ABSTRACT

This article briefly discusses the two organising groups that I was a part of and their political transitions brought on by the pandemic. Drawing on my experience as a framework, the article provides a brief description of both the organisations and explicate the transitions. In the latter half of the article, I dwell upon the implications of this on organising and proceed to draw upon work of Black scholars and activists to argue for the breakdown of the contested binary of the personal and the political for an organising ethic based on solidarity.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

As the first lockdown was announced in London, shutting down the city in a matter of hours, COVID had already been making global waves. There was chaos in the streets and the supermarkets, schools and universities shut, travel plans cancelled, it became clear that I would be spending lockdown by myself unable to return home. A few days after, I was scrolling through my social media and came across the Islington Mutual Aid group which already had over 500 members, and joined it. Being by myself meant I could volunteer and go out without any issue of carrying the virus to anyone, and I wanted to know my neighbours who would be the only contact for the next few months (hopefully). Everyone thought the situation entailed a friendly socially distant wave, or getting to know each other’s pets; almost no one thought that in a few months, we would be going to Black Lives Matter and the Sarah Everard solidarity protests together.

This article briefly discusses the two organising groups that I was a part of and their political transitions brought on by the pandemic. Drawing on my experience as a framework, the article provides a brief description of the groups and explicate the transitions. In the latter half of the article, I dwell upon the implications of this on organising and draw upon the work of Black scholars and activists to argue for the breakdown of the contested binary of the personal and the political for an organising ethic based on solidarity.

Following the political agitation in India against the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 (Government of India Citation2019), academics based in the UK had come together to form a group called South Asian Students Against Fascism (Henceforth, SASAF). The central purpose of this group was to organise protests in solidarity with those in India (Khan Citation2020), to raise awareness internationally about the political suppression going on along with countering the pro-government media narrative. The main organising space for SASAF were universities and outdoor spaces, members mobilising repeatedly in specific spaces such as SOAS, leading to greater representation from Universities located in Central London. Though this may have been restrictive towards students residing in other locations, it also resulted in the members forming not just political alliances with students from other disciplines, but also friendships which only grew after each protest.

These friendships were always definitely political and functioned on a shared assumption of solidarity towards each other. I, for one, a cis-women naturally assumed the group to be an intersectional feminist one. Folks with strong Marxist leanings naturally assumed the group to have a primarily Marxist-Leninist underlining. I emphasise upon the word ‘assumed’ because this was never objectively discussed, in hindsight it was probably the urgency of the time, but the consequences of these unsaid assumptions were to create ripples soon enough.

The lockdown, while bringing the world to a standstill, also brought this bunch of determined and energetic students to pause and reflect. As desperate calls for funds for organisations working in India to deal with the suddenly imposed lockdown came to us, our attention was diverted to providing immediate material support to the most marginalised groups in India. In addition, many students were worried about not being able to return home or having to spend the lockdown alone in their student accommodations. During the first few weeks of the pandemic, there was little activity on the group’s social media which was originally used to coordinate meetings and protests. Lists for emergency funds and resources for international students were shared which were welcomed by all members. Then, there was a suggestion of a video conference where the aim was not to discuss the next protest, but rather to check-in with each other and offer some semblance of normalcy during very unpredictable times. Soon, these meetings would become a regular part of lockdown life.

The conversations were almost always political, focusing on the ongoing crisis and speculating about the implications of the pandemic on South Asia. Fundraisers were organised for minoritized communities in India and Twitter storms were planned, shifting our protests to an online platform. However, there also emerged a friendship and comradeship, and apart from activism, we were learning to express care and solidarity through encrypted video platforms (like Jitsi), where we organised a fortnightly reading group and general virtual meet-ups where we got to know each other’s families, bid adieu to members leaving for India amidst promises to meet each other again, in a different place and time.

