ABSTRACT

In patients undergoing immunotherapy, the quality of the immune response is reduced, which may negatively affect the efficacy of vaccination. This study was conducted in order to evaluate the efficacy of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine in patients using immunomodulators. Seronegative patients for HBV who were using biological agents, were included in the study. The vaccination was administered on the standard schedule in 3 doses of 20 or 40 µg/ml. Eighty-two patients (52%) were males and the mean age of all patients was 44,8 ± 10,3 years. Among these 109 patients, 83 had psoriasis, 12 had Crohn’s disease, six had rheumatoid arthritis, three had ulcerative colitis, three had hydradenitis supurativa, one had Behcet’s disease and one had ankylosing spondylitis. The biological agents that were being used by these patients were adalimumab (62), ustekinumab (25), infliximab (12), etanercept (9) and golimumab (1). Seventy-three of the patients were vaccinated with a dose of 20 µg/ml and 36 with 40 µg/ml. The anti-HBs titers of fifty-eight (53.2%) patients were above 10 mIU/ml. The antibody response rate was lowest in infliximab-users (16.7%) (p = 0.007), which was followed by adalimumab (48.4%), and higher protection rates were achieved in patients using ustekinumab and etanercept (72% and 88.9%, respectively; p < 0.05). The HBV vaccine response rate in patients using immunomodulators was significantly lower than that in immunocompetent patients. Furthermore, high dose vaccination did not increase the response rate. Clinicians should take into account administering HBV vaccination before treatment with biological agent in patients who have negative HBV serology.

Inroduction

Immunomodulatory drugs inhibit the inflammation cascade at various stages and are used in systemic inflammatory diseases associated with autoimmunity. Infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, etanercept and ustekunimab are immunomodulatory drugs used in immune-mediated diseases. Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that directly inhibits TNF-α. Adalimumab and golimumab are humanized monoclonal TNF-α antibodies containing human constant and variable regions. Etanercept is a recombinant TNF-α receptor fusion protein.Citation1 Ustekunimab is used only in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, which does not directly inhibit TNF-α, but indirectly inhibits it by blocking the IL-12 and IL-23.Citation2 These drugs are defined as ‘immunomodulatory drugs’ that impair the T cell activation and therefore, reduce the response of the body to the Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) vaccine that protects against an important worldwide health problem.Citation3

HBV infection is a chronic viral disease that affects 240 million people worldwide.Citation4 The most important way to control morbidity and mortality associated with HBV is vaccination. Studies show that in the normal population, there is only 5–10% unresponsiveness to the HBV vaccine prepared with recombinant DNA technology.Citation5,Citation6 However, TNF-α inhibitors impair the T-cell activation and reduce the HBV response rate.Citation3 Ustekunimab inhibits TNF-α indirectly by blocking IL-12 and IL-23 and disrupts T-cell functions.Citation2 Thus, the use of Ustekunimab is expected to reduce the response rates to the vaccine. Protection against infections via vaccination is very important in patient groups using immunomodulatory drugs, because when these patients are infected with HBV, controlling the disease is much more difficult than that in the normal population, and morbidity and mortality increase.Citation7 For all these reasons, effective vaccination is very important and a high dose (40 µg/ml) of HBV vaccine is recommended in immunosuppressive patient groups.Citation8 However, there is no study in the PUBMED search evaluating the protection rates with high dose hepatitis B vaccination in immunosuppressants. Since the immune response rate to the usual dose (20 µg/ml) of hepatitis B vaccine is low in individuals taking immunomodulatory drugs, the aim was to evaluate whether the adequate immune response is achieved or not using high dose (40 µg/ml) vaccine.

Results

A total of 109 patients were included in the study. Eighty-seven (52%) of the patients were male, and the mean age was 44.8 ± 10.3 years. All of them were Turkish. Forty-nine (45%) of the patients smoked. There were 29 (27%) patients with a BMI greater than or equal to 30. There was no concomitant drug user. The indications for immunomodulatory drug use were psoriasis (n = 83), Crohn’s disease (n = 12), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n = 6), ulcerative colitis (n = 3), hydradenitis suppurativa (n = 3), Behçet’s disease (n = 1) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) (n = 1). The diseases and the demographic characteristics did not affect the antibody response to HBV vaccination (). Out of the 15 patients who had been diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and treated with TNF-α inhibitors, seven (46.6%) responded to the HBV vaccine.

