ABSTRACT

Africa’s renewed push towards infrastructure development brought with it new forms of territorialisation tied to both capital and labour. Infrastructures are expected to connect specific African hubs to global trade flows, promote industrialisation and increase employment rates, yet they often struggle to fulfil said promises. We explore the relationship between Africa’s ‘infrastructure turn’ and changing labour relations through the case of the Abidjan-Lagos Corridor in West Africa. Drawing from critical infrastructure studies and broader work in labour geography, we use the concept of suspension as a lens to illuminate a variety of processes – occurring across varied temporalities and scales – that are imbricated in the construction of different forms of infrastructural labour. We posit that infrastructure development as currently structured simultaneously (i) reinforces geopolitical inequities in the division of labour in the design and implementation of infrastructure projects; (ii) fosters competition amongst states for value and trade capture; and (iii) prompts contestation and disavowal in the context of the construction of specific projects. These three distinct, yet inter-related ways in which infrastructure development entangles with labour dynamics highlight that the work of imagining and crafting infrastructural promise creates pathways for novel, and often contested, configurations of labour relations.

1. INTRODUCTION

In March 2022, Dr Akinwumi Adesina, President of the African Development Bank (AfDB) Group, referred to the Abidjan-Lagos Corridor (ALCo) Highway as the key infrastructure development initiative to catalyse regional integration and connectivity in West Africa (AfDB, Citation2022). According to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), 75 percent of commercial activities in the region are concentrated along its coastal areas (ECOWAS Commission, Citation2017, p. 27), which are estimated to generate around 42 percent of West Africa’s total GDP (WB, Citation2022). The ALCo Highway is expected to connect key hubs to encourage cross-border trade, promote industrialisation and increase employment rates. The corridor’s ‘ultimate objective [is] to contribute to increased employment and income generating opportunities and to the reduce the levels of poverty of people whose livelihoods depend mainly on the modes of transport on the corridor’ (ECOWAS Commission, Citation2017, p. 30). In other words, the corridor aims to create formal labour via infrastructure development.

International organisations, government institutions, consultancies and funders commonly portray filling the so-called ‘infrastructure gap’ as the means to realise Africa’s development objectives, particularly that of creating jobs in countries with rapidly growing populations (e.g., Mali and Niger) or those with large amounts of un/underemployed individuals (e.g., South Africa). This has translated into a rapid increase in funds devoted to infrastructure development since the turn of the twenty-first century (Goodfellow, Citation2020; Nugent, Citation2018; Were, Citation2022). However, while infrastructures are expected to connect specific hubs on the continent to global trade flows, promote industrialisation and increase employment rates, they often struggle to fulfil these transformative promises. How does this uncertainty for what lies ahead impact those planning, realising or contesting infrastructures? And, crucially, what does this reveal about the relationship between infrastructures, those involved in their realisation, and those whose lived experiences are shaped by said projects?

Previous literature in critical infrastructure studies has highlighted that infrastructure projects are characterised by a range of actors and interests, publics and users, scales and temporalities, and are thus ‘dense social, material, aesthetic, and political formations that are critical to both differentiated experiences of everyday life and to expectations of the future’ (Anand et al., Citation2018, p. 3). Infrastructures have also been shown to encompass a plurality of connections and to embody a range of material, ideational, spatial and temporal processes (Anand, Citation2017; Guma, Citation2022; Larkin, Citation2013). This reveals that infrastructure development, and particularly its outcomes, can imply connectivity and potential, as well as disconnection and disavowal (Appel, Citation2012; Hagberg & Körling, Citation2016; Lesutis, Citation2019, Citation2022b).

This paper foregrounds a processual understanding of infrastructures and the systems that create them to explore the relations between infrastructure development and labour (understood as the socio-material practices and conditions underpinning infrastructural realisation). Infrastructure development is a process rather than a finished output (Anand et al., Citation2018), whereby relations evolve and are constantly (un)made or maintained. In recognising infrastructure development as ‘work-in-progress’, we aim to explicitly engage with the shifting relationship between infrastructure and labour. Specifically, our focus lies on both infrastructuring labour – a heuristic for the work of designing, discursively constructing and building infrastructures – and infrastructured labour – a heuristic for changes in labour relations engendered by infrastructure development (as outlined in this issue’s editorial), and on the movement between the two.

Through the case of ALCo in West Africa, or rather its suspension (see below), we argue that infrastructure development as currently structured simultaneously (i) reinforces geopolitical inequities in the division of labour in the design and implementation of infrastructure projects; (ii) fosters competition amongst states for value and trade capture, through ‘local content’ initiatives or the promotion of different transport routes; and (iii) prompts contestation and disavowal in the context of the construction of specific projects. These three distinct, yet inter-related outcomes highlight that the work of imagining and creating infrastructural promises – imbued with inequalities characterising Global South–Global North power relations – creates pathways for novel, and often contested, configurations of labour relations. Likewise, when taken together they help problematise linear or dualistic understandings (success/failure, finished/unfinished, developed/developing) of the reality of infrastructures across the African continent.

‘While scholarly focus has thus far centred the construction of narratives emerging from the realisation of Africa’s ‘infrastructure turn’, novel configurations of power fashioned by infrastructure development (Péclard et al., Citation2020), and practices of labour contestation (Chome, Gonçalves, Scoones, & Sulle, Citation2020), few have questioned the extent to and the ways in which processes of infrastructure development shape the evolution of labour relations (Stokes & De Coss-Corzo, Citation2023; Strauss, Citation2020). In attempting to fill this gap, we draw from work on infrastructure temporalities (Aalders, Bachmann, Knutsson, & Kilaka, Citation2021; Addie, Citation2022; Carse & Kneas, Citation2019; Gupta, Citation2018) and in particular the concept of suspension to explicitly examine the relationship between processes of infrastructure development and changing labour relations as they interface in the ALCo project. To inform our case study, we have combined a review of documents and media reports with observations and interviews with government officials in relevant ministries and construction site workers in Ghana (2022–2023), for which informed oral consent was obtained. By putting the concept of suspension into dialogue with infrastructuring/infrastructured labour in the context of this literature, we aim to contribute to richer understandings of processes of infrastructure design, construction, and usage.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we unpack our understanding of the nexus between infrastructure and labour across space and time. This section outlines our analytical approach centred around infrastructure temporalities. Section 3 details suspension, with a focus on its utility in the subsequent analysis. We then move to our case study in Section 4. Section 4.1 focuses on infrastructuring labour and highlights how infrastructure projects structure labour and ground broader power dynamics. Section 4.2 highlights how infrastructuring labour becomes infrastructured labour, a process that takes place as neat visions of infrastructural development are overlaid onto extant regional power dynamics in West Africa and transformed amidst suspended implementation timelines. This section thus highlights how, in this process, new forms of labour are created. Likewise, in the section we foreground the competition among states for value capture to highlight these processes in the context of the ALCo. Finally, Section 4.3 explores infrastructured labour as well as contestation in the realisation of infrastructure projects along the ALCo route.

2. AFRICAN INFRASTRUCTURES ACROSS TIME AND SPACE

Over the past century, infrastructure development has gone from being en vogue to going out of fashion, to being once more the centrepiece of Africa’s development agenda. Between 2013 and 2017 alone, an average of USD 77 billion per year were devoted to the development of infrastructure projects on the continent (ICA, Citation2018). In 2020, national budget allocations of African countries to the development of transport infrastructure totalled USD 18.6 billion, representing the largest share of infrastructure-related expenditure (ICA, Citation2021). In the words of Nugent, ‘[i]f economic development has become a kind of modern religion, infrastructural investment is once again its most potent fetish’ (Citation2018, p. 22).

In this paper, we distinguish between three discrete, albeit linked, phenomena that are grounded (partly, at least) through infrastructural development: (i) economic globalisation; (ii) geographies of power; and (iii) uneven development. In doing so, we argue for the centring infrastructure temporality as a crucial tool to bring to light the relations between the infrastructure projects themselves and society (materially, discursively, semiotically). We put forward the concept of suspension to explore how multiple temporalities interface in the context of delays and reversals, which are all too common in large-scale projects like the ALCo (Flyvbjerg, Citation2014).

