ABSTRACT

Background: Vaccine hesitancy (VH) is a growing problem. The first step in addressing VH is to have an understanding of who are the hesitant individuals and what are their specific concerns. The aim of this survey was to assess mothers’ level of vaccine hesitancy and vaccination knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs.

Methods: Mothers of newly-born infants in four maternity wards in Quebec (Canada) completed a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire included items to assess VH and intention to vaccinate. VH scores were calculated using the Parents Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) survey. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine variables associated with intention to vaccinate (OR; 95% CI).

Results: Overall, 2645 questionnaires were included in this analysis and 77.5% of respondents certainly intended to vaccinate their infant at 2 months of age. Based on the PACV 100-point scale, 56.4% of mothers had a 0 to ˂30 score (low level of VH); 28.6% had a 30 to ˂50 and 15.0% had a score of 50 and higher (high level of VH).The main determinants of mothers’ intention to vaccinate were the perceived importance of vaccinating infants at 2 months of age (OR = 9.2; 5.9–14.5) and a low score of VH (OR = 7.4; 5.3–10.3).

Discussion: Although the majority of mothers held positive attitudes toward vaccination, a large proportion were moderately or highly vaccine hesitant. Mothers’ level of VH was strongly associated with their intention to vaccinate their infants, showing the potential detrimental impact of VH on vaccine uptake rates and the importance of addressing this phenomenon.

Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy (VH) includes individuals with various degrees of concerns about vaccination who may refuse some vaccines, but agree to others, delay vaccination or accept vaccination although feeling ambivalent about doing so. The WHO SAGE Working Group on VH defines VH as a lower than expected vaccine acceptance, given the information provided and services available. The phenomenon is complex and context-specific, varying across time and place and with different vaccines. Factors such as complacency, convenience, as well as confidence in vaccines may all contribute to the delay in vaccination or refusal of one, some or almost all vaccinesCitation1 Because high uptake rates are needed to maintain the success of vaccination programs, the impact of VH on parental acceptance of routine childhood vaccines has been recognized worldwide as a growing problemCitation2

The results of the 2014 Quebec population-based childhood vaccine coverage survey showed that 80% of one-year-old children and 71% of two-year-old children had received all recommended vaccinesCitation3 Although these vaccine uptake rates are high, they do not meet the objective, which is to vaccinate 95% of children as recommended by the World Health OrganizationCitation4 Given that vaccines are delivered through publicly-funded programs, limited access to vaccination services is not the main determinant of suboptimal uptake rates. Studies in Quebec have highlighted that parental VH is present and has an impact on vaccine uptake ratesCitation3,Citation5,Citation6

The aim of this cross-sectional study is to evaluate VH and vaccination knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs (KAB) of a large and diverse sample of mothers of newborns. Data were collected in maternity wards in Quebec.

Results

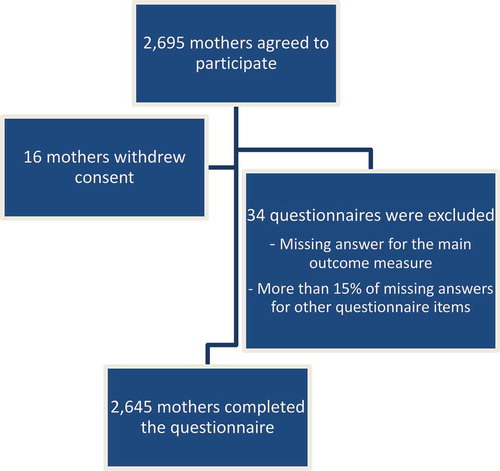

Overall, 2645 mothers of newborns completed the questionnaire and were included in this analysis (participation rate of 64%, ).

Mothers’ socio-demographic characteristics

The majority of mothers were aged 20–29 years (38.2%) or 30–39 years (56.6%) at childbirth and most mothers were born in Canada (74.3%). The majority of children were the mothers’ first (47.0%) or second (36.3%) child. More than half of the mothers (55.9%) had completed a university degree and the majority were living with a partner (53.6%) or were legally married (37.3%).

