ABSTRACT

Much debate surrounding Brexit and its implications for the Irish Border has leant on exceptionality, framed within the historical context of the ethnonational dispute between Ireland and the UK, with causality for Brexit fixed in anachronistic and unattainable imperial nationalist understandings of territorial sovereignty emanating from the English core. The Irish border resonates at both historical and metaphorical levels; it was the site of disproportionate levels of fatal political violence and has acted as an ideological battleground in the longer-term proxy war between the Irish and British patron states. Deep concern remains about the potential for Brexit to undo the progress made towards peace on the island. Yet the immediate threat now facing the border is one of unexceptional forces of neoliberalism, in which fears around resurgent ethnic conflict have been subordinated to those of market maintenance and stability. This paper considers the neglected role of, and implications for cosmopolitan nationalism under this new dispensation, identifying the Eurocentric understandings of diversity upon which the openness of borders such as that on the island of Ireland are contingent. For Ireland and Europe more generally, this necessitates a fuller reckoning with the multiple implications of ‘empire’ beyond the immediate British melancholic context.

1. RATIONALE: THE IRISH BORDER BEYOND EXCEPTION

Northern Ireland occupies an exceptional place in the UK in constitutional and historic terms. Its recent history of violent political conflict and subsequent pathway towards peace culminated in the Belfast/Good Friday (GF) Agreement of 1998 which enshrines the region's fraught history in a complex architecture of constitutional arrangements that seek to recognize the differing and contested identities that its citizens hold. The European Union (EU) has long been a key partner in this process, providing not only moral and practical support but also an ideological project of an inchoate transnational European identity which offered the potential to subsume and relegate the old ethnonational binary. The Irish border is of significance as it becomes an external border of the EU, a situation intensified by its historic role as literal and ideological battleground between the North and South of the island. The ‘Troubles’ were not only exceptional within a Western European context; they were remarkable in their particular character and intensity on the Irish border.

For these historic reasons, changes to the status of the Irish border have profound sovereignty repercussions, both pragmatic and political, for the states and citizens concerned on both sides. Not least of these have been the implications for disentangling many of the issues of rights and justice which had been elevated to the European level, matters which were deeply contentious well before Brexit (De Mars et al., Citation2018, p. 85). And yet the Irish border has also surfaced the need to look beyond these exceptional conditions and the dominant focus on atavistic English imperial nationalism (e.g., Agnew, Citation2020; Gildea, Citation2019; O’Toole, Citation2018a; Shilliam, Citation2018) by attending to the role and implications of the crisis for cosmopolitan nationalism operating under conditions of neoliberal market crisis. At a basic level, cosmopolitan nationalism is here conceived as a form of ‘post-national’ or extraterritorial (Calhoun, Citation2008) identification in which such belonging ‘leaves room for attachments to other communities, local and transnational’ (Eckersley, Citation2007, p. 677).

As the Irish experience attests, borders are often the site of persistent ethnonational tension and competition between nation-states and those borders are both reflective as well as constitutive of those ancient antagonisms (Ferriter, Citation2019; McCall, Citation2021). Such enmities have again come to the fore in the wake of the current wranglings over the Irish border but they are not the cause of it. If there is an enemy at the gates it lies in a ‘neoliberal integration that nurtures the unrestrained deterritorialising flow of capital and commodities’ (Swyngedouw, Citation2021, p. 489) with a classically insentient market (Hayek, Citation1944, pp. 20–21) now finding itself charged with the subordinate moral imperative of maintaining peace on the island of Ireland. We are witness to a crisis of capitalist coexistence arising from the competing interests of access to, and the integrity of, protected and preferential market areas, with concomitant social and political implications. The Irish border's history of violent ethnonational conflict now renders these subordinate human implications of considerable concern and poses questions about the capacity for an ‘actually existing’ cosmopolitan nationalism to handle them at the level of ideas.

Attending to these complex conceptual dynamics matters for two key reasons. The Irish border continues to receive a great deal of attention because of problems of policy implementation, notably around the Northern Ireland Protocol arrangements. The Protocol is designed to prevent the reintroduction of an internal border on the island of Ireland by keeping Northern Ireland within the EU single market for goods, thus necessitating customs checks between there and Great Britain (Coulter et al., Citation2021, pp. 283–284). However, as the debate has by necessity shifted towards issues of policy it has left unanswered questions around alternate constructions of nationalism that will continue to permeate debates within the wider Brexit conjuncture and which raise the potential for more pernicious impacts on relations between Ireland and the UK over the long term, questions which this paper addresses. Second, the attendant focus on the exceptionality of the Irish border has narrowed the concept of ‘empire’ by acting to anchor popular understandings of it at the level of the island's troubled postcolonial relationship with Great Britain whilst eclipsing a wider consideration of its unexceptional neocolonial journey to the residual spoils of European colonization within the EU. This paper provides a critical lens on these developments, tracing the philosophical roots of cosmopolitan thought in the European context and taking a historical approach to frame the Irish border within a long-term evolution in nationalist understandings of sovereignty. It argues that the reliance on exceptional dichotomizations of nationalism underpinning sovereignty claims in the Brexit conjuncture has abstracted the common colonial genesis and contemporary neocolonial animus that unites cosmopolitan and imperial constructs of nationalism on the continent. Meanwhile, misplaced distinctions between the civic and ethnic (Brubakers, Citation1999; Yack, Citation1996) have obscured social divisions at national and transnational level, ‘avoiding the need to cope with their consequences’ (Tamir, Citation2019, p. 419) and facilitated condescending and myopic understandings of a ‘post-truth politics’ (Swyngedouw, Citation2019, p. 269). This has acted to parse the exceptional and unexceptional functioning of the Irish border in intellectual debates, obscuring the agency of cosmopolitan nationalism in the current crisis and neglecting the ongoing implications of European colonization in the Republic's journey from Empire to empire. It begins by locating the consociational peace settlement in Northern Ireland in relation to wider currents and contingencies in European cosmopolitanism in the post-war era and to linked teleological evolutions in Irish nationalist ideology through the process of European integration. It then moves on to identify and challenge some of the binaries within nationalism that have perhaps inevitably been foregrounded as a result of Brexit before drawing back to our starting point and the urgent need this has revealed to engage more critically with notions of empire during future crises of capitalist coexistence.

2. COSMOPOLITANISM AND CONSOCIATION

Bhambra and Narayan (Citation2016, p. 2) identify the modern European cosmopolitan intellectual tradition as exemplified in the work of Beck (Citation2006) and Habermas (Citation2001), as having its roots in the post-war dispensation of peace and economic cooperation between the former great powers. In this period, the institutions that would become the EU began to take form, ‘organized around an expressly stated wish for the diversity of nation-states to find an equilibrium between national and cultural differences and broader and longer standing civilizational commonalities’ (Bhambra & Narayan, Citation2016, p. 2; original emphasis). The cosmopolitan theorizations of Beck (Citation2006) and Habermas (Citation2001) were based on the development of sustained peaceful and prosperous liberal democracies in Western Europe in the aftermath of total war. For Beck (Citation2006, p. 2) the march of cosmopolitanism was tied to the fortunes of globalization and its consequences, both good and bad, in which risks as well as possibilities give rise to ‘worldwide political publics’. Yet it is also an inherently European disposition as, ‘a vital theme of European civilization and European consciousness and beyond that of the global experience’ (p. 2). ‘The cosmopolitan outlook is in a certain sense a glass world’ for ‘the boundaries separating us from others are no longer blocked and obscured by ontological differences but have become transparent’ (p. 8). ‘Glass’ is an interesting metaphor to invoke for while it conveys the openness of the cosmopolitan vision, it is also suggestive of a cosmopolitan gaze, and an impermeable one at that. For critics such as Bhambra (Citation2016, Citation2017a) that vision is flawed by the absence of an engagement with Europe's colonial past and the implications of this for its postcolonial present. A longer term critique in the work of Goldberg (Citation2002, pp. 39–41) traces the underpinning liberal intellectual tradition back to the enlightenment and the emergence of the geographically bounded and rational nation-state in parallel asymmetry with the colonized Hobbesian ‘state of nature’. At the heart of Goldberg’s (Citation2002, pp. 5–6) racial state is the tension between enduring racial control and conditions which must also coexist alongside their denial and selective superficial celebrations of diversity. According to Fine and Smith (Citation2003, p. 470), Habermas’ cosmopolitanism is ‘successor to nationalism’, affirming ‘the rationality of cosmopolitanism as a fulfilment of the Enlightenment project’ (original emphasis). Given this intellectual and historical grounding it might follow that the ‘rational’ racial exclusivity of classical liberalism continues to permeate contemporary European cosmopolitanism's understandings of multicultural ‘others’ in the European midst (Bhambra, Citation2017a, p. 396). This would explain what Geary (Citation2003) identified as the mere ‘dormancy’ of nationalism, ethnocentrism and racism as ‘specters long thought exorcised from the European soul’ (3). Thus, for Césaire (Citation2000 [1950]), European civilization is fundamentally ‘stricken’ because it cannot come to terms with the two problems to which it has given rise: those of class and empire. It is then at such a profound conceptual level that the change in the status of the Irish border represents a challenge because the understandings of diversity upon which contemporary notions of cosmopolitanism within Europe are based are neither robust nor inclusive enough to be durable to the conditions of geopolitical stress which may now pertain. As Isakjee et al. (Citation2020) have found in their case studies in France and in the Balkans, it is on the external border of the EU where the ‘liberal contradictions’ of contemporary Europe play out with the greatest intensity for those also on the economic and legal margins.

