ABSTRACT

Background: The prolonged effect of allergen immunotherapy is unknown, especially in older patients. Objective: The three-year effect of sublingual allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) to grass pollen on elderly patients with allergic rhinitis was analyzed.

Methods: Thirty-eight elderly patients (63.18 ± 3.12 yrs.) underwent AIT to grass pollen, were monitored for three years and were compared to a placebo group. AIT was performed with the use of an oral Staloral 300 SR grass extract (Stallergens Greer, London, UK) or a placebo. Symptoms and medication scores, represented by the average adjusted symptom score (AAdSS), the serum level of IgG4 to Phl p5 and the quality of life were assessed immediately after AIT and three years later. Results: After AIT, the AAdSS was significantly decreased and remained lower than in the placebo group during the three years after AIT. Serum-specific IgG4 against Phl p5 increased during the AIT trial in the study group. For the three years of observation after AIT, there were no significant changes in specific IgG4 levels against the analyzed allergens in comparison to the results immediately after AIT. The quality of life, based on the Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire, was significantly decreased in patients who received AIT, from 1.83 (95%CI: 1.45–1.96) to 0.74 (95%CI: 0.39–1.92) (p < 0.05) to 0.82 (95%CI: 0.45– 1.04) three years after AIT.

Conclusion: A prolonged positive effect after AIT to grass pollen was observed in elderly patients with allergic rhinitis. Further trials are needed to confirm this effect.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is an important problem worldwide.Citation1 The prevalence of allergic rhinitis depends on many factors, including geographical area, lifestyle, level of economic development of the region where the patient lives and age range. The guidelines addressing the diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis are rarely focused on elderly patients. However, the elderly frequently complain of nasal disorders, including allergic rhinitis. Allergic rhinitis has a profound negative affect on quality of life.Citation1,Citation2

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) has provided a safe and effective treatment method, particularly for allergic rhinitis.Citation3,Citation4 Grass pollens are the major allergens for patients with allergies, and there have been several randomized controlled immunotherapy trials showing a high degree and efficacy of the treatment.Citation5–Citation8 These studies have been based primarily on the young population, and few have focused on elderly patients.Citation9,Citation10,Citation11 There remain many questions as to whether immunotherapy can produce sufficient prolonged allergen tolerance in patients with immunosenescence. According to the present knowledge, the prolonged effect of AIT depends on many factors, including the cumulative dose of AIT and the clinical type of allergy. The second problem is the evaluation of AIT efficiency. It must always include a measurement of the symptoms and the use of concomitant medications, which represent the primary outcome for example: combined symptoms medication score, only symptoms score average adjusted symptom score, quality of life and others. As patients suffer the clinical manifestations, patient-rated scores are preferred as a primary outcome. While validation of scores is encouraged, it has to be noted almost all scores used have not yet been validated.Citation3,Citation4

The objective of this study is to evaluate the clinical effect of sublingual allergen specific immunotherapy to grass pollen on elderly patients with allergic rhinitis three years after therapy was discontinued.

Results

Clinical results

After 36 months of AIT to grass allergy, a significant effect was observed based on the AAdSS when compared to the treatment and the placebo group. During the next three years of observation, the AAdSS remained at a low level, significantly lower than that of the placebo group. The results are shown in .

Table 1. Efficacy of SLIT during therapy and three-year observation in comparison to placebo.

The post hoc analysis of the TCS showed that it was significantly decreased after three years of AIT and remained at a low value for another three years of observation in the active group. The results are shown in .

Table 2. Decrease in the TRS score during observation.

Quality of life

The quality of life, based on the RQLQ, was significantly increased in patients who received AIT from 1.83 (95%CI: 1.45–1.96) to 0.74 (95%CI: 0.39–1.92) (p < 0.05), and it remained at a constant level: 0.82 (95%CI: 0.45– 1.04) after three years of follow-up.

In the placebo group, the quality of life was significantly lower, at a constant level of 1.79 (95%CI: 1.05–2.31) during the entire observation.

Immunological markers

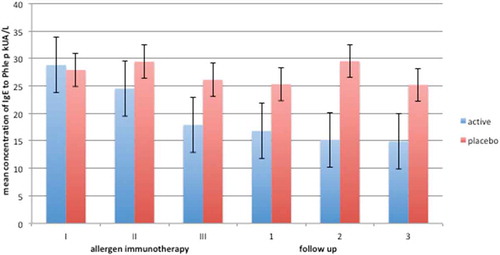

During the AIT trial, serum specific IgE against Phl p5 were lower in the study group than in the placebo group, and remained at comparably low levels three years after AIT ().

Figure 1. Decrease in phleum pratense IgE levels compared in placebo during three years of immunotherapy (I-III and three years of follow up(1-3).

