ABSTRACT

The human papilloma virus (HPV) is known to be a major causative agent of cervical cancers and warts, limited study has been conducted on its associated factors among health care students and professionals in Malaysia. The present study was carried to explore the knowledge, understanding, attitude, perception and views about HPV infection and vaccination. A total of 576 respondents were recruited to complete a self-administered questionnaire through convenience sampling across Malaysia. 80.% and of the females respondents exhibited a positive attitude towards knowledge and understanding and 60% exhibited a positive towards attitude, perception and views. Almost 65% of the population were in agreement that HPV can be transmitted sexually, and 56.7% felt strongly that sexually active persons should essentially be vaccinated. The corresponding values were somewhat lower among the male respondents. Regression analysis suggested that knowledge and understanding were strong associated with gender, age, and occupation. Attitude, perception and views were also evidently associated with gender and age. The Ministry of Health should take steps to improve awareness among the citizens. Efforts should be made to educate people on the risk of HPV as a sexually transmitted diseases associated with HPV, and on the availability of discounted and safe HPV vaccines in government hospitals to increase the uptake rate of HPV vaccines among the Malaysian population.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is considered as one of beetling sexually transmitted infections in United States of America (U.S.A.). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), USA imprecise that around 79 million Americans, most in their late teens and early 20s, are infected with HPV virus. Overall, HPV is credited to be a common causative agent of cervical cancer.Citation1 Cervical cancer continues to be one of the leading female genital cancers worldwide. Studies surmised that about 80% and 87% of cervical cancer cases occur in urban countries and under developed regions, respectively.Citation2

It has also been reported that cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women, and the seventh overall, with an estimated 528,000 new cases in 2012, and 266,000 deaths from cervical cancer worldwide in 2012, accounting for 7.5% of all female cancer deaths approximately. The mortality varies by a factor of 18 across the world, with rates ranging from less than 2 per 100,000 in Western Asia, Western Europe and Australia/New Zealand to more than 20 per 100,000 in Melanesia (20.6), Middle Africa (22.2) and Eastern (27.6) Africa.Citation3,Citation4 The Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO) and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) published in a report in 2017 in which it was stated that every year an average 2145 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and 621 die from the disease. Cervical cancer is ranked as second most frequent cancer among women in Malaysia particularly in the age group between 15 and 44 years. It is estimated that approximately. 1% of women harbour cervical HPV infection at a given time, and 88.7% of invasive cervical cancers are attributed to HPVs.Citation5

Gardasil, Gardasil 9, and Cervarix are the three FDA approved vaccines for the prevention of diseases caused by HPV infection. Gardasil is quadrivalent vaccine effective against HPV type 6, and 11 which cause 90% of all genital warts.Citation6 It also effective against HPV type 16 and 18, two high-risk HPVs responsible for 70% of cervical cancersCitation7,Citation8 Gardasil 9 is a 9-valent vaccine, effective against cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, and genital warts caused by HPV types 6 and 11Citation9 Cervarix is bivalent vaccine effective against cervical cancer caused by HPV type 16, and 18.Citation10 Expert surmised that cervical cancer is the third most common cancer among Malaysian womenCitation11 Government agencies have raised awareness among women over the years which has reduced the incidence of cervical cancerCitation12 However, despite improved appreciation, there are many people who refuse to get themselves examined as they feel shy to do be examined. International Agency for Research on Cancer statistics suggest that the mortality rate of women of the Asian Pacific region associated with cervical cancer is 4 minutes.Citation13 The Malaysia government has also implemented the National HPV immunisation programme since 2010, supplying HPV vaccine free to targeted 13 year olds.Citation14

The conjecture among health professionals is that awareness about HPV vaccination in the Malaysian rural population is mediocre. It is logically understood the awareness among the masses on HPV can restraint the illness to a larger extent. However, it is consumed that the cost of the HPV vaccine is a serious palisade in the success of the vaccination programme in Malaysia.Citation15 It is estimated that 59 million women (50.1%) receive at least one dose of HPV globally, and 47 million (39.7%) complete the three-dose seriesCitation16 Studies have established that there are many barriers to complete the HPV vaccination Some of the barriers are lack of recommendation by primary care providers, cost, and insurance coverage, necessity of multiple visits to primary care providers, and parental concerns regarding initiation of HPV vaccinationCitation17

It has been suggested that Malaysian health care professionals have limited understanding about HPV vaccination. It is also assumed that awareness programmme genuinely improve the perception about the importance of HPV vaccination. This present study conducted to determine the level of knowledge, understanding, attitude, perception, views and health beliefs about HPV infection and vaccination among Malaysian health care students and professionals.

