ABSTRACT

The article examines the role of the Euroregions in the first Covid-19 pandemic wave in Europe. The beginning of the pandemic in the spring of 2020 led to the closures of state borders. This complicated the situation of Polish cross-border commuters working in Germany and the Czech Republic. The border closure also showed the strength of Euroregions, able to react and transmit the demands of borderlanders to the Polish government. To analyse this question, we adapt the deliberative system theory. The actions taken by Euroregions, as institutions of public space, were considered as deliberative consequences of non-deliberative actions of government.

INTRODUCTION

The freedom of movement of European Union (EU) citizens across borders in Europe is a cornerstone of the EU. Free border crossing and developed cross-border cooperation (CBC) became one of the principal EU narratives (Scott, Citation2016). In the Schengen space, about 2 million people cross national borders on a daily or weekly basis for work or education (European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON), Citation2018). Multilevel governance (Blatter, Citation2004; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2003), EU regional cohesion policies and an increase of paradiplomatic activities of sub-nation-state authorities supported a consensus on rescaling Europe with an increasing influence of regional and local actors from a cross-border perspective (e.g., Keating, Citation1998; Klatt, Citation2019; Scott, Citation1999; Telò, Citation2013; Warleigh-Lack et al., Citation2011). Cross-border regions, organized in Euroregions or European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC), are of key importance among the priorities of European funding programmes.

Currently, it seems that the further prosperous development of border regions has been challenged by the Covid-19 outbreak. The epidemic danger caused the closure of almost all Schengen space in March 2020 and imposed physical barriers on EU internal borders. This made cross-border flows of people physically impossible, or at least very difficult to implement. The daily lives of cross-border commuters in the whole EU were changed. Many of them lost their jobs, be it a consequence of the forced quarantine or the closed border. Many companies dependent on cross-border flows close or significantly restrain – either temporarily or definitively – their operations. We might experience a sort of pandemic adjustment, with different consequences for European citizens. It seems borders are making a temporary comeback affecting everyone directly, yet not equally (Calzada, Citation2020). This is evident also in the moment of finishing this paper (May 2021) when the third pandemic wave still imposed limitations on the free movement of people. The only exception is the Dutch–German border, which remained open during the first and the second waves of the pandemic (van der Velde et al., Citation2021).

The preliminary reactions of scholars observed massive re-bordering tendencies because most of the applied measures based on social distancing were done on a strictly national basis and contradicted steps desired by the European institutions or the World Health Organization (WHO) (Brunet-Jailly & Vallet, Citation2020; Klatt, Citation2020a; Lee et al., Citation2020; Unfried, Citation2020; Wassenberg, Citation2020). These border closures, for which Medeiros et al. (Citation2020) proposed the term covidfencing, occurred with the support of public opinion in EU member states (Calzada, Citation2020; Opiłowska, Citation2021), which have accepted the necessity to close their borders due to public health reasons, even if the WHO recommended no trade or travel restrictions.

The border closure was also the case regarding the Czech–Polish and German–Polish borders. At the beginning of introducing social distancing guidelines, Poland based its anti-pandemic strategy on almost immediate border closures and massive restrictions of the free movement of people, including the inhabitants of border areas. It affected over 160,000 Polish cross-border commuters working in the Czech Republic and Germany. In the case of the Polish–German border, closure also affected students visiting schools in a neighbouring country (Wanat & Mischke, Citation2020). Simultaneously, there were no restrictions introduced in traveling within the country. In the case of Germany and the Czech Republic, border regimes were different than they were in Poland, which made crossing the border asymmetric (e.g., following the measures, it was easier for Poles to enter the Czech Republic than leave Poland). The cross-border commuters do not have their political or trade unions representation. They are diffused on the territory of border areas, as well as among the branches of industry and services. There is one type of institution that could be able to react and advocate effectively for their employee rights: Euroregions.

THEORY

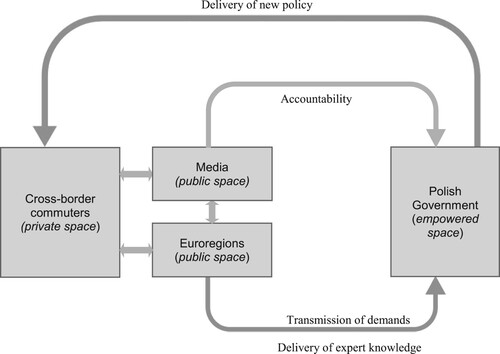

We adopt a theoretical framework of a deliberative system theory (deliberative systemic approach, discursive institutionalism; Dryzek, Citation2009; Dryzek & Stephenson, Citation2012; Mansbridge et al., Citation2012; Schmidt, Citation2010). In this approach – applied mainly to the analyses of deliberative democracies – deliberation and the legitimacy of the decision-making process is seen as an interaction of entities from the private, public and empowered space in the complex system as a whole (Mansbridge et al., Citation2012, p. 2). In our case, we perceive actors interested in changes in border policy (Polish government, local self-governments, Euroregions, cross-border commuters and their relatives, local and regional media) as units of the deliberative system, where conflicts and problems are being solved rather by the means of argumentation, consultation, and persuasion than oppression. Euroregions are analysed as units of public space, able to transmit the demands of cross-border workers and students (private space) to the empowered space (Polish government, especially the prime minister and Ministry of Health). This framework is illustrated in .

Figure 1. Deliberative system framework in the case of Covid-19 cross-border commuting outbreak.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Given that the overall quality of democracy in the Czech Republic and Poland is declining as a result of illiberal tendencies of ruling parties (Stanley, Citation2019), we assume that deliberative democracy is working well at the level of local self-governments (Carson & Gerwin, Citation2018), whereas at the state level it is rather seen as a possible ‘prescription’ for illiberal and populist tendencies (Suteu, Citation2019). Nevertheless, the deliberative system approach enables the analysis of the chosen case, bearing in mind that the motivation of political leaders could be a fear of political instability or time pressure in the time of Covid-19 pandemic. Measuring the quality of democracy in Poland is not our goal because an application of deliberative system theory is possible also in illiberal democracies, as well as in authoritarian regimes (Dryzek, Citation2009; Mansbridge et al., Citation2012, p. 8). Thus, in our case, it is rather the analysis of deliberative consequences of non-deliberative actions taken by empowered space agents at central levels and changing the regulations as a result of post-factum deliberation. Our case is also a good exemplification of the centre–periphery principle, formulated and developed within the deliberative democracy theory by Habermas (Citation1991) and Peters (Citation1993/2008).

The reason why we adopted this framework is its explanatory potential of processes (dynamic approach) rather than static criteria. Deliberative system theory could be also seen as the framework for explaining the concept of governance and multilevel governance (Dryzek, Citation2016), which serve as main explanatory terms in the analyses of cross-border dynamics (Hamedinger, Citation2011; Plangger, Citation2019). Even then, there is a lack of scholarship on the analyses of political decision-making on borders and cross-border regions, using the deliberative system approach so far. The ‘multilevel governance’-oriented researches are focused more on the structures and patterns of interactions, not on the actions as such. This article analyses the potential of cross-border institutions (Euroregions) in the political decision-making process.

