ABSTRACT

Background: Full vaccination coverage has been identified as the foundation for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from the childhood illnesses. However, a significant number of children do not get recommended vaccinations. The problem is much worse in low-income countries with varied figures and evidence gap. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess vaccination coverage and its predicting factors in one of the low-income country Ethiopia, particularly in northwest Ethiopia.

Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Northwest Ethiopia in 2016 on 846 children aged 12 to 23 completed months. Cluster sampling method was used. Mothers or caretakers were interviewed. SPSS version 20 was used for analysis.

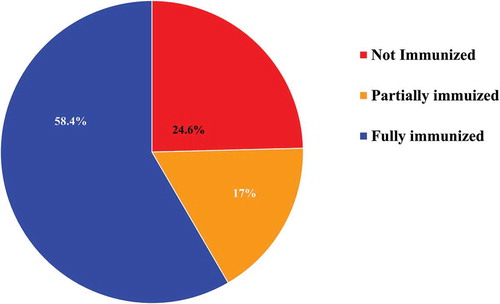

Results: In Northwest Ethiopia, full-vaccination coverage for the children aged 12–23 months was 58.4%, while 17% and 24.6% were partially vaccinated and not vaccinated at all respectively.

Child full vaccination status has a positive association with urban residence, having antenatal care visit, institutional delivery for the study child, vaccination site at health institutions, mothers who knows vaccination schedule of a catchment area, and mothers taking a child for vaccination even if the child is sick. However, mothers who ever-married and their travel time to the nearest vaccination site ≤ 30 minutes were negatively associated with child full-vaccination status.

Conclusion: Vaccination coverage in Northwest Ethiopia, East Gojam, is better than the national coverage. Yet, it is far below the plan. Encouraging antenatal care utilization, delivery at health institutions, and providing adequate information on child vaccination (including when to start, return and finish) for mothers would increase full-vaccination coverage.

Introduction

Vaccination is an introduction of a vaccine (a biological substance) in to the body, proposed to provoke a recipient’s immune system to produce antibodies or undergo other changes that offer future protection against specific infectious diseases. Immunization is the stimulation of changes in the immune system through which that protection occurs.Citation1

Vaccination coverage is the total number of infants who have received all required doses of a selected vaccine in the preceding 12 months divided by the annual target population multiplied by hundred. It is a key indicator of utilization of vaccination in a population and high coverage of routine vaccination is helpful for eradicating vaccine preventable diseases.Citation2

Child vaccination is one of the most successful and cost-effective public health interventions for common childhood illness like pneumonia, diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough and measles.Citation3 Nowadays, vaccination prevents nearly 3 million deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases like diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough and measles every year. Worldwide 12.9 million infants did not receive any vaccinations. Since 2010, global average vaccination coverage has increased by only 1%; only 86% of the children received their full course of routine vaccinations.Citation4,Citation5 In 2012, WHO endorsed Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) with a promise to ensure that no one misses out on vital vaccination by 2020. However, in 2015, more than 19 million children missed out the basic vaccination and the overall global vaccination coverage has stagnated.Citation6

The government of Ethiopia in its national infant vaccination program has introduced the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) in November 2011 and Monovalent Human Rotavirus Vaccine (RV) in October 2012. The PCV protects against Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria, which cause severe pneumonia, meningitis, and other illnesses. Rotavirus is a virus that causes gastroenteritis, an inflammation of the stomach and intestines.Citation7 In Ethiopia later 2011, for children under-one year of age, the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) vaccines included; one dose of BCG (at birth), 3 doses of pentavalent (DPT + HepB + Hib), 2 doses of Rotavirus, 3 doses Pneumococcus vaccine/PCV, 4 doses of OPV, and 1 dose of Measles. All these vaccines expected to be given just before celebrating one year of an infant birthday.Citation8

