ABSTRACT

This article offers a new approach to the analysis of spatial hierarchies and selectivity within national politics. These hierarchies and related state spatial restructurings are approached by analysing spatial imaginaries of the political elites in Finland. This study places these present-day imaginaries and hierarchies in their historical context and analyses the qualitative shifts in Finnish spatial hierarchization. The paper illustrates how the institutionalized hierarchies of the 1960s and 1970s were used as a tool in the emerging Fordist welfare state, and how the hierarchies of today are built on a more competitively oriented basis. The current spatial imaginaries and hierarchies are approached through an extensive suite of elite interviews. These spatial hierarchies are revealing of the existing ways of reasoning and follow the more general spatial and economic rationalities. This paper argues that as the institutional status of the earlier spatial hierarchy has waned and been replaced with network-based spatial systems, hierarchies also exist, however, within the network-based spatial imaginaries and their associated policy practices. The new spatial hierarchies do not have institutional status, but their role in processes of state spatial restructuring is nevertheless important.

INTRODUCTION

The nature of state spatial restructuring and rescaling has been the focus of significant academic interest for some time (e.g., Angelo, Citation2017; Brenner, Citation2000, Citation2003a, Citation2003b; D’Albergo & Lefèvre, Citation2018; Fricke & Gualini, Citation2018; Henderson, Citation2019; Jessop, Citation2003; Keating, Citation1997; Marston, Citation2000; Mulligan, Citation2013; Schou & Hjeholt, Citation2019). These spatial transformations can be seen as actualizations of the prevailing state spatial strategies. Recently, these transformations have been associated with, for example, competitiveness-based urbanization and its global appearance (e.g., Brenner, Citation2003b; Brenner & Schmid, Citation2017). Luukkonen and Sirviö (Citation2019) witness how certain city-regional, or even metropolitan (Sirviö & Luukkonen Citation2020) imaginaries prevail in the current Finnish political discourse. Similar developments can also be seen in other European national contexts. For example, Gruber et al. (Citation2019) note how the previous policy emphasis on territorial cohesion in national politics has been replaced by the state’s withdrawal from the regions and refocusing on support for growing city-regions in Austria and Sweden. This reflects a relatively recent development in the state spatial transformation process that has occurred across various temporal phases (e.g., Moisio, Citation2012) mirroring the then prevailing economic and spatial rationalities. These phases of restructuring have reflected, for example, the emergence of Fordist–Keynesian spatiality and a gradual shift to post-Fordist systems of production and associated spatiality (e.g., Jessop, Citation1996, Citation2005).

Previously we have witnessed, for example, phases with a more regional and dispersed take on state spatial relations which have then been replaced by more centralized and network-oriented spatial systems. The currently prevailing ‘metropolitanization’ tendencies and institutional reforms are explained as ‘expressions of ongoing processes of state rescaling through which competitiveness is being promoted at a regional scale’ (Brenner, Citation2003b, p. 16). That is, the prevailing spatial imaginaries and spatial political processes prioritize endogenous regional growth and global competition. Regional economies, mostly major urban regions, are seen as national tokens in geoeconomic power plays (Jonas & Moisio, Citation2018). Moreover, these spatial restructurings go hand in hand with what Moisio (Citation2018) terms ‘knowledge-based economisation’, a geopolitical process in which territories are transformed by knowledge-intensive capitalism.

This article addresses the temporally evolving concepts of spatial hierarchies and spatial selectivity by focusing on spatial political imaginaries in two time periods in Finland. It traces the transformations from more hierarchical towards more network-oriented spatial imaginaries and analyses the dynamism of Finnish state spatial transformation and different imaginaries. Ahlqvist and Moisio (Citation2014) witness how Finnish regional political authorities promote network-based models of governance especially when it comes to transformation of the capital city-region and its global connectivity. Similarly, Granqvist et al. (Citation2019) have analysed the network-oriented or polycentric spatial imaginaries and their performativity in the context of the Helsinki City Plan. The emphasis of network-based imaginaries is fuelled by both spatial characteristics of global economy (Moisio, Citation2018; Moisio & Rossi, Citation2020), and European integration (Luukkonen, Citation2011). On the other hand, for example, Mattila et al. (Citation2020) have noted that so-called ‘places that don’t matter’ also exist in Finland and the subsequent antagonistic attitudes are relevant when it comes to administrative and planning practices. However, rather than analysing the changing imaginaries in Finnish spatial planning practices over the past decades, this article sheds a light on the dynamics of state spatial transformation through planning documents and elite interviews. As Zimmerbauer and Paasi (Citation2020) have noted, the old/hard and new/soft spaces become increasingly entangled and similar; this article will also not argue that the network-based imaginaries would simply replace hierarchically oriented imaginaries, but that hierarchies and networks become entangled.

The historical context is created by analysing several planning documents and related publications. The present-day imaginaries are approached through extensive elite interviews. The timeframe for the comparison utilizes the above-mentioned, more general societal transformation approach that has been termed, for instance by Jessop (Citation2005, Citation1996), a shift from Fordist to post-Fordist state spatiality, from Fordism to knowledge-based economization (e.g., Moisio, Citation2018), from managerialism to entrepreneurialism (Harvey, Citation1989) or from spatial Keynesianism to neoliberalism. The aim of this article is not to extensively engage with the literatures on these spatio-political shifts, but to reveal the composition of the concomitant transformations in the spatial hierarchies. Here a spatial hierarchy refers to the various processes of categorization, ordering and selectivity of places produced through spatial imaginaries. It does not refer to any form of multilevel governance structure, but rather to a variety of rationalizations of why some places matter more than the others (cf. Rodriguez-Pose, Citation2018; Sykes Citation2018) considering, for example, regional development policies.

The qualitative shift of spatial hierarchies in national politics is approached here by focusing on the imaginaries of the state space and their performativity. That is, this article looks at the spatial imaginaries within the national political debates, mirrored by the prevailing economic and spatial rationalities, and analyses the hierarchies these imaginaries produce. The aim is to reveal the qualitative shift in the spatial hierarchies while understanding that the above-mentioned wider transformations occur in the background. The purpose is not, however, to engage with the theoretical literatures on the essence of spatial imaginaries. Rather, they are utilized as a framework through which the essence of hierarchization is revealed. More specifically, the article approaches the peculiar instances of spatial selectivity (Jones, Citation1995) embedded within these rationalities and imaginaries. In this way, it also offers a new insight to the study of the shift from Fordist–Keynesian spatiality to post-Fordism (and beyond to late post-Fordism).

Through historical contextualization, current spatial hierarchies and the qualitative shift in the rationalities that build them at the level of imaginaries are illuminated. That is, the article shows how the spatial hierarchy that was in place during the 1960s and 1970s in Finland has been transformed into the present hierarchy. The earlier emphasis on spatial equity has waned, and the role of cities and central places is now rather different than before. The historical spatial hierarchy in Finland was built on a quantitative basis with the aim of creating regional units of production. Now these hierarchies are instead built on the basis of more qualitatively interpreted aspects, such as perceived competitiveness. The aim here, then, is to determine and analyse this very transition in the qualities of hierarchical thinking and argumentation within spatial politics.

