ABSTRACT

Recent work on secession foregrounds the loss of autonomy in explaining support for independence. These theories imply that objective institutional shifts possess inherent meaning for the relevant political actors. In this article we propose that the meaning of institutional change must be actively constructed and cannot be read off the ‘objective’ characteristics of institutional change. Our analysis of secessionist mobilisation in Catalonia (Spain) between 2003 and 2017 specifies two mechanisms which we argue are necessary in order for institutional change to increase support for secession. First, an institutional shift must be framed as a loss. Second, this loss must be perceived as meriting secession. Thus, institutional change ought to be viewed not as an experience-distant objective phenomenon, but an experience-near social fact.

1. INTRODUCTION

Territorial autonomy features prominently in explanatory theories of secessionist mobilisation. Initially, these theories focused on the mere presence or absence of autonomy arrangements. More recent contributions show how change in existing institutions shapes the ability of secessionist movements to mobilise support. These theories – to which we refer as lost autonomy theories of secession in the interest of conciseness – assert that support for secession is driven by the loss of institutional advantage, rather than its presence or absence. Autonomy arrangements protect the interests of potentially vulnerable populations and express their collective identities. Enfeebling those institutions thus threatens both the material and ontological security of those communities and fosters support for independence.

This plausible logic rests on problematic assumptions. The first is that the meaning of institutional change is readily apparent to members of a community profiting from existing autonomy arrangements. The second assumption suggests a direct and unmediated link between the loss of institutional advantage and support for independence. The methodological implication is that testing the link between institutional change and support for secession requires assessing objective shifts in autonomy and then observing the behaviour of the relevant populations. In this article we challenge these assumptions, not because we believe that institutional change is irrelevant to outcomes of self-determination struggles, but because we think that existing theories need to be placed on stronger conceptual foundations.

In line with interpretivist approaches to politics, we argue that institutional change is not an ‘experience-distant’ concept (Schaffer, Citation2016, pp. 2–4). Its causal efficacy cannot stem from its objective characteristics, but rather from the meaning it comes to assume among the relevant publics. We extend this insight by developing two causal mechanisms that we suggest might be necessary if institutional change is to animate support for independence. First, any change must be interpreted as constituting a loss for the community in question, and second, that loss must be perceived as sufficiently grave to merit secession. Neither outcome is an automatic result of the objective characteristics of that change. Rather, they are the intended and unintended product of political and discursive struggles.

We build our case by analysing secessionist mobilisation in Catalonia between 2003 and 2017. This period featured three key moments of institutional change: the implementation of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy; the 2010 verdict of the Spanish Constitutional Court on the same Statute; and the 2017 suspension of Catalonia’s autonomy (the first arguably expanding and the latter two reducing the region’s self-government). The expansion of autonomy was accompanied by growth of secessionist support, contradicting the implicit expectation of lost autonomy theories of secession. The two episodes of autonomy contraction failed to produce a major increase in support for independence, against the explicit expectations of lost autonomy theories of secession. The Catalan process thus provides us with three crucial most likely (disconfirming) case studies (Gerring, Citation2007) that show institutional change as such does not have a linear influence on support for secession. These cases do not constitute definitive repudiation of extant theories, but serve as a motive to re-examine their conceptual assumptions and develop new hypotheses to be tested in future work.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. The next section outlines the core assumptions behind the lost autonomy theories of secession and suggests why they deserve to be reconsidered. We then outline our theoretical framework, foregrounding lost autonomy as a social fact and outlining a set of causal mechanisms emerging from that understanding of institutional change. The following section explains our methodological approach, emphasising the hypothesis-generating purpose of the article. The bulk of the paper offers integrated narratives of the three episodes of institutional change in Catalonia, with each segment disconfirming the expectations of the lost autonomy theories of secession, and pointing to the plausibility of the causal mechanisms we develop here. The concluding section outlines areas for future research.

2. THE LOST AUTONOMY THEORIES OF SECESSION: A REVIEW

Institutional analysis occupies an important place in the study of conflict in multinational states (McGarry et al., Citation2008). One school argues that institutionalising diversity offers the best hope for preserving the stability and democratic character of multinational polities. Populations mobilised behind discrete national projects may accept the common state only if they are guaranteed institutional recognition and protection of their political, cultural, and economic interests (Cederman et al., Citation2015; Lijphart, Citation1977). For others, accommodative institutions entrench otherwise fluid identities; incentivise conflict-seeking behaviour; and equip secessionists with institutional tools needed to accomplish their goals (Jenne, Citation2009; Roeder, Citation2007).

This debate revolved around a static view of institutions, with the mere presence or absence of a particular arrangement explaining divergent outcomes. More recent works have turned to institutional dynamics, arguing that change in autonomy arrangements bolsters support for independence. These authors foreground loss of autonomy as the key factor explaining the rise of support for secession. For Ahram, separatism emerges where people ‘had held and then lost political autonomy’ (Ahram, Citation2020, p. 118, emphasis added). For Cederman et al., separatist rebellion is more likely among ‘groups that have recently had their autonomous status revoked’ (Cederman et al., Citation2015, p. 260, emphasis added). Germann and Sambanis show that ‘autonomy loss’ correlates with the ‘emergence of nonviolent separatist claims’ (Germann & Sambanis, Citation2020, p. 180). Siroky and Cuffe demonstrate that communities that ‘have recently lost autonomy’ are ‘more likely to engage in separatism’ (Siroky & Cuffe, Citation2015, p. 5). Sorens (Citation2012, p. 62) shows that the history of ‘lost autonomy’ fosters secessionism, as does Walter, for whom ‘groups that had once enjoyed political autonomy but had lost it’ were particularly likely to pursue secession (Walter, Citation2009, p. 113, emphasis added). Our choice to categorise these contributions as lost autonomy theories of secession is thus based on the language and logic of the contributors themselves.

Most of these contributions draw on similar data, using either the Minorities at Risk (MAR) (Sorens) or the Ethnic Power Relations (EPR) (Cederman et al., Citation2015; Germann & Sambanis, Citation2020) datasets, or some combination of the two (Siroky & Cuffe, Citation2015). Both the MAR and EPR datasets rest on the implicit assumption that the expert coders’ perception of an institutional configuration and its change (the level of autonomy or access to power a ‘group’ has) is shared by the relevant political actors. In MAR dataset, the ‘lost autonomy’ variable is a composite of factors such as previous autonomy and magnitude of the loss. Previous autonomy status includes categories such as the lack of autonomy, non-institutionalised autonomy, institutionalised autonomy and prior statehood.Footnote1 For ‘magnitude of change’, coders are expected to assess whether a group experienced ‘no change’, ‘transfer only centralised autonomy’ and, finally, either loss of short (under 10 years) or long-term autonomy. The implicit assumption is that the loss of autonomy as assessed by expert coders is perceived in the same way by individuals on the ground.

The EPR dataset focuses on group access to executive power, distinguishing between groups that dominate the executive, share executive power with other groups, or are excluded from central power altogether. In the last category, some groups have access to autonomy, while others do not (Wimmer et al., Citation2009, appx 3–4). These authors are interested ‘in major power shifts’ rather than day-to-day governance patterns (Wimmer et al., Citation2009, appx 2, emphasis added). As they do not make it clear for whom a shift is thought to be ‘major’, it is reasonable to conclude that they assume that the coder assessment of a significant shift in power configurations is understood similarly by the relevant actors.

These conceptual assumptions and their theoretical and methodological implications can be summarised as follows. An objective decline in institutional status for a particular group, as assessed by experts, is highly likely to be perceived as a downgrade by leaders and members of that group (conceptual–epistemological assumption). This change engenders grievances that increase the support for rebellion or secession among the group’s population and leadership (theoretical implication). Scholars seeking to understand the sources of that support should look at the objective shifts in access to power/autonomy for the group in question, which should suggest whether or not secessionist outcomes are likely (methodological implication).

