ABSTRACT

Background: We performed a systematic review to evaluate factors affecting uptake of rotavirus vaccine amongst physicians, parents and health system.

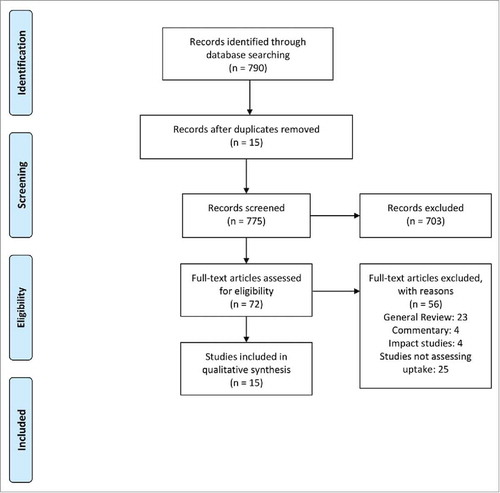

Methods: We identified 15 studies that met the inclusion criteria from 790 screened studies published between Jan 2005 to Jan 2016.

Results: Perceived severity of rotavirus disease, efficacy of vaccine and recommendation by health authorities positively influenced uptake of vaccine amongst health care providers. Routine and timely vaccination with routine vaccines and availability of rotavirus vaccine in public health programme facilitated uptake. Family income, parental education and employment status positively influenced the decision to vaccinate by parents. Concerns about safety, high cost, additional workload and logistic problems in acquiring vaccine stocks were perceived as barriers.

Conclusion: Improved awareness regarding the rotavirus vaccination amongst public and scientific community and strengthening of public health system for better and timely immunisation coverage are important factors to maximize uptake of rotavirus vaccine in India.

Introduction

Rotavirus is the most common cause of vaccine-preventable severe diarrhoea, responsible for 28% childhood cases worldwide.Citation1 Rotavirus disease was responsible for 197000 deaths in under-five population in the year 2011 which indicates that 23 children die due to this condition every hour.Citation2 In India, Rotavirus infection was found to be responsible for 34% of total deaths due to diarrhoea in under-five population with an estimated mortality of 4.14 deaths per 1000 live births in 2005.Citation3

To reduce the burden of rotavirus disease, WHO and other international organisations with support from GAVI have prioritized development of rotavirus vaccine and its introduction into immunisation schedules over the last decade.Citation4 Introduction of rotavirus vaccine into the national immunisation schedule of Europe and Americas was recommended by WHO in 2006.Citation5 This recommendation was extended worldwide in April 2009 after review of clinical trials conducted in Africa and Asia.Citation6 The efficacy of Rotateq as well as Rotarix is demonstrated to be more than 90% in high-income countries in West, but is found to be moderate to low in low and middle income countries.Citation7–Citation8 Despite the lower efficacy in Asian and African countries, the vaccine has substantial potential for disease prevention in these countries due to a high infection rate and round-the-year transmission of the rotavirus.

In India, rotavirus vaccines are being used by paediatricians in the private sector since last few years. An indigenously developed vaccine – Rotavac [Bharat Biotech] has been demonstrated to have protection against rotavirus disease comparable to the protection offered by other rota virus vaccines in high income countries.Citation9 Presently, Rotavac vaccine is being introduced in few states of India as a part of the public-health system driven universal immunisation programme.Citation10

As with any new service or product introduced in healthcare, introduction of a new vaccine is likely to encounter challenges. Crucially, there have been both positive and negative opinions regarding the need and usefulness of rotavirus vaccination amongst policy makers and health care providers.Citation11,Citation12 Risk of intussusception associated with the earlier rotavirus vaccine, modest efficacy of rotavirus vaccines in developing countries, presence of co-infections and role of WASH interventions in prevention of morbidity and mortality due to diarrhoea are potential factors that influence the decision for rotavirus vaccine use.Citation11 Issues related to provider as well as user perceptions and acceptability can be crucial in the success of the vaccine introduction. Additionally, readiness of the health system infrastructure and availability of resources can be potential influencers of vaccine uptake.