Infrastructures have historically been a crucial component of countries’ development agendas, promoting specific visions of modernity and development in their promise to ‘unlock’ economic development (Harvey, Citation2010). Focusing on different narratives and perceptions of processes of infrastructure development therefore provides insights into the paradoxes of (i) economic globalisation. The predominance of technical rationales and narratives within the context of infrastructural realisation (Mitchell, Citation2002; Mukerji, Citation2011) often leads to the overestimation of benefits and the underestimation of risks. This phenomenon had already been observed by Hirschman (Citation2015) in development projects undertaken in the 1960s and is similarly reminiscent of the ‘paradox of megaprojects’, according to which project costs are underestimated and benefits overestimated (Flyvbjerg & Sunstein, Citation2016).

Infrastructures are also part and parcel of the technological progress underpinning economic globalisation’s space–time compression (Harvey, Citation1989). This is particularly the case for transport infrastructures, which are envisioned to facilitate connectivity amongst places and regions with the goal of reducing transport times and, consequently, costs. In the case of transport corridors, infrastructures are paired with information and communications technology (ICT) systems supporting the harmonisation of trade procedures to reduce border crossing times (Nugent & Lamarque, Citation2022). However, experiences of space–time compressions vary depending on ‘where one stands’ in relation to increasing flows and inter-connections characteristic of the global economy (Castree, Citation2009; Massey, Citation1991). In other words, the ways in which planners, financiers, supporters, opponents, construction workers and prospective users relate to each other and to an infrastructure is shaped by their connections to the project itself, encompassing both possibility and continuity.

The study of the rationales for the provision of infrastructures, the ongoing processes of relationship-building they engender and different instances of contestation illuminate the emergence and establishment of (ii) geographies of power. Infrastructure projects are not to be understood through their outcomes alone, but in light of the symbolism they embody (Müller-Mahn et al., Citation2021). As Mains (Citation2019, p. 2) shows, ‘[i]n contrast to state propaganda, the messiness of construction is striking’. As they are embedded in power dynamics, infrastructures are sites for political contestation (Anand, Citation2017; Carse, Citation2012; Harvey & Knox, Citation2012). This has been highlighted by bourgeoning literature on labour contestation surrounding infrastructure projects (Cezne & Wethal, Citation2022; Kilaka, Citation2024).

In practice, large-scale projects are often launched with confidence and fanfare, yet the vast majority face cost overruns, while up to half – across nearly all contexts – face benefit shortfalls (Flyvbjerg, Citation2014). Poor project-level outcomes can turn into broader macroeconomic risks, particularly for Global South countries, as non-performing loans and rapid debt accumulation can contribute to economic instability, underperformance and capital flight (Ansar, Flyvbjerg, Budzier, & Lunn, Citation2016; Zajontz, Citation2022b). The resultant crises can have significant consequences for labour across scales via spending cuts, for instance, those associated with International Monetary Fund (IMF) austerity and structural adjustment programmes, or slower economic growth. Yet, even as infrastructures cause crises for some, they may lead to gains for others, for instance through increasing land values (Gillespie & Schindler, Citation2022; Goodfellow, Citation2020). Additionally, ideas prominent at the time of infrastructure development and their corresponding power relations, such as capitalist expansion (Hönke, Citation2018; Kanai, Citation2016; Lesutis, Citation2020; Tups and Dannenberg, Citation2021), are often sedimented by infrastructure development (Harvey, Citation2010; Star, Citation1999). Infrastructures therefore are not only experienced distinctly across social formations, but also serve to create or concretise configurations of power across them.

The spatiality of infrastructure also offers insights into evolving patterns of (iii) uneven development. As noted above, infrastructures encompass a myriad of spatial processes which contribute to the reconfiguration of space across different scales. Schindler and Kanai (Citation2021) explore the (re)emergence of spatial planning techniques aimed at the production of territories that can be easily ‘plugged in’ existing global value chains. For instance, in southern Africa, multiple transport corridors converge in Durban Port in South Africa, giving the city increased importance in both material and discursive senses for the South African state and economy. At the national level, Lesutis (Citation2021) highlights states’ (re)territorialisation practices through infrastructure development, speaking to debates on infrastructural practices crucial to the reconfiguration of state spaces.

Yet, following our understanding of infrastructure as mirroring – and co-constituting – the paradoxes of economic globalisation, these projects, in practice, can be understood as being able to create the conditions for both greater or lesser connectivity, the latter for instance in the form of disarticulation (Bair & Werner, Citation2011) or through broader macro-economic crisis (and subsequent outward capital flows) related to debt distress. Africa’s renewed push towards infrastructure development therefore effectively brings with it new forms of territorialisation tied to both capital and labour. In this paper, we make a case for an increased analytical focus on the different temporalities characterising these processes to bring to light the relations between infrastructure and society.

3. SUSPENSION: THE TEMPORALITIES OF DELAY

Infrastructure development is far from being a temporally linear process. On the one hand, infrastructures are shaped and influenced by remnants of pre-existing social relations and physical connections. Contemporary infrastructures are built on the longue durée of racialisation in the global economy, which is reproduced and contested in processes of infrastructure development (Kimari & Ernstson, Citation2020). Additionally, past infrastructure projects, or rather their ruins, often underpin large connectivity projects across the African continent (Aalders, Citation2021; Chen, Citation2022; Enns & Bersaglio, Citation2020). For instance, in Ghana, the road density around Kumasi in the Ashanti Region grew exponentially in the last three decades of colonial rule (Taaffe et al., Citation1963, p. 42). These crucial arteries became the basis of further infrastructure development. The road connecting the capital Accra to Kumasi was expanded as part of the Road Sector Development Programme undertaken between 2002–2008 (WB, Citation2001). More recently, this road is being expanded into a dual carriageway as part of the West Africa Growth Ring Corridor, linking Accra to Kumasi and onwards to Ouagadougou in Burkina-Faso (Ministry of Planning, Citation2018).

On the other hand, infrastructures embody future imaginaries of capitalist modernity (Anand et al., Citation2018; Harvey & Knox, Citation2012; Mkutu et al., Citation2021). Profoundly influenced by what Scott referred to as high modernism, the past is often seen as ‘a history that must be transcended; the present is the platform for launching plans for a better future’ (Citation1998, p. 89). In African national development agendas, this often manifests through a strong emphasis being placed upon the development of brand-new, state-of-the art and often capital-intensive infrastructures, rather than opting for retrofitting existing ones. Images of high-rise buildings, lush seafronts, and automated logistical hubs populate development masterplans hailing a break from the past (Hönke & Cuesta-Fernandez, Citation2018). As such, infrastructures evoke visions of the future centred around the potentialities and promises associated with their realisation (Larkin, Citation2013).

Therefore, infrastructures assemble past and future into powerful narratives of development, ‘turn[ing] the present into an unfolding anticipation’ (Hetherington, Citation2017, p. 42). Anticipation and hope for the future effectively construct ‘infrastructural publics’ – those who will prosper through employment creation and skill training (Lesutis, Citation2022a) and those who are disavowed in the processes of infrastructure development (Lesutis, Citation2022b). Thus, through the creation of new connections across space/time, infrastructures can address pre-existing inequalities – or at least be promoted as such – while simultaneously reinforcing unequal relations of power. As Anand (Citation2012) suggests, infrastructures raise questions amongst those involved as to who will and will not benefit from infrastructure development.

