Abstract

The focus is on the misalignment between territory and the legal construct encasing the sovereign authority of the state over its territory—territoriality. The aim is to make visible that territory cannot be reduced to either national territory or state territory, and thereby to give the category territory a measure of conceptual autonomy from the nation-state. Beyond an intellectual project, this analysis seeks to enable a conceptual mobilizing of the category territory, here understood as a complex capability with embedded logics of power/empowerment and of claim making, some worthy and some more akin to power-grabs.

Extracto La atención se centra en el desfase entre el territorio y la construcción legal que encierra la autoridad territorial soberana del Estado, es decir, la territorialidad. La finalidad es hacer ver que el territorio no puede reducirse a un territorio nacional o territorio estatal, y de este modo otorgar a la categoría de territorio una medida de autonomía conceptual del estado-nación. Más allá de un proyecto intelectual, con este análisis pretendemos facilitar una movilización práctica del territorio como una capacidad compleja con lógicas de poder/empoderamiento y de reivindicación, algunas valiosas y otras más bien parecen tomas de poder.

摘要 本文聚焦 “领土” 以及 “将国家主权包覆入领土中的法律建构——领土性” 之间的错误结合,旨在揭露 “领土” 不可化约为 “国族的领土” 或是 “国家的领土”,藉此赋予 “领土” 此一范畴在概念上独立于国族国家之外的主体性。除了做为一项知识计画,此一分析更寻求在概念上调动领土的范畴,亦可理解为铭刻着权力/赋权与提出主张的逻辑之复杂能力,其中有的具有适切性、有的则更近似权力攫取。

Résumé L'article porte sur un décalage entre le territoire et la notion juridique qui embrasse les droits souverains de l’État sur son territoire – à savoir, la territorialité. On cherche à montrer que le territoire ne peut être réduit ni à la notion de territoire national, ni à la notion de territoire d’État et, par la suite, à rendre à la catégorie de territoire un brin d'autonomie conceptuelle par rapport à l’État-nation. Au-delà d’être un projet intellectuel, cette analyse cherche à permettre une mobilisation conceptuelle de la notion de territoire, entendue ici comme une compétence complexe dotée des logiques intégrées de pouvoir/responsabilisation et de revendications, dont certaines sont valables et d'autres plutôt des prises de pouvoir.

INTRODUCTION

The effort here is to understand aspects of territory that came to be buried, operationally and formally, with the ascendance of the territorial nation-state. The latter may well have given us one of the most complex and achieved formats for territory, a fact that may have led to the analytic flattening of territory into that single meaning. Some of what I examine here concerns old and long-standing trends, only vaster now or ensconced in a different operational space. And some, I will argue, emerge out of the specific institutional and structural rearrangements of our epoch, often given distinctive forms through the law. I posit two types of major formations, both of which can take on formal and informal instantiations. One is the making of non-national jurisdictions inside the state's territorial jurisdiction itself. The other is the making of new types of bordered spaces that cut across the traditional interstate borders. Thus, while I agree with, and use the scholarship on the impacts of cross-border flows on sovereign state borders, I do so with another project in mind: what this tells us about the category territory itself, rather than about the state's authority over its borders.

Such an inquiry requires a conceptual shift away from the borders of the nation-state as the site of change and of meaning. The overriding of borders is an important focus in the scholarship, including my own, about the weakening of state authority over its territory (e.g. Taylor, Citation1994; Anderson, Citation1996; Sassen, Citation1996; Keohane et al., Citation2000; Berman, Citation2002; Agnew, Citation2005; Miller and Zumbansen, Citation2011; Cutler and Gill, Citation2013). More generally, writing on the state has tended to focus on the earlier battles to gain territory and the ongoing work of securing the sovereign's authority over its territory (see Krasner, Citation1993; Helleiner, Citation1994, Citation1995; Cerny, Citation1997; Weiss, Citation1998; Pauly, Citation2002; for a more analytic approach see Jessop, Citation1999). To exaggerate for the sake of clarity, the focus on the state's authority over its borders has led to a naturalizing of territory as what is encased in national borders. And this, I find, leads to an analytic pacifying or neutralizing of the category territory. In much scholarly writing, territory has largely ceased to work analytically because it has been reduced to a singular meaning—national-state territory.

Critical political geographers, critical political scientists, and critical legal scholars have been among the most important contributors to more analytic versions of territory (see Gottmann, Citation1973; Sack, Citation1986; Agnew, Citation1994, Citation2005; Taylor, Citation1994, Citation1996; Berman, Citation2002; Brenner, Citation2004; Raustiala, Citation2005; Elden, Citation2010; Painter, Citation2010; Kratochwil, Citation2011). This is crucial for avoiding what Agnew (Citation1994, Citation2005) has punctually called ‘the territorial trap’, one evident in much writing about the state and the international system. This has also become an issue in the legal scholarship, for example in Raustiala's critique of what he labels ‘legal spatiality’, namely the notion that ‘The scope and reach of the law is connected to territory, and therefore, spatial location determines the operative legal regime’ (Citation2005, p. 106).

Elden (Citation2010) has one of the most thorough and theorized examinations of the term ‘territory’, which, he notes, is ‘often assumed to be self-evident in meaning, allowing the study of its particular manifestations—territorial disputes, the territory of specific countries, etc.—without theoretical reflection on the “territory” itself’ (Citation2010, p. 1). I fully agree with this observation, and elsewhere (Sassen, Citation2008) have examined the variable instantiations of territory across time, long before the nation-state came about. In contrast, recent efforts to theorize territory in political science, legal scholarship, and political geography have generally equated it to the bounded spaces of national territorial sovereignty. Even where territory is allowed to escape this specific encasement, it has been construed as simply a matter of stretching or contracting of the boundaries demarcating spaces of territorial power or the deregulation of national borders (Krasner, Citation2009; Buxbaum, Citation2010). Though still rare, we now have a developing scholarship that constructs a more complex relation between territory and the state (e.g. Walker, Citation1993; Cutler, Citation1997, Citation2001; Berman, Citation2002; Brenner, Citation2004; Agnew, Citation2005; Raustiala, Citation2005; Gill, Citation2008; Elden, Citation2010; Painter, Citation2010; Kratochwil, Citation2011; Teubner, Citation2011, Citation2012).

In my own work (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapters 1, 2, 5, 7, 8), I have sought to escape this analytic flattening of territory into one historical instantiation, national-state territory, by conceptualizing territory as a capability with embedded logics of power and of claim-making. As a capability it is part of diverse complex organizational assemblages, with variable performance in relation to authority and rights, depending on the properties of such assemblages. For instance, territory is far less significant in Medieval Europe than is authority,Footnote1 but it gains importance with the emergence of the modern national state, and reaches its formal fullness in the twentieth century. And, as a capability, territory instantiates through a broad range of formats, including counterintuitive cases such as nomadic societies and complex systems that mix land sites and digital spaces, e.g. global finance.

Building partly on this earlier work, here I continue this interrogation of the category “territory” by focusing on its misalignments with the state's sovereign authority, and, further, the making of types of territory with few resemblances to national territory. The substantive rationality guiding this inquiry is that a focus on processes that cut across national borders does not only tell us about the weakening of sovereign authority over its territory, but also can make visible that territory takes on more formats than that of the national.

Specifically, I will focus on two types of misalignments. The first concerns the different types of instruments used by states to construct territoriality. For example, the USA uses mostly private law and avoids international law while Germany uses mostly public law and maximizes the use of international law (e.g. Buxbaum, 2010). I use these differences to make visible that territoriality, the legal construct, is not on a one to one with territory –the latter can deborder the legal construct and in this process show us something about the territorial itself.

