support each other to fulfill norms of filial obligation and to exert cohesion and solidarity between family members (Roberts, Richards, and Bengtson Citation1991; Silverstein, Gans, and Yang Citation2006). The altruism perspective is another important explanation for why intergeneration transfers flow from the more resourceful generation to the generation with greater needs. Out of parental altruism, parents support their adult children in the form of providing financial support or assistance in childcare or housework (Logan and Spitze Citation1995). By doing so, their children could achieve a better living standard, continue working while having young children, or devote more time to activities that are more enjoyable than housework. Similarly, children’s altruism explains why adult children provide adult care to parents who have health problems. Focusing on the downward support, the new home economic model that explains the division of labor within a household offers another approach to why parents invest time in domestic work for their children. This model shows that compared to their parents who have retired, adult children who have a comparative advantage in the market (often represented by higher wage rates) invest more time in market labor, and family members who have a comparative advantage in the household will spend more time in home production (Becker Citation1981). Finally, the social exchange theory emphasizes the upward support—adult children provide elderly care to reciprocate the help received from parents in the earlier years (Silverstein et al. Citation2002; Silverstein, Gans, and Yang Citation2006).

Based on the aforementioned theory, living with parents will influence the time use of adult children through intergenerational support. In the early stages of the life cycle, downward support in terms of parental support for child-rearing and housework assistance enables their adult children to work and earn an income. Several studies have documented the positive link between help from the grandparents and maternal work time or labor force participation in France (Dimova and Wolff Citation2008), the United Kingdom (Gray Citation2005), and the United States (Amorim Citation2019). But in Japan, women living with parents are not found to be more likely to work (Asai, Kambayashi, and Yamaguchi Citation2015). Craig and Powell’s (Citation2012) study using Australian time use survey data also reports that the use of grandparental childcare is not associated with increased paid work time for dual-earner couples. As research on China, the findings are also mixed. Grandparental care tends to promote labor supply for mothers with preschool children in urban China, and those who live with elderly parents seem to work longer hours (Du, Dong, and Zhang Citation2019; Li Citation2017; Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016). In contrast, using data from the 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, Yang, Fu, and Li (Citation2016) find that women living with their parents or in-laws are less likely to be in the labor market.

As mentioned above, assistance in domestic work is an important form of downward support. Studies have consistently documented the link between intergenerational co-residence and women’s reduced time spent on housework in Australia, the UK, and China (Chen Citation2005b; Craig and Powell Citation2012; Gray Citation2005; Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016; Ta, Liu, and Chai Citation2019; Tan, Ruppanner, and Wang Citation2021). Studies on childcare time are limited, and the findings are mixed. On the one hand, grandparental care might directly substitute some of the parental childcare. Using the 1991 wave of the China Health and Nutrition Survey, Chen, Short, and Entwisle (Citation2000) examine women with children <6-years-old and find a negative link between mother’s childcare involvement (but not exact hours) and grandparental co-residence. However, studies using Australian time use surveys show that grandparental care is not associated with parents’ childcare time (Bittman, Craig, and Folbre Citation2004; Craig and Powell Citation2012). Using the diary data of dual-earner couples in Beijing, Ta, Liu, and Chai (2019) find that “having help from extended family members can bring additional family care responsibilities.” This null or even positive impact on childcare time for families with grandparents could be attributed to the fact that those who rely on the grandparental childcare may not outsource childcare to institutional or private childcare services, which provide more regular and standard care away from the child’s home. Grandparents’ care with children could also create more opportunities for the couples to interact with their children for social bonding and intimacy within the household (Craig and Powell Citation2012). Moreover, couples in families with grandparents are relatively free from housework chores, and they may prioritize childcare activities.

Research on the time use patterns of adult children concerning upward support is relatively limited, even though those unpaid caregivers provide most of the assistance in daily activities for the elderly in need. Those activities include preparing meals, cleaning, laundry, bathing, dressing, medication, and so on, which are classified as housework and adult care. Previous work focuses extensively on employment outcomes. In industrialized societies, the link between parental care and labor market outcomes is negative but weak, for both women and men (Bauer and Sousa-Poza Citation2015; Bolin, Lindgren, and Lundborg Citation2008; Dautzenberg et al. Citation2000; Lilly, Laporte, and Coyte Citation2010; Van Houtven, Coe, and Skira Citation2013). Notably, in western societies where the values of families are more traditional, the negative effect on employment is stronger for women (Crespo and Mira Citation2014; Naldini, Pavolini, and Solera Citation2016). In China, one study examined the effect of adult care on rural women’s labor force participation in the non-agricultural sector (Fan and Xin Citation2019). This work documented a negative impact. Yang, Fu, and Li (Citation2016) also explain that the negative link between female labor force participation and intergenerational co-residence in China is due to adult care, even though they use the same survey employed in Shen, Yan, and Zeng’s (Citation2016) work, which records a positive link. Another line of research focuses on adult caregivers and highlights caregivers’ psychological distress and feeling of fatigue, but they do not compare caregivers with those who have little adult care responsibilities (Cooney and Di Citation1999; Freedman et al. Citation2019; Zhan Citation2005). A recent work using the China Health and Nutrition Survey reveals that those who live with sick parents spend longer time on housework (Tan, Ruppanner, and Wang Citation2021). So far, we have not found any work analyzing to what extend the time spent on domestic work differs between married children in nuclear families and those living with elderly parents in need.

Previous empirical works on the role of intergenerational families have several limitations. First, intergenerational co-residence is often used as a proxy for grandparental care. The implicit assumption is that most intergenerational living arrangements are to provide support, especially childcare, to the next generation (downward support). This “child-centered” assumption about intergenerational exchange might be more justifiable in industrialized countries with highly developed pension systems and adult care services. Elderly people in those countries are more likely to provide help than to receive help if they live nearby or live with their married children (Bauer and Sousa-Poza Citation2015). Therefore, studies based on data from Western countries find a consistent positive link between living with elderly parents and female labor market performance (Amorim Citation2019; Bratti, Frattini, and Scervini Citation2018; Gray Citation2005). However, studies on Japan have mixed conclusions (Asai, Kambayashi, and Yamaguchi Citation2015; Ogawa and Ermisch Citation1996). Japan is also considered to be a country with high levels of intergenerational co-residence, where 32% of family eldercare recipients were taken care of by their children or spouses of their children (Kolpashnikova and Kan Citation2020). Therefore, whether intergenerational co-residence is an ideal proxy for downward support is questionable in traditional societies. The mix of both downward and upward support in intergenerational families may be the reason why contradicting findings on female labor supply are found in China (Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016; Yang, Fu, and Li Citation2016). Second, previous work rarely examined the impact on domestic work, and among a limited number of studies, the results are highly inconclusive. One of the important reasons is the lack of reliable measurement of the time spent on housework and childcare (Kolpashnikova et al. Citation2021). Without understanding how the performance of intergenerational households in domestic work is different from that of nuclear families, the key mechanism explaining the link between intergenerational co-residence and labor supply remains unconfirmed and the cost of informal care is overlooked.

