ABSTRACT

To achieve climate neutrality by 2050, Czechia and Germany have created framework conditions to phase out lignite while developing the coal regions into pioneers of sustainability transformation. These clean energy transitions are associated with a wide range of threats and opportunities, including employment and identity issues. Based on two European case studies – the Ústí Region in Czechia and Lusatia in Germany – we investigate regional development paths and the use of strategic planning instruments to prepare for structural change. We identify inclusive governance structures, place-based strategic planning and cross-domain knowledge networks as key influencing factors for regional transformation at early stages of the process.

1. INTRODUCTION

The discourse on climate targets and the sustainable development of Europe has gained momentum in recent years. This has culminated in the 2019 adoption of the European Green Deal, in which states of the European Union (EU) set themselves ambitious climate protection goals. The aim of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 requires emissions reductions as well as better protection and more efficient use of resources (European Commission, Citation2019a; Kemfert, Citation2019). Energy policy is expected to make an important contribution to the transitions to a carbon-free Europe by promoting energy efficiency and renewable energies, phasing out fossil fuels, and supporting diversification and decarbonisation of the economy. National discussions over phasing out lignite, such as in Germany and Czechia, are linked to these European energy policy ambitions as well as to challenges of regional development.

The expectations of the Green Deal, however, are more far-reaching: It is intended to be the EU’s new growth strategy, both reducing emissions and creating jobs (European Commission, Citation2019a). Furthermore, it envisages a ‘just transition’ in order to avoid further polarisation in the EU by ensuring fairness through redistribution mechanisms and investments in the green economy (Kemfert, Citation2019; Lucchese & Pianta, Citation2020). The Just Transition Mechanism lays special focus on those regions that are most affected by the transition processes, addressing fair working conditions and measures to avoid poverty and unemployment, support a healthy environment and education, create jobs and improve quality of life (proposal for Regulation COM/2020/22). It is intended to give regions tailored support to make necessary investments and thus mitigate the negative impacts of transitions. One instrument for implementing the objectives of the Just Transition Mechanism is the Initiative for Coal Regions in Transition (launched in 2017 as the Coal Regions in Transition Platform). The Initiative brings together stakeholders at EU, national, regional and local levels to promote dialogue and partnership to address environmental and social challenges and compensate for disadvantages in the coal regions (European Commission, Citation2017; Görlitz Declaration, Citation2019).

This article analyses and compares the transitions process in the Czech–German border region, in which lignite is being phased out and a regional exchange on energy transition and regional development has begun. Various regional challenges overlap in the selected coal regions in Ústí Region, Czechia, and Lusatia, Germany. Besides the requirements of the energy transitions, these regions face the challenge of moving away from an economy dominated by a single sector, and countering long-standing peripheralisation trends, characterised by population decline, and economic and political decoupling effects (Kühn & Lang, Citation2017). Although these coal regions are similar in many respects, each represents a different institutional environment within which the concepts of the Just Transition Mechanism are implemented. One of the contributions of this paper is to provide an analysis of the specific and different approaches to clean energy transitions in two individual EU member states.

The two selected regions () are not only affected by recent debates on climate change and the decreasing competitiveness of lignite-based power generation. Although with different causes, both regions have been subject to similar processes of peripheralisation since the political transition of the 1990s, which was accompanied by a wave of deindustrialisation. Whereas before the dissolution of socialism both regions were national powerhouses and coal shaped not only their economies but also the identity of their inhabitants (Herberg et al., Citation2020), they have subsequently fallen into decline, with outmigration of young and well-educated people and a loss of political and social significance. Structural change must therefore address both the economic and social needs of the regions’ inhabitants. After all, the upcoming structural change is associated with social uncertainties, polarisation and fears of decline that may encourage people to cling to old industrial structures and thus limit the capacity of these regions to engage in transformative change again (Heer et al., Citation2020).

Figure 1. Location of the case studies and coal areas in Germany and Czechia.

Source: Authors’ own map based on Eurostat (2019) and Euracoal (2020).

In this paper, the conceptual framework of transformative capacities is used in order apply a systemic understanding of what types of governance capacities enable transformative change in the regions (Wolfram, Citation2016; Castán Broto et al., Citation2019). Thereby, the phasing out of coal mining and coal-fired energy generation is understood as a multilevel, multi-actor, multi-domain and long-term process with significant social, environmental and economic impacts (Loorbach et al., Citation2017). Transformation is seen as a complex challenge embracing many areas of regional development rather than as a purely sectoral challenge. In order to prevent sectoral change from affecting the entire region through downward spirals of peripheralisation, the states and regions apply governance instruments and structural policy approaches, such as decentralisation strategies. In addition, intermediaries and strategic planning processes are being developed to provide regional actors with orientation and capacity for action in the transformation process. These approaches could strengthen the regional level if they involve regional actors and seek to link governance mechanisms to increase the impact of policies (Boyle et al., Citation2021; Kivimaa et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the component ‘inclusive and multiform of governance’ (Wolfram, Citation2016) of transformative capacity is used as a lens of enquiry in this paper.

With regard to the ambitious goals set out in climate and energy policies and the socio-economic challenges within the regions, we address the following research questions in the selected coal regions:

To what extent can transformative capacity approaches contribute to a better understanding of coal phase-out processes in peripheral regions in international comparison?

What approaches to regional governance and strategic planning are stakeholders using to support the incipient structural transformation in coal phase-out regions?

To what extent do the approaches differ in their respective contexts?

In order to answer these questions, we apply theoretical approaches drawn from sustainability transitions research, as they offer analytical tools for sectoral and spatial development while integrating a sustainability perspective. We place a special focus on strategies to build transformative capacities and ask what role strategic planning can play in shaping the early phases of the energy transitions (section 2). We then focus on the two case studies and analyse the respective framework conditions, strategic approaches, and their potentials and obstacles (section 3). The final section 4 compares the two case studies and draws conclusions for further research and regional policies. This approach allows us to make an essential contribution to research on transformative capacities and the governance of regional transformation processes. We do this by applying the transformative capacity approach (Wolfram, Citation2016; Castán Broto et al., Citation2019) to case studies that examine change dynamics in peripheral regions that may not be ‘transformation-friendly’ and thereby bring spatial characteristics into the debates about transitions. At the same time, we extend the transformative capacities framework in the area of governance by examining the role of and barriers to strategic spatial planning in processes of just transitions.

2. THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO STRUCTURAL CHANGE: FROM SECTORAL APPROACHES TO SUSTAINABLE TRANSFORMATION

Structural change in regions caused by transformation of a dominant sector can be conceptualised from different perspectives and disciplines, such as science and technology studies (Mayntz, Citation2008), innovation research (Fornahl et al., Citation2012; Füg & Ibert, Citation2020), political ecology (Hodson et al., Citation2013), resilience research (Lintz et al., Citation2012; Pendall et al., Citation2010) and transition studies (Grillitsch & Hansen, Citation2019; Loorbach et al., Citation2017). The Sustainability Transitions Research (STR) paradigm, and the concept of transformative capacity, provide a basis for analysing aspects of governance and strategic planning in transformation processes (Loorbach et al., Citation2017; Wolfram, Citation2016).