The plurality of possibility in the processes of infrastructure development is particularly evident in the context of project delays and interruptions, as multiple temporalities encounter and tangle in the present taking on novel, unexpected forms. Thinking through these instances via the concept of suspension allows one to closely examine the temporal plurality of a given conjuncture. Suspension becomes particularly useful when analysing large-scale infrastructure projects. Indeed, many of the infrastructure projects part of the development agendas pursued by African countries struggle to reach completion. Whether due to budget shortages, electoral cycles, competing agendas, popular discontent, labour contestation or other controversies, infrastructures are often delayed, postponed or abandoned altogether. The linearity of ‘project time’ – understood as the succession of planning, design, construction, completion and usage – is therefore called into question. The intentionalities of the different actors involved interface and collide throughout the development processes of infrastructures. Likewise the lens of suspension lends itself to thinking through the ways in which one temporality establishes itself as hegemonic, surpassing or supressing others in the process (Clarke, Citation2018).

In this context, the question of when a corridor is, articulated by Nugent and Lamarque (Citation2022, p. 11), becomes particularly relevant as the political, economic and social experiences of corridor development unfold and occur according to different perceptions of time. Addie (Citation2022, p. 114) highlights how different actors’ perceptions of urban infrastructures vary ‘because of their relative temporal vantage points and time horizons’. Similarly, multiple and splintered temporalities coexist within ‘corridor time’ – the assemblage of the dynamic and non-linear temporal unfolding of infrastructural visions, intentionalities and experiences. Prolonged extensions or consecutive reversals can engender a condition whereby different social, economic and political processes characteristic of infrastructure development coalesce and concurrently affect the ways in which labour is produced, transformed and/or destroyed (e.g., through disarticulation).

Suspension is therefore not static, but ‘rather a social process associated with distinct temporal frames, rhythms, and conditions of possibility’, effectively ‘rework[ing] experiences of past, present, and future’ (Carse & Kneas, Citation2019, p. 18). Suspension implies anticipation and hope, as well as exclusion, disillusion, and disavowal. As such, it is the condition ‘between what was promised and what will actually be delivered’ (Gupta, Citation2018, p. 70). By focusing on the time/space between project inception and realisation, suspension opens avenues for infrastructural visions, promises, and broader narratives to be called into question and for novel relations to the processes of infrastructure development to emerge.

Suspension is not devoid of labour, which instead exists in what Carse and Kneas term suspended presents, namely ‘the social experiences associated with infrastructural delay’ (Citation2019, p. 18). In this paper, suspension is therefore the entry point to the analysis of relations between infrastructure and labour. Suspension encompasses the different forms of work materially and ideationally contributing to infrastructure development, and simultaneously embraces the ubiquity of labour in how actors across different levels re-imagine, re-interpret and (at times) re-design infrastructures. Below, we use this framework to critically analyse the ALCo project to highlight how long-standing delays have created the space for multiple lived realities to exist. Our analysis is summarised in .

Table 1. Relationship between infrastructure and labour.

By foregrounding infrastructure temporalities through suspension, we seek to engage in the investigation of both infrastructures’ material and social connectivity. Delays in the implementation of this West African corridor put into question the material existence of the corridor itself. The project currently exists in a liminal space – it is described by those involved in its planning as a crucial element of regional integration, yet its components are oftentimes built without reference to this overarching initiative. Thus, the productive quality of suspension lies in illuminating the variety of processes and uneven potentialities woven into the construction of different forms of infrastructural labour.

4. CRAFTING, COMPETING, REALISING INFRASTRUCTURE: MULTIPLE TEMPORALITIES AND CHANGING LABOUR RELATIONS

4.1. Crafting infrastructure: funding and design

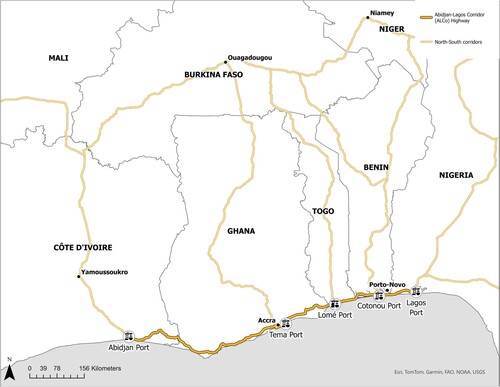

The 1028-km six-carriage ALCo Highway is only one component of the broader ALCo. This corridor seeks to connect West Africa’s largest ports and most populous cities to foster cross-border trade along the coast by establishing One Stop Border Posts (OSBPs) – a single-window border facility designed to reduce travel time and improve efficiency at land crossings – and facilitating landlocked countries’ access to maritime hubs through the integration of North–South corridors stemming from key maritime hubs along the ALCo project (see ). Finding its origin in a multilateral HIV/AIDS-prevention initiative began in the 1990s and formalised in 2002, the ALCo quickly became more than a health intervention initiative. Following a 2006 report in which the governments of Benin and Ghana re-imagined the corridor as useful toward intergovernmental cooperation initiatives, the ‘idea of ALCo as an instrument of regional integration was born’ (Nugent, Citation2022, p. 228).

Figure 1. Map of the proposed Abidjan-Lagos Corridor Highway and its linkages to North-South corridors in West Africa.

In 2014, the heads of state of Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Beinin, and Nigeria signed the treaty for the creation of the corridor, which prompted the establishment of the ALCo Management Authority (ALCoMA) to implement the project. The ALCoMA is a supranational authority involving ministers from partner countries tasked with undertaking the agenda-setting, implementation and oversight of the ALCo. This is reminiscent of similar institutions formed across the continent with the goal of streamlining the development of large infrastructure projects. In Kenya, for instance, the LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority was instituted with the mandate of overseeing the development of the Lamu Port-South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor. While in different contexts, these institutions reproduce the top-down nature of domestic centralised decision-making structures characterising infrastructure development processes (Péclard et al., Citation2020).

The initial labour of imagining and planning infrastructure projects can thus be understood as being performed and/or driven by the interests of different elites, from national governments to ALCoMA and ECOWAS. For example, for the last decade, a committee made up of ministers from the five corridor countries has been working on issues related to legal frameworks, technical standards and fundraising initiatives (Ministry of Roads and Highways, Citation2023). This establishes the character of the project and imbues further processes of implementation with a series of predetermined dynamics. Where infrastructure projects are built, for instance, has long been shaping the economic geography of African nations. At the turn of the twentieth century, colonial investments in physical infrastructures were primarily aimed to safeguard (military) control over colonised territories and ensure the economic viability of the colonies. Within the colonial system, railways played a significant role in shuttling raw materials from the hinterlands to the ports. Initially, funds devoted to railway development represented a large share of the expenditure of colonial regimes. Colonial governments’ railway expenditure in the period between the second half of the 1880s and the beginning of the 1930s amounted to around 30 per cent of total public expenditure in Ghana and French West Africa (Jedwab & Moradi, Citation2013). Railways significantly reduced transportation costs and, in turn, prompted the development of economic ventures along the railway tracks, effectively impacting the geographical distribution of profitable activities in the colonies.

In tandem, major and minor road constructions ramified from these crucial arteries, resulting in improved connections between agricultural and/or mining centres and export hubs in coastal towns. In West Africa, roads were mainly developed in the southern (coastal) regions – considered to be relevant to the export of mineral, natural, or agricultural resources – while northern regions were disregarded unless the presence of valuable resources required otherwise (Porter, Citation2012). Currently, infrastructure development continues to be concentrated in the coastal regions of West Africa and along North–South corridors serving the regions’ main ports (Nugent, Citation2022). Additionally, few linkages were established between the colonies of different European powers (e.g., France and Great Britain), which today manifests in relatively low levels of intra-African trade. Thus, infrastructure development continues to be influenced by colonial patterns of trade and to be crucial to spatial reordering.

In the case of ALCo, the top-down nature of infrastructuring labour – the work that goes into imagining and designing infrastructures – reproduces the extant paradigm, largely hailing from the Global North, where ‘development’ is understood narrowly in terms of GDP growth and trade integration. As Bond (Citation2017) explains, defining development as GDP can problematically leave out a myriad of factors that are particularly significant, for instance, air and land pollution, loss of agricultural land, non-renewable resource depletion, and the negative effects associated with systems reliant on migrant labour. Nevertheless, as infrastructures ‘reflect the ideals of a certain period in time’ (de Goede & Westermeier, Citation2022, p. 4), contributing to their becoming hegemonic, it is not surprising that infrastructure development sediments the centrality of specific discourses and narratives.

