ABSTRACT

In this article we use the concept of Communities of Practice (CoP) to understand how Swedish school sport teachers enact the admission process, the identification and selection of student athletes, to Swedish national upper secondary elite sport schools (SNESS). Data were gathered by conducting six focus group interviews involving 18 school sports teachers representing six different sports. The findings indicate that the admission process is influenced by and enacted through sport-specific CoPs and include a strategic identification of athletes, a set of tools – physical aptitude tests, sport-specific training, interviews, social activities – and documents (matrices, forms, interview-guides). While the process constitutes individual subjective assessments of athletes, the findings also imply that the teachers’ common engagement is the central enterprise of their collective actions. The admission is a cooperative process where the teachers expend their collective competence, joint cumulative experience, to identify, assess, and select student athletes.

Introduction

The integration of education and competitive, or elite, sport has become a common practice worldwide. One prominent example is the prevalence of interscholastic and collegiate sports in the United States, where schools implement and organise competitions (Pot & van Hilvoorde, Citation2013, Stokvis, Citation2009). Similarly, in the United Kingdom, out-of-school-hour programmes offer students additional sporting opportunities and increased participation in high-quality competitions within school environments. However, it is important to note that while such school sport activities are widely acknowledged, they are regarded as extra-curricular activities and are not integrated into schools’ regular curricula.

In contrast, in many countries in Europe, the combination of education and sport is arranged through what are known as school sport programmes (Andersson, Citation2023 Radtke & Coalter, Citation2007). Unlike extra-curricular activities, school sport programmes aim to optimise the regular school day in relation to sport-specific training. In Sweden, school sports are carried out in the format of a school subject (special sports), which has a designated national syllabus and grading criteria, irrespective of the sport of the students, at Swedish national upper secondary elite sport schools (SNESS). While special sports education is gender-mixed, and the majority of activities encompass a combination of theoretical (e.g. sport psychology) and practical, sport-specific lessons (e.g. orienteering/canoeing training), the primary function of the subject is to facilitate the acquisition of sport-specific skills (Ferry, Meckbach, & Larsson, Citation2013).

SNESS was introduced as early as 1972 and is a collaboration between the Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE), the Swedish Sports Confederation (SSC), Special Sports Federations (SSF), upper secondary schools and sports clubs. While the SNAE governs and regulates the subject special sports, the SSC have the overall sporting responsibility of the SNESS and propose which sports are to be included in the system, how many student athletes each sport is entitled to and assessments of quality (SSC, Citation2023). Further, each SSF, in cooperation with local elite sports clubs and school sports teachers, coordinates and develops SNESS-activities, such as the admission process – the practice of identifying and selecting pupils to sport schools (SSC, Citation2012).

This collaboration demonstrates the blurring of borders between education and sports (Brown, Citation2015a, Brown, Citation2015b, Ferry, Citation2016, Peterson, Citation2008). In other school sport contexts, such as physical education (PE), these blurred borders are derived to conflicting social fields (Peterson, Citation2008) or discourses (Brown, Citation2015a, Brown, Citation2015b), encompassing the drive for success in high-performance sports and the promotion of general well-being and physical activity for individuals of all levels.

Following this discussion, special sports are an area where the intersection is even more evident in that participants, i.e. school sport teachers, are simultaneously influenced by the two different fields’ demands and requirements. The school sport teachers are expected to run the daily operations in SNESS, which includes educating student athletes through the subject special sports (Ferry, Citation2016, Hedberg, Citation2014). However, the teachers are also expected to identify and select the athletes they wish to educate and assist in their development of sporting skills. School sport teachers, therefore, face the challenging task of navigating and reconciling the conflicting rationales that exist within the realm of the subject special sports.

While rich insight has been gathered on school sports policy and practice (Radtke & Coalter, Citation2007, Morris et al., Citation2021), talent development in sport schools (Berntsen & Kristiansen, Citation2020; Kristiansen & Stensrud, Citation2020), student athletes learning experiences in school sport programmes (e.g. Brown, Citation2016), as well as the dual career (e.g. Saarinen et al., Citation2020, Stambulova et al., Citation2015), there remains much scope for further work on the role of practitioners in school sport programmes and participatory perspectives of the practice in sport school environments, which is influenced by wider contextual elements (such as educational regulations and sports policy) (Andersson, Citation2023). Hence, gaps remain in our comprehension of the social dynamics that shape and influence the work of school sport teachers, particularly in terms of understanding their enactment of specific tasks such as admission processes, the identifying and selecting of student athletes.

Against this backdrop, this paper directs its empirical attention to the exploration of school sport teachers’ practice, specifically the admission process. In order to do so, we apply the concept of Community of Practice (CoP) which has become a widely used theoretical perspective since it was first introduced by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger in 1991 (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Sport science scholars have used the concept to both develop knowledge and understand issues regarding various coaching processes such as coach education, the improvement of quality in coaching and coach pedagogy, to engage in coaches’ own learning (Cassidy & Rossi, Citation2006, Cassidy, Potrac, & McKenzie, Citation2006, Culver & Trudel, Citation2006, Hedberg, Citation2014, Jones, Morgan, & Harris, Citation2012, Whitaker & Scott, Citation2019). The main idea with the concept is to bring to the fore how sociality among practitioners, in a shared practice, impacts learning and understanding (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, Wenger, Citation2000, Wenger, McDermott & Snyder, Citation2002, Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2015). Following this line of thought, the aim of this article is to utilise the concept of CoP to understand how Swedish school sport teachers enact the admission process, the identification and selection of student athletes, to Swedish national upper secondary elite sport schools (SNESS). The study was guided by the following research questions:

How is the admission process described by the school sport teachers?

How can the interaction between the school sport teachers throughout the admission process be understood from a CoP-perspective?

Moving forward, the article progresses through the following steps. Initially, we provide a concise overview of the study’s context, encompassing research on talent identification, as well as the legislation and guidelines that school sports teachers must consider during the admission process to SNESS. Then we develop how the concept of CoP is used in this article followed by the methods and materials employed. Subsequently we present and discuss the findings, in which we extend the understanding of how school sport teachers enact the admission process, which requires a common engagement, a “shared repertoire” and a collective and systemised group focused process (Wenger, Citation1998, p. 82).

Background

In recent decades, there has been an increasing focus on the efficient identification and development of athletic talent in numerous countries (e.g. Green, Citation2003, Martindale, Collins & Daubney, Citation2005). As a result, sport schools have emerged and gained significant prominence in Europe, assuming a pivotal role in talent development systems (Radtke & Coalter, Citation2007).

