ABSTRACT

Background:

Research on the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on well-being among children with disabilities is scarce. Studies in children and adolescents that have problems with hearing or listening, a possibly particularly vulnerable group during the pandemic, are largely lacking.

Aims:

We investigated well-being, stress experiences, and self-efficacy among children who are deaf or hard of hearing (D/HH) or with auditory processing disorder (APD) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

A total of N = 90 children who are D/HH or with APD (47% girls, Mage = 14.95, SD = 2.02) from a special needs school completed self-reports. Data were assessed in Germany in May 2021.

Results:

Over half the children (52%) reported low well-being. Well-being correlated negatively with stress (perceived stress and stressor occurrence, both for the three different domains: general everyday stressors, pandemic-specific stressors, hearing-specific stressors, r = −.27 to −.56) and positively with self-efficacy (r = .42). Regression analyses confirmed the positive association between well-being and self-efficacy (β = .37/.30). Regarding stress, perceived stress for pandemic-specific stressors (e.g. homeschooling, crowds, β = -.35) and a stronger occurrence of everyday stressors (e.g. gossiping, parents having no time, β = -.45) were relevant for lower well-being.

Conclusions:

Especially everyday and pandemic-related stressors should be taken seriously. Self-efficacy should be strenghtened as a resource.

Since spring 2020 the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has dominated our lives. To prevent the spread of COVID-19 for health protection, measures were taken that strongly influence everyday life (Cheng et al., Citation2020). These include physical distancing from others, contact restrictions, keeping hygiene rules, wearing facemasks, and in the context of a COVID-19 infection isolation and quarantine (WHO, Citation2021). In children and adolescents, the COVID-19 infection usually caused only mild symptoms (for a review, Castagnoli et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, for youth, COVID-19 measures and lockdowns led to significant changes in their everyday lives including repeatedly prolonged closure of schools and accompanying homeschooling, restricted leisure acitivities, limited meeting of peers, and instructions to stay at home. Meanwhile, many studies point to the impact of the pandemic and its restrictions on worsened well-being and poorer mental health among children and adolescents (for reviews, Nearchou et al., Citation2020; Racine et al., Citation2021; Viner et al., Citation2022). For example, results of the COPSY study, a German population-based survey, showed a significant pandemic-related decrease in well-being: low well-being was reported from 15% of children and adolescents pre-pandemic, whereas during pandemic the proportion with low well-being was 40% (spring 2020), 48% (winter 2020/2021), and 35% (autumn 2021; Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022b).

Children with hearing/listening impairment as a possible vulnerable group

The pandemic and its restrictions did not affect all children and adolescents equally, impairment of well-being and mental health were particularly evident for vulnerable groups (Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022a). Research on the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for mental health and well-being among children with disabilities is scarce (Geweniger et al., Citation2022; Mann et al., Citation2021; Patel, Citation2020). Especially studies in children and adolescents with problems of hearing or listening are largely lacking. Ariapooran and Khezeli (Citation2021) reported anxiety symptoms during the pandemic for one-third of the adolescents with hearing loss in Iran. In the UK, about 60% of deaf adolescents reported pandemic-related declines in mental health and well-being (Wright et al., Citation2021).

According to Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), the individual’s well-being and mental health will be endangered as a result of stressful situations that are perceived negatively as taxing or exceeding resources. Obviously, the pandemic can be conceptualized as an ongoing stressful condition with numerous changes in daily life, possible harm, loss and threats, and (at least in the beginning) little experience to deal with them. Children and adolescents are considered a vulnerable group (Geweniger et al., Citation2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022a). However, it is mostly unclear whether children with problems of hearing or listening experience additional stress in the context of the pandemic and whether they show well-being comparable or worse to those with typical levels of hearing. For example, following health recommendations, such as wearing a facemask, were clearly advocated (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], Citation2022). Nevertheless, wearing facemasks (i.e. impossible to lip-read, reduced visible facial expression, possibly less clear pronunciation, reduced volume; Garg et al., Citation2021) and avoiding touching the face when signing made communication more demanding for children with hearing/listening impairment and, therefore, could increase the risk for misunderstandings and frustration.

With regard to stressful situations faced by children and adolescents with hearing/listening impairment, initial pre-pandemic research showed a clear similarity in terms of common everyday stressors to peers with typical levels of hearing. In addition, there were hearing-specific stressors. For example, Eschenbeck et al. (Citation2017) found similar perceived stress levels between children who are deaf or hard of hearing (D/HH) or children with auditory processing disorder (APD; i.e. with difficulties in recognizing and interpreting sounds composing speech) to those with typical hearing. Thereby, children who are D/HH and children with APD perceived common everyday stressors within family, school, and peers as more stressful than more hearing-specific situations (i.e. speech comprehension problems). Similarly, Zaidman-Zait and Dotan (Citation2017) showed that D/HH adolescents’ stressful experiences were similar to youth without hearing impairment.

