ABSTRACT

Objectives

The benefits of increased physical activity for stroke survivors include improved function and mental health and wellbeing. However, less than 30% achieve recommended physical activity levels, and high levels of sedentary behaviour are reported. We developed a multifaceted behavioural intervention (and accompanying implementation plan) targeting physical activity and sedentary behaviour of stroke survivors.

Design

Intervention Mapping facilitated intervention development. Step 1 involved a systematic review, focus group discussions and a review of care pathways. Step 2 identified social cognitive determinants of behavioural change and behavioural outcomes. Step 3 linked determinants of behavioural outcomes with specific behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to target behaviours of interest. Step 4 involved intervention development informed by steps 1–3. Subsequently, an implementation plan was developed (Step 5) followed by an evaluation plan (Step 6).

Setting

Community and secondary care settings, North East England.

Participants

Stroke survivors and healthcare professionals (HCPs) working in stroke services.

Results

Systematic review findings informed selection of nine ‘promising’ BCTs (e.g. problem-solving). Focus groups with stroke survivors (n = 18) and HCPs (n = 24) identified the need for an intervention delivered throughout the rehabilitation pathway, tailored to individual needs with training for HCPs delivering the intervention. Intervention delivery was considered feasible within local stroke services. The target behaviours for the intervention were levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in adult stroke survivors. Assessment of acceptability and usability with 11 HCPs and 21 stroke survivors/relatives identified issues with self-monitoring tools and the need for a physical activity repository of local services’ and training for HCPs with feedback on intervention delivery. A feasibility study protocol was designed to evaluate the intervention.

Conclusions

A systematic development process using intervention mapping resulted in a multi-faceted evidence- and theory-informed intervention (Physical Activity Routines After Stroke – PARAS) for delivery by community stroke rehabilitation teams.

Introduction

Low levels of physical activity (Fini et al., Citation2017) and high levels of time spent sedentary (Morton et al., Citation2021) are common after stroke. Both are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, (Bailey et al., Citation2019) reduced life expectancy (Lee et al., Citation2012) and impact negatively upon mental health and well-being. Specific stroke-related impairments have been cited as specific barriers to engagement in physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour, (Nicholson et al., Citation2012) and may be why exercise preferences appear different in the stroke versus other populations (Banks et al., Citation2012). This highlights the need for bespoke interventions specifically designed for individuals with stroke.

A wealth of research demonstrates the short-term benefits of structured exercise interventions (commonly delivered in a group format) on cardiovascular risk factors (Moore et al., Citation2014) and function after stroke; (Saunders et al., Citation2020) however, longer-term benefits are under-researched. Furthermore, structured exercise interventions for stroke survivors often have little or no emphasis on everyday habitual levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviour (Saunders et al., Citation2020) and often do not focus on developing stroke survivors’ self-management skills, which prevents them from making sustained changes in behaviour beyond the intervention period (Morris et al., Citation2015).

The small number of randomised controlled trials (n = 9) conducted that target long-term free-living physical activity after stroke show promise (Moore et al., Citation2018). However, limitations in methodological quality and intervention design prevent any robust conclusions in this field (Moore et al., Citation2018). Specifically, they lack adequate descriptions of intervention content (Hoffmann et al., Citation2014) and fidelity assessment, (Bellg et al., Citation2004) which restricts replicability and prevents successful implementation. There is also a dearth of interventions targeting reductions in sedentary behaviour alongside increasing physical activity of stroke survivors.

Furthermore, few interventions targeting physical activity and sedentary behaviour post-stroke have been developed with reference to theory, systematically developed or robustly evaluated (Moore et al., Citation2018). The application of health behaviour change theory is critically important to gain a thorough understanding of the antecedents of the behaviours of interest, to develop targeted and effective interventions (Nicholson et al., Citation2012, Citation2014). Theory based interventions have been shown to significantly impact upon physical activity behaviour (Gourlan et al., Citation2016). Intervention Mapping is a practical framework for systematic, evidence and theory-based planning for behavioural change (Kok, Citation2014) and has been particularly effective in the context of healthcare, (Fernandez et al., Citation2019; Hurley et al., Citation2016) including informing the development of interventions targeting physical activity behaviour (Brug, Oenema, & Ferreira, Citation2005).

