ABSTRACT

This study contributes to understanding territorialization, as the intersection between territoriality and citizenship, with claims-making as a mechanism. It applies a process tracing technique to analyse diverse qualitative data about a contentious 2018 referendum in Ghana to separate some of its regions. Through this, the study highlights three empirical features of territorialization. One is the strategies political parties adopted in their manifestos to enable them to claim credit for the region’s separation. Another is the historical connections that regionally based citizens made to contemporary issues to strengthen their claim over territorial matters. The third is the connections of solidarity that diaspora-based citizens made with the territorial issues raised by regionally based citizens.

1. INTRODUCTION

Many studies on the concept of territory focus on geographically bounded spaces (see Agnew, Citation1994; Giddens, Citation1987; Gottmann, Citation1975). The reason for these geographical foundations of territorial studies is the primary focus that the state placed on borders and border integrity. As Sassen (Citation2013, p. 22) notes, the state’s authority over its borders led to ‘a naturalising of territory as what is encased in national borders’. However, territory can also take on fluid conceptualizations sensitive to the concept’s processual dynamics: ‘territorialization’. Brighenti conceptualizes territorialization as ‘a way of materially defining, inscribing and stabilising patterns of relations’ within society. In that sense, ‘territory is the effect of the material inscription of social relationships which are immaterial, or better, affective’ (Brighenti, Citation2010, p. 223). Many others have followed this conceptual rather than geographical analysis of territory (see examples: Elden, Citation2010; Sassen, Citation2013), and this study follows such trajectories by using analytical innovations to stretch out the concept. Thus, the central argument of this paper is conceptual. The paper argues that ‘territorialization’ can be understood as a territory-making process observed in citizens’ claims and counterclaims during a political process focused on a territorial question. It uses the empirical case of Ghana’s region separation referendum in 2018 to illustrate this conceptual argument.

This study also responds to the call to ‘bring sub-national border-making processes to the fore in the literature’, especially in the context of Africa (Ramutsindela, Citation2019). Whilst that call is relevant, it is also challenging because the co-concepts through which territory gains its fluidity are mainly regulated at the national or state level. For instance, policy-making around concepts that enrich the understanding of territory, such as ‘citizenship’ (Desforges et al., Citation2005; Spinney et al., Citation2015), ‘the environment’ (Zimmerer, Citation2015), ‘business interest’ (Wood et al., Citation2005), or ‘rankings’ (Öjehag-Pettersson, Citation2020), are heavily concentrated at the national or state level. Therefore, any attempt to demonstrate territory-making processes at the sub-national level will require finely aggregated pieces of observation that transcend the local, regional, or national. This study attempts this by connecting territoriality with citizenship, using the case of region separation resistance in Ghana.

Between June 2017 and December 2018 (20 months), the government of Ghana supervised a limited referendum in response to petitions to separate four regions in the country to create six new ones. The referendum, which occurred on 27 December 2018, was the first of its kind and thus historic. Though not the first time a referendum was being held in Ghana, this referendum was unique because it was the first time ever that a referendum was held to decide the question of a regional split under any of Ghana’s constitutions. But it was not without controversy. As part of the referendum, stakeholders both in favour of and against the separation campaigned to achieve their objectives. The process unfolded in mainly two patterns of either conflict or cooperation between actors in the departing region and those in the stump region (Welsing, Citation2018) (more details on the case are presented in a later section). This study traces observations connected to one typical case of these contentions in the Volta Region to show how the claims and counterclaims contribute to territorialization. The analysis highlights three such empirical processes of territorialization. One was the strategies political parties adopted in their manifestos to make them claim ownership of the regional separation idea. Another was the historical connections that regionally based citizens made to contemporary issues to strengthen their claim over territorial matters. The third was the emotional solidarity connections that diaspora-based citizens made with the territorial matters raised by regionally based citizens.

The study’s findings connect to other conceptual perspectives about the theme within the literature. For instance, the claims made by the various interested actors demonstrate the ‘embedded logics of power and claim-making’ that contribute insight to the ‘capability approach’ for understanding territory (Sassen, Citation2013, p. 23). In addition, the findings contribute meaning to two main concepts relevant for understanding territorialization: i.e., ‘territoriality’ and ‘citizenship’. Regarding citizenship, the empirics illustrate the ‘social processes at work in citizenship’ (Desforges et al., Citation2005, p. 446) during mobilization processes that transcend a geographically bounded place. Regarding territoriality, it highlights the ‘performativity’ of the concept as a process of social relations (Öjehag-Pettersson, Citation2020, p. 627). The study’s findings also support drawing an analytic congruence between stronger and weaker themes of separatism because it finds an expanding trajectory of territorialization, similar to what others have identified in secessionist processes (see Nelson, Citation2021).

Moreover, it adds to empirical evidence of such sub-national reorganization processes in Africa (Mavungu, Citation2016) as well as the small body of emerging literature that explains the outcomes of such territorial politics from a mechanism-based perspective (Bae, Citation2016; Heinelt, Citation2019; Holtermann, Citation2019; Nelson, Citation2021; van Mierlo, Citation2021). Concerning such empirical literature on Ghana, this article builds on Penu’s (Citation2022b, p. 571) findings that region separation resistance in Ghana occurs through a bottom-up mechanism ‘from the community to the regional, national and diaspora levels’. This study advances that argument by showing that this bottom-up mechanism is not merely meaningful in terms of physical geography but also from the perspective of political geography in a manner that enriches understanding of how territory can be made and unmade through claim-making.

The article is further organized as follows. The next section introduces the theoretical context of this study by reviewing some perspectives on the concept of territorialization. Then there is a brief analytical discussion of the decentralization literature to identify how territorialization can be studied using a connection between structural and non-structural factors. This culminates in a summary conceptualization of territorialization as a series of citizens’ claims-making on territorial matters. The empirical analysis begins with a brief introduction to the regional governance architecture in Ghana to provide some context. This is followed by a presentation of the empirical findings in three main sub-sections (from the national, regional and diaspora dimensions). The concluding section outlines the study’s theoretical contribution to understanding contentious (sub-national) territorial reorganization (especially in Africa, where colonial legacy plays an important role) and other concepts such as territory and separatism.

2. CONCEPTUALIZING TERRITORIALIZATION: WHEN TERRITORIALITY MEETS CITIZENSHIP

The framework guiding this study conceptualizes territorialization as essentially territory-making. This conceptual framework is built around the connection between two co-concepts relevant to understanding territorialization: ‘territoriality’ and ‘citizenship’. After all, territorialization demarcates, even if virtually, those who belong and those who don’t belong to the territory in focus.

