ABSTRACT

Background

Research supports development of informal, community-based suicide prevention interventions that can be tailored to suit men’s unmet needs. The James’ Place model (JPM) is a community-based, clinical suicide prevention intervention for men experiencing suicidal crisis. Evidence supports the efficacy of the JPM and there are plans to expand to additional sites across the UK. This study evaluates therapists perceived acceptability of the JPM, and if fidelity to the planned delivery of the model is maintained within therapeutic practice.

Method

A mixed-methods design was used. Descriptive analyses of 30 completed intervention cases were examined to review fidelity of the model against the intervention delivery plan. Eight therapists took part in semi-structured interviews between November 2021 and March 2022 exploring the perceived acceptability, and barriers and facilitators to delivering the JPM.

Results

Descriptive analyses of James’ Place audit notes revealed high levels of adherence to the JPM amongst therapists, but highlighted components of the model needed to be tailored according to individual men’s needs. Thematic analysis led to the development of five themes. The first theme, therapeutic environment highlighted importance of the therapy setting. The second theme identified was specialised suicide prevention training in the JPM that facilitated therapists understanding and expertise. The third theme identified was therapy engagement which discusses men’s engagement in therapy. The fourth theme, person-centred care related to adaptation of delivery of JPM components. The final theme, adapting the JPM to individual needs describes tailoring of the JPM by therapists to be responsive to individual men’s needs.

Conclusion

The findings evidence therapist’s acceptability and their moderate adherence to the JPM. Flexibility in delivery of the JPM enables adaptation of the model and co-production of therapy to meet men’s needs. Implications for clinical practice are discussed.

Introduction

Suicide is a global public health concern accounting for over 700,000 deaths worldwide (WHO, Citation2021). While suicide affects both men and women, higher rates of suicide among men are recorded worldwide (Naghavi, Citation2019), with men accounting for three quarters (3925 deaths) of the 5224 suicide deaths recorded in England and Wales in 2020 (ONS, Citation2021). Existing research evidence suggests pressure to conform to socialised traditional masculine ideals such as self-reliance, stoicism, and emotional self-control, hamper help-seeking among men experiencing psychological distress (Canetto and Sakinofsky, Citation1998 ; Pirkis et al., Citation2017; Seidler et al., Citation2016). Subsequently, men may engage in avoidant coping strategies, including substance misuse (e.g. alcohol and drugs), denial, aggressive, and risky behaviour to regain a perceived sense of control (Eggenberger et al., Citation2023; O'Gorman et al., Citation2022; Seidler et al., Citation2016, Citation2021).

Recent systematic review findings of research spanning 20 years found traditional norms of masculinity implicated in suicide risk among men in 96% of included studies (Bennett et al., Citation2023). Bennett et al. (Citation2023) posit a 3 ‘D’ risk model to account for the relationship between traditional masculine ideals and increased suicide risk among men. Accordingly, the emergence of increasing psychological pain and suicide risk occurs from reciprocal interaction of denial, disconnection, and dysregulation within three core psychological areas of emotions (emotional suppression), self (failure to achieve standards of male success), and interpersonal connections (undermined social and relational needs); which in turn reflect individual expression of traditional masculine norms (Bennett et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, accumulating psychological pain may become amplified by distal and proximal risk factors an individual may be susceptible to (Bennett et al., Citation2023).

Poor help-seeking due to various barriers, including shame and fear of mental illness diagnosis, is often blamed for men’s low engagement with mental health services (Cleary, Citation2012; Luoma et al., Citation2002; Rasmussen et al., Citation2018). Arguably, this suggests that suicide prevention support typically offered by mental health support services is not meeting the needs and preferences of men experiencing suicidal crisis. This highlights an issue with the type of support suicide prevention services traditionally offer men experiencing suicidal crisis. Research has shown that men experiencing suicidal crisis can find it difficult to discuss their emotions as it conflicts with their masculine status (Cleary, Citation2012; River & Flood, Citation2021). This has led to calls for targeted suicide prevention services that are informal, community-based and ‘men-friendly’ (Oliffe et al., Citation2020; Seidler et al., Citation2018; Stiawa et al., Citation2020; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019), which consider the content and structural context in which men disclose their suicidal distress (Chandler, Citation2021). Research has also advocated the need to explore men’s experiences of suicide and to consult community stakeholders to understand and build capacity within the design and delivery of suicide prevention services to meet men’s needs (Saini et al., Citation2022; Trail et al., Citation2021).

