ABSTRACT

This paper advances the study of metagovernance by examining its spatial horizons in the empirical case of tourism development. Drawing upon Jessop et al.’s (2008) TPSNE framework on territory, place, scale, network and environment for a longitudinal qualitative analysis, the article traces the evolution of tourism metagovernance in northernmost Finland and Sweden over the past 150 years. The shifts from pre-Fordism over welfare state Fordism to the competition state manifest themselves in tourism metagovernance through distinct socio-spatial relationships between the state, tourism stakeholders and society at large. Applying the TPSNE framework provides crucial explanatory insights into processes and drivers of change and continuity in tourism’s sectoral development as part of wider societal and political transformations.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, metagovernance has advanced to being a popular yet multifariously used analytical lens within the social sciences. Metagovernance generally refers to the ‘governance of governance’ whereby governments set the regulatory and normative order in and through which a wide range of public, private and civil actors can operate (Jessop, Citation2016; Jones, Citation2018). The tourism sector provides an interesting case for an analysis of metagovernance: it includes numerous actors, ranging from global to local levels and from individuals and small-scale businesses to states and supranational actors; it is also often seen as a development strategy with increasing scope, for instance in the European Union (EU), with great impact on the spatial configuration of territory and place (Amore & Hall, Citation2016; Romão, Citation2020; Sörvik et al., Citation2019). Theoretically, the dynamic relations between public and private stakeholders involved in policy, planning and coordination across the social, economic and environmental dimensions of tourism are well recognised (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2011; Farsari, Citation2023). Still, most studies remain stuck within the traditional divide of focusing on either top-down governmental actions or bottom-up initiatives of non-governmental actors in the process of steering tourism (Amore & Hall, Citation2016). The extant literature has thus catered primarily to agency and lower scale – such as businesses – or to formal steering, to the detriment of understanding the metagovernance configurations that shape the ways tourism is undertaken during different time periods. On a general social science level, scholars also acknowledge that metagovernance remains conceptually abstract as there are few empirical insights into what it entails and ‘how it actually works in practice’ (Gjaltema et al., Citation2020, p. 1760).

Combining these two arguments, this paper examines the metagovernance of tourism development in a longitudinal qualitative manner by drawing upon Jessop et al.’s (Citation2008) territory, place, scale, network matrix, adding their mention of environment (E) as a distinct component (TPSNE). The framework reveals the spatial dimensions of metagovernance beyond simple network or scale conceptions (Jessop, Citation2016) in the empirical case of tourism development in northernmost Finland (Finnish Lapland county) and Sweden (Norrbotten County). The aim is to link tourism metagovernance to actual tourism development and thereby advance the governance debate from ‘what is governance’ to ‘what does governance do in space and time’, with a specific focus on the role of the state in opening and closing opportunity spaces for different actors to take part in tourism (Amore & Hall, Citation2016). The paper takes the unusually long timeline of the late nineteenth century to the present, building on a qualitative examination of policy documents and historical secondary sources, supplemented by interviews with current institutional tourism stakeholders. This perspective illustrates the importance of metagovernance analyses for foregrounding and understanding the factors that steer regional development in the example of tourism, by answering the following research questions:

How can the TPSNE framework be applied in a longitudinal qualitative study to illustrate changes in metagovernance?

What are the overarching TPSNE metagovernance configurations that have steered tourism development over time in Finnish Lapland and Norrbotten?

To our knowledge, the study is the first application of Jessop et al.’s (Citation2008) framework in the case of long-term metagovernance development, and it aims to further the understanding of metagovernance by discussing how it transforms in and through geographical space (Jessop, Citation2016; Jones, Citation2018). The tourism case offers plentiful insights into socio-spatial relations, due not only to its prominence in modern consumer culture and regional economic development but also to its role in allowing states to display soft power and identity (Bennett & Iaquinto, Citation2023; Farsari, Citation2023).

2. TOURISM METAGOVERNANCE AND THE TPSNE FRAMEWORK

Metagovernance began gaining popularity in the early 2000s as a lens for analysing the ways in which independent governance arenas are steered to mobilise resources across public-private boundaries in pursuit of certain policy goals (Torfing, Citation2016). Studies emphasise that it is not only governments and managers of public organisations located within different policy fields and scales that can act as metagovernors, but also private actors who hold an authoritative and central role within a network and possess sufficient resources to influence a course of action (Gjaltema et al., Citation2020). Metagovernance therefore builds upon the idea that hierarchical organisation offers the necessary stability for independent self-organisation (Jessop, Citation2016; Soininvaara, Citation2023; Torfing, Citation2016). This paper focuses particularly on the metagoverning function of the state in strategically rebalancing modes of government and governance, in promoting social capital and societal reproduction, and in delegating governance tasks to actors who develop procedures autonomously (Pierre & Peters, Citation2020). Conceptually, this way of thinking is rooted in interdependence theory, which is most notably advanced in the work of Jessop (Citation2016; Citation2019). A key aspect of this approach to metagovernance is the strategic selectivity of (state) governors in privileging specific actors and governance frameworks over alternative options (Torfing, Citation2016).

These metagoverning actions often display a high degree of path dependence anchored in institutional traditions and established power constellations, implying that path-creating change usually happens incrementally (Pierre & Peters, Citation2020). Thus, metagovernance works conventionally to maintain existing systems by employing spatio-temporal fixes. A spatio-temporal fix is a situation-specific solution to socio-economic crises caused by the various economic and political contradictions that are inherent to any state system (Jessop, Citation2016). In the context of metagovernance, spatio-temporal fixes ensure political legitimacy as well as societal stability and revolve around state spatial restructuring to produce ‘a territorially coherent and functioning socioeconomic landscape’, for instance through generating geographical zones or sharing responsibility for development across certain scales and within distinct networks (Jones, Citation2018, p. 29). The major regime shifts from pre-Fordism, over welfare state Fordism, to the neoliberal competition state are often discussed as spatio-temporal fixes (Soininvaara, Citation2023). Servillo (Citation2019) also analyses the passing down of responsibility to local action groups in the context of the EU’s Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) policy initiative as a potential spatio-temporal fix ensuring local-level solutions for regional development.

A further aspect of metagovernance that is evident in this case is the normativity of political decision-making and how certain policy problems are articulated (Pierre & Peters, Citation2020). Amore and Hall (Citation2016) note that the selection of particular interventions is underpinned by values and interests, which in turn reflect power relationships at various scales. ‘Who governs, how do they govern, and what do they govern’ (Hillman et al., Citation2011, p. 409) is therefore intimately connected to ‘who gets what, when and how’ (Lasswell, Citation1936). Overall, Jessop’s (Citation2016, p. 10) approach to metagovernance emphasises its inherently spatial nature whereby physical and socially produced space ‘can be a site, object, and means of governance’. In contrast, most empirical studies focus on collibration processes adjusting the mix of market, network and hierarchy modes of governance in order to tackle certain societal problems, the use of different instruments to govern (e.g., authority, economic power, planning and information exchange), and management coordination within networks (Gjaltema et al., Citation2020). To visualise the complex spatial relations entailed in metagovernance, Jessop (Citation2016) draws upon the TPSN framework. This 4 × 4 matrix includes territory (T), place (P), scale (S) and network (N) vertically as fields of socio-spatial organisation and horizontally as structuring practices in terms of territorialisation, place-making, (re)scaling and networking (Jessop et al., Citation2008). It allows for the analysis of territorial and scalar organisation, networked social interaction, and places as meeting points of ‘functional operations and the conduct of personal life’ simultaneously (Jessop, Citation2016, p. 23). However, Jessop et al. (Citation2008) underscore that the framework can mainly be seen as heuristic, and subsequent empirical studies have modified the TPSN matrix according to the specific application scope, yet mostly limited to a certain point in time (Gailing et al., Citation2020; Gajewski, Citation2022; Jones, Citation2018; Yankson, Citation2024). Jessop et al. (Citation2008) also point out that the four dimensions do not represent all spatial aspects of social relations, and suggest including, for instance, the environment/nature or positionality (Jessop et al., Citation2008, Footnote 5; see also Paasi, Citation2008).

