ABSTRACT

Background: Achieving optimal human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake can be delayed by parents’ HPV vaccine hesitancy, which is as a multi-stage intention process rather than a dichotomous (vaccinated/not vaccinated) outcome. Our objective was to longitudinally explore HPV related attitudes, beliefs and knowledge and to estimate the effect of psychosocial factors on HPV vaccine acceptability in HPV vaccine hesitant parents of boys and girls.

Methods: We used an online survey to collect data from a nationally representative sample of Canadian parents of 9–16 years old boys and girls in September 2016 and July 2017. Informed by the Precaution Adoption Process Model, we categorized HPV vaccine hesitant parents into unengaged/undecided and decided not. Measures included sociodemographics, health behaviors and validated scales for HPV and HPV vaccine related attitudes, beliefs and knowledge. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability were assessed with binomial logistic regression.

Results: Parents of boys and girls categorized as “flexible” hesitant (i.e., unengaged/undecided) changed over time their HPV related attitudes, behaviors, knowledge and intentions to vaccinate compared to “rigid” hesitant (i.e., decided not) who remained largely unchanged. In “flexible” hesitant, greater social influence to vaccinate (e.g., from family), increased HPV knowledge, higher family income, white ethnicity and lower perception of harms (e.g., vaccine safety), were associated with higher HPV vaccine acceptability.

Conclusions: HPV vaccine hesitant parents are not a homogenous group. We have identified significant predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability in “flexible” hesitant parents. Further research is needed to estimate associations between psychosocial factors and vaccine acceptability in “rigid” hesitant parents.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are considered a “game changer” in cancer prevention in both women and men.Footnote1 HPV vaccines are highly effective in reducing high-risk HPV (e.g., 16 and 18) infection prevalence and offer protection against cervical, vaginal, vulvar, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers.Citation2 Worldwide, over 270 million doses of HPV vaccines have been distributed and the Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety of the WHO considers the HPV vaccine extremely safe.Citation2 Globally, 95 countries have implemented or will implement national HPV vaccination programs (mostly for females) by the end of 2018.Citation3,Citation4 HPV immunization is recommended before the onset of sexual activity–to develop immunity before the first exposure to the virus–and comprises 2 or 3 doses for those aged 9–14 and >15 (or immunocompromised) respectively.Citation2

Worldwide, completion of the recommended HPV vaccine uptake in females aged 10–20 years is very low (6.1%) and great disparities in uptake exist between countries of high income (32.1%) and low and medium income (0.1–7.2%).Citation3 Geographically, best full-course HPV vaccination coverage in females aged 10–20 years has been achieved in Oceania (notably in Australia), Northern America, and Europe (35.9%, 36.6% and 31.1% respectively). Latin America and the Caribbean (19.0%) and especially Africa (1.2%) and Asia (1.1%) significantly lag behind.Citation3 In Canada, all 10 provinces and 3 territories have implemented gender-neutral, publicly funded, school-based HPV vaccination programs.Citation5 Full-course HPV vaccine uptake in girls and boys in Canada continues to be sub-optimal, as only 3 provinces report uptake rates >80% (Newfoundland & Labrador–89.2% in girls–, Prince Edward Island–82.7% in girls and 81.4% in boys–and Nova Scotia–84.9% in boys–).Citation6-Citation8

Despite existing national school-based programs, HPV vaccine uptake can be jeopardized by parents’ hesitancy towards HPV vaccination for their children. As an example, in the Republic of Ireland, a group called Reactions and Effects of Gardasil Resulting in Extreme Trauma (REGRET), greatly influenced parents’ hesitancy by questioning the safety profile of the HPV vaccine.Citation9 Consequently, vaccine uptake in school-based vaccination programs for girls dropped from 72.3% in the academic year 2015/2016 to 51% one year later.Citation9,Citation10

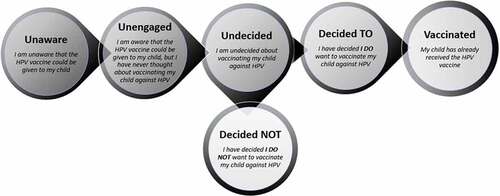

Rather than a dichotomous behavior (vaccinated/not vaccinated), the WHO SAGE Working Group describes vaccine hesitancy as a continuum refusal process and defines it as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services”.Citation11 Using a stage of change-based framework allows for a nuanced perspective on HPV vaccination intentions by examining distinct stages of vaccine intentions. The Precaution Adoption Process Model (PAPM) posits that preventive health behavior can include six nominal intention stages: 1) unaware of the health behavior; 2) unengaged in the decision; 3) undecided; 4) decided not to act; 5) decided to act (intending); and 6) acting (vaccinated).Citation12