On the Irish border, or in Europe more generally, Bhambra (Citation2016, p. 192) argues that diversity is limited to celebration and rarefication of the ‘cultural and linguistic’ variations that exist between populations within its privileged bounds; it does not extend to a wider recognition of multicultural others whose very presence challenges the neocolonial underpinnings of a ‘cosmopolitan’ European social space. The normative progressive assumptions previously attached to cosmopolitanism have long been brought into question. Calhoun (Citation2008) identified that cosmopolitanism ‘names a virtue of considerable importance’ for the ‘highest ethical aspirations for what globalisation can offer’ (427), but in reality may not be so different from the indelible ethno-territorial imperatives of the varieties of nationalism it looks to subordinate. This makes sense if we accept Fine and Smith’s (Citation2003, p. 470) reading of Habermas’ thought and understand European cosmopolitanism as ‘successor’ rather than reaction to the legacy of nationalism. If this is so, it then becomes necessary to further cleave that underpinning and unifying nationalism into palatable and degenerate forms. Hence, as a result the last six years have seen Manichean visions of nationalism (Brubakers, Citation1999) re-emerge in discourse on the Irish border. It has seemingly become the spatial expression of the ‘friend/enemy’ dichotomy, ‘that pits the left–liberal–cosmopolitan–capitalist elite against the populist, nativist, and socially hammered supporters of right-wing populism’ (Swyngedouw, Citation2021, p. 490). Yet a false dichotomy between racism/xenophobia and charity/philanthropy has created a ‘Janus-faced’ European populace of ‘affective idiots’ too fearful to be capable of real solidarity (Kaika, Citation2017) and both equally dependent on the maintenance of peripheral zones of refugee camps, migration enclaves, denuded citizenship, and imposed exclusion where life remains bare’ (Swyngedouw, Citation2021, p. 490). For Kaika (Citation2017, p. 1277) ‘racism/xenophobia’ and ‘charity/philanthropy’ have more in common than they do apart as depoliticized and affective practices of ‘othering’ that render issues of social solidarity and welfare provision from ‘a collective responsibility to a private affair’. Indeed, if we look to wider dynamics of multi-scalar statecraft in the EU, Wissel and Wolff (Citation2017, p. 243) see the freedoms granted to the ‘interests of capital’ in the bloc as ‘being based on a substantial de-democratization and erosion of social solidarity’. It is in this context then that returning to earlier conceptual framings of neoliberal bordering (Anderson, Citation2012) can also be fruitful in our understanding of the current crisis. Anderson (Citation2012, p. 153) prophecies the crisis conditions that have given rise to Brexit; this being a fatal disruption to the system of ‘partial and contested separation of “politics/economics”’ that had hitherto allowed for the successful alignment of ‘economic interdependencies and globalization largely unimpeded by political claims to national independence’.

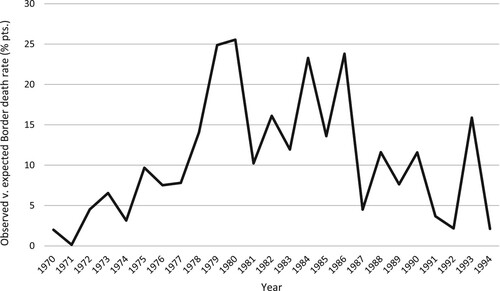

The change in the status of the Irish border is a real threat therefore not merely because of the region's exceptional recent history of violent political conflict, but because the ideological foundations of that border's everyday diversity appear to be grounded in the unexceptional cosmopolitan quicksand that has given rise to these binaries. The limits of diversity are reproduced by Northern Ireland's consociational peace arrangements (Gilligan, Citation2019), framing and petrifying racial difference in localized, persistent and familiar terms.Footnote1 In this context, it is little surprise that ‘post-conflict sensitivity’ around the land frontier has merely displaced the ongoing racial profiling and prejudices of this soft border to other points of entry (Butterly, Citation2019a, Citation2019b), rendering it largely free to perform the spatial manifestation of a tolerant accommodation between previously antagonistic groups and states.Footnote2 Indeed, echoing Salter (Citation2011) it is notable how the Irish border itself has become a sort of performative space for openness in a quite literal sense, with coverage of mock customs checks and high-profile political visits becoming something of a media ritual (Holden, Citation2020, n.p.; Coulter et al., Citation2021, p. 290). This is by no means to diminish the human significance of the border. Over the course of the Troubles over 3500 people died directly as result of the political situation (Sutton, Citation2022), and that conflict played out with disproportionate intensity on the frontier with relative fatality rates there far higher than anywhere else across Northern Ireland (Gregory et al., Citation2013, pp. 182–183) ().Footnote3 Nor should it detract from the enduring symbolic significance of the border, with not just its presence but its very manifestation seen as an inherent injustice to nationalists (Ferriter, Citation2019; McCall, Citation2021; Rankin, Citation2008), spotlighting both a microgeography of unionist settler-colonial privilege (Leary, Citation2016, pp. 41–43) and enduring political and physical insecurity (Bruce, Citation1999, p. 130; Patterson, Citation2007). The Northern Irish peace process has therefore been a remarkable accomplishment (McGarry & O’Leary, Citation2006, p. 259; O’Leary, Citation2018) in ostensibly bringing to an end decades of violent conflict in a deeply divided society. This was a state of affairs that seemed unattainable to leading voices such as Whyte (Citation1990), with Lyons’ (Citation1979, p. 192) despairing of an anarchy of the heart and mind, ‘of the collision [ … ] of seemingly irreconcilable cultures, unable to live together or to live apart, caught inextricably in the web of their tragic history’. Such an achievement can never be overstated; and yet, it has not come without a price.

Figure 1. Rate of political deaths on the Irish border per year, 1970–94).

Source: Sutton Database of Troubles Deaths hosted by CAIN (Conflict Archive on the INternet), 2022; NISRA Northern Ireland Census Grid Square Product for 1971 and 2001.

Consociation, in which opposing ethno-political groups are compelled to share executive power, can be seen as a form of multiculturalist conflict resolution (Wilson, Citation2009, p. 230) with pragmatic conceptual roots not dissimilar to debates surrounding the emergence of ‘race-relations’ sociology in the post-war period (Rex & Moore, Citation1967). This saw conflict between racialized groupings as largely inevitable and as a problem of social management emerging out of mass migration and inter-group competition rather than seeing such animosities as social, political and historical constructs (Kundnani, Citation2012). For critics, consociation is an obstacle to the development of normative liberal polities through the reifying, reinforcing and rewarding of primordial tribal identities (Taylor, Citation2006). As Gilligan (Citation2019, p. 117) identifies, ‘The GFA [Good Friday Agreement] encourages a zero-sum understanding of society, in which any gain for Catholics is perceived as a loss for Protestants, and vice versa.’ For advocates of consociationalism, it provides a ‘responsible realist’ approach in the face of a naïve integrationist idealism that elides the historical and political realities of entrenched ethnonational violence (McGarry & O’Leary, Citation2006, p. 254). Indeed, it is likely to have been the only realistic pathway to peace for a deeply divided society like Northern Ireland, but contingent as it is on the ongoing requirement to maintain stable ethnopolitical constituencies in order to retain legitimacy (Lijphart, Citation1977, p. 54) the political settlement seems to increasingly exemplify Bhambra's (Citation2016, Citation2017b) identification of Europe's self-referential and ethnocentric understanding of the very idea of diversity. This has acted to eclipse the unexceptional functioning of the Irish border in supranational terms, as reflected in the essentialist approach of both the UK and Ireland in policing their notionally ‘open’ borders as part of the ‘price’, let alone ‘dividend’ of peace (Butterly, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; MRCI, Citation2011).

