ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the role of local political leadership in municipal policy responses to the arrival of forced migrants. Initially, I bring together insights from research on leadership, migration and crisis management to develop a conceptual framework for studying local political leadership in the reception of forced migrants. To this end, I adopt an interactionist perspective and define local political leadership as the product of the interaction between mayors and their leadership environment (institutional and societal context). Subsequently, I apply this conceptual framework to a qualitative comparative case study, using data from desk research and fieldwork in two Greek municipalities. The findings indicate that differences in local political leadership can lead to the development of very different municipal policy responses in the field of forced migrants’ reception. In particular, I argue that by exercising interactive and multilevel political leadership, mayors can increase their chances of advancing strategic policy objectives in migration governance, and by extension, strengthen the protection and fulfilment of migrants’ fundamental rights. Finally, in the light of the conceptual and empirical insights arising from this research, I emphasize the need to improve the dialogue between leadership and migration scholars, and suggest questions for future research.

INTRODUCTION

Recent research in migration policy and refugee studies has shed light on the role of local governments in developing policy responses to the arrival and settlement of forced migrants (Ambrosini et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Hinger et al., Citation2016).Footnote1 Some scholars have pinpointed cities’ welcoming and inclusive character, presenting them as sites that provide fertile ground for policy innovation in migration governance (Scholten et al., Citation2017). In contrast, others have emphasized the capacity of urban policy-making to effectively limit forced migrants’ access to services and hinder their integration prospects (Marchetti, Citation2020).

This article contributes to the aforementioned scholarly debates by zooming in on the capacity of local political leadership to facilitate the transformation of a locality into a ‘city of refuge’ for forced migrants. Research on migration policy has revealed a number of causal factors that can contribute to the development of more inclusive local policy responses, such as the strong presence of left-wing political parties, active civil society engagement, pro-immigrant volunteer initiatives and mobilization on behalf of migrants themselves (Bazurli, Citation2019; Hinger et al., Citation2016; Lambert & Swerts, Citation2019; Mayer, Citation2018). However, little research has explicitly addressed the role of mayors in relation to forced migrants’ reception (Betts et al., Citation2020; Terlouw & Böcker, Citation2019), and an adequate conceptualization of local political leadership in migration governance is lacking. Despite the fact that local governments usually do not have competences in the asylum/reception policy domain, there is some evidence that mayors can contribute to the development of novel practices in this area, and by extension strengthen the fulfilment of asylum seekers or undocumented migrants’ human rights (Sabchev, Citation2021; Terlouw & Böcker, Citation2019). This is in line with insights from research in other policy areas, which show that mayors can significantly alter the dynamics within local communities and advance environmental sustainability (Sotarauta et al., Citation2012). Therefore, could mayors also make the difference in municipal policy responses to forced migrants’ arrival? Moreover, how does local political leadership manifest itself in the governance of reception, and could it eventually contribute to the realization of forced migrants’ fundamental rights?

Finding answers to these questions has not only theoretical but also practical value, mainly for two reasons. First, forced migrants continue to travel to Europe in search of refuge, while frontline countries such as Greece and Italy persist in their ad hoc modus operandi in reception management (Greek Ombudsman, Citation2017; Marchetti, Citation2020). Consequently, local governments are often ‘taken by surprise’ by the opening of reception facilities within their jurisdiction (Marchetti, Citation2020). In such cases, mayors are usually called upon by their constituencies to demonstrate leadership and respond adequately to issues arising from the sudden arrival of forced migrants, regardless of whether they have formal powers in this policy area. Second, the failure of some national authorities to guarantee the minimum reception standards enshrined in European Union (EU) and international law has been well documented (Danish Refugee Council, Citation2017). In this context, mayors can potentially contribute to safeguarding forced migrants’ rights by interpreting and applying regulations from different levels and giving them meaning ‘on the ground’ (Oomen et al., Citation2021; Terlouw & Böcker, Citation2019). Notably in this regard, the mayors of major European cities, such as Athens and Barcelona, have been actively engaged in a symbolic – but also very practical – struggle for policy changes in migration governance, strongly emphasizing the need to better protect migrants’ human rights (Garcés-Mascareñas & Gebhardt, Citation2020). In short, scrutinizing the link between local political leadership and municipal policy responses to forced migrants’ arrivals can provide practical insights on how to strengthen the role of mayors in this policy area, and enhance the protection of forced migrants.

This article is an initial step in that direction. It presents evidence from extensive desk research and fieldwork in two Greek municipalities – Thermi and Delta – that faced the sudden arrival of a large number of forced migrants in 2016. I address the abovementioned questions and argue that local political leadership can influence the development and implementation of municipal policy responses to the arrival of forced migrants, and by extension, contribute to the improvement of their reception conditions. Rather than focusing exclusively on the role of mayors as local political leaders, I adopt an interactionist approach and define local political leadership as the product of the interaction between mayors and their leadership environment – a mix of institutional and societal constraints and facilitators, which mayors must navigate, to achieve their strategic objectives. Ultimately, I suggest that even in contexts where local governments have no competences in the management of reception, and where the arrival of forced migrants is initially met with hostility, mayors can directly influence the governance of reception by exercising interactive and multilevel political leadership (Sørensen, Citation2020).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Initially, I discuss the concept of local political leadership in the context of forced migrants’ reception. Subsequently, I present the methodology of the research and the justification of the case selection, followed by a detailed discussion of the developments in the two municipalities. Finally, I briefly discuss the findings and conclude with suggestions for future research.

CONCEPTUALIZING LOCAL POLITICAL LEADERSHIP IN FORCED MIGRANTS’ RECEPTION

Although political leadership – like leadership in general – is an essentially contested concept (‘t Hart, Citation2014; ‘t Hart & Rhodes, Citation2014), one can distinguish between two main approaches to studying it: the ‘classic’ approach, which focuses on the role of individual leaders, and the interactionist approach, which highlights the need to understand political leadership as an interactive process (Elgie, Citation1995; ‘t Hart & Rhodes, Citation2014). Scholars who adopt the former approach follow an agent-centred logic and argue that the driving force behind significant social and political changes is powerful individuals who occupy governmental positions (Elgie, Citation1995, p. 5). These scholars emphasize the importance of leaders’ background, motivations and behaviour, advocating a person-centric understanding of political leadership (‘t Hart & Rhodes, Citation2014). Despite its unceasing popularity, this approach has been criticized for its inadequacy to account for the causal capacity of the complex institutional and societal context in which political leaders operate (Bennister, Citation2016; ‘t Hart & Rhodes, Citation2014). As a result, it has lost its dominance in leadership studies to the interactionist approach, which embeds an agent-structure way of thinking and promotes the understanding of political leadership as the ‘product of the interaction between the leader and the environment within which the leader is operating’ (Bennister, Citation2016, p. 1). In other words, what makes political leadership effective is the quality of the interaction between the leader, on the one hand, and the institutions and the society, on the other – the way one exploits the opportunities one has in the decision-making process, the operational support or resistance one receives from the administration and the way one navigates popular reactions to emerging issues. Ultimately, this interaction – or lack thereof – facilitates or sabotages the advancement of leaders’ policy agendas.