Sport schools are not for everyone, but in fact only for those who have been identified as talented with potential to achieve sporting success at elite level in the future (Bjørndal & Gjesdal, Citation2020, De Bosscher, De Knop, & Vertongen, Citation2016, Emrich, Frohlich, Klein, & Pitsch, Citation2009, Ferry & Lund, Citation2018, Morris et al., Citation2021). However, talent identification, the process of recognising current participants with the potential to become elite athletes is complex (Bailey & Morley, Citation2006, Roberts et al., Citation2019) and, often, based upon the subjective judgements of practitioners (e.g. coaches) when assessing the potential of young athletes (Christensen, Citation2009, Lund & Söderström, Citation2017, Williams & Reilly, Citation2000). When coaches are questioned about their methods for identifying talented athletes, they often mention relying on a “gut feeling” or “instinct” as their preferred approach (Johansson & Fahlén, Citation2017, p. 475). They highlight that their coaches’ “eye for talent” (Christensen, Citation2009, p. 379) serves as the most crucial tool, enabling them to discern familiar patterns of characteristics that their experience has taught them are indicative of future high-level performance (Roberts et al., Citation2019). Coaches’, thereby, develop a “practical sense” (Lund & Söderström, Citation2017, p. 252) and a “taste for certain perceived traits”, representing the image of a talented athlete, guided by previous experiences of talent identification (Christensen, Citation2009, p. 379).

While this area of research is most often approached through data collection in archetypal sport environments, i.e. sport clubs, national teams etc., there is limited exploration of the subject within a sport school context (Andersson, Citation2023). Although often mentioned, few studies delve into the specific details of the identification of student athletes to school sport programmes (c.f. Brown, Citation2015a, Emrich, Frohlich, Klein, & Pitsch, Citation2009). That background in mind, concerns, primarily in Scandinavian countries, have been raised as to whether school sport programmes are socially inclusive, being often skewed in favour of those from upper income backgrounds (Ferry & Lund, Citation2018, Skrubbeltrang et al., Citation2020, Kristiansen & Houlihan, Citation2017). In Sweden, even though the school sport system is well developed and evaluated as a well-designed system in an international comparative study (Radtke & Coalter, Citation2007), research shows a significant excess of pupils born in the first quarter (Lund & Olofsson, Citation2009, Peterson & Wollmer, Citation2019) known as the relative age effect (Cobley, Baker, Wattie, & McKenna, Citation2009) and a higher proportion of pupils from families with high educational capital (Ferry & Lund, Citation2018, Lund & Olofsson, Citation2009). Thereby, social characteristics impact which categories of pupils partake in the school sport programmes. So far, this research is limited to variables depending on social structure and fails to address the process and practice of how, and through which methods, the pupils are selected. Thus, the admission process remains an understudied area that requires more attention (Andersson, Citation2023), particularly given its annual recurrence and its role in blurring the lines between education and sports (Brown, Citation2015a, Brown, Citation2015b, Ferry, Citation2016, Peterson, Citation2008).

This article addresses admission processes and school sport teachers in SNESS. In the specific context of this study, we will, in the following, present the conditions – legislation and guidelines – which school sports teachers need to take into account before and while identifying and selecting student athletes.

The admission

SNESS have nationwide admissions to which all pupils in 9th grade can apply. However, the schools have a restricted entry governed by the Education Act and policy documents issued by the SSC. School legislations states that “The applicant who is thought to have the best chances of utilising the school sport programme should be given priority when selections are made” (SFS, Citation2010:2039, Chapter 5, Section 26), while the SSC (Citation2012) stresses that the schools are for talents with the prerequisite skills to reach national or international elite as adults.

The admission to SNESS involves both sports-specific qualities and academic merits and is therefore regulated by two conditions, (1) elementary school grades for applying to an upper secondary school programme and (2) athletic ability. School grades for applying to upper secondary school programmes are a standardised system and fall outside the scope of this article. The assessment of athletic ability, of which the SSC (Citation2012) has formulated general guidelines (), is shaped by each SSF, and facilitated by school sports teachers. The guidelines include five specific assessment areas, each provided with respective features with sport-specific knowledge and skills being the most detailed (see below).

Table 1. Guidelines for assessment of athletic ability (SSC, Citation2012.).

Each of the SSFs (e.g. the Swedish Athletics Federation) is entitled to develop its own methods for the assessments of sports-specific knowledge and skill, in accordance with their athletic profile – what is required to reach national and international elite level and full potential as human beings and athletes (SSC, Citation2012).

In summary, the general guidelines for assessment of athletic ability are set out by the SSC and specified by each SSF. In this article, however, we focus on the admissions process as described by the school sport teachers. While doing so we will, theoretically, explore how the teachers in their enactment of identifying and selecting student athletes, embrace (or advocate) a reflective practice, in communities (Culver & Trudel, Citation2006; Wenger, Citation1998; Whitaker & Scott, Citation2019).

Theoretical perspective

As revealed in the introduction, the aim and the structure of this study are based upon the concept of Communities of Practice (CoP). The concept was developed through research of apprenticeship, in which a trainee learns an art, trade, or job under another and gradually develops to a full participant in a specific socio-cultural practice (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Grounded in a social constructivist approach, Lave and Wenger’s (Citation1991) seminal work regarded (a social theory of) learning through the process of “legitimate peripheral participation” (p. 29). In this study we are deliberately shifting the focus from the original usage of the concept to the later works of Wenger (Citation1998) and Wenger et al. (Citation2002) in which the communities, formed by people who engage in a process of collective learning in a shared domain, are at the centre.

The definition of CoP varies. Initially, Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) defined a CoP as “a set of relations among persons, activity, and world, over time and in relation with other tangential and overlapping communities of practice” (p. 98). This definition is vaguer than the narrower account used by Wenger et al. (Citation2002) in which CoPs are defined as “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” (p. 4). Following the latter definition, this group of people display three main characteristics: (1) a shared practice, (2) a common engagement forged in participating in a practice together, and (3) a set of tools developed to help in the performance of the practice. Moreover, the group have a common interest in the specific domain in which they share language, documents, tacit conventions, implicit rules, embodied understandings, underlying assumptions, and mutual world views. Additionally, the group actively work on advancing the general knowledge of the domain, and improving their skills, such as a group of engineers working on similar problems (Wenger, Citation1998, Wenger, Citation2000, Wenger et al., Citation2002, Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, Citation2015).

A CoP’s perspective highlights the influence of social interactions among practitioners and how it impacts the way in which practices are enacted, shared and learned. The concept has become a widely utilised theoretical construct across multiple social science disciplines, such as education (Hodkinson & Hodkinson, Citation2004b, Koliba & Gajda, Citation2009), with which to understand localised and specific workplace learning of, for example, schoolteachers (Hodkinson & Hodkinson, Citation2003, Hodkinson & Hodkinson, Citation2004a). Sport science scholars have applied the concept to develop knowledge and to understand issues regarding coaching processes (Cassidy & Rossi, Citation2006; Cassidy, Potrac, & McKenzie, Citation2006; Jones, Morgan, & Harris, Citation2012; Lund & Söderström, Citation2017; Whitaker & Scott, Citation2019). In this body of research, and beyond (for example Berntsen & Kristiansen, Citation2020), it is recognised that coaches value learning from other coaches, and perceive conversations with other coaches as valuable for their development of knowledge.

