ABSTRACT

This paper explores how transformations in the domestic geopolitics of burial space has produced new logics in respect of property, security and capacity as forms of volumetric and material governance. Focusing on the everyday practices of municipal burial space during the late 19th century in England, this paper builds on feminist political economy approaches to interrogate the emergence of volumetric securitization through transformations in the material politics of burial across a changing socio-technical environment. The volumetric geopolitics of burial shows how embodied experiences and practices of interment illuminate specific class-based death cultures and economies through intimate and affective ecologies of governance. Drawing on examples of two cemeteries located on the Wirral Peninsula during the implementation of the Burial Laws and Amendments Acts (1852–85), this paper looks at how burial volumes are governed, understood, contested and coexist, and the affective and embodied sensibilities that mobilize securitizing behaviours across cemetery space.

1. INTRODUCTION: EVERYDAY EXPERIENCES OF VOLUME

The practice of burial in England during the 19th century shifted dramatically following the decline and eventual abolition of the church rate, a compulsory tax that provided for the parish church under the authority of the Church of England. The imposition of the Burial Laws and Amendments Act in 1852 in England – primarily introduced due to rapid population growth – gave powers to local authorities in England to provide for the provision of burial for all denominations. In addition, all decisions relating to matters of burial were to be decided by the local burial board, a council-appointed committee, with final approval being granted when necessary by the parish bishop. This local, municipal led approach to governance and the increasing privatization of newly established cemeteries that followed during this time transformed the political economy of death and burial towards commercialization, whilst at the same time changes in the governance of burial practices – such as the very placement and depth of bodies – created new attitudes towards the material politics of burial through political and earthly discourses (Gao et al., Citation2021) rooted in the very materiality of depth, volume and capacity.

In this paper I examine the transforming nature of cemeteries as volumetric entities with a focus on how the ‘metrics’ of volume become mobilized (Elden, Citation2013). Demonstrating how networks of power become transformative towards establishing new ways of being and understanding (Sharp, Citation2020), I specifically offer understandings of death and burial as a practice transformed by a specific volumetric geopolitics that has come to shape embodied and domestic experiences of being with, and encountering the political materiality of historic cemetery space. Taking into account history and (feminist) geopolitics is vital in this effort. Freeman (Citation2020) argues that everyday geopolitics has not dealt explicitly with the historical, and rather than understanding simply the legacies of historical geopolitics, it is necessary to explore ‘geopolitical subjectivities at the time of those events’ (p. 441, original emphasis). This makes it possible to account for the very (re)productions everyday actors are responsible for, given how historical practices are important in understanding and making sense of contemporary forms of governance. Feminist historical geographies and geopolitics scholarship is continually widening debates for political geographers both theoretically and conceptually, with work in this vein exploring for example non-human and undersea territories during the Cold War (Squire, Citation2021) and the vertical geopolitics of the Royal Air Force training programmes (Veal, Citation2021). Geographers working at the intersection of historical and political geography are continually exploring the exertion of geopolitical influence, and the more-than-human and material making of worlds. This paper is informed by, and builds on this scholarship by accounting for the material transformations within changing frameworks of everyday burial governance in the mid-19th century. I deploy a historical, feminist geopolitical approach and use concepts of materiality and volume to interrogate the everyday geopolitics of death and burial in newly emerging cemetery spaces on the Wirral Peninsula.

Burial volumes, I argue, are ecologies of material, political, social and affective relations exerted across height and depth. Cemeteries are transformed through a political economy and political ecology of ‘being in common’ (Hausermann, Citation2019, p. 1313) that encompass domains of religion as a performative set of affective, more-than-human relations with the materiality of the earth. The introduction of a newly established, municipal and private landscape for burial in the mid-19th century in England encapsulated very clear socio-affective forces (Gao et al., Citation2021). Because burial reform during this period was not homogenous and many authorities resisted the secular reforms being pushed by non-conforming ratepayers who campaigned against paying the church rate, practices between body and earth – creating new discourses around ideas of property and security – meant that the cemeteries fundamentally shifted from landscapes of death and burial to volumes of death and burial: drawn, delineated and mobilized as a way of separating public and private, secular and non-secular, and the class distinctions thereof. The entangled material politics between the living, the earth, and the dead body shows, as Gao et al. (Citation2021) advance, that political ecology interacts with death in ways that shape negotiations and practices at the gravesite, highlighting how the material politics of death is intertwined with socio-affective forces and tensions. As Hausermann (Citation2019) further puts it, capitalist exchanges are tied to broader political economies and cultural practices (religious ontologies) that make us rethink everyday social and economic relations. In this paper I draw on this thinking to show how the political economy, and material politics of burial volumes, emerged through a domestic geopolitics of actors, practices and securitizing behaviours to interrogate and rethink embodied relations in the cemetery as governance adapts towards municipal and private frameworks.

2. THE DOMESTIC GEOPOLITICS OF CEMETERY SPACE

In this investigation I use two collections of English archival records concerning Flaybrick Cemetery and Wallasey Cemetery which opened in 1864 and 1886, respectively, to explore constructions of volumetric geopolitics, and also to question how the geopolitics of burial has shaped provisions as well as tensions between secular and non-secular bodies through changing practices of material, legal and economic governance. These records I engage with including minutes, letters and newspaper articles speak to the everyday nature of death and burial and cemetery management. This is a pertinent issue given death started to become more increasingly part of everyday life in 19th-century England with the cemetery itself starting to become commonplace in the municipal landscape, and death was becoming ever more part of domestic life.Footnote1 The transformations in conceptualizations of volume, capacity, security and depth highlight a need to think about how power moves through volumes as they become, and how this establishes frameworks of burial governance which rethink the material and embodied politics of this practice.

Drawing inspiration from feminist geopolitical scholarship that concerns everyday practices and the ways geopolitical power is inscribed onto bodies, I approached the cemetery through a domestic lens of geopolitics. This presents a careful attention to the practiced network of operations that foreground ways of being and understanding that are ‘not out there’ (Carter & Woodyer, Citation2020, p. 1050) but that looks towards everyday spaces and practices to think about entangled hierarchies of power. As it has been argued, greater recognition of ‘the interactive and entangled nature of domestic life and geopolitics, collapsing together the dualism often set up between small ‘p’ non-state politics and big ‘P’ politics’ (Brickell, Citation2012, p. 576) recentres the emotional and intime nature of territory and volume, and engages the fact that these practices are not simply confined to large nation-state practices or military endeavours (Jackman et al., Citation2020). This understanding highlights how certain practices, including burial, as an everyday practice of disposal, manifest into complex and messy practices, transforming spaces of burial into territorial volumes that become impressed with logics of security and ownership. Domestic geopolitics builds on unearthing relations of power with a focus on ‘who exerts power as opposed to those upon whom power is exerted’ (Freeman, Citation2020, p. 441).

