ABSTRACT

This article approaches the process of opening accommodation centres from the perspective of mayors in rural municipalities. Although the allocation and accommodation of refugees is a competence of the nation-state, it is in the realm of municipalities where reception policies transform into social practices. Mayors have to negotiate socio-political conflicts on the vertical and horizontal dimensions against the background of uneven decision-making structures stemming from multi-governance arrangements and conflicting claims of local citizens. Through qualitative interviews with mayors from rural municipalities in four European countries (Austria, France, Germany and Italy), we show that even though national asylum systems differ, mayors assume similar handling strategies to defuse conflicts and increase acceptance. We introduce the concept of ‘politics of adjustment’ to describe the simultaneous process of people adapting to a new situation as well as the alteration of implementation practices according to the needs of the municipality. Mayors modify the tight legal framework of reception policies to find a local consensus on accommodation, whilst steering the socio-political process of demarcation and othering that leaves imaginaries on rural whiteness and homogeneity unchallenged.

INTRODUCTION

The allocation and reception of refugeesFootnote1 in the European Union has triggered various discussions in recent years around questions of burden-sharing between member states as well as accommodation practices within them (Weinar et al., Citation2018). Both debates – the geographical distribution of refugees and reception conditions – have recurred at the local level. The so-called local turn in migration and integration research draws attention to locally developed policies as well as to gaps between (national) policy goals and (local) outcomes (Adam & Caponio, Citation2018; Caponio & Borkert, Citation2010; Caponio & Jones-Correa, Citation2018; Scholten & Penninx, Citation2016; Zapata-Barrero et al., Citation2017). Although migration policymaking remains a core competence of the nation-state, it is at the level of municipalities that political decisions transform into social practices and where difference and belonging are constructed in locally specific ways (Hoekstra, Citation2018; Yuval-Davis, Citation2006, Citation2007). This is of relevance when looking at the implementation of accommodation centres as they are situated on the territory of the municipality. While some studies have highlighted the ability of the local level to challenge restrictive national frameworks and develop more inclusionary and liberal policies (Cohen, Citation2018; Feischmidt et al., Citation2019), other studies have shown how xenophobic attitudes prevail and exclusionary mechanisms of reception systems are reinforced (Ambrosini, Citation2013; Castelli Gattinara, Citation2018).

Scholarship in migration and integration research has focused primarily on the role of cities and urban regions (Bauder, Citation2017; Caponio et al., Citation2019; Oomen et al., Citation2016) while the body of literature on rural and peripheral areas is still developing (Glorius, Citation2017; Kordel et al., Citation2018; Larsen, Citation2011; Miellet, Citation2019; Schammann et al., Citation2020; Whyte et al., Citation2018). In view of the various facets of localness, this paper seeks to shed light on the role of mayors in the process of opening accommodation centres for refugees in rural municipalities. Rural areas differ from cities in three important aspects: (1) they often have no or little infrastructure for and prior knowledge of refugee reception; (2) local policymaking is characterized by a high degree of personalization, pointing to the political relevance of the role of the mayor; and last but not least (3) rurality as a socio-spatial imaginary is frequently constructed as a culturally homogenous space characterized by neighbourliness and tranquillity that serves as the antithesis of the heterogeneous and disordered city (Panelli et al., Citation2009).

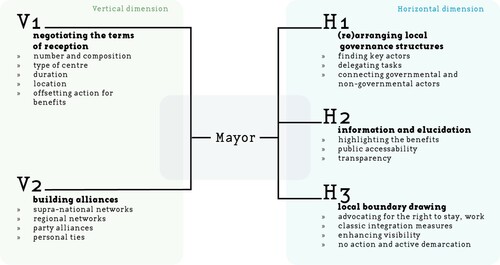

In rural municipalities, the mayor acts as a central node in the process of opening an accommodation centre. S/he is at the intersection between local demands and administrative tasks on the one hand (the horizontal dimension) and regional and national politics on the other (the vertical dimension). In this context, the role of mayors in rural municipalities is particularly interesting as they act both as municipal agents holding political office, and as inhabitants of the municipality who are directly confronted by changes in the neighbourhood and are possibly acquainted with practically everyone in the municipality. In the person of the mayor, horizontal and vertical conflicts of interest converge, and mayors have to mediate opposing demands of the electorate for or against the reception of refugees as well as political obligations embedded in uneven decision-making structures.

Through a comparative, qualitative research on rural municipalities in four European countries, Austria, France, Germany and Italy, we identify similarities in dealing with the opening of an accommodation centre despite national differences and show that even though national asylum systems differ, rural mayors adopt similar handling strategies. We present the five handling strategies that take place on two dimensions (vertical and horizontal) in the empirical section of the paper and introduce them under the concept of politics of adjustment. We understand adjustment as a two-way process that considers the ability of local actors to adapt to a new situation while at the same time modifying framework conditions in local terms. In this process of socio-political change, mayors make use of their capacity to resolve conflicts, facilitating the acceptance of moderate changes in community life while ensuring the continued integrity of rural areas. These actions target solely the citizens of the municipality and do not address the needs of refugees.

Based on our material, we argue that restrictive and liberal approaches in dealing with the opening of an accommodation centre ought not to be pictured as a dichotomy but as concurrent and cross-fertilizing. Rural municipalities only very marginally overstep their jurisdictional boundaries and, although taking a critical stance on certain topics, comply largely with state measures and reinforce disintegrative characteristics of the centre while demanding the inclusion of a limited number of refugees. The concept of adjustment thus draws on literature that talks of local immigrant policies as being ‘specific in their approach of problem solving’ (Zapata-Barrero et al., Citation2017, p. 3) and on the one that analyses the legal, social and political limits of local reception processes (Glorius, Citation2017; Kreichauf, Citation2018).

IDENTIFYING THE ROLE OF MAYORS IN RURAL RECEPTION PROCESSES

To answer the research question on how rural mayors have dealt with the opening of an accommodation centre and how they have navigated vertical and horizontal conflicts of interest, we build on three strands of theory: (1) we delineate particularities of local level migration policymaking from a multilevel governance perspective; (2) we identify the role of mayors as they navigate these conflicts; and (3) we outline rural reception realities to elucidate the characteristics of the specific context in which mayors deal with the opening of an accommodation centre.