These and many other factors lead to the question about how rotavirus vaccine can systematically and effectively be introduced into the national immunisation program at scale. Some answers to this can be obtained from an analysis facilitators and barriers for uptake of rotavirus vaccine from available literature worldwide. With this context, we performed a systematic review of factors affecting uptake of rotavirus vaccine amongst parents, health care providers and health system.

Methods

This systematic review protocol was registered at PROSPERO with registration no CRD42016033742 and can be accessed at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO. We included studies that assessed awareness, attitudes and perceptions of physicians and parents regarding rotavirus vaccination, intention to vaccinate, perceived facilitators and barriers, compliance to recommendation for rotavirus vaccination. We also included operational research studies evaluating reasons for poor or incomplete vaccination with rotavirus. Studies related to clinical trials, immunisation policies, mass immunisation, were excluded as they were not relevant for the review.

The search strategy utilised various combinations of non-MeSH terms including ‘uptake’, ‘coverage’, ‘factors’, ‘access, ‘barrier’, ‘challenges’ and MeSH as well as non-MeSH terms for rotavirus vaccine. Literature search was conducted using United States National Library of Medicine, IndMed and Cochrane Database. The search strategy shown in Table 1S was used for search in United States National Library of medicine (Pubmed) database. Similar strategy was used for search in other databases. Original articles published from 1st Jan 2005 to 31st Jan 2016 were included. Apart from the published literature, reports from workshops, conferences were searched through given databases, Google and reference lists of the published papers. Studies published in languages other than English and animal studies were excluded. We did not include post-introduction evaluations of rotavirus vaccine as they mainly assessed vaccine effectiveness. One author independently screened titles and abstracts of the studies to select potentially relevant articles. Full texts of all the selected articles were obtained and were then screened by two authors independently based on predefined eligibility criteria for inclusion.

Table 1. Health care provider-related factors affecting uptake of rota viral vaccine.

Data extraction was completed for all the eligible studies using standardised data extraction form in Microsoft Excel. Factors related to uptake of rotavirus vaccination were captured under following four headings: Health provider related, parent related, health system related and vaccine related factors. In addition, limitations of the study were also captured. The data extraction was independently carried out by one author and was reviewed by a senior author. We used New Castle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessment of quality and bias.Citation13 Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of studies. In case of dispute, opinion of third reviewer was taken. As most of the identified relevant studies were qualitative in nature and reported minimum quantitative data, we did not attempt to conduct a meta-analysis.

Factors that affected uptake of rotavirus vaccine from the perspective of physician, parents or health system were considered as variables of interest. The variables were expressed as range of proportions, risk ratio and correlation co-efficient.

Results

A total of 775 titles and abstracts were screened through searching various databases out of which 71 full text articles were screened for eligibility and 15 studies were identified based on the predefined inclusion criteria. shows PRISMA flow chart for selection of studies. The descriptions of included studies is given in Table 2S.

Table 2. Health system -related factors for uptake of rota viral vaccine.

Eight of these studies were questionnaire surveys, either internet-based or telephonic, conducted amongst physicians or parents of the children. The rest were retrospective observational cohort studies, cross-sectional surveys and a prospective study. Six of these studies were conducted in United states, 3 in Canada, one in India, China, United Kingdom, Belgium, El Salvador, and Brazil each.

Quality assessment

The potential risk of bias assessment for included studies has been described in Table 3S-5S. Most of the cross sectional studies did not demonstrate comparability of non-respondents. Two out of three of the case control studies had controls selected from hospitals thus inducing a selection bias as the controls were not true representative of healthy population. All the included studies had well-defined study question or objective, defined target population, clearly described methods and analysis, description of limitations and major conclusions.

Table 3. Parent-related factors affecting uptake of rota viral vaccine.

We have broadly classified the factors into provider, user and system related.