Moreover, light is also shone on the roles that different instances of hierarchization have in state spatial restructuring. In other words, the article examines how the concept of a spatial hierarchy has various meanings in producing new state spaces and how these constantly recreated imaginaries and knowledge production processes are actualized in the spatial strategies of the state. As such, it examines the performativity and mobilization (Boudreau, Citation2007) of spatial imaginaries, and how the spatial hierarchies they produce are manifest in political processes and state spatial restructuring in the form of rescaling and reterritorialization.

Therefore, these spatial hierarchies are here addressed as both expressions of prevailing spatial economic rationalities and as tools utilized in regional policies justifying rescaling and spatial restructuring. Moreover, it is argued here that these hierarchies, be they institutionalized or not, have real effect in determining the ‘winner and loser regions’ (Storper, Citation2013) in different times. By analysing the currently prevailing imaginaries and hierarchizations in a historical context, it is depicted what kind of role prevailing spatial hierarchizations play in state spatial strategies. By means of this contextualization, the spatial imaginaries of state space and the embedded hierarchies are depicted as evolutionary processes behind transforming state conditions.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section explains the theoretical approach used and offers a brief theoretical discussion of the issue of spatial imaginaries and their performativity. The third section introduces the materials and methods used. The fourth section develops a historical context for spatial hierarchies through a reading of the normative and academic writings on the Finnish tradition of the hierarchical modelling of central places. The fifth section analyses a set of interviews and offers a visualization of the spatial hierarchies present in Finnish spatio-political discourse. In this way, it is revealed how present-day networked spatial systems are inherently hierarchically ordered. The final section includes a short discussion and some conclusions.

HIERARCHIES AS PERFORMATIVE SPATIAL IMAGINARIES

In this study, the concepts of a spatial imaginary and a spatial hierarchy are utilized. The study focuses on the major imaginaries of the state space and the performativity of these imaginaries in different periods. Collective and contested spatial imaginaries are approached and analysed to reveal their embedded hierarchical ways of thinking. Moreover, these imaginaries have explicitly performative aspects; they form spatial hierarchies and legitimize political practices.

Imaginaries are here understood as ‘meaning systems’ (Jessop, Citation2012a), discursively constituted understandings that shape lived experience and the frames within which the world is comprehended.

These socially produced individual and/or collective knowledges simplify and make understandable the circumstance of decisions and political action. These imaginaries allow individuals and organizations to relate to these circumstances and make decisions and strategies in a complex environment (Jessop, Citation2012a) by shaping the field of action through forming selectivities, depoliticizing some aspects into a realm of necessity or irrelevance. Moreover, Davoudi (Citation2018) writes that spatial imaginaries, as taken-for-granted understandings of spatiality, enable and legitimate spatial practices. Spatial imaginaries are produced through political struggles and are ‘infused by relations of power in which contestation and resistance are ever-present’ (p. 101). As Jessop (Citation2012a, p. 12) notes, even as imaginaries are collectively produced, there is no equality when it comes to these forms of meaning-making.

Sharp (Citation2009, pp. 11–22), writing on spatial imaginaries, notes that they have a connection to ‘otherings’, a practice Watkins (Citation2015) sees as demarcating boundaries of ‘inside’ versus ‘outside’, or as hierarchical categorizations (Sharp, Citation2009, p. 14). Watkins (Citation2015, p. 511) also illustrates how the naturalization of these imaginaries and otherings facilitates their treatment as true or common knowledge. As such, spatial hierarchies are here considered as an example of such categorizations. In this sense, competing and contradictory spatial hierarchies are approached through spatial imaginaries and by focusing on the sedimented or naturalized manifestations of spatial imaginaries within the argumentation of the political elite. In other words, the analysis of these imaginaries reveals the different spatial hierarchizations in play. Specific attention is paid in this article on how some imaginaries have become sedimented (Jessop, Citation2010) as common knowledge or have gained hegemonic status in structuring the hierarchies. These hierarchizations thus reveal what is at any given time valued (or not valued) as essential, necessary or rational, illuminating the rationalizations behind spatial selectivities.

By searching for these spatial hierarchies, the performative aspects of imaginaries (e.g., Watkins, Citation2015) are brought into focus. Spatial imaginaries have inherently normative functions (Jessop, Citation2012b). The operationalization of imaginaries in the form of hierarchies effect the policymaking processes, or are themselves affected by these same processes while also shaping the restructuring of state spaces. That is, as Jessop (Citation2012a, p. 9) argues, ‘when an imaginary is operationalized and institutionalized, it transforms and naturalizes the included elements as parts of a specific, instituted economy’. As Crawford (Citation2018) notes, imaginaries (and in this case, the spatial hierarchies they produce) are utilized as tools in political processes through which different political agendas are performed, rationalized and mobilized. According to Jessop (Citation2012b, p. 17), imaginaries are selective and normative mappings which ‘help to construct the reality that they purport to map’. Accordingly, this study reveals how the spatial hierarchies help to produce and reproduce themselves.

Therefore, by the concept of spatial hierarchy, it is referred to the common understandings and depoliticized notions of a hierarchy between places that is neither officially established nor legally constituted but rather, arranged around the imaginaries and perceptions of space. The spatial hierarchy is formed from the sedimented understandings and renderings of the state territory according to the socially constructed and hegemonic imaginaries of each period. This paper argues that these hierarchies are formed based on different valuations of, for example, regional competitiveness and the depoliticized qualities of spaces to meet the more general imaginaries of ‘a proper state space’.

Such a spatial hierarchy is constructed from various elements of place-specific (and economic) imaginaries, in which some places are seen as ‘mattering more’ than others (cf. Rodriguez-Pose, Citation2018). This kind of a spatial hierarchy might not surface in political narratives until needed; the spatial selectivity in, for example, regional development builds on the existing imaginaries of regional characteristics and case-by-case renderings of the economic circumstance. That is, some regions are perceived as being, for example, more competitive or innovative than others and, as such, certain policies are seen as rational and justified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The spatial hierarchies are approached in this paper through historical contextualization, and then by analysing the current spatial imaginaries through extensive interviews. The historical context and the empirical material are drawn from spatial imaginaries and hierarchizations in two distinct political periods in Finland. Moisio (Citation2012) has depicted how the spatial relations of the state of Finland have progressed through certain phases in the 20th century. This clear definition of the phases of Finnish state spatial restructurings offers a proper framework for this analysis and makes it possible to draw more general conclusions.