Using Intervention Mapping, our aim was to systematically develop an evidence-and theory-informed behavioural intervention targeting long-term, free-living physical activity and sedentary behaviour for integration into the stroke rehabilitation care pathway.

Methods

Overview of development process

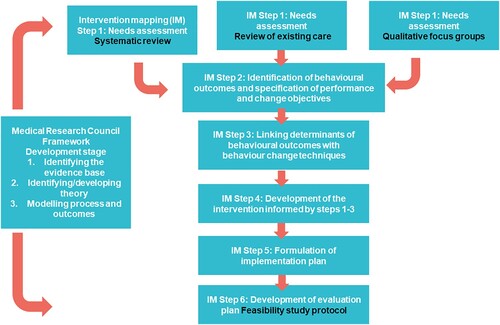

Our intervention was developed with reference to the Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions. Complex interventions are those that contain several interacting components. The current intervention was defined as complex given the complex needs of the target population (i.e. stroke impairment) and the challenges associated with and influencing behavioural change. These complexities present unique problems for evaluation (Craig et al., Citation2013). Alongside the MRC framework, we utilised Intervention Mapping to inform intervention content, delivery, implementation and evaluation (Bartholomew, Parcel, Kok, Gottlieb, & Fernandez, Citation2011). Details of how the six steps of the implementation mapping intervention development approach described by (Bartholomew et al., Citation2011) were applied are described in the methods and summarised in .

Methods and results

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for the development workshops with stroke survivors and healthcare professionals was givenon the 24/10/2016 from the Faculty of Medical Science ethics committee at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K. (reference number 01211/2016). Fully informed written consent was gained from all participants who took part in the study.

Step 1: needs assessment

To enable the development and implementation of a tailored intervention to effectively target physical activity and sedentary behaviour after stroke, we conducted a needs assessment. To do this, we first conducted a systematic review of the literature (Moore et al., Citation2018) and secondly consulted with healthcare professionals (HCPs) and stroke survivors and identified local community stroke care pathways (where they existed) to determine how a new intervention could integrate with and/or complement current pathways.

Systematic review

A previously published systematic review of randomised controlled trials was undertaken to explore the characteristics and promise of existing intervention components targeting free-living physical activity and/or sedentary behaviour after stroke (Moore et al., Citation2018).

Key findings of systematic review

All nine studies (N = 719 participants) included in the systematic review targeted physical activity behaviour and none targeted sedentary behaviour. Six of the interventions evaluated were rated as promising – i.e. interventions with statistically significant between- or within-group improvements in outcomes greater than those of the control or comparator group (Gardner et al., Citation2016). All of these interventions involved an element of supervised support that was tailored to individual needs. Both face-to-face and telephone contact were identified as promising modes of intervention delivery. The number of contacts for promising interventions ranged from a single contact to 36 contacts, with the duration of interventions ranging from one single contact to twelve consecutive weeks. Nine promising behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were identified with reference to the BCT Taxonomy V1 (Michie et al., Citation2013) and considered for inclusion in our intervention: information about health consequences; information about social and environmental consequences; goal-setting behaviour; problem-solving; action planning; feedback on behaviour; biofeedback; social support unspecified; and credible source.

Although the systematic review identified some promising interventions and associated components, it highlighted the need for the development of a novel intervention that addressed previous methodological and theoretical limitations and that incorporated stroke survivor and HCP preferences.

Qualitative focus group discussions

A series of interactive focus group discussions were conducted with stroke survivors and HCPs. Stroke survivors were recruited by advert within the North East of England. Eligibility criteria were broad and included stroke diagnosis, community dwelling and able to access and attend focus group discussions. HCPs from five NHS North East England stroke rehabilitation services were invited to take part in a focus group discussion. Eligibility criteria for HCPs were: Qualified physiotherapist, technical instructor, physiotherapy assistant; working in the NHS; currently working in stroke rehabilitation; and able to access and attend the focus group. Participants were recruited until it was felt that data saturation had been reached. The overall aim of the focus groups was to identify determinants of behavioural change for both stroke survivors and HCPs and to explore the barriers and enablers to engage in long-term physical activity and reduction of sedentary behaviour. A secondary aim was to add specific context to the findings of our systematic review, and to explore preferences around the intervention components identified by the systematic review. Focus group discussions were conducted in person, audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Topic guides were developed using the COM-B model exploring how capability, opportunity and motivation interact to influence behaviour. A presentation explaining the overall aim of the focus group, definitions of physical activity and sedentary behaviour and the benefits of post-stroke activity was delivered at the start of each focus group. Open-ended questions about pre- and post-stroke activity levels, and barriers and enablers to engaging in physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour after stroke were subsequently explored with stroke survivors. HCPs were asked about motivators, barriers and facilitators to supporting stroke survivors to be more physically active and reduce sedentary behaviour. Each focus group lasted approximately one and a half hours.