Mothers’ intention to vaccinate and knowledge about vaccination and vaccine-preventable diseases

The majority of mothers had a strong intention to vaccinate their infant at 2 months of age (77.5% of respondents certainly intended). Most mothers (84.3%) knew where to get their infant vaccinated. Although 43.2% of mothers felt they were sufficiently informed about their child’s vaccination, 70% had a score indicating a low level of knowledge for the 8 vaccine-preventable childhood diseases (). More than half of mothers were well (24.9%) or somewhat well (32.1%) informed about the importance of adhering to the recommended vaccine schedule. More than half of mothers (54.6%) also intended to perform a detailed research before deciding about their infant vaccination (21.7% totally agreed and 32.9% somewhat agreed). Approximately half of the mothers (48.9%) who certainly intended to have their infant vaccinated were planning to perform a detailed research before making a final decision compared to 74.1% of mothers who were unsure or did not intend to vaccinate their infant (p < 0.0001).

Table 1. Mothers’ knowledge about vaccination.

Sources of information about vaccination

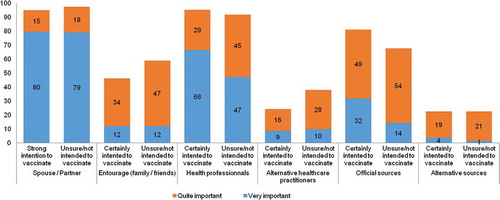

Parental opinions on the influence that other persons and sources of information have on their vaccination decisions are shown in . There were statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001) in responses from mothers who strongly intend to vaccinate their child or not, for the perceived importance of all sources, with the exception of the spouse/partner’s opinion. Mothers who did not intend to vaccinate or were unsure were more likely to consider as important alternative health care practitioners’ opinions and less likely to consider official sources as important, compared to mothers who intended to vaccinate their infant. Overall, 95.4% of mothers considered that the opinion of their spouse or partner was very (79.5%) or somewhat (15.9%) important. Other sources of information considered as important were health care professionals (62% = very important, 32.4% = somewhat important) and official sources such as written information produced by the Quebec Ministry of Health (62% = very important, 32.4% = somewhat important). Internet and social media were not perceived as important sources by most (3.2% = very important, 19.4% = somewhat important). The same was observed for alternative health care practitioners, such as naturopaths or homeopaths (8.8% = very important, 18.5% = somewhat important) and members of the social network (12% = very important, 37% = somewhat important).

Parental attitudes about vaccination

Overall, 71.2% of respondents believed that their infant was unlikely to become ill from one of the 8 vaccine-preventable childhood diseases. A higher proportion of mothers who believed that their child was at high risk for any of the 8 vaccine-preventable diseases had a strong intention to have their child vaccinated, as compared with mothers who were not perceiving their infants to be at high risk (90.8% vs. 9.2%; p < 0.0001). Perceived risk of vaccination was also lower among mothers who intended to vaccinate (89.9% considered the risk to be low or absent vs.75.0% among mothers who were not sure or did not intend to vaccinate). The vast majority of respondents recognized the efficacy of vaccines (96.2%). The importance of initiating the vaccination series at the age of 2 months was also recognized by the majority of respondents (99.6% of mothers who had a strong intention to vaccinate considered it very or somewhat important vs. 86.4% among mothers who were who were not sure or did not intend to vaccinate). Finally, 87.3% of mothers indicated that they would feel remorse if their infant fell ill from a disease against which he/she was not vaccinated (92.7% of mothers with a strong intention to vaccinate would feel strong remorse vs. 68.5% among mothers who were not sure or did not intend to vaccinate).

Vaccine hesitancy

Mothers’ answers to the 13 items (PACV) used to calculate the VH score are presented in . Overall, mothers’ answers were generally in favor of vaccines. However, 61.0% were concerned that their child might have a serious adverse event following immunization and 52.5%were concerned that childhood vaccines might not be safe.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, PACV items association with intention to vaccinate the child at 2 months of age.