Associations of stress experience and self-efficacy with well-being

Assuming that stressful situations are associated with the person’s well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), for example, Kiang and Buchanan (Citation2014) investigated this association in adolescents (with typical levels of hearing) using daily-diary data over 14 days. As expected, adolescents’ experience of daily stress (with family, school, and peers) was associated with lower well-being on the same day. Also, prolonged stress experience showed negative effects on well-being. To our knowledge, studies on daily stress experience and well-being are not available for children with hearing/listening impairment. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate stressors faced by children and adolescents with hearing/listening impairment and their association with well-being during the pandemic. Thereby, based on Eschenbeck et al. (Citation2017), the following stressor domains were distinguished: (a) more general normative daily situations with family, peers, or school, (b) more hearing-specific situations (communication problems), and in addition, (c) situations related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures to prevent transmission (wearing facemasks, lateral flow testing, contagion, crowds of people, homeschooling, staying home).

Regarding stress experiences, on one hand, Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) emphasized the individuals’ subjective appraisal of situations; accordingly what one person experiences as taxing or exceeding resources, another may perceive as less stressful or even irrelevant. On the other hand, there are more ‘objective’ approaches that address stressful events per se, that is whether a situation or condition occurred or not (Grant et al., Citation2003). Studies are heterogeneous and assess perceived stress by asking how stressful a situation was (Moksnes et al., Citation2019) or rather the occurrence/frequency of events (Burger & Samuel, Citation2017; Kiang & Buchanan, Citation2014). In the present study, we will consider both, the perceived stress and the occurrence of situations (in each case with regard to the three domains general daily situations, hearing-specific situations, and pandemic-related situations), and aim to investigate their contribution for well-being during the pandemic.

When experiencing stress, resources are crucial in dealing with the demands (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). Self-efficacy is considered as a major personal resource. It refers to the individual’s confidence in his/her ability to exercise control over stressors and successfully perform a particular task (Bandura, Citation1997). Hence, in studies with adolescents, stressor experience was negatively associated with well-being, whereas self-efficacy was related to better well-being (Andretta & McKay, Citation2020; Mikkelsen et al., Citation2020; Moksnes et al., Citation2019). Among children with hearing impairment, self-efficacy is an important personal resource in connection with the development of resiliency (Radovanović et al., Citation2020; see also King et al., Citation2020). However, a study that jointly investigated associations of self-efficacy and stress experience on well-being in children with hearing impairment is not available.

Current study

We investigated well-being, stress experiences, and self-efficacy among children who are D/HH or with APD during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study had the following objectives: First, to examine the self-reported well-being of children who are D/HH or with APD. Based on previous findings (Geweniger et al., Citation2022; Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022b), we expected that well-being during the pandemic has deteriorated; a high proportion of children who are D/HH or with APD report low well-being. Second, to investigate stressors faced by children who are D/HH or with APD. In extension to Eschenbeck et al. (Citation2017), we expected that especially pandemic-related stressors and general daily situations are more stressful compared to hearing-specific situations. Also between perceived stress and the occurrence of events, there are only moderate associations. Third, to explore the impact of stressful situations and self-efficacy on well-being. We expected that stressful situations (general daily situations, hearing-specific situations, and/or pandemic-related situations) as risk factors correlate negatively with well-being, whereas self-efficacy as resource is positively associated with well-being. Following Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), we expected that perceived stress (compared to the occurrence of situations) is more significant for well-being.

Gender, age, and the type of hearing/listening impairment (D/HH, APD) were considered as control factors. Numerous studies showed that in childhood and adolescence, gender and age were associated with well-being (Chen et al., Citation2020; Newland et al., Citation2019; Otto et al., Citation2017). D/HH and APD are different diagnoses regarding hearing/listening problems (ASHA, Citation2005; DGPP, Citation2013, Citation2015; see also Moore, Citation2018). However, children who are D/HH and children diagnosed with APD may face similar difficulties in oral communication situations.

Method

Participants

Overall, 105 children and adolescents from a specialist school for D/HH children in the south-western region of Germany participated in the study. The participation rate was 90%. Teachers gave information on the child’s hearing status. Fifteen students were not included in the study because they had no hearing/listening impairment. Thus, the final sample consisted of N = 90 children and adolescents (47% girls) with a mean age of 14.95 years (SD = 2.02, range 11–18; grade levels 5–12). Of these, 46 participants (39% girls; mean age: 14.85 years, SD = 2.03, range 11–18) were diagnosed D/HH and 44 participants had an APD (55% girls; mean age: 15.05 years, SD = 2.02, range 11–18). The two groups, children who are D/HH and children with APD, did not differ significantly with regard to age, t(88) = 0.46, p = .65, or gender, χ2 (1, N = 90) = 2.15, p = .14.

Procedure

Parents were informed about the study via an email from the class teacher. Information on the study was also provided to students. Students who would like to participate provided verbal consent before participation (required that their parents did not disagree). The data processed did not involve any identifying data. The study has received an ethical approval from the Ethics Commission of the University of Education Schwäbisch Gmünd (EK-2021-06-Eschenbeck-VK).

Data collection was conducted in May 2021. In Germany, by the end of April, a peak 7-day incidence had been reached in the third COVID-19 wave. Thereafter, the number of cases decreased (Robert-Koch-Institut, Citation2021). The schools were closed when the survey was conducted. Children completed the self-report online questionnaires during class time and homeschooling. The participating students took part in a video conference from their devices at home. A study staff member also joined the meeting to introduce and assist with the questionnaires.