Informed by PAPM to measure HPV vaccination intentions in parents of girls and boys, Perez et al. (2017) and Shapiro et al. (2018) found strong associations in cross-sectional studies between parents’ who decided not to vaccinate and perceived benefits of HPV vaccination, cues to action (e.g., recommendation of a healthcare provider (HCP)), harms (e.g., adverse effects related to the vaccine) and perceived susceptibility to HPV infection.Citation13,Citation14 In unengaged or undecided parents, these associations were more inconsistent, suggesting that decided not vaccine hesitant parents have more fixed attitudes and beliefs related to HPV vaccination compared to parents who were unengaged or undecided.Citation13,Citation14 Importantly, Shapiro et al. (2018) found that HPV vaccination policy (i.e., availability of publicly funded school-based vaccination program) has little influence on the decided not (~9% of parents of boys and in parents of girls reported being in this stage) compared to unengaged or undecided hesitant parents (~38% in parents of boys and ~20% in parents of girls for which all jurisdictions had implemented school-based vaccination programs).Citation14 These results suggest that HPV vaccine hesitant parents do not represent a homogenous group and that latent differences between unengaged/undecided and decided not parents exist.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore longitudinally knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and intentions related to the HPV vaccine among hesitant parents (objective 1) and to estimate the associations between psychosocial factors (i.e., socio-demographics, attitudes and beliefs) and HPV vaccine intentions in HPV vaccine hesitant parents of boys and girls (objective 2). The goal of this study is to understand better the intricacies of the vaccine hesitancy concept that might lead to more effective targeted interventions.

Results

After data cleaning, our final samples at Time 1 and Time 2 were 3,604 and 1,758 respectively. In parents of girls, 175 parents were unengaged/undecided and 85 were decided not and provided valid answers at both time-points. We included in the analyses 322 and 84 unengaged/undecided and decided not parents of boys respectively.

Psychosocial correlates of unengaged/undecided and decided not stages

At baseline (Time 1), in both parents of girls and boys, those who were unengaged/undecided (compared with decided not) perceived higher susceptibility and severity of HPV infections, more benefits of the HPV vaccine, higher social influence and considered HPV vaccine affordability and accessibility an issue (). Conversely, parents who were decided not had higher HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge, reported more harms associated with the HPV vaccine, higher conspiracy and hesitancy beliefs and perceived themselves more competent to make health-related decisions for their child (). In parents of girls, more decided not parents received an HPV vaccine recommendation from a HCP and the mean age of their daughter was one year older than in unengaged/undecided parents. In parents of boys, unengaged/undecided had higher income than decided not parents and a higher proportion reported having two or more children. (See ).

Table 1. Comparison of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of hesitant (unengaged/undecided versus decided not) parents of girls and parents of boys at Time 1.

Change of HPV vaccine intention stage over time

From Time 1 to Time 2, 17.7% and 24% of unengaged/undecided parents of girls changed to decided to and vaccinated respectively, while in parents decided not at Time 1, 7.1% and 2.3% changed to decided to and vaccinated respectively (). More decided not parents of girls at Time 1 did not change their intention stage and remained decided not at Time 2 (70.6%), compared to 44% of unengaged/undecided who remained unengaged/undecided over time (CI: 0.14; 0.39) (). In parents of boys, over time, 19.6% and 9.9% of those unengaged/undecided changed to decided to and vaccinated respectively while in parents decided not at Time 1, 0% and 1.2% changed to decided to and vaccinated respectively (). As in parents of girls, more decided not parents of boys at Time 1 did not change their intention stage and remained decided not at Time 2 (70.2%), compared to 59.6% of unengaged/undecided who remained unengaged/undecided over time (CI: −0.005; 0.22) ().

Table 2. Changes in PAPM stages of hesitant (unengaged/undecided and decided not) parents of girls and parents of boys from Time 1 to Time 2.