Data were analysed using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (Cane, O’Connor, & Michie, Citation2012) to facilitate an exploration of behavioural determinants likely to predict and impact upon behaviour and behavioural change. Three researchers (SAM, a clinical academic stroke physiotherapist, LA, a chartered health psychologist with expertise in health behaviour change and qualitative research methods and a master’s degree student) read, re-read and analysed transcripts following the conduct of each focus group discussion. Any unsubstantiated issues or points were explored further during subsequent group discussions (i.e. topic guides were revised accordingly). The skill mix of the researchers ensured appropriate questions were asked and responses were further probed for comprehensive understanding. Analyses of the data involved assigning text segments to one or more domains of the TDF and generating themes within each domain. All focus group transcripts with HCPs and stroke survivors were coded and analysed by hand, i.e. no qualitative software was used. Common themes across the stroke survivors and HCPs were subsequently established with regular meetings held between researchers to discuss independent analyses and gain consensus.

Findings of focus groups discussions

Eighteen stroke survivors (11 male, median age 64 years, interquartile range (IQR) 15, time since stroke 52 months, IQR 39, 15 ambulatory (with or without walking aid), 3 wheelchair users) and 24 HCPs (physiotherapists n = 14, technical instructors n = 8, physiotherapy assistants n = 2, working on the ward n = 5, working across ward and community n = 3, working in the community/outpatients n = 16) participated across 7 focus groups. All 14 of the theoretical domains of the TDF were identified from the data generated from stroke survivor focus groups. The most saliant domains were ‘environmental context and resources’, ‘beliefs about consequences’ and ‘beliefs about capabilities’ (Stroke survivor TDF domains themes with related change objectives are presented in , Step 2).

Table 1. Stroke survivor behavioural outcomes, performance objectives and change objectives related to theoretical domains and associated themes identified from focus group data.

Data generated from HCP focus groups identified seven theoretical domains: ‘knowledge’, ‘skills’, ‘social/professional role and identity’, ‘belief about consequences’, ‘beliefs about capabilities’, ‘reinforcement’ and ‘environmental context and resources’. The most saliant domains that emerged from the data were ‘environmental context and resources’ and ‘skills’ (HCP TDF domains themes with related change objectives are presented in , Step 2).

Table 2. Healthcare professional behavioural outcomes, performance objectives and change objectives alongside theoretical domains and associated themes identified from focus group data.

Although the aim of the focus group discussions with stroke survivors was to explore the determinants of behavioural change in relation to physical activity and sedentary behaviour, participants focused their discussions on physical activity highlighting a potential lack of understanding and awareness about sedentary behaviour and the role it plays in stroke rehabilitation. As such, a need for the development of an intervention to target sedentary behaviour as well as physical activity behaviour was identified.

Lack of sustainable physical activity options was identified as a key barrier by stroke survivors with a lack of timely information and long-term support also reported. Enablers to increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour were identifying meaningful, accessible, sustainable activities with social support and developing skills for self-monitoring physical activity and well-being, e.g. linking a change to behaviours with improvements in activities of daily living were considered vitally important. HCPs also identified environmental context and access to resources as barriers to promoting physical activity and reducing sedentary behaviour, as well as a lack of skills to effectively support behaviour change, particularly when stroke survivors presented significant barriers and challenges.

Exploration of intervention opportunities within existing pathways

To identify current stroke rehabilitation services and explore potential for delivering the intervention within existing pathways, a questionnaire was sent to North East England community stroke teams. Questions explored current and future staffing, current service provision, and potential for participation in a future intervention study. Community stroke services at seven North East NHS Trusts were considered for inclusion. Four of these Trusts were already involved in another rehabilitation study led by the research team; therefore it was agreed that they would not be approached to reduce burden.

