ABSTRACT

This article contributes to our understanding of security devices by engaging with the distinctiveness of one particular and especially important device: the smartphone. Drawing from Barad’s understanding of posthumanist performativity and turning to the smartphone literature outside of security studies, it develops a conceptual account of the smartphone as a security device. The article suggests that the smartphone stands out from other comparable devices because humans have come to embody its connective features. Using the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 as an illustration, the article shows how the smartphone’s intra-action with users enable the crafting of new security practices through appropriations of embodied connectivity, especially when such appropriations are carried out on the streets. The police appropriated the smartphone to monitor social media activity and for geofencing, while the protesters appropriated it to obfuscate data and for livestreaming. By (re)locating the negotiation of competing security interests in the (extended) bodies of the protesters through the affordance of these practices, the smartphone contributed to the acceleration and intensification of a racialised spiral of surveillance and counter-surveillance.

Introduction

After the 3 G- and 4 G revolutions from 2007 and onwards, smartphone technology has spread quickly and become a ubiquitous and fully naturalised part of everyday life (Ling et al. Citation2020, 3–4). An advancement from the perpetual contact provided by mobile phones, the smartphone offers ‘truly constant, mobile connection’ and thus the ‘permanently possible use of mass media’ (Vordener and Klimmt Citation2020, 55). Moreover, the smartphone’s size, easy operability and portability makes it stand out from other comparable devices – such as tablets, laptops and smart watches – by enabling more intimate connection with the human body (Taipale, Tuuli, and van Aerschot Citation2020, 657–658; Mazmanian Citation2019, 127; Chambers Citation2016, 198–200).

This article contributes to literature on security devices (Amicelle, Aradau, and Jeandesboz Citation2015) by examining how the smartphone operates as a distinct security device. This is important considering the smartphone’s towering cultural influence and permeation of everyday life, but also its increasing centrality to both state and corporate surveillance. A defining object of our time (Eriksen in Engblad Citation2021) and an essential tool for intelligence gathering in the digital age (Chambers Citation2016), this particular device surely warrants attention in studies of politics and security.

To that end, the article develops a conceptual account of the smartphone as a security device. In doing so, it mobilises Barad’s (Citation2003) understanding of posthumanist performativity to make sense of how security devices such as the smartphone produce security through the ways in which they intra-act with human security actors. Moreover, it turns to the smartphone literature outside of security studies to delineate the smartphone as a distinct security device and unpack how the device is performative of security through the specific ways in which it is appropriated for security purposes. Security-appropriation of devices happens when devices that are not originally made for security purposes are taken over by security actors and repurposed for security (Amicelle, Aradau, and Jeandesboz Citation2015, 300–302). Through appropriation-processes, moreover, commercial devices such as the smartphone can contribute to drawing ‘boundaries and lines of exclusion’ based on gender, class, and race (298). By providing connective features that are originally made for communication- and entertainment purposes, the smartphone specifically does so by enabling the production of security practices that mobilise the intimate, everyday connection between user and device.

To illustrate how the smartphone operates as a security device, the article turns to the protest setting, and in particular the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the summer of 2020. Here, the smartphone was appropriated by both police and protesters. The police monitored smartphone activity via social media posts and geolocation history (Biddle Citation2020a; Faife Citation2022), while protesters obfuscated smartphone data to make it more difficult for the police to intensify surveillance, and documented events via livestreams to hold the police accountable (Boyd et al., Citation2021; Bailey 2020). Enabling moves and countermoves, the smartphone thus contributed to constituting security in this context as a spiral of racialised surveillance and counter-surveillance (Ullrich and Knopp Citation2018; Wilson and Serisier Citation2010; Browne Citation2015). Moreover, by appropriating embodied connectivity, these practices (re)located the negotiation of competing security interests in the (extended) bodies of the protesters.

The article proceeds in two main parts. First it conceptualises the smartphone as a security device, and second, it illustrates the conceptualisation with the protest setting and more specifically the BLM protests. The article’s contribution is primarily conceptual but will also add to our knowledge about protest movements and racialised surveillance as security practices. Since the article’s empirical analysis is illustrative, moreover, it does not seek to ‘explain the case fully or to test a theoretical proposition’, but rather aims to conduct an initial probing of the conceptualisation and its plausibility (Levy Citation2008, 6–7).

Conceptualising the smartphone as a security device

An analytics of devices

Security studies scholars have recently started paying more attention to the technical instruments that security actors use to practice security. Spearheading this surge in interest in technical objects and their use, Amicelle, Aradau, and Jeandesboz (Citation2015) have argued for employing an ‘analytics of security devices’ when studying the impact of technology on the production of security. Acknowledging that devices have an ‘autonomous force of action developed in relation to the actors who use them’ (300), they locate politics in the relationship between people and things (297, 300), while others have begun to account for the ways in which security is produced in the mediation of that relationship (Tanner and Meyer Citation2015; Grove Citation2015; Meiches Citation2017; Saugmann Citation2020; O’Grady Citation2016).

As such, attending to how devices act and contribute the production of security requires an understanding of performativity that takes seriously the agency of things as well as people. Part of a large body of new materialist political theory that understands matter to be able to act, for instance in terms of vibrancy (Bennett Citation2010) or agentic capacities (Coole Citation2013), Barad (Citation2003) makes the case for a posthumanist performativity. Following Bohr’s ‘philosophy-physics’ (813), Barad argues that material phenomena are the ‘primary ontological unit’ and explains how they exist only as primitive relations that come into being as tangible and meaningful relata through processes of materialisation. She thus deconstructs the distinction between words and things, meaning and matter, and makes the case for paying closer attention to how ‘matter comes to matter’ (823). Doing so, moreover, Barad insists on replacing the more common ‘interaction’ with ‘intra-action’ in order to stress that neither humans nor nonhumans are pre-existing entities with privileges to enunciate or inscribe meaning. Instead, they both come into being and acquire their historically and culturally specific meaning in a dynamic, co-constitutive relationship (814).

