ABSTRACT

Background: Patients with exhaustion syndrome (ES), the clinical equivalent of long-lasting burnout, and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) report overlapping symptoms such as exhaustion, fatigue, cognitive deficits and intolerance to stressors. Additionally, patients with CFS experience somatic symptoms, including bodily pain, immune symptoms, and post-exertional malaise. Clinically, patients with CFS often have reduced functioning as compared to ES, but studies comparing quality of life have not been reported.

Purpose: To compare quality of life between patients with ES (n = 31), CFS (n = 38) and healthy controls (HC) (n = 30) by using the Short Form 36 questionnaire (SF-36) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

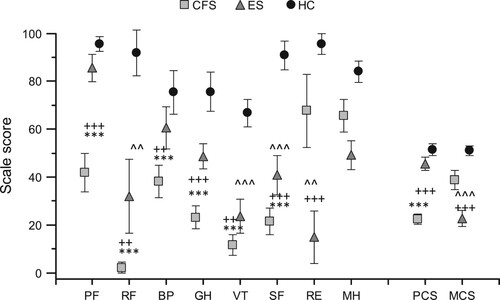

Results: Patients with CFS scored lower in all quality of life dimensions on the SF-36 as compared to the ES and HC groups, except for the role emotional and mental health subscales. Patients with ES scored lower on the subscales of physical role, vitality, social functioning and role emotional as compared to HC. Physical Component Summary scores were lower in CFS, while the Mental Component Summary scores were lower in ES as compared to CFS and HC. Higher scores for depression symptoms on the HADS and group membership explained the major part of variance.

Conclusion: Findings indicated both similarities and differences on the SF-36 in patients with ES as compared to CFS. Both groups showed a substantial reduction in quality of life as compared to controls. Perhaps surprisingly, mental health was less affected in patients with CFS. Emotional status appears to be important in affecting health-related quality of life in both illnesses.

Introduction

Both stress-related exhaustion syndrome (ES) and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) are characterized by fatigue and physical and mental exhaustion, which are worsened by effort or stress. The Swedish Board of Health and Welfare introduced diagnostic criteria for ES, the clinical equivalent of burnout, in 2003. In 2010 it was incorporated into the Swedish version of the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-SE code F43.8A) [Citation1]. Different criteria for CFS have been developed during the last 30 years. The ICD-10-SE code for CFS has the synonymous names of ‘post-viral fatigue, chronic fatigue syndrome, myalgic encephalomyelitis’ (G93.3). In a systematic review, Brurberg et al (2014) reported 20 case definitions of CFS [Citation2].

There are striking symptom similarities between ES and CFS, at least when the Canadian criteria for CFS [Citation3] are applied. In both conditions, there is chronic disabling fatigue accompanied by sleep disturbances, pain, and difficulties with memory and concentration, as well as significant physical and mental fatigue with a lack of endurance. ES is, however, considered a stress-related psychiatric disorder caused by long-term psychological stress that is often, but not exclusively, work-related (see [Citation1]). Cross-sectional data indicate that ES is related to high work demands in conjunction with low levels of influence or control [Citation4]. CFS, on the other hand, is considered an organic multi-systemic illness with unknown cause [Citation3]. Approximately 75% of patients with CFS report a relationship between infection(s) and onset of symptoms [Citation5]. Prognosis is very different for ES and CFS, with the latter having a particularly worse prognosis.

Table 1. Comparison of set of criteria for exhaustion syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Both ES and CFS are associated with sleep disturbances [Citation6] and cognitive deficits in attention, working memory, and long-term memory [Citation7,Citation8]. There is no consensus on how best to treat either ES [Citation9] or CFS [Citation10]. In both conditions, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and multidisciplinary rehabilitation are the usual treatment approaches [Citation9,Citation11–14]. In a randomized control trial for ES comparing Qigong alone (gentle movements, body awareness, balance and coordination, breathing, relaxation and mindfulness) or in combination with CBT, 75% of patients in both treatment arms had returned to work at the three-year follow-up [Citation15].