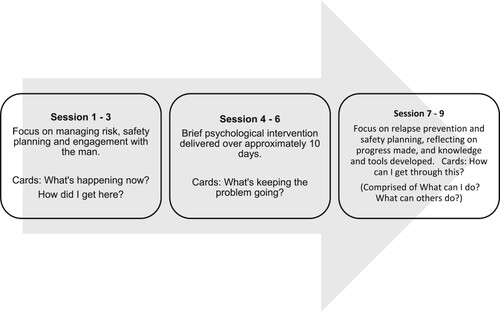

Established in 2018, James’ Place (JP) is the UK’s first community-based therapeutic suicide prevention centre for men. JP strives to redress issues of poor help-seeking and engagement among men experiencing suicidal crisis by facilitating rapid access to a brief clinical intervention called the JP Model (JPM). This is delivered within a community therapeutic setting by therapists trained to deliver the JPM and is adapted to suit individual men’s needs. The JPM is underpinned by three theories of suicide each promoting safety planning and working with the individual to co-produce suicide prevention strategies; namely the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner et al., Citation2009), the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) (Jobes, Citation2012), and the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Theory of Suicide (IMV) (O'Connor, Citation2011; O'Connor & Kirtley, Citation2018). The JPM is delivered by suicide prevention therapists and involves nine sessions structured into three stages, each composed of three sessions. shows how the JPM is typically delivered. Sessions one to three focus upon managing risk, ensuring the man is engaged in therapy and the lay your cards on the table (LYCT) component of the intervention are introduced to help the man to articulate their suicidal distress; sessions four to six involve delivery of brief psychological interventions; and sessions seven to nine focus on relapse prevention and creation of an individualised, detailed safety plan. Further details of the JPM can be found elsewhere (Hanlon et al., Citation2022; Saini et al., Citation2019, Citation2020). Several studies have shown the JPM significantly reduces distress as demonstrated by a clinically significant reduction in Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) scores (Chopra et al., Citation2022; Saini et al., Citation2020, Citation2022; Saini, Chopra, Hanlon, & Boland Citation2021; Saini, Chopra, Hanlon, Boland, & O’Donoghue Citation2021).

Figure 1. Specification of the James’ Place model. Three boxes showing the structure of JPM delivery in three stages each comprised of three sessions, and descriptions of the corresponding focus of each stage and LYCT delivered.

Fidelity refers to the extent an intervention is delivered as planned (Carroll et al., Citation2007; Gearing et al., Citation2011). Assessment of fidelity determines whether intervention outcomes can be attributed to intervention content and components, rather than unaccounted factors, such as variations in implementation and/or omission of intervention components (Borrelli, Citation2011). Currently, there are JP centres in Liverpool and London, with plans for future expansion of the service. Expansion of JP will inherently mean more therapists will be involved in delivering the JPM. This, in addition to the adaptable nature of the JPM, could potentially risk deviations away from delivery of the model as planned. It is pertinent to understand the degree of fidelity adherence in JPM delivery to ensure confidence in interpretation of reported outcomes and replication of this once JP is expanded. This study aimed to understand fidelity of JPM delivery within a therapeutic setting for men experiencing suicidal crisis. The perceived context-specific facilitators and barriers of the JPM were explored to provide insights into adherence of JPM delivery in practice and its perceived acceptability.

Materials and methods

Design

A mixed methods design was used. This allowed integration of objective and subjective data, an approach needed within suicide-related research (Kral et al., Citation2012). Specifically, it facilitated assessment of a range of quantitative data routinely collected by JP pertaining to delivery of the JPM as planned (e.g. number of sessions men attended, frequency of delivery of LYCT) and exploration of therapists perceptions of factors associated with the men’s acceptability of, and fidelity to planned delivery of the JPM. Two facets of fidelity to the intended delivery of the JPM were assessed; (1) adherence to content of the JPM during delivery (fidelity of content); and (2) number of sessions delivered (fidelity of duration). Semi-structured interviews assessed therapists’ perceived acceptability and views of fidelity to delivery of the JPM. Ethical approval was given by Liverpool John Moores University Research Ethics Committee (reference: 21/PSY/007). Written consent was gained from men using the service during their initial welcome assessment for the purpose of reviewing their records for research and/or service evaluation purposes. Welcome assessments are conducted by JP therapists who are aware of ethical issues and considerations. Written consent was also gained from JP therapists whose clinical records were audited and who participated in semi-structured interviews.

Participants

Thirty of 101 cases of men who had received and completed the JP intervention during the period from 1st December 2020 to 30th November 2021 were randomly selected for auditing. To remove bias, an administrator who was not involved in delivery of therapy, randomly selected five completed cases for each therapist for auditing. The qualitative element of this study involved semi-structured interviews with eight therapists (5 female) trained to deliver the JPM from JP Liverpool (n = 4) and JP London (n = 4) and were conducted between 5th November 2021 and 18th March 2022.

Quantitative phase: procedure and analysis

Document analyses of internal records auditing 30 cases, representing five cases per therapist at JP Liverpool, were assessed to evaluate fidelity of adherence to the planned delivery of the JPM. The audit was conducted over two consecutive days in December 2021 by three JP staff (centre manager, clinical lead, and member of administrative staff) and a researcher. On day one, the administrator and clinical lead completed a primary audit on the 30 randomly selected cases. Simultaneously, the researcher completed a secondary audit on 15 of those cases. Once each interview session was completed, both raters reviewed their individual score sheets separately. Each item was then jointly reviewed to identify and record disagreements and a consensus reached on the final score.