Sack (Citation1986, p. 19) conceptualizes territoriality as ‘the results of strategies to affect, influence, and control people, phenomena, and relationships’. Elden (Citation2010, p. 801) notes that ‘“territoriality” has today a rather more active connotation’, i.e., ‘operating toward that territory’. For Sassen, one idea of territoriality concerns the actions beyond the geographical zone but with implications for the defined geographical zone. (Sassen, Citation2013, p. 25). Thus, in this study, territoriality is defined effectively as a set of actions in relation to territorial matters, be it spatial or virtual. These actions may be performed by various actors, but most relevant are the actions of citizens identifying themselves with the geographical territory. Thus, citizenship is also relevant for an analysis of territorialization.

Citizenship is relevant to understanding territorialization because it transcends different spatial levels to escape the limitations other concepts, such as nationality, face. Citizenship is ‘mobilized’ by sharing a common territorial space (Spinney et al., Citation2015, p. 327), irrespective of the scale of the territorial space in question, be it state, regional, provincial or community level. Within the literature, conceptualizations of citizenship have moved ‘from the spaces and places of citizenship, to the scales of citizenship, to the landscapes of citizenship’ (Desforges et al., Citation2005, p. 442). Thus, in agreement with (Bauder, Citation2014, p. 97), territorial presence is not synonymous with formal belonging in the territorial community as long as the claim maker or supporter can find a narrative to connect to the issues concerning that territorial community. For that matter, citizenship is defined in this study as an instance where a person has or claims to have an interest in a spatial issue, irrespective of whether this spatial issue is geographically or non-geographically bound. The study adopts this mobilized concept of citizenship because, as will be seen in the empirics, different actors (especially diaspora-based actors) joined the claim and counterclaim-making around Ghana’s region separation resistance, and this mobilization was based on narratives used to consciously solicit support for the claims made.

Citizenship also matters for understanding territorialization when territory is considered in spatio-relational terms. Elden (Citation2010, p. 799) argues that territory needs to be understood in terms of its ‘relation with space’. However, if we considered territories as more than geographical locations, but rather as ‘points of convergence, prolongation and tension’ … ‘between spaces and relationships, between extensions (movements) and intensions’ (Brighenti, Citation2010, p. 223), then it becomes apparent why citizenship as a process of mobilization can be central to understanding territorialization. An example is the connection Zimmerer observes in a Bolivian case study of environmental governance between indigenous identity-making and environmental governance, on the one hand, and expanded resource extraction and nationalism, on the other (Zimmerer, Citation2015, p. 323). Such examples show that territories become relevant depending on the values that identified interested groups mobilize to attach to them. Usually, such mobilization is led by influential members of the community. For instance, Gustafsson and Scurrah’s (Citation2020, p. 1) analysis of the contentions surrounding the extractive frontiers in Peru suggests that ‘an interplay between institutional capacity and supporting coalitions’ affects whether subnational leaders undertake a collaborative or a confrontational approach. Thus, both the citizens and the structural context within which the citizens operate matter for territorial behaviour. Indeed, this Ghanaian case study will show how the claims made by some community leaders were instrumental in sustaining the territory-making process.

A territorial analysis also needs to pay attention to tangible and intangible matters under contention. During territorial disputes, Hensel and Mitchell argue that claims can be aimed at either matters of tangible or intangible salience or both (Hensel & Mitchell, Citation2005, p. 278). Both of these are important for mobilization. As will be seen in the empirics of the Ghanaian case, the separation of the region touched on both tangibly and intangibly salient matters, making it easy to mobilize collective support for the claims. Further, the collective actions driving the mobilization were observed as ‘contentious performances’ (Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015), such as protests, court suits and ethnocentric rhetoric. These contentious performances illustrated territorial behaviour because they formed a ‘part of complex organizational assemblages that cut across the national border and which were made in relation to authority and rights’, sometimes connected to a ‘sociohistorical construct’ (Sassen, Citation2013, pp. 23–25).

Territorialization is also animated through partisan politics. To understand the mechanisms that make territorialization contentious, it is important to pay attention to the deep politics informing citizens’ actions around territorial splits, even if there are seemingly low stakes involved. Again, here these matters may or may not be tangible. Kenny (Citation2022), for instance, illustrates one angle of intangibility in a study about the debates in England after Brexit, which is also a classic case of territorialization without actual geographical markings. As Kenny notes, the ‘shifting cross-currents of English sentiment in the decade leading up to the Brexit vote leads to a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics and character of political Englishness’ (Kenny, Citation2022, p. 686). The political considerations may also be tangible because territorial reorganization most likely leads to changes in the allocation of functions and responsibilities between levels or scales of government (Wood et al., Citation2005, p. 295). Hence the territorial ramification of such reorganization is better understood by gauging citizens’ (especially politicians’) reactions to the perceived changes that such a reorganization will present to the relationship between different interested actors or between local interested actors and state structures.

Political actors, whether ethnic-based, religion-based or party-based, are usually interested in any form of territorial reorganization because such reorganization is fertile for groups of interested actors to engage, such as the ‘logic of influence’ that Wood et al. (Citation2005, p. 297) identify motivates business relations during territorial restructuring in the UK. Also, during such territorial reorganization, the meaning of the territory being changed is shaped by various forces (Sassen, Citation2013, p. 39). In this Ghanaian case, the political significance of the territorialization processes was not just notable in the local politics of the regions themselves but also connected directly to the bi-polar national politics that made the process a zero-sum and contentious affair. The study identifies some of these various forces, including partisan political forces, ethnopolitical forces and emotional forces of affection from diaspora-based actors.

3. ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK: CLAIMS-MAKING AS A MECHANISM FOR TERRITORIALIZATION

The previous section conceptualized territorialization as a territory-making process through mobilized citizens’ claims and counterclaims. To make this empirically observable, however, it is important to outline the components of the expected mechanism that connects the actions of citizens to the (virtual) expansion or contraction of the territory in focus. This is mainly an analytical question that would be answered with references to other empirical works that also study decentralization from the processual and mechanistic perspectives. Thus, this section outlines the analytical framework used in this study to trace the territorialization process by arguing that, like any political process, territorialization is animated by making claims.

Claims-making in this study is operationalized as ‘political claims-making’, ‘entailing both the formulation of a political demand with a specific content (the claim) and the public staging of this demand (claims-making), giving the term a degree of semantic overlap with social movement core concepts such as framing, collective action, and action repertoires’ (Lindekilde, Citation2013, p. 1). As discussed in the following paragraphs, making claims requires a connection between structural and non-structural factors in society.