The local level in a multilevel governance structure

Regardless of the political system, the field of asylum and migration policies in all European member states is characterized by a high degree of centralization, excluding the local level from the decision-making process. While regulations on aspects such as distribution mechanisms and forms of accommodation are enacted by national and state governments, their implementation draws on local governance structures that enjoin different actors from the governmental and non-governmental domain. In practice, this means that municipalities have a limited scope of action when it comes to decision-making whilst being confronted with a variety of different actors with conflicting interests. On a vertical dimension, multilevel governance pertains to conflicting interests of the local, the regional, the national and the supra-national (Scholten & Penninx, Citation2016).

Scholars in migration and integration research have pointed out options of locally developed migration policies despite centralized power relations (Caponio & Borkert, Citation2010; Filomeno, Citation2017). For example, studies that have analyzed municipal activism on illegalized or irregular migrants reveal that the local level should not be reduced to a mere executive force (Doomernik & Glorius, Citation2016; Kos et al., Citation2016; Spencer & Delvino, Citation2019). In the context of little legal flexibility and a high degree of centralization, municipalities make use of jurisdictional and institutional gaps, discretionary powers, or deliberately overstep jurisdictional boundaries and openly challenge supra-local authorities. It is this dissonance between policy formulation and its implementation that lies at the core of research on local level policies, and which frequently results in processes of decoupling (Scholten, Citation2016).

Within the domain of the municipality, local policymakers are situated in a relationship with local governmental actors, such as citizens, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), service providers and others (Campomori & Caponio, Citation2017). This diversification of actors within the field of reception policies increases the complexity of local modes of governance. Multiple public and private actors are involved, conjoining vertical and horizontal interests (Schiller, Citation2018). Responsibility is shifted ‘out’ and ‘down’ (Campomori & Caponio, Citation2017). In other words, competences, power and knowledge are stratified, and decision-making authority is contested. State and non-state actors are interconnected and define the parameters of local reception policies (Schiller, Citation2018). In this regard, the mayor acts as nodal point, balancing different interests in a field of unequal power relations.

The mayor at the intersection of vertical and horizontal interests

The lack of decision-making power in asylum policies may cause problems for mayors and their local governments in terms of autonomy, accountability and sustainability. Mayors must account to their voters while at the same time their scope of action is limited by the government’s regulations (Bealey & Johnson, Citation1999). This situates the mayor in a field of tension between political and moral obligations, representation and responsiveness to his/her own community as well as personal preferences. Mayors operate in this field of tension by (1) representing the needs, demands and concerns of the municipality; and (2) responding to needs, demands and concerns of citizens. Here, a conflict arises between the maintenance of power and the exercise of power (Copus, Citation2010).

The local political level tends to invite more trust and legitimacy than the regional or national one, a fact explained by the proximity of the electorate to its political representatives and political projects (Dahl & Tufte, Citation1973; Denters et al., Citation2014; Fitzgerald & Wolak, Citation2016). Local politicians spend more time in meeting citizens and foster modes of direct participation in the decision-making process (Haus & Sweeting, Citation2006). In particular, the mayor is often associated with a high level of charisma and leadership qualities (Le Bart, Citation2003; Headlam & Hepburn, Citation2017). This high degree of personalization in local politics is supported by the fact that local politicians tend to be perceived as ‘non-political’ and candidates often establish a non-partisan profile (Fallend, Citation2006; Magnier, Citation2006). This is even more true for small and rural municipalities, as rural decision-making processes are different from those in urban areas: while policymakers in cities rely on formal bureaucratic structures with a significant distance to their citizens, in small-scale environments it is not possible to compartmentalize decisions in distinct spheres, instead political and administrative tasks merge (Jacob et al., Citation2008).

Research has illustrated the complexity of administrative practice and the inevitability of value conflicts in public administration (Wagenaar, Citation1999, Citation2004). Here, value conflicts not only pertain to the political orientation of the mayor but reflect his/her social embeddedness in the municipality and his/her affectedness as a possible neighbour of the accommodation centre. In a critical moment, such as the opening of an accommodation centre, the mayor navigates the two ends in trying to meet the needs of his electorate, exercising decisional and administrative power on how to manage the situation and balance personal preferences. To do so, mayors develop a range of strategies geared towards the vertical and the horizontal level to adjust to the new situation.

Reception realities in rural regions

Material reception conditions define the spatial, temporal and social limits of accommodation centres and have frequently been described as disintegrating and structurally exclusionary (Collyer et al., Citation2020; Haselbacher & Hattmannsdorfer, Citation2018; Kreichauf, Citation2018; Täubig, Citation2009). The specific arrangement of national asylum laws results in the forced inactivity of refugees, who spend an indefinite length of time waiting for the decision on their asylum application. In practice, access to the labour market and to education or training are reserved for successful applicants of international protection (Kreichauf, Citation2018). Structural barriers embedded in the legal and administrative framework of the accommodation centre impede active participation in community life. For asylum-seeking refugees, this results in a social standing somewhere between (new) members of the community and temporary guests that are not genuinely associated with the municipality.

Studies on rural reception realities have shown how the lack of institutions and infrastructure makes access to services and mobility key issues in counterbalancing the seclusion of rural geographies (Glorius, Citation2017; Scheibelhofer & Luimpöck, Citation2016; Weidinger et al., Citation2019). Local integration measures in rural contexts further govern the inclusion and exclusion of refugees in the municipality (Adam & Caponio, Citation2018; Haselbacher, Citation2019; Kos et al., Citation2016). On the one hand, refugees are considerably more dependent on services offered by the local community as other networks they could turn to are missing. On the other hand, rural municipalities, in cooperation with other local actors, provide services that go beyond the regular scope, for example, driving services, language courses, etc. In contrast to cities, rural municipalities cannot resort to prior knowledge and experiences in refugee reception, therefore mayors cannot rely on existing infrastructure but have to build these infrastructures on short notice. Moreover, ‘rural’ as a socially constructed category often goes along with the idea of a homogeneous autochthone population in contrast to (racialized) newcomers. Local strategies of boundary drawing that aim to preserve an imagined homogenous rural community are deeply rooted in the construction and the preservation of whiteness (Hubbard, Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Panelli et al., Citation2009) even when new dynamics are generally welcomed (Woods, Citation2018). This self/other divide is present in the way in which local politicians, along with their electorate, manage the arrival of refugees in their municipality and negotiate inclusion/exclusion in rural environments.