Key findings of exploration of existing pathways

Participating trusts did not report any specific interventions or resources already in place to target free-living physical activity and sedentary behaviour and reported having an interest, capacity and manager agreement to take part in a future feasibility study (Appendix A).

Key findings of needs assessment

The needs assessment highlighted that physical activity and sedentary behaviour are not adequately addressed post-stroke and HCPs do not feel equipped to target these behaviours effectively. Findings indicated that the intervention should be adaptable to individual needs, circumstances and preferences. A supported self-management approach was considered most appropriate to target these requirements. Mapping of existing stroke rehabilitation pathways revealed that there was a potential to incorporate a physical activity and sedentary behaviour intervention and training for HCP into current practice.

Step 2: identification of behavioural outcomes, and specification of performance and change objectives

The needs assessment conducted in Step 1 identified the behaviours to target with our intervention: Stroke survivors – physical activity and sedentary behaviour, HCPs – consultation behaviour including knowledge about physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the context of stroke and skills to effectively target behaviour change. The two behavioural outcomes of the PARAS intervention, related performance objectives (tasks required) and change objectives (i.e. aspects of behaviour individuals are required to learn, do or change) that need to be accomplished by stroke survivors and HCPs in order to achieve the behavioural outcomes and performance objectives were developed with reference to the TDF domains and domain-specific themes identified in Step 1. These are described in and .

Step 3: selection of theory-based intervention content

Selection of the theories/models to underpin the behaviour change intervention were informed by the findings of steps 1 and 2.

Theoretical underpinning of the stroke survivor component of the intervention

Two theories were selected to underpin the stroke survivor component of the multifaceted intervention, the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, Strecher, & Becker, Citation1998) and Self-Regulation Theory (Leventhal, Brissette, & Leventhal, Citation1997). The Health Belief Model assumes an individual’s belief in the personal threat of an illness together with their belief that the effectiveness of a health behaviour or action will determine whether they change their behaviour (or not). Self-regulation Theory involves guiding an individual’s own thoughts, behaviours and feelings to reach the goals. It was felt that these two models/theories in combination were appropriate with specific reference to the findings generated by the qualitative research.

Step 1 informed theory selection to target individual perceptions of stroke and stroke recurrence including the use and perceived benefits and disadvantages of physical activity and inactivity. It was felt that the selected model was appropriate particularly around challenging beliefs about the consequences of physical activity/inactivity and as such formulate reasons/intentions for engaging in physical activity.

Self-Regulation Theory assumes that behaviour is goal-directed or purposive. Findings from our systematic review and focus group discussions supported the need for specific strategies to target volition as well as motivation in recognition that maintenance of physical activity for stroke survivors can be particularly challenging given the level of cognitive and physical effort required. Furthermore, inclusion of several specific BCTs that target self-regulation e.g. goal-setting behaviour; problem-solving; action planning; feedback on behaviour were identified from the systematic review as promising.

Behaviour change techniques are the irreducible active ingredients of interventions targeting behaviour change, and are useful to inform, describe, deliver and evaluate behaviour change interventions as well as operationalising underpinning theory (Michie et al., Citation2015). TDF domains were identified from the data generated from stroke survivor focus group discussions and BCTs were selected with reference to those domains, supported by evidence from the systematic review (i.e. BCTs identified by the review as promising). When discrepancies occurred between the findings of the qualitative study and the systematic review, research team discussion led to a consensus agreement in terms of inclusion/exclusion of specific BCTs. The outcome of the decision-making process is summarised in which also describes theoretical constructs targeted and intervention components which were further developed in Step 4.

Table 3. Theoretical intervention mapping targeting physical activity and sedentary behaviour of stroke survivors.

Theoretical underpinning of the HCP component of the PARAS intervention

Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, Citation1986) was selected to underpin the HCP component of the multifaceted intervention. This theory was considered appropriate with reference to the findings of the focus group discussions with HCPs during Step 1. For example, HCPs highlighted the need for specific knowledge and skills development training that would enable them to attain specific practice-related goals. These included promoting and supporting an increase in physical activity to enable improvements in specific functional outcomes of patients. Social Cognitive Theory provides specific examples of evidence-based strategies for translating motivation/intentions into action/behaviour in HCPs through the use of modelling to increase skills and self-efficacy (Godin et al., Citation2008). Focus group data supported the need for modelling to facilitate skill acquisition and target beliefs about capabilities.