The cemetery in the 19th century became a territorial arena negotiated and often resisted by everyday ratepayers of the municipal district towards material affordances given to the dead. Governance of burial I propose is therefore a way to think about embodied and organizational control that ‘embeds the consequences and impacts of geopolitical processes’ (Sharp, Citation2020, p. 3) by questioning what the politics of burial actually does as an emotional, intimate and material practice, and the consequences of organized political action between different groups and individuals over the rights to space. To this end, I ask how the affective consequences of the changing municipal landscape and the commercializing of depth centres governance towards the material, intimate and affective. Whilst on the one hand provisions and affordances speak to religious practices, on the other they also speak to more class-based death cultures in which volume and ownership of depth is tied to notions of status, class and capital. These different geometries seek to highlight how the politics of burial cuts into different facets of personal identity and practice.

3. DEATH AND DEPTH: CONCEPTUALIZING BURIAL VOLUMES

Volumetric geopolitics underscores how power is exerted through height, depth and mobilized across both the surface, subsurface (Elden, Citation2013; Squire & Dodds, Citation2019). The transformations and operations of established municipal cemeteries engaged local actors who mobilized and embodied new modes of calculation exploitation, control, enclosure and exclusion (Squire & Dodds, Citation2019, p. 4). Entanglements between the living and the dead were producing three-dimensional, embodied terrains where ‘securing the volume’ (Elden, Citation2013) was an essential aspect of control in the political economy of death and burial. Everyday experiences with volume produced ways of being and knowing with the material world, and constituted and exercised everyday forms of power. The contested politics between surface and subsurface as I go on to argue highlights, as Woods (Citation2020) argues, that there are ‘new interpretations be forged in response to the socio-spatial demands of the environment in which religious groups operate’ (Citation2020, p. 109) that disrupt what traditional sacred spaces should look like. Indeed, the very abolition of the church rate and embracing of commercialization of land on the one hand shows ‘there is an ongoing need to explicate the expansion, splintering and dilution of “sacredness” in response to the broader contexts within which these spaces are embedded’ (p. 110) and on the other how material politics become weaponized to transform the governance of socio-technical environments. How religion, class, capital and land intersect through the transformations of the political economy of death give rise to what Woods terms ‘alternatively sacred’ spaces, that which are designed to ‘augment the appeal of religious groups in non-religious ways; a strategy by which religious groups become more appealing, and therefore more competitive players within a religious marketplace’ (p. 110). This strategy is one directly engaged by local, hierarchical actors of both the municipality and the church in the case of the cemetery. The extent to which these actors adopt market logics is a way to not just commercialize volume and monetize depth, but also create class-based distinctions through mobilizations of security and capacity.

Volumetric thinking has become a lens to explore how ‘ideas, practices, and institutions lay out, embody, and regulate transcendental attempts to create meaning’ (Pickering, Citation2016, p. 119), and establishing and maintaining forms of political control (Puntigliano, Citation2019; Woods, Citation2020). Arguably, we need to pay closer attention in the political economy to the ecology of death and the ‘fluidity of the boundaries between sacred and secular, or rather, on the complex coexistence and intersections between the two’ (della Dora, Citation2018, p. 45). This is to account for the changing practices of multiple competing co-habitations and coexistences between secular and non-secular bodies to understand how burial volumes are embodied and situated as three-dimensional, multilayered terrains regulated by different ‘power geometries’ (della Dora, Citation2018, p. 46). New understandings of security (Elden, Citation2013a, Citation2018) by human and more-than-human forces show that individual needs and affordances matter when they are challenged, rewritten, or refused whereby the very conditions of space can be made and unmade, and burial volumes are consumed as affective material entities and habitations (Gao et al., Citation2021). For example, practices of consecration, meaning the act of declaring something sacred and separate from secular use – in direct contrast to desecration – meaning a breach of rules towards sacred spaces and objects that deprive them of their sacred character (Caseau, Citation1999), sits in direct conflict with co-presence of unconsecrated land in newly established municipal cemeteries. These distinctions do not just become solely religious guidelines and dynamics but ones of resource competition in which property, law, and money become discursive tools for dominant religious groups to maintain control. Property and land ‘provides both a rationale for dispossession and a ground for its opposition. Its ends are varied and diverse, including personal survival, human flourishing, economic efficiency, privacy and propriety’ (Blomley, Citation2017, p. 594). Further, because local actors are not simply competing for (and also purchasing) space, but rather for depth, the spatial transformation from area to volume is worthy of greater exploration, as well as the ‘fullness’ of space in relation to the politics of capacity (Peters & Turner, Citation2018) and the pressures this puts on the political economy of death and burial.

The more entangled dimensions in which power becomes operationalized (Elden, Citation2013b; Squire, Citation2020; Jackman & Brickell, Citation2021) therefore helps us to think about geopolitics through the intimate lens of the body once it ceases to be living and what burial practices signify through means of volumetric territoriality. The volumetric signals to an ‘animated and inhabited’ way of understanding geopolitics (Dixon & Marston, Citation2011, p. 445) through a more dimensional lens. Volumes are about encounters and limits between human and material subjects; the seen and unseen ways power is mobilized. Yet the complexities of volume and the exercise of power through volumes require further scrutiny in terms of how volumes are put to work (Jackman & Squire, Citation2021) and the everyday spatialities of territorial volumes (Elden, Citation2013b; Goldstein, Citation2020; Sammler, Citation2019; Wang, Citation2021).

Recent engagements have brought this focus towards the embodied and everyday, investigating how territorial volumes capture the production of territory through immersive, experiential, and affective conditions. Such work has sought to think about more diverse engagements, representations, and entanglements with volume (Pérez & Zurita, Citation2020). Much of this scholarship has sought to challenge popular, nationalist representations and consider the variety of ways volumetric spaces have distinct cultural and social meanings. Pérez and Zurita (Citation2020), for example, highlight alternative world-making practices through mystical and spiritual understandings and knowledges of karst environments beyond exploration. Volume, as an analytical tool, opens awareness to different knowledge practices, new ways understanding inhabitations with the earth, and ‘attention to the power relations between competition and overlapping knowledges’ (Halvorsen, Citation2019, p. 800) that define the depths of power.