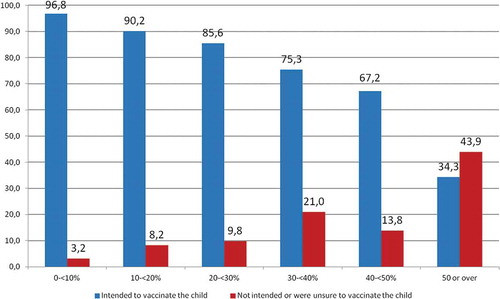

The average VH score for all mothers was 27/100, with 56.4% of mothers having a score ranging from 0 to ˂30/100 – indicating a low level of VH; 28.6% of mothers having a score from 30/100 to ˂50/100 and 15.0% of mothers having a score of 50/100 and higher – indicating a high level of VH. A statistically significant linear trend between mothers’ VH scores and their intention to vaccinate their child was found (p < 0.0001) ().

Determinants of mothers’ intention to vaccinate

The final multivariate model indicated that the most significant determinant of vaccination intention was the perceived importance of vaccinating the child at 2 months of age, a VH score below 30, anticipated remorse of non-vaccination, and feeling knowledgeable about vaccines ().

Table 3. Regression analysis on the variables associated with mothers’ intention to vaccinate their infant at 2 months old*.

Discussion

In this study, we have gathered essential information on knowledge, attitudes and intentions about vaccination in a large cohort of mothers of newborns, recruited in 4 maternity wards representing more than 20% of all annual births occurring in the province of Quebec (Canada). Our findings show that most mothers held positive attitudes toward vaccination, with more than 90% considering the vaccines to be effective and the vaccine-preventable diseases, to be severe. However, our results showed that an important proportion of the mothers were concerned about vaccine safety. Although only 15% of mothers had a score of 50 or higher on the PACV scale, indicating a high level of VH, one third had an intermediate level of VH which indicates that VH is an important issue in Quebec. These findings are comparable to other studies’ results that used the PACV instrumentCitation7,Citation8 For example, results of a study using the PACV in Malaysia showed that 12% of parents were vaccine-hesitantCitation9 Another study conducted in the United States showed that 26% of parents were highly hesitant about the influenza vaccination for their childrenCitation10 In Italy, findings of another cross-sectional survey of parents of children aged 2 to 6 years using the PACV showed a higher level of vaccine hesitancy among parents, with 35% of parents having a score of 50 or higher on the vaccine-hesitancy scaleCitation11 To date, the PACV is the only survey instrument that is reliable and valid to directly measure the level of vaccine hesitancy among parents of infants and predict their vaccination decision at 2 monthsCitation7

Our findings also showed that 22.5% of mothers were not certain about their intention to vaccinate their child. In multivariate analysis, we have identified several determinants of mothers’ intention to vaccinate and the two most important were parents’ perception of the importance of vaccinating their infant at 2-month of age and a low score of VH. The relationship between VH scores and future vaccination behaviours has also been demonstrated in a prospective cohort study of parents of two month-old children in Seattle, where a parental PACV score of at least 50 was associated with a significant increase in under-immunization at 19 months of ageCitation7 The belief that recommended schedule contains “too many vaccines, too soon” and that “spreading out” vaccines over a longer period of time is safer has been frequently associated with parental VH and intention to vaccinate in other studiesCitation12-Citation15

Our findings also indicate that the majority of mothers had a low level of knowledge on vaccination, even those who intended to have their infant vaccinated as recommended. The communication of information is one of the primary tools at the disposal of public health professionals. Being informed about which vaccines are needed, for whom and when is the basis of the vaccination decision-making process. However, a summary of the findings from 15 published literature reviews or meta-analyses that examined the effectiveness of interventions to reduce VH and/or to enhance vaccine acceptance has shown that simply providing information, education and communicating evidence of vaccine safety and efficacy to those who are vaccine-hesitant has done little to stem the growth of hesitancy-related beliefs and fearsCitation16 Knowledge is important but not sufficient to change people’s perception of vaccine risksCitation17 Studies have shown that messaging that too strongly educates and advocates vaccination can be counterproductive for those who are already hesitantCitation18 Providing too much information can also generate hesitancyCitation19 Individuals, when faced with information that contradicts their values, can feel threatened, react defensively and this creates resistance, resulting in a strengthening of their initial beliefs and reducing the likelihood of engaging in the desired behavior (i.e. vaccination acceptance)Citation20 Therefore, it is critical that we identify approaches to communication that not only enhance vaccine acceptance, but also minimize unintended negative impacts of well-intended interventions. Addressing VH with communication is complex and requires tailored strategies that are tested, evidence-informed and context-sensitive.