The selection of BCTs incorporated into the HCP component of the intervention was also informed by findings from the qualitative focus group discussions conducted as part of Step 1. The decision-making process is summarised in which also describes theoretical constructs targeted and intervention components.

Table 4. Theoretical intervention mapping targeting healthcare professional consultation behaviour.

Step 4: development of the PARAS intervention

Following the intervention mapping exercise outlined in Step 3, a prototype intervention was developed and presented to stroke survivors and HCPs for feedback during workshops and by questionnaire to inform further iterations.

Stroke survivor consultation workshops

We conducted three consultation workshops with stroke survivors (n = 21) recruited from local stroke community groups with an aim to elicit views on intervention content, form and mode of delivery. Examples of potential intervention tools (workbook, physical activity diary, information on apps accessible on mobile phone, pedometers) were circulated during workshops to generate discussion and obtain feedback. During the first two workshops (n = 13 stroke survivors) a feedback form was used to collate opinions/information (Appendix B). To ensure the intervention could be used by stroke survivors with aphasia (impairment of language), the third workshop was conducted with the North East Aphasia Research User Group (https://www.neta.org.uk/) (n = 8 stroke survivors). This workshop was delivered using strategies to enable understanding of language and verbal rather than written feedback was collated. Alongside review of the intervention content and tools, prototype aphasia friendly consent and patient information sheets were reviewed by the group for use during a future feasibility study (Appendix C and D). All three workshops were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to facilitate the intervention development processes.

Key findings of stroke survivor consultation workshops

A detailed overview of workshop findings is provided in Appendix E. In summary, participants reported a preference for the intervention to be supported by HCPs and delivered either at home or in a community outpatient setting. There was a preference for at least two sessions, with the first session delivered face-to-face and subsequent sessions delivered either face-to-face or by telephone. The majority (>75%) of stroke survivors either strongly agreed or agreed that the prototype intervention workbook and physical activity diaries were well organised and easy to use. Eight commercially available pedometers that have been used successfully in other physical activity studies (Carroll et al., Citation2012; Harris et al., Citation2017; Sullivan et al., Citation2014) were presented to stroke survivors during the workshop. The CSX 301S 3D simple pedometer was considered the most appropriate and was the only pedometer to be voted by all participants as easy to use and something they would be likely to use to facilitate self-monitoring.

HCP feedback

An online questionnaire was completed by four North East community stroke teams (n = 11 HCPs) to elicit feedback on the prototype intervention. These teams had previously expressed an interest in reviewing the intervention and taking part in a future feasibility study.

Key findings of HCP feedback

Feedback in relation to the intervention design and content was largely positive (Appendix E). Team 2, 3 and 4 strongly agreed or agreed with the suitability of the intervention, tools and mode of delivery. Team 2 were uncertain about whether they could deliver the intervention within their team because they reported discharging patients to other rehabilitation services (i.e. follow-up reviews might not be possible to review goals, provide feedback and discuss problem solving).

Team 1 were concerned about whether their patients would be suitable for the intervention. They perceived the intervention to be for ‘high functioning’ patients who may have been discharged from their service before undertaking the intervention. A further meeting was held with Team 1 to provide more detail that could enable a more informed decision regarding potential participation in a feasibility study of the intervention (e.g. to further emphasise that the intervention was not specifically aimed at ‘high functioning’ patients and could be tailored to individual needs and preferences). Following this meeting, Team 1 agreed they could potentially deliver the intervention.

Step 5: formulation of an implementation plan

An important consideration for the implementation plan was that it targeted all three pillars of high-quality care: patient experience, safety and effectiveness (Darzi, Citation2018). To increase the likelihood of implementation, the APEASE criterion: affordability; practicability; effectiveness and cost-effectiveness; acceptability; side effects/safety and equity (Michie, Atkins, & West, Citation2014) were applied to the intervention design. The final components of the intervention, named Physical Activity Routines After Stroke ‘PARAS’, can be viewed in . The PARAS intervention targets stroke survivor physical activity and sedentary behaviour via a supported self-management programme and HCP consultation behaviour via a training programme. The stroke survivor and HCP components of the intervention are described in using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework. also outlines how the APEASE criterion informed selectin of each intervention component.