2.1. Sustainability transitions research

STR is an emerging field of scholarship on transformation processes with a fast-growing body of literature. According to STR, the transitions to sustainability constitutes a ‘grand societal challenge’ and must include not only more efficient technologies, but also more sustainable behavioural patterns and market structures (Geels, Citation2010). Research should aim to better understand how transitions occur and how to manage transition processes towards sustainability (Loorbach et al., Citation2017). Following regional economics, transitions are conceptualised as non-linear developments with disruptive breaks often caused by external disturbances (such as technological innovation or crises) that create tensions, disrupt equilibria, allow niche actors to break through, and increase demand for system change (Kivimaa et al., Citation2019; Rotmans & Kemp, Citation2001).

The role of supportive governance structures, intermediation and strategic planning for transition processes is underlined in particular by the concept of transformative capacity (Wolfram, Citation2016). In their concept for transformation governance, Hölscher et al. (Citation2019a, Citation2019b) distinguish between stewarding, unlocking, transforming and orchestrating capacities, and test this analytical framework on urban case studies. In this definition, ‘transforming capacity’ focuses on nurturing innovation and experimentation as a cornerstone of transformation, whereas ‘orchestrating capacity’ emphasises the importance of coordination across multiple actors, ‘unlocking capacity’ describes the ability of actors to recognise and dismantle structural drivers of unsustainable path-dependencies, and ‘stewarding capacity’ refers to the ability to exploit opportunities beneficial for sustainability. Wolfram (Citation2016) includes these four dimensions and describes transformative capacity as the ability of a system to reconfigure itself and move toward a new and more sustainable state. As a systemic property, transformative capacity is the result of contingent interactions between various actors in particular institutional and material settings, rather than an attribute of individual actors (Ziervogel et al., Citation2016). It consists of several components that in a regional governance perspective can be understood as potential leverage points, the development of which can strengthen transformation efforts, accelerate change, and steer it in the desired direction. The following elements are considered to be key prerequisites for transformative capacity as it relates to governance in particular: (1) inclusive and multilevel governance, (2) transformative leadership based on a shared vision, motivational engagement, and collaborative processes, and (3) strengthened communities of practice that address social needs (Wolfram, Citation2016). The concept highlights the need to combine place-based capacities and cross-scale relationships, and ‘draws attention not only to access to resources, but also to latent strengths or capabilities to pursue transformative change’ (Castán Broto et al., Citation2019, p. 452).

The transformative capacity framework has received theoretical attention and been applied in urban settings, but requires operationalisation in regional settings in order to provide practical guidance for capacity-building and transition management. Nevertheless, the literature offers useful insights into what constitutes transformative capacity as it might relate to regional planning and governance.

Regarding the strategic development of aspects of transformative capacity, social learning, communication and visioning have been identified as useful at the acceleration stages of transitions (Kanda et al., Citation2020; Kivimaa et al., Citation2019). In particular, systems analysis, foresight, experimentation and collective reflexivity provide social learning tools for understanding and fostering change dynamics (Hölscher et al., Citation2019b; Wolfram et al., Citation2019). Christmann (Citation2010) also emphasises that intersubjective sense-making and symbolic constructions of reality through which people create shared interpretations – such as debates, conversations and learning processes – play an important role in transition phase. The transition gains momentum when socio-cognitive processes converge leading to shared views and agreement on the best way forward. Hence, participatory visioning processes, multi-stakeholder learning processes and societal debates, are especially important transformation (Kivimaa et al., Citation2019; Rotmans & Kemp, Citation2001). Geels (Citation2010) emphasise that transitions to sustainability are hindered by a lack of shared visions. Strategic planning processes offer contributions to create shared visions, operational capacities to act and opportunities for social learning. These assumptions open the field to debates about strategic planning and its role in transition processes.

As with urban sustainability transformations, regional transitions strongly depend on the pathways taken by regions and place-specific resources, capacities and processes. It may thus be fruitful to combine complementary insights from STR and spatial research traditions (Truffer & Coenen, Citation2012). The next section highlights findings from spatial research, which characterise strategic planning and its potential to support social learning and collaborative vision design. While transition research is mostly focused on urban areas in which several actors promote transformative processes it has engaged less with the regional dimension. To fill this gap, we seek to identify aspects that can support a conceptual framework for regional analysis in peripheral regions.

Peripheral regions are characterised by specific features that do not allow a direct transfer of the assumptions and concepts pertaining to urban areas. For instance, peripheral regions are often characterised by a lack of innovation. Although there are usually spaces for experimentation in regions, trends such as outmigration of the younger population mean that there is not a critical mass of actors willing to experiment, and a lack of entrepreneurs and strong civil society networks (Kühn & Lang, Citation2017). Among the remaining population, negative transformation experiences or firmly anchored identities may reinforce resistance to innovation. New visions of a positive future (Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2019) seem particularly important for transformations, yet are more difficult to communicate and anchor in peripheralised regions. In addition, such spaces are often highly fragmented, with competencies divided among different territorial and sectoral actors who rarely speak with one voice and make peripheral space their priority. Regional interests may not be well represented at higher level as there may be a lack of coordinating actors who take responsibility for the region. Because of these characteristics of peripheral regions, actors in (strategic) planning or academia can become key network nodes in the region and help mobilise and develop transformative capacity.

2.2. Strategic planning for transformation processes

Transformative capacities can be developed through new visions and by planning ambitions to resolve conflicting goals through comprehensive approaches that incorporate diverse resources and competencies (Wolfram, Citation2016). These tasks are at the core of spatial planning, which is why we highlight the role of planning approaches for change in coal regions. However, not all forms of spatial planning are equally appropriate (Wolfram et al., Citation2019). Criticisms of formal spatial planning highlight a lack of flexibility, a lack of cooperation and participation, and a gap between long-term orientation and implementation (Healey, Citation1997, Citation2006).

Strategic planning has emerged from these criticism and supports the development of a shared orientation, social learning and coordinated agency in the transformation process by addressing collaborative practices (Albrechts, Citation2004; Innes & Booher, Citation2003). In our analysis of ways to strengthen transformative capacity, we therefore focus on strategic planning approaches that place particular emphasis on mediation across scales and sectors, demonstrate openness to innovative solutions and create intermediaries that promote sustainability (Boyle et al., Citation2021).

Strategic planning offers high potential for promoting inclusion and just transitions and strengthening regional governance in regional transformations by applying cross-sectoral, multi-scale and place-based approaches, developing novel formats of knowledge co-production, and addressing the intermediation gap (see section 2.1).

Albrechts (Citation2015) defines strategic spatial planning as an approach that aims for a coherent and coordinated vision to frame an integrated long-term spatial logic and to promote multilevel governance. Like the concept of transformative capacity, strategic planning is based on the assumption that collaborative forms of learning are more important than the capacity of individuals to innovate. Furthermore, both approaches postulate that open and reflexive processes are needed to convince regional actors across sectors to change existing problem definitions and mentalities and to understand endogenous potentials in order to strive for new goals (Christmann et al., Citation2020).

Transformative strategic planning seeks to incorporate: (1) multilevel, cross-scale and cross-cutting linkages to design effective systemic approaches; (2) a place-based, shared and inclusive vision to guide decision-making; (3) integration of different transformation actors as a source of learning and experimentation; and (4) strengthening of synergies between implementation and innovation capacities (Albrechts, Citation2004; Wolfram et al., Citation2019).

