ABSTRACT

This paper addresses an analytical gap in critical security studies related to the social construction, legitimation, and institutionalisation of referents objects, or the ‘for whom’ of security. As it lays out, referent objects tend to be assessed based on pre-theoretical commitments that themselves fall outside of the scope of critical security analysis. This has important analytical and ethical consequences, which I heuristically illustrate in relation to ‘the individual’ in both Copenhagen School securitisation theory and human-centred security. In one case, the individual is understood as an atomised Hobbesian figure at odds with the collective, and in the other, as a socially embedded figure representative of humanity. Incommensurate ontological baselines have on the one hand stymied fruitful dialogue between these two influential approaches. More importantly, however, fixed perspectives on ‘the individual’ have also served to limit each approach’s purview, even on their own terms. In highlighting the value of de-naturalising ‘the individual,’ I lay out a broader argument for problematising referent objects more generally, as a more productive way of thinking about security that moves the conversation beyond practically endless articulations of potential danger. Overall, I argue that the intersubjective processes by which any referent object is constituted as a legitimate claimant to security, is as central to the critical study and ethical practice of security, as that of putative threats to it.

Introduction

Debates about security largely centre on what constitutes a threat, and to whom. Indeed, it is the instability in both these categories that has provided the fodder for the advancement of security studies as a scholarly endeavour for at least the past three decades (Smith Citation1999; Buzan and Hansen Citation2009). This holds not least for a body of critical scholarship that has problematised security (and insecurity), as being product of plural human understandings and practices if not choices (Buzan Citation2008; Huysmans Citation1998; Leander Citation2005; Fierke Citation2007). This critical epistemological perspective abounds particularly as it relates to the study of security threats, with diverse writings positing as well challenging: the means by which threats (or risks) emerge or are constructed (Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde Citation1998; Balzacq Citation2011), the specific thresholds or characteristics that define those issues as threats (Huysmans Citation2004; Williams Citation2015), areas deemed of pertinence (Krause and Williams Citation1996; Duffield and Waddell Citation2006), and the agents made responsible for addressing them (Bigo Citation2002, Citation2006). This sustained analytical attention has by now crystallised into the relatively uncontroversial view that security threats are, at least to some extent, a matter of social construction.

Referent objects – the ‘for whom’ of security – have likewise been opened-up from their statist Cold War strictures, to become a category afforded much greater attention as well as contention. However, unlike in the case of threats, debates about referent objects have tended to circle around rationalist and normative arguments of what ‘is’ or ‘ought to be’ the appropriate referent object of security (Booth Citation1991; Krause and Williams Citation1997; McDonald Citation2016). Indeed, while the construction of threat framework has become so dominant as to be synonymous with the construction of security wholesale (McDonald Citation2008), arguably much less ink has been spilled unpacking the construction of referent objects, and how they come to be understood and reified as such.

This paper hopes to draw attention to this analytical lacuna, through an exploration of how ‘the individual’ is understood and considered within two predominant strands of critical security scholarshipFootnote1: Copenhagen School securitisation theory and human-centred security analysis. As I lay out, each approach holds a different interpretation of ‘the individual,’ based on incommensurate social ontological underpinnings. This ontological rigidity has stymied any fruitful dialogue between these two influential approaches, but more critically has also served unduly to limit each framework’s analytical, empirical, and even ethical purview, on its own terms. I then demonstrate the value of an alternative perspective, one that problematises rather than takes for granted ‘the individual,’ using an interpretive and historical lens.

The figure of ‘the individual’ is by no mean trivial to discussions of contemporary security theory and practice. However, the arguments made in relation to it also serve heuristically to illustrate the value of unpacking of any given referent object more generally. These arguments are not entirely new, with notable works taking the constituted nature of objects head-on in relation to societal (McSweeney Citation1999), state and national identity (Campbell Citation1992; Hopf Citation2002), and to regional if not global macro-objects (Buzan and Waever Citation2009). However, broader recognition, not to speak of a more systematic research agenda regarding the contingent nature of referent objects continues to be muted – even as the scope of (critical) security scholarship continues to expand (Salter Citation2019). In a relatively recent chapter on referent objects, for example, one of the foremost constructivists in security scholarship relegates the topic of their potentially constructed nature only to a brief footnote (McDonald Citation2016, 43).

Hence, beyond the referent object of ‘the individual,’ the paper hopes to make the case for a shift in emphasis in critical scholarship, if not away from the social constitution of security threats, then towards a fuller exploration of the constitution of security objects. That is, rather than taking security referents as static fixtures that are self-subsistent and ontologically prior to the study and practice of security, the paper highlights the need for critical analysis to more actively unpack the processes through which any referent object is or rather becomes constructed, legitimated, and reified as the privileged object of security. Giving those constitutive processes due attention reorients us from analysing practically endless articulations of possible dangers and risks, back to more fundamental and primal questions of political community (Walker Citation1997). By giving the contingent nature of security objects greater attention, I argue, we might arrive at a richer and more critical understanding of security writ large, as it appears in both theoretical or policy contexts. The paper concludes with a brief discussion of how this might look in relation to several referent objects beyond ‘the individual.’

Ships passing in the night? Two variations on security

Securitisation theory and human-centred security analysis have both made outsized contributions in challenging traditional understandings of security and have helped reshaped the landscape of the security studies field for a generation of analysts (Browning and McDonald Citation2011; Salter Citation2019). The two differ in profound ways, however. Securitisation theory, as the moniker denotes, is primarily a theoretical perspective that models how security problems are discursively construed and established. First laid out by Ole Waever in 1995, the theory was most fully expressed in Security: A New Framework for Analysis, co-authored by Barry Buzan, Ole Waever and Jaap de Wilde – the so-called Copenhagen School (CS) – in 1998 (Waever Citation1995; Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde Citation1998). The theory conceptualised security threats as an intersubjective construct that emerged through a specific process: a speech-act by a security agent construing an existential threat to a referent object, a demand for extra-ordinary measures to resolve it, and the acceptance of this argument by a relevant audience. This ‘parsimonious schematic’ provided the analytical means for scholars to empirically capture the emergence of a range of new security threats in the post-Cold War era.

