Abstract

Research on migration is shifting from comparisons between migrants and non-migrants in destination countries to a multi-sited origin-destination perspective, which allows us to address the issue of migrant selectivity. Selectivity implies that migration results from a systematic bias according to which emigrants differ from non-migrants in origin. The literature on selectivity has overlooked educational migrants, an important contributor to the flow of highly skilled international migration. We investigate whether international students in tertiary education replicate the pattern of positive selection that is systematically found among the general migrant population. Our paper compares leavers and stayers using social background and selected individuality traits to study this phenomenon. Using the first large-scale representative survey of Chinese students enrolled in tertiary education in China, Germany, and the UK, we provide two critical findings. Firstly, we find a pattern of hyper-selection by social background among Chinese students abroad compared with stayers at home, although international education is a more democratic phenomenon than is generally believed. Secondly, we find that selection in terms of “unobservable” individuality traits is rather modest.

Introduction

Between 2000 and 2019, the stock of internationally mobile students increased almost 165% reaching global figures far beyond 5 million (UNESCO 2021)Footnote1. The status of world regions as sending and receiving contexts is unbalanced. According to pre-pandemic figures, one out of every two educational migrants is based in one of only six countries: the US, the UK, Australia, France, Germany, and the Russian Federation. As for their origins, Asia is the main sending region and China is the largest single source country—the number of Chinese studying abroad in 2020 was around 993,367—followed, at some distance, by India with 375,055 students. The massive contribution of Asia to the global flow of educational migrants is already considered a distinct regional specificity (IOM Citation2018, 59).

The asymmetries notwithstanding, educational migration is increasingly part of international and national agendas. Governments regard educational migration as strategically relevant for economic and demographic reasons. International organizations designate international students as part of the “much desired” skilled migrants due to their projected impact on economic growth and productivity (Kerr et al. Citation2016). Despite these developments, much academic research stubbornly treats international student mobility as a separate research field from migration in which mainstream theories on cross-border mobility and integration are scarcely applied (but see De Haas, Natter, and Vezzoli 2016; Findlay Citation2016; Hawthorne Citation2008). While some research considers macro-level push and pull models as driving factors involved in educational migratory flows, a vast literature focuses on capital accumulation and social reproduction functions of international education (IE) and interpersonal ties and specialized infrastructures that facilitate it (see Lipura and Collins Citation2020 for a review). International students and their experiences are rarely discussed in relation to those of other highly educated migrants and longstanding migration theories and their related empirical regularities.

In this paper, we seek to bring together research on international student mobility with current theoretical and empirical debates from migration scholarship to address one such regularity: migrant selectivity. To do so, we use the Bright Futures Survey (Citation2021). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first-ever large-scale multi-sited representative survey of students in tertiary education, allowing origin China-destination (Germany and the UK) comparisons. This unique empirical tool enables us to document whether educational migrants are a selected population relative to their comparable peers in origin who did not cross borders to pursue education and, if so, in which crucial aspects. More broadly, it helps us gain insights into the selection among highly skilled migrants.

Migration and educational migration as a selection bias

The idea that migrants are a non-representative sample of their co-nationals in origin countries is not new (Borjas Citation1987; Chiswick Citation1978; Feliciano Citation2005; Lee Citation1966; Ravenstein Citation1885) but has been gaining renewed momentum in research (Feliciano Citation2020). According to this idea, migrants are supposed to be a selected group that systematically differs from non-migrants in crucial aspects that, under certain conditions, account for their long-term socioeconomic integration. Contrary to conventional wisdom, migrants rarely come from the most disadvantaged segments of the population in their countries of origin. Those who participate in international migration are less likely to have more vulnerable social profiles and tend to be among the most educated (Dao et al. Citation2016; Van Dalen and Henkens Citation2007). This relative advantage of migrants by social background is generally signaled as a positive selection in terms of observable characteristics (Belot and Hatton Citation2012; Portes and Rumbaut Citation2006), which commonly refer to background variables such as class of origin or educational attainment. Hyper-selection has been documented in absolute and relative terms compared with the average educational profile of non-migrants in the origin countries (Chiquiar and Hanson Citation2002; Feliciano and Lanuza Citation2017; Ichou Citation2014). Scholars have also commented on whether migrants are selected in terms of other factors, such as certain individuality traits, that are rarely measured in mainstream surveys. These traits are generally labeled in the literature as unobservable, or as Feliciano (Citation2020, 253) puts it “difficult-to-measure characteristics”. This branch of the literature shares the analytical approach, design and methods used in research on migration as selection bias but applies this logic to a plethora of dependent variables. Unobservable often overlaps with ambition, motivation, work ethic, inclination to take risks or resilience. It has been suggested that migrants tend to be more optimistic (Cebolla-Boado and Soysal Citation2018), agentic (Soysal and Cebolla-Boado Citation2020), ambitious (Portes and Rumbaut Citation2006), motivated (Frieze et al. Citation2004), secure and less dismissive (Polek, Van Oudenhoven, and Ten Berge Citation2011), and, with some exceptions, achievement-oriented and willing to take risks (Polavieja, Fernández-Reino, and Ramos Citation2018).

Documenting whether migration responds to observable or unobservable selection biases is crucial for grasping the drivers of migration and fully understanding how migrants integrate in their destinations. Overlooking migrants’ possible systematic differences from their co-nationals who did not move prevents us from isolating the effect of the migration experience itself on integration outcomes. Yet, as several authors have pointed out, selectivity is a commonly ignored confounder in research on integration policies and studies analyzing integration outcomes including earnings and earning trajectories (Hamilton Citation2014), educational attainment (Lee and Zhou Citation2015; Van de Werfhorst and Heath Citation2019), and health (Ichou and Wallace Citation2019; Riosmena, Kuhn, and Jochem Citation2017). Furthermore, understanding selection also helps explain the so-called paradoxes of immigrant integration, such as the aspirations-achievement paradox (Feliciano and Lanuza Citation2017) or the healthy immigrant effect (Kennedy et al. Citation2015).