To sum up, we first outlined the role of the local level in the context of reception policies. Then we identified particularities in the role of (rural) mayors in policymaking. The local level lacks decisional power, a result of unequal vertical decision-making structures. Rural municipalities usually do not have the infrastructure, resources and knowledge available in cities. Furthermore, the exclusionary and disintegrative legal framework of accommodation centres structurally impedes inclusionary approaches and positions newcomer refugees as disruptive elements, outside of the local community. This provides the analytical framework for our empirical analysis, where we conceptualize mayors as the central node in local negotiation processes and analyse their strategies to deal with the opening of an accommodation centre.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

To be able to assess the research question and handle country- and case-specific differences, we chose a comparative actor-based approach. This allows taking into account the institutional set-up of refugee reception at local level, as well as the positioning and the handling strategies of the mayor as a key actor. Through this double perspective as a framework for analysis (Mayntz & Scharpf, Citation1995), we are able to grasp actions, decisions and strategies of mayors without neglecting the institutional and social circumstances in which they are embedded. Based on four qualitative in-depth case studies in each country (Austria, France, Germany and Italy), our research goal was to identify similarities in actor behaviour despite contextual differences. Although it is a challenge to narrow down the multiple contextual framing necessary for comparison, a qualitative approach with a small number of cases seemed more apt to investigate similarities in actor behaviour in a policy field that is marked by structural differences (Mosley, Citation2013; Gerring, Citation2007). We thus studied the process of opening accommodation centres through the narrations of mayors in the four countries. Referring to views expressed by local policymakers has strengths and limitations: they reflect their understanding of the situation and their role in shaping the events, but we are aware that, outside the interview setting, discourses might differ.

Case selection and approach

The case selection was based on rurality as a spatial concept (Vittuari et al., Citation2020). All selected municipalities have no more than approximately 5000 inhabitants and a density of fewer than 300 inhabitants/km², the official definition of rurality by the European CommissionFootnote2 (for details on cases, see ). In all selected municipalities, a collective accommodation centre was opened between 2014 and 2019. We focused on cases where the opening of the accommodation centre, albeit met with resistance, did not lead to major protests. This choice corresponds with the research interest to look at cases which are representative for rural reception processes and which have been successfully implemented despite sporadic local resistance. To reduce inner-country variance, we decided to focus on one region in each country (Bavaria in Germany,Footnote3 Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes in France, Veneto in Italy), with the exception of Austria, where we conducted two interviews each in the two smallest federal provinces (Burgenland and Vorarlberg). These prescribed selection criteria permit inter-country comparison despite national differences.

Table 1. The 12 municipalities under study.

In a first step, we identified municipalities that fit the selection criteria via internet research based on newspaper reports and statistical data. In a second step, we contacted mayors via email or phone. All interviews were conducted in the mother tongue of the mayor (French, German or Italian) and translated by the authors. The interviews were conducted either in person in the office of the mayor or by phone and digitally recorded. In addition to a non-response of around 50% in each country, one challenge was to identify municipalities which met the selection criteria, as the number of accommodation centres in rural areas varies significantly between the countries and information on the location of centres is scarce. We also collected supplementary material, such as media accounts, municipal bulletins, local council protocols and conducted interviews with other key actors to generate case files that contextualize the cases. However, our main source were the interviews of the mayors. Interviewees were offered anonymity, including on the name of their municipality, interviews are therefore cited with the first letter of the country and a number: A for Austria, F for France, G for Germany and I for Italy.

The interview guidelines touched upon four thematic blocks based on the literature and the research questions: (1) the opening of the accommodation centre, (2) the role of the mayor, (3) cooperation and conflict with other actors, and (4) organization of reception in the everyday life of the municipality. Through these four thematic blocks we were able to trace the opening of the accommodation centre up to its establishment to learn how rural mayors understand their role in this process and their adjusting actions towards consensus-building. The interview material was then coded with atlas.ti. A first set of general deductive codes derived from the four thematic blocs targeted specifically vertical and horizontal conflicts of interests. In a second round, we condensed the codes and inductively developed five strategies in cross-country and cross-case comparison.

Comparative aspects: country information and framework conditions

The comparison between the four countries suggests a bisection between Austria and Germany, on the one hand, and France and Italy, on the other, which can be related to the political systems and different experiences with refugee migration. outlines some of the major differences.

Table 2. Contextual information of the country sample.

First, the political system and consequently the division of tasks and competencies at the local level diverge. France and Italy present similarities and have frequently been described as continental–Napoleonic systems (Kuhlmann & Wollmann, Citation2013). Here, the ‘political mayor’ only has few formal competencies, little legal discretion, and good access to central and regional levels of government (Bäck et al., Citation2006). France is a highly centralized country where municipalities are rather weak and administrative competencies are bundled at the regional level (Denters, Citation2011, p. 324). The mayor is able to hold multiple offices (cumul de mandat) and can thus increase his/her power and competencies. Although not elected directly, the winning list is granted a majority. In Italy, structural features of local government are similar to France, with the exception that party politics and clientelism are more important. Although Italy is also a centralized country, the process of administrative decentralization has revaluated the role of municipalities. Italian mayors are elected directly and share executive powers with higher levels of government, where both regions (regioni) and provinces (province) have high administrative powers (Kuhlmann & Wollmann, Citation2013). In contrast, Austria and Germany have a political system where mayors are ‘executive’ leaders, that is, they formally head the municipal administration, are responsible for a broad range of public provision and enjoy a high level of discretion (Bäck et al., Citation2006; Heinelt & Hlepas, Citation2006). Mayors have great executive powers and are legitimated through direct election. Municipalities traditionally have a wide range of responsibilities and play a central role in the provision of services. In the federal architecture of both countries, administrative tasks are divided and municipalities carry out the implementation of federal and state legislation.