Human-centred security, in contrast, has served less as a theoretical framework and more as a political project, a normative commitment, and scholarly ethos regarding ‘who’ is worth securing, namely, the individual or the human (Floyd Citation2007; Browning and McDonald Citation2011). Within scholarship, some of this was subsumed under the heading of Critical Security Studies (CSS) (Krause and Williams Citation1997; Booth Citation2005) as well as the so-called Aberystwyth school (Booth Citation1991; Wyn Jones Citation2005). In circles of policy and practice, it gained significant traction in the form of the concept of ‘human security.’ As laid out in the 1994 Human Development Report, it argued that ‘the world can never be at peace unless people have security in their daily lives,’ and outlined an aspiration of ‘freedom from want’ and ‘freedom from fear’ for individuals, encompassing seven dimensions of economic, health environmental, community, political and food security (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Citation1994, 3). This idea would subsequentially become influential among within important international bodies, particularly within the UN and its various agencies (UNGA Citation2012).

Both securitisation theory and human-centred security have of course been contested, modified, have been variably utilised in scholarship and practice over the years, in ways that make it inaccurate to portray them as each approach representing something entirely singular. For the purposes of this paper, I primarily use the CS version of securitisation theory or as it was conceived of by its original authors, due not least to the fact that the CS made very explicit claims regarding ‘the individual’ that have not since been directly refuted or rebutted in broader securitisation scholarship. Ownership of ‘human-centred security’ and its coherency as an endeavour is much less clear. I use the term to refer both to policy-oriented human security as well as schools of critical scholarship, that share the conviction that ‘the individual’ is the true or appropriate object of security analysis and practice. The intention is not to make light of important ideological or practical differences among them (see: Newman Citation2010). But I bracket out those out in favour of discussing what they – in principle – have in common.

That two relatively distinct approaches to security differ is not inherently problematic. No theory or framework can reasonably capture everything. The existence various schools of thought, each with their own normative or analytical foci and sub-debates also diversifies as well as enriches the broader field. However, the lack of any active intellectual cross-fertilisation between these two frameworks is still noteworthy.Footnote2 And as the below will detail, the gap is symptomatic of a much more fundamental issue, one which not only stymies greater dialogue between them, but also unduly limit the analytical and ethical purview of each approach on its own terms. In particular, the a priori ontological commitments that black box the referent object of ‘the individual,’ albeit in two very different ways.

In the next sub-section, I examine how the CS’s interpretation of ‘the individual’ is premised on a Hobbesian social ontology, and then turn to human-centred security analyses treatment of ‘the individual’ as what I refer as ‘the (universal) human,’ premised on the ontological claim of collective humanity. In both cases, ‘the individual’ tends to be treated as a given, as natural and self-evident, in ways that foreclose rather than invite greater critical reflection. Illuminating the disconnect between the two frameworks related ‘the individual’ will then serve as an entry point for discussing the need to problematise referent objects more generally.

From Hobbes to humanity: variations on ‘the individual’

One does not have to read too far into the lines to find analytical friction between the two approaches. In their 1998 publication, CS scholars made explicit that securitisation was not particularly compatible with other strands of Critical Security Studies (CSS).Footnote3 Among the primary differences, they noted, was that ‘much of CSS takes the individual as the true reference for security – human security – and thus in its individualism differs from our methodological collectivism and focus on collectivities’ (Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde Citation1998, 35). This gentle sidestepping was more harshly worded, when Buzan published an intervention characterising human-centred security as a ‘a reductionist, idealistic notion that adds little analytical value’ (Buzan Citation2004, 369). This was reiterated in a new 2008 introduction his classic People, States, and Fear, where Buzan wrote that one of the central positions of the CS has been the argument carried on from this earlier writing, that:

international security cannot and should not be reduced to individual security. Subsequent works [by the CS] have stuck with the idea that there is something important and distinctive about the security of human collectivities, whether states, nations, or some other kind. That position puts the CS at odds with some Peace Researchers, Critical Security Studies people, and normative political theorists who want to privilege the individual as the ultimate referent object of security (2008: 3)

In a 2009 article by Buzan and Waever, exploring different levels of securitisation, the authors wrote that they would ‘not attempt to address the space between the middle and individual levels in securitisation theory now occupied by the expanding literature on human security. That is a different topic.’ (emphasis added, 254). The CS, in other words, have firmly and consistently viewed human-centred security as incompatible with as well as outside of securitisation theory’s purview.

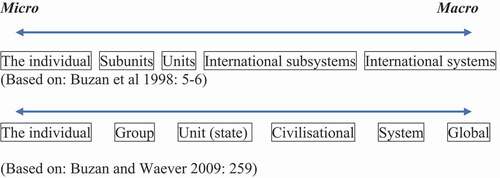

But this rather straightforward stance is underpinned by several assumptions that are worth some reflection. First, securitisation’s putative methodological collectivism is based on an implicitly realist social ontology, one that indeed renders ‘the individual’ a reductive object of little importance to international or collective security dynamics.Footnote4 This can be traced in CS reflections about their theory, particularly related to different levels of security. In specific, Buzan wrote that one of the CS theorists’ ‘original moves’ was to utilise a levels of analysis framework and combine it with sectors (Buzan Citation2008, 3). Both the use of sectors and of levels derived from his older writings and were considered by him to be a distinguishing feature of securitisation theory. Levels of analysis, relevantly here, meant the ‘idea of structuring theory in terms of spatial scale from individual through state to system’ (Buzan Citation2008, 3). These levels were discussed as ‘ontological’ spaces where referent objects were located, ranging from the micro to macro, with the individual located ‘on the micro-end of the spectrum’ (Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde Citation1998, 36).

There was some recognition by the CS that there were analytical perils of using this vertical schema (see , portrayed horizontally). Among those risks was that it could unwittingly reinforce ‘a specific ontology which obscures and discriminates,’ for instance by potentially privileging the state as the primary unit of the international system or fixing in place a fixed, hierarchical relationship between units at various levels (Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde Citation1998, 6–7).