METHOD

The aim of this paper is to analyse the role of Euroregions as public space agents, which could be effective in lobbying for the cross-border labour market and delivering the expertise for knowledge-based decision making. Our assumption is, that even if Euroregions are not designed for advocating and lobbying (they usually do not have these kinds of tasks in their statutes and there is also no financial support from EU Interreg funds for this kind actions), in the time of Covid-19 outbreak, they could use their assets: a network of professionals and insider knowledge about cross-border flows; and became first-person agents of public space, able to make an impact on state authorities. We also assume that the impact of Euroregions depends on two variables: density and intensity of cross-border flows in the specific regions and strength of private cross-border ties. Thus, the main research question we would like to introduce is what was the role of Euroregions in the Polish border areas in the process of adopting the anti-Covid-19 measures to the demands of cross-border labour market flows? Should we consider it more like political institution (empowered space) or public space unit?

To meet these already discussed aims, we collected the data using the method of content analysis. We investigated official documents of Euroregions and public authorities, Facebook profiles of the Euroregions, the Facebook pages gathering cross-border commuters (Głos Pracowników Transgranicznych ‘Czechy’ and Pracownicy Transgraniczni Razem [Wszystkie kraje]) the page of the Polish minority living in the Czech Republic (Zwrot) and pages of the Czech–Polish and German–Polish Euroregions. We also used and interpreted regional media in Poland, Czechia and Germany. Finally, we conducted seven individual semi-structured interviews with local stakeholders: representatives of Euroregions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), dealt with cross-border initiatives, and representatives of local authorities in the border areas (see Appendix 1 in the supplemental data online). All interviews were conducted in July 2021 on the Czech–Polish borderland (three on the Czech and four on the Polish side).

We choose Poland and its border with the Czech Republic and Germany as our case because the largest number of cross-border workers in the whole EU are the Poles working in Germany (according to Eurostat data from 2019).Footnote1 The number of Polish cross-border commuters working in the Czech Republic is also relevant and has experienced a rise during last 10 years. All the Germany–Poland and Czech Republic–Poland border areas are also covered by the Euroregions, which allows for a comparison of actions taken by different Euroregions, according to our goals.

ANALYSIS

System of cross-border commuting and its agents

The EU’s territory is up to 40% made by border regions. About 30% of the EU population lives in areas along the 40 land borders between the EU and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member states. The border regions are often among the less advanced regions in their national context, implying, for example, relatively large distance to regional centres or other disadvantages for regional development (Beck, Citation2019). These areas tend to be economically weaker and have more underdeveloped infrastructure in comparison with more central regions (Böhm & Drápela, Citation2017). The unemployment rate tends to be higher too. Therefore, supporting cross-border flows is one means to improve the perspectives of border regions (Böhm & Kurowska-Pysz, Citation2019). The cross-border labour market is one of the important examples of these cross-border flows.

Although the European integration process has achieved considerable results, many obstacles based on differing legal and administrative backgrounds of member states have remained (e.g., Sohn & Reitel, Citation2013). Current internal borders are principally open to the free movement of persons, goods, capital and services – at least in non-pandemic times. Border region residents have been encouraged to exploit the free movement and actively engage in creating cross-border living spaces, where daily life activities such as residence, work, education, shopping and other leisure activities cross the borders (Beck, Citation2019; Decoville et al., Citation2013; Klatt, Citation2019).

Private space: cross-border commuters

The number of cross-border commuters in the EU has been on a steady rise since the introduction of the European single market (Cavallaro & Dianin, Citation2019), but generally labour mobility between EU member states – transnational migration and cross-border commuting – has historically remained rather low. According to the data of the European Central Bank (ECB), in 2000, 0.4% of the EU working population was known to commute across borders to work (Heinz & Ward-Warmedinger, Citation2006). It has only been very recently that cross-border commuting has increased significantly (Böhm & Opioła, Citation2019). In 2018, 9.7 million employed persons worked outside their home country, which is about 4.1% of all employed people within the EU (Eurostat, Citation2019). A total of 1.5 million of them (0.7% share of total EU labour force) were cross-border commuters, traveling to the neighbouring country on a daily basis (Cavallaro & Dianin, Citation2019; Eurostat, Citation2019).

Since 2004, the rise of cross-border commuting has taken place especially in the border regions of new EU members. The general pattern is commuting across the former Iron Curtain: from Slovenia, Slovakia and Hungary to Austria, from the Czech Republic to Austria and Germany, and from Poland to Germany (Cavallaro & Dianin, Citation2019). The more massive cross-border commuting growth of Poles in Germany occurred in the 1990s. According to Eurostat (Citation2019), in 2018, 206,000 Poles work in one of the neighbouring countries having a residence in Poland, from which 124,000 work in Germany and 8000 in the Czech Republic (Eurostat, Citation2019; Lang, Citation2012; Miera, Citation2008). However, this low number of Poles employed in the Czech Republic in 2018 seems to be underestimated in the light of the figures revealed by the pandemic. Moreover, it calls for more reliable cross-border data.

Apart from the official data, new calculations were highlighted because of lockdown. In 2020 on the German–Polish border, there were about 125,000 commuters, mainly Poles working in Germany in construction and services or Poles living in Germany and working in Poland because many of them, although employed in Poland, bought houses on the German side (Jańczak, Citation2020; Opiłowska, Citation2021). In the last years, a number of Poles commuting to the Czech Republic significantly increased. According to Polish-based data from 2020, there were more than 47,000 Poles employed in Czechia, and about 42,000 of them benefitted from cross-border commuting. Roughly 25% of them worked in the Moravian–Silesian Region (Kasperek & Olszewski, Citation2020). This number grew dynamically in 2014–20, as the annual increase was around 30%. In the Czech Republic, Poles are hired mostly in the steel, mining and automotive industries, which is a kind of solution for the structural unemployment problem in Polish border regions (Kasperek & Olszewski, Citation2020) (interview 1).

Public space: Euroregions

Euroregions are a specific form of spatial organization and a way to channel people’s activities. These entities facilitate an institutional dimension of CBC, that is, cooperation of public actors at local or regional level in border regions. Because Euroregions operate in two or more countries, they have specific structures. They are composed of the representatives of local and regional self-government from both sides of the border. Their everyday activity is secured by professional employees who are employed in both/all of the secretariats of the Euroregion. Normally, each secretariat employs up to 10 full-time staff members. The work of secretariats is controlled by the nominees of the members of self-governments who create Euroregional assemblies. The secretariats of Polish Euroregions are gathered into the Federation of Polish Euroregions.

As such, the Euroregions mostly do not have their own single legal personality because they consist of loosely cooperating twin structures in each engaged state (Medeiros, Citation2011). In this way, cross-CBC can be implemented without introducing special legal conditions. Although this form seems complicated, the activity of Euroregions can be deemed as one of the major successes of the idea of European integration. Currently, there are over 150 Euroregions in Europe (not only within the EU; Durà Guimerà et al., Citation2018). On the German–Polish and Czech–Polish borders, there are nine Euroregions that covered all the border territory of the Germany–Poland and Czech Republic–Poland borders (). Even if cross-border commuting is an important problem of the German–Polish and Czech–Polish border areas, none of the Euroregions deals with this topic in the official documents (statutes and founding agreements). Also, the cooperation objectives such as support to the regional job market or lobbying in the interest of the local community are declared to a limited extent ().