Change of attitudes and behaviors over time

In parents of boys and parents of girls who changed over time from unengaged/undecided to decided to or vaccinated, we found (at Time 2) significantly increased HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge, increased risks related to the HPV infection, increased benefits of HPV vaccination, increased social influence and self- efficacy and decreased attitudes related to HPV vaccine associated harms, affordability and accessibility as well as decreased vaccine conspiracy and hesitancy beliefs (). In contrast, in parents of boys and parents of girls who did not change their intention stage over time (i.e., unengaged/undecided or decided not at Time 1 and Time 2), knowledge and attitudes and beliefs remained largely unchanged ().

Table 3. Change of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs in Unengaged/Undecided parents at Time 1 who changed to Decided To or Vaccinated at Time 2.

Psychosocial predictors of HPV vaccine intentions

In bivariate analyses of both parents of girls and parents of boys, perception of increased risk of HPV infection, increased benefits of HPV vaccination, higher social influence, self-efficacy related to HPV vaccination and receiving recommendation to vaccinate their child from a HCP were associated with increased odds of vaccine acceptability (i.e., decided to and vaccinated) (). In contrast, worries related to affordability and accessibility, increased beliefs related to HPV vaccine harms and increased vaccine conspiracy and vaccine hesitancy beliefs were associated with decreased odds of HPV vaccine acceptability (). Parents of girls reporting an annual family income ≥100,000 Canadian dollars had lower vaccine acceptability compared to those earning <100,000 Canadian dollars ().

Table 4. Bivariate logistic regression analysis for boys and girls at Time 2 for decided to/vaccinated versus unengaged/undecided/decided not (reference category).

In multivariate analysis of unengaged/undecided hesitant parents (Time 1) who changed to vaccine acceptors (decided to/vaccinated) or remained hesitant (unengaged/undecided or decided not) at Time 2, higher social influence (e.g., family, friends, HCPs) was associated with increased odds of vaccine acceptability in parents of girls (OR = 2.91, CI: 1.50; 5.65) and parents of boys (OR = 2.89, CI: 1.77; 4.74). Increased beliefs related to HPV vaccine harms (e.g., vaccine is unsafe, insufficient research done) was associated with decreased odds of vaccine acceptability in parents of girls (OR = 0.47, CI: 0.25; 0.88) and parents of boys (OR = 0.63, CI: 0.40; 1.01). In parents of girls, for one unit increase in HPV knowledge we found 21% increased odds of vaccine acceptability (OR = 1.21, CI: 1.05; 1.39). In parents of boys, being white (compared to other ethnicities) was associated with lower odds of HPV vaccine acceptability (OR = 0.39, CI: 0.17; 0.90) (). Parents of girls earning ≥100,000 Canadian dollars had lower odds of accepting the HPV vaccine (OR = 0.36, CI: 0.13; 0.99) ().

Table 5. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for boys and girls at Time 2 for decided to/vaccinated versus unengaged/undecided/decided not (reference category).

Discussion

Informed by PAPM, HPV vaccine hesitant parents (i.e., those who have not vaccinated their child against HPV) were categorized into unengaged (i.e., have not thought about vaccinating their child), undecided (about vaccinating their child against HPV), and parents who decided not to vaccinate (). This categorization is consistent with the WHO SAGE definition of vaccine hesitancy as a multifaceted rather than a dichotomous (i.e., vaccinated/not vaccinated) decision. PAPM facilitates a better understanding of vaccine hesitancy by excluding parents who are not even aware that the HPV vaccine can be given to their child. Previous research has shown that in the absence (or incipient stages) of an HPV vaccination program for boys, the unaware group accounts for 28–58% of a randomly selected sample of parentsCitation13,Citation14 and have significantly lower HPV knowledge compared to unengaged, undecided and decided not hesitant parents.Citation14

To better understand the longitudinal decision of vaccine hesitant parents we dichotomized vaccine hesitant parents–in parents of boys and girls–as two distinct entities: “flexible” hesitant–corresponding to vaccine intention stages unengaged/undecided–and “rigid” hesitant, corresponding to the intention stage decided not. We suggest these two entities based on existing differences between “flexible” and “rigid” hesitant parents related to their intentions to give the HPV vaccine to their children and differences in parents’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to the HPV vaccine. This study found that significantly more “flexible” hesitant parents changed to HPV vaccine acceptors over time, compared to “rigid” hesitant who remained unchanged. Moreover, we found an important change from Time 1 to Time 2 in HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge and attitudes and beliefs (e.g., increased benefits of HPV vaccination, increased social influence, decreased harms) in “flexible” hesitant compared to “rigid” hesitant parents. In addition to the objectives of this study, we combined data from this study with data collected by Perez et al. (February 2014)Citation15 and found–on a total sample of 6,721 Canadian parents of boys and girls–that “flexible” hesitant are about 3.6 times more numerous than “rigid” hesitant (29% versus 8% respectively). Specific messaging targeting ‘flexible’ hesitant parents and designed to address their concerns (based on our results) should be integrated into educational materials that are distributed to parents at the time of implementation in either school, clinic or physician-based programs.