However, Buzan would also wholeheartedly embrace those implications. As he expressed, levels of analysis (notably, a trade-tool which he derived from neorealist Kenneth Waltz’s writings) was perfectly in line with the social ontology held by the CS authors. ‘There have been three main CS positions based on levels [of analysis]’ over the years, he wrote. Of them, the first was the argument carried on from his People, States and Fear, ‘that international security cannot and should not be reduced to individual security’ (Buzan Citation2008, 3).

Explicated further, Buzan drew on 17th century philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ arguments, that though the individual was the ultimate irreducible unit of politics, it was a micro-level object that could never provide its own security in a state of nature. It was also the principal source of insecurity to other individuals or micro-units. The ever-prevalent threats that individuals posed to each other under conditions of anarchy, Buzan (Citation2008) wrote, were the fundamental conditions from which ‘government and the state are born’ (p. 51). The state, in turn, would necessarily be a structural source of insecurity for the individual. This Hobbesian contradiction, which he argued is ‘rooted in the nature of political collectives,’ was the reason given why higher levels of security could never be reduced to that of the individual (p. 60). Of relevance to the broader argument made this paper, such a conceptualisation was based on a fixed perspectives not only of ‘the individual,’ but also a broader social ontology that also fixed the relations between individuals, and their relationship to the state, in a very specific way. The point is not to hold Buzan or the CS’s feet to any fire on this issue. Buzan has in past decades stepped away from some of realist elements of his earlier writings. However, it is necessary to stress that it remains a firm ontological claim that underpins the CS scholars putative ‘methodological collectivism,’ and their position that ‘the individual’ is more or less irrelevant to broader-scale or international security dynamics.

However, the gap between the CS and human-centred security approaches is not in fact about methodological collectivism versus methodological individualism. The latter, for one, is an incorrect portrayal of what human-centred security offers. Methodological individualism is an explanatory framework that takes social phenomena as the result atomistic individual behaviour. Frankly, human-centred security is better characterised as methodologically collectivist, with social collectivities as the starting point of analysis. The starting point is merely a very specific ontology of the collective: namely, humanity.

To state what is perhaps already obvious, human-centred security proponents are simply not referring to the same thing as the CS when they speak of ‘the individual.’ When the latter refer to it, they are discussing a Hobbesian figure whose egoistic tendencies are inherently incompatible with security for others. But security for such an individual, one that holds no essential social bonds or regard for others, would hold little normative appeal, and is clearly not what is meant by human-centred security proponents. Instead, the object human-centred security proponents argue for is ‘the individual’ as a member of a broad-based human collective. A quick perusal of the 1994 UNDP Human Development Report also suggests that it is only as part of that grouping that the individual as an appropriate object of security makes any sense. The report text references ‘individual’ 36 times, ‘universal’ 23 times, and ‘humanity’ 19 times. At various points, it bases its moral premise of human security on the ‘universality of life claims,’ drawing upon the language of human rights and ‘the inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family’ (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Citation1994; UN General Assembly (UNGA) Citation1948).

‘The individual’ of CS theorisation may be on the lowest end of their micro- to macro- levels spectrum. But ‘the individual’ of human-centred security would not be so easily placed along such a linear hierarchy. Its relationality is much more circular and recursive, best captured in the oft-quoted Abrahamic precept that, ‘whosoever saveth the life of one, it shall be as if he had saved the life of all mankind’ (The Qur’an, Citation1938, 5:32; see also Yerushalmi Talmud, 4:9). The macro- is embedded within the micro-, and the micro- embedded within the macro, in an inclusive and ‘indivisible’ universalism that ‘cannot be pursued by or for one … at the expense of another’ (Thomas Citation2001, 161). To suggest any other version of individuality, as Booth (Citation1999, 41) has written, would be ‘psychotic.’

But if human-centred security is not methodologically individualist or reductive, how do we explain the CS’s misconception? For this, we might turn to the words of Emile Durkheim, the poster child of methodological collectivism and a scholar whom the CS have ironically been accused of being disciplines of (see: McSweeney Citation1998). Durkheim, however, was also an unabashed proponent of individualism, even a devotee of what he called the ‘cult of the individual.’ This, however, was individualism in a form similar to that of human-centred security proponents. Writing in opposition to 19th century utilitarianism, he stated:

a verbal similarity has made it possible to believe that individualism necessarily resulted from individual, and thus egoistic sentiments … in reality [the individual] receives this dignity from a higher source, one which he shares with all men … it is because he has in him something of humanity. It is humanity that is sacred and worthy of respect. And this is not his exclusive possession. The cult of which he is at once both object and follower does not address itself to the particular being that constitutes himself and carries his name, but to the human person, wherever it is to be found, and in whatever form it is incarnated … in short, individualism thus understood is the glorification not of the self, but of the individual in general (emphasis added, transl. Lukes Citation1969, 23-28).

He went on to argue that such individualism was ‘a social institution’ that was not only ‘distinct from anarchy; but it is henceforth the only system of beliefs which can ensure the moral unity of the country’ (p. 28). Revising his words in light of the present argument: a verbal similarity has made it possible to believe that ‘the (universal) human’ as referent object, has meant the atomised, asocial individual as explanans.

Constituting ‘the individual’: an interpretive and historical perspective

But if neither CS securitisation theory nor human-centred security can be deemed methodological individualist, then analytical gap between them stems from elsewhere. Here, I start my argument that it is the very epistemological and interpretive closure of ‘the individual’ that has led to this impasse. And that even if lack of dialogue between the two approaches is not itself problematic, broader insensitivity to the epistemic if not ontological contingency of ‘the individual’ rather is. To demonstrate, this section first re-considers ‘the individual’ not as ontologically fixed, but as signifier that has variable interpretations within different theoretical or practical understandings of security. I then use a more historical lens to empirically problematise and deconstruct it. Depending on one’s epistemological bent, this can be done as an analytic exercise (one that temporarily sets aside the question of whether one interpretation or another more accurately corresponds to a pre-given reality), or as a part of a more critical constructivist argument (that ‘the individual’ is only given meaning and positionality through our understandings of it). Even in the former case, the exercise draws attention to the analytical and even ethical consequences of taking any one interpretation of ‘the individual’ for granted, and hence the value of such an approach for critical scholarship.

