ABSTRACT

The specific historical and political context of Northern Ireland has contributed to the development of an expansive visual landscape conveying symbolic meanings and messaging through words, pictures and colours. Murals, posters and graffiti are common ways in which this is seen, drawing a link between the past and the present, with real-time political developments not only inspiring new additions to this landscape but also shaping how existing images are understood in a contemporary context. Brexit, in interacting so intimately with matters of identity, economics, politics and the ‘constitutional question’ in Northern Ireland, has been one such development. This paper presents key findings from a study in which Brexit’s impact on the visual landscape in Northern Ireland was traced between March 2019 and June 2020. Through close analysis of images gathered from across Northern Ireland, alongside consideration of political developments during this time and desk-based research, we examine not only the emergence of Brexit in such imagery, but also what this unveils about the interaction between Brexit and localized perspectives on its impact with regard to politics across the spectrum, and across different parts of Northern Ireland.

1. INTRODUCTION

On 23 June 2016, a referendum was held on the UK’s continued membership of the European Union (EU). This was a fiercely contested vote, with campaigns mounted to gather support for both potential outcomes. A decision was returned to leave, by a result of 52% to 48%, from a turnout of 72.2%. Northern Ireland was one of the areas of the UK that did not vote for this outcome, with 56% voting to remain and 44% to leave (BBC, Citation2016).

In this paper, we explore the changing ways in which identity, local politics and Brexit have interacted to reflect altering dynamics throughout the Brexit process, and how these have influenced Northern Ireland’s visual landscape through murals, political imagery and other forms. This work was undertaken as part of a wider interdisciplinary study on Brexit and identity in Northern Ireland over an 18-month period examining legal, political and social dynamics of Brexit’s outworking in the wake of the referendum result.Footnote1

In tracing this development, we compiled a database of photographs between March 2019 and June 2020 gathered as part of a visual ethnography (Pink, Citation2013).Footnote2 This included images of murals, graffiti, billboards, signs and other means through which the complex dynamics of Brexit were presented from different perspectives, and in different locations across Northern Ireland. We engaged in an interpretative, reflexive analysis of these images (Alejandro, Citation2021; Bleiker, Citation2017). A selection of these images is presented and analysed herein, with a view to advancing current understanding of how the elements of this complex scenario interacted with each other during the research period, which fell before the exit arrangements between the UK and the EU had been agreed.

First, we provide some context to our study with an overview of key aspects of the Brexit debate within Northern Ireland during the period of research. We then consider existing literature on visual imagery in Northern Ireland and how this can be seen to relate to Brexit-specific imagery. From this basis, loyalist and republican imagery and the presence (or lack thereof) of visual imagery for ‘other’ groups is analysed. We then examine the interplay between Brexit and localised economic matters. We conclude by offering some explanations as to how and why Brexit politics and Northern Ireland’s politics have interacted in the ways observed.

2. NORTHERN IRELAND AND BREXIT IN CONTEXT

From the outset, the dynamics of the Brexit referendum in Northern Ireland were distinct to those at play elsewhere. Northern Ireland, in sharing a land border with the Republic of Ireland, would become the site of the UK–EU interface. This approach to Brexit entailed that a border of some description was inevitable on the island of Ireland, which for historical, political and inherently practical reasons was a profoundly unattractive alternative to EU membership for some in Northern Ireland. At the same time, the compelling ideas of UK unity and sovereignty which had underpinned the sizeable number of votes in Northern Ireland in favour of leaving the EU prioritized the East–West relationship and the protection of ties with Great Britain (GB). From this perspective, the concept of a border in any form between Northern Ireland and GB was also not desirable. It was also not an attractive proposition for the UK to maintain a level of alignment with the EU such that any border solution would be akin to the seamless operation of the Single Market as enjoyed by member states. As such, it was unavoidable that a border in some form would have to be established, and at the time this research commenced, the form that this would take was still unknown. The uncertainty of this situation, which spoke and continues to speak directly to the fundamental basis of historical distinction between the unionist and nationalist communities in Northern Ireland, meant that what Brexit represented gave rise to symbolic disturbances from the beginning.

Given Northern Ireland’s history, these were more than merely flash-pan concerns that were likely to fade over time. They were legitimate sentiments and fears, and manifestations of the specific history and politics of the region, both of which are distinct if inextricably intertwined with those found elsewhere in the UK. Further, the divisive impact of the referendum campaigns and the eventual result added to growing concerns that Brexit could undermine the relative peace that Northern Ireland had come to know since the signing of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement 1998 (GFA). In the most fundamental of ways, Brexit posed a threat to the basis of peace in Northern Ireland by re-energizing debate on the region’s constitutional future (i.e., Irish reunification or continuance as part of the UK) in a way that was rendered unnecessary when both places were within the EU (Cochrane, Citation2021, pp. 291–292). The options Brexit entailed meant that there would unavoidably be practical differences seen to some degree in everyday life, something which has since been reinforced with the detail of the UK’s exit and future relationship with the EU having been established through the Withdrawal Agreement, its Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, and the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA).

That it appeared from early in the process that some of these changes could be either exacerbated or mitigated depending on an individual’s Irish or British citizenship further intensified the need for reflection and conversation on the interaction between political aspirations for Northern Ireland and Brexit-related ambitions. A key example of this was seen in relation to accessing rights as an EU citizen post-Brexit, which from an early stage indicated that holding an Irish passport would be advantageous (de Mars et al., Citation2020, pp. 7–14). In the Northern Irish context, where holding one of either or both passports can be as much a statement about one’s identity as it is a practical device, there is often a symbolic weight attached to the outward expression of identity as being Irish or British in this way. Inherently, considerations of this kind prompted by Brexit pushed questions not only of constitutional preferences back into the foreground, but also much more intensely personal questions around identity into the public discourse in a way that had not been necessitated in the years since the signing of the GFA.

Brexit was never simply a question of leaving or remaining within the EU – it exposed cracks in Northern Ireland’s foundations which had hitherto been tacitly plastered over and built atop of. The referendum itself demonstrated this, with nationalist political parties campaigning to remain in the EU and most unionist parties encouraging support to leave (Murphy, Citation2016; Murphy, Citation2018). Sinn Féin and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), respectively at the extremes of Northern Ireland’s political spectrum, were central to these movements (Cochrane, Citation2020, pp. 16–46). But in the same way that the options in response to the referendum question presented a binary choice, so, too, did the referendum have a binary impact in Northern Ireland, which ultimately fell broadly along the historical lines of unionism and ationalism.