Chinese intergenerational families and hypotheses

China is a good example for the investigation of the role of intergenerational families in the time allocation of married children. Intergenerational families are common. Although nuclear families are the main type of family, a high proportion (25–33%) of Chinese couples live with their parents, and the proportion is even higher in rural than in urban areas (Chen Citation2005a; Gruijters and Ermisch Citation2019; Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016; Yu and Xie Citation2018). The figures are higher than most of the other countries. This phenomenon corresponds to the Confucian culture that large families are considered prosperous and happy (Chu, Xie, and Yu Citation2011). Another feature of intergenerational families in China is that married children, especially those in rural China, live with or live closer to their husband’s parents (Gruijters and Ermisch Citation2019). This patrilocal co-residence pattern reflects the tradition that women are expected to marry into the husband’s family and provide adult care for their parents-in-law (Cong and Silverstein Citation2014; Zhan Citation2005).

In addition to the reciprocity and altruism models proven by previous studies in China and many other societies, the Confucian concept of filial piety or xiao offers a powerful explanation to Chinese intergenerational relations (Hu Citation2018; Yin Citation2010; Zhang, Gu, and Luo Citation2014). Filial piety obligates children to obey, respect, and support their parents, which means that children should make sacrifices for their parents (Whyte Citation2004). Adult children’s prime responsibility for taking care of elderly parents, including providing appropriate accommodation, is also written in laws or law-binding materials (Chou Citation2011; Li and Tracy Citation1999). Culturally and legally, adult children have the prime obligation to take care of their parents. Given this norm and legal requirement, living with parents is usually to aid parents in need, rather than adult children relying on their parents to support housework and childcare (Logan, Bian, and Bian Citation1998; Xu Citation2021). Therefore, when analyzing intergenerational families in China, it is crucial to differentiate between downward and upward support. In particular, the understudied relationship between upward support and adult children’s time use is worthy of a close examination to evaluate the cost of informal adult care in China.

Traditionally, married children live with their parents to provide care and support in China. 90% of adults in need of adult care were looked after by their family members in 2011 (Chen et al. Citation2018). In addition to the specific cultural value of filial piety and the social and legal pressure to act following these norms, the demand for informal adult care is also intensified due to inadequate state services. State services related to medical care and pension were closely linked to the work unit system and were very limited before 2009 with an immense rural-urban disparity. Although state employees and former employees enjoy subsidized outpatient and inpatient services through government insurance plans, 90% of rural residents bear the full cost of medical care (Li and Tracy Citation1999). The pension system covered very few rural areas. Since 2009, with the expansion of pension coverage and the reform of the health system, the huge rural-urban disparity has only begun to decrease (Chen et al. Citation2017; Meng et al. Citation2019; Shen, Feng, and Cai Citation2018). Formal and professional social care services for the elderly remain extremely underdeveloped (Leung Citation1997; Zhang and Goza Citation2006). Taking together the pressing adult care demand and the ideal of filial piety to sacrifice for parents, we expect that:

Hypothesis 1: compared to those who do not live with their parents, married children who live with relatively old parents spend more time on housework and adult care and less time on paid work and childcare.

Intergenerational families have also adapted to the changing needs of Chinese families. Out of parental altruism and the hope of being cared for by adult children who previously have received parental assistance, Chinese parents invest heavily in their adult children (Bernhardt, Goldscheider, and Turunen Citation2016; Tian and Davis Citation2019). In recent years, as Chinese society has transformed from a socialist economy to a market economy, this downward support has been strengthened. In urban China, the rapid marketization of state-owned sectors led to the shrinking of state-supported childcare services (He and Wu Citation2017; Ji et al. Citation2017). Pre-school childcare services are becoming more expensive. Rising housing prices and living costs make it difficult for families to raise children, and the help of grandparents is increasingly needed to maintain a dual-earner family model. In 2008, around 58% of grandparents report that they have taken care of their grandchildren (Ko and Hank Citation2014). Relying on parents for childcare also fits the economic model. Compared to their parents, couples born in the 1960s to 1980s enjoy a huge comparative advantage in the labor market. In urban areas, a rapidly developing market economy since the early 1990s provides high wages and competitive jobs. In rural areas, agricultural production rewards young, healthy, and strong workers (Zhao and Hannum Citation2019). Accordingly, family wellbeing is maximized when the domestic workload is allocated to the older generation who have little comparative advantage in the labor market than their adult children. We expect that couples who live with relatively young parents receive extensive help in domestic work. As a result:

Hypothesis 2: compared to those who do not live with their parents, married children who live with relatively young parents spend less time on housework and childcare and more time on paid work.

The impact of living with parents on married children’s time use should be heterogeneous. Given the huge rural-urban disparity in formal childcare services, public health, and pension provision, rural families have greater demand for intergenerational support. Taking together, the levels of intergenerational exchange in terms of assistance in domestic work should be higher in rural China. We expect that:

Hypothesis 3: the difference in time use between couples in intergenerational families and nuclear families is greater in rural areas than that in urban areas.

The patrilocal residential feature and the gendered expectation and practice for mother as the primary caregiver for children and the daughter-in-law to be the primary caregiver for elderly parents imply that when married couples receive parental assistance in domestic work and when elderly parents receive help from the married couples, women’s time use should be most affected. We expect that:

Hypothesis 4: the difference in time use between the intergenerational family and the nuclear family of married women is greater than that of married men.

Data and sample

Data are from the 2008 Chinese time use survey. This dataset contains household-level information and time logs from individuals who are between 15- and 74-years-old in households in 10 provinces in China.Footnote3 The provinces surveyed include the relatively developed regions like Beijing, Guangdong, and Zhejiang, as well as regions such as Henan, Gansu, and Yunnan, covering a broad Chinese population. The survey was conducted in May 2008. Respondents were asked to fill in an open diary with intervals of 10 min to report their activities on a weekday and a weekend day. Both rural and urban areas are covered. There are 37,142 individuals with 74,284 diaries.

In our sample, we select married couples (16,082 couples) with a wife who is between 19- and 50-years-old (10,850 couples). These groups of couples are of prime childbearing and working age.Footnote4 After excluding samples with missing values in variables to be used for modeling, the final sample includes 9,359 couples.

One limitation of this survey is that information such as gender, age, education, and their relationship with the household head is collected only for people who are between 15- and 74-years-old in the same household. We identify whether any married member in this household co-reside with their parents or parents-in-law based on household member identifier and relations. We also use the information about whether people are co-present with elderly relatives older than 74 at home on any of the two-diary days to identify those who may live with elderly relatives. These elderly relatives are most likely to be the respondents’ parents or in-laws.

Following the same sample selection procedure, we have cross-checked our sample with the sample from the 2008 China General Social Survey (CGSS), which is a national-representative individual-level survey conducted by Renmin University. The weighted sociodemographic distribution of the two samples is largely similar, but the CTUS sample identifies fewer households with children younger than 19 and is slightly older. Please refer to for more details.