To start, we might consider what sorts of interpretations of ‘the individual’ exist in security analysis. interpretations that necessarily include not only the individual itself but also the wider social ontology or relational system in which it is embedded. Below, I draw out a just few forms that are rather prosaic to security analysis (see: ). These are certainly not exhaustive, nor mutually exclusive. As illustrative typologies, it is not so much the verbatim terminology of interest, but again the underlying conceptualisation which is.

The individual as an atomised, asocial form of ‘bare life,’ to use Agamben’s (Citation1998) term,Footnote5 comes close to the figure to whom the CS are referring. This individual, who exists locked in an anarchic state of nature where ‘every man [sic] is enemy to every man [sic]’ (Hobbes [1651] Citation2002, 95) is, as mentioned, the irreducible unit of most realist and neorealist political analysis. Embedded in this anarchy, its securityFootnote6 may indeed constitute a direct threat to other individuals, whose wellbeing and survival it has no vested interest in. The individual interpreted as a citizen or state subject, however, draws upon a different set of social relations. That individual is politically subsidiary to the state in which it resides. Its security is co-terminus with that state, and its fate is tied up with a broader community of citizen-subjects. However, that community is by definition politically exclusionary. Strictly so circumscribed, the security of an individual might be compatibly ensured at the expense of the security of non-citizens, or citizen-subjects of other states to whom no social bonds need exist (Krause and Williams Citation1997, 43). But the individual as ‘the (universal) human’ draws on a yet another ontology. This is one in which relations between all individuals are embedded in humanity, a relationship which extends across all units and operates universally, to transcend or supersede any other lower- ‘level’ political, cultural, ethnic, social division.

This breakdown is by no means to suggest that corporeal persons in fact fall into to any of the three categories: neither that persons are or are not part of a pre-given human collectivity, nor that they do or do not hold an essentially violent, egotistical nature outside of mediating social institutions. But at minimum, the variability points to a need to be explicit (and empirically inquisitive), about what is meant by ‘the individual’ as referent, and the broader ontologies upon which any account of it is based, when making theoretical or ethical claims about said object – if only to help make subsequent debates more lucid.

That being said, there are clear ways to further problematise narratives that essentialise ‘the individual’ as actually being in one or the other column. As it relates to ‘the individual’ of the first column, Williams (Citation1996, drawing on Johnston Citation1986) provided a brilliant discussion of how Hobbes’ arguments about the asocial individual in a ‘state of nature,’ was never intended as an empirical or even ontological claim, but as a means of ‘convinc[ing] people’ to accept a particular political order, and to ‘create [public] understanding, acceptance, and support’ for a strong sovereign state (p. 220). Hobbes made a legitimating ‘move,’ if you will (and a rather successful one apparently) utilising a rhetorical construct rather than referencing an actual extant object. Certainly, as far as positivist arguments go, one would be hard pressed to find a biologist or anthropologist to empirically validate such claims.

As it relates to ‘the (universal) human,’ a dose of scepticism is helpfully facilitated by the fact this figure is characterised by its own proponents as a being in abstracto (Lukes Citation1969, 21, and a figure which to use Hannah Arendt’s words, ‘seem[s] to exist nowhere’ (Arendt Citation1973, 291). Like the Hobbesian individual – to the extent that one might refer to that construct as empirical – it is not timeless, but historical. Moreover, it has not even always been universal.Footnote7 Until recently, even rhetorical formulations of ‘humanity’ were fundamentally exclusionary. In the West, John’s Locke’s 17th century theory of natural rights, one of the ‘first fully developed natural rights theory fundamentally consistent with later human rights ideas,’ never extended beyond propertied European males (Donnelly Citation2011, 15). Both the 1776 US Declaration of the Independence (with ‘self-evident’ truths that ‘all men [sic] are created equal’) and 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (as ‘natural, unalienable and sacred’) were never designed to extend full equality, and even membership, to all people even within their national territorial boundaries – much less outside of it (Arendt Citation1973).

Thus, the extension of rights, including the right to security suggests much longer, slower processes of legitimation and institutionalisation (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966). For example, as Emma Rothschild (Citation1995) writes:

One of the preoccupations of liberal thought in the late Enlightenment was with the extension of rights to individual security, or rights of humanity, to individuals who were not citizens of the state in which the rights were being asserted: to women, to children, and to the propertyless … The next stage, in this extension of rights, or at least of the right to protection, was its further enlargement to individuals outside the state or political territory.

What or who is (or is not) is recognised as ‘human’ or as a common member of ‘humanity’ with ‘unalienable,’ ‘self-evident,’ ‘inherent,’ or ‘natural’ rights’ – including to security – has thus been the subject of long, difficult, and ongoing social struggles across myriad settings. This process has been and remains uneven and by no means unidirectional, a topic regarding which feminist and post-colonial scholars would have much more to say (Said Citation1978; Wynter Citation2003; Butler Citation2004; MacKinnon Citation2007).

And while some liberal thinkers have sought to portray this as a teleological, naturally unfolding (or extra-social process), such passive or political inactive understandings of how individual rights are secured can arguably do more damage to the cause. Here we might again draw on Hannah Arendt, who on behalf of stateless refugees and those without any political recourse, and was deeply critical of those who took ‘universality’ for granted, and was dismissive of its conceptual basis in

some inborn human dignity which de facto, aside from its guarantee by fellow men [sic], not only does not exist but is the last and most arrogant myth we have invented in all our long history (Arendt Citation1973, 298).

Hence, whether as part of an argument for the necessity of the sovereign state, or as part of a pursuit of an ideal world, both interpretations of ‘the individual’ might be better recognised for what they are: products of ongoing social efforts that are embedded in rather than ontologically prior to, how security is both studied and practiced.