The cemetery itself is a space that is often reflected upon as a cultural landscape of mourning, loss, and absence where affective capacities of remembrance and identity intersect to create spaces of memory and attachment (Maddrell, Citation2013). However, associations between the living and the dead, conceptualized as an absent–present relationship (Meyer, Citation2012; Maddrell, Citation2013), are not so straightforward. As Maddrell and Sidaway advance, deathscapes underscore how death is intensified in certain spaces, but they are also a ‘reflection of changing conditions for the living’ (Maddrell & Sidaway, Citation2010, p. 14). Deathscapes are spaces of power and geopolitics that create and maintain (infra)structures of inclusion and exclusion (Maddrell et al., Citation2021), for example, by denying minority individuals the rights of burial. As a space of territorial power, the inscription of geopolitics across denominational practices underscores the more contentious politics of death and burial within the cemetery, and how certain rules and forms of power may be upheld or resisted. The changes between socio-technical and ontological, as Maddrell et al. have shown, shows that a lack of care, provision and infrastructure can create embodied feelings of harm. Maddrell et al. further show that geopolitics can intersect in harmful ways, such as through the denying the dead their rights that can lead to embodied repercussions across cemetery space through exclusion. Approaching the cemetery and its geopolitics through ‘plural, multiple, and diverse ways’ (Squire, Citation2021, p. 208) open up the expansiveness of the world-making capacities that are rooted in different ways of being and understanding. Ontologies of death and burial are not universal but are specialized in accordance with particular beliefs and practices. The embodied and entangled nature that is had with volume requires us to pay attention to the things that ‘fill’ volumes, and their meanings and associations (Squire, Citation2020; Wang & Chien, Citation2020) rather than just a sole focus on ‘securing’ or governing volumes. In thinking about such emergent properties through modes of dimension, expressions of geopower (Grosz et al., Citation2017) this highlights the non- and more-than-human capacities of geopolitics more closely. Scholarship on subterranean worlds and their capacities – as opposed to just their properties – unlocks the dynamic multiplicity of volumetric spaces. The volumetric is not simply a containerized volume to be filled. As Wang (Citation2021, p. 4) argues, An emphasis on ‘volume’ overlooks the intricate relationships between disparate subsurface materials, such as water, sands and strata, all of which become mediated by scientific and political discourses and practices. However, a stress on the emerging properties and discourse and power leaves no room for the agency of material and downplays the autonomy of the external world.

The lively practice of volumetric territory across the cemetery is articulated through ‘tendencies of deterritorialisation and reterritorialization’ (Peters et al., Citation2018, p. 1) including how we understand the material politics and political ecology of burial as regulatory knowledge frameworks. Though lively and lived engagements with volumes are somewhat well studied, similar engagements with the dead body are less so, as well as the cemetery itself as subsurface and subterranean political environment. Yet, to fully understand the way everyday volumes of death become drawn, sensed, and placed (Hawkins, Citation2020) we need a more expansive understanding of dimension across engineered subsurface environments to unearth how volumes of death and burial are experienced and practiced, and how domestic geopolitics embodies itself with the changing socio-technical and material politics of death and burial.

In this paper I next unpack the practice of 19th-century burial in England and the changing political landscape of death towards then exploring commercial practices of volumetric governance and the political economy of burial volumes. I the reflect on the need to think about ‘more concerted engagement within geography voluminous constructs’ (Squire, Citation2021, p. 208) by thinking about the more affective and embodied volumes of burial that draw dead bodies into new volumetrically laden power logics, and the way more mundane materialities become governable by and for local actors.

4. THE CHANGING PRACTICE OF 19TH-CENTURY BURIAL

The two cemeteries that are the focus of this paper were established during a period of major burial reform. The introduction of a series of burial laws and amendments acts from 1852 to 1885 in England, which handed power at a municipal level to local burial boards were responsible for cohabitating multiple denominations in the one cemetery. This was established in what was a phased-out break with the traditional churchyard burial. It became enacted as a direct response to increased population growth, and changing attitudes in the entangled material relations the living were having with the dead (Rugg, Citation2013). This became a messy co-constituted geopolitical relationship of embodied-affective relations and material politics – the body and the earth. Alongside, the development of the shipbuilding industry during the mid-19th century in the Wirral region, and the building of new docks in Birkenhead and Wallasey had a large transformational effect on the region. With developments in steam and rail, and the building of other new industries, the region expanded and forged closer connections with the city of Liverpool, a major port city. Birkenhead, with a population of only 110 people in 1801, grew to 51,649 by 1861, and between 1880 and 1910 the population of Wallasey grew from just over 20,000 to 75,000 (Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2021).

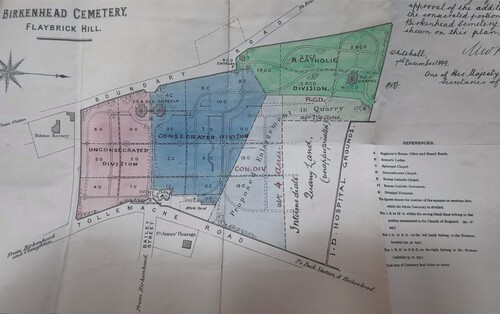

With growing levels of migration into the region, the demand for new burial provision was clear. The site for Flaybrick Cemetery, Bidston Hill, was selected and divided up between 6 acres provided for Roman Catholic burials, 9 acres for Church of England and 6 for Nonconformist burials. Wallasey cemetery, completed in 1883 with 23 acres of land, was similarly divided. Flaybrick Cemetery, completed in 1864, was designed by architect Edward Kemp whose plans came to reflect that cemeteries were not simply garden landscapes for the Victorian upper classes; their purposes demanded greater considerations of form and functionality towards denominational cohabitation. The monopoly of which the Church of England had over the practice of burial was reflected in the Burial Act of 1857Footnote2 (and it was not until The Burial Laws Amendment Act 1880 that this monopoly was ended). The municipal cemetery also had to accommodate non-conformist individuals who adhered to different practices to that of the established church.Footnote3 The overall authority was with the Bishop of Chester who oversaw the local parishes of Birkenhead and Wallasey, and who had final decisions in respect of consecration, building works, and resolving disputes that were beyond the influence of the burial board. The local parish authority was under management by a registrar responsible for recording name, age, date and cost of burial. The map of Flaybrick Cemetery () shows the denominational divide of the land.

Figure 1. Plan of Birkenhead Cemetery, Flaybrick Hill (1864).

Source: Wirral Archives, W/B/160/3; detail. Image reproduced with permission.