All three premises are problematic. A particular episode of institutional change may, but need not, be seen as a loss by the relevant actors. A shift in autonomy or access to central power does not come with ready-made meaning. Rather, that meaning is socially constructed, fragmented and changing. These features should make us careful about the theoretical and methodological expectations we place on the objective characteristics of institutional change. Measuring objective changes in autonomy and assuming they will produce a particular set of outcomes is thus theoretically and methodologically unwarranted.

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: LOST AUTONOMY AS A SOCIAL FACT

The primary task of this article is not to test causal hypotheses about the link between institutional change and support for secession. Rather, it is to provide an empirically rooted and systematic conceptual analysis of institutional change so that the concept can be placed on firmer theoretical ground. We find this to be necessary because none of the contributors to the lost autonomy theories of secession we cite have done so. This is not unusual. John Gerring shows that political scientists tend to privilege causal analysis over careful conceptualisation, a trend he argues is detrimental to our ability to understand the social world (Gerring, Citation2012). Without sufficient attention to conceptual development, causal analysis – however methodologically sophisticated – may yield flawed findings (p. 738). Gerring therefore urges political scientists to rededicate themselves to the seemingly ‘descriptive’ task of conceptualisation.

This article accepts Gerring’s challenge. Against objectivised understanding prevailing in lost autonomy theories of secession, we reconceptualise institutional change – and the loss of autonomy as one variant thereof – as a social fact. Mainstream political science often proceeds from the assumption that we can define, operationalise, and measure social facts without reference to how the individuals experiencing those facts understand them (Schaffer, Citation2016 , p. 10). In the context of lost autonomy theories, this means that we can assess change in autonomy without interrogating how the actors experiencing that change view their institutional reality. Researchers can observe objective changes in political rules, make their own judgments about the meaning of those changes, and assume their interpretation will mirror how they are perceived by the relevant actors.

In contrast to this (neo)positivist view, interpretivist scholars argue that social reality does not exist independently of those being researched (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, Citation2011, p. 41). Indeed, social facts are constituted by the way in which the relevant actors perceive them. This insight extends to institutions, since ‘beliefs about social institutions are partially constitutive of social institutions, [making] it impossible to identify the institution except in terms of the beliefs of those who engage in its practices’ (MacIntyre, Citation1972, p. 12). Thus, it is the meaning that social actors invest in particular political phenomena, rather than any objectivised feature of such phenomena, that makes them politically and causally relevant (Bevir & Kedar, Citation2008, p. 511). It follows that if scholars ignore actors’ intersubjective understanding of institutions, they risk ‘attributing unwittingly [and potentially erroneously] to the people being studied the worldview of the researcher’ (Schaffer, Citation2016, p. 7).

We extend these interpretivist insights by developing a social conceptualisation of institutional change. The causal efficacy of the loss of autonomy, or any other form of institutional change, hinges not on its objectivised features (e.g., the degree or direction of change as assessed by experts) but rather on the meaning that it comes to assume among the relevant social actors. This understanding aligns with, and builds upon, recent work on institutional dynamics in multinational states. For instance, Lecours shows that it is not the loss of autonomy but the inflexibility of central governments in the face of evolving demands for greater autonomy that leads to support for secession (Lecours, Citation2021). Importantly, Lecours suggests that subjective perceptions might be more important than objective ‘realities’ of autonomy (p. 188). Basta argues that the reversal of symbolic concessions to minority nations leads to secessionist crises (Basta, Citation2021). His emphasis on the meaning of autonomy over its instrumental function resonates with the interpretivist understanding of institutional change we develop here.

The conceptualisation of institutional change as a social fact generates two causal mechanisms that we argue are jointly necessary in order for that change to broaden support for secession. First, such change must be perceived as a political loss by a sufficiently broad segment of the particular political community. This does not follow automatically from any given episode of institutional change, both due to the polysemic character of such change and the heterogeneity of the communities it affects. A modification in institutional arrangements – a constitutional amendment or a piece of legislation – is open to multiple interpretations. Institutional change is frequently complex and opaque. Multilevel systems can feature simultaneous centralisation and decentralisation (Broschek, Citation2015). In addition, enhanced policymaking responsibility may reduce a regional government’s manoeuvring room (Falleti, Citation2005). Such complexity makes it difficult for citizens to assign responsibility to the correct level of government (Wlezien & Soroka, Citation2011).

This openness to interpretation is amplified by the internal heterogeneity of national communities (Lluch, Citation2014). Internal ideological divisions rooted in these understandings can be as destabilising as inter-group rivalries, as literature on intra-group outbidding shows (Chandra, Citation2005; Rabushka & Shepsle, Citation1972). Consequently, different segments of any community may interpret identical institutional shifts in different ways. Radicals might see those shifts as unambiguously negative, where moderates might view them as acceptable. Both reasons should caution against reading too much into what the scholars believe to be a ‘loss’ of autonomy. Whether institutional revision constitutes a causally relevant ‘loss’ depends less on expert coders’ interpretation, and more on whether it has been framed and accepted as such by political actors on the ground.

Second, even if a community reaches consensus that a change does constitute a political loss, that loss needs to be successfully framed as being sufficiently grave to merit independence. Secession is a radical political act. It is potentially costly for the seceding population, since it may incur economic costs (Reynaerts & Vanschoonbeek, Citation2022) and instigate violence (Cunningham et al., Citation2019). It is risky because the preference of United Nations member states for the territorial status quo makes the likelihood of international recognition low (Coggins, Citation2011). Even if we bracket these considerations, the divisions within the potentially seceding community can influence the evaluation of the appropriate reaction to a ‘loss’. While some may interpret a given change as meriting a radical break, others may believe that its consequences are remediable.

In addition to the two mechanisms directly linked to institutional change, we add an auxiliary causal mechanism. Even if most members of the potentially seceding community agree that a particular institutional revision represents a loss, and that this loss is sufficiently grave to merit secession, this still may not amount to a change in position unless a sufficient segment of the target population believes that secession is attainable. Social psychologists suggest that grievance must be accompanied by a sense of efficacy in order to facilitate mobilisation (van Zomeren et al., Citation2004). These are not definitive claims – the validity of the mechanisms we outline here must be tested against empirical evidence. Rather, we aim to engage in an empirically rooted conceptual study in the interest of providing a stronger conceptual foundation for the lost autonomy theories of secession, and to leverage that study in order to develop, rather than test, hypotheses about the relationship between institutional change and support for independence.

4. METHODOLOGY: CRUCIAL CASE STUDIES AND PROCESS-TRACING

Our methodological approach combines hypothesis-testing case study method with the hypothesis-generating process-tracing approach. We test the (implicit) assumptions of the lost autonomy theories of secession against three instances of institutional change in Catalonia. In every case the theory’s expectations are disconfirmed. We then engage in process-tracing of the three episodes in order to improve the conceptual understanding of institutional change and to generate new hypotheses about the causal mechanisms that might be necessary if institutional change is to influence support for independence.

In order to test the assumptions about institutional change underpinning the lost autonomy theories of secession, we use the most likely (disconfirming) crucial case method. A most-likely case possesses attributes that make it very likely to confirm a theory, but its outcomes end up contradicting theoretical expectations (Gerring, Citation2007, p. 232; Levy, Citation2008, p. 12). Recent Catalan history provides three highly visible episodes of institutional change, each of which could plausibly have been expected to confirm the lost autonomy theories: the passing of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy; the 2010 Constitutional Court Decision on the constitutionality of said Statute; and the 2017 suspension of Catalonia’s autonomy in response to the unilateral push for independence.