With regard to local political leadership in particular, scholars have largely recognized the importance of context in shaping mayors’ decisions and actions, proposing the adoption of the interactionist paradigm (Lowndes & Leach, Citation2004). Contextual characteristics can play the role of ‘faithful partners’ to mayors in realizing personal policy objectives, but they can also entail significant constraints (Copus & Leach, Citation2014; Heinelt & Lamping, Citation2015). Their effect, however, is anything but deterministic: local political leaders can influence unfolding events and consequently also change their institutional and social environment (Orr, Citation2009). They can use their formal authority to mobilize municipal resources, employ ‘soft’ power to successfully negotiate with higher levels of government, or become ‘skilled storytellers’, navigating the local public opinion towards achieving a common goal (‘t Hart & Rhodes, Citation2014, p. 13). Understanding the role of local political leadership in municipal policy responses therefore requires looking through the lenses of the urban context, and the ability of mayors to exploit and change this context in a way that serves their own agenda.

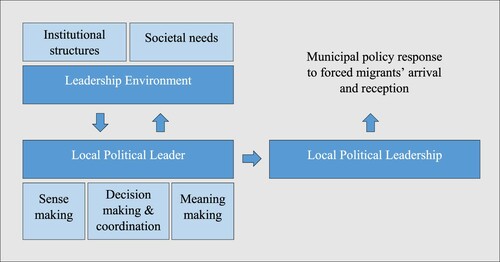

Against this background, I adopt an interactionist perspective. My starting point in developing a conceptual framework for studying local political leadership in the reception of forced migrants is the seminal work of Robert Elgie (Citation1995). Elgie conceptualizes political leadership as the product of the interaction between the leadership environment, on the one hand, and the political leader, on the other (p. 8). I build on this conceptualization – originally designed for studies of political leadership at the national level – using insights from the literature on local government, urban policy-making, migration studies and crisis management.

According to Elgie (Citation1995), the leadership environment encompasses diverse factors and forces that can be grouped under two overarching categories: institutional structures and societal needs. To start with the former, institutional structures set the boundaries within which local political leaders operate (Heinelt et al., Citation2018). Here, the position of the mayor vis-à-vis other bodies within the municipal structure must be taken into account. For instance, having control over the majority of the municipal council, or authority over new appointments and budget decisions, would make it easier for a mayor to push through policy proposals (Mullin et al., Citation2004). In addition, the ability to respond to emerging issues through the creation of ad hoc/informal bodies can also strengthen mayors’ potential to exercise leadership. Ultimately, while the independent role of ‘street-level bureaucrats’ in implementing mayoral decisions should be taken into account (Lipsky, Citation1980), administrative structures characterized by a mayor-centred local administration are likely to provide more opportunities for local leaders to shape municipal responses to the arrival of forced migrants at their discretion.

While the above arguments pertain to elements of the institutional structures at the local level, urban policy responses are rarely ‘local’ (Bazurli, Citation2020). On the contrary, they emerge through interactions, negotiations and compromises between different levels of government (Kaufmann & Sidney, Citation2020). In this respect, the formal powers granted to local authorities in the field of reception of forced migrants (and in related policy areas) should be considered in the context of the multilevel governance of migration (Caponio & Jones-Correa, Citation2017). The multilevel nature of migration policy-making indicates the gradual dispersion of formal responsibility over migration and integration-related issues between supranational (e.g., the EU), national (ministries, central government agencies) and subnational institutions (regional and local authorities). This inevitably affects the ‘rules of the game’ for local political leaders seeking to respond to the arrival of forced migrants. Mayors who have access to higher level decision-making arenas (e.g., through party membership) – where asylum-related issues are usually decided – obtain additional resources to influence policy processes within and beyond their jurisdiction (Sørensen, Citation2020). In addition, discretionary spaces and ‘grey zones’ within established legal/policy frameworks can provide opportunities for mayors to bring forward innovative practices in forced migrants’ reception (de Graauw, Citation2014; Dobbs et al., Citation2019). In short, the institutional structures that shape mayors’ leadership environment extend beyond the local government realm and include higher levels of public authority. It goes without saying that this creates more opportunities, but also constraints, for mayors to exercise leadership in municipal policy responses to the arrival of forced migrants.

When it comes to societal needs – the second dimension of the leadership environment – one can identify three important elements that influence political leaders’ capacity to accomplish their goals: historical legacy, societal attitudes and popular desires (Elgie, Citation1995, pp. 20–23). In the context of forced migrants’ reception, the historical legacy of a municipality pertains to the historical presence of immigrants and the relevant experiences of the local population. For example, local history of refugee welcome may contribute to similar attitudes towards future arrivals. With regard to societal attitudes, the voting behaviour of the local electorate can serve as a good indicator. Significant support for anti-immigrant parties, or alternatively, for parties advocating for the protection of forced migrants’ rights, can create either propitious or unfavourable conditions for mayors to push their own policy agenda. Finally, the popular desires correspond to short-term requests from the local community, especially in response to external disruptions, such as the sudden opening of a reception centre on municipal territory. In these circumstances the mobilization and actions of locally operating – but not necessarily locally based – collective and individual actors (interest groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), grassroots organizations, volunteers, etc.) must be taken into account. Mayors on their behalf are expected to demonstrate leadership by navigating those different stakeholders, while at the same time fulfilling their legal and moral obligations.

Having unpacked the notion of leadership environment, I now turn to the protagonist behind manifestations of local political leadership: the mayor. First, it should be noted that each political leader is unique and has his/her own beliefs, motivations and ambitions (Elgie, Citation1995, pp. 9–12). In this regard, one approach to studying local political leadership would be to look for a causal link between mayors’ personal characteristics and mayors’ success in navigating their leadership environment to advance their policy agenda (van Esch & Swinkels, Citation2015). However, rather than focusing on the motivations behind certain mayoral decisions, the purpose of this study is to establish whether mayors can influence forced migrants’ reception by exercising their leadership, and to shed light on the process by which this can be achieved. Therefore, I follow Robinson’s (Citation2014) assertion that ultimately ‘leaders are what leaders do’ and focus on mayors’ decisions and actions. Nonetheless, I take into account evidence that variations in the partisanship of local incumbents are conducive to different policy responses in the realm of migration (Steil & Vasi, Citation2014), and consider the potential impact of mayors’ ideological stance on their responses to forced migrants’ arrivals. In particular, left-leaning mayors and local administrations are more likely to promote inclusive policies than right-wing ones (de Graauw & Vermeulen, Citation2016; Steil & Vasi, Citation2014).

A final point to address when discussing mayors’ role in shaping forced migrants’ reception relates to the widespread uncertainty and sense of urgency that often accompanies sudden migrant arrivals. This is particularly relevant to the Greek context in the period 2015–16, where reception centres were set up within days, using ad hoc measures and temporary facilities, and without any coherent overarching plan or strategy (Greek Ombudsman, Citation2017). These circumstances call for the development of a tailored approach to studying the decisions and actions of local political leaders (de Clercy & Ferguson, Citation2016; Orr, Citation2009). Therefore, using insights from the framework of Boin et al. (Citation2016) on leadership in crisis management, I identify three strategic leadership tasks in forced migrants’ reception: sense-making, decision-making and coordination, and meaning-making. First, sense-making entails the detection of an emerging crisis and its significance. The earlier an accurate assessment is made, the better a local leader can prepare for the coming disruption in terms of both applying the desired discursive strategy to frame the issue and preparing the operational response. Second, decision-making and coordination involves making critical decisions and orchestrating a coherent response. Here, mayors are expected to unfold their leadership potential by leveraging the enabling factors that their leadership environment offers, or in other words, by mobilizing institutional and societal resources to their advantage. Finally, the meaning-making consists of building a narrative to inspire and convince citizens, make them understand the events, accept the mayor’s decisions and support his/her actions. By focusing on these three aspects of mayors’ behaviour in their relationship with the local leadership environment, I aim to shed light on how they manage – both discursively and operationally – the consequences of the arrival of forced migrants.