Table 1. Comparison of the demographic characteristics, primary diseases and vaccine responses of the responder and non-responder patient groups.

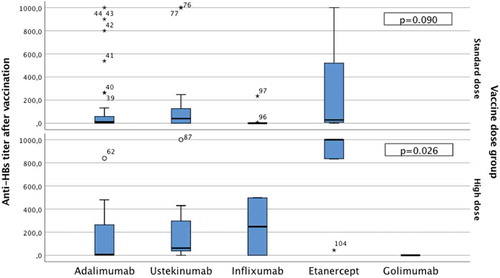

The immunomodulatory drugs used by the patients were adalimumab (n = 62), ustekinumab (n = 25), inflixumab (n = 12), etanercept (n = 9) and golimumab (n = 1). When the effect of these drugs on the rate of the protective antibody response to the standard dose and high dose HBV vaccine was examined, the antibody response to vaccination was low in infliximab users (p = 0.007), while higher response rates were observed in ustekinumab and etanercept users (p = 0,032 and 0,035respectively) ().

Table 2. Vaccine response rates according to the immunomodulatory drug used.

When the response rates were examined after hepatitis B vaccination, 58 (53.2%) of the patients were accepted as ‘responders’, and 51 (46.8%) were ‘non-responders’. Seventy three (67%) of the patients received the standard dose vaccine, while 36 (33%) received high dose vaccine. The response rates according to the vaccine dose were 49.3% in the standard dose group and 61.1% in the high dose group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (). There was no statistically significant difference between the standard and high dose vaccine among the drug groups ().

Table 3. Comparison of vaccine response rates in standard and high dose HBV vaccinations.

Table 4. Comparison of standard and high dose vaccine responses according to the immunomodulatory drug used.

When the duration of immunomodulatory drug use was evaluated, the response rate was 52.2% among patients using the drug for less than one year and 54.8% for those using the drug for longer than one year. The difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.797)

The mean anti-HBs titer obtained after HBV vaccination was 245 IU/mL. The anti-HBs titers were 245 IU/mL, 54 IU/mL, 112 IU/mL, 83 IU/mL, 61 IU/mL, and 0 IU/mL in patients using etanercept, adalimumab, ustekinumab, infliximab and golimumab, respectively. When the anti-HBs titers were compared according to the vaccination dose, there was no significant difference among the standard dose vaccinations, whereas there was a statistically significant difference (p = 0.026) among those vaccinated with high dose vaccine. This difference had arisen from the etanercept group; in particular, the serum anti-HBs level of patients using etanercept was significantly higher than the that of others ().

When comparing the serum anti-HBs titers after HBV vaccination, the mean of the anti-HBs titers was 119.2 ± 265.6 IU/mL in the standard dose vaccine group and 245.2 ± 351.7 IU/mL in the high dose vaccine group. The difference between the standard and the high dose vaccination was statistically significant (p = 0.039).

Discussion

Approximately 5% of the world population has chronic HBV infection, 25% of which develop chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma.Citation9 Since the HBsAg carrier rate is 4–7% in Turkey, it is considered as an intermediate endemic region.Citation10,Citation11 HBV vaccination, especially in risk group patients, plays an important role in public health protection, due to high carrier rates and the resulting reactivation and life threatening complications.Citation6

It is believed that antigen specific B and T lymphocytes play significant roles in the antibody response to HBV vaccine.Citation12 Together with cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, they stimulate the vaccine response.Citation13 Since TNF-α inhibitor treatment suppresses the T-cell mediated immune response, the B-cell mediated immune response also decreases.Citation14,Citation15 Immunomodulatory drugs are an important drug option in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, especially in patients resistant to other drugs. They specifically target one of the immunological or genetic mediators. These drugs are well known to suppress the immune system.Citation13 For this reason, patients receiving immunomodulatory treatment are susceptible to bacterial and viral infections, and this issue has been of interest in recent years.Citation16 Another point to keep in mind is that these drugs render an effective vaccination challenge against viral diseases.Citation15