In their work on the socio-spatial characteristics of energy transitions in Germany, Gailing et al. (Citation2020) complement the TPSN with analytical categories related to power and politics exercised by collective actor groups and organisations, discourse, spaces allowing for policy and governance experimentation, and the socio-material world of resources, infrastructure and physical landscapes. Other studies have voiced the criticism that agency remains largely underelaborated in the original TPSN conceptualisation (Paasi, Citation2008). Pajvančić-Cizelj (Citation2022) examines how imaginaries held by decision-makers perpetuate certain TPSN (re)orderings in the case of contentious politics and gender-sensitive urban planning, while Waite (Citation2023) reflects upon the different TPSN configurations emerging from policymakers’ attempts for and against polycentrism as part of economic development in the case of Edinburgh-Glasgow city regions.

We apply the TPSN framework augmented with environment (E) to unpack how the natural world is governed and constructed within a tourism context. The inclusion of environment as a field of socio-spatial organisation and multispatial metagovernance () seeks to challenge the binary opposition between human socio-cultural or economic systems and nature (e.g., Parks, Citation2020). We intend to emphasise not only the dependence of socio-economic processes on the utilisation of natural environments, but also the fact that the ways in which these environments are governed alongside specific territory, place, scale and network ensembles mirror broader historical and institutional developments (Keskitalo, Citation2023). Furthermore, we build on Gailing et al. (Citation2020) to illustrate the dynamic relationships connecting the TPSN components as distinct fields of metagovernance and as structuring actions devised by strategically selective individual and collective actors (termed spatial effects and actions in ).

Table 1. The TPSNE framework.

Regarding the framework’s components, territory (T) signifies, on the one hand, a bounded space that is claimed by a certain group and controlled by a sovereign political authority with respect to internal and external affairs, and, on the other, a social relation (Elden, Citation2010). Territorialisation denotes the corresponding process whereby frontiers and borders are set to contain territory-internal social relations and to mediate them to the outside (Jessop, Citation2019). The spatial effects and actions in relation to territorialisation encompass how metagovernors delimit places, scales, networks and environments, and define how other actors can operate within these boundaries and what actions even become meaningful or possible. For instance, tourism is frequently utilised by states to display presence and soft power influence in national as well as overseas territories (Bennett & Iaquinto, Citation2023).

Place (P) not only refers to an absolute location on the map but is also associated with the geographies of everyday life and identity. The difference to territory is that place, as the material locale of social life, is defined by individual or collective meaningfulness and affective values (Duarte, Citation2017). In terms of spatial action and effects, place-making by states and other actors assigns a purpose to a location by employing specific imaginaries, terminologies and practices rooted in modern or traditional values (Hultman & Hall, Citation2012). Metagovernance for touristic place-making involves – among other processes – the transformation of territories, places and the environment into destinations by differently scaled actors, as well as networked structures (Lew, Citation2017).

Scale (S) highlights the idea of hierarchical and vertical relations between macro (international), meso (nation-state) and micro (local) scales. From a political economy perspective, (re)scaling processes of the state are path-dependent and serve to recalibrate capitalist relations to secure accumulation. They may also include struggles over control by differently positioned actors in order to gain political or economic legitimacy (Brenner, Citation2009). In terms of spatial effects and actions, scaling highlights what types of actors (for instance supranational, state, or marketing actors, or even tourists) can be included in metagoverning territories, places, networks and the environment, and what types of policies become relevant (Farsari, Citation2023).

Networks (N) are understood as nodal market exchange and consensus-oriented cooperation relations seeking to secure the flow of goods, services, people and capital by sharing responsibility between state, private and third-sector actors (Jessop, Citation2019). An example of this is the EU’s attempt to facilitate cross-border networks through INTERREG programme funds for tourism as a governance strategy to encourage regional integration and economic development (Prokkola, Citation2011). In terms of spatial effects and actions, networking highlights how these nodal points and collaborative conglomerates steer actions within territories, places, scales, networks and the environment.

Including the environment (E) as a category makes it possible to identify the environmental resources needed for tourism and the assumptions about nature that underpin the sector’s metagovernance. Tourism is nature-based in many countries or regions, and imaginaries of the environment may play a significant role in constructing possibilities for or limitations to tourism development. At the heart of this lies the modern dichotomy of leisure and work that resulted in the creation of distinct free-time facilities, sharply separated from everyday workplaces, accompanied by time- and space-specific conceptions of what such holiday environments look like and for whom they are designed (Keskitalo, Citation2023). Concerning spatial effects and actions, by using imaginaries of areas as untouched, pristine, or wild (which dominate in nature-based destinations), tourism itself may support an understanding of which environmental actions are (or are not) needed in specific areas (Gammon, Citation2017) and how they are to be governed. This refers, for example, to conservation approaches rooted in the exclusion and dispossession of local land users in favour of high-end ecotourism (Büscher & Fletcher, Citation2015) or neoliberal environmental governance which promotes private market-based instruments, such as certification schemes, instead of top-down regulation (Jordan et al., Citation2013). Environment is added only as a field of governance rather than a structuring principle of governing, corresponding to how it is constructed as an object by the other categories.

While each field in the matrix is central to metagovernance, some structuring principles of the TPSN framework are more dominant than others in different epochs (e.g., Jones, Citation2018). Thus, the role of each of the parts of the TPSNE framework can be elucidated for different time periods, particularly with a focus on identifying the main actors and purposes shaping the construction of space. Shifts between periods in which different actors, networks and spatial constructs are more dominant are typically gradual, and the delineation of different periods in the following findings section should be seen not as a clear break but as an indication of the transforming roles of major principles of metagovernance and their principal actors.

3. CASE STUDY AND METHODS

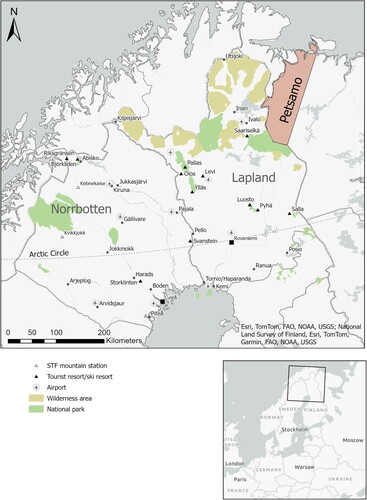

The study examines the two counties Lapland in Finland and Norrbotten in Sweden (). Both regions are large, sparsely populated areas that are ecologically and socially diverse and can be framed in multiple political and economic ways (e.g., Keskitalo, Citation2019). Lapland and Norrbotten are ethnically heterogenous in that they are part of the homeland of the Indigenous Sámi, including several different Sámi groups, as well as having both historically and into the present been inhabited by a variety of other ethnic groups, including Kven and Torne Valley Finns (Keskitalo, Citation2004). This socio-cultural multiplicity is coupled with different forms of land use, including resource extraction (forestry and mining), pastoralism (reindeer herding) and energy production, as well as national interests (defence) and transport and trade connections that have shaped the settlement patterns in both counties (Carson et al., Citation2022). Due to economic restructuring and public service rationalisation from the mid-1960s onwards, urbanisation increased in both Finland and Sweden while population and service provision declined, particularly in small villages around municipal centres where the number of inhabitants overall remained relatively stable. Today, urban hotspots in Norrbotten are located along the coastal areas and around Kiruna, while the administrative centre of Rovaniemi constitutes Lapland’s main population hub.

Figure 1. Main tourist destinations in Lapland and Norrbotten.

Source: Authors.

Although tourism in both regions is largely nature-based and is frequently presented as a more sustainable land-use path than extractive industries, the travel sector in Lapland and Norrbotten is concentrated mainly around urbanised areas, remote resorts and iconic attractions (Müller et al., Citation2020). Another characteristic of the tourism is the diversity of businesses, ranging from domestic and international lifestyle migrant-run micro-firms to larger chains (Bohn et al., Citation2023). Tourism is also embedded into the wider regional development and planning at county, national and EU levels (Romão, Citation2020; Sörvik et al., Citation2019), whereby sectoral (meta)governance has significantly evolved over time, making the travel industry a highly suitable case for a longitudinal TPSNE analysis.