Part of the reason why selection is not adequately addressed in migration research is the lack of appropriate data. The strongest test of selectivity requires longitudinal data to assess emigrants’ attributes prior to migration and comparisons with native-borns in origin and destination (Garip Citation2016; Guveli et al. Citation2017; Massey and Zenteno Citation2000; Mussino, Tervola, and Duvander Citation2019). Building on such comparisons, our paper presents two novel contributions. On the one hand, it combines data from the origin with samples across two European destinations, thus increasing the robustness of our results. On the other hand, while most research on selection refers to the general migrant population, ours provides evidence on educational migrants who, together with other highly educated migrants, are poorly represented groups in the literature on selectivity (Parey et al. Citation2017). Note that the available multi-sited surveys providing data in origin and destination do not provide sufficiently large sub-samples of the highly skilled to be able to conduct multivariate research, a difficulty that is even harder to overcome if the interest is in educational migrants.

Selection among educational migrants

While no previous research has specifically theorized the selection of educational migrants, several arguments in the literature about migration, higher education, and IE invite us to think differently about it.

The most straightforward implications are regarding selectivity based on observable background variables. Mainstream theories of social stratification predict little selection among international students by social background since dropping out of school and transitioning into non-compulsory education is already a non-random behavior (Mare Citation1980). Those who reach tertiary stages of educational careers are already a population selected by cognitive skills and, ultimately, social background (Boudon Citation1974). This provides grounds to suspect that the family backgrounds of international students are like that of their peers in origin enrolled in higher education. However, the expectation of social background homogeneity is contradicted by scholars in the field of IE, who draw on Bourdieusian conceptions of education as an investment in symbolic capital that produces distinctiveness (Bilecen and Van Mol Citation2017). From this perspective, IE is essentially a form of elite reproduction based on parental choice and social class strategies that attempt to guarantee social advantage over the life-course (Brooks, Fuller, and Waters Citation2012; Waters Citation2008). Accordingly, the motivation for studying abroad is often depicted as a means to building human and cultural capital by attending “world-class” education (Findlay et al. Citation2012) or realizing broader mobility plans beyond education (Bilecen Citation2014). In the search for increasing social opportunities, advantaged families may also seek to support their offspring to gain traits that could be considered valuable assets in the global knowledge economy, such as global awareness, intercultural competencies, and new experiences (Chao et al. Citation2017; Wintre et al. Citation2015). As such, the view that connects IE with social reproduction implies significant selectivity by those from the highest social backgrounds.

Little research has focused on the extent to which educational migrants are selected on hard-to-measure individuality traits. The highly educated tend to be exposed to standardized conceptions of the individual as agentic persons supplied by transnationalized systems of higher education (Lerch et al. Citation2017, Citation2022; Soysal Citation2015). This suggests that certain individuality traits could be rather homogeneous across countries and relevant social groups (Soysal and Cebolla-Boado Citation2020), indicating little hyper-selection among migrants.

Our research focuses on migration from China to two European destinations: Germany and the UK. These two countries score as the leading destination for Chinese international students in Europe. On average, Chinese migrants to Europe appears to be less qualified than those heading the US (Echeverria-Estrada and Batalova Citation2020), where they are clearly more educated than other migrants in that country (Rosenbloom and Batalova Citation2023). Within Europe, highly skilled Chinese migrants are 26% in the Netherlands, 22% in France, and 19% in the UK, clearly outperforming other large European countries like Germany, where only 6% entered through the Blue Card program (Plewa Citation2020). Despite its poor ability to attract the most skilled Chinese economic migrants, Germany ranks second, only after the UK, in the continent for its stock of international students coming from China (Plewa Citation2020, 33–37).

Different arguments in the literature on IE allow us to speculate about cross-country heterogeneity in the selection of educational migrants. Beyond the well-known effect of social ties and previous connections (Nyaupane, Paris, and Teye Citation2011), the prestige of education systems and the presence of highly ranked universities according to international classifications could favor hyper-selection. The increasing dominance of world rankings in higher education plays a significant role in signaling “reputation” and “quality” in a globally imagined and expanding field (Soysal, Baltaru, and Cebolla-Boado Citation2022). This might be particularly important for Chinese international students, given that the massive demand for tertiary education in China (Jingming Citation2007) makes it difficult to enroll in the most prestigious institutions locally (Yan Citation2013), which may eventually push students, possibly the most advantaged ones who can afford high fees, to engage in IE. Thus, fees and more generally speaking the cost of educational migration to countries where the cost of tertiary education is high (such as the UK) are one of the contextual limitations for the generalization of high aspirations to materialize (Marzi Citation2016), favoring hyper-selection.

The following table summarizes () the different arguments emerging from our review and systematizes them according to their expected impact on observable and unobservable characteristics. The first two hypotheses present contradicting predictions regarding hyper-selection by social background. H1 is based on the social stratification of educational attainment and suggests little selection beyond compulsory education. In contrast, regarding the dominant Bourdieusian view of IE as a means of elite reproduction, H2 predicts strong selection by social background. Our third hypothesis, H3, expects little to no selection on individual traits because of the transnational standardization of higher education institutions, which shapes the cultural construction of personhood.

Table 1. Summary of hypotheses.