Figure 2. Overview of cross-border commuting on the Czech Republic–Poland and Germany–Poland border.

Note: Not depicted is the trilateral Polish–Czech–Slovak Euroregion Beskidy/Beskydy, because it does not involve territory with an immediate Polish–Czech border.Sources: Authors’ own estimation based on interviews; and European Union and national data.

Table 1. Goals of cross-border policies in the documents of the Czech Republic–Poland and Germany–Poland Euroregions.

Empowered space: government

We understand all the political bodies as an empowered space in the system of cross-border commuting responsible for border policies and labour market policies. First, we would like to employ a distinction between the ‘normal times’ and the times of crisis, in which this second case is our scope of analysis. During the normal times, free border crossing and free movement of workers are guaranteed by the Treaty on European Union (TEU), the Treaty on the Functioning of European Union (TFEU) and the Schengen Agreement. The Schengen area, founded in 1985, comprises 26 European countries (22 from the EU and four non-EU countries) and constitutes the open borders area. Countries of the Schengen area officially abolished passport controls and other forms of border control on the mutual, internal borders of the Schengen area. They also introduced a common visa policy.

During times of crisis, the EU member state can refuse the right of entry or residence of EU citizens on the grounds of public policy, public security or public health, which was the basis of the 2020 ‘covidfencing’ policy. In the case of Poland, border controls could be reintroduced under the decree of the Minister of Interior. Additional measures, such as 14-day quarantine, can be introduced by the Council of Ministries of the Republic of Poland. Similar procedures are to be found in the Czech Republic. Both countries are unitary states, and the political power is centralized. In the case of Germany (federal state), some special measures (e.g., compulsory testing or quarantine for third-party nationals) could be introduced by the Länder (federal states).

RESULTS

Delivering new policy: covidfencing

In 2006, in the Schengen Borders Code, members agreed for a possibility of temporary reintroducing border control between Schengen countries, as an instrument of last resort, in the case of a threat to public security or internal security (Regulation EC No. 562/2006). Since then, till 1 June 2020, Schengen countries have used this possibility 206, 85 times because of Covid-19.Footnote2

In the case of analysed countries, Poland reintroduced border control at all internal Schengen land borders, air and sea borders, from 15 March to 12 June 2020. Germany did the same at land borders with Denmark, Luxembourg, France, Switzerland and Austria from 16 March to 15 June 2020; air borders with Austria, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, Denmark, Italy and Spain, and sea borders with Denmark from 19 March to 15 June 2020. The Czech Republic reintroduced border control at its land borders with Germany and Austria and air borders from 14 March to 13 June 2020.Footnote3

In Poland, border controls were reintroduced by the decree of 13 March 2020. In the decree, all the open border crossings were listed (Dz.U. 2020/434).Footnote4 On the same day, the second decree was published, where categories of people entitled to cross the border were mentioned:

Polish citizens.

Foreigners: spouses and children of Polish citizens and foreigners with a work or residence permit.

Members of diplomatic corps and their families.

Foreigners with Karta Polaka (Polish Card, a document confirming belonging to the Polish nation, mostly used by Ukrainian state citizens).

Foreigners with a special permit of the Commander of Polish Border Guard (Dz.U. 2020/435).Footnote5

Additionally, the international train connections were suspended on 31 March. In the same decree (Dz. U. 2020/566),Footnote6 an obligatory 14-day quarantine was introduced for all people crossing the Polish border. It was also valid for cross-border commuters and students crossing the border on a daily basis. This quarantine obligation for cross-border commuters and students was abolished on 4 May 2020, except for cross-border physicians, nurses and workers of nursing homes.

In the Czech Republic, the country landlocked by the internal Schengen border, the first government decrees responding to the first wave of the Covid-19 crisis restricted the free movement, introduced an emergency state (2020/194),Footnote7 and reintroduced the border controls with Austria, Germany and in the airports (2020/197)Footnote8 as of 14 March 2020. Moreover, as Slovakia and Poland ceased the entrance of foreigners to their territory, there was no factual need to ‘close’ the border by the Czech government. The governmental decree (2020/198)Footnote9 prohibited the entrance of foreigners from ‘risk countries’ and a further decree (2020/200)Footnote10 de facto stopped international transport, except for flights from Prague. Finally, the government decree (2020/203)Footnote11 of 13 March 2020 prohibited the entrance into the Czech Republic of all foreigners without a residence permit or working permission, and decree 2020/221Footnote12 decided upon temporary reintroduction of border controls on all Czech borders from 15 March for a preliminary period of four weeks. However, the strictness of these rules was softened by the fact that the vague formulation allowed for the ‘entrance of foreigners, who are beneficial for the Czech Republic’.

Germany closed its own border as the last country of three relevant for this research. As Poles and Czechs de facto closed their borders with Germany, the Germans did not have to introduce such measures. Germany closed its borders – while accepting cross-border commuters – with Austria, France, Denmark, Luxembourg and Switzerland on 16 March. Moreover, Poland (and the Czech Republic too) introduced an obligatory quarantine for cross-border commuters for a certain period during the pandemic crisis. Some German (and to a lesser extent also Czech) employers of Polish cross-border commuters even offered to pay for their accommodation.

Generally, the incoming cross-border commuters could have worked in Germany and the Czech Republic also during the pandemic, but the Polish regulation on obligatory quarantine complicated that substantially. It is worth mentioning that these regulations were introduced without further deliberations. It was not only the characteristic of Central European border policies but also a worldwide phenomenon (Medeiros et al., Citation2020). But in the case of Poland (and to our knowledge, it was only the Polish specific), there were no exceptions applied for cross-border commuters. This first reaction of empowered space could be exemplified by the opinion of German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer: ‘As long as there’s no European solution, you must act in the interest of your own population. … Those who don’t act are guilty’ (Hernandez-Morales, Citation2020).

The covidfencing decision was taken on the very level of the central Polish government, which acted unilaterally without major coordination with its neighbours, the European Commission, regional and local levels of public administration, or other social partners such as entrepreneurs, who employ cross-border commuters. Saxon and Brandenburg prime ministers questioned the adequacy of those measures undertaken by the Polish government (Opiłowska, Citation2021) and stressed the negative impact of those measures on the everyday lives of cross-border region residents. The specificities of border regions were not taken into consideration. Therefore, the local authorities – mostly Euroregions – reacted to these unilaterally taken decisions influencing their (public) space.