With standard dose HBV vaccination, an adequate antibody response is obtained in over 90% of healthy individuals, while this rate significantly decreases in immunosuppressed patients.Citation3,Citation6 Similarly, the vaccine response rates are decreased in patients receiving TNF-α blocker therapy.Citation14,Citation17 The first study on this subject was carried out by Ravikumar et al., which reported that the rate of response to the HBV vaccination had decreased to 33% in patients receiving etanercept therapy.Citation17 In another study, only one of 25 patients with RA and only three of 27 patients with spondyloarthritis under infliximab treatment had responded to HBV vaccination.Citation14 Moses et al. reported that infliximab use was found not to affect the vaccine response rate in children with IBD who received the booster dose of the HBV vaccine.Citation18 In our study, the overall HBV vaccination response rate was 53.2% in patients under TNF-α blockade therapy. However, when the responses to vaccination were evaluated among drug groups one by one, we found that there was a wide spectrum in the response rates. Drugs used by our patient population include adalimumab, ustekinumab, infliximab, etanercept, and golimumab. There was one patient, who had received golimumab treatment and HBV vaccination, and who did not develop an antibody response. Since the number of patients was only one, no statistical analysis was performed. Based on these results, it is possible to say that the immunomodulatory agent used is highly effective in developing an antibody response to HBV vaccination.

It is known that, after HBV vaccination, an anti-HBs titer value of more than 10 IU/mL is protective in infection.Citation6 A study conducted by the Ministry of Health of our country on HBV vaccination during childhood reported the average anti-HBs titers as 720 IU/mL.Citation19 McMahon BJ et al. evaluated the seroconversion level in healthy adults after vaccination, and reported the average anti-HBs titer as 822 mIU/mL.Citation20 The antibody titers of anti-HBs also decrease during HBV vaccination in patients under TNF-α blockade therapy. In the study by Salinas et al., the anti-HBs titers were significantly lower in patients using etanercept and infliximab than in the control group, but it was comparable,Citation14 whereas in our study, the average anti-HBs titer level in patients responsive to the vaccine was determined to be 245 IU/mL. As the immunomodulatory drugs were evaluated separately, the etanercept receiving group was seen to have the highest anti-HBs titer followed by adalimumab, ustekinumaband infliximab. This indicates that even in the patients using immunomodulatory agents when compared to the normal population, the desired levels of anti-HBs were not achieved. When analyzed according to the vaccination dose, there was no significant difference in the serum anti-HBs titers in patients who had received the standard dose vaccination between different immunomodulatory drugs used. However, when using high dose HBV vaccine in patients under etanercept treatment, higher antibody titers could be obtained compared to the standard dose vaccination.