Results

Reliability test

The internal consistency of the study was tested using Cronbach’s Alpha, The test was computed for each sections of the questionnaire. The reliability measure was observed in the range of 0.70 to 0.80 for respective sections of the questionnaires for the variables of knowledge, understanding, attitude, perception and views about HPV. On the basis of the pilot test the questionnaire was modified to meet the compatibility of local settings and to suit the participants.Citation18

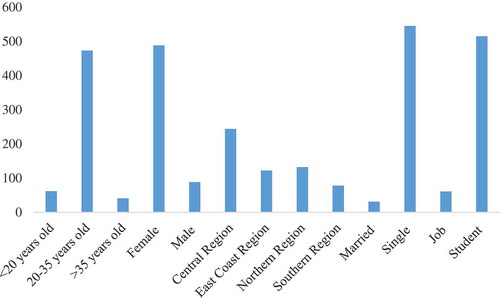

A total of 700 participants were approached, of which 576 responded to the survey (success rate of 82.2%). According to the report published by IARC, that cervical cancer is most common among the age group of 15–44, and hence the age group of 17–45 was targeted. This targeted population was further denominated into three age group, less than 20 years, 20–35 years and more than 35 years. Among the respondents Malaysian students of age less than 20 years constituted 10.7% of the respondents, and 82.1% of the respondents were between age of 20 – 35 years of age. The latter group mostly included health care students of higher institutes and professionals. 7.1% of the respondents were middle aged and were mostly married. Majority of the respondents were females (84.7%). Responses was received from the Central Region (Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya), Southern Region (Melaka, Johor), East Coast region (Kelantan, Terengganu, Pahang), and Northern Region (Perlis, Kedah, Penang, Perak). The respondent were selected so as to present a comprehensive study of knowledge, understanding, attitude, perception and views of HPV infection and vaccination among the health care students and professionals across Malaysia. Details of the respondent’s demographic characteristics are given in and .

Table 1. Demographic data and respondents intention for vaccination.

Knowledge and understanding about HPV

provides details about the knowledge and understanding of the respondents about HPV infection and vaccination. The knowledge and understanding were scored on a scale of 0 to 8 points. The mean score was 4.9 and a median score was 6. Scores of 6 and above were considered indicative of good knowledge and understanding. Scores below 6 were tabulated as poor scores. 60.9% of the respondents exhibited good knowledge and understanding about HPV infection and vaccination. The female respondents exhibited much better understanding about HPV and its perils than did the male respondents (OR = 0.031, p < 0.05). Age appeared to be a quite significant predictor of the attitude of Malaysians towards HPV. Participants in the age group of 20–35 years (OR = 3.21, p < 0.05), and those age less than 20 years (OR = 3.05, p < 0.05) had a better understanding of HPV than those who were more than 35 years old. Students (largely from health care institutes) proved to be more knowledgeable than those respondents in jobs (OR = 2.58, p < 0.05). The result from the four regions of Malaysian peninsular region predicted similar outcome with a slight better discernment in the central region because of its urban population ((OR = 1.68, p < 0.5). The association of all the demographic variables are listed in . The questions used and the analysing of response with respect to knowledge and understanding are provided in and .

Table 2. Association of demographics characteristics of Malaysians towards HPV vaccination.

Table 3. Association of demographics characteristics of Malaysians towards HPV vaccination.

Table 4. Participants attitude, perception and views towards HPV infection and vaccination.

Table 5. Knowledge and understanding of Malaysian towards HPV infection and vaccination.

Table 6. Questions for analysing knowledge and understanding of Malaysian health care students and professionals.

Attitude, perception and views about HPV infection and vaccination

The attitude, perception and views regarding HPV infection and vaccination were analysed by using the responses to eight questions measured on a 4 point Likert scale. Attitude, perception and views were measured on a scale of 8 to 32 scale. The mean value was 21.7 and a median score of 22. A score of 22 and above was considered as positive for attitude, perception and views and a score of less than 22 was tabulated as negative attitude, perception and views .77.7 of the respondents exhibited a positive attitude, perception and views about HPV infection and vaccination. The attitude, perception and views were better among female respondents compared with males respondents (OR = 0.91, p < 0.05). A positive attitude was a characteristic feature of population in the age group of 20–35 years (OR = 0.96, p < 0.05). An urban population and the central region appeared to be a significant predictors of positive attitude, perception and views regarding HPV compared with rural areas of Peninsular Malaysia (OR = 0.94, p < 0.05). Details of the association between the demographic characteristics and attitude, perception and views about HPV infection and vaccination are represented in .