Owing to the study’s longitudinal focus, covering the period from the late nineteenth century up to the present as well as its suprascale orientation, empirical data sources consist mainly of various documents supplemented by interviews with institutional tourism stakeholders. Secondary historical material, such as academic literature, mostly informs the analysis of the time up to the mid-twentieth century, due to the absence of formal tourism planning during this era. For the period from the late 1960s to the present, empirical data derives from policy and planning documents alongside expert reports. Strategy and planning documents from EU, national and regional levels dealing directly with tourism, but also with the wider socio-economic and political development of the case regions, serve to uncover the changing modes of tourism metagovernance embedded in the wider political economy setting. Overall, the sampling was concentrated on broad tourism-related documents in order to provide insights into the components of the TPSNE framework and the various actors involved in tourism development, most notably the state as well as public and private organisations and companies. In addition, insights into more recent development trajectories and the roles of non-governmental actors in tourism governance were gained through the analysis of online texts as well as interviews with a total of 16 local and regional tourism stakeholders. The interviewees were selected due to their professional roles in different fields and levels of tourism, including destination management, tourism education, regional development and public funding, private sector consulting and industry lobby organisations (see Appendix 1A in the online supplemental data; for anonymity reasons, the interviewees are referred to as I1 to I16 and their organisations as well as their specific professional roles are generalised as much as possible). The interviews, held online in English between Spring 2022 and Autumn 2023 (except for one in-person interview), lasted 30 to 90 minutes and were transcribed verbatim. The interview questions focused predominantly on institutional practices, governance issues and more recent tourism development trajectories in Lapland and Norrbotten. Some interviewees had only been in their current position for a few years while others had been professionally engaged in tourism since the early 1990s, enabling them to reflect more thoroughly on the transformation of tourism in recent decades. All interviewees were first contacted in an email, in which the study’s purpose and thematic scope, as well as the voluntary nature of the interview, were explained. In their written replies, the 16 participants consented to be interviewed and were informed again at the beginning of the interviews that their identities would be anonymised in all research output and that it would be possible to withdraw from both the interview and the entire study at any point.

All empirical material was coded in the same manner. The first coding round focused on the specific TPSNE configurations (including structuring principles and fields) of tourism development metagovernance in Lapland and Norrbotten and the dominant actors involved in tourism. Secondly, the social and spatial outcomes in the regions of these tourism metagovernance actions were coded. Given the suprascale perspective in this paper, the TPSNE changes were categorised into different periods corresponding to larger shifts in geo- and sociopolitical organisation. These transformations are commonly framed as global regime shifts from pre-Fordism, over welfare state Fordism or spatial Keynesianism, to the networked and neoliberal competition state (Bohlin et al., Citation2014; Kantola & Kananen, Citation2013; Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013). This suprascale angle, coupled with the chosen data, presents limitations regarding what detail the analysis can cover. While the following sections offer broad categorisations in relation to the TPSNE framework, future examinations could be broken down into more detailed classifications, such as locally specific manifestations of tourism metagovernance.

4. MULTISPATIAL METAGOVERNANCE IN TOURISM THROUGH THE LENS OF THE TPSNE FRAMEWORK

4.1. Approximately 1870–1945: integrating the Northern periphery into national territory

This period covers the beginning of organised tourism until the end of the Second World War, which can be seen as one of the major shifts in globalisation as trade and tourism extended under new production situations. In Sweden and Finland, tourism and its governance share the same origin, namely the quest of a national government for control over territory and a unitary population bound to its fatherland. Both Finland and Sweden lacked a coherent society that shared a common understanding of a national territory and cultural heritage (Sörlin, Citation2002). Hence, the political elites of the metropolitan South fostered a ‘nationalism from above’, aiming to root the population into the state space through the invention of a national history, folk tradition and national landscapes (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013). In addition to literature, print media and school education, tourism was also a powerful outlet for the dissemination of state-spatial imaginaries (Lähteenmäki, Citation2006; Löfgren, Citation2001).

The northernmost regions were geoeconomically as well as ideologically essential for both countries. Northernmost Sweden was seen to constitute a ‘land of the future’ even in ideological terms, as beliefs of the northward migration of culture, referring to a stages model of socio-cultural evolution from the South (the origin of man) to the North (the highest stage of civilisation), were widespread among Sweden’s political and academic elites (Kjellén, Citation1906; Sörlin, Citation1989). Finland had been under Swedish rule for more than 600 years before it became a dutchy of the Russian empire in 1809 and then independent in 1917, and the country’s northernmost areas were crucial as natural resource suppliers for its industrialisation. Petsamo, which was ceded to Finland in 1920 but returned to Russia after the Second World War, was of geoeconomic and geopolitical significance due to its nickel deposits and its location offering shipping access to the Arctic Ocean (Lähteenmäki, Citation2006). In the course of its Finnicisation policy, the state encouraged migration to and tourism in Petsamo (Hautajärvi, Citation2014).

Tourism metagovernance was thus pursued largely in a territorialising manner, with territory and environment as its major objects. The governments of Sweden and Finland did not steer tourism directly but rather used funding to support associations governing the development of domestic travel and the creation of tourist facilities (Anttila, Citation2014). Among these actors, the Swedish (Svenska Turistföreningen, STF, founded in 1885) and Finnish (Suomen Matkailijayhdistys, SMY, founded in 1887) tourist associations constituted the main network players; but state-owned companies, such as the railroad providers or the Finnish alcohol monopoly Alko, were also actively involved in tourism development. These organisations established and operated tourist accommodation and hiking trails, offered trips and published travelogues. The tourist associations’ headquarters were located in the southern capitals and were led by elite functionaries who were ideological supporters of state nationalism (Hautajärvi, Citation2014). The guiding motto of the SMY and the STF, ‘know your country’ (Löfgren, Citation2001), and their mission ‘to awaken the interest of citizens and foreigners to travel in this country and to make it easy, thereby expanding the knowledge of its nature and people’ (Syrjänen, Citation2009, p. 89), illustrate the organisations’ territorial aspirations, supporting the nation-building agendas of both Finland and Sweden.

During this phase, the first major tourism development activities of the SMY and the STF took place in Norrbotten and Lapland. In the Swedish North, tourism development was largely governed by scientific nationalism coupled with landscape romanticism. Geology scholars and mountaineering enthusiasts with a background in Arctic research created the STF and opened the first tourist hiking cabins in 1888 between Kvikkjokk and Sulitelma, followed by tourist stations in Abisko (built in 1906) and Kebnekaise (built in 1907), which also served as research stations. These tourism activities, led by highly recognised scholars, helped to link Norrbotten to the population’s image of Sweden’s territory. Even though tourism at the time was mainly accessible to the metropolitan bourgeoisie, bureaucrats and people in paid employment, the mounting tourism and science reports of the North in print media and films conveyed the desired spatial state and place imaginaries across the whole country (Löfgren, Citation2001; Sörlin, Citation2002).

The northernmost ‘wild’ or uncultivated nature was a defining national feature. An example of the connection between nature and national patriotism is the remark made by Swedish natural historian Gustav Kolthoff, as cited in Haraldsson (Citation1987, p. 71): ‘few countries are richer or more glorious in nature than our own. The knowledge and love of this nature must greatly assist in increasing the love of our native land – one of the noblest feelings’. The newly found appreciation for northern nature and its touristic value materialised in the creation of Abisko National Park in Norrbotten in 1909. Finland followed, establishing its first national parks Pallas-Ounastunturi and Pyhätunturi in Lapland in 1938. From a governance point of view, creating national parks can be seen as a strategy for territorialising environment and placing it under national rule beyond agricultural cultivation, urbanisation, or resource extraction. By 1935, the STF ran 187 hostels across Sweden which were affordable to the broader population, and the organisation emphasised the beauty of nature in every place in Sweden and its health benefits for everyone (Löfgren, Citation2001).