Table 5. PARAS intervention components described with the Template for intervention Description and replication (TIDieR) and APEASE criteria considered in development phase.

Step 6: development of an evaluation plan

To further develop and optimise the intervention within community stroke settings, in accordance with the MRC framework, the next step was to develop an intervention evaluation plan. Therefore, a protocol for a study determining the feasibility of the PARAS intervention, was developed (Moore et al., Citation2020). The feasibility study is registered on the ISRCTN website (Trial identifier: ISRCTN35516780, date of registration: 24/10/2018 URL http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN35516780).

Discussion

Low levels of physical activity and high levels of sedentary behaviour are common following stroke (Moore et al., Citation2013) and are associated with cardiovascular health, mental health and quality of life (Moore et al., Citation2014). An intervention development process, informed by the MRC guidelines for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, (Craig et al., Citation2013) using Intervention Mapping as a framework (Bartholomew et al., Citation2011) was undertaken to target physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the context of stroke rehabilitation as part of the routine care pathway in acknowledgement that stroke survivors have specific information and support requirements. An initial needs assessment identified a lack of effective theory-and-evidence informed interventions targeting long-term free-living physical and sedentary behaviour in stroke survivors (Moore et al., Citation2018) and our qualitative work identified the need to develop a timely, sustainable person-centred supported self-management intervention to address this problem.

Historically, structured exercise has been the most common mode of targeting physical activity after stroke (Saunders et al., Citation2020). Although structured exercise can lead to short-term changes in function, how this mode of delivery impacts on long-term health and well-being has not been established. Perhaps more importantly, our qualitative research mirrored previous findings indicating that many barriers exist to this approach in terms of implementation e.g. resources, training, access and costs that make it unsustainable for many stroke survivors (Nicholson et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, structured exercise does not account for individual physical activity needs and preferences. Our qualitative work indicated that stroke survivors wish to partake in activities that provide meaning to their lives and allow them to recapture activities they engaged in prior to experiencing a stroke. This may be through structured exercise, but more commonly reported was engagement in day-to-day activities such as washing the car, shopping, or playing with grandchildren. This finding supports previous qualitative work undertaken in stroke (Nicholson et al., Citation2012). It was, therefore, important that the intervention developed was person-centred rather than ‘one size fits all’. The implementation mapping process led to the development of a supported self-management intervention delivered at an appropriate time point within the rehabilitation pathway, tailored to individual needs with training for HCPs delivering the intervention. This training was designed to provide HCPs with specific evidence-informed education about physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the context of stroke, and competency in using BCTs to target problem solving for example.

There is an expectation within self-management in stroke and at a governmental level that person-held experience is incorporated into healthcare intervention design (Kulnik et al., Citation2019). Early engagement with stroke survivors and HCPs during the intervention development process was a key strength of this study, which can potentially enable future implementation, with those taking part in the process becoming champions for the intervention (Clarke et al., Citation2017). Aphasia is a common communication problem affecting approximately one-third of stroke survivors (Engelter et al., Citation2006). Engaging with patients with aphasia during co-design is complex and as a result is often not undertaken leading to interventions that are inappropriate for this population and leaving a sub-population unsupported. In previous self-management interventions in stroke, up to 46% of studies have excluded individuals with aphasia limiting extrapolation of findings to large numbers of stroke survivors (Brady, Fredrick, & Williams, Citation2013). One of the strengths of our intervention development process which may enable implementation was engagement with a group of stroke survivors with aphasia, and the incorporation of their views into the intervention design.

Alongside the incorporation of user views, another strength of the study was the use of the APEASE criteria to consider the social context of intervention delivery to facilitate implementation (Michie et al., Citation2014). Our systematic review highlighted that the majority of RCTs and pilot studies in this field have been led by research teams, not clinicians, and attempts have not been made to embed testing within existing clinical pathways and settings (English et al., Citation2016; Jones et al., Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2018; Preston et al., Citation2017). The PARAS intervention was developed with implementation into the clinical care pathway in mind, because implementation of research findings into rehabilitation settings has demonstrated previously to be slow, with evidence often not influencing practice (Morris et al., Citation2020).