The study revealed a strong misconception about vaccination against HPV. Majority of the respondents believed (42.4%, strongly agree; 36.4%, agree) that vaccination is not necessary to HPV prevention. A large number of young respondents said that their parents will object to HPV vaccination (64.3%, strongly agree; 23.9%, agree). Only a small proportion of the respondents said that they would agree to take vaccination even though if it was free (7.6 strongly agree; 7.6%, agree). Details of the response about HPV infection and vaccination are given in .

Discussion

The present study was carried out to assess knowledge, understanding, attitude, perception and views about HPV infection and vaccination among Malaysian health care students and professionals. Generally, it is assumed that good knowledge and understanding of a disease will be reflected in good practices regarding the use of drugs and vaccines for the disease, but the results of the present study were surprising, even though respondents exhibited good knowledge and substantive understanding about HPV infection a corresponding attitude towards vaccination was not evident. It was expected that the survey would also create awareness about HPV infection and the importance of HPV vaccination.

It was adduced through the study that, the knowledge of the females respondents was comprehensive but the males were predominantly had no knowledge as also found in a study conducted in Germany.Citation19 Higher grades for knowledge and understanding, remained tenebrous in practice as the scores for attitude, perception and views were not equitable with the scores for knowledge and understanding. 80% of the female respondents exhibited good knowledge and understanding but only 60% had positive attitude, perception and views about HPV infection and vaccination. Similar disparities subsist elsewhere and lackadaisical attitude, perception and views about HPV is a global concern.Citation20 The knowledge and understanding of respondents of urban areas supersedes (Central and Southern regions) that of the semi urban and rural areas (Northern and East coast regions). The knowledge and understanding among Malaysians were congruent to the response received in a similar study conducted in USA.Citation21,Citation22

It is evident through this study that the younger generation (74.2%) is more knowledgeable than the middle aged generation (46.4%). However, 68.3% of middle aged people exhibited better attitude, perception and views as compared with 54.5% of the people of ageless than 20 years. Severe repudiation towards vaccination was observed, it was found that only 7.6% strongly agreed to go for vaccination even if it was free. The number of males rejecting vaccine were proportionally higher than females. It may be higher as the males exhibited weak or wrong information about HPV vaccine, the study was in congruent to the study done in Nigeria.Citation23 Physicians have found cultural sensitivities to be a major impediment with the majority of Malaysians objecting to HPV vaccination.Citation24 Knowledge about the availability of Gardasil or Cervarix in market was very poor among males (36.4%), professionals (40.9%) and middle aged people (37.7%). A similar pattern was evident in rural areas, it is subsumed that strong awareness is required to make people compatible with HPV vaccine.Citation25,Citation26

Furthermore, a majority of the female respondents (72.5%) were aware that HPV can cause cancer. 90.8% of the female respondents were also aware that HPV may be responsible for genital warts. Similar responses were not expressed by male respondents suggesting there was a lack of information among them. Students displayed a better understanding of HPV related cancer and warts than compared with respondents in professional jobs. Married and single persons displayed equitable understanding in the this context. The responses echo the views of medical students in India.Citation15,Citation27

Sixty five percent of the population was aware that HPV can be sexually transmitted and 56.7% was aware (strongly agreed) that sexually active persons should essentially be vaccinated. But this understanding was not found in male respondents as also evident in previous studies.Citation28 Previous studies also found similar lack of knowledge about HPV among adolescent males. It has been suggested that the cost of vaccination and parenteral intervention are key factors responsible for poor awareness among the males. This situation continues to exist and nothing concrete has been done so far to infuse the need for HPV vaccination among malesCitation29

Appreciable knowledge and understanding about HPV exist among female respondents, students, single people, and urban population but a strong awareness is warranted for males, rural and married population. The Ministry of Health should take adequate steps to spread the awareness about the benefits of the HPV vaccine among the masses. There is a strong need for an awareness programme involving the private and non-governmental organization. An HPV information campaign should be organized at the community level to increase the awareness about the benefits of HPV vaccination. Fiji conducted a sensitization programme focussing on the local health workforce and the local population.Citation30