3. NATIONALISM REIMAGINED

For a long time, the European project helped paper over the ideological cracks with a claim to a cosmopolitanism that provided a powerful mechanism for advancing conflict resolution goals in both moral and practical terms. This ranged from the EU PEACE initiatives from the mid-1990s, which had a wide-ranging impact at cross-community level, but also, for example, in the encouragement of increased civil service cooperation between the North and South (Tannam, Citation2018, pp. 245–246). At a practical level, the ability to be able to pool sovereignty and thus cede sensitive issues around justice or citizenship upwards to the supranational level had benefits in relieving national or devolved administrations of responsibility for these contentious and divisive matters (De Mars et al., Citation2018, p. 85). Morally, the unaligned and supportive presence of the EU was well suited to a peace process infused as it was with a central ‘constructive ambiguity’ (Mitchell, Citation2009) that allowed different political elites to impute their own meaning onto it in order to placate their own ethnonational constituencies. It is little wonder that against the great successes of the Irish peace process, the ambiguity has gone from the ‘constructive’ to the creative with boundaries within the block being reconceived as ‘bridges’ (Hayward, Citation2006, p. 897). Bridges are a frequent and powerful metaphor in the context of international relations. If any one individual can be credited with doing more than anyone else to promote peace in Northern Ireland, it must be the late John Hume, who drew upon the symbol in his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech of 1998, in which he clearly underlined the significance of the Franco-German model of post-war cooperation:

I went for a walk across the bridge from Strasbourg to Kehl. […] I stopped in the middle of the bridge and I meditated. There is Germany. There is France. If I had stood on this bridge 30 years ago after the end of the second world war when 25 million people lay dead across our continent for the second time in this century and if I had said: ‘Don't worry. In 30 years’ time we will all be together in a new Europe, our conflicts and wars will be ended and we will be working together in our common interests,’ I would have been sent to a psychiatrist. But it has happened and it is now clear that the European Union is the best example in the history of the world of conflict resolution [ … ]. (quoted in Cochrane, Citation2020, p. 176)

4. (RE)ANIMATING NATIONALIST BINARIES IN THE BREXIT CONJUNCTURE

The apparent resurgence of imperial nationalist forces behind the Brexit referendum result seems to have called a halt to this cosmopolitan ‘end of history’. Yet the ways in which imperial nationalism has been mobilized as an explanatory force in the Brexit conjecture are also at least as revealing for what they disclose of the framing power of contemporary European cosmopolitanism. For sure, there can be little doubt that the referendum result was driven by differing strains of nationalism but this was most transparently the case in the significant remain votes in Scotland and Northern Ireland. If O’Toole (Citation2016) could argue that ‘Brexit was driven by English nationalism’, notwithstanding the spatial and social complexities of the vote, then the only logical conclusion must be that secessionary nationalisms even more forcefully drove patterns of Remain voting. Here, nationalisms striving to withdraw from the UK aligned strongly with the remain campaign because for parties like the Scottish National Party (SNP), the supranational framework of the EU ‘provide[s] an external support system for an independence’ (Keating, Citation2004, p. 3) or in the case of the ethnically skewed Northern Ireland vote, it promised either stability and the status quo or an incremental technocratic and economic integration with the South. This was based in part on the empowerment of pan-European regional social and economic ties in the late 20th century which had already circumvented or subordinated (British) national structures (Keating, Citation1996, pp. 50–51). Imperial nationalist sentiment can also be read into the Leave majority vote in England and Wales because of the ‘overdetermined’ issue of immigration during the campaign (Henderson et al., Citation2017; Valluvan & Kalra, Citation2019; Virdee & McGeever, Citation2018). Indeed, some interpretations of the Brexit vote have emphasized the plight of the ‘white working class’ (Goodhart, Citation2017; Kaufmann, Citation2017), but critics (Bhambra, Citation2017b; Rogaly, Citation2019; Shilliam, Citation2018) have argued that such readings have tended to negate the long-term structural racism and elite political manipulation which have underpinned that group's position from the outset and for these authors Brexit in part reflected a broader post-imperial melancholia (Gilroy, Citation2004) for past racial homogeneity.

As Kearney (Citation1996, pp. 7–8) notes, ‘one of the most ingenuous ploys of British (or more particularly English) nationalism [is] to pretend that it doesn't exist, that the irrational and unreasonable claimants to sovereignty, territory, power and nationhood are always others’ (original emphasis). On the other hand, maybe it is too reductive to define this as nationalism at all, imperial or otherwise, when as some note (Agnew, Citation2020, pp. 2–3; MacLeod & Jones, Citation2018), Leave voting patterns appeared in large part to be a manifestation of internal economic and social fissures in English society, with a pronounced class slope in voting patterns (Ashcroft, Citation2016) that would seem to undermine Andersonian (Citation2006, p. 7) ideas of a ‘deep, horizontal comradeship’. Yet whilst an insular nativism was clear in the anti-immigrant sentiment that characterized so much of the Brexit debate (Balch & Balabanova, Citation2016), as Gilligan (Citation2018) has argued and the available evidence suggests (Wells, Citation2018), attitudes to immigration constitute an imperfect tool when used to parse nationalisms in those debates, with for example, a majority of both Leave and Remain voters supporting the ‘hostile environment’ policy under Prime Minister David Cameron. What objectively counted as a ‘cosmopolitan’ outlook in the limited confines of the European social space in 2016 was the maintenance of preferential access for groups of people who largely inherit citizenship through their white ethnicity (El-Enany, Citation2020, p. 190), with the benefits being recursive because it is the better off within the bloc who are more likely to avail of those privileges (Fligstein, Citation2008; Recchi et al., Citation2019, pp. 50–55). Yet what matters is an emphasis on (de jure if not de facto) ‘universal’ citizenship rights in the self-construction of civic nationalisms, and thus in partitioning these from their primordial ethnic forms (Tamir, Citation2019, pp. 425–426). EU citizenship works therefore as an aggregation and reflection of racialized immigration policies at national tier rather than as an ideological challenge to them (El-Enany, Citation2020, p. 190). This morality can only be sustained through the externalization of both the material, and ideological construction of the very idea of borders.

Within the EU, a share of the old nation-state sovereignty is pooled for the collective good and nothing is more symbolic of that sense of cooperation than its open internal frontiers. These can rightly be viewed with pride as, ‘The suspension of hostile, dividing state borders and the negative impacts they have had on interstate relations is perhaps a uniquely European achievement’ (Scott, Citation2012, pp. 85–86). However, as Scott (Citation2012, p. 85) also notes, whilst such symbols have become the ‘“trademark” of integration and Europeanization’, they must also be understood within a relational symbiosis of parallel ‘debordering’ and ‘rebordering’. Achiume (Citation2019, p. 1509) argues that ‘the prevailing doctrine of state sovereignty under international law today is [ … ] the right to exclude nonnationals’, and therefore we must also view contemporary international migration into the European space as an ongoing form of decolonization. This is a vision that lies well beyond the purview of any nationalism currently on offer and therefore conceptual limits need to be set. Komarova and Hayward (Citation2019) provide a technocratic cosmopolitan logic, arguing that inconsistency and incoherence in the maintenance of external border regimes in the EU, alongside the emergence of predictive, embodied, projected and preventative forms of border control mean that, ‘the most significant point about border regimes is not inclusion/exclusion across a state border but the hierarchies of rights and treatment within a jurisdiction’ (541; original emphasis). There is a dubious moral topology at play here. Rights are only enjoyed by some because they are denied to others, because they exist and have evolved as the privilege of an ethnocentric vision of historic entitlement embedded in failed and failing colonial enterprises of oppression and extraction (Bhambra, Citation2016; Citation2017a; El-Enany, Citation2020). European Unionism, like all nationalisms, is exclusive because, ‘No nation imagines itself coterminous with mankind’ (Anderson, Citation2006, p. 7), and quite deliberately so. Komarova and Hayward (Citation2019) seem to be setting the bounds for our conception of why borders matter with a Schmittian (Citation1922 [2005]) precision by deciding on where the exception lies and therefore, what is most significant. The benefit of such an understanding of borders is that it acts to externalize the ethnic problem from the outset and delineate the space in which civic nationalisms can be seen to flourish. In this way, we can see the civic and ethnic less as binaries than as a sort of continuum, and as Molnár (Citation2016) notes from the Hungarian experience, it is from active rather than weak civil society contexts that a vibrant xenophobic politics can emerge. Thus, as Appadurai (Citation2006, p. 4) reminds us, the distinction between the ‘civic’ and the ‘ethnic’ is in reality fallacious due to the ‘inherent ethnicist tendency in all ideologies of nationalism’. Civic nationalism is defined by a shared set of institutions which command loyalty and an expectation of equal participation, access to and investment in those institutions amongst all citizens (Ignatieff, Citation1993, p. 6). But if the modes of reproduction and motors of access to this ‘good life’ (Agamben, Citation1998) are essentially ethnic, this cannot be considered truly civic. More to the point, as Fozdar and Low (Citation2015) caustically observe, in its ominously vague injunctions to ‘follow our laws […] and stuff’, contemporary civic nationalism can sometimes be seen to resemble little more than a charter for mobilization around novel and more pernicious forms of ‘new racism’ (Garner, Citation2010, pp. 129–142) focussed on assimilation and the negation of cultural difference (Larin, Citation2020).