Against this backdrop, much of the campaign material relating to the referendum in Northern Ireland also entailed messaging derived from the local political landscape, with the pro- and anti-Brexit positions consolidated largely within unionist and nationalist communities, respectively. These positions were communicated through usual means such as leaflets posted to homes, but also through imagery in public spaces, such as billboards, posters and murals. Communication through visual means in public spaces, such as conveying political messages, demarcating geographical areas as belonging to one community and depicting historical figures or events, for example, far predate the Brexit referendum (e.g., Hill & White, Citation2012). The binary choice that the referendum demanded, when mapped onto this context, gave rise to a uniquely nuanced way in which Brexit was depicted, explained and presented in the Northern Irish context. It showed that Brexit politics and local politics were interacting, and demonstrated how this interaction was perceived differently through the lens of specific communities. This is placed in especially stark contrast with elsewhere in the UK. The decisions of ‘leave’ and ‘remain’ were mapped onto a political model of left–right alignments; debates and discourse centred on issues such as immigration, fiscal advantages, parliamentary sovereignty, and distinction from EU law and its structures. The prevalent ‘constitutional question’ for the UK was one of a future within or external to the EU; for Northern Ireland, it was ostensibly one of a future with closer alignment to Ireland or GB. Arguably, Scotland presented somewhat of an exception to this, with its own constitutional debate shaping the Brexit narrative there (McEwen, Citation2018). Again, this highlights the variegated approach adopted across the UK with regard to the Brexit referendum and through the ensuing processes, and demonstrates Northern Ireland’s unique position within that.

3. VISUALIZING BREXIT

Visuality, visual politics, and visual methods have gained increasing traction within the international relations and politics disciplines, particularly as a means of understanding the ways in which what is seen and how it is seen shape understandings of the state, the political, and international relations more broadly (Bleiker, Citation2001, Citation2017; Campbell, Citation2003, Citation2007; Moore & Shepherd, Citation2010; Williams, Citation2003). The visual (or aesthetic) turn has had profound impacts on these disciplines and their subdisciplines, bringing attention to how images can be used to communicate, to galvanize and to produce the field of intelligible practice (Hansen, Citation2011; Williams, Citation2003). Bringing the visual in challenges the idea that the political exists ‘in an a priori way’ (Bleiker, Citation2001, p. 510) where images reproduce an already existing politics – rather, engagement with visual politics suggests an understanding of the visual as performing the political (Bleiker, Citation2014). The visual turn allows research to reflect more expansively about the political, forcing attention to nuance, contextuality and the importance of affect (Bleiker, Citation2017).

Research on the visual representations of identity pertaining to conflict in Northern Ireland is not in and of itself novel, particularly in relation to political murals (e.g., Davies, Citation2001; Hill & White, Citation2012; Lisle, Citation2006; Rolston, Citation1987, Citation2003; Vannais, Citation2001). Murals depict the political climate of the time they were created, make connections across space and time, and/or enhance the visibility of certain groups. Importantly, public art communicates its environment, and its changing nature can materialize tensions and transitions in a given historical moment. Murals themselves may also be temporary installations, eventually destroyed when their purposes have been served (Rolston, Citation2004, p. 44). Ní Éigeartaigh (Citation2011, p. 46) describes the purpose of murals in particular as being comparable with that of graffiti – in altering the environment into which they are added, this imagery serves to materially mark the political terrain. Political murals are only one way in which visual narratives of Northern Irish politics are captured; kerbstones, houses, and other everyday features are also places commonly transformed into sites of political communication and storytelling (Brown & MacGinty, Citation2003, p. 95). We consider these forms of public art on equal footing, in line with Lisle’s (Citation2006, p. 32) arguments that contestations of ‘real’/legitimate versus illegitimate art forms is depoliticizing, and that the value of art is not purely its aesthetic value but its political power.

Our consideration of the visual politics of Brexit began with thinking about the relationship between identity politics and the state. This was in part because of the nature of political divisions in Northern Ireland, and in part because Brexit is inextricably tied to understandings of UK statehood. We were therefore curious to see if Brexit impacted upon the visual language used to reproduce or challenge Northern Ireland’s relationship to the UK, the EU and to Ireland, and what form those impacts took – whether temporary (such as flyers or stickers) or more permanent. We also sought out examples of political communication that did not neatly fit into the ‘two communities’ frame and spoke to other kinds of politics that may not be directly aligned with this dominant, neatly binary understanding of Northern Irish politics. This work was undertaken as part of the aforementioned wider project in which matters of governance and identity in Northern Ireland in the context of Brexit were examined. As part of this research, we completed a series of interviews and focus groups in tandem with the development of our visual repository, and our thinking around these visual artefacts is indebted to this wider body of work.

In undertaking this research, we took seriously Bleiker’s (Citation2014) reflections on the methodologies of visual politics, specifically the deployment of a plurality of methods. We approached our study of the visual politics of Brexit from a position of methodological plurality. Our analysis is fundamentally interpretive, but it is an interpretative analysis deeply committed to reflexivity (Alejandro, Citation2021; see also Bleiker, Citation2017, p. 258). This involved a foregrounded understanding of how our identities, as researchers and as a team comprising individuals who may be read either as insiders or outsiders, would shape not only our understandings of the symbols analysed here in how they are seen and read, but the knowledges reflected and produced by them (Pink, Citation2013, p. 24). Data-gathering was undertaken through Pink’s (Citation2013) understanding of visual ethnography and Pink et al.’s (Citation2010, p. 4) walking-as-method, which foregrounds the visual ‘as always contextualised through the multisensoriality and mobility that characterise everyday experience’. Following Pink et al.’s argument that walking is both ‘embodied, and emplaced’ (p. 4), we approached each artefact as it was intended to be approached – with movement, considering public art as something to be seen in the context of mobility through spaces. Interpreting these images began in these moments of approach and continued as we walked away, considering their location, their accessibility and the narratives they invoked.

We sought imagery related to the EU, Brexit and perspectives on both between March 2019 and June 2020. We were interested in how these views mapped against community-based arguments for and against EU membership and in relation to the constitutional future of the region. Where these representations predated the Brexit referendum, as much of the imagery in the form of murals across Northern Ireland does, we considered how current political dynamics may influence how these images were read. In many cases, the potential for contemporary (re)interpretations of these images reflects a certain timelessness to the specific politics of Northern Ireland, while simultaneously demonstrating the potential for new perspectives to emerge – in other words, these artefacts move back and forth through time, bringing the past into the present political context, and reading the present through narratives of the past. Equally, the focus on visual artefacts allowed us to consider how perspectives not tied to community politics may assert themselves in ways that might otherwise have been missed, such as advertisements and billboards.