As shown by the results of our multivariate analysis, the determinants of parents’ intention related more to how parents felt about their knowledge (i.e., feeling of being sufficiently informed about vaccination, knowledge of the importance of vaccinating at 2 months) than about what they objectively knew (knowledge of the vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccines administered at 2, 4 and 6 months of life). These interesting findings could reflect much more a sense of parental self-efficacy than of knowledge. These results also highlight the relevance of our promotion intervention based on motivational interviewing technique that support an individual’s motivation for and movement toward a specific goal by eliciting and exploring his or her own arguments for change, instead of just providing more facts about vaccines or vaccine-preventable diseases.

Finally, the majority of mothers we interviewed have also searched for information regarding childhood vaccines, mainly on the Internet. The fact that one quarter of mothers we interviewed considered Internet as their most reliable and trustworthy source of information about vaccines is worrisome. The quality of vaccination-related information on websites, including social media platforms, is highly variable with substantial negative and inaccurate informationCitation21,Citation22 Other studies have shown that undertaking a detailed research on vaccination before deciding was strongly associated with intending not to vaccinate the childCitation15,Citation23,Citation24 Given that individuals typically tailor their searches to pre-existing concerns, and that personalized website algorithms selectively guess what information a user would like to see based on past click behaviour and search history, the Internet broadly contributes to VHCitation25,Citation26

Our study’s findings should be interpreted in the light of some limitations. First, selection bias and non-response bias cannot be ruled out. Younger mothers (less than 18 years of age), mothers who did not gave birth in the selected hospitals and mothers who did not speak English or French were excluded. Although we obtained a participation rate of 64%, it is still possible that non-participants have different views compared to participants. However, our sample size was large with very few missing data. No sociodemographic information on non-respondents was available. Our sample included more mothers aged older than 29 years when compared to data on Canadian families with childreCitation27 and more mothers with a university degree when compared to data on the general Canadian population of adultsCitation28 Although we used the PACV, which is a validated measure of VH, our main outcome measure (“Do you plan to vaccinate your child at 2 months of age”) is not theoretically derived. However, this item was pre-tested and showed good validity and reliability in a previous study of our study teamCitation29-Citation31 Finally, as in most surveys, there is the potential for social desirability bias, meaning participants respond what they believe the researchers would like to hear.

In conclusion, despite the fact that most mothers held positive attitudes toward vaccination, a considerable proportion of mothers were vaccine hesitant. The quantified mothers’ level of VH was strongly associated with their intention to vaccinate their infants, showing the potential detrimental impact of VH on vaccine uptake rates and the importance of addressing this phenomenon. As shown by this study’s results and our previous workCitation8 an educational intervention using motivational interviewing techniques could enhance mothers’ vaccination intention and should be considered in public health promotion policies.