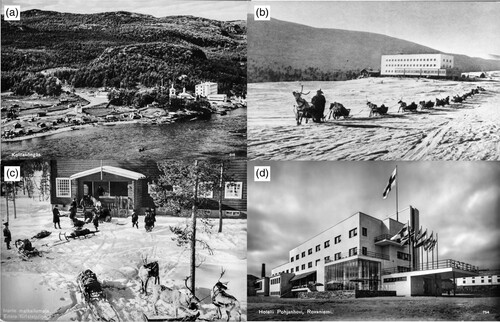

Compared to Sweden, control over territory was more pronounced in the tourism development in Lapland and its role in the Finnish state’s post-independence geography-making projects. Already here we can see a stronger role of tourism in Finland than in Sweden, with Sweden from the outset focusing more on industrial development as an expression of national power (Sörlin, Citation1989). Tourism in Lapland proliferated from the 1930s onwards, with the SMY tasked and financed by the state to build and run touristic infrastructure in Petsamo but also in other parts of the country in order to strengthen the Finnish presence (Hautajärvi, Citation2014). Partanen (Citation2009, p. 17) notes that ‘at that time, the entire Finnish society was supporting the Tourist Association [SMY], because tourism was perceived as an important part of Finnish identity construction’. The identity-building aspects embedded in tourism development can be seen in, among other things, the aspirational architecture of hotels and hostels in Lapland. During the first half of the twentieth century, a small network of Helsinki-based SMY functionaries and elite architects centrally planned and designed tourist facilities that were to be characteristic of the county (). Simple wooden lodges sought to convey neo-national romanticism and invoke a sense of shared Finnish folk traditions (Hautajärvi, Citation2014), while the functionalist hotels – among them Kolttaköngäs in Petsamo (built in 1938), Pohjanhovi in Rovaniemi (built in 1936) and Pallastunturi (built in 1938) (Partanen, Citation2009) – can be interpreted as an attempt by Finland to demonstrate soft power across its territory and to display the state’s modernity to the local population as well as the world (Fregonese & Ramadan, Citation2015). Yet, the imposed spatial vision of tourism development largely excluded the lived realities of locals in Lapland, or reduced it to a pre-modern relic to be gazed upon. The SMY hostels and hotels also did not provide much direct employment for the local population, as staff and head hostesses were predominantly Swedish-speaking non-locals (Hautajärvi, Citation2014). Nonetheless, some Sámi reindeer herders offered reindeer sled rides or sold souvenirs.

Figure 2. (a) The functionalist hotel in Borisoglebsky (Kolttaköngäs in Finnish)/Petsamo (right) stood in stark contrast to the Orthodox church and the Skolt Sámi village. (b) Reindeer sleds were the most common transport mode for travelling the last few kilometres to the Pallastunturi hotel in the winter. (c) The tourist station in Inari is an example of the twentieth-century neo-national romanticist building style of Lapland’s tourist accommodation. (d) In the late 1930s, the Pohjanhovi hotel in Rovaniemi was one of the most modern buildings in Finland.

Source: Lapin Maakuntamuseo (Citationn.d.). Published with permission.

The period exemplifies a territorial logic that influenced all fields of multispatial metagovernance, and the role of place per se, for instance, was secondary to that of the nation. In relation to spatial effects and actions, tourism was metagoverned by state-endorsed actors according to nationalist ideals. summarises the territorial logic of tourism metagovernance that drove tourism development between 1870 and 1945 in Lapland and Norrbotten.

Table 2. Multispatial metagovernance of tourism in Lapland and Norrbotten from 1870 to 1945.

4.2. Approximately 1945–1990: Nordic welfare state transformations and the introduction of mass tourism

This period covers the end of the Second World War until the resolution of the Cold War, which had major impacts, particularly in Finland. The post-war years are generally marked by the introduction of a broader consumption society and the rise of new networks beyond the state. Sweden and Finland expanded their welfare state systems into almost all spheres of public and private life. Both economies thrived during the industrial post-war boom, often labelled the Fordist period, and socio-economic Keynesianism dominated until the late 1970s (Kantola & Kananen, Citation2013). While the Finnish state endeavoured to prevent political revolt and to craft a unitary society characterised by a strong national identity and willingness to defend the country in the face of the Cold War (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013), the Swedish state aspired to nurture a healthy, democratic society which could be displayed as a cultural ideal to the world (SOU, Citation1965; Sörlin, Citation1989). A common social self-perception that both national governments fostered among their populations was that of a nature-loving but modern and technology-oriented nation (Löfgren, Citation2001). Regarding the spatial strategy of the Nordic welfare state, governance relied largely on territorialisation-place combinations aiming to integrate places and their populations into national territory (Jessop et al., Citation2018; Jones, Citation2018) by reducing uneven development and class disparities while enabling access to mass consumerism (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013). Domestic tourism and recreation constituted a vital component in Sweden’s and Finland’s nation-building projects, and the Nordic ‘democratic model of tourism’ opened leisure travel to the masses (Anttila, Citation2014, p. 325). In addition to installing regular school holidays, several holiday acts were passed in the 1960s and 70s, shortening the work week to 40 h and granting full-time employees a minimum of four weeks’ paid leave annually. The domestic travel mobility of both Finns and Swedes also increased tremendously thanks to private car ownership (Hautajärvi, Citation2014).

With respect to TPSNE configurations, place-making within a territorial reference frame and the society as its object was majorly advanced in Norrbotten’s and Lapland’s tourism through state-governed regional planning, which developed from the late 1940s onwards and expanded rapidly during the post-war period. In the late 1960s, both nation-states enlarged their formal steering capacity in tourism marketing abroad as well as domestically in consultation with the private tourism sector (Häyhä, Citation2011). Yet, governance responsibilities for tourism – revolving mostly around financial support for or ownership of tourism infrastructure and physical planning – came to be dispersed among many newly formed agencies, ministries and state-owned companies (Bohlin et al., Citation2014). In Sweden, this materialised in the designation of 25 specific areas for tourism development across the country (the Abisko-Kebnekaise mountains, the Bothnian Bay archipelago, and parts of the Vindel River basin in Norrbotten) (SOU, Citation1975). In Lapland, tourism development followed a centre-based development strategy that resulted in the creation of numerous tourist resorts (Toiviainen, Citation1974). Tourism and domestic recreation also became more accessible to the whole population in the 1960s and 1970s through camping (Anttila, Citation2014). The number of campgrounds expanded in both countries, with Lapland counting 84 campsites in 1981, which were predominantly located along the main roads and catered to road trippers (Lapin seutukaavaliitto, Citation1981). Moreover, second-home dwelling became another popular aspect of Nordic society and accelerated during the 1980s; in many cases as a result of people taking up work in the city while retaining the family home as a second home, but also through the development of new facilities to support health and sporting in people’s newly available leisure time (Toiviainen, Citation1974).

Welfare state place-making sought to govern environment in a way so as not only to turn nature into productive spheres but also to set nature areas aside for recreation. Through coordinated state planning, national parks and other areas that were not used for resource extraction and industry became sport pleasure peripheries. The ideal Swede and Finn were to spend their free time in an active manner, close to nature (Anttila, Citation2014). The instrumentality of domestic tourism, which was intimately connected to ‘friluftsliv’ (outdoor life), in nation-building is strongly pronounced in the Swedish case: ‘a healthy outdoor life seeks to create a counterweight to the stress of society’s mechanized, abnormal life’ (SOU, Citation1965, p. 92). The states’ respective social tourism and moral agenda were supported by a multitude of other actors. Employers, labour unions and social organisations built tourism facilities where citizens could spend inexpensive holidays in a societally beneficial way, as a rested worker was seen to productively contribute to an aspiring industrial nation (Anttila, Citation2014).

Despite the national governments’ attempts at spatial homogenisation, however, the exoticness of Lapland and Norrbotten from a metropolitan perspective was amplified in tourism place-making by appropriating Sámi culture as a marketing prop and entertainment product, often resulting in stereotypical othering (Beskow, Citation1960; Hautajärvi, Citation2014). Nevertheless, many Sámi families earned an income through tourism by selling handicrafts and offering snowmobile or reindeer safaris while being fully integrated into modern life (Viranto, Citation1977).

Social value-focused tourism metagovernance transformed with the oil crisis of the 1970s and the general slowdown in the post-war growth. An accelerating decline of primary production and extraction industries turned Lapland and Norrbotten into economic problems for their national governments (Nilsson & Lundgren, Citation2015), and different tourism development trajectories unfolded in the two counties. Between 1980 and 1990, municipalities in Lapland received massive state investments for the construction of numerous winter sport resorts, accelerating not only the employment and income contribution of tourism to the regional economy that developed during the 1970s but also the privatisation of the sector (Viranto, Citation1977). This period of boosterism, dubbed the ‘crazy years’ of tourism in Lapland (Tyrväinen et al., Citation2011, p. 7), can be seen as a metagovernance strategy for economic place-making within networks to counteract socio-economic decline. Interviewee I9 noted that these state investments in touristic infrastructure laid the foundation for subsequent entrepreneurial buy-ins, without which the development of tourism as a major economic branch in Lapland would not have happened.