The role of class started to become important giving the large volume of pauper burials, and many upper-class Victorians demanded adequate space and room to bury their dead away from the crowds of public burials (Herman, Citation2010). The legislation associated with England’s sanitary reform that exacerbated class-based distinctions insisted, for example, that cemeteries had to be built at least 200 yards away from dwelling houses, and on land that could be suitably drained without interfering with local water supplies, as well as following other technical measures in respect of health and the environment.Footnote4 The relationship between health and class became one of a number of factors that shaped cemetery access and provision and came to influence the political economy of death and burial.

My investigation into the politics of burial during this period involved exploring the cemetery’s archival records spanning from the early 1860s, which are held by the Wirral Archive Services and are chronologically ordered and also categorized by subject issue, so that particular incidents and accounts, despite being partial, could be more easily followed. Through also tracing the legislation between this period, my investigation looked towards tensions between the law as written and the law as understood and applied, and the way burial law was negotiated, followed or ignored by domestic actors involved in directly mobilizing this geopolitical arena. The Burial Acts marked a significant juncture in the debate between religious freedom and the ‘oppressive influence’ of the Church (Rugg, Citation2000, p. 33), which meant their application in practice was not so straightforward. The sensitives sought to favour both the non-secular and first-class ratepayers. As Rugg (Citation2000:, p. 34) points out, ‘the funeral is simultaneously an intensely private and entirely public affair … conducted in public space where allowable activities are decided by a higher authority’. Secular individuals consequently were often placed in a vulnerable position if their faith was questionable, and they were often considered by the church to be socially undesirable. Given how quickly denominational identity took hold in the 19th century in England, the nexus between religion and politics had firmly grounded itself in ‘new contextual and constitutive conditions’ (Rugg, Citation2000, p. 44) allowing multiple facets of religion to develop, largely with respect to modes of identity and practice that came to largely define everyday political and cultural life in the 19th century. It was a fact that the growing popularity of social non-conformity represented a threat to non-secular life in England, as many secularists were keen to separate the influence of the church over the provision of burial. This came to show how matters relating to practices of death and burial seeped into everyday life, and how embodied relations became so contentious through death’s new political economy.

5. SPATIAL ALLOCATIONS AND AFFORDANCES OF VOLUME

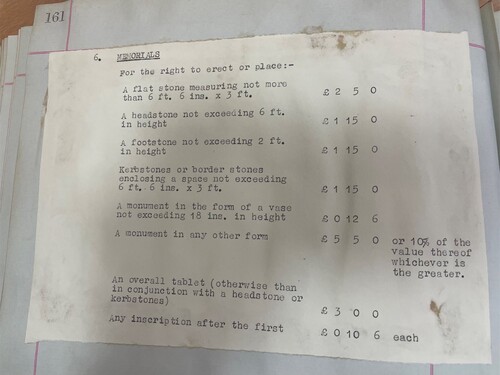

Governing dead bodies, and the entanglements between bodies and earthly volumes – reflecting the shift towards a more commercial and competition-based practice between the secular and non-secular – becomes a way to probe how complex coexistences are (re)made through modes of governance, and the more hidden and alternative spatialities within religious landscapes (della Dora, Citation2018; Woods, Citation2020). Class based distinctions were firstly recognized within the Exclusive Rights of Burial () which was costed by the burial board, and as was the case, burial plots and their volumetric affordances were drawn and plotted through the terrain of property. Individual plots sizes decided by the burial board were firstly calculated and mapped to be sold as individual spaces, rather became part of a larger network of access. When one parishioner of Flaybrick Cemetery had found to been given the ‘incorrect’ grave space for his family member because it was not located on consecrated ground, for example, he complained to Flaybrick Burial Board and demanded the headstones be moved to the correct plot of land he had paid for. Flaybrick Burial Board in some cases would also refuse to allow non-parochial clergy to conduct burial services if it meant money was being taken out of the parish boundary. Despite having no legal premise to do so, they informed incumbents outside of the parish they would not be able to claim any fee for conducting a funeral within the parish.

There has been a controversy arising out of a Roman Catholic claim to exclusive control over the portion of the public cemetery allotted for that denomination. From time to time cases arise in which people dying in the protestant faith desire to be buried in a family grave in that portion of the cemetery which has been allotted for Roman Catholics. The Roman Catholic priests claim that when such burials take place, the religious service at the graveside must be conducted by one of themselves and not by any protestant minister or clergyman. The law however is very vague, there is nothing to indicate to whom such allotments can be made.Footnote5

Figure 2. Exclusive Rights of Burial (1864).

Source: Wirral Archives, B/160/3/09. Image reproduced with permission.

These capitalist practices affirm the more contentious economic practices that perpetuated logics of property by hierarchical and three-dimensional claims to ownership. This often went beyond the rate of payment for individuals plots and denominational groups, who attempted to take collective ownership by marking a political distinction between consecrated and unconsecrated ground through the materiality of the earth. Ratepayers also took collective responsibility for upholding legal standings of spatial allocation. Bodies of the poor were not only often only designated certain days and times for ‘public’ burials, which often entangled the poor in multiple material agencies by determining the rules and conditions of their right of accessing a funeral, but their flow of volume into the cemetery was also closely followed. Capacity and volume are mobilized as tools of order and organization, and this often influenced the treatment of different individuals by local actors. Because bodies make volume, as well as fill volume, the density of the dead foregrounds ‘an understanding of how value envelopes volume’ (McNeil, 2019, p. 816) and the way the materiality of the earth is governed. Affective relations come to serve as conditions of power (Gao et al., Citation2021) by local ratepayers demanding particular conditions of the organization of bodies and space. These interpersonal power relations (Wilkins, Citation2020) demand closer attention in terms of how the volume and commodity of land is mobilized by local actors.