Measures

Well-being

Well-being was assessed by the KIDSCREEN-10 (Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2010). It contains 10 items (‘Please think about last week. … Have you been full of energy?’) with a 5-point response scale from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘extremely’ (5) or ‘never’ (1) to ‘always’ (5), respectively. Responses are coded so that higher sum scores denote better well-being (sum scores between 10 and 50). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α/McDonald’s ω) was .84/.83 (for descriptive statistics, see ).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables.

Perceived stress

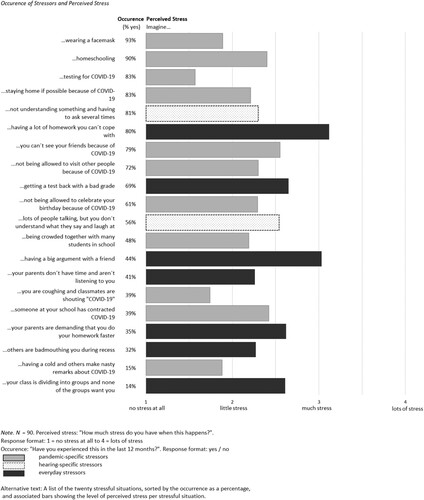

Perceived stress was assessed by the adapted and expanded stress scales of the revised German Stress and Coping Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (SSKJ 3-8; Lohaus et al., Citation2018). Children reported their level of perceived stress for different stressors (‘How stressful will the situation … be?’) on a 4-point scale from ‘not at all stressful’ (1) to ‘very stressful’ (4). The stressors consisted of (a) seven general everyday stressors (for items, see ), (b) eleven pandemic-specific stressors, and (c) two hearing-specific stressors concerning communication difficulties. For each stressor domain mean scale scores (sum of the item scores divided by the number of items) were computed (values between 1 and 4). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α/McDonald’s ω) for the three scales was α/ω = .72/.71 for general everyday stressors, α/ω = .82/.81 for pandemic-specific stressors, and α/ Spearman-Brown ρ = .76/.77 for hearing-specific stressors (for a two-item scale, see Eisinga et al., Citation2013).

Occurrence of stressful situations

For each stress situation described above (i.e. 7 general everyday stressors, 11 pandemic-specific stressors, and 2 hearing-specific stressors), children were asked whether they had experienced the situation within the last year (‘Have you experienced this in the last 12 months?’). The response format was ‘yes’ (1) or ‘no’ (0). For each stressor domain, mean scale scores were calculated (values between 0 and 1). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α/ Spearman-Brown ρ) for the three scales was α/ρ = .63/.64 for general stressors, α/ρ = .53/.40 for pandemic-specific stressors, and α/ρ = .40/.41 for hearing-specific stressors.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was measured by the Questionnaire to Assess Resources for Children and Adolescents (QARCA; Lohaus & Nussbeck, Citation2016). The subscale consists of six items (‘If I set myself a goal I will reach it’) with a 4-point Likert response scale that ranged from ‘never’ (1) to ‘always’ (4). A mean scale score was calculated (values between 1 and 4). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α/McDonald’s ω) was .78/.77.

Data analyses

Missing values were checked. Among the sample (90 cases), across all 56 items, there were a total of 47 values missing, representing 0.93% of all values. There was no evidence against the assumption that data are missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test, p = .41). With regard to our first research question, the KIDSCREEN-10 sum score was compared to gender- and age-stratified reference scores from the BELLA study (Barkmann et al., Citation2021), the mental health module within the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey for children and adolescents aged 11–18 years. Data collection of the BELLA study was between 2009 and 2012. Scores were splitted into low (T-value < 40), medium (T-value 40-59.9) or high (T-value ≥ 60) KIDSCREEN-10 values. To determine whether gender, age-group, and the type of hearing/listening impairment (D/HH, APD) showed an effect on well-being (KIDSCREEN-10 sum score), we performed an ANOVA with the three between-subject factors. Second, to analyse differences between stressor domains, separately for perceived stress and stressor occurrence, repeated-measures ANOVAs were conducted with stressful situation (three levels: general everyday, pandemic-specific, hearing-specific) as the within subject-factor. Post hoc comparisons following significant main effects for stressful situation were tested with Bonferroni-corrected p-value (p = .05/3). Partial Eta2 was calculated as an estimate of effect size; values of .01, .06, and .14 indicate small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, Citation1988). Correlations between the stressor domains were conducted. Third, to examine the impact of stressful situations and self-efficacy on well-being, we performed two regression analyses with well-being as dependent variable, stressful situations (either perceived stress or stressor occurrence; each with the three domains general everyday situations, hearing-specific situations, pandemic-related situations) and self-efficacy as predictors and gender, age-group, and type of hearing/listening impairment as control variables. Control variables were entered in the first step, all other predictors in the second step. G-Power 3.1 analyses (Faul et al., Citation2007) showed that a total sample size of n = 85 is needed for regression analyses (fixed model, R2 increase) for an effect size of f2 = .15 (with number of tested predictors: 4, total number of predictors: 7, α = .05, 1 − β = .80). There were significant associations between the variables (r < .65). A validation of the variance inflation factor (VIF < 2.07) indicated that there was no multicollinearity.