International tourism development received a major boost in 1985 through the creation of the Santa Claus Village attraction in Rovaniemi and a simultaneous marketing campaign by the Finnish Tourist Board that branded Lapland ‘the official home of Santa Claus’ (Pretes, Citation1995), triggering the growth of Christmas-themed charter trips. However, these massive investments in tourism infrastructure across Lapland also had negative consequences. In the absence of regional governance and planning coordination, municipalities built tourist resorts with thousands of beds, which were frequently unprofitable and caused significant ecological damage as the municipal physical planning had not considered landscape values, building aesthetics, or environmental impacts (Hautajärvi, Citation2014). In Ylläs, Levi and Pyhä, the Finnish state opened previously protected areas for ski slopes and large accommodation infrastructures, which transformed the fell ecosystems dramatically. Growing tourism also led to conflicts between locals and domestic as well as international recreationists, especially regarding the freedom to roam (allemansrätten/jokaisenoikeudet). Residents complained about tourists who littered, fished in local waters and picked berries, and many municipal representatives advocated for charging especially foreign travellers for their use of nature (Viranto, Citation1977). Although such charges periodically re-emerge in public discussion they have never been implemented, and to this day the public right to roam remains a fundamental principle governing access to nature in Nordic societies (Øian et al., Citation2018).

In Norrbotten, economically motivated policy initiatives for tourism development remained smaller given the dominance of resource/manufacturing industries, and tourism could not compete with high-paying industrial jobs or secure public-sector ones (SOU, Citation1990). Ski lifts were built in Norrbotten as well, but were mainly intended for local use, and individual attempts by municipalities to spur tourism development were generally less successful than in Lapland. For instance, Övertorneå municipality had sought to develop the Christmas attraction Luppioberget since the 1960s, but it never gained market traction (Palomäki, Citation2019). A major push for international tourism development in Kiruna was initiated in 1989 by a private entrepreneur who founded Icehotel in Jukkasjärvi without (initial) state support (Icehotel, Citation2020). This business set a new pathway for Nordic tourism, merging accommodation with iconic attraction and turning the negative connotation of coldness into an experience for well-off international travellers. Owing to the Icehotel’s enormous success, similar venues were replicated in northernmost Finland and Sweden as well as in Norway, Iceland and Greenland, and became signature attractions for international tourism in the regions particularly from the 2000s onwards, encouraged as viable economic options for northern sparsely populated areas by state strategy plans (e.g., Finnish Government, Citation2021).

Characteristic of the period until the 1990s was not only a strong role of the state in governing tourism in tandem with the municipalities (e.g., SOU, Citation1965) but also the visions of socio-spatial homogenisation and welfare provision contained in planning and tourism development, fostering the introduction of mass tourism based largely on environmental features. This era can be seen as a transition from more territorially based metagovernance to a focus on place-making steered by the state. The role of networks as a major structuring principle was still delimited by the state, but actions by individuals that were initially not state-supported (such as the development of Icehotel) foreshadow the larger-scale networks beyond the state that gained prominence in the period that followed. illustrates the dominant territorial and place-making structuring principles of metagovernance. In relation to spatial effects and actions, the period illustrates how state planning fostered the governance of people through state space (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013).

Table 3. Multispatial metagovernance of tourism development in Lapland and Norrbotten from 1945 to 1990.

4.3. Approximately 1990–present: competitiveness, networking and spatial rescaling within the EU and an international Arctic

This period ranges from about the end of the Cold War – highlighting the growth in metagovernance constellations which continue to mark the development of tourism – into the present. These governance reorderings to political and socio-economic stability have been ideologically accompanied by hegemonic beliefs that competitiveness, an entrepreneurial yet resilient society, and economic growth are the preconditions for social justice, sustainability and prosperity (Kantola & Kananen, Citation2013). A major factor during this period was the severe banking crisis and economic recession at the beginning of the 1990s, which hit Finland harder than Sweden. While the depreciation of the Finnish currency led to the recovery of export industries throughout the country, it also enhanced inbound visitation and tourism as an export industry in Lapland at the same time as domestic tourism declined due to unemployment and wage depression (Saarinen, Citation2001). By the end of 1992 many tourism enterprises in Lapland were nevertheless bankrupt, requiring state bailouts and formerly state-owned businesses were privatised (Hautajärvi, Citation2014). However, I10 emphasised that the focus on export markets offering highly commodified nature-based winter tourism continues to this day as this is the most profitable branch of tourism, in which Lapland is well positioned in an international comparison. In Norrbotten, registered overnight stays remain largely domestic and peak during the summer months, although international winter tourism has seen significant growth as well.

Another central push for tourism development emerged alongside the 1995 accession to the EU of Finland and Sweden. The EU Territorial Governance and Cohesion Policy, channelling economic and social development efforts within different regions, enhanced decentralisation through the creation of Regional Councils, which were also tasked with regional development governance (Arter, Citation2001). This new regionalism, underpinned by neoliberalism and competitiveness thinking in a globalised world (Kantola & Kananen, Citation2013), entailed a shift from redistributive compensation for economically lagging areas in northernmost Finland and Sweden to supply-side policies and structural funding promoting entrepreneurship and place-based initiatives for economic growth (Lidström, Citation2020). Today these policy directions are implemented as part of smart specialisation programmes that seek collaboration between RDI (research, development and innovation institutions), public-private alliances, businesses and civil society (Poikela et al., Citation2023).

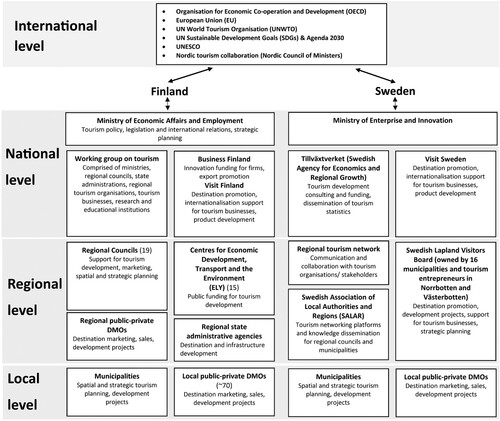

Within these transformations in regional development, tourism (meta)governance in Norrbotten and Lapland also became increasingly pluralistic (e.g., Europaforum Norra Sverige, Citation2017; Lapin Liitto, Citation2021). A rescaling of territory led to a more defined multilevel governance (MLG) structure ranging from supranational down to local scales, as depicted in . For instance, Sweden’s current national tourism strategy presents MLG as a way to establish policy coherence and efficiency through consensus-building across different levels to support ‘sustainable and competitive tourism’ (Regeringskansliet, Citation2021, p. 11). Concrete examples of this include, in Finland, the creation of a nationally steered sustainability certification for tourism businesses or the integration of higher-scale strategic tourism plans into those of lower-scale organisations (TEM, Citation2022). Yet tourism development on the ground in both Norrbotten and Lapland is also driven by the complex, tangled and uneven relations situated in territories, places, scales and networks that are not usually covered in MLG conceptualisations (Jessop, Citation2016).

Figure 3. Multilevel governance in Lapland and Norrbotten.

Source: Authors.

In this context, the growing role of tourism entrepreneurship as a means for place-based regional development rooted in the commodification of local culture and nature advanced by EU, national and regional policies has significantly shaped the sector from the mid-1990s onwards (OECD, Citation2017; Poikela et al., Citation2023; Region Norrbotten, Citation2020). Due to the mounting demand for tourism worldwide, the encouragement of entrepreneurship and the rising popularity of lifestyle mobility, the number of tourism firms – ranging from micro-sized firms to regional chain hotels – increased in Norrbotten and Lapland, also because compared to other industries, the entry barriers to tourism are lower (e.g., Carson et al., Citation2018). To channel and support private-sector tourism development in destinations as part of national devolution and the EU’s new regionalism, project-based development initiatives as well as local and regional destination marketing and management organisations (DMOs) emerged in Norrbotten and Lapland. Interviewees underscored the advantage that knowledge exchange in differently scaled networks (including ‘scale jumping’ of local and regional levels to EU and international levels) may trigger business innovations and cooperation, contributing positively to the economic growth of tourism. On the other hand, the ‘projectization of regional development’ (I2) also entails challenges, such as difficulty ‘creat[ing] a consistent long-term plan for destination development’ (I3, I4). In addition, I2 highlights that EU Cohesion Policy and project-based regional development represent a

system [that is] in itself (…) quite fragmented; it is quite complex and it is quite administrative[ly] heavy for small actors and organisations to work with (…). It requires a lot of local and regional leadership when [one is] an intermediary[,] combining these complex institutional systems, financial systems[,] with the needs on the ground in these sorts of SMEs and different business initiatives.