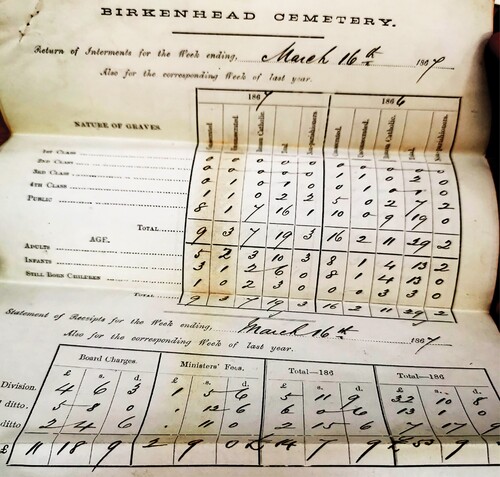

The depth of power, as Elden (Citation2013) shows, indicates a political geometry of governance and the multiple ways the dead are managed. Indeed, the capacious affordances that are given to the dead body through the designation of maximum of minimum capacities was one of the most consequential material politics of interment. The recording of bodies into the cemetery ( shows a weekly recording by denomination) mobilized capacity as tool of maximizing the political economy of the land which often resulted in very specific cases of bodily exclusion and perpetuated embodied understandings of death and class. Many private graves were often sought after owing to the growing volumes of non-conformist, public grave spaces that were often described as overcrowding the cemetery. When applications were often made to request permission to move bodies, it was because of shrinking burial provisions and diminished capacity for public graves. Embodied ways of governing the dead therefore become rooted in different ways of being (Jackman et al., Citation2020) by defining the materiality of volume. Because earthing and unearthing are emotional practices, the very political materiality of volume expresses the boundary between public and private, secular and non-secular, in multiple ways: to be ‘fixed’ in place, or to be expanded, as capacity changes with a greater increase of bodies being admitted into the earth. Extra charges and ‘special fees’ for private interments,Footnote7 allocated further new degrees of exclusivity, and mobilizations of class that socially legitimized the way religion developed as both a social and spatial practice only more increasingly became linked to wider projects of everyday governance.

Figure 3. Interment figures for Flaybrick Cemetery.

Source: Wirral Archives, B/160/3/09. Image reproduced with permission.

Across the cemetery the politics of capacity highlights how the movement of bodies both into and across space, particularly in cases of readmitting bodies into different volumes, creates affective conditions of in/exclusion by changing the provisions afforded to different denominations and identities at the gravesite. The changing practices of marking the distinction for a class-based system of burial further involved placing the poor, the unidentifiable who had returned from sea, and also children in mass and unmarked gravesites, drawing a distinction between bodies that matter and those that seemingly do not. This was reflected in the discourses of overcrowding and the poor sanitary conditions of the poor who were often remarked as being a public nuisance when their dead were left out in the open for the municipality to deal with and bury (Herman, Citation2010). In many commercial cemeteries dozens of bodies would be stacked vertically at the periphery of the cemetery inches from the ground's surface, and left unmarked. These more hidden volumes speak again to the politics of capacity and disposal practices in a changing socio-technical environment that values the volume of space over the volume of bodies.

The ‘understudied’ territorial dimensions of property (Blomley, Citation2017, p. 593) allow us to think about property and ownership beyond the confines of the state, and the ‘organised set of relations,’ in this case which are eminently volumetric, between identities and affordances of height and depth. This begins to draw awareness to not just what volume is but rather what it does as a space of embodiment and as a tool of governing and separating bodies. The cultural meaning of volume in respect of the dead captures ways to think about the sensitivities of everyday forms of governance, and their emotional and intimate geopolitics (Maddrell et al., Citation2021). For example, many cases of disinterment and the (re)moving bodies once admitted to the earth is still seen as a wilful act of desecration. These more affective practices challenge ontological notions of security in the assumption that the dead body is ‘fixed’ to the ground, as well as rethinking the way death is ‘inhabited’ in the cemetery (Gao et al., Citation2020, p. 16) through entangled embodied practices between the living and the dead.

6. BODILY SEPARATION AND SECURITY

Pluriversal engagements with volumetric space are seeking to account for different ways of being and the world-making practices across different ontological understandings of the Earth (Theriault, Citation2017; Squire, Citation2021). This is alongside the very alternative understandings and inscriptions that are writing these practices as geopolitical phenomena. To those who had a greater adherence to religion, and with scope for influencing the law, different denominational practices came have a shaper influence over relations of power. The materiality of volume and its securitization, or indeed vulnerability, demands greater attention in terms of its political agency given how alternatively sacred practices (Woods, Citation2020) define class-based distinctions between the religious and the secular through the material politics of burial. The way relations of power in this sense operated included allowing non-conforming ratepayers to be subjugated through embodied and affective logics of security – logics intended to keep them out of consecrated volumes, and keep those volumes between consecrated and unconsecrated separately defined. The way that securitizing logics are mobilized in multiple ways shows that ‘the sacred is not necessarily something distinct, experienced in isolation of everyday life; rather, it is often experienced in intimate conversation with it’ (p. 115). Many non-conformists raised numerous objections to being inadequately provided for, and argued that the division between religious adherence and non-conformity did not warrant them to be marked on unconsecrated ground.Footnote8 Actions to consecrate, or to desecrate, have become defining tools of power for organizing embodied relations and modes of separation between bodies and earth.

The habits and performances of defining distinctions between the sacred and secular across the cemetery mark out how through embodied geopolitics ‘religious value can be manipulated’ (Woods, Citation2020, p. 120). Adherence to forms of embodied politics and ontological subjectivities were seen as important practices that strengthened the political economy of the church as discursive ways of maintaining a resistance of secularization. For example, The Rites of the Catholic Church are read as a means to ‘secure the volume’:

We are now petitioned to consecrate the same as, and for a place of burial, according to the rights and usages, where the bodies of the dead may be laid to unite until the general resurrection, we therefore favorably inclining to this pious request and by our ordinary and first most humbly the only high God of heaven and earth, father, son and holy spirit for this divine assistance and blessing upon our present purpose do forever separate the said piece of land, now added to the consecrated portion of the said cemetery, and particularly described in the plan annexed and signed by us from all common and profane uses, and we do consecrate, the same for the Christian burial of the dead accordingly, from this time forth Holy ground.Footnote9

There is a difference between the spirit of man that goes upward, and the spirit of the beast that goes downward to the earth. … Thy holy servants hast taught to assign particular places where the bodies of thy saints may rest in peace, and be preserved from all indigeneities whilst their souls are safely kept in the hands thy faithful Redeemer.Footnote10

Discursive practices (Medby, Citation2019, Citation2020) stress how imaginations of volume are equally as important as their physical constructions. As for our relationship with the earth, the notion of the sphere by philosopher Sloterdijk (Citation2014, p. 166) characterizes a relationship with ‘large interiors of spiritualized vitality … an expanding lifeworld through spatial figments’. This reflects a commitment to volumetric security through the more individual and personal ways we govern our dead which shows how domestic geopolitical influence is often asserted in everyday spaces, and how local actors secure the volume (Elden, Citation2013). As was often the case, it is the Bishop who will consecrate the ground, and materially define the distinctions of consecrated and unconsecrated ground through the placement of stones. In many cases of dispute the Bishop has the right to refuse consecration of a body or portion of burial ground if not properly separated. Non-conformist bodies and Roman Catholic bodies have always been strictly separated, and further, the Roman Catholic body could only be consecrated outside the church before its admittance to unconsecrated ground. These practices were essential the political economy of the church and for local actors to not only embody but to mobilize these securitizing practices. For example, in cases of family members of Flaybrick seeking to burial multiple denominations together on that portion of land, ratepayers objected strongly in letters expressing concern that non-conformists would desecrate the land. The board responded in a memorandum to ratepayers:

the late catholic bishop received the assurance that this [Roman Catholic portion] would be devoted exclusively to the burial of Catholics – it could not according to law consecrate it except on that condition. If that condition is set aside its present character ceases ‘ipso facto’ and it is no longer what it has hitherto been the portion of the cemetery consecrated for catholic burials – of which I must in such case give due notice to the catholic clergy and people. If the original condition is maintained, and a notice published that graves are bought subject to it, all hardship or difficulty would thereby be removed. In some exceptional cases not otherwise provided for, a catholic has been buried with a protestant relative in another portion of the cemetery, (where this was wished) – the catholic rite being followed (if permitted), at the grave, or in certain cases where this was not allowed, the priest has lead the burial service at the house before the body was removed.Footnote11