Second, the four countries have developed distinctive approaches to asylum policies and refugee accommodation. For Austria and Germany, 2015 marked a turnaround in terms of responsibility, as neither country had accommodated large numbers of refugees since the introduction of the Schengen and Dublin system. The number of asylum applications in shows how the number of asylum applications varies between the countries and has changed over the investigation period. All countries fixed distribution ratios to disperse refugees across the territory,Footnote4 which are hardly ever realized in practice. More importantly, the reception capacities are much lower in France and Italy, which results in a high number of refugees without shelter and the development of informal makeshift camps. Austria and Germany, on the other hand, have only few cases of homelessness, which are related mostly to the withdrawal of basic care, and many of the centres that opened before and after 2015 are vacant or have already been closed down (AIDA, Citation2019).

Accommodation policies and practices vary substantially in the four countries. Each has a variety of different forms of accommodation. In Italy, the four facilities are Centri di accoglienza straordinaria (CAS), extraordinary (emergency) accommodation centres. In France, all four centres are Centre d’accueil de demandeurs d’asile (CADA), which means regular accommodation centres (AIDA, Citation2019). Both countries have in common the fact that the prefecture can set up the centres without the need for approval from the municipality. In Austria two centres were managed by private providers (former hoteliers) and two centres were managed by NGOs, similarly in Germany where refugees are lodged either in collective accommodation of the municipality or by individual citizens in so-called decentralized accommodation.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS: NAVIGATING VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL INTERESTS

The opening of an accommodation centre initiates a period of change that is marked by uncertainty (Horst & Grabska, Citation2015). In the light of uneven decision-making competences, mayors make an effort to advocate the interests of local citizens in the process of implementation in order to establish a local consensus. presents five strategies mayors use to navigate conflicts on the vertical and horizontal dimensions that we discuss below under the term ‘politics of adjustment’. We understand politics of adjustment as a way of accommodating change that comprises two aspects: it is the process of people adapting to a new situation as well as the alteration of implementation practice by local actors. In view of differing attitudes and demands, the main concern of local policymakers is to defuse conflicts and increase acceptance, as the following quotes show.

I think it’s a fundamental role. To make the population accept, if the mayor is against it, it is not going to work out. (F_1)

My main concern was to keep public order and channel the hate and the resentfulness. (I_1)

And again, it’s a very important signal, of course it’s a contentious topic and there are people who are overwhelmed by the fast pace of the situation … , but for that we have the mayor who tries to soften anxieties … , as I say, like in many other areas, I am the representative in this matter. (A_2)

Figure 1. Vertical and horizontal strategies of mayors in managing the reception of refugees. Source: Authors’ illustration.

The majority of measures taken by mayors target the horizontal dimension and pertain to three areas: the organizational structure of local governance settings (H1), the communication with citizens of the municipality (H2) and modes of local boundary-drawing that govern the inclusion/exclusion of refugees (H3). On a vertical level, mayors are primarily engaged in negotiating the terms and circumstances of reception (V1) and make use of their personal and political ties to lobby their interests (V2). While, in cross-case comparison, mayors may privilege one strategy over another, all strategies are present in the four countries and represent prototypical patterns of actions. In the following, we provide empirical insights into strategies on the vertical dimension and the horizontal dimension, before pointing out explanatory factors and elaborating the concept of politics of adjustment.

Managing vertical interests

Although most of the interviewed mayors expressed disappointment on how the implementation has been carried out and criticized their exclusion from the decision-making process, they made efforts to negotiate a formula that could be presented to the citizens (V1). For this purpose, the framework conditions of the accommodation centre were renegotiated. This included the number of incoming refugees, their composition (e.g., families), the duration of the contract, the location or the type of reception. Hence, mayors decided to comply with the overall decision to open an accommodation centre but intervened to modify the terms and conditions. In all countries, mayors were able to make changes. Most municipalities expressed a preference for families rather than young (Muslim) males, exposing racialized notions of foreign masculinities (Scheibelhofer, Citation2012):

We asked to accommodate families rather than single men … so now, we do not only have families, we also have couples and singles, but the majority are families. The service provider has played along. (F_2)

If you calculate it, we are 8,000 municipalities in Italy and there are 200,000 arrivals. If you divide this by 8,000, that makes 25 people per municipality. That would not be a problem … but here we can see that this is being mismanaged. (I_2)

That would be ill-conceived, a forced allocation of masses. It would have been strenuous for the local population if there were suddenly 50 to 60 people, in the beginning they planned to put even 80. And suddenly you would have them all in your village with only slightly more local inhabitants. (A_3)

To regain control over the reception process, some municipalities took a proactive stance and either bought the respective building or provided municipal infrastructure for the reception:

I think that not every municipality would have done it the way we did. … Taking 150,000 Euros and renovating the house in such a way that I myself would move in too. … And now, if we feel that something needs to be done, I don’t negotiate for months and weeks with the provincial government or other institutions, we just do it. (A_2)

I provided some flats from the municipality, because I wanted it to be organized by the municipality and not by some private landlord. (F_3)

Retrospectively it was the right way to look for a partner who assumes the supervision of the unaccompanied minors and to make the municipality owner of the property. … Once it belongs to the public administration, it is possible to control it and to take into account the preferences of the citizens, a private investor from the outside wouldn’t have cared. (G_3)

With the opening of the accommodation centre, we asked the authorities for a community car that could also be used to transport disabled people, this was beneficial for the whole municipality, for the citizens and for the needs of the refugees. (I_4)

At the start of the next school year, we had 60 children and we could maintain one teaching position from the ministry of national education. They have been very attentive to the project and we could get another half-post just for the children of the CADA, to learn the language. (F_1)

Unfortunately politics do also divide mayors, because those mayors who do not have any centre do not want to take a share. And the will of the electorate goes in the direction that has been initiated by the League (political party), which is hostile, and no one wants to lose their electorate. (I_2)

I am not CSU at all. I am completely neutral. But yes, it is complicated, and you can feel it and they [the Bavarian government] let you feel it. (G_1)

We had regular mayor meetings in the district office, where we all gathered, and we talked about how each of us is organized. (G_2)

We participated in the call for this European project on best practice in the reception of migrants in Europe … together with five European partners … we have organized conferences and also meetings with other actors from the region because I wanted to extend this project to the whole province. (I_1)

Managing horizontal interests

At administrative level, mayors rearranged local governance structures, delegated tasks and identified key actors (H1) in order to assume an auxiliary and monitoring role, without losing access to information. This rearrangement of local governance structures connects the administrative core of the municipality with local support groups, resulting in the creation of formal and informal networks of members of the municipal council, employees, NGOs, other local organizations (such as associations or religious bodies), volunteers and sometimes refugees themselves (Campomori & Caponio, Citation2017; Hinger et al., Citation2016). In Italy and France, mayors particularly highlighted the role of volunteers and NGOs, where, in Italy, the Roman Catholic Church played a distinctive role in all cases.