Methods

Participants were recruited in 4 maternity wards in Quebec (Sherbrooke (CHUS), Quebec City (CHUQ), Montreal (Sainte-Justine and McGill University Health Centre)) as part of another studCitation32 to test the impact of an intervention to promote vaccination at birth. The maternity wards were selected because they were among the largest in the province (more than 25% of birth) and because they were deserving patients with different characteristics in terms of language (French vs. English), place of residence (urban vs. rural) and ethnicity (born in Canada or not). Mothers who gave birth in the participating maternity wards during the period of March 2014 to February 2015 were approached to participate. Mothers were screened during their postpartum stay in the maternity ward, over regular business hours (8AM to 5PM), in chronological order of delivery. In practical terms, this meant that mothers who had delivered first and who had not been approached by the research team were screened first. This approach was adopted in order to optimize recruitment given the short duration of postpartum maternity ward stays (mean duration = 48 hours). Recruitment was limited to mothers aged 18 years or over and speaking English or French in each participating maternity ward. Newborns or mothers necessitating acute care were excluded from the study. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Board of each participating facility. A written informed consent was obtained from all mothers who consented to participate. All eligible mothers completed a self-administered questionnaire (in French or in English). As this survey was part of a larger study, the sample size was estimated at 2,900 mothers to be able to assess the impact of the intervention on infants’ vaccine uptake rates at 2 months of age (these findings will be reported separately).

Data collection

In addition to standard demographics questions, the questionnaire contained items to assess: 1) mothers’ knowledge about vaccine-preventable diseases and vaccines administered at 2, 4 and 6 months of life and the importance of different sources of information about vaccination as well as 2) mothers’ attitudes about vaccination. Questions to measure mothers’ attitudes about vaccines’ safety and efficacy were based upon the Health Belief ModelCitation33 Other attitudinal questions measured VH and were based upon the Parents Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines (PACV) surveyCitation8 The PACV is a 15-item survey identifying vaccine-hesitant parents, developed and validated in the United States to predict 2 months vaccination based on the attitudes of parents of infants. Answers to PACV are scored from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the highest VH score. From the original PACV, two items were removed since they were not applicable to a child birth (Have you ever delayed having your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy?; Have you ever decided not to have your child get a shot for reasons other than illness or allergy?). Some other items were reworded to fit the neonatal context. Finally, mothers’ intention to vaccinate their newborn, the main outcome measure in this study, was assessed by one item (Do you plan to vaccinate your child at 2 months of age?).

The majority of the questions used a 4-point Likert scale. The reliability and content validity of the questionnaire were assessed in a pilot studyCitation29-Citation31

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4. Descriptive analyses were computed for all variables included in the questionnaire administered prior to the education intervention for all mothers. Questionnaires with missing answers for the main outcome measure or with more than 15% of missing answers were excluded from the analyses. The main outcome measure (parent’s intention to vaccinate their newborn) was dichotomized (“Certainly” answers, defined as strong intention, vs. “Probably”, “Probably not” and “Certainly not” answers, defined as unsure/no intention). A global score (0–100) was calculated for the 8 items on mothers’ risk perception of vaccine-preventable diseases by assigning a value of 0 for responses “Not at all”, of 1 for “Somewhat”, of 2 for “Quite Well” and of 3 for “Very Well”.

Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to explore differences in respondent’s answers to questionnaire items, when appropriate. Linear trends were analyzed using the Cochran-Armitage tests (two-sided). Following Opel et al.’s approachCitation8 responses to questions measuring VH were scored by assigning a numeric score of 2 for items answered with a hesitant response, of 1 for “ I don’t know or not sure” response, and of 0 for non hesitant response. Item scores were summed in an unweighted fashion to obtain a total raw score that was scaled to a range going from 0 to 100 using simple linear transformation and accounting for missing data (with 100 indicating the highest level of VH). A multivariable logistic regression model was used to determine variables independently associated with mothers’ intention to vaccinate. Variables associated in the univariable analysis at p ≤ 0.20 were entered into the multivariable regression model using stepwise selection (forward and backward). Each rejected variable was re-evaluated in the final model to assess model fit. A probability level of p < 0.05 based on two-sided tests was considered statistically significant. Collinearity was checked, and model fit was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Hosmer and Lemeshow test. Odds ratios (OR) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

Abbreviations

| CI | = | confidence intervals |

| KAB | = | Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs |

| OR | = | Odds ratios |

| PACV | = | Parents Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines |

| VH | = | Vaccine Hesitancy |

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the research staff involved in this study: Marie-Laure Specq (Sherbrooke); Isabelle Chabot, Marie-Christine Samson, Nathalie Breton (Quebec City); Lena Coic, Adela Barbaros (CHU Sainte Justine, Montreal); Deirdre McCormack, Allison Couture, Alice Weir and Giuliana Alfonso (McGill University Health Centre, Montreal).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ève Dubé

