ABSTRACT

Purpose: Despite its availability for more than a decade, the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine has low uptake in Texas (49%). The objective of this study was to understand parental knowledge and attitudes about HPV and the HPV vaccine as well as child experience with the HPV vaccine among a medically underserved, economically disadvantaged population.

Methods: As part of a Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas-funded project to improve HPV vaccination rates, we surveyed parents / guardians of 4th–12th graders (ages 9–17) in the Rio Grande City Consolidated Independent School District (RGCCISD). Descriptive statistics were used to describe parents’ knowledge and attitude and children’s vaccine experience.

Results: Of the 7,055 surveys distributed, 622 (8.8%) were returned. About 84% of the respondents were female. About 57.1% of the parents /guardians had female RGCCISD students with a mean age of 11.7 ± 1.8 years. Overall, 43.9% reported receiving a healthcare provider recommendation and 32.5% had their child vaccinated. Higher percentages were reported if the respondent was female and had a female child aged ≥15 years old. Among survey respondents, 28.2% reported their child initiated the HPV vaccine and 18.8% completed the series. Barriers of uptake included work / school schedule conflicts and no healthcare provider recommendation.

Conclusions: There are still prominent gaps in parents’ and students’ complete understanding of HPV vaccination, gender preferences for vaccination, and provider recommendations. Future interventions must target men and minority populations in order to increase knowledge and awareness about HPV, the HPV vaccine, and HPV-associated cancers.

Introduction

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is an effective strategy for reducing the morbidity and mortality of HPV-associated diseases, including cervical, oropharyngeal, vulvar, vaginal, penile and anal cancer as well as anogenital warts.Citation1–Citation9 There has been increasing evidence supporting the safety and effectiveness of HPV vaccination in reducing vaccine-type HPV infections at the population level.Citation10,Citation11 The HPV vaccine provides the greatest benefit to those who receive the vaccine before they become sexually active.Citation12,Citation13 Although routine HPV vaccination has been recommended in the United States (US) since 2006 for females and 2011 for males ages 9–26 years,Citation14 disparities in knowledge and awareness about HPV and the HPV vaccine persist, and vaccination rates remain suboptimal.Citation15 The Healthy People 2020 goal is to have 80% HPV coverage among 13–15-year-olds.Citation16 In the US, HPV vaccine completion rates are low for girls and boys ages 13–17 (49.5% and 37.5%, respectively).Citation17 Raising rates to 80% would prevent 53,000 more cervical cancer cases over the lifetime of those ≤12 years.Citation18,Citation19 Texas ranks 47th in terms of up-to-date HPV vaccinations out of 50 states and the District of Columbia.Citation17

Challenges in increasing HPV vaccine uptake

Given that the HPV vaccination is recommended for preadolescent boys and girls, research has shown that parents play a pivotal role in HPV vaccine uptake.Citation20 Given that the target age group is pre-adolescence (ages 11–12), there are different challenges compared to targeting adolescents and young adults. Compared to traditional infant vaccines, there is more scrutiny of HPV vaccines in regards to age appropriateness, sexual activity, and safety concerns.Citation11 In addition to the structural and health system issues (eg, cost, insurance coverage, delivery strategies) that may contribute to low HPV vaccine coverage, the broader context of vaccine hesitancy suggests that parents’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about HPV and vaccines may have a substantial influence on the uptake.Citation11

In addition to parents, healthcare providers play a crucial role in ensuring its administration.Citation21–Citation28 It is important for healthcare providers to bundle HPV vaccines with other required vaccines, such as tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) and meningococcal vaccine (MCV4, MenB).Citation29,Citation30 They are encouraged to consistently and equally recommend HPV vaccination to parents of female and male children.Citation31–Citation33 A recent survey of Texas healthcare providers found that 94% self-reported giving a consistent recommendation of HPV vaccination to 9–12-year-old children of both sexes.Citation34

Factors associated with vaccine uptake

Factors shown to be positively associated with parents’ uptake of HPV vaccines for their children include: (1) healthcare provider – physician recommendation and parents’ trust in healthcare providers,Citation20,Citation21,Citation25,Citation26,Citation33 (2) mother as HPV vaccine decision-maker versus both parents,Citation20 (3) parents’ vaccine beliefs, attitudes, and intentions,Citation20,Citation35 (4) preventive healthcare utilization for child,Citation28 (5) insurance / cost – health insurance coverage of HPV vaccination,Citation28 (6) parents’ HPV risk history,Citation20 (7) parents’ HPV-related knowledge and awareness,Citation28 and (8) sociodemographic factors – urban versus rural location and child’s age.Citation20,Citation21,Citation25,Citation26,Citation33 For those who have chosen to not vaccinate against HPV, parents cite lack of knowledge and worry about the side effects or safety of the vaccine as the primary reasons for vaccine hesitancy.Citation20 Interventions that improve parental knowledge and awareness prior to the administration of the HPV vaccine have increased uptake immediately following the encounter.Citation24,Citation36,Citation37 The sex of the parent may also affect the choice to vaccinate. Male parents are less likely to vaccinate their daughters.Citation35,Citation38