In summary, local political leadership in the reception of forced migrants is manifested through the interaction between the local political leader and his/her leadership environment. The former includes the decisions and actions of the mayor in the context of the arrival of migrants, while the latter pertains to the institutional structures within a multilevel governance setting, and the reactions and demands of local society. Mayors unfold and exercise their local political leadership by seizing the opportunities and overcoming the obstacles in their leadership environment. Their success in doing so determines their ability to push through policies and practices in forced migrants’ reception that serve their strategic goals ().

On the basis of this conceptual framework, I now proceed to presenting the methodology and case selection. I argue that the municipalities of Thermi and Delta provide an example of two cases with very similar local leadership environments, in which the respective mayors approached the arrival of forced migrants in a very different way. The diverging dynamics in the two municipalities between the local political leaders, on the one hand, and the institutional structures and societal needs, on the other, led to very different outcomes in terms of municipal policy responses.

METHODOLOGY AND CASE SELECTION

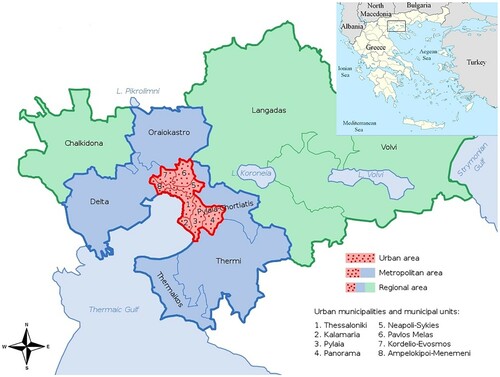

To explore the potential of local political leadership to influence forced migrants’ reception, I apply an in-depth qualitative comparative case study research design (Rohlfing, Citation2012). Case studies are widely used in research on local political leadership and local responses to immigration because of the opportunities they provide to use rich data in a context-sensitive analysis (Bazurli, Citation2019; Copus & Leach, Citation2014; Hinger et al., Citation2016). I study two self-governing municipalities – Thermi and Delta – located on either side of the metropolitan city of Thessaloniki, equidistant from its urban centre (). In 2016, these municipalities faced the opening of large reception centres on their territory by the central government. I use a co-variational analysis (Blatter & Haverland, Citation2012, pp. 33–78) and conduct both within- and cross-case analysis of the role of local political leadership in Thermi and Delta. The two cases show minimal variance on a number of contextual characteristics (), while at the same time being significantly different in terms of their political leaders.

Figure 2. Urban, metropolitan and regional area of Thessaloniki with its self-governing municipalities, including Delta on the west and Thermi on the east side of the metropolitan area.

Sources: Greece_2011_Periferiakes_Enotites.svg: Pitichinaccio derivative work: Philly boy92, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thessaloniki_urban_and_metropolitan_areas_map.svg and Lencer, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Greece_location_map.svg

Table 1. Territorial, demographic and economic characteristics of the municipalities of Thermi and Delta.

In terms of institutional structures, Greek mayors have significant political authority and have traditionally played a dominant role within municipal structures (Hlepas, Citation2012, p. 267; Hlepas & Getimis, Citation2011, p. 417). They are elected by popular vote for a five-year term, which gives them a high degree of legitimacy, a powerful position vis-à-vis other municipal bodies, and the ability to use ‘soft’ power to negotiate local issues with higher levels of government (Hlepas, Citation2012). Despite recent reforms that have weakened this mayor-centred model, Greek mayors remain one of the strongest in Europe when it comes to their institutional relationship with the municipal council and administration (Heinelt et al., Citation2018, pp. 36–37). They appoint deputy mayors, establish taskforces and assign them duties, and can also appoint municipal councillors to carry out specific tasks. Finally, at the time of this research, the electoral system in Greece guaranteed the majority within the municipal council to the mayor’s faction, effectively placing the mayor at the centre of a majoritarian rule, with all municipal resources at his/her disposal (Hlepas, Citation2012, p. 269).

Although these features of the Greek local government system facilitate mayors’ ability to exercise their political leadership, the reception of forced migrants in Greece remains an exclusive competence of the central state. In theory, local governments can only influence a few aspects related to the functioning of a reception centre, such as waste management and water supply. However, the inadequacy of the Greek government to meet the challenges posed by the increased number of arrivals during 2015’s ‘long summer of migration’ led to a widespread adhocracy in reception management (Sabchev, Citation2021). A wide range of actors from the international, national and local levels performed various functions with little or no coordination, often outside the legal and policy framework (Greek Ombudsman, Citation2017). This created an opportunity for local governments and their political leaders to influence the reception of forced migrants by pushing the boundaries of their competences in some cases, or even overstepping them in others. In short, despite the lack of formal powers in the field of reception, mayors retained considerable leeway to utilize their institutional structures, mobilize available resources and influence migrants’ reception.

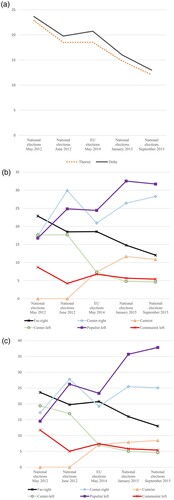

Moreover, Thermi and Delta are very similar in terms of their societal needs. Both municipalities consist of a number of relatively small settlements spread over the municipal territory, which were established about a century ago by Greek refugees fleeing Turkey. Consequently, both municipalities host a network of local associations that organize various activities with the aim of preserving the collective historical memory of their refugee past. In addition, the municipalities are also very similar in terms of electoral support for far-right anti-immigrant parties and voting behaviour in general (). Most importantly, however, the opening of reception centres in Thermi and Delta was met with arguably identical responses of discontent from part of the local population. Amid the announcement of the expected arrival of forced migrants, protests instigated by the far right broke out. Long extraordinary municipal council meetings took place in the presence of angry citizens who interrupted the proceedings multiple times and requested that no reception centres were opened on the municipal territory. Self-organized ‘committees’ of locals who opposed the opening of the centres, as well as groups who mobilized in support of the arriving forced migrants, were present in both municipalities. Lastly, in both cases there was intimidation and violence against the mayors themselves. In Delta, a group of locals attacked the mayor after his unsuccessful attempt to prevent the opening of the reception centre (Aslanidis, Citation2016). In Thermi, just a few nights after the mayor expressed his commitment to supporting the arriving migrants, his car was set on fire outside his home (Fotopoulos, Citation2016).

Figure 3. (a) Electoral support for far-right anti-immigrant parties in Thermi and Delta (2012–15); (b) voting behaviour in national/European Union (EU) elections, Municipality of Thermi (2012–15); and (c) voting behaviour in national/EU elections, Municipality of Delta (2012–15).

Note: Based on data from the official database of the Greek Ministry of Interior (https://ekloges.ypes.gr/). Political parties included in each category are: far-right (anti-immigrant): Golden Dawn, Independent Greeks and Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS); centre-right: New Democracy; centrist: To Potami and Union of Centrists; centre-left: Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) and Democratic Left (DIMAR); populist left: Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA); and communist-left: Communist Party of Greece (KKE).