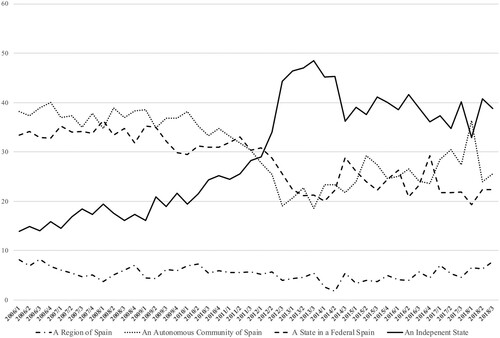

The 2006 Statute arguably enhanced Catalonia’s autonomy relative to the previous period. Among other changes, the new document sought to prevent central government encroachments on Catalonia’s autonomy by detailing the scope of the regional authorities’ competencies. The 2006 StatuteFootnote2 thus contained 223 articles against only 57 in the 1979 version.Footnote3 In addition, during this time period Catalonia and Spain exhibited characteristics that should not have led to growing support for secession: a high democratic score; a comparatively high degree of autonomy; the absence of group-based discrimination; and a traditionally weak secessionist movement.Footnote4 Indeed, before 2012, scholars of nationalism did not anticipate Catalan secessionism becoming a significant political force (Lecours, Citation2021, p. 4). Instead of secessionist stagnation, however, the 2006–10 period saw a steady increase in support for independence from 15% to 25% (). We therefore consider this period as contradicting the implicit expectations of lost autonomy theories.

Figure 1. Institutional preferences (%) in Catalonia, 2006–18.

Source: Based on data from the Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (http://ceo.gencat.cat/ca/barometre/?pagina=1).

The 2010 Constitutional Court decision was seen by almost all Catalan political parties – non-secessionists included – as having reduced the scope of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy. The Court’s decision came at the point of increasing support for independence and acute awareness of the constitutional question. The regional election held only five months later thus presented an ideal opportunity for a secessionist breakthrough. However, neither was there a spike in support for independence (it materialised two years later), nor did either of the two main nationalist parties advocate a turn to secession. The only openly secessionist political option failed to make significant gains.

The 2017 suspension of Catalonia’s autonomy, following the unilateral attempt at independence, could also have resulted in an increase in support for secession but did not. The Spanish government’s suspension of autonomy was exceptional as it was the first such action since the re-establishment of democracy; a significant segment of the Catalan public was mobilised in favour of independence (as witnessed by massive and recurring rallies); and the suspension of autonomy was accompanied by police violence against civilians and by the arrest or self-exile of several leaders of the independence movement. Still, apart from a temporary blip in opinion polls, support for independence remained steady. We thus consider both the 2010 and 2017 episodes to have disconfirmed the explicit expectations of lost autonomy theories of secession.

These cases do not definitively refute the lost autonomy theories. However, since the outcomes contradict the theories in cases where they should have been much more closely aligned with the expectations, they provide a compelling motive for an alternative reading of the link between institutional change and support for secession. We thus engage in process-tracing of the three episodes of institutional change in order to generate alternative hypotheses concerning that link. As Levy notes, process-tracing is an ideal methodological approach for generating hypotheses, particularly when it comes to specifying causal mechanisms (Levy, Citation2008, pp. 5–6). The mechanisms we derive on the basis of this work do not constitute a definitive statement. Rather, we expect that they will be tested and refined against more robust evidence in the future.

We base our conclusions on the combination of primary documents, interviews with participants, newspaper reports and secondary material. This material is not used in order to provide a representative or definitive interpretation of the events in question. Rather, in constructing a sufficiently plausible narrative of the sequence of events surrounding the three episodes of institutional change, we aim, first, to demonstrate that these episodes did not result in the outcomes one might have expected on the basis of lost autonomy theories, and second, to show that each episode was subject to multiple and conflicting interpretations, helping us develop the mechanisms we outline in the previous section. We rely on scholarly articles to reconstruct the relevant events, supplementing these secondary sources with interviews,Footnote5 official documents (e.g., different versions of the Statute of Autonomy and the relevant legislation), newspaper articles and surveys of public opinion during this time. We rely primarily on newspaper reports to demonstrate how various political actors converged or diverged in their interpretation of the relevant instances of institutional change, again supplementing these with secondary material, interviews, and original documents.

5. THE POLITICAL DYNAMICS OF CATALAN SECESSIONISM

5.1. Historical background

Spain’s system of territorial autonomy places it on the spectrum between a decentralised unitary state and a federal one.Footnote6 Each of its 17 Autonomous Communities (ACs) has a Statute of Autonomy that outlines the scope of authority for the regional institutions within the bounds set by the Spanish constitution. This system, referred to as the State of Autonomies, is distinct from federalism. For instance, instead of establishing a clear division of powers between central and autonomous governments, the Spanish constitution lists matters reserved for the central government and enumerates those powers that ACs may (but do not have to) claim for themselves (Linz, Citation1989, pp. 286–287). It also does not specify the territorial configuration, the number, or the extent of territorial units, instead outlining the procedure according to which they may be established (Colomer, Citation2017, p. 953). The territorial framework was thus initially rather open-ended, leaving ample room for asymmetry among territorial units.

This system was a product of a constitutional compromise during the transition from dictatorship to democracy. The second half of the 1970s was a time not only of negotiated transition to democratic rule, but also of mobilisation in Catalonia and the Basque Country for the restauration of autonomy that those regions enjoyed before the demise of the Second Republic (López, Citation1981, p. 196). While the state-wide political parties agreed on the need for some form of decentralisation, there was no consensus either on the precise content of that decentralisation or on how – or whether – Spain’s national diversity was to be acknowledged. The constitutional compromise emerging from these tensions is evidenced in Article 2 of the 1978 constitution that simultaneously acknowledges Spain’s ‘nationalities and regions’ and foregrounds the ‘indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation’.

The Catalan and Basque leaders aspired to asymmetric autonomy as a way of acknowledging the multinational character of Spain (Linz, Citation1989, p. 272; López, Citation1981, p. 198). However, for a range of reasons, including the competition among state-wide parties, pressure from regional governments in other parts of the country, and the resistance to the idea of a pluri-national Spain, the 1980s and 1990s saw the system of autonomy become increasingly symmetric (Colomer, Citation2017, p. 953; Linz, Citation1989, p. 274; Núñez Seixas, Citation2005). In addition, the central government tended to encroach upon autonomous jurisdictions through a variety of measures (Maiz et al., Citation2010). Both trends, combined with increasing competition among Catalan political parties in the early 2000s, incentivised Catalonia’s political elites to embrace statute reform.

5.2. Stage 1 (2003–09): political process and the support for independence

The reform of Catalonia’s Statute of Autonomy was initiated by the left-wing coalition government composed of the non-separatist Catalan Socialists (Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya – PSC) and eco-socialists (Iniciativa per Catalunya Verds – IC-V), and the nominally separatist Republican Left (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya – ERC). In the 2003 regional election this coalition displaced the autonomist Convergence and Union (Convergència i Unió – CiU) which governed Catalonia since 1980. Statutory reform was, however, also accepted by the CiU and adopted as the centrepiece of its programme in the 2003 regional election (Barrio, Citation2009). The drafting of the new Statute sparked an outbidding contest between the CiU (notably its larger component, the CDC) and the ERC. The two parties competed on radicalism of their statutory proposals (Barrio & Rodríguez-Teruel, Citation2017). Some of the key ideas included the shielding of regional powers from central encroachment, enhanced revenue-raising capacity and the primacy of Catalan language in public administration in Catalonia (Colino, Citation2013). The new Statute was finally approved by the Catalan parliament in September 2005 and, as part of standard legislative procedure, sent for review and ratification to the Spanish legislature.