Health care provider-related factors

There were five studies that evaluated perceptions of physicians regarding rotavirus vaccination. In four of these studies, the vaccine was better accepted among paediatricians (recommended by 70–88%) as compared to family physicians (46.1-55%).Citation14–Citation15 A greater proportion of paediatricians (66-83%) perceived a need for vaccination with rotavirus vaccine as compared to family physicians (28%).Citation15,Citation16,Citation18 Knowledge about the vaccine schedule was also greater in paediatricians as compared to family physicians. In one study conducted in Belgium, the risk of incomplete vaccination with rotavirus vaccine was found to be greater when the vaccine was being prescribed by family physicians as compared to paediatricians (OR 6.67 vs.1.43).Citation17

As shown in , perceived need for vaccination (RR = 5.81) and perceived efficacy of vaccine (RR = 1.45-4.13) were found to be strong factors influencing use of rotavirus vaccine amongst health care providers in Canadian, American as well as Indian studies.Citation14–Citation18,Citation19 Health care providers who perceive that rotavirus vaccine is a severe disease and had experience of treating severe gastroenteritis in their practice were more likely to prescribe rotavirus vaccine. Recommendation by health authorities was considered important for decision making by health care providers in three of the included studies.Citation14–Citation16

On the other hand, barriers perceived by health care providers while using rotavirus vaccine were mainly related to logistic or vaccine safety issues – complexity of recommendations by health authorities, upfront cost to purchase vaccine and lack of reimbursement.Citation15,Citation17 These factors are pertinent to vaccine being available in the private health system in industrialised countries and may not be applicable if the vaccine becomes available in the public health system of LMIC and is available of free of cost. Adding another vaccine to already overburdened schedule of vaccines (OR = 0.17-0.47), unwarranted burden of work (OR = 0.34) and obtaining adequate supplies of vaccines (OR = 0.65) were logistic issues found in two American studies. Additionally, withdrawal of RotaShield from US market due to associated risk of intussusception (OR = 0.38-0.45) and time taken to discuss safety with parents was considered as barriers for use of rotavirus vaccine by providers in US.Citation15,Citation16

There was one study conducted in Indian paediatricians which reflected the perceptions of health providers in India regarding the use of rotavirus vaccine. In this study, 91.4% paediatricians relied upon the recommendations by Indian Academy of Paediatrics for prescribing rotavirus vaccine. Availability of rotavirus vaccine in the public health system was considered as a major facilitator as 92.2% paediatricians said that they would routinely prescribe the vaccine if it is available in the public health system. Concerns about vaccine safety were expressed by 45.5% of paediatricians in this study.Citation14

Health system-related factors

Health system-related factors were evaluated based on studies conducted amongst health care providers and studies analysing one or more factors influencing uptake of rotavirus vaccine ().

In US, the vaccine was almost 1.5 to 2 times more likely to be administered in health maintenance organisations, hospital-based practices and community health centres as compared to private practice. Practices with 10 or more providers were 1.9 times more likely to administer rota vaccine as compared to practices with 3 or less providersCitation15,Citation16 indicating possibility that institutes with large number of providers follow certain uniform recommendations for rotavirus vaccination. The vaccine was most likely to be prescribed in Well-Baby clinics followed by paediatricians as compared to family physicians in two studies. In Canadian study,Citation19 59% of the paediatricians said that introduction of the vaccine into the public health system would be useful. In another American study, 73.5% pregnant women indicated that their babies would receive all vaccines that are available in the public health system (RR = 29.3).Citation20 These findings underline the importance of inclusion of rotavirus vaccine in universal immunization for its public health impact.