Finally, H4 speculates about differences in selection across countries of destination. We hypothesize that the UK might attract more selected international students by social background for two reasons: Firstly, the longstanding prestige of some of its universities and their systematic representation in international rankings might favor the UK as an expected destination for the most advantaged students seeking to signal the “value” of their education. Secondly, the high cost of fees in British higher education makes the UK a somewhat unrealistic option for students from less advantaged family backgrounds.

Materials and methods

Data

The Bright Futures survey is a representative online survey of Chinese students enrolled in tertiary education in China, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The data were collected in 2017 and 2018 in all countries using equivalent questionnaires cross-translated into Mandarin Chinese and German. The sample was constructed using two different approaches for Europe and China (a full description of the technical details is provided in Bright Futures Survey Citation2021). Background research prior to the construction of the samples showed that two factors, the ranking of the university and the number of Chinese students enrolled in the university the previous year, significantly explained the sorting of Chinese students across the higher education institutions in the destination (Cebolla-Boado and Soysal Citation2018). Accordingly, the survey adopted a two-stage sampling logic in the UK and, for comparability, also in Germany. Universities were first stratified into groups according to ranking and the number of Chinese students enrolled in each institution to ensure that students from different types of universities were proportionally represented. Within each university selected, random samples of undergraduate and master students of Chinese and native-born German and British backgrounds were obtained. In China, a similar strategy was followed. Universities were first stratified based on region (provinces in the north, south, and east of the country) and prestige. Students were then randomly selected within the sampled 22 universities distributed across the provinces to participate in the survey. In each country, the respondents were individually invited to participate in the online survey, and compensation for completed questionnaires was provided.

describes the sample size for each analytic group in this paper: international Chinese students in tertiary education in China, Germany, and the UK. The table presents the analytical sample of respondents to the survey and the sample (n = 4,562 cases) used in the analysis. Twenty percent of the initial sample was lost due to missing data in our variables of interest.

Table 2. Total and analytic samples of Chinese students.

Variables

Our hypotheses necessitate that we assess whether there are differences between migrant and non-migrant students as well as across destination countries regarding several observable and unobservable characteristics which work as our dependent variables in the analyses. Regarding observable characteristics, we picked two variables commonly used to represent family social background: the level of parental education (grouped into three categories: primary or less; secondary; and tertiary education) and the father’s occupation based on three categories (“professional/technical occupations and higher administrators”, “clerical, service, and sales occupations” and “unskilled workers and farmers”).

To boost the robustness of our analysis, we scrutinize the selection on unobservable characteristics along three different dimensions, which are embedded in educational and cultural narratives as standard qualities of an agentic self in the context of knowledge societies (Meyer and Jepperson Citation2000; Soysal Citation2015). Traits such as belief in one’s capabilities, belief in sustained effort as the basis of success, and being ambitious and independent are not only promoted by education but also shape individuals’ own projections and strategies of self (Frye Citation2012). The Bright Futures Survey includes different sets of questions we use to operationalize these three dimensions.

First, we use an index of “self-efficacy”, defined broadly as one’s belief in their own ability to shape relevant events in their life (Bandura Citation1997), which brings together four variables: whether the student thinks that someone who “finds a way to get what they want", "sticks to their aims", "deals efficiently with the unexpected," and "thinks of a solution to problems" is similar or not to them (not at all like me, somewhat unlike me, neither like nor unlike me, somewhat like me, very much like me). These variables were merged using a factorial analysis in which a single dimension, “someone who finds a way to get what s/he wants”, was retained (results are available upon request).

Secondly, we use a variable measuring the extent to which respondents identify the source of success as rooted in their own effort. Referred to as (internal) “locus of control” in the psychological literature (Lefcourt Citation1991), it addresses how strongly individuals believe they have control over their life outcomes. In education, it is discussed in the context of how students perceive the causes of their success or failure, or more generally, as meritocratic beliefs. Specifically, our questionnaires asked students about their beliefs in whether their own talent, hard work, and self-confidence matter for success. Students replied choosing whether each of these factors is “not at all important”, “slightly”, “moderately”, “very,” or “extremely important”. Similarly to our strategy with the self-efficacy variable, a factor analysis was conducted collapsing the last three variables into a synthetic index of internal locus of control (results available upon request).

Thirdly, we use an “agentic personality” index defining proactive, independent, and goal-oriented individuals (Meyer and Jepperson, Citation2000). Bright Futures questionnaires collected views from students regarding whether they would describe themselves as someone creative, makes their own decisions, looks for adventures and risks, and are success oriented. Answers were registered using a five-point scale. As before, we merged all four variables into a unique factor (results available upon request).

describes all the variables in our analysis.

Table 3. Summary statistics: overall sample.

Methods

Since our data is representative of both stayers in China and Chinese educational migrants, the contrast of H1 and H2 basically requires reporting the average differences between these groups by observable characteristics across migrant status and destination countries since the parental social background is not causally determined by engaging in IE. However, this simple approach is inappropriate for testing our hypotheses on the unobservable dependent variables, given that migration might, at least partially, determine the views that individuals have of themselvesFootnote2. To render any systematic difference between migrant and non-migrant students both in origin and destination unconditional, we control for both social background and several socio-demographic factors (gender, age, past hukou, i.e., the family registration status while in secondary school in China) and prior school results (self-reported percentile of performance in high school).

To empirically address the overdetermination of migrant status by factors that can simultaneously impact on individuality scores, we estimated treatment effect models, which produce quasi-experimental inferences using observational data. Treatment effects allow the modeling of systematic differences in the likelihood of being migrants or stayers, together with the effect of other covariates on the dependent variable. Since educational migration from China is certainly not a random reality, our outcomes of interest may not be independent of treatment. To avoid the implications of this non-randomness in treatment assignment, the average treatment effect (ATE) is estimated after conditioning on covariates that crucially determine treatment status.