As I said, we are a small municipality … , let’s say we rely heavily on associations that manage all the services we are not able to provide. If we would not have all the volunteers and would have to pay people for that work, we could not do it at all. (F_5)

There are no activities, but our parish, together with the one in the neighbouring municipality, they do activities inside the camps, and the Christian refugees go to mass. The parish has also done some integrational projects and shown films on the topic and invited people to tell their stories. (I_2)

I had this lady, she was in the financial administration and she took care of the refugees, as civil servant and privately, she was very committed. (G_2)

I did all the communication myself, externally and internally, with my local citizens, always the latest news, what was happening in the municipality. They needed to know that they were taken care of because I did not cause this situation, I could only react, otherwise I wouldn’t have a chance. And that was my part in it. (A_1)

I was informed by the prefect at half past nine, and at eleven, the first people arrived … he said, it is like that. We didn’t know how many people would come, but it could be hundreds. So the citizens started to be furious. Every day I met people, I answered phone calls and e-mails … all the emergency I had to handle and to mediate … . (I_4)

First through the local gazette, then directly after I organised a citizens’ council … and, of course, the classic citizen consultation hours. As mayor in a small municipality, you are always available all the time, yes, and in the first days (note: at the opening of the centre) with 2,000 inhabitants, I guess I reached 80% of the citizens personally. (G_3)

This created two jobs in the municipality, and here employment is scarce and with the children we could save one school class from closing down, and those people use the post office, the pharmacy, associative activities, that is important in rural areas. (F_1)

The topic work. I intervened to organize employment for them (the refugees), to not let them work merely at the municipal building yard, but to employ them in local companies with a shortage of skilled workers. … I was head-hunter and counselled each one of them myself. (G_3)

It is an opportunity … , one refugee now works in a hotel in our municipality … as an apprentice, perfect! The hotel owner is really impressed by him. This is a textbook example for me … and if something like that happens, it is really valuable. (A_4)

When the first people arrived, we organized a get-together at the town hall to welcome the people and let them meet the locals. There was some motivation, and then, after six months, people started to leave and others arrived and we had to start all over again … and now people are tired and the CADA is now in its own corner. (FR_1)

That they (the refugees) are being integrated if possible, that they become part of our structures and that this really works. If they join the Judo club or the local football club … , the kids ultimately all ended up in one of the local clubs, that was very valuable. (A_4)

There were around seven to ten individuals who took care of the refugees. We once organized a get-together … , they cooked for us and we ate together and it was very enjoyable. (G_2)

We have deployed asylum seekers living in the community, making them visible through self-printed T-shirts with the name of the municipality, to show the local population that they are not only here to take our things but to give something back to the community. (A_2)

In the beginning, the citizens protested, but after two/three months, when the refugees started to do the voluntary work, cleaning the streets, maintaining the green areas in the municipality, they [the inhabitants] also saw the positive impact. (I_4)

Direct contact, like common integration measures, we didn’t have that. There was a kind of distance. (A_3)

No, we have no details of the accommodation, they (the refugees) come, they go, sometimes there is one in the municipality because their application got rejected … then there are organizations that take care of them, but I don’t know how that works, I have no information about that. (F_4)

And the laws that exist have to be enforced. I have talked a lot with the support groups and told them not to invest in personal ties. It is hard … but it is important, when the law says someone needs to be deported, then we have to accept it. And we also have to accept it, when somebody is allowed to stay, then we have to help. (G_2)

Of course, not everyone obtained a right to stay … but here, we as municipality didn’t intervene … we lacked knowledge and information and I also told the asylum group (group of volunteers) again and again to maintain relationships on a level where it does not become a burden if a negative decision is issued in the course of an asylum application, we have to accept it and stand by the mechanisms in the background even though it might hurt … ; that worked well. (A_1)

We have to organize cheap accommodation, where they can stay. It can’t be, I think, that they get luxury flats. It shouldn't be like that and they don’t expect that either. It wouldn’t make sense, because we have seen that here, they are clean, but the tidiness is an issue, they are not familiar with it as we are … . (A_1)

We have all types of populations, Ukrainians, Africans, Syrians, Libyans, … I would say the only problem are the Roma families, they do not have a very high level of education and they have problems to integrate in western civilization. (F_2)

Yugoslavia, it must be said, they are not so extremely different to Austria, in their mentality, you know. That is what we must realise, that it is just easier than if they are coming from Syria, Iran, Iraq and so on. (A_4)

Explaining differences and similarities

Although both dimensions – the vertical and the horizontal alike – are decisive in shaping rural reception realities, we here point out some particularities which form an integral part of politics of adjustment: (1) all strategies are present in the four countries, however they manifest more differently in the vertical dimension, which can be linked to the deprivation of decision-making power at the local level and contextual differences of the political systems described above; (2) similarities on the horizontal dimension can be explained best by the characteristics of local policymaking in small-scale environments and reception realities in rural regions; and (3) all strategies target first and foremost the citizens of the municipality in order to establish a local consensus while the voice of refugees remains unheard.

In Italy and France, where governments frequently used emergency accommodation to enforce a top-down approach, the mayoral scope to negotiate terms and conditions was very limited. This also resonates with the specific configuration of unitary states, widening the gap between policy formulation and its implementation. Mayors had little access to policymakers at higher political levels and were only partially able to renegotiate the terms of the reception. To make up for that, Italian and French mayors were more successful in negotiating benefits for the municipality and searched for alliances outside the national political context.