Coverage and timeliness of routine vaccination was found to have an impact on coverage of rotavirus vaccine. In two observational study conducted in US and El Salvador, coverage of rotavirus vaccine was found to be associated with coverage of routine vaccination.Citation21,Citation15 In Indian study, increased coverage of pneumococcal vaccine was found to be associated with increased uptake of rotavirus vaccine (RR = 13.2).Citation14 In a retrospective study based on vaccination data in US, children who received DTaP immunization within 24 to 32 weeks of age were 17.8 times more likely to receive vaccination with rotavirus vaccine as compared to children who received it after this age limit.Citation22 In a Brazilian study, coverage of rotavirus vaccine correlated with the timeliness of routine immunisation with DTP-HiB and difference in the coverage of rotavirus vaccine and DTP-HiB correlated with delay in DTP-HiB.Citation23 This is because rotavirus vaccine is not routinely recommended beyond 6–8months of age due to increased risk of intussusception.Citation22,Citation23

Parent-related factors

As seen in , the parent-related factors were reported in 3 studies conducted in Belgium, Canada and US. In an American study, 67% parents expressed a positive intention to vaccinate their children with rotavirus vaccine and it was associated with 9.78 more likelihood of the chid receiving rotavirus vaccine.Citation24 In two other studies conducted in Canada and Belgium, 74% and 92.2% parents recommended and vaccinated their children with rotavius vaccine.Citation17–Citation20 Education status of fathers and employment status of both parents were found to be associated with increased likelihood of the child receiving rotavirus vaccine in Belgium study.Citation17

Canadian and Belgian studies showed that children in families with high income had greater odds of receiving rotavirus vaccination. However, these are studies from high income countries and in both these studies; the vaccine was not included in public funded programme. The findings are likely to be replicated in private sector of LMIC as well where uptake is largely decided by affordability of the vaccine. The type of residence in metro, urban, semi-urban or rural setup was not found to influence coverage of rotavirus vaccine in studies conducted in United States and China.Citation15,Citation25

In the American and Canadian studies, personal normative beliefs (parents’ perceptions of the moral correctness of having their child vaccinated) positively impacted parents’ decision to vaccinate whereas subjective norms (parents’ perceptions that significant others will approve rotavirus vaccination) was not consistently associated with positive intention of parents to vaccinate.Citation19,Citation20 Recommendation by health care providers and health authorities was found to be associated with increased parents’ intention to vaccinate children with rotavirus vaccine. In Canadian study, information about rota virus vaccine from media which were internet websites mainly acted was associated with reduced intention to vaccinate by parents.

Other factors

Oral mode of administration was found to be a facilitating factor in both parent as well as physician surveys.Citation19,Citation20,Citation23 In both types of studies, 49.2 to 60% of respondents considered cost to purchase the vaccine as a barrier to vaccinate.

Among child-related factors, first child in the family was more likely to be vaccinated as compared to children with 3 or more siblings.Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation23 In the Belgian study, attendance at a professional daycare in the first year of life was associated with increased the likelihood of vaccination.Citation17 Race and gender of the child were not found to influence the intention to vaccinate ().

Table 4. Vaccine-related and social/family-related factors for uptake of rota viral vaccine.

In a small prospective study conducted in NICU settings, coverage of rota vaccine was 33% as compared to 80–87% coverage for all other routine immunisation due to the policy of rota vaccination at discharge for NICU infants. This was to prevent nosocomial transmission of rota vaccine virus.Citation26 Another study was conducted by Jaque et alin NICU settings to evaluate if administration of rota virus vaccine is a standard practice in NICU. In this study, 45 out of 56 NICUs had the standard practice of administering rotavirus vaccine. Lack of standard guidelines for controlling risk of infection transmission following rotavirus immunisation in NICU was found to a barrier.Citation27

Discussion

The review addresses many contextual, individual as well rotavirus vaccine specific determinants of rotavirus vaccine uptake from various global studies. Although only two of the studies were conducted in LMIC and a majority of these studies are from developed countries, the have some implications in the context of LMICs, including India. These studies have been conducted within few years after introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the country, but not all countries have rotavirus vaccine as part of public health program.