Following this line of thought, we intentionally redirect the focus from the original application of the concept, which primarily focused on the learning process of newcomers in a workplace (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, p. 29). Here, we are primarily concerned with qualified and experienced school sport teachers, and their practice.

Method

The empirical basis for this paper was obtained through a comprehensive evaluation of SNESS admission procedures conducted at a national level, commissioned, and funded by the SSC (see, Fahlström, et al., Citation(2023)). While the evaluation addresses broader questions regarding the admission processes in SNESS, this article highlights how school sport teachers engage in the admission process.

The research of this study draws on a multiple case study design. A multiple case study involves the in-depth analysis of two or more cases or instances of a phenomenon, such as individuals, or organisations, so as to understand the commonalities, differences, and patterns that exist between them. A multiple case study is suitable when the inquirer has identifiable cases with boundaries, and the purpose is to provide an in-depth understanding or a comparison of several cases (Stake, Citation1995, Yin, Citation2018). The intent of this study was to understand a specific issue (the admission process), which we illustrated and explored by selecting multiple cases.

The sports (cases) to be studied were selected in collaboration with the SSC. Currently, SNESS is accessible in 26 sports at 48 schools (SSC, Citation2023). Out of these 26 sports, 20 are offering individual sports, of which six were selected for this study: alpine skiing, canoeing, cross-country skiing, orienteering, swimming, and athletics. The sports were chosen based on the fact that they were subject to broadly the same funding, regulations and government policy and they could display different perspectives of the admission process, yet at the same time be compared (Yin, Citation2018).

Procedure

The preparation for data collection involved each SSF, which assisted in contacting school sport teachers. 18 school sport teachers (Male = 13, Female = 5) agreed to participate. The teachers’ SNESS experience ranged from 1 year to over 40 years, and out of 18 teachers, all but two had ten or more years of experience in enacting admission processes.

The interviews were conversational, a method which challenges the conservative construction of the research interview (Burgess-Limerick & Burgess-Limerick, Citation1998). Instead of a setting guided by question followed by answer, the conversational interview allows the researcher and participants to be perceived as co-workers. Thereby, a less charged hierarchical interviewer and interviewee situation was created. Moreover, Yin (Citation2018) suggests that the multiple case study design should use the logic of replication, in which the inquirer replicates the procedures for each case. That in mind, the procedure of the conversational interviews was replicated in every focus group interview.

The interviews were conducted digitally and lasted between 76 and 107 minutes. All focus-group interviews were, with consent from the participants, recorded and transcribed for further analysis.

Analysis

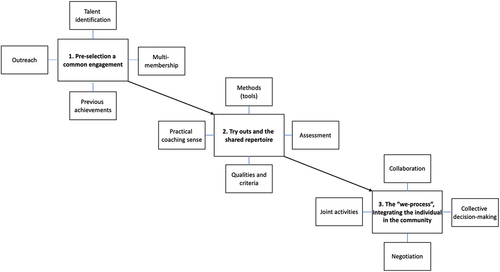

The analytical process followed the step-by-step-guide proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, p. 87) and began with a read-through of the transcribed interview-material. The second step involved generating initial codes in each transcript. During this initial coding, fragments of data were examined line-by-line and valuable aspects relating to the theoretical framework distinguished. Such aspects, established as codes, included: “engagement in practice”, “joint activities”, “shared repertoire”, “developing of ideas”, and “underlying assumptions”. Here, we also compared the codes in the different cases to identify similarities, differences, and patterns that emerged. In the third step, the codes were collated in specific sub-themes which was used to generate a thematic map, framed by and located within the study’s aims (step four) (see ). After consensus was reached between the two researchers, the themes were named and organised (step five). Lastly, quotes that could capture the essence of the point being demonstrated were selected for the findings-section (step six).

The analysis in this study was conducted by the authors. However, to ensure rigour and trustworthiness, colleagues acted as critical readers and discussed uncertainties.

Ethical considerations

The study follows the guidelines for research practice within social sciences formed by the Swedish Research Council (Citation2017) and was the subject of ethical guidance at the local Research Ethics Committee (DNR: 895–2023). Furthermore, prior to the interviews all individuals received an email with a detailed description of the study, ethical considerations, and a guide with subjects for discussion.

Findings

The analysis yielded three main themes all adhering to the practice of the admission in the six sports: (1) Pre-selection – a common engagement of identifying potential student athletes; (2) Try outs, and the shared repertoire, and (3); The “we process”, integrating the individual in the community. The themes, further developed below, depict the school sport teacher’s enactment of the admission, and how they operate as CoPs throughout the process.

Pre-selection – a common engagement of identifying potential student athletes

While CoPs emerge from a common engagement forged in participating in a practice together, our study shows that the CoPs pertains not only to the sites in which the main practice (of the admission) is enacted, but also to the different placing in other communities that CoP members share (Wenger, Citation1998).

Following this line of thought, in the six focus groups the common engagements throughout the admission process have a fundamental “locality” which starts with a pre-selection of student athletes. The teachers describe how they, individually and in groups, visit different youth-competitions on local, regional, and national levels (e.g. Swedish Junior championships) where they occasionally contact and communicate with young athletes, their parents, and club-coaches:

When the students are in 8th grade, in the spring, we start observing them. By then they have a whole year left, but we also look at the statistics, in the region and so on, that’s how they are included in our thoughts. (Track and field)

In these local contexts young athletes are occasionally “headhunted”:

The names that are interesting, we find their addresses […] We send a personal letter and invite them to our information day which is 14 days before the first application day. (Track and field)

Thereby, the admission process starts at least a year before pupils can formally apply to a SNESS, through the experience that the teachers have incorporated outside a school context, based on trajectories of participation arising from their overlapping of, or multi-membership in, different communities (Wenger, Citation1998).

While asked to reflect upon this pre-selection, the strategic identification of, and outreach to, young athletes whom the teachers view as “interesting”, the teachers underline that it is both required and necessary as part of the ongoing process of advancing the general knowledge of the enactments of the admission and in their position as “admitters”, enabling the teachers to scrutinise (interesting/talented) prospects. The teachers also highlight the fact that the outreach-process work both ways. Pupils who are interested in applying to a SNESS have the possibility to contact the schools, to visit the dorms and training facilities, or participate in open house activities. In canoeing, for example, interested pupils can be trainees for a week to get an impression of how it is to be a student athlete, opportunities which are described as well appreciated.