Measures

Dependent variables

We focus on three time-use activities: (1) weekly hours spent on income-generating activities (hereinafter referred to as “paid work time”), (2) weekly hours spent on housework and adult care, and (3) weekly hours spent on childcare. These weekly hours are the sum of week-day hours × 5 and weekend hours × 2 from the weekday and weekend diaries.

Paid work hours include time spent on all types of income-generating activities. These activities include paid jobs, work breaks, job search, unpaid work in a family business or farm, agricultural (planting) production activities, forestry production activities, livestock production activities, fisheries production activities, and so on. In this paper, for two reasons, we enclose a broad definition of paid work time rather than employment status. First, we study people in both urban and rural areas. Being employed has different meanings for people living in urban areas and those in rural areas, especially those in the agricultural sector. In rural areas, many people engage in economic activities, such as family farms, without direct and regular remuneration. Secondly, we believe that paid working time not only reflects the decision whether to engage in paid work but also the time invested for income. Accordingly, we employ a broad definition of “paid work.” For example, if the unemployed spend time looking for jobs, they can record paid working hours. Time spent on family businesses or farms is also counted as paid work time. Besides, we do not find that co-residence with parents is related to urban residents’ employment status. Please refer to for more details. This definition of paid work time is consistent with one study that examined rural women’s paid work hours and co-residence with elderly parents (Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016).

Housework time includes time spent on food preparation, cleaning and laundry, maintenance, and shopping, as in previous studies (Kan et al. Citation2021). We also consider adult care time to measure time spent in providing physical and medical assistance to adult family members. We sum up the time spent on these two types of domestic work to derive a final time spent on housework and adult care.

Childcare time includes time spent on activities such as physical or medical childcare, teaching a child a skill, helping with homework, supervising, accompanying, other childcare, and read to, talk or play with a child. Childcare time is set to zero if there are no children in the household.

Key independent variables

The key predictor indicates whether the selected couples live with or live close to their parents. This variable has three categories. The first category “with ≥75” refers to couples who live with at least one parent who is ≥75-years-old. Because age, gender, and relationship with the household head are only available for those who live together and are between 15- and 74-years-old, this category is derived based on two other questions. The first is a question about whether the respondent is co-present with a family member 75-years-old or over when they record their activities on any one of the two diary days. The second question is the location where the activities are conducted. We limit the location to be at home. The value is 1 if, on any of the two diary days, this individual reported being with a family member aged 75 years or above at home. These co-present elderly family members are most likely to be the parents of the couple who live in the same family.

The second category “with <75” refers to couples living with parents who are all under the age of 75 years. The value is derived from the family relationship grid of the survey questionnaire. The value is 1 if we have identified a parent who is younger than 75 years and is the respondent’s parent.

The remaining couples who are not co-present with a family member older than 74 years at home and are not living with any parent younger than 75 years are classified as “nuclear families” (reference category). The cut-off age of 75 years is mainly due to data limitations. In western industrialized countries, the age of 75 years is found to be the turning point where the direction of intergenerational transmission switches (Kalmijn Citation2019). In developing countries like China, we expect clear upward support if the coresident parents are older than 75 years. We also tried using a cut-off age of 65 years, and the conclusion remains unchanged: there is a clear change in the effect of co-residence depending on the age of parents. However, the sample size of those couples living with parents under the age of 65 years is small, and the standard errors are large.

Other independent variables

Time use pattern is closely linked to a person’s life cycle. We include the respondents’ age and its squared terms. We use the household relationship matrix to identify those who have children under the age of 19 years in the households. We also include the age of children—under the age of 7-, 7-, and 14-years-old, and 15- to 18-years-old. Education is related to time use patterns and intergenerational co-residence (Ma and Wen Citation2016). We include the educational level of both spouses, divided into three categories—below secondary (reference), secondary, and above secondary.

When predicting paid work, housework and adult care, and childcare time, we do not control for employment status for two reasons. First, we believe that employment status has different meanings in urban and rural settings. Second, one’s employment decision may be in the chain of causality between co-residence and time use patterns. Including employment status would undermine the association between co-residence and time use.

Regression models

We use ordinary least squares (OLS) models to predict weekly hours spent on each activity (paid work, housework, and childcare). OLS is shown to provide reliable estimates when analyzing time diary data (Stewart Citation2013). We further follow the seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) system adopted by Gimenez-Nadal and Molina (Citation2013) and estimate the three time-use outcomes for the wife and husband simultaneously (sureg command in STATA) (Zellner Citation1962). Thus, for one couple pair, there are six equations, with each spouse having three-time use outcomes. This system considers joint decisions of the wife and husband and joint decisions on paid work, housework and adult care, and childcare. For example, the time a spouse spends on domestic work can substitute the time the other spouse spent on domestic work.

For a given household “i,”

and

represent the wife’s

and husband’s

time spent on paid work, housework and adult care, and childcare, respectively.

is a vector of the respondent’s and the household’s characteristics, which include not living with parents (reference), living with parents under the age of 75 years, living with parents aged 75 years or above, the educational attainment of both spouses, the respondent’s age and its squared term, parenthood status, and the age of the youngest child. The corresponding error terms to those time use outcomes are set as

and

The equations are as follows:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

for

Error terms in the above equations are assumed to be jointly normally distributed, with no restriction on the correlation. Accordingly, correlations at the couple level in the unobserved predictors of paid work time, housework time, and childcare time are allowed. These error terms are further assumed to be independent across households.

We also include the town-level identifier as dummies to conduct town-level fixed-effect analysis. Therefore, the estimated coefficients reflect results conditional on the same town.

Descriptive statistics

shows the basic statistics of the sample. In urban areas, 9.2% of couples are living with parents under the age of 75 years. The proportion of rural couples is even higher (20.3%). In the two days surveyed, 14.5% and 8.4% of urban and rural couples co-present with family members who are 75 years of age or older at home, respectively.

Table 1. Weighted sample descriptive statistics.

Given that we are conducting a couple-level analysis, we first report information at the couple level. Three-quarters of the urban couples are not living with parents, and the proportion is slightly lower in rural areas. Among urban couples, approximately 40% have no child under the age of 19 in the household, and this number is 50% for rural couples. Most of these couples should have children who leave home to work or study. We have 5,191 and 4,168 couples in urban and rural areas, respectively.

The level of participation in paid work and income-generating activities in rural areas is very high. Over 90% of rural wives and husbands record time spent on income-generating activities on the recorded two days, reflecting the nature of production activities in rural areas. Men spend more time on paid labor than women. The gender gap in housework and adult care and childcare time is huge, and it is greater in rural areas. Rural wives spend almost 20 h/week on housework and adult care, but rural men only spend 4 h on these activities. Women are less educated compared to men in both urban and rural areas.

Next, we report the time use patterns by the living arrangement of the couples in .

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of the weekly paid work hours, housework and adult care hours, and childcare hours across household types, gender, and rural urban samples.

shows that in both urban and rural areas, couples not living with parents and couples living with parents under the age of 75 years spend almost the same time on paid work. Couples living with parents older than 74 years have the least paid working hours. Overall, these differences are modest.