Regression analysis revealed an association of gender, age, and occupation with knowledge and understanding. The study also composed an association of gender, age with attitude, perception and views. Efforts should be made to customize interventions to target the local people who are more likely to have inadequate knowledge, and poor attitude, perception and views. Even though the Malaysian government has taken significant steps to convey the dangers of HPV infections, still the message has not been received among the masses. The situation is more alarming because the study found an indifferent or poor attitude among health care students and professionals towards HPV vaccination. The government should make HPV vaccination mandatory for first year university students as a similar national school-based HPV immunization programme was implemented effectively in Malaysia irrespective of the knowledge of HPV infections among teachers.Citation31

Limitations of the study

This study will allow the stakeholders in Malaysia to contrive interventions for creating awareness, especially about vaccination, among the local Malaysian population. However, convenience sampling was used for data collection due to limited manpower available. This may lead to biased selection of the data used in the study. The sample of size of 576 respondents maybe too small to represent the Malaysian population and hence the findings cannot be generalized for entire Malaysian population. The data presented are more applicable to educated adults. Further studies with bigger sample may address this issue in detail, but the present study still addresses a major healthcare problem in Malaysia.

Methods

This work describes a descriptive, cross sectional study conducted among the health care professional in Peninsular Malaysia. The study was conducted over a period of 3 months from March 2017 to May 2017. Young Malaysian aged less than 20 years (minimum age 17 years), professionals health care professionals aged between 20–35 years and middle aged people above 35 years (Maximum age 45 years) were included in the study. Information about the knowledge of HPV, awareness and acceptability of HPV vaccination and percentage of respondents already vaccinated, was collected by using self-administered structured questions. All participants were briefed about the objectives of the research project and the consent was obtained before recruitment as respondents.

Sample size and sampling method

The recommended numbers of respondents for this study was calculated using sample size calculator, Raosoft. Sample size was designed and constructed with the intention response ratio of 50%, confidence level 95% and margin of error 5%, the entire sample size actualized for this research work was tailored as 381 individuals. Nevertheless, 576 respondents contributed in the survey which pertains to being more than the intended sample size. Random sampling was used to obtain a representative sample of larger population and those samples which do not meet criteria desired were filtered out. Respondents were conveniently selected regardless of age, gender, marital status and occupation from Universti Putra Malaysia, Universiti Kuala Lumpur Royal College of Medicine Perak, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Kolej Poly Tech Mara Bangi, Universiti Malaya, UiTM Merbok, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Universiti Malaysia Perlis, UiTM Shah Alam, Hospital Raja Permaisuri Bainun,and Hospital Kuala Lumpur . The responses of the participants were filtered using the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

Malaysian students belonging to health care programmes (medical, pharmacy and nursing).

Malaysian citizens working in hospitals, clinics or health care institutes.

Exclusion criteria

Those who were not willing to participate in the study.

Overseas students or staff members.

Malaysian students from courses other than medical, pharmacy and nursing programmes.

Formation of questionnaires

A self-administered questionnaire was drawn up and used as an instrument to convoke data from the respondents. The first author was responsible for formulating the questionnaire with reference to the relevant previous studies in the literature.Citation20,Citation23,Citation28 The second author was authorized to check the face validity of the questionnaire before a pilot test was conducted. The pilot test was conducted and the internal consistency was validated by using Cronbach’s alpha. The questionnaire enclosed denominations based on socio-demographic (age, gender, region, marital status, occupation). The content of the questionnaire items were introduced in accordance with the objective of the study. The survey entailed three subdivisions with a set of 21 questions. The first subdivision of question consisted questions related to demographic information of the participants. The second section evaluated the knowledge and understanding of participants towards HPV infection and vaccination, a dichotomous response (‘Yes’ and ‘No’) was used for the study. The response to the questions for the third division was recorded on a 4 point Likert scale of agreement with a score of 4 for disagree, 3 for neutral, 2 for agree, and 1 for strongly agree. The questionnaire assessed the attitude and perception of the participants towards HPV infection and vaccination. This structured interview was carried out using Google Drive form, and it was fully documented.