Demands of cross-border commuters

Mutual limitations caused several problems. First, although at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic entries into Czech and German territories were not prohibited for Poles, closure of local border crossings on the Poland–Germany and Poland–Czech Republic borders forced Polish commuters to travel indirectly. In several cases, for example, of Denso plant in Czech Liberec (the nearest border crossing with Poland in Zawidów was closed) and PF Plasty in Chuchelná (an analogical case), the road that Polish commuters had to take to get to work has increased from less than 1 km to 65 km, as reported in local and regional media (Gadomska, Citation2020; Karban et al., Citation2020). Second, introducing the obligatory quarantine for Poles returning home from abroad forced cross-border commuters to adapt to the new conditions from 27 March. This led them towards two types of reactions: some groups of Polish cross-border commuters who decided to stay at work in Germany or the Czech Republic found accommodation there, and were separated from their families. The other group of these commuters decided to stay home and depend in whole or in part on their income, which caused significant difficulties for their German or Czech employers (Kasperek & Olszewski, Citation2020; Medeiros et al., Citation2020). Most of these cross-border commuters are the sole breadwinners in their families.

It took only two days for cross-border commuters to begin to act publicly and express their demands of conveniences. On 29 March, the Facebook page ‘Głos pracowników transgranicznych (Czechy)’ (The voice of cross-border commuters [Czech Republic]) was set up by a Pole working in a Czech-based automotive plant. The aim of this page was the networking of private persons to jointly express the demands. The basic need of the group members was to abolish the 14-day quarantine for those who travel on daily basis and to introduce the ‘Karta pracownika transgranicznego’ (cross-border commuter’s card). The proposed measures were identical to those already introduced on the Czech side because the initiative was supported mainly by Polish workers in the Czech Republic. The second Facebook page ‘Pracownicy transgraniczni razem (wszystkie kraje)’ (cross-border commuters altogether [all countries]) was set up on 17 April by the Szczecin-based workers (Poland–Germany border). The discussion on the Facebook page commented on the regulations imposed by the Czech authorities. It highlighted the non-coordination between both governments and underlined the concerns of Polish cross-border commuters that the decisions of the Polish authorities could contradict the Czech ones.

It seems that Facebook became the main source of information and networking in most of the European borderlands during the first lockdown. Many researchers who studied border closures during a pandemic pointed this out (Böhm, Citation2021; Horobets & Shaban, Citation2020; Klatt, Citation2020b).

Accountability measures

As documented in the Polish–German borderland, the media have worked with the narrative of an open border as a norm (Opiłowska, Citation2021) – and it was the case in the Czech–Polish borderland too, where the same narrative was applied – with a special role of the Polish minority media serving the Polish-speaking minority in the Czech Republic (e.g., Brandys, Citation2020). Media coverage focused mainly on the complications for the cross-border commuters, but they have also not omitted the ‘softer’ dimension of the consequences of border closures: the posters declaring mutual sympathies placed on the banks of both rivers dividing neighbours – Oder/Odra in the Polish–German and Olza in the Czech–Polish border regions cases – attracted the attention of the media with national coverage, which mostly tend to overlook the periphery.

The restrictions also caused protests of the concerned cross-border commuters, which took place in both studied cases. These protests were visible mainly in the divided cities Frankfurt/Oder/Slubice and Cieszyn/Český Těšín, where protesters reclaimed ‘comeback to normality [of the open border]’ with the slogans such as ‘Don’t separate families’, ‘We want to work and live with dignity’, ‘Let us go to work’ and ‘Let us go home’ (Opiłowska, Citation2021). These protests were led by cross-border commuters and their families. The common scheme of those protests was a protesting (Polish) breadwinner, who decided to avoid quarantine obligations and continued working and who remained on the German or the Czech sides of the river, whereas his (in most, yet not all, observed cases the men worked in the neighbouring country and the women stayed with their children in the home country) family protested on the Polish side of the river.

The border closures and related border-crossing restrictions pointed to the existence of a cross-border civil society in both studied areas. In Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia, the banners ‘I miss you, neighbour’, which the activists placed on railings on their side of the border river, attracted substantial media attention, not only from the Czech Republic and Poland. Stefan Mańka, co-author of the Polish banner ‘I miss you, Czech’, explained that he felt an urgent need to deliver a positive message to lift the mood of the locals (interviews 4 and 6). A similar positive message was conveyed also in the Frankurt/Słubice context, wishing ‘good health to the neighbours’ (Opiłowska, Citation2021). There were also dark sides to the local public discourses. Local authorities of Słubice in Poland have asked the government in an official letter, signed by the mayor and head of the council, to (unilaterally) close the border. In Cieszyn/Český Těšín the banners appeared and warned of entering Poland because the first infection in this divided border city appeared on the Polish side (interview 7).

Transmission of demands: Euroregions and local authorities

The individual regions, where cross-border commuting has been strongly present, started to develop – with the support of Euroregions – concentrated and partly coordinated efforts to lift the quarantine obligation. This was made by means of letters to the Polish prime minister, which was supported by the analytical evidence providing further reasoning to lift the quarantine obligations (). The first actions of border communities started in the last decade of March 2020. In late April, the Polish part of Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia reported that the coalition of all Poland–Czech Republic Euroregions was established (Tyrna, Citation2020). These initiatives were also supported by the collective letters of all Polish Euroregions in which their representatives asked for easing the adopted measures. Open letters were the most common measure at this stage of cooperation.

Table 2. Timeline of actions taken by selected public space institutions on cross-border commuting.

Local authorities and public actors expressed their support for border region residents by referring to catchphrases such as ‘united Europe’, ‘two banks–one city’, and ‘transnational life of borderlanders’ (Opiłowska, Citation2021). They criticized the ‘top-down imposed’ restrictions and demanded the opening of the border for local traffic. The ‘hard’ economic argumentation was also applied by the local politicians. Anna Hetman, mayor of Jastrzebie-Zdrój and member of the Euroregion Těšín/Cieszyn Silesia board, protested the imposed measures using the letter to the Polish prime minister. Inter alia, she argued:

Hundreds of residents of Jastrzębie-Zdrój, who commuted daily to work in industrial plants and mines in neighbouring Czech towns, lost the opportunity to commute to work overnight, and lost thus the possibility of earning, often the only family income. I fully understand the extraordinary and unprecedented situation in which we find ourselves and the resulting concern for the best security of our country. However, it must not be at the expense of cross-border commuters, who have to choose between a job in the Czech Republic without a chance to live a normal family life or losing the only family income. Leaving them only one day to make such an important decision is not acceptable. Moreover, in comparison to the locals employed in Poland, who receive social benefits while being on the forced quarantine, those employed in the Czech Republic are left without any financial support. (TVN, 2020)