In “flexible” hesitant parents, we found that increased influence from family, friends and HCP related to HPV vaccination (parents of girls and parents of boys), increased HPV vaccine knowledge (parents of girls) and decreased perceptions of harms related to the HPV vaccine (parents of girls) are positively related to HPV vaccine acceptability (i.e., decided to or vaccinated). Moreover, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on a combined sample of 418 parents of girls and parents of boys at Time 1 who received a HCP recommendation related to the HPV vaccine (See ) and found that the strength of a HCP recommendation was positively associated with HPV vaccine acceptability (OR = 1.69, 95% CI; 1.21–2.36). In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Newman et al. (2018) found additional parent factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake to include perceived HPV vaccine benefits, affordability (i.e. HPV vaccine covered by insurance), and child’s age.Citation16 These differences could be explained by including in our analyses only parents who changed from “flexible” hesitant at Time 1 and by defining the outcome (i.e., decided to or vaccinated versus vaccine hesitant) informed by a multi-stage intention model (i.e., PAPM), as opposed to Newman et al. (2018) who defined their outcome binomially (vaccinated/not vaccinated).Citation16

Importantly, the natural experiment represented by the introduction of a free, school-based vaccination program for boys in Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba from Time 1 to Time 2 was not significantly associated with vaccine acceptability in “flexible” hesitant parents. In our opinion, most parents became aware of the new program (as parental consent is required for minors); however, it is possible that key aspects (e.g., vaccine safety) were not covered in the information provided to parents, or that the information provided–consistent with results published by Tulsieram et al. (2018) who analyzed the readability and coherence of seven Canadian provincial ministry of health’s HPV information websites–was not adequately tailored to the level of understanding of lay populationCitation17 . Our results show that tailored information for “flexible” hesitant parents should address the excellent safety profile of the vaccine, the need to consult a HCP and discuss with other members form the community who have vaccinated their children.

Our study is not without limitations. First, HPV vaccination status is based solely on parents’ self-reports of vaccination status as HPV vaccination registries are in various stages of implementation across Canada. We consider that by including in the definition of vaccine acceptability both actual uptake and parents’ decision to vaccinate (i.e., decided to stage), we have partially circumvented the recall bias. Second, we were limited by the small number of “rigid” hesitant parents who changed over time to decided to or vaccinated (n = 8 and n = 1 in parents of girls and parents of boys respectively) and could not conduct multivariate analyses in this group of hesitant parents. Third, the applicability of our results could have been affected by an important attrition rate. Nevertheless, the negligible effect size of the differences in sociodemographics, knowledge, attitudes and beliefs between parents who responded at Time 2 and those who were lost to follow-up indicate that the two groups were almost identical in respect to the variables analyzed (See and ). Lastly, our study was conducted in a high-income country with a well-developed healthcare system and efficient vaccination programs, making our results likely less generalizable to low or medium income countries and different healthcare systems.

Methods

Data collection

We used a web survey and a cross-sectional design to collect data from a national representative sample of Canadian parents of 9–16 years old boys and girls. Details of the study methodology are presented in detail elsewhere.Citation18 Briefly, parents were recruited by Canada’s largest market research and polling firm, Leger–The Research Intelligence Group–from its national panel of over 400 000 members which is built to be nationally and regionally representative with respect to gender, age, education level, household composition and income. Collecting data from a representative sample of Canadian parents was ensured by using Leger’s proprietary software–designed in concordance to Canada’s census data–to generate the initial sample pool and continuously adjust the composition of the target groups during the recruitment process. Data collection was performed from August-September 2016 (Time 1) and parents who participated at Time 1 were invited to participate in June-July 2017 (Time 2). At Time 1, all Canadian jurisdictions and 3 provinces (Alberta, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island) had in place publicly, school-based vaccination programs for girls and boys respectively. Between Time 1 and Time 2, three provinces (Ontario, Manitoba and Quebec) initiated free, school-based HPV vaccination programs for boys. The study received approval by the Integrated Health and Social Services University Network for West-Central Montreal (CODIM-FLP-16–219).