During the informal process of identifying and reaching out to interesting prospects, as an ongoing part of the teachers’ admission practice, the teachers explain that the formal admission process starts when applications to the schools are submitted by 9th grade pupils, during autumn semester. After the submission date has passed, the SSFs compile the applications, and communicate to the schools where the teachers review and sort them, both individually and in groups, occasionally together with colleagues from other schools from the same SSF. In general, the teachers in all six sport-specific focus groups maintain that they are familiar with the applicants, only on rare occasions does an “outsider” appear, i.e. an athlete the teachers have no prior information of.

After the review and sorting, the communities of teachers representing alpine skiing, canoeing, cross-country skiing and athletics emphasise that they invite all applying pupils to try-outs, while the teachers in swimming and orienteering invite applicants based on previous achievements, which includes results from competitions:

You can apply to SNESS, if you have achieved a certain number of FINA- points. FINA-points are based on world records. If you have reached a certain level of points, it is only a recommendation, you are able to apply. Unfortunately, we have had those who have applied, who did not have the points, these are filtered out quite quickly in the admissions process. (Swimming)

While asked about this pre-selection, based on previous achievements, the teachers in swimming acknowledge that everyone who swims knows what FINA points are, and thus it is convenient have a certain objective statistic to adhere to at the beginning of the admission process.

In summary, the teachers reported that the admission process starts a year before athletes can apply to SNESS. Initially, the process includes a common engagement in identifying, and reaching out to, potential student athletes. While this is a complicated process, a common perception among the teachers is that it is both required and necessary for advancing the general knowledge of the enactments of the admission and their position as “admitters”. The pre-selection enables the teachers to scrutinise (interesting/talented) prospects and constitutes preparation before the “real” admission process, the try-outs, begins. However, one may question whether it is the school sport teachers’ responsibility to carry out this pre-selection. The identification process partly relies on work tasks beyond the school context and thereby involvement in other communities (Wenger, Citation2000), raising concerns about fairness for applicants who follow the formal admission process and have not been identified earlier.

Try-outs, and the shared repertoire

One of Wenger’s (Citation1998) main characteristics of a CoP is the presence of a “shared repertoire”, which includes “routines, words, tools, ways of doing things, stories, gestures, symbols, genres, actions, or concepts that the community has produced or adopted in the course of its existence, and which have become part of its practice”. (p. 82–83). In the following, the repertoire is to be understood as the realm of the methods (tools) and techniques the school sport teachers use to assess the athletes throughout try-outs – in which the abilities of the athletes are tested.

In pursuing their mission to identify and select student athletes the teachers use a set of tools (methods) – physical aptitude tests, sport-specific training, interviews, social activities – and documents (matrices, forms, interview-guides) developed to support the admission procedure. Thus, the communities use a shared repertoire developed to help their practice (Wenger, Citation1998, Wenger et al., Citation2002). One of the most central instruments in this repertoire, utilised by all six communities, is physical aptitude tests, developed to assess aerobic capacity, strength, mobility, coordination, and balance.

While reflecting on the testing of applicants the teachers, in all sport-specific communities, emphasise that testing is an important part of the try-outs and that test results are a basis for assessment of applicants. However, it is not solely the test-results that are of interest, the teachers are equally captivated by, and put great emphasis on, how the applicants perform the tests. This subtle shift in approach to, and the renegotiation of, physical ability and its importance for sporting performance, is echoed in the shared language of belief in what the teachers stress they want to “see” in applicants:

They are not overjoyed when they run “the cooper”, but the fact is that it is a good test to see if they dare to get tired. (Athletics)

Yes, all these tests and everything that we see, combined, is the interesting thing, not each little test individually. When you get the whole picture and can get a sense of the athletes as a whole, we talk about character, but I also think it’s this practical coaching sense, what we see with our experience. (Athletics)

Thereby, physical aptitude tests are not only a method for assessment of physical abilities but a complementary method, in which teachers use their practical sense (Christensen, Citation2009, Lund and Olofsson, Citation2009) to discover or uncover psycho-social (intrinsic) features, mirroring character and motivation, such as whether the applicants try their best or “dare to get tired”.

In this context, the teachers express an awareness of biological differences – the relative age effect (Cobley, Baker, Wattie, & McKenna, Citation2009) – among the applicants.

For example, in the boys’16-class, the winner was 1.84 meters tall, weighed 80 kilos and had a beard. […] He is assessed in comparison to a chap who is 1.62 meters tall, weighing 52 kilos, it is difficult. (Cross-country skiing)

Recognition of physical attributes and abilities, height and body mass under great development, its benefits, and disadvantages, was emphasised across the interviews. The teachers in all focus groups express awareness of the potential pitfalls associated with focusing too much on just physical attributes and the fact that it is difficult to predict future success based on achievement and performance in the present.

While renegotiating physical ability and highlighting the importance of psycho-social (intrinsic) features, another view, supported by all teachers in the communities we interviewed, was the reflection of how they believed that successful student athletes take an active part in and responsibility for their own development. Therefore, they value highly an applicant who can understand and follow instructions, and stressed the importance of adaptiveness, willingness to learn, what one teacher referred to as “coachable” athletes:

I present these exercises, they can do these in the pool, some have never done the exercises before, which allows you to see quite quickly how … I call it coachable … How they can engage with instructions, when I want to make an adjustment to their technique, or if they want to learn something new. (Swimming)

An acknowledgement of the idea that psycho-social features can be discovered by studying how the applicants perform in sport specific situations, that is “how they run” or “how they swim”, as one alpine skiing teacher describes it: “What we assess the most is how they ski”.

Additionally, the teachers emphasise how the demands associated with pursuing both a sporting and academic career at the same time can be challenging. Therefore, interviews, and in some cases complementary questionnaires, are undertaken to provide the teachers with information on not only the applicant’s character and attitude, but also determination and “grit”:

We do the interviews to see pitfalls really, see this drive, this grit that we talked about earlier. (Athletics)

The teachers assess student ambition and whether the applicants will be able to combine school and sports, and all that it entails. While reflecting upon this, it was stressed that current student athletes are characterised as individuals with high academic standards. Study ambition, in general, indicate and determine, if the applicant will be able to manage, and cope with, the “dual career” – educational and sport obligations (Stambulova et al., Citation2015).

Notwithstanding the categorisation of individual sports, the consensus among the teachers in the six communities is that activities in SNESS are performed in an interactive community in which pupils eat, live (in dormitory’s), and practice together. Hence, the teachers stress the significance of assessment of applicants’ social skills, sometimes referred to as “life-skills”:

We train together to see how the athlete fits and works in the group … Does the athlete take energy or give energy to the group? (Athletics)

Life-skills make it easier to create time for school, create time for training, create time for social contacts, even outside the canoeing, with friends. (Canoeing)

When asked about how they assess life- and social skills the teachers highlight that the try-outs involve social activities, such as hiking, cooking, and team-building exercises. The activities are undertaken to assess cooperativeness and team spirit, i.e. do the applicants help, cheer, and motivate one another.