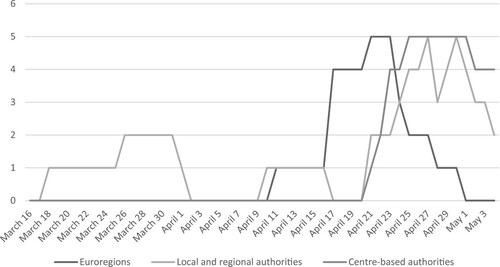

Based on an analysis of the activities of public space units, we can assume that the culture of deliberation was weak (low). It was rather one-way communication from regions to the centre-based authorities, with very limited feedback. The number of centre-based politicians involved in the deliberation was exceptionally low, too. During the analysed period, it is possible to extract two different periods of time. The first – before actions had been taken by Euroregions – is characterized by extremely limited engagement of centre-based politicians. After Euroregion initiatives from 17 to 21 April: publication of a technical report on consequences of border closures, open letters to the Polish government and making public the plans of organizing the protests on 25 April (not organized, but supported by Euroregions’ officials), the number of parliament and government actions have grown rapidly (). Primarily, it took the form of interpellations of members of the Polish parliament to the government (nine personal or group interpellations) and statements of presidential candidates.Footnote13 All these actions, as well as the statement of the Polish ombudsman and open letters of minister-presidents of two German federal states, we can include as accountability measures (). The dialogic deliberation with the government officials was very limited in this period too. There was one parliamentary debate, 66 minutes long, organized on 29 April, with an introduction of the Minister of Labor, Marlena Maląg; five-minute statements of representatives of parliamentary groups, and a short discussion.Footnote14 One day after, the Polish prime minister organized a teleconference with border district administrators. There is no record of this event, but after hearing it, the prime minister stated that borders would be open for cross-border workers in two days’ time. As one of our interviewees stated, all the actions taken by the Euroregion and local and regional authorities were ignored by the Polish government. For example, the technical report on the consequences of border closures was read by the Ministry of Health, but publicly no one referred to it (interview 7). Also, the involvement of Euroregion Cieszyn Silesia was stronger than the involvement of the others because of previous experience of cooperation and personal ties with voivodship authorities.

Figure 3. Timeline of actions taken by agents of public and empowered space (16 March–4 May 2020; seven-day moving average).

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on media analysis.

Table 3. Timeline of actions taken by centre-based politicians on cross-border commuting.

The initiatives coordinated by the Euroregions led to success as the Polish government eased the measures and cancelled the obligatory quarantine for cross-border commuters from 4 May 2020. This obligation was replaced by a compulsory negative Covid-19 test once a month. Despite the average price of this test being around €120 – paid by the commuters themselves, but often reimbursed by their employers – it was still a substantial burden, as this decision reopened the way towards reconciling family and labour obligations. What was also observed in analysed border contexts, and what was similar with findings (Unfried, Citation2020) from the German–Belgium–Dutch border, was a lack of cross-border governance caused by the dominance of the national states. Anti-Covid-19 measures, also in the border regions, were introduced on a national basis and were different on both sides of the border. Here we see a failure of Euroregions, unable to establish cross-border crisis management. This confirms our hypothesis that Euroregions are not empowered spaces but they are the public space institutions.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

A functional CBC needs to be based upon a network of cooperating institutions, which have created an atmosphere of mutual trust and advocate for meeting the common needs and planning common objectives. This requires a relatively high standard of quality from the involved institutions of public space. The ‘institutional thickness’ concept belongs to a group of institutional regional development theories (Amin & Thrift, Citation1995; Zukauskaite et al., Citation2017). This partial theory states that institutions are able to create informal conventions, habits and networks of relations that stabilize and stimulate the performance of regional economies, and which serve as one of the layers of the structures of public deliberation (Peters, Citation1993/2008, Citation1997/2008). The success of regions in the long-term horizon is then dependent on the ability of local actors to create such institutions, which can create a good framework for regional, cross-border development (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2017). Euroregions are the most influential cross-border development institutions out of all different forms of cross-border territorial organization in Europe (Euroregions, working communities, the EGTC, etc.) on the Polish–German and Polish–Czech borderlands (Dołzbłasz, Citation2015; Ulrich, Citation2020).

It should be recalled that Euroregions are usually formed as bottom-up initiatives. These initiatives mostly contained the word ‘region’ in various variations in their names: euregions (euregios), Euroregions or cross-border regions (Perkmann, Citation2003). There are two opposing understandings of their political role: the first is to understand the role of Euroregions as entities for functional integration of cross-border areas, mainly in the fields of transport, tourism, economy and environmental protection, without ‘political’ aspirations (Frątczak-Müller & Mielczarek-Żejmo, Citation2020; Kramsch & Hooper, Citation2004; Szmigiel-Rawska & Dołzbłasz, Citation2012). The second approach perceives Euroregions as new European policy actors capable of mobilizing local and regional elites around the idea of integration at the subnational level, and in the long run perhaps to create a new (Euro)regional identity (Boman & Berg, Citation2007; Durà Guimerà et al., Citation2018; Engl & Wisthaler, Citation2020; Medve-Bálint & Svensson, Citation2013; Perkmann, Citation2002, Citation2003).

Even if the causal relations between actions of Euroregions and governmental policy changing towards the border closures are not clearly evident, the actions of Euroregions are linked to the reopening of the border for cross-border commuters. Following the concept of institutional thickness, we should point out that the role of Euroregions in the regional development of the cross-border area is multilayered. These institutions have established cross-border networks of professionals and links to MPs, regional small and medium-sized enterprises, local and regional authorities, and education and scientific institutions. It is also the effect of logics of creation of Euroregions, while their boards are composed mainly of local stakeholders from public bodies: mayors, communal board members, teachers, etc. The role of the Euroregion should be understood more as facilitating and enhancing of, than ‘merely’ work with, the CBC (Javakhishvili-Larsen et al., Citation2018). Thus, our findings are similar to those of Engl and Wisthaler (Citation2020) who investigated the role of Euroregion Tyrol–South Tyrol–Trentino during the 2015–16 refugee crisis in Europe. The authors observed limitations of Euroregion policymaking, explaining them, among others, by the divergence in political discourse and positions on refugees and asylum seekers at the national and Euroregional levels. At the same time, they perceived the Euroregion as an important unit in ‘serving as an alternative political space between the Austrian and Italian state, and thus its potential capability to mediate between two political spaces’ (Engl & Wisthaler, Citation2020, p. 481). As Sara Svensson stated in her recent article on the research of actions of Euroregions towards refugee crisis (Svensson, Citation2020), these institutions are rather weakly active in the refugee and migrant inclusion policies, even if it affects their territories. What interested Euroregions were the matters of local communities, like the traffic situation. We see a lot of similarities with our findings, as the efforts of Euroregions concentrated on the needs of commuters only, with no broader proposals for anti-Covid-19 border measures. The first pandemic wave, which took place in the first half of 2020, brought along many new and unexpected restrictions. The border closures belonged among those restrictions, which complicated the daily lives of many inhabitants in border regions, who benefit from a concept of borders as an opportunity (Decoville et al., Citation2013) and cross-border complementarities. The present authors of this text analysed the Czech–Polish cross-border labour market only two years before the pandemic, yet in a very different situation. We concluded that the joint cross-border labour market is rather low and only unidirectional – driven mainly by the Czech automotive and mining sector attracting the Polish workforce. We also stated that most CBC stakeholders do not prioritize cooperation in the field of labour market, though exceptions exist.

These previous conclusions were challenged by Covid-19-related developments: despite the fact that number of Poles commuting to work in the Czech Republic cannot be compared with the numbers of those commuting to Germany, it is important for certain sectors of mainly low-qualified workforce and some parts of both borderlands. The pandemic showed that Euroregions have the cooperation in the field of the cross-border labour market as an important point of their agenda (even if it is not clearly stated in their statutes and agreements), despite them lacking direct competencies in this area. The study shows the substantial potential of Euroregions to act efficiently by the means of networking. It took less than a month when Euroregions’ representatives established the network of all Polish-based CBC units to advocate in one case. They helped to gather argumentation for softening the border regime for cross-border commuters. They applied several means to do so, starting from collecting the analytical evidence (Kasperek & Olszewski, Citation2020), voicing their interest vis-à-vis the central authorities by the means of official letters, and supporting the demonstrations and acts of mutual solidarity of the cross-border civil society. The strength of joint collective action, supported by the Federation of Polish Euroregions, contributed to the successful deliberation process and knowledge-based decision-making.