High dose HBV vaccination is recommended for immunosuppressed patients. End stage renal failure and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are also included in this group.Citation8 The rate of response to the standard dose HBV vaccine in chronic renal failure is around 50–60%.Citation21 With a high dose of vaccination, the antibody response rate can be increased up to 85%.Citation9 Similarly, the protection rate against HIV infection is around 44% with 20 μg/ml of vaccine, which rises up to 72% with 40 μg/ml of the vaccine dose.Citation22 There are also other groups of patients in which the efficacy of high dose vaccination has been investigated. In a study on drug addicts, it was shown that high doses of the HBV vaccine did not increase the response rate, but significantly increased the serum anti-HBs concentration.Citation23 In a review of 11 trials and 961 cirrhotic patients, the vaccine response rate was reported as 38% at the standard dose, which increased to only 53% at high dose.Citation24 In our study, the immunosuppressed patients were those under immunomodulatory drug therapies and in this patient group, the protective antibody formation rate was 49.3% with the standard dose, and this rate increased to 61.1% with high dose vaccination. However, this increase was not statistically significant. Another factor affecting the HBV vaccine response is the age of the patient.Citation6 The response rate of healthy children to the HBV vaccine is around 95–99% 12. While this rate is 90% in adults younger than 40 years, it decreases to under 90% in those older than 40 years, and in individuals older than 60 years, only 75% exhibit an antibody response.Citation6 In cases such as individuals working in healthcare units and in security, hemodialysis patients, HIV positive, and other immunosuppressive patients, it is recommended to evaluate the immune status and measure the level of antibody after vaccination.Citation25 Apart from age, there are also other factors such as smoking, obesity, gender and the presence of immunosuppressive diseases, which affect the vaccine response.Citation26 On account of the fact that immunomodulatory drugs cause immunosuppression, we studied their effect on the HBV vaccine response in a group of patients and found that factors such as age, smoking, obesity, and chronic diseases did not affect the vaccine response significantly. The lack of a difference between these variables may have been caused by the heterogenous distribution of variables in both groups and the low number of cases.

Antibody response developed in only 53.2% of the patients and this rate was found to be lower than in the normal population.Citation6 In this case it can be stated that measurement of antibody is very important in patients receiving the HBV vaccine along with immunomodulatory drugs. Compared to other risk factors, the presence of immunosuppression is a much more significant risk factor causing unresponsiveness to the vaccine.

Another factor that affects the vaccine response is the presence of a chronic underlying disease. For instance, in patients with chronic renal failure and HIV infection, there is a low responsiveness to the vaccine. However, in patients with Psoriasis, who constituted the largest group in our study, no unresponsiveness to the HBV vaccine was observed. Even in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases such as AS and RA, a low responsiveness to the HBV vaccine was not reported.Citation27,Citation28 TNF-α inhibitors, which are used as treatment for these diseases, may decrease the response to the HBV vaccine.

Another disease group that used TNF-α inhibitors comprised inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), wherein the response to the HBV vaccine was low (regardless of the given treatment). In the study by Gisbert et al., 59% of the patients had an anti-HBs level higher than 10 IU/mL, but this rate decreased to 46% in patients taking TNF-α inhibitors.Citation24 Rahier et al. reported that patients with IBD had a significantly low response rate to the HBV vaccine.Citation27 In our study, the response rate in patients diagnosed with IBD and treated with TNF-α inhibitors to the HBV vaccine was low, similar to other reports.

The most important limitation of our study was that the number of patients enrolled was low and the diagnostic groups were heterogeneous. Furthermore, the drug groups were heterogeneously distributed. This made it difficult to clearly define the relationship of the HBV vaccine response with the drugs used and the disease groups. However, in this study, it would be reasonable to say that the response rates to HBV vaccination (standard or high dose) in patients under immunomodulatory medication was very low and this was independent of the underlying diseases. Literature data suggest that unresponsiveness to the HBV vaccine prepared with recombinant DNA technology in the general population varies between 5% to 10%. However, this was expected to be higher in patients taking TNF-α inhibitors, since it impairs the T-cell activation and reduces the HBV response rates. In our study, we concluded that a minimum clinically significant difference for unresponsiveness to HBV vaccination should be 25% in patients taking immunomodulatory drugs. A sample size estimation based on this minimum clinically significant difference of 25%, a type I error level of 5%, and two-tailed hypothesis design revealed that 98 patients would be sufficient to achieve a final study power of 80%, 49 patients in each group of responders and non-responders. We conducted a chart review for the use of immunomodulatory drugs (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, ustekinumab, golimumab) between May 2016 and February 2018 in our clinic, and found that 109 patients had been treated with immunomodulatory drugs, and included all patients in the study. There were 58 responders, and 51 non-responders. The final power of the hypothesis tests for the response in immunomodulatory drug groups was 59% for ustekinumab, 62% for etanercept, and 77% for infliximab. We think that our results are methodologically appropriate and statistically strong enough to be considered for evaluation for their clinical significance, based on the calculations of priori sample size estimations, and post-hoc power analyses.