Each auditor recorded JPM components delivered against JPM content specification, for example duration (i.e. number of sessions attended) and content (e.g. completion of a safety plan and sets LYCT used), using an audit tool. The audit tool was co-produced between the clinical lead and administration staff and was developed using theoretical and clinical insights from current research and clinical practice. Points were given if therapists had delivered key components of the JPM including each of the four sets of LYCT and if a safety plan was uploaded onto the clinical information system. See for the scoring scheme. Additional delivery features were assessed including the number of sessions delivered and how long men accessed the service for. Adherence was calculated by adding the points awarded and scored out of a maximum score of 10. JP deemed a score of less than 5 (range 0–4) as an unacceptable level of adherence and a score of 5 and above as acceptable (range 5–10). Inter-rater reliability was compared against primary and secondary audits of individual cases. Disagreements between the primary and secondary audit were resolved through examination and discussion of individual case records between three auditors. Descriptive analyses of audit materials were conducted independently by the research team.

Table 1. Audit scoring scheme.

Qualitative phase: procedure and analysis

Semi-structured interviews with therapists explored their views on fidelity of delivery of the JPM, including barriers and facilitators that may influence their delivery of the model. Perceived acceptability of the JPM was explored to understand service-user-related factors that may affect fidelity. Interviews were conducted either face-to-face (n = 4) or online (n = 4) and were audio-recorded using a Dictaphone, ranging from 42 to 66 minutes. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019). Trustworthiness of qualitative data was achieved as each interview was read in a process of data familiarisation, and initial codes and themes were developed through an iterative process of theme development by the primary and last authors (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Three additional researchers reviewed the themes developed with the primary researcher when refining, revisiting, and finalising the themes; thus ensuring rigour and transparency (Yardley, Citation2000).

Results

Quantitative findings

Audit results are presented in and confirmed adherence scores for completed cases ranged from 2 to 9 (M = 5.67, SD = 2.01) indicating a medium level of adherence to planned delivery of the JPM. Fidelity delivery of the four sets of LYCT, scored out of 0–5, varied from no cards being delivered to all four sets of LYCT being delivered (M = 2.67, SD = 1.94; range 0–5). Number of sessions ranged from 2 to 16 sessions (M = 8.17, SD = 2.79; range 2–16) and safety plans were recorded in 21 of 30 cases (70%). A reduction in CORE-OM score upon discharge from the service was recorded in every audited case, except for one case where a reduction in suicidality was reported within the clinical case notes. Secondary audit scores achieved moderate inter-rater reliability (agreement in 9 of 15 cases; 60%). Disagreement between the primary and secondary audit was largely due to the researcher’s unfamiliarity with the clinical information system and difficulty locating the required information. All disagreements were resolved by reviewing clinical case notes and discussion between the auditors.

Table 2. JP audit results (n = 30).

Qualitative findings

Five themes were identified (Therapeutic environment; Specialised suicide prevention training; Therapy engagement; Person-centred care and Adapting the JPM to individual needs) and are summarised below with illustrative quotes.

Theme 1: therapeutic environment: the third therapist (N = 6)

The therapeutic environment at JP is purposely non-clinical and its importance was noted by therapists.

An environment that speaks to masculinity (n = 4)

The physical environment at JP was perceived by therapists to speak to men’s masculinity in a way that contrasts with traditional mental health services by engendering a person-focused, safe, and non-judgemental ‘space’ for men to feel confident to disclose their suicidality;

I must say, again, in my 20-odd years of doing therapy, it’s such a unique environment. It’s an environment I would not normally associate with therapeutic intervention … It’s normally a cupboard underneath a staircase with no windows. So, actually being in an environment which is open, which feels like a living room, actually. And the men notice that when they come in. (Therapist 6)

The environment, and everything else like that, it’s not like going somewhere where somebody is going to label you. (Therapist 2)

Developing therapeutic alliance (n = 3)

Therapists contribute to the therapeutic environment by cultivating therapeutic alliance with the men. This may involve reflecting the man’s composure, or upon their own experiences to gain trust and develop rapport;

‘I think personal experience is great. Because I have children myself, that is always useful. So, when men talk about their children, that’s relatable … I have been divorced, so relationship breakdown, that is something that … I think it’s about personal experience. What is it that can come up, that can emerge, that can connect you and this man in a way that they have never been engaged with before?’ Therapist 6

Theme 2: specialised suicide prevention training (N = 7)

While JP therapists are qualified, each received additional specialised suicide prevention training from the JP clinical lead.