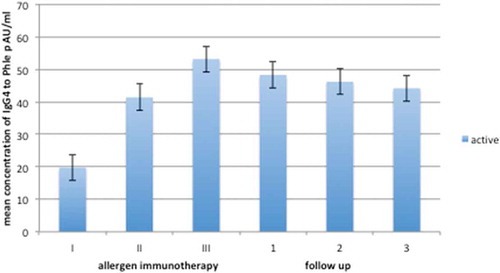

Serum specific IgG4 against Phl p5 increased during the AIT trial in the study group. During the three years of follow-up, the levels of IgG4 decreased slightly but not significantly in comparison to the results immediately after AIT (). There was no analysis of IgG4 in the placebo group due to constant and very low levels of IgG4 against the analyzed allergen.

Discussion

The long-term effects of allergen-specific immunotherapy have been rarely evaluated.Citation12–Citation14 There remains an insufficient quantity of data regarding allergen-specific immunotherapy in elderly people, and only one study has confirmed a prolonged effect of AIT in the elderly.Citation15 However, as mentioned previously, the need for this type of treatment is clear and has been confirmed according to new EAACI recommendations concerning AIT.Citation4

Based on our results, it appears that the prolonged efficacy after discontinuation of AIT to grass pollen was good and was similar to the effect in the younger group. The AAdSS score, as the primary endpoint of our analysis, decreased significantly during AIT in the study group, but it remained at low levels three years after AIT was discontinued. These results are comparable to those of other studies that include similar parameters, such as various configurations of symptoms and medication scores in younger patients after AIT to grass pollen.Citation15,Citation16

Another confirmation of the long-term efficiency of AIT is the significant improvement in the TCS based on the analysis of only the rhinitis domain as the primary endpoint of our study. This result is important for elderly patients because nasal problems significantly reduce quality of life.Citation17

The increase in IgG4 and decrease in IgE for Phleum pratense during and after AIT were conclusive and were similar to observations of other authors in the younger group of allergic patients.Citation18

The main limitation of the study is the relatively small group of analyzed patients. However, we used a more reliable parameter for evaluation, the AAdSS, according to previous recommendations. Therefore, all the results obtained during AIT were recalculated, possibly affecting the final results. However, these more modern assessment tools may have influenced the more reliable and critical results, as recommended by other authors.Citation19

We also did not take into account the effect of individual pollen seasons on our results. However, the trends of the results observed in the following years between the study group and the placebo group were always different and stable during the entire observation period.

Conclusion

The positive effect obtained in the course of AIT to grass pollen was sustained after AIT, providing a substantial advantage to elderly patients. Thus, this method of therapy may be beneficial in older people.

Material and methods

Study design

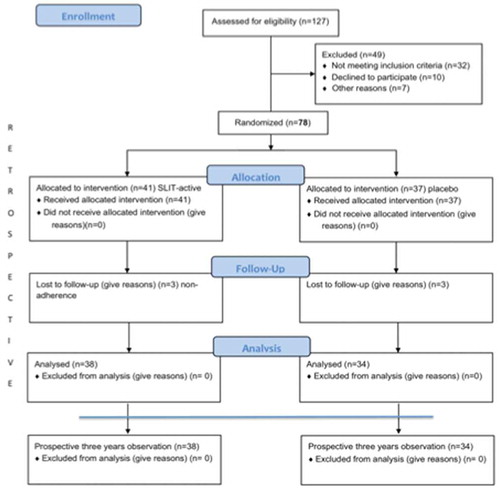

The project was designed as a partly retrospective and partly prospective observation of patients who underwent three years of co-seasonal allergen sublingual immunotherapy (randomized, double-blind, placebo control), followed by three years of further follow-up (prospective). For the prospective observations, patients were included in the study after completing AIT or symptomatic treatment in 2013. The patients were asked to keep a diary during the entire three-year observation period from 2013–2016. Every year during grass pollen season, specific IgE and IgG4 for Phleum pratense were monitored. All the results were compared to the baseline diagnostic results before the start of AIT (baseline). The number of participants who completed the study is shown in . The study was approved by the local ethics committees, and all the patients signed informed consent forms. This study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov as trial no. NCT01605760. The results of the first three years of the study (during AIT) were recalculated and used in the retrospective analysis as described below.

Participants

Thirty-eight elderly patients (study group) who underwent AIT to grass pollen three years prior and thirty-four patients who received placebo were included for further observation. The inclusion criteria were:

moderate or severe, intermittent allergic rhinitis according to Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA)Citation1

a positive skin prick test (SPT) to Phleum pratense and allergen-specific IgE to Phl p5

positive nasal provocation test with grass pollen extract.

Patients with any of the following characteristics were excluded: hypersensitivity to other allergens, non-allergic rhinitis (especially senile or vasomotor rhinitis) and severe non-stable diseases (especially bronchial asthma). However, stable coronary disease, diabetes, arterial hypertension and well-controlled, mild or accidental atopic bronchial asthma were permitted.