Regardless of the underlying autoimmune diseases, immunomodulator drugs suppress the expected effective antibody response to vaccination. Moreover, the desired protection rates cannot be achieved despite HBV vaccination carried out at high doses. For this reason, the most effective method to immunize this patient group would be completion of their vaccination before initiation of immunomodulatory therapy.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

The medical files of seronegative patients for HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc IgG, who had been referred to our outpatient clinic for the use of immunomodulatory drugs (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, ustekinumab, golimumab) between May 2016 and February 2018, were retrospectively evaluated. None of these patients had used any additional immunosuppressive drugs. The serum level of hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) was examined in patients over the age of 18 after vaccination with the standard dose (20 μg/mL) or high dose (40 μg/mL) hepatitis B vaccine and they were included in the study. The age, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), smoking habit, concomitant drug use, primary disease, treatment protocol and duration of use, and serum anti-HBs titers of the participants were recorded. Obesity was defined as having a body mass index of over 30 kg/m2.

The vaccines were brought to the hospital by the Republic of Turkey health ministry, abiding by the cold chain rules. The standard vaccine dose was 20 μg/ml, while the high dose was 40 μg/ml. The vaccine (Engerix-B) was applied intramuscularly to the left deltoid muscle at three doses (0, 4, 24 weeks). The serum anti-HBs titer was measured one month after the last dose of the vaccine. Serological tests were performed using the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, ELISA method (ETIMAX 3000, Diasorin, Italy). According to the serum Anti-HBs titers, the patients having an antibody level of over 10 IU/mL were defined as ‘responders’, and those having a lower than 10 IU/mL antibody level as ‘non-responders’.Citation13 This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Health Sciences, Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital. Signed informed consent forms were obtained from all the patients.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive statistics of the study results were presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for the numerical variables. The independent groups were compared using the Chi-square test in terms of categorical data and the Wilcoxon test was used for the numerical data. The Anti-HBs titers were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric variance analysis between the drug groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for the post-hoc analyses.The package program, SPSS 21 software (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA), was used for analyses of the study results and a 5% Type-I error was considered statistically significant. The statistical significance level was accepted as 0.05 in all tests.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pecoraro V, De Santis E, Melegari A, Trenti T. The impact of immunogenicity of TNFα inhibitors in autoimmune inflammatory disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(6):564–75. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.04.002.

- Croxtall JD. Ustekinumab: a review of its use in the management of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Drugs. 2011;71(13):1731–53. doi:10.2165/11207530-000000000-00000.

- Saco TV, Strauss AT, Ledford DK. Hepatitis B vaccine non-responders: possible mechanisms and solutions. AnnAllergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):320–27. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.03.017.

- World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017. Geneva; 2017 [accessed 2018 June]. www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/.

- Zuckerman JN, Sabin C, Craig FM, Williams A, Zuckerman AJ. Immune response to a new hepatitis B vaccine in healthcare workers who had not responded to standard vaccine: randomised double blind doseresponse study. BMJ. 1997;314(7077):329–33. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7077.329.

- Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, Alter MJ, Bell BP, Finelli L, Rodewald LE, Douglas JM, Janssen RS, Ward JW. Centers for disease control and prevention. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis b virus infection in the United States recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) Part II: immunization of adults. MMWR RecommRep. 2006;55:1–33.

- Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):215–19. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.039.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67(2):370–98. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021.

- Inoue T, Tanaka Y. Hepatitis B virus and its sexually transmitted infection – an update. Microb Cell. 2016;3(9):420–37. doi:10.15698/mic2016.09.527.

- Uner A, Kirimi E, Tuncer I, Ceylan A, Turkdogan MK, Abuhandan M. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in children in the Eastern Anatolia. East J Med. 2001;6:40–42.

- Demirpence O, Sahin H, Gumus A, Korkmaz E, Hakim F, Uysal F. HbsAg and anti HCV seroprevalence in an eastern province of Turkey. Cumhuriyet Med J. 2016;38(1):29–34. doi:10.7197/cmj.v38i1.5000156049.