As Calhoun (Citation2002, p. 875) attests, a longer run consideration of the emergence of the civic–ethnic binary in nationalist debates raises a meta-critique of the civic mindset that is inherently supremacist, ‘The cosmopolitan ideals of global civil society can sound uncomfortably like those of the civilising mission behind colonialism.’ Tamir (Citation2019, pp. 425–426) also traces this in the dubious distinctions of Kohn (Citation1944) and Gellner (Citation1983) between a ‘high cultural’ Western European civic nationalism and a ‘primordial’ nationalism of the ‘subjugated, uneducated masses’ of the East. This also aligns with Savage et al. (Citation2010, p. 600) when they identify a historic turn to the European high cultural canon as part of a process by which external cultural signifiers are reconfigured not simply as an outward exercise, but as part of an internal process of constructing a British ‘cosmopolitan nationalism’ in the face of troublesome legacies of empire as well as the unresolved and contested pluralism at the heart of British identity (Kearney, Citation1996, p. 9).

Writing in 1996, Keating notes how the neoliberal instincts of the EU were still, at that point, being held in comparative check, with a ‘constant tension […] between the market-based vision, which would reduce it to a free-trade area and use integration as a mechanism for the neo-liberal project, and those who seek a stronger dimension’ (50). By 2016 that ideological struggle had very clearly been lost within the wider EU (Beckfield, Citation2019; Mau, Citation2015) and perhaps nowhere more so than in Ireland. The experience of the ‘poster child’ for disciplinary austerity is instructive (Coulter et al., Citation2020; Roche et al., Citation2016). Here, in the post-2007 crash context, ‘sovereignty’ proved an invaluable weapon in the neoliberal pacification of the populace. In the wake of the 2011 bailout, the potential for a progressive and socially defensive economic sovereignty (Kelton, Citation2020) was ceded with the uneven imposition by the Dublin government at the behest of the EU/European Central Bank (ECB)/International Monetary Fund (IMF) Troika of the costs of uncontrolled financial speculation and accumulation on the backs of the average Irish citizen or, ‘the real heroes and heroines’, as they were recast by the Irish political elite in 2013 (Gleeson, Citation2014; Roche et al., Citation2016, p. 13). When the heroes and heroines had re-won their sovereignty it was quickly put to the service of huge multinationals who had chosen to locate many of their global operations in Ireland due to its iniquitous tax regime. When the EU decided that the most profitable company in the world at that time – Apple, at the top of the Fortune 500 with registered revenues of US$53.4 billion in 2015 (Shi, Citation2016), had received a further €13 billion in illegal Irish state aid through the corporation tax system, the citizenry were called to rally to the flag again, with the charge from the Irish Finance Minister that the EU was ‘encroaching on Ireland's sovereignty’ (Brennan, Citation2017). It is far from mystifying then that this leads Finn (Citation2015, p. 252) to conclude that from a broader class perspective, the concept of sovereignty is at least, ‘hard to place’, lying firmly within the lexicon of both the left and right. Here, the language of ‘taking back control’ becomes more than merely a ‘myth’ of postimperial territorial sovereignty (Agnew, Citation2020); it is also by turns a reality of periodic neocolonial fiscal oppression and nativist neoliberal political mobilization.

The idealism of Kearney’s (Citation1996) ‘Europe of regions’ is laudable. More recently, Keating (Citation2021) sees both the potential for systems of social reform, and the spectre of increased neoliberal inter-regional competitions (races to the ‘top’ and ‘bottom’, respectively), that this European spatial framework can bring. But the reality is that the former remains largely unrealized and the potential for a distributed redistributive sovereignty runs counter to the EU's intensifying ideological turn away from a social democratic model of governance towards a neoliberal one (Mau, Citation2015). Given that this shift has been compounded by: a common currency seemingly working against rather than for economic integration (Stiglitz, Citation2016; Varoufakis, Citation2016); a failure to set out a common citizenship as opposed to a common set of market entitlements (Crouch, Citation2017); and the evidence of the outworking of a regional development policy leading to increased socio-spatial stratification rather than incorporation (Beckfield, Citation2019; Iammarino et al., Citation2019; Leick & Lang, Citation2018), exceptionalist interpretations of the role of ‘sovereignty’ primarily through a post-imperial prism, seem limited. Thus, whilst making claims to a more inclusive form of ‘civic’ nationalism, by wedding themselves to the European project so explicitly in the 2016 Referendum, nationalist parties were also embracing a form of neoliberal ethno-territorial citizenship embedded and offset within a supranational ‘racial state’ structure (Della Porta et al., Citation2020: Goldberg, Citation2000). The logic of Schengen always conceived that the ‘cost’ of an internal border softening was intended to be accompanied by the ‘benefit’ of a parallel external hardening (Garner, Citation2007; Zaiotti, Citation2011, pp. 71–72). Thus for Ireland (as for the UK), some of the current concerns around the Irish border reflect its future potential to act as a ‘back door’ to citizenship for underserving others. This follows the 2004 revocation of the more inclusive jus soli vision of Irish citizenship envisioned in the original 1937 Constitution in order to maintain the ethno-territorial integrity of the state and the superstate (Gilligan, Citation2018; Luibhéid, Citation2013). While in Scotland, claims to a higher civic nationalism (Davidson & Virdee, Citation2018) have been undermined by what amounts to a liberal ‘habitus’ denial of persistent sectarianism (Law, Citation2018), Islamophobia (Finlay & Hopkins, Citation2020) or a wider acknowledgement of just how inclusive a ‘civic’ independent Scottish immigration policy could be whilst operating within the constraints of the EU (Mycock, Citation2012). Perhaps an even more fundamental problem is the fact that for far too many people, ‘Scottishness is equated with whiteness’ (Peterson, Citation2020, p. 1394).

Notwithstanding all of these complexities, complexities within nationalism which Nairn (Citation1997) had identified decades before, the focus on the exceptional in intellectual and political discourse on the border has acted to crystalize rather than challenge binaries around understandings of the ideology. This is well-articulated in former EU President Jean-Claude Juncker's (Citation2018) call to reject ‘unhealthy nationalism’. This rallying cry echoed due to the alienating imperialist hubris of much Brexiteer rhetoric on the one side, whilst on the other it neatly acted to both partition and reclaim nationalism for the European cosmopolitan vision. Tolia-Kelly (Citation2020, p. 591) captures this succinctly, where we might locate the ‘unhealthy’ with movements that ‘are positioned as other to the disposition of “patriotism”, which is an indication of a developed European citizens’ sensibility’. The ‘modernisation via Europeanisation’ (Laffan, Citation2003) of Irish identity has rendered this recourse to ethnocentric exceptionalism in sovereignty debates on the Irish border more acutely problematic, because post-Brexit, it has given rise to pantomime distinctions between nationalisms at a time when a more subtle understanding of the affective power of the ideology is urgently needed.

