Abstract

Objectives: This study introduces a conceptual model to investigate factors that influence healthcare utilization. The model included three components: Need for Care, Facilitators and Barriers of Access, and Health Care Utilization. Methods: A nationally representative sample of 13,244 male veterans aged 18 and older was extracted from the 2011 National Health Interview Survey. The sample included 2890 veterans with disabilities. Descriptive analyses and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed, along with significance tests for differences in distributions. Results: Need for services was operationalized by perceived health and number of types of disabilities. Both these variables, predicted healthcare utilization, making visits to the emergency room and staying in the hospital overnight. Facilitators and barriers were operationalized as political structures, societal structure, and demographic variables partially contributed to the model. The political variables, which wars the veterans fought, predicted utilization, but the societal variable, poverty, did not. There were no differences between African-Americans and Caucasians in utilization of health care. Differences did emerge based on region of domicile, marital status, and age. Conclusion: The conceptual model introduced in this paper does not support the notion that healthcare utilization is predicted by poverty. It may be that governmental insurance provides a safety net that insures access to acute medical care. Utilization also appears to be predicted by access to care, from regional resources and social support. Future research should tease apart reasons why regional differences emerge and inform policy-makers who appropriate funds for establishment of healthcare centers.

Introduction

Access to medical care affects one's health and ultimately one's quality of life. Krahn, Walker, and Correa-De-Araujo (Citation2015) argue that persons with disabilities contribute to a public health problem because they are more likely to have other poor health indicators compared to persons without disabilities. These indicators include that they report less life satisfaction, are more likely to be a victim of violent crime, report an annual household income less than $15,000, smoke cigarettes, are obese, and have less access to health care.

Equitable access is considered so vital to the well-being of citizens that the US government created a safety net to equalize disparities in affordability of care among the disabled. There are two large social insurance programs in the USA to protect the disabled: the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Added to Social Security in 1956, SSDI was established to pay benefits to disabled adult workers and their dependent family members because of a disabling illness or injury. Workers must be unable to work for at least five months to apply for benefits, and a waiting period is imposed before they receive cash benefits. In contrast, the SSI program was begun in 1974 to provide a federal safety net for the elderly and disabled, although it evolved to become a federal and state program. For the disabled component, people who are blind or children with disabilities are eligible for this program. For both SSDI and SSI, recipients must not be working and earning if they claim to be disabled.

An equivalent disability program is in place to compensate US veterans for medical conditions or injuries that are incurred or aggravated during active duty in the military, although not necessarily during the performance of military duties (Congressional Budget Office [CBO], Citation2014). This disability is administered by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). America has a long history of providing healthcare benefits to disabled veterans. As early as the Revolutionary War, veterans who sustained injury in the active service of the country received a pension. Later, the Military Disability Law of 1798 provided relief to sick and disabled seamen, which then became available to all veterans in 1830. During the Civil War, benefits increased to include soldiers whose disability could be traced back to active duty or as the result of combat (Civil War Pensions, Citation2014). Later, as a result of the large number of World War I veterans returning with disabilities, Congress passed the first major rehabilitation program for soldiers. The current US policy provides healthcare and disability services to all persons, regardless of race, who are at least 10% disabled because of injuries they incurred during active duty (U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Citation2014a).

Though widespread, SSDI and SSI coverage was substantially different from VA disability benefits. The major difference is that SSDI and SSI programs are means-tested, while VA disability compensations are not. According to CBO (Citation2014), veterans who work are eligible for benefits, and they can continue receiving their monthly payments until death. In other words, if disabled veterans are employed, they can have double incomes – work paycheck and disability paycheck.

A substantial proportion of US military personnel receive health care through the government. Healthcare services are provided by the Department of Defense's medical plan for active duty military, veterans, the National Guard, their dependents, and survivors (Military Benefits, Citation2014). The US Veterans Health Administration is the nation's largest multilevel healthcare system with 8.76 million veterans receiving health care annually in more than 1700 healthcare centers (U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Citation2014a). The Department of VA (Citation2014) recognizes the Korean War (KW), Vietnam War (VW), Persian Gulf War (PGW), and the post 9/11 wars, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). Veterans who are at least 10% disabled as a result of their service are entitled to healthcare benefits, but service men and women who were not in combat may still be eligible for health benefits.

Studying healthcare utilization among military personnel is important because many service men and women return from active duty with mental and physical traumas. Combat as well as noncombat exposure has resulted in the return of 45,000 wounded men and women after serving in OIF and OEF (Lawrence, Citation2012). According to Filliung et al. (Citation2010), the most frequent causes of battle injuries are explosions (79.3%), often from improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The IED was introduced as the weapon of choice during the PGW as a way to wound, rather than kill Allied Forces. In non-traditional warfare, using IEDs to inflict injuries was preferable to killing the enemy because it requires more service men and women to attend to a wounded comrade than to a deceased one. Wounds from explosions often need extensive rehabilitative care to improve ability to engage in normal Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), such as bathing, walking, dressing, and toileting. Treatment is on a continuum of care that begins while in the hospital, and can continue at a specialized inpatient rehabilitation unit and then to a less intensive skilled nursing facility or outpatient care facility (Resnik & Borgia, Citation2013). Many veterans need extensive health care to recover.