- Tosun S. Hepatitis B virus vaccine. Viral Hepat Jl. 2012;18(2):37–46. doi:10.4274/Vhd.24633.

- Filippelli M, Lionetti E, Gennaro A, Lanzafame A, Arrigo T, Salpietro C, Rosa ML, Leonardi S. Hepatitis B vaccine by intradermal route in non responder patients: an update. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(30):10383–94. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10383.

- Salinas GF, Rycke LD, Barendregt B, Paramarta JE, Hreggvidstdottir H, Cantaert T, Bur M, Tak PP, Baeten D. Anti-TNF treatment blocks the induction of T cell-dependent humoral responses. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):1037–43. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201270.

- Aringer M. Vaccination under TNF blockade - less effective, but worthwhile. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(3):117. doi:10.1186/ar3808.

- Baddley JW, Cantini F, Goletti D, Gomez-Reino JJ, Mylonakis E, San-Juan R, Fernández-Ruiz M, Torre-Cisneros J. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (Soluble immune effector molecules [I]: anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agents). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(2):10–20. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.025.

- Ravikumar R, Owen T, Barnard J, Divekar AA, Conley T, Cushing E, Mosmann TR, Sanz I, Looney J, Anolik J, et al. Anti-TNF therapy in RA patiens alters hepatitis B vaccine responses. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;56:36.

- Moses J, Alkhouri N, Shannon A, Raig K, Lopez R, Danziger-Isakov L, Feldstein AE, Zein NN, Wyllie R, Carter-Kent C. Hepatitis B immunity and response to booster vaccination in children with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:133–38. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.295.

- Tosun SY, Karaca M, Ertilav M, Akkum K. The evaluation of hepatitis B vaccine efficacy used in health care centers. TurkiyeKlinikleri J Pediatr. 2003;12:77–80.

- McMahon BJ, Bruden DL, Petersen KM, Bulkow LR, Parkinson AJ, Nainan O, Khristova M, Zanis C, Peters H, Margolis HS. Antibody levels and protection after hepatitis B vaccination: results of a 15-Year Follow-up. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(5):333–41. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00008.

- Duman H, Meuer S, Meyer zumBuschenfelde KH, Köhler H. Hepatitis B vaccination and interleukin 2 receptor expression in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1990;38:1164–68.

- Mena G, García-Basteiro AL, Bayas JM. Hepatitis B and A vaccination in HIV-infected adults: A review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(1):2582–98. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1055424.

- Feng Y, Shi J, Gao L, Yao T, Feng D, Luo D, Li Z, Zhang Y, Wang F, Cui F, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of high-dose hepatitis B vaccine among drug users: A randomized, open-labeled, blank-controlled trial. Hum VaccinImmunother. 2017;13(6):1297–303. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1283082.

- Aggeletopoulou I, Davoulou P, Konstantakis C, Thomopoulos K, Triantos C. Response to hepatitis B vaccination in patients with liver cirrhosis. Rev Med Virol. 2017;27(6):1942. doi:10.1002/rmv.1942.

- Clemens R, Sanger R, Kruppenbacher J, Höbel W, Stanbury W, Bock HL, Jilg W. Booster immunization of low- and non-responders after a Standard three dose hepatitis B vaccine scheduleresults of a post-marketing surveillance. Vaccine. 1997;15:349–52.

- Averhoff F, Mahoney F, Coleman P, Schatz G, Hurwitz E, Margolis H. Immunogenicity of hepatitis B Vaccines. Implications for persons at occupational risk of hepatitis B virus infection. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:1–8.

- Rahier JF, Moutschen M, Gompel AV, Ranst MV, Louis E, Segaert S, Masson P, De Keyser F. Vaccinations in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Rheumatolog. 2010;49(10):1815–27. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq183.

- Gisbert JP, Villagrasa JR, Rodríguez-Nogueiras A, Chaparro M. Efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination and revaccination and factors impacting on response in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(10):1460–66. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.79.