The characteristics of the groups are presented in . During AIT, all the patients were individually randomized in equal numbers to one of two “parallel” groups, either the active or the placebo treatment groups, using a double-blind method ().

Table 3. Characteristics of the patients who completed follow-up.

Intervention

The study group was treated with sublingual allergen immunotherapy co-seasonally (January-May) for three consecutive years. The patients were randomly selected to receive an oral Staloral 300 SR 5 grass pollen mixture extract solution of Phleum pratense, Dactylis glomerata, Anthoxanthum odoratum, Lolium perenne, and Poa pratensis (Stallergen, Antony, France) or the placebo (). The recruitment period was limited to three months (October-December). AIT was performed with a build-up schedule over four days (30–60-120–240 IR), as suggested by the manufacturer, starting in the month of January. A maintenance dose of 240 IR was then administered 5 times a week until the end of May. Each dose had to be taken in the morning before breakfast, and the allergen drops had to be kept under the tongue for at least 2 min before swallowing. Using this schedule, an average cumulative dose of 225 μg of Phl p5 was administered to each patient undergoing active treatment for all three years of the study. The Staloral and placebo were dispensed in drops from bottles with identical appearance. These treatments were pre-packaged in bottles and consecutively numbered for each participant according to the randomization schedule. Each patient was assigned an order number and received the box corresponding to the pre-packaged bottles. The volume of residual SLIT medication was assessed for every patient.

Symptomatic treatment

The patients were allowed to use the following drugs: antihistamine (5 mg levocetirizine tablets), intranasal corticosteroid (mometasone), topical ocular antihistamine drops (ebastine) and a 4 mg tablet of methylprednisolone. Other anti-allergic drugs were not permitted during the observation period.

Outcomes

Assessment of efficacy

Symptoms and medication score

The patients were monitored for their allergic clinical symptoms and medication use from May 2013 to July 2016 after AIT was discontinued. All the symptoms and medication scores obtained during the AIT trial (2011 – 2013) were recalculated post hoc, according to the method described below.

The patients recorded their nasal and ocular symptoms in terms of the medication used every day during the observation period (three years of the trial and three years of post-observation). Four nasal symptoms (sneezing, rhinorrhea, pruritus and congestion) and two ocular symptoms (pruritus and tearing) were monitored. Each day, the patient rated the severity of each individual symptom over the past 24 h on a four-point scale: 0 = no symptoms; 1 = mild symptoms; 2 = moderate symptoms; and 3 = severe symptoms.Citation11

The rescue medication score was based on WAO recommendations: 1 point for antihistamines, 2 points for nasal corticosteroids and 3 points for oral corticosteroids.Citation11

The symptoms and medication scores were presented as the average adjusted symptom score (AAdSS). The AAdSS was accepted for use as a primary end-point in rhinoconjunctivitis allergen immunotherapy trials.Citation19 This score included the nasal and ocular total symptoms score associated with grass allergy as the rhinoconjunctivitis total symptoms score (RTSS), which can be adjusted for the use of symptomatic treatment.Citation19 Additionally, a post hoc analysis was performed with the total combined rhinitis score (TCS), which is the sum of the rhinoconjunctivitis daily symptom score (DSS) and the daily medication score (DMS) averaged over the entirety of every grass pollen season (May-August).

Quality of life

The patient quality of life was evaluated with the Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire (RQLQ) score for adults, using questionnaires every year during the observation period.Citation20

Allergen-specific IgE and IgG4

At baseline, at the end of the AIT trial and every year after observation, serum-specific IgE, IgG and IgG4 levels to Phl p5 were determined by Immuno CAP (ThermoFisher Scientific, Uppsala, Sweden) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The results were considered positive when the sIgE concentration was greater than 0.35 kUA/l (according to the manufacturer’s instructions).

Skin prick tests (SPTs)

The SPT was performed at the start of the experiment using the allergen (Stallergens Greer, London, UK) Phleum pratense. Positive (10 mg/ml of histamine) and negative (saline) controls were also included. A positive skin test was defined as a minimum wheal diameter 3 mm greater than the negative control.Citation21

Statistics

The primary endpoint was the change from baseline in the mean AAdSS score and the TCS difference in the least square means in the label in comparison to the placebo. ANCOVA was used.

The second endpoint was the immunological response of IgG4 and IgE to Phl p5 during and after AIT. The LS mean changes from baseline were analyzed. The Wilcoxon test was used to analyze the differences between the groups. The chi-square test was used to analyze the changes in quality of life.

The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica version 8.12 (SoftPol, Cracow, Poland). Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Crus AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, Zuberbier T, Baena-Cagnani CE, Canonica GW, van Weel C, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA)2008. Allergy. 2008;63:8–160.