In CFS, by contrast, few adult patients recover. In one study following 50 CFS patients, none showed symptom improvement after one year [Citation16], and as few as 18.3% were recovered 6 months after receiving CBT [Citation17]. While patients with ES seem at least to tolerate CBT, few patients with CFS substantially recover with CBT [Citation18], and some critics argue that this treatment can even worsen symptoms [Citation19]. At the same time, tertiary interventions seems to facilitate ES patients` return to work [Citation20], whereas in CFS patients, multidisciplinary rehabilitation was more effective than CBT in improving self-scored fatigue, [Citation14]. Given these clinical outcome differences, it is of paramount importance to delineate whether a patient suffers from ES or CFS in order to offer appropriate treatment and medical care. Studies comparing the illnesses and what parameters contribute to appropriate differential diagnostics decisions are therefore of importance.

Introducing ES, the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare argued the need for research comparing ES and CFS [Citation1]. However, very few studies comparing ES to CFS exist. Recently we have reported on similarities and differences in emotional parameters between patients with ES and CFS [Citation21]. Health-related quality of life has, however, not been compared between these groups. Both ES and CFS lead to a substantially reduced activity levels and a high degree of sick leave, whereas the symptoms can have detrimental effects on quality of life [Citation22,Citation23]. Low scores for physical functioning (PF), vitality (VT) and general health (GH) have been shown to be the most striking findings on the SF-36 for CFS [Citation24]. In a study of ES, all parameters of quality of life were lower compared to people working full time [Citation22]. In a literature review carried out by Jason et al. [Citation25], 17 studies comparing CFS to other illnesses and diseases were identified, although ES was not one of them. In all 17 studies, patients with CFS had lower quality of life, compared to healthy controls, psychiatric populations and medical disorders such as multiple sclerosis.

The SF-36 instrument captures reduced functioning and lower quality of life on several subscales. Lower scores on the SF-36 vitality subscale (VT) indicates that the patient has lost his/her energy, and feels worn out and tired. Reductions on the social functioning subscale (SF) signifies interference with normal social activities with family, friends, neighbours or groups. Lower Role-Physical subscale (RF) scores often means that a patient has to limit work or other activities, and accomplishes less than might be desirable. In both ES and CFS a lower quality of life, significant impairments in energy, and reduced involvement in social activities and life accomplishments are expected [Citation22].

The aim of this article was to compare the health-related quality of life between patients with ES, CFS and healthy controls. Taking earlier research into consideration, we hypothesized that (1) patients with both CFS and ES would report lower quality of life as compared to controls and (2) according to our recent findings [Citation21], we expected that emotional status/mood would have an impact on health-related quality of life.

Methods

Participants

Participants were consecutively recruited from the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Danderyd University Hospital, from either the ME/CFS Rehabilitation Unit or the Stress Rehabilitation Unit during 2013–2015. Patients met a physician specialist in rehabilitation or pain medicine or neurology and a psychologist for 90 minutes each visit. They were screened for other medical or psychiatric disorders that could explain their fatigue and accompanying symptoms. In addition, patients underwent laboratory tests to exclude those individuals with ongoing inflammation, infection, metabolic and immunological disorders and/or other pathological conditions either at the ME/CFS rehabilitation unit or in the primary health care before referrals.

CFS patients were diagnosed according to the Canadian criteria [Citation3]. Canadian criteria in comparison to Fukuda or CDC criteria [Citation26] requires a substantially reduced activity level as compared to premorbid level and includes severely affected patients. In 2013, the patient organisation and decision makers in Sweden suggested use of the Canadian criteria instead of CDC-Fukuda for diagnosis of CFS. A short version of both criteria is summarized in . As specified, patients with ES should have: (A) Physical and mental symptoms of exhaustion for at least two weeks. The symptoms have developed due to one or more identifiable stressors presented for at least six months. (B) The clinical picture is dominated by markedly reduced mental energy, as manifested by reduced initiative, lack of endurance, or increased time needed for recovery after mental effort. (C) At least four of the following symptoms have been present, nearly every day, during the same 2-week period: (1) concentration difficulties or impaired memory; (2) markedly reduced capacity to tolerate demands or to work under time pressure; (3) emotional instability or irritability; (4) sleep disturbances; (5) marked fatigability or physical weakness; (6) physical symptoms such as aches and pains, palpitations, gastrointestinal problems, vertigo or increased sensitivity to sound. (D) The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairments in occupational, social or other activities and participations in daily life. (E) The symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g. a drug of abuse, a medication) or a physical illnesses or injuries (e.g. hypothyroidism, diabetes, infectious disease).