The historical context is produced by rereading the hierarchization of the places performed in Finland during the 1960s to early 1980s. During this period, the material elements of the Fordist state were produced while the spatial imaginaries of the time emphasized dispersed, or decentralized, models of regional development with the aim of creating conditions of growth throughout the state territory. This contextualization enables one to perform an analysis of the qualitative shifts within practices of hierarchization coinciding with the transition from Fordist to (late) post-Fordist spatiality and makes it possible to thoroughly analyse present-day conditions. This historical system of spatial hierarchies is approached through a series of planning documents and academic publications in which this type of modelling was created, interpreted and utilized. These publications lay down and explain the fundaments and functions of this spatial modelling approach and offer some background information on how and why it was created. With the help of some more recent studies, the political and social circumstances, reasoning and imaginaries that lie behind this approach to spatial hierarchy are interpreted.

The current spatial hierarchies have not found their way onto planners’ desks in the form of normative schemes in a similar manner as before. Current hierarchies are not institutionalized nor are they openly modelled. Existing planning documents on various levels are contradictory and do not take a strong stance on hierarchical structures. On the one hand, for example, the MAL-agreements (agreements on land use, housing and transportation; see more below), which the state of Finland agrees to with the major cities, speaks for clear-cut hierarchization. On the other, some of the recent governmental documents (e.g., Government of Finland, Citation2019; Ministry of Finance, Citation2020) rhetorically emphasize the equality of state spaces. In other words, the status of the spatial hierarchies is rather different from before.

Contrary to the earlier modelling of central places, current hierarchies are produced within political and social processes through the sedimentation of depoliticized knowledge (Jessop, Citation2010). However, the hierarchical models of the 1960s and 1970s also represent a constellation of spatial imaginaries, strategic selectivity and political contestation. As such, these two empirical material sets enable a reasonably concise process of contextualization and analysis to take place, even though they are produced somewhat differently.

In order to grasp these more subtle processes of hierarchization in present day politics, 36 semi-structured interviews were conducted with various Finnish political actors between May and October 2019. The interviewees are well placed and represent various important organizations considering the national political narratives on urbanization. The interviewees represent:

Various organizations within the state apparatus, such as the chiefs of staffs and key officials from relevant ministries (ministries of Economy and Employment, Finance, Environment, Education and Culture, and Transport and Communications) and other state branches (e.g., The Environmental Institute and the regional Centres of Economic Development, Transport and the Environment).

The ranking members of the Finnish parliament from all major political parties.

Mayors of various cities, other municipalities and regions.

Key figures in Finnish civil society, organizations (e.g., the Family Federation of Finland), interest groups (e.g., labour market and employers’ organizations) and major private companies (e.g., banks, developers and consultancies).

These interviewees, it can be argued, have an influential position in Finnish spatial–political discourses. The interviewees were chosen in such a way that the different sides and standpoints in the ongoing political discussions were represented. Through these extensive interviews, it is possible to depict the spatial imaginaries that prevail among Finnish political elites. This may seem like a heterogeneous group of interviewees, but it is precisely the kind of group that enables an approach to the political interests, imaginaries and strategic selectivities to be made. The state as an arena of conflicting interests is always heterogenous and through a wide selection of interviewees a general image of prevailing hierarchies is produced.

During the interviews, various topics under the key thematic of urbanization and the political processes surrounding it were discussed. The themes explored in these interviews spanned a range from general to regionally specific questions on urbanization in Finland, economic and environmental questions as well as future predictions. In particular, a set of questions were produced concerning the metropolitan regions of Finland. The ways in which the specific spatial imaginaries are articulated by the interviewees were traced. In the focus of this analysis were the supposed interactions of the places, their characteristics, their supposed roles in national political processes and of how their roles are referred to in relation to the role of the state vis-à-vis the cities and regions. That is, how these elite interviewees imagine the various places and regions, and what kinds of figurative hierarchies and other such linkages are imagined here between cities and regions.

The empirical material was analysed by utilizing the concept of an imaginary as a tool in identifying wider spatial ways of thinking. In other words, the spatial imaginaries are used to isolate remarks on spatial hierarchies. Through the concept of an imaginary, it is possible to analyse different spatial logics and the rationalizations of these spatial hierarchies. The spatial imaginaries are here seen both as producing the hierarchies, but also as guiding political processes to sustain and acknowledge these hierarchies. These spatial hierarchies become understandable and informative when analysed in their historical context. Through this contextual analysis, arguments are deployed concerning the qualitative shift in the hierarchization of the state spaces.

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT: HIERARCHIES OF CENTRAL PLACES AND THEIR HINTERLANDS

Moisio (Citation2012) depicts the period from the 1960s to the early 1980s in Finnish state history as that of the dispersed welfare state (hajautettu hyvinvointivaltio). The plans and publications of this period (e.g., The National Planning Office, Citation1967) give away the somewhat common and depoliticized imaginary on the favourability of more spatially even and equalized development conditions. The key regional focus of the state was defined as ensuring regional welfare services and conditions for growth across the state territory. The hierarchization was utilized to ensure the necessary building blocks for the emerging Fordist welfare state. The institutionalization of the hierarchy aimed at securing the conditions for capitalist production throughout the state territory. As such, the concept of a spatial hierarchy has played a major role in Finnish spatial politics for decades.

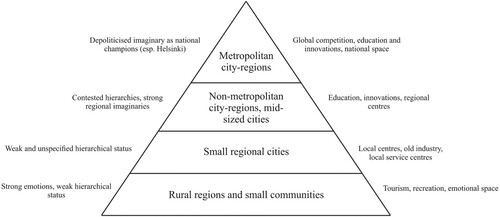

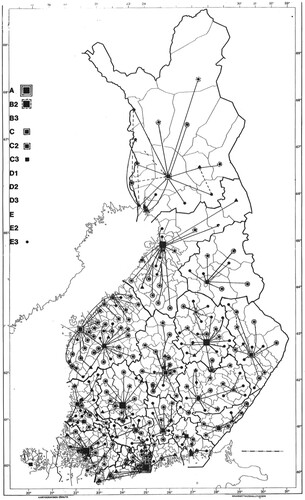

These imaginaries were operationalized by utilizing certain normative categorizations (e.g., available services) and hierarchizations in respect of places and regions, mostly of the central places. Despite this seemingly totalizing approach to modelling the state spaces, the aim was not to homogenize the state territory nor to create a monocentric hierarchical governance system. Rather, it was to model and secure regional units of production, labour and welfare services. exemplifies how the national hierarchical models were often compiled from individual regional hierarchical modelling, and how even smaller municipal centres were categorized and placed in the lower levels of the hierarchy (for detail, see The National Planning Office, Citation1976).

Figure 1. The network of central places, 1973.

Source: The National Planning Office (Citation1976).

The Finnish central place system tradition is originally based on the enumerative classification method created by Palomäki (Citation1963). It was utilized in various instances, perhaps most importantly by The National Planning Office in compiling a study entitled The Finnish System of Central Places and their Hinterlands (Citation1967). The representation and illustration of the hierarchy in this modelling leaned on such theorists as Christaller (Citation1933, Citation1955), Lösch (Citation1954) and Isard (Citation1956). The rationalities and imaginaries favouring equalizing regional policies were based on theories by Myrdal (Citation1957), Perroux (Citation1950) and Hirschman (Citation1961) and on so-called Unbalanced Growth Theory of regional economic development (Honkanen, Citation2016; Tervo, Citation1985).