Studies conducted amongst parents indicate that positive attitude towards rotavirus vaccine, recommendation by health authorities, doctors and media plays major influence on decision making by parents regarding rotavirus vaccination. This is in consensus with recent literature on overall childhood vaccine uptake from developed countries.Citation28,Citation29 Parental education and socioeconomic status is found to affect vaccine uptake positively as well as negatively in different parts of the world. In developing countries like India and Bangladesh, parental education and socioeconomic status have been found to have positive influence on vaccine uptake.Citation30 Our findings suggest positive effect of parental education and high income on uptake of rotavirus vaccine. This may indicate better health seeking behaviour by educated and high income families. However, the issue of affordability for parents may be less important for public health immunisation program in India as the vaccine is made available free of cost to the families. None-the-less, this emphasizes need for large scale public awareness campaigns through media regarding the benefits of rotavirus vaccination.

Studies amongst health care providers indicate that awareness regarding rotavirus disease burden and vaccination physicians including need for vaccination, schedule and health authority recommendations is potential influencer for vaccine uptake. These findings may be more applicable for health care providers in private sector and before introduction of the vaccine in public health system. Indian health system is a mix of public and private service providers.. While immunization is a priority program for the public health system, due to large number of people accessing the private health sector, health care providers from private sector also play important role in overall success of immunisation.Citation31 However, awareness regarding need for rotavirus vaccination and vaccine schedule is also important for frontline health workers in public health system who are responsible for vaccination coverage at grass root level.Citation32 Thus, there is need for effective communication methods regarding rotavirus vaccination amongst all cadres of health care providers and frontline workers.

Although availability of rotavirus vaccine in public health system has been found to facilitate overall uptake of the vaccine amongst health care providers and parents in various studies; this also adds to the burden of existing vaccinations and logistic difficulties in vaccine supply and cold chain maintenance especially in remote rural places.Citation33 In a country like India, although the national coverage for basic vaccination is 62%, the coverage varies from state to state with lowest coverage in India's largest central states.Citation34,Citation35 Based on distributional impact of rotavirus vaccination in 25 GAVI countries, simply introduction of new rotavirus vaccine into the existing system would target the investments towards high income groups with good vaccination coverage.Citation36 Considering the higher mortality risk and better cost effectiveness of rotavirus immunisation in low income regions,Citation36 strengthening of the framework for national immunisation is necessary to maximize the health benefits due to rotavirus immunisation.

Timely coverage of routine immunisation is an important correlate of uptake of rotavirus vaccine given the criteria for age restriction.Citation22,Citation21 A modelling study by Patel et al, showed that the additional lives saved by removing age restrictions for rotavirus vaccination would in fact outnumber the potential excess vaccine-associated intussusception deaths.Citation37 Due to further evidence in this regard, the age restriction for rotavirus vaccine has been relaxed by WHO. Despite this, in India, IAP continues to use of age restriction of 8 months.Citation35 Delayed childhood vaccination is a known challenge in India.Citation38 In view of this, scaling up of routine immunisation and improved coverage of routine immunisation will increase opportunity to provide rotavirus vaccine to maximum number of children.Citation39

Concerns about safety of rotavirus vaccine and its association with intussusception was expressed by health care providers and parents in few studies probably in view of withdrawal of first Rotavirus vaccine in US.Citation16,Citation19,Citation14 Post-marketing studies on the newer vaccines have shown favourable risk benefit ratio of introduction of the vaccine in routine vaccination.Citation40,Citation41 This is despite the lower efficacy of vaccine in low and middle income countries. An extended cost effectiveness analysis by Verguet et al shows that public finance of rotavirus vaccine in India, can still offer financial risk protection amongst poor considering the reduction in mortality and herd immunity acquired by mass community vaccination.Citation42 Since risk of intussusception with Indian vaccine, Rotavac, is unknown; presently, sentinel surveillance for intussusception is being carried out in some parts of country [ongoing study]. Indian Council for Medical Research plans to utilise national rotavirus surveillance network for monitoring safety and impact of Rotavac in the health system.Citation43

Overall, certain facilitators and barriers identified in this review may not be specific for rotavirus vaccine per se but may be applicable for introduction of any new vaccine. At the same time, certain factors such as age restriction, issues related to vaccine safety are specific for rotavirus vaccine.