To fulfil the Canadian criteria (3) for CFS as utilized in this study, the symptoms listed below should be present for at least six months in combination with a substantially reduced activity level as compared to premorbid level. The required symptoms are: (A) post-exertional malaise, with hallmark features of: (A1) physical and⁄ or cognitive fatigability; (A2) post-exertional symptom exacerbation; (A3) prolonged exertion recovery period, usually taking 24 h or longer. (B) Physical and mental fatigue. (C) Sleep Dysfunction. (D) Pain. (E) Neurological/Cognitive Manifestations requiring two or more of these symptoms: impairment of concentration and short-term memory consolidation, difficulty with information processing, and/or overload phenomena (cognitive, sensory), e.g. photophobia and hypersensitivity to noise, etc. (F) At least one symptom from two of the following categories: (F1) autonomic manifestations, i.e. orthostatic intolerance such as neurally mediated hypotension (NMH), postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), sweating episodes etc.); (F2) neuroendocrine manifestations, i.e. loss of thermostatic instability that may manifest as subnormal body temperature and marked diurnal fluctuation, recurrent feelings of feverishness and cold extremities; (F3) immune manifestations, i.e. tender lymph nodes, recurrent sore throat, recurrent flu-like symptoms, etc.

In accordance with the diagnostic criteria for ES and CFS, both medical and psychiatric comorbidities were accepted as far as they were treated and not judged to be the primary explaining factor of symptoms presented. The healthy control group was recruited by using a convenience sample of family, friends and co-workers. Healthy controls did not have had a current or previous diagnosis of ES or CFS.

All groups answered questionnaires by sending in their answers in a prepaid envelope. All participants provided their informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm, Sweden (Registration number: 2012/1790-31 and 2015/908-32). Another part of the data from the same cohort has previously been reported [Citation21].

Disability was defined by a legal degree of sick leave or disability pension, established by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, and reported by a participant in a questionnaire and/or during clinical investigation. One participant in the CFS group was on voluntary early retirement pension, due to sickness. This participant was coded as having full-time disability pension. The duration of symptoms was extracted from clinical recordings. For ES, the duration of symptoms was calculated between the date of sick leave mentioned in recordings and the date of the first visit to the Stress Rehabilitation Unit at Danderyd University Hospital. For CFS, duration was based on time between the start of fatigue symptoms and the date of the first visit to the ME/CFS Rehabilitation Unit at Danderyd University Hospital. CFS patients might have several periods of sick leave or even be discharged from the sick leave compensation system due to Swedish social insurance regulations. Furthermore, CFS patients might have been on partial sick leave or received partial disability pension for many years, whereas ES patients had only one period of sick leave, which was related to the start of the symptoms and the visit to the specialist clinic.

Measurements

The Short Form 36 (SF-36). The 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a validated and widely used questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [Citation27]. The 36 items in the questionnaire are grouped into eight subscale scores: physical functioning (PF), role limitations caused by physical problems (RF), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), energy/vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role limitations caused by emotional problems (RE) and mental health (MH). The subscale scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating a better HRQoL. Moreover, the physical scale scores and mental scale scores can be separately grouped together, creating two additional subscales: Physical Component Summary and the Mental Component Summary scores.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS assesses symptoms of anxiety and depression. The two subscales of the HADS are represented by seven items each (e.g. ‘I get sudden feelings of panic.’). The answers range from 0 ‘not at all’ to 3 ‘very often indeed.’ The maximum score is 21 for each factor. A score of 10 or more indicates that depression or an anxiety disorder probably exists. Good internal consistencies for both scale factors have been demonstrated for the Swedish version of the HADS, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 for the anxiety subscale and 0.82 for the depressive subscale [Citation28].