The question of major cities and their growth was approached rather differently at that time than it is now. Helsinki, being by far the biggest city-region, was usually (e.g., The National Planning Office, Citation1976) located at the top of all classifications in a category on its own. As a national capital, it was depicted as serving the whole state territory in terms of certain state-level services. The fast growth of Helsinki was, however, deemed problematic (Forsberg et al., Citation1963, p. 152) for both Helsinki itself and the regions losing population to it. The imaginaries in which the regional scope of the state was strongly emphasized can be contrasted with the fast urbanization from the 1950s onwards (Forsberg et al., Citation1963, p. 151). Thus, the prevailing regional imaginaries were institutionalized and operationalized by bringing this modelling approach onto planners’ drawing boards. The National Planning Office and the so-called regional planning unions utilized these models of the central place hierarchies in regional planning until the 1980s (Mikkonen, Citation2009, p. 28; see also The National Planning Office, Citation1976).

Behind this hierarchical territory work lays a rather straightforward effort to create regionally even units of Fordist production, or a dispersed welfare state (Moisio, Citation2012). The central place modelling and the hierarchical planning worked in parallel with other regional development policies, such as the industrializing regional policy and growth centre policy (Hautamäki et al., Citation1969; Tervo, Citation1985). These political processes aimed at reducing regional developmental disparities by creating industrial production and creating support for growing centres throughout the state territory (Honkanen, Citation2016). As such, the hierarchization of central places and their hinterlands is a remarkable representation of a clear-cut attempt at spatial restructuring. It was an attempt to construe the spatially dispersed capitalist production and welfare state relying on the institutionalized understanding of regional characteristics. The connection between the imaginaries, hierarchical understanding and concrete territory work was rather obvious. The rationalization of hierarchies was technical and the hierarchization served an outspoken political purpose.

The network of central places was constantly remodelled utilizing different sets of parameters. There were even attempts to model an ‘optimal’ network of centres (Palomäki & Mikkonen, Citation1971) which speaks for the clear-cut effort to restructure the state spaces. This gives away the strong regional imaginaries in Finnish politics. The political aspirations to determine the key aspects of the emerging Finnish welfare state manifested in this normative regional modelling. The economic growth of major cities and rapid urbanization was met with a strong political advocacy for not only supporting, but also actively developing, Finland through growth centres all around the state territory.

Honkanen (Citation2016) notes how different regions and municipalities eventually started to compete in service provision in order to influence their position in the modelled hierarchy and thus elevate their position also in terms of regional and national planning (see also Katajamäki, Citation1977). Honkanen (Citation2016) continues further by noting how the role of the hierarchical modelling of services eventually become overemphasized in planning, leading municipalities to acquire more services than they could finance and support in order to gain more central attention in relation to regional planning. Eventually, hierarchical modelling, however, came to be viewed as outdated as globalization and Europeanization hindered the premises of such a hierarchical spatial structure, where the connections between the central cities and the hinterlands began to atrophy and sever (Brenner, Citation2002; Mikkonen, Citation2009).

The following period, which Moisio (Citation2012) terms the period of ‘the dispersed competition state’, saw the structuration of urban networks, development corridors and other such models that favoured other kinds of spatial structures, and other means of structural modelling (Honkanen, Citation2016; Mikkonen, Citation2009). Despite losing importance, the central place models have undoubtedly, however, had an important role to play in creating the hierarchical regional development processes and the spatial hierarchy of places in Finland. Even as central place modelling ceased to retain policy relevance and, consequently, the whole tradition fizzled away during the early 1980s, its legacy is still visible in present-day spatial politics and spatial political practices. Current imaginaries and spatial hierarchies are nevertheless, however, constituted on very different qualifications basis than was previously the case.

CURRENT IMAGINARIES AND SPATIAL HIERARCHIES IN A NETWORKED SETTING

The current imaginaries in Finnish politics no longer have such an institutional status. The tradition of modelling the state space and its hierarchies has been replaced by more abstract depictions of city networks (Vartiainen, Citation1995; Vartiainen & Antikainen, Citation1999) and city-regions. Despite the networked orientation of the spatial systems, the spatial hierarchies still have a major role to play within them. The current spatial hierarchies are constructed within political and social processes, as individual and collective ‘mental maps’. They come to be seen as underlying assumptions rationalized by sedimented and hegemonic place-specific imaginaries. These spatial hierarchies are not, however, openly debated and political actors may even deny their very existence. As they have no official recognition, these more subtle hierarchizations have to be approached through interviewing the political actors concerned.

Current Finnish political narratives about the state space are diverse, but often circulate around the wider thematic of urbanization. Depoliticized understandings of urbanization, on the one hand, and politicized aspects of spatial governance, on the other, structure these political discussions. Indeed, several commonly acknowledged attributes and specific elements associated with certain regions were repeated ad nauseam in the interviews conducted for this study. That is, the depictions of rural regions and urban centres both reveal powerful and shared imaginaries.

The interviewees can be roughly demarcated into three groups according to how they depict these regions. One group (the ‘ruralists’) depict the rural regions most positively. In their argumentation, the essential nature of the rural countryside and small cities is brought forward and they are often, at least mildly, suspicious of the growth of the major cities. The ‘ruralists’ group is by far the smallest of the three. The second group provides rather contradictory descriptions: the ‘metropolitanists’ heavily politicize Finnish spatial traditions and spatial governance. They are most openly supportive of fast urbanization and depict the major cities as centres of innovation, growth and global competitiveness. The arguments of the last group are more varied. The depictions of these ‘centrists’ are, however, still usually more inclined towards the ‘metropolitanists’ than the ‘ruralists’. One representative of a state branch depicts his/her take on the regional hierarchy in the following manner:

The Finnish system [of regional development] is like a money-train, I have depicted it like this: You load the train full with money in HelsinkiFootnote1 and start moving north and take a spade which you use to throw money to the regions. When you go further north you have a bigger spade to throw the money out, and when you come to OuluFootnote2 you have to literally push the money out the door.

It is the group [metropolitan cities] we must be included in. Like come on, we have more than 200,000 inhabitants. It is impossible for me to think we could possibly be identified with the next level, with such cities as JyväskyläFootnote3 or KuopioFootnote4 or Kokkola.Footnote5 Well Kokkola is not even on that level but JoensuuFootnote6 is.

There is for example the group of six [that form four metropolitan regions], Helsinki, TampereFootnote7, TurkuFootnote8 and Oulu and yes, they are in their own category, and they have their own group. … Then we have the ‘gang’ of 20 (cities) that Vapaavuori [Mayor of Helsinki] has gathered together … different coalitions here and there … .