In Ethiopia vaccination coverage by DPT3 (Diphtheria, Pertussis and Tetanus) has shown increasing trend from 61% in 2010 to 77% in 2016.Citation4 Fully vaccinated children aged 12–23 months have increased from 14% in 2000 to 39% in 2016.Citation7,Citation9 A survey from Arba Minch explicated that nearly three fourth of children were fully vaccinated.Citation10 A study from Oromia Region Kombolcha Woreda portrayed that 24.2% of the children were not vaccinated, 52.9% partially vaccinated and 22.9% completely vaccinated.Citation11 A study conducted in Mecha district of West Gojam zone depicted about 49.3% of children aged 12–23 months were fully vaccinated, and 1.6% children were not started vaccination.Citation12

Different studies identified mothers’ characteristics such as educated mothers, mothers who have knowledge about the need and schedule of vaccines, fear of side effects, and having antenatal care (ANC) visits and health institution delivery were independent predictors for vaccination status of the child.Citation8, Citation10-Citation13

The Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (EFMoH) aimed to achieve full vaccination to 90% by 2015.Citation14–Citation16 However, as studies in different areas of the country indicated the goal of the national plan of expanded program on immunization (EPI) coverage did not achieve. Moreover, national or regional studies shows the overall circumstances, hence it may not reflect the current gaps and specifically local situations. Therefore, this study was conducted to identify existing gap at local situation. This study was conducted by the end of 2015; at the same time the plan ended too. The aim of this study was specifically to measure vaccination coverage and associated factors in the study area. Thus, this study can be used as a reference for health care providers, health care educators, policy makers, and future researchers in this and/or related fields.

Method and materials

This is a community-based cross-sectional study which was conducted in East Gojam Zone Northwestern Ethiopia in January 2016 to February 2016. The study population was children aged 12 to 23 in completed months.

Sample size and sampling

A total of 846 children aged 12–23 months were involved in the study. The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula with a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error and 49.3% full vaccination coverage rate in Mecha district 2013.Citation12 Furthermore, a 10% non-response rate and a design effect of 2 were considered.

The 2005 WHO EPI cluster sampling method was used for sample distribution. The numbers of clusters were 10 Kebeles (5 from urban and 5 from rural Kebeles of 5 districts of East Gojam Zone).Citation16 The determined sample was proportionally distributed to each cluster based on a number of eligible children in each cluster which was known after an enumeration of selected clusters. Using household identification number, eligible children were selected randomly.

Data collection

Data collection was undertaken by high school completed data collectors and supervised by diploma-level nurses from January 2016 to February 2016. Data was collected using questionnaire adopted from WHO and EDHSCitation9 and Amharic translated version. Mothers or caretakers were interviewed with pretested Amharic version questionnaire and asked to show vaccination cards for an indexed (selected) child and the data about vaccination were copied into the study tool (questionnaire). If vaccination card was lost, the mother’s/caretaker’s report was recorded. Presence of BCG scar was also observed and recorded. Each mother/care taker was asked questions specifically designed to be answered regarding children vaccination if she reported there was no vaccination card. To enable mothers/care takers to remember vaccine taken by the children & to minimize recall bias different strategies were informed by the data collectors, i.e.,; the site of vaccination given (oral, injection and scar) and at what age the child received specific vaccine and to differentiate routine vaccination schedules from campaign vaccination.

Data analysis procedures

Data entry, data cleaning, and coding was performed using SPSS version 20 and analyzed with the same software. To explain the study population in relation to relevant variables, frequencies and summary statistics were used. Predictors for the vaccinations of the children have been assessed by dichotomizing outcome variable (child vaccination status) into fully vaccinated and not fully vaccinated (partially vaccinated and not vaccinated children). Predictor variables having a p-value < 0.20 were taken into a multivariable logistic regression analysis to see associations between dependent and independent variables. All independent variables identified to significantly associate with the vaccination statuses of the children at bivariate analysis (p < 0.20) were taken into a multivariable analysis. Backward LR stepwise regression method was selected to assess the association between children’s full vaccination status and factors associated with their vaccination status. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all cases.