Formal training (n = 7)

Training examined key areas including suicide risk factors, theoretical underpinnings of the JPM and the LYCT component. Therapists perceived training provided a framework for delivering the JPM. However, it is real-world experience of delivering the JPM that increases their confidence to foster flexibility when co-producing therapy with the men;

Yes, I did find it useful because before I'd never worked in that way with cards. I just did literally talking therapy, person-centred talking therapy. This was new and different, but very useful. Yes, I think it gave me enough knowledge or prepared me enough to then be able to put it in practice. (Therapist 1)

Informal colleague support (n = 3)

Therapists described benefiting from receiving additional support given from more experienced therapists during informal, incidental conversations and weekly case management meetings. This was received from colleagues separate to their clinical supervision and was viewed to offer new therapists’ assurance they were delivering the JPM correctly and allowed them to envisage how they might co-produce therapy with men;

I think at first when I first started, I was very rigid with the training that I was given and the cards had to be done every single session and if I didn’t use the cards in the session I was doing it wrong. Whereas now I think it’s more organic, you bring the training that you received at the beginning as well as the cards, but it doesn’t have to be in every session. One size doesn’t fit all does it with our clients? (Therapist 3)

Developing training (n = 6)

Formal review of therapist progression shortly after assignment of their own caseload was identified by therapists as a potential improvement to training. Additionally, inclusion of case studies could enhance knowledge as to how to integrate additional therapeutic strategies within JPM delivery;

I think doing some case studies would be really helpful. It would have been, probably, really helpful to see maybe one of the more senior therapists actually talk through, ‘This is how I would tend to use the cards,’ or, ‘These are the things that change between clients. (Therapist 4)

Maybe like a check-in later, so you could have the initial training and then you could have a three-month check-in, so like, ‘How's it going?’ and a refresher, ‘How have you actually found it in practice? (Therapist 8)

Supervision: caring for the carers (n = 8)

Therapists received supervision both internally within JP and from an external provider as part of their professional registration. Both were perceived as essential for maintaining well-being. Internal supervision allowed therapists to reflect upon their clinical practice, and to seek support for more challenging cases;

Yes, it’s good to be able to offload for yourself. It’s good when you feel stuck with somebody, like, ‘How do you do this? (Therapist 2)

Well, I actually think it’s really useful that it is external in some ways, because some of the things that might stress me out here might be things that I don’t particularly feel comfortable talking about here. So, it’s, kind of, nice to have both of those types of supervision. (Therapist 4)

Theme 3: therapy engagement (N = 8)

Face-to-face delivery, availability of rapid access to, and the brief duration of, the JPM were identified as key facilitators in promoting the acceptability of the JPM among men accessing the service. However, therapists encounter some challenges adhering to the specified number of sessions within the JPM;

Accessibility and acceptability of therapy (n = 8)

Seeing men during their crisis was perceived as validating of their experience, and facilitated a safe, therapeutic space to discuss suicide whilst developing effective therapeutic strategies;

So, for me, it is that swiftness of getting people in, and then that just being able to talk. It is just a space to say, ‘What’s happening for you?’ and, ‘How are you coping with that? What can we do to keep you safe?’ So, somebody is really saying to you, ‘Yes, what you’re feeling is worrying.’ Somebody is validating, and then giving you the support of, ‘But we can keep you safe,’ well, ‘We can help you to keep you safe. (Therapist 2)

Usually the guys, they've done well and everything is done, the next session is to finalise things. They decide to not attend the last session. (Therapist 1)

But also, if something else comes up within their lives, where they feel, ‘I can’t make that session,’ or, ‘I think I’ve had enough of this now,’ I think it’s okay to make that decision. And I think it’s up to us to support that decision, because that’s all part and parcel of the empowerment of those men. (Therapist 6)

Keeping therapy brief (n = 5)

The number of planned sessions within the JPM was perceived as acceptable and suitable. Adhering to this could be challenging and required therapists to manage their own expectations of what can be achieved within a brief intervention and to recognise a man’s recovery may continue once they have completed the JPM;

It's just about touching on things which can be recognised as a really important issue for somebody, without having to go into too much detail. Not getting sucked into it within the short time we have. I think it's quite useful to know it, and to notice it, and to recognise it, without having that. That's powerful. (Therapist 7)

Theme 4: person-centred care (N = 8)

Therapists had comprehensive understanding of the JPM and its constituent elements, including the LYCT.

Normalising sharing of suicidal experiences (n = 8)

LYCT were perceived by therapists to allow men to visualise and voice their suicidal distress, when previously they have felt unable to share their suicidal experiences. Self-compassion emerged as the men recognised the burden of having such a lot to contend with; thus destigmatising suicidal distress;

… it’s when there’s that, kind of, real fear around what they’re experiencing that I find it’s so important to normalise it and it’s so important to say, ‘Actually, you’re not the only person to feel this way. These are some of the reasons why you may be feeling this way and you do have some element of control and some options available to you. (Therapist 4)

I suppose what the cards do is they short-circuit all the longwinded discussions that may go on, but it brings it straight to the specific. And we also have to bear in mind that we’re a time-limited service, so the earlier we can get to what the specific issues are, then it provides more time for us to really sieve that through and work that through. (Therapist 6)

Co-production in action (n = 8)