Massive infrastructure developments are seen by international financial institutions (IFIs) and state actors as inexorably contributing to poverty reduction and domestic growth. While some studies have confirmed that infrastructures may lower transaction costs and raise productivity (among other benefits), major strategies published by the World Bank, G20 and the African Development Bank (AfDB) largely leave out concerns relating to who gains from infrastructure-led growth (e.g., whether value is captured by domestic firms for instance) or how the projects will fit into existing patterns of trade (Wethal, Citation2019). Thus, while growth may be created, the manner in which it manifests across society is variable and dependent on place-based conditions.

In West Africa, ALCo builds on these established notions. The narratives, discourses, and legitimisations surrounding the project have focused on the construction of broad-based economic benefit via increased cross-port links, the improvement of mobility, and the facilitation of cross-border exchanges (Nwokoro, Citation2022). Dr. Abbas Awolu, Chief Director of Ghana’s Ministry of Roads, for instance, recently stated that the project has ‘potentially massive’ economic and social benefits (Addeh, Citation2022; Ghana Business News, Citation2023). Per the ECOWAS One Road, One Vision report (quoted from Nugent, Citation2022, p. 216), the corridor – understood as a ‘trade and transport’ initiative – ‘will allow the opening of the landlocked countries’. Additionally, the World Bank (Citation2010) has noted that project goals will range from higher transport quality/lower transportation tariffs to the integration of West African companies into globalised supply chains. While infrastructural systems are certainly a necessary component of broader regional growth and development – and a completed ALCo could ultimately play a role in the construction of regional economic resilience via trade diversification or by facilitating sectoral transformation – portraying infrastructure as an end unto itself elides contextual dynamics that may hinder project implementation and benefit creation.

Project suspension in the ALCo has brought to light several tensions between the vision promoted by ALCoMA (and its international supporters) and the ways in which a corridor – in its varied forms – is used in practice. Broadly speaking, ALCo designs are disconnected from extant patterns of connectivity. As Nugent (Citation2022) observes, trucks moving between Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria are a rare sight. The busiest sections of the ALCo are those stemming from major ports serving cross-border exchanges rather than supporting trade along the entirety of the corridor. These dynamics not only call into question the objective of increased and improved connectivity – particularly as intra-regional trade volumes remain relatively low (Luke, Citation2023) – but also disrupt the top-down imagining and planning of the project. As the infrastructuring labour required to resume the project and work towards its completion moves from supranational institutions and IFIs to domestic actors within ALCo countries, the underpinning rationale for the project appears to be on shaky ground in light of increasing competition amongst West African states. An established ALCo could disrupt these undercurrents, yet such transformation requires more holistic change including institutional standardisation – occurring both between and within member countries.

4.2. Competing infrastructure: trade and value capture

Initially scheduled to begin construction in 2018, the ALCo Highway struggled to make progress. Delays are common in infrastructure projects, but their persistence highlights different articulations of the relations between actors and their respective agendas. In other words, delays manifest in the suspension of the transformative vision underpinning the development of the ALCo corridor and also bring to light how different actors contribute to the challenging and (re)shaping of said vision. Indeed, corridor development is characterised by ‘the tension inherent within a form of regionalism that hangs on the vagaries of national politics’ (Nugent & Lamarque, Citation2022, p. 25).

In this section, we focus on the competition amongst West African states for trade and value capture to illuminate the movement between infrastructuring and infrastructured labour. We use these dynamics to highlight how infrastructuring labour is transformed even before the implementation process, as plans are imprinted onto uneven terrains carved by economic and political realities, as well as alternative imaginaries in varying degrees of enactment. For example, different stretches of what may eventually become the ALCo Highway are being designed, developed and built without mention of the broader project, including the Route des Pêches in Benin and the Lagos-Badagry Expressway in Nigeria. These roads bring into focus the constructed nature of corridor temporalities. In the future they may be positioned as part of the broader picture, but, in the present, they – and the lived realities they shape – exist outside of the scope of ALCo. The question of when the ALCo corridor will move from design to reality therefore not only encompasses construction but also integration and narrative-building (and thus the establishment of a hegemonic temporality), which themselves constitute forms of infrastructuring labour.

Similar, albeit larger, processes are presently underway in terms of the regions’ ports. Currently, there are six major port modernisation and development projects underway between Abidjan and Lagos. In 2022, Côte d’Ivoire completed the expansion of Abidjan port (Coulibaly, Citation2022). Ghanian President Akufo-Addo inaugurated two components of the Takoradi Port Expansion Project in 2022 (Ganic, Citation2022) and presided over the ground-breaking ceremony of Tema Port Expansion Phase II in 2023. In Togo, Lomé Port was expanded between 2011 and 2016 and new expansion plans are currently underway (Togo First, Citation2022). In Benin, Cotonou Port is also entering a new phase of port expansion and modernisation (Moraes, Citation2022). Finally, in Nigeria, the development of a new deep-water port project in Lekki seeks to further capture global trade flows and create large scale employment (Olukoju, Citation2023).

It is clear that the suspension of the broader ALCo corridor project has somewhat weakened the rationale for its development. As mentioned, road and port investments have been made without links to, or mentions of, the coastal corridor. Additionally, the development and/or expansion of a multitude of port infrastructures points to the competition amongst (West) African states ‘to produce or reorganise space […] to meet the needs of capital and attract shipping traffic, which in turn is supposed to generate employment opportunities’ (Reboredo & Gambino, Citation2023, p. 4). These ports, however, are not only in direct competition with each other for cargo capture, but also serve different North–South corridors in the region rather than the ALCo.

The ports along the ALCo route ‘stand in a competitive relationship with respect to the transit of trade with the landlocked countries of the Sahel’ (Nugent, Citation2018, p. 36; Citation2022). As Zajontz (Citation2022a, p. 18) suggests, ‘where scalar and territorial articulations of state space do not align, regional corridor infrastructure is marked by patchworks of connectivity’. For instance, the ports of Tema in Ghana, Lomé in Togo and Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire all serve corridors reaching Ouagadougou in Burkina-Faso. In 2010, Burkina Faso accounted for over half of the transit cargo volume in Tema (USAid, Citation2010). In 2016, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA, Citation2016, quoted in Byiers & Woolfrey, Citation2022, p. 28) identified that the majority of Lomé’s transit cargo traffic is destined for Burkina-Faso. In another pertinent example, the port of Cotonou in Benin and the port of Lagos in Nigeria serve corridors connecting Niamey in Niger to maritime transport hubs along the West African coast.

Competition amongst different North–South corridors unfolds in different spheres. First, port efficiency and costs are crucial. The quest for improved efficiency is evident in the competition for port development discussed above. In addition, added costs – such as a USD 200 transit fee to be paid to the Ghanian Central Bank on goods imported from Burkina-Faso through Ghana (Byiers & Woolfrey, Citation2022) or ‘facilitation payments’ at checkpoints (Barka, Citation2012) – can also sway logistics agents and transporters. Second, corridor competitiveness is dictated by transport costs and transport modalities along North–South corridors. For instance, Abidjan is connected to Ouagadougou by rail, while import-export along the Lomé-Ouagadougou Corridor relies on road transport. Olukoju (Citation2020) identifies the Cotonou-Niamey Corridor as the least costly in the region (USD 3938 compared to USD 5095 between Abidjan and Ouagadougou), highlighting how transport price and time along North–South corridors can influence patterns of trade in the region.

Third, speed and safety of travel also play an important factor. Different conditions determine the time–cost of transporting people and goods along African transport corridors. Per Choplin and Hertzog (Citation2020, p. 215), for a trip from Accra to Lomé, ‘the time and cost depend largely on border controls, individual circumstances and goods transported’. While a coach may make the journey in just above the advertised 5 h, a truck carrying goods may take 16 h (Choplin & Hertzog, Citation2020). Once again, the multiple perceptions of ‘corridor time’ emerge at the intersection between infrastructure development and the experiences of those living in, around or through infrastructures.