The strategic planning approach has often been used for regions undergoing structural change (Kühn, Citation2008). Strategic planning is often seen as bridge between grand plans and incremental implementation. However, difficulties in implementation arise from the necessary balancing of long- and short-term development, as well as from overall concept and place-based requirements, the need for compromise between various actors, or between hierarchical and network-based governance (Healey, Citation2006). An important criticisms of strategic planning approaches is that visions lose strength when their outcomes turn out to be non-specific and abstract, leaving wide room for interpretation, or when it is difficult to develop a consensus on a new long-term regional profile (Albrechts, Citation2015; Kühn, Citation2008). Consensus-based visioning becomes particularly problematic when difficult regional challenges are bypassed in favour of flagship projects that, while consensual, can create oasis effects and ‘dry up’ other areas (Kühn, Citation2008). Even if structural change requires the participation of various stakeholders, difficulties arise from a dominance of economic or political elites in the visioning process (Albrechts, Citation2015; Haughton, 2020). Similarly, the establishment of intermediaries and new governance arenas can create conflicts with existing administrations, and unclear ownership of strategic planning may hinder the process.

In summary, strategic plans (and planning processes) are appropriate instruments for collective problem perception regarding trends and challenges facing the region, and their influencing factors. They show where actors involved in planning perceive potential for action in order to respond to exogenous influences and trends with the support of endogenous potential and they illustrate perceived transformative capacities from the point of view of the actors involved.

A special characteristic of strategic planning in coal regions is the challenge of having to deal with fragmented actor structures. Decision-making power is usually situated in urban centres, and their actors often have less interest in and understanding of the challenges peripheral areas face, as well as limited knowledge of relevant transformative actors. The perception of challenges, potentials for action and strategies can vary significantly depending on the actors involved and the type of planning process. Building intermediaries therefore seems to be a key for supporting collective learning processes in the acceleration phase in coal phase-out regions (Kivimaa et al., Citation2019).

3. METHODS

Based on the concept of transformative capacity, we concentrate on the development of regional governance and strategic planning approaches for policy-led clean energy transitions. This distinguishes our analytical focus from classical transition approaches, which emphasise innovation and innovation actors.

In section 4 we analyse the interplay of different governance levels and actors and the role of strategic planning in the two case studies in Ústí Region and Lusatia. Our comparative analysis of the case studies will provide us with insights into aspects of transformative capacity in the case study regions as well as barriers and challenges to the strategic development of path-deviant change. The selection of these two coal regions, whose development trajectories are anchored in different institutional environments and framed by different political discourses, will allow us to focus on selected specific aspects related to the Just Transition and its implementation. In addition, the comparison will allow us to look at individual steps related to building capacity for transformation in the past. We adopt the transformative capacity as our analytical framework, focusing on the following:

Multilevel governance context: We analyse discourses, decisions and framework settings of phase-out processes at European and national levels and a state’s regional development strategies as stewarding capacities.

Regional governance as orchestrating capacities: We explore the regional governance structures, in the form of main stakeholders, institutional structures, intermediaries and discourses, in order to analyse cross-sectoral and cross-domain connectivity and inclusivity. We also study the socio-economic context, including the state of the coal industry and main arguments in the discursive setting.

Strategic planning approaches as strategic alignment: We pay special attention to strategic planning for transition processes and its linkage to ongoing processes. We also explore all forms of mediation and collaboration to analyse transformative leadership and social learning.

We take a two-step approach to our analysis. We use data and information from the literature, strategic policy documents and discourses as well as aggregated statistical data for a content analysis to describe the regions and the planning process and milestones of the phase-out process, analysing this using a transformative capacity lens. Document analysis concentrates on the identification of transformative capacities and the governance of transformation processes in relation to strategic planning with the focus on the role and barriers of strategic spatial planning in processes of Just Transition. We analyse national and regional policy papers and regulations as well as formal plans and programmes, and regional studies between 2016 and 2021, in the context of previously published key policy documents, for example, Czechia’s State Energy Policy. We examined strategic documents from a multilevel governance perspective regarding the development of topics and visioning in the transformation process.

In addition, we analyse background information from policy events and their documentation and use observations and semi-structured interviews with actors at different levelsFootnote1 to explore aims, strategies and conflicts in the ongoing strategic planning processes in the regions. Minutes from meetings and published information about the process were used as additional sources, especially regarding the involvement of key stakeholders. Additionally, authors observed meetings of the Czech Coal Commission and its working groups since 2019 at national level as well as the Czech (trans-)national events of the Initiative for Coal Regions in Transition occurring in Ústí Region. The document analysis in Lusatia was complemented by consultations at the state level, by observations of meetings, by interviews and consultations at the regional and the local level. Thereby, preliminary findings were verified and supplemented via interviews with regional and national stakeholders on both sides.

4. CASE STUDIES: ÚSTÍ REGION AND LUSATIA

4.1. Ústí Region, Czechia

Lignite plays a key role in the Czech energy mix and accounted for a 40.4% share of electricity generation in 2019. Lignite mining is concentrated in the north Bohemian and Sokolov Basin in Ústí and Karlovy Vary Regions (). The current long-term energy policy has not set a deadline for achieving a coal phase-out, but uses 2050 as a general policy frame of reference (Ministry of Industry and Trade, Citation2014).

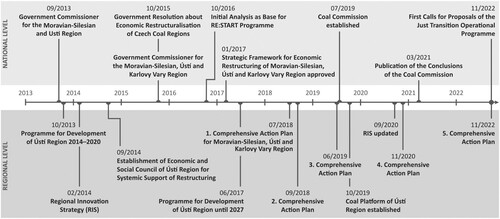

Figure 2. Milestones of the Ústí Region’s transformation process.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The Ústí Region, an area of 5339 km2 with 820,789 inhabitants concentrated around the lignite basin, has a higher population density than the Czech average (Czech Statistical Office, Citation2019). Besides lignite mining and the energy sector, Ústí Region has a long tradition in heavy and chemical industries and was already hit by a strong gale of industrial transformation in the 1990s. The Czech industrial regions withstood the recent financial crisis of 2008–09 and in socio-economic terms performed similar to other Czech regions (Ženka & Slach, Citation2018). However, it is expected that the transition from lignite to other energy sources will be particularly difficult for Ústí Region because of its employment structure; around 9600 people are employed in the region’s mining industry (Czech Statistical Office, Citation2019).

Ústí Region is facing many structural problems and lags behind other regions in several socio-economic indicators. Even in the last years when the unemployment rate in Czechia was very low, Ústí Region retained a high unemployment rate. The low growth of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita shows the divergent trend in the country, where economic disparities between peripheral (underdeveloped) and core (developed) regions are rising (Šimon, Citation2017). The region has one of the highest crime rates, the lowest rate of university education, the highest level of indebtedness and a significantly lower innovation intensity (Czech Statistical Office, Citation2019; European Commission, Citation2019b).

Only since introduction of the EU Green Deal topics have come up for discussion in connection with the coal phase-out, such as the importance of economic transformation, the impact of new regulations on the region’s economic structure and the need to address suitable carbon-free alternatives to the current traditional industrial sectors.

4.1.1. National strategies

The current strategic documents on energy policy (the State Energy Concept and the National Energy and Climate Plan) would not ensure the emission reduction obligations resulting from the Paris Agreement. Therefore, a controlled coal phase-out is likely to be the key instrument to meet international obligations.