Regarding the weekly housework and adult care hours, couples living with parents under the age of 75 years have the least housework and adult care hours. Couples with relatively old parents have the highest amount of time on housework and adult care. These observations are consistent for both wives and husbands and in both rural and urban areas.

The difference in childcare time is the opposite of the difference in housework and adult care time across the three household types. Women who live with relatively young parents spend the longest time on childcare, which is over 7 h/week. Rural men with different living arrangements spend a similar amount of time on childcare.

The descriptive analysis shows that couples living with parents under the age of 75 years spend less time on housework and adult care and the most time on childcare. This time gap in childcare contradicts Hypothesis 2, which predicts that living with parents reduces the couple’s childcare responsibilities. Notably, couples of different living arrangements are in different stages of life. One important factor is parenthood status. Couples with young children spend the most time on childcare and are most likely to receive help from their parents. Age could be another factor. In the urban sample, the mean and standard deviation of the wife’s age in the three household types are 40 and 6.4 for the nuclear couple, 34 and 6.3 for couples living with parents under the age of 75 years, and 41 and 6.2 for couples living with parents older than 74 years. These numbers for the rural sample are 41 and 5.6 for nuclear households, 33 and 7.0 for couples with parents under the age of 75 years, and 42 and 5.6 for couples with parents older than the age of 74 years. We need to consider those differences to draw a more reliable conclusion. The following multivariate analysis considers the above life-cycle-related factors.

Multivariate results

SUR regression models predict time use patterns for couples with different living arrangements. For this SUR system, the Breusch–Pagan test of independence reports p-values smaller than 0.05 for both the urban and the rural samples. Please refer to the correlation matrix of residuals in for more details. Therefore, we reject the hypothesis that the error terms of the six equations are not correlated with each other. The SUR models will lead to more efficient estimates. We report the results for the urban and rural samples in and , respectively. and present the selected key estimators.

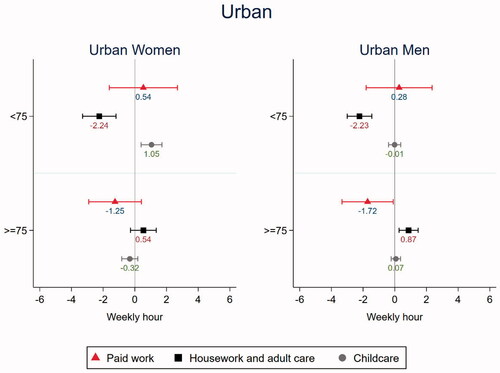

Figure 1. Estimated coefficient of living with parents vs. not living with parents on weekly hours in paid work, housework, and childcare in urban areas.

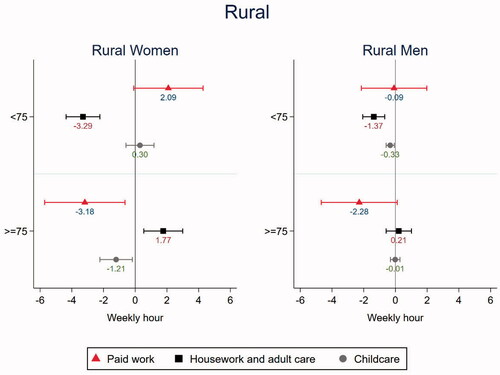

Figure 2. Estimated coefficient of living with parents vs. not living with parents on weekly hours in paid work, housework, and childcare in rural areas.

Table 3. SUR model predicting weekly hours in 2008, Urban sample.

reports the estimated coefficients, and shows the time use differences between intergenerational and nuclear families for urban couples. Compared with people who do not live with their parents, married couples living with relatively old parents reduce paid work time by 1.25 h for women (p = 0.141) and 1.72 h for men (p = 0.038), respectively. The correlations between living with elderly parents and couple’s housework and childcare are modest, though men living with elderly parents spend 0.87 more hours per week on housework and adult care (p = 0.005). Hypothesis 1 is largely supported, except for childcare, but we do not observe that the time use patterns for urban women are more strongly affected by living with relatively old parents, as predicted in Hypothesis 4.

Table 4. SUR model predicting weekly hours in 2008, Rural sample.

As shown in , for urban wives and husbands, living with parents under the age of 75 years has little to do with their hours spent on paid work. Regarding housework time, urban wives and husbands living with parents under the age of 75 years both spend 2.2 h less time (p < 0.001) than those in nuclear households. Interestingly, wives living with relatively young parents spend 1.1 h more on childcare per week (p = 0.002) than those in nuclear households. For the urban sample, only the prediction of housework and adult care time in Hypothesis 2 is supported, and there is little gender difference in the reduced amount of housework and adult care time, as predicted in Hypothesis 4.

presents the estimated coefficients for the rural sample. provides a plot of the key estimates. Compared with those who do not live with their parents, wives living with parents aged 75 years or older spend 3.2 h less time on paid work (p = 0.014), and the estimate for men is 2.3 (p = 0.062). Wives living with those elderly parents also spend 1.77 h more time on housework and adult care (p = 0.005) and 1.21 h less time on childcare (p = 0.021) than those in nuclear households. The cost of informal adult care on rural women’s time use is substantial. There is little difference in rural men’s time spent on domestic work between those who do not live with their parents and those living with relatively old parents. Overall, living with parents has a stronger correlation with rural women’s time use pattern. Hypotheses 1 is supported for rural women, prediction about paid work in Hypothesis 1 is supported for the rural men’s sample. The gender difference in the rural sample also supports Hypothesis 4. The larger impact on time use in the rural areas, as predicted in Hypothesis 3, is primarily observed between women in urban and those in rural areas.

Compared with those who do not live with their parents, rural women who live with relatively young parents spend 2.09 h more time on paid work (p = 0.061) and 3.3 h less time for housework (p < 0.001). Living with parents under the age of 75 years has a limited impact on the childcare time of rural women. Notably, living with parents aged 75 years or over is strongly correlated with rural women’s time use. For rural men, there is little difference in paid work time between those who do not live with their parents and those living with parents under the age of 75 years. Rural men living with those relatively young parents do spend 1.4 h less time on housework (p < 0.001) and 0.33 h less time on childcare (p = 0.013) per week. Hypothesis 2 is supported for the sample of rural women, except for childcare. The gender difference is also consistent with the prediction from Hypothesis 4. Regarding the downward support, the rural-urban difference as predicted in Hypothesis 3, is not obvious. Nonetheless, it seems that the positive association with paid work time is stronger for women in rural areas.

Discussion and conclusion

Despite the prevalence of intergenerational families in China, there is a lack of comprehensive understanding of how adult children’s lives are shaped by this living arrangement. In particular, the time cost on paid work and domestic work of adult children who co-reside and support their elderly parents is still unknown. The shrinking of the state provision of childcare and the extremely underdeveloped adult care services in China call for encompassing research to understand the cost of informal care provided by family members.