In addition to rescaling, networking has become a more prominent structuring principle of metagovernance since the 1990s. The dominance of networking in the nation-state territory frame in Lapland and Norrbotten is encouraged by regional cross-border collaboration and direct networking with EU bodies. Within the EU’s INTERREG programmes, tourism has gained salience as a tool for functional region-building, involving the creation of joint infrastructures, tourist attractions and destination governance networks, and imaginarily denoting socio-spatial relations across and identification with a region (Prokkola, Citation2011). Today, Lapland and Norrbotten belong to many different cross-border conglomerates, such as the Barents and the North Calotte regions, but the Arctic has become the most prominent soft space (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009) or reference frame for tourism development in recent times. This took place following the entry of all Nordic countries – and resultantly also Finland and Sweden as non-littoral states which had not been party to earlier Arctic Basin developments – into the Arctic Council, formed in 1996 following the end of the Cold War (Keskitalo, Citation2004).

The cross-border project Visit Arctic Europe (2015–2022) was a major step towards the establishment of a functional as well as imaginary Arctic destination, marketing the region as a unified area and enhancing cross-border cooperation between tourism firms and organisations. I5 remarked that

the market has been hungry for this [an Arctic travel destination] already, [and] (…) tour operators were saying that they already see us as one destination, but until then we [the tourism sectors in northern Finland, Sweden and Norway] had been working separately and more or less seeing each other as competitors, but then kind of switching [our] mind[set] to (…) [the notion that] we can be stronger together.

However, networked governance across scales also offers new ‘political opportunity structures’ (Zachrisson & Beland Lindahl, Citation2023, p. 2) for, for instance, Sámi organisations (e.g., Saami Council, Citation2019). In the context of tourism, in 2018 the Sámi Parliament in Finland adopted a set of ethical guidelines for Sámi tourism to counter the exploitation of Sámi for and by ‘outsiders’, who often resorted to an ‘incorrect, primitivised image of the Sámi’ and ‘false information’, which has ‘detrimental effect[s] on the vitality of both the Sámi community and Sámi culture’ (Sámi Parliament Finland, Citation2018, p. 3). These guidelines seek to instruct non-Sámi travel operators and tourists to act responsibly and ‘respect local communities and their living cultural landscape’ (Sámediggi, Citationn.d.). Although the initiative is nonbinding and voluntary, network collaboration and communication provide new means for agency for Sámi organisations to work towards ‘the future we want’, in which

modern livelihoods such as responsible and ethically sustainable tourism based on Sámi culture support the profitability of traditional livelihoods and promote employment locally. (…) Everyday lives and festivities of the Sámi community as well as land use in Sámi Homeland have been successfully co-ordinated with tourism while the rights of the Sámi and Sámi culture have been taken into consideration and respected. (Sámediggi, Citationn.d.)

The role of non-regulatory approaches is also salient when it comes to environmental governance and the sustainable utilisation of ‘sensitive’ Arctic nature. Ecolabels and certification schemes that tourism businesses and destinations can adopt voluntarily rather than through strict regulation have become industry standard. I9 noted that although these measures helped to transform sustainability in Lapland’s tourism from just ‘talking’ and ‘greenwashing’ into practical actions, voluntary labels as a metagovernance tool are insufficient for dealing with systemic market failures. These ‘failures’ refer to seasonal overtourism as well as the difficulty to include all stakeholders in a common framework in order to manage ‘balanced growth’ (I10) within a capitalist system rooted in the continuous economic expansion of individual businesses.

The metagovernance framework for tourism development since the early 1990s has thus been revolving around networking and (re)scaling as its structuring principles, with export-oriented economic growth becoming an increasingly important aim (). In terms of spatial effects and actions, the respective metagovernance initiatives have led to a growing complexity of networks at various scales (with sometimes conflicting interests) (Jones, Citation2018). The mobilisation of the Arctic as a spatial reference for tourism development can be interpreted as a simultaneous counterweight to this complexity, providing a common identity in a global tourism market. summarises the multispatial metagovernance configurations from the early 1990s to the present.

Table 4. Multispatial metagovernance of tourism development in Lapland and Norrbotten from 1990 to present.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The paper adapted Jessop et al.’s (Citation2008) TPSNE framework to a longitudinal qualitative study on the transformations of metagoverning tourism development. The TPSNE matrix helped to showcase the evolution of state metagovernance during pre-Fordism, welfare state Fordism and neoliberal competition state epochs (Bohlin et al., Citation2014). These orderings set the overall conditions for tourism development on regional levels, including what actions, cooperation modes, tourism firms and conceptions of the environment are possible for certain actors during a particular time. The analysis also unveiled how space and society relate to each other (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013) within the different metagovernance reorderings or spatio-temporal fixes aiming for political legitimacy and socio-economic stability (Jessop, Citation2019).

The study has shown that from the late nineteenth century to the end of the Second World War, tourism in Lapland and Norrbotten functioned as a means for soft state power seeking to advance a loyal and patriotic population. The state governed the tourism development indirectly through state-owned companies and elite networks, whereby domestic vacationing offered itself as a means for displaying the greatness of state territory, either by facilitating for citizens to travel their countries or by widely disseminating tourism nature images to the population (Löfgren, Citation2001). In the post-war period until the early 1990s, domestic tourism development was metagoverned by the Swedish and Finnish welfare states as part of their agendas to equalise places inside the national territory and to facilitate a nature-loving, healthy, loyal consumer society. This spatio-temporal fix of securing state legitimacy through (touristic) mass consumption and central welfare planning was gradually abandoned due to economic crisis, and the socio-economic disparities between different regions in Finland and Sweden became increasingly prominent (Arter, Citation2001; Nilsson & Lundgren, Citation2015). The problem was fixed by rescaling upwards to the EU, downwards to the newly established regional level, and sidewards to the private sector and civil society, in addition to enacting policy support for place-based development through entrepreneurship (Kantola & Kananen, Citation2013). In this context, tourism functioned as a means for regional development, with governance and policy support therefore increasingly focusing on export-oriented travel and hospitality instead of domestic leisure. The metagovernance landscape proliferated as well, with tourism development in Lapland and Norrbotten coordinated by differently scaled networks, including regional- and local-level public-private DMOs and municipalities alongside different national and regional bodies and the EU structural funds programmes. On the one hand this institutional and policy fragmentation, characteristic of the sector’s governance, provides an opportunity for mobilising a wide variety of stakeholders, while on the other, the growing complexity may amplify the ineffectiveness of the governance due to actors’ conflicting priorities (Jones, Citation2018).

The interviewees illustrated this issue, particularly concerning the example of project-based tourism development governance, which offers innovation potential but often inhibits long-term strategic planning and the sustenance of durable networks. A related, and noteworthy, aspect concerns the spatial identification of Norrbotten and Lapland with the Arctic as a strategic means to integrate and upscale both counties in global markets and to facilitate economic competitiveness beyond state territory (Moisio & Paasi, Citation2013). Such networked metagovernance may provide opportunities for bottom-up initiatives (Zachrisson & Beland Lindahl, Citation2023); however, these prospects for agency are not equally open to all actors and depend on wider structural and historical circumstances (Jessop, Citation2016).

The contributions of this paper are threefold. Firstly, it offers an empirical application of the TPSNE matrix to exemplify how socio-spatial relations as sites, objects and means of metagovernance, as well as the changing role of the state, materialise locally (Jessop, Citation2016). Secondly, the case of tourism development exposes particularly the social value underpinnings implicit in spatio-temporal fixes and strategic selectivity of metagovernance, and illustrates the way development in any sector will necessarily be related to larger metagovernance developments. Highlighting the spatial effects and actions of these metagovernance strategies, the paper also shows that the overarching metagovernance transformations manifested themselves somewhat differently within the actual tourism pathways of Lapland and Norrbotten ‘on the ground’. Therefore, further research employing the TPSNE could illustrate, in greater detail, how macro-level structural conditions and agency interact with micro-level path dependencies and local agency in order to construct space to attend to certain policy problems.