Pilot test (questionnaire validation)

A test is usually done to validate whether the respondents are able to comprehend the questions. The pilot study was carried out online using google drive forms and the observations was recorded and evaluated, the pilot study allowed us to realize if any, revision or corrections was required in the questionnaire before it was used with the respondents. A cover letter was also provided to respondent stating the purpose, and importance of the survey. All the respondents were ensured about the confidentiality of the received information. Thirty four respondents (students) from Universiti Kuala Lumpur Royal College of Medicine Perak, Malaysia were chosen for the pilot study. The questions were slightly revised or modified after the pilot study.

Data analysis and management

Data were collected through the online questionnaire from 576 respondent. The responses received were assigned to different category. Microsoft Office Excel 2013 spreadsheets was used for data entry. The demographic information was expressed as statistically in terms of frequencies and percentage. Knowledge was assessed by awarding a score of 1 for a correct answer and 0 for a wrong answer. The scale for knowledge assessment was realized from minimum 0 to maximum 8 score. Median score was calculated as 6 for the study with an average score of 5.96. The definition of ``good’’ knowledge was based on participants’ mean knowledge score. A score of < 6 was considered poor knowledge while a score of ≥ 6 was considered good knowledge. Similarly attitude and perception of respondents was also analysed. The response was received on likert scale. The attitudes and perception of the target population were scored 4 for disagree, 3 for neutral, 2 for agree, and 1 for strongly agree. The scaled measurement attitude ranged from maximum 32 to minimum 8. The median score for the study was absorbed as 22, A score of < 22 was considered negative attitude and perception and a score of ≥ 22 was considered positive attitude and perception. Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between independent variables (demographic characteristics) and dependent variables (knowledge and attitudes). A P-value of less than 0.05 was reported as statistically significant. Minitab Trial version was used to analyse the data.

Ethical approval

The study was ethically approved by Institutional Ethical Approval Committee, Universiti Kuala Lumpur Royal College of Medicine Perak. Participants were briefed about the objective of the study and online consent was taken from the participants through google drive forms. All the response were collected voluntarily and the information was dealt with high level of confidentiality and anonymity.

Conclusion

The knowledge and understanding of local educated Malaysian health care individuals about HPV infection and vaccination are poor. The results also warrants poor attitude, perception and views about HPV among certain local Malaysians. Males, middle aged and married persons are required to be educated about the perils of HPV infection. The study also suggest that a major awareness programme should be initiated by the government.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ferris DG, Samakoses R, Block SL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Restrepo JA, Mehlsen J, Chatterjee A, Iversen OE, Joshi A, Chu JL, et al. 4-valent human papillomavirus (4vHPV) vaccine in preadolescents and adolescents after 10 years. Pediatrics. 2017:140(6).

- Abudukadeer A, Azam S, Mutailipu AZ, Qun L, Guilin G, Mijiti S. Knowledge and attitude of Uyghur women in Xinjiang province of China related to the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:110. doi:10.1186/s12957-015-0531-8.

- GLOBOCON. Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), France; 2012.

- Clifford G, Franceschi S, Diaz M, Munoz N, Villa LL. Chapter 3: HPV type-distribution in women with and without cervical neoplastic diseases. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):S3/26–34. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.026.

- Malaysia Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers. Fact sheet 2017. Barcelona, Spain: ICO/IARC HPV Information Centre; 2017.

- Koutsky LA, Ault KA, Wheeler CM, Brown DR, Barr E, Alvarez FB, Chiacchierini LM, Jansen KU. A controlled trial of a human papillomavirus type 16 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1645–1651. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020586.

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Lowy DR. HPV prophylactic vaccines and the potential prevention of noncervical cancers in both men and women. Cancer. 2008;113:3036–3046. doi:10.1002/cncr.23764.

- Gardasil, Approved Products. Human papillomavirus vaccine. New Hampshire Avenue (Silver spring, MD, USA): Consumer Affairs Branch (CBER), U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information; 2015.

- Gardasil 9, Approved Products. Human papillomavirus vaccine. New Hampshire Avenue (Silver spring, MD, USA): Consumer Affairs Branch (CBER), U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Highlightsof prescribing information; 2015.

- Cervarix, Approved Products. Human papillomavirus vaccine. New Hampshire Avenue (Silver spring, MD, USA): Consumer Affairs Branch (CBER), U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Highlightsof prescribing information; 2015.

- Musa MB, Yusof FBM, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Sakamoto J. Cancers affecting women in malaysia. Ann Cancer Res Therap. 2011;19:20–25. doi:10.4993/acrt.19.20.