Operational definitions

Fully vaccinated: A child aged between 12–23 months who received a total of thirteen doses vaccines namely; one dose of BCG, at least three doses of pentavalent vaccine (diphtheria/D/, pertussis/P/, tetanus/T/, Haemophilus influenzae type b/HepB/and Hepatitis B (DPT, HepB, Hib), three doses of OPV (excluding polio zero given at birth), three doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 10 (PCV 10), two doses of Rota vaccine and a measles vaccine.Citation14,Citation17

Partially vaccinated: a child who missed at least one dose of the above mentioned (EPI) vaccines.Citation18

Not vaccinated: a child who does not receive any dose of the EPI vaccinesCitation19.

Coverage by card only: Coverage calculated with numerator based only on documented dose, excluding from the numerator those vaccinated by history.Citation20

Coverage by history: The vaccination coverage calculated with numerator based only on mother’s/caregiver’s report.Citation22

Dropout rate (DOR): The rate difference between the initial vaccine (BCG or Pentavalent I) and the final vaccines (Pentavalent III or Measles).Citation22

Pentavalent I Pentavalent III dropout rate = (PI – PIII)*100/PI

BCG Measles Dropout rate = (BCG – Measles)*100/BCG

Results

In this study, a total of 830 mothers of children aged between 12 – 23 months old were participated, which made 98.11% response rate. Among the total 830 children, more than half were boys (53.5%). The mean age of participants was 16.39 ± 3.75 months. Moreover, more than quarter of children (28.7%) were firstborn in the order of birth for their family. More than half of the children (53.1%) were from urban. The mean age of the mothers was 28.46 ± 5.59 years old. Besides, the majority of them (82.65%) were housewives and married (89%). More than half of the mothers (56.9%) had no education ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers and index children aged 12 – 23 months, East Gojam Districts Northwest Ethiopia. (N = 830).

Access to a health facility, vaccination service and utilization

The majority (88.7%) of the mothers reported that they had ANC visit for the indexed child. Three-fourths of the children (74.8%) were born in health institutions. Majority of the children (41.9%) were vaccinated in health centers. For more than half of mothers (54.3%) the travel time to the nearest health institution from their home was ≤ 30 minutes. More than three-fourths (77.5%) of children mothers’ knew vaccination schedule of their catchment area. Around one-in-five children mothers’ (18.5%) had reported that they ever returned without getting a vaccine. With regard to mothers’ knowledge about the age at which the child initiated and finished vaccination, 73.3% and 65.5% of them knew the age at which child should begin and finish vaccination respectively. More than one-third of mothers (37%) worried vaccines would cause the child to be sick. Majority of the mothers (85%) stated they would take their child for vaccination even if the child was sick. ().

Table 2. Access to a health facility, utilization and mothers’ perception about vaccination, East Gojam Districts, Northwest Ethiopia. (N = 830).

Children vaccination status

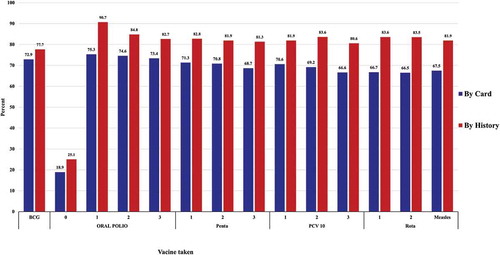

More than nine in ten mothers of the children in this study (91.8%) [95% CI: 89.9, 93.6] reported that the indexed child received vaccination and 77.3% [95% CI: 74.4, 80.2] of mothers showed the child vaccination card. Almost three-fourths of children (74.6%) [95% CI: 71.6, 77.6] had BCG scar. Nearly three-fourths of children were vaccinated for BCG (72.9% [95% CI: 69.8, 75.8], 77.7% [95% CI: 74.8, 80.4]), OPV-3 (73.4% [95% CI: 70.4, 76.3], 82.7% [95% CI: 80, 85.2]), Penta-3 (68.7% [95% CI: 65.5, 71.6], 81.3% [95% CI: 78.6, 84]), PCV10-3 (66.6% [95% CI: 78.6, 84], 80.6% [95% CI: 78.6, 84]), Rota-2 (66.5.5% [95% CI: 63.3, 69.5], 83.5% [95% CI: 81.1, 85.9]), and measles (67.5% [95% CI: 64.1, 70.6], 81.9% [95% CI: 77, 82.4]) by card and history respectively (). The drop-out rate between the first and third pentavalent vaccine coverage was 3.73%. While drop-out rate between BCG and measles was 7.44%.

