ABSTRACT

Children are at higher risk of influenza complications. The goals of this article are, estimating influenza vaccination coverage of Health Care Workers (HCWs) in tertiary children hospital, evaluating attitudes and practices of HCWs and evaluating whether HCWs vaccination uptake improved with onsite vaccination campaign. This was a before-after trial, which was carried out in a tertiary children hospital at 2017–2018 influenza season. The vaccination team visited all participants and collected information about previous vaccination uptake, attitudes and beliefs of HCWs by means of an anonymous questionnaire. Moreover, the influenza vaccine was offered onsite to all participants. A total of 572 HCWs participated in this study (response rate: 94.2%). Coverage was 10.8% in 2016–17 season and 39.9% in 2017–18 season (p < 0.0001). Multivariate regression analysis showed that being younger than 35 years (OR: 2.09), being vaccinated in previous season (OR: 47.02) and professional category of the participant (clinicians being reference group; OR: 1.73 for support staff and OR: 0.23 for nurses,) were significantly associated with vaccination uptake in 2017–18 season [95% CI]. None of the participants with former bad experience about vaccination was vaccinated in 2017–2018 season. And 90% of the participants having lack of knowledge about the vaccine were vaccinated in 2017–2018 season. After onsite vaccination campaign, influenza vaccination coverage improved significantly among HCWs. In order to achieve target vaccination coverage we should break down the prejudices with a comprehensive education program.

Abbreviations: OR- Odds ratio; CI- confidence interval

Introduction

Seasonal influenza affects the entire population. In 2014, World Health Organization (WHO) stated that influenza is an important public health problem and recommended and promoted influenza vaccination for people with chronic diseases, pregnant women, children and health care workers (HCWs).Citation1 HCWs are an important priority group for influenza vaccinationbecause vaccination of HCWs reduces the risk of staff acquiring and transmission of influenza to susceptible patients, and reduce morbidity and mortality.Citation2

Despite the strong recommendations for influenza vaccination in HCWs made by health organizations including WHO, the acceptance and coverage rate of vaccination among HCWs varied widely among countries and institutions.Citation2 Vaccination coverage rate of HCWs varies between 12.3–76.1%.Citation3-Citation5 Previous studies showed that free vaccination policies, offering incentive awards for vaccination, education about benefits of influenza vaccination increased vaccination coverage among HCWs in adults hospitals.Citation6,Citation7 The Turkish Ministry of Health offers influenza vaccine to HCWs free of charge. However, there is no published vaccination recommendation for HCWs. Only a few studies have investigated the influenza vaccination coverage rate of HCWs in Turkey and most of them were conducted in adult hospitals during the 2009 influenza pandemic.Citation3-Citation5 Children younger than 24 months of age and immune-compromised children are at increased risk of complications of influenza and influenza related hospitalization. Thus HCWs working in a children hospital are targeted in the present study. The aim of the present study was to investigate the influenza vaccination coverage of HCWs before and after on-site vaccination intervention and to evaluate attitudes and practices of HCWs about vaccination.

Results

A total of 572 HCWs participated in the study (response rate, 94.2%). No significant difference was found in the distribution of profession, age and sex among responders and non-responders (p = 0.29, p = 0.21 and p = 0.24 respectively).

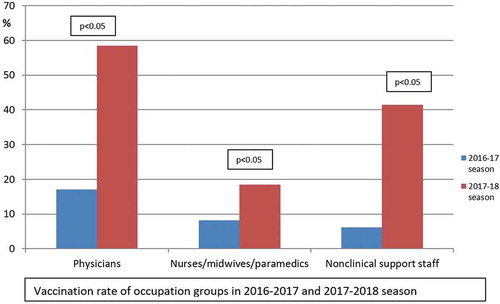

The study included 212 (37.1%) physicians, 196 (34.3%) nurses/midwives/paramedics and 164 (28.7%) nonclinical support staff. Vaccination coverage according to occupation group was shown in . The mean age was 33.5 ± 7.6 (range, from 20 to 64 years) in the survey. Four hundred thirty four (75.9%) of the participants were women.

In 2016–17 season, 10.8%, of the HCWs had taken the influenza vaccination, which increased to 39.9% in 2017–18 season. There was a significant increase in vaccination rate in all occupation groups () (p < 0.001). Physicians had the highest vaccination rate (58.5%) among all groups in 2017–2018 season. Onsite vaccination let an increase on influenza vaccination rate of approximately 29.1% among all 3 groups of participants (physicians, 41.5%: nurses/midwives/paramedics, 10.2% and nonclinical support staff, 35.4%) ().