While Thermi and Delta offered very similar leadership environments at the time of the arrival of forced migrants, they differed significantly in terms of political leaders. As explained in the next section, this led to very different outcomes in terms of exercising political leadership and shaping municipal responses. On the one hand, the mayor of Thermi, whose experience in local government structures started in 1982, served his fifth consecutive mandate. He was first elected mayor in 1998 and ever since has been securing his re-election from the first round, gaining the support of more than half of the local voters. On the other hand, Delta’s mayor served his first term after winning the local elections in 2014 at the ballotage, and his political career at the local level dates back only to the second half of the 2000s. While national parties in Greece are legally excluded from participating in local elections, Thermi’s mayor is affiliated to the centre-left Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) and Delta’s mayor to the centre-right New Democracy. During the studied period, these parties were in opposition to the central government led by the left-wing populist Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA) (Stavrakakis & Katsambekis, Citation2014). Lastly, although both mayors opposed the opening of reception centres in the sites chosen by the central government, their ideological differences combined with the much longer tenure of Thermi’s mayor triggered the adoption of very different strategies in managing the consequences of the arrival of forced migrants. The differences in the exercise of local political leadership they demonstrated had a direct impact on forced migrants’ reception conditions.

The data used in the present study were collected in the context of the ‘Cities of Refuge’ research project.Footnote2 Initially, an extensive desk research was carried out, which included the review of municipal council proceedings and decisions, press releases/public statements of the two mayors, announcements of local political factions represented in the municipal councils, local/national media and social media publications, reports, and secondary academic sources. Subsequently, interviews were held in October–November 2018 with six members of the municipal government and administration.2 Questions were asked about the engagement of the municipalities in terms of concrete measures related to the reception of forced migrants, and the decisions and actions of political leaders. In this way, any discrepancies between the stance of the local government led by the mayor and the municipal administrative staff could be detected. Rather than in isolation, these data were reviewed in the context of the developments at the time in the wider region of the city of Thessaloniki (Sabchev, Citation2021). In this respect, participant observation and interviews with representatives of the Ministry of Migration Policy, other municipal authorities in the area, and NGOs delivering services to locally residing forced migrants, provided additional insights into the events taking place in the two municipalities (). Triangulation between the different sources of data was used to assess the reliability of the information obtained through interviews. Finally, the collected data were incorporated into NVivo 11 and then coded into categories derived from the conceptual framework developed above.

Table 2. List of interviews.

FINDINGS

This section presents the results of the data analysis through the prism of the conceptual framework. It starts with a brief background on the broader context in which the events in Thermi and Delta took place. It then provides a detailed description of local political leadership in the two municipalities and its role in the development of local responses to the arrival of forced migrants.

Forced migrants’ arrivals and reception in Greece in 2015–16

In the summer of 2015, arrivals to Greece increased sharply, leading to what would later become known as Europe’s refugee reception crisis (Ambrosini et al., Citation2019). Amid thousands of forced migrants landing on the Aegean islands, German Chancellor Angela Merkel promoted a welcoming stance and decided to keep Germany’s borders open. This led to an intensified movement of people through the so-called ‘Balkan route’: the main passage to Central and Western Europe which started in Greece and ran through the Western Balkan countries.

However, the initial enthusiasm and welcoming attitude towards the arriving migrants quickly succumbed to discussions about stricter border control, which began to dominate the agendas of EU member states. A new ‘hotspot’ approach was introduced on the Greek islands, which would ensure that forced migrants arriving in the country would also apply for asylum there (Dimitriadi, Citation2017). In March 2016, the border between Greece and North Macedonia was closed, blocking the Balkan route and trapping thousands of people in Greece (Anastasiadou et al., Citation2017).

Under these circumstances, the Greek government had to address an issue that exceeded its capacities. While more than 50,000 forced migrants were in need of shelter, there were only about 4000 reception places on the mainland.Footnote3 With the help of EU emergency funding, the government began to open large centres, which were managed by the army and the newly established Ministry of Migration Policy, with the assistance of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and a number of (international) NGOs. Reception was usually arranged in abandoned factories and old military camps, with substandard conditions and services, and with forced migrants receiving shelter in tents or in containers (Greek Ombudsman, Citation2017).

The opening of reception centres was sudden and quick, without any previous consultation with local authorities or communities. In many cases, this led to widespread discontent, misinformation and tensions in the places of arrival. The Greek central government has exclusive competence over reception, as well as over other relevant policy areas, such as healthcare and education, and local governments can only implement additional supporting projects, if they have the good will and resources to do so. However, amid the country’s economic crisis, financial transfers from the central to the local level – the main funding source of Greek municipalities – were cut by 60% in the period 2009–14 (Hlepas & Getimis, Citation2018, p. 61; Sabchev, Citation2021, p. 2). Therefore, mayors found themselves between a rock and a hard place: they had neither the mandate nor financial resources to influence the reception of forced migrants, while they also had to respond to the discontent of the local population. This was precisely the case in Delta and Thermi, where large reception centres opened in February and June 2016 respectively.

Mayors’ strategies and local political leadership in Thermi and Delta

As already noted, the local leadership environment provided the two mayors similar burdens and opportunities to unfold their leadership skills and realize their policy objectives. However, the relationship between the mayors and their leadership environment differed greatly. With a centre-left ideological background and high local popularity after five consecutive terms in office, the mayor of Thermi decided to pursue a risky strategy and defend the rights of forced migrants. This placed him in direct opposition to part of the local population, who protested against the reception of forced migrants in the municipality. On the other side of Thessaloniki, the mayor of Delta decided to take the opposite stance. He joined the local protests and tried to prevent the opening of the reception centre on the territory of his municipality. A closer look at how the two mayors unfolded their responses within the context of their leadership environments reveals important differences in each of the three strategic leadership tasks identified above, i.e., sense-making, decision-making and coordination, and meaning-making.

To begin with the sense-making, Thermi’s mayor recognized the significance of the emerging crisis much earlier, took steps to frame it as a humanitarian issue, and immediately began to address some of the pitfalls he had identified within his leadership environment. More than half a year before the news of the opening of reception centres across the country, the municipal government launched campaigns to mobilize aid for the forced migrants arriving on the Greek islands and passing through the country. These initiatives were realized with the involvement of the municipal services and took place in facilities spread throughout the municipal territory, including senior citizens’ centres, where the locals spent much of their time discussing everyday matters. This helped not only to raise awareness about the humanitarian dimension of the situation, but also to identify municipal areas where the local population tended to express negative or even xenophobic views. In such cases, members of the municipal government or the administration visited the place informally, with the intention of introducing a humanitarian perspective and trying to steer the public discourse in the desired direction (T2). Moreover, amid the closure of the Balkan route, when the central government needed to quickly secure reception sites, the mayor of Thermi offered certain facilities within the municipal territory, which could be used for the temporary reception of forced migrants. The facilities could only accommodate a relatively small number of people and served the mayor’s strategic objectives (Municipality of Thermi, Citation2016). However, these proposals were rejected by the ministry, without any official justification. Just a few months later, the central government opened a large reception centre in a new location in Thermi – an old, abandoned warehouse – without any previous communication or coordination with the local government (T2).

On the contrary, Delta’s mayor underestimated the sensitive and complicated nature of the issue of forced migrants’ arrivals, as well as its direct relevance to his municipality. Although Delta’s municipal administration was involved in the collection of humanitarian aid in the months before the border closure, this involvement was only marginal in comparison with that in Thermi, and was initiated by an NGO. In addition, no concrete steps were taken to develop a counter-narrative in response to potential xenophobic rhetoric, or to prepare the local community for the eventual arrival of forced migrants (D1).