Co-production featured in different elements of the JPM including the inclusion of therapeutic strategies and safety planning. This allows therapists to work collaboratively by standing together, shoulder-to-shoulder with men to co-produce and adapt the JPM to find solutions to their crisis. Therapists reported that they delivered the JPM in a manageable way that did not set expectations beyond the man’s reach such as omitting the LYCT component if the man is too distressed to engage with them;

So, it’s really just about making sure that it’s an open conversation right from the start and that they feel that they can, you know, slow things down or change direction if they need to, so, yes. (Therapist 4)

‘Sometimes I think they’re [lay your cards on the table] not needed and sometimes I think a client just needs to have a counselling session … ’ Therapist 3

I think in terms of co-production, I really feel that I can’t work the same with every person. So, I think the treatment, or so to speak, maybe even treatment’s a bit of a clinical word, but the intervention process is so tailored to each man. Like, uniquely. It’s not cookie-cutter, it’s not one size- (Therapist 5)

Theme 5: adapting the JPM to individual needs (N = 8)

Tolerance of flexibility in the delivery of JPM components was reported, particularly with the LYCT component, to address the needs of each individual man.

Flexibility in implementation of lay your cards on the table (n = 8)

Men were reported to interact with the LYCT in different ways, such as grouping relevant themes together or taking photographs of them to reflect upon their progress. Similarly, therapists described different ways of delivering the LYCT to suit each man’s presentation, preserve their safety and to respond to changing needs during therapy. For example, integrating the language of the cards into their discussions rather than physically administering them, and omitting/alternating the order in which they are delivered;

Sometimes when someone doesn't have any coping strategies, or think they don't have any coping strategies, then sometimes I would do the, ‘How can I get through this first?’ if they're very much in a distressed state. (Therapist 1)

They’ve either been covered in the person saying the story, or just in the session. So, you know, I’ve done a few sessions where we’ve not used them at all, but we’ve done it- If you know what I mean. So, they’ve not physically gone through the cards, but that’s what we’ve been talking about. (Therapist 2)

I think it’s very useful to be flexible. Flexible, robust and adaptable, I think is the right answer to that. Because you never know what men will bring, from one week to the next … that man may be going back into a turbulent situation after leaving the session. (Therapist 6)

Necessity of safety planning (n = 5)

Safety planning was viewed as an uncompromising JPM component by therapists as it documented actions men could initiate to keep themselves safe. Co-production of this occurred at different stages of the therapeutic journey;

I mean, I think that’s quite helpful. We’ve even had some men who, once you’d done that, they were like, ‘Oh, I’m okay,’ do you know what I mean? So, the safety plan, in itself, is a really positive thing. (Therapist 2)

I always do a safety plan with men. That might be at the beginning if I think someone is a really high-risk. They also can be towards the end … (Therapist 5)

Flexibility promotes use of additional therapeutic tools (n = 8)

Therapist autonomy is respected within the JPM allowing them to introduce additional therapeutic techniques when tailoring its delivery. A range of additional techniques were reported to support men in developing resilience and coping skills including CBT-based approaches, self-compassion and psychoeducation;

I think there’s a little bit of psychoeducation that I offer alongside what we’re doing here, so things like understanding anxiety, how anxiety actually works in the body and, therefore, what we can do to try and manage it. I think that’s something that I offer that doesn’t necessarily come from the cards that seems to be really helpful … (Therapist 4)

Discussion

Summary of findings

This is the first study to evaluate fidelity of delivery of the JPM and was comprised of two phases: an audit of clinical cases of men accessing JP and semi-structured interviews with therapists trained to deliver the JPM exploring their perspectives of adherence and acceptability of the JPM. Descriptive analyses of JP audit notes revealed moderate levels of adherence to specification of intended delivery of the JPM amongst therapists. Audit notes and semi-structured interview findings highlighted components of JPM that required tailoring according to individual men’s needs including LYCT and safety planning.

Several facilitators of acceptability of the JPM among men experiencing suicidal crisis and adherence to the specification of model delivery were encompassed within five themes. The first theme, therapeutic environment: the third therapist highlighted importance of the therapeutic setting for engaging suicidal men. The second theme identified specialised suicide prevention training in the JPM that facilitated therapists understanding and expertise. The third theme, therapy engagement which improved engagement in therapy among men. The fourth theme identified was person-centred care related to co-production and timeliness of the introduction of the LYCT or safety planning tools. The final theme adapting the JPM to individual needs within the parameters of the JPM structure, was identified as necessary for facilitating the adaptation of the JPM to suit men’s needs.