Table 1. Vaccination coverage according to occupation group.

Table 2. The role of age, gender, profession and vaccination status in 2016–17 (previous) season in determining the changes in vaccination status in 2017–18 season.

Figure 1. Vaccination percentages of occupation groups in 2016–17 season and after the implementation of onsite vaccination campaign of 2017–18 season. Bivariate comparison of vaccination rate demonstrates a significant improvement on vaccination coverage among HCWs (P < 0.05, McNemar’s test).

Multivariate regression analysis showed that being younger than 35 years (OR: 2.09), being vaccinated in previous season (OR: 47.02) and professional category of the participant (clinicians being reference group; OR: 1.73 for support staff and OR: 0.23 for nurses,) were significantly associated with vaccination uptake in 2017–18 season [95% CI] ().

The main reason for vaccination in all groups was “to protect myself and my family” in 2017–18 season (95.6%). “To protect patients” was reported as a reason by only 1.7% of the HCWs ().

Table 3. Description of the answers to open-ended questions about vaccination status in 2016–17 and 2017–2018 season.

In all of the profession groups the most frequent reason for non-vaccination was “influenza vaccination is unnecessary and ineffective” in both seasons (69.4% in 2016–2017 season and 66.3% in 2017–2018). “Lack of knowledge about the vaccine” was more frequently reported among the nonclinical support staff group (26%) than the others in 2016–2017 season (). Ninety percent (90%) of the non-vaccinated HCWs for the reason of having lack of knowledge about the influenza vaccine in 2016–2017 season was vaccinated in 2017–2018 season during the onsite vaccination campaign ().

Table 4. The percentages regarding vaccination status of HCWs in 2017–2018 season with respect to their non-vaccination reasons in previous season.

Among all the non-vaccinated HCWs “Having bad experience about influenza vaccination” was the second frequent reason for non-vaccination (16.3%) in 2017–2018 season (). They claimed that influenza vaccination uptake caused them to have sickness more frequently. None of the non-vaccinated HCWs for the reason of having former bad experience about influenza vaccination in 2016–2017 season, was vaccinated in 2017–2018 season.

In 2017–2018 season 14 HCWs rejected vaccination due to contraindication beliefs. However only two of them had valid contraindication like allergic reactions. 12 participants (3.5% among non-vaccinated HCWs) rejected vaccination due to pregnancy in 2017–2018 season.

Discussion

This study showed that statistically significant increase in vaccination coverage was observed with an onsite vaccination campaign. After onsite vaccination intervention, vaccination coverage in our tertiary children hospital was 39.9% among HCWs. Age, professional category of the participant and being vaccinated in previous season were associated with vaccination uptake in 2017–18 season.

Although the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all HCWs should be a high priority group for vaccination efforts to reduce influenza-related morbidity and mortality among HCWs and their patients, vaccination coverage of HCWs is varies across many countries. A study conducted in Istanbul, Turkey after the H1N1 pandemia, reported that only 23.1% of HCWs had taken the influenza vaccine,Citation8 whereas another study also performed in Turkey with 1658 participants showed that 35.3% of HCWs were vaccinated against influenza during the influenza pandemic.Citation9 And in the USA, 78.6% of survey respondents reported receiving vaccination during the 2016–2017 influenza season.Citation10 To our knowledge this is the first study in children hospital that shows a high response rate for the influenza vaccine. Our study showed that vaccination coverage among HCWs was only 10.8% in 2016–2017 season whereas coverage increased to 39.9% in 2017–2018 season after an onsite vaccination campaign.

Previous studies regarding evaluation of the effect of intervention programs like provision of free vaccine, easy access to the vaccine and educational activities to improve knowledge and behavior, showed that mandatory vaccination and on-site vaccination policy for HCWs are the most effective interventions in vaccine uptake.Citation7 In Turkey, there is a serious resistance to influenza vaccination.Citation11 For this reason mandatory vaccination policy is not appropriate. In parallel to our study, X Yu et al. reported that offering onsite vaccination and personal reminders were associated with increased vaccination coverage among HCWs in ambulatory care settings alone.Citation12 According to our study it is understood that, free vaccination and making announcements are not sufficient for achieving desirable increase in the vaccination coverage among HCWs. Free vaccination was included in nearly all programs and it was thought to be essential component of vaccination program.Citation13 In our study after on-site vaccination campaign, the vaccination rate was the lowest among nurses. This result is in line with a meta-analysis showing that being a nurse was associated with a lower vaccination rate.Citation14 A previous study also showed that the nursing staff was more likely to refuse vaccination and this was depended on lack of knowledge.Citation8 In parallel with the results of previous studies being vaccinated in previous season appeared as a strong positive predictor for vaccination in the present study.Citation15,Citation16