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS (version 23.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Baseline characteristics of nominal data (gender, country of birth, education and disability) were compared using the chi-square test and t-test for independent samples for duration of symptoms. An ANOVA was used to compare age and SF-36 scores between the groups. Variables showing significant differences between the groups were chosen for full factorial MANCOVA. SF-36 domains were chosen as dependent variables. Group, gender, scores on the HADS (depression and anxiety) and duration of symptoms were chosen as covariates. The accuracy of multiple regression analysis was checked by distribution of residuals with satisfactory outcome.

Results

Clinical parameters of the groups

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in . The majority of participants were middle-aged, highly educated females born in Sweden. There was a significant difference in duration of symptoms between ES and CFS, with the latter having a longer history of disease (). A chi-square test revealed differences in gender between the groups, with more females among ES patients as compared to the CFS and control groups. Disability level did not differ between the ES and CFS groups, indicating that patients in both groups were on a similar level of sick leave. None of the individuals in the control group were on sick leave ().

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of participants with ES, CFS and healthy controls are presented by number of participants and percentage per group, except for age and duration (presented by mean and standard deviation (SD)).

The number of participants with depression and anxiety scores higher than 10 according to the HADS were calculated and compared between the groups (). For the depression subscale, 14 patients (47%) in the ES group, 8 (21%) in the CFS group and 1 (3%) participant in the control group scored equal or higher than 10. Anxiety scores higher than 10 were found for 14 (47%) ES patients, 5 (13%) CFS patients and none of the control group. A significant difference in both depression and anxiety scores was revealed between the groups when comparing number of participants who had HADS scores higher than 10 ((X2(df 2, N = 98) = 22.44, p < .000)).

SF-36 scores

An ANOVA revealed significant differences between the groups. Patients with CFS scored lower, as compared to ES and controls, n the following domains of the SF-36: Physical Function (PF), role limitations caused by physical problems (RF), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), energy/vitality (VT) and social functioning (SF) (). Physical Component Summary scores were also lower in comparison to ES and controls. ES patients scored lower in role limitations caused by physical problems (RF), energy/vitality (VT) and social functioning (SF). ES patients also scored lower role limitations caused by emotional problems (RE) and on the Mental Component Summary score as compared to both CFS and controls (). No differences were found in mental health (MH) scores between the groups.

Figure 1. Results present SF-36 dimensions as mean and 95% confidence interval.

Notes: PF = physical functioning, RF = role emotional, BP = bodily pain, GH = global health, VT = vitality, SF = social functioning, RE = role emotional, MH = mental health, PCS = Physical Component Summary, MCS = Mental Component Summary. CFS = chronic fatigue syndrome, ES = exhaustion syndrome and HC = control group. *Differences between CFS and HC (***p < .000), + between CFS and ES (++ p < .001 and +++p < .000), ^differences between ES and HC (^^p < .001 and ^^^p < .000).

MANCOVA: impact of emotional status on SF-36 dimensions

Covariate ‘group’ affected all SF-36 variables, except role limitations caused by emotional problems (RE) and the Mental Component Summary scores. The effects were medium-large (). Covariate ‘gender’ did not show any effect (not presented). Interaction between ‘group’ X ‘gender’ had a medium effect only on Physical Component Summary scores (F =4.483, p = .014, η2 = 0.099). Covariate ‘depression’ (on the HADS) was associated with physical function (PF), general health (GH), energy/vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), limitations caused by emotional problems (RE), and the Mental Component Summary scores (medium-large effects) (); while covariate ‘anxiety’ (HADS) influenced only social functioning (SF) (small effect, F = 6.068, p = .016, η2 = 0.069). Covariate ‘duration’ did not show any effect on SF-36 variables (not presented).

Table 3. Multivariate (MANCOVA) test of between-subject effects.