In July 2019, the Czech government established a Coal Commission along the lines of the German model (see section 4.2). This body has 19 members from a range of institutions, including representatives of national ministries, regional authorities, energy companies, trade unions, researchers and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The aim of the commission was to formulate a recommendation by March 2021 regarding the timetable for phasing out coal in Czechia and to prepare several scenarios for this purpose. Although the commission proposed a coal phase-out in 2038, the Czech government officially took note of the developed scenarios of diversification from coal, but has not yet decided on an exit date. There is no progress in this issue since change of government in 2021.

The COVID-19 crisis and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with its economic and social consequences, has restructured the political discourse on energy, climate policy and the coal phase-out. In 2020 and 2021, the political debate focuses mainly on the management of the pandemic and measures for economic recovery, which has eclipsed discussion of coal phase-out. Key political leaders have criticised the high cost of climate policy in times when economic recovery must be the top priority. In 2022, Russian aggression against Ukraine fuelled the discussion about the need for energy security even at the cost of the continued use of fossil fuels. This is the indication that key actors in the Czech economy recognise neither the depth of transformation required to meet the country’s climate targets nor the urgency of this task. This general discourse on the path and priorities of economic recovery in conjunction with rising electricity and natural gas prices influences the work of the Coal Commission.

The phase-out strategy is influenced by the general discourse on Czech energy policy. The government has declared that its priority is long-term energy self-sufficiency which is now achieved in energy supply and is highlighted as one of the strengths of Czechia (e.g., Ministry of Industry and Trade, Citation2014). The current political consensus is to replace coal-based energy with nuclear energy, with a limited emphasis on other alternatives such as renewable energy and natural gas. The strategic planning of the transition process at the national level can be described as a top-down process. Regional interest groups are only formally consulted in working groups of the Coal Commission, with limited involvement in the design of the framework for public intervention, including the use of public subsidies.

In addition to the Coal Commission, the government established the Office of the Government Commissioner for the Moravian–Silesian and Ústí Regions in 2013 (and since 2015 for Karlovy Vary Region as well) under the Ministry of Regional Development. Through the Office of the Government Commissioner, the three most affected regions have requested financial and strategic support to restructure their regional economies. The government declared its awareness of the problems in these structurally disadvantaged regions and made a commitment to support them in its economic restructuring strategy. This was implemented in the RE:START programme, which aims to revitalise these regions in seven thematic areas. The Strategic Framework for Economic and Social Restructuring of the three regions (Ministry of Regional Development, Citation2016) was created based on a macroeconomic analysis and interviews with key stakeholders. The RE:START programme was not designed specifically for the coal phase-out, but for more systematic support of regions undergoing structural change and lagging behind other Czech regions. Nevertheless, it plays an important role in the process of just transition.

Based on this framework, Comprehensive Action Plans (CAPs) (2017–22) are prepared and approved by the government every year. These plans contain concrete measures or projects for individual thematic areas, to which the responsibilities of individual ministries and other state administrative bodies are assigned. The current debate over coal phase-out is associated with the EU Just Transition Fund (JTF), which is intended to respond to the needs of ‘regions and sectors that are most affected by the transition due to their dependence on fossil fuels … and on greenhouse-gas-intensive industrial processes’. In 2022, the operational programme for Just Transition funded from the EU JTF (with allocation over €650 million for the Ústí Region) was approved by the European Commission. The programme is officially managed by the Ministry of Environment, but it was developed with direct involvement of representatives of regional authorities and RE:START programme who prepared underlying regional Territorial Just Transition Plans. Therefore, the Ministry of Regional Development has a key coordinating role in strategic planning and has organised several multi-actor meetings within the Czech Transition Platform (including representatives of ministries, chambers of commerce and business associations, regions and regional partners) in 2020 and 2021.

4.1.2. Regional strategies

Strategic documents at the regional level correspond to the programming periods of the EU as financing from European Structural and Investment Funds is a key source of funding for Czech regional policy (Dyba et al., Citation2018).

The topic of transition to a low carbon economy gradually penetrates regional strategic documents, usually as one of the threats to the region that should be taken into account. While this process was not considered in the document for 2008–13 (SPF Group, Citation2008), the strategy for 2014–20 already mentions uncertainty and unclarity regarding further development of lignite mining limits and an unclear national energy concept as one of the threats for regional development (SPF Group, Citation2012). In the new strategy until 2027 (SPF Group, Citation2017), the lack of political clarity over the region’s future position on key economic issues (lignite mining, energy, industry) appears among the most significant threats, which is associated with an expected decline in employment in the affected sectors. Proposed measures and priorities have evolved similarly. While the first strategic document mentions general support for innovation and competitiveness, those for the next two periods explicitly address environmental and infrastructural sustainability, for example, by increasing energy diversity. Only the latest document directly mentions regional economic modernisation in the context of a transformation process. The Regional Standing Conference, including multi-sectoral regional social and economic partners, is responsible for the development and implementation of the yearly action plan.

Support for the region’s innovation potential in relation to the ongoing economic transformation is elaborated within the Regional Innovation Strategy (RIS) (Ústí Region, Citation2019), which deals with supporting innovative impulses for the economy connected with transformation of the regional economy. The managing authority for the RIS is the Regional Competitiveness Council, an advisory body of experts from business, research and the public sphere, and a manager responsible for executive management.

Inputs from these two strategies, together with the RE:START programme’s Strategic Framework for Economic Restructuring, form the basis for the Territorial Just Transition Plan for the transformation of Ústí Region in cooperation with key regional partners. The plan for Ústí Region represents a comprehensive regional transformation strategy and focuses on economic (diversification, innovation), environmental (decarbonisation, land rehabilitation) and social (education, social cohesion) dimensions. The development of this plan was a necessary step in the establishment of the Czech Just Transition Operational Programme. Although this fund is managed centrally it represents a significant empowerment for the coal regions, which are responsible for its prioritisation, including strategic flagship projects in the regional strategic documents and also implementation of groups of project schemes, which represents grants for municipalities and small and medium enterprises to support preparations their transformational projects.

It seems that phase-out is being conceptualised as a top-down process in which the central government plays the key role. However, there is an evident effort to take into account decisions with conclusions of the Coal Commission, as a multi-actor and multilevel advisory platform.

On the one hand, regional authorities from Czech coal regions, including Ústí Region, participate in the preparation of strategic plans for transition. On the other hand, it is evident that not all key strategic planning documents at the national and regional levels are fully aligned in the context of regional change in relation to the coal phase-out.

It is evident that a fixed date and an outline of the phase-out process are important to set the framework for strategic planning at all levels of administration, but politically the discussion of coal phase-out is very sensitive. Whereas there was political willingness to address this issue at time of economic prosperity, it is unclear how political discourses will change in the economically more difficult post-COVID-19 situation and in times of Russian aggression against Ukraine.

4.2. Lusatia, Germany

The Lusatian mining area is one of three active coal mining areas in Germany. However, the coalfield itself is only a small part of the entire region. Currently, around 7000 people are employed directly in the coal industry around the four open-cast mines and three power stations (Statistik der Kohlenwirtschaft, Citation2021, Citation2020), producing around 40% of Germany’s lignite (Staatskanzlei Brandenburg, Citation2020). Lignite in general has a total share of 18.8% of the national energy mix (Destatis, Citation2022).

Lusatia is a region of 11,727 km2 with about 1.1 million inhabitants and is sparsely populated in many parts (Destatis, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The size of the region, its location between Berlin and Dresden, its distribution across two Länder (federal states of Brandenburg and Saxony) as well as its borders with Poland and Czechia result in a high degree of heterogeneity of the territory ().