Fourth, geographical patters of economic activity in West Africa present opportunities and challenges to corridor development. For instance, the mining industry in Niger heavily relies on the Cotonou–Niamey Corridor, whereas the mining industry in Burkina Faso distributes cargo towards both Lomé and Tema (Byiers & Woolfrey, Citation2022). In another example, the ebbs and flows of the West African cement industry can influence intra-regional trade as well as engagement with global supply chains. At a small scale, the proximity of Ghanaian cement factories to the Togo border contribute to this border crossing being the busiest in the region (Olukoju, Citation2023). At a larger scale, the combination of increased demand for construction materials, trade liberalisation policies and the ‘collusion between political and economic actors and interests’ resulted in a sharp increase in cement trucks travelling between Nigeria, Niger and Ghana – but contributed little to the economies of countries they cross (Choplin, Citation2020a, p. 1986, Citation2023). As the ALCo stalls, trade across West African borders appears to continue undisturbed. Intra-African trade in ECOWAS grew from 7.7 percent of total trade in the period between 2010–2015 to 9.4 percent between 2016–2020 (Mold, Citation2022, p. 13). This suggests that new trade links, production networks, and value chains are being established outside the corridor framework. These dynamics also highlight the challenges for those engaged in infrastructuring labour in implementing their vision for regional trade.

Finally, ALCo seeks to incorporate North–South corridors with the coastal corridor route. This prospect highlights that transport corridors can also encompass a range of transport systems and networks. The diverse nature of trade along North–South corridors and the ALCo, however, means that different types of vehicles are needed, effectively rendering the idea of travelling on two distinct corridors farfetched (Nugent, Citation2022). Additionally, fragmented transportation routes and lack of harmonisation of border procedures would increase transportation times and costs were goods to be unloaded, reloaded or stored in between border crossings.

These dynamics highlight how infrastructure projects alone are not enough to engender regional transformation. Rather, material developments must be accompanied by regulatory shifts and standardisations. The suspension of the ALCo project has in turn made these more difficult as policy precedents and path dependencies are created across different scales. Intragovernmental tensions amongst, and beyond, ALCo partner countries rhythmically emerge, return and subside, further delaying the project and diluting the potential of the corridor to promote employment creation along coastal West Africa. It is in the mismatch between different agendas at play – specifically that of regional integration and domestic imperatives to support, protect or justify specific projects – that competition amongst states is fostered. For its part, labour can be understood here as filling the spaces created by processes of delay, interruption and suspension. The uneven deployment and implementation of infrastructuring labour – and its transition to infrastructured labour – transforms both the reality of employment and the imaginaries around it, albeit varying in ways that depend on ‘where one stands’ in relation to the project.

4.3. Realising infrastructure: contestation and disavowal

As highlighted earlier, agendas with different intentionalities and temporalities encounter in the processes of infrastructure development, putting into question the transformative potential the ALCo might have for labour. While corridor development will increase employment opportunities, reduce transport times and facilitate trade, it will also be highly disruptive to existing labour dynamics that are not contingent on corridor realisation. The suspension characterising the development of the ALCo project opens a window into the changes to labour relations engendered by infrastructures. Here, we focus on infrastructured labour emerging from contestation surrounding ‘corridor time’, ensuing anticipation and frequent disavowal.

Contestation amongst different temporalities is most evident in the continuum between slow and fast patterns of connectivity and economic activity, or movement-suspension. On the one hand, this project has an important role in the political imaginary of regional integration. Since the mid-2000s, West African states have been striving to develop infrastructures aimed to support this objective. The mandates of domestic organs have thus been expanded to include regional integration efforts. In Togo and Ghana, for instance, the foreign affairs ministries have been broadened to reflect the centrality of regional integration and were renamed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration.

The fast movement of goods across borders is a priority of the proponents and supporters of the regional integration agenda. The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (Citation2023) highlights the reduction of transport time and costs to improve the free movement of goods and people across West African borders as a key objective. Intra-regional trade is thus seen as ‘the mechanism enabling the creation [of] employment generation activities since tomorrow’s businessowners will require mobility’ (ECOWAS Commission, Citation2017, p. 6). Within this framework, infrastructure projects are seen as key instruments towards reducing transport time and constructing a more efficient regional transportation system.

On the other hand, ALCo is not only made up of ‘connected spaces’, but also of daily, practical encounters as people travel along its roads by car, bus or on foot in search of a job or a place to trade. All manner of quotidian labour, from roadside markets to service centres, is dependent on the current ‘slow pace’ of travel. Choplin and Hertzog (Citation2020, p. 217) note that ‘infringed mobility generates opportunities to trade with travellers as they move up and down’ the corridor. The employment opportunities that arise around busy border crossings and congested roads are often frowned upon by the public authorities tasked with facilitating increasing regional trade flows (Walther et al., Citation2020). As with actors whose interests are tied to the region’s ports, there is significant tension between those who wish to speed up movement along the corridor and those whose livelihood practices – formal or informal – depend on slowing it down.

The apparent incompatibility of these temporalities is particularly stark when focusing on street sellers and hawkers populating the landscape along the ALCo Corridor, as well as along the conjoining North–South corridors. Concerns over road expansion are particularly prominent amongst those making a living along the road, as they attempt to adapt to the disruption to their space of business caused by construction projects (Interview, construction site supervisor, Tema, 23 July 2023). For instance, the dualisation of the Tema-Aflao Road in Ghana has contributed to the displacement of road sellers without permits or land ownership (Interview, government official, Accra, 22 July 2023). This resembles previous findings in Lagos, where the development of transport infrastructures threatened the work of those making a living from roadside stalls (Ikioda, Citation2016). Particularly, Ikioda highlights the impact of road expansion on women traders.

Ten years ago, Klaeger discussed the various commercial activities unfolding along the Accra-Kumasi road in Ghana, where farmers and hunters sell their products on the roadsides, pointing to different ways in which the road ‘appears as a very lively and public place, with a distinctive appeal to its dwellers’ (Citation2013, p. 453). Today, street-side sellers are concentrated around the yet-to-be expanded sections of this road in light of construction work for its dualisation (Ministry of Roads and Highways, Citation2022). Larger lanes, faster traffic, and bypasses to decrease congestion effectively reduce the opportunities for roadside trade. Stasik and Klaeger (Citation2018, p. 154) show how road sellers manage to adapt to ‘the long-term changes of road infrastructures and technologies’. Overcoming initial uncertainty and anxiety caused by these reconfigurations, sellers often re-appropriate roadside spaces. While some sellers on the Accra-Kumasi road moved to large rest stops or nearby markets, others continued to pursue clients on the roadside, arguably with reduced safety due to increased vehicle speed.

In short, street trading struggles to coexist with the imaginaries of modernity promoted through infrastructure development or urban restructuring (Steck et al., Citation2013). These reframings of labour relations in light of infrastructure development are currently underway where road expansion is taking place. Yet, as only 30 percent of this West African coastal highway is a 4-lane road (Choplin & Hertzog, Citation2020, p. 216), they will soon take on a much larger scale. It is through these processes of infrastructured labour that we can view how one temporality – a particular iteration of ‘corridor time’ – overtakes and subverts another.

Other workers and communities along the ALCo route can similarly be enrolled and disenrolled from the processes of infrastructure development as they entail both connection and disconnection. The latter is often tainted with displacement or loss. Beyond the lack of physical connectivity, it also implies being left out, which is ‘exacerbated when one observes others with connections to more desirable futures’ (Mains, Citation2019, p. 190). One stark example is the Route des Pêches linking Cotonou and Ouidah in Benin. Designed to facilitate increased tourism, this project, launched in 2021, is part of the country’s development agenda (Ngueyap, Citation2021). The seafront is envisioned to be widened and rendered ‘attractive’ to tourists by increasing its green spaces (Presidency of the Republic of Benin, Citation2021, p. 122). To do so, different communities of fishers and traders were identified as needing to relocate to nearby lots. As it is common for compensation programmes in contexts of informal land use or livelihoods (Fält, Citation2022; Lesutis, Citation2022a), those without formal permits or land tenure struggled to be included in the government’s relocation programmes, which were promoted as fostering the re-integration of fishing communities after road construction (La Nouvelle Tribune, Citation2021).