During this second stage the document was shorn of some of its more far-reaching elements, to the public consternation of the more radical members of the Catalan political elite. Its final version was agreed upon by Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and the CiU, which, despite being in opposition in Catalonia, held veto power over the process. The new Statute was then put to a referendum in Catalonia, where it was approved by fewer than half of the electorate, in part because of the ERC’s opposition.Footnote7 Almost immediately thereafter, the Popular Party (Partido Popular – PP; the official state-wide opposition), along with the Spanish ombudsman and governments of five other ACs, headed by both state-wide parties, challenged the Statute at the Constitutional Court (Requejo & Sanjaume, Citation2015, pp. 119–120). The court took four years to issue a verdict. In the intervening period, the impending court challenge continued fuelling the outbidding dynamic between the ERC and CDC, with both parties converging on the view that a negative decision would represent an unacceptable downgrade in Catalonia’s autonomy (Colomer, Citation2017, pp. 957–958). Each party, however, carefully avoided endorsing secession as a response to any such decision (Basta, Citation2018).

The impact of statutory reform on the support for independence during this time was multifaceted and indirect. First, the development of the Statute, the subsequent court challenge, and the accompanying public debates converted institutional change from a technical procedure to a visible and politicised issue. Second, this process resulted in the formation of numerous independentist associations and entities (e.g., Platform for the Right to Decide, Sovereignty and Progress, Catalan Business Circle), all of which defended the integrity of the original text of the Statute. Between 2006 and 2009, their members held events across the region, arguing for the necessity and feasibility of secession, in part as a response to what they saw as the failure of statutory reform.Footnote8

Third, the political competition sparked by the reform divided the nationalist parties internally. The growing importance of the identity axis impelled factions within the ERC and CDC to push for a more open embrace of independence. Still, between 2006 and 2011/2012, regardless of the approach by successive Spanish governments, parliament and the Constitutional Court to the Statute of Autonomy, the leadership of both parties assiduously avoided adopting secession as an explicit policy goal (Basta, Citation2018). For the more radical members of those two parties, this demonstrated that their goal could not be attained by working through the party system. Some consequently turned to the civil society in order to force the hand of the political parties.

5.3. Stage 1 (2003–09): the emergent meaning of statutory reform

This stage demonstrates the importance of our first causal mechanism – the need to interpret a particular institutional change as a loss before it can motivate support for secession. That interpretation was a consequence of the manner in which statutory reform unfolded, and of conscious efforts by various actors to frame the result of that reform in divergent ways in attempts to politicise or resist the politicisation of national identity axis of political competition (Colomer, Citation2017). The meaning that the 2006 Statute took on at the end of this process had less to do with the legal text (and its implication for the de facto division of power between Catalonia and Spain) than with the drafting process. Statutory reform started with a set of proposals that were more moderate than the document that finally made it out of the Catalan parliament in September 2005. The initial proposal endorsed by the Tripartit did call for a new fiscal deal, but one limited to a broadening of tax revenue and the ability of the newly established Catalan revenue agency to collect only those taxes that accrued to it (‘Acuerdo’, Citation2003, p. 19).

Because of the competition between the CDC and ERC, the initial proposal was scaled up to a more far-reaching scheme. A major addition was a more comprehensive fiscal arrangement that transferred the revenue raising competencies for all taxes collected in Catalonia – including those accruing to the central state – from the central to the regional government. This element, along with several others, was removed by the Spanish legislators.Footnote9 That revision could have been interpreted in at least two ways – either as a regression to what could realistically pass in Madrid given the constitutional and political constraints (a gain relative to the status quo ante), or as a loss of autonomy relative to the expectation of what could have been had as a result of maximalist demands. The CDC opted for the former, arguing in 2006 that the new Statute achieved the greatest level of autonomy in the past three centuries (‘El mayor nivel de autogobierno’, Citation2006). The ERC, by contrast, framed the final document as a loss of institutional influence (‘Ara Toca No’, Citation2006).

The implications of this process for the way in which we understand institutional change are profound. If one were to code the level of fiscal autonomy implied by the initial framework and the 2006 version of the Statute, one might assign the same score to each. However, the path through which the initial proposal passed transformed the meaning of the final version for at least one segment of Catalan population. The notionally equivalent institutional change assumed a very different meaning as signalled by the divergent interpretation by the CiU and ERC.

Moreover, the 2006 Statute became a political asset for secessionist activists not because it was radically different from the 2003 proposal (‘Acuerdo’, Citation2003) on which the Tripartit was based (it was not), but because of the process that led to its passage. As one member of the ERC explained, before the reform, leading figures in the party expected that the Spanish elites would balk at extending far-reaching concessions to Catalonia.Footnote10 This, they hoped, would demonstrate to non-separatist nationalists – then in the majority – that no institutional option short of independence was feasible. As already noted, the outcome of the process was more ambiguous than these actors anticipated. While it did not yield immediate dividends, it paved the way for long term transformation of Catalonia's political landscape.

5.4. Stage 2 (2009–12): political process and the support for independence

The scope of extra-party independentist activism broadened toward the end of 2009. In September, an informal independence referendum was organised in the municipality of Arenys de Munt. Subsequent informal referenda were held in several waves between 2009 and 2011, with participation exceeding 884,000 individuals (Muñoz & Guinjoan, Citation2013). These waves were coordinated in part by independentist dissidents within the ERC and CDC, some of whom became members of the quasi electoral commission for the Arenys de Munt vote (Agència Catalana de Notícies, Citation2009). The primary goal of these referenda was to pressure the CDC and ERC toward endorsing secession by demonstrating the size of the pro-independence block.Footnote11 Another aim was to persuade the Catalan public that independence was feasible as well as necessary.Footnote12

This period did see a rise in support for independent statehood (). The referenda, moreover, accumulated organisational experience that would prove useful in subsequent mobilisation (Medir, Citation2015). Several of the participants in the Arenys de Munt referendum formed a non-partisan organisation the sole purpose of which was the pursuit of independence. Their goal was to make the organisation sufficiently massive to change the political rationale of the nationalist political parties, and to steer them in the direction of independence.Footnote13 By March 2012, their efforts resulted in the foundation of the Catalan National Assembly (ANC) (Barrio, Citation2018).

This mobilisation overlapped imperfectly with the Constitutional Court’s verdict on the constitutionality of the 2006 Statute – the second key episode of institutional change. In June 2010, the court annulled and reinterpreted a number of the Statute’s articles. Changes related, inter alia, to the preferential use of Catalan over Castilian language in public administration and the media; autonomous judiciary; and fiscal competences. As importantly, the judges stipulated that the reference to Catalonia as a nation in the Statute’s preamble had no legal effect, thus reversing the key element of recognition at the core of the statute reform (Requejo & Sanjaume, Citation2015, p. 121). Most Catalan parties considered these changes as an assault on Catalan autonomy. Although statutory reform evoked little popular enthusiasm, the 2010 sentence sparked a massive manifestation under the slogan ‘We are a nation, we decide’ (‘Nosaltres decidim’, Citation2010).

At this point, the dynamics of party politics and civil society mobilisation converged. While the Constitutional Court decision did not cause a major shift in favour of independence, it did contribute to the growth of independentist civil society organisations, notably the surging ANC. The organisation developed a broad territorial reach, with activists leveraging existing social networks to spread the independentist message. The ANC’s mobilisational capability showed in 482 preparatory events held during 2012, in anticipation of the Diada (Catalan national day) demonstration that would take place later that year.Footnote14

The massive 2012 Diada manifestation was a product of the combined efforts of the ANC, Òmnium Cultural and the Association of Municipalities for Independence. After the demonstration, the leaders of the three organisations met with Artur Mas, demanding plebiscitary elections and a referendum on self-determination in 2014. Several days later, Mas met with the Spanish prime minister Rajoy in a last-ditch effort to secure a new fiscal deal for Catalonia (Piñol & Cué, Citation2012). Rajoy refused, prompting Mas to call a snap election and committing to hold a ‘consultation’ on self-determination if elected. It was at this moment that the support for independence registered its high water mark, reaching 44.3% ().Footnote15

The 2012 secessionist shift in Catalan society and party system was thus not a direct consequence of statute reform and the subsequent Constitutional Court decision. Nevertheless, that change, together with its unanticipated consequences and the deliberate framing efforts that accompanied it, was an important indirect contributor. The process of statutory reform preceding the 2009–12 juncture provided the organisational basis for mobilisation of the secessionist civil society during the 2009–12 period (Medir, Citation2015). This mobilisation received additional boost by the 2010 Constitutional Court verdict. Instead of contributing directly to support for independence, the verdict provoked anger that motivated a growing minority of Catalans to advocate for independence through the ANC.Footnote16 The ANC-organised Diada manifestation of 2012, along with the increase in support for secession with which it coincided, shifted the political considerations of the CiU government. When faced with what was taking place both in the streets and in the polls, Artur Mas felt compelled to call a snap election on a pro-independence platform.Footnote17 Once the CDC and ERC committed to the pursuit of independence, they transitioned from a non-secessionist to secessionist outbidding dynamic that eventually led to the unilateral independence bid in 2017 (Colomer, Citation2017, pp. 960–961).