Analysis of the visual artefacts selected followed the same commitments as the data collection itself. We undertook an interpretive analysis, whereby the intention is not to uncover a singular or objective true meaning behind each artefact, but to approach ‘a sense of meaning and coherence to works through meaningful engagement with both text and context’ (Moore & Shepherd, Citation2010, p. 303). While indebted in some ways to content analysis, this interpretative analysis is not focused primarily on the patterns of representation as such (Bleiker, Citation2014), but rather is concerned with its affective qualities and its co-constitution of political dynamics.Footnote3 This meant critically assessing what we, as researchers, considered to be valuable sites of knowledge production, tracking research notes from the fieldwork that captured initial impressions and affective experiences, and exploring in conversation the layers of meaning that could be uncovered in each artefact. These engagements involved reading and re-reading the artefacts in and out of context, a process which remains ongoing.

The images we present herein concern direct engagement with Brexit, firstly in the form of murals and billboards aligned with unionism/loyalism and nationalism/republicanism respectively, and a mural not specifically aligned with either community. We have selected these images in particular from our dataset in order to highlight the ways in which Brexit is brought into and negotiated through the specific politics of Northern Ireland. The final set of images suggests an engagement with the temporality of Brexit and its politics, specifically its impact on the material futures of life on and around the border with Ireland and preparations for that future. These images were selected to reflect upon the ways in which the past in Northern Ireland is narrativized in the contemporary moment, and to illustrate the quieter narratives of engagement with Brexit that are less likely to garner attention. We present these images in what follows, along with a discussion of their context, and how we understand them to both reflect and produce political meaning.

4. BREXIT POLITICS AND NORTHERN IRELAND

The framing of Northern Irish politics as a discussion of two communities has been described and critiqued as a 'bipolar' approach to community and identity (Graham & Nash, Citation2006, p. 266). This leaves firmly to one side the range of ‘other’ and ‘othered’ communities such as migrants, those for whom another identity characteristic takes precedence, and those who do not (strongly or at all) identify with either nationalism or unionism (Agarin et al., Citation2018). Nonetheless, the ‘two communities’ narrative does strongly assert itself over symbolism in Northern Ireland, prevailing for reasons of community organizing, traditions of political expression across different contexts (where flags and murals rank particularly highly in the expressions of the two communities), and in terms of segregated housing (creating homogenized community spaces).

Visual assertions of political positions on Brexit abounded not only in the run-up to the 2016 referendum but also throughout the negotiations and transition period (Coutto, Citation2020). These ranged from placards and stickers to the more notorious images deployed by, for example, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) (Ross & Bhatia, Citation2021). Some of these images played on existing divisions and racialized tensions over immigration and access to the National Health Service (NHS), but in ways that were steeped in the specific contextualization of the Brexit referendum and the EU. We were interested in the extent to which the specific political situation of Northern Ireland would or would not be reflected in public art and imagery in the post-referendum period. The political visual culture observed is examined here from three perspectives: unionism and loyalism; nationalism and republicanism; and economic. Each perspective unveils different ways in which the Brexit debate was framed, and together, they present a picture of the complex interconnectedness that emerged between Brexit politics and visual representations of identity in the region. When considered together, these perspectives show that Brexit became subsumed within the existing parameters of politics and society in the case of Northern Ireland to a significant extent, but additional considerations reveal the ways in which life removed from this dominant narrative still continued.

4.1. Loyalism’s symbolic assertions over Brexit

is a photograph of a streetscape in a residential Loyalist area known as Tigers Bay, located ten minutes from central Belfast and situated close to Belfast docks.

Multiple important features can be seen that depict loyalist perspectives, providing a visual foundation for pro-Leave sentiment within this community. The foreground shows the painted bollards and kerbstones in red, white and blue – the colours of the Union flag. Kerbstone painting has been used here to demark territory and affiliation, and the use of colour on the kerbstones and bollards in addition to the name painted on the wall clearly mark the area as loyalist territory. The second feature is a smaller mural to the left which includes a crown, two Union flags, an ornate bible, a red hand and a dagger. All these are traditional emblems within loyalism and of allegiances to the queen, political unionism as well as unionist ideals, and religion. Two bible verses are cited in the top left and right of this mural, one of which references the prophecy of Jesus’ birthFootnote4 and another which relates to the longevity of God’s promises to his protected people.Footnote5 The third feature is the most visually dominant: the commonly used name of the area with a clear assertion of its politics attached: ‘Loyalist Tigers Bay’.

A secondary, but still dominant, theme is remembrance of the World Wars and, perhaps specifically, given the reference to the Armistice, remembrance of the First World War. Remembrance symbols as featured here bridge the past to present in particular ways, beginning with the poppy. The poppy is a particularly important part of this image, not least because of its visual prominence – for all its controversy across the UK, the poppy is especially divisive in Northern Ireland as it is often seen as ‘an emblem of Britishness’ (Fox, Citation2014, p. 28; see also Brown & MacGinty, Citation2003; Mac Ginty & Darby, Citation2001) deployed by unionists. It draws out certain narratives of militarized national loyalty . McVeigh and Rolston (Citation2009, p. 22) argue that the poppy ‘conflates … the terrible waste of lives in the first world war and a reassertion of the moral rightness of the war against Nazism [as it] uncritically celebrates contemporary British militarism’. The theme of militarism remains present here, in the poppy as a traditional (and contested) symbol of remembrance, the silhouettes of soldiers with bowed heads, colours in the mural evocative of bloodshed, and the words ‘lest we forget’ all further reinforce this militarized remembrance theme. There is a further reference to the bible, the text of which reads ‘Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.’Footnote6

The fourth element of this visual compilation draws on Brexit. There is a clear relationship to the previous elements both in terms of its proximity and the repetition of their symbolism. The major feature is the text ‘Vote Leave E.U.’. This is joined by a further depiction of a Union flag in the shape of a shield, and a further reference to the Bible:

Then I heard another voice from heaven say:

‘Come out of her, my people,

so that you will not share in her sins,

so that you will not receive any of her plagues … .’