On this account, security devices can be conceptualised as technologies that, through intra-action with various other components of material phenomena, draw boundaries and drive processes of materialisation (Barad Citation2003, 816, 820–821). As such, they produce security-phenomena not only by ‘bringing new things into the world’, but also by ‘bringing forth new worlds’ (Aradau 2010, 498). Drawing from Barad’s theory of materialisation, Aradau (2010) has shown how critical infrastructures are securitised through iterative intra-action with people and other material objects. Similarly, O’Grady Citation2016; see also 2016) has demonstrated how internet infrastructure can materialise automation imaginaries and even redistribute security Glouftsios (Citation2017, 2019, Citation2021) has argued that practices for controlling the circulation of non-EU citizens in the EU is dependent on the materiality of large-scale information systems. Following this line of thinking, Amicelle, Aradau and Jeandesboz (Citation2015, 298) argue that devices perform security by (re)configuring social spaces, (re)drawing boundaries and (re)distributing meanings. Hence, their performative effects amount to more than the consolidation of already existing sociotechnical formations, as they themselves ‘draw legal, gender, race, or class boundaries and lines of exclusion’ (298).

Often, security devices are not originally made for security purposes, but taken over by security actors and repurposed for security through processes of appropriation (Amicelle, Aradau, and Jeandesboz Citation2015, 301–302). Through appropriation-processes, banal consumer goods like the smartphone can be ‘used as security devices on a daily basis, even if they have not been made or validated for such a purpose’ (301). As such, it involves ‘seeing things close to us, or considered to be mundane, in new or imaginative ways’, and creatively mobilising and further developing the embodied connection we have with our technological environments (Chandler Citation2018, 181). A form of ‘hacking’, then, appropriation is not merely a way of reusing technology, but also a mode of being where humans ‘become with’ the material world through innovative ‘repurposing and rearranging of what exists already’ (165).

Precisely because this kind of intra-action takes devices out of their original sociotechnical milieu, moreover, and introduces them to new ones, it typically has unintended and unexpected effects (294; Hayles Citation2012, 89; Chandler Citation2018, 150, 175). Such effects can be surprising results of reapplication, or calculated ways of communal organising by security actors who have ‘tricks up their sleeve’ (Chandler Citation2018, 150). Paying attention to appropriation practices thus challenges a ‘clearcut, sequential distinction between social spaces of production and use/consumption of security devices’ (Amicelle, Aradau, and Jeandesboz Citation2015, 301), and especially attunes us to the overlaps and synergies between commercial- and security-domains. In this sense, appropriation can be seen as a driver of ‘detournement’ – a process by which ‘affects, perceptions, and concepts [are transferred] from one domain […] to another (Wark Citation2015, 218). As it ‘pulls into encounter with one another heterogeneous forms of knowledge’ (O’Grady Citation2018, 111), appropriation can thus have transformative effects on both the security sector and daily life, arguably obscuring the difference between the two domains (121). Beginning to explore the performative effects of smartphone-appropriation, the next section turns to the particularities of the smartphone-device in order to unpack the distinctiveness of the human/smartphone-connection.

The human/smartphone-connection

The primary distinguishing feature of the smartphone as a technological device is that it gives immediate and permanent access to the internet (Mazmanian Citation2019, 127; Vordener and Klimmt Citation2020, 55–56). For the first time, human beings have become permanently online and connected, as they have developed a ‘close, intense, even intimate relationship […] with their smartphones and the communication environment to which it grants permanent access’ (Klimmt et al. 2018, 19) Providing ‘truly constant mobile connection’ (Vordener and Klimmt Citation2020, 55), then, but also being easily portable and operable due to its size and convenience (Taipale, Turja, and Lina Citation2020, 657–658; Chambers Citation2016, 198–200) the smartphone stands out from comparable devices such as mobile phones, laptops, tablets, and smart watches.

When enabling connectivity, the smartphone also intra-acts closely with the human body, forging ever more intimate relations between human and machine. Mazmanian Citation2019, 127) notes, ‘the smartphone touches the body’ and intra-acting with it is therefore a highly ‘sensate experience’. Chambers (Citation2016) similarly stresses how the smartphone stands out by the way in which we physically ‘pick up, hold, and use’ (197) it, and also the way in which it sticks to the body and follows us around (198). As a result, the ways in which the body feels and functions has changed with the smartphone. The subject always knows where it keeps the device and has typically come to feel insecure without it (King et al. Citation2013; Yildirim et al. Citation2016). Although smartphone-users experience their self-extension through the device in different ways and to different degrees, incorporation of the smartphone in everyday life, both as an indispensable instrument and as a reflection of (in)secure identities, has become generalised to the extent that conventional distinctions between human and digital selves are now thoroughly blurred (Park and Kaye Citation2019, 226).

Considering that the connection between human and smartphone is not additive and merely functional (Mazmanian Citation2019, 126), moreover, but rather constitutive in the sense that the smartphone changes how the human functions, the human subject is now a smartphone subject. What the smartphone enforces, then, is the human’s embodiment of connectivity. This means that it not only offers connective features for the human to use but makes these features a part of the human body and self. Mazmanian (Citation2017) gives the example of how intra-action between human and smartphone has created what she calls worker/smartphone-hybrids: an entirely new agentic entity through which ‘various aspects of contemporary capitalism are made to matter’ (125, italics in original). For instance, this specific intra-action contributes to the worker-subject’s internalisation of late capitalist norms and desires such as the ‘glorification of busyness’ or the ‘sheepish pride in being “addicted” to one’s smartphone’ (129). In the following, this article will show how the smartphone creates hybrids with security subjects as well, and how such intra-action and specifically the enforcement of embodied connectivity can, to paraphrase Mazmanian (2017, 125), ‘bring various aspects of contemporary security to matter’.