Prior to the final decision the teachers we interviewed reported that they try to collectively compile and summon the assessments of athletes, in matrixes, score sheets or specialised forms, which act as a supportive tool to overview the applicants’ strengths and limitations:

It is a form where we try to compile the things we see, or perceive, and actual tests they do. At the end of the form, there is an average result […]. A number is not everything, but it gives a decent overall picture, we think. (Canoeing)

We have always had a score sheet where we assess the skiing skills of all skiers who participate … we put points on the interviews, the fitness tests and so on. (Alpine skiing)

In these cases, as exemplified in one of the quotations above, teachers quantify the different assessment areas. The quantification includes objective scores, such as competition results, test results and grades, but also subjective scores via assessments of answers in interviews and teachers visual experience of how the applicants performed and presented themselves in tests, training, and social interactions. This quantification generates a numeric value which, when summed, constructs an overall picture of one applicant, and a ranking of all applicants. However, the teachers do not entirely rely on the summarised numeric ranking:

[…] you must walk away from this matrix again and reflect, what is it that we have really seen. You mix experience, feeling, the past, other things, together with the matrix. (Orienteering)

Thus, all the teachers we interviewed were clear that the numeric values have limitations. To “walk away” from the matrix can, therefore, be a metaphor for what several teachers, in all focus groups, repeated as equally important, that is to rely on their own “experience” and perceptions of the applicants.

In summary, all the teachers, in the sport-specific focus groups, were clear that the try-outs are a fundamental part of the admission process, and the common engagement in this practice, just as the pre-selection phase, is fundamental. The teachers in the six focus groups, in their different sports, have developed tools, manuals, and documents which are to be shared among the teachers and which construct a (tacit) understanding (Wenger et al., Citation2002). Throughout the try-outs the main assessments of the applicants are made, in which teachers refer to the five assessment areas (SSC, Citation2012, see ), through physical aptitude tests, sport-specific training, social activities and interviews. However, as has been illustrated in the preceding section, the teachers are (re-)negotiating physical ability, and have developed methods for assessing the applicants with the underlying focus to uncover socio-psychological (intrinsic) features. While doing so, the communities classify the students and thereby reproduce a discourse “of the professional athlete” in which certain embodied characteristics, such as motivation and competitiveness is seen as valuable (Brown, Citation2015a, p. 453). In this sense, Communities of practice tend to perpetuate established norms, values, and beliefs, which, due to their conservative nature, can impede innovation and restrict its progress (Wenger, Citation1998, Citation2000).

The ‘we process’, integrating the individual in the community

While the teachers could not recall how their methods working with try outs were developed, they were, at the same time strongly established and supported by the communities in which the individual teachers, with sport-specific experience and knowledge, were integrated into the communities. In this study, the teachers’ common engagement and shared repertoire (methods, tools and instruments) to assess applicants, are expressed through their interactions, and ongoing discussions throughout the admission process. The teachers share a concern for their enactment of the admission in which they engage in joint activities, help each other, and share information, below this is framed as the “we-process”, in which the individual is integrated in the communities of decision-making.

Throughout the focus group interviews the teachers express humbleness and concerns regarding the challenges of selecting the “right” applicants:

It’s an impossible task, but I have the task. (Orienteering)

Guess, that’s what you must do, a guess by an expert I would say. (Cross-country skiing)

The selection of student athletes is described as “impossible”, and a “guess by an expert”. However, these statements, and their innate individuality, are somewhat misleading. Throughout the focus group interviews the teachers describe the enactment of the admission as a “we-process”, characterised by togetherness, and collaboration:

There is a big difference over these 20 years, it has been more and more collaboration, it is a driving force in the system that we work together. (Cross-country skiing)

All three of us participate in all the activities, and we participate in the interviews, then the three of us sit together and do the ranking. (Orienteering)

This collaboration, expressed through statements such as “we work together”, is particularly important for the final decision. The teachers rely on their professional knowledge and practical reasoning (Christensen, Citation2009, Cushion & Jones, Citation2006, Lund & Söderström, Citation2017, Roberts et al., Citation2019, Williams & Reilly, Citation2000) when assessing applicants, but they do it collectively. Therefore, the final decision is based on several teachers’ perceptions of every applicant, some of which the colleagues view as indisputable:

It is always easy the first five, but the one who should have the sixth or seventh spot is always the most difficult. (Orienteering)

While reflecting upon the ones who are more uncertain, the teachers, in general, emphasise that their views can differentiate. To resolve issues, they undertake a kind of argumentative discussion, where each teacher explains and defends their favoured applicant over another, thereby, integrating the individual in the community:

It’s good that we think differently when we sit (and discuss), all the coaches are there, there are four or five of us sitting (discussing) and then it’s … I’ve seen some things and someone has seen other things…Then we sit for a while and… kind of argue for our case, for what we have seen. We try to get an overall picture… Then we rank them a little bit, that is, we don’t need to think about these two, they are already through, we agree on them … Then it’s often that we, ok now we’ll let it rest, then we’ll come back tomorrow or in two days. (Athletics)

How balanced and flexible the discussion is appeared to be dependent on the teachers. However, it is not expressly one teacher that has the final call, rather, a common perception is that it is a collective decision in a horizontal organisational structure without (visible) hierarchal levels. The teachers have developed relationships, and a climate of openness, that enable them to learn from each other and care about their different standpoints (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, Citation2015) The relationships are evident in the teachers’ agreement on the final selection of applicants.

The collectiveness in this process is described as essential since, occasionally, the teachers receive both criticism and appeals from rejected applicants, parents, or club coaches:

They call and say they think it should have been the other way around. That is why it is important when we make choices, that we are careful and that we really agree. (Athletics)

Because of the increasing number of appeals, the teachers have started to reflect upon how innovation might be applied to the admission processes. It is suggested that an objective rationale, “ink on paper” or “hard data” for justifying the selections are preferable when communicating their selections to the public, in order to, as one teacher put it, “have something to fall back on”. The teachers, in cross-country skiing, athletics and swimming, underline this fact by advocating that results in youth-competitions and rankings cannot be disregarded in the admission process since they have strong intrinsic values in their specific sporting communities. The frontrunners are viewed as talents, and therefore, the teachers stress, there is pressure and an implicit imperative, from the “sporting community” to admit these to a SNESS. Thus, these teachers express a concern that their degree of legitimacy and authority is questioned, and their professional knowledge devalued, being viewed as inferior to explicit, “objective” dimensions. However, they emphasise, and are firm in their belief, learned through experience, that intrinsic values, “qualitative” features, i.e. social skills, ambition etc. are equally important as the “hard data”. It is acknowledged that the teachers “find” these attributes through the wide-ranging prolonged admission process.