In our models, treatment (migrant) status is predicted as a function of parental education and hukou in secondary school (to discriminate between rural and urban areas of origin). Since we expected that exposure to the transnational environment might increase the likelihood of outmigration (Soysal and Cebolla-Boado Citation2020), we also created a synthetic index to capture inequalities between Chinese provinces in which students lived before migration. This index is built from regional data obtained from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics on the number of patents by province population; the number of foreign visitors to the province by province population; the number of Internet domains in the province by province population; foreign investment by GDP per capita and the total value of imports and exports of foreign-funded enterprises (1,000 US dollars) by GDP per capita. These indicators were pulled together into a single meaningful factor representing the level of “exposure to the transnational environment”.

Results

Observable characteristics

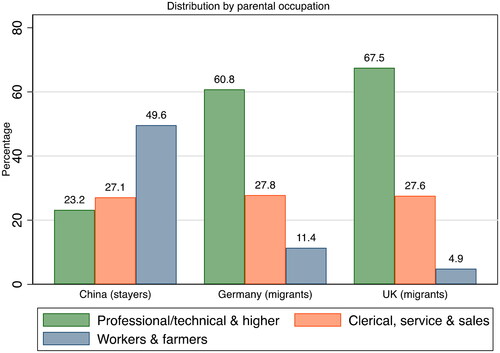

Educational migrants from China are positively selected on social background. summarizes the distribution of the occupation of Chinese students’ fathers across our four involved countries. In the UK, Chinese students from the most advantaged backgrounds (i.e., those whose fathers are professionals, technical personnel, or higher administrators) in our threefold classification represent 67.5%. In comparison, this figure in Germany is around 60.8%. The percentage of students with fathers from the intermediate professional categories (i.e., clerical, service, and sales) is rather balanced across countries. By contrast, in China, the students predominantly come from the lowest social backgrounds, 49.6%, compared to 10.5% in Germany and below 5% in the UK. In China, the students whose fathers belong to high-status occupations are only 23.2%.

Figure 1. Selection on observables: distribution of parental occupation across sample. Table info: Overall Pearson Chi2 = 0.00***; Cramér’s V = 0.34. Partial Pearson Chi2: China-Ger: 429.17***; China-UK: 951.66*** Ger-UK: 28.20***.

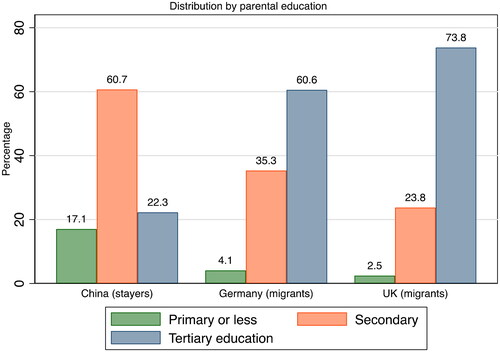

We reach a similar conclusion if we use the highest level of parental education to measure social background (). Chinese students abroad whose parents only have primary education or less are significantly under-represented (systematically below 5% across the three destination countries) compared to those in China (17.1 percent). More revealing is the comparison between students whose parents have secondary and tertiary education. Among Chinese students in China, 60.7% of their parents have secondary education, while this figure shrinks to 23.8% in the UK, and 35.2% in Germany. The opposite happens however if we look at the prevalence of tertiary education among parents. While in China only 22.3% of students have parents with university degrees, in the UK a striking 73.8% do, followed by 60.4% in Germany.

Figure 2. Selection on observables: distribution of parental education across samples. Overall Pearson Chi2 = 0.00***; Cramér’s V = 0.34. Partial Pearson Chi2: China-Ger: 424.35***; China-UK: 1100.00***; Ger-UK: 38.16***.

In other words, the selection of educational migrants by observable characteristics corresponds less to our first hypothesis (H1), which predicts similar social backgrounds across students beyond compulsory education and is more in line with the elite-reproduction understanding of IE (H2). Yet, our evidence also suggests that IE, in the case of China, is a more democratic phenomenon than generally expected by such an understanding. In the UK, where there is a high positive selection regarding social backgrounds, more than one out of every three Chinese international students are not from the most advantaged occupational backgrounds, and one out of four are children of parents without university degrees. While there is indeed a social background slope in access to IE, the constant of the regression suggests that it is also a viable option for many less advantaged Chinese students. Two facts support this rather unexpected result. First, the massive economic expansion China experienced over the last two decades, combined with the tight demographic control imposed until recently by the one-child policy, ultimately allowed families to pool resources accumulated across generations to invest in education (Xiao Citation2016). Second, IE is increasingly promoted by various sending and receiving country policies and funding, contributing to an overall normalization of the experienceFootnote3. More broadly, however, the finding may also reflect the heightened aspirations among contemporary students on a worldwide scale who imagine themselves easily moving and learning across national borders and higher education systems and being able to carry their knowledge and degrees with them wherever they may go (notwithstanding parental backgrounds and much of the restrictively imposed visa and immigration regulations).

Our findings show that the UK attracts the most hyper-selected flow of Chinese international students by social background, confirming the fourth hypothesis (H4), likely because of higher fees in the UK than in alternative destinations, as well as the international reputation of the British higher education, buttressed by the widespread endorsement of world rankings.