Dr Ève Dubé participated in study design conception and data interpretation. She wrote, reviewed/edited, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Anne Farrands

Anne Farrands participated in the training of the research assistants and the recruitment and data collection at the Sherbrooke maternity ward, reviewed/edited, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Thomas Lemaitre

Thomas Lemaître participated in the recruitment and data collection at the Sherbrooke maternity ward. He also participated in the study design conception and data interpretation, and reviewed/edited and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Nicole Boulianne

Nicole Boulianne, Dr Chantal Sauvageau, Dr Philippe De Wals and Dr Geneviève Petit participated in study design conception, and reviewed/edited, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

François D. Boucher

Dr François D. Boucher, Dr Bruce Tapiero and Dr Caroline Quach were responsible of the recruitment and data collection at the Quebec and Montreal maternity wards. They also participated in study design conception, reviewed/edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Manale Ouakki

Manale Ouakki performed data analysis and participated in data interpretation, and reviewed/edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Virginie Gosselin

Virginie Gosselin participated in data interpretation, and reviewed/edited the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dominique Gagnon

Dominique Gagnon participated in data interpretation, and wrote, reviewed/edited, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Marie-Claude Jacques

Marie-Claude Jacques participated in the training of the research assistants. She also participated in the study design conception, and reviewed/edited and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Arnaud Gagneur

Dr Arnaud Gagneur was the principal investigator of the RCT and responsible of the recruitment and data collection at the Sherbrooke maternity ward. He also participated in the study design conception, data interpretation, and wrote, reviewed/edited, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- MacDonald NE. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- World Health Organization. Meeting of the strategic advisory group of experts on immunization, April 2013 – conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2013;88(20):201–216.

- Boulianne N, Audet D, Ouakki M. Enquête sur la couverture vaccinale des enfants de 1 an et 2 ans au Québec en 2014. Québec: Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Canada; 2015.

- Duclos P, Okwo-Bele JM, Gacic-Dobo M, Cherian T. Global immunization: status, progress, challenges and future. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S2. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-9-S1-S2.

- Guay M. Vaccine hesitation among Quebec parents of children aged from 2 months to 5 years. Poster presentation at: 11th Canadian Immunization Conference; 2014 Dec 2–4; Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

- Dube E, Vivion M, Sauvageau C, Gagneur A, Gagnon R, Guay M. “Nature Does Things Well, Why Should We Interfere?”: vaccine hesitancy among mothers. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(3):411–425. doi:10.1177/1049732315573207.

- Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Zhou C, Catz S, Myaing M, Mangione-Smith R. The relationship between parent attitudes about childhood vaccines survey scores and future child immunization status: a validation study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1065–1071. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2483.

- Opel DJ, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Zhao C, Catz S, Martin D. Validity and reliability of a survey to identify vaccine-hesitant parents. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6598–6605. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.115.

- Mohd Azizi FS, Kew Y, Moy FM. Vaccine hesitancy among parents in a multi-ethnic country, Malaysia. Vaccine. 2017;35(22):2955–2961. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.010.

- Strelitz B, Gritton J, Klein EJ, Bradford MC, Follmer K, Zerr DM, Englund JA, Opel DJ. Parental vaccine hesitancy and acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccine in the pediatric emergency department. Vaccine. 2015;33(15):1802–1807. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.034.

- Napolitano F, D’Alessandro A, Angelillo IF. Investigating Italian parents’ vaccine hesitancy: A cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;1–8. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1463943.

- Dempsey AF, Schaffer S, Singer D, Butchart A, Davis M, Freed GL. Alternative vaccination schedule preferences among parents of young children. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):848–856. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0400.

- Gust DA, Darling N, Kennedy A, Schwartz B. Parents with doubts about vaccines: which vaccines and reasons why. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):718–725. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-0538.