Discussion

Despite overlapping symptoms and calls for research comparing and differentiating ES and CFS [Citation1,Citation29], this is the first study comparing quality of life in these populations. The findings indicate similarities, with both groups exhibiting a substantially lower self-reported general health and quality of life than controls, particularly in areas of physical and social functioning and in dimensions of vitality and energy. The findings also revealed some specific differences in quality of life, i.e. patients with CFS reported their physical functioning to be lower and their pain to be greater while paradoxically reporting significantly better mental health than ES.

Clinically, it is important to differentiate CFS and ES in order to provide appropriate treatment and medical care. Research indicates that spontaneous recovery in CFS is rare and that these patients do not respond to CBT and multidisciplinary rehabilitation to the same extent as patients with ES [Citation14,Citation19,Citation20]. It has been empirically shown that patients with CFS can be differentiated from other samples (healthy controls and fatigue-causing medical and psychiatric conditions, e.g. idiopathic chronic fatigue, psychiatric disorders) using the following subscales and cut-off scores in SF-36: energy/vitality (VT) (≤35), social functioning (SF) (≤62.5), and role limitations caused by physical problems (RF) (≤50) [Citation25]. In this study, both CFS and ES patients had lower scores on these subscales as compared to controls. Both illness groups fell well below the suggested normative cut-off scores suggesting that these scores might not be suitable for differentiating CFS and ES. Instead, our results suggest that viewing the subscales of physical functioning (PF), bodily pain (BP) and role limitations caused by emotional problems (RE) might be important. Patients with CFS scored lower on the physical dimensions (PF, BP, Physical Component Summary) than ES patients and controls. This might be expected since CFS affects physical capacity and often results in reduced physical functioning and difficulties participating in daily life activities. One of the diagnostic criteria for CFS is at least a 50% reduction in function as compared to pre-morbid levels [Citation3]. One reason for reduced function in CFS may be post-exertional malaise, another diagnostic criterion for CFS [Citation30] as well as a major symptom which limits physical capacity and endurance. The SF-36 scores, particularly the physical function (PF) subscale might efficiently capture this substantial reduction of physical functioning and perhaps be helpful in diagnosing CFS.

A previous study that also used Canadian criteria to diagnose CFS found both physical and mental health scores in SF-36 to be markedly low, indicating distress in both areas of quality of life [Citation25]. In contrast, CFS patients in the present study did report a more pronounced physical function reduction as compared to ES; however, in CFS, significantly better mental health score was found. Specifically, patients with ES had lower scores on both the role emotional subscales and the Mental Component Summary as compared to both CFS and controls. Given that patients with CFS had longer illness duration, one could argue that these patients had learned to cope better with their illness. However, illness duration did not affect SF-36 scores, suggesting other explanations for this finding. Another explanation could stem from the fact that the diagnosis of ES is not as well-known and established in the international community, possibly lumping together patients with ES and CFS in the same category in previous studies.

Another finding in the present study is the interaction between HADS depression scores and several dimensions in the SF-36, except for areas associated with physical functioning (role physical, bodily pain, and Physical Component Summary). Furthermore, a larger number of ES as compared to CFS patients scored higher than 10 in the HADS depression and anxiety scales. This indicates that the affective component in ES patients appears to be more prominent as compared to CFS, possibly as a result of a higher stress levels. This also supports the necessity to treat depression and anxiety (pharmacologically or with psychotherapy) in order to enhance health-related quality of life [Citation9].

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. In this study, there was a female dominance in the sample. Although this is often the case in ES [Citation31] and CFS [Citation3], it might affect generalizability. Nevertheless, this might imply an importance of a gender factor in the development of ES as well as CFS. However, the SF-36 scores were not affected by gender, indicating that other interactions should be measured. Another limitation is the use of HADS to score depression and anxiety, since higher scores are not necessarily equal to a clinical disorder or diagnosis. At the same time both ES and CFS patients met a psychologist for careful investigation and those with primary/dominant symptoms of affective disorders, were not accepted to rehabilitation clinic. The third limitation is a small sample size. Therefore, the results regarding emotional impact on SF-36 must be interpreted carefully.