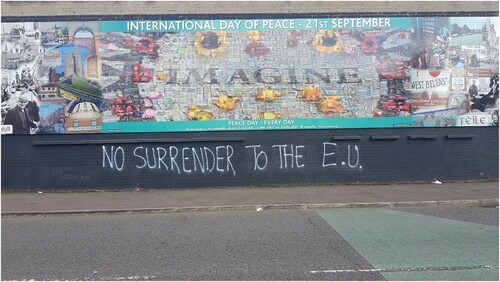

Other visual aspects observed during the fieldwork period included the graffitied words ‘No Surrender to the E.U.’ beneath a peace mural in an interface area of west Belfast (). The ‘no surrender’ motif is long established in the history of unionist politics (McAuley, Citation2004; Todd, Citation1987) and also featured during a pro-Brexit speech by Ian Paisley MP outside the Houses of Parliament (Irish News, Citation2018). It is reminiscent of battle and is a combative phrase, implying that a unifying feature of the community is a sense of collective necessity to defend as a unit from an enemy. The introduction of Brexit into this suggests a necessity for a similar approach to be taken to Brexit, and that the threats of remaining within the EU are tantamount in some ways to threats posed to this community and its geopolitical spaces by members of collectives sharing a contrasting view.

While Brexit itself did not present a violent interface in Northern Ireland, the visual depiction of Brexit seemed to imply a synergy between these historic sentiments and this new constitutional debate, and maintained an embedded militarism across artefacts and locations.

4.2. Republicanism’s symbolic assertions over Brexit

In the same manner that Brexit symbolism has been seen to interact with traditional loyalist/unionist visuals, republican/nationalist causes have similarly mixed the two, albeit in different ways. Placards situated at the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland and in border towns placed a stronger emphasis upon border politics and constitutional implications in the Brexit debate, resituating them within a broader and more traditional politics surrounding the border on the island. This is perhaps unsurprising given the density of the nationalist population in the border areas, and in light of every constituency along the border having voted in the majority for ‘Remain’ in the 2016 referendum.

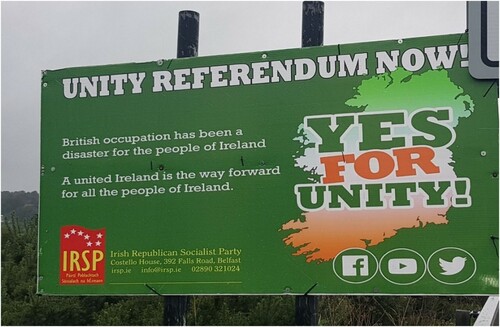

This latter form of nationalist politics shifts focus from the technically rendered Brexit issues of hard and soft borders, which is more prevalent in Brexit imagery present in Belfast and other areas away from this boundary, towards the legitimacy of a border per se and calls for a border poll or ‘unity referendum’. This is demonstrated in , which shows an example of such a placard situated on a bridge crossing the River Foyle which divides Strabane (in Northern Ireland) from Lifford (in the Republic of Ireland). Its message is relatively straightforward: ‘British occupation has been a disaster’, ‘a united Ireland is the way forward’ and ‘unity referendum now’.

This message is reflected in , a photograph taken in Newry which is situated at the opposite end of the border region and is considered a halfway point geographically between the cities of Belfast and Dublin. In the tone and word choices of the text, it is clear that this is not intended to be a compromising or alliance-building message, but rather to speak to what is largely an already-onside political base in these areas, as reflected in the political representation of border constituencies in the Northern Ireland Assembly and Westminster. Further, the tone is less akin to sharing a message as it is to encouraging those of a similar persuasion to become active in the pursuit of these aims, presenting a clear connection between the negative consequences of Brexit and Irish reunification as a means of avoiding these.

Figure 4. One of several posters placed around the border town of Newry, June 2020.

Note: The text in Irish states, ‘It is time for unity.’

There are multiple dynamics at play with both of these images. For example, the contentious use of the word ‘occupation’ to refer to Northern Ireland’s status within the UK, a reference to the ‘people of Ireland’ reflecting the refusal within the republican community to use the term ‘Northern Ireland’, and even the colour palette which is in the colours of the Irish flag. The logo and contact details of the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) in are included to indicate it as the organizer of the placard campaign. This group has (alleged) past connections to violent activity (Smith, Citation2002, p. 90). The IRSP also supports Brexit and the withdrawal of Ireland from the EU on apparently socialist economic grounds (IRSP, Citation2018), and produced posters with the slogan ‘Britain Out of Ireland, Ireland out of the EU’.

Other visual artefacts seen during the fieldwork period included a poster with the colours of the UK, Irish and EU flags advertising an event on ‘Ireland, Brexit and the Left’, which was organized by Socialist Democracy; the event shares a title with a brief released by the organization detailing their position (McAnulty, Citation2019). Posters from Sinn Féin with the text, ‘50 years on … Brexit is an attack on our rights’ were also widely visible, with the ‘50 years on’ text recalling the period since the beginning of the Troubles and the deployment of British forces to Northern Ireland. This is consistent with Sinn Féin’s oppositional position to Brexit, holding that Brexit would further divide Ireland (Bardon, Citation2015). Seen in this light, it is perhaps unsurprising that Brexit does not consume these organizations’ larger political focus, and instead is instrumentalized as an additional political tool in traditional disputes.

What this reinforces is, first, the reconfiguration of how fundamental issues are approached as a result of Brexit, including the challenges of a hard border being implemented on the island of Ireland. This was especially present in the border region, where the consequences of a hard border would have been most acutely felt in everyday life. Second, it highlights the way in which Brexit became ensconced in party politics in Northern Ireland – in contrast to national-level UK politics where there were clear internal party divisions (e.g. Kenny & Sheldon, Citation2020), Brexit in Northern Ireland did not produce the same ructions.

Arguably, in a system where intra-group political competition exists in the way it does in Northern Ireland, there is longer term political capital to be gained from being seen to lead in reflecting concerns of the nationalist community at large on Brexit. Investing party funds in producing posters and placards with anti-Brexit and pro-reunification messages, therefore, may not be entirely about Brexit, but inevitably also part of a pragmatic longer term strategy to shore up, in this case, Sinn Féin’s position, as the main party representing the nationalist community. This is accomplished through articulating a route to achieving the nationalist aim of reunification. The poster in illustrates one way in which the political problem of Brexit can be considered to be co-opted by existing political positions and desires in this way.