The fate of fishers and inhabitants along the Route des Pêches, such as Fiyégnon 1 district near Cotonou, remained unclear for the four years between the relocation announcement and the beginning of new lot allocation. This suspended state is reminiscent of Simone’s understanding of anticipation as ‘the art of staying one step ahead of what might come, of being prepared to make a move’ (Citation2010, p. 62). Temporariness and unfinishedness are frequent temporal qualifiers in the people as infrastructure approach seeking to highlight the ‘relentless collisions between human situatedness, human endeavour and the inheritance of resourced realities’ (Simone, Citation2021, p. 1343). In the Route des Pêches, these collisions materialise both by means of voluntary vacation of lots allotted to road development and forced evictions undertaken through the demolition of settlements (ORTB, Citation2021).

Road construction, nevertheless, also allows the opportunity to employ workers within construction sites. Since the 1990s, a range of policies – many guided by the priorities of IFIs – have been directed towards improving transport conditions in West Africa. This has also included the expansion of labour-based construction schemes (as opposed to machine-based) in the region (see for instance Porter, Citation2012). For example, Ghana introduced the labour-based feeder road programme in 1986, after the intensification of infrastructure development after independence had resulted in low rates of local contractor engagement (Twumasi-Boakye, Citation1996) and (domestic) migrant labour filling construction work openings (Stock & de Veen, Citation1996, p. 61).

This programme, similar to those of other African nations in the same period, presupposed the promotion of labour-intensive construction methods to ensure the widening of benefits derived from road construction. Through the case of cobblestone roads in Ethiopia, Mains (2019, pp. 151–180) outlines how the process of realising infrastructures does not always result in controversies between state interests and labour. The labour-intensive and lengthy construction process characterising cobblestone roads indeed supported the creation of jobs, forgoing – or at least sidelining – the spectacle of asphalt modernity. Nevertheless, as Mains also underlines, while infrastructure can be designed to benefit and support local-bases practices and livelihoods, tensions often emerge between the designed programmes and the expectations of populations experiencing the promises of infrastructure development.

For example, in Ghana, the development of Jamestown’s fishing port has been punctuated by labour controversies. The construction of this Chinese-funded fishing port, valued at USD 50 million, began in 2020. Although few Jamestown residents work in the construction site (Interview, construction worker, Jamestown, 29 July 2022) the project has created employment opportunities for street sellers, mainly women, who now sell ready-made lunches to Ghanaian construction workers. The latter, unhappy with the food made available by the company, are now provided additional small payments to buy lunch independently. The project has also encountered resistance from its construction workers around pay, overtime or holiday shifts and the lack of healthcare provision (Interview, construction site supervisor, Jamestown, 28 June 2022). This resulted in negotiations between the Ghana Construction and Building Materials Workers Union of Trades Union Congress (CBMWU) and the Chinese construction company China Railway Construction Company (CRCC), leading to the signing of a collective bargaining agreement.

This collective bargaining agreement included recognition of the role of trade unions within and beyond this workplace, individual and collective labour rights, as well as workers’ provisions (such as insurance or holiday pay). Concerning negotiated provisions for construction workers in the Jamestown Port project, the agreement outlined salary multipliers, insurance, and occupational healthcare provision (CRCC and CBMWU, Citation2022). Though these can, at times, be ignored by company managers (Akorsu & Cooke, Citation2011), the signing of collective bargaining agreements signals that labour unions are increasingly crafting spaces to contribute to the reshaping of labour relations and expanding their presence in the international construction sector.

Beyond construction, newly built infrastructures can also create opportunities for sectoral expansion, such as in the case of real estate, and thus result in the accelerated transformation of formerly rural places. The building of highways or multiple carriage roads, and the resulting speeding up of transit, can quickly change land value geographies and lead to urban expansion. Gillespie and Schindler (Citation2022) note that infrastructure construction in both Ghana and Kenya has created prospects for land rent appropriation by actors operating across different levels. They suggest that infrastructure development has established conditions conducive to rentier capitalism wherein accumulation is predicated on the control of rent-generating assets rather than productive activities.

Returning to the ALCo, recent reports detail that highway construction will begin in 2024 and proceed in three phases (Ghana Business News, Citation2023). The first entails the construction of roughly 300 km of roads between Abidjan to Elubo-Apimanim Junction in Ghana. The second entails the Ghanaian section of the project, covering some 450 km, while the third lot will include 320 km of roads across Togo, Benin and Nigeria. Considering the staggered pace at which construction proceeds and the difficulties engendered by varying types of terrain (e.g., urban, peri-urban, rural), the highway project will affect areas differently. For example, extant dynamics relating to informal livelihood strategies like those detailed above will exist longer in some places than in others. The transformation of labour along the ALCo Highway can therefore be understood as hybridised, with suspension persisting along certain stretches while not in others and new opportunities being created by the processes of project implementation.

Such transformations are increasingly visible across the ALCo Corridor as city peripheries are in the process of large-scale land use change amidst the creation of polycentric nodes. For instance, as Choplin and Hertzog (Citation2020) document, the transformation of rural to urban in the region in turn reshapes patterns of economic and social activity. As the authors note ‘quite often these spaces are still officially considered rural and lack public infrastructure […] at the same time, numerous private schools and evangelical churches set up shop in remote and poor areas and are markers of a city-less urbanisation’ (Choplin & Hertzog, Citation2020, 1984). Such processes are accelerated via the time–space compression engendered through mega-development projects such as the ALCo. Yet, as we have documented in this paper, the project’s transformative effects are hybrid both in their materiality and temporality, and thus interface with, rather than replace, extant social and economic formations.

5. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we explored the relations between infrastructure development and labour. Delineating the relationship between infrastructuring labour and infrastructured labour, as well as the movement between the two, we have documented the trans-scalar effects of the ALCo project. Considering the delays in project implementation, we have chosen to foreground the concept of suspension to explore how multiple temporalities interface in the context of project delays and reversals. This is highly significant in the case of ALCo, as the project has now been under successive delays and stoppages for several decades.

Throughout this paper, we have argued that the largely top-down design/implementation of the project manifests as a reinforcing push of extant global inequalities. Considering the discourses and dynamics behind the project, the initial labour relating to the ALCo can be understood as largely driven by elite interests promoting orthodox economic systems. This establishes the character of the project and reproduces a paradigm where ‘development’ is narrowly understood in terms of GDP growth and trade integration. The narratives surrounding the ALCo have focused on this pair, yet little has been written about the particularities of growth and accumulation. As noted above, the project – particularly in its current suspended state – does not simply supersede current structures, rather it entangles with these and, through these processes, creates new dynamics, such as fostering competition between states for value capture. We have shown that ALCo planners have had to respond to current dynamics, which include the competition amongst different corridors and the intensification of large-scale development in port infrastructures across the corridor.

Finally, we have argued that infrastructured labour – the ways in which infrastructures affect/shape labour relations around the projects themselves – prompts contestation and disavowal, yet likewise creates opportunities for those involved. In a sense, we view the project as transformative, but those transformations are contextually and temporally situated rather than simply creating a new even landscape on the ruins of the old. The case of tensions relating to construction work, informal livelihood strategies, and new manifestations of rentier capitalism across the projects’ proposed route highlight these processes, as well as the ways in which infrastructures both change and are changed by labour.