Figure 1. Vaccination coverage of each vaccine by card Vs history among study children aged 12 – 23 months, East Gojam Districts, Northwest Ethiopia. (N = 830)

Regarding children over all vaccination status 58.4% (485), 17% (141) and 24.6% (204) of the children were fully vaccinated, partially vaccinated and not vaccinated respectively ().

Figure 2. Vaccination status of children aged 12 – 23 months by card, in East Gojam Districts, Northwest Ethiopia. (N = 830)

Mothers who did not take their children for the vaccinations at all and not completed vaccinations as per schedule had mentioned the following reasons: not important (42.2%), do not know the need to return for another vaccinations (29.3%) and schedule not convenient (2.3%) ().

Table 3. Mothers of children aged 12–23 months reasons for not or incomplete vaccination, East Gojam, Northwest Ethiopia.

Factors associated with children full vaccination status

The result of bivariate and multivariable analysis presented as follows; mothers who are urban residence, ever married, able to read and write, number of live birth 1–3, family size ≤ 4 & 5 – 7 compared to those with > 8 family, having ANC visit for index child, delivery at health institution, vaccination site at hospital, vaccination site at health center, travel time ≤ 30 minutes to the nearest vaccination, knowing vaccination schedule for the catchment area and taking child for vaccination if he/she is sick were In bivariate analysis.

Mothers who live in urban (AOR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.20, 3.66), ever married (AOR: 0.45, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.94), had ANC visit for index child (AOR: 3.09, 95% CI: 1.86, 5.14) and delivered in health institution (AOR: 2.10, 95% CI: 1.43, 3.08) were the maternal factors that were associated with children vaccination statuses. Vaccination site at health institutions {hospital (AOR: 2.97, 95% CI:1.36, 6.47), health center (AOR: 3.31, 95% CI: 1.39, 6.46), and health post (AOR: 5.60, 95% CI: 3.27, 9.59) when compared to scheduled outreach vaccination site}, children at ≤ 30 minutes travel time to the nearest vaccination site were less likely to be fully vaccinated when compared to child who had > 30 minutes travel time (AOR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.33, 0.65), knowledge of vaccination schedule of a catchment area (AOR: 1.82, 95% CI: 1.23, 2.68), taking child for vaccination even if the child is sick (AOR: 1.72, 95% CI:1.10, 2.68) were significantly associated predictors with child full vaccination status. However, mothers’ age, mothers’ educational status, fathers’ education status, number of live birth, total family size, age of indexed child, sex of index child, index child birth condition, index child living with, order of indexed child, have ever gone for child’s vaccination, waiting time for vaccination, knowledge of at what age should the child start vaccination, ever returning without getting vaccine, schedule ever canceled or postponed, and knowledge of vaccine preventable diseases were not the significantly associated factors with child full vaccination status in multivariable analysis ().

Table 4. Factors associated with vaccination status of children aged 12 – 23 months, in East Gojam Districts North-West Ethiopia. (N = 830).

Discussion

Vaccination coverage by card is used for discussion since it is believed that the record to be taken from vaccination cards are more valid and reliable than mothers’ recall and free of recall bias.Citation23 This study has revealed that in East Gojam, children aged 12–23 months who had full vaccination were nearly three in every five children (58.4%), which is higher than the studies done at Wonago district South Ethiopia (41.7%,Citation24 the 2016 national coverage (39%Citation7 and Kombolcha Woreda in Oromia (22.9%,Citation11 27.5% in Ambo woredaCitation20 and Mozambique at Gurùé and Milange districts 48%.Citation25 However, the vaccination coverage in the study area is lower than Malaysia, 86.4%.Citation26 This discrepancy might be due to access to vaccination variation across the specified study areas.