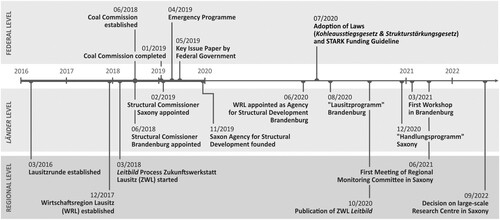

Figure 3. Milestones of the Lusatia transformation process.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

The heyday of lignite began in 1957 with the decision to develop Lusatia as the coal and energy centre of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) (Baxmann, Citation2004). The peak was reached in 1988 with 15 active open-cast mines and around 80,000 employees (Statistik der Kohlenwirtschaft, Citation2020, Citation2020a). This industrial upswing led to a large increase in the population and importance of the region. However, the East German coal industry lost much of its significance under the new energy policy after reunification. In the 1990s numerous mines and power stations were closed, which resulted in a drastic reduction of the workforce and high outmigration. This sharp population decline has been followed by persistent outmigration, especially among the younger generation, leading to brain drain and a severe shortage of skilled workers. This shrinking process, coupled with lagging infrastructural development, creates unfavourable conditions for the upcoming transformation process in the region. Nowadays, Lusatia has been identified as the region in Germany whose economy and living conditions will be most severely affected by the coal phase-out.

4.2.1. National strategies

To support the clean energy transitions and achieve the nationally determined contribution set out in the Paris Agreement, the German government set up the Commission for Growth, Structural Change and Employment (Coal Commission) in June 2018. The aim was to draw up an action programme for Germany’s coal phase-out in cooperation with actors from politics, industry, civil society, research, trade unions and representatives of those affected in coal-producing regions. The political decision to phase out coal in Germany has unleashed a change dynamic in Lusatia and at the same time provides an opportunity for a sustainable transformation of the region.

The final report of the Coal Commission contains both cross-regional actions on climate protection, the energy market, security of supply, and value creation and employment as well as concrete perspectives for the individual coal regions. It stipulates a final German coal phase-out date of 2038 (BMWi, Citation2019). As a direct response to the commission’s work, a €260 million emergency programme for the regions concerned was adopted to implement initial projects (Landesregierung Brandenburg, Citation2019). Political debates about an earlier coal phase-out continue after this was brought forward to 2030 in the western German Rhineland and the coalition of the national government is still struggling to find the right course to accelerate the fight against accelerating climate change (Landesregierung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Citation2023).

In May 2019, the federal government published a key issues paper based on the reports of the Coal Commission, which defines priority projects and guiding principles for the different regions. At the same time, it prepared the implementation of the commission’s recommendations by means of a Strukturstärkungsgesetz (Structural Strengthening Act; BMWi, Citation2019a), adopted in July 2020, that established a binding framework for structural policy and financial resources for public investments and projects for the regions. It thus seeks to incentivise investment in a transformation towards sustainability, initiated by the federal government. The law envisages a sum of €40 billion, of which around €17 billion is to flow into Lusatia (BMWi, Citation2019b). Furthermore, the Kohleausstiegsgesetz (Coal Exit Act) of the same date legally enshrined the gradual phase-out of coal-based power generation (Bundespresseamt, Citation2020) and the ‘STARK’ programme (BMWi, Citation2020) provides financial support for regional strategic planning. With these legal agreements, responsibility for structural change was shifted to the Länder and regions, while the federal government assumes a coordinating role within the Bund-Länder Commission set up in August 2020.

4.2.2. Regional strategies

The challenges of phasing out coal are particularly evident in the continuing high level of identification with lignite in Lusatia. Furthermore, the coal industry offers high salaries and is strongly linked to the regional economy. There is also dissatisfaction with the ambiguities of the phase-out process. Criticism is expressed regarding the questions of which parts of Lusatia are really affected by the coal phase-out and how the heterogeneity of the region should be dealt with. Not only is the political discourse divided over the necessity, extent and speed of the coal phase-out, but so is popular discourse.

The discourse on the strategic development of Lusatia was developed in (1) the perspectives set out by the Coal Commission and the resulting key issues paper and (2) through the process of defining a Leitbild (strategic vision) by the Zukunftswerkstatt Lausitz (Lusatia Future Workshop – ZWL). However, the strategic frame is defined in the legally required action programmes of the Länder, which Saxony and Brandenburg developed separately, after the joint ZWL Leitbild process in Lusatia. It is particularly striking that the strategies have so far been elaborated only at the government level and innovative local actors have only had marginal involvement in the process.

The ZWL was a process funded by the federal and state governments and coordinated by the regional economic development association of the Lusatian districts (WRL). With the publication of a Leitbild for Lusatia by the end of 2020, the ZWL had established the necessary strategic priorities in different domains. The approach to strategy formation was based on a series of civic participation exercises and studies by external experts.

Notwithstanding, the ZWL Leitbild process was subject to some difficulties, in particular due to the lack of public participation in the process. The participation events were only poorly attended. At the same time, the writing of the Leitbild was dominated by municipal actors. It missed the chance to create a learning process by connecting to the experts who conducted thematic studies and could offer knowledge and networks of actors.

Both the preparation and implementation of the development strategies have entailed the region establishing a governance structure to successfully undertake the transformation process. In Brandenburg and Saxony, commissioners have been appointed as coordinators for structural change and heads of organisational units. A cross-state coordination would be desirable in order to achieve joint implementation of the transformation strategies but is proving difficult because both Länder have established different institutional structures. The WRL was an important cross-border institution for Lusatia until the completion of the Leitbild, but was transformed into Brandenburg’s agency for structural development in Lusatia in June 2020. At the same time, Saxony founded its own structural development agency. It is becoming clear that the Länder play the dominant role in setting the framework for governance, which makes region-building in the sense of mentally overcoming the administrative border difficult and poses challenges for coordination of cross-border strategies and projects.

In addition, the Länder have developed their own strategic frameworks for the administration of structural change funds, which have precedence over and stand parallel to the joint ZWL Leitbild. The decision-making process for the implementation of the project-oriented programmes takes place in both Länder through the submission of project proposals and their approval by the structural development agencies since 2021. In Brandenburg, the proposals must pass a workshop process before a decision is made by the responsible ministry; in Saxony, a regional monitoring committee approves the funding of projects. In this context, transparent and participatory decision-making is more successful in Brandenburg, as five thematic workshops have been set up here, which allow for an in-depth professionally and regionally focused exchange. In Saxony, the regional monitoring committee suffers from high complexity and time pressure. Furthermore, it was decided in 2022 to establish a large-scale research centre in the Saxon part of Lusatia. This decision has largely been taken at government level. There was no substantial involvement of the regional authorities or the regional monitoring committee. Joint coordination and decision-making in the transformation process are thus limited to bilateral consultations and an annual conference (Staatskanzlei Brandenburg, Citation2020). The integration of the municipalities in these governance structures has not been finally resolved.

The discourse on transformation and the strategy documents at Länder level show a concentration on economic policies to promote industrialisation, job creation and the implementation of infrastructure projects. However, since the management of structural change has so far also been perceived more as the task of the economy ministries and state chancelleries as overarching actors, this focus is not surprising. While the ZWL’s Leitbild process addresses a broader range of topics and could promise alternative development prospects, it is subject to the difficulties mentioned above and remains a rather multi-thematic Leitbild with little spatial reference, rather than an integrative coherent strategy.