As noted in this section, the decision making in the admission process is a collective and systemised group focused (we) process (Wenger, Citation1998). Throughout the process discussions are held, although, even when communication has been established, the individual feelings of an “impossible task” of choosing the “right” athletes can be experienced as overwhelming, and not made easier by having one’s ability to choose the “right” applicant from all applicants’ devalued. However, while capturing insights of how teachers in “Communities of Practice” reflect on their enactments, the admission process is the result of the belief systems dispositions and actions of individual teachers within the communities, shared through a collaborative culture (Wenger, Citation1998). In the following section we will further elaborate upon the findings.

Discussion

While sport schools are designed exclusively for those identified as talented, talent identification itself has been recognised as a complex task (Bailey & Morley, Citation2006, Roberts et al., Citation2019). When questioned about their talent identification methods, coaches frequently rely on a “gut feeling” (Johansson & Fahlén, Citation2017, p. 475) or their “eye for talent” (Christensen, Citation2009, p. 379) to discern familiar patterns of characteristics that suggest future high-level performance. As a result, coaches develop a “practical sense” and a preference for certain perceived traits of a talented athlete, shaped by their previous experiences with talent identification (Lund & Söderström, Citation2017, p. 252, see also Christensen, Citation2009). Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrates that the admission process in SNESS incorporates a “practical sense”, primarily gained outside the school context, particularly through coaching experiences.

However, our study also reveals that the practical sense of one teacher is developed and integrated in discussions with other teachers in a CoP in which the teachers are closely knit together. Consequently, throughout the admission process the teachers accumulate their joint experience, expert knowledge, through conversation and interaction (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, Wenger, Citation1998). Following this line of thought, all six focus groups displayed comparable CoP characteristics (Wenger, Citation1998), and in general, as shown in the findings above, the teachers work on similar problems, in cohesive groups (our sample of teachers worked in fairly small units of three to five) sharing knowledge, tasks, tools, activities and a physical location. The teachers’ common engagement was the central enterprise of their collective action (Koliba & Gajda, Citation2009) and this engagement was apparent through the descriptions of the collegial “we-process”, characterised by collaboration, togetherness, and supportiveness.

Moreover, in all the six focus groups, teachers described how they employed a set of tools (methods) – physical aptitude tests, sport specific training, interviews, social activities – and documents (matrices, forms, interview-guides) developed to support the practice of the admission. These tools, the “shared repertoire”, included formal (as illustrated above), and also informal communication to guide decision-making (Wenger, Citation1998, p. 82). The latter was expressed throughout the interviews where the teachers shared language while discussing preferable attributes of an applicant (such as “character”), shared tacit conventions while assessing the applicants, shared embodied understandings of how the applicants are supposed to look when they run, ski, swim and so forth, and underlying assumptions of indisputable “talents”. In summary, the teachers share mutual, sport-specific, world views when enacting the admission process (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991, Wenger, Citation1998), and are thereby transforming into what Christensen (Citation2009, p. 377) refers to as “arbiters of taste” defining the qualities expected of a student athlete.

Our findings align with the findings of Brown (Citation2015a), that athletes in school sport programmes are categorised by abilities associated with a highly rated professional athlete. As a result, school sport teachers, in their CoPs run the risk of perpetuating a reproduced discourse “of the professional athlete” in which certain embodied characteristics, such as motivation and competitiveness, are seen as valuable (Brown, Citation2015a, p. 453). That in mind, while the teachers are expected to prioritise applicants who have the best potential to utilise the school sports programmes (SFS Citation2010:2039, Chapter 5, Section 26) they face difficulty in not adhering to the sports movements’ requests, that the programmes are intended for “talented” individuals with the necessary skills to achieve national or international elite status as adults (SSC, Citation2012, p. 1). This creates a challenging task for teachers, especially since the demands and requirements of the sports field often seems to outweigh those of the school (Brown, Citation2015a, Ferry, Citation2016).

As noted in this study, the CoPs had many similar characteristics. However, drawing upon CoP theory could lead to a further question – how does the enactment of the admission process differ between the CoPs, and for example, what aspects of those differences are determined by macro factors, such as organisation and structure of each sport, and what aspects are determined by micro factors, such as local social interaction? (Hodkinson & Hodkinson, Citation2004a). In our focus groups interviews inherent sport-specific culture, organisation, and structure, of the “major” sports (e.g. cross-country skiing, athletics) seems to influence the enactment of admission to a greater extent than in the “minor” sports (e.g. orienteering, canoeing). For example, the teachers in cross-country skiing, athletics, and swimming, emphasised that competitions, outside a school context, could not be disregarded in the admission process since they have strong intrinsic values in their respective sporting communities. Thereby, macro factors influence the enactment and innovation in these CoPs. Nevertheless, the differing characteristics between the CoPs could not be accounted for by wider organisational factors, after all, the CoPs are subject to broadly the same regulations (SFS Citation2010:2039 and policy documents (SSC, Citation2012). Nor can such differences be explained entirely through the individual attitudes of the teachers who belonged to the CoPs, though, as the findings imply, the individuals were integral to each other in a “we process”, and a horizontal organisational structure. Although deeper examination is needed to address differences between CoPs, for example, linking the practices of individuals, such as the school sport teachers belonging to over-lapping CoPs – the teaching profession, the sport-specific expert role, the school where they work etc (Ferry, Citation2016, Hedberg, Citation2014). The multi-membership of different communities, and the tension between high-performance sport and schooling (Brown, Citation2015a, Brown, Citation2015b), is sometimes a key dilemma for the individual teacher (Wenger, Citation1998), and it might be argued that this provides an opportunity to strengthen the communication and coordination between the teachers, the schools, the clubs and the SSFs regarding the admission process (c.f. Bjørndal & Gjesdal, Citation2020).

While the concept “Community of Practice” provided a useful framework to analyse the practice of the admission process, such a concept also aims to generate knowledge about relations, how sociality among practitioners impacts the way in which practices are learned, enacted, and innovated. In critique, the term CoP has been acknowledged as ambiguous, for example in relation to scale and applicability (Hodkinson & Hodkinson, Citation2004a). Therefore, it is important to take into account that the findings in this study are limited to the focus groups (n = 6), and the process as described by the teachers (n = 18) interviewed. Nevertheless, the findings can serve as a foundation for further research that explores admission processes in sports schools.

As the focus on efficient talent identification and development continues to grow (e.g. Green, Citation2003, Martindale, Collins & Daubney, Citation2005, Roberts et al., Citation2019), the development of school sport programmes, in which the blurring of boundaries between education and sports are evident (Brown, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Hedberg, Citation2014), it is important to gain a deeper understanding of the complex admission process. Such research could explore how the admission process unfolds. For instance, it could assess the progression of selected athletes throughout their school sport programme, investigating whether they successfully graduate. Additionally, researchers could explore whether the selected athletes demonstrate competitive results, potentially surpassing the performance of those who were not selected. Furthermore, it would be valuable to examine alternative outcomes that may arise from the admission process. By addressing these questions, including studies with larger sample sizes and a wider range of sports, a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of the admission process can be obtained.