Overall, this paper contributes to the current understanding of the relationship between infrastructures and labour by bringing to the forefront the ways in which said relations are crafted, contested, and re-imagined around infrastructure development. We highlighted how the processes of envisioning and constructing infrastructure are influenced by power relations characterising Global North-Global South encounters and gives rise to novel and often contested forms of labour relations. In doing so, we foreground a processual understanding of this relationship, making a case for the centring of temporality in the study of infrastructuring and infrastructured labour.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) for the project titled ‘Chinese Expertise in Transnational Governance' (ref no. 48839).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the editors, the three anonymous reviewers and the guest editors for their constructive and useful feedback on earlier drafts. We also gratefully acknowledge the help of Davide Zoppolato in designing the map.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Aalders, J. T. (2021). Building on the ruins of empire: The Uganda Railway and the LAPSSET corridor in Kenya. Third World Quarterly, 42(5), 996–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1741345

- Aalders, J. T., Bachmann, J., Knutsson, P., & Kilaka, B. M. (2021). The making and unmaking of a megaproject: Contesting temporalities along the LAPSSET corridor in Kenya. Antipode, 53(5), 1273–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1741345

- Addeh, E. (2022). Fashola: Construction of $15.6bn Abidjan-Lagos Highway to Benefit 40 m West Africans, ThisDay. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2022/06/06/fashola-construction-of-15-6bn-abidjan-lagos-highway-to-benefit-40m-west-africans

- Addie, J. P. D. (2022). The times of splintering urbanism. Journal of Urban Technology, 29(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2021.2001716

- African Development Bank. (2022). The Africa investment forum: Catalyzing financing for game-changing Abidjan-Lagos highway project, African Development Bank - Building today, a better Africa tomorrow. African Development Bank Group.

- Akorsu, D. A., & Cooke, F. L. (2011). Labour standards application among Chinese and Indian firms in Ghana: Typical or atypical? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(13), 2730–2748. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.599941

- Anand, N. (2012). Municipal disconnect: On abject water and its urban infrastructures. Ethnography, 4(4), 487–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435743

- Anand, N. (2017). Hydraulic city: Water and the infrastructures of citizenship in Mumbai. Duke University Press.

- Anand, N., Gupta, A., & Appel, H. (2018). The promise of infrastructure. Duke University Press.

- Ansar, A., Flyvbjerg, B., Budzier, A., & Lunn, D. (2016). Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic fragility? Evidence from China.

- Appel, H. C. (2012). Walls and white elephants: Oil extraction, responsibility, and infrastructural violence in Equatorial Guinea. Ethnography, 13(4), 439–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138111435741

- Bair, J., & Werner, M. (2011). The place of disarticulations: Global commodity production in La Laguna, Mexico. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 43(5), 998–1015. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43404

- Barka, H. B. (2012). Border posts, checkpoints, and intra-African trade: Challenges and solutions. African Development Bank.

- Bond, P. (2017). Uneven development and resource extractivism in Africa. In Routledge handbook of ecological economics (pp. 404–413). Routledge.

- Byiers, B., & Woolfrey, S. (2022). The political economy of West African integration: The transport sector on two port corridors. In P. Nugent, & H. Lamarque (Eds.), Transport Corridors in Africa (pp. 102–128). James Currey.

- Carse, A. (2012). Nature as infrastructure: Making and managing the Panama Canal watershed. Social Studies of Science, 42(4), 539–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312712440166

- Carse, A., & Kneas, D. (2019). Unbuilt and unfinished. Environment and Society, 10(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2019.100102.

- Castree, N. (2009). The Spatio-temporality of Capitalism. Time & Society, 18(1), 26–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X08099942

- Cezne, E., & Wethal, U. (2022). ‘Reading Mozambique’s mega-project developmentalism through the workplace: Evidence from Chineseand Brazilian investments’. African Affairs, 121(484), 343–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adac019

- Chen, Y. (2022). Following the Tracks: Chinese development finance and the Addis-Djibouti Railway Corridor. In H. Lamarque, & P. Nugent (Eds.), Transport corridors in Africa (pp. 262–285). James Currey.

- China Railway Construction Company Harbour and Engineering Bureau Group and Ghana Construction and Building Materials Workers Union of Trades Union Congress. (2022). Collective Bargaining Agreement between CRCC and CBMWU. Jamestown, Ghana.

- Chome, N., Gonçalves, E., Scoones, I., & Sulle, E. (2020). “Demonstration fields”, anticipation, and contestation: Agrarian change and the political economy of development corridors in Eastern Africa. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14(2), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2020.1743067

- Choplin, A. (2020a). Cementing Africa: Cement flows and city-making along the West African corridor (Accra, Lomé, Cotonou, Lagos). Urban Studies, 57(9), 1977–1993. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019851949

- Choplin, A. (2023). Concrete city: Material flows and urbanisation in West Africa. John Wiley & Sons.

- Choplin, A., & Hertzog, A. (2020). The West African corridor from Abidjan to Lagos: A megacity-region under construction. In D. Labbé & A. Sorensen (Eds.), Handbook of megacities and megacity-regions (pp. 206–222). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Clarke, J. (2018). Finding place in the conjuncture: A dialogue with Doreen. The Open University: Open Research Online.

- Coulibaly, L. (2022). Ivory Coast completes second shipping container terminal. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/ivory-coast-completes-second-shipping-container-terminal-2022-11-25/

- de Goede, M., & Westermeier, C. (2022). Infrastructural geopolitics. International Studies Quarterly, 66(3), 0–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqac033

- ECOWAS Commission. (2017). Abidjian-Lagos Corridor: One Road - One Vision. African Development Bank.

- Enns, C., & Bersaglio, B. (2020). On the coloniality of “new” mega-infrastructure projects in East Africa. Antipode, 52(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12582

- Fält, L. (2022). On the governing of ‘gray’ trading spaces in Accra: Multiple powers and ambiguous worlding practices. International Development Planning Review, 44(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2021.2

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2014). What you Should Know about Megaprojects and Why: An Overview. Project Management Journal, 45(2), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.21409

- Flyvbjerg, B., & Sunstein, C. R. (2016). The principle of the malevolent hiding hand; or, the planning fallacy writ large. Social Research, 83(4), 979–1004. http://www.socres.org/single-post/2017/03/06/Vol-83-No-4-Winter-2016 https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2016.0063

- Ganic, E. (2022). Akufo-Addo inaugurates two development projects at Takoradi Port. Dredging Today. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.dredgingtoday.com/2022/12/09/akufo-addo-inaugurates-two-development-projects-at-takoradi-port/

- Ghana Business News. (2023). Construction work on Abidjan-Lagos Corridor Highway to commence next year’, 10 March. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.ghanabusinessnews.com/2023/03/10/construction-work-on-abidjan-lagos-corridor-highway-to-commence-next-year/

- Gillespie, T., & Schindler, S. (2022). Rentier capitalism and urban geography in Africa. Review of African Political Economy, 49(174), 531–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2023.2171284.

- Goodfellow, T. (2020). Finance, infrastructure and urban capital: The political economy of African “gap-filling”. Review of African Political Economy, 47(164), 256–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2020.1722088

- Guma, P. K. (2022). The Temporal Incompleteness of Infrastructure and the Urban. Journal of Urban Technology, 29(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2021.2004068

- Gupta, A. (2018). The future in ruins: Thoughts on the temporality of infrastructure. In N. Anand, A. Gupta, & H. C. Appel (Eds.), The promise of infrastructure (pp. 62–79). Duke University Press.

- Hagberg, S., & Körling, G. (2016). Urban land contestations and political mobilisation : (Re)sources of authority and protest in West African municipalities. Social Anthropology, 24(3), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12312

- Harvey, D. (1989). The condition of postmodernity. Blackwell.

- Harvey, P. (2010). Cementing relations: The materiality of roads and public spaces in Provincial Peru. Social Analysis, 54(2), 28–46. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2010.540203

- Harvey, P., & Knox, H. (2012). The enchantments of infrastructure. Mobilities, 7(4), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2012.718935

- Hetherington, K. (2017). Surveying the future perfect: Anthropology, development and the promise of infrastructure. In P. Harvey, C. Jensen, & A. Morita (Eds.), Infrastructures and social complexity (pp. 40–50). Routledge.