The process of strategic planning for the coal phase-out in Lusatia shows some gaps, especially in the coordination between Länder, regions and municipalities, the jumble of management approaches, and the lack of an integrated and coherent strategy. A network of municipalities (Lausitzrunde) founded in 2016 is trying to represent municipal interests and the need for cross-state cooperation in the affected core region to the federal state governments of Brandenburg and Saxony. Although the strategic planning has led to negotiations and learning processes in the region, a shared vision and a consistent cross-border governance structure for future development has not yet been established. Rather, there is a risk of perpetuating administrative fragmentation and parallel structures.

5. DISCUSSION

With the phase-out of coal mining by 2038 in Germany and a similar attempt in Czechia, a far-reaching structural change process has been initiated by both governments (and not just centred on the transitions in the energy sector). As these are to be achieved within mid-range time frames, they provide an important opportunity to develop strategies for sustainable transformation in lignite regions. However, the coal phase-out is currently perceived as an opportunity and a challenge in each country for different reasons.

5.1. Framework conditions

Both regions have an unfavourable starting point. Since the 1990s, the coal regions in eastern Germany and Czechia have been undergoing structural change characterised by peripheralisation tendencies in form of outmigration, decoupling, brain-drain and economic decline. In comparison with urban areas where sustainable transformations are often welcomed as an improvement of the quality of life, previous experience of structural collapse and reorientation in the two analysed peripheral region have given rise to fear of further change in recent decades.

For both regions, setting a phase-out date is important as a framework for transformation, as it has or will have an impact on regional governance structures and strategic spatial planning activities in the regions (as stewarding capacities, see Hölscher et al., Citation2019b). As these are politically induced transitions, the federal (Germany) and national levels are also important in setting the framework for transformation, by establishing coal funds, co-financing of projects, or decentralising federal institutes or ministries into the regions.

However, there are differences in the dynamics of these regional transformations. Only in Germany, the phase-out regions entered the acceleration phase and are confronted with a very dynamic process of institutionalising regulations, programmes and organisational structures to enter the transformation process (Kivimaa et al., Citation2019). In contrast, the phase-out process in Czechia was only beginning to be negotiated when COVID-19 hit Europe. As a result, the issue is less institutionalised and more affected by the crisis: debates over the necessity of coal phase-out have begun and the discussion process has been suspended for the time being.

Energy transitions in Czechia and Germany are currently taking place through an interplay of multiple levels, but remain dominated by a top-down approach of hierarchical governance, with the nation states acting as initiators and thus responding to their obligations under the Paris Agreement. Yet the phase-out initiatives are embedded in different institutional frameworks; a more centralised structure in Czechia and a federal structure in Germany, which leads to federal actors having a stronger voice in Germany. According to theoretical approaches to transformative capacity this is often lacking a mediation across scales and sectors and inclusive forms of collective learning that include transformation-oriented actors and strategies (Hölscher et al., Citation2019a; Wolfram, Citation2016;). Furthermore, the case of Lusatia shows that the federal states (as part of the regional level) are blocking innovation by the national level and hindering the development of transformative capacities by dominating and controlling resources and coordination structures. Also, if not oriented to a shared vision, the regional actors get lost in distribution conflicts at great cost to the clean energy transition’s potential success. The centralisation of transition planning in the energy sector in Czechia (for instance, the decision over support for nuclear powerplants) contrasts with the decentralisation tendencies associated with the introduction of renewable energy sources. In Germany, the Länder are not only responsible for structural policy, their administrative structures and process organisation can be very different (in terms of policies or vertical and horizontal coordination, for instance). This hinders cross-border coordination and the development of suitable governance structures for the coal phase-out process in Lusatia. However, in both cases the limited personnel, organisational, and financial resources available at local and regional levels limits the regions’ transformative capacity and hinders the activation of endogenous potentials.

In summary, transformative capacity of these coal regions is significantly limited by the following factors:

Current governance structures are far from substantially including municipalities and stakeholders and provide few cross-sectoral coordination.

Local academia has limited involvement, although its multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary expertise gives it great potential as intermediaries in regional contexts.

Monitoring systems and inclusive strategic planning that promote reflexivity and collective learning processes have not yet been developed and deployed and indicate a lack of process and systemic intermediaries (Kivimaa et al., Citation2019). Yet, there is a perceived need for identification and evaluation of strategies for transformation at the national level, which can feed into enhanced reflexivity in the regions.

The application of the transformative capacity lens has shown that its concepts translate well to regional contexts and peripheral regions and can be used to identify where barriers to transformation may lie. In particular, the analysis of unlocking capacities to recognise and dismantle structural drivers of unsustainable path dependencies seems to be an important key for the development of the regions. One assumption for further exploration is that regime actors in peripheral regions have so far played a more important role for the success of transformation than in urban areas, caused by the lack of innovative actors, their need for support in networking and in tapping resources in peripheral regions.

5.2. Strategic planning process

In strategic planning, likewise, transformative capacity is only evident to a limited extent. Collaborative planning processes to develop shared visions as part of transformative leadership are absent or fragmented at the regional level and the potential of spatial planning has not been integrated. Consequently, there is a risk that the lack of shared visions among public, private and civil society actors will hinder joint action and transitions towards sustainable regional pathways and slow down embedding processes of transitions (Kanda et al., Citation2020).

Both countries established a coal commission as a multilevel and multi-stakeholder platform that offers forms of participation for state actors and municipalities, trade unions and environmental interests. These would seem to supplement top-down structures with bottom-up initiatives, but the structures are concerned with establishing the framework conditions for coal phase-outs and need to be supplemented by structures to integrate non-governmental stakeholders, intermediaries, academia and municipalities into the implementation of clean energy transitions. This may limit the impact of the newly designed policies (see orchestrating capacities; Kanda et al., Citation2020). On the one hand, there is a need to further develop inclusive and integrative strategic planning approaches for transition regions and, on the other hand, to carefully embed these strategies in the actual implementation of structural policy.

The EU framework set out in the European Green Deal, the JTF and the Coal Regions in Transition Platform are perceived as important pillars for stewarding the clean energy transitions (enhancing stewarding capacity) and good starting points for political orientation of the phase-out process. In Czechia more than in Germany, planning processes are strongly connected to EU programming periods and high expectations are placed on EU support for regions phasing out lignite as regime-based and systemic intermediaries. Regional strategies are perceived as highly adaptable to funding requirements since the implementation of new approaches is driven by the availability of financial resources from the national operational programmes.

Both countries perceive structural change as multi-domain processes and seek to accompany the coal phase-out with structural policies, although the approaches differ. In Czechia, the restructuring process in the coal mining regions was initiated with the RE:START strategy before debates over the coal phase-out began, while in Germany structural policy is directly linked to the phase-out of coal mining.

In terms of structural policies, the differences are not very pronounced: both make use of rather standard economic programmes and offer support of traditional industries instead of new progressive sectors. Current programmes lack an emphasis on experimentation and innovation, and are thus perceived as regime facilitators that strengthen existing policy and institutional spaces rather than supporting new pathways. Supported projects tend to be reactive and aim at improving existing infrastructures rather than proactively initiating new development paths. Thus, they entrench path dependence instead of enabling a transformation towards sustainability (Dawley et al., Citation2015; Loorbach et al., Citation2017). From a sustainability perspective a closer linkage to circular economy and the aims of the European Green Deal would be advantageous. Currently, there is no discussion of sustainable transformation that goes beyond the mainstream, partly because the economic aspects are particularly important in the regions. These deficiencies can be seen as an indicator of the lack of effective strategic planning in terms of sustainability.