Measures

We used the PAPM to situate parents’ stage of intention to vaccinate their [child] with the HPV vaccine.Citation12 Informed by PAPM, parents selected one of 6 response options: “I was unaware that the HPV vaccine could be given to [child]” (stage 1, unaware), “I have never thought about vaccinating [child] against HPV” (stage 2, unengaged), “I am undecided about vaccinating [child] against HPV” (stage 3, undecided), “I have decided I do not want to vaccinate [child] against HPV” (stage 4, decided not), “I have decided I do want to vaccinate [child] against HPV” (stage 5, decided to) and “[child] has already received the HPV vaccine” (stage 6, vaccinated). Parents who were unengaged, undecided or decided not to vaccinate, were considered HPV vaccine hesitant. As opposed to measuring intentions dichotomously (vaccinated/not vaccinated), the PAPM allows for HPV vaccine hesitancy to be defined more precisely, by excluding parents who were unaware of the HPV vaccine (as these parents did not have the opportunity to make an informed decision) and parents who had decided to vaccinate (and were obviously no longer hesitant) ().

Correlates of parents’ HPV vaccine hesitancy included HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge, attitudes and beliefs1 related to the HPV vaccine, sociodemographics, HPV vaccination policy and behaviors. HPV knowledge and HPV vaccine knowledge were measured with validated scales; the HPV knowledge scale had an internal consistency of α = 0.90 (23 items, e.g., “HPV can be passed on during sexual intercourse”) and HPV Vaccine knowledge scale of α = 0.78 (11 items, e.g., “The HPV vaccines offer protection against all sexually transmitted infections”).Citation19 Total knowledge scores were calculated by assigning 1 point to correct answers and zero points for incorrect or ‘Don’t know’ answers. We used the validated HPV Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (HABS)Citation20 to measure the following constructs: susceptibility (risk) (3 items, α = 0.92, e.g., “Without the HPV vaccine, my [child] would be at risk of getting HPV later in life), severity (threat) of HPV infection and associated diseases (3 items, α = 0.84, e.g., “It would be serious if my [child] contracted HPV later in life”), benefits of HPV vaccination (10 items, α = ,0.94 e.g., “The HPV vaccine is effective in preventing HPV”), affordability (3 items, α = ,0.87 e.g., “The HPV vaccine costs more than I can afford”), accessibility (4 items, α = 0.79, e.g., “Dealing with getting the HPV vaccine for my [child] would be simple”), harms related to the HPV vaccine (6 items, α = 0.93, e.g., “The HPV vaccine is unsafe”) and social influence (8 items, α = 0.91, e.g., “Other parents in my community are getting their [child] the HPV vaccine”). Self-efficacy was measured with 4 items (α = 0.89 e.g., “I am competent to make decisions about the vaccines [child] receives”. We measured vaccine conspiracy with the Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs Scale (VCBS) (7 items, α = 0.95, e.g., “Vaccine safety data is often fabricated.”)Citation21 and vaccine hesitancy by using the Vaccine Hesitancy scale (VHS) which consists of two subscales: confidence (7 items, α = 0.92, e.g., “Childhood vaccines are important for my child’s health”) and risks (7 items, α = 0.64, e.g., “New vaccines carry more risks than older vaccines”).Citation22 Vaccine attitudes were measured on a seven-point Likert-type rating scales ranging from ‘1-strongly disagree’ to ‘7-strongly agree’ and average scores for each sub-scale were calculated.

Sociodemographics included continuous variables (i.e., parent’s and child’s age) and categorical variables (i.e., education, number of children, parent’s gender, income and ethnicity). HPV vaccine policy change encompass provinces who implemented free HPV vaccination programs for boys from Time 1 to Time 2 (i.e., Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba) versus provinces with no change in policy. Health behaviors comprise a binomial variable i.e., receiving versus not receiving a HPV vaccine recommendation from a healthcare provider (HCP).