5.5. Stage 2 (2009–12): forging the meaning of the 2010 court decision

The reaction to the 2010 decision of the Spanish Constitutional Court provides further evidence of the tenuous link between objective institutional change and support for independence. While there was overwhelming agreement in Catalonia that the decision represented a reduction in the region’s autonomy, neither the public nor the political parties moved decisively in the direction of independence. In September 2009, in response to a leak about the content of the forthcoming court decision, all major Catalan newspapers published a joint editorial in which they framed that decision as a reduction of Catalonia’s autonomy (‘La Prensa’, Citation2009). When the formal decision finally came in June 2010, it provoked outrage across the Catalan political spectrum, with independentist, autonomist, and federalist parties – together accounting for 87% of the seats in Catalonia’s parliament – interpreting it as a downgrade in Catalonia’s status (Noguer, Citation2010).

Even so, despite consensus about the ‘loss’ of autonomy, and the extended presence of the issue in the public debates, support for independence continued to grow at the same pace as before the court’s decision (). In the regional elections held shortly after the verdict, the main axis of the campaign was the economic crisis (Barrio, Citation2017, p. 45). Neither the victorious CiU nor the ERC advocated a secessionist turn in response to the curtailment of the Statute. The only openly independentist party, Catalan Solidarity for Independence (Solidaritat Catalana per la Independència – SI), obtained 3.3% of the vote.Footnote18 The federalist parties – IC-V and PSC – did not endorse secession for ideological reasons. In addition, an important segment of PSC’s electorate were individuals with close ties to other parts of Spain, thus highly unlikely to back independence. The top brass of the CDC and ERC resisted internal calls for an independentist turn for fear that this might cost them more moderate nationalist votes (Basta, Citation2018, pp. 1258–1259, 1261).

Simultaneously, secessionist civil society organisations pointed to independence as the only viable political response to the Constitutional Court’s decision. For example, during the 2009 Diada, two pro-independence organisations circulated the following message:

The history of Catalanism has … been replete with attempts to … convert Spain into a multinational political space within which Catalans could feel comfortable. The most recent such attempt has been the reform of the Catalan Statute of Autonomy, which will meet its definitive end once the Constitutional Court decides on the appeals presented to it. [That] sentence … will … destroy what little political potential remains of the 2006 Statute, ending the hopes of those who … still believe in the possibility of reforming the Spanish state and leading it toward the recognition of its own plurinationality.Footnote19

The failure of the court decision to sway the Catalan political elites and voters to independentist positions reinforces our argument that the meaning of institutional change is plural and that it shifts over time among different segments of the population. Despite the broad consensus that the 2010 Constitutional Court decision represented a major downgrade in autonomy, various political actors disagreed on the appropriate response to that decision. Secession remained on the political margins. Yet, even if there was agreement on the necessity of secession in response to the court’s decision, this would not have guaranteed agreement on the political feasibility of such a course of action. Secessionist activists believed that a key obstacle to greater support for independence was the lack of confidence among the Catalan population that it was possible. Much of their activism during this period was thus geared towards enhancing the sense of feasibility of independence among the more moderate nationalists. As noted above, the informal referenda of 2009–11 were devised precisely in order foster a sense of efficacy among this part of the electorate. According to one ANC official, the 2012 Diada demonstration had the same effect.Footnote20

5.6. Stage 3 (2012–17): political process and the support for independence

The 2012 election returned the CiU (CDC) to government, though now reinforced by the ERC through a legislative agreement to hold a vote on self-determination.Footnote21 The independentist parties made several attempts to hold such a vote. The request for a formal referendum was rejected as unconstitutional by the two main state-wide parties, the PP and PSOE, in April 2014 (Garea, Citation2014). The Catalan executive’s own legislation on referenda was suspended by the Spanish Constitutional Court later on.Footnote22 In response, the Catalan government settled on a ‘participatory process’, to be carried out by volunteers. The vote was held on 9 November 2014, with 2.3 million people participating. As the final attempt to hold a referendum without breaching the constitutional framework, Mas called a plebiscitary election for the fall of 2015. The CDC, ERC and key civil society figures ran on a joint platform, Together for Yes (Junts pel Sí – JxSí). Along with the secessionist and anti-capitalist Popular Unity Candidacy (Candidatura d'Unitat Popular – CUP), the independentist block presented a ‘road map’ which called for a proclamation of independence within 18 months of the election.

The independentist coalition won the plurality of seats, but not the majority of votes. Since it fell short of the parliamentary majority, its path to government now depended on CUP.Footnote23 The latter leveraged its position to win a declaration on the creation of the independent Catalan state, the sovereignty of the Catalan parliament, and the supremacy of Catalan over Spanish laws in the event the two clashed.Footnote24 It also managed to have Artur Mas replaced by a new president, Carles Puigdemont (Masreal & Barrena, Citation2016). Finally, in the summer of 2016, CUP strong-armed Puigdemont into committing to a vote on self-determination, with or without the assent of the Spanish government (Piñol & Cordero, Citation2016).Footnote25 This radicalisation was further driven by the continuing outbidding between the ERC and CDC (subsequently the Catalan European Democratic Party/Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català – PDeCAT),Footnote26 and the persistent activism of civil society organisations. The ANC organised multitudinous Diada demonstrations each year from 2012 to 2018. It also spurred politicians toward radical positions through its own proposals (‘La ANC sitúa’, Citation2014). Neither the CDC nor the ERC wanted to lose the favour of independentist associations and be portrayed as the party responsible for undermining national unity.

The result of these developments was the Catalan government’s decision to hold a unilateral referendum on independence. On 6–7 September 2017, the Catalan parliament passed the Law on the Referendum on Self-Determination,Footnote27 and the Law on the Legal Transition and the Foundation of the Republic.Footnote28 The former established the legal framework for the referendum, and the latter laid the legal foundation for the formation of the Catalan Republic. The laws were passed during a turbulent parliamentary session in which the independentist parties bypassed parliamentary rules, against the recommendation of the advisory legal body of the Catalan government (‘El Parlamento de Cataluña’, Citation2017). The regional government then forged ahead with the organisation of the referendum, over the opposition of the Spanish Constitutional Court and the central government. The Spanish government countered by establishing control over Catalonia’s public finances and deploying additional security forces in order to dismantle the infrastructure necessary for the referendum (Baquero & Albalat, Citation2017; Maqueda & Díez, Citation2017).

Before 1 October, the day of the referendum, clusters of people surrounded the polling stations anticipating that security personnel would try to prevent the vote. On that day units of Spanish police moved in to seal the stations, in the process beating a number of those surrounding them. After a tense political stand-off lasting several weeks, on 27 October the independentist parties voted to approve a unilateral declaration of independence. On the same day, the Spanish Senate activated Article 155 of the Constitution. The application of the Article resulted in the first suspension of self-government of a Spanish AC since the reestablishment of democracy (Garcia Pagan, Citation2017). As shows, however, this unprecedented institutional shift, combined with police violence against civilians, criminal charges against a range of officials at various levels and the arrest of several independentist leaders, including politicians and heads of key civil society organisations,Footnote29 failed to produce a significant increase in support for independence.