Individuality traits

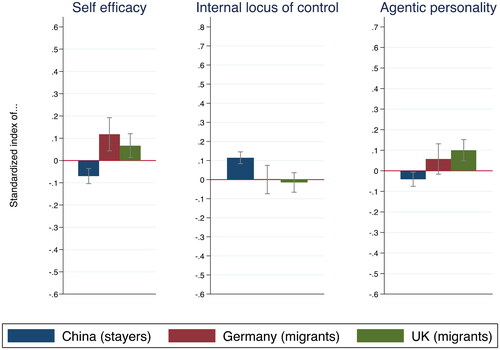

The results are radically different when focusing on unobservable characteristics; our evidence suggests much weaker evidence of migrant hyper-selection across our countries of analysis. reports descriptive (unconditional) averages of our indexes of self-efficacy (panel on the left), internal locus of control (center), and agentic personality (right) prior to the estimation of treatment effects. Since all three indexes are standardized, the results should be interpreted in standard deviations. The scale of the vertical axes in the plot corresponds to interquartile ranges.

Figure 3. Selection on unobservables: average self-efficacy, internal locus of control and agentic personality across samples.

Several observations stand out from this basic description of cross-country differences. Firstly, the differences between China and our destination countries are minor, with most differences being insignificant. Secondly, these unconditional results mean we can discount the idea of a clear-cut pattern of hyper-selection. Only in the case of self-efficacy do stayers in China score lower than educational migrants across both destinations, a significant but small effect. Differences in internal locus of control are also negligible and, if anything, suggest higher values among stayers in China than among migrants abroad. Finally, in the plot corresponding to agentic personality, differences between China and Germany are insignificant, with a slightly significant difference between China and the UK being the only notable effect.

While this first set of results tentatively confirms the expectation of our H3, namely that the current transnationalized nature of tertiary education grounds visible similarities among students in different countries, a sound test of this hypothesis requires a more demanding empirical approach. As suggested, we use treatment models to tackle any systematic difference in our dependent variable that could result from a non-random distribution of crucial variables by treatment status. presents the results of our treatment effects estimations. The results are presented in three blocks. The first part of the table shows the average treatment effect isolating the impact of being a Chinese educational migrant in Germany and the UK as opposed to being a stayer in China (P0 means). The ATE for our destinations indicates no systematic differences in migration status in self-efficacy, internal locus of control, or agentic personality after controlling for our covariates and modeling non-random selection into migration. None of the country estimates are significantly different from stayers in China, with the only exception which is not aligned with the prediction of migrants being positively selected: being a Chinese educational migrant in the UK is associated with lower levels of internal locus of control score than it is for Chinese students elsewhere. Thus, if anything, this points to a pattern of negative selection. Uniformity across cases suggests confirmation of H3, pointing at isomorphism in terms of how unobservable characteristics are distributed across students in different locations due to the transnationalization of tertiary education globally.

Table 4. IPWRA treatment effects model.

The second part of the table shows the regression adjustment to our treatment estimations. ATEs are controlled for gender, age, prior school performance, rural vs urban hukou registry while in secondary education, and parental educational background.

Finally, the third part of our table shows the logistic equations that model selection into migration (i.e. selection into treatment status). To model potential biases in how our sample is distributed among migrants and stayers we used parental education and a synthetic index of exposure to the transnational environment in the Chinese province in which students completed secondary education.

Our models confirm no composition effects behind the remarkable uniformity in individuality traits. Taking into consideration the selected controls and selection into migration status, the average scores for Chinese in China and Chinese in European countries are not statistically distinguishable, though with unimportant exceptions.

Our selection equations show that our predictors of treatment status contribute intrinsic biases into migration. Across countries of destination, those whose parents are more educated are more likely to engage in IE; students from provinces that are more exposed to transnational environments are similarly more likely to engage in IE, as are those coming from urban origins.

In summary, while our overall findings show evidence of selection in terms of observed characteristics, they do not lend full support for the argument that IE should be conceptualized as a mere strategy of elite reproduction. As we have seen, Chinese students from rather diverse social backgrounds participate in IE. Furthermore, selection on the bases of unobservable characteristics is far from evident. The distribution of students on these characteristics is similar across countries. This supports recent research which suggests that the transnationalization of higher education produces standardized conceptions of the self, shared by students across countries and migrant status (Soysal and Cebolla-Boado Citation2020).

Robustness checks

Our results are stable when controlling for a large list of aspects, such as household structure and alternative controls for family background and student characteristics. Our results are also robust if separately estimated by gender.

Selection on parental education relative to the average level of education in the province where the student did their secondary education (relative education) follows a similar pattern to the one described for parental education in absolute terms.

Finally, we have also modeled the variation associated with having opted for IE driven by social networks that can disseminate information and reduce travel costs. Researchers into IE have often highlighted the important role played by social networks and agents as facilitators of educational mobility (Collins Citation2008). We have not found any association between these arguments and selection patterns into IE or selection into destinations.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our paper is the first to use representative and multi-sited micro-level data to document patterns of migrant selectivity among international students, a much-understudied topic despite the growing and dynamic scholarships on educational migration and migrant selectivity. Our evidence shows that there are grounds for recognizing hyper-selection based on social background but clearly less supporting evidence for selection by individuality traits.

Students from the most advantaged social backgrounds are, as suggested by a large part of the literature, over-represented in the flows of educational migrants. While this is in line with the predictions of the elite reproduction hypothesis, we argue that hyper-selection based on the family background does not necessarily assume strategic transmission of advantage. It may simply reflect the unavoidable gap between aspirations for social mobility and behavior, and ultimately the unequal ability to afford the cost of mobility for education (e.g. travel expenses, cost of living abroad, and tuition fees).