Smartphone-appropriation in a protest setting

Appropriating the smartphone for security purposes thus means mobilising the human’s embodied connectivity in different ways. This article now turns to the protest setting for illustration of how these dynamics play out in practice. Focusing specifically on the BLM protests in the summer of 2020, it takes the protest setting to be diverse and multifaceted in the sense that it encompasses both the streets and social media and consists of activities ranging from peaceful marches to violent resistance (Chernega Citation2017; Tillery Jr. Citation2019). From the perspective of the BLM movement, moreover, and considering the long history of social uprisings against police brutality and racial discrimination of which it is part, protests are seen as resistance against racial inequality and the discriminatory modes of surveillance that uphold it (Browne Citation2015; Canella Citation2018). This is a logical illustration since protests take place on the streets and increasingly also on social media, making the protest setting a site of political struggle and security production where smartphone-use is particularly prominent (Richardson Citation2020, 43–44; Neumayer Citation2020; Neumayer and Stald Citation2014).

The use of smartphones during protests enables the appropriation of its embodied connectivity for security purposes by both protesters and police. Starting with police appropriation, this predominantly takes the shape of monitoring phone data more closely and intensely (Neumayer Citation2020, 246–247). Research on the policing of protests through the use of social media data have suggested that such monitoring changes policing logics from reactive to proactive, as they aim to pre-empt protest activity with help of machine learning. Challenges that follow from this change include the possible perpetuation of pre-existing biases and the increased influence of market-driven software in security-decision making (Dencik, Hintz, and Carey Citation2018). Intra-acting with the protesters, the smartphone operates centrally in this social media assemblage consisting of platforms, police, protesters, software and devices. Specifically, it contributes to the changing of policing logics by affording embodied connectivity and thus offering direct and around-the-clock access to protester activity.

Protester appropriation also mobilises the smartphone/protester intra-action and does so specifically through resisting social media monitoring and countering police brutality more broadly. In resisting social media monitoring, a widespread practice is to obfuscate social media data. Data obfuscation ‘offers a strategy for mitigating the impact of the cycle of monitoring, aggregation, analysis and profiling’ and is done by ‘adding noise’ that makes data ‘more ambiguous, confusing, harder to use’ (Brunton and Nissenbaum Citation2015, 176; see also Monahan Citation2006; Birchall Citation2021). In countering police brutality more broadly, witnessing and documenting events through photo or video has also become a widespread practice (Richardson Citation2020). Often and increasingly, these practices are conducted with smartphones (Neumayer Citation2020), and many even livestream from protests (Bailey 2020). Livestreaming illustrates appropriation of embodied connectivity particularly well since it combines the mobile camera function with always-on connection and immediate access to social media platforms (Kumanyika Citation2016).

Taken together, police and protester appropriations of the smartphone constitute a spiral of surveillance and counter-surveillance (Ullrich and Knopp Citation2018). This is a dynamic of ‘mutual adaptions of the parties in conflict’, where police and protesters act and react to each other’s practices. The character of modern-day surveillance assemblages, in which the smartphone now plays a central part, is thus produced through a ‘constant interplay move and counter-move’ (Wilson and Serisier, 2019, 170; see also Marx Citation2003; della Porta and Tarrow Citation2012).

Some research has also pointed to how the proliferation of the smartphone, and typically its use for picturing and filming at protests to document police violence, is playing into and possibly changing this dynamic. Bock (Citation2016) for instance argues that the use of smartphones for cop-watching can alter the power dynamic of the spiral in favour of the protesters, as this practice enables activists to ‘work in concert with technology to balance police officers’ law enforcement authority’ (29). Canella (Citation2018), on the other hand, holds that state surveillance is always ‘a step ahead of video activists in the contemporary surveillance arms race’ (394) because of its alliance with private companies and aid from market-driven software.

In order to fully appreciate how the spiral of surveillance and counter-surveillance develops, moreover, and indeed to understand the ways in which the smartphone influences it, it is important to acknowledge the racialised character of these processes. As Simone Browne (Citation2015) calls to our attention, surveillance is racialised in the sense that its enactments ‘reify boundaries along racial lines, thereby reifying race [resulting in] discriminatory and violent treatment’ (8). Browne further argues that responses to racialised surveillance must also be understood in terms of patterns of racial discrimination and puts forth the concept ‘dark sousveillance’ (21). Sousveillance is a term commonly used in surveillance studies to describe reversed surveillance – observation by people and of authorities (Newell Citation2020) -, which Browne couples with ‘dark’ to highlight how such practices are responses to a distinctly racialised surveillance.

The smartphone’s intervention in the spiral is thus also a racialised intervention; its affordance of embodied connectivity and the diverse appropriations of this affordance by both protesters and police play into the enactment of differential practices with the potential to reify, but also challenge, racial hierarchies. As discussed above with reference to the performative force of security devices, the smartphone can contribute to the drawing of ‘boundaries and lines of exclusion’ based on gender, class and race (Amicelle, Aradau, and Jeandesboz Citation2015, 298). As such, it reveals how the racialisation of surveillance is a posthuman process because it is conditioned by the materiality of surveillance technology. In the next section, the article turns to the BLM protests in the summer of 2020 as an illustration of how the smartphone intra-acts with various security actors in diverse ways to intervene in the spiral of racialised surveillance and dark sousveillance.

The Black Lives Matter protests as an illustration

Police appropriation

Social media-monitoring

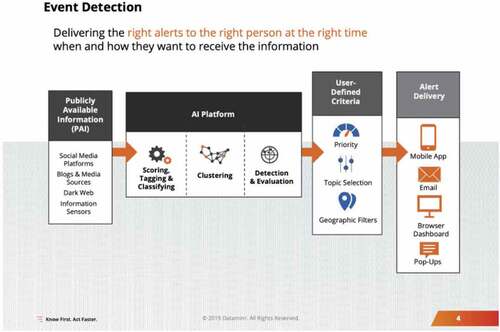

In early July 2020, a handful of weeks after the Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder erupted, it was revealed that the police had hired a private data analytics company to gather and analyse social media data that could be used to monitor and control the protests (Biddle Citation2020a; Horwitz and Olson Citation2020; Morse Citation2020a). The company, called Dataminr, offered a service called ‘First Alerts’, in which it packaged Tweets from or about the protests that could be of relevance to local law enforcement departments. The inclusion of specific tweets in the First Alerts was based on the police’s concrete wishes as communicated to Dataminr, but also by Dataminr’s algorithms and its employees’ subsequent filtering of tweets (Biddle Citation2020b). As shown in , a slide from a leaked presentation that Dataminr gave to the FBI, publicly available information such as social media data passed through Dataminr’s artificial intelligence (AI) platform before being curated by human staff. The process of filtering and selecting tweets to include in First Alerts was, according to sources from inside Dataminr, racially biased. They claimed that the searches for tweets that could be of interest to the police were ‘never targeted towards other areas in the city, it was poor, minority-populated areas’ (Biddle Citation2020b).