Some have argued that the symptoms of CFS and ES overlap and that the diagnosis stems more from the preferences of the diagnosing clinician [Citation32]. This study did not control for preferences of the clinician in the diagnostic procedure. The differential diagnosis did, however, empirically reveal some important differences in reported functioning between ES and CFS indicating that diagnoses were given to two different groups. Moreover, patients were investigated at two different clinical units situated at the same department by practitioners who had clinical experience with both diagnostic groups and the possibility to discuss the referrals before acceptance into the study.

Although the SF-36 appeared to capture important similarities and differences between ES and CFS, the results suggest a need to introduce a more specific questionnaire in order to differentiate between these two conditions. The previously suggested cut-offs for differentiating CFS from other conditions did not seem to hold in relation to ES [Citation25]. Future research. One example is the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire [Citation33], which is used for CFS patients in US but not in Sweden. Another possibility is to develop a new questionnaire to better differentiate ES and CFS in order improve accurate diagnosis and offer appropriate care to the properly identified patient.

Given that so little is known about the similarities and differences between ES and CFS and their pathophysiological mechanisms, further comparative studies are suggested. Just to mention one example: Our clinical experience indicates a gradual stress-related onset of CFS in some cases who have a preceding clinical diagnosis of ES. This raises question of whether resistant-to-treatment ES could gradually develop into CFS. Long-lasting stress can, in principle, reduce immune system activity and make a host less resistant to infectious pathogens [Citation34]. At the same time, interactions between the immune and stress-regulating systems [Citation35] might lead to the development of additional co-morbidities such as infections, pain, and sleep disorders, creating a vicious circle without less chance of recovery. From the rehabilitation perspective, it is important to accurately diagnose the condition (ES vs. CFS) in order to tailor rehabilitation interventions and to create realistic expectations and tasks for the patient.

Conclusion

This study indicates both similarities and differences between health-related quality of life in ES and CFS patients. Both ES and CFS report a low quality of life as compared to controls, but surprisingly, mental health in CFS is less affected. Depression level was an important factor affecting health-related quality of life ratings. Further research delineating similarities and differences between ES and CFS is needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel Maroti

Daniel Maroti is a neuropsychologist, and specialist in clinical psychology.

Indre Bileviciute-Ljungar

Indre Bileviciute-Ljungar is a consultant in rehabilitation and pain medicine, and associated professor in rehabilitation medicine.

References

- Utmattningssyndrom. Stressrelaterad psykisk ohälsa. In: Socialstyrelsen, editor. Stockholm: Elanders Gotab AB; 2003:1–88.

- Brurberg KG, Fonhus MS, Larun L, et al. Case definitions for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME): a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014 Feb 7;4(2):e003973. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003973

- Carruthers BM, Jain AK, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment guidelines: a consensus document. J Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2003;11:7–115. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J092v11n01_02

- Soderstrom M, Jeding K, Ekstedt M, et al. Insufficient sleep predicts clinical burnout. J Occup Health Psychol. 2012 Apr;17(2):175–183. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027518

- Prins JB, van der Meer JW, Bleijenberg G. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet. 2006 Jan 28;367(9507):346–355. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68073-2

- Grossi G, Jeding K, Soderstrom M, et al. Self-reported sleep lengths >/= 9 hours among Swedish patients with stress-related exhaustion: Associations with depression, quality of sleep and levels of fatigue. Nord J Psychiatry. 2015 May;69(4):292–299. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2014.973442

- Cockshell SJ, Mathias JL. Cognitive functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010 Aug;40(8):1253–1267. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992054

- Jonsdottir IH, Nordlund A, Ellbin S, et al. Cognitive impairment in patients with stress-related exhaustion. Stress. 2013 Mar;16(2):181–190. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2012.708950

- Jonas B, Leuschner F, Tossmann P. Efficacy of an internet-based intervention for burnout: a randomized controlled trial in the German working population. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2016 Sep;22:1–12.

- Larun L, Brurberg KG, Odgaard-Jensen J, et al. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jun;24(6). CD003200.