4.3. ‘Others’ and their symbolic assertions over Brexit

While unionist and nationalist imagery projecting different interpretations of the Brexit debate was certainly abundant, such a picture risks creating an assumption that Brexit was a clear-cut binary issue in Northern Ireland. While unionism and nationalism are still the predominant means of political and social demarcation in Northern Ireland, an increasing proportion of the population does not affiliate along these lines in political and social terms. Elections in 2019 at local government, European and Westminster levels saw a shift in voting patterns, with the so-called ‘Alliance surge’ (referring to the increased share of votes being achieved by the non-aligned Alliance Party in each of these elections) being interpreted by some as reflecting a growth in middle-ground politics at the expense of seats hitherto held by representatives from unionist and nationalist parties, and a movement away from sectarian politics (Hayward, Citation2020; Tonge & Evans, Citation2020).

The extent to which this arose in response to Brexit is debatable, and perhaps even negligible. Other factors such as frustration at political inertia in the Northern Ireland Assembly between 2017 and 2020 (which was itself exacerbated by wider Brexit politics), decreasing distinction between the more centrist unionist and nationalist parties – the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) – and a sense of need for representation on Brexit that did not align to either of the predominant communities, all offer some explanation for this. It was notable in conducting our fieldwork that there was a distinct absence of Brexit-related imagery that spoke directly to those who did not identify along the lines of political unionism and nationalism. Brexit, in being visually cast in terms of constitutional interests, entailed that other perspectives on the debate were obscured.

This does not mean to say that all Brexit-related visual narratives were cast in terms of unionist and nationalist politics in Northern Ireland. We also encountered imagery depicting aspects of the relationship between Northern Ireland’s politicians and political activities at the national level with regard to Brexit, as illustrated by . In Northern Ireland, frustration over the continued political hiatus in the devolved institutions joined with ‘Brexit fatigue’ and, in turn, added tension to the political relationship between Westminster and local political parties. There is an additional mischievousness in this artwork in the caricaturing of Northern Ireland’s politicians as ‘all the same’ in not merely being political opponents but also rivals in a conflict over the national determination of a region emerging from violent conflict.

Figure 5. A cartoon depiction of Boris Johnson MP, Arlene Foster MLA (left) and Michelle O’Neill MLA (right), taken in west Belfast, September 2019.

The image shows a cartoon of Boris Johnson (who was, by then, Prime Minister) in the centre, holding two figures which have the faces of the DUP’s Arlene Foster and Sinn Féin’s Michelle O’Neill. The figures resemble the cartoon pigs Pinky and Perky. The comparison, while clearly unflattering, is intended to draw upon the interchangeability of the cartoon pigs in terms of sound, appearance and name, to suggest an interchangeability of the two politicians who would become First and Deputy First Minister. The two politicians being held in the clutches of Prime Minister Boris Johnson suggests the stalemate between the two parties is due to events at Westminster – in the image, they are being physically manipulated by an infantalized depiction of Johnson. A slight side-eye from the cartoon Foster, whose party were in a Confidence and Supply arrangement with Johnson’s Conservative Party at the time, suggests a closer, if wry, relationship between her and Johnson, than is the case for O’Neill. Johnson is dressed as a school child, implying a childishness and inexperience as had been mooted by political opponents (Tolhurst, Citation2019). The final aspect of note is an EU flag which appears to be in liquid form and to have run down the Johnson’s trouser leg to find a resting place on the floor. The meaning of this aspect is more ambiguous, possibly referring either to the insignificance of the EU to Johnson, to convey a sense of extreme fear on his part, or a combination of the two.

In sum, a greater degree of Brexit-related imagery pertaining to national-level politics was observed in the course of this research than Brexit messaging targeting the political middle-ground. ‘Others’ remained almost wholly unrepresented within these visual stories. This is not, however, to suggest that these politics were entirely erased, even through an apparently all-consuming Brexit discourse.

5. BREXIT IMAGERY BEYOND DOMINANT DISCOURSES

Against the narrative-consuming backdrop of Brexit, the Northern Ireland Assembly ceased to operate following the resignation of Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness in January 2017. Power-sharing collapsed in part over a scandal involving a renewable heat incentive (RHI) scheme (Rice, Citation2020), though other divisions, including legislation regarding the Irish language, were at play and had been growing for some time. The hiatus lasted three years from January 2017 to January 2020, and it was during this period that fieldwork for this project took place. Disruption in Northern Ireland occurred on two fronts during this phase of our research: with regard to increasing pressures on civil servants, who, while granted extra powers, were still restricted in the decisions that could be made in the absence of Executive ministers; and Brexit, which had served to further reify acrimony between the DUP and Sinn Féin in particular (Murray & Rice, Citation2021).

Alongside these challenges and Brexit, life in Northern Ireland continued – issues that had been present before Brexit remained, the quirks of life for people living along the border continued and the challenges of dealing with the past remained just as present. In this sense, Brexit, in the course of the research period, did not bring dramatic changes to the practicalities of everyday life for people living in Northern Ireland; however, a combination of frustrations and anxieties at the, then, unknown outcome of the UK–EU negotiations was evident (Hayward & Komarova, Citation2019). We encountered several examples of instances where Brexit had informed the visual landscape, but where these references were not political or historical in nature. Rather, they engaged Brexit as a tool of opportunity in a commercial sense, in part likely fuelled by these latent uncertainties. They reveal a different, more banal politics of Brexit, and one that figures the material conditions of Brexit beyond the two-communities narrative.

and show two examples of this interaction between Brexit and the lived, material conditions of its impact. While the other kinds of artefacts presented here express passionate views, largely but not limited to assertions of sectarian identities, these images speak a different kind of perspective on Brexit. They capture a quiet kind of resilience, and the extent to which people adapt – in essence, despite the uncertainties of the time, they show the adaptability of people to change, even when that change is as constitutionally significant as our analysis so far has shown Brexit to be for Northern Ireland’s politics. shows a currency exchange shop in Enniskillen that advertised itself as ‘The Brexit Beating Bureau’. This was taken before the UK left the EU, and there was concern that Brexit would have a significant negative effect on the strength of the British pound. The suggestion here is to ‘beat Brexit’ by exchanging currency ahead of the withdrawal date and miss subsequent losses on unchanged currency. shows a mobile billboard advertising a personal storage business that also offers post office boxes and virtual office addresses, for those who may need to have a UK address. Both artefacts are also positioned near to the border with Ireland.

Figure 6. A shopfront banner for a currency exchange in Enniskillen, September 2019.

Note: Business details have been removed from this image.

Figure 7. A mobile billboard near to the Donegal border, September 2019.