This raises a major issue, and is the second misalignment at the heart of this paper. When some segment of a state's territory deborders its authority, as per current conceptualizations of territoriality, it leaves us with an unmarked kind of territory; this is a contradiction in terms since territory is a constructed condition. In other research, I have argued that some such segments cease being territory in that they are not a complex capability, as I define territory (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapters 1 and 8). They seem more akin to what old maps show as empty land because it is unknown. This terra nullius also matters to the larger project behind the current paper (see Sassen, Citation2013), because it may well signal the conceptual invisibility of territories that exit the state's territorial authority. In this case, we need to expand the meaning of territory beyond that of the national territorial state. One such meaning explored here is that of non-state jurisdictional encasement, including informal jurisdictions.

Empirically, a first step to address such debordering is to recognize emergent jurisdictions and orderings that override the state's territoriality. The most familiar instances are those of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Criminal Court (ICC), and the United Nations' humanitarian system. But there are multiple lesser known orderings as well (e.g. Berman, Citation2002; Schwarcz, Citation2002; Agnew, Citation2005; Merry, Citation2006; Painter, Citation2010; Teubner, Citation2011, Citation2012; Fredriksen, Citation2012). I use the fact of such jurisdictions and orderings to argue that they enable the making of new transversally bordered spaces that not only cut across national borders but also generate new types of formal and informal jurisdictions, or structural holes, deep inside the tissue of national sovereign territory. Theoretically I take it a step further, and interpret these spaces as elements in the making of a more complex and charged condition: distinct territories inside national-state territory itself.

THE UNSTABLE ALIGNMENT BETWEEN TERRITORY AND TERRITORIALITY

Territory is not ‘territoriality’. But territoriality as a legal construct that marks the state's exclusive authority over its territory has become the dominant mode of understanding territory. Historically, territoriality was a powerful innovation, and it has worked well to legitimate and cement the power of the modern state over a territory.Footnote2 It has traditionally been recognized as the primary basis of an international system, where the key organizing jurisdiction is that of the state's exclusive authority over its territory (e.g. Ruggie, Citation1993; Krasner, Citation2004; Brownlie, Citation2008). This holds even when the focus might concern the nationality of individuals outside the territory of a state making claims on that state (e.g. Joppke, Citation1998; Cutler et al., Citation1999; Knop, Citation2002).Footnote3

In what follows, I address four aspects of territoriality that matter for my analysis.

A first is the emerging instability of traditional versions of territoriality, partly as a consequence of globalization. Such instability is one window into asymmetries between territory and territoriality. While concerned with different questions from mine, Kratochwil (Citation2011; see also Citation1986) illuminates a particular aspect that matters to my argument about a growing asymmetry between territory and territoriality. He finds problematic the common assertion that the state constitutes an exclusive sphere of jurisdiction, writing

Usually we imagine the international system as consisting of sovereign units that all claim an exclusive space but whose writ does not go any further. In a way this notion is correct in that no jurisdictional claim against a foreign sovereign acting in official capacity can be sustained, but it is incomplete and thus misleading. States have traditionally interfered with each other through competing jurisdictional claims, precisely because states claim jurisdiction not only on the basis of territoriality, but—among other things—of ‘nationality’. (Citation2011, pp. 12–13)

specific colonial structure of power produced the specific social discriminations which later were codified as ‘racial’, ‘ethnic’, ‘anthropological’ or ‘national’, according to the times, agents, and populations involved … This power structure was, and still is, the framework within which operate the other social relations of classes or estates. (Quijano, Citation2007, p. 168)

An important issue for my analysis is the ongoing transformation of territoriality itself. Historically, Buxbaum notes, territoriality

referred to the exclusive authority of a state to regulate events occurring within its borders … Over the course of the twentieth century, the concept expanded to include authority over certain conduct that took place elsewhere but whose effects were felt within the regulating state. (Citation2009, p. 636)

In earlier periods of Western history, the constitutive elements for establishing jurisdiction, even after the Peace of Westphalia,Footnote5 often included rather more dynastic orderings than territoriality per se (Ford, Citation1999; Sassen, Citation2008, Chapters 2 and 3; Kratochwil, Citation2011). Indeed, while political scientists tend to see all that followed the Peace of Westphalia as involving what Krasner refers to as state territory (e.g. Krasner, Citation1999, Citation2004), this often obscures the many other criteria in play. The earlier period brings to the fore the asymmetric quality of territory and state authority, thereby, again, making visible that territory is not reducible to territoriality. It is with the modern state, and its full realization in the twentieth century, that our current understandings of the legal construct that is territoriality emerges as a dominant formal criterion.Footnote6

Territoriality as a legal construct—as territorial jurisdiction—Ford (Citation1999) argues, is a relatively recent development linked to the emergence of modern cartographic science and the normative ideology of a rational, humanist government. This meant that ‘we can speak of jurisdiction as a technology that was “invented” or “introduced” in a given social setting at a particular time’ (Citation1999, pp. 866–867). Moreover, Ford links the emergence of territorial jurisdiction to the rise of a discourse that

encourages individuals and groups to present themselves as organically connected to other people and to territory in a way that requires jurisdictional autonomy. It requires that citizens assert, emphasize and even exaggerate their organic connection if they are to present a compelling claim for the creation and protection of their jurisdiction. (Citation1999, p. 899)

Brighenti, moving more toward territory and away from jurisdiction in the narrow sense, posits that ‘law can be explored integrally as a territorial and territorialising device’ where territories are conceived as acts of territorialization and deterritorialization, rather than as spaces (Citation2010, p. 225). Acts of de/territorialization are also, according to Brighenti, acts of inscription, that is,

an act of drawing or tracing, a movement that is defined by its magnitude and direction. The intersection of movements corresponds to the moment of visibilisation of territorial boundaries. … And every such act of territorialisation or deterritorialisation bears a biopolitical significance, because it opens up the space in which the management of possible events taking place inside an irreducible multiplicity unfolds. Just like every other form of notation and writing, law, too, deals with lines, barring some and allowing others. (Brighenti, Citation2010, p. 225)

Critical geographers have made some of the most important contributions to the disentangling of territory, space and territoriality. The close examination of territory by Gottmann (Citation1973) and Sack (Citation1986) provides two early examples of the effort to specify the category of territory. Gottmann's analysis traces the historical development of territory and its association with the state authority back into antiquity while Sack systematically explores territory both at different scales—from nation-states down to individual work spaces—and across three broad historical periods—primitive, pre-modern and modern. While contributing greatly to the understanding of territory as a socio historical construct, for both authors territory and territoriality are consistently linked to one another. I would agree with this, but only insofar as territoriality can be conceptualized in a more generic sense than its current narrow meaning as the state's exclusive territorial authority.

Among the most theoretically developed contemporary scholarship on the necessary intersection of state and territory is the work of Elden (Citation2010)Footnote7 and Brenner (Citation2004). For Brenner (e.g. Citation2004) recent changes in the ordering of state spatial processes involve complex instances of deterritorialization and reterritorialization, which together reconfigure the territorial articulations of state policies and institutions. While its internal particulars may be undergoing reconfiguration, territory remains tied to state territorial sovereignty. Further, in their interpretation of Lefebvre, Brenner and Elden (Citation2009) write that state, space and territory are all historical constructions.

By this we mean not simply that the state, space and territory are combined in specific ways at different times, but that the social forms denoted by each of these terms emerge only at particular historical junctures and are mediated through tangled yet distinctive lineages. (Citation2009, p. 364)

Where for Brenner, current changes in the spatial ordering of political and economic processes are indicative of the ongoing reconfiguration of state space as territory, for Agnew (Citation2005) such changes signal that aspects of national sovereignty have become non-territorial in nature. For Agnew (1994, Citation2005), space becomes the larger necessary category, one that includes territory as one of its instantiations. That is, to the extent that networks and other non-contingent spatial orderings are becoming more evident, territories—seen as bounded ‘blocks of space’ (Citation2005, p. 441)—are losing their exclusive claim on state sovereign power. Here territory is understood as contingent, bounded space, which, though not necessarily national, is most powerfully demarcated along national-state territorial lines. Underlining this understanding, Agnew uses the phrase ‘territorial trap’ (Citation1994) to describe analyses that fail to account for state-based processes that extend beyond the set boundaries of nation-states.