It seemed to be an open and safe space, where people with similar political convictions turned into even stronger friends. However, the aforementioned assumptions began to play a critical role in the group dynamics, and people with more academic seniority (for example, me as a Doctoral Researcher) or ‘activist seniority’ (those involved in activism for a longer time) came to dominate and define group conversations and actions. This centralisation of power with a few individuals was based on manufactured consent of the members, wherein a member who might not be comfortable with the majority’s language would not have explicitly reported how using selective languages was exclusionary, but their silence was taken as consent to be excluded. The lack of communication on structural issues within the group due to fear of offending personal relationships led to a situation where a member of a minoritized gender identity tried to raise these issues, they were firstly silenced, and secondly, had their concerns dismissed. At the time, I was focused on maintaining cordiality rather than addressing problems and my subsequent intervention was tone-policed and discarded. Successive efforts by several members to restart conversation failed due to a lack of will on part of those holding power to mobilise the group. After few failed attempts, the group was reduced to WhatsApp, occasionally sharing details of online events. Despite this, during the peak of the pandemic, the group offered comfort, intellectual and critical discussions, and a support system for its members.

Simultaneously, the local mutual aid group that I joined had sprung into action with certain people taking lead coordination responsibilities. This was an area-specific group focused on ensuring that all neighbours would have access to necessities – food, medicines, gas and electric, a helpline where people could call with their requests and offer a friendly conversation in case someone felt lonely. We communicated on social media and occasionally through windows with a general feeling of thought and concern towards the neighbourhood, a welcome change from regular life in London. As the Black Lives Matter movement spread globally following the murder of George Floyd on 25 May 2020, some members would post details of solidarity marches and gatherings happening locally along with urgent requests for speakers or face masks from community organisers. Soon after, a member highlighted how such posts were against what the group was formed for – which was to provide community support and not ‘do politics’. In response, a lead coordinator shared an article clearly marking the political nature of the group. The article, authored by the founder of Mutual Aid UK, was about the history of Mutual Aid Communities based on the legacy of groups such as the ‘Black Panther Party, Race Today, OWAAD (Organisation for Women of African and Asian Descent) and Black supplementary schools’ (Zuri Citation2020) -explicitly political and community centred organisations. This effectively politicised the identity of the group, shifting its focus from neighbourhood voluntarism to solidarity building as many of the members openly declared their support for the BLM Movement, discussed contentious issues with their neighbours while also finding support for their ideas and, once the pandemic permitted, joined marches together (in a socially distant manner).

In one such gathering at Highbury Fields, I spoke to couple of other neighbours and members of the group, mostly Black people and some South Asians, to check-in with them. We reflected upon the need for more local events as large gatherings in Central London became heavily policed and threatening, especially towards us – racialised people and those on precarious visas. This shared concern enabled us to reflect upon what our specific needs within these larger protests might be, while the enthusiasm of our predominantly white members to be an active, anti-racist part of the moment, worked as a catalyst for political conversations and building solidarity. Acknowledgement of the fact that we all had different levels of privilege and oppression was extremely important, helping to build trust amongst members in that dire situation. People with secure jobs were willing to contribute financially to a community fund, and white folks were willing to take the front line in protests and take on the responsibility of educating other white folks on white privilege and systematic racism. The sense of shared responsibility towards an anti-racist agenda, while challenging to those who resisted, worked to create a ‘friendly neighbourhood’ that went beyond the norm of simply remembering your neighbour when out of sugar to a community where people cared about each other’s wellbeing and, more importantly, learnt from one another.

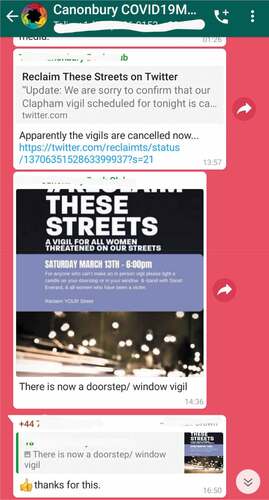

In the above cases, we note that the pandemic and the ongoing political climate contributed to shifts within both groups – SASAF turning into a group that centred personal concern for each other and channelling that into political organising while the local Mutual Aid group became a space for people to discuss their political concerns and participate collectively in social movements. Even before the vigil for Sarah Everard was announced, folks had already started sharing emergency contacts for women, followed by updates on meetings on #ReclaimTheseStreets, local and London protests (See ).

Figure 1. Screenshot of information relating to the vigil for Sarah Everard being shared on the Mutual Aid Whatsapp group..

This break between the distinction of the personal and the political transformed the respective groups, their organisational aims and the people involved. They were now bound by renewed ties of solidarity based on compassion and political discussions centring the government’s actions during the pandemic and building up to larger conversations on capitalism, institutional racism within the UK, gender rights, allyship and so on. This is reflective of the fluidity such groups possess and highlights the agency of the individual to bring structural change through practises of care and building solidarity.