Note: Business details have been removed from this image

From these examples, we see the acknowledgement that Brexit will have an impact on the local political economy, but one that is navigable using existing informal infrastructure that emerged in response to cross-border factors predating Brexit. They are a nod to disruption that is not consumed or particularly uniquely impacted by it. Both suggest a sense of mild urgency, a thing to get done ahead of the Brexit deadline, but are rooted in the particular political–economic relationship between Ireland and the UK. They are a kind of banal, but wholly material, preparation for Brexit, whatever that might have been anticipated to look like at the time. In the context of Brexit, and at a time where the uncertainties of what this meant in practical terms were at their peak, these are examples of commercially savvy businesses attempting to benefit from a situation which posed real potential challenges to everyday cross-border life. They were businesses (or at least business models) that were already in operation, so their presence was not in itself a consequence of Brexit – but the way in which they both communicated the purpose of their existence to the wider public is undeniably cast in terms of Brexit.

This was an important finding as it showed that throughout the Brexit process and the considerable disruption and upheaval that it entailed, there was a sense of inevitability that life would continue regardless. Furthermore, it also demonstrated that for some there appeared to be a tangential benefit from Brexit, if approached appropriately. Even in the early days of negotiations between the UK and the EU on the terms of exit, the potential for Northern Ireland to be situated at an advantageous intersection, able to benefit from aspects of both EU and UK trade arrangements was something to which these particular businesses were alert. While the focus on bipartite identity divisions in relation to Brexit prevailed in some areas, the border economy responded to the (impending) challenges in a way that was not necessary elsewhere in Northern Ireland.

6. EXPLAINING THE IDIOSYNCRASIES

Having analysed some of our key findings from different perspectives, to conclude that the specific nuances in visual representation of Brexit in the context of Northern Ireland are solely the result of politics internal to Northern Ireland would be remiss. The complex constitutional arrangement the region finds itself in as part of the UK while operating a peace accord to which Ireland is a co-guarantor, in addition to managing competing aspirations for both greater and lesser constitutional alignment to both polities, implicitly entails that political and social development across both islands bear significance in Northern Ireland. In considering the content of the Withdrawal Agreement and the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland which are now in place, it becomes even more apparent that the fabric of national level politics in Ireland and the UK will become yet more interwoven with the trajectory of political developments in Northern Ireland in the years ahead. This is a key factor in understanding the reasons that visual representations of Brexit in Northern Ireland take the form they do, and how Brexit became at once subsumed within traditional binary politics in contrast to elsewhere in the UK, while simultaneously being understood and produced outside this binary. In many ways, this is reflective of other political struggles in Northern Ireland: for instance, feminist cross-community organization and activism (e.g. O’Keefe, Citation2021).

At the most basic level, Brexit had a very different resonance in every sense in Northern Ireland. Leaving the EU established that, at least to some degree, an external frontier of the EU would run through the island of Ireland. The nationalist community feared that this in very real and in symbolic ways would give rise to a friction reminiscent of the days when the border was policed. Equally, the unionist community was fearful that a withdrawal arrangement treating the island of Ireland as one entity for the purposes of trade would establish a de facto border in the Irish Sea (e.g., Gormley-Heenan & Aughey, Citation2017). For both of these communities, Brexit made the worst possible reality in the eyes of each a tangible reality, and there was nowhere in Northern Ireland more aware of the potential outcomes than the border region (Hayward, Citation2017).

In addition, these potential realities did not present the same options for Northern Ireland as for the rest of the UK. For nationalists in Northern Ireland, the alternative to Irish unity is continuation as part of the UK. For the unionist community, the alternative to a strengthened union is its disintegration and Irish reunification. As such, it follows that for nationalists to achieve their ambition , an increase in activism towards securing a border poll and a vote in favour of reunification would be necessary. Likewise, for unionists to reaffirm loyalty to the UK, active steps towards expressing and encouraging support for this would be required. Brexit presented a clear space for this hardening of mutually distinct constitutional aspirations, and this was evident in the way Brexit was portrayed in the various forms highlighted herein.

Yet at the same time, Brexit may not be solely to blame for a retrenchment of identities and communities in Northern Ireland. While it was evidently divisive, the wider context in terms of devolved politics also contributed to this. For instance, the 2017 Northern Ireland Assembly elections saw a hardening of unionism and nationalism around the DUP and Sinn Féin. This was reinforced at the 2017 General Election, which saw all DUP and Sinn Féin candidates returned with the exception of one (Unionist) independent representative. To an extent, Brexit provided an appropriate backdrop for the existing divisions in Northern Ireland to be re-perpetuated along new lines; however, the response to this localized hardening of positions for the two most diametrically opposed parties, and increasing frustration at their inability to reach a consensus on returning to government, was for attention to move towards the middle-ground during the ‘Alliance wave’ where the party increased their vote share and representation across the 2019 local government, European Parliament and General Elections (Tonge, Citation2020). In this way, the absence of an explicitly articulated ‘middle-ground’ in the visual imagery we encountered does not reflect what was happening within politics at the same time. Instead, the artefacts we encountered that articulate and negotiate a ‘middle-ground’, or at least a position that does not fit neatly into the dominant binary political narrative, focused on an overall frustration (as in ) or material needs around Brexit (as in and ). This suggests that there is more nuance than a binary narrative of Northern Irish politics allows.

In the rest of the UK, the alternatives available are very different. For Scotland, for example, the alternative to UK membership is independence and a potential application to rejoin the EU (McEwen, Citation2018), in contrast to Northern Ireland where the territory would become part of another jurisdiction – and further, one that remains within the EU. Effectively, the options for the constituent parts of Great Britain are to be within or removed from the EU: there are no alternatives. In this way, it becomes clear why the Brexit narrative and expressions of Brexit sentiments in GB did not become imbued in pre-existing political cleavages in the same way as they did in Northern Ireland. While it was, broadly speaking, an issue in and of itself in GB, in Northern Ireland, it was a further complication of an already relatively fragile and complex cross-community dynamic.

In addition, GB was removed from the everyday potential consequences of direct interaction with an EU frontier. While the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland identified an approach to mitigate the consequences of this on the island of Ireland, the challenges that have emerged in EU–UK talks on the implementation of the Protocol, compounded by the UK opting against seeking an extension to the timeframe for achieving this beyond the end of 2020, indicated that there was much uncertainty ahead (Murray & Rice, Citation2020, pp. 22–23).