Taylor (Citation1994, Citation1996) also allows for a notion of territory that can be organized around a vector that is not the state, notably wealth, thereby freeing up the category territory from its national encasement. We see this when he defines territory as bounded space and territoriality as behavior associated with its use, and that the meanings of such use can change in the current global era. Regarding this current era, Taylor concludes that we are seeing ‘the continuing use of territory but at different scales—the state as a power container tends to preserve existing boundaries; the state as wealth container tends toward larger territories; and the state as a cultural container tends toward smaller territories’ (Citation1994, p. 160). That is, to the extent that there are apparent ‘leaks’ in the national ‘container’, Taylor posits that these can be explained through a widening or contracting of the borders of territory-as-bounded-space depending on the diverse realms of social activity.

This type of conceptualizing goes in the direction of what I am after here. While Taylor develops this eventually in later work on cities in the global economy (e.g. Citation2000, Citation2004), in his earlier work he still sticks closely to the state. Specifically, he writes:

Territoriality is a form of behaviour that uses a bounded space, a territory, as the instrument for securing a particular outcome. By controlling access to a territory through boundary restrictions, the content of a territory can be manipulated and its character designed. (Citation1994, p. 151)

This awesome power [of the state] has been made possible by a fundamental territorial link that exists between state and nation. All social institutions exist concretely in some section of space but state and nation are both peculiar in having a special relation with a specific place. A given state does not just exist in space, it has sovereign power in a particular territory. Similarly, a nation is not an arbitrary spatial given, it has meaning only for a particular place, its homeland. It is this basic community of state and nation as both being constituted through place that has enabled them to be linked together as nation-state (Taylor, Citation1993, pp. 225–228). The domination of political practice in the world by territoriality is a consequence of this territorial link between sovereign territory and national homeland. (Citation1994, p. 151)

A second aspect of the relation of territoriality to territory pertinent to my concern here are today's specialized differences across countries in terms of the instruments used to specify or construct territoriality (Zumbansen, Citation2012, pp. 115–127). These differences are one window into the disentangling of the two categories, territory and territoriality. Significant to this disentangling is that such differences are also present among countries that belong to the same geopolitical context and operate within the same larger geopolitical period. For instance, Buxbaum (Citation2009) examines the different instruments used by the USA and Germany to constitute their territoriality. These are both liberal democracies that center statehood in this type of jurisdiction; further, over time both have elaborated the technical aspects of territoriality and in many ways arrived at similar modifications. Yet, and this is what matters to my argument, each uses very different legal instruments from the repertory of liberal democracies in constructing the relationship between territory and territoriality (Buxbaum, Citation2009). To simplify, and as already mentioned, the USA uses largely private law, and avoids international law when it can, whereas Germany uses largely public and international law.Footnote8 This is not the place to engage in a detailed examination of these differences: my main concern is with how states have used distinct instruments to produce what at a more generic international level gets constituted as a standardized jurisdiction, today enshrined in the Hague Treaty.

Third, the fact that we see a growth in the number of cases and issues where territory is not part of jurisdictional rules is, for my purposes, yet another way of making visible today's asymmetries between territory and territoriality. Thus Teubner (Citation2004, Citation2012) has argued for a global civilian jurisdiction autonomous from the state, partly picking up on the Luhmannian conception of distinct spheres through which a system is organized (e.g. Luhmann, Citation1995[1984]; see also Law, Citation1993; Sassen, Citation2011). Coming from a critical perspective, Raustiala argues against ‘legal spatiality’ (see above), noting that, today, states regularly assert jurisdiction beyond their national territory. In the case of the USA, he writes,

The United States has many statutes that explicitly assert extraterritorial jurisdiction, and others that do not but have been so construed by the Executive branch and the courts. Other states have done the same. While such assertions of extraterritoriality are ever more common, in some cases, spatial location itself becomes hard to determine—as in many recent Internet cases. As technology evolves, legal spatiality becomes harder to apply and, increasingly, harder to justify as a jurisprudential principle. (Raustiala, Citation2005, pp. 111–112)

This type of analysis has a kind of obverse pertinence to my analysis: national-state jurisdictions that deborder territoriality and non-state jurisdictions that escape the grip of national-state territoriality. One example of the second type is the environmentally driven recognition of the ‘natural habitat of fisheries’. When such habitats cut across interstate borders, it can lead to some of the more intractable international disputes, given the difficulty of adjusting such habitats (read territories) to existing territorial state authority (e.g. the long-standing legal dispute between Canada and the USA).

Berman (Citation2002) makes a similar argument to Raustiala's, asserting that, in the current global age, national jurisdiction should not be automatically coupled with national territory. In making his argument, Berman emphasizes the various attachments to territory which give it meaning, only one of which is national, writing ‘In our daily lives, we all have multiple, shifting, overlapping affiliations. We belong to many communities. Some may be local, some far away, and some may exist independently of spatial location’ (Citation2002, p. 543). Jurisdiction, he goes on, ‘is the way that law traces the topography of these multiple affiliations … Conceptions of jurisdiction become internalized and help to shape the social construction of place and community. In turn, as social conceptions of place and community change, jurisdictional rules do as well’ (Citation2002, p. 543).

Agnew also weakens the link with the state when he defines territory as ‘blocks of space’ (Citation2005, p. 441) and territoriality as ‘the use of territory for political, social, and economic ends’ (Citation2005, p. 437). As noted above, for Agnew territory is not necessarily ‘state space’ (cf. Brenner, Citation2004), even though it is necessarily a contingent, bordered area of space. In this view, territory can be demarcated at many levels, including the national, but also the local, regional, continental, and so on (see also Sack, Citation1986). Critically, however, Agnew does not include networked or otherwise non-continuous spaces in his definition of territory.

Also moving in the direction of my concerns is Painter’s (Citation2010) argument against formulations of territory that tie it to state sovereign space or see it as otherwise clearly bounded and non-overlapping. I also agree with Painter's proposition that territory is enacted through extensive networks of human and non-human actors. Using the empirical example of UK administrative regions, Painter shows how territories are brought into being through extensive networks involving international accounting standards, models, maps, material and digital infrastructures, accountants, statisticians, clerks, technicians, researchers, journalists, and myriad other human and non-human actors. He suggests that the geographies of these networks—being widely dispersed in space and time—differ from the geographies of the territory they generate, ‘which is usually understood to involve a bounded and continuous portion of space’ (Painter, Citation2010, p. 1096). He writes that,

The phenomenon that we call territory is not an irreducible foundation of state power, let alone the expression of a biological imperative. It is not a transhistorical feature of human affairs and should not be invoked as an explanatory principle that itself needs no explanation: territory is not some kind of spatio-political first cause. (Citation2010, p. 1093)

Fourth, the dilution of the state's formal power over its territory tends to take on specific forms and produce specific redistributions of power across diverse state branches. Very briefly, national legislative jurisdictions have lost their grip on a growing range of domains over which they once had regulatory power, or at least formal authority. One mode of adapting to this loss has been to pass laws that deregulate and privatize what was once regulated and public and where legislatures were the key state branch. Deregulation and privatization have led to a widespread understanding that the ‘national state’ loses authority with globalization. Elsewhere (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapter 4), I have examined how this has reduced the power of national legislative jurisdiction, even as it has allowed a relatively greater concentration of unaccountable power in the executive.