Figure 1. A leaked slide from a presentation Dataminr gave to the FBI. Image included in .Biddle (Citation2020b)

Moreover, the police’s access to tweets was also enabled by Twitter and more specifically its partnership with Dataminr and choice to give Dataminr so-called Firehose privileges to the Twitter stream. Firehose is a costly service that Twitter offers to customers and partners that gives near real-time access to 100% of the Twitter stream (Biddle Citation2020a; Perez Citation2020). In addition, Dataminr scanned Snapchat and Facebook in harvesting data for First Alerts as well, where information from Facebook-events for demonstrations were particularly useful for establishing the time and place of protests. In separating between different kinds of data in the First Alerts, moreover, tweets posted by bystanders and participants in the demonstrations were strikingly labelled ‘eyewitnesses’ in Dataminr’s system, indicating that the protesters somehow, even if inadvertently, participated in their own surveillance (Biddle Citation2020a).

The inclusion of protester and Twitter-user @realknowmad’s tweet (see .) from a peaceful demonstration in Minneapolis provides an example of how this worked in practice. On the 31st of May 2020 he tweeted a photo of people standing at a road crossing accompanied by the text: ‘Happening now: peaceful protest outside US Bank Stadium in downtown Minneapolis. End racism. End police brutality. End inequalities and inequities. #JusticeForFloyd #Minneapolisprotest #BlackLivesMatters’. Shortly after it was posted, Dataminr included the tweet in a First Alert that it sent to the Minneapolis police. To supplement the tweet, Dataminr’s human staff also included in the First Alert a caption that specified where the photo had been taken: ‘seen at US Bank Stadium on 400 Block of Chicago Avenue’ (Biddle Citation2020a). With this information, and seen alongside other sources of information, e.g. a Facebook-event for a demonstration, the police could quickly identify where and when a protest was taking place, and subsequently act on that information

Figure 2. @realknowmad’s tweet from the protest in Minneapolis on the 31st of May 2020. Screenshot from Twitter

This shows that the smartphone’s specific intra-action with its users enabled the police to practice security in new ways. For it was only by accessing the protesters’ use of the smartphone’s connective features out on the streets while protesting that the police could retrieve near real-time information about ongoing protests. As such, the police were even dependent on the continued success of the smartphone as a commercial device in its practice of security, since it was the widespread use of on-the-go social media uploads that made it’s monitoring attractive from a surveillance-perspective. The securitisation of @realknowmad’s tweet illustrates this well, because it is a case of how rather normal, everyday social media uploads – the sharing of everyday activity with friends, followers and the wider public – were turned into intelligence information. Moreover, knowing that the turning of @realknowmad’s tweet into intelligence information is just a symptom of how Dataminr’s and the police’s social media monitoring systematically targeted black communities (Biddle Citation2020b), social media monitoring emerges as a distinctly racialised appropriation-practice. In this way, the smartphone intensified racialised surveillance by enabling the mobilisation of embodied connectivity and thus more intrusive monitoring of black bodies.

Geofencing

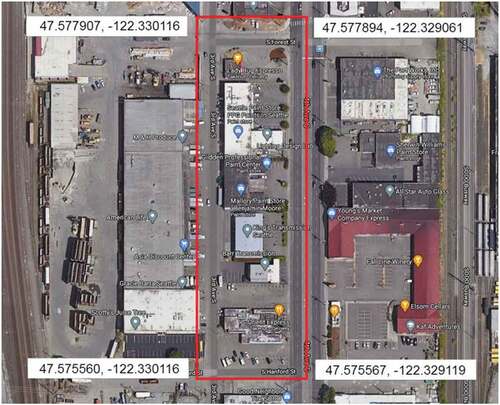

In addition to monitoring social media activity to surveil and control the protests, the police also appropriated the smartphone by accessing and making use of its data transmission in another way, namely via geofencing (Faife Citation2022; Brewster Citation2021; Brandom Citation2021; Whittaker Citation2021). Geofencing is a technique developed for marketing purposes where a marketer can target messaging at smartphones when they enter or leave a predetermined virtual area, delineated by a so-called geofence. This technology uses radio frequency identification, Wi-fi, Bluetooth and GPS signals as well as cellular data that are all transmitted by smartphones to locate devices and trigger messaging (Kemmis Citation2020; Fussel Citation2020). Recently, and with an explosive increase after 2018, US law enforcement has begun issuing geofence warrants to Google, who has harvested location data from smartphone devices through its geolocation service (Fussel Citation2021). Typically, the police issue warrants to investigate a crime, and claim the need to see all devices that have been inside or passed through a specific geographic area near the crime scene on grounds of ‘probable cause’ (Faife Citation2022).

As part of this increase in warrants, the police have asked for access to location data at BLM protests, using allegations of a crime at a protest scene as a pretext for retrieving and seeing the location of large numbers of devices. For instance, the police issued a warrant and was given access in the aftermath of an attempted arson in Seattle in late August 2020. As part of the protests that took place there and in many other cities after the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, two people threw Molotov cocktails at a police building. In response, the police asked Google for information about smartphone devices that had passed through a defined area around the building before and after the incident. In the warrant, they argued that ‘there is probable cause to search information that is currently in the possession of Google and that relates to the devices that reported being within the Target Location’, and requested the release of ‘Location History data, sourced from information including GPS data and information about visible wi-fi points and Bluetooth beacons transmitted from devices to Google’, inside specific coordinates and times (Faife Citation2022; Brewster Citation2021; Brandom Citation2021).