In addition to physical traumas, 15–30% of all returning vets from OIF and OEF suffer from serious mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Coll, Weiss, & Yarvis, Citation2012). Currently, troops who experienced intense combat are 3.5 times more likely to experience PTSD than those without combat experience (Castro & McGurk, Citation2007), but compared to persons with combat-related mental health problems, even noncombatants who are deployed to a combat region experienced PTSD (4.1% vs. 0.7%) and depression (9.9% vs.5.4%) (Peterson, Wong, Haynes, Bush, & Schillerstrom, Citation2010). According to Koenen, Stellman, Sommer, and Stellman (Citation2008), persistent PTSD can become a long-term disability. They found higher rates of mental health service utilization and health complaints among 10% of a group of 1377 Vietnam veterans who were interviewed 14 years after returning home. The long-term consequence of PTSD is significant because it is associated with increased utilization of mental health services. In addition to war-related injuries, veterans can be disabled because of medical illnesses and accidental injuries that non-veterans also experience.

The aim of this study is to investigate whether and how the disability statuses had impacts on healthcare utilization among male veterans. We hypothesize that compared to non-disabled veterans, disabled veterans had higher odds of utilizing health care, and the likelihood increased as the number of disabilities increased.

Conceptual framework

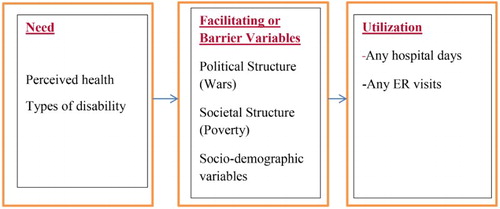

This proposed model was adapted from Andersen (Citation1995), Aday and Andersen (Citation1974), and Andersen and Newman (Citation1973) (). Model components that impact healthcare utilization include: (1) Need for Care (Perceived health, Number of disabilities); (2) Facilitating Factors or Barriers (Political Structure (wars), Societal Structure (poverty), Individual differences (race, age, education, marital status)); 3. Utilization of Care (Any visits to ED past 12 months, Number of visits to the ED past 12 months, Any hospital stay past 12 months, Number hospital stays past 12 months).

Need for health care

Types of disabilities

Veterans experience medical disabilities that are also experienced by non-veterans. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Citation2005), the five most frequent causes of disabilities (in millions) among US adults are Arthritis/Rheumatism (8.6), back or spine problems (7.6), heart trouble (3.0), lung or respiratory problems (2.2), and mental or emotional problems (2.2). These findings are similar to earlier findings based on the Framingham study's longitudinal 40-year data (Anatoli, Yashin, Akushevich, & Kulminski, Citation2006) that found that in 1994, most of the persons interviewed in the Framingham study were elderly, disabled participants who were diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis, heart disease, depressive symptomatology, and stroke and comorbid illnesses (92.9%).

The National American Community Survey (U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Citation2010) reports that 9.9% of the US noninstitutionalized civilian population aged 16–64 (19.5 million) have one of the six types of disability that include deficits in vision, hearing, cognitive, ambulatory, self-care, and independent living. Of these civilians, 30.4% receive income-based government assistance (U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Citation2013). Some problems are associated with chronic pain and the need for in-home health care, nursing home care, and assistive technological devises for mobility. Whether someone with a disability receives services depends upon whether he or she lives alone, has a high degree of impairment in completing ADLs, a low level of informal support, high level of caregiver burden, and has Medicaid coverage (Kadushin, Citation2004) in addition to their disability.

Horner-Johnson, Dobbertin, Lee, Andresen, and the Expert Panel on Disability and Health Disparities (Citation2014) found that persons with more than one type of disability were more likely to have problems utilizing health care than their counterparts, which resulted in unmet healthcare needs. King, King, Bolton, Knight, and Vogt (Citation2008) calculated the number of symptoms reported by 357 Gulf War veterans in a study of risk factors for functional health. They found that the participants reported on average having 6.34 ± 5.77 (range 0–24) symptoms. King et al. (Citation2008) found that scores on the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory War-Zone Stressor Measure, a scale of measures of war-zone stressors, exposures, and perceived treatment were most strongly correlated with number of symptoms, and PTSD.

Perceived health

In a sample of 74 veterans with a diagnosis of moderate-to-severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Braden et al. (Citation2012) found that 38% perceived their physical health to be poor and 35% perceived that their mental health was poor. These veterans’ reports are important because they were correlated with reduced life satisfaction.

Facilitators and barriers to access

Political structure

Another political factor that impacts access to health care is what healthcare services were available in the country when veterans were in need. For example, there were few substance abuse treatment centers for veterans before the VW. During that war, the country had become alarmed that service men, who had become addicted to heroin that was plentiful in Southeast Asia, would be returning stateside. Because of their concern, the National Institute on Drug Abuse was created to engage in clinical research and many treatment centers were established throughout the country. More recently, because of the increased prevalence of returning veterans with PTSD diagnoses, the Veterans Administration has developed treatment programs to care for the many service men and women suffering from PTSD, and training programs to train clinicians to work with these vets. Thus, vets who fought in the PGW and others who were discharged prior to the OIF and OEF did not have access to this type of health care.

Societal structure

The structure of American society impacts access to health care because treatment of these physical and emotional wounds is determined, in part, from one's income. Medical care from the VA is available on a sliding scale basis and veterans must demonstrate financial need to determine if they are entitled to free care, or if a co-pay is required. Veterans who are not disabled and who meet Federal Poverty Levels (FPLs) may acquire Medicaid benefits. Wong and Liu (Citation2013) found that the rate of utilization of medical care at the VA depended in part on the unemployment rate. They found that in a secondary analysis of 73,964 veterans’ survey data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, when unemployment increased one percentage point, the probability of receiving all (p = 0.056), or some (p = 0.023) care from the VA increased.