Analytical fruits and opening up security perspectives

Why does this matter, and what consequences does it have for scholarship? To start with the low-hanging fruit, one of the consequences of a more open perspective on ‘the individual,’ is a means of reconciling the two security approaches. Securitisation theory (at least as originally envisaged by the CS) has so far been marked by an inability and even unwillingness to engage with security frameworks in which the individual serves as the primary security referent. But instead of prematurely cutting off dialogue in the name of putative methodological collectivism, securitisation theory might for instance analytically engage with human-centred security as an empirical phenomenon, as for example a socio-discursive movement (or series of moves) to construct, objectify, and legitimate a particular security object (Newman Citation2001; McDonald Citation2002; Gasper Citation2005; Watson Citation2011).

One could still argue that the above makes little difference, as the main analytic contribution and interest of the CS’s securitisation theory was never to problematise referent objects in the first place, but rather security threats. Indeed, the fixity on referent objects, at the heart of an otherwise constructivist and anti-essentialist security theory, was a controversy partially by Bill McSweeney (Citation1998) over two decades ago. He took up arms against their treatment of ‘societal identity’ as a pre-given security object, and their side-stepping of the processes by which it subject to change. The CS response was to stress that their choice was deliberate: they argued that their more-or-less objectivist position on societal identity and social relations had the advantage, ‘totally in line with classical security studies,’ of helping to better manage relations among units of analysis, to better problematise ‘security’ as such (Buzan, Waever, and de Wilde Citation1998, 204–206; Waever Citation2011).

This sort of so-called ‘ontological gerrymandering,’ of opening certain boxes for analysis while holding others constant is not unique to the CS, and is, as pointed out by Woolgar and Pawluch (Citation1985), a rather inescapable tendency in constructivist accounts more generally (Huysmans Citation1998). Analytical accounts focused on the intersubjective nature of threats or narrower securitisation models, may indeed find it much more useful to open only one black box at a time, and fix or take as given (or sedimented enough) other security constructs and relationalities, including the referent object, in the name of theoretical parsimony.

But while this certainly seemed to be the case in the CS’s earlier securitisation work, Buzan and Waever have opened up their framework on referent objects quite significantly. In a 2009 article, Buzan and Waever detailed what they referred to as ‘macro-level’ securitisations, which depend on ‘the construction of higher-level referent objects capable of appealing to and mobilising, the identity politics of a range of actors within the system. (268). They suggested that these macro-securitisations are often deployed through universalist ideologies and formulations that help ‘create’ macro-level social structures and structure relations in more large-scale ways than ‘suggested by a mere logic of individual unit survival’ (Buzan and Waever Citation2009, 268–275). Based on the CS’s own theorisation, then, human-centred security might be considered as part of a universalist ideology that facilitates securitisations at the ‘macro-level. If so, the constitution and construction of ‘the (universal) human’ is consistent and compatible with CS theory itself, one that could be analysed empirically in terms of a move (or movement) with influence on global security dynamics – for example, as Watson (Citation2011) gracefully does in relation to humanitarianism. Hence, the doubling down in that same article on the individual as a micro-level, and as being a ‘different topic,’ is unnecessarily limiting (Buzan and Waever Citation2009, 254).

For human-centred security, on the other hand, as a move (or movement) to actively transform policy practice, its proponents and practitioners may also benefit from a deeper look at the sort of world-building enterprise in which they are engaged. Indeed, as such an explicit political endeavour to legitimate and institutionalise if not produce a particular referent object, human-centred security is doubly tasked with normative, ethical and analytical reflexivity. To date, however, its pursuit of security for an objectified ‘(universal) human’, however, has tended to re-produce security dynamics subject to substantial critique from critical quarters (Duffield and Waddell Citation2006; Grayson Citation2008; Chandler Citation2008; De Larrinaga and Doucet Citation2008; McCormack Citation2008; Chandler and Hynek Citation2011). Its referent ‘individual’ is as Shani (Citation2011) argues, ‘de-historicized and deracinated’ in ways that tend to strip persons of the dignity of difference and serves the interests of traditional powerbrokers. And while human-centred security proponents are often careful to being avoid being charged with essentialism, this is often done in an uneven manner. Booth (Citation2005, 268) for instance describes the need to ‘denaturalize and historicize all human-made political referents, recognizing only the primordial entity of the socially embedded individual’ (emphasis added).

But political theorists as diverse as Carl Schmitt and Hannah Arendt (as mentioned) have also argued that presumptions and invocations of humanity that override the political-processual struggle to actively include, can damage the cause. Foreshadowing the extensive body of critique against human security many decades later, Schmitt (Citation1987) recounted how actions in the name of humanity and humanitarianism can mask ‘the possibility of the deepest inequality’ (see also Schmitt 2007 [Citation1932]). In this regard, while the anti-essentialism that so marks securitisation – at least in terms of threats – may not initially seem compatible with ethos and convictions of human-centred security, greater engagement with critical frameworks might give what is due pause for greater analytical, political, and ethical reflection, and serve as a check on its more totalising epistemological tendencies.

Constituting referent objects beyond ‘the individual’

This paper has rather singularly focused on ‘the individual,’ as analytic object that features prominently in security theory and practice. But the analysis and argument made here can also extend to a broader range of security objects beyond it. What the previous section has attempted to demonstrate, is that variability in interpretations of what a referent objects ‘is’ has significant implications for theory and for practice. As well, that even when interpretations may agree, what is to be secured is never ontologically self-evident nor self-subsistent. Rather, it becomes so as part of ongoing social processes of legitimation if not social production. Such processes are never foregone or fully finished – as evident in the ongoing debates about who or what is or ought to be the appropriate security referent. Such points are by now relatively trivial as it relates to the analysis of security threats. But they are arguably less systematically reflected upon for security objects, at least in contemporary critical security scholarship. There are, however, a number of illustrations of such analysis, including in the broader field of IR, where for example the ‘identities’ of states, nations, and other collectivities have been analysed and problematised as the products of ongoing social and discursive re-production (Campbell Citation1992; Milliken Citation1999; Hansen Citation2006; Wilhelmsen Citation2017; Hutchinson Citation2017). Weldes et al. (Citation1998, 10) has also suggested that

One way to get at the constructed nature of insecurities is to examine the fundamental way in which insecurities and the objects that suffer from insecurity are mutually constituted; that is, in contrast to the received view, which treats the objects of insecurity and insecurities themselves as pregiven or natural, and as ontologically separate things … insecurity is itself the product of processes of identity construction in which the self and other, or multiple others, are constituted.