Ethics statement

Participation was voluntary, no financial compensation was provided, and informed consent was obtained. The Ethics Commission of the University of Education Schwäbisch Gmünd approved the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by an Institutional Review Board/Ethics committee. See details under Methods.

The study received an exemption from an Institutional Review Board/Ethics committee; See details under Methods.

Results

Children’s self-reported well-being during the pandemic (Research question 1)

Overall 51.7% of the children who are D/HH or with APD reported low well-being (KIDSCREEN-10: M = 30.24, SD = 4.63, n = 45), 42.5% reported medium scores (M = 40.38, SD = 3.49, n = 37), and 5.7% high well-being (M = 48.80, SD = 0.84, n = 5).

The ANOVA resulted in a significant main effect for gender, F(1, 87) = 4.41, p = .04, partial Eta2 = .053. No differences were found regarding age-group (p = .11) or the type of hearing impairment (p = .94). Interaction effects were also not significant (ps > .27). Girls reported lower well-being than boys (girls: M = 33.78, SD = 5.94, n = 40; boys: M = 37.19, SD = 7.75, n = 47). That is, a proportion of 57.5% of girls and 46.8% of boys reported low well-being.

Stressful situations: perceived stress and stressor occurence (Research question 2)

Perceived stress and the occurrence of situations correlated moderately for general everyday situations (r = .23) and hearing-specific situations (r = .30), and were uncorrelated for pandemic-related situations (r = −.03; see ).

With regard to perceived stress, there was a significant main effect for stressful situation, Wilks’s Lambda = .47, F(2, 86) = 47.82, p < .001, partial Eta2 = .53. On average, the perceived stress level was lowest for situations related to the COVID-19 pandemic (M = 2.13, SD = 0.60, Bonferroni adjusted ps < .001) and highest for everyday situations (M = 2.65, SD = 0.57). Perceived stress levels for hearing-specific situations were in between (M = 2.42, SD = 0.91, Bonferroni adjusted p ≤ .015). When repeating the ANOVA with gender, age-group, and the type of hearing/listening impairment (D/HH, APD) as additional between subject-factors, the described main effect for stressful situation remained unchanged, Wilks’s Lambda = .43, F(2, 79) = 51.42, p < .001, partial Eta2 = .57. For gender there was a significant main effect, F(1, 80) = 19.26, p < .001, partial Eta2 = .19, and an interaction effect with situation, Wilks’s Lambda = .82, F(2, 79) = 8.69, p < .001, partial Eta2 = .18. Girls generally perceived more stress than boys (girls: M = 2.64, SE = 0.08, boys: M = 2.14, SE = 0.08), especially for hearing-specific situations. Perceived stress was not modified by age-group or the type of impairment (all ps > .24). Correlations between the stressor domains were positive and ranged between r = .49 and .64 (see ). When inspecting the twenty stressful situations separately (see ), high stress levels were perceived for problems doing homework and argument with a friend, followed by receiving a bad grade, parents pressure about school work, nobody wants you to be part of the group, can’t meet friends because of COVID-19, and having difficulties understanding what others are saying.

Also for stressor occurrence, there was a significant main effect for stressful situation, Wilks’s Lambda = .57, F(2, 86) = 32.01, p < .001, partial Eta2 = .43. On average, stressor occurrence was least frequent for everyday situations (M = 0.45, SD = 0.25, Bonferroni adjusted p ≤ .001) compared to situations related to the COVID-19 pandemic (M = 0.64, SD = 0.17) and hearing/listening (M = 0.68, SD = 0.36). When adding gender, age-group, and the type of hearing/listening impairment as additional between subject-factors, the described main effect for stressful situation remained significant, Wilks’s Lambda = .53, F(2, 79) = 35.12, p < .001, partial Eta2 = .47. For age-group there was a significant main effect, F(1, 80) = 5.95, p < .05, partial Eta2 = .07, and an interaction effect with situation, Wilks’s Lambda = .90, F(2, 79) = 4.29, p < .02, partial Eta2 = .10. Older children reported more stressors (older: M = 0.64, SE = 0.03, younger: M = 0.54, SE = 0.03), except for everyday situation with no age-related difference. Independent of stressor domain, girls (M = 0.64, SE = 0.03) reported higher stressor occurrence than boys (M = 0.55, SE = 0.03), F(1, 80) = 4.66, p < .05, partial Eta2 = .06. Correlations between the stressor domains were positive and ranged between r = .25 and .40 (see ). When inspecting the individual twenty situations (see ), various pandemic-related situations were reported very frequently followed by the situations of having difficulties understanding what others are saying and problems doing homework.

Impact of stressful situations and self-efficacy on well-being (Research question 3)

Correlations are shown in . Well-being correlated negatively with perceived stress and stressor occurrence, and positively with self-efficacy.