Out of this mix of transformations, I (Sassen, Citation1996, Chapter 1; Citation2008, Chapters 4 and 5) have emphasized two features in my prior work. First, sovereignty is being partly disassembled, including formally, over the last 20–30 years, depending on the country. While much remains formally included in the national state and sited in national state territoriality, some of it has shifted to other institutional spaces. Sovereignty remains a key systemic property but its institutional bases diversify. The second point is that even as globalization has expanded, territoriality remains a key ordering in the international system. But it does so with one difference, it now feeds above all, the power of the executive branch of government, a power that becomes increasingly privatized (Sassen, Citation2008, pp. 165–220). Some components of the state's territorial authority, especially of the legislature, shift to other institutional homes, notably an emergent jurisdiction of global regulators.

In this article, I build on both of these earlier propositions, but the focus is different. I examine how territoriality can make visible what it formally hides: that territory is much more than national-state territory. And through the recovery of this expanded meaning, we can make territory work analytically, in contrast to its current univocal meaning in most of the scholarship about the state and about globalization. The effort is a more careful tracking of emergent conditions and dynamics that signal that the cages of national territorial authority are breaking, and that in a few instances this becomes materially visible and in others this visibility is inferential. To capture the meaning and import of this breakage, I use the notion of the making of informal jurisdictions because what I seek to capture either escapes established jurisdictions or worms itself into the latter and can easily be confused with such established jurisdictions.Footnote9

This is the subject of the next section.

TRANSVERSALLY BORDERED SPACES AND THEIR TERRITORIAL ENGAGEMENTS

A state border is not simply a borderline. It is a mix of regimes with variable contents and geographic and institutional locations.Footnote10 Different flows—of capital, information, professionals, undocumented migrants—each constitute bordering through a particular sequence of interventions, with diverse institutional and geographic locations. The actual geographic border matters in some of these flows and does not in others. That geographic borderline is part of the cross-border flow of goods if these come by ground transport, but not of capital, except if actual cash is being transported. Each border-control intervention can be conceived of as one point in a chain of locations. In the case of traded goods, these might involve a pre-border inspection or certification site. In the case of capital flows, the chain of locations will involve banks, stock markets, and electronic networks. In short, the geographic borderline is but one point in the chain. Institutional points of border-control intervention can form long chains moving deep inside the country. Yet notwithstanding multiple locations and diverse levels of control, the national border has a recognizable point of gravity.

Beyond this familiar mix of regimes and locations for border-control functions, what concerns me here is the formation of new types of bordering capabilities that shape bordered spaces transversal to traditional state borders. These transversal spaces are to be distinguished from the more general growth in cross-border flows which are governed by national states even if in the form of deregulated national borders; this includes most of the international trade and finance, migration, cultural exchanges, and much more. The novel bordered transversal spaces that I focus on here enable an emergent segment of actors, including firms, professionals, and a sub-species of money and goods, to move across traditional borders and to do so under very specific conditions: the making of internal borders within the larger framing that is state territoriality. In some cases, these new types of internal borders are impenetrable. No coyote can take you across these borders even though they are inside the geographic space of the nation-state. They also function as formal borders vis-à-vis the national state itself, even if the latter has the power to violate the treaty laws or informal arrangements that are at their origin (Sassen 2009).

These transversally bordered spaces entail the making of distinct, albeit elementary territories and jurisdictions inside nation-states. Some of this making is as yet informal, not fully recognized nor knowingly authorized, such as the new types of (still) legitimate private financial networks referred to as ‘dark pools’. But some of it is now part of international treaty law, such as the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) ‘Mode 4’. And much of it is in a process of becoming, such as the global operational space that allows firms to conduct themselves as if they are global even though there is, as of now, no such legal persona as a global firm (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapters 5 and 8).

Such distinctive types of jurisdictions inside national territory make legible a second type of asymmetry between territory and territoriality besides that discussed in the previous section. The diverse regimes that constitute the border as an institution can be grouped, on the one hand, into a formalized apparatus that is part of the interstate system and, on the other, into an as yet far less formalized array of novel types of borderings lying largely outside the framing of the traditional law governing the interstate system and outside the geography of state borders. The first has at its core the body of regulations covering a variety of international flows—flows of different types of commodities, capital, people, services, and information. No matter their variety, these multiple regimes tend to cohere around (a) the state's unilateral authority to define and enforce regulations on its territory, and (b) the state's obligation to respect and uphold the regulations coming out of the international treaty system or out of bilateral arrangements.

The second major component, the new type of bordering dynamics arising outside the framing of the interstate system, does not necessarily entail a self-evident crossing of borders. It includes a range of dynamics arising out of specific contemporary developments, notably emergent global legal systems and a growing range of globally networked digital interactive domains.Footnote11 Global legal systems, still rare, are not centered in state law—that is to say, they are to be distinguished from both national and international law. And global digital interactive domains are mostly informal, hence outside the existing treaty system; they are often basically ensconced in sub-national localities that are part of cross-border networks.Footnote12 The formation of these distinct systems of global law and globally networked interactive domains entails a multiplication of bordered spaces. But the national notion of borders as delimiting sovereign territorial states is not quite in play. Rather, the bordering operates at either a trans- or supranational or a sub-national scale. And although these spaces may cross national borders, they are not necessarily part of the new open-border regimes that are state-centered, including such diverse regimes as those of the global trading system and legal immigration. Finally, insofar as these are bordered domains, they entail a novel notion of borders.

These emergent conditions do not necessarily override sovereignty. But its institutional location and its capacity to legitimate and absorb most of the power to legitimate have become unstable. The politics of contemporary sovereignties are far more complex than notions of mutually exclusive territories can capture. Elsewhere I have argued that

Sovereignty and territory … remain key features of the international system. But they have been reconstituted and partly displaced onto other institutional arenas outside the state and outside the framework of nationalized territory. … sovereignty has been decentered and territory partly denationalized. (1996, pp. 29–30)

In what follows, I first briefly describe some quite elementary but formalized instances of these bordered transversal spaces that insert another jurisdiction inside national territory, one that can override that of the national state, or, at the minimum, that national states have been forced to sign onto. Next I focus on some more complex and ambiguous developments that may or may not become fully formalized. At its most abstract, the fact of supranational jurisdictions inside national territory is not new. Extraterritoriality can be seen as a major long-standing feature of the interstate system, as are specific jurisdictions concerning organized religions, among others. There are vast bodies of scholarship about these and other long-standing special jurisdictions; this is not the place to review them. My concern here is with newly established jurisdictions that emerge out of the features and conditionalities of the post-1980 world, and my aim, to repeat, is to detect the distancing between territory and territoriality as these have come to be understood in the literature about the national state.

WTO GATS ‘Mode 4’

A first formalized instance of a transversally bordered space comes in the form of the fourth mode through which services may be traded under the WTO GATS. Commonly referred to simply as ‘Mode 4’, it governs the movement of people across national borders for the purposes of the transnational supply of services. Aside from the principle of non-refoulement in international refugee law,Footnote13 Mode 4 is the only binding mechanism on the matter of admitting foreigners within national sovereign territory that operates outside of national authority (Panizzon, Citation2010, Citation2011). As such, Mode 4 partly overrides national territorial sovereignty, but only partly. To start, it is only a very narrow category of transnational movement that Mode 4 governs: Mode 4 only applies to individuals moving for the purpose of working in one sector—services—and only allows individuals to move across borders for a specific purpose (i.e. to fulfill a specific contract or work for a specific company) (IOM, Citation2012). In addition, Mode 4 covers only ‘temporary movement’ and, therefore, does not apply to the transnational movement of people seeking citizenship, residence or employment on a permanent basis. Most transnational movement of persons, then, remains under national jurisdictional control.