However, outside of these notable works, these reflections do not seem to have congealed into a broader and more systemic research agenda within critical security scholarship.

Notably, in some attempt to avoid trading one fixity for another, this paper has not offered any strict theoretical or methodological schematic for studying the constitution of particular security objects. Contingent and contextual, such process are inherently messy, and will always require a degree of inductive investigation. But whether from an interpretive, historical, or sociological lens, a more empirically. epistemically, if not ontologically open account of referent objects might start with questions such as: what precisely is meant by any given security object, and upon what social ontological assumptions is it based? By what social processes does it come to be seen as a legitimate (or illegitimate) referent of security? By what means does it become a more durable, even institutionalised, referent? What broader relationalities does such a referent either perpetuate, displace, or transform, and with what consequences? These questions need not come at the hard expense of any one theoretical approach over another, nor do they imply endless deconstruction ad infinitum (Mustapha Citation2013). But they do draw overdue attention to the constitution of security referents, as a matter this paper has argued is fundamental to the critical study of security and to the ethical practice of it.

Asking how ‘who’ or what is deemed worthy of being secured comes be to a social fact among one social grouping or another, might read as a tired exercise when applied to security objects that have undergone decades if not centuries of legitimation – including the state – and which has already been scrutinised by many critical IR scholars. But such questions might be well-asked to security objects are emerging but yet not fixed or institutionalised, for instance, in relation to the environment, climate, biosphere, as well as the non-/post-human (Mitchell Citation2014; Burke et al. Citation2016; Dalby Citation2017). Moving directly beyond ‘the individual,’ the ‘post-human’ for example remains an evolving and contested concept, involving interpretations that can even be incompatible (Wolfe Citation2010), from entanglements of ‘all life, non-life, and technology’ worthy of care (Harrington Citation2017, 74), to biotechnological innovations that more binarily threaten what it means to be ‘human’ (Fukuyama Citation2002). Likewise, in emergent calls for the ecological system or the biosphere to be secured, it is by no means self-evident what precisely that ‘is,’ when distinctions between the natural and built environment are blurring, and both are already undergoing rapid, irreversible transformation (McDonald Citation2021). Deep reflections about these boundary-drawing problems are ongoing in various fields, from science and technology studies (STS) to critical geography; such insights would be valuable to bring into critical security scholarship as well.

This matters because, in both academic and policy contexts, much rides on which specific meanings and interpretations prevail, and what any ‘given’ security object inevitably excludes as well as ludes. The social processes of defining, legitimating, reifying and institutionalising a privileged referent of our efforts should form an important pillar of critical scholarship, especially to the extent that critical scholarship seeks to understand, challenge, and shape them. Such attention, moreover, need not come at the expense of buying into one or another position on what or who ‘should’ or ‘should not’ be secured. Studying how security objects are constituted, as well as their productive political effects, can serve reflectively to give us a more reasonable sense of our own limits and possibilities. In particular, when making decisive claims for or against one object or another as worth securing, we might begin to accept that the ‘for whom’ question of security is indeed not one that can be answered on objective or technical grounds – it is contingent and inescapably value-based. This means that any conclusion to questions of ‘who’ or ‘what’ might always be otherwise, and hence must be continually (re-)negotiated, justified and fought for in political terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jiayi Zhou

Jiayi Zhou is a Researcher at SIPRI, working at the intersection of geopolitics and sustainable development, with a topical focus on food security and regional focus on Russia and China. She is also PhD candidate at Linköping University.

Notes

1. This category is fluid, but for an overview of how it is delineated here, see: C.A.S.E. Collective (Citation2016)and Browning and McDonald (Citation2011).

2. In one exception, Alker (Citation2005) suggested that the anti-essentialism of securitisation theory might be ‘cautiously linked’ to emancipatory practices on behalf of individuals – but whether this has been done is a separate question. While Watson (Citation2011) has convincingly used securitisation theory to argue for humanitarianism as a sector of security and the human as a referent object, he did not engage with any of the CS’s rather explicit claims to the contrary.

3. See note 1.

4. Notably, the Hobbesian foundations of securitisation theory have also been addressed by Howell and Richter-Montpetit (Citation2020). However, the analysis here is less interested in phrasing related to ‘state of nature’ or ‘primal anarchy’ per se, but rather Buzan’s explicit discussion of the Hobbesian nature of the relationship between ‘the individual’ and the collective / state, and his claim that this informs securitisation theory’s approach to individual-centred security, as demonstrated quotes. In Waever and Buzan (Citation2020)’s rebuttal to Howell and Richter-Montpetit (Citation2020), the CS also continue to follow a prosaic ‘distinction between anarchy at the level of individuals (Hobbesian, primary) and at the level of political collectivities.’ (p. 391–392).

5. Of course, Agamben used the term not so much to describe the individual in the Hobbesian state of nature, but to suggest a particular relationship with a sovereign in which an individual was fully deprived of rights and reduced to bare biology.

6. Or freedom (see: Waltz 2010 [Citation1979], 112).

7. While the idea of common humanity is today prosaic in policy – its uptake in practice is still incredibly uneven. Donnelly (Citation2007) makes a useful distinction between conceptual and substantive universality.

References

- Agamben, G., Heller-Roazen, D. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Transl. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Alker, H. 2005. “Emancipation in the Critical Security Studies Project.” In Critical Security Studies and World Politics, edited by K. Booth. Boulder: Lynne Rienner pp. 189–213 .