In our study among participating HCWs, the ones younger than 35 years age are more likely to accept vaccination uptake with an odds ratio of 2.09. This might be explained by the fact that older HCWs are more conservative and younger HCWs are more open minded for the idea of new challenges like influenza-vaccination. In contrast, other studies showed lower vaccination adherence in HCWs aged <35 years.Citation17

In this study self-protection as well as protection of family against infection emerged as the most common reason for vaccination. On the other hand to protect patients was reported as a reason by only 1.7% of the HCWs. However HCWs are expected to be highly motivated to protect their patients, however that was the least common reason for vaccination. Likewise, other studies on attitudes and predictors of HCWs vaccination concluded that HCWs get vaccinated primarily for their own health benefit and not for the benefit of their patients.Citation18 This may be due to the fact that HCWs do not see themselves as a risk factor for patients. This is an incorrect judgment because many studies showed that influenza outbreak in hospitals can cause considerable morbidity in high risk groups like neonates and oncology patients. Reports have shown that the major source of influenza infection in patients were due to staff members, thus increased influenza vaccination coverage among healthcare workers could reduce the risk of influenza and influenza like illness in patients.Citation19,Citation20

This study revealed that HCWs had inadequate knowledge about the influenza vaccine. Most of the HCWs stated that influenza vaccine was unnecessary and ineffective. Previously, studies also showed low perceived vaccine efficacy and a low perceived risk of influenza infection.Citation18,Citation21 Therefore the perception of ineffectiveness and unnecessity of influenza vaccine are considered as the main handicap to increase vaccination uptake. If there was an established system in Turkey to show the effectiveness of vaccination, it would be easier to persuade HCWs to get vaccinated. The European Center for Disease Control (ECDC) has funded a project on monitoring of influenza vaccine effectiveness (I-MOVE). Since 2008–2009 influenza season, I-MOVE has provided estimates of vaccine effectiveness using standardized protocols with different methods.Citation22 Different studies regarding vaccine effectiveness found that influenza vaccination helps in good protection of adults and children against hospitalization for influenza.Citation23-Citation25

One of the frequent reasons for non-vaccination came out to be having a bad experience with previously influenza vaccination however our onsite vaccination campaign could not cope with this barrier. People facing bad experiences might have flu symptoms even after they have been vaccinated against influenza. One reason regarding this situation is that people can become ill from other respiratory viruses besides influenza such as rhinoviruses, which are associated with the common cold, cause symptoms similar to influenza, and also spread and cause illness during the flu season. However influenza vaccination only protects against flu, not other illnesses. Second reason is that it is possible to be exposed to influenza viruses, which cause the flu, shortly before getting vaccinated or during the two-week period after vaccination that it takes the body to develop immune protection. This exposure may result in a person becoming ill with flu before protection from the vaccine takes effect.Citation26 Therefore we have to develop some educational strategies to overcome this “bad experience” barrier.

Another barrier for vaccination in this study was pregnancy. Twelve participants rejected vaccination because of pregnancy. In this regard among HCWs pregnancy is incorrectly known as a contraindication for vaccination. Since pregnant women have increased risk of severe disease, complications and death from influenza, vaccination is recommended at any time during pregnancy, before and during the influenza season by ACIP.Citation27 Although the Turkish ministry of health recommends influenza vaccine for pregnant women free of charge, we noticed that HCWs were unaware of these promotions and recommendations. Therefore education about maternal vaccination and recommendations may increase influenza vaccination coverage during pregnancy among HCWs.

Previous studies reported that negative propaganda of the media about vaccination is one of the important reasons underlying the failure of vaccination campaigns.Citation28,Citation29 We conducted this study at the beginning of the season before incorrect news about influenza vaccination was reported.

Our study has some limitations. First, instead of multiple-choice questionnaire, we only used an open ended questions for information regarding the reason of vaccination and non-vaccination. Multiple-choice questionnaires would give us more information about beliefs and attitudes of HCWs about influenza vaccination. However multiple-choice questionnaire takes more time to fulfill, which could lead to lower response rates. As a second limitation, this study was designed as a pre-post single group intervention program and we did not have a control group for further evaluating the effects of intervention. Due to ethical issues we could not form a control group because they would be deprived of the chance of vaccination uptake. Nevertheless our study had the ability to include the views from a wide range of pediatric healthcare professionals and had a high response rate.