. shows the area that police asked for information about and illustrates how geofence-areas typically (and in cities often unavoidably) encompass locations that the general public would use in their everyday such as sidewalks and parking lots, as well as stores, restaurants and cafes. Also taking into account the time the police specified in the warrant (in this case between 10 pm AND 11.15 pm) it becomes clear that they necessarily got access to the device data of many people not associated with the crime under investigation (Faife Citation2022). In another example, where the police issued a warrant as part of their investigation of a vandalisation of an auto-parts store in Minneapolis soon after George Floyd’s murder, a bystander who was at the scene to film the demonstration, was notified that his Google account information would be given to local law enforcement even though he did not take part in any violent activities (Whittaker Citation2021). Unhappy with this news, the man complained that the police ‘assumed everybody in that area that day is guilty’ (Abdullahi quoted in Whittaker Citation2021).

This too shows how the particularities of human/smartphone-intra-action enable the development of new and more intrusive surveillance practices for the police. Specifically mobilising geolocation to investigate crimes related to the BLM protests, but also to monitor and control the protests at large, the police made use of data that is produced by the embodied connectivity that the smartphone’s intra-action with humans enforces. The practice of geofencing and its success as a security measure is dependent on people actually carrying the smartphone with them at all times, which in turn is dependent on the smartphone being an attractive device for a variety of different purposes such as entertainment and communication.

Through this practice the smartphone thus facilitated the transformation of the most mundane of activities into actionable intelligence information. This transformation was also racialised, moreover, since it disproportionately targeted members of the black community, and specifically BLM protesters. Geofencing inevitably implicates innocent passers-by in criminal investigations (Valentino-DeVries 2019), and since the areas that were geofenced typically ‘provided natural meeting space[s] for anyone who had taken to the streets’ (Brandom Citation2021), these passers-by were often, though not necessarily, black and/or protest-participants. Here too, then, the smartphone arguably intensified racialised surveillance by making movement, and thus in a sense mere existence, a potential source of insecurity for protesters but also for the general public.

Protester appropriation

Obfuscation of phone data

Responding to police appropriation, however, protesters modified their device-use in order to secure their devices and make surveillance of the commercial data it produced more difficult. They did so by obfuscating their phone data in different ways, such as encryption of messages, decoupling of social media profiles and blurring of photos.

Many protesters downloaded messaging apps that offered so-called end-to-end encryption (Nierenberg Citation2020). End-to-end encryption of messages means that the messages are encrypted when they leave one device and can only be decrypted by the intended receiver. In this way, messages cannot be read by internet or app service providers, hackers, the police, or anyone else (Lutkevich and Bacon Citation2021). Whatsapp, one of the most popular messaging apps, offers end-to-end encryption. However, because it is owned by Facebook, who can profit from the app data and has a shifty reputation when it comes to privacy protection, many BLM activists preferred other apps such as Signal, Wickr or Wire (Nierenberg Citation2020; Greenberg and Newman Citation2020). Signal, which is the most popular of these apps, saw a massive increase in downloads during the first weeks after George Floyd’s murder (Nierenberg Citation2020; Morse Citation2020b). This is a testament to the demand for data security during the BLM protests, and to the importance of modifying smartphone-use in order to achieve it.

In addition to using encrypted messaging apps, protesters were encouraged to decouple from their phone data. This could mean turning off as many tracking features on the smartphone as possible, such as Google’s geolocation history service. It could also entail using a different phone when protesting or creating completely new social media profiles before joining a protest. One more specific advice was to create a new Gmail account and then use that to download encrypted messaging apps. In this way, even encrypted messages – if captured by the police – would be hard to link to an individual (Greenberg and Newman Citation2020; Cox and Fransceschi-Bicchierai Citation2020; Chaudry and Krasnoff Citation2022).

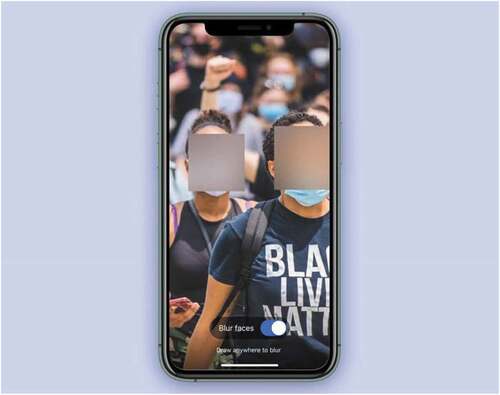

A final example of an obfuscation-practice is the blurring of photos. Among others, Amnesty International (amnesty.org, 12 June 2020) encouraged protesters to ‘Be mindful of others’ privacy’ and remember to ‘obscure their identities in pictures before sharing or publishing them’. This, they argued, would make it more difficult for the police to identify protesters and thus to ensure that the smartphone did not act as an ‘unintentional surveillance camera’ (Morrison and Estes Citation2020). @realknowmad’s tweet that was discussed above, where no identifiable faces are shown in the picture and no names given in the text, is a good example (see .). Taking even more active steps to obscure identities, protesters could also use software for blurring faces. In wanting to aid the protesters, Signal even launched a photo blurring tool soon after the protests started, making it easy for protesters to obscure the identities of people they had photographed when uploading pictures to the app or elsewhere (Vincent Citation2020; see .).

The kind of human/smartphone intra-action we see here is arguably different from the practices of police appropriation discussed above in the sense that it was seemingly not a mobilisation of embodied connectivity, but rather the opposite of that: a distancing from and reversal of the connectivity that the police mobilised in order to control protests through social media monitoring and geofencing. At the same time, a case can be made that these practices were also a negotiation and further development of embodied connectivity. The human was still embodying the connective features that the smartphone offers but mobilised the dexterity that comes with embodiment in order to alter the specific character of this embodiment for security purposes.