Regression results are shown in and . The control variables (gender, age-group, type of hearing/listening impairment) explained 9% of the variance in well-being, F(3, 85) = 2.72, p = .05. Here only gender had an effect. When perceived stressful situations and self-efficacy were entered (Step 2), the variance increased to 38%, ΔR2 = .29, F(4, 78) = 8.90, p < .001. The final equation was significant, R2 = .38, F(7, 85) = 6.70, p < .001. Perceived stress in pandemic-specific situations and self-efficacy were significant predictors for well-being. Gender was no longer significant. On average, a one-unit increase in perceived stress in pandemic-specific situations was associated with a decrease of 4.20 points on the well-being score, a one-unit increase in self-efficacy was associated with an increase of 5.55 points on well-being (assuming each time that the other predictors remained constant).

Table 2. Regression results for well-being with perceived stress and self-efficacy.

Table 3. Regression results for well-being with stressor occurrence and self-efficacy.

When considering the occurrence of stressors in the second regression, in Step 2 there was also a significant increase in variance, ΔR2 = .36, F(4, 78) = 13.03, p < .001. The final equation was significant, R2 = .46, F(7, 85) = 9.29, p < .001. Occurrence of everyday stressors and self-efficacy were significant predictors for well-being. On average, a one-unit increase in the occurrence of everyday stressors was associated with a decrease of 12.70 points on well-being, a one-unit increase in self-efficacy was associated with an increase of 4.51 points on well-being.

Discussion

Our study showed that about half of pupils with hearing/listening impairment reported low well-being during the third German COVID-19 wave in May 2021. Also using the KIDSCREEN-10, this represents a similar proportion of burdened children during the pandemic as in the nationwide German COPSY study assessments in spring 2020 and winter 2020/2021 (Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022a). Contrary to expectation, children with hearing/listening impairment were not affected more than peers with typical levels of hearing/listening. Yet, over a year after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, our results indicate a high burden among children and adolescents with hearing/listening impairment that fit to the global evidence on mental health worsening following COVID-19 measures and lockdown for children and adolescents (for national surveys: Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022b; Vizard et al., Citation2020; for children with hearing/listening impairment: Ariapooran & Khezeli, Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2021; for a review and meta-analysis: Ma et al., Citation2021). A slight improvement was documented in Germany in autumn 2021 (with about one-third of participants reporting low well-being) that the authors attributed to lower infection rates, vaccination, and the easing of the COVID-19 restrictions (Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022a). Furthermore, similar to Engel de Abreu et al. (Citation2021) or Ravens-Sieberer et al. (Citation2021) for the early phase of the pandemic, in our study well-being was not associated with age and also the type of hearing impairment (D/HH, APD) was not associated with well-being. In line with Engel de Abreu et al. (Citation2021), girls reported lower well-being compared to boys. However, in our study gender was not associated with well-being when stressors and resources were also taken into account.

With regard to stressors, not surprisingly, situations frequently experienced were related to the COVID-19 pandemic, especially the advice to stay at home and social distancing, as well as difficulties understanding what others were saying and as general daily situation problems doing homework. Following transactional conzeptualizations of stress (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), the degree of perceived stress is to be considered. Thus, in line with expectations, our study showed only moderate positive associations between the occurrence of events in the past year and the perceived stress of these situations for both everyday stressors and hearing-specific situations. In contrast, for pandemic-related stressors, the correlation was near to zero. Methodological constraints on variance for pandemic-related stressor occurrence could be a reason for the absence of an association. However, since the variance was only slightly lower than for everyday stressor occurrence, the stressor domain itself may also make a difference for appraisals.

In line with pre-pandemic data (Eschenbeck et al., Citation2017), on average, children with hearing/listening impairment reported low to moderate perceived stress levels. Also replicating prior results (Eschenbeck et al., Citation2017), on average, common everyday situations (in particular problems doing homework and an argument with a friend) were perceived as more stressful than hearing specific situations (problems with communication). Contrary to expectation, pandemic-related stressors were perceived least stressful; even overall they were frequently experienced. Possibly, by some children pandemic-related situations were appraised as rather collective, environmental events that affect everyone. This might promote social connectedness, foster adaptation, and reduce stress (Slavich et al., Citation2022).

Regarding the associations between well-being, stressors, and self-efficacy, consistent with pre-pandemic research (Cosma et al., Citation2020), stressors were negatively related to well-being. This applied for perceived stress as well as stressor occurrence and for all three stressor domains, i.e. general daily situations, hearing-specific situations, and pandemic-related situations. Self-efficacy, on the other hand, correlated positively with well-being (Andretta & McKay, Citation2020). Thereby, these cross-sectional relationships can generally be reciprocal, amplifying negative or positive effects. Stressors can result in poorer well-being, just as impaired well-being can lead to more vulnerability to experience stress (Lee et al., Citation2018). Alike self-efficacy can strengthen well-being, just as well-being can promote self-efficacy (Helseth & Misvaer, Citation2010; Otto et al., Citation2017).