In this paper, we document three-time use outcomes for both married women and men across three family types—nuclear families, with parents under the age of 75 years, and with parents aged 75 years or over in both urban and rural areas. This paper completes our understanding of the dual roles of intergenerational families in assisting young couples to reconcile work and family responsibilities and to provide care to the elderly in need.

One of the most consistent findings is that women and men in both rural and urban areas who live with parents under the age of 75 years spend less time on housework and adult care than those who do not live with their parents. The reduced housework time is observed similarly for women and men in urban areas, but the reduction is the largest for women in rural areas. Interestingly, living with parents under the age of 75 years has little impact on paid work time for the urban sample. This observation differs from the finding in some of the previous studies (Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016; Ta, Liu, and Chai 2019). In this article, we employ a broader sample than previous studies (e.g., Du, Dong, and Zhang (Citation2019) only examined mothers with preschool children; Ta, Liu, and Chai (2019) studied only dual-earner couples in Beijing; Shen, Yan, and Zeng (Citation2016) studied only women living with their own parents). The definition of paid work in this paper is also broader than studies that focus on maternal labor force participation (Du, Dong, and Zhang Citation2019; Li Citation2017). For rural women, those who live with relatively young parents work ≥2 h/week than those who do not. It is likely that urban couples in nuclear families have alternatives than parents to maintain their labor market performance. For example, they can outsource domestic work to paid helpers or formal childcare if assistance in domestic work is needed. There is also a potential to underestimate the positive impact on paid work time. We will discuss this later. In summary, living with parents who are relatively young will at least maintain the couple’s paid work time.

Regarding childcare, different from what we have expected from the downward support, urban women who live with parents under the age of 75 years spend more time on childcare than those in nuclear households. For rural women, the difference between nuclear families and those with relatively young parents is minimal. This finding of the urban sample is consistent with the study of Ta, Liu, and Chai (Citation2019) and the Australian time use study (Craig and Powell Citation2012). As discussed previously, with grandparental assistance in housework, couples may spend the saved time on childcare. Nuclear families could outsource childcare through other ways, and this observation may reflect the irregular feature of grandparental care compared to the standard formal childcare services out of the child’s home. Grandparental care may stimulate more interactions between parents and children. If we combine the effect on both housework and adult care and childcare time, the overall time spent on domestic work for couples living with parents under the age of 75 years is still less than those nuclear families.

As the direction of intergenerational support is increasingly moving upwards, intergenerational families play a different role. Compared with nuclear households, women and men living with elderly parents aged 75 years or over have less time on paid labor. The relatively moderate reduction in paid work for the urban sample is consistent with those work conducted in western societies (Bolin, Lindgren, and Lundborg Citation2008; Dautzenberg et al. Citation2000). The reduction in paid work time is larger in the rural areas. This finding echoes those studies that observed a larger negative impact on women’s labor market outcomes in European countries where family values are more traditional (Bolin, Lindgren, and Lundborg Citation2008; Crespo and Mira Citation2014). This also reflects the long hours spend on agricultural production activities, which are more flexible and sensitive to changes in housework chores than non-agricultural jobs (Chen Citation2005b).

The time cost of living with relatively old parents for rural women is huge. Compared with those in nuclear families, rural women living with relatively old parents spend nearly 2 h more time per week on housework and adult care and a 1.2-h less time on childcare. The high time cost of rural women living with relatively old parents reflects the patrilocal tradition and the expectation for the daughter-in-law to provide adult care and assistance in housework to the husband’s parents. This pattern also reveals the conflicting care needs of children and elderly parents in less developed areas. The competitive relationship between grandparent and grandchildren is also found in several studies in low-income countries, where the presence of grandparent, especially the paternal grandparent, is negatively associated with child health, due to resource competition within families (Sheppard and Sear Citation2016; Strassmann and Garrard Citation2011; West, Pen, and Griffin Citation2002).

This article has a few limitations. First, limited by the data, we do not distinguish between couples living with the wife’s and the husband’s parents. Living with the wife’s or the husband’s parents could have different effects on the couple’s power relationship (Cheng Citation2019; Yu and Xie Citation2018). We advise further improvement in data collection to address this issue. Our paper is also a descriptive one, disregarding selection related to both intergenerational co-residence and time use. Past research has shown that couples living with their parents tend to hold more traditional family values (Chu, Xie, and Yu Citation2011). These values may deter women from engaging in paid work or induce them to spend more time on household labor. Accordingly, compared with the currently reported estimates in this article, the coefficients of living arrangements predicting women’s paid work, housework, and childcare time may be more positive, less positive, and less positive, respectively. Nonetheless, previous work has shown that practical needs are the predominant factors in parental co-residence (Chen Citation2005a; Chu, Xie, and Yu Citation2011; Zhan and Rhonda Citation2003). And these factors, such as the presence of a young dependent child, or the unobserved, latent health condition of the elderly parents before living together with their adult children, are either included in our model or are most likely exogenous. Our conclusions are generally consistent with some earlier studies that took advantage of more advanced research designs that this dataset could not achieve (Shen, Yan, and Zeng Citation2016). Finally, the data of the present study do not contain information on the proximity of the parent’s home to the children’s home for parents who do not co-reside with their adult children. This has underestimated the influence of intergenerational support on married children’s daily routine. Non-co-resident children who live close frequently visit their parents (Bian, Logan, and Bian Citation1998; Lei et al. Citation2015), and grandparents living nearby also provide important help in childcare, which alleviate parents’, mostly mothers’ childcare demand (Chen, Short, and Entwisle Citation2000). The advancement in transportation and communication enables the maintenance of intergenerational support over great geographic distance (Litwak Citation1960; Bengtson et al. Citation2002). Studying intergenerational support among family members living apart would offer important supplements to understand extended families in today’s China.

Our paper underscores the importance to consider the direction of support between generations when studying intergenerational families. Previous research underestimated the complexity that the same living arrangement may meet the different needs and goals of Chinese families. Whether parents provide support to the next generation or get help from them will lead to different time use patterns of adult children and have different consequences for urban and rural couples.

The lack of significant gendered impact in the urban sample reflects that the level of gender equality is higher in the urban areas than that in the rural areas. However, given that couples in intergenerational families are most likely to live with the husband’s parents, this similarity suggests that the time costs of the daughter-in-law and son in caring for and living with elderly parents are similar. In terms of downward support, considering the similar reduction in housework and adult care time and the very limited involvement of men in domestic work, urban men benefit disproportionately from co-residing with relatively young parents.

This paper uncovers the negative impact of the lack of adult medical care support on the working-age population and their children, especially in rural areas. The high time cost for rural women who live with elderly parents older than 74 years uncovers the poorer health of rural elderly compared with their urban counterparties. Elderly people in rural areas have little pension together with inadequate medical support. The intensive demand of care and the lack of support may explain why rural women, as non-working caregivers, suffer the most in mental wellbeing (Van Houtven, Coe, and Skira Citation2013). With the deepening of China’s pension and medical system reform, the health condition of rural elderly may benefit substantially, and we look forward to an updated study that records a potentially different time use pattern of intergenerational families.