It is understandable, therefore, that Brexit was so succinctly incorporated into existing political discourse in Northern Ireland, and that the most prevalent of these concerns were projected into visual imagery alongside traditional political representations. Brexit has proven a fractious political moment, dividing politics across the UK along questions of identity and belonging, weaving into the existing political communication of (in)security through the language of already present tensions. As MacGinty and Darby (Citation2001, p. 153) argue, political symbols emerge in such ruptures as ‘a source of comfort and offer a reference to a more stable past’. Brexit reflects a negotiation, and for some a destabilization, of core considerations of a national self (Browning, Citation2019, p. 337), which makes it particularly well-positioned for negotiations to occur through the language of another struggle over national identity and belonging. At the same time, Brexit can be folded into existing political divisions, tensions, and idiosyncrasies that define the particulars of life in Northern Ireland. We see this especially in the political economy of life on the border, where, while Brexit may add a sense of urgency to everyday negotiations, it is not uniquely causal.

7. CONCLUSIONS

Exploring the impact of Brexit in Northern Ireland through the visual representation of different perspectives on it has highlighted the complexity and extent of the challenges that the UK’s departure from the EU has given rise to. The imagery encountered in the course of conducting this research showed that for the most part, messaging about Brexit through visual means was depicted in tandem with broader messaging from party-political perspectives. There was also a link between geographical location and the nature of the messages being projected, most evident in examining the visual landscape of Brexit in border regions. With this focus, there was little space for visual communications that were politically agnostic, and so the ‘others’ and centre-ground citizens received comparatively little imagery targeting them specifically. However, perhaps the most striking finding from this research has been that despite the common characterization of Northern Ireland as a two-community and bipartite place, the cross-cutting issues of equal concern to all citizens did not become lost under the Brexit spotlight.

The way in which the visual landscape of Northern Ireland has amalgamated with Brexit politics has created new or evolving ways for matters relating to the constitutional question in particular to be publicly addressed. Brexit’s polarizing impact was compounded by this binary choice mapping onto what is generally characterized as a binary division in Northern Ireland. The diversity that had been permitted to prosper and develop since the signing of the GFA was confronted with an either/or decision, the ramifications of which were set to permeate politics and society indefinitely regardless of the outcome. The fears, uncertainties, opportunism and pessimism of the situation were evident across the images we encountered in the course of this research. This is not surprising given the interwoven nature of the challenges that Brexit demanded be confronted with the insecurities that exist within both of the predominant communities when the tacit potential for either Irish reunification or continuance as part of the UK comes into such sharp focus. Graffiti with messages of ‘No Irish Sea Border’, anti-GFA sentiments and threats towards staff working to enforce the Protocol at ports in Belfast and Larne have informed calls to remove the arrangements in place (e.g., BBCNI, Citation2021; Rice, Citation2021). The use of visual means to communicate sentiments in public spaces continues to evolve in response to the outworking of Brexit in Northern Ireland.

Undoubtedly, artistic and political use of images in relation to Brexit will continue to emerge, but the crux of this messaging will inevitably take a different character now that the UK is no longer part of the EU and the outworking of the Protocol is in motion. Rather than the fear of the unknown which prevailed during the period of our data collection, it will be reaction to the challenges of the present that will inform this landscape in the times ahead.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

This paper was written by Megan Armstrong and Clare Rice.Footnote7 All three named authors undertook the research and data collection that led to the production of this work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to Professor Colin Murray and Professor Aoife O’Donoghue for their feedback and comments on an earlier draft of this article. Any errors remain our own.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See https://performingidentities.org for further details about this project.

2 These dates were determined primarily by two factors: the period of funding for this research and the Covid-19 pandemic.

3 For a comprehensive content analysis of Brexit-related imagery on Flikr, see Bouko et al. (Citation2018).

4 ‘You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over Jacob’s descendants forever; his kingdom will never end’ (Luke 1: 31–33).

5 ‘Your house and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever’ (2 Samuel 7: 16).

6 John 15: 13.

7 Armstrong moved to Newcastle University in September 2022; Rice moved to the University of Liverpool in November 2021.

REFERENCES

- Agarin, T., McCulloch, A., & Murtagh, C. (2018). Others in deeply divided societies: A research agenda. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 24(3), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2018.1489488

- Alejandro, A. (2021). Reflexive discourse analysis: A methodology for the practice of reflexivity. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120969789

- Bardon, S. (2015, December 24). Sinn Féin to campaign against Brexit in EU referendum. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/sinn-f%C3%A9in-to-campaign-against-brexit-in-eu-referendum-1.2476720

- BBC. (2016, June 24). EU referendum: Results. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/politics/eu_referendum/results

- BBCNI. (2021, February 9). NI ports: What led to checks being suspended on Irish Sea border? https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-55996788

- Bleiker, R. (2001). The aesthetic turn in international political theory. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 30(3), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298010300031001

- Bleiker, R. (2014). Visual assemblages: From causality to conditions of possibility. In M. Acuto & S. Curtis (Eds.), Reassembling international theory (pp. 75–81). Palgrave Pivot.

- Bleiker, R. (2017). In search of thinking space: Reflections on the aesthetic turn in international political theory. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 45(2), 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829816684262

- Bouko, C., De Wilde, J., Decock, S., De Clercq, O., Manchia, V., & Garcia, D. (2018). ‘Reactions to Brexit in images: A multimodal content analysis of shared visual content’ on Flickr. Visual Communication.

- Brown, K., & MacGinty, R. (2003). Public attitudes toward partisan and neutral symbols in post-agreement Northern Ireland. Identities, 10(1), 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/10702890304337

- Browning, C. S. (2019). Brexit populism and fantasies of fulfilment. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32(3), 222–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1567461

- Campbell, D. (2003). Cultural governance and pictorial resistance: Reflections on the imaging of war. Review of International Studies, 29(S1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210503005977

- Campbell, D. (2007). Geopolitics and visuality: Sighting the Darfur conflict. Political Geography, 26(4), 357–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.11.005

- Cochrane, F. (2020). Breaking peace: Brexit and Northern Ireland (1st ed.). Manchester University Press.

- Cochrane, F. (2021). Northern Ireland: The fragile peace (2nd ed.). Yale University Press.

- Coutto, T. (2020). Half-full or half-empty? Framing of UK–EU relations during the Brexit referendum campaign. Journal of European Integration, 42(5), 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1792465

- Davies, L. (2001). Artworks: Republican murals, identity, and communication in Northern Ireland. Public Culture, 13(1), 155–158.

- de Mars, S, Murray, C, O'donoghue, A, & Warwick, B. (2020). Continuing EU Citizenship 'Rights, Opportunities and Benefits' in Northern Ireland after Brexit. Belfast/Dublin: Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission and Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. Available at https://nihrc.org/uploads/publications/Rights_Opportunities.pdf.