Data obfuscation-practices thus show how the smartphone’s affordance of embodied connectivity enables counter-surveillance as well as surveillance, and specifically for the BLM context, countermoves that resist racialised surveillance. As such, the device, and in particular its intimate intra-action with protesters, helped create a spiral of racialised surveillance and counter-surveillance that is characterised by close surveillance of everyday activities as well as the active use of everyday behaviour and mundane uses of the (extended) body to resist such surveillance.

Livestreaming

As part of a broader category of security practices employed by protesters that took on different forms of visual documentation, livestreaming is a practice unique to the smartphone that was used extensively during the BLM protests. During the protests, people livestreamed events on different platforms such as the social media sites Instagram, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, but also from platforms designed for streaming such as Twitch (Nieva 2020; Bailey 2020; Browning 2020).

A Minneapolis media collective called Unicorn Riot, has gained significant media traction for its use of livestreaming. They livestreamed much of the protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, and often streamed for five or more hours at a time (Patterson 2020; Gabbat 2020). ‘What I’m trying to do is to allow the community speak’ (Georgiades quoted in Patterson 2020) one streamer from Unicorn Riot said. He also argued that the streams could function ‘as a microphone for the community’ with the potential to stop ‘corporate news [to] come and sort of distort their story’ (Georgiades quoted in Gabbatt 2020). ‘The coverage is impressive for its intimacy with the community and unrivalled in its ability to tell the story patiently, in hour upon hour in searching the streets for clarity’ (Patterson 2020), one reporter noted, while another claimed that the livestreams were well equipped to offer nuance and complexity (Bailey 2020).

A prominent example is the livestreaming of the incident where local restaurant owner David McAtee was shot and killed by the police in Louisville, Kentucky on 1 June 2020. The police, supported by the National Guard, were in the predominantly black West End neighbourhood of Louisville to impose the curfew that had been put in place to stop BLM demonstrations. In their confrontation with a group of protesters who were violating the curfew, they shot and killed McAtee. Close by, activist Kris Smith was out drinking with his friends and was already streaming from Facebook Live when the shooting started. Smith’s video captured the scene of the shooting and documented how the police broke up the crowds with sounds of gunfire in the background. The footage was seen live by many and later used by the media to report on the incident. On his own account, Smith livestreamed because he ‘wanted everybody to see exactly what was going on’ and thus to hold the police accountable for their actions (Nieva 2020; Mazzei 2020; Kachmar 2021).

This example speaks to the authenticity invoked by livestreams. Smith’s film streamed to people at home and others that were protesting at the same time, and thus functioned as evidence of police brutality as well as a force of unification (Kumanyika Citation2016). In this way, it also demonstrates the distinct contribution of the smartphone and how it intra-acts with human users to produce security effects. Livestreaming explicitly demonstrates how protesters mobilised embodied connectivity for security purposes, since the practice combines the smartphone’s mobility with its camera function and most importantly, instant uploads. The fact that Smith was already streaming for non-security purposes, moreover, shows how the smartphone operates as a security device by offering commercial features for appropriation. Here, it was the embodied connectivity enforced by the smartphone-device outside of security contexts that made it attractive and successful as a security device as well.

As a form of dark sousveillance, the livestreaming practice responded directly to the racialised surveillance conducted by the police, and thus also took part in producing security in the context of the BLM protests as a spiral of racialised surveillance and counter-surveillance. Moreover, the livestreaming practice also shows how the smartphone’s affordance of embodied connectivity enables more active resistance through observation and documentation, and as such, how the device moves the mediation of the spiral to the protesters’ (extended) bodies.

Conclusion

This article has argued that the smartphone operates as a distinct security device through the ways in which it intra-acts with human security actors, and specifically by affording embodied connectivity that can be mobilised for security purposes through processes of appropriation. Looking to the BLM protests in the summer of 2020 as an illustration, it has shown how the smartphone can be appropriated for security purposes in multifaceted ways and by a diverse set of actors. Police and protesters both mobilised the device’s uniquely intimate connection to the protesters’ bodies: the police primarily by intensifying surveillance, and protesters by crafting new techniques to resist this surveillance but also to counter police brutality more generally. This illustrates the significance of the specific ways in which the smartphone intra-acts with human security actors. It was for instance only because the protesters always carried their smartphones that the police could monitor them so closely, and only due to the smartphone’s always-on connection that protesters could livestream from the protests.

By enabling the creation of new security practices by different actors, the smartphone also contributed to the materialisation of security in context of the BLM protests. This article has theorised this materialisation in terms of the spiral of surveillance and counter-surveillance (Ullrich and Knopp Citation2018; Wilson and Serisier Citation2010). The illustration above shows that police and protesters appropriated the smartphone in patterns of action and reaction, move and countermove, that took on the shape of a spiral. The police’s intensified monitoring of social media data was a response to and exploitation of the fact that protesters were carrying their smartphones to protest (whether for security purposes or not). At the same time, the protesters’ use of the smartphone for security purposes, through documentation and obfuscation, was a response to the police’s intensified monitoring of social media data and police brutality.

As it materialised through smartphone-appropriation at the BLM protests, moreover, this spiral was racialised. The police’s appropriations of the smartphone discriminated against protesters based on race and colour, as is visible both from their direct targeting of black communities in its social media-monitoring, but also from their more indirect framing of bystanders through the geofencing practice. The protesters’ appropriations, on the other hand, were direct responses to this discrimination and as such, ‘freedom practices’ that aimed to ‘facilitate survival and escape’ (Browne Citation2015, 21).