Our needs assessment highlighted that the intervention should be multi-faceted, targeting both the behaviour of the stroke survivors and the behaviour of the HCPs providing support. This is a novel approach in this field, where most interventions focus exclusively on stroke survivors and those providing interventions being expected to do so without training or support. Our qualitative work indicated that stroke survivors have a preference to be supported by a HCP, therefore it was important to consider behavioural change counselling strategies for use by HCPs to enable this. It could be argued that HCPs already have skills to support these long-term behavioural changes, however, observational data on habitual physical activity and sedentary behaviour post-stroke (Fini et al., Citation2017) indicates the contrary and the findings of our qualitative study highlighted the need for training in this area. Previous research further suggests that perceptions on physical activity post-stroke vary between stroke survivors, informal carers and HCPs, (Morris et al., Citation2015) therefore training on how to deliver person-centred support to enable meaningful engagement in physical activity, which is more likely to result in long-term change, may be required.

It is anticipated that the application of complex intervention development processes will increase the likelihood of future effectiveness and implementation of the intervention. However, several limitations associated with our developmental process should be acknowledged. Stroke survivors that took part in the initial qualitative focus group discussions were required to travel, meaning only those who had access to transport or were mobile could attend. In addition, invitations to participants in these groups were advertised mainly at local stroke groups or patient carer panels which may have limited representation of a general stroke population. Although we advertised for informal carers to attend the focus groups, only three took part and information contributed was minimal and did not enable formal analyses. Therefore, this limited our understanding from a carer perspective. The HCPs recruited may not have been representative as they were self-selected limiting generalisability. The majority were physiotherapists and assistants, rather than from the broad range of disciplines who may also have been suitable to deliver the intervention e.g. nurses, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, exercise on referral/fitness instructors.

Conclusions

Effectively targeting complex behaviours such as physical activity and sedentary behaviour post-stroke requires systematic and iterative development of evidence and theory informed interventions. Alongside effectiveness, the likelihood of adoption, implementation and sustainability of an intervention should also be considered during the development process. We have presented the development of an intervention, grounded in stroke survivor and service provider perspectives that targets long-term habitual physical activity and sedentary behaviour post-stroke. Throughout the developmental process, there was active engagement of stroke survivors and HCPs to increase likelihood of the acceptability and effectiveness of the intervention and long-term implementation. The PARAS intervention is currently being testing in three North East community stroke services and the results of this feasibility study will further inform development. Following the MRC guidelines for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, the intervention will be further evaluated assessing efficacy, cost-effectiveness and process.

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (4 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following for their contribution:

Stroke survivors, their carers/relatives and health care professionals who took part in the study

North East Aphasia Research Group (ARUG).

The NIHR North East Stroke Specialty Group Patient and Carer Panel for feedback on study development.

Staff at Newcastle University and Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust who have contributed to the project: Patricia McCue, Norman Marillier, Liz Costigan.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bailey, D. P., Hewson, D. J., Champion, R. B. (2019). Sitting time and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(3), 408–416.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Stanford: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Banks, G., et al. (2012). Exercise preferences are different after stroke. Stroke Research and Treatment, 2012, 890946.

- Bartholomew, L. K., Parcel, G. S., Kok, G., Gottlieb, N. H., & Fernandez, M. E. (2011). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bellg, A. J., et al. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443–451.

- Brady, M. C., Fredrick, A., & Williams, B. (2013). People with aphasia: Capacity to consent, research participation and intervention inequalities. International Journal of Stroke, 8(3), 193–196.

- Brug, J., Oenema, A., & Ferreira, I. (2005). Theory, evidence and Intervention Mapping to improve behavior nutrition and physical activity interventions. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2(1), 2.

- Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 37.

- Carroll, S. L., et al. (2012). The use of pedometers in stroke survivors: Are they feasible and how well do they detect steps? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(3), 466–470.

- Clarke, D., et al. (2017). What outcomes are associated with developing and implementing co-produced interventions in acute healthcare settings? A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Open, 7(7), e014650.

- Craig, P., et al. (2013). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(5), 587–592.

- Darzi, A. (2018). The lord Darzi review of health and care: Interim report. London: Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR).

- Engelter, S. T., et al. (2006). Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: Incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke, 37(6), 1379–1384.

- English, C., et al. (2016). Reducing sitting time after stroke: A phase II safety and feasibility Randomized Controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(2), 273–280.

- Fernandez, M. E., et al. (2019). Intervention mapping: Theory- and evidence-based Health Promotion Program planning: Perspective and examples. Frontiers in Public Health, 7(209).