First, the imaginaries of the metropolitan regions among the interviewed political elites seem to be rather uniform. For example, these city-regions, especially the Helsinki region, are often associated with such elements as competitiveness, growth, economic fate of the nation, globalization and innovativeness. These depictions are often rather positive, and emphasize the importance of these spaces as a national question, as key national spaces. In other words, it is exactly the imaginaries of competitiveness and abstract global prestige that have become hegemonic elements in determining the special role of major-city regions in Finnish spatial hierarchies. Finland as a nation-state is often imagined through its capital and other major cities. As one representative of an interest group advocates:

we must understand from global (urban) branding and we must also dare to support, at the state level, Helsinki as a brand and to understand that these are not separate. Like, Copenhagen and Denmark have understood that (as a brand-image) they are the same … .

In other words, the selectivity is justified on the basis of some sort of a common cause. As the hegemonic imaginary depicts the major city-regions as the most competitive spaces and productive engines of the national territory, it is concluded that the growth of these regions must be protected as a national question. This imaginary provides a strong demarcating factor separating the metropolitan regions from the rest, as a national space where global competitiveness is performed. One representative of a civil society organization declares: ‘Merging the capital municipalities … in their interests and in the national interest it is that we could have a metropolitan region competing with Tallinn, St. Petersburg or Stockholm … .’ Second, the mid-sized cities and the major cities not included in the ‘metropolitan’ category can be listed separately. Many similar characteristics and attributes attributed to the ‘metropolitan city-regions’ can also be associated with these cities. They are depicted as innovative, productive, well connected while many of them are also listed as major centres of education. Attributes such as competitiveness and the importance of economic growth are, however, repeated over and over in the interviews. Interestingly, these depictions of competitiveness and economic growth are rather different compared to the metropolitan city-regions, and emphasize more regional and national questions. One manifestation of this difference demarcating the metropolitan regions from these other cities, among such factors as the job market sizes and the number of inhabitants, is that these mid-sized cities are not imagined as having such ‘growth-related problems and questions’ as the metropolitan ones. That is, many interviewees argue that due to the global competition and necessary growth, the metropolitan city-regions face a specific burden in a form of infrastructure investments on one hand and in a form of, for example, urban social problems on the other. As such, the smaller city regions are not entitled to make similar agreements on growth and investments with the state. This coincides with the familiar argument that the urbanization process is understood as an inevitable ‘megatrend’ that has to be controlled by the state.

As the status of the metropolitan city-regions is secured by existing policies, the other major cities are locked into a more strenuous competition over governmental attention. This manifests itself in infrastructure investments, education policies, regional development policies and other such processes in which the state government engages: the hierarchy between these cities is constantly shaped through competition. Importantly, three of these cities (Lahti,Footnote9 Jyväskylä and Kuopio) are in the process of being included in the metropolitan special infrastructure investment agreements (on the process and rationalization, see Vatilo, Citation2020). The possibility that these cities might be cherry-picked and thus be more tightly associated with the metropolitan cities, encourages interesting, almost violent, competitive political processes resurface.

Contrary to the national/global role of the metropolitan cities, the ‘role’ allocated to these mid-sized cities in political imaginaries is a territorial one. Quite often, these cities are depicted as being central places for wider spatial units and parts of the state territory larger than their immediate surroundings. The representatives of these cities in particular advocate for such policies in which the state level would ensure the ‘liveability’ of the whole state territory by promoting the growth of these regional centres. One mayor imagines thus: ‘We could have 10, or perhaps less, maybe eight growing cities that would diffuse vitality to their surroundings.’ Another interviewee had the same thought:

We could have maybe ten cities that grow and ensure vitality in the provinces. So, we shouldn’t talk about ensuring the habitability of all places in Finland, but rather that all regions should have one place that diffuses vitality and ensures healthy job markets … .

And then these regional cities, there could be one ‘living’ one in every province, their role could be to act as some kind of a network, to ensure that we get our hand on the regional resources and the tourism … to say so, diplomatically … .

The fourth and final clear category of places that has a distinct place in Finnish spatial imaginaries is the rural region. The imaginary of these places is, however, somewhat contested between the different interviewee groups, but the majority of respondents depict it as a troublesome space. The ‘rural question’ is heavily politicized in Finland. The ‘ruralists’ depict these regions as liveable, traditional and ‘real’, as centres of businesses such as tourism and as important regions in respect of raw material extraction as well as being essential in ensuring the availability of national emergency supplies. Nevertheless, the imaginaries of deprived, poor regions lacking education and knowledge, lacking innovativeness, and social ‘buzz’ continue to predominate rhetorically. The differing voices of the ‘ruralists’ do not seem to have much impact in these wider debates, and their arguments are disregarded by the other interviewees who depict the rural regions as a burden for the national economic processes. For example, one respondent imagines these regions in this way: ‘We have 300 municipalities and 290 of these are doing nothing without state support.’

Despite differing depictions and political stances, it is clear that the imaginative place of rural regions in the spatial hierarchy is rather clear: they are at the very bottom. While these spaces are sometimes depicted as having ‘nothing’ to give in terms of a hierarchy that is constructed on the basis of competitiveness and innovation, these rural regions are nevertheless described as a kind of emotional space by many of the interviewees. The economic and demographic crisis of these rural and ‘traditional’ settings comes to the fore in many interviews. Even the ‘ruralists’, for the most part, acknowledge and emphasize the economic hardships and other often repeated problemata associated with rural regions. Despite their common depiction as burdensome backwards regions, many interviewees emphasized their own rural or provincial backgrounds or family ties. Therefore, despite the negative characterizations and their position at the bottom of the imaginative spatial hierarchy, these spaces are still imagined as having a role to play in the political and social processes of Finland.

Even though the hierarchy of the central places model has not been used in regional planning for decades, some of its sentiments have nevertheless lived on in the spatial imaginaries of Finland. It seems that similar rationalizations for the need for a hierarchy are actually even gaining support in some political narratives. The new imaginary of a spatial hierarchy is, however, in essence, built on different grounds to the older model of central places.

The ideal of the central place hierarchy modelling, in which the upper levels served the lower levels through services, is now twisted in favour of the major cities: their role in serving the totality is emphasized more than before and they are portrayed as the national economic champions. The other regions are often described as having a smaller role in hosting some competitive enterprises, merely structuring service production and labour markets across the state territory, or outright as an economic burden. As noted above, most interviewees acknowledge competitiveness and, for example, education as important determinants of spatial hierarchies, but it is especially the representatives of private sector enterprises who are most emphatic in making these arguments.

Another major difference is the varying role of the lower hierarchical levels. In the modelling produced in 1960s and 1970s, the hierarchization aimed at creating regional spatial systems and classifications focused on determining the role of even the smallest village centres, but in the current narratives these are most often seen as having either a weak, or indeed, no role whatsoever, or are simply put in the most general categories. The material support for and building of the regionally dispersed welfare state has shifted to what could be termed the withdrawal of the state from (some) regions. The political focus in hierarchization has shifted from determining and ensuring equitable regional conditions to ensuring and fostering metropolitan exceptionalism. Moreover, the hierarchy is not produced by modelling services, but as a result of active advocacy; regional competition structures the hierarchization.