More fundamentally, though, the smartphone appears to have intervened in the racial surveillance/dark sousveillance-spiral by (re)locating the negotiation of competing security interests in the (extended) bodies of the protesters. Because it enabled the appropriation of embodied connectivity and exploitation of the attractiveness of the smartphone’s commercial features, it allowed security actors to make use of the intimate relationship between user and device. This also made the protesters’ bodies, and indeed its mundane, everyday uses – such as walking or shopping in the case of geofencing or social media-posting in the case of monitoring and livestreaming – sites of political struggle and contentious security production. This has the tangible effect of facilitating the acceleration and intensification of the spiral, in the sense that it allows for more comprehensive and intrusive surveillance as well as more active and responsive resistance.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to three anonymous reviewers, to Charlotte Wagnsson, Stefan Borg and Sara van Der Hoeven, and to the Security research group at PRIO for generous and insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Håvard Rustad Markussen

Håvard Rustad Markussen is a PhD-student in Political Science at the Swedish Defence University. His research combines insights from Critical Security Studies and Science and Technology Studies to interrogate the role of commercial technology in the production of security.

References

- Amicelle, A., C. Aradau, and J. Jeandesboz. 2015. “Questioning Security Devices: Performativity, Resistance, Politics.” Security Dialogue 46 (4): 293–306. doi:10.1177/0967010615586964.

- Barad, K. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs 28 (3): 801–831. doi:10.1086/345321.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Biddle, S. 2020a. “Police Surveilled George Floyd Protests With Help From Twitter Affiliated Startup Dataminr.” The Intercept. July 9.

- Biddle, S. 2020b. “Twitter Surveillance Startup Targets Communities of Color for Police.” The Intercept. October 21.

- Birchall, C. 2021. Radical Secrecy: The Ends of Transparency in Datafied America. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bock, M. A. 2016. “Film the Police! Cop-Watching and Its Embodied Narratives.” Journal of Communication 66 (1): 13–34. doi:10.1111/jcom.12204.

- Boyd, M. J., and J. L. Sullivan . 2021. “Understanding the Security and Privacy Advice Given to Black Lives Matter Protesters.” In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’21), May 8- 13

- Brandom, R. 2021. “How Police Laid down a Geofence Dragnet for Kenosha Protesters.” The Verge. August 30.

- Brewster, T. 2021. “Google Dragnets Gave Cops Data on Phones Located at Kenosha Riot Arsons.” Forbes. August 26.

- Browne, S. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Brunton, F., and H. Nissenbaum. 2015. Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Canella, G. 2018. “Racialized Surveillance: Activist Media and the Policing of Black Bodies.” Communication, Culture, Critique 11 (3): 378–398. doi:10.1093/ccc/tcy013.

- Chambers, P. 2016. “Smartphone.” In Making Things International 2: Catalysts and Reactions, edited by M. B. Salter. 195-215. University of Minnesota Press.

- Chandler, D. 2018. Ontopolitics in the Anthropocene: An Introduction to Mapping, Sensing and Hacking. London and New York: Routledge.

- Chaudry, A., and B. Krasnoff. 2022. “How to Secure Your Phone before Attending a Protest.” In The Verge, 5. May.

- Chernega, J. 2017. “Black Lives Matter: Racialised Policing in the United States.” Comparative American Studies 14 (3–4): 234–245. doi:10.1080/14775700.2016.1267322.

- Coole, D. 2013. “Agentic Capacities and Capacious Historical Materialism: Thinking with New Materialisms in the Political Sciences.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 41 (3): 451–469. doi:10.1177/0305829813481006.

- Cox, J., and L. Franseschi-Bicchierai. 2020. “How to Protest without Sacrificing Your Digital Privacy.” Vice. June 1.

- Del la Porta, D., and S. Tarrow. 2012. “Interactive Diffusion. The Coevolution of Police and Protest Behavior with and Application to Transnational Contention.” Comparative Political Studies 45 (1): 119–152. doi:10.1177/0010414011425665.

- Dencik, L., A. Hintz, and Z. Carey. 2018. “Prediction, Pre-emption and Limits to Dissent: Social Media and Big Data Uses for Policing Protests in the United Kingdom.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1433–1450. doi:10.1177/1461444817697722.

- Engblad, E. 2021. “Telefonen gjør oss både smartere og dummere.” In sv.uio.no, University of Oslo.

- Faife, C. 2022. “FBI Used Geofence Warrant in Seattle after BLM Protest Attack, New Documents Show.” The Verge. February 5.

- Fussel, S. 2020. “Creepy ‘Geofence’ Finds Anyone Went near a Crime Scene.” Wired. September 4.

- Fussel, S. 2021. “An Explosion in Geofence Warrants Threatens Privacy across the US.” Wired. August 27.

- Glouftsios, G. 2017. “Governing Circulation through Technology within EU Border Security practice-networks.” Mobilities 13 (2): 185–199. doi:10.1080/17450101.2017.1403774.

- Glouftsios, G. 2021. “Governing Border Security Infrastructures: Maintaining large-scale Information Systems.” Security Dialogue 52 (5): 452–470. doi:10.1177/0967010620957230.

- Greenberg, A., and L. H. Newman. 2020. “How to Protest Safely in the Age of Surveillance.” In Wired, 31. May.

- Grove, N. S. 2015. “The Cartographic Ambiguities of HarassMap: Crowdmapping Security and Sexual Violence in Egypt.” Security Dialogue 46 (4): 345–364. doi:10.1177/0967010615583039.

- Hayles, K. 2012. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Horwitz, J., and P. Olsen. 2020. Twitter Partner’s Alerts Highlight Divide Over Surveillance. Wall Street Journal, September 29.

- Kemmis, A. 2020. “What Is Geofencing?” In SmartBug, 8.

- King, A. L. S., A. M. Valenca, A. C. O. Silva, T. Baczynski, M. R. Carvalho, and A. E. Nardi. 2013. “Nomophobia: Dependency on Virtual Environments or Social Phobia?” Computers in Human Behavior 29 (1): 140–144. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.025.

- Kumanyika, C. 2016. “Livestreaming the Black Lives Matter Network.” In DYI Utopia: Cultural Imagination and the Remaking of the Possible, edited by A. Day, 169–188. London: Lexington Books.