- Fini, N. A., et al. (2017). How physically active are people following stroke? Systematic review and quantitative synthesis. Physical Therapy, 97(7), 707–717.

- Gardner, B., et al. (2016). How to reduce sitting time? A review of behaviour change strategies used in sedentary behaviour reduction interventions among adults. Health Psychology Review, 10(1), 89–112.

- Godin, G., et al. (2008). Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: A systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implementation Science, 3(1), 36.

- Gourlan, M., et al. (2016). Efficacy of theory-based interventions to promote physical activity. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Health Psychology Review, 10(1), 50–66.

- Harris, T., et al. (2017). Effect of a primary care walking intervention with and without nurse support on physical activity levels in 45- to 75-year-olds: The pedometer and consultation evaluation (PACE-UP) cluster randomised clinical trial. PLoS Medicine, 14(1), e1002210–e1002210.

- Hoffmann, T. C., et al. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 348, g1687.

- Hurley, D. A., et al. (2016). Using intervention mapping to develop a theory-driven, group-based complex intervention to support self-management of osteoarthritis and low back pain (SOLAS). Implementation Science, 11(1), 56.

- Jones, T. M., et al. (2016). Mymoves program: Feasibility and Acceptability study of a remotely delivered self-management program for increasing physical activity among adults with acquired brain injury living in the community. Physical Therapy, 96(12), 1982–1993.

- Kok, G. (2014). A practical guide to effective behavior change: How to apply theory- and evidence-based behavior change methods in an intervention. The European Health Psychologist, 16, 156–170.

- Kulnik, S. T., et al. (2019). A gift from experience: Co-production and co-design in stroke and self-management. Design for Health, 3(1), 98–118.

- Lee, I. M., et al. (2012). Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet, 380(9838), 219–229.

- Leventhal, H., Brissette, I., & Leventhal, E. A. (1997). The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In L. D. Cameron & H. Leventhal (Eds.), The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour (pp. 935–946). London: Routledge.

- Michie, S., et al. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95.

- Michie, S., et al. (2015). Behaviour change techniques: The development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technology Assessment, 19(99), 1–188.

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing.

- Moore, S. A., et al. (2013). Physical activity, sedentary behaviour and metabolic control following stroke: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. PLOS ONE, 8(1), e55263.

- Moore, S. A., et al. (2014). Effects of community exercise therapy on metabolic, brain, physical, and cognitive function following stroke: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 29(7), 623–635.

- Moore, S. A., et al. (2018). How should long-term free-living physical activity be targeted after stroke? A systematic review and narrative synthesis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1), 100.

- Moore, S. A., et al. (2020). A feasibility, acceptability and fidelity study of a multifaceted behaviour change intervention targeting free-living physical activity and sedentary behaviour in community dwelling adult stroke survivors. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 6(1), 58.

- Morris, J. H., et al. (2015). From physical and functional to continuity with pre-stroke self and participation in valued activities: A qualitative exploration of stroke survivors’, carers’ and physiotherapists’ perceptions of physical activity after stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(1), 64–77.

- Morris, J. H., et al. (2020). Implementation in rehabilitation: A roadmap for practitioners and researchers. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(22), 3265–3274.

- Morton, S., et al. (2021). A qualitative study of sedentary behaviours in stroke survivors: Non-participant observations and interviews with stroke service staff in stroke units and community services. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–10.

- Nicholson, S., et al. (2012). A systematic review of perceived barriers and motivators to physical activity after stroke. International Journal of Stroke, 8(5), 357–364.

- Nicholson, S. L., et al. (2014). A qualitative theory guided analysis of stroke survivors’ perceived barriers and facilitators to physical activity. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(22), 1857–1868.

- Preston, E., et al. (2017). Promoting physical activity after stroke via self-management: A feasibility study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 24(5), 353–360.

- Rosenstock, I. M., Strecher, V. J., & Becker, M. H. (1998). Social learning theory and the Health Belief model. Health Education Quarterly, 15(2), 175–183.

- Saunders, D. H., et al. (2020). Physical fitness training for stroke patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3.

- Sullivan, J. E., et al. (2014). Feasibility and outcomes of a community-based, pedometer-monitored walking program in chronic stroke: A pilot study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 21(2), 101–110.