- Greiner AN, Hellings PW, Rotiroti G, Scadding GK. Allergic rhinitis. Lancet. 2011;378:2112–2122. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60130-X.

- Jutel M, Agache I, Bonini S, Burks AW, Calderon M, Canonica W, Cox L, Demoly P, Frew AJ, O’Hehir R, et al. International consensus on allergy immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:358–568. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1300.

- Agache I, Angier L, Bonertz A, Dhami S, Rivas M, van Wijk RG, Halken S, Jutel M, Lau S, Pajno G, et al. Allergen immunotherapy guidelines. Part 2: recommendations. Eur Acad Clin Immunol (EAACI). 2017;1:1–167.

- Dhami S, Nurmatov U, Arasi S, Khan T, Asaria M, Zaman H, Agarwal A, Netuveli G, Roberts G, Pfaar O. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2017; doi:10.1111/all.13201.

- Walker SM, Pajno GB, Lima MT, Wilson DR, Durham SR. Grass pollen immunotherapy for seasonal rhinitis and asthma: a ranodmized, controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:87–93. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.112027.

- Klimek L, Uhlig J, Mosges R, Rettig K, Pfaar O. A high polymerized grass pollen extract is effcacious and safe in a randomized double-blind, placebo controlled study using a novel up-dosing cluster protocol. Allergy. 2014;69:1629–1638. doi:10.1111/all.12513.

- Dahl R, Kapp A, Colombo G, de Monchy JG, Rak S, Emminger W, Rivas MF, Ribel M, Durham SR. Efficacy and safety of sublingual immunotherapy with grass allergen tablets for seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:434–440. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.05.003.

- Asero R. Efficacy of injection immunotherapy with ragweed and birch pollen in elderly patients. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;135:332–335. doi:10.1159/000082328.

- Bozek A, Kolodziejczyk K, Krajewska-Wojtys A, Jarzab J. Pre-seasonal, subcutaneous immunotherapy: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled study in elderly patients with an allergy to grass. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116(2):156–161. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2015.12.013.

- Canonica GW, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bousquet J, Bousquet PJ, Lockey RF, Malling HJ, Passalacqua G, Potter P, Valovirta E. Recommendations for standardizationof clinical trials withAllergen specific immunotherapy for respiratory allergy. A statement of a World Allergy Organization (WAO) taskforce. Allergy. 2007;62:317–324. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01456.x.

- Eng PA, Reinhold M, Gnehm HP. Long-term efficacy of preseasonal grass pollen immunotherapy in children. Allergy. 2002;57(4):306–312.

- Didier A, Hj M, Worm M, Horak F, Sussman Gl. Prolonged efficacy of the 300IR 5-grass pollen tablet up to 2 years after treatment cessation, as measured by a recommended daily combined score. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;22(5):12. doi:10.1186/s13601-015-0057-8.

- Dominicus S. 3-years’ long-term effect of subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) with a high-dose hypoallergenic 6-grass pollen preparation in adults. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;44(3):135–140.

- Bożek A, Kołodziejczyk K, Kozłowska R, Canonica GW. Evidence of the efficacy and safety of house dust mite subcutaneous immunotherapy in elderly allergic rhinitis patients: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;1(7):43. doi:10.1186/s13601-017-0180-9.

- Didier A, Worm M, Horak F, Sussman G, de Beaumont O, Le GM, Melac M, Hj M. Sustained 3-year efficacy of pre- and coseasonal 5-grass-pollen sublingual immunotherapy tablets in patients with grass pollen-induced rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):559–566. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.022.

- Yilmaz Sahin AA, Corey JP. Rhinitis in the elderly. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2006;6:125–131.

- Klimek L, Schendzielorz P, Pinol R, Pfaar O. Specific subcutaneous immunotherapy with recombinant grass pollen allergens: first randomized dose-ranging safety study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(6):936–945. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.03971.x.

- Grouin JM, Vicaut E, Jean-Alphonse S, Demoly P, Wahn U, Didier A, de Beaumont O, Montagut A, Le Gall M, Devillier P. The average adjusted symptom score, a new primary efficacy end-point for specific allergen immunotherapy trials. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1282–1288. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03700.x.

- Tripathi A, Patterson R. Impact of allergic rhinitis treatment on quality of life. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:891–899.

- Heinzerling LM, Burbach GJ, Edenharter G, Bachert C, Bindslev-Jensen C, Bonini S, Bousquet J, Bousquet-Rouanet L, Bousquet PJ, Bresciani M. GA(2)LEN skin test study I: GA(2)LEN harmonization of skin prick testing: novel sensitization patterns for inhalant allergens in Europe. Allergy. 2009;64:1498–1506. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02093.x.