While approximately 25% of veterans utilize health care at the VA system (Department of Veterans Affairs, Citation2014), veteran status does not preclude citizens from being entitled to receive governmental benefits. Veterans may choose to opt out of veterans’ healthcare system. Medical care for disabled US civilians began when the Social Security Act was enacted in 1935 (Social Service Administration, Citation2014). In 1965, Title XIX (19) of the Social Security Act created Medicaid, the federal/state government entitlement program to pay medical costs for certain individuals with disabilities and families with low incomes. Healthcare entitlements are considered part of the political structure because both federal and state governments determine eligibility requirements for disability and the amount of cash assistance and type of in-kind benefit varies from state to state (U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Citation2013).

Socio-demographic variables

The literature reveals several variables that are correlated to healthcare disparities.

Age

According to Garcia et al. (Citation2014), mental health treatment barriers can depend upon attitudes of the veterans. They found that compared to veterans from the VW (average age 62 ± 4.2 years) and the PGW (43 ± 6.8 years), younger veterans from the OIF and OEF wars (32 ± 8.2 years) were more likely to report negative treatment attitudes than older vets from earlier wars. The younger vets equated treatment as making them feel they were unable to solve their own problems, would make them weak, and make them go crazy. In a chart review of 687,934 veterans, Lee et al. (Citation2015) also found that higher rates of healthcare utilization occurred among older veterans 50 and older compared to younger veterans. The data also indicated that the primary reason for healthcare visits among veterans was mental health treatment.

Race

Rajaram and Bockrath (Citation2011) argue that race plays a pivotal role in health disparities because it is inextricably intertwined with racism and is linked to power and privilege. According to Le Cook et al. (Citation2014), African-Americans and Latinos are less likely to access adequate mental health care, more likely to initiate care at the Emergency Department, more likely to receive only medication instead of face-to-face therapy, and have higher rates of acute episodes compared to Whites. The authors argue that initiation of care without adequate maintenance of care results in less money spent on the patient, and is a way to limit utilization of care, which in turn supports healthcare disparities. The authors did not focus on veterans; thus, evaluating whether disparities will generalize to this sample of veterans is important in order to understand the relationship of race to inequities in healthcare utilization.

Education

Le Cook et al. (Citation2014) reported that persons with more years of education were more likely to perceive lower levels of mental health, were more likely to initiate mental health care, and to receive adequate care, than persons who completed fewer years in school.

Marital status

Mistry, Rosansky, McGuire, McDermott, and Jarvik (Citation2001) found that in a sample of 125 older veterans (Mean age 70 ± 7 years), those who were socially isolated were four to five times more likely to be re-hospitalized than those veterans who were not isolated. They found that having one or two people in the veterans’ social support network predicted ability to deal with poor perceived health and reduced the number of re-hospitalizations.

Utilization of care

Barriers to healthcare utilization are varied and impact whether the medical problem improves. Singh et al. (Citation2005) reported that in a sample of 70,334 veterans, 57.6% reported lower health-related quality of life scores than the general US population. Those with lower scores on the physical and mental subscales were more likely to have difficulty completing ADLs, utilized more healthcare services and had higher rates of mortality than other veterans.

Among OIF and OEF veterans, reservists fought in greater numbers than in the past wars. Among members of the Army Reserves and the Army National Guard, 56.9% and 45.7% (respectively) utilized healthcare services within the first 12 months of deployment and received their care there for any injuries that were incurred while deployed (Harris et al., Citation2014). Those who enrolled tended to live in the South or Midwest were African-American or Hispanic, were more likely to have suffered a serious injury while deployed, or were younger. In a secondary data analysis of medical records, Funderburk, Henneson, and Maisto (Citation2014) found that younger veterans utilized services at their primary care physician less often, as well as at the emergency department, and were less likely to receive mental health care, compared to older counterparts. Veterans who were not married or who were White utilized healthcare services more often, indicating that they had worse health. On the other hand, in a large secondary data analysis of VA charts of 12,599 veterans, Resnik and Borgia (Citation2013) found that African-Americans were offered and utilized more pre- and post-operative rehabilitation services after an amputation than Whites.

Methods

Sample

Data from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) were used to examine the impact of disabilities on healthcare utilization among veterans. The NHIS, collected by the National Center for Health Statistics, US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), is an annual, ongoing, national, cross-sectional household survey of noninstitutionalized civilians living in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. A multistage probability sampling design provides rich data on illness, disability, other health problems, health insurance, healthcare access and utilization, health-related policies and issues among a set of representative respondents in every American state. The interviewers employed a computer-assisted personal interviewing mode to collect data, and one interview lasted approximately one hour. Since 1997, the revised NHIS questionnaire has core questions and supplements, with the core containing four major components – household, family, sample adult and sample child, and the supplement covering the specialized topics such as cancer screening. The NHIS data have been widely used by DHHS to monitor trends in illness and to track progress toward achieving national health objectives, and other health research scholars to evaluate healthcare utilization, and Federal health programs (CDC, Citation2012).

The original data set contained a sample of 34,550 adults with 3309 veterans and 31,241 civilians. The veteran was defined as those who had ever served on active duty in the armed forces. The final analysis was limited to only male veterans who had served in war periods. Several subgroups were removed: (1) female veterans (n = 300); (2) male veterans who only served in a humanitarian mission (n = 119); and (3) the entire civilian sample (n = 31,241). With the sample inclusion criteria in place, the final analysis included 2890 male veterans aged 18 years and older.

Measurements

Dependent variables of healthcare utilization

Two dichotomous dependent variables identified whether veterans utilized inpatient health care. The NHIS asked every respondent annually, “Did you visit the emergency room (ER) in the past 12 months”; and “Did you stay in the hospital overnight in the past 12 months.” These measures of healthcare utilization were often used in the literature (Eibich & Ziebarth, Citation2013).

Independent variable of disability

The focal independent variables used in the analysis were disability statuses. All the disability information was self-reported, suggestive of a physical, mental, or other condition which caused limitation. There were over 30 kinds of disabilities in the data set, and the 10 most frequent types were back or neck problem, arthritis, heart problem, all kinds of injury, hypertension/high blood pressure, diabetes, lung/respiratory problem, nervous system, musculoskeletal/connective tissue problem, and depression/anxiety/emotional problem. Each disability indicator was coded dichotomously with 1 indicative of being disabled. These individual disability measures were combined to create a set of four comprehensive disability measures. These include: (1) veterans without any type of disability; (2) disabled veterans with at least one type of disability; (3) disabled veterans with two types of disabilities; and (4) disabled veterans with three or more types of disabilities.

Covariates

According to the conceptual framework, four sets of covariates were included in the model. (1) Perceived health was measured using the poor health indicator, based on the question: “Would you say that your own health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor (1 = fair or poor, 0 = otherwise).” (2) The political structure was measured using the proxy of whether the respondent attended wars occurring in 1964 or earlier (yes = 1). Because the data set included past wars such as World War II, KW, VW, as well as more recent wars such as the PGW, veterans in this sample served in different periods of wars or conflicts. (3) The social factor was measured using the family income to poverty ratio. Three subgroups were generated: income below 100% of the FPL, income at or above 100% and below 200% of the FPL, and income at or above 200% of the FPL (the best off group). (4) The socio-demographic structure was included. Age was categorized into five groups: 1 = 18–34, 2 = 35–44, 3 = 45–54, 4 = 55–64, 5 = 65 and above, and the youngest group (18–34) served as reference category in the multivariate analyses. The racial and ethnic composition was indicated by a set of three dichotomous variables that identified respondents as non-Hispanic White only (yes = 1), non-Hispanic Black only (yes = 1), and other (reference group). Marital status identified categories of married, widowed, divorced, never married, or other types. Based on the categories, a dichotomous variable of being married was created with 1 = married, and 0 = otherwise. Four dichotomous indicators of the highest educational attainment were generated: less than high school (yes = 1), high school graduate (yes = 1), some college (yes = 1), and college graduate or more (reference category). Four dichotomous variables of residence of living were identified: Northeast (reference category), Midwest (yes = 1), South (yes = 1), and West (yes = 1).

Analytic plan

The percentage distributions of types of disabilities per group were studied. The breakdown of periods of service among disabled veterans was also presented. Distributional differences among four subgroups were examined: veterans with no disability (subgroup 1), veterans with one type of disability (subgroup 2), veterans with two types of disabilities (subgroup 3), and veterans with three or more types of disabilities (subgroup 4). The F-test from the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was employed to assess group mean differences, along with Tukey post hoc tests being performed to decide which groups differed from the rest. A series of multivariate logistic regression models was used to examine the associations between group identity and each dependent variable of health service utilization, “ER visit”, and “in hospital overnight”. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval were reported along with significance level. The graphs were drawn by using the statistical software STATA 12.0, and all other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

Descriptive characteristics of veterans, disability, and healthcare use

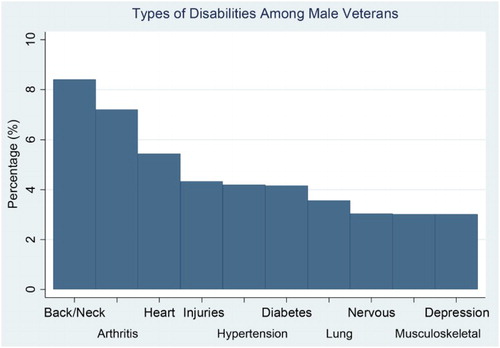

shows the percentages of the 10 most frequent disabilities in the NHIS sample for male veterans in 2013. Of disabled male veterans, 8.41% endorsed back or neck problems as their primary disability, with 7.20% reporting arthritis as secondary, with third as the heart problem (5.43%). A variety of types of injuries ranked fourth among veterans (4.33%), such as bone fracture, joint injury, stiffness, or deformity of limbs. Hypertension and Diabetes ranked the fifth and sixth among veterans (4.19% and 4.15%). The distribution of the top 10 disabilities among disabled veterans is shown in .

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of top 10 disabilities among male veterans. Source: National Health Interview Survey 2013.

Table 1. The top 10 types of disabilities per participant group.

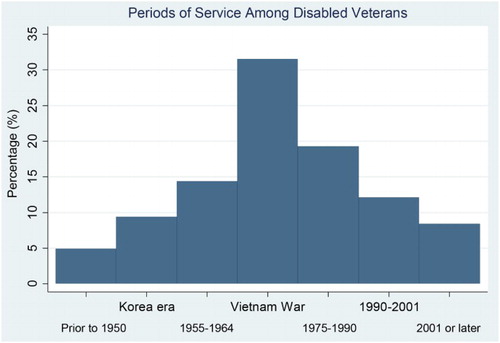

presents periods of service among these veterans. Because many veterans served in more than one war, the total number of veteran/wartime is as high as 3608, which is greater than the total number of veterans (n = 2890). As depicted, nearly 60% of the group of veterans served in wartimes prior to 1975; 31.51% served in VW (1964–1975); 14.36% served in the period of 1955–1964; 9.40% served in the KW; and 5% served in earlier wars (World War II), implying that veterans in this sample are older on average. For the more recent wartimes, 19.3% of the group served during 1975–1990; 12.11% served during 1990–2001; and the remaining 8.4% served since September 11, 2001.

Figure 3. Breakdown by periods of service among male veterans. Source: National Health Interview Survey 2013.

presents the sample descriptive statistics, stratified by total number of disabilities. The group difference was analyzed among the four subgroups: veterans with no disability (n = 2246), veterans with one type of disability (n = 352), veterans with two types of disabilities (n = 129), and veterans with three types of disabilities (n = 163). According to , disabled veterans were consistently worse off, and statistically significant differences emerged between non-disabled veterans and disabled veterans for the vast majority of the variables. Disabled veterans were more likely to have visited the ER during the past 12 months, and the percentages of having ER visits were observed monotonically increasing as the number of types of disabilities increased (16.7% for non-disabled, 29% for one disability, 42.3% for two disabilities, and 47.1% for three or more disabilities). A similar pattern was witnessed in terms of hospital stays. The Tukey's post-doc tests reported that the prevalence rates in ER visits and hospital stays among one disability and two disabilities were significantly higher than no disability group.

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics of health service utilization among male veterans, NHIS2013.

As for perceived health, the percentages of perceived poor health were increasing as the number of disabilities increased. In terms of the political structure, nearly one-third of veterans in each subgroup attended wars during the period of 1964 or earlier. In terms of the social structure, the more disabled veterans faced higher risk of poverty. Of the total number of veterans with three or more kinds of disabilities, 18.8% were below 100% FPL, and 30.6% fell between 100% and 200% FPL, and only half of them lived above 200% FPL. The prevalence rates of poverty were significantly higher among veterans with more disabilities than fewer disabilities, as shown by Tukey post-doc tests.

also presents the distribution of the socio-demographic characteristics across subgroups. Results show that half of the sample was veterans older than retirement age (65 years old), and the more disabled veterans were more likely to be older. In terms of their race/ethnicity, the most disabled veterans were more likely to be African-Americans compared to other racial/ethnic subgroups. The marital status among veterans with different kinds of disabilities varied substantially. The most disabled veterans had the lowest proportion of being married (38.5%), and the highest proportion of being divorced (31.6%). In terms of their highest educational attainment, the most disabled veterans had the highest proportion of having high school degrees (38.2%), and non-disabled veterans had the highest proportion of having bachelor or above degrees (27.8%). In terms of residence of living, disabled veterans were more likely to live in South.

Multivariate analysis of healthcare utilization

Multivariate logistic regression analysis results () provided additional evidence that disability statuses were strongly associated with healthcare utilization after controlling for perceived health, political structure, social structure, and socio-demographic characteristics. Compared to non-disabled veterans, the odds of ER visits or staying in the hospital overnight were 50% higher among veterans with one type of disability (OR = 1.512, p < 0.01 for ER visit; OR = 1.573, p < 0.05 for hospital nights). Relative to the same reference group, the odds of ER visits or staying in the hospital overnight were more than doubled among veterans with two types of disabilities(OR = 2.245, p < 0.001 for ER visit; OR = 2.315, p < 0.001 for hospital nights). Additionally, the odds of ER visits or staying in the hospital overnight were 150% higher among the most disabled veterans (OR = 2.633, P < 0.001 for ER visit; OR = 2.493, p < 0.001 for hospital nights). Perceiving own health as poor or fair was also significantly associated with higher likelihoods of ER visits and staying in the hospital overnight.

Table 3. Logistic regression on effects of “disability status” on health service utilization.

In addition, the majority of predisposing factors (political structure, societal structure, and socio-demographic variables) were associated significantly with healthcare utilization in the expected directions. The odds of ER visits were higher among veterans with more distant military service 1964 or earlier (OR = 1.352, p < 0.05). Although the ANOVA analysis showed that the disabled veterans were more likely to be at risk of poverty, none of the multivariate results revealed statistical significance, and the effect of living under 100% FPL on ER visits was marginally significant (p = 0.092). The odds of age categories were lower for ER visits, but higher for staying in the hospital overnight. For instance, compared to the reference group aged 18–34, veterans over 65 were 41% less likely to visit the ER (OR = 0.59, p < 0.05), but 164% more likely to stay in the hospital overnight (OR = 2.643, p < 0.05). In terms of racial/ethnic differences, both Caucasians and African-Americans were more likely to stay in the hospital overnight compared to other racial/ethnic subgroups. Marriage played an important role for people to be cared by their family members. Compared to other types of living arrangements (widowed, divorced, never married, or other), married veterans had a 23% lower odds of staying in the hospital overnight (OR = 0.765, p < 0.05). Veterans living in the West were less likely to stay in the hospital overnight. The education variable was observed with no statistical significance.

Discussion

By employing the NHIS 2013, this secondary data analysis of 2890 male veterans aged 18 and older revealed that disabled veterans utilized the healthcare system more often, and utilization increased as the number of disabilities increased. Compared to non-disabled veterans, disabled veterans on average were older, more likely to be African-American, less likely to be married and more likely to be divorced, had completed fewer years of education and lived in the South. Disabled veterans were at higher risk of poverty. Compared to their non-disabled counterparts, disabled veterans had much higher proportions living under 200 FPL: 39% among veterans with one disability, 46% among veterans with two disabilities, and 49.4% among veterans with three or more types of disabilities. Although only 10.4% of non-disabled veterans self-reported their health as poor or fair, the percentages skyrocketed among disabled veterans: 40.5% among veterans with one disability, 57% among veterans with two disabilities, and 66.1% among veterans with three or more disabilities.

Ranking of illnesses placed back or neck problem, arthritis, heart problems, injuries (fracture, bone, joint and other), hypertension, diabetes, lung/respiratory problem, nervous problem, musculoskeletal/connective tissue problem, and depression/anxiety/emotional problem as the most frequent ten types of disabilities among disabled veterans. Among the veterans, “injury” was the fourth most common disability, which may imply that their disabilities were related to their military service. According to the data, more than half of the disabled veterans (58%) served in early wars prior to 1975 (VW, KW, World War II), and the veterans tended to be older. Thus, they are entitled to old age benefits as well as disability benefits, such as Combat-related Special Compensation. These benefits afford them better resources and health care. Over time, as those male veterans who served in the more recent conflicts such as the OIF and OEF will become the majority of the sample in new waves, disabilities due to lower limb injuries, burns to the skin, and genitourinary trauma are expected to be more frequent because they are the signature wounds of OIF and OEF, and are often the results of detonation of explosive devises. Because depression, PTSD, and attempted suicide are frequent problems in OIF and OEF, problems of emotional disorder are also expected to become more frequent disabilities.

Results from the multivariate analysis reported that these data partially supported the conceptual model introduced in this study. The model proposed that a person's need for health care, mediated by intervening facilitators and barriers, predicted utilization of services ().

Needs for health care

In this sample of veterans, the need for health care was demonstrated by the type of disabilities and the number of disabilities. Of the 2890 veterans, 22.28% of the entire group was treated for at least one disability. Veterans with disabilities self-reported poor health in a linear fashion. Of the veterans reporting poor perceived health, 11.51% of the group had one disability, 44.19% had two disabilities, and 40.55% had three or more disabilities. These data support the literature and are important because poor self-reported health is correlated with low quality of life (Braden et al., Citation2012), and lower scores on mental and physical indicators (Singh et al., Citation2005). These data support the proposed model of health utilization because they show that persons with increasing types of disabilities have greater needs and therefore increased odds of utilizing emergency department visits and staying in the hospital overnight. For every additional type of disability, the odds increase in a linear fashion. As these data show, 10.1% of these veterans have been diagnosed with more than one disability. As evident in , persons with two (42.3%) and three (47.1%) disabilities made visits to the emergency department. Similar findings emerged for hospital stays. The more disabilities veterans had, the more likely they were to stay overnight in the hospital. These data do not support Horner-Johnsons et al.'s (Citation2014) findings that persons with more than one type of disability were more likely to have problems utilizing health care. On the contrary, these data suggest that persons with more than one disability were more likely to access health care. The difference in their findings may be because they measured access of, not use of, health care in a national sample that did not tease apart which participants were veterans. Horner-Johnson et al. did tease apart impairments (hearing only, vision only, physical function only, cognitive function only, and more than one type of limitation). The data in this study did not separate types of limitations, but only assessed number of types of disabilities as components of the need category.

Facilitators/barriers

Income levels below the FPL were strongly related to the number of disabilities in the sample. While there was no significant relationship of income in the multivariate analysis, there was a trend. There was, however, a significant relationship of ER visits and whether the veterans served in a war that occurred during 1964 or earlier. This was expected, as older veterans were engaged in earlier wars. This positive relationship between healthcare utilization rate and old ages is consistent with research findings by Lee et al. (Citation2015). Interestingly, however, there was not a significant relationship of staying in the hospital overnight with whether the war was during 1964 or earlier.

According to Rajaram and Bockrath (Citation2011), African-Americans would be expected to access health care less than Caucasians because of racism that, they argue, is inherent in the society. The data reported here do not support their theory. Race was not predictive of ER visits, and there was no difference between African-Americans and Caucasians in overnight stays in the hospital. While poverty is a proxy for race in several contexts, it does not predict utilization of health care in these data. One explanation for this discrepancy is that Rajaram and Bockrath did not focus only on veterans and a concerted effort has been made in 1948 to desegregate the Armed Forces, and reduce racial discrimination by President Truman's Executive Order 3381.

Other demographic characteristics did predict healthcare utilization. Persons who utilized services at the emergency department were younger (35–44 years) and older (65 + years), yielding a bi-modal distribution. The group of veterans 65 years and older was less likely to visit the emergency department, and less likely to stay overnight at the hospital. The younger group may be more at risk for accidental injuries than middle-aged or older veterans, while the oldest group may be more at risk for illnesses and therefore stay overnight at the hospital. According to the Washington Post article (Brown, Citation2013), returning veterans from OIF and OEF have a 75% greater chance of being killed in an automobile accident than civilians. It is unknown how their mental health status is related to automobile accidents, but Garcia et al. (2014) predicted that young veterans are less likely to access health care in a mental healthcare setting. While these data do not tease apart mental health care from other health care, it would be interesting to do so in future research to determine whether ER visits are related to emotional problems.

Being married predicted less likelihood of staying overnight at the hospital compared to veterans who were unmarried, perhaps because being married provides social support and tangible resources. Persons who are single, by virtue of divorce, widowhood, or never having been married are without in-home care for recuperation after an outpatient procedure, or a condition that requires oversight. They therefore would be more likely to remain overnight in the hospital to recover. These data are supported by Mistry et al.’s (Citation2001) finding that veterans who were socially isolated were more likely to be re-hospitalized than veterans who had a social support network. Mistry et al. (Citation2001) also found that having a social network of friends reduced isolation. It would be interesting in the future to examine these data to determine the extent of social support and whether that has an impact on number of hospital stays and ER visits. Mistry et al.'s findings of limited access to care could also be applied to geographic region of the country where the participants resided. In this study, residents of the South and West were less likely to visit the emergency department, perhaps because of fewer resources due to low population density. Our data were somewhat supported by Harris et al.’s (Citation2014) findings that National Reservists living in the South were significantly less likely to utilize services at the VA, compared to persons living in the Western and Midwestern regions of the USA. They did not study the regular armed forces, however, and their data can only be partially supportive.

Utilization of healthcare services

Overall, these data indicate that healthcare utilization, regardless of whether it is a visit to the emergency department or an overnight stay in a hospital, depends upon perceived and diagnosed need. The only political barrier, as operationalized by war, whether the war occurred from 1964 or earlier, was a proxy for age. The social factor, as operationalized by the variable poverty, did not predict utilization of care. One can speculate that, even though the veterans lived in poverty, they still qualified for governmental assistance (Medicaid) and were able to access healthcare services. Ultimately, the most salient factors in healthcare utilization were subjective and objective determinants of need for services. Need, as measured by number of types of disabilities, was correlated with several demographic variables, including age, race, and marital status, but the strongest predictors of healthcare utilization were perceived need and disabilities. These findings provided moderate support for the conceptual model presented in this paper. Future research will need to tease apart the variables that contribute to facilitators and barriers.

It is worth mentioning that healthcare utilization covers a wide range of forms, and healthcare services can be provided in different types of settings. According to CDC (Citation2004), Americans utilized health care in the following forms: office-based physician visits, hospital outpatient department visits, hospital Emergency Department visits, short-stay hospital discharges, along with long-term care, rehabilitation, end-of-life care. In terms of settings, the utilization can take place in different locations: hospitals, nursing home, home, and community. This current study only focused on two common indicators: hospital stay and ER visit. The future study will incorporate more common healthcare utilization indicators such as doctors’ office visits because Americans fulfill their primary care needs by visiting doctors’ offices.

Methodological considerations

There are several limitations of this study that deserve additional attention. First, results from the multivariate analyses should be interpreted as relational, not causal. It is possible that disabled veterans and non-disabled veterans differ substantially on unobserved characteristics which affect their probability of utilizing health care. Although key dimensions of Anderson's model of healthcare utilization were measured (need for care, facilitators/ barriers, and utilization of care), certain factors such as health insurance were not assessed in this study. Second, the cross-sectional nature of NHIS data prevented us from discovering whether a longitudinal relationship exists between disability status and utilization of health care. Therefore, we are unable to trace the dynamics of behaviors and control for unobserved fixed characteristics. Third, the NHIS did not include institutionalized people. Thus, the information is unknown regarding what disabilities people in nursing homes or rehabilitative centers have. This is important because nursing homes are an expensive, but common way to utilize health care.

Despite these methodological limitations, this study uses a large US national representative data set of veterans, and contributes to the literature by examining the association between disability statuses and healthcare utilization. Future research should address the following important research questions. First, the influence of health insurance on healthcare utilization among veterans should be studied. With the inclusion of health insurance in the Anderson model, the enhanced framework can provide a more comprehensive understanding of healthcare utilization among this specific population. Second, the interaction of poverty and disability status needs to be investigated. The substantially higher rate of poverty among disabled veterans is noteworthy. On the one hand, as it is known that some disabilities can be alleviated or eliminated (hypertension) while other disabilities can be permanent (amputations), a more thorough understanding of the severity and trajectory of disabilities and limitations would contribute to our understanding of the high poverty rate among this specific population. On the other hand, the results may imply that the low amount of disability benefits and/or lack of a primary earner in the household could possibly contribute to this high poverty rate. This adds to the argument that benefit levels for disabled veterans are inadequate and need to be adjusted (Fulton, Belote, Brooks, & Coppola, Citation2009). Knowing the nexus of disability and poverty can advance our understanding of healthcare utilization.

Conclusion

This study indicates that disability statuses are important predictors of their utilization of health care among male veterans, controlling for health, political, societal factors, and socio-demographic characteristics. There is a need for policy-makers, researchers, practitioners, and caregivers to consider the healthcare needs and utilization of care among disabled veterans. Although the military is perceived to provide extensive benefits and services to veterans who once sacrificed for the country by serving in the armed forces, there is still need for efforts to increase health-related service and poverty reduction programs to those disabled veterans. The joint efforts between Veteran Administration and local communities (welfare programs, public health agencies) can be initiated to provide job-related training, education, and socialization to advance veterans’ employment opportunities and self-sufficiency. More access to regular visits to primary care providers may reduce the frequency for ER visits and hospital stays, and therefore ease the burden for their family and the society as a whole.

Acknowledgements

Both authors are responsible for the manuscript preparation, final approval of manuscript content, and submission. They both wrote a substantial portion of the manuscript, and contributed significantly to the scientific content of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aday, L. A., & Andersen, R. (1974). A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research, 9(3), 208–220.

- Anatoli, L., Yashin, L. V., Akushevich, L., & Kulminski, A. (2006). Insights on aging and exceptional longevity from longitudinal data: Novel findings from the framingham heart study. Age, 28(4), 363–374. doi:10.1007/s11357-006-9023-7

- Andersen, R. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284

- Andersen, R., & Newman, J. F. (1973). Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society, 51(1), 95–124. doi: 10.2307/3349613

- Braden, C. A., Cuthbert, J. P., Brenner, L., Hawley, L., Morey, C., Newman, J., … Harrison-Felix, C. (2012). Health and wellness characteristics of persons with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 26(11), 1315–1327. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.706351

- Brown, D. (2013, May 5). Motor vehicle crashes, a little-known risk to returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. The Washington Post.