National authorities retain a say in how Mode 4 is applied within their national territories. That is, they may negotiate the practical terms by which their national visa system will be made to comply with Mode 4. One major outcome of this interplay between national authorities and the authority of Mode 4 is that the emergent bordering of territory enacted by Mode 4, as it extends into national sovereign territories, is marked by its exclusion of non-elite workers. While in principle Mode 4 is meant to apply to all private service sector workers, in practice, Mode 4 is used to facilitate the transnational movement of highly skilled and educated service workers, especially intra-corporate transferees with ‘essential skills’ (i.e. managers, technical personnel) and high level business professionals, largely to the exclusion of unskilled service workers (WTO, Citation2009). Thus for the unskilled workers of the world, who of course vastly outnumber the highly skilled, the transversal space bordered by Mode 4 is one they cannot access; instead for these workers, territory remains largely tied to national sovereignty—to territoriality.

The ICC

A second formalized instance of a transversally bordered space is that constituted through the ICC. The ICC is an independent and permanent court of criminal justice seated in The Hague. In contrast with the International Court of Justice (the judicial arm of the UN system which settles disputes between states), the ICC does not try states, but individuals. The ICC also breaks with other regimes of international criminal justice in its provision for the rights of individual victims, giving individual victims the right to have their voices heard before the court and, where judged appropriate, to receive reparations for their suffering. Cases are brought before the ICC following investigations by the ICC Prosecutor and approval by a pre-Trial Chamber of ICC Judges. Investigations can be initiated by the ICC Prosecutor based on a referral from any State Party, referral from the UN Security Council, or propio motu, meaning on his/her own initiative. Propio motu investigations follow preliminary examinations of situations brought to the attention of the Prosecutor by individuals and/or organizations and must gain approval from a pre-Trial Chamber before they can proceed. Critically, individuals and organizations can bring situations directly to the attention of the Prosecutor and present evidence in support of their claims without having to pass through any national channels.Footnote14

The scope of the ICC's jurisdiction is limited to crimes of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity committed after the Rome Statute came into force on 1 July 2002. Moreover, the reach of ICC's jurisdiction is limited to crimes committed by nationals of, or within the national territory of, State Parties or states otherwise accepting the court's jurisdiction (which may occur on an ad hoc basis for particular situations)—notably, as of 1 July 2012, the USA, Russia and China were not among the 121 State Parties to the Rome Statute. At the same time, an exception to this can be made in cases where a situation is referred to the ICC by the UN Security Council, which can refer situations regardless of the nationality of the perpetrators or the national territory in which the alleged crime was committed.Footnote15

While the jurisdiction of the ICC borders a transversal space that cuts across national territories and overrides national sovereign authority, it also depends on national sovereign authorities to maintain and enforce its borders. That is, the ICC relies on State Parties to the Rome Statute and on the UN for assistance in arresting persons wanted by the Court, providing evidence for use in proceedings, relocating witnesses, and enforcing the sentences of convicted persons. Accordingly, it has been suggested that the ICC be thought of as a global system that is reliant on the interaction of and cooperation between international and national authorities (Rastan, Citation2007).

Fairtrade

A third formalized transversally bordered space is the Fairtrade system. Though formal and recognized, it lacks the legal enforcement of Mode 4 or the ICC. Most contemporary food certification and labeling schemes—including certifications such as ‘organic’ and ‘GMO-free’—are functional only within the bounded, contingent space of national territory; all aspects of their administration, regulation, production and so on, are spatially ordered and governed in accordance with the spaces of national territorial sovereignty. In contrast, Fairtrade (not to be confused with the generic term ‘fair trade’) is a specific assemblage constituted around the Fairtrade certification and labeling system and its associated FAIRTRADE® Mark, which acts within and across national territorial borders (Stiglitz and Charlton, Citation2005; Rodrik, Citation2011, Chapter 10). It draws together farmers, farms, products, markets, consumers and civil society actors around a logic of making global trade in specified goods more fair. In so doing, Fairtrade constructs a transversal bordering in which non-contingent spaces from within national territories are aligned with each other and with global NGOs (in this case Fairtrade International, or FLO, and its subsidiary FLO-CERT).

However, while Fairtrade's bordering applies its own governing logic—of making trade fairer—separately from sovereign state authority, it does not compel sovereign authorities to act in accordance with its authority, as is the case with Mode 4. Fairtrade sets its own standards for labor practices and trade, governed by its own logic of fairness, separate from national labor laws and trade regulations. But while Fairtrade standards are generally more exacting than national laws, they are not in opposition to national legal authority. Instead, Fairtrade's distinct logic marks out a novel voluntary jurisdiction that inserts itself simultaneously in several sovereign state territories.

Cross-Border Mobilities of Forced Migrants

In addition to the three examples of formalized transversally bordered spaces given above, a number of informal spaces are also becoming apparent. One such space is being enacted through the informal movement of forced migrants after their initial displacement. Until recently, the movements of forced migrants have been conceptualized by UN agencies and international organizations as involving the unilinear movement of people into camps during an emergency, followed by their movement out of camps for return or resettlement during recovery. This pattern of movement fits into a traditional understanding of the roles of national territorial sovereignty and citizenship in forced displacement. This is particularly so for refugees, for whom the act of crossing an international border bestows a special international legal status—one that is removed once they re-cross the border to return home at the end of a crisis. However, a growing body of research contradicts this understanding as it shows that forced migrants engage in complex strategies of mobility between camps and places of return or resettlement (Bartlett, Citation2007; Fredriksen, Citation2012). Further, refugees go back and forth across international borders in order to pursue livelihoods, manage their social, cultural and political networks and identities, and react to changing security situations (e.g. Hovil, Citation2010; Kaiser, Citation2010; Long, Citation2010, Citation2011), while maintaining access to services like schools, health care, and water, food and material distributions linked to residence in the camp (AVSI and UNHCR, Citation2009, p. 14).

Long (Citation2010, Citation2011) suggests that these strategic movements of forced migrants back and forth across borders and in and out of displacement camps signals an emergent, informal re-bordering of citizenship along lines of complex support and livelihood networks rather than traditional lines of national territorial sovereignty. Correspondingly, we can detect in this movement an emergent, informal bordering of a space that cuts across national territories and elides sovereign authority. It is defined, instead, by transnational social, cultural, political and economic networks and affective attachments. In some cases, this transversal space partly replaces national sovereign authority, such as where national authority has been weakened to the extent that it can no longer exert control over its national borders (this is the case, for example, in Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo). In other cases, this transversal space is dependent on national authority, as where host governments legislate the so-called ‘freedom of movement’ for forced migrants enabling them to move freely in and out of camps (as did the government of Uganda in the mid-2000s).

Off-Exchange or Over-the-Counter Trading: ‘Dark Pools’

A very different type of informal transversal bordered space is that constituted by the private global trading networks run by individual banks or brokers known as ‘dark pools’. These networks for off-exchange trading or over-the-counter trading are in competition with public stock exchanges and operate in ways not allowed on public exchanges. Dark pools allow anonymous buyers and sellers to trade directly with each other away from public exchanges and without having to make prices available to all investors as they would have to on a public exchange. Data on dark pool trades are published only after trades are completed, so that investors can take, or offload, large positions in quoted companies without alerting the wider market. ( The Economist , Citation2011; TABB). Meanwhile the broker-dealers and banks that set up their own dark pools are able to capture transaction fees from clients that would otherwise be paid to public exchanges.