In this study, nearly one in every six children were partially vaccinated (17%) which is almost similar to a study done in Southern Ethiopia (20.3%).Citation10 However, it is lower than a study done at Jigjiga district, 38%.Citation20 This difference would be due to the presence of relatively better follow-up of mothers’ to visit vaccine site in this study area.

Regarding children who were not vaccinated, this study has shown a quarter of children (24.6%) were not vaccinated at all is congruent to a study done in Eastern Ethiopia that showed 25.4%.Citation19 However, it is higher than the Ethiopian national survey of children vaccination status (16%)Citation7 and Wonago district (17%.Citation24 This might be due to lack of awareness of mothers’ on the importance of vaccine as they reported that reasons for not or incomplete vaccination were because they consider vaccine is not important and may be a low home delivery rate which accounts 25.2% in this study.

The drop-out rate between the first and third pentavalent vaccine coverage was 3.73%. While drop-out rate between BCG and measles was 7.44%. This is lower when compared to a study done in Mecha district Northwest Ethiopia which showed Penta dropout rate (13.9%) and BCG to measles vaccine dropout rate (18.6%Citation12 and national dropout rate (20%).Citation7 The discrepancy might be due to the presence of actively working health extension works and voluntarily working farmers that would announce the community during the vaccine schedule on a regular base in this study areas.Citation28

This study indicated that urban residents had more child full vaccination coverage than the rural. Child of a mother who resides in urban has 2.04 times more likely to complete vaccination when compared to a rural child which is congruent to a study done in Jigjiga.Citation19 Having ANC visit for indexed child, institutional delivery for indexed child, health institutions vaccination site (hospital, health center & health post), knowledge of vaccination schedule of the catchment area, and taking a child for vaccination even if the child is sick had better vaccination coverage than their counterpart. On the other hand, ever-married mothers and shorter travel time (≤ 30 minutes) to the nearest vaccination site were negatively associated with child vaccination status.

Mothers with antenatal care visit had more likely to complete their child’s vaccination than those who did not have ANC visit. This is similar to a study in Zimbabwe;Citation28 and mothers who delivered in a health institution had more likely to complete child vaccination when compared to mothers who delivered at home which is congruent to other studies.Citation28,Citation29 This study also revealed that mothers’ knowledge of vaccination schedule of a catchment area has a positive association to have a child fully vaccinated. This is congruent to a study done in Kenya.Citation29 Taking a child for vaccination even if the child was sick was positively associated with child vaccination status. In other studies, it was mentioned as a reason given for incomplete child vaccination.Citation30,Citation31 This discrepancy might be due to the fact that mothers would prefer to visit health professionals when their child is sick; and health professionals would arrange for vaccination in addition to treatment of a child.

This study had indicated that vaccination site at health institutions compared to scheduled outreach vaccination site were highly associated with child full vaccination status. This would be because of regular availability of vaccines at health institutions than outreaches.

The odds of having child full vaccination among ever married mothers were 0.45 [AOR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.22 – 0.94] times among children of not married mothers. This is in contradict other studies that marital status was not a predictor.Citation12,Citation26 The reason could be in this study, ever married mothers who did not fully vaccinated their child accounts 40.8% and their occupation were housewives. Since housewives spent most of their time at home, they might not get information regarding vaccination.

The odds of having child full vaccination among mothers who were at a travel time of ≤ 30 minutes to the nearest vaccination site were 0.47 [AOR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.33 – 0.65] times lower than their counterpart. Another previous study also indicated that the distance to the vaccination site was a positive predictor of child full vaccination status.Citation32 The difference might be due to the top-rated mothers’ reason in this study for not at all or incomplete vaccination; considering vaccination as it is not important and don’t know the need to return for another vaccination.

Limitation of the study: Despite the fact that data collectors used different strategies to reduce recall bias, still mothers who lost their child card might forget the vaccine given for their child hence might fail to report exact.