There are two qualifiers to the mainstream argument linking IE and elite reproduction. On the one hand, there are important country differences. Educational migrants to the UK are clearly more selected than those heading elsewhere in Europe. Since learning English as a foreign language is the most prevalent choice globally, including in China, one could expect the UK to attract a more diverse flow of students by family background. The same could be said about the perceived prestige of British higher education, which should make British universities attractive to all student profiles. We interpret the stronger selection of Chinese students in the UK because of its fee-based structure, which imposes the highest cost to international studentsFootnote4 and is radically different from the German model with low fees for all students in higher education.

On the other hand, while hyper-selection by social background is confirmed, it should be noted that our evidence shows IE to be a much more heterogeneous flow of migrants by social background than scholars inspired by Bourdieusian arguments might imagine. Almost one out of every three Chinese students abroad appear to come from non-privileged backgrounds, suggesting that IE is a more democratic practice than mere descriptions of it as an elite reproductive strategy suppose. It is likely that the one-child policy, which reduced the number of children in China for decades, bolstered this result by allowing families to pool resources inter-generationally to support the single descendant of many households. However, to the extent that governments, including the Chinese one, strategically and explicitly pursue internationalization strategy and educational aspirations are increasingly internationalized (Cebolla-Boado and Soysal Citation2018), we are likely to find that such a result is not unique to Chinese international students.

In terms of the literature on migrant selection on the bases of hard-to-measure or unobservable characteristics, our evidence is clear. Taking into consideration the proper controls and covariates, no pattern of selection could be confirmed using three relevant individuality traits as dependent variables (self-efficacy, internal locus of control, and agentic personality). Using treatment effects, we modeled the average differences between Chinese educational migrants and stayers in China after correcting for the fact that educational migrants generally come from more educated backgrounds, urban settings and provinces that are more exposed to the transnational environment. Again, we found no patterns of hyper-selection. We interpret this homogeneity as being due to the transnationalization of education around the world, which helps diffuse similar conceptions of the self and produces, as we have seen, a significant homogeneity in those individual traits considered crucial in a knowledge society.

In sum, our paper describes, for the first time, patterns of selection among international students, specifically those from China. It documents hyper-selectivity only on observable characteristics, whereas we find homogeneity across migrant status on unobservables among international students. It should be noted that this population is increasingly seen as part of the broader migratory flows of the highly skilled. We suspect that a similar pattern of migrant selectivity applies in the case of other educated migrants.

Future research should see if the patterns of selection described here for Chinese students abroad also apply to other flows of international students. It would be particularly interesting to study if our prediction matches the selection pattern of Chinese in the US, whose system of tertiary education is, at least, as stratified as the British one and requires enormous financial efforts from enrolled students and their families. Future research should also unveil if the same patterns hold for other highly skilled migrants who are likely to display homogenous individuality traits across countries. We consider this paper as an invitation to interested scholars to pursue these lines of thought.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in UK Data Service at https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/854291/, reference number 10.5255/UKDA-SN-853568.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Héctor Cebolla-Boado

Héctor Cebolla-Boado is Senior Scientist at the National Research Council, Institute of Economics, Demography and Geography (Madrid, Spain). He obtained his PhD, from the University of Oxford. He has been an associate professor of Sociology at UNED (Madrid, Spain), and a visiting professor at Pompeu Fabra University (Barcelona, Spain) and the University of Bielefeld (Germany). His research deals with the explanation of ethnic differentials in education and health among migrants and natives, both in countries of origin and destination.

Yasemin Nuhoglu Soysal

Yasemin Nuhoglu Soysal is Research Professor of Global Sociology at WZB Berlin (https://www.wzb.eu/en/persons/yasemin-soysal), Professor of Sociology at Free University Berlin, and leading research member of the SCRIPTS Cluster of Excellence (https://www.scripts-berlin.eu). Her current research focuses on the transnationally standardized script of agentic, meritocratic citizenship and its comparative scope, enactments, and paradoxical outcomes.

Notes

1 https://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow (accessed 21st August 2023).

2 An alternative modeling strategy in our case would be structural equations, a method widely used in research on higher education (Green Citation2016). Despite its obvious advantages for identifying causal relations between observable and latent variables, our paper does not hypothesize the association between observable and unobservable characteristics, a question that we expect to be the focus of further research using Bright Futures data.

3 In the case of China, government funding is mainly reserved for research degrees and doctoral studies (Fedasiuk Citation2020).

4 In addition, our data was drawn at the time of Brexit, with heightened and negative public debate on migration, which may have disincentivized the choice of students with ultimate migration motivations.

References

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

- Belot, Michele V. K., and Timothy J. Hatton. 2012. “Immigrant Selection in the OECD.” The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 114 (4):1105–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2012.01721.x

- Bilecen, Başak. 2014. International Student Mobility and Transnational Friendships. London: Palgrave.

- Bilecen, Başak and Christian Van Mol. 2017. “Introduction: International Academic Mobility and Inequalities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8):1241–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300225

- Borjas, George J. 1987. Self-Selection and the Earnings of Immigrants. Santa Barbara: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w2248.

- Brooks, Rachel, Alison Fuller, and Johanna Lesley Waters. 2012. Changing Spaces of Education: New Perspectives on the Nature of Learning. Oxon: Routledge.

- Boudon, Raymond. 1974. Education, Opportunity, and Social Inequality: Changing Prospects in Western Society. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bright Futures Survey. 2021. Bright Futures Surveys in the UK, Germany, China and Japan. Accessed March, 2022.