- Gavelin HM, Boraxbekk CJ, Stenlund T, et al. Effects of a process-based cognitive training intervention for patients with stress-related exhaustion. Stress. 2015;18(5):578–588. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2015.1064892

- Gavelin HM, Boraxbekk CJ, Stenlund T, et al. Effects of a process-based cognitive training intervention for patients with stress-related exhaustion. Stress. 2015 Aug;13:1–11.

- Rimbaut S, Van Gutte C, Van Brabander L, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome – an update. Acta Clin Belg. 2016 Jun;17:1–8.

- Vos-Vromans DC, Smeets RJ, Huijnen IP, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment versus cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Intern Med. 2016 Mar;279(3):268–282. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12402

- Stenlund T, Nordin M, Jarvholm LS. Effects of rehabilitation programmes for patients on long-term sick leave for burnout: a 3-year follow-up of the REST study. J Rehabil Med. 2012 Jul;44(8):684–690. doi: https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1003

- Pheby D, Lacerda E, Nacul L, et al. A Disease Register for ME/CFS: Report of a Pilot Study. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-139

- Flo E, Chalder T. Prevalence and predictors of recovery from chronic fatigue syndrome in a routine clinical practice. Behav Res Ther. 2014 Dec;63:1–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.08.013

- O'Dowd H, Gladwell P, Rogers CA, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised controlled trial of an outpatient group programme. Health Technol Assess. 2006 Oct;10(37). doi: https://doi.org/10.3310/hta10370

- Twisk FN, Maes M. A review on cognitive behavorial therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET) in myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) / chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): CBT/GET is not only ineffective and not evidence-based, but also potentially harmful for many patients with ME/CFS. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2009;30(3):284–299.

- Perski O, Grossi G, Perski A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of tertiary interventions in clinical burnout. Scand J Psychol. 2017 Dec;58(6):551–561. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12398

- Maroti D, Molander P, Bileviciute-Ljungar I. Differences in alexithymia and emotional awareness in exhaustion syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome. Scand J Psychol. 2017;58(1):52–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12332

- Grensman A, Acharya BD, Wandell P, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with burnout on sick leave: descriptive and comparative results from a clinical study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2016 Feb;89(2):319–329. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1075-5

- Jason LA, Benton MC, Valentine L, et al. The economic impact of ME/CFS: individual and societal costs. Dyn Med. 2008;7(6).

- Pendergrast T, Brown A, Sunnquist M, et al. Housebound versus nonhousebound patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. Chronic Illn. 2016 Dec;12(4):292–307. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395316644770

- Jason L, Brown M, Evans M, et al. Measuring substantial reductions in functioning in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(7):589–598. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.503256

- Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1994 Dec 15;121(12):953–959. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J. The Swedish SF-36 health survey III. Evaluation of criterion-based validity: results from normative population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Nov;51(11):1105–1113. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00102-4

- Lisspers J, Nygren a, Söderman E. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD): some psychometric data for a Swedish sample. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1997;96(4):281–286. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10164.x

- Dorr J, Nater U. Fatigue syndromes – an overview of terminology, definitions and classificatory concepts. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2013 Feb;63(2):69–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1327706

- Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, De Meirleir KL, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International consensus criteria. J Intern Med. 2011 Oct;270(4):327–338. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x

- Glise K, Hadzibajramovic E, Jonsdottir IH, et al. Self-reported exhaustion: a possible indicator of reduced work ability and increased risk of sickness absence among human service workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010 Jun;83(5):511–520. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-009-0490-x

- Leone SS. A disabling combination: fatigue and depression. Br J Psychiatry. Aug;197(2):86–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076604

- Brown AA, Jason LA. Validating a measure of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome symptomatology. Fatigue. 2014;2(3):132–152.

- Jonsdottir IH, Hagg DA, Glise K, et al. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and growth factors called into question as markers of prolonged psychosocial stress. PLoS One. 2009 Nov 03;4(11):e7659. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007659

- Light KC, White AT, Tadler S, et al. Genetics and gene expression involving stress and distress pathways in fibromyalgia with and without comorbid chronic fatigue syndrome. Pain Res Treat. 2012;427869.