Structural factors provide the relevant opportunities and constraints for a mechanism to operate. For instance, Bae (Citation2016, p. 65) studies the decentralization mechanism in Korea and identifies an interaction between the political-economic structural settings and the individual actors (actor-based mechanisms). Heinelt (Citation2019, p. 101) also finds in Latin America that contextual and institutional constraints mediate how effective actor-based mechanisms are in yielding a peaceful resolution of territorial disputes over indigenous land. In effect, structural factors present what may be considered ‘situational mechanisms’ within which other non-structural factors operate (Hedström & Ylikoski, Citation2010, pp. 52, 59).

Non-structural conditions form a major part of territorialization mechanisms because they animate the process towards the outcome. The literature points to actor-based mechanisms as central to explaining the outcomes of territorial politics. These actor-based mechanisms could manifest in various forms. In a process-tracing analysis of sub-national democratization in the Philippines, for example, van Mierlo (Citation2021, p. 2) identifies a ‘four-part attrition mechanism’ hinged on the agency of civil society organizations. Heinelt (Citation2019, p. 95) identifies ‘regular interaction’ and the strategic use of actors’ resources as connecting mechanisms to peacefully manage such territorial conflicts in Latin America. Nelson (Citation2021, p. 7) also identifies three mechanisms through which cross-border regional actors influence the success of secessionist movements. These include resource support, diplomatic support and shaping the influence of foreign powers.

Actor-based mechanisms also include the nature of the material objectives at stake. In the Philippines, van Mierlo (Citation2021, p. 6) shows through process tracing that the civil society organizations’ desire to dislodge a perceived power imbalance at the sub-national level ‘using political opportunity structures’ was essential for the achievement of sub-national democratization. In armed territorial conflicts in Sri Lanka, Holtermann (Citation2019, p. 216) identifies the ‘logic of diversion’ as the primary motivation for rebels to use violence. Thus, rebels use violence to push government forces to expend resources away from rebel territory, an objective that is usually non-obvious to casual observers.

Actor-based mechanisms depend on the resources available and the cost of using them. For instance, Bae (Citation2016, pp. 75–79) identifies influential elites as ‘political gridlocks’ who diffused the idea of decentralization to make it successful in Korea. In doing this, political actors sometimes shelved their opposition to decentralization and allowed it to happen to avoid political backlash. Where the influence of local actors may not be decisive, the expansion in the number of actors over time could also be important in the mechanism. For instance, van Mierlo (Citation2021) notes that the mechanism for subnational democratization in the Philippines included local civil society organizations forming alliances with other political actors with coinciding interests. It is, therefore, apparent that actor mechanisms are important non-structural conditions contributing to the effectiveness of mechanisms of territorialization.

Using a referendum in this Ghanaian process of region separation presents political elites with the opportunity to be central actors in claims-making, driving the territorialization process. As Tierney (Citation2012, Chapter 4) argues, the technocratic nature of referendums means that there is an opportunity for elites to control and steer the process to achieve their objectives. In addition, elites play an important role in framing the issues during social resistance (Kaufman, Citation2011) and mobilizing the support of other citizens for the claims. To analyse mobilization, this study adopts Miodownik and Cartrite’s (Citation2010, p. 732) definition of mobilization in the context of decentralization as ‘ethnopolitical movements seek[ing] and hop[ing] to gain public support for their goals by appealing to and nurturing group identification and erecting politicising boundaries’.

To summarize this conceptual section, this study seeks to show how claim and counterclaim making during region separation in Ghana illustrates territorialization. This section has argued that territorialization is a product of citizens’ mobilizations through claims-making in reference to matters concerning territory and that these mobilizations could transcend the geographical boundaries of the territory in question. Analysing how territorialization unfolds will mean identifying which and how structural and non-structural factors in the case being studied connect during the claim-making process. Thus (as seen in ), territorialization is composed of a series of (counter) claims in relation to a territory-related issue. The claims may halt, but the territorialization initiated by those (counter) claims persists until another claim re-enforces them. As claims re-enforce each other, the magnitude and relevance of the issues in contention grow. The rest of the article will present the empirical evidence of this conceptualization, using the case of region separation resistance in Ghana. The next section will outline the methodology, followed by a profile of Ghana’s regional architecture to clarify the context of the analysis. This is then followed by a three-dimensional analysis of the evidence of territorialization.

Figure 1. Conceptualizing territorialization as a compounding series of claims-making over territorial matters.

4. METHODOLOGY

4.1. Analytical approach

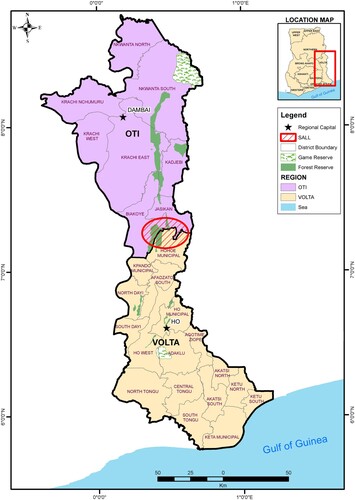

This study applies a Process Tracing (PT) analysis of a typical case of contentious region separation. The chosen analytical technique is based on the general guidelines by Blatter and Haverland (Citation2014, pp. 115–120), where comprehensive storylines describing the most important milestones are used to illustrate the phenomenon of interest, in this case, territorialization. Such an approach is relevant because the research question is to understand territory-making as a spatial process. The analysis, however, does not make any outcome-dependent causal evaluation of the mechanism as performed in some process tracing analyses. The case chosen for the empirical analysis is a typical case of contentious region separation, i.e., the separation of the Volta Region to create the Oti Region (see region map in ). This case was selected because it presented the most talking points regarding the contentions being analysed and therefore presented rich material for illustrating the conceptual arguments advanced in this study. This approach is consistent with case-study analysis, where a typical case expected to fulfil the phenomenon under study is chosen for the analysis (Gerring, Citation2007, pp. 91–97).

Figure 2. Map showing the division of the Volta Region to create the Oti Region. Red shaded area shows the Hohoe municipality that was divided along the Ewe and Guan communities into different regions.

Source: Author solicited Map from CERSGIS, University of Ghana

4.2. Data sources

The analysis in this paper is based on a desk review of secondary data sources, as well as interviews and (archived) documents obtained during fieldwork in Ghana between July 2019 and March 2020. There were nine in-depth key informant interviews. These involved two members of the Commission of Inquiry and two officials of the ministry in charge of region creation. Three persons in favour of region separation and two persons opposing it were also interviewed. Key documentary data sources informing the analysis were from (historical) government and non-government reports, statutes, news articles, online news broadcasts, petition documents, and court proceedings.