5.3. Regional strategies

Regional identities in mining regions as well as existing networks that are closely linked to coal industry seem to hinder a reorientation of development and changes of pathways in both regions by creating lock-in situations. These might limit the perception of opportunities in the regions that are needed for a change towards sustainable ways of living and working. Therefore, regional planning processes are needed that replace traditional images and combine existing identities with new positive imaginaries, narratives and visions in order to become process intermediaries (Albrechts, Citation2015).

Although regions could be an appropriate level to develop new visions in collaborative, multilevel and cross-sectoral planning processes and to empower actors in transformation processes (Geels, Citation2010; Healey, Citation2006), they are currently poorly empowered to do so. They are caught between the demands of the state and (under-financed) municipalities and have to deal with increasing distribution conflicts within the regions. In doing so, they lack spatial strategies that localise thematic focal points and provide rationales for prioritising funding. Shortcomings of top-down strategies that have failed to address spatial sensitivities and provide answers to spatial issues have become apparent.

In both regions, regional development strategies have not yet achieved the objectives of an inclusive and coherent strategy, co-produced by regional actors and functioning as a shared future vision in order to foster strategic alignment. While in Lusatia, the ZWL Leitbild is juxtaposed with the programmes of the individual Länder, Ústí lacks a long-term vision and ideas for a possible post-coal profile for the region. There is a clear need to link regional development, structural policy and strategic planning more closely in both countries. The theoretical concepts show that a more integrative process of developing those strategic programmes could help tap transformative capacity and dismantle drivers of unsustainable developing paths (Wolfram et al., Citation2019).

Historically, there is a deficit in the involvement of civil society and other socio-economic partners in decision-making processes in both regions. The involvement of civil society in strategic planning is rather more top-down driven (by appointment of individual representatives) than bottom-up. It does not support collaborative and multi-stakeholder learning or wider societal involvement and thus does not result in mutually shared views and agreement on the best pathway to regional transformation.

Nevertheless, limitations in the application of the theoretical concepts of transformative capacities become apparent. The case studies have shown that the concepts of transformative capacity are useful analytical tools to identify drivers of unsustainable development and to analyse weaknesses in the governance of the process. However, it appears necessary to complement the approach with the phases of transition and the needs for intermediation in order to concretise the needs and approaches for strengthening transformation capacity in terms of time (Kivimaa et al., Citation2019; Rotmans & Kemp, Citation2001). In addition, more in-depth research is needed to conceptualise how transformative capacities can be strengthened in peripheral regions, where consensus on the nature and dynamics of transformation is difficult to establish and change is perceived more as a threat from outside than as a desirable and endogenous force for the region’s development. The concept of transformative capacity needs to be adapted to include aspects of just transformation, cohesion and social acceptance of transformation. Strategic planning and spatial visions can play a central role in this process if they are embedded in integrative regional governance and practices of experimenting (Matern et al., Citation2022a).

6. CONCLUSIONS

The case studies show that structural change is a rather dynamic and political process. The shift towards more sustainable development paths requires transformative capacities which are found in multilevel governance structures and processes of visioning, reflexivity, and negotiation of strategies. The discussion of the literature revealed the potential of strategic planning approaches for analysing and enhancing transformative capacities in regions. However, analysis of the coal phase-out regions demonstrated that these potentials are not being tapped. Instead of long-term integrative planning, short-term strategic approaches to structural policy are applied that do not provide any spatial anchoring or embedding and only offer limited opportunities for participation.

Regional development needs to be done on the basis of coherent strategies that go beyond the management approaches practised so far. Collaborative strategic planning processes could support this development with new visions and orientations in the regional transformation processes. They can initiate and promote new networks that bring together regional stakeholders for sustainable transformation. Institutions responsible for regional development, as territorially oriented initiators or supporters of endogenous development, should also more strongly involve actors from the private sector, academia, and intermediaries in strategy coordination and implementation. The process in Germany illustrates the pitfalls of running the just transitions as a public funding guideline with inadequate attention to establishing a governance process appropriate to its transformative aims. This leaves it vulnerable to co-optation by state (Matern et al., Citation2022b).

Both transformation and spatial research should further investigate the obstacles to unlocking the prerequisite capacities to effect meaningful transformations in coal regions. Regardless of whether the obstacles are to be found in current mindsets, contrary logics of action or governance structures, it seems necessary to dedicate more attention to these obstacles in strategic planning and to link spatial strategic requirements to EU Just Transition policies.

The two case studies highlight the need for greater consideration of space in sustainability research, in terms of the socio-economic context, the political and governance context as well as identities and regional narratives. These region-specific characteristics influence their transformative capacities and are of great importance both for the dynamics of change and for the strategic design of transformation processes. The Platform for Coal Regions in Transition is a good starting point for creating learning networks to reflect on strategies, frameworks and outcomes, but would benefit from closer links with networks from science and research or other intermediaries of change.

The experiences from the two coal phase-out regions in different national contexts show that the concept of transformative capacity is well suited to analyse potentials and gaps in regional governance and strategic planning. To empower regions to act independently towards sustainability transformation, the components of transformation capacity, especially strategic alignment, establishing intermediaries to coordinate sectors and scales, and orchestrating capacities should therefore be further researched. Especially in the current acceleration and embedding phase, these elements should be taken more into account, for example, in supranational policymaking processes and intergovernmental alliances dealing with climate and energy transition, such as the EU JTF or the IPCC and its working groups, in order to accelerate processes of change. To successfully promote a policy that ‘leaves no one behind’ requires in particular a further development of the strategic foundations for transformations: it necessitates integrative and holistic strategies as a political framework for action that are created in inclusive and co-productive processes and thus invite regional actors from science, business and civil society to co-design the processes and be taken into account during implementation.

Still, for practical application, the concept of transformation capacities should be further developed in such a way that researchers (and policymakers) better understand synergies and interdependencies between components. Moreover, research is required to explore which components constitute necessary preconditions at different stages of transformation, whether certain capacities are more central in certain spatial contexts than others, and what stands in the way of unlocking the capacities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Jiřina Jílková for her engagement and contributions to this article. Her knowledge and deep insights into the work of the Coal Commission in the Czech Republic have been an essential building block for the content of the article. Sadly, she passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in June 2022.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In accordance with the regulations of the ethics committee of TUD Dresden University of Technology, interviews with official representatives are not subject to approval by the committee. We confirm all interview partners provided their consent at the beginning of the interviews.

REFERENCES

- Albrechts, L. (2004). Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environment and Planning B, 31(5), 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3065

- Albrechts, L. (2015). Ingredients for a more radical strategic spatial planning. Environment and Planning B, 42(3), 510–525. https://doi.org/10.1068/b130104p

- Baxmann, M. (2004). Zeitmaschine Lausitz, Vom ‘Pfützenland’ zum Energiebezirk, Die Geschichte der Industrialisierung in der Lausitz, Internationale Bauausstellung Fürst-Pückler-Land, Großräschen.

- BMWi. (2019). Kommission Wachstum, Strukturwandel und Beschäftigung – Abschlussbericht’.