Clinical implications

Collectively, the factors identified were perceived by therapists to allow men to feel heard, visible, and held in a safe space while discussing their suicidal crisis. Men have historically been considered a challenging population to engage in traditional mental health support services due to poor help-seeking behaviours (Cleary, Citation2012, Citation2017) associated with masculine ideals such as stoicism, self-reliance, and shame (Pirkis et al., Citation2017; Rasmussen et al., Citation2018; Seidler et al., Citation2021). Emerging evidence challenges the narrative around masculinity and suicidal men’s help-seeking behaviours (Chandler, Citation2021). For example, Richardson, Dickson et al. (Citation2021) explored suicide from attempt to recovery among men, finding most men had recognised their need for mental health support. However, they did not know where to go or how to ask for support. This suggests that existing mental health services do not have sufficient acceptability and/or reach among men experiencing suicidal crisis. Findings elsewhere echo this point, reporting the need for informal, community-based mental health service provision for men which offers tailored, collaborative person-centred care to enhance accessibility and engagement (Player et al., Citation2015; Seidler et al., Citation2018; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019).

JP is embedded within the local community and offers rapid access to person-focused brief psychological support. JP has enabled an establishment of close working partnerships and referral pathways with local community support services. This allows JP therapists to refer men to local services for additional psychosocial issues such as debt management, housing and alcohol and drug services. JPM principles (e.g. rapid access, referral pathways, environment) align with key priorities highlighted within health care initiatives across the UK such as the ‘Time, Space, Compassion’ strategy in Scotland (National Suicide prevention Leadership Group, Citation2021) and the National Suicide Prevention Strategy (Department of Health and Social Care, Citation2023). The former outlines a framework advocating integration of timely access to therapeutic space offering compassionate care which is sensitive and empathetic towards the needs of the individual experiencing suicidal crisis (National Suicide prevention Leadership Group, Citation2021). While the National Suicide Prevention Strategy emphasises the role of front-line services such as those that are third sector and community-based, in providing tailored suicide crisis intervention to high-risk priority groups, including middle-aged men (Department of Health and Social Care, Citation2023).

Brevity of duration of the JPM was perceived as a striking intervention feature by the therapists. Research supports the efficacy of brief psychological interventions for suicidal crisis where they deliver early intervention; the provision of targeted information about suicide (e.g. understanding and management of suicide) and safety planning is given, and sustained follow-up occurs (McCabe et al., Citation2018). Studies have shown that the JPM as a brief psychological intervention reduces suicide among men (Chopra et al., Citation2022; Saini et al., Citation2020, Citation2022; Saini, Chopra, Hanlon, & Boland Citation2021; Saini, Chopra, Hanlon, Boland, & O’Donoghue Citation2021). Although, therapists in the present study highlighted the acceptance that some men may go on to receive further support from additional services also (e.g. for housing/unemployment issues or traumatic childhood experiences).

There is a structure and expectation that therapists will deliver each core component of the JPM including the LYCT, safety planning and the CORE evaluation questionnaires. Audit results revealed delivery of the LYCT varied across cases. Therapists reflected during interviews that LYCT delivery was not always appropriate for every man, and perceived that flexibility and co-production facilitated within the parameters of the JPM was a pre-requisite for shifting away from universal approaches to suicide prevention. This finding adds to calls for tailored suicide prevention interventions for men experiencing suicidal crisis (Player et al., Citation2015; Seidler et al., Citation2018; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019).

Therapists described utlising their clinical judgment to adapt delivery of the JPM content to address the complexities of each individual man’s crisis (e.g. omitting LYCT and/or delivery of additional therapeutic strategies). This practice was also evident from audit documents. Balancing fidelity of delivery with the adaptation of the JPM for individual men without diminishing mechanisms of change poses a significant challenge to therapists delivering the model and researchers evaluating its effectiveness. Regular auditing of JPM delivery adherence during case management meetings could offer a feasible way to evaluate fidelity without compromising determination of the JPM’s effectiveness.

Safety planning was perceived by therapists as an essential component of the JPM. However, audit findings revealed that 70% of cases had safety plans documented onto the clinical information system. Several reasons may account for safety plans not being documented. For example, some men prefer a digital safety plan accessible via their mobile phone app’s (e.g. the Stay Alive app). The clinical information system in use at the time of the audit did not have a facility for therapists to upload copies of safety plans developed this way. Therefore, a safety plan may have completed but not uploaded onto the clinical information system.

Audit results have been used to guide development of a newly introduced clinical information system and to further improve clinical practice and training. For example, audit results indicated inconsistent use of the LYCT component of the JPM. An audit score of 5 out of 10 is considered acceptable, however if no sets of cards of the LYCT component is used, then intervention delivery is considered non-adherent. Measures have now been put in place such that a case review is triggered if the ‘What’s happening now’ cards have not been introduced by session three.

Strengths and limitations

This study challenges the perception that men do not seek help for suicidal crisis, adding to literature highlighting the need for informal, community-based mental health service provision for men experiencing suicidal crisis. However, generalisability of the audit findings is limited as they only reflect the data of men accessing JP and it is not possible to establish how delivery of the JPM may be required to change to engage men not accessing the service to be effective in reducing suicidal distress. As with any suicide prevention intervention study, suicidal distress may reduce without psychological intervention (Chopra et al., Citation2022). Therefore, it is feasible reduction in suicidal distress observed within the sample was not attributable to the JPM (Chopra et al., Citation2022). However, research evidence suggests the JPM significantly reduces suicidal distress among men (Chopra et al., Citation2022; Saini et al., Citation2020, Citation2022; Saini, Chopra, Hanlon, & Boland Citation2021; Saini, Chopra, Hanlon, Boland, & O’Donoghue Citation2021).