One more point needs to be made. Comparing the role of Polish Euroregions with other analysed cases from Germany, Italy, Austria (both from the times of migration crisis or Covid-19), we can observe a marginal role of the Euroregion as an institution in the system of political decision-making in Poland. Even if Euroregions were the most active actors, their activities remained neglected to the end of the reopening process. One of the Euroregional stakeholders, engaged actively in the process of border opening, said in the interview that Euroregional authorities were informed about the further steps of the Polish government, but unofficially. The representatives of Euroregions were not invited to the online meet-up with the Polish prime minister, which was focused only on the problem of cross-border commuters (interview 7). Another of our interviewees pointed out that the success of Euroregional advocacy was the success of one person: the manager of the Polish secretary of Euroregion Śląsk Cieszyński/Tesinskie Slezsko, who appeared to be very determined and forceful in his actions (interviews 3 and 6). The first pandemic wave also showed that free-border crossing is considered to be a norm in both studied border contexts. It also clearly showed that the market forces are crucial drivers in creating the cross-border reality as well as (neo)functional links operating as cross-border fibres linking both sides, which should be appreciated as an achievement (Jańczak, Citation2020). The joint labour market creates the very engine of cross-border flows. It is also true that in some border regions special policies for cross-border commuters were introduced since the beginning of lockdown, such as on the Danish–German or Spanish–Portuguese borders (Klatt, Citation2020b; Pires, Citation2020).

The eventual adoption of the European Cross-Border Mechanism (ECBM) – unsuccessfully proposed by the European Commission with the ambition to ease the lives in borderlands as part of the 2021–27 Cohesion Pack – would probably have helped to mitigate the impacts of the border closures. This instrument was proposed to allow one member state to apply the law of a neighbouring member state to facilitate cross-border solutions and projects (Evrard & Engl, Citation2018; Sielker, Citation2020) and to cope with a ‘border-blind’ national legislation. As mentioned, the ECBM proposal was refused. However, the pandemic-related re-bordering underlined that eventual adoption of the ECBM could have substantially eased the management of border closures also in the studied border contexts. As the ECBM cannot be applied in coping with the border closures, the CBC stakeholders must make use of other instruments. It is quite likely that the INTERREG 2021–2027 programmes – the same as in the case during the last years of implementation of the 2014–20 generation – will work with the special calls aimed at improving the capacities of Euroregions (and another cross-border entities) to deal with the tangible consequences of re-bordering.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.3 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 See https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/schengen/reintroduction-border-control/docs/ms_notifications_-_reintroduction_of_border_control_en.pdf, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02006R0562-20131126.

13 On 10 May 2020, presidential elections in Poland were planned and the campaign had started at the time of writing. Finally, because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the elections were postponed on 28 June.

REFERENCES

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (1995). Globalization, institutions, and regional development in Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Beck, J.2019). Transdisciplinary discourses on cross-border cooperation in Europe. Peter Lang.

- Blatter, J. (2004). From ‘spaces of place’ to ‘spaces of flows’? Territorial and functional governance in cross-border regions in Europe and North America. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(3), 530–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00534.x

- Böhm, H. (2021). The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on Czech–Polish cross-border cooperation: From debordering to re-bordering? Moravian Geographical Reports, 29(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.2478/mgr-2021-0007

- Böhm, H., & Drápela, E. (2017). Cross-border cooperation as a reconciliation tool: Example from the East Czech–Polish borders. Regional and Federal Studies, 27(3), 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2017.1350650

- Böhm, H., & Kurowska-Pysz, J. (2019). Can cross-border healthcare Be sustainable? An example from the Czech–Austrian borderland. Sustainability, 11(24), 6980, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246980

- Böhm, H., & Opioła, W. (2019). Czech–Polish cross-border (non)co-operation in the field of labour market: Why does it seem to be un-de-bordered? Sustainability, 11(10), 2855, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102855

- Boman, J., & Berg, E. (2007). Identity and institutions shaping cross-border co-operation at the margins of the European Union. Regional & Federal Studies, 17(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560701318516

- Brandys, S. (2020). Juz zabraklo slów, by skomentowac, to co sie dzieje [We miss the words to describe, what is happening here]. Retrieved June 19, 2020 from https://glos.live/KORONAWIRUS/detail/Juz_zabraklo_slow_by_skomentowac_to_co_sie_dzieje_Cichy_protest_nad_Olza/0.

- Brunet-Jailly, E., & Vallet, E. (2020). COVID-19 and Border. Retrieved September 22, 2020 from https://ca.bbcollab.com/collab/ui/session/playback

- Calzada, I. (2020). Will Covid-19 be the end of the global citizen? Retrieved September 22, 2020 from https://apolitical.co/en/solution_article/will-covid-19-be-the-end-of-the-global-citizen

- Carson, L., & Gerwin, M. (2018). Embedding Deliberative Democracy in Poland. Retrieved October 21, 2020 from https://newdemocracy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/docs_researchnotes_2018_May_nDF_RN_20180508_EmbeddingDeliberativeDemocracyInPoland.pdf

- Cavallaro, F., & Dianin, A. (2019). Cross-border commuting in Central Europe: Features, trends and policies. Transport Policy, 78, 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.04.008

- Decoville, A., Durand, F., Sohn, C., & Walther, O. (2013). Comparing cross-border metropolitan integration in Europe: Towards a functional typology. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 28(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2013.854654

- Dołzbłasz, S. (2015). Symmetry or asymmetry? Cross-border openness of service providers in Polish–Czech and Polish–German border towns. Moravian Geographical Reports, 23(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1515/mgr-2015-0001

- Dryzek, J. (2009). Democratization as deliberative capacity building. Comparative Political Studies, 42(11), 1379–1402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009332129

- Dryzek, J. (2016). Institutions for the Anthropocene: Governance in a changing earth system. British Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 937–956. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000453

- Dryzek, J., & Stephenson, H. (2012). Global democracy and earth system governance. Ecological Economics, 70(11), 1865–1874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.01.021

- Durà Guimerà, A., Camonita, F., Berzi, M., & Noferini, A. (2018). Euroregions, excellence and innovation across EU borders. A 515 catalogue of good practices. Department of Geography, UAB.

- Engl, A., & Wisthaler, V. (2020). Stress test for the policymaking capability of cross-border spaces? Refugees and asylum seekers in the Euroregion Tyrol–South Tyrol–Trentino. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 35(3), 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2018.1496466

- European Observation Network for Territorial Development and Cohesion (ESPON). (2018). Crossborder Public Services—Final Report-Practical Guide for Developing Cross-border Public Services. Retrieved September 20, 2020 from https://www.espon.eu/CPS

- Eurostat. (2019). People on the move. People on the Move. Statistics on Mobility in Europe. Retrieved May 14, 2021 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/digpub/eumove/index.html?lang=en

- Evrard, E., & Engl, A. (2018). Taking stock of the European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC): from policy formulation to policy implementation. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European Territorial Cooperation. The Urban book series (pp. 209–227). Springer.