Although most of the included studies are from developed nations and there is dearth of such studies from low and middle income countries, we have attempted to draw conclusions which may be applicable in India. There is scope for more research in this regard in LMIC. The review does not include studies only assessing coverage of rotavirus vaccine and reviews from various expert groups in this regard. These are some of the limitations of this review.

None the less, the review gives an insight into certain important factors which may influence health care providers as well as parents’ decision to use rotavirus vaccine and determine uptake of rotavirus vaccine in health system. Lessons learnt from the available literature can inform policy makers and can help in successful introduction of rotavirus vaccine in India.

Conclusion

As India prepares to introduce rotavirus vaccine in routine vaccination, creating public and health care community awareness regarding rotavirus vaccination, strengthening of public health system in for timely and adequate coverage of routine immunisation, maintaining uninterrupted vaccine supply, training of human resources are essential steps to reap optimum benefits from rotavirus vaccination.

Abbreviations

| ASHA | = | Accredited Social Health Activist |

| DTaP | = | Diphtheria, Tetanus, acellular pertussis |

| DTP-HiB | = | Diphtheria Pertussis Tetanus- Hemophilus Influenza B |

| GAVI | = | Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation |

| IAP | = | Indian Association of Paediatricians |

| LMIC | = | Lower-Middle Income Countries |

| NICU | = | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| NTAGI | = | National Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation |

| PRISMA | = | Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis |

| PCV | = | Pneumococcal vaccine |

| SAGE | = | Strategic advisory group of Experts |

| UIP | = | Universal Immunisation Schedule |

| WHO | = | World health organisation |

| WASH | = | Water sanitation and hygiene |

Disclosure of potential conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dr. Jose Martines, Scientific Coordinator, CISMAC, University of Bergen , Centre for International Health for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, Brien KLO, Campbell H, Black RE. Childhood Pneumonia and Diarrhoea 1 Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet North Am Ed. 2013;381:1405–16. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6.

- Lanata CF, Fischer-walker CL, Olascoaga AC, Torres CX, Aryee MJ. Global causes of Diarrheal Disease Mortality in Children, 5 Years of Age: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72788. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072788.

- Morris SK, Awasthi S, Khera A, Bassani DG, Kang G, Parashar UD, Kumar R, Shet A, Glass RI, Jha P, et al. Bulletin of the World Health Organization Rotavirus mortality in India : estimates based on a nationally representative survey of diarrhoeal deaths. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;10(90):720–7. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.101873101873.

- Steele AD, Patel M, Parashar UD, Victor JC, Aguado T, Neuzil KM. Rotavirus vaccines for infants in developing countries in Africa and Asia: considerations from a world health organization-sponsored consultation. J Infect Dis. 2009;200 Suppl(Suppl 1):S63–9. doi:10.1086/605042.

- Rotavirus vaccines. Weekly epidemiological records. 2007;82(32):285–95. [accessed 2017 Dec 12]. http://www.who.int/wer/en/.

- Peter G, Aguado T, Bhutta Z, De Oliveira L, Neuzil K, Parashar U, Steele D, Mantel C, Wang S, Mayers G, et al. Detailed Review Paper on Rotavirus Vaccines presented to WHO -SAGE; April 2009. Available from http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/3_Detailed_Review_Paper_on_Rota_Vaccines_17_3_2009.pdf [updated 12.12.17 ].

- Lopman BA, Pitzer VE, Sarkar R, Gladstone B, Patel M, Glasser J, Gambhir M, Atchison C, Grenfell BT, Edmunds WJ, et al. Understanding reduced rotavirus vaccine efficacy in low socio-economic settings. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e41720. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041720.

- Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(2):136–41. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5.