Interestingly, the regression results indicated that especially the perceived stress level in the pandemic-related situations were negatively associated with well-being, and with regard to stressor occurrence the everyday stressors were relevant. That means for the well-being of children during the pandemic, with regard to pandemic-related situations it was the perceived stressfulness, however, for everyday stressors the presence itself was decisive. Moreover, contrary to expectation, the association with well-being was little larger for stressor occurrence than for perceived stress. Self-efficacy was an overall relevant resource for well-being. Children and adolescents with hearing/listening impairment who reported a higher self-efficacy generally showed higher well-being during the pandemic. Since the positive correlation between well-being and self-efficacy has been demonstrated, health-promoting measures to strengthen self-efficacy are particularly useful here.

Strenghts, limitations, and future research

The major strength of this study on self-reported well-being, stressors, and resources during the COVID-19 pandemic is its focus on children and adolescents who are D/HH or with APD, two potentially vulnerable cohorts who are particularly affected by COVID-19 restrictions and who have been rarely studied so far. Nevertheless, our study has some limitations that should be noted when interpreting the results. First, the sample was only recruited at one specialist school and may not be representative for the general population of children and adolescents with hearing/listening impairment in Germany. For example, school-related factors such as differences in learning environments, access to technology or hearing services (Schafer et al., Citation2021) or perceived school climate (Steinmayr et al., Citation2018) may also contribute to pupils well-being during the pandemic. Future studies could expand recruitment and include more schools and also children with hearing/listening impairment attending mainstream schools to address both, school-related and individual factors for well-being. Moreover, due to the sample size and limitations in terms of power, it was not advisable to test interrelations between the predictors in more detail. Therefore, future studies with a larger sample could investigate whether self-efficacy revealed as a stress buffer (Burger & Samuel, Citation2017). Also related to gender, more detailed analyses of (differential) associations of stressors and resources with well-being would be interesting. However, our participation rate of 90% was high and the sample size was larger than (Ariapooran & Khezeli, Citation2021) or comparable with (Wright et al., Citation2021) the few existing COVID-19-related studies among children and adolescents with hearing/listening impairment.

Second, teachers gave information on the presence of D/HH or APD diagnosis. More detailed information on the child’s deafness including, for example, audiometry data, age of hearing loss or modes of communication could not be recorded and would be interesting for future research. Including children who are D/HH and children with APD resulted in a heterogeneous sample which is why the type of hearing/listening impairment was analyzed as control factor to test whether effects differ for the different diagnoses. Undoubtedly D/HH and APD represent different problems of hearing or listening with, for example, distinct implications for diagnostic approaches or intervention (DGPP, Citation2013, Citation2015). The definition of APD is controversial (Moore, Citation2018; for a consensus see Iliadou et al., Citation2017). However, children attended the same school with an optimized listening environment. In the context of the pandemic, independent of the (auditory) disorder specificity, lacking visual/facial cues and a less clear pronunciation due to facemasks can make communication more difficult.

Third, data were from a cross-sectional design that does not allow causal conclusions. We also do not have pre-pandemic reference data for children who are D/HH and children with APD to study differences or changes in well-being. Future longitudinal studies are recommended. Fourth, our data were assessed in late spring 2021. This was not parallel in terms of time, but between the survey dates (winter 2020/2021, autumn 2021) of the German population-based COPSY study (Ravens-Sieberer et al., Citation2022b) that we used as a reference. However, comparable to winter 2020/2021 (second COVID-19 wave), in spring 2021 infection rates were high (third wave; Tolksdorf et al., Citation2021) and the schools were closed. Therefore, with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated constraints, we assume comparable times for children and adolescents.

Finally, with regard to psychometric properties, widely accepted and validated instruments were used to assess self-reported well-being, stress, and self-efficacy. For stress, the original scale was extended: pandemic-specific stressors and hearing-specific stressors were added; in addition to perceived stress stressor occurrence was recorded. Overall, reliability was good. Only for the assessment of stressor occurrence the internal consistencies were lower than .70. For this checklist 1- or 2-week test-retest reliability for the report of events in the past year would be more suitable than internal consistency. Until further examination, the results regarding stressor occurrence are to be treated with caution.

Conclusion and implications for the future

To date, few studies have examined the well-being of children who are D/HH or with APD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thereby, based on demands-resources models associations with stressful situations (including domains related to the pandemic, hearing/listening, and everyday) and self-efficacy as resource were studied. Overall the current findings indicate a high burden. Over half of the children and adolescents reported low well-being. While especially perceived stress in pandemic-related situations and the occurrence of everyday stressors were negatively related to well-being, self-efficacy showed a positive association with well-being. This implies that health promotion interventions can start with building resources like self-efficacy or programmes that help pupils cope well with stressful situations. At the same time, stressful situations as demands should also be considered in terms of whether they are appropriate and manageable for children or should be reduced or eliminated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2022). Using masks for in-person service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: What to consider. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.asha.org/practice/using-masks-for-in-person-service-delivery-during-covid-19-what-to-consider/

- American Speech-Language-Hearinge Association, ASHA. (2005). (Central) auditory processing disorders – The role of the audiologist. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.asha.org/policy/PS2005-00114/

- Andretta, J. R., & McKay, M. T. (2020). Self-efficacy and well-being in adolescents: A comparative study using variable and person-centered analyses. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105374

- Ariapooran, S., & Khezeli, M. (2021). Symptoms of anxiety disorders in Iranian adolescents with hearing loss during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03118-0