The domestic geopolitics of everyday actors is particularly shown at the very construction of the gravesite that communicates how practices of embodied governance effect that ways in which volume and security are used as geometries of power beyond the scale of the state, and local actors are just as implicit in maintaining and defending territorial volumes. For example, when the Church of England started to lose its monopoly across England (which allowed non-officiated incumbents to officiate burials) it became clear as some ratepayers of Wallasey cemetery described the changing practices as ‘actions that will take funerals out of Parish altogether’.Footnote12 Consecration is therefore an ungrounded politics of the earth, not just dictating the placement and admittance of particular bodies, but changing affective relations and economies.

7. GOVERNING BURIAL VOLUMES

One of the tools of governance that worked towards increased capital and commodification was the reclamation of volume by both the municipality and everyday actors. In some cases this involved refusal to consecrate the earth unless spatial provisions were properly accommodated for. For example, ratepayers of Wallasey Cemetery disputed the provision of only one mortuary chapel to be shared by multiple denominations. This particular case marked a three-year dispute that eventually was reported in national newspapers. It was written that:

[in] this scheme no separate chapel is apportioned to non-conformists but they are to be permitted the use of the chapel to be consecrated by the Bishop of Chester. We have some doubt as to the strict legality of this course, since Nonconformist services in a consecrated church will be, to say the least, a decided novelty.Footnote13

Local ratepayers in the Merseyside region during the rollout of the Burial Laws sought legal advice over this matter, arguing that:

it should not be intended to consecrate the chapel which would, in consequence, be available to all denominations of protestant alike, the cemetery in a short time, will be divided into consecrated and unconsecrated portions [and] another chapel will have to be built on the unconsecrated portion.Footnote14

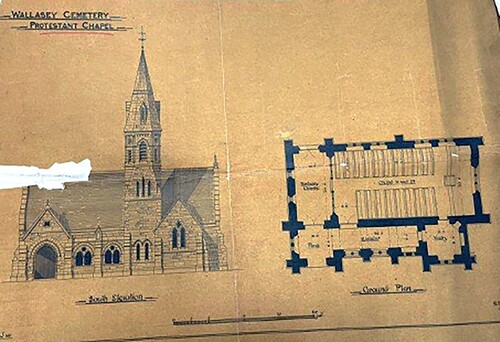

Further bodily distinctions through the material politics of the cemetery (Miller et al., Citation2005) and the demand their separate interiors and dimensions matter not just in terms of how dead are practiced and ritualized in mortuary spaces but through resisting further transformations in the socio-technical environment. In and , for example, intimate spaces of the chapel – including the vestry and mortuary – have very specific and individual uses and practices for different religions as spaces that mark the finality of the absent–present relationship before the body is admitted to the earth. This maintains borders inside the cemetery, and not just outside, and are important functions of ontological security. These practices also uphold the distinct relationship in the cemetery between public and private, and to also ensure that the Church does not become financially displaced.

Figure 4. Scaled view (south elevation) and ground plan of Wallasey Cemetery Protestant Chapel.

Source: Wirral Archives W/40/12. Image reproduced with permission.

Figure 5. The former Birkenhead Priory and the Churchyard during partial demolition.

Source: The Sphere, January 1957.

Threats made by ratepayers were pursued as a means of ‘securing the volume’, because without consecrating the ground denominational bodies would sometimes refuse to bury their dead (which would deprive the cemetery of an income) where effectively those volumes are open to desecration. The material politics of burial shows that in many cases what comes to fill particular volumes matters as a form of governance and a form of control. Many recent examples of mass gravesites and their unearthing, or indeed also urban development over gravesites and former cemeteries show how power and erasure become compounded through a politics of depth. Distinctions matter not just in life but also in death.

Beyond the Burial Acts, urban development in the region towards the twentieth century forced re-interments into new cemeteries due to diminishing capacities before new burial grounds could be built in time on the region. The former churchyard of St Mary’s, Birkenhead was demolished to become a dry-dock, and the bodies of 5550 were readmitted to Landican cemetery, which had opened in 1934. The newspaper reported that:

[the] site of the church has been a place of worship for hundreds of years. The area involved is 3,100 square yards, about two-thirds of the churchyard. This land has been acquired from the church authorities for Cammell Laird under a compulsory purchase order of the Birkenhead Corporation, for the construction of a dry-dock which will be able to accommodate some of the biggest oil tankers afloat.Footnote15

This particular example highlighted a clear tension between church-owned land and municipal land. Because the church rate had been abolished, it was proposed by the vicar to convert the churchyard ‘into a small public space with no disturbance to any the graves’.Footnote16 New transformations of burial space and the mobility of dead bodies in and across volumes had various emotional consequences as bodies of the dead are moved out of one domain to another. However, the managed decline or even destruction of many burial spaces only further emphasizes the capitalist endeavours of the church and local parishes. The role and place of religion changes in the changing urban environment (Woods, Citation2020) altering the terms of what are acceptable practices and what are not when it comes to matters concerning the dead.

8. CONCLUSIONS: RESCALING SECURITY AND ADAPTIVE GOVERNANCE

Across the volumetric spatialities of burial, governance is becoming ever more concerned with creating volume whilst efforts to ‘secure the volume’ still matter in a changing socio-technical landscape. During the late twentieth century many municipal cemeteries stopped admitting bodies simply because they had run out of space. Only some years earlier, some of these cemeteries had already undergone extensions owing to exponential increases in population from tens to hundreds of thousands. Many also simply fell out of use. But, their lasting frameworks are still very much relevant through the practice and the political economy of burial, which matter as governments seek answers for the future accommodating of the dead. Thee calculated, organized and exercised modes of controlling and contesting space, where bodies are placed, governed and mapped, not just upon the geophysical, but on the embodied and affective relations and entanglements between the living, the dead and earth. Burial politics is both fixed and fluid; volumes are created, filled, secured, expanded and reclaimed, marking multiple transformations in the political economy of burial.