In Austrian and German municipalities, the exceptional situation of 2015 was a decisive moment that made trans-municipal solidarity a topic, to assure that everybody could be held accountable for their share of accommodation. Accommodating refugees was thus not as exceptional anymore and the search for new places as well as the exchange of best practice models was an integral part of institutionalized mayoral meetings in the provinces and districts. In both countries, well established channels of federal negotiation processes were moreover used to manage the dispersion and accommodation of refugees. Here, mayors made use of political ties in the realm of party politics or on a vertical scale with people holding administrative and legislative offices in superior political levels. In this context, mayors were able to either alter reception conditions in the interest of the municipality or to gain knowledge on how to manage the reception process.

Interestingly, the party ideology of the mayor did not play a decisive role, as left-leaning and conservative mayors employed both inclusionary and exclusionary measures within the municipality. The majority of mayors at local level and in our sample is conservative or right-leaning, which did not seem to have an impact, as most mayors take a different stance than national parties and criticize them. This deviation from official party ideology at local level was facilitated by the high degree of personalization of local politics. However, in all countries, the electoral success of the extreme right – respectively, Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Rassemblement National (RN), Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and Lega – was an issue of concern that put mayors under pressure. To sum up: cross-case comparison reveals that the self-positioning of the mayor, transparency and proactive communication strategies were decisive in shaping local reception realities and that party ideology of the mayor – unlike party ties as discussed above – played a subordinate role.

Strong similarities and the dominance of horizontal strategies can best be explained by structural features of rural municipalities, such as the lack of infrastructure and knowledge with regard to reception policies, and particularities of local policymaking in small-scale environments. Mayors have a larger room of manoeuvre on the horizontal dimension and are interested in finding a consensus in order to consolidate their power. Amid the establishment of local policies without prior knowledge of accommodation processes, mayors have to be responsive and take into account the preferences of the citizens. The development of a local consensus in rural municipalities thus follows a pattern guided by personal interaction between citizens and their political representatives who advocate the interests of the community. Infrastructure has to be built ad-hoc and most often from scratch without professional guidance, this is of particular importance as refugees depend on these infrastructures to overcome disintegrative features of rural reception realities.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS: POLITICS OF ADJUSTMENT

Our findings have pointed out particularities of rural reception processes. Urban mayors, in particular mayors of big cities, can by-pass multilevel constraints because of their political weight and the configuration of local governance arrangements. Furthermore, they can draw on existing infrastructure and knowledge in migration and integration policymaking (Caponio & Jones-Correa, Citation2018). Rural mayors are confronted with different conditions. In view of the deprivation of decision-making authority regarding the overall decision to open an accommodation centre, rural mayors make use of legislative gaps and their administrative powers to adjust the framework conditions according to local preferences. While mayors (re)act based on the preferences of their electorate and their personal beliefs, the voices and interests of refugees are rendered invisible.

Inclusionary and exclusionary actions as well as the demarcation of boundaries that govern the access of refugees to different spheres of the municipality become key elements of politics of adjustment. It is thus the intent to modify the tight legal framework of reception policies according to the needs of the municipality, and to steer the socio-political process of demarcation and othering that leads to a redefinition of rural whiteness and community space (Hubbard, Citation2005a). In this context, rurality is not a geographical and spatial definition, but a social and cultural construct which is ‘the normative and often unspoken category against which all other racialized identities are marked as Other’ (Dwyer & Jones, Citation2000, p. 210). The invisibility of refugees and racist practices become normalized and integration paradigms as well as refugees’ conformity with local practices the normative power.

The handling strategies described above resemble a rather assimilationist understanding of integration. They aim at including a small number of new community members who ideally settle for the long term. Unpaid voluntary work and efforts refugees make to fit in, become a crucial part in assessing their willingness and deservingness (Chauvin & Garcés-Mascareñas, Citation2014; Hinger, Citation2020), a highly selective process that is strengthened through exclusionary characteristics of accommodation practices (Kreichauf, Citation2018; Segarra, Citation2020). This is reinforced by transience of rural reception; first, most often refugees return to urban areas as soon as their asylum application has been accepted or rejected, as they are no longer entitled to material reception conditions, while job opportunities or housing is scarce. Second, many of the accommodation centres in rural areas are conceptualized as temporary: more than half the centres included in our study have been closed since. In practice, this means that long-term change in the perception of rural homogeneity and a full integration of the accommodation centre into community life are rare.

In this context, mayors in all four countries have criticized the nation-state and have made an effort to implement their own distinctive policies that are not based on legal status categories but on the participation of refugees who are viewed as a potential resource and future members of the municipality (Hinger, Citation2020). Although municipalities show tendencies of decoupling (Scholten, Citation2016) following their own rationale, they hardly overstep the jurisdictional boundaries and assume the integration imperative from the nation-state. These insights soften the apparently antithetical view of local and national approaches. Instead, we argue here that local adjustment comprises both aspects: the contestation and the constitution of dominant paradigms. The concept of politics of adjustment expands on this field of tension. To settle and resolve the situation, the mayor relies on two concurrent strategies: S/he tries to soften disintegrative measures of material reception conditions in order to secure continuity in the daily life of the municipality while relying on exclusionary aspects of the accommodation centre to continuously draw the boundary between citizens of the municipality and refugees.

To close, we want to point out some connecting points for further research: (1) including a larger sample to refine the concept of politics of adjustment and (2) analysing whether the concept is applicable in other demographic areas such as cities to develop more distinctive explanations on differences and similarities in rural and urban areas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their critical and thoughtful remarks. We also thank our supervisor, Sieglinde Rosenberger, and colleagues from the writing group at the Department of Political Science, Barbara Prainsack, Lukas Schlögl, Mirjam Pot and Reinhard Schweitzer, for their very helpful comments and fruitful discussions. This article was realized with support from the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Vienna.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 We use the term ‘refugee’ to refer to all individuals seeking protection regardless of their legal status. Thus, it includes individuals whose application for international protection is still pending, those already granted a status or those whose application was rejected and who are illegalized.

3 In Bavaria, we focused on the two districts of Oberpfalz and Niederbayern.

4 In Italy, the piano nazionale di ripartizione; in France, the plan national d’accueil; the Grundversorgungsvereinbarung in Austria; and the Königssteiner Schlüssel in Germany.

REFERENCES

- Adam, I., & Caponio, T. (2018). Research on the multi-level governance of migration and migrant integration: Reversed pyramids. In A. Weinar, S. Bonjour, & L. Zhyznomirska (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of the politics of migration in Europe (pp. 26–37). Routledge.