Data analysis

We used statistical data cleaning methods (i.e., psychometric synonyms and bogus items) to flag inattentive or unmotivated responders.Citation18 Responders flagged at either Time 1 or Time 2 were excluded from the analyses.

Informed by PAPM, we dichotomized hesitant parents into: unengaged/undecided and decided not as we consider that both unengaged and undecided parents have not formed a definitive intention (i.e., they are in more initial stages of decision-making) as opposed to parents who have clearly decided not to give the HPV vaccine to their child. We conducted analyses separately for parents of boys and parents of girls and for each group of hesitant parents separately and included only parents who provided responses at both Time 1 and Time 2.

Consistent with objective 1 we explored 1) differences in psychosocial correlates between unengaged/undecided and decided not at Time 1, 2) the change of HPV vaccine intention stage from Time 1 to Time 2 for the two groups of hesitant parents and 3) the change of attitudes and behaviors over time for each group of hesitant parents. For categorical variables, we used two-sample test of proportions and reported 95% confidence intervals (CI) to highlight significant differences. For continuous variables (e.g., attitudes, knowledge) we used the Welch two sample t-test and reported the 95% CI for differences in means.

To estimate the effect of psychosocial predictors (i.e., socio-demographics, attitudes and beliefs) on HPV vaccine intentions in HPV vaccine hesitant parents of boys and girls (objective 2), we included only parents who were unengaged or undecided at Time 1 and used binomial logistic regression to analyze the Time 2 data. The outcome variable included two categories of parents: acceptors of the HPV vaccine (i.e., decided to or vaccinated) and HPV vaccine hesitant (unengaged/undecided or decided not). For nominal predictors, we report the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI of accepting the HPV vaccine (versus HPV vaccine hesitant) for each category versus the reference category (e.g., female versus male). For continuous predictors (e.g., attitudes), we report the change (OR) and 95% CI represented by a one-unit score increase. First, we conducted bivariate analyses between each predictor and the outcome. Then, we ran the multivariate model (final model) with predictors significantly associated with the outcome in bivariate analyses and predictor variables of interest i.e., policy change, ethnicity.Citation14 We used following logistic regression model diagnostic criteria1: Rank Discrimination Index C where C = 0.5 indicates random guessing and C = 1 perfect discrimination 2) Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) with a cut-off value of <10 to flag multicollinearityCitation23 and 3) Cessie–van Houwelingen goodness-of-fit test whereby p > 0.05 suggests no evidence to reject a good fit.Citation24 We calculated the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)Citation25 for the regression model including all variables and the final model and retained the model with the lowest BIC value. Analyses were performed with R 3.4.3 for Windows.

Conclusion

In a Canadian sample of parents of 9–16-year-old boys and girls, we have shown that HPV vaccine hesitancy is not a homogenous entity and consists of those that are “flexible” hesitant who are more likely to later accept HPV vaccination, and those that are “rigid” hesitant, who tend to remain unchanged over time. Different interventions are needed for these two groups. For HPV vaccine “flexible” hesitant parents, interventions should target existing barriers of HPV acceptability such as increased beliefs of harms related to HPV vaccine, poor communication with friends, family and healthcare providers about HPV vaccination and low HPV knowledge. Future research is needed to evaluate the effect of psychosocial factors on HPV vaccine acceptability in “rigid” hesitant parents, and what interventions are most appropriate for this group.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) for all included scales was calculated at Time 1, n = 3604.

References

- Canadian Cancer Society. A game changer. Believe 2013; 2013 Spring/Summer [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. http://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/AB/about%20us/BelieveMagazine_2013_Spring_AB.pdf?la=en.

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, May 2017; 2017 May 12 [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255353/WER9219.pdf?sequence=1.

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Herrero R, Bray F, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Castellsagué X. Global estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage by region and income level: a pooled analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(7):e453–e463. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(16)30099-7.

- World Health Organization. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. 2018 global summary; 2018 Sep 21 [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/schedules.

- Government of Canada. Canada’s provincial and territorial routine (and catch-up) vaccination routine schedule programs for infants and children; 2018 Aug [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/provincial-territorial-immunization-information/provincial-territorial-routine-vaccination-programs-infants-children.html.

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Health and Community Services. Communicable disease report: quarterly report 2015–2016; 2015 Dec [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. http://www.health.gov.nl.ca/health/publichealth/cdc/pdf/CDR_Dec_2015_Vol_32.pdf.

- Government of Prince Edward Island. Health for all islanders: promote, prevent, protect; PEI chief public health officer’s report 2016: health PEI; 2016 [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/publications/cphorpt16_linkd.pdf.

- Government of Nova Scotia. School-based immunization coverage in Nova Scotia: 2016-2017; 2018 Aug 13 [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. https://novascotia.ca/DHW/POpulationhealth/documents/School-Based-Immunization-Coverage-Nova-Scotia-2016-2017.pdf.

- Paul Cullen. The HPV propaganda battle: the other side finally fights back. The Irish Times; 2017 Sep 16 [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/the-hpv-propaganda-battle-the-other-side-finally-fights-back-1.3221166.

- Health Protection Surveillance Centre. HPV vaccine uptake in Ireland: 2016/2017; 2018 Sep 1 [ accessed 2019 Jan 7]. https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/vaccinepreventable/vaccination/immunisationuptakestatistics/hpvimmunisationuptakestatistics/HPV%20Uptake%20Academic%20Year%202016%202017%20v1.1%2009012018.pdf.

- MacDonald NE, Sage Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–64. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Weinstein ND, Sandman PM, Blalock SJ. The precaution adoption process model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2008. p. 123–48.

- Perez S, Tatar O, Gilca V, Shapiro GK, Ogilvie G, Guichon J, Naz A, Rosberger Z. Untangling the psychosocial predictors of HPV vaccination decision-making among parents of boys. Vaccine. 2017;35(36):4713–21. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.043.

- Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Amsel R, Prue G, Zimet GD, Knauper B, Rosberger Z. Using an integrated conceptual framework to investigate parents’ HPV vaccine decision for their daughters and sons. Prev Med. 2018;116:203–10. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.09.017.

- Perez S, Tatar O, Shapiro GK, Dube E, Ogilvie G, Guichon J, Gilca V, Rosberger Z. Psychosocial determinants of parental human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine decision-making for sons: methodological challenges and initial results of a pan-Canadian longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1223. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3828-9.

- Newman PA, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Baiden P, Tepjan S, Rubincam C, Doukas N, Asey F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019206. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206.

- Tulsieram KL, Arocha JF, Lee J. Readability and coherence of department/ministry of health HPV information. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(1):147–53. doi:10.1007/s13187-016-1082-6.

- Shapiro GK, Perez S, Naz A, Tatar O, Guichon JR, Amsel R, Zimet GD, Rosberger Z. Investigating Canadian parents’ HPV vaccine knowledge, attitudes and behaviour: a study protocol for a longitudinal national online survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017814. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017814.

- Perez S, Tatar O, Ostini R, Shapiro GK, Waller J, Zimet G, Rosberger Z. Extending and validating a human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge measure in a national sample of Canadian parents of boys. Prev Med. 2016;91:43–49. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.07.017.

- Perez S, Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Joyal-Desmarais K, Rosberger Z. Development and validation of the human papillomavirus attitudes and beliefs scale in a National Canadian sample. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(10):626–32. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000506.

- Shapiro GK, Holding A, Perez S, Amsel R, Rosberger Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Res. 2016;2:167–72. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2016.09.001.

- Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Dube E, Amsel R, Knauper B, Naz A, Perez S, Rosberger Z. The vaccine hesitancy scale: psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine. 2018;36(5):660–67. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.043.

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate data analysis. New York (NY): Macmillan; 1995.

- Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, Lemeshow S. A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med. 1997;16:965–80.

- Fabozzi FJ, Focardi SM, Svetlozar TR. Model selection criterion: AIC and BIC—Appendix E. The basics of financial econometrics: tools, concepts, and asset management applications. Hoboken (NJ, USA): John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014. p. 399–403.

Appendix A.

Sociodemographics of hesitant (unengaged/undecided and decided not) parents of girls and parents of boys at Time 1

Appendix B.

Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors in Decided not and Unengaged/Undecided parents who did not change their vaccination intention stage from Time 1 to Time 2

Appendix C.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis at Time 1 for all parents who received a HCP recommendation related to the HPV vaccine (n=418). Outcome is decided to/vaccinated versus unengaged/undecided/decided NOT (reference category).

Appendix D.

Differences in sociodemographics between parents who participated at Time 2 and those who did not participate at Time 2

Appendix E.

Differences in knowledge, attitudes and beliefs between parents who participated at Time 2 and those who did not participate at Time 2