In terms of decision-making and coordination, both mayors opposed the central government’s decision to open the concrete reception centres in their municipalities. However, they did so in very different ways, especially in terms of how they exploited their leadership environments. Thermi’s mayor announced that the municipal government was against the opening of the centre because of the lack of collaboration from the central government, and the appalling conditions in which forced migrants were sheltered. While he acknowledged that the functioning of the facility itself was beyond his competence, he announced the mobilization of all the available municipal resources in order to ensure decent living conditions for the forced migrants hosted in the municipality. Taking full advantage of the adhocracy in the management of reception at the time (Sabchev, Citation2021) and of his formal competences and room for discretion, Thermi’s mayor established a task force composed of municipal councillors and technical staff with the aim of addressing the problems in the reception centre (Thermis Dromena, Citation2016a). The municipal employees took care of the power supply, provided stoves and wood for heating during the winter, cleaned the facilities after they had been flooded by heavy rains, and took measures to ensure the safety of the sheltered migrants. Importantly, all these initiatives were carried out with a high level of enthusiasm and professionalism by the municipal staff, which was considered crucial by the municipal government.

When we asked [name of a municipal employee] to go to the coordination meeting [in the reception centre], she did not go just to pass the time. She went with documents, came back, did… I knew that if I did not go, she will be there and she will communicate, manage things according to the instructions of the mayor … . (T2)

In addition, communication and collaboration with a wide range of actors was a key element in the strategy of Thermi’s mayor. When the reception centre opened, he convened a meeting to discuss emerging issues and potential solutions with locally elected members of parliament (MP) and representatives of the regional authorities, other municipalities in the area, the UNHCR, the police and the Church (Thermis Dromena, Citation2016b). In collaboration with the UNHCR, local stakeholders and volunteers, the municipality organized a number of activities aimed at making forced migrants feel part of the local community, for example, by enabling participation in local festivities and museum visits (Thermis Dromena, Citation2016c). Moreover, the municipal government ‘put in the loop’ local businesses (T2). For instance, it arranged that food donations for the forced migrants are purchased by the local association of agricultural producers, which had expressed concerns about the proximity of the reception centre to farms. Such collaborations also helped the municipal government circumvent bureaucratic obstacles stemming from the lack of competences in the field of reception. At the same time, they strengthened the acceptance of the mayor’s agenda by showing the local community that not only the municipal authorities but also other local actors demonstrated solidarity with the hosted migrants.

The mayor of Delta adopted a radically different strategy. When negative reactions against the opening of the reception centre sparked in his municipality, he opposed the central government’s decision and joined the local protests. In an attempt to prevent the opening of the facility, the mayor paid a personal visit to the Minister of Migration Policy and the public prosecutor. When these visits turned out to be in vain and the reception centre eventually opened, the mayor initially refused to send municipal trucks to collect waste at the facility – a decision he later withdrew (MMP, D1). In fact, other mayors from nearby municipalities intervened: they visited the centre and facilitated rubbish collection, the electricity and water supply, and even donated wood to ensure heating during the winter (TyposThess, Citation2016). In parallel, NGOs, grassroots organizations and local volunteers filled other gaps in the service provision in the reception centre (TH1, TH2).

In stark contrast to the local response to the arrival of forced migrants in Thermi, there were no permanent channels of communication and cooperation between the municipal government, municipal services and local stakeholders in Delta. For example, the Association of Municipal Employees organized the collection and delivery of aid to the reception centre immediately after its opening (DeltaNews, Citation2016). However, the mayor ‘raised a wall’ against any further substantial involvement of the administration (D1). Although municipal services occasionally participated in the implementation of small-scale initiatives for locally residing forced migrants organized by NGOs, all relatively ambitious proposals requiring the approval of the municipal government were turned down. In this respect, municipal staff described the stance of the local government as ‘distant’, explicitly mentioning the mayor as the leading factor behind this (D1). Nonetheless, rather than blaming the mayor for the situation, they explained his actions by referring to the negative and even violent reactions of some locals upon the opening of the reception centre.

Lastly, with regards meaning-making and the role of leaders in building a narrative to influence public opinion and convince citizens to follow them, Thermi’s mayor pursued a strategy that aimed to isolate the far right and prevent it from monopolizing the local discourse:

Our strategy was to look around and to separate, to split, and not to let the front [against the reception of forced migrants] become too strong, and thus be able to lead astray others. We tried, therefore, to bring this Committee [of locals protesting against the opening of the centre] closer and to release some common statements, hedging them. How – they were saying ‘We do not want refugees here in any case’, and we were announcing – a common statement though – that we do not accept refugee reception without our participation, for instance. Inside [the Committee] there were conservative people, people who were afraid because of the lack of information. We tried, therefore, to break this [front] and to leave those with extreme views very few and isolated from the rest of the community. And the rest to bring… And we managed.(T2)

In parallel, Thermi’s municipal newspaperFootnote4 regularly addressed the issue of the reception of forced migrants, emphasizing its humanitarian nature. The newspaper detailed the deplorable conditions in the reception centre, whose residents were mainly children, and the inability of the state to ensure access to basic rights and decent living conditions for migrants. At the same time, the outlet presented the local government as the guardian of people’s rights, highlighting all its actions related to the reception of migrants. To give an example, at the end of November 2016 – two months after the start of the school year and when several hundred children living in the centre were not receiving formal education – the municipal government organized a protest in front of the regional ministerial office in Thessaloniki. Led by Thermi’s mayor himself, municipal councillors and forced migrants demanded measures on behalf of the central government, with regard to both the children’s schooling and the improvement of living conditions in the reception centre. Following the demonstration, an article entitled ‘Sub-zero the temperatures and the interest of the state for the refugees in the camp in Thermi’ appeared in the municipal newspaper, which highlighted, among other things, the lack of heating and security in the facility, and the need to fulfil the fundamental right to education for all children (Thermis Dromena, Citation2016d).

On the contrary, at its extraordinary meeting following the news of the imminent arrival of forced migrants, Delta’s municipal council gave a platform to an MP from the far-right Golden Dawn – a decision that was heavily criticized by local left-wing factions (Laiki Syspirosi Municipality of Delta, Citation2016). The Golden Dawn MP used this opportunity to portray the expected newcomers as illegals and criminals. On his behalf, Delta’s mayor emphasized that the opening of the reception centre would ‘put in danger the normal everyday life of locals and businesses’ (Municipality of Delta, Citation2016c). In line with the adoption of a discourse that presented forced migrants as a threat, he put forward measures to enhance security in the area (Municipality of Delta, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Following his failed attempt to prevent the opening of the centre, ‘the mayor kept distance, afraid that any involvement in the refugee issue would result in strong reactions by the local community’ (D1).