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

- Barkmann, C., Otto, C., Meyrose, A. K, Reiss, F., Wüstner, A., Voß, C., Erhart, M., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2021). Psychometrie und Normierung des Lebensqualitätsinventars KIDSCREEN in Deutschland. Diagnostica, 67(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000257

- Burger, K., & Samuel, R. (2017). The role of perceived stress and self-efficacy in young people's life satisfaction: A longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0608-x

- Castagnoli, R., Votto, M., Licari, A., Brambilla, I., Bruno, R., Perlini, S., Rovida, F., Baldanti, F., & Marseglia, G. L. (2020). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 882–889. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467

- Chen, X., Cai, Z., He, J., & Fan, X. (2020). Gender differences in life satisfaction among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(6), 2279–2307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00169-9

- Cheng, C., Barceló, J., Hartnett, A. S., Kubinec, R., & Messerschmidt, L. (2020). COVID-19 Government response event dataset (CoronaNet v.1.0). Nature Human Behaviour, 4(7), 756–768. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0909-7

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cosma, A., Stevens, G., Martin, G., Duinhof, E. L., Walsh, S. D., Garcia-Moya, I., Költő, A., Gobina, I., Canale, N., Catunda, C., Inchley, J., & de Looze, M. (2020). Cross-national time trends in adolescent mental well-being from 2002 to 2018 and the explanatory role of schoolwork pressure. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6S), S50–S58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.010

- Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. T., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3

- Engel de Abreu, P. M. J., Neumann, S., Wealer, C., Abreu, N., Coutinho Macedo, E., & Kirsch, C. (2021). Subjective well-being of adolescents in Luxembourg, Germany, and Brazil during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(2), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.04.028

- Eschenbeck, H., Gillé, V., Heim-Dreger, U., Schock, A., & Schott, A. (2017). Daily stress, hearing-specific stress and coping: Self-reports from deaf or hard of hearing children and children with auditory processing disorder. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 22(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enw053

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., & Lang, A. G. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

- Garg, S., Deshmukh, C. P., Singh, M. M., Borle, A., & Wilson, B. S. (2021). Challenges of the deaf and hearing impaired in the masked world of COVID-19. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 46(1), 11–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_581_20

- German Society of Phoniatrics and Pediatric Audiology, DGPP. (2013). Periphere Hörstörungen im Kindesalter (Leitlinie). [Peripheral hearing disorders in children (guideline).]. Retrieved October 24, 2022, from www.dgpp.de/cms/media/download_gallery/Hoerstoerungen%20Kinder%20lang.pdf

- German Society of Phoniatrics and Pediatric Audiology, DGPP. (2015). Auditive Verarbeitungs- und Wahrnehmungsstörung (Leitlinie). [Central auditory processing disorder (guideline).] Retrieved October 24, 2022, from www.dgpp.de/cms/media/download_gallery/ DGPP-Leitlinie-AVWS-2015.pdf

- Geweniger, A., Barth, M., Haddad, A. D., Högl, H., Insan, S., Mund, A., & Langer, T. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health outcomes of healthy children, children with special health care needs and their caregivers-results of a cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 10, 759066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.759066

- Grant, K. E., Compas, B. E., Stuhlmacher, A. F., Thurm, A. E., McMahon, S. D., & Halpert, J. A. (2003). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447

- Helseth, S., & Misvaer, N. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of quality of life: What it is and what matters. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(9-10), 1454–1461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03069.x

- Iliadou, V., Ptok, M., Grech, H., Pedersen, E. R., Brechmann, A., Deggouj, N., Kiese-Himmel, C., Śliwińska-Kowalska, M., Nickisch, A., Demanez, L., Veuillet, E., Thai-Van, H., Sirimanna, T., Callimachou, M., Santarelli, R., Kuske, S., Barajas, J., Hedjever, M., & Konukseven, O. (2017). A European perspective on auditory processing disorder – current knowledge and future research focus. Frontiers in Neurology, 8, 622. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00622

- Kiang, L., & Buchanan, C. M. (2014). Daily stress and emotional well-being among Asian American adolescents: Same-day, lagged, and chronic associations. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 611–621. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033645

- King, G., Seko, Y., Chiarello, L. A., Thompson, L., & Hartman, L. (2020). Building blocks of resiliency: A transactional framework to guide research, service design, and practice in pediatric rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(7), 1031–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1515266

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

- Lee, C–YS, Goldstein, S. E., & Dik, B. J. (2018). The relational context of social support in young adults: Links with stress and well-being. Journal of Adult Development, 25(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-017-9271-z

- Lohaus, A., Eschenbeck, H., Kohlmann, C.-W., & Klein-Heßling, J. (2018). Fragebogen zur Erhebung von Stress und Stressbewältigung im Kindes- und Jugendalter (SSKJ 3 – 8-R). In German stress and coping questionnaire for children and adolescents. Hogrefe.