The Burial Laws and Amendments Acts in England (re)made and (re)structured where and how burial was done, in such a way the place of the cemetery, a terrain of affective relations and attachments, became more than a space of disposal, but an embodied and everyday space of volumetric governance. As I have shown, the volumetric is mobilized by a domestic geopolitics of burial. The territorializing project of burial has become an economic and political exercise of placing the dead, and marking the way the complex coexistence between modes of belief and non-belief takes place through negotiation, vulnerability, class and capital. Burial volumes are both individual and collective, and are a concern for multiple scales of governance, from the individual to the state. Power ‘cuts across height and depth … is conveyed through maximum and minimum capacities, density and mass, and capacity building techniques (Peters & Turner, Citation2018, p. 1037) and is refocused and recommitted towards the material politics of the earth (Gao et al., Citation2021)

Burial volumes also have limits, in the case that there is very little room for the expansion of earthly volumes of cemeteries in metropolitan areas. Questions of volume and capacity often force local burial boards to create ‘exclusive’ boundaries in order to maximize profits, but when thinking about land politics numerically, and the very ‘metrics’ of volume more closely, this gets us to consider how volumes drive and distribute value, and how certain bodies matter in the cemetery over others, individually or collectively. Capacities have operational motives which are often used as projections for actors to make calculative grasps into and onto space, and the material change of the churchyard to the cemetery allowed new capitalist practices to emerge in an era of class-based death cultures (Herman, Citation2010; Rugg, Citation2013), where the sacred and secular interplay marked these distinctions in both obvious and subtle ways.

Multiple ontologies present challenges for ways we think about and do bodily governance and security, as well and the everyday ways that governance is negotiated or resisted. In this paper, I have sought to consider the embodied, intimate, affective, and expansive capacity of death, and have looked towards the cemetery as a way to think about governance through the place of the dead body and the importance of burial. The relationship between death, space and politics gives meaning beyond the material confines of the gravesite, and this paper has broadened the way volume and dimension make and challenge social and political realities. Paying closer attention to the everyday, domestic geopolitics of death and burial unearths the way contestable political arenas take shape, and what impact this has on how different actors attempt to secure the volume (Elden, Citation2013).

The geopolitics of the 19th century transformed the governance of death in multiple ways, and spaces of competition change the way that religion and religious practices are done and understood, creating and upholding in/exclusions. The volumetric affordances of the ‘metric’, (Elden, Citation2013b) (deep) bordering practices, and capacious thinking (Peters & Turner, Citation2018) are ways this paper has engaged with the exercise of power in the cemetery, through think about volume as being drawn, sensed, mapped and expanded. These pluriversal engagements (Theriault, Citation2017; Squire, Citation2020) that I have charted open up the world-making capacities that raises questions surrounding ontology and security through the lens of the body, the body’s engagement with the depth of the earth, and the earth’s political materiality that has to navigate access of different degrees of ownership, private and publicness. This paper has interrogated the role of historical everyday geopolitics to think about and centre transforming networks of power, and everyday embodied experiences. This framework helps to critically think about geopolitical phenomenon outside the traditional narratives of power and knowledge and look more deeply at the very nature of geopolitical practices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Kimberley Peters, Andy Davies and Ella Bytheway-Jackson for their support and guidance throughout the writing process, as well as the two anonymous reviewers for helping to improve the manuscript. Thanks also to the author’s CASE partner, the Wirral Archives and William Meredith, without who this research would not be possible.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 By 1914, there was 3500 cemeteries in the UK. Though numbers are only an estimate, many municipal cemeteries house over 100,000 bodies. Burial reform and the sanitary movement made death a central issue to Victorian life.

2 This act allowed burial service to take place on consecrated ground without Church of England Service.

3 Non-conformism refers to those who were adherents of Christian groups that became separated from, or were established outside, of the Anglican Church (or the so-called ‘established church’) such as Methodists and Quakers. Social non-conformists by extension do not adhere to aspects of practice or belief with the established church. The burial boards referred in correspondence and meetings to non-conformists under one collective (and as to be buried on unconsecrated ground).

4 The ‘Memorandum on the Sanitary Requirements of Cemeteries’ was published by the Ministry of Health. Parliament had committed itself to investigating the ‘evils associated from the interment of bodies’ in 1842.

5 Letters Relating to the Management of the Cemetery; Wirral Archives, B/160/3/14.

6 See note 5.

7 Many upper-class Victorians sought special permissions from the clergy for more private burial spaces as proximity to grave-spaces dwindled. This was detailed in statements from the Burial Board of Flaybrick Cemetery in the records book; Wirral Archives, B/160/3/1.

8 A letter to Flaybrick Burial Board dated 2 March 1864 by the town clerk stated; Wirral Archives, B/160/3/13:

I have been requested by the non-conformist ministers connected with the chaplaincy of the cemetery to state to the cemetery committee their desire for the amendment of the name of their portion of the burying ground, on the books receipts it is styled as ‘unconsecrated’ and they would greatly prefer the designation ‘non-conformist’ they beg respectfully this proposal to the committee, and that there may be no technical or other difficulty in this way. They are greatly aware that the name ‘unconsecrated’ is given elsewhere, that they suggested it is not a correct description of the ground in as much as depositing of the remains of those who shall be buried in un-consecration, is the eyes of those who mourn over them. They are sorry to admit what appears to be such a small matter.

9 Sentences of Consecration; Wirral Archives, B/160/3/27-31.

10 See note 9.

11 Papers Concerning the Concerning Exclusive Catholic Rights of Burial; Wirral Archives, B/160/3/34.

12 Papers Concerning Consecration of Wallasey Cemetery; Wirral Archives, W/420/08.

13 ‘Wallasey Cemetery’, The Liverpool Weekly Courier, 7 June 1884.

14 Papers Concerning Consecration of Wallasey Cemetery; Wirral Archives, W/420/0.

15 ‘A doomed churchyard’, The Sphere, 19 January 1957.