The study also provided valuable insights into fidelity of delivery and identification of the facilitators and barriers that may influence acceptability and implementation of the JPM but neglects the views of men who engaged with JP. Involving JP staff provided invaluable expertise when navigating the clinical recording system and extracting data during the audit process. Additionally, the audit tool which assessed adherence of delivery fidelity while clinically informed, was developed internally by JP. This could have introduced bias into the audit procedure such as observer bias whereby JP staff unconsciously recorded fidelity of intervention components more favourably (e.g. presence of a safety plan when it was not recorded on the system). Steps were taken to ensure random selection of completed cases for therapists, and first and second coder independence in assessing adherence of therapist delivery of the JPM. However, a range of fidelity assessment methods are recommended (Bellg et al., Citation2004).

Future research

Future research should seek to explore the views of men accessing JP to gain further understanding of factors that may influence implementation of the JPM. Also, the types and frequency of additional therapeutic approaches used by therapists should be assessed and linked to behaviour change techniques to further understanding of JPM components attributable to suicidality reduction. Lastly, additional methods to assess fidelity of the JPM should be deployed in future evaluations. Gold standard approaches include using observation methods (e.g. video- or audio-recorded sessions) and/or self-report methods (Bellg et al., Citation2004). However, it is important to note this study evaluated delivery fidelity and does not provide an assessment of the quality of delivery such as therapeutic competence.

Conclusion

Findings support the need for clinical pathways and mental health service provision that holistically considers the complexities of suicide among men, such as that offered by JP. Seeking to standardise every aspect of the JPM is not feasible given the individual nature of suicidal crisis. Rather, moderate delivery fidelity to core components of the JPM is achievable when tailoring the model to address men’s individual needs.

Ethical statement

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by an Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee. See details under Methods.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend special thanks to the staff of James’ Place for their contributions to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bellg, A. J., Borrelli, B., Resnick, B., Hecht, J., Minicucci, D. S., Ory, M., Ogedegbe, G., Orwig, D., Ernst, D., Czajkowski, S., & Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 23(5), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443

- Bennett, S., Robb, K. A., Zortea, T. C., Dickson, A., Richardson, C., & O'Connor, R. C. (2023). Male suicide risk and recovery factors: A systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis of two decades of research. Psychological Bulletin, 149(7-8), 371–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul00003

- Borrelli, B. (2011). The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71(s1), S52–S63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00233.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Canetto, S. S., & Sakinofsky, I. (1998). The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 28(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1998.tb00622.x

- Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2, Article 40 https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-40

- Chandler, A. (2021). Masculinites and suicide: Unsettling ‘talk’ as a response to suicide in men. Critical Public Health, 32(4), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2021.1908959

- Chopra, J., Hanlon, C. A., Boland, J., Harrison, R., Timpson, H., & Saini, P. (2022). A case series study of an innovative community-based brief psychological model for men in suicidal crisis. Journal of Mental Health, 31(3), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1979489

- Cleary, A. (2012). Suicidal action, emotional expression, and the performance of masculinities. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 74(4), 498–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.002

- Cleary, A. (2017). Help-seeking patterns and attitudes to treatment amongst men who attempted suicide. Journal of Mental Health, 26(3), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2016.1149800

- Department of Health and Social Care. (2023). Policy paper: Suicide prevention in England: 5-year cross-sector strategy. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/suicide-prevention-strategy-for-england-2023-to-2028/suicide-prevention-in-england-5-year-cross-sector-strategy#executive-summary

- Eggenberger, L., Ehlert, U., & Walther, A. (2023). New directions in male-tailored psychotherapy for depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, Article 1146078. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1146078

- Gearing, R. E., El-Bassel, N., Ghesquiere, A., Baldwin, S., Gillies, J., & Ngeow, E. (2011). Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.007

- Hanlon, C. A., Chopra, J., Boland, J., McIlroy, D., Poole, H., & Saini, P. (2022). James’ Place model: Application of a novel clinical, community-based intervention for the prevention of suicide among men. Journal of Public Mental Health, 21(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-09-2021-0123

- Jobes, D. A. (2012). The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality (CAMS): An evolving evidence-based clinical approach to suicidal risk. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(6), 640–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00119.x

- Joiner, Jr., T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association.