- Narimah A, Rugayah HB, Tahir A, Maimunah AH. Cervical cancer screening, National Health and Morbidity Survey 1996. Vol. 19. Kuala Lumpur: Public Health Institute, Ministry of Health, Malaysia; 1999.

- Kamaruddin DD. Cervical cancer third most common cancer among Malaysian women. New Strait Times, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2016.

- Ezat SW, Hod R, Mustafa J, Mohd Dali AZ, Sulaiman AS, Azman A. National HPV immunisation programme: knowledge and acceptance of mothers attending an obstetrics clinic at a teaching hospital, Kuala Lumpur. Asian Pace J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2991–2999.

- Khoo CL, Teoh S, Rashid AK, Zakaria UU, Mansor S, Salleh FN, Nawi MNM. Awareness of cervical cancer and HPV vaccination and its affordability among rural folks in Penang Malaysia. APJCP. 2011;12:1429–1433.

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Herrero R, Bray F, Bosch FX, De Sanjosé S, Castellsagué X. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2016;4:e453–63. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30099-7.

- Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:107–114. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013.

- Badgujar VB, Ansari MT, Abdullah MS. Knowledge, attitude, ignorance and practice of obese Malaysians towards obesity. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2016;7:197–202. doi:10.5958/0976-5506.2016.00039.5.

- Blödt S, Holmberg C, Müller-Nordhorn J, Rieckmann N. Human Papillomavirus awareness, knowledge and vaccine acceptance: A survey among 18-25 year old male and female vocational school students in Berlin, Germany. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22:808–813. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckr188.

- Khan TM, Buksh MA, Rehman IU, Saleem A. Knowledge, attitudes, and perception towards human papillomavirus among university students in Pakistan. Papillomavirus Res. (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2016;2:122–127. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2016.06.001.

- Mohammed KA, Subramaniam DS, Geneus CJ, Henderson ER, Dean CA, Subramaniam DP, Burroughs TE. Rural-urban differences in human papillomavirus knowledge and awareness among US adults. Prev Med. 2018;109:39–43. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.016.

- Blake KD, Ottenbacher AJ, Finney Rutten LJ, Grady MA, Kobrin SC, Jacobson RM, Hesse BW. Predictors of human papillomavirus awareness and knowledge in 2013: gaps and opportunities for targeted communication strategies. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:402–410. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.024.

- Makwe CC, Anorlu RI, Odeyemi KA. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and vaccines: knowledge, attitude and perception among female students at the University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2012;2:199–206. doi:10.1016/j.jegh.2012.11.001.

- Wong LP. Physicians’ experiences with HPV vaccine delivery: evidence from developing country with multiethnic populations. Vaccine. 2009;27:1622–1627. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.107.

- Uzunlar O, Ozyer S, Baser E, Togrul C, Karaca M, Gungor T. A survey on human papillomavirus awareness and acceptance of vaccination among nursing students in a tertiary hospital in Ankara, Turkey. Vaccine. 2013;31:2191–2195. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.033.

- Ozyer S, Uzunlar O, Ozler S, Kaymak O, Baser E, Gungor T, Mollamahmutoglu L. Awareness of Turkish female adolescents and young women about HPV and their attitudes towards HPV vaccination. APJCP. 2013;14:4877–4881.

- Pandey D, Vanya V, Bhagat S, Vs B, Shetty J. Awareness and attitude towards human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine among medical students in a premier medical school in India. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40619. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040619.

- Zou H, Meng X, Jia T, Zhu C, Chen X, Li X, Xu J, Ma W, Zhang X. Awareness and acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among males attending a major sexual health clinic in Wuxi, China: A cross-sectional study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1551–1559. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1099771.

- Wong LP, Edib Z, Alias H, Mohamad Shakir SM, Raja Muhammad Yusoff RNA, Sam IC, Zimet GD. A study of physicians experiences with recommending HPV vaccines to adolescent boys. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017. doi:10.1080/01443615.2017.1317239.

- La Vincente SF, Mielnik D, Jenkins K, Bingwor F, Volavola L, Marshall H, Druavesi P, Russell FM, Lokuge K, Mulholland EK. Implementation of a national school-based human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine campaign in Fiji: knowledge, vaccine acceptability and information needs of parents. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1257. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2579-3.

- Ling WY, Razali SM, Ren CK, Omar SZ. Does the success of a school-based HPV vaccine programme depend on teachers’ knowledge and religion? – A survey in a multicultural society. APJCP. 2012;13:4651–4654.