Thirdly, adding environment (E) to the TPSN framework facilitates an understanding of spatial production in which nature constitutes an integral part of human life and regional development (meta)governance, and results in specific place-making that also influences and reproduces specific conceptions of nature. Thus, systematic frameworks such as the TPSNE matrix respond to current calls for more complexity analyses of (meta)governance, which are considered vital given the acceleration of the socio-environmental polycrisis (e.g., Farsari, Citation2023). Such analyses may offer a stronger understanding both of how we construct the environment and legitimate actions within it, and of how certain development paths are made possible in different times and socio-spatial contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (116 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2009). Soft spaces, fuzzy boundaries, and metagovernance: The new spatial planning in the Thames Gateway. Environment and Planning A, 41(3), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40208

- Amore, A., & Hall, C. M. (2016). From governance to meta-governance in tourism? Re-incorporating politics, interests and values in the analysis of tourism governance. Tourism Recreation Research, 41(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2016.1151162

- Anttila, A. H. (2014). Leisure as a matter of politics: The construction of the Finnish democratic model of tourism from the 1940s to the 1970s. Journal of Tourism History, 5(3), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755182X.2013.868532

- Arter, D. (2001). Regionalization in the European peripheries: The cases of Northern Norway and Finnish Lapland. Regional and Federal Studies, 11(2), 94–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/714004693

- Bennett, M. M., & Iaquinto, B. L. (2023). The geopolitics of China’s Arctic tourism resources. Territory, Politics, Governance, 11(7), 1281–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1887755

- Beskow, H. (1960). Introduction. In F. Thunborg, & B. Andersson (Eds.), Norrbotten—land of the Arctic circle. A book about the far north of Sweden (pp. 5–14). P. A. Nordstedt & Söners Förlag.

- Bohlin, M., Brandt, D., & Elbe, J. (2014). The development of Swedish tourism public policy 1930-2010. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 18(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.58235/sjpa.v18i1.15697

- Bohn, D., Carson, D. A., Demiroglu, O. C., & Lundmark, L. (2023). Public funding and destination evolution in sparsely populated Arctic regions. Tourism Geographies, 25(8), 1833–1855. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2023.2193947.

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2011). Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.580586

- Brenner, N. (2009). Open questions on state rescaling. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 2(1), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp002

- Büscher, B., & Fletcher, R. (2015). Accumulation by conservation. New Political Economy, 20(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2014.923824

- Carson, D. A., Carson, D. B., & Argent, N. (2022). Cities, hinterlands and disconnected urban-rural development: Perspectives from sparsely populated areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 93, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.05.012

- Carson, D. A., Carson, D. B., & Eimermann, M. (2018). International winter tourism entrepreneurs in northern Sweden: understanding migration, lifestyle, and business motivations. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2017.1339503

- Duarte, F. (2017). Space, Place and Territory. A Critical Review on Spatialities. Routledge.

- Elden, S. (2010). Land, terrain, territory. Progress in Human Geography, 34(6), 799–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510362603

- Europaforum Norra Sverige. (2017). Added value of the EU Cohesion Policy in Northern Sweden.

- Farsari, I. (2023). Exploring the nexus between sustainable tourism governance, resilience and complexity research. Tourism Recreation Research, 48(3), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1922828.

- Finnish Government. (2021). Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/163247/VN_2021_55.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Fregonese, S., & Ramadan, A. (2015). Hotel geopolitics: a research agenda. Geopolitics, 20(4), 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2015.1062755

- Gailing, L., Bues, A., Kern, K., & Röhring, A. (2020). Socio-spatial dimensions in energy transitions: Applying the TPSN framework to case studies in Germany. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(6), 1112–1130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19845142

- Gajewski, R. (2022). The strategic-relational formation of regional and metropolitan scales: studying two Polish regions undergoing transformation. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9(1), 280–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2022.2071165

- Gammon, A. R. (2017). Not lawn, nor pasture, nor mead: Rewilding and the Cultural Landscape (Diss.), Radboud University.

- Gjaltema, J., Biesbroek, R., & Termeer, K. (2020). From government to governance … to meta-governance: a systematic literature review. Public Management Review, 22(12), 1760–1780. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1648697

- Haraldsson, D. (1987). Skydda vår Natur! Svenska Naturskyddsföreningens Framväxt och Tidiga Utveckling [Protect our Nature! The Rise and Early Development of the Swedish Nature Conservation Society]. Lund University Press.

- Hautajärvi, H. (2014). Autiotuvista Lomakaupunkeihin: Lapin Matkailun Arkkitehtuurihistoria [From Wilderness Huts to Holiday Towns: The Architectural History of Tourism in Lapland]. Aalto-yliopisto julkaisusarja (2014). Unigrafia.

- Häyhä, L. (2011). Viralliset valtakunnalliset matkailustrategiat [Official governmental tourism strategies]. In S. M. Y. Seniorit ja Suomen Matkailijayhdistys (Ed.), Lomasuuntana Suomi:Näin Teimme Suomesta Matkailumaan Suomen Matkailun [Travel Direction Finland: This is how we Transformed Destination Finland into Finnish Tourism] (pp. 17–23). Hipputeos Oy.

- Hillman, K., Nilsson, M., Rickne, A., & Magnusson, T. (2011). Fostering sustainable technologies: A framework for analysing the governance of innovation systems. Science and Public Policy, 38(5), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234211X12960315267499

- Hultman, J., & Hall, C. M. (2012). Tourism place-making: governance of locality in Sweden. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(2), 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.07.001

- Icehotel. (2020). Yngve Bergqvist – founder of Icehotel. https://www.icehotel.com/incredible-story-about-yngve-bergqvist-founder-icehotel.

- Jessop, B. (2016). Territory, politics, governance and multispatial metagovernance. Territory, Politics, Governance, 4(1), 8–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2015.1123173

- Jessop, B. (2019). Spatiotemporal fixes and multispatial metagovernance: the territory, place, scale, network scheme revisited. In M. Middell, & S. Marung (Eds.), Spatial formats under the global condition (pp. 48–77). De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

- Jessop, B., Brenner, N., & Jones, M. (2008). Theorizing sociospatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9107

- Jones, M. (2018). The march of governance and the actualities of failure: the case of economic development twenty years on. International Social Science Journal, 68(227–228), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12169

- Jordan, A., Wurzel, R. K. W., & Zito, A. R. (2013). Still the century of “new” environmental policy instruments? Exploring patterns of innovation and continuity. Environmental Politics, 22(1), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755839

- Kantola, A., & Kananen, J. (2013). Seize the moment: financial crisis and the making of the Finnish competition state. New Political Economy, 18(6), 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2012.753044

- Keskitalo, E. C. H. (2004). Negotiating the Arctic: The construction of an international region. Routledge.

- Keskitalo, E. C. H. (Ed.). (2019). The politics of Arctic resources. Change and continuity in the “old north” of Northern Europe. Routledge.

- Keskitalo, E. C. H. (2023). Rethinking Nature Relations. Beyond Boundaries. Edward Elgar.

- Kjellén, R. (1906). Nationell Samling. Politiska och Etiska Fragment [National Collection. Political and Ethical Fragments]. Hugo Gebers Förlag.

- Lähteenmäki, M. (2006). From reindeer nomadism to extreme experiences: Economic transitions in Finnish Lapland in the 19th and 20th centuries. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 3(6), 696–704. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2006.010913

- Lapin Liitto. (2021). Lapin Matkailustrategia. Päivitys Koronatilanteeseen 2021 [Lapland’s Tourism Strategy. Update in the COVID-19 Situation 2021]. https://www.lapinliitto.fi/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Lapinliitto-Matkailustrategia-2022-sivuina.pdf.

- Lapin maakuntamuseo. (n.d.). Image Collection. https://cumulus.rovaniemi.fi/arkistoaineisto/.

- Lapin seutukaavaliitto. (1981). Lapin Läänin Leirintäalueverkko [Lapland County’s Campsite Network].

- Lasswell, H. (1936). Politics; Who Gets What, When, How. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc.