Concluding remarks

To summarise, the findings in this study indicate that the admission process in SNESS is time-consuming and complex. The school sports teachers adhere to policy documents (SSC, Citation2012), develop methods to help in the practice, and use their combined cumulative experience and their professional knowledge to identify and select student athletes.

Unarguably, the admission process, as described by the participants in this study, constitutes subjective assessments of young athletes influenced by the school sports teachers’ underlying assumptions of what qualities, e.g. character, willingness to learn, a student athlete should have. In other words, the teachers have developed, as has been demonstrated before, a “taste” for talent (Christensen, Citation2009, Lund & Söderström, Citation2017) and are reproducing sport specific discourses of embodied characteristics such as motivation and competitiveness (Brown, Citation2015a).

Although, it can be argued that by working together the teachers in the sport-specific CoPs “deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” (Wenger et al., Citation2002, p. 4). Therefore, the way one teacher in this study expressed it, “a guess by an expert”, is misleading. It is rather school sports teachers with professional, expert, knowledge in their specific sport, who reinforce the admission process, the assessments of athletes, by ongoing interactions which generate a joint cumulative experience and knowledge. Thereby the findings in this study are in line with the idea of Wenger et al. (Citation2002) that to develop expertise, practitioners need opportunities to engage with others who face similar situations and problems: “The knowledge of expert is an accumulation of experience – a kind of ‘residue’ of their actions, thinking and conversations – that remains a dynamic part of their ongoing experience” (p. 9). Following this line of thought, the findings strengthen the work of scholars arguing that practitioners on the field perceive conversations and reflections with colleagues, grounded in everyday issues, as being vital in their development of understanding and learning their own practices (Berntsen & Kristiansen, Citation2019; Cassidy & Rossi, Citation2006; Cassidy, Potrac, & McKenzie, Citation2006; Culver & Trudel, Citation2006; Jones, Morgan, & Harris, Citation2012; Whitaker & Scott, Citation2019).

On a final note, arguably a plausible conclusion, due to their conservative character CoPs can hinder innovation and limit its development by producing and re-producing everyday activity, values and beliefs, developing a passing on of “tricks of the trade” (Cassidy & Rossi, Citation2006, p. 244). In short, the CoPs are likely to advocate a course of action in accordance with what has always been done (Wenger, Citation1998). As Wenger (Citation2000) advocates, CoPs are born out of learning, but can learn not to learn; “They are the cradles of the human spirit, but they can also be its cages”. (p. 230). This in mind, to avoid path dependency, reproducing the inherent, underlying, mutual, assumptions and coherent views of talent in the admission process, it is essential that members of the CoPs continuously renew, renegotiate, and reflect upon their practice. Regularly meetings with groups from other schools and sports can be one effective approach to achieve this. It allows teacher groups to learn from each other and challenge assumptions that are often taken for granted.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, we would like to thank the school sports teachers who kindly gave their time to participate and share their knowledge on the admission process. Secondly, this study draws on data from a larger research project initiated and funded by the Swedish Sports Confederation. Thereby, we would like to thank the Swedish Sports Confederation for initiating the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersson, F. (2023). Sport schools in Europe: a scoping study of research articles (1999–2022). Sport in Society, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2023.2273856

- Bailey, R., & Morley, D. (2006). Towards a model of talent development in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 11(3), 211–230. doi:10.1080/13573320600813366

- Berntsen, H., & Kristiansen, E. (2020). Perceptions of need-support when “having fun” meets “working hard” mentalities in the elite sport school context. Sports Coaching Review, 9(1), 1–23. doi:10.1080/21640629.2018.1525862

- Bjørndal, C. T., & Gjesdal, S. (2020). The role of sport school programmes in athlete development in Norwegian handball and football. European Journal for Sport and Society, 17(4), 374–396. doi:10.1080/16138171.2020.1792131

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, S. (2015a). Moving elite athletes forward: Examining the status of secondary school elite athlete programmes and available post-school options. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(4), 442–458. doi:10.1080/17408989.2014.882890

- Brown, S. (2015b). Reconceptualising elite athlete programmes: ‘undoing’ the politics of labelling in health and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(2), 228–240. doi:10.1080/13573322.2012.753048

- Brown, S. (2016). Learning to be a ‘goody- goody’: Ethics and performativity in high school elite athlete programmes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(8), 957–974. doi:10.1177/1012690215571145

- Burgess-Limerick, T., & Burgess-Limerick, R. (1998). Conversational interviews and multiple-case research in psychology. Australian Journal of Psychology, 50(2), 63–70. doi:10.1080/00049539808257535

- Cassidy, T., Potrac, P., & McKenzie, A. (2006). Evaluating and reflecting upon a coach education initiative: The CoDe of rugby. The Sport Psychologist, 20(2), 145–161. doi:10.1123/tsp.20.2.145

- Cassidy, T., & Rossi, T. (2006). Situating learning: (re)examining the notion of apprenticeship in coach education. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching Volume, 1(3), 235–246. doi:10.1260/174795406778604591

- Christensen, M. K. (2009). An eye for talent”: Talent identification and the “practical sense” of top-level soccer coaches. Sociology of Sport Journal, 2009(26), 365–382. doi:10.1123/ssj.26.3.365

- Cobley, S., Baker, J., Wattie, N., & McKenna, J. (2009). Annual age-grouping and athlete development. A meta-analytical review of relative age effects in sport. Sports Medicine, 39(3), 235–256. doi:10.2165/00007256-200939030-00005

- Culver, D. M., & Trudel, P. (2006). Cultivating coaches’ communities of practice – developing the potential for learning through interactions. In R. L. Jones (Ed.), The sports coach as educator (pp. 97–112). London: Routledge.

- Cushion, C., & Jones, R. L. (2006). Power, discourse, and symbolic violence in professional youth soccer: The case of Albion Football club. Sociology of Sport Journal, 2006(23), 142–161. doi:10.1123/ssj.23.2.142

- De Bosscher, V., De Knop, P., & Vertongen, J. (2016). A multidimensional approach to evaluate the policy effectiveness of elite sport schools in Flanders. Sport in Society, 19(10), 1596–1621. doi:10.1080/17430437.2016.1159196

- Emrich, E., Frohlich, M., Klein, M., & Pitsch, W. (2009). Evaluation of the elite schools of sport: Empirical findings from an individual and collective point of view. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 44(2–3), 151–171. doi:10.1177/1012690209104797

- Fahlström, Per Göran., Andersson, Filip., Gerrevall, Per., Hedberg, Marie, & Linnér, Susanne. (2023). Våra framtida stjärnor – Om urval och antagning till idrottsgymnasier [Our future stars – Regarding selection and admission to Swedish national elite sport schools]. Stockholm: Riksidrottsförbundet.