5. COSMOPOLITAN NATIONALISM AND THE ENTANGLEMENTS OF EMPIRE

One of the most influential accounts of the Brexit conjuncture has been provided by O’Toole (Citation2016, Citation2018a), who has characterized it as an English nationalist revolt. Through both popular culture and political history, O’Toole (Citation2018a) argues that Brexit is the product of a country that has never come to terms with its imperial decline and that by voting to Leave the EU, England has only made manifest its enduring insecurities of hegemonic domination by economically more successful or socially more progressive neighbours on the European mainland, and specifically, Germany. He argues that, ‘In the imperial imagination, there are only two states: dominant and submissive, coloniser and colonised. This dualism lingers. If England is not an imperial power, it must be the only other thing it can be: a colony’ (pp. 34–35). O'Toole's analyses articulate a popular perspective on the Brexit conjuncture and one that resonates powerfully in the Irish context. Indeed, there is a real sense that Brexit was ‘made in England’, not merely demographically but ideologically given the prominence of immigration and right-wing political sentiment more generally there (Henderson et al., Citation2017). But for O’Toole (Citation2018a) such a focus also functions to both nullify dissenting political voices from within the island and to give form to imaginings of ‘deviant’ nationalism with a degree of hermeneutic violence which, given the exceptional character of the Irish border, makes it difficult to overstate the affective power of such a narrative. In Heroic Failure O’Toole (Citation2018a) enters the landscape of sexual experimentation to juxtapose the heteronormative rationalism of European integration firmly against the ephemeral pleasures of the English nationalist golden shower of Brexit. He might well be right that in that in the minds of leavers, escape was a futile attempt to invert the perceived power relations of ‘slave’ and ‘master’ or to exceed the banality of a life ‘drinking, eating and fucking’ (Foucault, Citation1994, p. 165) within the privileged confines of the EU. But in a Foucauldian analysis, the possibilities of S&M are perceived not through the heteronormative distancing crudely intended by O'Toole's extended metaphor but rather as an act which is ‘regulated and open’ between willing participants (Foucault, Citation1994, p. 152; Macey, Citation2019). Rightly or wrongly, part of the problem has clearly been that this was a relationship seen to be increasingly ‘regulated’ but not sufficiently ‘open’ to maintain the balance of ecstatic bliss between the state and the superstate any longer.

Whilst novel in terms of its application of sexual imagery, his articulation of Irish nationalism is rather more familiar than one might initially appreciate and stands in stark contrast to both the innovation and cosmopolitan drift that has been so clearly evident within the ideology in recent decades. This approach tacitly disregards the minority of unionist Leave voters in the North as effectively having not only no voice, but no culture of their own, regardless of their motivations. Their concerns cannot be understood as existing aside from those of the ‘English’, and therefore, there are echoes here of both an ancient ‘Celticism’ (Akenson, Citation1988, pp. 133–135) of implicit ‘primary [territorial] acquisition’ (Geary, Citation2003, pp. 11–12) and the potential re-emergence of a longstanding ambiguity towards sections of the British unionist tradition in the North, notwithstanding the progress made towards cultural ‘parity of esteem’ as part of the Belfast/GF Agreement (Dickson, Citation2018, p. 154). The inability to reconcile the views of a minority who do not identify with the dominant supranational aspirations of the Irish nation leads to that group being subsumed into an amorphous ‘English’ genus. The error here is one of an implicit dismissal of identity which echoes back to the more explicit past ideological failings of the newly independent Irish state in seeking to variously explain the fundamental irreconcilability of the unionist population then as ignorant ‘outlanders’, ‘foreigners’ or people of ‘mongrel’ racial pedigree (O’Halloran, Citation1987, pp. 33–37). The masochist trope is a new addition to the canon of stereotypes which Irish nationalism assembled in the early 20th century to insulate against the more fundamental ideological questions raised by successive rebuffs from unionism (O’Halloran, Citation1987, p. 47). The failure to identify with the superstate is, by extension, in the logic of O’Toole (Citation2018b) a failure to identify with the Irish nation because cosmopolitan nationalism is about the unification of ‘people’ over ‘territory’. Yet the very nature of the debate over Brexit in the South has clearly placed a substantial group outside the ‘people’ that constitute that same nation, or outside the ideological cordon sanitaire of old which the Irish border represented for both the South (O’Halloran, Citation1987, pp. 50–53) and Great Britain (Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation2007, p. 948). The ‘safety harness of joint EU membership’ Coulter et al. (Citation2021, pp. 279–280) identify captures the complexity and potential for conflict that Brexit has created surrounding citizenship in Northern Ireland (Murray, Citation2020), but in a more abstract sense it also invokes the rights that privilege and accredit different identity groups under the European model of diversity (Bhambra, Citation2016, p. 192) and the implication is that outside of such a mechanism those identities are therefore in a freefall that is not merely legal but ideational. The unifying fact is that nationalisms of all hues struggle with difference. When drafting the 1937 Constitution de Valera wrestled with exactly the same problem in seeking to define the nation in a way that might meaningfully include the Protestant population of the north-east. He could not find one and so the definition remained one of areal entitlement rather than ethnic inclusivity (Lee, Citation1989, p. 205). What is ultimately being articulated by O'Toole here is little more than a reprise of the Durkheimian ‘sacred/profane’ dichotomizations of the past in which the ‘Sassenach’ (Akenson, Citation1988, p. 135) once again sits as a placeholder for the difference in the national imaginary which cannot or will not be reconciled and for which a lexicon of alterity, still, after all this time, does not even exist.

More revealing however is the logic that states such as Ireland somehow fall outside the ‘imperial imagination’ (O'Toole, Citation2018a, p. 34): given both history and the new power geometries that he himself identifies as arising out of Brexit, this seems problematic. For countries like Ireland, so long primarily the subject of colonial oppression, its deep implication in the European project raises a particularly acute moral dilemma as it cements its position within a neocolonial framework in which the privileges it now enjoys are not only part of the booty of centuries of European imperialism but a direct response to European imperialism's mid-20th century eclipse in what Anderson (Citation2012) sees as the transition from ‘formal’ to ‘informal’ empire. A seemingly liberal rejection of imperial nationalism's ‘nostalgia for the powers of the nation-state’ (Hardt & Negri, Citation1999, p. 336) has been supplanted by an embrace of a supranational ‘imperial’ sovereignty, based not simply on powers of accumulation, but on the basis of a ‘capacity to develop itself more deeply, to be reborn’.

This takes us back to the bridge. The Franco-German model of European cooperation which arose out of the ashes of the devastation of total war is difficult not to view in messianic terms. Nor, notwithstanding what now seems like its unshakeable resolve, should the emergence of that alliance be seen as a linear and unquestionable progression (Hendriks & Morgan, Citation2001, p. 4). But as Garavini (Citation2012, p. 2) argues, explanations of the emergence of the EU grounded in either the search for an enduring post-war consensus or as a strategic response to the threat posed by the Soviet Union ignore the enormous impact of decolonization in the post-war period, when more a quarter of the world's population had revolted against European empires and won independence. An excessive focus on the Franco-German model of post-war cooperation at the expense of an understanding of the European project as a whole as grounded in the landscape of imperial decline therefore represents more than mere ethnocentrism; it is an object of pervasive epistemic imperialism in its own right. El-Enany (Citation2020, p. 184) goes some way towards excavating this lineage, quoting Belgian Prime Minister Paul-Henri Spaak speaking at the opening of the European Council in 1948:

A hundred and fifty million Europeans have not the right to feel inferior to anyone, do you hear! There is no great country in this world that can look down on a hundred and fifty million Europeans who close their ranks in order to save themselves.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This paper has sought to develop a conceptual reappraisal of the recent crisis over the future of the Irish border through a consideration of its exceptional and unexceptional aspects. The Irish border provides a vital opportunity to reflect on cosmopolitan and imperial nationalisms in sovereignty debates and their relation to other forms of reductive dichotomization in the current political moment (Kaika, Citation2017; Swyngedouw, Citation2021, p. 490). It has grounded these developments within the wider conceptual landscape of longstanding and more recent critiques of the ‘civic/ethnic’ binary within nationalism and the playing out of a Euro-bound cosmopolitanism that sets the significance of borders at an understanding of the rights and privileges granted within a space at the expense of the ethnocentric basis upon which they are awarded and inherited, or the postcolonial imperatives that still underpin their existence and extension in the transition from ‘formal’ to ‘informal’ empire (Anderson, Citation2012). For Ireland this has acted to affirm supra-territorial forms of cosmopolitan nationalism that have served as an ideological and moral spearhead in the ongoing march to ‘informal’ empire. Brexit may have revealed a strategic bifurcation between the UK and Ireland in their approach to longer term imperial ambitions, with the former's turn being interpreted by many as an anachronistic yearning for the unattainable ‘formal’ certainties of the past (Agnew, Citation2020; Gildea, Citation2019; O'Toole, Citation2018a); yet notwithstanding the current divisions, there is clearly more than unites than divides. A recognition of the ideological ties that bind may help to navigate both the EU and UK back towards shared conceptual understandings which have been imperilled by Brexit, and thus to steer through the inevitable future crises of capitalist coexistence.