- Fox, J. (2014). Poppy politics: Remembrance of things present. In C. Sandis (Ed.), Cultural heritage ethics: Between theory and practice (pp. 21–30). Open Book Publishers.

- Gormley-Heenan, C., & Aughey, A. (2017). Northern Ireland and Brexit: Three effects on ‘the border in the mind’. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117711060

- Graham, B., & Nash, C. (2006). A shared future: Territoriality, pluralism and public policy in Northern Ireland. Political Geography, 25(3), 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.12.006

- Hansen, L. (2011). Theorizing the image for security studies: Visual securitization and the Muhammad cartoon crisis. European Journal of International Relations, 17(1), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066110388593

- Hayward, K. (2017). Bordering on Brexit: Views from Local Communities in the Central Border Region of Ireland / Northern Ireland.

- Hayward, K. (2020). The 2019 general election in Northern Ireland: The rise of the centre ground? The Political Quarterly, 91(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12835

- Hayward, K., & Komarova, M. (2019). The Border into Brexit: Perspectives from Local Communities in the Central Border Region of Ireland/Northern Ireland. https://icban.com/site/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/TheBorderIntoBrexit_Report-Dec-2019.pdf

- Hill, A., & White, A. (2012). Painting peace? Murals and the Northern Ireland peace process. Irish Political Studies, 27(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2012.636184

- Irish News. (2018, February 7). Video: Ian Paisley's shout of ‘no surrender’ to the EU branded ‘insulting’. Irish News. https://www.irishnews.com/news/brexit/2018/02/07/news/video-ian-paisley-shout-of-no-surrender-to-the-eu-branded-insulting–1251272/

- IRSP. (2018, November). Britain out of Ireland, Ireland out of the EU. Irish Republican Socialist Party. https://irsp.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/IRSP-BOOI.pdf

- Kenny, M., & Sheldon, J. (2020). When planets collide: The British Conservative Party and the discordant goals of delivering Brexit and preserving the domestic union, 2016–2019. Political Studies, 69(4), 965–984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720930986

- Lisle, D. (2006). Local symbols, global networks: Rereading the murals of Belfast. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 31(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540603100102

- Mac Ginty, R., & Darby, J. (2001). Guns and government. Palgrave Macmillan.

- McAnulty, J. (2019, August). Things fall apart: Ireland, Brexit, and the left. Socialist Democracy. Socialist Democracy. http://www.socialistdemocracy.org/Ireland,%20Brexit%20Left.pdf

- McAuley, J. (2004). ‘Just fighting to survive’: Loyalist paramilitary politics and the Progressive Unionist Party. Terrorism and Political Violence, 16(3), 522–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546550490509838

- McEwen, N. (2018). Brexit and Scotland: Between Two unions. British Politics, 13(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0066-4

- McVeigh, R., & Rolston, B. (2009). Civilising the Irish. Race & Class, 51(1), 2–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396809106160

- Moore, C., & Shepherd, L. J. (2010). Aesthetics and international relations: Towards a global politics. Global Society, 24(3), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2010.485564

- Murphy, M. C. (2016). The EU referendum in Northern Ireland: Closing borders, re-opening border debates. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 12(4), 844–853.

- Murphy, M. C. (2018). Europe and Northern Ireland’s future: Negotiating Brexit’s unique case. Agenda Publishing.

- Murray, C. R. G., & Rice, C. A. G. (2020). Into the unknown: Implementing the protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland. The Journal of Cross Border Studies in Ireland, 15, 17–28. http://crossborder.ie/site2015/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Final-Digital-Journal-Cross-Border-Studies.pdf

- Murray, C. R. G., & Rice, C. A. G. (2021). Beyond trade: Implementing the Ireland/Northern Ireland protocol's human rights and equalities provisions. Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly, 72(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.53386/nilq.v72i1.886

- Ní Éigeartaigh, A. (2011). Northern Ireland: Space and identity performance. In W. Berg (Ed.), Transcultural areas (pp. 41–57). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- O’Keefe, T. (2021). Bridge-builder feminism: The feminist movement and conflict in Northern Ireland. Irish Political Studies, 36(1), 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2021.1877898

- Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography. Sage.

- Pink, S., Hubbard, P., O’Neill, M., & Radley, A. (2010). Walking across disciplines: From ethnography to arts practice. Visual Studies, 25(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725861003606670

- Rice, C. (2020, March). Governance in Northern Ireland: Learning from the ‘cash for ash’ scandal. Political Studies Association Blog. https://www.psa.ac.uk/psa/news/governance-northern-ireland-learning-cash-ash-scandal

- Rice, C. (2021). Explainer: Article 16 of the Northern Ireland protocol. UK in a Changing Europe. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/explainers/article-16-of-the-northern-ireland-protocol/

- Rolston, B. (1987). Politics, painting and popular culture: The political wall murals of Northern Ireland. Media, Culture & Society, 9(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344387009001002

- Rolston, B. (2003). Changing the political landscape: Murals and transition in Northern Ireland. Irish Studies Review, 11(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967088032000057861

- Rolston, B. (2004). The War of the walls: Political murals in northern Ireland. Museum International, 56(3), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1350-0775.2004.00480.x

- Ross, A. S., & Bhatia, A. (2021). ‘Ruled Britannia’: Metaphorical construction of the EU as enemy in UKIP campaign posters. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 26(1), 188–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220935812

- Smith, M. L. R. (2002). Fighting for Ireland?: The military strategy of the Irish Republican movement. Routledge.

- Todd, J. (1987). Two traditions in unionist political culture. Irish Political Studies, 2(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907188708406434

- Tolhurst, A. (2019, September 4). John McDonnell accuses Boris Johnson of ‘demeaning the office of Prime Minister’ over Commons jibes. Politics Home. https://www.politicshome.com/news/article/john-mcdonnell-accuses-boris-johnson-of-demeaning-the-office-of-prime-minister-over-commons-jibes

- Tonge, J. (2020). Beyond unionism versus nationalism: The rise of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland. Political Quarterly, 91(2), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12857

- Tonge, J., & Evans, J. (2020). Northern Ireland: From the centre to the margins? Parliamentary Affairs, 73(Supplement_1), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsaa036

- Vannais, J. (2001). Postcards from the edge: Reading political murals in the North of Ireland. Irish Political Studies, 16(1), 133–160.

- Williams, M. C. (2003). Words, images, enemies: Securitization and international politics. International Studies Quarterly, 47(4), 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0020-8833.2003.00277.x