The rough illustration () of the spatial hierarchy of Finnish places and regions is only one possible way to demarcate these imaginaries. One might even rule out the concept of a hierarchy between these places and approach these merely as separate categories demarcated by their figurative roles in the ongoing political processes. The hierarchical illustration is, however, important in hinting at the fact that some places are imagined to matter more than others when it comes to issues such as national competitiveness. This hierarchical spatial understanding is used to justify some selective policies. The spatial hierarchies are not only a reflection of political processes, but have themselves an active role in shaping those processes.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study analyses the changing qualities of spatial hierarchies coinciding with the transitions from Fordist to post-Fordist and late post-Fordist spatiality through spatial imaginaries. Particular forms of spatial hierarchies are revealed through these imaginaries. These hierarchical understandings are analysed as indicators of wider political processes and rationalities. This paper argues that these spatial hierarchies are manifest in processes of state spatial restructuring. When analysed in their historical context, we witness how the concept of a hierarchy has a long tradition. The contextualized analysis of the rationalizations and justifications of these hierarchies are informative of strategic selectivity in national politics, state spatial transformations and of the trajectories of late post-Fordism. The performativity (cf. Davoudi, Citation2018; Jessop, Citation2012b; Watkins, Citation2015) of the spatial imaginaries becomes apparent in the formulation of these hierarchies and selectivities.

The qualitative shift in spatial hierarchizations has been analysed within the context of both present-day politics and historically, in Finland. The historical, openly modelled hierarchical systems of the Fordist period have been transformed into the more subtle and subjective understandings of today’s hierarchy. The meaning and purpose of the hierarchies, and thus their qualitative content has changed from the more regionally posited towards a more competitive orientation. This article has identified four categories of spaces in Finland with loose roles and functions in Finnish spatial system within the imaginaries of political elites. The metropolitan spaces are viewed as being the nationally competitive nodes into the global economy (cf. Sirviö & Luukkonen, Citation2020). The mid-sized cities are described as competitive regional centres locked into a competition over regional prestige, national hierarchical status and governmental resources. The small regional cities are problematized and seen as having a weaker regional role in the competitively oriented hierarchies. The rural regions are described as emotional and traditional spaces, but problematized and viewed as having only an occasionally supportive role in the Finnish national economy. These hierarchies are, moreover, ruthlessly utilized in political argumentation (cf. Crawford, Citation2018).

The earlier hierarchical spatial system was indeed constructed on hegemonic spatial imaginaries in which issues such as functionality of regional systems of production and equality of regions were emphasized. The present-day spatial hierarchies cursorily resemble the historical counterpart, but are built on rather different hegemonic understandings. Moreover, the imaginaries are now produced in different kinds of processes than before. Earlier, the state government and the regional planning offices were more exclusively in charge of describing, modelling and planning the spatial systems based on specific attributes. Now, the production of imaginaries and hierarchies is performed through more fuzzy, open-ended political processes that include myriad of different actors and interests. As a result, the political discourses over spatial policy-crafting are often heated and contradictory, but spatial competitiveness, education, city-regional growth and for example knowledge-intensive labour markets have sedimented as hegemonic aspects determining the present-day hierarchies.

Moreover, this article has revealed, that the figurative hierarcicity or ‘networkedness’ (e.g., Amin, Citation2004; Harrison Citation2010) of the spatial systems does not necessarily reveal much about how these state spaces are actually restructured. These mechanisms have to be approached more closely. It is here shown how the apparently hierarchical system in the Finland of the 1960s and 1970s was utilized to create a more regionally even spatial organization whereas strong hierarchical understandings, imaginaries and practices underlie the spatial networks of today.

Therefore, the mere organization of spatial systems does not indicate much about the condition of state spatial transformations. It is important, however, to also analyse the commonly held imaginaries and various practices (such as selectivity) to understand how the new state spaces are actually formed. From this point of view, the hierarchies underlying the supposedly unhierarchical urban/regional networks do not necessarily challenge the networked orientation of these spatial systems, but rather provide another context in which to analyse political processes. In the spatial networks, the competition between the nodes has a major effect in forming and sustaining the hierarchy. These new hierarchies become sedimented (Jessop, Citation2010) as the method of producing new state spaces.

The ‘hierarcicity’ of the urban networks help understanding how the late post-Fordist spatialities are produced. The spatial competition, as well as the different selectivities involved and acts pursuant of the ‘strategic interests’ of the state emphasize two notions. First, innovation and education have been brought to the fore as the major substance of and object of political processes. In the wider imaginaries, the proper state space is constructed of competitive nodes of knowledge (cf. Moisio, Citation2018). Second, an emphasis on the growth-related problems of major cities as a rationalization of selectivity reveals what kind of state spaces are produced, and how. The premises of urbanization are depoliticized in political narratives. It is treated as an inevitability, or necessity. In the political narratives, the government aims at facilitating this inevitability, by reforming the withering regions and removing obstacles from the growth of major cities in investment terms (e.g., the governmental agreements on land use, housing and transportation). Despite the apparent transparency of these aims, the political narratives frame these as reactive processes: By selective practices informed by spatial hierarchies, the government follows major trends and adapts to them. Therefore, the state is not framed as a (pro)active actor in shaping the spatial relations of the state. During the construction of the Fordist welfare state, the aim of the state was to ensure regional growth and maintain and support regional units of production while the late post-Fordist state is marked by a withdrawal of the state and a new emphasis on its ‘strategic interests’ in city-regions.

That is, while constructing the late post-Fordist, or knowledge-based society, these processes shape the division of ‘winner and loser regions’ (Storper, Citation2013). These new modes of spatial polarization become tangible through the spatial hierarchies and their rationalizations. This is informative when it comes to some of the recent partisan political developments. In this study, the thematic of the ‘left behind regions’ (e.g., Sykes, Citation2018) or spatial populism are not explored. The study, however, does reveal that the mechanisms such as hierarchization and selectivity are important when studying spatial populism and, for example, the question of the so-called ‘revenge of the regions’ (Rodriguez-Pose, Citation2018).

One additionally important feature this study highlights concerns the changing role of the state. The emphasis on ensuring the state’s regional presence through the hierarchical mapping of service centres has transformed into something different. Now the state’s regional role manifests itself in practices of selectivity and inviting bids from regions and regional networks on development initiatives. The peculiar characteristic of these political processes is that the selectivity based on spatial hierarchies is done openly and it has political legitimacy over party lines. In Finland, this is manifest in the practices termed regional partnerships (e.g., Urjankangas & Voutilainen, Citation2018). In these, the state makes agreements over regional policies and investments with an exclusive number of (major) cities. That is, the state is now somewhat imagined as being without spatial presence other than what is produced through these partnership agreements with regional actors. This reinforces the notion of (city-)regions as being used as tokens in a broader geopolitical competition by the state (cf. Jonas & Moisio, Citation2018).