In the end, Thermi’s proactive mayor made extensive use of the opportunities that his leadership environment provided and skilfully addressed the challenges that it posed. In contrast, his reactive colleague in Delta was late in discovering the issues arising from the arrival of forced migrants, and failed to organize a coherent response in collaboration with the municipal administration and other local stakeholders. The reception centre in Thermi was eventually closed a year after its opening due to the high cost and unsuitability of the chosen facility. Shortly thereafter, the municipality joined a reception project, establishing a partnership with the UNHCR, other municipalities in the area and several NGOs. As a result, Thermi hosted a small number of asylum seekers in private apartments, facilitating newcomers’ access to legal assistance, healthcare, education and local job opportunities (T1). On the other side of Thessaloniki, the reception centre in Delta remained operational, despite repeated protests from both locals and forced migrants. Local NGOs continued to carry out activities to improve access to services and living conditions in the centre, and also implemented small-scale reception projects for asylum seekers, similar to the one in Thermi, but without the participation of Delta’s local government (N1, N2). Finally, the local elections in Greece in 2019 partially confirmed the assumption that successful leadership equals political survival (‘t Hart & Rhodes, Citation2014): the mayor of Thermi won his sixth consecutive term – again in the first round – while the mayor of Delta lost in the ballotage.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

What prompted the adoption of strikingly different policy responses to the arrival of forced migrants in the two municipalities? At first glance, and in line with previous research on local responses to immigration (de Graauw & Vermeulen, Citation2016; Steil & Vasi, Citation2014), partisanship explains the humanitarian and welcoming stance of Thermi’s mayor, and the security-oriented and distant stance of Delta’s mayor. However, this is only part of the story. While ideology was arguably one (or even the) motivating factor behind the decisions of the two mayors, it says little about the effectiveness of their strategies, and by extension about the ‘on the ground’ impact of their actions. Both political leaders were called upon to provide solutions by local electorates with very similar voting behaviours, in equally conflict-ridden and unpredictable contexts, and within the same institutional structures. In other words, the two mayors were dealt the same cards, but they played them very differently, which ultimately affected the reception conditions for the arriving forced migrants.

My main argument, therefore, is that local political leadership – i.e., the way mayors seize the opportunities and overcome the constraints in their leadership environment – contributes to the development and implementation of municipal policy responses to the arrival of forced migrants. Mayors ‘are not tossed helplessly on the waves of structural changes’ in migration governance (Orr, Citation2009, p. 42). Their decisions and actions can significantly impact forced migrants’ reception conditions – thus contributing to the realization of migrants’ fundamental rights – even when local governments do not have formal competences in the asylum/reception policy domain. Moreover, the findings presented above lead to the assertion that mayors also have the potential to influence in the long-term attitudes of local communities towards forced migrants. In this regard, local political leadership may well be a previously overlooked factor that could help explain cases where local governments led by factions positioned on the right side of the political spectrum introduce progressive policies for forced migrants, seemingly at no political cost. Such cases have indeed been recorded in other Greek municipalities (e.g., Trikala) in the context of the ‘Cities of Refuge’ research. Local political leadership therefore deserves more attention as a potential new element in the constellation of causal factors that shape municipal policy responses to the arrival of forced migrants.

This brings to the fore the issue of how local political leadership manifests itself in the reception of forced migrants. Insights from the crisis management literature (Boin et al., Citation2016), along with the examples of Thermi and Delta, suggest that this occurs through a combination of political, operational and discursive responses on behalf of mayors. The findings here confirm the assertion that local governments and their leaders have significant room for discretion within legal and situational contexts to influence migration-related matters (de Graauw, Citation2014; Terlouw & Böcker, Citation2019). They can ‘inhabit’ this discretionary space by leveraging available municipal resources and building partnerships with both public and private actors positioned across the multilevel setting of migration governance (Oomen et al., Citation2021). Moreover, in the highly politicized field of forced migrants’ reception, mayors can make a difference by navigating the public discourse in a timely and careful manner, and by making efforts to isolate and weaken sources of extreme and xenophobic rhetoric.

Such practical matters inevitably raise the question of what constitutes ‘successful political leadership’ in migration governance. In this regard, the two examples presented in this study are closely related to the emerging debate in leadership studies around the concept of ‘interactive political leadership’. Interactive political leadership constitutes ‘a strategic endeavour to govern society effectively and legitimately through the systematic involvement and mobilisation of relevant and affected members of the political community’ (Sørensen, Citation2020, p. 3). It entails skilful use of what Nye (Citation2008) identified as ‘smart power’ – a combination between limited use of ‘hard power’ (e.g., creating a task force with concrete duties) and extensive use of ‘soft power’ (e.g., persuasion, strategic use of the media). Such leadership – when properly performed – can boost leaders’ legitimacy, advance their policy strategies and maintain or even increase support (Sørensen, Citation2020). Moreover, for local politicians it also entails purposeful engagement in attempts to influence policy processes at the national and transnational levels of governance, which Sørensen describes with the term ‘multilevel leadership’ (pp. 94–110). In contrast, in the tangled, polycentric and multilevel realm of urban migration policy-making, sovereign leadership styles and the logic of ‘I do not want to take part if I cannot get things my own way’ becomes less legitimate and of little benefit to mayors and forced migrants alike (p. 66).

It would be problematic to draw general conclusions on the basis of this study. That said, research conducted in a number of municipalities in several EU countries in the context of ‘Cities of Refuge’ suggests that interactive and multilevel local political leadership has been an important factor in the development of more welcoming and inclusive municipal approaches to forced migrants’ reception and integration (e.g., Oomen et al., Citation2021; Sabchev, Citation2021). In addition, a number of studies in migration policy research and refugee studies demonstrate similar findings, highlighting the explicit engagement of local political leaders in building coalitions with local and transnational partners (Betts et al., Citation2020; Garcés-Mascareñas & Gebhardt, Citation2020). This is particularly relevant for larger cities, whose mayors have more resources and soft power to employ strategies based on negotiation, collaboration and persuasion in advancing their policy goals (Sørensen, Citation2020). In any case, further comparative research is needed to clarify the conceptual relevance of both interactive and multilevel political leadership to migration studies, as well as their potential added value in developing policy responses that preserve social cohesion and safeguard the rights of forced migrants.

The above discussion serves well as a reminder of the need to reflect upon the value of the conceptual framework developed in this article. The inherently polycentric nature of urban migration policy-making, in addition to the presented empirical evidence from Greece, seems to justify an interactive approach to the study of local political leadership in migration governance. Nonetheless, alternative conceptualizations and their potential explanatory value for migration research should also be explored. For instance, careful accounts of political leaders’ background could uncover important individual motivations, and help explain prima facie contradictions between partisanship and policy responses to forced migrants (Marchetti, Citation2020).

This study concludes with two suggestions for future research, in addition to those already indicated above. First, while the lack of formal powers in the area of forced migrants’ reception is common for municipal authorities in Europe, the ‘extreme concentration of power in the hands of the (directly elected) mayor’ in the Greek local government system is the exception rather than the rule (Hlepas, Citation2018). Cross-country comparisons of how institutional structures shape the ability of mayors to respond to the arrival of forced migrants may therefore shed light on the possibilities and limits of local political leadership. Second, if political leadership matters at the local level, then does it also affect migration policies at higher levels of government, where the leadership environment provides greater opportunities, but also increases obstacles/barriers? Strengthening the dialogue between leadership and migration scholars can help advance theory-building on the role of people holding key positions in politics or public administration in migration policy-making at different levels. At a practical level, it can also help develop effective strategies to address the inevitable pitfalls that the complex realm of migration governance hides.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is greatful to Professor Signy Irene Vabo, Professor Dr David Kaufmann, Dr Raffaele Bazurli and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The term ‘forced migrants’ refers here to the broad category of people on the move who seek international protection, regardless if they have already submitted their request for asylum or not. In this way, this study aims to account for the complexity of the migratory population movement in the studied period (2015–19), and the fact that people regularly shift between categories that do not necessarily correspond to their experiences (Crawley & Skleparis, Citation2017).