- Fiedorowicz, C. (2020). Pismo do Premiera w sprawie ruchu transgranicznego. Retrieved December 3, 2020 from http://federacjaeuroregionow.eu/news/78.

- Frątczak-Müller, J., & Mielczarek-Żejmo, A. (2020). Networks of cross-border cooperation in Europe–the interests and values. The case of Spree–Neisse–Bober Euroregion. European Planning Studies, 28(1), 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1623972

- Gadomska, P. (2020). Granica zamknięta dla polskich pracowników. Jak wygląda nowa rzeczywistość? Retrieved June 5, 2020 from https://zgorzelec.naszemiasto.pl/granica-zamknieta-dla-polskich-pracownikow-jak-wyglada-nowa/ar/c1-7633925

- Habermas, J. (1991). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. MIT Press.

- Hamedinger, A. (2011). Challenges of governance in two cross-border city regions: ‘CENTROPE’ and the ‘EuRegio Salzburg–Berchtesgadener Land–Traunstein’. Urban Research & Practice, 4(2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2011.579771

- Heinz, F. F., & Ward-Warmedinger, M. E. (2006). Cross-border labour mobility within an enlarged EU. ECB occasional paper 52. European Central Bank (ECB).

- Hernandez-Morales, A. (2020). Germany to partially close borders with neighbors. Retrieved November 10, 2020 from https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-to-partially-close-borders-with-neighbors/

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2003). Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. The American Political Science Review, 97(2), 233–243. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000649.

- Horobets, N., & Shaban, T. (2020). Ukrainian Cross-Border governance since the beginning of COVID-19. Borders in Globalization Review, 2(1), 62–65. https://doi.org/10.18357/bigr21202019895

- Hypki, K. (2020). W przyszłym tygodniu rozmowy na temat małego ruchu granicznego. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://www.zachod.pl/189381/w-przyszlym-tygodniu-rozmowy-nt-malego-ruchu-granicznego/?fbclid=IwAR0_xya70ZY0MUQb_WTHcwcraxbPtS-Arq586taO_HOuq_5dYockNxNqosk

- Indi. (2020). Samorządy piszą do premiera w sprawie zamknięcia granic dla pracowników. Retrieved December 3, 2020 from https://zwrot.cz/2020/03/samorzady-pisza-do-premiera-w-sprawie-zamkniecia-granic-dla-pracownikow/?fbclid=IwAR3fmf3y_PIzWY3W1DgdUQpuyXzqpIxCn2xpy5ILivVICSgmBRJev7npRIs

- Interpelacje. (2020). Interpelacje, zapytania, pytania i oświadczenia poselskie. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://www.sejm.gov.pl/Sejm9.nsf/interpelacje.xsp

- Jańczak, J. (2020). Re-bordering in the EU under Covid-19 in the First Half of 2020: A Lesson for Northeast Asia? Retrieved November 13, 2020 from https://repozytorium.amu.edu.pl/bitstream/10593/25871/1/130.20202020borders20and20Covid20EU20and%20Asia.pdf

- Jar. (2020). Woidke apeluje o otwarcie granic dla pracowników transgranicznych. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://www.dw.com/pl/woidke-apeluje-o-otwarcie-granic-dla-pracownikC3B3w-transgranicznych/a-53242312?fbclid=IwAR0HbR9Yo5NylrBcjzUuzFTtEgg9bOTv06upLBavPM1TpudqG1k-_Mpq_5c

- Javakhishvili-Larsen, N., Cornett, A. P., & Klatt, M. (2018). Identifying potential human capital creation within the crossborder institutional thickness model in the Rhine-Waal region. In Charlie Karlsson, Andreas P. Cornett, & Tina Wallin (Eds.), Globalization, international spillovers and sectoral changes (pp. 291–328). Edward Elgar.

- Karban, P., Honus, A., & Prouza, V. (2020). Některým firmám chybějí polští pendleři [Some companies miss their Polish commuters]. Retrieved April 20, 2020 from https://www.novinky.cz/domaci/clanek/nekterym-firmam-chybeji-polsti-pendleri-40318545

- Kasperek, B., & Olszewski, M. (2020). Społeczno-gospodarcze skutki zamknięcia polsko-czeskiej granicy dla pracowników transgranicznych w Euroregionie Śląsk Cieszyński w związku z pandemią COVID-19 (Socio-economic consequences of the closure of the Polish–Czech border for cross-border workers in the Euroregion Cieszyn Silesia in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic). Technical report. Stowarzyszenie Olza, Cieszyn. Retrieved May 4, 2020 from http://www.olza.pl/pl/pliki-do-pobrania/

- Keating, M. (1998). The new regionalism in Western Europe: Territorial restructuring and political change. Edward Elgar.

- Klatt, M. (2019). Mobilization in crisis–demobilization in peace: Protagonists of competing national movements in border regions. Studies on National Movements (SNM), 4, 30, 1–30.

- Klatt, M. (2020a). What has happened to our cross-border regions? Corona, unfamiliarity and transnational borderlander activism in the Danish–German border region. Borders in Perspective, 4, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.25353/ubtr-xxxx-b825-a20b

- Klatt, M. (2020b). The Danish–German border in the times of COVID-19. Borders in Globalization Review, 2(1), 70–73. https://doi.org/10.18357/bigr21202019867

- Kramsch, O., & Hooper, B. (2004). Cross-border governance in the European Union. Routledge.

- Lang, T. (2012). Shrinkage, metropolization and peripheralization in East Germany. European Planning Studies, 20(10), 1747–1754. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.713336

- Lee, K., Worsnop, C. Z., Grépin, K. A., & Kamradt-Scott, A. (2020). Global coordination on cross-border travel and trade measures crucial to COVID-19 response. Lancet (London, England), 395(10237), 1593–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31032-1

- Mansbridge, J., Bohman, J., Chambers, S., Christiano, T., Fung, A., Parkinson, D., Thompson, D. F., & Warren, M. E. (2012). A systemic approach to deliberative democracy. In J. Parkinson, & J. Mansbridge (Eds.), Deliberative democracy at the large scale (pp. 1–26). Cambridge University Press.