In this respect the Northern Ireland Protocol arrangements are significant because they may provide a future insight into the problem-solving potential of a neoliberal cosmopolitan nationalism more generally, at least pending the more conventional juridicio-territorial re- or disintegrations that may come. The hollow territorial irredentism embodied in the rescinded Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution has been replaced by a vision in which the highest state is neither a unification of territory or (directly) people (O’Toole, Citation2018b), but of markets and by extension, people, achieved through economic rather than areal encapsulation (Holden, Citation2020, n.p.). By definition this relegates the human imperatives of these novel provisions to those of maintaining market integrity but is consistent with what Beckfield (Citation2019, p. 147) argues is the primary function of members to ‘serve’, ‘enable’ and ‘activate’ the market under the EU model. In practice, this subordination was laid bare on 29 January 2021 with the European Commission's abortive invocation of Article 16 in order to prevent the export of Covid-19 vaccines across the border less than a month into the new arrangements (Rea, Citation2021) but has now been realized by the British government's unilateral plans to withdraw from elements of the Protocol completely (Truss, Citation2022). For both the EU and UK, what we see in the current wrangling is a precise identification of what Anderson and O’Dowd (Citation2007) identify as imperialism's enduring ability to ‘subordinate nationalisms allied with those imperial powers’ (Anderson, Citation2012, p. 147). These commonalities around the functioning of policy in practice would further seem to underline what Nairn (Citation1997) has identified as the true Janus face of contemporary nationalism, less ideological than it is responsive to economic crises and contingent upon prevailing geopolitical circumstances. The current crisis of capitalist coexistence on the Irish border appears to meet these conditions precisely.

To be sure, the salience of imperial nationalism to the UK's Brexit debate underscores what Agnew (Citation2020) seemingly laments in the ‘myth of territorial sovereignty’ and what Stephens (Citation2013, pp. 1–2) identifies as the ideology's ‘persistence’ in terms of the enduring centrality of the nation-state and its fixation on discriminating between supposed ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’. To that we must add the neglected implications that arise for an actually existing cosmopolitan nationalism from the Irish context which reveal that the relationship between neoliberalism and nationalism can metastasize beyond the level of interdependency Harvey (Citation2005, p. 85) identifies in ways which speak to the relentless dynamism of national imaginaries rather than the stasis which notions of ‘persistence’ might initially imply (Stephens, Citation2013, p. 111). Ultimately, the Irish experience suggests that the myth of the nation can no longer be limited solely to either retrospective ethnocentric fantasies of its racial genesis (Geary, Citation2003, p. 11) or uncorruptible and unattainable aspirations of its ‘territorial sovereignty’ (Agnew, Citation2020) but must also now be extended to embrace immanent dreams of its full political, economic and ethnoterritorial apotheosis within the neoliberal superstate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to Mike Savage, Nick Megoran and Anoop Nayak for their comments on earlier versions of this paper, and to the editor and anonymous referees for their generosity of time and insight. Finally, my sincere thanks to Malcolm Sutton and Martin Melaugh of CAIN (Conflict Archive on the INternet) for the data relating to political deaths.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Saoudi' (Citation2021) provides insights into the persistent realties of everyday racism experienced by a British Algerian growing up in mid-Ulster during and after the Good Friday Agreement.

2 From at least 2003 (Flanagan, Citation2018), ‘Operation Gull’ regularly involved practices of racial profiling by Irish and UK border forces (Latif & Martynowicz, Citation2009, pp. 62–74). The ostensible rationale was to identify ‘those circumventing the relaxed immigration controls in the CTA between the two nations’, but the wider context was the common tide of rising anti-immigrant sentiment in both jurisdictions politically legitimated by a focus on welfare system abuses (Lally, Citation2006).

3 The border is defined as including fatalities and demographics from 1 km2 cells within 10 km of the borderline by Euclidian distance and excluding the major settlements of Derry/Londonderry, Newry and Strabane. Only continuous years in which there were 25 or more deaths in the border region were included.

REFERENCES

- Achiume, E.T. (2019). Migration as decolonization. Stanford Law Review, 71(6), 1509–1574. https://www.stanfordlawreview.org/print/article/migration-as-decolonization/

- Agamben, G. (1998). Homo sacer. Stanford University Press.

- Agnew, J. (2020). Taking back control? The myth of territorial sovereignty and the Brexit fiasco. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1687327

- Akenson, D. H. (1988). Small differences. Irish Catholics and Irish protestants, 1815–1922. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities. Verso.

- Anderson, J. (2012). Borders in the new imperialism. In T. M. Wilson & H. Donnan (Eds.), A companion to border studies (pp. 139–157). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Anderson, J., & O’Dowd, L. (2007). Imperialism and nationalism: The Home Rule Struggle and border creation in Ireland, 1885–1925. Political Geography, 26(8), 934–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.10.001

- Appadurai, A. (2006). Fear of small numbers. Duke University Press.

- Ashcroft, M. (2016, June 24). How the United Kingdom voted on Thursday … and why. Lord Ashcroft Polls website. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://lordashcroftpolls.com/2016/06/how-the-united-kingdom-voted-and-why/

- Balch, A., & Balabanova, E. (2016). Ethics, politics and migration: Public debates on the free movement of Bulgarians and Romanians in the UK, 2006–2013. Politics, 36(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12082

- Beck, U. (2006). Cosmopolitan vision. Polity Press.

- Beckfield, J. (2019). Unequal Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Bhambra, G. K. (2016). Whither Europe? Postcolonial versus neocolonial cosmopolitanism. Interventions, 18(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2015.1106964

- Bhambra, G. K. (2017a). The current crisis of Europe: Refugees, colonialism, and the limits of cosmopolitanism. European Law Journal, 23(5), 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12234

- Bhambra, G. K. (2017b). Brexit, Trump, and ‘methodological whiteness’: On the misrecognition of race and class. British Journal of Sociology, 68(S1), S214–S232. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12317

- Bhambra, G. K., & Narayan, J. (2016). Introduction. In G. K. Bhambra & J. Narayan (Eds.), European cosmopolitanism (pp. 1–13). Routledge.

- Brennan, J. (2017, February 3). Getting to the core of Europe’s case against Apple and Ireland. Irish Times.

- Brubakers, R. (1999). The Manichean myth: Rethinking the distinction between ‘ethnic’ and civic’ nationalism. In K. Hanspeter, K. Armingeon, H. Siegrist, & A. Wimmer (Eds.), Nation and national identity (pp. 55–71). Purdue University Press.

- Bruce, S. (1999). Unionists and the border. In M. Anderson & E. Bort (Eds.), The Irish border (pp. 127–138). Liverpool University Press.

- Butterly, L. (2019a, December 19). Ireland’s invisible frontier. New Internationalist.

- Butterly, L. (2019b, January 7). Northern Ireland’s hidden borders. Verso Blog website. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4194-northern-ireland-s-hidden-borders

- Calhoun, C. (2002). The class consciousness of frequent travelers: Towards a critique of actually existing neoliberalism. South Atlantic Quarterly, 101(4), 869–897. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-101-4-869

- Calhoun, C. (2008). Cosmopolitanism and nationalism. Nations and Nationalism, 14(3), 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2008.00359.x

- Césaire, A. (2000 [1950]). Discourse on colonialism. Monthly Review Press.

- Cochrane, F. (2020). Breaking peace. Manchester University Press.