Conclusion

Onsite vaccination intervention is significantly associated with increased influenza vaccination coverage among HCWs but it seems insufficient alone. In order to achieve target vaccination coverage, we should break down the prejudices with comprehensive education programs.

Methods

Study sample

The survey was carried out in a tertiary children hospital located in Ankara, Turkey at the beginning of 2017–2018 influenza season. The hospital had total of 798 employees. One hundred ninety one subjects (23.9%) were excluded because their employment was less than 2 years. Thus, a total of 607 (76%) were eligible for the interventional study but only 572 participants could be reached. Health care workers (HCWs) were categorized in 3 groups: (1) physicians, (2) nurses/midwives/paramedics, and (3) nonclinical support staff (administrative support staff/, housekeeping and foodservice staff, medical secretaries and other nonclinical support)

Study design

The study is designed as pre-post single-group intervention that implemented and evaluated onsite vaccination intervention program in one observation season. The 2016–17 season was used as a control group. Special attention was paid for providing that the data in the pre-assessment and post-assessment are matched meaning that the groups in 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 consists of exactly the same people.

Intervention

Influenza vaccination is free for all employees in the hospital. Each year at the beginning of the influenza season an announcement is made that a free influenza vaccine is available in the hospital. This season we constituted three mobile vaccination teams that include a doctor and a nurse. The vaccination team visited all participants and collected information about previous vaccination uptake, attitudes and beliefs of HCWs by means of an anonymous questionnaire. Moreover, the influenza vaccine was offered onsite to all participants.

Questionnaire

An anonymous questionnaire was adapted from previous relevant literature and included questions about why HCWs decided to have the influenza vaccination or reasons why they declined the vaccine in 2017–2018 and 2016–2017 influenza season. We used open – ended question to get information about vaccine-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviors among HCWs. After the collection, open ended answers about reasons for vaccination and non-vaccination were categorized. Occupation, age, sex, self-reported vaccination status of previous year was also gathered.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,USA). Data are expressed as numbers and percentages or mean ± standard deviation (SD), as appropriate. Normal distributions were determined via the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, histograms, and p-p plots. Depending on the normality of the data, numeric variables were compared with an independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. All categorical variables were compared using the Pearson chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test.

In order to figure out the statistical significance of the numerical changes regarding vaccination status of participating HCWs we have employed McNemar’s test on the data. P values smaller than 0.05 are considered as statistically significant.

Multivariate regression analyses were performed to evaluate the role of some explaining factors in determining the vaccination uptake status (vaccinated or not) in 2017–2018 season with odds ratio. Age, profession, sex and vaccination status at baseline came out to be the independent factors affecting the vaccination status in 2017–2018 season.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by local Ethics Committee of Sami Ulus Hospital and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ortiz JR, Hombach J. Announcing the publication of the WHO immunological basis for immunization series module on influenza vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36(37):5504–05. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.010.

- Maltezou HC, Poland GA. Immunization of health-care providers: necessity and public health policies. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4(3):E47. doi:10.3390/healthcare4030047.

- Polat HH, Yalçin AN, Öncel S; Influenza vaccination. Rates, knowledge and the attitudes of physicians in a university hospital. Turkiye Klin J Med Sci. 2010;30:48–53. doi:10.5336/medsci.2008-8117.

- Mistik S, Balci E, Elmali F. Primary healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude and behavior regarding influenza immunization; 2006–2007 season adverse effect profile. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2012;113:384–88.

- Savas E, Tanriverdi D. Knowledge, attitudes and anxiety towards influenza A/H1N1 vaccination of healthcare workers in Turkey. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:281. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-281.

- Caban-Martinez AJ, Lee DJ, Davila EP, LeBlanc WG, Arheart KL, McCollister KE, Christ SL, Clarke T, Fleming LE. Sustained low influenza vaccination rates in US healthcare workers. Prev Med. 2010;50(4):210–12. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.01.001.

- Hollmeyer H, Hayden F, Mounts A, Buchholz U. Review: interventions to increase influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in hospitals. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(4):604–21. doi:10.1111/irv.12002.

- Torun SD, Torun F. Vaccination against pandemic influenza A/H1N1 among healthcare workers and reasons for refusing vaccination in Istanbul in last pandemic alert phase. Vaccine. 2010;28(35):5703–10. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.049.

- Sevencan F, Ertem M, Özçullu N, Dorman V, Kubat NK. The evaluation of the opinions and attitudes of healthcare personnel of the province Diyarbakir against influenza A (H1N1) and the vaccination. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(9):945–51. doi:10.4161/hv.7.9.16368.