5. TERRITORIAL ORGANIZATION, REGIONAL ARCHITECTURE AND REGION SEPARATION IN GHANA

After Ghana gained its independence from Britain in 1957, the country was governed with some form of federalism before a ‘defederalization’ process ushered the country into a unitary and centralized presidential system (Penu, Citation2022a, p. 27). The West African country has about 30.8 million people and comprises over 60 ethnicities, none of which enjoys a majority share of the population but with three of them (Akan, Mole-Dagbani and Ewe) combining to make up three-fourths of the population (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2022, p. 30). Under the current constitution adopted in 1992, Ghana runs a presidential system of government, but with half of its ministerial appointments from parliament. The country’s two largest political parties, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC), have alternated at the helm of government since 1992.

Ghana has a mainly three-tiered government structure: central, regional, and district. According to article 255 of Ghana’s 1992 constitution, the regional level of government is governed by a Regional Coordinating Council (RCC). Part eight of the Local Government Act 936 (2016) which regulates local governance in Ghana, stipulates that the regional government is to serve as the coordinator and supervisor of the district level (The Republic of Ghana, Citation2016; Section 188). Though the regional administration sits at the apex of the local governance machinery, it does not have any legislative or financial autonomy, and the President appoints the top leaders of these regional administrations.

Despite this lack of autonomy for the regional government, the politics of regional governance in Ghana can be very contentious. Penu (Citation2022b, p. 587), for instance, finds that creating new regions in Ghana between 2018 and 2020 led to contentious outcomes due to a mixture of ethnopolitical conditions, especially regarding the dominant role of chiefs in Ghana’s subnational politics. Such contentions are fuelled by the benefits a regional government could offer stakeholders. For instance, not only does the RCC receive donations and allocated grants from the central government, but the regional government is also tasked with the approval of bylaws passed by the district assemblies, the monitoring of the operational and financial performance of the district assemblies, and oversight responsibility over education and health facilities on behalf of the central government ministries (The Republic of Ghana, Citation2016; Section 188 & 199). Moreover, the RCC also offers slots for appointing chiefs and politically exposed opinion leaders to important positions within the regional government.

The political benefits and significance of the regional government have motivated various calls since independence from interested groups to have new regions created from existing ones. Ghana had five regions at independence in 1957. Subsequently, these regions were separated to make a total of 10 regions by 1983 (one in 1959, two in 1960, one in 1982, and one in 1983) (Ghana Commission of Inquiry into the creation of New Regions, Citation2018, p. xix). Since then, it was only in 2019 that six more regions were created to make a total of 16. Thus, from independence to date, region separation in Ghana has led to the creation of 11 regions by separating existing ones. Apart from the recent six, none of the other regions was created through a referendum, even though almost all of Ghana’s constitutions required a referendum for region creation (Penu, Citation2022b, p. 574). This was due to a constitutional amendment abolishing the referendum rule in 1959 (Bening, Citation1999, p. 128). It was re-introduced in 1969, but the military regimes of 1982 and 1983 did not apply it (Bening, Citation1999, p. 145). The recent region separations occurred under the current 1992 constitution.

The process of separating regions in Ghana is contained under Chapter 2 Clause 5 of the 1992 constitution of Ghana (The Republic of Ghana, Citation1992). In reference to those provisions, Penu (Citation2022b, pp. 574–575) describes the region separation process as follows. First, citizens submitted petitions to the President to separate some regions. After consulting the council of state on the proposal, the President set up an independent commission of enquiry to look into the merit of the petition. The Commission’s work involved organizing hearings across the country to determine which petitions had merit. The main objective of the hearings was to determine if there was a need and substantial popular demand for the petition. For the petitions that were deemed meritorious, the Commission recommended the areas that should be included in the new region. The Commission also recommended in which areas the referendum was to be held. Based on these recommendations, Ghana’s independent Electoral Commission then organized a referendum for citizens eligible to vote in the designated areas. The question to be answered at the referendum was: ‘Are you in favour of the creation of the new region? YES or NO?’ (Ghana Commission of Inquiry into the creation of New Regions, Citation2018, p. xxvi). According to the 1992 constitution, any such referendum is decided by at least 50% turn-out and at least 80% voting in favour of the proposal to create a new region. When the electoral Commission announced that the threshold was met in all six cases, the President, as required by the constitution, issued constitutional instruments to formally create the new regions. Thus, Ghana’s constitutional framework makes the referendum (if sanctioned by the Commission) the most decisive part of the region separation process, justifying the huge participation and interest it attracts.

As part of the referendum, stakeholders in favour of and against the separation campaigned to achieve their objectives. The process unfolded in mainly two patterns of either conflict or cooperation between actors in the departing region and those in the stump region. The peak of the contentions featured a failed petition brought before Ghana’s supreme court (Penu, Citation2022b). The suit challenged the constitutionality of the referendum arrangements recommended by the Commission of Inquiry (Supreme Court of Ghana, Citation2018; Welsing, Citation2018). In the view of those supporting the suit, a referendum to alter the boundaries of a region needed to be approved by all citizens from both sides of the region and not just the citizens in the area that would form the new region. For those opposing the suit, limiting the referendum to only the areas that would form the new region was in order because it was consistent with the practice of other referendums held in Ghanaian history and also in other parts of the world. As already presented in the introduction and conceptual sections of this paper, the study will focus on the contentions (claims and counterclaims) around the region separation in a typical case of separation resistance (case explained later) to show how that animates territorialization. A typical case of resistance is chosen because it offers more opportunities for observing the claims and counterclaims.

6. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS OF TERRITORIALIZATION DURING REGION SEPARATION IN GHANA

The following paragraphs present a three-dimensional empirical analysis of claims and counterclaims made by some actors (mobilized citizens) during the region separation process in the Volta Region of Ghana and how this illustrates territorialization as conceptualized in this study. The actors will include (1) national partisan political actors, (2) traditional chiefs, and (3) diaspora-based actors. Where necessary, the terms ‘new region’ (for the departing region) and ‘old region’ (for the stump region) are used to differentiate the two sides of the region being separated. This helped with simplicity and clarity.

6.1. National level: political manifesto claims supporting region separation

The territorialization began in the very formative ‘proposal’ stages of the region separation idea when the two main political parties in Ghana set themselves up to claim credit for eventually creating the new regions. It must be noted that following 1983, there have been multiple petitions to create new regions, which were inconclusively processed by previous governments, both by the NPP and NDC (Commission of Inquiry Report, Citation2018, pp. xix). This inertia was in one part due to the expected huge costs of running new regions (Gyampo, Citation2018, p. 14) and in another part due to the negative political ramifications of dividing social groups into separate political units. These political considerations contributed to the territorialization around region separation and are discussed in the empirics presented in the following paragraphs under this section.

The 2017–2018 process to separate the regions can be traced to a 2007 state-organized independence conference presentation by Prof. Kofi Kumado, a renowned law professor in Ghana. Prof. Kumado argued that Ghana should create additional regions to facilitate efficient administration and reduce conflicts between majority and minority ethnic groups in some of the existing regions in the country (Ghana needs ten more regions, Citation2007). It is apparent that the political actors took this idea seriously because following that event, the NDC, the party in government at the time, made the initial political promise to create new regions in the follow-up to the 2012 elections. Later in the run-up to the 2016 elections, the then main opposition party (the NPP) also joined in making similar promises in their manifesto (Commission of Inquiry Report, Citation2018, p. 372, 373). Whilst the NPP promised only the creation of one region, the NDC promised to create five regions (Region Separation Supporter 1, Interview, 2019). As it turned out, the NPP won the 2016 elections and became the government that supervised the creation of the six new regions.

This positioning of the political parties was relevant to set the stage for competition over any credits accrued from granting some sections of the Ghanaian population their regional administration. The positioning is critical because, in Ghana, most processes that lead to splitting political units yield electoral capital for the government that supervised it. For instance, creating new districts has sometimes translated into additional parliamentary seats for the governments that supervised the creation (Ayee, Citation2013; Debrah, Citation2014; Resnick, Citation2017). Also, the creation of the Upper West region in the 1980s improved the electoral performance of the government that supervised it because it led to the creation of more pro-government districts and motivated the citizens there to reward the government for granting their requests (JoyNews, Citation31 Oct, Citation2018, 29–37 min). Also, in northern Ghana, Bob-Milliar (Citation2019) shows how the national policy of political parties influences the political behaviour of citizens at the local level.

Thus, in the separation of the Volta region, the potential electoral ramifications were a critical consideration, even if not openly acknowledged by the political parties, because the historical electoral results (both parliamentary and presidential) show a politically important region. Since the inception of Ghana’s 4th Republic in 1992, the Volta Region has consistently voted heavily in favour of the NDC (in both the new and old parts of the region). Thus, there was a credible threat that the governing NPP stood to gain electoral favours within an opposition stronghold from the population that gets the new region. Indeed, in the Hohoe municipality, which was split to form the new region (see the red shaded area in ), fears of this outcome had motivated the NDC to file various failed legal suits to try and stop the municipality from being split. That was because the party feared this would benefit the NPP as the split would create a more NPP-friendly population in the municipality. Even though the NPP government denied any political motives, the political benefits manifested in the aftermath of the regional separation because the governing NPP won the 2020 parliamentary elections for the first time.

This political contention between Ghana’s two main parties illustrates territorialization because they contained considerations about which actors would ‘gain or lose’ electoral control over the region. Despite the political opposition between the NPP and NDC, both parties were keen to claim credit in the case a new region was created. As indicated, the NPP supported the split for politically obvious but unacknowledged reasons. The NDC openly questioned the propriety of the separation procedure (Nyavor, Citation2018) but strategically offered support for the process during local community interactions. As a region-separation opponent and member of the party in the region explained in an interview, this support was necessary because they noticed it would be politically suicidal to stand against an idea that was becoming popular with the people (Region Separation Opponent 1, Interview, 2019).

Such political considerations are rife in many cases of territorial splits because new political units could translate into gains or losses for political parties. Therefore, political actors fight over credit for such decentralization ideas, as empirically also shown elsewhere. For instance, Bae (Citation2016) identifies in Korea that national elites always want to be seen as the promoters of the ‘idea’ of providing the local population with a decentralized government. The decentralization idea then invariably becomes a contest between the various political interests leading to contestations over the territorial split. Evidence from territorial politics in Spain also indicates that such regionally based concerns about political motives fuel these contentions ‘because where the regional population does not show strong support for the national government, the legitimacy of any national institution is low in those contexts’ (Blanco-González et al., Citation2021, p. 468).

6.2. Regional level: ethnic and secessionist claims over propriety and legitimacy of region separation

From the national level, territorialization continued at the regional level with (counter) claims from regionally based actors about the legitimacy of the region separation. These regionally based actors were mainly traditional chiefs on both sides of the region being separated. Moreover, the role of chiefs as custodians of ethnic interests meant that the claims were ethnically framed as a contest along ethnic lines, in this case, between the Ewe (mainly in the old part of the region) and the Guan (mainly in the new part of the region). The primary role of chiefs in the empirics to be analysed in this section is yet another piece of evidence that affirms chieftaincy as an important institution of governance in Ghana (Sefa-Nyarko, Citation2021, p. 310). Chieftaincy is so important that it serves as one of the main institutions that citizens engage with at the local level in Ghana for service delivery (Fridy & Myers, Citation2019, p. 87).

One of the notable claims was from Togbe Afede, a former member of Ghana’s council of state and paramount chief of the Asogli area in the old part of the region. When the Commission of Inquiry indicated that only the areas to be separated were going to vote in the referendum, Togbe Afede called for ‘fairness’ in the procedure being used (Awal, Citation2018). According to Togbe Afede, fairness required that both the Ewe and Guan parts of the region needed to participate in the referendum because the whole region would be affected, not just part of it. In a counterclaim in response to Togbe Afede’s comments, Elizabeth Ohene, a well-known politician from the NPP who identifies herself with the Ewe and hails from the region, questioned the authority of Togbe Afede to purport to speak for the Ewes. She protested the referral by other Ewe ethnic folks to the Guans as settlers in the region and the lands they inhabit as Eweland (Lartey, Citation2018).

The Joint Consultative Committee (JCC), the official group (of chiefs and other opinion leaders) representing the new region proponents, also disagreed with the resistance advanced by Togbe Afede. To them, they had been the ones who submitted a petition, so they were the only ones to decide the fate of that petition (Go write your own petition, Citation2018). To them, this call for fairness was just a decoy for the leaders and citizens of the old region to stifle the separation agenda and thereby maintain their domination and discrimination over the new region’s citizenry. During interviews, new region supporters alleged that those resisting were doing so because they noticed a new region would end many years of domination that inhabitants of the new region had endured from leaders of the old region. They cited reports of discrimination in business opportunities, distribution of resources and political representation at the national level to back their claim (Region Separation Supporter 2, Interview, 2019: Region Separation Supporter 3, Interview, 2020). Those who opposed the process for the new region also had their own counter-allegations in response to these claims. For instance, one opponent claimed in an interview that the call for a new region was by some ‘selfish chiefs’ aiming to deceive their subjects for personal gain (Region Separation Opponent 2, Interview, 2019).

These claims and counterclaims play an important role in the territorialization process because it raises a controversy over which citizens had the right to decide the separation of the region. For citizens and leaders from the old region area that resisted the separation, the procedure for separation needed to be considered by all (not some) of those who ‘belonged’ to the region (citizens of the region). Some analogies used in these claims even purported that there was a hierarchy of citizens’ rights to decide the matter. As a separation opponent puts it,

it is rather unfortunate that when the government was doing the whole thing, they said some part of Volta region whom ‘they’ feel should not be part of the new region and should not participate in the referendum. If I am a father and I have a son in the house [whom] you feel is grown up, and you want to build a new house for him (sic), why not consult the father and ask permission. (Region Separation Opponent 2, Interview, 2019).

Another example of the ethnocentric frames came up in October 2018, just two months before the referendum. The Council of Anlo Chiefs (a governing body of chiefs ruling in the 36 traditional Anlo (Ewe) areas of the Volta Region) unanimously declared its opposition to the region’s separation. In their dissenting statement, the chiefs stated that they ‘strongly believe that the division of the Volta Region has the potential of resulting in tribal conflicts among the peace-loving people of the Volta Region’ (Fugu, Citation2018). This resistance was followed by other ethnically tinted counters from leaders in the new region. For instance, on the referendum day, the Krachiwura Nana Mprah Besemuna II (The Paramount chief of the Krachi people and the most prominent chief in the Guan population leading the separation petition) charged his subjects to defy the resistance and vote for the new region. He dressed in traditional military regalia and emphatically declared to the press and assembled subjects as follows: ‘This is a day [referendum day] that will make or break us … My message for the people is that they should stand firm … If we don’t take advantage of this system, and everyone gets their region, mind you, we will go back to the old system which has not worked for us … you have seen our roads, is it the same in Kpando, Tovie, Anfoega, Vakpo … even go to Anloga’ (JoyNews, Citation27 Dec, Citation2018, 0–0:30 min; 2:14–3:08 min). Considering that all these areas referred to by the Krachiwura were ethnic Ewe-dominated areas, it was apparent that the paramount chief was rallying his subjects to perform their duty as ethnic citizens of the Guan area, to defy the Ewe opposition, and vote at the referendum in support of the new region.

The claims and counterclaims also involved secessionist rhetoric within the region. This secessionist rhetoric was led by a group called the Homeland Study Group Foundation (HSGF) (Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization, Citation2018). Though not publicly supported by any significant Ewe leadership in Ghana, the group is known for re-stoking a long-standing campaign for the Volta Region to secede from Ghana. The source of that campaign stems from some long-standing claims about an expired colonial project by Britain involving the Ewe ethnic folk (Western Togoland) when Ghana was preparing for independence (Brown, Citation1980). These secessionist claims were countered by one of the chiefs from the Guan areas, Nana Ogyeabour Akompi Finam II, Omanhene of Kadjebi Traditional Area and a former member of Ghana’s Council of State. In an opinion piece written on the subject, the chief debunked what he called ‘misplaced secessionist propaganda’ about Western Togoland (a pre-colonial label for the Volta Region) (Nana Ogyeabour, Citation2018).

6.3. Diaspora level: mobilized citizenship in contention

The territorialization proceeded further beyond the boundaries of Ghana. As the referendum progressed, some new voices entered the controversy, especially close to the referendum. There began calls from Volta Region citizens in the diaspora to resist the separation and preserve Ewe ethnic lands. Some even confronted the President of Ghana at a durbar during his visit to the United States of America, accusing him of plotting to take away the lands of the Ewe people through the separation (Region Separation Supporter 3, Interview, 2020). The foundation of such accusations is connected to the ethnopolitical rationalization inherent in Ghana’s partisan politics. The President hails from the Akan ethnic stock to which the Guans belong. Thus, there was some rhetoric that this was a ploy by an Akan president to take away Ewe’s lands and give them to Akans. Whilst no clear evidence supports such claims, this boundary drawing between ‘your’ and ‘our’ lands within the same region typifies the territorialization argued in this article, especially when such boundary drawing is not taking place in the region but far away in the diaspora.

Further, new region supporters also claimed that the resistance from the old region was being used as an opportunity by some leaders there to solicit money from the diaspora to fight what they call ‘war in the region’ (Region Separation Supporter 3, Interview, 2020). The diaspora mobilization also featured statements from organized groups sympathetic to the struggle against the region’s separation. For instance, a diaspora-based group, the ‘One Volta Group’, with membership in the USA, UK, Canada and Ghana, issued a statement in December 2018, notifying that they ‘will leave no stone unturned in [the] collective resolve to fight this new threat in order to preserve the sanctity, wholeness and unity of the Volta Region’ (Acquah, Citation2018). They supported various lawsuits against the separation, which all failed to stop the region from being separated.

The sources of the diaspora-based contentions being referred to here are located outside the geographical jurisdiction of Ghana. However, as already argued in the conceptual sections of this paper, any nuanced understanding of territory should be able to accommodate such extra-jurisdictional processes (Sassen, Citation2013, p. 23). As the contention travels beyond the specific geographical borders and more actors begin to get involved, they come with varied interests that expand the virtual territory in contention. This widening of actors is also a consistent feature in territorial processes that have been studied within geographical borders (see Bae, Citation2016; van Mierlo, Citation2021). In this Ghanaian case, the expansion in the contested territory was a product of the mobilized citizen performances that went beyond the region to even draw on diaspora-based actors. Thus, the contention drew in citizens who were not domiciled in the region per se but could draw on narratives that connected them to the territorial issues under contention.

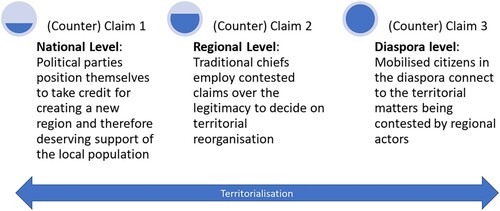

7. SUMMARIZING THE FINDINGS: TERRITORIALIZATION BY CLAIMS-MAKING IN GHANA

To summarize this empirical analysis, the study presents three main highlights of claims and counterclaims made by different types of citizens, which re-enforce each other towards raising resistance to region separation in Ghana and consequently widening the ongoing territorialization. One of these claims relates to the strategies that national political parties adopted in their manifestos to allow them to claim credit for reorganizing the region. Another was the historical connections that regionally based citizens made to contemporary issues to strengthen their claim over territorial matters. The third was the emotional solidarity connections that non-domiciled citizens made with location-based issues during the ongoing territorial dispute. This series of claims and their contributions to territorialization is summarized in .

Figure 3. Summary of some claims-making constituting the territorialization within region separation resistance in Ghana.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The contentions surrounding Ghana’s 2018 referendum to separate some of its regions offer an opportunity for further exploring the concept of territorialization. After advancing a conceptual definition for territorialization, this study analysed three main dimensions in the region separation contentions to show the processual, fluid, virtual, and trans-local perspectives of territory-making. Thus, in agreement with Sassen (Citation2013), this study’s findings emphasize that territorial studies do not need to be fixated on a geographical location. Using Woon’s (Citation2019, p. 115) words, this study places ‘an emphasis on its [territory’s] socially constructed nature,’ … casting ‘attention on how the idea of territory has been mobilized and put into practice’ in the Ghanaian context of region separation. This section will outline the concluding conceptual and theoretical insights from the study findings that enrich our understanding of territorialization and other related concepts.

First, territorialization is essentially territory-making, driven by mobilized citizenship. What animates territory-making is the claims that citizens make about (control over) territorial matters. Conceptually, the study shows how various non-geographical considerations can be roped into understanding such territorialization. The three empirical examples presented by this study include (1) the idea ownership strategies that political parties adopt in their manifestos, (2) the historical connections that location-based citizens make with contemporary issues, and (3) the emotional connections that 'non-domiciled citizens' (Bauder, Citation2014, p. 97) make with location-based matters. Territorialization processes usually result in a consolidation or expansion of the contested (virtual) territory when the territorialization mechanism mobilizes citizens that bring on board different stakes.

As indeed found in this Ghanaian process, mechanisms of territorialization could have expanding dimensions transcending the local, national and international. This finding provides further understanding of the outcomes of other forms of separatist politics. First, just as Nelson (Citation2021, p. 13) finds in the case of secessions, it shows that the mechanisms underlying the outcomes of territorial splits have similar expanding trajectories irrespective of whether political autonomy is the endpoint. Hence, even if the territorial split does not lead to autonomous political units (as in Ghana), similar expanding trajectories of the contentions can be observed. Such similarity supports the arguments made by Sambanis and Milanovic (Citation2011) that whilst separatist politics may have different levels of political significance (from secessions to administrative divisions), there is nevertheless a fundamental analytical similarity between them.

The findings show indeed that the concept ‘territory’ can be ‘understood as a complex capability with embedded logics of power/empowerment and of claim making’ (Sassen, Citation2013, p. 21). During a territorial struggle, the geographical territory may remain intact, but the ethnopolitical solidarity formation can quickly expand the ‘virtual’ size of the territory in contention. In this Ghanaian case, the notion of what territory was being threatened evolved as more and more citizens got mobilized into the contention. It is precisely the expansion of these virtual territorial concerns that differentiates contentious territorial splits from non-contentious ones.

The findings also contribute to understanding the connection between the colonial legacy and its impact on subnational territorialization in Africa. Such implications of colonialism in sub-national territorialization have also been noted in South Africa’s provincial reorganization (Mavungu, Citation2016, p. 198; Narsiah, Citation2019, p. 411). Understanding this connection is relevant not only because sub-national borders in Africa are usually a colonial creation (Ramutsindela Citation2019, p. 350) but also because the rules for altering them can be colonial relics that breed contention. In this Ghanaian case, colonial administration and the decolonization processes gave Ghana a quasi-federal beginning which is the main reason Ghana uses a referendum for region separation (Penu, Citation2022a, pp. 35–36). It is this elaborate referendum process that offered the opportunity to resurrect grievances against perceived colonial injustices, as illustrated in the secessionist content of the region separation resistance.

Finally, this study recommends that attempts to rectify the ‘neglect’ of a ‘conceptual analysis’ of territory (Elden, Citation2010, p. 801) can be helped by focusing on more virtual dimensions of border-making or territory-making. Since territorial matters can be tangible and intangible (Hensel & Mitchell, Citation2005), significant attention must be paid to the intangible aspects of territory and territory-making. Claims made during contentions over territorial matters may not necessarily lead to a change in the geographical space of the territory. Therefore, as done in this study, it is essential to explore analytical innovations that allow political and human geographers to consider the intangible aspects of territories. Although this study’s analysis of territorialization is limited in relation to tangible matters, it nevertheless draws attention to other important aspects of the concept, such as the sources and motivations for territorial contention, even where there seems to be nothing tangible at stake. Many more such studies would help broaden the field of territorial studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the interview respondents for their time and input towards this research. The author received consent from interviewees to draw upon interviews for this study. The interviewees are not responsible for any of the paper’s content, which is the sole responsibility of the author.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Acquah, P. (2018, 11 December). Group demands transparent referendum in oti region. Daily Graphic. https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/ghana-news-group-demands-transparent-referendum-in-oti-region.html.

- Agnew, J. (1994). The territorial trap: The geographical assumptions of international relations theory. Review of International Political Economy, 1(1), 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692299408434268

- Awal, M. (2018, 18 January). Be fair in creation of new regions – Afede to brobbey c’ssion. Starrfmonline. https://starrfm.com.gh/2018/01/fair-creation-new-regions-afede-brobbey-cssion/.

- Ayee, J. R. A. (2013). The political economy of the creation of districts in Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 48(5), 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909612464334

- Bae, Y. (2016). Ideas, interests and practical authority in reform politics: Decentralisation reform in South Korea in the 2000s. Asian Journal of Political Science, 24(1), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185377.2015.1120678

- Bauder, H. (2014). Domicile citizenship, human mobility and territoriality. Progress in Human Geography, 38(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513502281

- Bening, R. B. (1999). Ghana: Regional boundaries and national integration. Ghana University Press.

- Blanco-González, A., Miotto, G., & Díez-Martín, F. (2021). Politics and regionality: Does region of residence affect the state’s legitimacy? American Behavioral Scientist, 65(3), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220975048

- Blatter, J., & Haverland, M. (2014). Designing case studies: Explanatory approaches in small-N research. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bob-Milliar, G. M. (2019). Place and party organizations: Party activism inside party-branded sheds at the grassroots in northern Ghana. Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(4), 474–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1503091

- Brighenti, A. M. (2010). Lines, barred lines. Movement, territory and the law. International Journal of Law in Context, 6(3), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552310000121

- Brown, D. (1980). Borderline politics in Ghana: The national liberation movement of western togoland. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 18(4), 575–609. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00014750

- Debrah, E. (2014). The politics of decentralisation in Ghana’s fourth republic. African Studies Review, 57(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2014.5

- Desforges, L., Jones, R., & Woods, M. (2005). New geographies of citizenship. Citizenship Studies, 9(5), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020500301213

- Elden, S. (2010). Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography, 34(6), 799–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510362603

- Fridy, K. S., & Myers, W. M. (2019). Challenges to decentralisation in Ghana: Where do citizens seek assistance? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 57(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2018.1514217

- Fugu, M. (2018, October 17). New regions face dissent. Graphic Online. Retrieved from https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/new-regions-face-dissent.html.

- Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge University Press.

- Ghana Commission of Inquiry into the creation of New Regions. (2018). Report of the commission of inquiry into the creation of new regions. The Ministry of Information, Ghana. https://media.peacefmonline.com/docs/201812/762942613_800218.pdf.