2 ‘Cities of Refuge' is a 5-year research project funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, that explores and explicates the relevance of international human rights, as law, praxis and discourse, to how local governments in Europe welcome and integrate refugees https://citiesofrefuge.eu/.

3 Interviews were held by the author and lasted on average 47 min. The individuals interviewed were selected on the basis of their direct involvement in (1) the decision-making process or (2) the implementation of measures related to the reception of forced migrants.

5 The municipal newspaper of Thermi is a 32-page monthly publication issued by the municipality and distributed free of charge to local residents (20,000 copies). It contains news about municipal programmes, projects, events, municipal council decisions and a section devoted to announcements by the political factions represented in the municipal council.

REFERENCES

- Ambrosini, M., Cinalli, M., & Jacobson, D. (2020). Migration, borders and citizenship between policy and public spheres. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ambrosini, M., Van Hootegem, A., Bevelander, P., Daphi, P., Diels, E., Fouskas, T., Hellström, A., Hinger, S., Hondeghem, A., Kováts, A., & Mazzola, A. (2019). The refugee reception crisis: Polarized opinions and mobilizations. Éditions de l'Université de Bruxelles.

- Anastasiadou, M., Marvakis, A., Mezidou, P., & Speer, M. (2017). From transit hub to dead end: A chronicle of idomeni. Retrieved September 21, 2018, from http://bordermonitoring.eu/berichte/2017-Idomeni/

- Aslanidis, T. (2016, February 13). Diavata: Merida Diadiloton Propilakise ton Dimarcho Delta [Diavata: A group of demonstrators attacked the mayor of delta]. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from https://www.thestival.gr/eidiseis/koinonia/223009-diabata-merida-diadiloton-propilakise-ton-dimarxo-delta/

- Bazurli, R. (2019). Local governments and social movements in the ‘refugee crisis’: Milan and Barcelona as ‘cities of welcome’. South European Society and Politics, 24(3), 343–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2019.1637598

- Bazurli, R. (2020). How “urban” is urban policy making? PS: Political Science & Politics, 53(1), 25–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519001343

- Bennister, M. (2016). New approaches to political leadership. Politics and Governance, 4(2), 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v4i2.683

- Betts, A., MemiŞoĞlu, F., & Ali, A. (2020). What difference do mayors make? The role of municipal authorities in Turkey and Lebanon’s response to Syrian refugees. Journal of Refugee Studies, feaa011. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa011

- Blatter, J., & Haverland, M. (2012). Designing case studies: Explanatory approaches in small-N research. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Boin, A., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2016). The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge University Press.

- Caponio, T., & Jones-Correa, M. (2017). Theorising migration policy in multilevel states: The multilevel governance perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(12), 1995–2010. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341705

- Copus, C., & Leach, S. (2014). Local political leaders. In R. A. W. Rhodes & P. ‘t Hart (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of political leadership (pp. 549–563). Oxford University Press.

- Crawley, H., & Skleparis, D. (2017). Refugees, migrants, neither, both: Categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe’s ‘migration crisis’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224

- Danish Refugee Council. (2017). Fundamental rights and the EU hotspot approach. Retrieved August 15, 2020, from https://drc.ngo/media/4051855/fundamental-rights_web.pdf

- de Clercy, C., & Ferguson, P. (2016). Leadership in precarious contexts: Studying political leaders after the global financial crisis. Politics and Governance, 4(2), 104–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v4i2.582

- de Graauw, E. (2014). Municipal ID cards for undocumented immigrants: Local bureaucratic membership in a federal system. Politics & Society, 42(3), 309–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329214543256

- de Graauw, E., & Vermeulen, F. (2016). Cities and the politics of immigrant integration: A comparison of Berlin, Amsterdam, New York City, and San Francisco. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(6), 989–1012. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1126089

- DeltaNews. (2016). Ergazomenoi kai Proin 5minites Dimoy sto Plevro ton Prosfigon [Employees and Former 5-month Municipal Staff in Support of Refugees]. https://deltanews.gr/ergazomenoi-kai-proin-5minites-dimou-s/

- Dimitriadi, A. (2017). Governing irregular migration at the margins of Europe: The case of hotspots on the Greek islands. Etnografia e Ricerca Qualitativa, 1, 75–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3240/86888

- Dobbs, E., Levitt, P., Parella, S., & Petroff, A. (2019). Social welfare grey zones: How and why subnational actors provide when nations do not? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(9), 1595–1612. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1432343

- Elgie, R. (1995). Political leadership in liberal democracies. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Fotopoulos, N. (2016, June 30). Empirismos me Ratsistiko Prosimo [Racist motives behind the arson]. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from https://www.efsyn.gr/ellada/dikaiomata/74634_emprismos-me-ratsistiko-prosimo

- Garcés-Mascareñas, B., & Gebhardt, D. (2020). Barcelona: Municipalist policy entrepreneurship in a centralist refugee reception system. Comparative Migration Studies, 8(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-0173-z

- Greek Ombudsman. (2017). Migration flows and refugee protection. Administrative challenges and human rights issues. Retrieved September 20, 2018, from https://www.synigoros.gr/?i=human-rights.en.recentinterventions.434107

- Heinelt, H., Hlepas, N., Kuhlmann, S., & Swianiewicz, P. (2018). Local government systems: Grasping the institutional environment of mayors. In H. Heinelt, A. Magnier, M. Cabria, & H. Reynaert (Eds.), Political leaders and changing local democracy (pp. 19–78). Springer.

- Heinelt, H., & Lamping, W. (2015). The development of local knowledge orders: A conceptual framework to explain differences in climate policy at the local level. Urban Research & Practice, 8(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2015.1051378

- Hinger, S., Schäfer, P., & Pott, A. (2016). The local production of asylum. Journal of Refugee Studies, 29(4), 440–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/few029

- Hlepas, N. (2012). Local government in Greece. In A. M. Moreno (Ed.), Local government in the Member States of the European Union: A comparative legal perspective (pp. 257–281). National Institute of Public Administration of Spain.

- Hlepas, N. (2018). Between identity politics and the politics of scale: Sub-municipal governance in Greece. In N.-K. Hlepas, N. Kersting, S. Kuhlmann, P. Swianiewicz, & F. Teles (Eds.), Sub-municipal Governance in Europe: Decentralization beyond the municipal tier (pp. 119–143). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hlepas, N., & Getimis, P. (2011). Greece: A case of fragmented centralism and ‘behind the scenes’ localism. In F. Hendriks, A. Lidström, & J. Loughlin (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of local and regional democracy in Europe (pp. 410–433). Oxford University Press.

- Hlepas, N., & Getimis, P. (2018). Dimosionomiki Exygiansi stin Topiki Aytodiikisi. Provlimata kai Diexodi ypo Synthikes Krisis [Fiscal consolidation in local self-government. Problems and solutions in a crisis context]. Papazisi.