- Lew, A. A. (2017). Tourism planning and place making: place-making or placemaking? Tourism Geographies, 19(3), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1282007

- Lidström, A. (2020). Subnational Sweden, the national state and the EU. Regional & Federal Studies, 30(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2018.1500907

- Löfgren, O. (2001). Know your country: a comparative perspective on tourism and nation building in Sweden. In S. Osmun Baranowski, & E. Furlough (Eds.), Being elsewhere: tourism, consumer culture, and identity in modern Europe and North America (pp. 137–154). University of Michigan Press.

- Moisio, S., & Paasi, A. (2013). From geopolitical to geoeconomic? The changing political rationalities of state space. Geopolitics, 18(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2012.723287

- Müller, D. K., Carson, D. A., de la Barre, S., Granås, B., Jóhannesson, G. T., Øyen, G., Rantala, O., Saarinen, J., Salmela, T., Tervo-Kankare, K., & Welling, J. (2020). Arctic tourism in times of change: dimensions of urban tourism. Nordic Council of Ministers. https://doi.org/10.6027/temanord2020-529

- Nilsson, B., & Lundgren, A. S. (2015). Logics of rurality: political rhetoric about the Swedish North. Journal of Rural Studies, 37, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.11.012

- OECD. (2017). OECD territorial reviews: Northern sparsely populated areas. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268234-en

- Øian, H., Fredman, P., Sandell, K., Sæþórsdóttir, A. D., Tyrväinen, L., & Jensen, F. S. (2018). Tourism, nature and sustainability: A review of policy instruments in the Nordic countries. TemaNord 2018: 534. https://doi.org/10.6027/TN2018-534

- Paasi, A. (2008). Is the world more complex than our theories of it? TPSN and the perpetual challenge of conceptualization. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26(3), 405–410. https://doi.org/10.1068/d9107c

- Pajvančić-Cizelj, A. (2022). Spatialities of feminist urban politics: networking for ‘fair shared cities’ in Central and Eastern Europe. Territory, Politics, Governance, 10(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1799849

- Palomäki, T. (2019). Anläggningen på Luppioberget får nya ägare: “Har kostat för mycket pengar”. SVT Nyheter. https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/norrbotten/luppioberget-kan-fa-nya-agare-foretaget-lovar-att-investera-40-miljoner-kronor-pa-anlaggningen.

- Parks, M. M. (2020). Critical ecocultural intersectionality. In T. Milstein, & J. Castro-Sotomayor (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Ecocultural Identity (pp. 103–114). Routledge.

- Partanen, S. J. (2009). Unelmia ja unelmien raunioita: Lapin matkailun perusta valettiin Petsamon tiellä [Dreams and ruins of dreams: the foundations of tourism in Lapland were laid on the Petsamo road]. In Suomen Matkailijayhdistys SMY ry & Suomen Matkailualan Seniorit ry (Eds.), Tunne maasi! Suomen Matkailun Kehitys ja Kehittäjiä [Know Your Country! Finnish Tourism Development and Developers], (pp. 16–20), Hipputeos Oy.

- Pierre, J., & Peters, G. (2020). Governance, Politics and the State (2nd ed.). Red Globe Press.

- Poikela, R., Heikkilä, P., & Mäcklin, K. (2023). A prosperous Lapland with Sustainable Innovations. Lapland’s Sustainable Smart Specialisation Strategy 2023–2027. https://arcticsmartness.fi/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/Taitto_strategia-ENG-WEB.pdf.

- Pretes, M. (1995). Postmodern tourism: the Santa Claus industry. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00026-O

- Prokkola, E. K. (2011). Regionalization, tourism development and partnership: the European Union’s North Calotte Sub-programme of INTERREG III A North. Tourism Geographies, 13(4), 507–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.570371

- Regeringskansliet. (2021). Strategi för Hållbar Turism och Växande Besöksnäring [Strategy for Sustainable Tourism and Growing Visitor Industry].

- Region Norrbotten. (2020). Smart Specialisation in Norrbotten. https://utvecklanorrbotten.se/media/jjfjx50k/smart_specialisering_eng_200707_webb.pdf.

- Romão, J. (2020). Tourism, smart specialisation, growth, and resilience. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102995

- Saami Council. (2019). The Sámi Arctic Strategy. Securing Enduring Influence of the Sámi People in the Arctic through Partnerships, Education and Advocacy. https://lcipp.unfccc.int/sites/default/files/2022-06/The%20Sami%20Arctic%20Strategy.pdf.

- Saarinen, J. (2001). The Transformation of a Tourist Destination. Theory and Case Studies on the Production of Local Geographies in Tourism in Finnish Lapland. Nordia Geographical Publication.

- Sámediggi. (n.d.). Ethical Guidelines for Sámi Tourism. https://samediggi.fi/en/areas-of-expertise/livelihoods-justice-and-environment/ethical-guidelines-for-sami-tourism/.

- Sámi Parliament Finland. (2018). Principles for Responsible and Ethically Sustainable Sámi Tourism. https://samediggi.fi/en/areas-of-expertise/livelihoods-justice-and-environment/responsible-sami-tourism/.

- Servillo, L. (2019). Tailored polities in the shadow of the state’s hierarchy. The CLLD implementation and a future research agenda. European Planning Studies, 27(4), 678–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1569595

- Soininvaara, I. (2023). The spatial hierarchies of a networked state: historical context and present-day imaginaries in Finland. Territory, Politics, Governance, 11(8), 1615–1634. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2021.1918574

- Sörlin, S. (1989). Land of the Future. Norrland and the North in Swedish and European Consciousness. Center for Arctic Cultural Research. Umeå University.

- Sörlin, S. (2002). Rituals and resources of natural history: the North and the Arctic in Swedish scientific nationalism. In M. Bravo, & S. Sörlin (Eds.), Narrating the Arctic: A cultural history of Nordic scientific practices (pp. 73–123). Watson Publishing International.

- Sörvik, J., Teräs, J., Dubois, A., & Pertoldi, M. (2019). Smart Specialisation in sparsely populated areas: challenges, opportunities and new openings. Regional Studies, 53(7), 1070–1080. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.153075

- SOU. (1965:19). Friluftslivet i Sverige [Outdoor life in Sweden]. https://lagen.nu/sou/1965:19.

- SOU. (1975:46). Regeringens Proposition om Planering och Samordning av Samhällets Insatser för Rekreation och Turism [The Government's Bill on Planning and Coordination of Society's Efforts for Recreation and Tourism]. https://lagen.nu/prop/1975:46?attachment=index.pdf&repo=propriksdagen&dir=downloaded.

- SOU. (1990:103). Turism i Norrbotten- att Utveckla Affärs- och Privatresandet i Länet [Tourism in Norrbotten- to Develop Business- and Individual Travel in the County]. https://lagen.nu/sou/1990:103.

- Swedish Lapland. (n.d.). This is Swedish Lapland – Your Arctic Destination. https://www.swedishlapland.com/.

- Syrjänen, O. (2009). Suomen matkailuliiton muutoksen vuodet [The Finnish Tourism Association’s years of change]. In (Suomen Matkailijayhdistys SMY ry & Suomen Matkailualan Seniorit ry Eds), Tunne Maasi! Suomen Matkailun Kehitys ja Kehittäjiä [Know your country! Finnish Tourism Development and Developers] (pp. 84–91), Hipputeos Oy.

- TEM. (2022). Yhdessä Enemmän – Kestävää Kasvua ja Uudistumista Suomen Matkailuun Suomen Matkailustrategia 2022–2028 ja Toimenpiteet 2022–2023 [More Together - Sustainable Growth and Renewal in Finnish Tourism, Finnish Tourism Strategy 2022-2028 and Measures 2022-2023]. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/164279/TEM_2022_51.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Toiviainen, E. (1974). Lapin Loma-Aluesuunnittelun Perusteet [Rationales of Lapland’s Tourism Area Planning]. Lapin seutukaavaliitto. Sarja A: 12.

- Torfing, J. (2016). Metagovernance. In C. Ansell, & J. Torfing (Eds.), Handbook on theories of governance (pp. 525–537). Edward Elgar.

- Tyrväinen, L., Silvennoinen, H., Hasu, E., & Järviluoma, J. U. (2011). Kaupunkilomalla vai Tunturiluonnossa? Kotimaisten Matkailijoiden Näkemyksiä ja Toiveita Lappilaisesta Matkailukeskusympäristöstä [On City Holidays or in Fell Nature? Domestic Travellers’ Perceptions and Expectations of Lapland’s Tourist Resort Environment]. Metla.