- Arendt, H. 1973. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Orlando: Harcourt: Inc.

- Balzacq, T., ed. 2011. Securitisation Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve. New York: Routledge.

- Berger, P. B., and T. Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality. London: Penguin Group.

- Bigo, D. 2002. “Security and Immigration: Toward a Critique of the Governmentality of Unease.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 27 (1): 63–92. doi:10.1177/03043754020270S105.

- Bigo, D. 2006. “Globalized (In)security: The Field and the Ban-opticon.” In Illiberal Practices in Liberal Regimes, edited by D. Bigo and A. Tsoukala, 5–49. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Booth, K., ed. 2005. Critical Security Studies and World Politics. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Booth, K. 1991. “Security and Emancipation.” Review of International Studies 17 (4): 313–326. doi:10.1017/S0260210500112033.

- Booth, K. 1999. “Three Tyrannies.” In Human Rights in Global Politics, edited by N. J. Wheeler, and T. Dunne. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 31-70 .

- Browning, C. S., and M. McDonald. 2011. “The Future of Critical Security Studies: Ethics and the Politics of Security.” European Journal of International Relations 19 (2): 235–255. doi:10.1177/1354066111419538.

- Burke, A., S. Fishel, A. Mitchell, S. Dalby, and D. J. Levine. 2016. “Planet Politics: A Manifesto from the End of IR.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies Perspectives 44 (3): 499–523.

- Butler, J. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso.

- Buzan, B., and L. Hansen. 2009. The Evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Buzan, B., and O. Waever. 2009. “Macrosecuritisation and Security Constellations: Reconsidering Scale in Securitisation Theory.” Review of International Studies 35 (2): 253–276. doi:10.1017/S0260210509008511.

- Buzan, B., O. Waever, and J. de Wilde. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Buzan, B. 2004. “A Reductionist, Idealistic Notion That Adds Little Analytical Value.” Security Dialogue 35 (3): 369–370. doi:10.1177/096701060403500326.

- Buzan, B. 2008. Peoples, States, and Fear. Second ed ed. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- C. A. S. E. Collective. 2016. “Critical Approaches to Security in Europe: A Networked Manifesto.” Security Dialogue 37 (4): 443–487.10.1177/0967010606073085.

- Campbell, D. 1992. Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Chandler, D., and N. Hynek. 2011. Critical Perspectives on Human Security: Rethinking Emancipation and Power. London: Routledge.

- Chandler, D. 2008. “Human Security: The Dog That Didn’t Bark.” Security Dialogue 39 (4): 427–438. doi:10.1177/0967010608094037.

- Dalby, S.,2017.“Global Ecology, Social Nature, and Governance.”In Global Insecurity, edited by A. Burke, and R. Parker, London:Palgrave Macmillan 103–118

- De Larrinaga, M., and M. G. Doucet. 2008. “Sovereign Power and the Biopolitics of Human Security.” Security Dialogue 39 (5): 517–537. doi:10.1177/0967010608096148.

- Donnelly, J. 2007. “The Relative Universality of Human Rights.” Human Rights Quarterly 29 (2): 281–306. doi:10.1353/hrq.2007.0016.

- Donnelly, J. 2011. “The Social Construction of International Human Rights.” Relaciones Internacionales 17: 1–30.

- Duffield, M., and N. Waddell. 2006. “Securing Humans in a Dangerous World.” International Politics 43 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800129.

- Fierke, K. 2007. Critical Approaches to International Security. Cambridge: Polity.

- Floyd, R. 2007. “Human Security and the Copenhagen School’s Securitisation Approach: Conceptualizing Human Security as a Securitizing Move.” Human Security Journal 5: 38–49.

- Fukuyama, F. 2002. Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. New York: Picador.

- Gasper, D. 2005. “Securing Humanity: Situating ‘Human Security’ as Concept and Discourse.” Journal of Human Development 6 (2): 221–245. doi:10.1080/14649880500120558.

- Grayson, K. 2008. “Human Security as Power/knowledge: The Biopolitics of a Definitional Debate.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 21 (3): 383–401. doi:10.1080/09557570802253625.

- Hansen, L. 2006. Security as Practice: Discourse Analysis and the Bosnian War. New York: Routledge.

- Harrington, C. 2017. “‘Posthuman Security and Care in the Anthropocene.’.” In Reflections on the Posthuman in International Relations, edited by C. Eroukhmanoff, and M. Harker. Bristol: E-IR Publishing 73–86 .

- Hobbes, T. 2002. Leviathan. [1651], Ontario: Broadview Press.

- Hopf, T. 2002. Social Construction of International Politics: Identities and Foreign Policies, Moscow, 1995 and 1999. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- Howell, A., and M. Richter-Montpetit. 2020. “Is Securitization Theory Racist? Civilizationism, Methodological Whiteness, and Antiblack Thought in the Copenhagen School.” Security Dialogue 51 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1177/0967010619862921.

- Hutchinson, J. 2017. Nationalism and War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Huysmans, J. 1998. “Security! What Do You Mean? From Concept to Thick Signifier.” European Journal of International Relations 4 (2): 226–255. doi:10.1177/1354066198004002004.

- Huysmans, J. 2004. “Minding Exceptions: Politics of Insecurity and Liberal Democracy.” Contemporary Political Theory 3 (3): 321–341. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cpt.9300137.

- Johnston, D. 1986. The Rhetoric of Leviathan: Thomas Hobbes and the Politics of Cultural Transformation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Krause, K., and M. C. Williams. 1996. “Broadening the Agenda of Security Studies: Politics and Methods.” Mershon International Studies Review 40 (2): 229–254. doi:10.2307/222776.

- Krause, K., and M. C. Williams, ed. 1997. Critical Security Studies: Concepts and Cases. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Leander, A. 2005. “The Power to Construct International Security: On the Significance of Private Military Companies.” Millenium: Journal of International Studies 33 (3): 803–826. doi:10.1177/03058298050330030601.