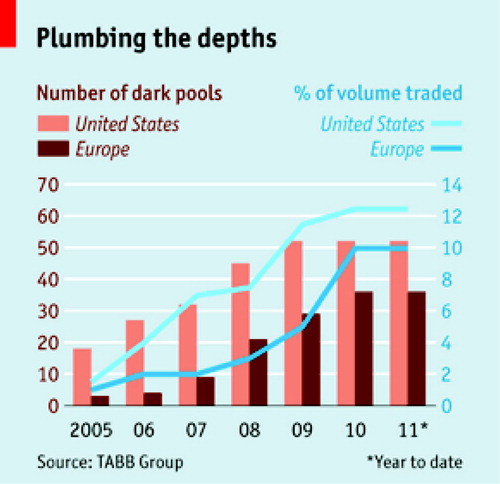

Dark pools have proliferated in the past six years (see ). Originally meant for large institutional investors, they increasingly attract high-frequency traders, who make huge numbers of trades at low amounts. The Federation of European Stock Exchanges recently said that its members were concerned that these private trading venues were ‘operating in an environment that is turning increasingly less transparent, more fragmented and less regulated’ (quoted in Grant, Citation2011). Thus dark pools, even while formally not in violation of any law, are a bordered space of private financial transactions that is increasingly free from national and international regulatory authorities.

EMERGENT TERRITORIAL FORMATIONS

Footnote16Let me next turn to instances that are broader and less clearly defined than the five cases discussed above. They are part of the same transversalizing of territorial encasings that cut across national borders and are not fully, if at all, subsumed under national-state jurisdiction. They unsettle the institutional framing of territory that gives the national-state exclusive authority in a very broad range of domains. The territory of the national is a critical dimension in play in all these instances: diverse actors can exit the national institutionalization of territory yet act within the geographic terrain of a nation-state. Further, I argue, this exiting is not simply an exiting into nowhere. It entails an active making of a territory (inside an already existing territory, that of the nation-state) and an informal jurisdiction that is legible to the national state (e.g. WTO GATS Mode 4, Fairtrade) or not so (e.g. the so-called ‘dark pools’ discussed above). These emergent formations are not part of existing extraterritorial arrangements. What gives weight to these formations is not simply a question of novelty but their depth, spread, and proliferation. At some point, all of this leads to a qualitatively different aggregate. We can conceive of it as emergent institutionalizations of territory that unsettle the national encasement of territory.

A first instance is the development of new jurisdictional geographies. At one extreme are new and highly formalized jurisdictions, such as the ICC discussed above. At the other, are experimental jurisdictions, assembled out of bits and pieces of established, often older, jurisdictions. Legal frameworks for rights and guarantees, and more generally the rule of law, were largely developed in the context of the formation of national states. But now some of these instruments are strengthening interests that are not necessarily national, such as those of multinational firms and global finance. As these older legal frameworks become part of new types of transnational logics they can alter the valence of older national-state capabilities, e.g. marking as negative a broad range of regulations that might constrain the search for profits. Further, in so doing, they are often pushing these national states to go against the interests of national firms. A second instance is the formation of triangular cross-border jurisdictions for political action, which once would have been confined to the national. Electronic activists often use global campaigns and international organizations to secure rights and guarantees from their national states. Furthermore, a variety of national legal actions involving multiple geographic sites across the globe can today be launched from national courts, producing a transnational geography for national lawsuits. The critical articulation is between the national (as in national court, national law) and a global geography outside the terms of traditional international law or treaty law.

A good example is the set of lawsuits launched by the Washington-based Center for Constitutional Rights in a national court against nine multinational corporations, both American and foreign, for abuses of workers' rights in their offshore industrial operations. The national legal instrument they used to launch and legitimate these lawsuits was the Alien Torts Claims Act, one of the oldest in the USA, originally designed to deal with overseas pirates, which had not been used with a few exceptions for many decades (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapter 8). With this old instrument they constructed a global three-sited jurisdiction, with several locations in at least two of those sites: the locations of the headquarters of the firms being sued, which included both US and foreign firms, the locations of the offshore factories (several countries), and the court in Washington where the lawsuits were submitted and accepted. Even if these lawsuits fail to achieve their full goal, they set precedents showing it is possible to use a national law in a national court to sue US and foreign firms for questionable work practices in their offshore factories. Thus, besides the new courts and instruments (e.g. the new ICC, the European Court of Human Rights), what this case shows is that components of the national rule of law that once served to build the strength of the national state, can today contribute to the formation of transnational jurisdictions.

On the other hand, and this is a second case, states can be active participants in the making of protected jurisdictions for firms operating globally. In this case, state instruments are used to make such global actors more autonomous from the regulatory power of the state by granting them guarantees of contract, private property protections, and, often, diverse exemptions from taxes and other obligations (and in so doing, they often go against the interests of local national firms). This has been critical in strengthening the global economy, as it has de facto constructed a standardized global space for the operations of national firms as there is no such legal persona as a global firm. Firms have pushed hard for the development of new types of formal instruments, notably intellectual property rights and standardized accounting principles that have further strengthened that global operational space. These various state interventions have contributed to produce an operational space that is increasingly denationalized even as it is inserted in the sovereign territory of a growing number of national states. I see here much more than the weakening of interstate borders: it is an instance of a non-national territory inside national-state territory. These are the elements of an organizing logic that is not quite part of the national state even as that logic installs itself in that state, and does so in what is now a majority of national states worldwide. This is a very different way of representing economic globalization than the common notion of the withdrawal of the state at the hands of the global system. Indeed, to a large extent, it is the executive branch of government that is getting aligned with global corporate capital and ensuring this work gets done (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapter 4).

A third case is the formation of a global network of financial centers. We can conceive of financial centers that are part of global financial markets as constituting a distinct kind of territory, simultaneously pulled in by larger electronic networks and functioning as territorial micro-infrastructures for those networks. These financial centers inhabit national territories, but they cannot be seen as simply national in the historical sense of the term, nor can they be reduced to the administrative unit encompassing the actual terrain (e.g. a city), one that is part of a nation-state. In their aggregate, they house significant components of the global, partly electronic market for capital. As localities, they are denationalized in specific and partial ways. In this sense, they can be seen as constituting the elements of a novel type of multi-sited territory, one that diverges sharply from the territory of the historic nation-state.

What this participation of the state means is that components of legal frameworks for rights and guarantees, and more generally the rule of law, largely developed in the process of national state formation, can now strengthen non-national organizing logics. As these components become part of new types of transnational systems, they alter the valence of (rather than destroy, as is often argued) older national-state capabilities. Where the rule of law once built the strength of the national state and national corporations, key components of that rule of law are now contributing to the partial, often highly specialized, denationalizing of particular national-state orders (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapter 5).

A fourth type of emergent jurisdiction can be found in the global networks of local activists and, more generally, in the concrete and often place-specific social infrastructure of ‘global civil society’. Global digital networks and the associated imaginaries enable the making of that social infrastructure. But localized actors, organizations, and causes are also key building blocks. The localized involvements of activists are critical no matter how universal and planetary the aims of the various struggles. Global electronic networks actually push the possibility of this local–global dynamic further. Elsewhere I have examined the possibility for even resource-poor and immobile individuals or organizations to become part of a type of horizontal globality centered on diverse localities. When supplied with the key capabilities of the new technologies—decentralized access, interconnectivity, and simultaneity of transactions—localized, immobilized individuals and organizations can be part of a global public space, one that is partly a subjective condition, but only partly because it is rooted in the concrete struggles of localities. I see here an emergent global informal jurisdiction centered in localities, constituted by local, mostly immobile actors engaged in specific struggles or projects—getting rid of the torturer in their local jail, or the factory polluting the water in their community. There is here then a strong territorial moment deep inside the state's territory but which belongs to a multi-sited global horizontal space for struggle. It is in some ways a parallel to the global multi-sited operational space of finance, marked by its struggle—maximize profits.