5.7. Stage 3 (2012–17): the meaning of the suspension of autonomy

As we have argued throughout, the causal efficacy of institutional change depends on the process through which it occurs, on the interpretation of that process, and the success in establishing that interpretation as a widespread social fact. In the first two periods under consideration, institutional change left an indirect imprint on Catalan politics, contributing to incremental, halting, and above all contingent advance of secessionism. By October 2017, however, independence became a mainstream political cause, pursued by the regional government, and supported by approximately half the population of the region and a web of mass-based civil society organisations. Under these conditions, it was reasonable to expect that any loss of autonomy, particularly if accompanied by violence and arrests of independentist leaders, would result in still higher support for secession. The absence of such a shift provides further evidence of the lack of a direct and unmediated link between objective institutional change and support for independence.

An alternative explanation for the absence of a secessionist surge in October 2017 is that by that point support for independence had reached its limits. Indeed, backing for independent Catalonia never exceeded the combined vote for Catalan ‘nationalist’ parties – just under 50% (Medina & Rico, Citation2019, pp. 19–25). We consider this to be too deterministic an explanation for two main reasons. First, notionally non-independentist parties (PSC, IC-V and later Catalonia Yes We Can/Catalunya Sí que es Pot – CSQP) also relied on a segment of the nationalist vote, which is why they found it difficult to navigate the tensions that ‘the process’ brought about (Medina & Rico, Citation2019, pp. 18–19). If Catalan nationalists are the only potential voters for independence, then the fact that some of them had voted for non-independentist parties suggests that the potential reservoir of secessionist support was greater than that suggested by the vote for nationalist parties alone. Second, ‘unionist’ residents of Catalonia exhibit significantly lower intensity of institutional preferences than do their ‘nationalist’ counterparts (Miley & Garvia, Citation2019, pp. 7–8). Both factors suggest that the potential support for independence might be higher than revealed either by the opinion polls or regional election results.

This counterfactual speculation becomes more plausible when we consider the manner in which pro-independence parties set the stage for the 1 October vote. As noted, the passage of the relevant laws in preparation of the referendum was highly contentious. In addition, independentist parties pursued their goal without having won the majority of the vote. Finally, the decision to hold the referendum on 1 October was opposed by both the Spanish government and the country’s judiciary. This is particularly important given the opposition to a unilateral referendum among a significant proportion of the Catalan public.Footnote30 All three factors may have influenced the perception of the gravity of the application of Article 155 for a segment of Catalan population. Indeed, this was the interpretation of the relevant events by Joan Coscubiela, the spokesperson of the non-secessionist party with the highest percentage of pro-independence voters, the CSQP (Cordero, Citation2017). The CSQP took the position that neither the unilateral pursuit of independence, nor the application of Article 155 were legitimate.

The aftermath of the application of Article 155 suggests that illegitimacy of the loss of autonomy might be offset by the illegitimacy of the moves made by secessionist actors for at least one part of Catalonia's population. It is also possible that the suppressive action by the Spanish central government may have had a chilling effect on the willingness of individuals to express support for independence in subsequent surveys. This assumption comports with the work on the role of efficacy in social mobilisation (van Zomeren et al., Citation2004), though further research will have to test the validity of these conjectures.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Lost autonomy theories of secession represent a welcome theoretical advance on the largely static scholarship preceding them. They turn to the role of institutional change, notably the loss of autonomy, as a catalyst of support for independence. Yet these contributions rest on a set of disputable assumptions related to their master concept. Their central premise is that a decline in objective levels of autonomy is automatically perceived as such by the relevant political actors. Moreover, this perception is presumed to have an unmediated effect on the dissatisfaction among those losing institutional power, leading to an increase in their propensity to support secession.

In this article we question these assumptions. We point to two causal mechanisms through which institutional change may boost support for secession. We base these mechanisms on the examination of secessionist mobilisation in Catalonia from 2003 to 2017, though our conclusions are based on suggestive evidence and ought to be supplemented by further empirical research. First, institutional change must be interpreted as constituting a political loss. Moreover, that interpretation must be accepted by a sufficiently broad segment of the target population. As our case analysis demonstrates, a particular change will not automatically be perceived as a loss by all members of a community. Much depends on the specific pattern of change, and the way in which it is interpreted by the relevant actors.

Second, even if institutional change is broadly considered as a political loss, it does not follow that all who see it as such will look to secession as the most appropriate response. The link between the loss of institutional influence and support for independence must be forged politically. We see this both in the aftermath of the 2010 Constitutional Court decision, and after the suspension of Catalonia’s autonomy in 2017. In both cases there was consensus among major Catalan political parties that the decisions reduced Catalonia’s autonomy. However, political actors continued to diverge on the appropriate way forward. In addition, these two mechanisms are still not going to produce a secessionist turn unless a sufficient number of people believe that their support for independence makes it more likely.

Our analysis thus points to the importance of a social understanding of institutional change. The lost autonomy theories of secession focus on the way in which researchers understand the meaning of that change, in the implicit belief that the coders’ assessment will accurately capture the perceptions of the relevant actors. This (neo)positivist view of social phenomena presupposes that shifts in institutional features possess inherent meaning. Our article demonstrates that the meaning of institutional change cannot be readily inferred from attributes such as objectivised levels of autonomy. Rather, that meaning may be a combined product of deliberate framing efforts and of political processes that produce institutional change. This means that the same ‘magnitude’ of institutional change might assume different meaning depending on the contingent political and interpretive dynamics to which it is subjected.

This view of institutional change has important methodological implications for the comparative study of secession. First, when it comes to assessing institutional change, our focus should shift from coding ‘objective’ shifts in levels of autonomy toward grasping the meaning of those shifts among political elites and populations. Second, while it is possible to code the outcome of those processes, this is difficult to do, especially where the same institutional modification produces a range of different interpretations. In those instances, coding might, for instance, fail to pick up on important processes of collective interpretation, ones that might not necessarily produce an immediate outcome, but that might nevertheless be an important stepping stone to mobilisation at a later point. The resulting theories might then develop incorrect inference about the mechanisms that link institutional change to support for independence.

Future research into the link between institutional change and support for secession will need to move beyond the suggestive material we provide here. The first step will be to establish empirically the degree to which particular episodes of institutional change result in divergent interpretations among the relevant actors. The most efficient way to do this would be to engage with local experts – scholars and journalists from different ideological milieux – and determine to what extent their understandings of the same institutional reality diverge. The next step would be to pursue the same line of inquiry with non-experts, for instance through focus groups with participants sampled from divergent social circles. This would enable researchers to reconstruct narratives that would provide important insights into the way in which the ‘raw material’ of institutional transformation registers with the relevant actors. The societal prevalence of distinctive narratives could then be assessed through surveys.

Knowing how institutional change is perceived by various social actors at a given point, however, would not advance our understanding of the emergence, spread, and change of institutional narratives over time, nor would it explain why some narratives crowd out others. That task would require careful process-tracing to uncover the social and political dynamics through which particular interpretations emerge, gain adherents, and facilitate political transformation. The potential of this research agenda ultimately hinges on the central point of this article. In order to open up the black box of institutional change and improve our understanding of its relationship to secessionist mobilisation, scholars ought to reconsider the idea of that change as an objective, experience-distant phenomenon, and envision it as an experience-near social fact.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All interviewees named in the article have given their explicit and informed consent verbally, as per the ethics approval process specified by the Memorial University of Newfoundland.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Adam Holesch, André Lecours, Zoran Oklopčić, Srđan Vučetić and two anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions and comments.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

4 Freedom House has Spain in its highest category for political and civil liberties throughout this period (https://freedomhouse.org/reports/publication-archives). Catalonia’s regional authority index self-rule score was 13 for the 1997–2006 period, higher than the German and Austrian Länder, and as high as Belgian regions and Scotland (Hooghe et al., Citation2010, appx B). Its shared rule score for the same period was 1.5, significantly lower than the German and Austrian Länder (9 and 6, respectively), Belgian regions (5) and Scotland (3.5).