- Coulter, C., Arqueros-Fernández, F., & Nagle, A. (2020). Austerity’s model pupil: The ideological uses of Ireland during the Eurozone crisis. Critical Sociology, 45(4–5), 697–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920517718038

- Coulter, C., Gilmartin, N., Hayward, K., & Shirlow, P. (2021). Northern Ireland a generation after Good Friday. Manchester University Press.

- Crouch, C. (2017). Neoliberalism, nationalism and the decline of political traditions. The Political Quarterly, 88(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12321

- Davidson, N., & Virdee, S. (2018). Introduction. In N. Davidson & S. Virdee (Eds.), No problem here: Understanding racism in Scotland (pp. 9–12). Luath Press.

- Della Porta, D., O’Connor, F., & Portos, M. (2020). The framing of secessionism in the neo-liberal crisis: The Scottish and Catalan cases. In C. Closa, C. Margiotta, & G. Martinico (Eds.), Between democracy and law (pp. 153–170). Routledge.

- De Mars, S., Murray, C., O’Donoghue, A., & Warwick, B. (2018). Bordering two unions. Policy Press.

- Deutsch, K. W. (1953). Nationalism and social communication. Cambridge University Press.

- Deutsch, K. W., Burrell, S. A., Kann, R. A., Lee Jr., M., Lichterman, M., Lindgren, R. E., Loewenheim, F. L., & Van Wagenen, R. W. (1957). Political community and the North Atlantic Area. Princeton University Press.

- Dickson, B. (2018). Law in Northern Ireland. Bloomsbury.

- Eckersley, R. (2007). From cosmopolitan nationalism to cosmopolitan democracy. Review of International Studies, 33(4), 675–692. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210507007723

- El-Enany, N. (2020). Bordering Britain. Manchester University Press.

- Ferriter, D. (2019). The border. Profile Books.

- Fine, R., & Smith, W. (2003). Jürgen Habermas’s theory of cosmopolitanism. Constellations, 10(4), 469–487. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1351-0487.2003.00348.x

- Finlay, R., & Hopkins, P. (2020). Resistance and marginalization: Islamophobia and the political participation of young Muslims in Scotland. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(4), 546–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019.1573436

- Finn, D. (2015). Ireland, the left and the European Union. In C. Coulter & A. Nagle (Eds.), Ireland under austerity (pp. 241–259). Manchester University Press.

- FitzGerald, G. (1972). Towards a new Ireland. Charles Knight & Co.

- FitzGerald, G. (2003). Reflections on the Irish State. Irish Academic Press.

- FitzGerald, G. (2005, August 23). Ireland under two unions, 1805–2005 [Speech]. Merriman Summer School, Ennistymon, Co. Clare, Ireland. Cited in A. Quinlivan (2005, August 24). EU membership vindicated Irish independence, says FitzGerald. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/eu-membership-vindicated-irish-independence-says-fitzgerald-1.483608

- Flanagan, C. (2018, January 31). Commencement matters, – garda deployment. Seanad Éireann Debate, 255(10). [Official report]. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/seanad/2018-01-31/3/#s7.

- Fligstein, N. (2008). Euroclash. Oxford University Press.

- Foucault, M. [Tr. P. Rabinow] (1994). Ethics Vol. I. New Press.

- Fozdar, F., & Low, M. (2015). ‘They have to abide by our laws … and stuff’: Ethnonationalism masquerading as civic nationalism. Nations and Nationalism, 21(3), 524–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12128

- Garavini, G. (2012). After empires. Oxford University Press.

- Garner, S. (2007). The European Union and the racialization of immigration, 1985–2006. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts, 1(1), 61–87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25594976

- Garner, S. (2010). Racisms. Sage.

- Geary, P. J. (2003). The myth of nations. Princeton University Press.

- Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and nationalism. Blackwell.

- Gildea, R. (2019). Empires of the mind. Cambridge University Press.

- Gilligan, C. (2018, November 7). Brexit, the Irish border and human freedom. With Sober Senses – Marxist Humanist Initiative website. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.marxisthumanistinitiative.org/international-news/brexit-the-irish-border-and-human-freedom.html

- Gilligan, C. (2019). Northern Ireland and the limits of the race relations framework. Capital & Class, 43(1), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309816818818090

- Gilroy, P. (2004). After empire. Routledge.

- Gleeson, C. (2014, November 6). Jean-Claude Trichet and the Irish bailout: A timeline. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/jean-claude-trichet-and-the-irish-bailout-a-timeline-1.1990882

- Goldberg, D. T. (2000). Racial knowledge. In L. Back & J. Solomos (Eds.), Theories of race and racism (pp. 154–180). Routledge.

- Goldberg, D. T. (2002). The racial state. Blackwell.

- Goodhart, D. (2017). The road to somewhere. Hurst & Company.

- Gregory, I. N., Cunningham, N. A., Lloyd, C. D., Shuttleworth, I. G., & Ell, P. S. (2013). Troubled geographies: A spatial history of religion and society in Ireland. Indiana University Press.

- Habermas, J. (2001). The postnational constellation. Polity Press.

- Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (1999). Empire. Harvard University Press.

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

- Hayek, F. A. (1944). The road to serfdom. University of Chicago Press.

- Hayward, K. (2006). National territory in European space: Reconfiguring the island of Ireland. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 897–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00639.x

- Henderson, A., Jeffery, C., Wincott, D., & Wyn Jones, R. (2017). How Brexit was made in England. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(4), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117730542

- Hendriks, G., & Morgan, A. (2001). The Franco-German axis in European integration. Edward Elgar.

- Holden, P. (2020). Territory, geoeconomics, and power politics: The Irish government’s framing of Brexit. Political Geography, 76, 102063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102063

- Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby021

- Ignatieff, M. (1993). Blood and belonging. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- Isakjee, A., Davies, T., Obradović-Wochnik, J., & Augustová, K. (2020). Liberal violence and the racial borders of the European Union. Antipode, 52(6), 1751–1773. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12670

- Juncker, J.-C. (2018, September 12). The hour of European sovereignty [Speech]. European Commission State of the Union Address 2018. European Parliament, Strasbourg, France. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/priorities/state-union-speeches/state-union-2018_en

- Kaika, M. (2017). Between compassion and racism: How the biopolitics of neoliberal welfare turns citizens into affective ‘idiots’. European Planning Studies, 25(8), 1275–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1320521

- Kaufmann, E. (2017). ‘Racial self-interest’ Is not racism. Policy Exchange.

- Kearney, R. (1996). Postnationalist Ireland. Routledge.

- Keating, M. (1996). Nations against the state. Macmillan.

- Keating, M. (2004). European integration and the nationalities question. Politics & Society, 32(1), 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329204267295

- Keating, M. (2021). Beyond the nation-state: Territory, solidarity and welfare in a multiscalar Europe. Territory, Politics, Governance, 9(3), 331–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1742779

- Kelton, S. (2020). The deficit myth. John Murray.

- Kiberd, D. (1996). Inventing Ireland: The literature of the modern nation. Vintage.

- Kohn, H. (1944). The idea of nationalism: A study of its origins and background. Macmillan.

- Komarova, M., & Hayward, K. (2019). The Irish border as a European Union frontier: The implications for managing mobility and conflict. Geopolitics, 24(3), 541–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2018.1496910

- Kundnani, A. (2012). Multiculturalism and its discontents: Left, right and liberal. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 15(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549411432027

- Laffan, B. (2003). Ireland: Modernisation via Europeanisation. In W. Wessels, A. Maurer, & J. Mittag (Eds.), Fifteen into One? The European Union and its member states (pp. 248–270). Manchester University Press.

- Laffan, B., & Tonra, B. (2010). Europe and the international dimension. In J. Coakley & M. Gallagher (Eds.), Politics in the republic of Ireland (pp. 407–433). Routledge & PSAI.

- Lally, C. (2006, September 11). Operation Gull swoops on welfare fraudsters. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/operation-gull-swoops-on-welfare-fraudsters-1.1001015

- Larin, S. J. (2020). Is it really about values? Civic nationalism and migrant integration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1591943

- Latif, N., & Martynowicz, A. (2009). Our hidden borders. Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission.

- Law, A. (2018). The trouble with sectarianism. In N. Davidson & S. Virdee (Eds.), No problem here: Understanding racism in Scotland (pp. 90–112). Luath Press.

- Leary, P. (2016). Unapproved roads. Oxford University Press.