- Kral, M. J., Links, P. S., & Bergmans, Y. (2012). Suicide studies and the need for mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(3), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689811423914

- Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909–916. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909

- McCabe, R., Garside, R., Backhouse, A., & Xanthopoulou, P. (2018). Effectiveness of brief psychological interventions for suicidal presentations: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), Article 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1663-5

- Naghavi, M. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality, 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ, 364, Article 194. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l94

- National Suicide Prevention Leadership Group. (2021). Time, space, compassion three simple worlds, one big difference: Recommendations for improvements in suicidal crisis response. Cabinet Secretary for NHS Recovery and Social Care, Scottish Government. https://www.gov.scot/publications/time-space-compassion-three-simple-words-one-big-difference-recommendations-improvements-suicidal-crisis-response/documents/

- O'Connor, R. C. (2011). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 32(6), 295–298. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000120

- O'Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences, 373(1754), Article 20170268. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

- Office of National Statistics (ONS). (2021). Suicides in England and Wales: 2020 registrations. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2020registrations

- O'Gorman, K. M., Wilson, M. J., Seidler, Z. E., English, D., Zajac, I. T., Fisher, K. S., & Rice, S. M. (2022). Male-type depression mediates the relationship between avoidant coping and suicidal ideation in Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), Article 10874. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710874

- Oliffe, J. L., Rossnagel, E., Bottorff, J. L., Chambers, S. K., Caperchione, C., & Rice, S. M. (2020). Community-based men's health promotion programs: Eight lessons learnt and their caveats. Health Promotion International, 35(5), 1230–1240. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daz101

- Pirkis, J., Spittal, M. J., Keogh, L., Mousaferiadis, T., & Currier, D. (2017). Masculinity and suicidal thinking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1324-2

- Player, M. J., Proudfoot, J., Fogarty, A., Whittle, E., Spurrier, M., Shand, F., Christensen, H., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Wilhelm, K. (2015). What interrupts suicide attempts in Men: A qualitative study. PloS one, 10(6), Article e0128180. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128180

- Rasmussen, M. L., Hjelmeland, H., & Dieserud, G. (2018). Barriers toward help-seeking among young men prior to suicide. DHealth and Social Careeath Studies, 42(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2017.1328468

- Richardson, C., Dickson, A., Robb, K. A., & O'Connor, R. C. (2021). The male experience of suicide attempts and recovery: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), Article 5209. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105209

- River, J., & Flood, M. (2021). Masculinities, emotions and men’s suicide. Sociology of Health & Illness, 43(4), 910–927. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13257

- Saini, P., Chopra, J., Hanlon, C., & Boland, J. (2022). The adaptation of a community-based suicide prevention intervention during the COVID19 pandemic: A mixed method study. Cogent Psychology, 9(1), Article 2066824. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2022.2066824

- Saini, P., Chopra, J., Hanlon, C., Boland, J., Harrison, R., & Timpson, H. (2020, October). James’ Place internal evaluation: One year report. Liverpool John Moores University. https://www.jamesplace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/James-Place-One-Year-Evaluation-Report-Final-20.10.2020.pdf

- Saini, P., Chopra, J., Hanlon, C. A., & Boland, J. (2021). A case study series of help-seeking among younger and older men in suicidal crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(14), Article 7319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147319

- Saini, P., Chopra, J., Hanlon, C. A., Boland, J., & O’Donoghue, E. (2021, August). James’ Place internal evaluation: Two year report. Liverpool John Moores University. https://www.jamesplace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Year-two-Report-Final-September-2021.pdf

- Saini, P., Whelan, G., & Briggs, S. (2019, March). Qualitative evaluation six months report: James’ Place internal evaluation. Liverpool John Moores University.

- Seidler, Z. E., Dawes, A. J., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., & Dhillon, H. M. (2016). The role of masculinity in men's help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 49, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.002

- Seidler, Z. E., Rice, S. M., River, J., Oliffe, J. L., & Dhillon, H. M. (2018). Men’s mental health services: The case for a masculinities model. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 26(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060826517729406

- Seidler, Z. E., Wilson, M. J., Oliffe, J. L., Kealy, D., Toogood, N., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., & Rice, S. M. (2021). “Eventually, I admitted, ‘I can’t do this alone’”1; exploring experiences of suicidality and help-seeking drivers among Australian men. Frontiers in Sociology, 6, Article 727069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.727069

- Stiawa, M., Müller-Stierlin, A., Staiger, T., Kilian, R., Becker, T., Gündel, H., Beschoner, P., Grinschgl, A., Frasch, K., Schmauß, M., Panzirsch, M., Mayer, L., Sittenberger, E., & Krumm, S. (2020). Mental health professionals view about the impact of male gender for the treatment of men with depression - a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), Article 276. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02686-x

- Struszczyk, S., Galdas, P. M., & Tiffin, P. A. (2019). Men and suicide prevention: A scoping review. Journal of Mental Health, 28(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370638

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). (2021). Suicide: Fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- Trail, K., Oliffe, J. L., Patel, D., Robinson, J., King, K., Armstrong, G., … Rice, S. (2021). Promoting healthier masculities as a suicide prevention intervention in a regional Australian community: A qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives. Frontiers in Sociology,6, 728170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.728170

- Yardley, L. (2000). Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology & Health, 15(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008400302