- Cebolla-Boado, Hector, and Yasemin Nuhog¯lu Soysal. 2018. “Educational Optimism in China: Migrant Selectivity or Migration Experience?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (13):2107–2126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1417825

- Chao, Chiang N., Niall Hegarty, John Angelidis, and Victor F. Lu. 2017. “Chinese Students’ Motivations for Studying in the United States.” Journal of International Students 7 (2):257–69. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v7i2.380

- Collins, Francis Leo. 2008. “Bridges to Learning: International Student Mobilities, Education Agencies and Inter-Personal Networks.” Global Networks 8 (4):398–417.

- Chiquiar, D., and G. H. Hanson. 2002. International migration, self-selection, and the distribution of wages: Evidence from Mexico and the United States. Mexico: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9242.

- Chiswick, Barry R. 1978. “The Effect of Americanization on the Earnings of Foreign-Born Men.” Journal of Political Economy 86 (5):897–921. https://doi.org/10.1086/260717

- Dao, Thu Hien, Frédéric Docquier, Christopher Robert Parsons, and Giovanni Peri. 2016. Migration and development: Dissecting the anatomy of the mobility transition. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2849757.

- De Haas, Hein, Katharina Natter, and Simona Vezzoli. 2018. “Growing Restrictiveness or Changing Selection? The Nature and Evolution of Migration Policies.” International Migration Review 52 (2):324–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918318781584

- Echeverria-Estrada, Carlos, and Jeanne Batalova. 2020. “Chinese Immigrants in the United States.” Migrationpolicy.Org. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/chinese-immigrants-united-states.

- Fedasiuk, Ryan. 2020. The China Scholarship Council: An Overview. Center for Security and Emerging Technology. Georgetown University. CSET - https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/China-Scholarship-Council-Overview.pdf

- Feliciano, Cynthia. 2005. “Educational Selectivity in US Immigration: How do Immigrants Compare to Those Left behind?” Demography 42 (1):131–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2005.0001

- Feliciano, Cynthia. 2020. “Immigrant Selectivity Effects on Health, Labor Market, and Educational Outcomes.” Annual Review of Sociology 46 (1):315–34. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054639

- Feliciano, Cynthia, and Yader R. Lanuza. 2017. “An Immigrant Paradox? Contextual Attainment and Intergenerational Educational Mobility.” American Sociological Review 82 (1):211–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416684777

- Findlay, Allan. 2016. “The Mobility of Students and the Highly Skilled.” Population Studies 70 (1):137–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2016.1143264

- Findlay, Allan M., Russell King, Fiona M. Smith, Alistair Geddes, and Ronald Skeldon. 2012. “World Class? An Investigation of Globalisation, Difference and International Student Mobility.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 (1):118–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00454.x

- Frieze, Irene H., Bonka S. Boneva, Nataša Šarlija, Jasna Horvat, Anušska Ferligoj, Tina Kogovšek, Jolanta Miluska, Ludmila Popova, Janna Korobanova, Nadejda Sukhareva, et al. 2004. “Psychological Differences in Stayers and Leavers: Emigration Desires in Central and Eastern European University Students.” European Psychologist 9 (1):15–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.9.1.15

- Frye, Margaret. 2012. “Bright Futures in Malawi’s New Dawn: Educational Aspirations as Assertions of Identity.” AJS; American Journal of Sociology 117 (6):1565–1624. https://doi.org/10.1086/664542

- Garip, Filiz. 2016. On the Move: Changing Mechanisms of Mexico-US Migration. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Green, Teegan. 2016. “A Methodological Review of Structural Equation Modelling in Higher Education Research.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (12):2125–2155. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1021670

- Guveli, Ayse, Harry B. G. Ganzeboom, Helen Baykara-Krumme, Lucinda Platt, Şebnem Eroğlu, Niels Spierings, Sait Bayrakdar, Bernhard Nauck, and Efe K. Sozeri. 2017. “2,000 Families: Identifying the Research Potential of an Origins-of-Migration Study.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (14):2558–2576. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1234628

- Hamilton, Tod G. 2014. “Selection, Language Heritage, and the Earnings Trajectories of Black Immigrants in the United States.” Demography 51 (3):975–1002. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0298-5

- Hawthorne, Lesleyanne. 2008. The Growing Global Demand for Students as Skilled Migrants. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

- Ichou, Mathieu. 2014. “Who They Were There: Immigrants’ Educational Selectivity and Their Children’s Educational Attainment.” European Sociological Review 30 (6):750–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu071

- Ichou, Mathieu, and Matthew Wallace. 2019. “The Healthy Immigrant Effect: The Role of Educational Selectivity in the Good Health of Migrants.” Demographic Research 40 (4):61–94. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.40.4

- IOM. 2018. World Migration Report. Geneva: IOM.

- Kennedy, Steven, Michael P. Kidd, James Ted McDonald, and Nicholas Biddle. 2015. “The Healthy Immigrant Effect: Patterns and Evidence from Four Countries.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 16 (2):317–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0340-x

- Kerr, SariPekkala, William Kerr, Caglar Ozden, and Christopher Parsons. 2016. “Global Talent Flows.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (4):83–106.

- Lee, Everett S. 1966. “A Theory of Migration.” Demography 3 (1):47–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060063

- Lee, Jennifer, and Min Zhou. 2015. The Asian American Achievement Paradox. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lerch, Julia C., Patricia Bromley, Francisco O. Ramirez, and John W. Meyer. 2017. “The Rise of Individual Agency in Conceptions of Society: Textbooks Worldwide, 1950–2011.” International Sociology 32 (1):38–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580916675525

- Lerch, Julia C., Patricia Bromley, and John W. Meyer. 2022. “Global Neoliberalism as a Cultural Order and Its Expansive Educational Effects.” International Journal of Sociology 52 (2):97–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2021.2015665

- Lefcourt, Herbert M. 1991. “Locus of Control.” In Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes, edited by J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, and L. S. Wrightsman. New York: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-590241-0.50013-7

- Lipura, Sarah J., and Francis L. Collins. 2020. “Towards an Integrative Understanding of Contemporary Educational Mobilities: A Critical Agenda for International Student Mobilities Research.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 18 (3):343–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2020.1711710

- Jingming, Liu. 2007. “The Expansion of Higher Education and Uneven Access to Opportunities for Participation in it, 1978-2003.” Chinese Education & Society 40 (1):36–59. https://doi.org/10.2753/CED1061-1932400103

- Mare, Robert D. 1980. “Social Background and School Continuation Decisions.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 75 (370):295–305.

- Marzi, Sonja. 2016. “Aspirations and Social Mobility: The Role of Social and Spatial (im)Mobilities in the Development and Achievement of Young People’s Aspirations.” In Movement, Mobilities, and Journeys. Geographies of Children and Young People, edited by C. N. Laoire, A. White and T. Skelton. Singapor: Springer.

- Massey, Douglas S., and René Zenteno. 2000. “A Validation of the Ethnosurvey: The Case of Mexico-U.S. migration.” International Migration Review 34 (3):766–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791830003400305

- Meyer, John W., and Ronald Jepperson. 2000. “The “Actors” of Modern Society: The Cultural Construction of Social Agency.” Sociological Theory 18 (1):100–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00090

- Mussino, Eleonora, Jussi Tervola, and Ann-Zofie Duvander. 2019. “Decomposing the Determinants of Fathers’ Parental Leave Use: evidence from Migration between Finland and Sweden.” Journal of European Social Policy 29 (2):197–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718792129

- Nyaupane, Gyan P., Cody Morris Paris, and Victor Teye. 2011. “Study Abroad Motivations, Destination Selection and Pre-Trip Attitude Formation.” International Journal of Tourism Research 13 (3):205–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.811

- Parey, Matthias, Jens Ruhose, Fabian Waldinger, and Nicolai Netz. 2017. “The Selection of High-Skilled Emigrants.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 99 (5):776–92. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00687

- Plewa, Piotr. 2020. “Chinese Labor Migration to Europe, 2008-16. Implications for China-EU Mobility in the Post-Crisis Context.” International Migration 58 (3):22–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12659

- Polavieja, Javier G., Mariña Fernández-Reino, and María Ramos. 2018. “Are Migrants Selected on Motivational Orientations? Selectivity Patterns Amongst International Migrants in Europe.” ». European Sociological Review 34 (5):570–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy025

- Polek, Elzbieta, Jan Pieter Van Oudenhoven, and Jos M. F. Ten Berge. 2011. “Evidence for a ‘Migrant Personality’: Attachment Styles of Poles in Poland and Polish Immigrants in The Netherlands.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 9 (4):311–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2011.616163

- Portes, Alejandro, and RubenG. Rumbaut. 2006. Immigrant America: A Portrait. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ravenstein, Ernst Georg. 1885. “The Laws of Migration.” Journal of the Statistical Society of London 48 (2):167–235. https://doi.org/10.2307/2979181

- Riosmena, Fernando, Randall Kuhn, and Warren C. Jochem. 2017. “Explaining the Immigrant Health Advantage: Self-Selection and Protection in Health-Related Factors among Five Major National-Origin Immigrant Groups in the United States.” Demography 54 (1):175–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0542-2

- Rosenbloom, Raquel, and Jeanne Batalova. 2023. “Chinese Immigrants in the United States.” Migrationpolicy.Org. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/chinese-immigrants-united-states

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhog¯lu. 2015. “Mapping the Terrain of Transnationalization: Nation, Citizenship, and Region.” In Transnational Trajectories in East Asia: Nation, Citizenship, and Region, edited by Y. Nuhog¯lu Soysal. New York: Routledge.

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhog¯lu, and Hector Cebolla-Boado. 2020. “Observing the Unobservable: Migrant Selectivity and Agentic Individuality among Higher Education Students in China and Europe.” Frontiers in Sociology 5:9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.00009

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhog¯lu, and Hector Cebolla-Boado. 2023. Transnationalization of Educational Aspirations. Evidence from China. Sociological Research Online.

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhog¯lu, Roxana Baltaru, and Hector Cebolla-Boado. 2022. “Meritocracy or Reputation? The Role of Rankings in the Sorting of International Students across Universities.” Globalisation, Societies and Education:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2070131

- Van Dalen, Hendrik P., and Kène Henkens. 2007. “Longing for the Good Life: Understanding Emigration from a High-Income Country.” Population and Development Review 33 (1):37–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00158.x

- Van de Werfhorst, Herman G. and Anthony Heath. 2019. “Selectivity of Migration and the Educational Disadvantages of Second-Generation Immigrants in Ten Host Societies.” European Journal of Population = Revue Europeenne de Demographie 35 (2):347–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9484-2

- Waters, Johanna L. 2008. Education, Migration, and Cultural Capital in the Chinese Diaspora. New York: Cambria Press.

- Wintre, Maxine Gallander, A. R. Kandasamy, Saeid Chavoshi, and Lorna Wright. 2015. “Are International Undergraduate Students Emerging Adults? Motivations for Studying Abroad.” Emerging Adulthood 3 (4):255–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815571665

- Xiao, Suowei. 2016. “Intimate Power: The Intergenerational Cooperation and Conflicts in Childrearing among Urban Families in Contemporary China.” The Journal of Chinese Sociology 3 (1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-016-0037-y

- Yan, Yunxiang. 2013. “The Drive for Success and the Ethics of the Striving Individual.” In Ordinary Ethics in China, edited by C. Stafford. London: Bloomsbury.