- AIDA, Asylum Information Database. (2019). Housing out of reach? The reception of refugees and asylum seekers in Europe. https://asylumineurope.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/11/aida_housing_out_of_reach.pdf (last accessed 03.02.2021).

- Ambrosini, M. (2013). ‘We are against a multi-ethnic society’: Policies of exclusion at the urban level in Italy. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(1), 136–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.644312

- Bäck, H., Heinelt, H., & Magnier, A. (Eds.). (2006). The European mayor: Political leaders in the changing context of local democracy. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Bauder, H. (2017). Sanctuary cities: Policies and practices in international perspective. International Migration, 55(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12308

- Bealey, F., & Johnson, A. G. (1999). The blackwell dictionary of political science: A user’s guide to its terms. Blackwell Publishers.

- Campomori, F., & Caponio, T. (2017). Immigrant integration policymaking in Italy: Regional policies in a multi-level governance perspective. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(2), 303–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852315611238

- Caponio, T., & Borkert, M. (Eds.). (2010). The local dimension of migration policymaking. Amsterdam University Press.

- Caponio, T., & Jones-Correa, M. (2018). Theorising migration policy in multilevel states: The multilevel governance perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(12), 1995–2010. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341705

- Caponio, T., Scholten, P., & Zapata-Barrero, R. (Eds.). (2019). The routledge handbook of the governance of migration and diversity in cities. Routledge.

- Castelli Gattinara, P. (2018). Europeans, shut the borders! anti-refugee mobilisation in Italy and France. In D. della Porta (Ed.), Solidarity mobilizations in the ‘refugee crisis’ (pp. 271–297). Springer.

- Chauvin, S., & Garcés-Mascareñas, B. (2014). Becoming less illegal: Deservingness frames and undocumented migrant incorporation. Sociology Compass, 8(4), 422–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12145

- Cohen, S. (2018). Populism is not the only trend. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 31(4), 329–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9285-y

- Collyer, M., Schweiter, R., & Hingers, S. (2020). Politics of (dis)integration – an introduction. In S. Hinger & R. Schweitzer (Eds.), Politics of (Dis)Integration (pp. 1–18). Springer.

- Copus, C. (2010). The councillor: Governor, governing, governance and the complexity of citizen engagement. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 12(4), 569–589. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2010.00423.x

- Dahl, R. A., & Tufte, E. R. (1973). Size and democracy. Stanford University Press.

- Denters, B. (2011). Local governance. In M. Bevir (Ed.), The sage handbook of governance (pp. 313–329). Sage.

- Denters, B., Goldsmith, M., Ladner, A., Mouritzen, P. E., & Rose, L. E. (2014). Size and local democracy. Edward Elgar.

- Di Cecco, S. (2020). En italie, le sale boulot de l’intégration. Plein Droit, 126(3), 32–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3917/pld.126.0034

- Doomernik, J., & Glorius, B. (2016). Refugee migration and local demarcations: New insight into European localities. Journal of Refugee Studies, 29(4), 429–439. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/few041

- Dwyer, O. J., & Jones, J. P. (2000). White socio-spatial epistemology. Social & Cultural Geography, 1(2), 209–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360020010211

- Fallend, F. (2006). Divided loyalties? mayors between party representation and local community interests. In H. Bäck, H. Heinelt, & A. Magnier (Eds.), The European mayor: Political leaders in the changing context of local democracy (pp. 245–270). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Feischmidt, M., Pries, L., & Cantat, C. (Eds.). (2019). Refugee protection and civil society in Europe. Springer.

- Filomeno, F. (2017). Theories of local Immigration policy. Springer/Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fitzgerald, J., & Wolak, J. (2016). The roots of trust in local government in western Europe. International Political Science Review, 37(1), 130–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512114545119

- Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge University Press.

- Glorius, B. (2017). The challenge of diversity in rural regions: Refugee reception in the German federal state of saxony. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 66(2), 113–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15201/hungeobull.66.2.2

- Haselbacher, M. (2019). Solidarity as a field of political contention: Insights from local reception realities. Social Inclusion, 7(2), 74–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v7i2.1975

- Haselbacher, M., & Hattmannsdorfer, H. (2018). Desintegration in der grundversorgung. Theoretische und empirische befunde zur unterbringung von asylsuchenden im ländlichen raum. Juridikum, 3/2018, 373–385.

- Haus, M., & Sweeting, D. (2006). Mayors, citizens and local democracy. In H. Bäck, H. Heinelt, & A. Magnier (Eds.), The European mayor. Political leaders in the changing contexts of local democracy (pp. 151–176). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Headlam, N., & Hepburn, P. (2017). What a difference a mayor makes. A case study of the Liverpool mayoral model. Local Government Studies, 43(5), 731–751. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1333429

- Heimann, C., Müller, S., Schammann, H., & Stürner, J. (2019). Challenging the nation-state from within: The emergence of transmunicipal Solidarity in the course of the EU refugee controversy. Social Inclusion, 7(2), 208–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v7i2.1994

- Heinelt, H., & Hlepas, N.-K. (2006). Typologies of local government systems. In H. Bäck, H. Heinelt, & A. Magnier (Eds.), The European mayor. Political leaders in the changing contexts of local democracy (pp. 21–42). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Hinger, S. (2020). Integration through disintegration? The distinction between deserving and undeserving refugees in national and local integration policies in Germany. In S. Hinger, & R. Schweitzer (Eds.), Politics of (Dis)Integration (pp. 19–39). Springer.

- Hinger, S., Schäfer, P., & Pott, A. (2016). The local production of asylum. Journal of Refugee Studies, 29(4), 440–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/few029

- Hoekstra, M. (2018). Governing difference in the city: Urban imaginaries and the policy practice of migrant incorporation. Territory, Politics, Governance, 6(3), 362–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1306456

- Horst, C., & Grabska, K. (2015). Introduction: Flight and exile—uncertainty in the context of conflict-induced displacement. Social Analysis, 59(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2015.590101

- Hubbard, P. (2005a). Accommodating otherness: Anti-asylum centre protest and the maintenance of white privilege. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 30(1), 52–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2005.00151.x

- Hubbard, P. (2005b). ‘Inappropriate and incongruous’: Opposition to asylum centres in the English countryside. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2004.08.004

- Jacob, B., Lipton, B., Hagens, V., & Reimer, B. (2008). Re-thinking local autonomy: Perceptions from four rural municipalities. Canadian Public Administration, 51(3), 407–427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-7121.2008.00031.x

- Kordel, S., Weidinger, T., & Jelen, I. (Eds.). (2018). Processes of immigration in rural Europe: The status Quo, implications and development strategies. Cambridge Scholars.