- Lohaus, A., & Nussbeck, F. W. (2016). FRKJ 8-16 Fragebogen zu Ressourcen im Kindes- und Jugendalter [QARCA questionnaire to assess resources for children and adolescents]. https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2904835

- Ma, L., Mazidi, M., Li, K., Li, Y., Chen, S., Kirwan, R., Zhou, H., Yan, N., Rahman, A., Wang, W., & Wang, Y. (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.021

- Mann, M., Mcmillan, J. E., & Silver, E. J. (2021). Children and Adolescents with Disabilities and Exposure to Disasters, Terrorism, and the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Scoping Review. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01295-z

- Mikkelsen, H. T., Haraldstad, K., Helseth, S., Skarstein, S., Småstuen, M. C., & Rohde, G. (2020). Health-related quality of life is strongly associated with self-efficacy, self-esteem, loneliness, and stress in 14-15-year-old adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 352. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01585-9

- Moksnes, U. K., Eilertsen, M–EB, Ringdal, R., Bjørnsen, H. N., & Rannestad, T. (2019). Life satisfaction in association with self-efficacy and stressor experience in adolescents – self-efficacy as a potential moderator. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(1), 222–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12624

- Moore, D. R. (2018). Guest editorial: Auditory processing disorder. Ear & Hearing, 39(4), 617–620. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000582

- Nearchou, F., Flinn, C., Niland, R., Subramaniam, S. S., & Hennessy, E. (2020). Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes in children and adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228479

- Newland, L. A., Giger, J. T., Lawler, M. J., Roh, S., Brockevelt, B. L., & Schweinle, A. (2019). Multilevel analysis of child and adolescent subjective well-being across 14 countries: Child- and country-level predictors. Child Development, 90(2), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13134

- Otto, C., Haller, A–C, Klasen, F., Hölling, H., Bullinger, M., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2017). Risk and protective factors of health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: Results of the longitudinal BELLA study. PLoS One, 12(12), e0190363. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190363

- Patel, K. (2020). Mental health implications of COVID-19 on children with disabilities. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102273

- Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

- Radovanović, V., Šestić, M. R., Kovačević, J., & Dimoski, S. (2020). Factors related to personal resiliency in deaf and hard-of-hearing adolescents. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 25(4), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enaa012

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Devine, J., Gilbert, M., Reiss, F., Barkmann, C., Siegel, N. A., Simon, A. M., Hurrelmann, K., Schlack, R., Hölling, H., Wieler, L. H., & Kaman, A. (2022a). Child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of the three-wave longitudinal COPSY Study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 71(5), 570–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.06.022

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Rajmil, L., Herdman, M., Auquier, P., Bruil, J., Power, M., Duer, W., Abel, T., Czemy, L., Mazur, J., Czimbalmos, A., Tountas, Y., Hagquist, C., & Kilroe, J. (2010). Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: A short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 19(10), 1487–1500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M., Devine, J., Schlack, R., & Otto, C. (2022b). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(6), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M., Otto, C., Devine, J., Löffler, C., Hurrelmann, K., Bullinger, M., Barkmann, C., Siegel, N. A., Simon, A. M., Wieler, L. H., Schlack, R., & Hölling, H. (2021). Quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a two-wave nationwide population-based study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01889-1

- Robert Koch-Institut. (2021). Epidemiologisches Bulletin 13/2021. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2021/Ausgaben/13_21.pdf?__blob = publicationFile

- Schafer, E. C., Dunn, A., & Lavi, A. (2021). Educational challenges during the pandemic for students who have hearing loss. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52(3), 889–898. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_LSHSS-21-00027

- Slavich, G. M., Roos, L. G., & Zaki, J. (2022). Social belonging, compassion, and kindness: Key ingredients for fostering resilience, recovery, and growth from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 35(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1950695

- Steinmayr, R., Heyder, A., Naumburg, C., Michels, J., & Wirthwein, L. (2018). School-related and individual predictors of subjective well-being and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02631

- Tolksdorf, K., Buda, S., & Schilling, J. (2021). Aktualisierung zur “Retrospektiven Phaseneinteilung der COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland”. https://doi.org/10.25646/8961

- Viner, R., Russell, S., Saulle, R., Croker, H., Stansfield, C., Packer, J., Nicholls, D., Goddings, A–L, Bonell, C., Hudson, L., Hope, S., Ward, J., Schwalbe, N., Morgan, A., & Minozzi, S. (2022). School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(4), 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5840

- Vizard, T., Sadler, K., Ford, T., Newlove-Delgado, T., McManus, S., Marcheselli, F., Davis, J., Williams, T., Leach, C., Mandalia, D., & Cartwright, C. (2020). Mental health of children and young people in England, 2020. Wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey. Health and Social Care Information Centre, 1–53. Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://files.digital.nhs.uk/CB/C41981/mhcyp_2020_rep.pdf

- World Health Organization, WHO. (2021). COVID-19 strategic preparedness and response plan - operational planning guideline. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-WHE-2021.03

- Wright, B., Carrick, H., Garside, M., Hargate, R., Noon, I., & Eggleston, R. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on deaf children in the United Kingdom. International Journal on Mental Health and Deafness, 5(1), 26–36http://www.ijmhd.org/index.php/ijmhd/article/view/67.

- Zaidman-Zait, A., & Dotan, A. (2017). Everyday stressors in deaf and hard of hearing adolescents: The role of coping and pragmatics. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 22(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enw103