- Ferry, M. (2016). Teachers in school sports: Between the fields of education and sport? Sport, Education and Society, 21(6), 907–923. doi:10.1080/13573322.2014.969228

- Ferry, M., & Lund, S. (2018). Pupils in upper secondary school sports: Choices based on what? Sport, Education and Society, 23(3), 270–282. doi:10.1080/13573322.2016.1179181

- Ferry, M., Meckbach, J., & Larsson, H. (2013). School sport in Sweden: What is it, and how did it come to be? Sport in Society, 16(6), 805–818. doi:10.1080/17430437.2012.753530

- Green, M. (2003). Changing policy priorities for sport in England: The emergence of elite sport development as a key policy concern. Leisure Studies, 23(4), 365–385. doi:10.1080/0261436042000231646

- Hedberg, M. (2014). Idrotten sätter agendan - En studie av Riksidrottsgymnasietränares handlande utifrån sitt dubbla uppdrag [Sport sets the agenda - A study of the actions of school sports teachers, based on their dual mission] [ Doctoral dissertation. University of Gothenburg, University of Gothenburg, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- Hodkinson, P., & Hodkinson, H. (2003). Individuals, communities of practice and the policy context: School teachers’ learning in their workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 25(1), 3–21. doi:10.1080/01580370309284

- Hodkinson, P., & Hodkinson, H. (2004a). A constructive critique of communities of practice: Moving beyond Lave and Wenger. OVAL Research Working Paper 04–02. Leeds, UK: Lifelong Learning Institute, University of Leeds, UK.

- Hodkinson, P., & Hodkinson, H. (2004b). Rethinking the concept of community of practice in relation to schoolteachers’ workplace learning. International Journal of Training and Development, 8(1), 21–31. doi:10.1111/j.1360-3736.2004.00193.x

- Johansson, A., & Fahlén, J. (2017). Simply the best, better than all the rest? Validity issues in selections in elite sport. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(4), 470–480. doi:10.1177/1747954117718020

- Jones, R., Morgan, K., & Harris, K. (2012). Developing coaching pedagogy: Seeking a better integration of theory and practice. Sport, Education and Society, 17(3), 313–329. doi:10.1080/13573322.2011.608936

- Koliba, C., & Gajda, R. (2009). “Communities of practice” as an analytical construct: Implications for theory and practice. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(2), 97–135. doi:10.1080/01900690802385192

- Kristiansen, E., & Houlihan, B. (2017). Developing young athletes: The role of private sport schools in the Norwegian sport system. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 52(4), 447–469. doi:10.1177/1012690215607082

- Kristiansen, E, and Stensrud, T. (2020). Talent development in a longitudinal perspective: Elite female handball players within a sport school system. Translational Sports Medicine, 3(4), 364–373. doi: 10.1002/tsm2.143

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning, legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lund, S., & Olofsson, E. (2009). Vem är idrottseleven? Idrottsprofilerad utbildning och selektion [Who is the student athlete? Sport schools and selection.]. SVEBI:s årsbok, 125–150.

- Lund, S., & Söderström, T. (2017). To see or not to see: Talent identification in the Swedish Football Association. Sociology of Sport Journal, 34(3), 248–258. doi:10.1123/ssj.2016-0144

- Martindale, R., Collins, D., & Daubney, J. (2005). Talent development: A guide for practice and research within sport. Quest, 57(4), 353–375. doi:10.1080/00336297.2005.10491862

- Morris, R., Cartigny, E., Ryba, T., Wylleman, P., Henriksen, K. … Cecić Erpič, S. (2021). A taxonomy of dual career development environments in European countries. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(1), 134–151. doi:10.1080/16184742.2020.1725778

- Peterson, T. (2008). When the field of sport crosses the field of physical education. Educare, 3(3), 83–97.

- Peterson, T., & Wollmer, P. (2019). Vilka elever antas till en idrottsskola? [Which students are admitted to a sports school?] idrottsforum.org, 2019-09-10.

- Pot, N., & Van Hilvoorde, I. (2013). Generalizing the effects of school sports: Comparing the cultural contexts of school sports in the Netherlands and the USA. Sport in Society, 16(9), 1164–1175. doi:10.1080/17430437.2013.790894

- Radtke, S., & Coalter, F. (2007). Sport schools: An international review. Report to the Scottish institute of sport foundation. Stirling: University of Stirling, Department of Sports Studies.

- Roberts, A., Greenwood, D., Stanleya, M., Humberstone, C., Iredalea, F., & Raynora, A. (2019). Coach knowledge in talent identification: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2019(22), 1163–1172. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2019.05.008

- Saarinen, M., Ryba, T. V., Ronkainen, N. J., Rintala, H., & Aunola, K. (2020). ‘I was excited to train, so I didn’t have problems with the coach’: Dual career athletes’ experiences of (dis)empowering motivational climates. Sport in Society, 23(4), 629–644. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1669322

- Skrubbeltrang, L., David, K., Nielsen, J. C., & Olesen, J. O. (2020). Reproduction and opportunity: A study of dual career, aspirations and elite sports in Danish SportsClasses. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 55(1), 38–59. doi:10.1177/1012690218789037

- Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Stambulova, N., Engström, C., Franck, A., Linnér, L., & Lindahl, K. (2015). Searching for an optimal balance: Dual career experiences of Swedish adolescent athletes. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 21, 4–14. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.009

- Stokvis, R. (2009). Social function of high school athletics in the United States: A historical and comparative analysis. Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics, 12(9), 1236–1249. doi:10.1080/17430430903137936

- The Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS) (2010:2039).Gymnasieförordningen [the upper secondary school ordinance]. Stockholm: Ministry of Education and Research.

- Swedish research council. (2017). God forskningsed [good research honour]. Stockholm: Swedish research council.

- Swedish Sports Confederation. (2012). Riktlinjer för urval av elever [Guidelines for the selection of students]. Stockholm: Swedish Sports Confederation.

- Swedish Sports Confederation. (2023). Elitidrott på gymnasiet – RIG och NIU [Elite sports in upper secondary education – RIG and NIU]. Stockholm: Swedish Sports Confederation.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E. (2000). Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization, 7(2), 225–246. doi:10.1177/135050840072002

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, M. W. 2002. Cultivating communities of practice. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard business school press.

- Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. https://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/07-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf

- Whitaker, L., & Scott, M. (2019). Setting up and evaluating a community of practice for sport coaches. Applied Coaching Research Journal, 3, 24–33.

- Williams, A. M., & Reilly, T. (2000). Talent identification and development in soccer. Journal of Sports Sciences, 18(9), 737–750. doi:10.1080/02640410050120113

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.