Conclusions and recommendations

The overall status of children vaccination, 58.4% were fully vaccinated, 17% partially vaccinated and 24.6% not vaccinated. Nearly three-fourths of the children were vaccinated for BCG (72.9%) with about three-fourths BCG scar, OPV-3 (73.4%), Penta-3 (68.7%), PCV10-3 (66.6%), Rota-2 (66.5%), and measles (67.5%) by card. The drop-out rate between the first and third pentavalent vaccine coverage was 3.73%. While drop-out rate between BCG and measles was 7.44%. Top rated reasons for not vaccination were mothers’ considering the vaccinations as not important and did not know the need to return for another vaccination.

Urban residence, having ANC visit for index child, delivery in health institution, health institutions vaccination site, knowledge of vaccination schedule of a catchment area, and taking a child for vaccination even if the child was sick were found to be significantly and positively associated to the children’s vaccination status. While being married and shortest travel time to the nearest vaccination site were negatively associated predictors of children’s vaccination status.

Findings from this study showed that full vaccination coverage is lower than the WHO’s EPI coverage plan (95%). Hence, Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MOH) shall work with the regional health bureaus and lower administrative hierarchy to achieve the proposed coverage by: promoting ANC utilization and delivery at health institutions; and creating awareness about the importance of vaccination of children.

Health care workers at respective health institutions shall: give adequate information on child vaccination (including when to start, return and finish) for each ANC, postpartum mothers and mothers visiting vaccination site at every visit; and communicate the respective vaccination schedule to mothers through a different mechanism like a phone call for mothers.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board of Bahir Dar University before the beginning of data collection. Verbal consent was taken from each participant. Data are kept confidential and communicated without disclosing individual identity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate East Gojam administrations, the study participants, and data collectors for their cooperation and support.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nieburg PMclaren NM. Role(s) of Vaccines and Immunization Programs in Global Disease Control. A report of the CSIS global health policy center [Internet]. Washington, D.C; 2011. Available from: https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/111221_Nieburg_RolesofVaccine_WEB.pdf.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health (FDRE MOH). Immunization in Practice Training Manual.Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Health; 2015. p. 1-258.

- WHO, UNICEF and World Bank. State of the world`s vaccines and immunization [Internet]. 3rd ed. Hum. Vaccin. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.4161/hv.6.2.11326.

- WHO. 2016 Mid-term Review of the Global Vaccine Action Plan Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2016 [ cited 2018 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/en/.

- WHO and UNICEF. WHO | Immunization coverage.WHO [Internet]. 2017 [ cited 2018 Mar 25]; Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs378/en/.

- WHO | World Health Assembly endorsed resolution to strengthen immunization [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2017 [ cited 2018 Mar 25]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/newsroom/wha_endorse_resolution_strengthen_immunization/en/.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia], ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiop. Rockville, Maryland, USA CSA ICF [ Internet]. 2016; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf.

- Ethiopia National Expanded Program on Immunization, Comprehensive Multi - Year Plan 2016–2020. Federal ministry of health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry Of Health, Addis Ababa; 2015. p. 1-115.

- Central Statistical Agency and ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011 [Internet]. Heal. San Fr. 2012. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/ET_2011_EDHS.pdf%0A%0A.

- Animaw W, Taye WMerdekios B, et al. Expanded program of immunization coverage and associated factors among children age 12-23 months in Arba Minch town and Zuria District, Southern Ethiopia, 2013. BMC Public Health [ Internet]. 2014;14:464.Available from: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-464.

- Mohammed H, Atomsa A. Assessment of child immunization coverage and associated factors assessment of child immunization coverage and associated factors in oromia regional state, eastern ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2013;2:36-41 2:36-41 2: 36.

- Debie A, Taye B. 2014. Assessment of fully vaccination coverage and associated factors among children aged 12-23 months in mecha district, north west ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Science Journal Of Public Health. 2014;2:342-8 2:342-8 2: 342.