- Kaufmann, D., & Sidney, M. (2020). Toward an urban policy analysis: Incorporating participation, multilevel governance, and “seeing like a city”. PS: Political Science & Politics, 53(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519001380

- Laiki Syspirosi Municipality of Delta. (2016). Anthropinoi Horoi Filoksenias gia Prosfiges kai Metanastes. Ohi stin Ksenofovia kai to Ratsismo [Humane reception facilities for refugees and migrants. No to xenophobia and racism] [Press release]. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from https://www.oraiokastro24.gr/%CE%B1%CE%BD%CE%B8%CF%81%CF%8E%CF%80%CE%B9%CE%BD%CE%BF%CE%B9-%CF%87%CF%8E%CF%81%CE%BF%CE%B9-%CF%86%CE%B9%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BE%CE%B5%CE%BD%CE%AF%CE%B1%CF%82-%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%B1-%CF%80%CF%81%CE%BF%CF%83/

- Lambert, S., & Swerts, T. (2019). ‘From sanctuary to welcoming cities’: Negotiating the social inclusion of undocumented migrants in Liège, Belgium. Social Inclusion, 7(4), 90–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v7i4.2326

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lowndes, V., & Leach, S. (2004). Understanding local political leadership: Constitutions, contexts and capabilities. Local Government Studies, 30(4), 557–575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0300393042000333863

- Marchetti, C. (2020). Cities of exclusion: Are local authorities refusing asylum seekers? In M. Ambrosini, M. Cinalli, & D. Jacobson (Eds.), Migration, borders and citizenship between policy and public spheres (pp. 237–263). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mayer, M. (2018). Cities as sites of refuge and resistance. European Urban and Regional Studies, 25(3), 232–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776417729963

- Mullin, M., Peele, G., & Cain, B. E. (2004). City Caesars? Institutional structure and mayoral success in three California cities. Urban Affairs Review, 40(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087404265391

- Municipality of Delta. (2016a). Municipal council decision approving emergency funding for school committees to cover security expenses in the municipal communities of diavata and N. Magnisia. (67/2016). Retrieved February 1, 2021, from https://diavgeia.gov.gr/doc/%CE%A9%CE%A6%CE%9B8%CE%A99%CE%99-%CE%A58%CE%92?inline=true

- Municipality of Delta. (2016b). Municipal council decision approving the concession of a municipal building to the Hellenic Police. (83/2016). Retrieved February 1, 2021, from https://diavgeia.gov.gr/doc/7%CE%98%CE%A3%CE%93%CE%A99%CE%99-%CE%91%CE%93%CE%92?inline=true

- Municipality of Delta. (2016c). Ohi sti Dimioyrgia Kentroy Metegkatastasis sto Dimo Delta [No to the opening of a relocation centre in the municipality of delta] [Press release]. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from https://www.dimosdelta.gr/2016/02/08/%cf%8c%cf%87%ce%b9-%cf%83%cf%84%ce%b7-%ce%b4%ce%b7%ce%bc%ce%b9%ce%bf%cf%85%cf%81%ce%b3%ce%af%ce%b1-%ce%ba%ce%ad%ce%bd%cf%84%cf%81%ce%bf%cf%85-%ce%bc%ce%b5%cf%84%ce%b5%ce%b3%ce%ba%ce%b1%cf%84%ce%ac/

- Municipality of Thermi. (2016). Municipal council decision on the opening of temporary refugee reception centre (139/2016). Retrieved August 13, 2020, from https://diavgeia.gov.gr/doc/7%CE%A4%CE%A86%CE%A9%CE%A1%CE%A3-%CE%A6%CE%9E%CE%A7?inline=true

- Nye, J. (2008). The powers to lead. Oxford University Press.

- Oomen, B., Baumgärtel, M., Miellet, S., Durmus, E., & Sabchev, T. (Forthcoming 2021). Strategies of divergence: local authorities, law and discretionary spaces in migration governance. Journal of Refugee Studies.

- Orr, K. (2009). Local government and structural crisis: An interpretive approach. Policy & Politics, 37(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/147084408X349747

- Robinson, P. (2014). High performance leadership: Leaders are what leaders do. Published online: Positive Revolution.

- Rohlfing, I. (2012). Case studies and causal inference: An integrative framework. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sabchev, T. (2021). Against all odds: Thessaloniki’s local policy activism in the reception and integration of forced migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(7), 1435–1454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1840969

- Scholten, P., Baggerman, F., Dellouche, L., Kampen, V., Wolf, J., & Ypma, R. (2017). Policy innovation in refugee integration? A comparative analysis of innovative policy strategies toward refugee integration in Europe. Retrieved October 24, 2018, from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/rapporten/2017/11/03/innovatieve-beleidspraktijken-integratiebeleid/Policy+innovation+in+refugee+integration.pdf

- Sørensen, E. (2020). Interactive political leadership: The role of politicians in the age of governance. Oxford University Press.

- Sotarauta, M., Horlings, I., & Liddle, J. (2012). Leadership and change in sustainable regional development. Routledge.

- Stavrakakis, Y., & Katsambekis, G. (2014). Left-wing populism in the European periphery: The case of Syriza. Journal of Political Ideologies, 19(2), 119–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2014.909266

- Steil, J. P., & Vasi, I. B. (2014). The new immigration contestation: Social movements and local immigration policy making in the United States, 2000–2011. American Journal of Sociology, 119(4), 1104–1155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/675301

- Terlouw, A., & Böcker, A. (2019). Mayors’ discretion in decisions about rejected asylum seekers. In P. E. Minderhoud, S. A. Mantu, & K. M. Zwaan (Eds.), Caught in between borders: Citizens, migrants and humans. Liber amicorum in honour of prof. Dr. Elspeth Guild (pp. 291–302). Wolf Legal Publishers.

- ‘t Hart, P. (2014). Understanding public leadership. Palgrave.

- ‘t Hart, P., & Rhodes, R. A. W. (2014). Puzzles of political leadership. In R. A. W. Rhodes & P. ‘t Hart (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of political leadership (pp. 1–25). Oxford University Press.

- Thermis Dromena. (2016a, Issue 166). 1,162 Syrioi kai Irakinoi, 713 Paidia [1,162 Syrians and Iraqis, 713 Children]. Thermis Dromena, p. 6. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from http://thermi.gov.gr/info/?p=30756

- Thermis Dromena. (2016b, Issue 166). Allilengii pros tous Prosfiges, Asfalia gia tous Katikous [Solidarity with the refugees, safety for the local residents]. Thermis Dromena, pp. 4–5. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from http://thermi.gov.gr/info/?p=30756

- Thermis Dromena. (2016c, Issue 167). Diskolos o Himonas gia toys Prosfiges stoy Kordoianni [Difficult winter for the refugees in Kordoianni]. Thermis Dromena, pp. 6–7. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from http://thermi.gov.gr/info/?p=32661

- Thermis Dromena. (2016d, Issue 168). Ypo to Miden i Thermokrasia kai to Endiaferon tis Politias gia tous Prosfyges sto Kamp tis Thermis [Sub-zero the temperatures and the interest of the state for the refugees in the camp in Thermi]. Thermis Dromena, pp. 9–10. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from http://thermi.gov.gr/info/?p=33058

- TyposThess. (2016, February 29). Thessaloniki: Sto Kentro Prosfigon sta Diavata Dimarchoi tis Polis [Thessaloniki: Mayors from the city in the reception centre of Diavata] Retrieved February 1, 2021, from https://www.typosthes.gr/thessaloniki/91903_thessaloniki-sto-kentro-prosfygon-sta-diabata-dimarhoi-tis-polis-foto

- van Esch, F., & Swinkels, M. (2015). How Europe’s political leaders made sense of the Euro crisis: The influence of pressure and personality. West European Politics, 38(6), 1203–1225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1010783