- Lukes, S. 1969. “‘Durkheim’s ‘Individualism and the Intellectuals’.” Political Studies 17 (1): 14–30. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1969.tb00622.x.

- MacKinnon, C. A. 2007. Are Women Human?: And Other International Dialogues. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University.

- The Qur’an. transl. by Pickethall, Marmaduke, M. “Hyderabad-Deccan.” Government Central Press, 1938.

- McCormack, T. 2008. “Power and Agency in the Human Security Framework.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 21 (1): 113–128. doi:10.1080/09557570701828618.

- McDonald, M. 2002. “Human Security and the Construction of Security.” Global Society 16 (3): 377–296. doi:10.1080/09537320220148076.

- McDonald, M. 2008. “Securitization and the Construction of Security.” European Journal of International Relations 14 (4): 563–587. doi:10.1177/1354066108097553.

- McDonald, M. 2021. Ecological Security: Climate Change and the Construction of Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McDonald, M. 2016. “Whose Security? Ethics and the Referent.” In Ethical Security Studies: A New Research Agenda, edited by J. Nyman, and A. Burke. London: Routledge pp. 32-45 .

- McSweeney, B. 1998. “Durkheim and the Copenhagen School: A Response to Buzan and Wæver.” Review of International Studies 24 (1): 137–140. doi:10.1017/S0260210598001375.

- McSweeney, B. 1999. Security, Identity and Interests: A Sociology of International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Milliken, J. 1999. “Intervention and Identity: Reconstructing the West in Korea.” In Cultures of Insecurity: States, Communities, and the Production of Danger, edited by J. Weldes, M. Laffey, H. Gusterson, and R. Duvall. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press pp. 91-118 .

- Mitchell, A. 2014. “Only Human? A Worldly Approach to Security.” Security Dialogue 45 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1177/0967010613515015.

- Mustapha, J. 2013. “Ontological Theorizations in Critical Security Studies: Making the Case for a (Modified) Post-structuralist Approach.” Critical Studies on Security 1 (1): 64–82. doi:10.1080/21624887.2013.790193.

- Newman, E. 2001. “Human Security and Constructivism.” International Studies Perspectives 2 (3): 239–251. doi:10.1111/1528-3577.00055.

- Newman, E. 2010. “Critical Human Security Studies.” Review of International Studies 36, No 1 (1): 77–94. doi:10.1017/S0260210509990519.

- Rothschild, E. 1995. “What Is Security?” Daedalus 124 (3): 53–98.

- Said, E. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Random House.

- Salter, M. 2019. “Reflecting on Security Dialogue at 50.” Security Dialogue 50 (4): 3–8. doi:10.1177/0967010619862915.

- Schmitt, C. 1987. “The Legal World Revolution.” Telos 72 (72): 73–89. doi:10.3817/0687072073.

- Schmitt, C. 2007 [1932]. The Concept of the Political. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Shani, G. 2011. “Securitizing ‘Bare Life’.” In Critical Perspectives on Human Security: Rethinking Emancipation and Power, edited by D. Chandler, and N. Hynek. New York: Routledge 56–68 .

- Smith, S. 1999. “The Increasing Insecurity of Security Studies: Conceptualizing Security in the Last Twenty Years.” Contemporary Security Policy 20 (3): 72–101. doi:10.1080/13523269908404231.

- Thomas, C. 2001. “Global Governance, Development and Human Security: Exploring the Links.” Third World Quarterly 22 (2): 159–175. doi:10.1080/01436590120037018.

- UN General Assembly (UNGA). 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights.’ UN, 217 (III) A

- UNGA. 2012. “Follow-up to General Assembly Resolution 64/291 on Human Security: Report of the Secretary-General.” A/RES/66/763.’ 5 April.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 1994. Human Development Report. New York: United Nations.

- Waever, O., and B. Buzan. 2020. “Racism and Responsibility – The Critical Limits of Deepfake Methodology in Security Studies: A Reply to Howell and Richter-Montpetit.” Security Dialogue 51 (4): 386–394. doi:10.1177/0967010620916153.

- Waever, O. 2011. “Politics, Security, Theory.” Security Dialogue 42 (4–5): 465–480. doi:10.1177/0967010611418718.

- Waever, O. 1995. “Securitisation and Desecuritisation.’.” In On Security, edited by R. D. Lipschutz. New York: Columbia University Press pp. 46-87 .

- Walker, R. B. J. 1997. “The Subject of Security.” In Critical Security Studies: Concepts and Cases, edited by K. Krause and M. C. Williams. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 61-81.

- Waltz, K. 2010 [1979]. Theory of International Politics. Long Grove: Waveland Press.

- Watson, S. 2011. “The ‘Human’ as Referent Object? Humanitarianism as Securitisation.” Security Dialogue 42 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1177/0967010610393549.

- Weldes, J., M. Laffey, H. Gusterson, and R. Duvall, eds. 1998. Constructing Insecurity. Cultures of Insecurity: States, Communities, and the Production of Danger. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Wilhelmsen, J. 2017. Russia’s Securitisation of Chechnya: How War Became Acceptable. London: Routledge.

- Williams, M. C. 1996. “Hobbes and International Relations: A Reconsideration.” International Organization 50 (2): 213–236. doi:10.1017/S002081830002854X.

- Williams, M. C. 2015. “Securitization as Political Theory: The Politics of the Extraordinary.” International Relations 29 (1): 114–120. doi:10.1177/0047117814526606c.

- Wolfe, C. 2010. What Is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Woolgar, S., and D. Pawluch. 1985. “Ontological Gerrymandering: The Anatomy of Social Problems Explanations.” Social Problems 32 (3): 214–227. doi:10.2307/800680.

- Wyn Jones, R. 2005. “On Emancipation: Necessity, Capacity and Concrete Utopias.” In Critical Security Studies and World Politics, edited by K. Booth, 215–235. London: Lynne Rienner.

- Wynter, S. 2003. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation–an Argument.” CR: The New Centennial Review 3 (3): 257–337. doi:10.1353/ncr.2004.0015.