16 See note 15.

REFERENCES

- Blomley, N. (2017). The territorialization of property in land: Space, power and practice. Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(2), 1–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1359107

- Brickell, K. (2012). Geopolitics of home: Geopolitics of home. Geography Compass, 6(10), 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00511.x

- Carter, S., & Woodyer, T. (2020). Introduction: Domesticating geopolitics. Geopolitics, 25(5), 1045–1049. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1762575

- Caseau, B. (1999). Sacred landscapes. In: G. Bowersock, P. Brown, & O. Grabar (Eds.), Late antiquity: A guide to the postclassical world (pp. 21–59). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dixon, D. P., & Marston, S. A. (2011). Introduction: Feminist engagements with geopolitics. Gender, Place & Culture, 18(4), 445–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2011.583401

- Dora, V. d. (2018). Infrasecular geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 42(1), 44–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516666190

- Elden, S. (2013a). The birth of territory. University of Chicago Press.

- Elden, S. (2013b). Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power. Political Geography, 34, 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009

- Elden, S. (2018). Shakespearean territories. University of Chicago Press.

- Freeman, C. (2020). Historical everyday geopolitics on the Chile–Peru border. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 39(4), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.1306

- Gao, Q., Woods, O., & Kong, L. 2021 The political ecology of death: Chinese religion and the affective tensions of secularised burial rituals in Singapore. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 251484862110684, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/25148486211068475

- Goldstein, J. E. (2020). The volumetric political forest: Territory, satellite fire mapping, and Indonesia’s burning peatland. Antipode, 52(4), 1060–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12576

- Gordillo, G. (2018). Terrain as insurgent weapon: An affective geometry of warfare in the mountains of Afghanistan. Political Geography, 64, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.03.001

- Grosz, E., Yusoff, K., & Clark, N. (2017). An interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, inhumanism and the biopolitical. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(2–3), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276417689899

- Halvorsen, S. (2019). Decolonising territory: Dialogues with Latin American knowledges and grassroots strategies. Progress in Human Geography, 43(5), 790–814. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518777623

- Hausermann, H. (2019). Spirit hospitals and ‘concern with herbs’: A political ecology of healing and being-in-common in Ghana. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 4(4), 1313–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619893915

- Hawkins, H. (2020). Underground imaginations, environmental crisis and subterranean cultural geographies. Cultural Geographies, 27(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474019886832

- Herman, A. (2010). Death has a touch of class: Society and space in Brookwood Cemetery, 1853–1903. Journal of Historical Geography, 36(3), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2009.11.001

- Jackman, A., & Brickell, K. (2021). ‘Everyday droning’: Towards a feminist geopolitics of the drone-home. Progress in Human Geography, 46, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211018745

- Jackman, A., & Squire, R. (2021). Forging volumetric methods. Area, 53(3), 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12712

- Jackman, A., Squire, R., Bruun, J., & Thornton, P. (2020). Unearthing feminist territories and terrains. Political Geography, 80, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102180

- Maddrell, A. (2013). Living with the deceased: Absence, presence and absence–presence. Cultural Geographies, 20(4), 501–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474013482806

- Maddrell, A., McNally, D., Beebeejaun, Y., McClymont, K., & Mathijssen, B. (2021). Intersections of (infra)structural violence and cultural inclusion: The geopolitics of minority cemeteries and crematoria provision. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 675–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12437

- Maddrell, A., & Sidaway, J. D. (Eds.). (2010). Deathscapes: Spaces for death, dying, mourning and remembrance. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Medby, I. A. (2019). Language-games, geography, and making sense of the Arctic. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 107, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.10.003

- Medby, I. A. (2020). Political geography and language: A reappraisal for a diverse discipline. Area, 52(1), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12559

- Meyer, M. (2012). Placing and tracing absence: A material culture of the immaterial. Journal of Material Culture, 17(1), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183511433259

- Miller, D., Meskell, L., Rowlands, M., Myers, F. R., & Engelke, M. (2005). Materiality. Duke University Press.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2021, April 1). Populations of Wirral, Birkenhead, West Derby, and Liverpool from 1801 to 2011. https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/transparencyandgovernance/freedomofinformationfoi/populationsofwirralbirkenheadwestderbyandliverpoolfrom1801to2011

- Peters, K., Steinberg, P., & Stratford, E. (2018). Territory beyond terra. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Peters, K., & Turner, J. (2018). Unlock the volume: Towards a politics of capacity. Antipode, 50(4), 1037–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12397

- Pérez, M. A., & Zurita, M. d. L. M. (2020). Underground exploration beyond state reach: Alternative volumetric territorial projects in Venezuela, Cuba, and Mexico. Political Geography, 79, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102144

- Pickering, S. (2016). Understanding geography and war: Misperceptions, foundations, and prospects. Springer.

- Puntigliano, A. R. (2019). The geopolitics of the catholic church in Latin America. Territory, Politics, Governance, 9(3), 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1687326

- Rugg, J. (2000). Defining the place of burial: What makes a cemetery a cemetery? Mortality, 5(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/713686011

- Rugg, J. (2013). Choice and constraint in the burial landscape: Re-evaluating twentieth-century commemoration in the English churchyard. Mortality, 18(3), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2013.819322

- Sammler, K. G. (2019). The rising politics of sea level: Demarcating territory in a vertically relative world. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(5), 604–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1632219

- Sharp, J. (2020). Materials, forensics and feminist geopolitics. Progress in Human Geography, 45, 990–1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520905653

- Sloterdijk, P. (2014). Globes: Spheres II. MIT Press. W. Hoban.

- Squire, R., & Dodds, K. (2019). Introduction to the special issue: Subterranean geopolitics. Geopolitics, 25(1), 4–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2019.1609453

- Squire, R. (2020). Companions, zappers, and invaders: The animal geopolitics of Sealab I, II, and III (1964–1969). Political Geography, 82, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102224

- Squire, R. (2021). Where theories of terrain might land: Towards ‘pluriversal’ engagements with terrain. Dialogues in Human Geography, 11(2), 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206211001035

- Theriault, N. (2017). A forest of dreams: Ontological multiplicity and the fantasies of environmental government in the Philippines. Political Geography, 58, 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.09.004

- Veal, C. (2021). Embodying vertical geopolitics: Towards a political geography of falling. Political Geography, 86, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102354

- Wang, C.-M. (2021). Securing the subterranean volumes: Geometrics, land subsidence and the materialities of things. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 39(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775820958030

- Wang, C.-M., & Chien, K.-H. (2020). Mapping the subaquatic animals in the aquatocene: Offshore wind power, the materialities of the sea and animal soundscapes. Political Geography, 83, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102285

- Wilkins, D. (2020). Where Is religion in political ecology? Progress in Human Geography, 45(2), 276–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520901772

- Woods, O. (2020). Forging alternatively sacred spaces in Singapore’s integrated religious marketplace. Cultural Geographies, 28, 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474020956396