However, with the change in the demographic structure where fewer children were born per woman, the future generation will have a smaller kinship network to rely upon when help is needed. Future childcare and adult care will face great challenges with the reduction of the supply of informal caregivers. Advanced industrialized societies have sought alternatives such as flexible working or extended paid leave for caring for a dependent (Bolin, Lindgren, and Lundborg Citation2008). Although urban China can learn from these policy innovations, these measures do not apply well in rural China. The situation of inadequate state support for both childcare and adult care is unlikely to improve significantly in the short run given the high expenditure on the provision of care by the public. Chinese families will still have to bear the growing cost of care, and the extensive intergenerational exchange is unlikely to decline in the near future.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muzhi Zhou

Muzhi Zhou is currently a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Oxford and an incoming Assistant Professor at the Urban Governance and Design Thrust, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou). She studies how critical life events, such as marriage or childbirth, reshape people’s lives in the United Kingdom, Europe, and East Asia and factors related to family formation patterns. She also works on how children spend their time and its implications. Her work has been published in Gender & Society, Demographic Research, and Chinese Sociological Review.

Man-Yee Kan

Man-Yee Kan is an Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology, University of Oxford. Her research areas include gender inequalities in the family and the labour market, marriage, the gender division of labour, time use research, welfare and public policy regimes in Western and East Asian societies, and ethnicity and migration. She has been awarded a European Research Council Consolidator Grant under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme for a project which aims to investigate trends in gender inequality in time use in East Asian and Western societies.

Guangye He

Guangye He is an Associate Professor at Nanjing University, Department of Sociology. She earned her PhD from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology in 2016. Her research focuses on family sociology, social stratification, and quantitative methodology in sociology. She has published in Social Science Research, Sociological Studies, Chinese Sociological Review, Chinese Journal of Sociology, China Review, Journal of Contemporary China, and many others.

Notes

1 Data are from the 2000 IPUMS data and the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS).

2 The mean age of first marriage in 2010 is 26-years-old in China.

3 The 10 provinces are Beijing, Hebei, Heilongjiang, Zhejiang, Anhui, Henan, Guangdong, Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu.

4 The minimum legal age of working in China is 16. And the retirement age in non-agricultural occupations in China is dependent on the type of work that you are doing. For professionals/civil servants, the retirement age is 60 for men and 55 for women. The retirement age is 50 for the rest of the female workers in blue-collar occupations in cities.

References

- Amorim, M. 2019. “Are Grandparents a Blessing or a Burden? Multigenerational Coresidence and Child-Related Spending.” Social Science Research 80:132–144. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.02.002.

- Asai, Y., R. Kambayashi, and S. Yamaguchi. 2015. “Childcare Availability, Household Structure, and Maternal Employment.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 38:172–192. doi:10.1016/j.jjie.2015.05.009.

- Bauer, J. M., and A. Sousa-Poza. 2015. “Impacts of Informal Caregiving on Caregiver Employment, Health, and Family.” Journal of Population Ageing 8 (3):113–145. doi:10.1007/s12062-015-9116-0.

- Becker, G. S. 1981. A Treaties on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bengtson V., R. Giarrusso, J. Beth Mabry, and M. Silverstein. 2002. “Solidarity, Conflict, and Ambivalence: Complementary or Competing Perspectives on Intergenerational Relationships?” Journal of Marriage and Family 64 (3):568–576.

- Bernhardt, E., F. Goldscheider, and J. Turunen. 2016. “Attitudes to the Gender Division of Labor and the Transition to Fatherhood: Are Egalitarian Men in Sweden More Likely to Remain Childless?” Acta Sociologica 59 (3):269–284. doi:10.1177/0001699316645930.

- Bian, F., J. R. Logan, and Y. Bian. 1998. “Intergenerational Relations in Urban China: Proximity, Contact, and Help to Parents.” Demography 35 (1):115–124. doi:10.2307/3004031.

- Bittman, M., L. Craig, and N. Folbre. 2004. Packaging Care: What Happens When Children Receive Non-Parental Care? 133–151. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge.

- Bolin, K., B. Lindgren, and P. Lundborg. 2008. “Your Next of Kin or Your Own career? Caring and working among the 50+ of Europe.” Journal of Health Economics 27 (3):718–738. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.10.004.

- Bratti, M., T. Frattini, and F. Scervini. 2018. “Grandparental Availability for Child Care and Maternal Labor Force Participation: Pension Reform Evidence from Italy.” Journal of Population Economics 31 (4):1239–1277.

- Chan, T. W., and J. Ermisch. 2015. “Proximity of Couples to Parents: Influences of Gender, Labor Market, and Family.” Demography 52 (2):379–399. doi:10.1007/s13524-015-0379-0.

- Chen, F. 2005a. “Residential Patterns of Parents and Their Married Children in Contemporary China: A Life Course Approach.” Population Research and Policy Review 24 (2):125–148. doi:10.1007/s11113-004-6371-9.

- Chen, F. 2005b. “Employment Transitions and the Household Division of Labor in China.” Social Forces 84 (2):831–851. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0010.

- Chen, F., S. E. Short, and B. Entwisle. 2000. “The Impact of Grandparental Proximity on Maternal Childcare in China.” Population Research and Policy Review 19 (6):571–590. doi:10.1023/A:1010618302144.

- Chen, T., G. W. Leeson, J. Han, and S. You. 2017. “Do State Pensions Crowd out Private Transfers? A Semiparametric Analysis in Urban China.” Chinese Sociological Review 49 (4):293–315. doi:10.1080/21620555.2017.1298968.

- Chen, X., J. Giles, Y. Wang, and Y. Zhao. 2018. “Gender Patterns of Eldercare in China.” Feminist Economics 24 (2):54–76. doi:10.1080/13545701.2018.1438639.

- Cheng, C. 2019. “Women’s Education, Intergenerational Coresidence, and Household Decision-Making in China.” Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (1):115–132. doi:10.1111/jomf.12511.

- Chou, R. J.-A. 2011. “Filial Piety by Contract? The Emergence, Implementation, and Implications of the “Family Support Agreement” in China.” The Gerontologist 51 (1):3–16. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq059.

- Chu, C. Y. C., Y. Xie, and R. R. Yu. 2011. “Coresidence with Elderly Parents: A Comparative Study of Southeast China and Taiwan.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 73 (1):120–135. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00793.x.

- Cong, Z., and M. Silverstein. 2014. “Parents’ Preferred Care-Givers in Rural China: Gender, Migration and Intergenerational Exchanges.” Ageing and Society 34 (5):727–752. doi:10.1017/S0144686X12001237.

- Cooney, R. S., and J. Di. 1999. “Primary Family Caregivers of Impaired Elderly in Shanghai, China: Kin Relationship and Caregiver Burden.” Research on Aging 21 (6):739–761. doi:10.1177/0164027599216002.