- Bhandari N, Rongsen-chandola T, Bavdekar A, John J, Antony K, Taneja S, Goyal N, Kawade A, Proschan M, Kohberger R, et al. Effi cacy of a monovalent human-bovine (116E) rotavirus vaccine in Indian infants : a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet North Am Ed. 2014;383(9935):2136–43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62630-6.

- India’s rotavirus vaccine to combat diarrhoeal deaths launched. The Hindu. March 27, 2016 [accessed 2017 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indias-rotavirus-vaccine-launched/article8399919.ece.

- Panda S, Das A, Samanta S. Synthesizing evidences for policy translation: A public health discourse on rotavirus vaccine in India. Vaccine. 2014;32(S1):A162–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.037.

- Lodha R, Shah D. Prevention of rotavirus Diarrhea in India: Is Vaccination the Only Strategy?. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;49(June 16):441–3.

- Wells GA, Shea B, Connell DO, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. Our Research The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta analyses. Available from: http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/rtamblyn/ [updated 12.12.17].

- Gargano LM, Thacker N, Choudhury P, Weiss PS, Pazol K, Bahl S, Jafari HS, Arora M, Orenstein WA, Hughes JM, et al. Predictors of administration and attitudes about pneumococcal, Haemophilus influenzae type b and rotavirus vaccines among pediatricians in India: A national survey. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):3541–5. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.064.

- Panozzo CA, Becker-Dreps S, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M, Stormer T, Weber DJ, Brookhart MA. Patterns of Rotavirus vaccine uptake and use in Privately-Insured US Infants, 2006–2010. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):2006–10. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073825.

- Kempe A, Daley MF, Parashar UD, Crane LA, Beaty BL, Stokley S, Barrow J, Babbel C, Dickinson LM, Widdowson M-A, et al. Will Pediatricians adopt the New Rotavirus Vaccine?. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):1–10. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1874.

- Braeckman T, Theeten H, Lernout T, Hens N, Roelants M, Hoppenbrouwers K, Van Damme P. Rotavirus vaccination coverage and adherence to recommended age among infants in flanders (Belgium) in 2012. Eurosurveillance. 2014;19(20):1–9.

- Kempe A, Patel MM, Daley MF, Crane LA, Beaty B, Stokley S, Barrow J, Babbel C, Dickinson LM, Tempte JL, et al. Adoption of rotavirus vaccination by pediatricians and family medicine physicians in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):e809–16. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3832.

- Dube E, Gilca V, Sauvageau C, Bradet R, Bettinger JA, Boulianne N, Boucher FD, McNeil S, Gemmill I, Lavoie F. Canadian paediatricians’ opinions on rotavirus vaccination. Vaccine. 2011;29(17):3177–82. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.044.

- Morin A, Lemaître T, Farrands A, Carrier N, Gagneur A. Maternal knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding gastroenteritis and rotavirus vaccine before implementing vaccination program: Which key messages in light of a new immunization program?. Vaccine. 2012;30(41):5921–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.050.

- Suarez-Castaneda E, Burnett E, Elas M, Baltrons R, Pezzoli L, Flannery B, Kleinbaum D, Oliveira LH, de Danovaro-Holliday MC. Catching-up with pentavalent vaccine: Exploring reasons behind lower rotavirus vaccine coverage in El Salvador. Vaccine. 2015;33(48):6865–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.092.

- Krishnarajah G, Landsman-Blumberg P, Eynullayeva E. Rotavirus vaccination compliance and completion in a Medicaid infant population. Vaccine. 2015;33(3):479–86. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.059.

- Flannery B, Samad S, Tate JE, Danovaro-holliday C, Rainey JJ, States U, Program I, States U. HHS Public Access. 2016;31(11):1523–8. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.004.Uptake.

- Dubé E, Bettinger JA, Halperin B, Bradet R, Lavoie F, Sauvageau C, Gilca V, Boulianne N. Determinants of parents’ decision to vaccinate their children against rotavirus: Results of a longitudinal study. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(6):1069–80. doi:10.1093/her/cys088.