This kind of hierarchical analysis is one way to approach the state spatial transformations and shift to late post-Fordism. This mechanism still needs more attention. The changing role of the state (e.g., in the form of the partnership mechanisms) is one possible avenue for further analysis. Moreover, the various forms of spatial (and economic) imaginaries must be analysed constantly. This study offers a glimpse into the constantly evolving and reconstructed imaginaries. As such, they only offer one short outlook on the processes of late post-Fordism. More attention is also required in terms of analysing how these competitiveness-oriented imaginaries are produced and sustained, but also on how they are challenged and resisted.

Lastly, a global Covid-19 pandemic broke out during the writing of this article. There is a growing list of publications on the perceived and anticipated effect the pandemic and related lockdowns, etc. will have for national regional development and related political processes. It is, however, premature to discuss what kind of effect the pandemic might have for the formulation of spatial hierarchies, or place-specific imaginaries. While the pandemic indeed has opened up a kind of general discourse on spatial systems, the implications of this discourse cannot be analysed in advance.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Uusimaa region, southern Finland, 650,000 inhabitants (1.2 million in the city-region). The Helsinki region also includes the cities of Espoo and Vantaa along with several smaller municipalities, and is often described as ‘the competitive engine’ and the metropolitan region of Finland.

2 North Ostrobothnia region, northern Finland, 210,000 inhabitants (240,000 in the city-region). One of the metropolitan city-regions that is entitled to make special investment agreements with the state of Finland on land use, housing and transportation.

3 Central Finland region, 140,000 inhabitants (180,000 in the city-region). The Jyväskylä city-region is in the process of being included in the special infrastructure investment agreements with the state of Finland, and thus figuratively to be included in the group of ‘metropolitan city-regions’.

4 Northern Savonia region, eastern Finland, 120,000 inhabitants (140,000 in the city-region). The Kuopio city-region is also in the process of being included in the special infrastructure investment agreements.

5 Central Ostrobothnia region, western Finland, 48,000 inhabitants. The central city of the smallest of Finnish regions.

6 North Karelia region, eastern Finland, 76,000 inhabitants.

7 Pirkanmaa region, west-central Finland, 240,000 inhabitants (330,000 in the city-region). One of the ‘metropolitan city-regions’. Tampere and Helsinki are often described as key nodes in the ‘Finnish growth corridor’.

8 Finland Proper region, south-western Finland, 193,000 inhabitants (330,000 in the city-region). Turku in turn completes what is named ‘The Finnish growth triangle’ along with Tampere and Helsinki.

9 Päijänne Tavastia region, southern Finland, 120,000 inhabitants (200,000 in the city-region). The Lahti region is also being considered to be included in the special infrastructure investment agreements and thus to be figuratively included in the group of ‘metropolitan city-regions’.

REFERENCES

- Ahlqvist, T., & Moisio, S. (2014). Neoliberalisation in a Nordic state: From cartel polity towards a corporate polity in Finland. New Political Economy, 19(1), 21–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2013.768608

- Amin, A. (2004). Regions unbound: Towards a new politics of place. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 86(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00152.x

- Angelo, H. (2017). From the city lens toward urbanisation as a way of seeing: Country/city binaries on an urbanising planet. Urban Studies, 54(1), 158–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016629312

- Boudreau, J. A. (2007). Making new political spaces: Mobilizing spatial imaginaries, instrumentalizing spatial practices, and strategically using spatial tools. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39(11), 2593–2611. https://doi.org/10.1068/a39228

- Brenner, N. (2000). The urban question: Reflections on Henri Lefebvre, urban theory and the politics of scale. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(2), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00234

- Brenner, N. (2002). Decoding the newest “metropolitan regionalism” in the USA: A critical overview. Cities, 19(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(01)00042-7

- Brenner, N. (2003a). Metropolitan institutional reform and the rescaling of state space in contemporary Western Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(4), 297–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764030104002

- Brenner, N. (2003b). Standortpolitik, state rescaling and the new metropolitan governance in Western Europe. The Planning Review, 39(152), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2003.10556830

- Brenner, N. (2004). New state spaces: Urban governance and the rescaling of statehood. Oxford University Press.

- Brenner, N., & Schmid, C. (2017). Planetary urbanization. In X. Ren & R. Keil (Eds.), The globalizing cities reader (pp. 479–482). Routledge.

- Christaller, W. (1933). Die zentralen orte in suddeutschland: Eine okonomisch-geographische untersuchung uber die gesetzmassigkeit der verbreitung und entwicklung der siedlungen mit stadtischen funktionen. Jena.

- Christaller, W. (1955). Contributions to a geography of the tourist trade [Beiträge zu einer Geographie des Fremdenverkehrs]. Erdkunde.

- Crawford, J. (2018). Constructing “the coast”: The power of spatial imaginaries. Town Planning Review, 89(3), 283–304. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2018.17

- D’Albergo, E., & Lefèvre, C. (2018). Constructing metropolitan scales: Economic, political and discursive determinants. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1459203

- Davoudi, S. (2018). Imagination and spatial imaginaries: A conceptual framework. Town Planning Review, 89(2), 97–124. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2018.7

- Forsberg, K.-E., Gustafsson, F., Hyvärinen, S., Saxen, Å, & Strömmer, A. (1963). Population trends in the Helsinki region and problems related to them [Helsingin seudun väestöllisestä kehityksestä ja siihen liittyvistä ongelmista]. Publication of the national planning office, series A:13.

- Fricke, C., & Gualini, E. (2018). Metropolitan regions as contested spaces: The discursive construction of metropolitan space in comparative perspective. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(2), 199–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1351888

- Government of Finland. (2019). Osallistava ja osaava suomi. pääministeri sanna marinin hallituksen ohjelma 10.12.2019. Valtioneuvoston julkaisuja 2019:31. [Participatory and competent Finland. The governmental program of Prime Minister Sanna Marin 10.12.2019.].

- Granqvist, K., Sarjamo, S., & Mäntysalo, R. (2019). Polycentricity as spatial imaginary: The case of Helsinki City plan. European Planning Studies, 27(4), 739–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1569596

- Gruber, E., Rauhut, D., & Humer, A. (2019). Territorial cohesion under pressure? welfare policy and planning responses in Austrian and Swedish peripheries. Papers in Regional Science, 98(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12344

- Haapala, M. (2011). Seutukaupungit aluerakenteessa-keskusverkkotutkimusten näkökulma. In H. Eskelinen (Ed.), Seutukaupungit aluerakenteessa ja sektoripolitiikassa (3rd ed., pp. 28–40). Sektoritutkimuksen neuvottelukunta.

- Harrison, J. (2010). Networks of connectivity, territorial fragmentation, uneven development: The new politics of city-regionalism. Political Geography, 29(1), 17–27.

- Harvey, D. (1989). From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: The transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 71(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

- Hautamäki, L., Siirilä, S., & Ylönen, R. (1969). Foundations for a growth centre policy in Finland [Tutkimus kasvukeskuspolitiikan perusteiksi Suomessa]. Helsingin yliopiston maantieteen laitoksen julkaisuja, B.