- Levy, J. 2008. “Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 25 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/07388940701860318.

- Ling, R., L. Fortunati, G. Goggin, S. S. Lim, and L. Yuling. 2020. “An Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society, edited by R. Ling, L. Fortunati, G. Goggin, S. S. Lim, and L. Yuling, 3–13. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190864385.013.44.

- Lutkevich, B., and M. Bacon. 2021. “end-to-end Encryption (E2EE).” In Techtarget.

- Marx, G. 2003. “A Tack in the Shoe. Neutralizing and Resisting the New Surveillance.” Journal of Social Issues 59 (2): 369–390. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.00069.

- Mazmanian, M. 2019. “Worker/Smartphone Hybrids: The Daily Enactmens of Late Capitalism.” Management Communication Quarterly 33 (1): 124–132. doi:10.1177/0893318918811080.

- Meiches, B. 2017. “Weapons, Desire, and the Making of War.” Critical Studies on Security 5 (1): 9–27. doi:10.1080/21624887.2017.1312149.

- Monahan, T. 2006. “Counter-surveillance as Political Intervention?” Social Semiotics 16 (4): 515–534. doi:10.1080/10350330601019769.

- Morrison, S., and A. C. Estes. 2020. “How Protesters are Turning the Tables on Police Surveillance.” Vox. June 12.

- Morse, J. 2020a. “Dataminr Helped Cops Surveil Black Lives Matter Protesters, Report Finds.” Mashable, July 9. https://mashable.com/article/dataminr-twitter-black-lives-matter-protests

- Morse, J. 2020b. “Encrypted Signal App Downloads Skyrocket Amidst Nationwide Protests.” Mashable, June 3. https://mashable.com/article/signal-downloads-skyrocket-nationwide-protests-george-floyd

- Nathaniel, O. 2021. “Automating Security Infrastructures: Practices, Imaginaries, Politics.” Security Dialogue 52 (3): 231–248. doi:10.1177/0967010620933513.

- Neumayer, C. 2020. “Political Protest and Mobile Communication.” In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society, edited by R. Ling, L. Fortunati, G. Goggin, S. S. Lim, and L. Yuling, 244–256. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190864385.013.17.

- Neumayer, C., and G. Stald. 2014. “The Mobile Phone in Street Protest: Texting, Tweeting, Tracking, and Tracing.” Mobile Media and Communication 2 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1177/2050157913513255.

- Newell, B. C. 2020. “Introduction: The State of Sousveillance.” Surveillance & Society 18 (2): 257–261. doi:10.24908/ss.v18i2.14013.

- Nierenberg, A. 2020. “Signal Downloads are Way up since the Protests Began.” The New York Times, June 12. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/11/style/signal-messaging-app-encryption-protests.html

- O’Grady, N. 2016. “Protocol and the post-human Performativity of Security Techniques.” Cultural Geographies 23 (3): 495–510. doi:10.1177/1474474015609160.

- O’Grady, N. 2018. Governing Future Emergencies: Lived Relations to Risk in the UK Fire and Rescue Service. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Park, C. S., and B. K. Kaye. 2019. “Smartphone and Self-Extension: Functionally, Anthropomorphically, and Ontologically Extending Self via the Smartphone.” Mobile Media and Communication 7 (2): 215–231. doi:10.1177/2050157918808327.

- Perez, S. 2020. “Twitter Introduces a New, Fully Rebuilt Developer API, Launching Next Week.” Techcrunch.

- Richardson, A. 2020. Bearing Witness while Black: African Americans, Smartphones, and the New Protest #journalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Saugmann, R. 2020. “The Security Captor, Captured. Digital Cameras, Visual Politics and Material Semiotics.” Critical Studies on Security 8 (2): 130–144. doi:10.1080/21624887.2020.1815479.

- Taipale, S., T. Turja, and V. A. Lina. 2020. “Robotization of Mobile Communication.” In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society, edited by R. Ling, L. Fortunati, G. Goggin, S. S. Lim, and L. Yuling, 653–666. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190864385.013.42.

- Tanner, S., and M. Meyer. 2015. “Police Work and New Security Devices: A Tale from the Beat.” Security Dialogue 46 (4): 384–400. doi:10.1177/0967010615584256.

- Tillery, J. A. 2019. “What Kind of Movement Is Black Lives Matter? the View from Twitter.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 4 (2): 297–323. doi:10.1017/rep.2019.17.

- Ullrich, P., and P. Knopp. 2018. “Protesters’ Reactions to Video Surveillance of Demonstrations: Counter-Moves, Security Cultures, and the Spiral of Surveillance and Counter-Surveillance.” Surveillance & Society 16 (2): 183–202. doi:10.24908/ss.v16i2.6823.

- Vincent, J. 2020. “Signal Introduces New face-blurring Tool for Android and iOS.” The Verge, June 4. https://www.theverge.com/2020/6/4/21280112/signal-face-blurring-tool-ios-android-update

- Vordener, P., and C. Klimmt. 2020. “The Mobile User’s Mindset in a Permanently Online, Permanently Connected Society.” In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society, edited by R. Ling, L. Fortunati, G. Goggin, S. S. Lim, and L. Yuling, 54–67. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190864385.013.4.

- Wark, M. 2015. Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene. London: Verso.

- Whittaker, Z. 2021. “Minneapolis Police Tapped Google to Identify George Floyd Protesters.” TechCrunch, February 6. https://techcrunch.com/2021/02/06/minneapolis-protests-geofence-warrant/

- Wilson, D., and T. Serisier. 2010. “Video Activism and the Ambiguities of Counter-Surveillance.” Surveillance &Society 8 (2): 166–180. doi:10.24908/ss.v8i2.3484.

- Yildirim, C., E. Sumuer, M. Adnan, and S. Yildirim. 2016. “A Growing Fear: Prevalence of Nomophobia among Turkish College Students.” Information Development 32 (5): 1322–1331. doi:10.1177/0266666915599025.