- Kos, S., Maussen, M., & Doomernik, J. (2016). Policies of exclusion and practices of inclusion: How municipal governments negotiate asylum policies in the Netherlands. Territory, Politics, Governance, 4(3), 354–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2015.1024719

- Kreichauf, R. (2018). From forced migration to forced arrival: The campization of refugee accommodation in European cities. Comparative Migration Studies, 6(7), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-017-0069-8

- Kuhlmann, S., & Wollmann, H. (2013). Verwaltung und verwaltungsreformen in Europa. Springer Fachmedien.

- Larsen, B. (2011). Drawing back the curtains: The role of domestic space in the social inclusion and exclusion of refugees in rural Denmark. Social Analysis, 55(2), 142–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2011.550208

- Le Bart, C. (2003). Les maires: Sociologie d’un rôle. Presses universitaires du Septentrion.

- Magnier, A. (2006). Strong mayors? On direct election and political entrepreneurship. In H. Bäck, H. Heinelt, & A. Magnier (Eds.), The European mayor: Political leaders in the changing context of local democracy (pp. 353–376). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Manatschal, A., Wisthaler, V., & Zuber, C. I. (2020). Making regional citizens? The political drivers and effects of subnational immigrant integration policies in Europe and North America. Regional Studies, 54(11), 1475–1485. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1808882

- Mayntz, R., & Scharpf, F. (1995). Gesellschaftliche selbstregelung und politische steuerung. Campus.

- Miellet, S. (2019). Human rights encounters in small places: The contestation of human rights responsibilities in three dutch municipalities. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 51(2), 213–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2019.1625699

- Mosley, L. (2013). Interview research in political science. Cornell University Press.

- Oomen, B., Davis, M. F., & Grigolo, M. (Eds.). (2016). Global urban justice: The rise of human rights cities. Cambridge University Press.

- Panelli, R., Hubbard, P., Coombes, B., & Suchet-Pearson, S. (2009). De-centring white ruralities: Ethnic diversity, racialisation and indigenous countrysides. Journal of Rural Studies, 25(4), 355–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.05.002

- Schammann, H., Bendel, P., Müller, S., Ziegler, F., & Wittchen, T. (2020). Zwei Welten? Integrationspolitik in Stadt und Land. Robert Bosch Stiftung.

- Scheibelhofer, P. (2012). From health check to muslim test: The shifting politics of governing migrant masculinity. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33(3), 319–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2012.673474

- Scheibelhofer, E., & Luimpöck, S. (2016). Von der herstellung struktureller ungleichheiten und der erschaffung neuer handlungsräume: Eine qualitative pilotstudie zur situation anerkannter flüchtlinge in peripheren räumen. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 41(S3), 47–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-016-0243-5

- Schiller, M. (2018). Conceiving governance: A state of the art and analytical model for research on immigrant integration. WORKING PAPER 01/2018 JKU https://www.jku.at/fileadmin/gruppen/119/WOS/Working_Papers/WP/WP_Schiller_01-2018_Schiller__M.pdf (last accessed 10.08.20).

- Scholten, P. W. A. (2016). Between national models and multi-level decoupling: The pursuit of multi-level governance in Dutch and UK policies towards migrant incorporation. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(4), 973–994. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0438-9

- Scholten, P., & Penninx, R. (2016). The multilevel governance of migration and integration. In B. Garcés-Mascareñas, & R. Penninx (Eds.), Integration processes and policies in Europe (pp. 91–108). Springer.

- Segarra, H. (2020). The reception of asylum seekers in Europe: Exclusion through accommodation practices. In M. Jesse (Ed.), European societies, migration, and the Law (pp. 213–229). Cambridge University Press.

- Spencer, S., & Delvino, N. (2019). Municipal activism on irregular migrants: The framing of inclusive approaches at the local level. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 17(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2018.1519867

- Täubig, V. (2009). Totale institution asyl: Empirische befunde zu alltäglichen lebensführungen in der organisierten desintegration. Juventa.

- Vittuari, M., Devlin, J., Pagani, M., & Johnson, T. G. (Eds.). (2020). The Routledge handbook of comparative rural policy. Routledge.

- Wagenaar, H. (1999). Value pluralism in public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 21(4), 441–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.1999.11643400

- Wagenaar, H. (2004). “Knowing” the rules: Administrative work as practice. Public Administration Review, 64(6), 643–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00412.x

- Weidinger, T., Kordel, S., & Kieslinger, J. (2019). Unravelling the meaning of place and spatial mobility: Analysing the everyday life-worlds of refugees in host societies by means of mobility mapping. Journal of Refugee Studies, fez004, https://doi-org.uaccess.univie.ac.at/https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez004.

- Weinar, A., Bonjour, S., & Zhyznomirska, L. (Eds.). (2018). The routledge handbook of the politics of migration in Europe. Routledge.

- Whyte, Z., Larsen, B., & Fog Olwig, K. (2018). New neighbours in a time of change: Local pragmatics and the perception of asylum centres in rural Denmark. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(11), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1482741

- Woods, M. (2018). Precarious rural cosmopolitanism: Negotiating globalization, migration and diversity in Irish small towns. Journal of Rural Studies, 64, 164–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.014

- Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Belonging and the politics of belonging. Patterns of Prejudice, 40(3), 197–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313220600769331

- Yuval-Davis, N. (2007). Intersectionality, citizenship and contemporary politics of belonging. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 10(4), 561–574. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230701660220

- Zapata-Barrero, R., Caponio, T., & Scholten, P. (2017). Theorizing the ‘local turn’ in a multi-level governance framework of analysis: A case study in immigrant policies. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 83(2), 241–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852316688426