- Henderson, S. R. (2019). Framing regional scalecraft: Insights into local government advocacy. Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(3), 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1389660

- Hirschman, A. O. (1961). The strategy of economic development. Yale University Press.

- Honkanen, M. (2016). ALue, politiikka ja laki. analyysi eduskunnan aluepoliittisen lainsäädännön keskusteluista vuosina 1966, 1975, 1988 ja 1993. Unigrafia.

- Isard, W. (1956). Location and space-economy.

- Jessop, B. (1996). Post-Fordism and the state. In Comparative welfare systems (pp. 165–183). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jessop, B. (2003). The political economy of scale and the construction of cross-border micro-regions. In F. Söderbaum & T. Shaw (Eds.), Theories of new regionalism (pp. 179–196). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jessop, B. (2005). Fordism and post-Fordism: A critical reformulation. In A. J. Scott & M. Storper (Eds.), Pathways to industrialization and regional development (pp. 54–74). Routledge.

- Jessop, B. (2010). Cultural political economy and critical policy studies. Critical Policy Studies, 3(3–4), 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171003619741

- Jessop, B. (2012a). Cultural political economy, spatial imaginaries, regional economic dynamics (CPERC Working Paper, 2012/04). Lancaster University, Cultural Political Economy Research Centre.

- Jessop, B. (2012b). Economic and ecological crises: Green new deals and no-growth economies. Development, 55(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2011.104

- Jonas, A. E. G., & Moisio, S. (2018). City regionalism as geopolitical processes: A new framework for analysis. Progress in Human Geography, 42(3), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516679897

- Jones, M. R. (1995). Spatial selectivity of the state? The regulationist enigma and local struggles over economic governance. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 29(5), 831–864. https://doi.org/10.1068/a290831

- Katajamäki, H. (1977). Research on centres and hinterlands. Helsingin yliopiston maantieteen laitoksen opetusmonisteita. [Keskus- ja vaikutusaluetutkimus]. (13th ed.).

- Keating, M. (1997). The invention of regions: Political restructuring and territorial government in Western Europe. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 15(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1068/c150383

- Lösch, A. (1954). Economics of location.

- Luukkonen, J. (2011). The Europeanization of regional development: Local strategies and European spatial visions in Northern Finland. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 93(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0467.2011.00376.x

- Luukkonen, J., & Sirviö, H. (2019). The politics of depoliticization and the constitution of city-regionalism as a dominant spatial–political imaginary in Finland. Political Geography, 73, 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.05.004

- Marston, S. A. (2000). The social construction of scale. Progress in Human Geography, 24(2), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913200674086272

- Mattila, H., Purkarthofer, E., & Humer, A. (2020). Governing ‘places that don’t matter’: Agonistic spatial planning practices in Finnish peripheral regions. Territory, Politics, Governance, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1857824

- Mikkonen, K. (2009). Keskus-ja vaikutusaluetutkimus Suomessa. In S. Virkkala & R. Koski (Eds.), Yhteiskuntamaantieteen maailma (pp. 23–35). Vaasan Yliopiston julkaisuja.

- Ministry of Finance. (2020). Municipalities at a turning point? Information on the situation of municipalities in 2020 (13th ed.). Publications of the ministry of finance.

- Moisio, S. (2018). Geopolitics of the knowledge-based economy. Taylor & Francis.

- Moisio, S., & Rossi, U. (2020). The start-up state: Governing urbanised capitalism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(3), 532–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19879168

- Moisio, S. (2012). Valtio, alue, politiikka: Suomen tilasuhteiden sääntely toisesta maailmansodasta nykypäivään. Vastapaino.

- Mulligan, G. F. (2013). The future of non-metropolitan areas. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 5(2), 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12005

- Myrdal, G. (1957). Economic theory and under-developed regions. General Duckworth.

- The National Planning Office. (1967). The functional system of centers and areas in Finland [Suomen keskus- ja vaikutusaluejärjestelmä]. Publications of the national planning office series. Vol. A 19.

- The National Planning Office. (1976). National classification of centres 1973/1974 [Valtakunnallinen keskusten luokittelu 1973/1974]. Ministry of Interior Affairs.

- Palomäki, M. (1963). The functional centers and areas of South Bothnia, Finland. Vammalan Kirjapaino.

- Palomäki, M., & Mikkonen, K. (1971). An attempt to simulate an optimal network of central places in Finland [Optimaalisen keskusverkon simulointi Suomeen]. Valtakunnansuunnittelutoimiston julkaisusarja 1:25. Ministry of Interior Affairs.

- Perroux, F. (1950). Economic space: Theory and applications. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 64(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/1881960

- Rodriguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Schou, J., & Hjeholt, M. (2019). Digital state spaces: State rescaling and advanced digitalization. Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(4), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1532809

- Sharp, J. P. (2009). Geographies of postcolonialism: Spaces of power and representation. Sage.

- Sirviö, H., & Luukkonen, J. (2020). Metropolitanizing a Nordic state? City-regionalist imaginary and the restructuring of the state as a territorial political community in Finland. In S. Armondi & S. De Gregorio Hurtado (Eds.), Foregrounding urban agendas (pp. 211–227). Springer.

- Storper, M. (2013). Keys to the city: How economics, institutions, social interaction, and politics shape development. Princeton University Press.

- Sykes, O. (2018). Post-geography worlds, new dominions, left behind regions, and ‘other'places: Unpacking some spatial imaginaries of the UK's ‘Brexit’debate. Space and Polity, 22(2), 137–161.

- Tervo, H. (1985). Impact of regional policy on industrial growth and development [Aluepolitiikan vaikutukset teollisuuden kasvuun ja kehitykseen]. Ministry of Interior Affairs.

- Urjankangas, H.-M., & Voutilainen, O. (2018). Pioneering towards sustainable growth. Urban programme 2018–2022. Publications of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment 36/2018.

- Vartiainen, P. (1995). Kaupunkiverkko: Kuvausjärjestelmän kehittäminen kansallisiin ja kansainvälisiin tarpeisiin. Ministry of Environment.

- Vartiainen, P., & Antikainen, J. (1999). Kaupunkiverkkotutkimus 1998. Ministry of Interior.

- Vatilo, M. (2020). Extending the land use, housing and transportation contract procedure to new urban areas (1st ed.). Ympäristöministeriön julkaisuja. [MAL-sopimusmenettelyn laajentaminen uusille kaupunkiseuduille].

- Virkkala, S., Hirvonen, T., & Eskelinen, H. (2012). Seutukaupungit suomen aluerakenteessa ja kaupunkijärjestelmässä. In A. Hynynen (Ed.), Takaisin kartalle. suomalainen seutukaupunki (237th ed., pp. 17–29). ACTA.

- Watkins, J. (2015). Spatial imaginaries research in geography: Synergies, tensions, and new directions. Geography Compass, 9(9), 508–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12228

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2020). Hard work with soft spaces (and vice versa): Problematizing the transforming planning spaces. European Planning Studies, 28(4), 771–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1653827