We can conceive of these minor formations as shaping an emergent field of forces inside national territory whose interactions with the state's jurisdiction are as of now ambiguous and even invisible to the eye of the law. Strictly speaking, I would argue that they constitute distinct territories, each with its specific embedded logics of power and of claim-making. In the larger picture of authority, they are minor and some at least are informal jurisdictions. Minor and informal as they are, I want to use them as lenses onto the question of territory and its expanded meaning beyond national territory. What is compelling about these cases is that they take shape and roots deep inside what has been constructed, and continues to be construed, as national territory.

These emergent assemblages begin to unbundle the traditional territoriality of the national, historically constructed overwhelmingly as a national unitary spatio-temporal domain.

CONCLUSION

The question of a bordered territory as a parameter for authority has today entered a new phase. States' exclusive authority over their territory remains the prevalent mode of final authority in the global political economy; in that sense, then, state-centered border regimes—whether open or closed—remain foundational to our geopolity. But at least some of the critical components of this territorial authority are actually no longer national in the historically constructed sense of that term. They are, I argue, denationalized components of state authority: they look national but are actually geared toward global agendas, some good, some not so good at all.

State borders, with all their continuing formal weight and practical flexibility, are merely one of several key elements in a larger operational space that began to take shape in the 1980s and today deborders the interstate system. This type of debordering needs to be distinguished from older types, some still ongoing, such as the presumptions of dominant powers to violate the sovereignty of weaker countries. It is a debordering that constitutes new types of bordered spaces inside national territory itself. These may be internal to a state's territory or cut across state borders. To give them conceptual visibility I argued that they are a distinct, albeit partial jurisdiction not generated by or dependent on the state itself. In so doing, they make legible asymmetries between the state's sovereign jurisdiction and the territory itself. Thus, the making of this formation needs to be distinguished from the mere fact of cross-border flows, whether pre- or post-deregulation.

This does leave us with a question as to what forces shape these diverse meanings of territory that go beyond the still prevalent and dominant national-state meaning. Defining territory as marked by embedded logics of power and of claim-making helps make visible the jurisdictional features of both the new internal and transversally bordered spaces examined in this article. These spaces can be elementary (the spaces of the Occupy movements) or complex (the territory of global finance, a mix of digital networks and global cities). Thus, it is not illuminating to see Wall Street as simply a national territory, nor is it useful to confuse the Occupy movements with a demonstration. Each is a project that makes a distinct territory.

These diverse meanings put the category territory to work analytically. And they bring to the fore the issue of who has border-making capabilities.

If there is one sector where we can begin to discern new stabilized bordering capabilities and their geographic and institutional locations, it is in the corporate economy. Strategic agents in this shifting meaning of the territorial and of bordering are global firms and financial networks. Most sovereign states in the world have now formalized the right of such firms and networks to cross-border mobility. This, in turn, has produced a large number of highly protected bordered spaces that cut across the conventional border, are exempt from significant elements of state authority, and while known to state authorities are actually marked by considerable regulatory invisibility; the so-called dark pools of finance discussed here are one major example.

We see a simultaneous shift to increasingly open geographic state borders along with transversally closed bordered spaces. The former are far more common and formalized for major corporate economic actors than they are for citizens and migrants; the growing exception is the emergent global class of individuals who are top-level global economic players. Neoliberal policies, far from making this a borderless world, have actually led to a new type of bordering that allows firms and markets to move across conventional borders with the guarantee of multiple protections as they enter national territories. Firms and this new global class are now enveloped in multiple new types of institutionalized protections through these new transversal bordering capabilities, while citizens and migrants lose protections and have to struggle to gain such new types of transversal protections.

My effort here was to argue that these transversally bordered spaces are not merely a sub-species of cross-border flows, but constitutive of distinct territorial capabilities. These capabilities can be mobilized for a broad range of dynamics, including some with scale-up potentials that can unsettle the territorial authority of the state. They signal that territory, as an analytic category, cannot be confined to its national instantiation, even if this is the dominant one. This confinement keeps this category from working analytically. Conceived of as a complex capability, it can be shown to have more meanings than are signaled by prevalent notions of territoriality. It deborders territoriality—that singular encasement that constitutes it as national territory. In so doing, a focus on territory makes legible conditions that are at risk of remaining blurry, in the shadow of national-state territoriality.

Notes

As Gottmann (Citation1973) notes, in Medieval Europe the concept of patria (fatherland) preceded that of territory.

While exclusive territorial rule existed in Greek city-states (Gottmann, Citation1973), in Europe of the Middle Ages territoriality was weak because a given territory was more often than not subject to overlapping and even competing authorities and a lack of clear borders (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapter 2). In a non-Western example, Ford uses the case of Thai rule to point to ‘a non-bounded, fluid and ambiguous notion of territory’ prior to the establishment of territorial jurisdiction in the nation-state model during the late nineteenth century (Ford, Citation1999, p. 868)

Kratochwil identifies four principles invoked by states in claiming jurisdiction based on nationality, writing

When claims concern the protection of their nationals, the passive nationality principle supplies the reasons; when states subject their subjects to the extraterritorial reach of domestic legislation, the active nationality serves as a basis. Furthermore, states claim jurisdiction over activities beyond their boundaries if those activities threaten their existence or proper functioning as a state (protective principle). Finally, jurisdiction can be claimed against perpetrators of international crimes on the basis of the universality principle, to leave aside the possibility of jurisdiction on the basis of a special treaty (stationing agreements). (Citation2011, p. 13, emphasis original)

This generated a strong and cross-disciplinary debate beginning in the 1990s and continuing today about the traditional bases of state power and authority over its territory. See, for example, Cerny (Citation2000), Gill (Citation1996), Cutler and Gill (Citation2013), Hirst and Thompson (Citation1996), Helleiner (Citation1999), Pauly (Citation2002), Held and McGrew (Citation2007) and Miller and Zumbansen (Citation2011).

One of the primary tenets of the Peace of Westphalia was the recognition of each party's exclusive sovereignty over their lands and people, which is why it has often been identified as the beginning of the nation-state system although I (Sassen, Citation2008, Chapter 2), along with others (e.g. Wallerstein, Citation1974; Ford, Citation1999), would locate the emergence of territorial state sovereignty in Europe earlier, in the thirteenth century, with the rule of the Capetian kings in what is now France.

A separate issue is that of the state as ‘representer’ of its people and of the domain, a condition that also took a while to happen; on the issue of an ‘authorization’ theory of representation, see Pittkin (Citation1972), Neuman (Citation1996), Sassen (Citation1996, Chapter 2, Citation2008, Chapter 6).

Elden (Citation2007, Citation2010) develops a Foucauldian approach to theorizing territory within political geography. He traces the genealogy of territory through the rise of technologies for mapping, ordering, measuring, and demarcating land and terrain. In Elden's analysis, territory is thus construed as ‘a rendering of the emergent concept of “space” as a political category: owned, distributed, mapped, calculated, bordered, and controlled’ (Citation2010, p. 15; see also Citation2007). Rather than a wider conceptual category, then, Elden argues for seeing territory as a specific historical construction, produced largely through the national state project of measuring land and exerting state power over terrain and therefore primarily equivalent to the space of national sovereign biopolitical power for most of its existence. Here, once again, territory, though not necessarily national, is definitively entangled with the bounding of land and terrain.

Buxbaum writes that while the US approach

relies heavily on private international law concepts in defining the scope of prescriptive jurisdiction, German courts and commentators view the problem through two very different lenses—public international law and international enforcement law. As a result, claims of territoriality and extraterritoriality resonate differently in the two systems (Citation2009, p. 636).