5 The interviews were conducted with six individuals in key organisational positions. Bertran was the leader of the Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya’s (ERC) Esquerra Independentista (EI) faction; Castro was a member of the national secretariat of the Catalan National Assembly (ANC); Mas was president of the Catalan government; Paluzie was a member of the pro-independence organisation Sobirania i Progrés and a member of EI; Strubell was one of the four initiators of what would become the ANC. We interviewed individuals in the independence movement because we wished to understand whether and how they were attempting to translate institutional change into support for independence and what the role of non-institutional factors played in their decisions.

6 Whether or not this system is federal is a matter of controversy among scholars (Sala Citation2014).

7 A total of 73.2% of voters endorsed the Statute on 48.9% turnout (https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=eler&n=402&lang=es).

8 Interview with Elisenda Paluzie, Barcelona, 30 May 2014.

9 Cf. Article 204 of the 2005 document (https://www.parlament.cat/document/cataleg/48104.pdf) with Article 203 of the final version (https://www.parlament.cat/document/cataleg/48146.pdf).

10 Interview with an anonymous member of the ERC, Barcelona, 23 May 2017.

11 Interview with Uriel Bertran, Barcelona, 5 June 2014.

12 Elisenda Paluzie recalls experts linked to the movement explaining that support for independence rises once a referendum becomes possible; interview with Elisenda Paluzie, Barcelona, 30 May 2014.

13 Interview with Miquel Strubell, 19 July 2018.

14 Interview with Liz Castro, Barcelona, 26 April 2017.

15 When respondents were asked directly how they would vote in a hypothetical referendum, 57% expressed support for independence. See the responses to question 39 at https://upceo.ceo.gencat.cat/wsceop/4308/Taules%20estad%C3%ADstiques%20-%20Intenci%C3%B3%20vot%20Parlament%20Catalunya-705.pdf

16 Interview with Liz Castro, Barcelona, 26 April 2017.

17 Interview with Artur Mas, Barcelona, 24 October 2018.

19 Unpublished manifesto. We are grateful to Elisenda Paluzie for this material.

20 Interview with Liz Castro, Barcelona, 26 April 2017.

26 A typical example occurred in mid-2017 when members of the ERC accused PDeCat of not being committed to the unilateral pursuit of independence, with the latter retorting that it was their own members who had their mandates suspended due to the pursuit of the referendum (Masreal & Barrena, Citation2017).

29 For a summary, see López and Sanjaume (Citation2020, pp. 507, 515).

30 Surveys in April and August 2017 showed 75% of Catalans favouring a referendum, but only 30–37% of those endorsing a referendum without central government’s approval (Castro Citation2017; La Mayoría Quiere un Referéndum Pactado y Descarta la Unilateralidad, Citation2017).

REFERENCES

- Acuerdo Para un Gobierno Catalanista y de Izquierdas en la Generalitat de Catalunya. (2003). http://www.latinreporters.com/espagnepactedetinell.pdf

- Agència Catalana de Notícies. (2009). L’exconseller Agustí Bassols, president de la ‘junta electoral’ de la consulta d’Arenys. El Punt Avui, September 10, 2009. https://www.elpuntavui.cat/politica/article/17-politica/281335-lexconseller-agusti-bassols-president-de-la-junta-electoral-de-la-consulta-darenys-.html

- Ahram, A. (2020). Separatism, the Arab uprisings and the legacies of lost territorial autonomy. Territory, Politics, Governance, 8(1), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1532810

- ‘Ara Toca No. Catalunya Mereix Més’, Lema de ERC en su Campaña Sobre el Estatut. (2006). La Vanguardia, May 23, 2006. https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20060523/51262823289/ara-toca-no-catalunya-mereix-mes-lema-de-erc-en-su-campana-sobre-el-estatut.html

- Baquero, A., & Albalat, J. G. (2017). La Guardia Civil incauta nueve millones de papeletas del referéndum en Bigues i Riells. El Periódico, September 20, 2017. https://www.elperiodico.com/es/politica/20170920/12-detenidos-en-una-operacion-de-la-guardia-civil-contra-el-referendum-6297933

- Barrio, A. (2009). Alianzas entre partidos y cambio organizativo: El caso de Convergència i Unió. Papers. Revista de Sociologia, 92, 51–74. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers/v92n0.707

- Barrio, A. (2017). Ciu: de la mutación a la desaparición. In J. Marcet & L. Medina (Eds.), La política del proceso: Actores y elecciones (2010–2016). Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.

- Barrio, A. (2018). El sistema de partits. In G. Ubasart-González & M. i. P. Salvador (Eds.), Política i Govern a Catalunya. Catarata.

- Barrio, A., & Rodríguez-Teruel, J. (2017). Reducing the gap between leaders and voters? Elite polarization, outbidding competition, and the rise of secessionism in Catalonia. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(10), 1776–1794. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1213400

- Basta, K. (2018). The social construction of transformative political events. Comparative Political Studies, 51(10), 1243–1278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017740601

- Basta, K. (2021). The symbolic state: Minority recognition, majority backlash, and secession in multinational countries. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Bevir, M., & Kedar, A. (2008). Concept formation in political science: An anti-naturalist critique of qualitative methodology. Perspectives on Politics, 6(3), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592708081255

- Broschek, J. (2015). Pathways of federal reform: Australia, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland. Publius, 45(1), 51–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pju030

- Castro, C. (2017). El Referéndum Unilateral Pierde Apoyos Frente a La Consulta Acordada. La Vanguardia, April 16, 2017. https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20170416/421751405001/encuesta-convocatoria-referendum-independencia-catalunya.html

- Cederman, L.-E., Hug, S., Schädel, A., & Wucherpfennig, J. (2015). Territorial autonomy in the shadow of conflict: Too little, Too late? American Political Science Review, 109(2), 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055415000118

- Chandra, K. (2005). Ethnic parties and democratic stability. Perspectives on Politics, 3(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592705050188

- Coggins, B. (2011). Friends in high places: International politics and the emergence of states from secessionism. International Organization, 65(3), 433–467. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818311000105

- Colino, C. (2013). The state of autonomies between the economic crisis and enduring nationalist tensions. In B. N. Field, & A. Botti (Eds.), Politics and Society in Contemporary Spain: From Zapatero to Rajoy (pp. 81–100). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Colomer, J. M. (2017). The venturous bid for the independence of Catalonia. Nationalities Papers, 45(5), 950–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2017.1293628

- Cordero, D. (2017). ‘Antes del 1 de octubre es imposible hallar una salida; después, es imprescindible.’ El País, September 9, 2017, sec. Catalunya. https://elpais.com/ccaa/2017/09/09/catalunya/1504973587_922350.html.

- Cunningham, K. G., Dahl, M., & Frugé, A. (2019). Introducing the strategies of resistance data project. Journal of Peace Research, 57(3), 482–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343319880246

- El mayor nivel de autogobierno. (2006). El País. August 10, 2006. http://elpais.com/diario/2006/08/10/espana/1155160814_850215.html.