- Ghana needs 10 more regions – Prof. Kumado. (2007, 31 March). Daily graphic. https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/ghana-needs-10-more-regions-prof-kumado.html

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2022). Ghana 2021 population and housing census.

- Giddens, A. (1987). The nation-state and violence: Volume two of a contemporary critique of historical materialism. University of California Press.

- Gottmann, J. (1975). The evolution of the concept of territory. Social Science Information, 14(3), 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847501400302

- Go write your own petition – pro-oti region chiefs tell disgruntled south volta. (2018, 20 January). Myjoyonline. Retrieved from: https://www.myjoyonline.com/go-write-your-own-petition-pro-oti-region-chiefs-tell-disgruntled-south-volta/.

- Gustafsson, M. T., & Scurrah, M. (2020). Subnational governance strategies at the extractive frontier: Collaboration and conflict in Peru. Territory, Politics, Governance, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1840425

- Gyampo, R. (2018). Creating new regions in Ghana: Populist or rational pathway to development? Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 15(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v15i2.1

- Hedström, P., & Ylikoski, P. (2010). Causal mechanisms in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102632

- Heinelt, M. (2019). How to face the “fight of an ant against a giant”? Mobilisation capacity and strategic bargaining in local ethnic conflicts in Latin America. Zeitschrift Für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 13(1), 93–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-019-00417-5

- Hensel, P. R., & Mitchell, S. M. (2005). Issue indivisibility and territorial claims. GeoJournal, 64(4), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-005-5803-3

- Holtermann, H. (2019). Diversionary rebel violence in territorial civil war. International Studies Quarterly, 63(2), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz007

- JoyNews. (2018, 27 December). Krachiwura urges all residents to come out and vote. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JEpBRdmxEgw.

- JoyNews. (2018, 31 October). One on one with Dr.Obed Asamoah – UPfront on JoyNews. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OPpSMiP-4E0.

- Kaufman, S. J. (2011). Symbols, frames, and violence: Studying ethnic war in the Philippines. International Studies Quarterly, 55(4), 937–958. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00689.x

- Kenny, M. (2022). Governance, politics and political economy–England’s questions after brexit. Territory, Politics, Governance, 10(5), 678–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1962732

- Lartey, L. N. (2018, 2 November). Elizabeth Ohene asks: Who speaks for the Ewes? CitiNewsroom. https://citinewsroom.com/2018/11/elizabeth-ohene-asks-who-speaks-for-the-ewes/.

- Lindekilde, L. (2013). Claims-making. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements.

- Mavungu, E. M. (2016). Frontiers of power and prosperity: Explaining provincial boundary disputes in postapartheid South Africa. African Studies Review, 59(2), 183–208. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2016.28

- Miodownik, D., & Cartrite, B. (2010). Does political decentralisation exacerbate or ameliorate ethno-political mobilisation? A test of contesting propositions. Political Research Quarterly, 63(4), 731–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912909338462

- Nana Ogyeabour, A. F. II (2018, 13 April). Oti region: History, facts vs secessionist propaganda – thoughts of a chief. Ghanaweb. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/features/Proposed-Oti-Region-History-facts-vs-secessionist-propaganda-thoughts-of-a-chief-642813

- Narsiah, S. (2019). The politics of boundaries in South Africa: The case of matatiele. South African Geographical Journal, 101(3), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2019.1601591

- Nelson, E. (2021). A successful secession: What does it take to secede? Territory, Politics, Governance, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1899974

- Nyavor, G. (2018, 29 October). “Unconstitutional!”: NDC barks at gov’t over demarcation of regions. Lorlonyo FM. http://www.lorlornyofm.com/unconstitutional-ndc-barks-at-govt-over-demarcation-of-regions/.

- Öjehag-Pettersson, A. (2020). Measuring innovation space: Numerical devices as governmental technologies. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(5), 621–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1601594

- Penu, D. A. K. (2022a). Explaining defederalization in Ghana. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 52(1), 26–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab035

- Penu, D. A. K. (2022b). Explaining region creation conflicts in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 60(4), 571–595. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X22000374

- Ramutsindela, M. (2019). Placing subnational borders in border studies. South African Geographical Journal, 101(3), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2019.1651101

- Resnick, D. (2017). Democracy, decentralisation, and district proliferation: The case of Ghana. Political Geography, 59, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.02.011

- Sack, R. D. (1986). Human territoriality: Its theory and history. Cambridge University Press.

- Sambanis, N., & Milanovic, B. (2011). Explaining the demand for sovereignty. The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (5888).

- Sassen, S. (2013). When territory deborders territoriality. Territory, Politics, Governance, 1(1), 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2013.769895

- Sefa-Nyarko, C. (2021). Ethnicity in electoral politics in Ghana: Colonial legacies and the constitution as determinants. Critical Sociology, 47(2), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520943263

- Spinney, J., Aldred, R., & Brown, K. (2015). Geographies of citizenship and everyday (im)mobility. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 64, 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.04.013

- Supreme Court of Ghana. (2018). In the case of Mayor Agbleze, Destiny Awlime and Jean-Claude Koku Amenyaglo vs Attorney General and Electoral Commission, Supreme Court Registry of Ghana.

- The Republic of Ghana. (1992). Constitution of the Republic of Ghana. http://www.ghana.gov.gh/images/documents/constitution_ghana.pdf.

- The Republic of Ghana. (2016). Local governance act 936, registry of the parliament of the Republic of Ghana, Accra, Ghana. http://rhody.crc.uri.edu/gfa/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2018/04/Ghana-Local-Governance-Act-of-2016-No.-936.pdf.

- Tierney, S. (2012). Constitutional referendums: The theory and practice of republican deliberation (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. G. (2015). Contentious politics (Second revised edition. ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. (2018). Western Togoland: HSGF reaffirms independence claims. https://unpo.org/article/21040.

- van Mierlo, T. (2021). Attrition as a bottom-up pathway to subnational democratisation. International Political Science Review, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/01925121211019269

- Welsing, K. ((2018, 28 November). New regions: Supreme court throws out constitutionality suit. Starrfmonline. https://starrfm.com.gh/2018/11/new-regions-supreme-court-throws-out-constitutionality-suit/.

- Wood, A., Valler, D., Phelps, N., Raco, M., & Shirlow, P. (2005). Devolution and the political representation of business interests in the UK. Political Geography, 24(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.09.018

- Woon, C. Y. (2019). Translating territory, politics and governance. Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1597558

- Zimmerer, K. S. (2015). Environmental governance through “speaking like an indigenous state” and respatializing resources: Ethical livelihood concepts in Bolivia as versatility or verisimilitude? Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 64, 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.07.004