In Territory, Authority, Rights (2008) I first used this notion in dealing with medieval traders and craftsmen who through their inter-city traveling had ‘produced a specific type of spatiality. This spatiality wormed its way into territories encased in multiple, formal, nonurban jurisdictions—feudal, ecclesiastical, and imperial’ (Sassen, Citation2008, p. 29).

I have developed this at length in ‘Bordering capabilities versus borders: implications for national borders’ (Sassen, Citation2009). See also, Paasi (Citation2012) for a discussion of the literature developing the concept of the border beyond the traditional line-centric view.

We can detect this in international legal cases of the last two decades where such cases rupture the dominant geopolitical system. For instance, legal scholars as diverse as Karen Knop, Susan B. Coutin, and Peter J. Spiro have written about the ambiguities in certain aspects of international law that become visible when the law is applied to cases involving a ‘non-typical subject’, such as women in international claims or immigrants in citizenship-related cases. See, e.g. Knop (Citation2000, Citation2002), Spiro (Citation2008), Coutin (Citation2000). For a discussion of such ambiguities in the social science literature, see Beck (Citation2000), Jessop (Citation1999), Taylor (Citation2000).

For a discussion of the broad consequences on law and regulation caused by the digitization of a growing range of domains, see Avgerou et al. (Citation2007), Benkler (Citation2006), Denning (Citation1999), Goldsmith and Wu (Citation2006), Rantanen (Citation2005), Latham and Sassen (Citation2005), Sassen (Citation2008, Chapter 7).

The principle of non-refoulement forbids states under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees from returning ‘legitimate’ refugees to the state from which they have fled.

To date, in addition to several ongoing preliminary examinations, two ICC Prosecutor investigations have been launched on the basis of propio motu: (1) On 31 March 2010 an investigation was initiated into six Kenyan government officials for their alleged involvement in crimes against humanity committed between June 2005 and November 2009; and (2) on 3 May 2011, an investigation was initiated into crimes against humanity allegedly committed by Laurent Gbagbo since November 2010 in Côte d'Ivoire.

This occurred, for example, when the UN Security Council referred the situation in Darfur, Sudan—a non-State Party to the Rome Statute—to the ICC resulting in charges being brought against, and an arrest warrant issued for, then Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir along with six other high-ranking Sudanese officials. The controversy surrounding this case—notably the first time an arrest warrant was issued by the court for an acting head of State, an arrest opposed by many governments in the African Union—highlighted a critical question for the court over where, as Eric Blumenson puts it, ‘legitimate moral diversity ends and universal moral imperatives begin’ (Citation2006, p. 871).

This section draws on my 2008 article ‘Neither global […] rights’, published in Ethics and Global Politics 1(1–2), 61–79.

REFERENCES

- Agnew , J. 1994 . The territorial trap: the geographical assumption of international relations theory . Review of International Political Economy , 1 ( 1 ) : 53 – 80 . (doi:10.1080/09692299408434268)

- Agnew , J. 2005 . Sovereignty regimes: territoriality and state authority in contemporary world politics . Annals of the Association of American Geographers , 95 ( 2 ) : 437 – 461 . (doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00468.x)

- Aman , A. C. Jr. 1995 . A global perspective on current regulatory reforms: rejection, relocation or reinvention? . Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies , 2 ( 2 ) : 429 – 464 .

- Anderson , J. 1996 . The shifting stage of politics: new medieval and postmodern territorialities? . Environment and Planning D: Society and Space , 14 ( 2 ) : 133 – 153 . (doi:10.1068/d140133)

- Avgerou , C. , Mansell , R. , Quah , D. and Silverston , R. 2007 . Oxford Handbook on Information and Communication Technologies , Edited by: Avgerou , C. , Mansell , R. , Quah , D. and Silverston , R. Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- AVSI and UNHCR . 2009 . A Time Between: Moving on from Internal Displacement in Northern Uganda , Geneva : AVSI and UNHCR .

- Bartlett, A. (2007). The city and the self: the emergence of new political subjects in London, in Sassen S. (Ed.) Deciphering the Global: Its Spaces, Scales and Subjects, 221–243. Routledge, New York and London.

- Beck U. (2000) What Is Globalization? P. Camiller (Trans). Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Benkler , Y. 2006 . The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom , New Haven , CT : Yale University Press .

- Berman , P. S. 2002 . The globalization of jurisdiction . University of Pennsylvania Law Review , 151 ( 2 ) : 311 – 545 . (doi:10.2307/3312952)

- Blumenson , E. 2006 . The challenge of a global standard of justice: peace, pluralism, and punishment at the International Criminal Court . The Columbia Journal of Transnational Law , 44 ( 3 ) : 801 – 874 .

- Brenner , N. 2004 . New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood , Oxford : Oxford University Press .

- Brenner , N. and Elden , S. 2009 . Henri Lefebvre on state, space, territory . International Political Sociology , 3 ( 4 ) : 353 – 377 . (doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2009.00081.x)

- Brighenti , A. M. 2010 . Lines, barred lines. Movement, territory and the law . International Journal of Law in Context , 6 ( 3 ) : 217 – 227 . (doi:10.1017/S1744552310000121)

- Brownlie , I. 2008 . Principles of Public International Law , 7 , Oxford : Open University Press .

- Buxbaum , H. 2009 . Territory, territoriality and the resolution of jurisdictional conflict . American Journal of Comparative Law , 57 ( 2 ) : 631 – 676 . (doi:10.5131/ajcl.2008.0018)

- Buxbaum H. (2010) National jurisdiction and global business networks, Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 17(1), 165–181.

- Cerny , P. G. 1997 . Paradoxes of the competition state: the dynamics of political globalization . Government and Opposition , 32 ( 2 ) : 251 – 274 . (doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.1997.tb00161.x)

- Cerny, P. G. (2000). Public Goods, States and Governance in a Globalizing World. Routledge, London.

- Coutin , S. B. 2000 . Denationalization, inclusion, and exclusion: negotiating the boundaries of belonging . Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies , 7 ( 2 ) : 585 – 593 .

- Cutler , A. C. 1997 . Artifice, ideology, and paradox: the public/private distinction in international law . Review of International Political Economy , 4 ( 2 ) : 261 – 285 . (doi:10.1080/096922997347788)

- Cutler , A. C. 2001 . Globalization, the rule of law, and the modern law merchant: medieval or law capitalist associations? . Constellations , 8 ( 4 ) : 408 – 502 . (doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00254)

- Cutler , A. C. , Haufler , V. and Porter , T. 1999 . Private Authority and International Affairs , Edited by: Cutler , A. C. , Haufler , V. and Porter , T. Sarasota Springs : State University of New York Press .

- Cutler , C. and Gill , S. 2013 . The New Constitutionalism and the Future of Global Governance , Edited by: Cutler , C. and Gill , S. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press .

- Denning , D. E. 1999 . Information Warfare and Security , Boston , MA : Addison-Wesley Professional .

- Elden , S. 2007 . Governmentality, calculation, territory . Environment and Planning D: Society and Space , 25 ( 3 ) : 562 – 580 . (doi:10.1068/d428t)

- Elden , S. 2010 . Land, terrain, territory . Progress in Human Geography , 34 ( 6 ) : 799 – 817 . (doi:10.1177/0309132510362603)

- Ford , R. T. 1999 . Law's territory (a history of jurisdiction) . Michigan Law Review , 97 ( 4 ) : 843 – 930 . (doi:10.2307/1290376)

- Fredriksen A. (2012) Making Humanitarian Action Global: Coordinating Crisis Response Through the Cluster Approach. Doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, Department of Sociology.

- Gill , S. 1996 . “ Globalization, democratization, and the politics of indifference ” . In Globalization: Critical Reflections , Edited by: Mittelman , J. H. 205 – 228 . Boulder , CO : Lynne Reiner .