- El Parlamento de Cataluña Acuerda Tramitar Hoy La Ley de Referéndum En Medio de Una Gran Bronca. (2017). La Vanguardia, September 6, 2017. https://www.lavanguardia.com/local/barcelona/20170906/431090295512/el-parlamento-de-cataluna-acuerda-tramitar-hoy-la-ley-de-referendum-en-medio-de-una-gran-bronca.html

- Falleti, T. (2005). A sequential theory of decentralization: Latin American cases in comparative perspective. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051695

- Garcia Pagan, I. (2017). DUI, Intervención y Elecciones. La Vanguardia, October 27, 2017. https://www.lavanguardia.com/edicion-impresa/20171028/432398412757/dui-intervencion-y-elecciones.html

- Garea, F. (2014). La Constitución frena la consulta. El País, April 8, 2014, https://elpais.com/politica/2014/04/08/actualidad/1396986575_704072.html

- Germann, M., & Sambanis, N. (2020). Political exclusion, lost autonomy, and escalating conflict over self-determination. International Organization, 75(1), 178–203. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000557

- Gerring, J. (2007). Is there a (viable) crucial-case method? Comparative Political Studies, 40(3), 231–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006290784

- Gerring, J. (2012). Mere description. British Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 721–746. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123412000130

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., & Schakel, A. (2010). The rise of regional authority: A comparative study of 42 democracies. Routledge.

- Jenne, E. K. (2009). The paradox of ethnic partition: Lessons from de facto partition in Bosnia and Kosovo. Regional & Federal Studies, 19(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560902789853

- La ANC Sitúa La Proclamación de Independencia En Sant Jordi de 2015. (2014). La Vanguardia, March 13, 2014. https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20140313/54403054300/anc-proclamacion-independencia-sant-jordi-2015.html

- La Mayoría Quiere un Referéndum Pactado y Descarta la Unilateralidad. (2017). La Vanguardia, January 9, 2017. https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20170109/413193401276/referendum-catalunya.html

- La Prensa Catalana Publica un Editorial Conjunto en Defensa del Estatut. (2009). La Vanguardia, November 25, 2009. https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20091125/53831111238/la-prensa-catalana-publica-un-editorial-conjunto-en-defensa-del-estatut.html

- Lecours, A. (2021). Nationalism, secession, and autonomy. Oxford University Press.

- Levy, J. (2008). Case studies: Types, designs, and logics of inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388940701860318

- Lijphart, A. (1977). Democracy in plural societies: A comparative exploration. Yale University Press.

- Linz, J. (1989). Spanish Democracy and the Estado de Las Autonomías. In R. A. Goldwin, A. Kaufman, & W. A. Schambra, and American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research (Eds.), Forging unity out of diversity: The approaches of eight nations. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Lluch, J. (2014). Visions of sovereignty: Nationalism and accommodation in multinational democracies. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- López, C. E. D. (1981). The state of the autonomic process in Spain. Publius, 11(3), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a037372

- López, J., & Sanjaume, M. (2020). The political use of de facto referendums of independence the case of Catalonia. Representation, 56(4), 501–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2020.1720790

- MacIntyre, A. (1972). Is a science of comparative politics possible? In P. Laslett, W. G. Runciman, & Q. Skinner (Eds.), Philosophy, politics and society, fourth series: A collection. Barnes & Noble.

- Maiz, R., Caamaño, F., & Azpitarte, M. (2010). The hidden counterpoint of Spanish federalism: Recentralization and resymmetrization in Spain (1978–2008). Regional & Federal Studies, 20(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560903174923

- Maqueda, A., & Díez, A. (2017). El Gobierno interviene todos los pagos de servicios esenciales y nóminas de la Generalitat. El País, September 16, 2017. https://elpais.com/politica/2017/09/15/actualidad/1505470229_074445.html.

- Masreal, F., & Barrena, X. (2016). Mas cede la presidencia a cambio de someter a la CUP. El Periódico, January 9, 2016, web edition. https://www.elperiodico.com/es/politica/20160109/mas-cede-paso-a-puigdemont-a-cambio-de-someter-a-la-cup-4803789

- Masreal, F., & Barrena, X. (2017). La Guerra Larvada En El Govern Tensa Los Preparativos Del Referéndum. El Periódico, July 1, 2017, web edition. https://www.elperiodico.com/es/politica/20170701/tension-govern-pdecat-erc-referendum-1o-6139608

- McGarry, J., O’Leary, B., & Simeon, R. (2008). Integration or accommodation? The enduring debate in conflict regulation. In S. Choudhry (Ed.), Constitutional design for divided societies: Integration or accommodation? Oxford University Press.

- Medina, L., & Rico, G. (2019). The plebiscitary moment in Catalonia: Voters and parties through the independence challenge (2012-2017) (Working Paper No. 364). Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.

- Medir, L. (2015). Understanding local democracy in Catalonia: From formally institutionalized processes to self-organized social referenda on independence. International Journal of Iberian Studies, 28(2), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijis.28.2-3.267_7

- Miley, T. J., & Garvia, R. (2019). Conflict in Catalonia. A sociological approximation. Genealogy, 3(4), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040056

- Muñoz, J., & Guinjoan, M. (2013). Accounting for internal variation in nationalist mobilization: Unofficial referendums for independence in catalonia (2009–11). Nations and Nationalism, 19(1), 44–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12006

- Noguer, M. (2010). Decenas de miles de catalanes se echan a la calle contra el recorte del Estatuto. El País, July 10, 2010, sec. Actualidad. https://elpais.com/elpais/2010/07/10/actualidad/1278749824_850215.html.

- ‘Nosaltres Decidim, Som Una Nació’ Será El Lema de La Marcha Del 10 de Julio. (2010). La Vanguardia. June 29, 2010. https://www.lavanguardia.com/politica/20100629/53954278364/nosaltres-decidim-som-una-nacio-sera-el-lema-de-la-marcha-del-10-de-julio.html

- Núñez Seixas, X. (2005). De la región a la nacionalidad: Los neo-regionalismos en la España de la transición y la consolidación democrática. In C. H. Waisman, R. Rein, & A. G. Abad (Eds.), Transiciones de la dictadura a la democracia: los casos de España y América Latina (pp. 101–140). Universidad del País Vasco.

- Piñol, À., & Cordero, D. (2016). La CUP veta los Presupuestos y deja en el aire la legislatura. El País, June 8, 2016, sec. Catalunya. https://elpais.com/ccaa/2016/06/07/catalunya/1465306125_265699.html.

- Piñol, À., & Cué, C. E. (2012). Mas se prepara para las elecciones tras la negativa de Rajoy al pacto fiscal. El País, September 20, 2012, sec. Politica. https://elpais.com/politica/2012/09/20/actualidad/1348131201_261707.html.

- Rabushka, A., & Shepsle, K. A. (1972). Politics in plural societies: A theory of democratic instability. Merrill.

- Requejo, F., & Sanjaume, M. (2015). Recognition and political accommodation: From regionalism to secessionism – The Catalan case. In J.-F. Grégoire & M. Jewkes (Eds.), Recognition and redistribution in multinational federations. Leuven University Press.

- Reynaerts, J., & Vanschoonbeek, J. (2022). The economics of state fragmentation: Assessing the economic impact of secession. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 37(1), 82–115. http://doi.org/10.1002/jae.v37.1

- Roeder, P. G. (2007). Where nation-states come from: Institutional change in the Age of nationalism. Princeton University Press.

- Sala, G. (2014). Federalism without adjectives in Spain. Publius, 44(1), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjt010

- Schaffer, F. (2016). Elucidating social science concepts: An interpretivist guide. Routledge.

- Schwartz-Shea, P., & Yanow, D. (2011). Interpretive research design: Concepts and processes. Routledge.

- Siroky, D. S., & Cuffe, J. (2015). Lost autonomy, nationalism and separatism. Comparative Political Studies, 48(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013516927

- Sorens, J. (2012). Secessionism: Identity, interest, and strategy. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., Fischer, A. H., & Leach, C. W. (2004). Put your money where your mouth is! Explaining collective action tendencies through group-based anger and group efficacy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 649–664. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.649

- Walter, B. F. (2009). Reputation and civil War: Why separatist conflicts Are so violent. Cambridge University Press.

- Wimmer, A., Cederman, L.-E., & Min, B. (2009). Ethnic politics and armed conflict: A configurational analysis of a New global data Set. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 316–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400208

- Wlezien, C., & Soroka, S. N. (2011). Federalism and public responsiveness to policy. Publius, 41(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjq025