Abstract

Discrimination and victimization are very common experiences of transgender women. Social marginalization is often linked to poor mental health, substance use, and risky sexual behaviors. HIV prevalence in transgender women in the USA may be as high as 27.7%, and has been estimated at nearly 50 times that of the overall adult population globally. It is in this context that we test structural equation models for the relationships among perceived gender-identity discrimination, internalized anxiety about being transgender (transphobia), mental health problems, illicit substance and alcohol use, and HIV risk behaviors. We tested two mediational models: one that proposes mental health, alcohol, and other substance use as key mediators of sexual risk behaviors, and the other that posits the exchange of sex for money or goods as a key mediator linking mental health and substance use with other risky sexual behaviors. Our results suggest that perceived gender-identity discrimination and internalized transphobia are both significantly related to mental health problems. In turn, in the first model, mental health problems were marginally related to number of sexual partners and sex under the influence of drugs. In addition, alcohol use played a key role in risky sexual behaviors in both models and having sex in exchange for money or goods also played a significant role in the second model. We discuss some of the limitations in the data and analyses that require further research to explore these relationships more carefully.

Discrimination based on gender identity is extremely common among transgender individuals (Clements-Nolle, Marx, & Katz, Citation2006). Anxiety caused by stigma and discrimination may result in increased risky sexual behaviors and has been linked to the need for gender affirmation (Sevelius, Citation2013). Social marginalization has been linked to HIV infection and risk behavior as well as violence among transgender individuals (Brennan et al., Citation2012). MTF (male to female) individuals (i.e. transgender women) report high rates of risky sexual behavior, including unprotected anal sex, and high levels of substance use, including silicone injections, marijuana, and alcohol (Garofalo, Deleon, Osmer, Doll, & Harper, Citation2006). Melendez and Pinto (Citation2007) found that stigma and discrimination among MTF transgender individuals increased the need to feel “safe and loved by a male companion” and subsequently led to more risky sexual behaviors (p. 233). Indeed the prevalence of HIV among transgender women in the USA may be as high as 27.7% (Herbst et al., Citation2007), as compared to the relatively high estimated prevalence for men who have sex with men (MSM) at 6.9% (Purcell et al., Citation2012). Globally, the HIV prevalence rate for transgender women has recently been estimated at nearly 50 times that of the overall adult population (Baral et al., Citation2013).

Discrimination experienced by transgender individuals has also been associated with a number of mental health problems. In a meta-analysis, Herbst et al. (Citation2007) found that MTF transgender individuals had high rates of suicidal thoughts (53.8%) and attempts (31.4%). Mathy (Citation2002) found that transgender individuals were more likely to have mental health problems compared to heterosexuals and MSM. Research has shown that transgender individuals often report feeling uncomfortable (60.4%) or unsafe (76.6%) in public settings (Herbst et al., Citation2007). Nemoto, Bodeker, and Iwamoto (Citation2011) found that more than two-thirds of participants had been ridiculed or embarrassed by family and 75% reported experiencing transphobia via verbal harassment, being made fun of, or being the victims of jokes, and that these experiences were associated with depression. Clements-Nolle et al. (Citation2006) found gender-identity-based discrimination and victimization to be independently associated with attempted suicide among transgender individuals, as well as significant associations between suicide and depression, gender discrimination, verbal victimization, and physical victimization.

Gender-identity-based discrimination has also been linked to violence and social barriers. Lombardi, Wilchins, Priesing, and Malouf (Citation2001) found more than half of their sample reported experiencing harassment or violence in their lifetimes and discrimination was the strongest predictor of experiencing violence. Discrimination has been found to be a barrier in obtaining ideal living environments and has been cited as a reason for eviction (Xavier, Bobbin Singer, & Budd, Citation2005). In one study of low-income Latina MTF, 14% of the sample reported experiencing daily discrimination and 25% reported experiencing weekly discrimination, including being accused of sex work or positive HIV status, threats, name-calling, denial of housing or employment, or being unjustly stopped by law enforcement (Bazargan & Galvan, Citation2012). MTF individuals have also reported using illicit substances as coping mechanisms for stresses linked with sex work, transphobia/discrimination, and economic issues (Nemoto, Operario, Keatley, & Villegas, Citation2004). Among transgender individuals, dropping out of school (Wilson et al., Citation2009), feelings of judgment, and denial of employment on account of gender-based discrimination have been associated with sex work (Reisner et al., Citation2009). African-American MTF participants reported feeling that they were not appropriately targeted in HIV risk education or HIV prevention efforts (Crosby & Pitts, Citation2007).

Beyond these specific empirical relationships among discrimination, transphobia, mental health, substance use, and HIV risk behaviors among MTF transgender individuals, we looked for mediational and process models that researchers have considered and/or tested in relation to the process leading to sexual risk behaviors among MTF individuals. Two such models include “syndemic theory”, which focuses on the additive or multiplicative effects of various risk factors (e.g. substance abuse, mental illness, poverty, victimization, violence, and discrimination) on HIV risk behavior or HIV status (Singer & Clair, Citation2003; Operario & Nemoto, Citation2010; Brennan et al., Citation2012) and a “gender affirmation” framework for understanding risk behavior among MTF individuals of color (Sevelius, Citation2013). This latter framework suggests that social oppression and psychological distress may lead to a threat to identity, leading to time spent in high risk contexts (e.g. sex for exchange of money, drugs, or shelter; unequal power in sexual relationship; and/or sex under the influence of alcohol or other substances) and ultimately risk behavior.

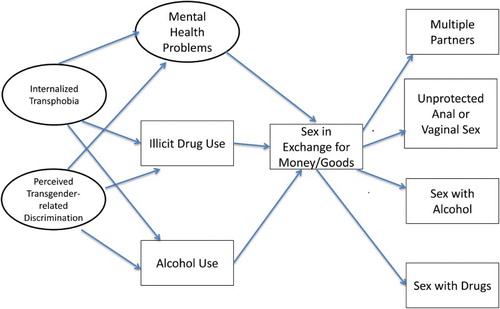

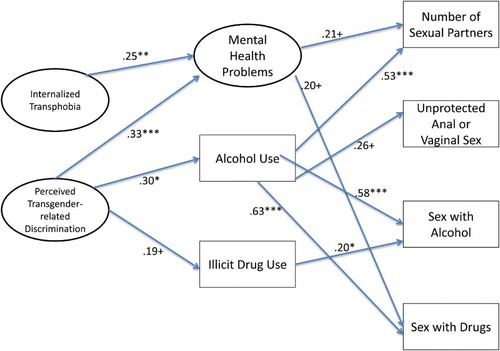

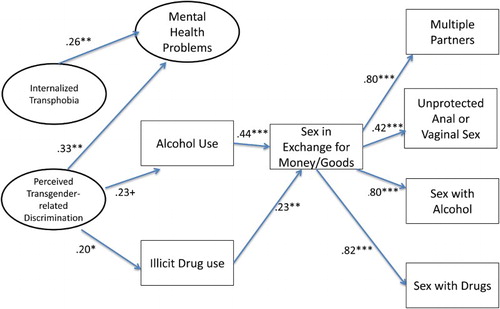

Because of the relatively little work on the process and series of psychosocial mechanisms leading to HIV risk behavior in transgender women, the purpose of the current study was to create a mediational model linking gender-identity-related discrimination, internalized transphobia, mental health problems, substance use, and HIV risk behaviors in a sample of transgender women. The potential contribution of a mediational model to our understanding of this process is the delineation of potential targets of interventions at various stages of the process (cf. MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, Citation2007). We present two possible versions of this process. presents one hypothesized process model for relationships among these problems with epidemic proportions in this population and measured in this study. Essentially, from left to right, and consistent with the syndemic model presented earlier, perceived gender-identity discrimination and internalized transphobia are proposed to have direct effects on mental health problems, alcohol and illicit drug use, and those three co-occurring problems are predicted to lead to HIV risk behaviors. HIV risk behaviors as operationalized in this study include multiple partners, unprotected anal or vaginal sex, sex in exchange for money or goods, lack of condom use with any or new partners, and sex under the influence of various substances. In we present a model more consistent with the gender affirmation framework, with high risk contexts suggested as an additional step in the model, finally leading to sexual risk behavior. Consistent with some of the stories we have heard in our work with the transgender community and in focus group and interview data we have collected from transgender women, we propose in this model that sex in exchange for money, drugs, or other goods may be an important and central causal factor that leads to the other sexual risk behaviors in this population. We test this hypothesis in Model 2.

Methods

MTF transgender participants were recruited from transgender health clinics in Richmond, VA (35.0%) and Washington, DC (27.4%) bars (23.1%), at a transgender community event (12.0%) and commercial sex work areas (2.6%). Participants completed an anonymous, self-administered survey and were paid an incentive of $10. All study procedures were approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked their age, birth gender, current gender, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, HIV status, recent experience with homelessness, and lifetime experience in jail.

Psychosocial variables

Participants completed the 18-item version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18, Derogatis, Citation2001). The BSI-18 contains well-validated scales assessing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatic distress that occurred over the past week. A Global Severity Index can be calculated by summing the three scales. All subscales had adequate internal consistency in this sample (α’s ranging from .83–.91); when used as an overall scale, the 18 items comprised a scale with an alpha of .95.

Participants answered six questions that assessed perceived discrimination due to gender identity in the past year. This measure was adapted from a prior measure used with MSM (Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, & Klein, Citation2010) and was internally consistent in this sample (α = .72). Another scale included items that measured negative attitudes toward oneself for being transgender (Internalized Transphobia Scale, Bockting, Miner, Robinson, Rosser, & Coleman, Citation2005); it had adequate internal consistency in this sample (α = .75). Participants also completed a 6-item version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Citation1965). This is a well-validated instrument that shows considerable stability, including in sexual minority populations (Bauermeister et al., Citation2010). This measure had adequate internal consistency in the present sample (α = .75).

Participants were asked questions concerning the frequency of use of alcohol and recreational drugs in the previous 3 months. These measures are similar to measures employed in previous research (Benotsch et al., Citation2006; Benotsch, Martin, Koester, Cejka, & Luckman, Citation2011). We used the alcohol item as a single item measure of frequency, with responses ranging from 1 = “none” to 4 = “at least every week”. We then created an index to count the number of illicit substances (other than marijuana) that participants had used (including poppers [amyl nitrate], ecstasy, methamphetamine, cocaine, ketamine, rohypnol, and heroin); (cf. Hensel, Stupiansky, Orr, & Fortenberry, Citation2011 for a review of mixed results of the relationship between marijuana use and sexual risk behavior as justification for our focus on alcohol and illicit drugs other than marijuana). Because of the highly skewed distribution of this index, we created a dichotomous variable for the descriptive analyses but used the original variable for the Mplus structural equation model (SEM) analyses because of the ability of that program's results to be robust to non-normal distributions.

HIV-related sexual behaviors

Four measures assessed sexual behaviors that may put individuals at risk. For the first three, because of the highly skewed nature of the distributions, we created dichotomous variables for our descriptive analyses but again used the original variables for Mplus SEM analyses. One question asked the number of total partners for anal and vaginal sex in the last 3 months; we created a dichotomous variable which distinguished those with three or more partners (coded “1”) in the last 3 months from those with fewer partners (coded “0”). Two other questions asked the number of times respondents had anal sex with no condom and the number of times they had vaginal sex with no condom. We summed those; we created a dichotomous variable which distinguished those having at least two occasions of unprotected vaginal or anal sex over the last 3 months (coded “1”) from those having no unprotected vaginal or anal sex (coded “0”; see Ellen, Langer, Zimmerman, Cabral, & Fichtner, Citation1996 for justification for cut points for sexual risk behaviors). Respondents were also asked how many times they had had sex in exchange for money, drugs, or a place to stay in the past 3 months. We created a dichotomous variable with categories “0” (for none) and “1” for one or more. Again for all of these variables, we used the dichotomous variable for descriptive purposes but the original continuous version of the variable in MPlus SEM analyses. Finally, we used the single item related to frequency of using a condom with a new partner, with responses ranging from 1 = “never” to 4 = “always”. For purposes of our descriptive analyses, anyone not responding “always” was classified as an inconsistent condom user.

HIV-related substance use behaviors

A critical HIV risk behavior related to substance use, sharing injection needles, was only reported by 3.3% of respondents ever in their lifetime; unfortunately this low prevalence level did not yield enough variation in this measure to be useful in our statistical analyses. Two measures we did use were single items reporting the number of times respondents had had sex after “using drugs” and after “having too much to drink” in the past 3 months. For descriptive analyses, we dichotomized them both, with one category reflecting reporting having sex one or more times using drugs or having sex one or more times after having too much to drink.

Analyses

For descriptive results and results of multiple regression analyses, missing data were estimated using multiple imputation, with the results pooled over 20 imputations. While bivariate analyses are sometimes useful, since they can lead to especially erroneous conclusions about likely causal explanations for behaviors, in this manuscript we present only multivariate analyses controlling for a variety of other, potentially confounding variables. SEMs were estimated using Mplus version 6.12. To correct for lack of multivariate normality, the mean and variance adjusted chi-square test with robust standard errors (estimator: maximum likelihood multivariate normality) was used in each SEM analysis. Indirect effects were estimated for each model using the MODEL IND command, providing standardized slope estimates for indirect effects from internalized transphobia and perceived discrimination to sexual behavior.

The final analyses attempt to explain internalized transphobia and perceived transgender-related discrimination using demographic variables (age, education, and race), homelessness in the last 12 months, lifetime jail history, HIV status, and self-esteem.

Results

Descriptive findings

As shown in , among the 117 participants, the mean age was 34.5 years (SD = 12.0). The majority of the sample was African-American (69.8%), with the remainder being White (22.4%), Asian-American (2.6%), Latino (0.9%), Native-American (0.9%), or other/mixed racial heritage (3.4%). Participants averaged just more than a high school education, were relatively poor (62.4% reported incomes of $15,000 or less per year), with over one-third being currently unemployed. A majority reported that they had been homeless during at least part of the last 12 months and that they had ever been in jail. About one-third reported that they were living with HIV.

Table 1. Demographic variables.

Prevalence of risk behaviors and substance use, as well as means on continuous variables (BSI, perceived gender-identity-based discrimination, and internalized transphobia), once again using pooled results of 20 imputations, are shown in . This table also presents the prevalence of risk behaviors that are the focus of this study (having three or more partners, two or more unprotected vaginal/anal sex acts, using condoms inconsistently, having sex while using drugs, having sex while “drinking too much” or using illicit drugs other than marijuana, all in the last 3 months), which were each between 23% and 34%. The mean value for frequency of alcohol use (from 1 = none through 4 = at least every week) was 2.18, with SD = 1.10. Mean BSI score was 11.46 (SD = 14.53). The mean number of items on which respondents had felt discriminated against because of their gender identity was 3.11 out of six items (SD = 2.7). Percentages of individual scale items to which study participants answered yes in the last 12 months (not shown in table) ranged from 14% who said they were physically assaulted or beaten up, to around 30% each for having been denied or lost a job or place to live, to 56% who said they had been insulted or made fun of. The mean score for internalized transphobia was 15.22 (SD = 5.0) on a scale with a range from 8 to 32.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for variables used in analyses.

Multivariate results

The results of the SEMs tested will be presented first, and then we will present the results of multiple regression analyses to explain internalized transphobia and perceived transgender-related discrimination.

SEMs

The hypothesized model 1 shown in included causal arrows among every possible pair of variables moving from left to right, except two-way correlational arrows among mental health, illicit substance use other than marijuana, and alcohol use, and between perceived transgender-related discrimination and internalized transphobia. One model was run with all five sexual risk behaviors entered as final outcome variables (number of sexual partners, frequency of unprotected anal or vaginal sex, frequency of sex with alcohol, frequency of sex with other drugs, and frequency of sex in exchange for money, goods, or shelter). As the frequency of sex in exchange for money, goods, or shelter was unrelated to all other variables in the model, it was removed from the picture of the final model, presented as . There we see that internalized transphobia and perceived discrimination were both related to mental health problems (β = .25, p < .01 and .33, p < .001, respectively). Perceived discrimination was also related to alcohol use (β = .30, p < .01) and marginally related to drug use (β = .19, p < .10). In turn, mental health problems were marginally related to multiple partners, alcohol use was significantly related to multiple partners (β = .53, p < .001), marginally related to unprotected sex, and significantly related to sex with drugs (β = .63, p < .001) and to sex with alcohol (β = .58, p < .001). Illicit drug use was only significantly related to sex with alcohol (β = .20, p < .05). Various fit indices suggested that the SEM fit the data quite well (χ2 = 150.42, df = 124, p = .053; CFI = .94; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .043).

The results for hypothesized model 2, which posited as a key mediator sex in exchange for money, drugs, or shelter, are presented in . As in the test of Model 1, transphobia and discrimination are related to mental health problems, but here mental health problems are unrelated to sex in exchange for money, goods, or shelter. Perceived discrimination is also significantly related to illicit drug use (β = .20, p < .05) and marginally related to alcohol use. In turn, illicit drug use and alcohol use were both related to sex in exchange for money or goods (β = .23, p < .01 and β = .44, p < .001, respectively). In the last step of this mediational model, sex in exchange for money or goods was highly related to each of the other four sexual risk behaviors, multiple partners, unprotected anal or vaginal sex, sex with alcohol, and sex with drugs, with all βs ≥ .42, all ps < .001. Various fit indices suggested that the SEM did not fit the data particularly well (χ2 = 180.20, df = 136, p = .0067; CFI = .90; TLI = .87; RMSEA = .053).

Correlates of perceived gender-related discrimination and internalized transphobia

Since both the discrimination and internalized transphobia variables were significantly related to one of the mediator variables (mental health problems), we conducted additional multiple regression analyses (using multiple imputation results, that is, the pooled results of 20 imputed datasets) to try to explain these as outcome variables. These results are shown in . Self-esteem was strongly and negatively related to internalized transphobia (β = −.51, p < .001). In addition, younger individuals reported greater internalized transphobia (β = −.17, p = .05), and those who were homeless in the last year reported marginally less transgender-based discrimination (β = −.20, p = .07). HIV status, education, jail history, and race (White vs. all other categories) were not significant predictors of either dependent variable.

Table 3. Multiple regressions for discrimination and transphobia.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to test mediational models examining some of the processes whereby perceived transgender-based discrimination and internalized transphobia are related to sexual risk behaviors. In Model 1 we proposed a two-step process: one where discrimination and internalized transphobia are related to three potential mediating variables – mental health problems, alcohol use, and illicit drug use; in turn, we proposed that those three mediating variables are related to sexual risk behaviors, including number of sexual partners, frequency of sex in exchange for money or drugs, unprotected sex, sex under the influence of illicit drugs, and sex while having had “too much to drink”, all assessed within the previous 3-month period. In sum, the results suggest that perceived discrimination and internalized transphobia are both related to mental health problems and perceived discrimination was significantly related to alcohol use. In turn, while those two predictors were significantly related to mental health problems, mental health problems were the weakest predictor of sexual risk behaviors, while alcohol use was a strong predictor of multiple sex partners and sex with alcohol and drugs and marginally related to unprotected sex. Illicit drug use was only related to sex with alcohol. Poor mental health was only marginally related to two of the risk behaviors. The risk behavior sex in exchange for money or goods was unrelated to poor mental health, alcohol use, or illicit drug use. As a result of this combination of results, neither transgender-based discrimination nor internalized transphobia had a significant indirect effect on sexual risk behaviors. The model fit the data quite well and there were indications that a key component of an HIV prevention intervention for transgender women should involve reduced alcohol use.

Model 2, while not fitting the data as well, very strongly predicts the other sexual risk behaviors. This suggests that alcohol use and the exchange of sex for money or goods might potentially both be very effective focuses of HIV prevention for this population. While this SEM yielded slightly below adequate fit statistics, the results do confirm a number of important findings from previous studies about transgender women and risk for HIV infection and risky sexual behavior. Their social environment is difficult to say the least, with very high rates of engaging in sex for money, homelessness, incarceration, unemployment, and negative thoughts about themselves. And the one relationship most consistently found in the literature was found here as well: perceived discrimination and internalized transphobia are related to mental health problems. The models were both run using robust procedures that correct for non-normality of variables. The sample size was relatively small for SEM analysis, and thus results should be viewed cautiously.

Another important limitation of the data and our analyses, of course, is that the survey data we collected were cross-sectional, and thus “causal” relationships or even the appropriate direction of relationships (were mental health problems the effect or cause of internalized transphobia, for example) must be viewed cautiously. Third, combining results from persons who know they are living with HIV and those who either are not or do not know if they are HIV positive may be combining subgroups of individuals at very different places in their risk histories. There also may be other unique characteristics related to the communities and/or venues where the current sample was recruited that may or may not apply to other locations. A variety of other variables, including childhood and recent sexual and physical victimization experiences, that are known to be significant risk factors for transgender individuals, were not measured extensively in this study. Around 8% of the MTF participants indicated they had been assaulted in the past year because of their race, and around 14% indicated they had been assaulted in the past year because of their gender identity. Responses to the latter of these questions were included as part of the gender-identity discrimination measure. Future studies should add lifetime and/or childhood sexual and physical victimization experiences to what we have measured here.

Future research should be conducted longitudinally, should include multiple sites within the USA, and should focus on individuals living with HIV, those who do not know their HIV status, and those who test regularly and know they are HIV negative, separately. Additional variables, including victimization experiences, should be measured. And while not a specific finding of this study, we continue to be convinced that the development of an evidence-based HIV prevention program for transgender women in the USA is critical, certainly such a program should address some of the structural barriers (e.g., low levels of education, low self-esteem, and high levels of unemployment and homelessness) that make engaging in risk behaviors such as exchange of sex for money or drugs more likely in this population. Focuses of HIV prevention interventions for transgender women on alcohol use and potentially (though the overall model did not prefer criteria for fit indices) on sex in exchange for money or goods, and/or on increasing employment-related skills and opportunities to yield less need for this source of income, may be useful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Baral, S. D., Poteat, T., Stromdahl, S., Wirtz, A., Guadamuz, T. E., & Beyrer, C. (2013). Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 13, 214–222. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8

- Bauermeister, J. A., Johns, M. M., Sandfort, T. G. M., Eisenberg, A., Grossman, A. H., & D'Augelli, A. R. (2010). Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1148–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y

- Bazargan, M., & Galvan, F. (2012). Perceived discrimination and depression among low-income Latina male-to-female transgender women. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 663. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-663

- Benotsch, E. G., Martin, A., Koester, S., Cejka, A., & Luckman, D. (2011). Non-medical use of prescription drugs and HIV risk behavior in gay and bisexual men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 38, 105–110. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f0bc4b

- Benotsch, E. G., Seeley, S., Mikytuck, J., Pinkerton, S. D., Nettles, C. D., & Ragsdale, K. (2006). Substance use, medications for sexual facilitation, and sexual risk behavior among traveling men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 33, 706–711. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000218862.34644.0e

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M., Robinson, B. E., Rosser, B. R. S., & Coleman, E. (2005). Transgender identity survey. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Program in Human Sexuality.

- Bogart, L. M., Wagner, G. J., Galvan, F. H., & Klein D. J. (2010). Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African American men with HIV. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 184–190. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9200-x

- Brennan, J., Kuhns, L. M., Johnson, A. K., Belzer, M., Wilson, E. C., & Garofalo, R. (2012). Syndemic theory and HIV-related risk among young transgender women: The role of multiple, co-occurring health problems and social marginalization. American Journal of Public Health, 102(9), 1751–1757. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300433

- Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., & Katz, M. (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(3), 53–69. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n03_04

- Crosby, R. A., & Pitts, N. L. (2007). Caught between different worlds: How transgendered women may be “forced” into risky sex. Journal of Sex Research, 44(1), 43–48.

- Derogatis, L. R. (2001). Brief symptom inventory 18, administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson.

- Ellen, J. M., Langer, L. M., Zimmerman, R. S., Cabral, R. J., & Fichtner, R. (1996). The link between the use of crack cocaine and the sexually transmitted diseases of a clinic population. A comparison of adolescents with adults. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 23, 511–516. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199611000-00013

- Garofalo, R., Deleon, J., Osmer, E., Doll, M., & Harper, G. W. (2006). Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(3), 230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023

- Hensel, D. J., Stupiansky, N. W., Orr, D. P., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2011). Event-level marijuana use, alcohol use, and condom use among adolescent women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 38(3), 239–243. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f422ce

- Herbst, J. H., Jacobs, E. D., Finlayson, T. J., McKleroy, V. S., Neumann, M. S., Crepaz, N., & For the HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. (2007). Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 12(1), 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3

- Lombardi, E. L., Wilchins, R. A., Priesing, D., & Malouf, D. (2001). Gender violence: Transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. Journal of Homosexuality, 42(1), 89–101. doi: 10.1300/J082v42n01_05

- MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614.

- Mathy, R. M. (2002). Transgender identity and suicidality in a nonclinical sample: Sexual orientation, psychiatric history, and compulsive behaviors. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(4), 47–65. doi: 10.1300/J056v14n04_03

- Melendez, R. M., & Pinto, R. (2007). “It's really a hard life”: Love, gender and HIV risk among male-to-female transgender persons. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9(3), 233–245. doi: 10.1080/13691050601065909

- Nemoto, T., Bödeker, B., & Iwamoto, M. (2011). Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia, and correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history of sex work. American Journal of Public Health, 101(10), 1980–1988. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197285

- Nemoto, T., Operario, D., Keatley, J., & Villegas, D. (2004). Social context of HIV risk behaviours among male-to-female transgenders of colour. AIDS Care, 16(6), 724–735. doi: 10.1080/09540120413331269567

- Operario, D., & Nemoto, T. (2010). HIV in transgender communities: Syndemic dynamics and a need for multicomponent interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 55(S2), S91–S93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbc9ec

- Purcell, D. W., Johnson, C. H., Lansky, A., Prejean, J., Stein, R., Denning, P. … Crepaz, N. (2012). Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. The Open AIDS Journal, 6(Suppl. 1), 98–107. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010098

- Reisner, S. L., Mimiaga, M. J., Bland, S., Mayer, K. H., Perkovich, B., & Safren, S. A. (2009). HIV risk and social networks among male-to-female transgender sex workers in Boston, Massachusetts. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20(5), 373–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.06.003

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Sevelius, J. M. (2013). Gender affirmation: A framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 675–689. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0216-5

- Singer, M. C., & Clair, S. (2003). Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 17, 423–441. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423

- Wilson, E. C., Garofalo, R., Harris, R. D., Herrick, A., Martinez, M., Martinez, J., & Belzer, M. (2009). Transgender female youth and sex work: HIV risk and a comparison of life factors related to engagement in sex work. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 902–913. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9508-8

- Xavier, J. M., Bobbin, M., Singer, B., & Budd, E. (2005). A needs assessment of transgendered people of color living in Washington, DC. International Journal of Transgenderism, 8(2–3), 31–47. doi: 10.1300/J485v08n02_04