- Medeiros, E. (2011). (Re)defining the concept of Euroregion. European Planning Studies, 19(1), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.531920

- Medeiros, E., Ramíréz, M. G., Ocskay, G., & Peyrony, J. (2020). Covidfencing effects on cross-border deterritorialism: The case of Europe. European Planning Studies, 29(5), 962–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1818185

- Medve-Bálint, G., & Svensson, S. (2013). Diversity and development: Policy entrepreneurship of Euroregional initiatives in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 28(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2013.770630

- Miera, F. (2008). Long term residents and commuters: Change of patterns in migration from Poland to Germany. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 6(3), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/15362940802371028

- Olza. (2020). Covid-19 a pracownicy transgraniczni. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from http://www.olza.pl/pl/aktualnosc/20200418/1236/covid-19-a-pracownicy-transgraniczni-opracowanie-analityczne-i-wystapienie-do-prezesa-rady-ministrow?fbclid=IwAR03XBZOH5bdMs0fSLRqE-EUGBeGkxYzfUiYUctTpLMKyIFGkKMDKDMsoa4

- Opiłowska, E. (2021). The COVID-19 crisis: The end of a borderless Europe? European Societies, 23(sup1), S589–S600. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1833065

- Perkmann, M. (2002). Euroregions: Institutional entrepreneurship in the European Union. In M. Perkmann, & N. L. Sum (Eds.), Globalization, regionalization and cross-border regions (pp. 103–124). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Perkmann, M. (2003). Cross-border regions in Europe: Significance and drivers of regional cross-border co-operation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776403010002004

- Peters, B. (1993/2008). Law, state and the political public sphere as forms of social self-organization. In H. Wessler (Ed.), Public deliberation and public culture: The writings of Bernhard Peters, 1993–2005 (pp. 17–32). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Peters, B. (1997/2008). On public deliberation and public culture. In H. Wessler (Ed.), Public deliberation and public culture: The writings of Bernhard Peters, 1993–2005 (pp. 68–118). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pires, I. (2020). The Portuguese–Spanish border … back again? Borders in Globalization Review, 2(1), 82–85. https://doi.org/10.18357/bigr21202019871

- Plangger, M. (2019). Exploring the role of territorial actors in cross-border regions. Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(2), 156–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1336938

- Redakcja. (2020). Głos pisze do premiera w sprawie pracowników transgranicznych. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://beskidzka24.pl/glos-pisze-do-premiera-w-sprawie-pracownikow-transgranicznych/?fbclid=IwAR2Nk5C3PGcm-_u7cn_xuzDFubZprJFzg1yWD8ZINMLCL_emlPQmRheLKcc

- RPO. (2020). Koronawirus. RPO w obronie pracowników przygranicznych. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://bip.brpo.gov.pl/pl/content/koronawirus-rpo-w-obronie-pracownikow-przygranicznych?fbclid=IwAR13ZaNfhajPyJBpZ5eONZ9uCs6NQsKEOCAFDuMJrOzCPCnkp5gMvvIM4aQ

- Samiec, J. (2020). List otwarty Biskupa Kościoła do Premiera RP ws pracowników transgranicznych. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://ewangelicy.pl/2020/04/29/list-otwarty-biskupa-kosciola-do-premiera-rp-ws-pracownikow-transgranicznych/?fbclid=IwAR1nJ9hFlHJKhzgMKySjrk-kJYCI52b7fYJyNbm6aYR-phnyrqtwnmsFNdc

- Schmidt, V. A. (2010). Taking ideas and discourse seriously: Explaining change through discursive institutionalism as the fourth ‘new institutionalism’. European Political Science Review, 2(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577390999021X

- Scott, J. W. (1999). European and North American contexts for cross-border regionalism. Regional Studies, 33(7), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078657

- Scott, J. W. (2016). European crisis and its consequences for borders and cooperation. In J. W. Scott, & M. Pete (Eds.), Cross-border yearbook 2016 (pp. 5–8). European Institute of Territorial Co-operation.

- Sielker, F. (2020). The EU Commission’s proposal for a European Cross-border Mechanism (ECBM) – What happened? Retrieved February 23, 2021 from https://www.regionalstudies.org/news/the-commissions-proposal-for-an-ecbm/

- Sohn, C., & Reitel, B. (2013). The role of states in the construction of cross-border Metropolitan regions in Europe. A scalar approach. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776413512138

- Stanley, B. (2019). Backsliding away? The quality of democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 15(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v15i4.1122

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2017). Tourism and cross-border regional development: Insights in European contexts. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 1013–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1291585

- Suteu, S. (2019). The populist turn in Central and Eastern Europe: Is deliberative democracy part of the solution? European Constitutional Law Review, 15(3), 488–518. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019619000348

- Svensson, S. (2020). Resistance or acceptance? The voice of local cross-border organizations in times of re-bordering. Journal of borderlands studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2020.1787190

- Szmigiel-Rawska, K., & Dołzbłasz, S. (2012). Trwałość współpracy przygranicznej. CeDeWu.

- Telò, M. (2013). European Union and new regionalism: Regional actors and global governance in a post-hegemonic era. Ashgate.

- Tyrna, B. (2020). Rozmowa. Z Bogdanem Kasperkiem o tym, jak Euroregion walczy o pracowników transgranicznych (The interview with Bogdan Kasperek about the activities of Euroregion in the fight on cross-border workers). Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://zwrot.cz/2020/04/rozmawiamy-z-bogdanem-kasperkiem-o-tym-jak-euroregion-walczy-o-pracownikow-transgranicznych/?fbclid=IwAR3k2Q-f0XtTc31EDRlJz-4v9JeSF6WfNqSCKwBxNaK1Kf7xT6N1KI3I6dA

- Ulrich, P. (2020). Territorial cooperation, supraregionalist institution-building and national boundaries: The European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) at the eastern and western German borders. European Planning Studies, 28(1), 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1623974

- Unfried, M. (2020). Cross-border governance in times of crisis. First experiences from the Euroregion Meuse-Rhine. The Journal of Cross Border Studies in Ireland, 15, 87–97.

- van der Velde, M., Sijtsma, D., Goossens, M., & Maartense, B. (2021). The Dutch–German border: Open in times of coronavirus lockdowns. Borders in Globalization Review, 2(2), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.18357/bigr22202120205

- Wanat, Z., & Mischke, J. (2020). Polish corona-crackdown on commuters hits health and food sectors. Politico, April 23. Retrieved September 15, 2020 from https://www.politico.eu/article/poland-coronavirus-crackdown-on-commuters-hits-health-and-food-sectors/

- Warleigh-Lack, A., Robinson, N., & Rosamond, B. eds. (2011). New regionalism and the European Union. Dialogues, comparisons and new research directions. Routledge.

- Wassenberg, B. (2020). ‘Return of mental borders’: A diary of COVID-19 closures between Kehl, Germany, and Strasbourg, France. Borders in Globalization Review, 2(1), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.18357/bigr21202019886

- Wspólne stanowisko. (2020). Wspólne stanowisko niemieckich prezydentów Euroregionów Pomerania, Pro Europa Viadrina, Sprewa-Nysa-Bóbr i Nysa w sprawie aktualnej sytuacji na polsko-niemieckiej granicy. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://www.facebook.com/EuroregionSpreeNeisseBober/photos/pcb.2265588093737327/2265586460404157

- Zukauskaite, E., Trippl, M., & Plechero, M. (2017). Institutional thickness revisited. Economic Geography, 93(4), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1331703

- Zygiel, A. (2020). Premier Saksonii krytykuje polski rząd za obowiązek kwarantanny. Retrieved December 3, 2021 from https://www.rmf24.pl/raporty/raport-koronawirus-z-chin/polska/news-premier-saksonii-krytykuje-polski-rzad-za-obowiazek-kwaranta,nId,4461818#crp_state=1