During the BLM movement, as folks discussed, at times passionately argued, I was reminded of bell hooks stressing the ethics of love as a liberatory practise (Hooks Citation2000). Drawing upon the work of Black revolutionaries such as Martin Luther King Jr., she stresses on the importance of self-love (for Black communities) and of collective love. It is this collective love that challenges masculinist conceptions of love (the culture of domination based on violence), derives strength from the individuals who have decided to choose love, and enables people to live in a community, in joy and struggle. Any kind of structural transformation, whether it be struggling for access for those previously denied, or urgent political reforms, occurs over a long period of time and in various phases. A movement that is sustainable depends on ‘compassion and insight’ towards all involved (Macy Citation2017). Our spaces provided space for individuals to share their pain and anxieties, whether it be concern for an ailing family member or anger towards non-payment of salaries/stipends, and for others to offer compassion. In turn, this collective approach to dealing with grief with very limited human contact created trust between neighbours and fellow organisers so they could channel their thoughts, grief, frustration and energies into political organising with solidarity at its core – solidarity with marginalised groups and essential workers.

The continued adherence to these ideas reflected in the Islington Mutual Aid group could also be observed in the former members of SASAF. The period of disruption served as a period of immense growth for several of us. Personally, it challenged my theoretical understanding of solidarity and allowed me to ‘do’ with knowing and critical reflection, practising a decolonial praxis (Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018). Motivated by hard-working and passionate people alongside me, three of us, Jo N, Arshita Nandan and I organised a workshop as part of the Difference Festival (University of Westminster Citation2021). The aim was to centre identities which have been hitherto marginalised to create a space where difference is integral to empowering solidarity. The event, attended by activists, students and lecturers from across the world, serves as a model on how tough conversations to actively fight exclusion can and must be held in order to move beyond performative allyship to effective solidarity.

The above is not reflective of all mutual aid groups or student activist groups across the UK nor does it assess the impact of the pandemic on such associations. Instead, it seeks to highlight transitions within two groups and traces their source to the centring of compassion and care to build solidarities to create sustainable community movements. bell hooks wrote how the ethics of love involves incorporating knowledge, compassion, respect, trust and care into all spheres of life (Hooks Citation2000) and as I write this article in March 2021, a year after Islington Mutual Aid was born in March 2020, the group is actively providing support to the local community for dealing with another lockdown and sharing petitions demanding vaccines for retail workers and details of a laptop donation drive for students. It is continuing on its well-established ethic of love and compassion towards all, reiterating the argument made by many Black and indigenous scholars over the years, that we can only move beyond oppression by choosing love, for ourselves and I’d argue, more importantly, for the collective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Annapurna Menon

Annapurna Menon is a Visiting Lecturer and Doctoral Researcher at the University of Westminster. Her current research focuses on the coloniality of postcolonial nation-states where her focus is on India.

References

- Government of India. 2019. “Citizenship (Amendment) Act.” The Gazette of India. Accessed 17 January 2021. http://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2019/214646.pdf

- Hooks, B. 2000. All About Love: New Visions. USA: Harper.

- Khan, R. 2020. “London: Indian Students, Diaspora Organise Sit-in outside High Commission.” The Wire, 9th Jan. Accessed 17 February 2021. https://thewire.in/rights/london-indian-students-sit-in-caa

- Macy, J. 2017. “The Shambala Story.” themoonschool. Accessed 17 January 2021. http://www.themoonschool.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/the-shambhala-warrior.pdf

- Mignolo, W. D., and C. E. Walsh. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham; London: Duke University Press.

- University of Westminster. 2021. “The Difference Festival 2021.” University of Westminster. Accessed 19 March 2021. https://www.westminster.ac.uk/events/difference-festival-2021.

- Zuri, E. K. 2020. “‘We’ve Been Organising like This since Day’ – Why We Must Remember the Black Roots of Mutual Aid Groups.” Gal-Dem (n.d). Accessed 17 January 2021. https://gal-dem.com/weve-been-organising-like-this-since-day-why-we-must-remember-the-black-roots-of-mutual-aid-groups/