- Lee, J. J. (1989). Ireland 1912–1985: Politics & society. Cambridge University Press.

- Leick, B., & Lang, T. (2018). Re-thinking non-core regions: Planning strategies and practices beyond growth. European Planning Studies, 26(2), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1363398

- Lijphart, A. (1977). Democracy in plural societies. Yale University Press.

- Luibhéid, E. (2013). Pregnant on arrival. University of Minnesota Press.

- Lyons, F. S. L. (1979). Culture and anarchy in Ireland. Clarendon Press.

- Macey, D. (2019). The lives of Michel Foucault. Verso.

- MacLeod, G., & Jones, M. (2018). Explaining ‘Brexit capital’: Uneven development and the austerity state. Space and Polity, 22(2), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2018.1535272

- Mau, S. (2015). Inequality, marketization and the majority class. Palgrave Macmillan.

- McCall, C. (2021). Border Ireland. Routledge.

- McGarry, J., & O’Leary, B. (2006). Consociational theory, Northern Ireland’s conflict and its agreement 2. What critics of consociation can learn from Northern Ireland. Government & Opposition, 41(2), 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2006.00178.x

- Migrant Rights Centre Ireland (MRCI). (2011). Singled out. MRCI.

- Mitchell, D. (2009). Cooking the fudge: Constructive ambiguity and the implementation of the Northern Ireland agreement, 1998–2007. Irish Political Studies, 24(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907180903075751

- Molnár, V. (2016). Civil society, radicalism and the rediscovery of mythic nationalism. Nations & Nationalism, 22(1), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12126

- Murray, C. (2020, April 6). EU citizenship rights in Northern Ireland. UK in a changing Europe website. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://ukandeu.ac.uk/eu-citizenship-rights-in-northern-ireland/

- Mycock, A. (2012). SNP, identity and citizenship: Re-imagining state and nation. National Identities, 14(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2012.657078

- Nairn, T. (1997). Faces of nationalism. Verso.

- Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

- O’Halloran, C. (1987). Partition and the limits of Irish nationalism. Gill & Macmillan.

- O’Leary, B. (2018). The twilight of the United Kingdom & tiochfaidh ár lá: Twenty years after the Good Friday Agreement. Ethnopolitics, 17(3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2018.1473114

- O’Toole, F. (2016, June 19). Brexit is being driven by English nationalism. And it will end in self-rule. Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/18/england-eu-referendum-brexit

- O’Toole, F. (2018a). Heroic failure. Head of Zeus.

- O’Toole, F. (2018b, May 26). A united Ireland isn’t what it used to be. Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/fintan-o-toole-a-united-ireland-isn-t-what-it-used-to-be-1.3507019

- Patterson, H. (2007). In the land of King Canute: The influence of border unionism on Ulster unionist politics, 1945–63. Contemporary British History, 20(4), 511–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/13619460600612487

- Peck, T. (2017, September 3). EU chief negotiator Michel Barnier says he will ‘teach the UK what leaving the single market means. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/michel-barnier-david-davis-brexit-educational-teach-uk-leaving-single-market-negotiations-a7927336.html

- Peterson, M. (2020). Micro aggressions and connections in the context of national multiculturalism: Everyday geographies of racialisation and resistance in contemporary Scotland. Antipode, 52(5), 1393–1412. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12643

- Rankin, K. (2008). Deducing rationales and political tactics in the partitioning of Ireland, 1912–1925. Political Geography, 26(8), 909–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.09.006

- Rea, A. (2021, January 29). The EU has surrendered the moral high ground over the Irish border. New Statesman. https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/the-staggers/2021/01/eu-has-surrendered-moral-high-ground-over-irish-border

- Recchi, E., Favell, A., Apaydin, F., Barbulescu, R., Braun, M., Ciornei, I., Cunningham, N., Díez Medrano, J., Duru, D. N., Hanquinet, L., Pötzschke, S., Reimer, D., Salamońska, J., Savage, M., Solgaard Jensen, J., & Varela, A. A. (2019). Everyday Europe: Social transnationalism in an unsettled continent. Policy Press.

- Rex, J., & Moore, R. (1967). Race, community and conflict. Oxford University Press.

- Roche, W. K., O’Connell, P. J., & Prothero, A. (Eds.). (2016). Austerity and recovery in Ireland: Europe’s poster child and the Great Recession. Oxford University Press.

- Rogaly, B. (2019). Brexit writings and the war of position over migration, ‘race’ and class’. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X18811923f

- Salter, M. (2011). Places everyone! Studying the performativity of the border. In C. Johnson, R. Jones, A. Paasi, L. Amoore, A. Mountz, M. Salter, & C. Rumsford (Eds.), Interventions on rethinking ‘the border’ in border studies. Political Geography, 30(2), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.01.002

- Saoudi, L. (2021). The mid-Ulster male. In J. C. Patterson (Ed.), The new frontier (pp. 56-67). New Island.

- Savage, M., Wright, D., & Gayo-Cal, M. (2010). Cosmopolitan nationalism and the cultural reach of the white British. Nations and Nationalism, 16(4), 598–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2010.00449.x

- Schmitt, C. (1922 [2005]). Political theology. University of Chicago Press.

- Scott, J. W. (2012). European politics of borders, border symbolism and cross-border cooperation. In T. M. Wilson & H. Donnan (Eds.), A companion to border studies (pp. 83–99). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Shi, A. (2016, June 8). Here are the 10 most profitable companies. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2016/06/08/fortune-500-most-profitable-companies-2016/

- Shilliam, R. (2018). Race and the undeserving poor. Agenda.

- Stephens, A. C. (2013). The persistence of nationalism. Routledge.

- Stevis-Gridneff, M. (2022, October 17). Crude comments from Europe's top diplomat point to bigger problems. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/17/world/europe/eu-ukraine-josep-borrell-fontelles.html.

- Stiglitz, J. (2016). The Euro and its threat to the future of Europe. Allen Lane.

- Sutton, M. (2022, September 20). An index of deaths from the conflict in Ireland. Conflict Archive on the INternet (CAIN) website. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/sutton/index.html

- Swyngedouw, E. (2019). The perverse lure of autocratic postdemocracy. South Atlantic Quarterly, 118(2), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-7381134

- Swyngedouw, E. (2021). From disruption to transformation: Politicisation at a distance from the state. Antipode, 53(2), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12691

- Tamir, Y. (. (2019). Not so civic: Is there a difference between ethnic and civic nationalism? Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-022018-024059

- Tannam, E. (2018). Intergovernmental and cross-border civil service cooperation: The Good Friday Agreement and Brexit. Ethnopolitics, 17(3), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2018.1472422

- Taylor, R. (2006). The Belfast Agreement and the politics of consociationalism: A critique. The Political Quarterly, 77(2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2006.00764.x

- Tolia-Kelly, D. (2020). Affective nationalisms and race. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38(4), 589–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420912445e

- Truss, L. (2022, May 17). Northern Ireland Protocol: Foreign Secretary’s statement. [Oral Statement to Parliament]. British Government website. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/northern-ireland-protocol-foreign-secretarys-statement-17-may-2022

- Valluvan, S., & Kalra, V. S. (2019). Racial nationalisms: Brexit, borders and little Englander contradictions. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(14), 2393–2412. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1640890

- Varoufakis, Y. (2016). And the weak suffer what they must? Bodley Head.

- Virdee, S., & McGeever, B. (2018). Racism, crisis, Brexit. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(10), 1802–1819. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1361544

- Wells, A. (2018, April 27). Where the public stands on immigration. YouGov Politics website. Retrieved September 21, 2022, from https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2018/04/27/where-public-stands-immigration?sectors,political=

- Whyte, J. H. (1990). Interpreting Northern Ireland. Clarendon Press.

- Wilson, R. (2009). From consociationalism to interculturalism. In R. Taylor (Ed.), Consociational theory: McGarry and O’Leary and the Northern Ireland conflict (pp. 221–236). Routledge.

- Wissel, J., & Wolff, S. (2017). Political regulation and the strategic production of space: The European Union as a post-Fordist state spatial project. Antipode, 49(1), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12265

- Yack, B. (1996). The myth of the civic nation. Critical Review, 10(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913819608443417

- Zaiotti, R. (2011). Cultures of border control. University of Chicago Press.

- Zielonka, J. (2006). Europe as empire. Oxford University Press.