- He Q, Wang M, Xu J, Zhang C, Wang H, Zhu W, Fu C. Rotavirus vaccination coverage among Children Aged 2–59 Months: A report from Guangzhou, China. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):9–11. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068169.

- Hofstetter AM, Lacombe K, Klein EJ, Jones C, Strelitz B, Jacobson E, Ranade D, Wikswo ME, Bowen MD, Parashar UD, et al. Rotavirus vaccine uptake, shedding, and lack of nosocomial spread in infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit. OFID. 2015;2(Suppl 1):S447..

- Jaques S, Bhojnagarwala B, Kennea N, Duffy D. Slow uptake of rotavirus vaccination in UK neonatal units. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(3):F252. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-306107.

- Forster AS, Chorley AJ, Rockliffe L, Marlow LA V, Bedford H, Smith SG, Waller J. Factors affecting uptake of childhood vaccination in the UK: a thematic synthesis. Lancet North Am Ed. 2015;386:S36. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00874-0.

- Smith LE, Amlôt R, Weinman J, Yiend J, Rubin GJ. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35(45):6059–69. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.046.

- Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective : A systematic review of published literature, 2007 – 2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

- George MS, Negandhi P, Farooqui HH, Sharma A, Zodpey S. How do parents and pediatricians arrive at the decision to immunize their children in the private sector? Insights from a qualitative study on rotavirus vaccination across select Indian cities. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics. 2016;12(12):3139–45. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1219824.

- Barman D, Dutta A. Access and barriers to immunization in West Bengal, India: Quality matters. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2013;31(4):510–22.

- Shen AK, Fields R, Mcquestion M. The future of routine immunization in the developing world : challenges and opportunities. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2014;2(4):381–94..

- UNICEF in action, Immunisation, UNICEF India [accessed 2017 Dec 12]. http://unicef.in/Whatwedo/3/Immunization.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. India National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) Government of India. 2017:199–249. Available from http://rchiips.org/NFHS/nfhs4.shtml.

- Rheingans R, Atherly D, Anderson J. Distributional impact of rotavirus vaccination in 25 GAVI countries: Estimating disparities in benefits and cost-effectiveness. Vaccine. 2012;30(SUPPL. 1):A15–23. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.018.

- Patel MM, Clark AD, Sanderson CFB, Tate J, Parashar UD. Removing the age restrictions for Rotavirus vaccination: A Benefit-Risk modeling analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(10):e1001330. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001330.

- Shrivastwa N, Gillespie BW, Lepkowski JM, Boulton ML. Vaccination timeliness in Children Under India's Universal immunization program. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):955–60.

- Megiddo I, Colson AR, Nandi A, Chatterjee S, Prinja S, Khera A, Laxminarayan R. Analysis of the Universal Immunization Programme and introduction of a rotavirus vaccine in India with IndiaSim. Vaccine. 2014;32(S1):A151–61. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.080.

- Desai R, Cortese MM, Meltzer MI, Shankar M, Bs MB. Potential Intussusception Risk versus benefits of Rotavirus Vaccination in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32: 1–7. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e318270362c.

- Ledent E, Lieftucht A, Buyse H, Sugiyama K. Post-Marketing Benefit – Risk assessment of Rotavirus Vaccination in Japan : A Simulation and Modelling analysis. Drug Saf. 2016;39(3):219–30. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0376-7.

- Verguet S, Murphy S, Anderson B, Arne K, Glass R, Rheingans R. Public finance of rotavirus vaccination in India and Ethiopia : An extended cost-effectiveness analysis. Vaccine. 2013;31(42):4902–10. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.014.

- Mathew MA, Venugopal S, Arora R, Kang G. Leveraging the national rotavirus surveillance network for monitoring intussusception. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53(7):635–8. doi:10.1007/s13312-016-0901-5.