- Freed GL, Clark SJ, Butchart AT, Singer DC, Davis MM. Parental vaccine safety concerns in 2009. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):654–659. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1962.

- Wheeler M, Buttenheim AM. Parental vaccine concerns, information source, and choice of alternative immunization schedules. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1782–1789. doi:10.4161/hv.25959.

- Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald NE. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–4203. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041.

- Corace K, Garber G. When knowledge is not enough: changing behavior to change vaccination results. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(9):2623–2624. doi:10.4161/21645515.2014.970076.

- Nyhan B, Reifler J. Does correcting myths about the flu vaccine work? An experimental evaluation of the effects of corrective information. Vaccine. 2015;33(3):459–464. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.017.

- Scherer LD, Shaffer V, Patel N, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Can the vaccine adverse event reporting system be used to increase vaccine acceptance and trust? Vaccine. 2016;34(21):2424–2429. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.087.

- Kahan DM. Social science. A risky science communication environment for vaccines. Science. 2013;342(6154):53–54. doi:10.1126/science.1245724.

- Witteman HO, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. The defining characteristics of Web 2.0 and their potential influence in the online vaccination debate. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3734–3740. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.039.

- Guidry J, Carlyle K, Messner M, Jin Y. On pins and needles: how vaccines are portrayed on Pinterest. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5051–5056. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.064.

- Brunson EK. The impact of social networks on parents’ vaccination decisions. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1397–404. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2452.

- Dube E, Bettinger JA, Halperin B, Bradet R, Lavoie F, Sauvageau C, Gilca V, Boulianne N. Determinants of parents’ decision to vaccinate their children against rotavirus: results of a longitudinal study. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(6):1069–1080. doi:10.1093/her/cys088.

- Betsch C, Renkewitz F, Betsch T, Ulshöfer C. The influence of vaccine-critical websites on perceiving vaccination risks. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(3):446–455. doi:10.1177/1359105309353647.

- Betsch C, Renkewitz F, Haase N. Effect of narrative reports about vaccine adverse events and bias-awareness disclaimers on vaccine decisions: a simulation of an online patient social network. Med Decis Making. 2013;33(1):14–25. doi:10.1177/0272989X12452342.

- Statistics Canada. National Household Survey. Statistics Canada; 2011 [accessed 2017 Apr 11]. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm.

- Statistics Canada. Education Indicators in Canada: an International Perspective. Statistics Canada; 2016 [accessed 2017 Apr 11]. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm.

- Gagneur A, Lemaître T, Gosselin V, Farrands A, Carrier N, Petit G, Valiquette L, De Wals P Promoting vaccination at birth using motivational interviewing techniques improves vaccine intention: the PromoVac strategy. BMC Public Health. Submitted for publication.

- Gagneur A, Petit G, Valiquette L, De Wals P An innovative promotion of vaccination in maternity ward can improve childhood vaccination coverage. Report of the Promovac study in the Eastern Townships. [in French] Library and National Archives of Canada; 2013. ISBN: 978-2-9813830-0-6 (print version), 978-2-9813830-1-3 (pdf version).

- Gagneur A, Lemaître T, Gosselin V, Farrands A, Carrier N, Petit G, Valiquette L, De Wals P. A postpartum vaccination promotion intervention using motivational interviewing coverage: promoVac Study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):811. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5724-y.

- Gagneur A, Dubé E, Farrands A, Lemaître T, Boulianne N, Sauvageau C, Boucher FD, Tapiero B, Ouakki M, Gosselin V, et al. Promoting vaccination at birth with motivational interviewing session improves vaccination intention and reduces vaccination hesitancy. Paper presented at: European Society for Paediatric Infectious Disease; 2016 May 15; Brighton (United Kingdom).

- Smith PJ, Humiston SG, Marcuse EK, Zhao Z, Dorell CG, Howes C, Hibbs B. Parental delay or refusal of vaccine doses, childhood vaccination coverage at 24 months of age, and the Health Belief Model. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 2):135–146. doi:10.1177/00333549111260S215.