- The Millennium UNDESA. Development Goals Report. United Nations 2005:48. doi:10.1177/1757975909358250.

- EFMOH. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health: Health Sector Development Programme IV 2010/11-2014/15 2010; IV: 114. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jht077.

- Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health. Ethiopia National Expanded Programme on Immunization: Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2011-2015. Addis ababa, Ethiopia; 2010. p. 1-76.

- WHO. Immunization coverage cluster survey- Reference manual [Internet]. World Heal. Organ. Geneva, Switzerland; 2005. p. 115. Available from: www.who.int/immunization/.../Vaccination_coverage_cluster_survey_with_annexes.p.

- Tsega A, Daniel FSteinglass R. Monitoring coverage of fully immunized children. Vaccine. 2014;32:7047–9.

- Fatiregun AA, Okoro AO. 2012. Maternal determinants of complete child immunization among children aged 12-23 months in a southern district of nigeria. Vaccine. 30:730-6:.

- Mohamud AN, Feleke A, Worku W, Kifle MSharma HR. Immunization coverage of 12-23 months old children and associated factors in jigjiga district, somali national regional state, ethiopia. Bmc Public Health. 2014;14:865.

- Etana B, Deressa W. Factors associated with complete immunization coverage in children aged 12-23 months in ambo woreda, central ethiopia. Bmc Public Health. 2012;12:566.

- Adedire EB, Ajayi I, Fawole OI, Ajumobi O, Kasasa SWasswa P, et al. Immunisation coverage and its determinants among children aged 12-23 months in atakumosa-west district, osun state nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Bmc Public Health. 2016;16:905.

- World Health Organization Vaccination Coverage Cluster Surveys [ Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/Vaccination_coverage_cluster_survey_with_annexes.pdf.

- Miles M, Ryman TK, Dietz V, Zell ELuman ET. Validity of vaccination cards and parental recall to estimate vaccination coverage: a systematic review of the literature. Vaccine. 2013;31:1560-8.

- Tadesse H, Deribew A, Woldie M. Predictors of defaulting from completion of child immunization in south ethiopia, may 2008 - a case control study. Bmc Public Health. 2009;9:4-9:.

- Shemwell SA, Peratikos MB, González-Calvo L, Renom-Llonch M, Boon AMartinho S, et al. Determinants of full vaccination status in children aged 12-23 months in gurùé and milange districts, mozambique: results of a population-based cross-sectional survey. Int Health. 2017;9:234–42:.

- Lim KK, Chan YY, Noor Ani A, Rohani J, Siti Norfadhilah ZASanthi MR. Complete immunization coverage and its determinants among children in malaysia: findings from the national health and morbidity survey (nhms) 2016. Public Health. 2017;153:52–7.

- Bilal NK, Herbst CHZhao F, et al. Health Extension Workers in Ethiopia: Improved Access and Coverage for the Rural Poor. 2012. p. 433–444. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/304221468001788072/930107812_201408251045629/additional/634310PUB0Yes0061512B09780821387450.pdf.

- Mukungwa T. Factors Associated with full Immunization Coverage amongst children aged 12–23 months in Zimbabwe. African Popul. Stud. [ Internet]. 2015;29:1761–1774. Available from: https://ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=113757800&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Kiptoo E. Factors Influencing. Low immunization coverage among children between 12-23 months in east pokot, baringo country, kenya. Int J Vaccines Vaccin. 2015; 1:1–6.

- Siddiqi N, Khan ANisar N, et al. Original article assessment of epi (expanded program of immunization) vaccine coverage in a peri-urban area. J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:391–395.

- Abdulraheem I. S.Onajole A. T. JAAG. Reasons for incomplete vaccination and factors for missed opportunities among rural nigerian children. J Public Heal Epidemiol. 2011;3:194–203.

- Ntenda PAM, Chuang K-Y, Tiruneh FN, Chuang Y-C. Analysis of the effects of individual and community level factors on childhood immunization in Malawi. Vaccine. 2017;35(15):1907–1917. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.036.