- Craig, L., and A. Powell. 2012. “Dual-Earner Parents’ Work-Family Time: The Effects of Atypical Work Patterns and Non-Parental Childcare.” Journal of Population Research 29 (3):229–247. doi:10.1007/s12546-012-9086-5.

- Crespo, L., and P. Mira. 2014. “Caregiving to Elderly Parents and Employment Status of European Mature Women.” Review of Economics and Statistics 96 (4):693–709. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00426.

- Dautzenberg, M. G. H., J. P. M. Diederiks, H. Philipsen, F. C. J. Stevens, F. E. S. Tan, and M. J. F. J. Vernooij-Dassen. 2000. “The Competing Demands of Paid Work and Parent Care: Middle-Aged Daughters Providing Assistance to Elderly Parents.” Research on Aging 22 (2):165–187. doi:10.1177/0164027500222004.

- Dimova, R., and F.-C. Wolff. 2008. “Grandchild Care Transfers by Ageing Immigrants in France: Intra-Household Allocation and Labour Market Implications.” European Journal of Population 24 (3):315–340. doi:10.1007/s10680-007-9122-x.

- Du, F., X.-Y. Dong, and Y. Zhang. 2019. “Grandparent-Provided Childcare and Labor Force Participation of Mothers with Preschool Children in Urban China.” China Population and Development Studies 2 (4):347–368. doi:10.1007/s42379-018-00020-3.

- Fan, H., and B. Xin. 2019. “Household Elderly Care and Rural Women’s Non-Agricultural Employment.” Chinese Rural Economy 19:1–17.

- Freedman, V. A., J. C. Cornman, D. Carr, and R. E. Lucas. 2019. “Time Use and Experienced Wellbeing of Older Caregivers: A Sequence Analysis.” The Gerontologist 59 (5):e441–e450. doi:10.1093/geront/gny175.

- Gimenez-Nadal, J. I., and J. A. Molina. 2013. “Parents’ Education as a Determinant of Educational Childcare Time.” Journal of Population Economics 26 (2):719–749. doi:10.1007/s00148-012-0443-7.

- Gray, A. 2005. “The Changing Availability of Grandparents as Carers and Its Implications for Childcare Policy in the UK.” Journal of Social Policy 34 (4):557–577. doi:10.1017/S0047279405009153.

- Gruijters, R. J., and J. Ermisch. 2019. “Patrilocal, Matrilocal, or Neolocal? Intergenerational Proximity of Married Couples in China.” Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (3):549–566. doi:10.1111/jomf.12538.

- He, G., and X. Wu. 2017. “Marketization, Occupational Segregation, and Gender Earnings Inequality in Urban China.” Social Science Research 65:96–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.12.001.

- Hu, Y. 2018. “Patriarchal Hierarchy? Gender, Children’s Housework Time, and Family Structure in Post-Reform China.” Chinese Sociological Review 50 (3):310–338. doi:10.1080/21620555.2018.1430508.

- Ji, Y., X. Wu, S. Sun, and G. He. 2017. “Unequal Care, Unequal Work: Toward a More Comprehensive Understanding of Gender Inequality in Post-Reform Urban China.” Sex Roles 77 (11–12):765–778. doi:10.1007/s11199-017-0751-1.

- Kalmijn, M. 2019. “The Effects of Ageing on Intergenerational Support Exchange: A New Look at the Hypothesis of Flow Reversal.” European Journal of Population = Revue Europeenne de Demographie 35 (2):263–284. doi:10.1007/s10680-018-9472-6.

- Kan, M.-Y., M. Zhou, D. V. Negraia, K. Kolpashnikova, E. Hertog, S. Yoda, and J. Jun. 2021. “How do Older Adults Spend Their Time? Gender Gaps and Educational Gradients in Time Use in East Asian and Western Countries.” Journal of Population Ageing.

- Ko, P. C., and K. Hank. 2014. “Grandparents Caring for Grandchildren in China and Korea: Findings from CHARLS and KLoSA.” The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 69 (4):646–651. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbt129.

- Kolpashnikova, K., S. Flood, O. Sullivan, L. Sayer, E. Hertog, M. Zhou, M.-Y. Kan, J. Suh, and J. Gershuny. 2021. “Exploring Daily Time-Use Patterns: ATUS-X Data Extractor and Online Diary Visualization Tool.” PLoS One 16 (6):e0252843. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252843.

- Kolpashnikova, K., and M.-Y. Kan. 2020. “Eldercare in Japan: Cluster Analysis of Daily Time-Use Patterns of Elder Caregivers.” Journal of Population Ageing. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s12062-020-09313-3.

- Lei, X., J. Strauss, M. Tian, and Y. Zhao. 2015. “Living Arrangements of the Elderly in China: Evidence from the CHARLS National Baseline.” China Economic Journal 8 (3):191–214. doi:10.1080/17538963.2015.1102473.

- Leung, J. C. B. 1997. “Family Support for the Elderly in China: Issues and challenges.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 9 (3):87–101. doi:10.1300/J031v09n03_05.

- Li, H., and M. B. Tracy. 1999. “Family Support, Financial Needs, and Health Care Needs of Rural Elderly in China: A Field Study.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 14 (4):357–371. doi:10.1023/A:1006607707655.

- Li, Y. 2017. “The Effects of Formal and Informal Child Care on the Mother’s Labor Supply—Evidence from Urban China.” China Economic Review 44:227–240. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2017.04.011.

- Lilly, M. B., A. Laporte, and P. C. Coyte. 2010. “Do They Care Too Much to Work? The Influence of Caregiving Intensity on the Labour Force Participation of Unpaid Caregivers in Canada.” Journal of Health Economics 29 (6):895–903. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.08.007.

- Litwak, E. 1960. “Geographic Mobility and Extended Family Cohesion.” American Sociological Review 25:385–394. doi:10.2307/2092085.

- Logan, J. R., F. Bian, and Y. Bian. 1998. “Tradition and Change in the Urban Chinese Family: The Case of Living Arrangements.” Social Forces 76 (3):851–882. doi:10.2307/3005696.

- Logan, J. R., and G. D. Spitze. 1995. “Self-Interest and Altruism in Intergenerational Relations.” Demography 32 (3):353–364. doi:10.2307/2061685.

- Lumsdaine, R. L., and S. J. C. Vermeer. 2015. “Retirement Timing of Women and the Role of Care Responsibilities for Grandchildren.” Demography 52 (2):433–454. doi:10.1007/s13524-015-0382-5.

- Ma, S., and F. Wen. 2016. “Who Coresides with Parents? An Analysis Based on Sibling Comparative Advantage.” Demography 53 (3):623–647. doi:10.1007/s13524-016-0468-8.

- Meng, Q., D. Yin, A. Mills, and K. Abbasi. 2019. “China’s Encouraging Commitment to Health.” BMJ 365: l4178.

- Naldini, M., E. Pavolini, and C. Solera. 2016. “Female Employment and Elderly Care: The Role of Care Policies and Culture in 21 European Countries.” Work, Employment & Society 30 (4):607–630. doi:10.1177/0950017015625602.