- BMWi. (2019a). Eckpunktepapier zur Umsetzung der strukturpolitischen Empfehlungen der Kommission ‘Wachstum, Strukturwandel und Beschäftigung’ für ein ‘Strukturstärkungsgesetz Kohleregionen’.

- BMWi. (2019b). Entwurf eines Strukturstärkungsgesetzes Kohleregionen. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/E/entwurf-eines-strukturstaerkungsgesetzes-kohleregionen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=12.

- BMWi. (2020). Förderrichtlinie zur Stärkung der Transformationsdynamik und Aufbruch in den Revieren und an den Kohlekraftwerkstandorten ‘STARK’, bundesanzeiger.de, 1–12.

- Boyle, E., Watson, C., Mullally, G., & Gallachóir, BÓ. (2021). Regime-based transition intermediaries at the grassroots for community energy initiatives. Energy Research & Social Science, 74, 102134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102134

- Bundespresseamt. (2020). Abschied von der Kohleverstromung. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/kohleausstiegsgesetz-1716678.

- Castán Broto, V., Trencher, G., Iwaszuk, E., & Westman, L. (2019). Transformative capacity and local action for urban sustainability. Ambio, 48(5), 449–462. http://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1086-z

- Christmann, G. (2010). Kommunikative Raumkonstruktionen als (Proto-)Governance. In.

- Christmann, G., Ibert, O., Jessen, J., & Walther, J.-U. (2020). Innovations in spatial planning as a social process – phases, actors, conflicts. European Planning Studies, 28(3), 496–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1639399

- Czech Statistical Office. (2019). Statistical yearbook of the Ústeckého region 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.czso.cz/documents/10180/91195091/33008519.pdf/e6a27c6a-7b81-4665-b61b-d01d269102d9?version=1.11.

- Dawley, S., MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., & Pike, A. (2015). Policy activism and regional path creation: The promotion of offshore wind in north east England and Scotland. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- Destatis. (2020a). Gebietsfläche. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=11111-0002&levelindex=1&levelid=1588579606819.

- Destatis. (2020b). Bevölkerung. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=12411-0015&levelindex=1&levelid=1588580738537.

- Destatis. (2022). Energie, Erzeugung. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https:www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Energie/Erzeugung/_inhalt.html;jsessionid=6899F95BE430460664CDCF7B4003EAF3.internet8731#sprg236386.

- Dyba, W., Loewen, B., Looga, J., & Zdražil, P. (2018). Regional development in central–eastern European countries at the beginning of the 21st century: Path dependence and effects of EU cohesion policy. Quaestiones Geographicae, 37(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.2478/quageo-2018-0017

- European Commission. (2017). Platform on Coal and Carbon-Intensive Regions. Terms of Reference. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/crit_tor_fin.pdf.

- European Commission. (2019a). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, The European Green Deal. COM (2019) 640 final.

- European Commission. (2019b). 2019 European Semester: Country Report – Czech Republic. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/2019-european-semester-country-report-czech-republic_en.pdf.

- Fornahl, D., Hassink, R., Klaerding, C., Mossig, I., & Schröder, H. (2012). From the old path of shipbuilding onto the new path of offshore wind energy? The case of northern Germany. European Planning Studies, 20(5), 835–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.667928

- Füg, F., & Ibert, O. (2020). Assembling social innovations in emergent professional communities. The case of learning region policies in Germany. European Planning Studies, 28(3), 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1639402

- Geels, F. (2010). Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Research Policy, 39(4), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.022

- Goerlitz Declaration. (2019). Abschlussdokument von 14 Kohleregionen in der EU anlässlich der zweiten Politischen Jahrestagung der Plattform für Kohleregionen im Übergang am 25.11.2019 in Görlitz mit Empfehlungen an die neue Europäische Kommission [Final document of 14 coal regions in the EU on the occasion of the second annual political meeting of the Platform for Coal Regions in Transition in Görlitz on 25.11.2019 with recommendations to the new European Commission]. https://www.medienservice.sachsen.de/medien/medienobjekte/126349/download

- Grillitsch, M., & Hansen, T. (2019). Green industry development in different types of regions. European Planning Studies, 27(11), 2163–2183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1648385

- Hajer, M., & Versteeg, W. (2019). Imaging the post-fossil city: Why is it so difficult to think of new possible worlds?. Territory, Politics and Governance, 7(2), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1510339

- Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning. Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies.

- Healey, P. (2006). Transforming governance – challenges of institutional adaptation and a New politics of space. European Planning Studies, 14(3), 299–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500420792

- Heer, S., Wirth, P., Knippschild, R., & Matern, A. (2020). Guiding principles in transformation processes of coal phase-out. The German case of Lusatia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 8(1), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.07.005

- Herberg, J., Gabler, J., Gürtler, K., Haas, T., Staemmler, J., Löw Beer, D., & Luh, V. (2020). Von der Lausitz lernen: wie sich die Nachhaltigkeitsforschung für Demokratiefragen öffnen kann. GAIA – Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 29(1), 60–62. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.29.1.13

- Hodson, M., Marvin, S., & Bulkeley, H. (2013). The intermediary organisation of low carbon cities: A comparative analysis of transitions in Greater London and Greater Manchester. Urban Studies, 50(7), 1403–1422. http://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013480967

- Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Mc Phearson, T., & Loorbach, D. (2019a). Steering transformations under climate change – Capacities for transformative climate governance and the case of Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Regional Environmental Change, 19(3), 791–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1329-3

- Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Mc Phearson, T., & Loorbach, D. (2019b). Capacities for urban transformations governance and the case of New York city. Cities, 94, 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.037

- Innes, J., & Booher, D. (2003). The impact of collaborative planning on governance capacity. IURD Working Paper Series. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/98k72547.

- Kanda, W., Kuisma, M., Kivimaa, P., & Hjelm, O. (2020). Conceptualising the systemic activities of intermediaries in sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 36, 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.01.002

- Kemfert, C. (2019). Green deal for Europe: More climate protection and fewer fossil fuel wars. Springer: Intereconomics, 54(6), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-019-0853-9

- Kivimaa, P., Hyysalo, S., Boon, W., Klerkx, L., Martiskainen, M., & Schot, J. (2019). Passing the baton: How intermediaries advance sustainability transitions in different phases. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31(4), 110–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.001

- Kühn, M. (2008). Strategische stadt- und regionalplanung. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 3(4), 230–243.

- Kühn, M., & Lang, T. (2017). Metropolisierung und Peripherisierung in Europa: Eine Einführung. Europa Regional, 4, 2–14.

- Landesregierung Brandenburg. (2019). 80 Millionen Euro: Sofortprogramm für Lausitz kann starten. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://www.brandenburg.de/cms/detail.php/bb1.c.627164.de.

- Landesregierung Nordrhein-Westfalen. (2023). Kohleausstieg 2030 im Rheinischen Revier. https://www.wirtschaft.nrw/themen/energie/kohleausstieg-2030.

- Lintz, G., Wirth, P., & Harfst, J. (2012). Regional structural change and resilience – from lignite mining to tourism in the Lusatian Lakeland. Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 70(4), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-012-0175-x

- Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340

- Lucchese, M., & Pianta, M. (2020). Europe’s alternative: a Green Industrial Policy for sustainability and convergence, MPRA Paper No. 98705. Retrieved August 21, 2020, from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/98705/.

- Matern, A., Förster, A., & Knippschild, R. (2022a). Designing sustainable change in coal regions. Disp – the Planning Review, 230(58.3), 19–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2022.2158588