- Castro, C. A., & McGurk, D. (2007). The intensity of combat and behavioral health status. Traumatology, 13, 6–23. doi: 10.1177/1534765607309950

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). Health care in America: Trends in utilization. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/healthcare.pdf

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults – United States, MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 58(16), 421–426.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). About the national health interview survey. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm

- Civil War Pensions. (2014) Home of the American civil war. Retrieved from http://www.civilwarhome.com/pensions.html

- Coll, J. E., Weiss, E. L., & Yarvis, J. S. (2012). No one leaves unchanged – insights for civilian mental health care: Professionals into the military experience and culture. In J. Beder (Ed.), Social work practice with the military (pp. 18–33). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Congressional Budget Office. (2014). Veterans’ disability compensation: Trends and policy options. Retrieved from http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/45615-VADisability_2.pdf

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2014) National survey of veterans. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/vetdata/utilization.asp

- Eibich, P., & Ziebarth, N. R. (2013) Analyzing regional variation in health care utilization using household micro data (IZA discussion paper series No. 7409). Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp7409.pdf

- Filliung, D. R., Bower, L. M., Hopkiins-Chadwick, D., Leggett, M. K., Bacsa, C., Harris, K., & Steele, N. (2010). Characteristics of medical-surgical patients at the 86th combat support hospital during operation Iraqi Freedom. Military Medicine, 175(12), 971–977. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-09-00270

- Fulton, L. V., Belote, J. M., Brooks, M. S., & Coppola, M. N. (2009). A comparison of disabled veteran and nonveteran income: Time to revise the law? Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 20(3), 184–191. doi: 10.1177/1044207309341359

- Funderburk, J. S., Henneson, A., & Maisto, S. A. (2014). Identifying classes of veterans with multiple risk factors. Military Medicine, 179(10), 1119–1126. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00119

- Garcia, H. A., Finley, E. P., Ketchum, N., Jakupcak, M., Dassori, A., & Reyes, S. C. (2014). A survey of perceived barriers and attitudes toward mental health care among OEF/OIF veterans at VA outpatient mental health clinics. Military Medicine, 179(3), 273–278. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00076

- Harris, A. H. S., Chen, C., Mohr, B. A., Adams, R. S., Williams, T. V., & Larson, M. J. (2014). Predictors of army national guard and reserve members’ use of veteran health administration health care after demobilizing from OEF/OIF deployment. Military Medicine, 179(10), 1090–1098. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00521

- Horner-Johnson, W., Dobbertin, K., Lee, J. C., Andresen, E. M., & the Expert Panel on Disability and Health Disparities. (2014). Disparities in health care access and receipt of preventive services by disability type: Analysis of the medical expenditure panel survey. Health Research and Educational Trust, 49(6), 1980–1999.

- Kadushin, G. (2004). Home health care utilization: A review of the research for social work. Health and Social Work, 29(3), 219–244. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.3.219

- King, L. A., King, D. W., Bolton, E. E., Knight, J. A., & Vogt, D. S. (2008). Risk factors for mental, physical, and functional health in Gulf War veterans. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 45(3), 395–407. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2007.06.0081

- Koenen, K. C., Stellman, S. D., Sommer, J. F., & Stellman, J. M. (2008). Persisting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and their relationship to functioning in Vietnam veterans: A 14-year follow-up. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(1), 49–57. doi: 10.1002/jts.20304

- Krahn, G. L., Walker, D. K., & Correa-De-Araujo, C. (2015). Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. American Journal of Public Health, 105(S2), S198–S206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182

- Lawrence, L. (2012). Physically wounded and injured warriors and their families: The long journey home. In R. M. Scurfield & K. T. Platoni (Eds.), War trauma and its wake: Expanding the circle of healing (pp. 134–155). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Le Cook, B., Zuvekas, S. H., Carson, N., Wayne, G. F., Vesper, A., & McGuire, T. (2014). Assessing racial/ethnic disparities in treatment across episodes of mental health care. Health Services Research, 49(1), 206–229. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12095

- Lee, S. E., Fonseca, V. P., Wolters, C. L., Dougherty, D. D., Peterson, M. R., Schneiderman, A. I., & Ishii, E. K. (2015). Health care utilization behavior of veterans who deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. Military Medicine, 180, 374–379. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00250

- Military Benefits. (2014). TRICARE benefits. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/benefits/tricare

- Mistry, R., Rosansky, J., McGuire, J., McDermott, C., Jarvik, L., & the UPBEAT Collaborative Group. (2001). Social isolation predicts re-hospitalization in a group of older American veterans enrolled in the UPBEAT Program. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16, 950–959. doi: 10.1002/gps.447

- Peterson, A. L., Wong, V. Haynes, M. F., Bush, A. C., & Schillerstrom, J. E. (2010). Documented combat-related mental health problems in military noncombatants. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 674–681. doi:10.1002/jts.20585

- Rajaram, S. S. & Bockrath, S. (2011). Cultural competence: New conceptual insights into its limits and potential for addressing health disparities. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 7(5), 82–89.

- Resnik, L. J., & Borgia, M. J. (2013). Factors associated with utilization of preoperative and postoperative rehabilitation services by patients with amputation in the VA system: An observational study. Physical Therapy, 93(9), 1197–1210. doi:10.2522/ptj.20120415

- Singh, J. A., Borowsky, S. J., Nugent, S., Murdoch, M., Zhao, Y., Nelson, D. B., … Nichol, K. L. (2005). Health-related quality of life, functional impairment, and healthcare utilization by veterans: Veterans’ Quality of Life Study. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 53, 108–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53020.x

- Social Service Administration. (2014). The social security act of 1935. Retrieved from http://www.ssa.gov/history/35act.html

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. (2010). Disability among the working age population: 2008–2009. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/acsbr09--12.pdf

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. (2013). Disability characteristics of income-based government assistance recipients in the United States: 2011. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/library/publications/2013/acs/acsbr11-12.html

- U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. (2014a). Disability compensation. Retrieved from http://www.benefits.va.gov/COMPENSATION/types-disability.asp

- U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. (2014b). Veterans health administration. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/health/

- Wong, E. S., & Liu, C.-F. (2013). The relationship between local area labor market conditions and the use of Veterans Affairs health services. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 96. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/13/96