- Ogawa, N., and J. F. Ermisch. 1996. “Family Structure, Home Time Demands, and the Employment Patterns of Japanese Married Women.” Journal of Labor Economics 14 (4):677–702. doi:10.1086/209827.

- Pilkauskas, N. V., and C. Cross. 2018. “Beyond the Nuclear Family: Trends in Children Living in Shared Households.” Demography 55 (6):2283–2297. doi:10.1007/s13524-018-0719-y.

- Raymo, J. M., H. Park, M. Iwasawa, and Y. Zhou. 2014. “Single Motherhood, Living Arrangements, and Time with Children in Japan.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 76 (4):843–861. doi:10.1111/jomf.12126.

- Roberts, R. E. L., L. N. Richards, and V. Bengtson. 1991. “Intergenerational Solidarity in Families.” Marriage & Family Review 16 (1–2):11–46. doi:10.1300/J002v16n01_02.

- Rossi, A. S., and P. P. H. Rossi. 1990. Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations across the Life Course. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Shen, K., W. Feng, and Y. Cai. 2018. “A Benevolent State against an Unjust Society? Inequalities in Public Transfers in China.” Chinese Sociological Review 50 (2):137–162. doi:10.1080/21620555.2017.1410432.

- Shen, K., P. Yan, and Y. Zeng. 2016. “Coresidence with Elderly Parents and Female Labor Supply in China.” Demographic Research 35 (23):645–670. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2016.35.23.

- Sheppard, P., and R. Sear. 2016. “Do Grandparents Compete with or Support Their Grandchildren? In Guatemala, Paternal Grandmothers May Compete, and Maternal Grandmothers May Cooperate.” Royal Society Open Science 3 (4):160069. doi:10.1098/rsos.160069.

- Silverstein, M., S. J. Conroy, H. Wang, R. Giarrusso, and V. L. Bengtson. 2002. “Reciprocity in Parent-Child Relations Over the Adult Life Course.” The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 57 (1):S3–S13. doi:10.1093/geronb/57.1.s3.

- Silverstein, M., D. Gans, and F. M. Yang. 2006. “Intergenerational Support to Aging Parents: The Role of Norms and Needs.” Journal of Family Issues 27 (8):1068–1084. doi:10.1177/0192513X06288120.

- Smits, A., R. I. Van Gaalen, and C. H. Mulder. 2010. “Parent–Child Coresidence: Who Moves in with Whom and for Whose Needs?” Journal of Marriage and Family 72 (4):1022–1033. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00746.x.

- Stewart, J. 2013. “Tobit or Not Tobit?” Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 38 (3):263–290. doi:10.3233/JEM-130376.

- Strassmann, B. I., and W. M. Garrard. 2011. “Alternatives to the Grandmother Hypothesis: A Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Grandparental and Grandchild Survival in Patrilineal Populations.” Human Nature 22 (1–2):201–222. doi:10.1007/s12110-011-9114-8.

- Ta, N., Z. Liu, and Y. Chai. 2019. “Help Whom and Help What? Intergenerational co-Residence and the Gender Differences in Time Use among Dual-Earner Households in Beijing, China.” Urban Studies 56 (10):2058–2074. doi:10.1177/0042098018787153.

- Tan, X., L. Ruppanner, and M. Wang. 2021. “Gendered Housework under China’s Privatization: The Evolving Role of Parents.” Chinese Sociological Review. doi:10.1080/21620555.2021.1944081.

- Tian, F. F., and D. S. Davis. 2019. “Reinstating the Family: Intergenerational Influence on Assortative Mating in China.” Chinese Sociological Review 51 (4):337–364. doi:10.1080/21620555.2019.1632701.

- United Nations, Population Division. 2017. Living Arrangements of Older Persons: A Report on an Expanded International Dataset. New York, NY: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

- Van Houtven, C. H., N. B. Coe, and M. M. Skira. 2013. “The Effect of Informal Care on Work and Wages.” Journal of Health Economics 32 (1):240–252. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.006.

- West, S. A., I. Pen, and A. S. Griffin. 2002. “Cooperation and Competition between Relatives.” Science 296 (5565):72–75. doi:10.1126/science.1065507.

- Whyte, M. K. 2004. “Filial Obligations in Chinese Families: Paradoxes of Modernization.” In Filial Piety: Practice and Discourse in Contemporary East Asia, edited by C. Ikels. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Xu, Q. 2021. “Division of Domestic Labor and Fertility Behaviors in China: The Impact of Extended Family Traditions on Gender Equity Theory.” China Population and Development Studies 5 (1):41–60. doi:10.1007/s42379-021-00082-w.

- Yang, C., H. Fu, and L. Li. 2016. “The Effect of Family Structure on Female Labor Participation – Empirical Analysis Based on the 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study.” Asian Social Work and Policy Review 10 (1):21–33. doi:10.1111/aswp.12072.

- Yin, T. 2010. “Parent–Child co-Residence and Bequest Motives in China.” China Economic Review 21 (4):521–531. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2010.05.003.

- Yu, J., and Y. Xie. 2018. “Motherhood Penalties and Living Arrangements in China.” Demographic Research 80 (5):1067–1086. doi:10.1111/jomf.12496.

- Zellner, A. 1962. “An Efficient Method of Estimating Seemingly Unrelated Regressions and Tests for Aggregation Bias.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 57 (298):348–368. doi:10.1080/01621459.1962.10480664.

- Zhan, H. J. 2005. “Aging, Health Care, and Elder Care: Perpetuation of Gender Inequalities in China.” Health Care for Women International 26 (8):693–712. doi:10.1080/07399330500177196.

- Zhan, H. J., and J. V. M. Rhonda. 2003. “Gender and Elder Care in China: The Influence of Filial Piety and Structural Constraints.” Gender & Society 17 (2):209–229. doi:10.1177/0891243202250734.

- Zhang, Q. F. 2004. “Economic Transition and New Patterns of Parent-Adult Child Coresidence in Urban China.” Journal of Marriage and Family 66 (5):1231–1245.

- Zhang, Y, and F. W. Goza. 2006. “Who Will Care for the Elderly in China?: A Review of the Problems Caused by China’s One-Child Policy and Their Potential Solutions.” Journal of Aging Studies 20 (2):151–164. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2005.07.002.

- Zhang, Z., D. Gu, and Y. Luo. 2014. “Coresidence with Elderly Parents in Contemporary China: The Role of Filial Piety, Reciprocity, Socioeconomic Resources, and Parental Needs.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 29 (3):259–276. doi:10.1007/s10823-014-9239-4.

- Zhao, M., and E. Hannum. 2019. “Stark Choices: Work-Family Trade-offs among Migrant Women and Men in Urban China.” Chinese Sociological Review 51 (4):365–396. doi:10.1080/21620555.2019.1635879.

Appendix

Table A1. Comparing married individuals in CTUR2008 and CGSS2008 (both weighted).

Table A2. Logistic regressions predicting the odds of labor force participation, urban sample.

Table A3. Correlation matrix of the residuals.