- Black CL, Xin Yue MPS, Ball SW, Fink R, de Perio MA, Laney AS, Williams WW, Lindley MC, Graitcer SB, Lu PJ, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel - United States, 2016–17 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(38):1009–15. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6638a1.

- Ozisik L, Tanriover MD, Altınel S, Unal S. Vaccinating healthcare workers: levelof implementation, barriers and proposal for evidence-based policies in Turkey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(5):1198–206. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1269992.

- Yue X, Black C, Ball S, Donahue S, De Perio MA, Laney AS, Greby S. Workplace interventions associated with influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel in ambulatory care settings during the 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 influenza seasons. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(11):1243–48. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2017.05.016.

- Song JY, Park CW, Jeong HW, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ, Kim SR. Effect of a hospital campaign for influenza vaccination of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:612–17. doi:10.1086/504503.

- Riphagen-Dalhuisen J, Gefenaite G, Hak E. Predictors of seasonal influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in hospitals: a descriptive meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2012;69(4):230–35. doi:10.1136/oemed-2011-100134.

- Giannattasio A, Mariano M, Romano R, Chiatto F, Liguoro I, Borgia G, Guarino A, Lo Vecchio A. Sustained low influenza vaccination in health care workers after H1N1 pandemic: a cross sectional study in an Italian health care setting for at-risk patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2015 Aug 12;15:329. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1090-x.

- Çiftci F, Şen E, Demir N, Çiftci O, Erol S, Kayacan O. Beliefs, attitudes, and activities of healthcare personnel about influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018 Jan 2;14(1):111–17. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1387703.

- Hollmeyer HG, Hayden F, Poland G, Buchholz U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals–a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine. 2009;27(30):3935–44. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.056.

- Nutman A, Yoeli N. Influenza vaccination motivators among healthcare personnel in a large acute care hospital in Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2016;5:52. doi:10.1186/s13584-016-0112-5.

- Dionne B, Brett M, Culbreath K, Mercier RC. Potential ceiling effect of healthcare worker influenza vaccination on the incidence of nosocomial influenza infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(7):840–44. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.77.

- Amodio E, Restivo V, Firenze A, Mammina C, Tramuto F, Vitale F. Can influenza vaccination coverage among healthcare workers influence the risk of nosocomial influenza-like illness in hospitalized patients? J Hosp Infect. 2014;86(3):182–87. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2014.01.005.

- Naleway AL, Henkle EM, Ball S, Bozeman S, Gaglani MJ, Kennedy ED, Thompson MG. Barriers and facilitators to influenza vaccination and vaccine coverage in a cohort of health care personnel. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(4):371–75. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.11.003.

- Rizzo C, Rezza G, Ricciardi W. Strategies in recommending influenza vaccination in Europe and US. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(3):693–98. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1367463.

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Di Pietrantonj C, Ferroni E, Thorning S, Thomas RE, Rivetti A. Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD004876. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004876.pub4.

- Chiu SS, Kwan MYW, Feng S, Wong JSC, Leung CW, Chan ELY, Peiris JSM, Cowling BJ. Interim estimate of influenza vaccine effectiveness in hospitalised children, Hong Kong, 2017/18. Euro Surveill. 2018;23(8). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.8.18-00062.

- Castilla J, Navascués A, Casado I, Pérez-García A, Aguinaga A, Ezpeleta G, Pozo F, Ezpeleta C, Martínez-Baz I; Primary Health Care Sentinel Network; Network For Influenza Surveillance In Hospitals Of Navarre. Interim effectiveness of trivalent influenza vaccine in a season dominated by lineage mismatched influenza B, northern Spain, 2017/18. Euro Surveill. 2018;23(7). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.7.18-00057.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD). Misconceptions about seasonal flu and flu vaccines; 2018 Sep 25. [accessed 2018 Dec 5] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/misconceptions.htm.

- Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB, Bresee JS, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices-United States, 2017-18 influenza season. Am J Transplant. 2017 Nov;17(11):2970–82. doi:10.1111/ajt.14511.

- Nougairède A, Lagier JC, Ninove L, Sartor C, Badiaga S, Botelho E, Brouqui P, Zandotti C, De Lamballerie X, La Scola B, et al. Likely correlation between sources of information and acceptability of A/H1N1 swine-origin influenza virus vaccine in Marseille, France. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11292. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011292.

- Arda B, Durusoy R, Yamazhan T, Sipahi OR, Taşbakan M, Pullukçu H, Erdem E, Ulusoy S. Did the pandemic have an impact on influenza vaccination attitude? A survey among health care workers. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:87. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-87.