- Hirschman, A. O. (2015). Development projects observed. First Edition 1967. Brookings Institution Press.

- Hönke, J. (2018). Beyond the gatekeeper state: African infrastructure hubs as sites of experimentation. Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal, 3(3), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2018.1456954

- Hönke, J., & Cuesta-Fernandez, I. (2018). Mobilising security and logistics through an African port: A controversies approach to infrastructure. Mobilities, 13(2), 246–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1417774

- Ikioda, F. (2016). The impact of road construction on market and street trading in Lagos. Journal of Transport Geography, 55, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.11.006

- Infrastructure Consortium for Africa (ICA). (2018). Infrastructure financing trends in Africa – 2018. Abidjan.

- Infrastructure Consortium for Africa (ICA). (2021). Spending by African governments on Infrastructure, ICA. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.icafrica.org/en/topics-programmes/spending-by-african-governments-on-infrastructure/

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (2016). Projet du Plan Directeur de l’Aménagement des Réseaux Logistiques pour l’Anneau de Croissance en Afrique de l’Ouest [Draft master plan for the development of logistics networks for the growth ring in West Africa]. Rapport d’Avancement.

- Jedwab, R., & Moradi, A. (2013). Colonial investments and long-term development in Africa: Evidence from Ghanaian railroads. In. American economic association conference 2012.

- Kanai, J. M. (2016). The pervasiveness of neoliberal territorial design: Cross-border infrastructure planning in South America since the introduction of IIRSA. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 69, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.10.002

- Kilaka, B. M. (2024). Contested practices: Controversies over the construction of Lamu Port in Kenya. In J. Hönke, et al. (Ed.), Africa's global infrastructures: South-south transformations in practice (pp. 127–156). Hurst.

- Kimari, W., & Ernstson, H. (2020). Imperial remains and imperial invitations: Centering race within the contemporary large-scale infrastructures of East Africa. Antipode, 52(3), 825–846. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12623

- Klaeger, G. (2013). Dwelling on the road: Routines, rituals and roadblocks in Southern Africa. Africa, 83(3), 446–469. https://doi.org/10.1353/afr.2013.0038

- La Nouvelle Tribune. (2021). Bénin: CE que l’exécutif propose aux déguerpis de xwlacodji et de la Route des pêches [Benin: what the executive offers to those displaced from Xwlacodji and the fishing route], La Nouvelle Tribune, 18 Sept. Retrieved April 02, 2024, from https://lanouvelletribune.info/2021/09/benin-ce-que-lexecutif-propose-aux-deguerpis-de-xwlacodji-et-de-la-route-des-peches/

- Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

- Lesutis, G. (2019). Spaces of extraction and suffering: Neoliberal enclave and dispossession in Tete, Mozambique. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 102, 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.002

- Lesutis, G. (2020). How to understand a development corridor? The case of Lamu Port–South Sudan–Ethiopia-Transport corridor in Kenya. Area, 52(3), 600–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12601

- Lesutis, G. (2021). Infrastructural territorialisations: Mega-infrastructures and the (re)making of Kenya. Political Geography, 90, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102459.

- Lesutis, G. (2022a). Infrastructure as techno-politics of differentiation: Socio-political effects of mega-infrastructures in Kenya. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 47(2), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12474

- Lesutis, G. (2022b). Politics of disavowal: Megaprojects, infrastructural biopolitics, disavowed subjects. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 112(8), 2436–2451. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2022.2062292

- Luke, D. (2023). How Africa trades. LSE Press. https://doi.org/10.31389/lsepress.hat

- Mains, D. (2019). Under construction: Technologies of development in urban Ethiopia. Duke University Press.

- Massey, D. (1991). A Global Sense of Place. Marxism Today, (June):24–29.

- Ministry of Planning. (2018). Summary of West Africa growth corridor master plan.

- Ministry of Roads and Highways. (2023). Abidjan-Lagos Corridor Highway project game changer: Dr Bawumia. Government of Ghana. https://mrh.gov.gh/abidjan-lagos-corridor-highway-project-game-changer-dr-bawumia/

- Ministry of Roads and Highways of Ghana. (2022). Construction of 4 major by-passes on Accra-Kumasi highway to start in March 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://mrh.gov.gh/construction-of-4-major-by-passes-on-accra-kumasi-highway-to-start-in-march-2022/

- Mitchell, T. (2002). Rule of experts: Egypt, techno-politics, modernity. University of California Press.

- Mkutu, K., Müller-Koné, M., & Owino, E. A. (2021). Future visions, present conflicts: The ethnicized politics of anticipation surrounding an infrastructure corridor in northern Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 15(4), 707–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2021.1987700

- Mold, A. (2022). The Economic significance of intra-African trade. Brookings. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Economic-significance_of_intra-African_trade.pdf

- Moraes, C. (2022). Eiffage consortium wins contract to renovate Port of Cotonou in Benin, Construct Africa. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.constructafrica.com/news/eiffage-consortium-wins-contract-renovate-port-cotonou-benin

- Mukerji, C. (2011). Jurisdiction, inscription, and state formation: Administrative modernism and knowledge regimes. Theory and Society, 40(3), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-011-9141-9

- Müller-Mahn, D., Mkutu, K., & Kioko, E. (2021). Megaprojects—mega failures? The politics of aspiration and the transformation of rural Kenya. The European Journal of Development Research, 33, 1069–1090. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-021-00397-x.

- Ngueyap, R. (2021). Le Bénin démarre les travaux de la phase 2 de la Route des pêches [Benin begins work on phase 2 of the Fisheries Route], Agence Ecofin, 8 March 2021. Retrieved January 04, 2024, from https://www.agenceecofin.com/transports/0503-85874-le-benin-demarre-les-travaux-de-la-phase-2-de-la-route-des-peches

- Nugent, P. (2018). Africa’s re-enchantment with big infrastructure: White elephants dancing in virtuous circles?. In J. Schubert, U. Engel, & E. Macamo (Eds.), Extractive industries and changing state dynamics in Africa: Beyond the resource curse (pp. 22–40). Routledge.

- Nugent, P. (2022). When is a corridor just a road? Understanding thwarted ambitions along the Abidjan–Lagos Corridor. In H. Lamarque, & P. Nugent (Eds.), Transport Corridors in Africa (pp. 211–230). James Currey.

- Nugent, P., & Lamarque, H. (2022). Transport corridors in Africa: Synergy, slippage and sustainability. In Transport Corridors in Africa (pp. 1–34). James Currey.

- Nwokoro, S. (2022). ECOWAS reiterates importance of Abidjan-Lagos corridor highway project, THe Guardian Nigeria News. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://guardian.ng/news/ecowas-reiterates-importance-of-abidjan-lagos-corridor-highway-project/

- Olukoju, A. (2020). African seaports and development in historical perspective. International Journal of Maritime History, 32(1), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0843871419886806

- Olukoju, A. (2023). Nigeria’s new Lekki port has doubled cargo capacity, but must not repeat previous failures, The Conversation. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from http://theconversation.com/nigerias-new-lekki-port-has-doubled-cargo-capacity-but-must-not-repeat-previous-failures-197426

- ORTB. (2021). Cotonou: sur la Route des pêches, les habitations illégales délogées de force [Cotonou: on the Fishing Route, illegal dwellings forcibly evicted], Office de Radiodiffusion et Télévision du Bénin, 14 Sept 2021, Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://ortb.bj/a-la-une/route-des-peches-les-habitations-illegales-delogees-de-force/

- Péclard, D., Kernen, A., & Khan-Mohammad, G. (2020). États d’émergence. Le gouvernement de la croissance et du développement en Afrique. Critique Internationale, 89(4), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.3917/crii.089.0012

- Porter. (2012). Reflections on a century of road transport developments in West Africa and their (gendered) impacts on the rural poor. EchoGeo, 20, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.13116.

- Presidency of the Republic of Benin. (2021). Government action programme 2021–2026.