Study background

Although HPV initiation rates have risen nationally over the last decade, Texas continues to have a 10% lower uptake than the rest of the nation and had a decrease in HPV vaccine coverage among girls ages 13–17 years old in 2016.Citation39 Since certain diseases disproportionately affect low-income, rural, and minority individuals, offering the HPV vaccine at no cost is important in medically underserved settings, such as the Rio Grande Valley (RGV).Citation9 The RGV consists of four counties bordering Mexico: Cameron, Hidalgo, Starr, and Willacy Counties. Texas counties that border Mexico have characteristics different from the state of Texas as a whole.Citation40 This region has some of the worst health and economic disparities in the nation. Residents are more likely to be Hispanic, medically underserved, less educated, and economically disadvantaged and have low health literacy. Culturally appropriate interventions and survey methods are needed to increase HPV uptake and improve efforts in engaging with this population.Citation41–Citation43

Compared to other parts of Texas and the rest of the US, the RGV has the highest cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates. Specifically, women living in the RGV have a 30% higher cervical cancer incidence and mortality rate than women living in other parts of Texas or the rest of the country.Citation44,Citation45 Since Hispanics are at higher risk for HPV-associated cancers, it is imperative that HPV vaccine coverage improves in this region.Citation46 The objective of this study was to assess parental knowledge and attitudes toward the HPV vaccination as well as parent-reported HPV vaccination rates in the Rio Grande City Consolidated Independent School District (RGCCISD) in Starr County, Texas, prior to the introduction of a school-based vaccination program. We also investigated parental / guardian gender differences that might affect intent and serve as the possible reasons for not vaccinating. Introduction of the HPV vaccine in a school-based setting provides a rare opportunity to build or strengthen school health and adolescent health.Citation11

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 7,055 surveys were distributed to 4th–12th graders. By the end of the 2017 academic year, 622 completed surveys (8.8%) were returned. Of the 622 HPV Parent Surveys collected, 84.4% of the respondents were female parents / guardians, with a mean age of 38.1 years ± 7.4 (). Most of the respondents were of Hispanic or Latino descent (83.8%), and almost half of the survey respondents were US-born (45.8%). Over half of the parent respondents had female students enrolled at RGCCISD (57.1%), with a mean age of 11.7 ± 1.8 years. A majority of the survey respondents had children aged ≤14 years old (33.3% ≤10 years old and 60.0% ages 11–14 years old). Most of the children were in either elementary school (50.5%) or middle school (44.1%).

Table 1. Summary of demographic characteristics of survey respondents and their children.

Parental knowledge, awareness, and attitudes of HPV and the HPV vaccine

provides a summary of the parent / guardian responses regarding knowledge, awareness, and attitudes of HPV and the HPV vaccine. The results are stratified by child demographics (gender and age) and respondent’s gender. Most of the parents reported having heard of HPV (86.7%) and the HPV vaccine (83.6%) (). A majority of respondents (77.3%) reported awareness that the HPV vaccine can prevent certain types of cancer and were interested in learning more about HPV (73.8%). Overall, 80.4% of respondents thought that the vaccine is good / important.

Table 2. Summary of survey results on parental knowledge, awareness, and attitudes toward HPV and the HPV vaccine by child demographics and respondent’s gender.

In the comparison of respondents with female versus male children, a higher percentage of respondents with female children than respondents with male children had heard of HPV (89.6% vs 82.8%, p-value = 0.0224) and the HPV vaccine (88.2% vs 77.5%, p-value = 0.0018) and were aware that certain types of cancers were prevented by the vaccine (80.3% vs 73.4%, p-value = 0.0007) (). When stratifying by child’s age, the percentage of respondents who responded with knowledge about HPV (p-value = 0.0395, ) and the HPV vaccine (p-value = 0.00981, ) increased with the age of the student. Compared to female parents, a lower percentage of male parents had heard of HPV (76.0% vs 88.66%, p-value = 0.0098) and the HPV vaccine (70.7% vs 86.1%, p-value = 0.0012).

Child’s experience with the HPV vaccine

provides a summary of the parent / guardian responses regarding their child’s experience with the HPV vaccine by child’s gender and age and respondent’s gender. The gender for a small percentage of survey respondents were missing (3.5%, n = 22) Overall, 43.9% reported receiving a recommendation from a healthcare provider, and 32.5% reported that their child received the HPV vaccine (). Among survey respondents who vaccinated their child, 87.1% reported HPV initiation (n = 176) and 57.9% completion (n = 117). Among respondents who received recommendations for the HPV vaccine, the highest percentage of recommendations was among respondents with children between 11 and 14 years old (52.3%) compared to those aged ≤10 and ≥15 (p-value < 0.0001) (). According to respondents who did not vaccinate their child, the two main reasons for their child not receiving the HPV vaccine were no recommendation from the child’s doctor (34.8%) and their child was too young (30.4%) (). For respondents who had children aged ≤10 years old, the most common reason for not administering the HPV vaccination was their age (41.3%, p-value ≤0.0001, ). Respondents with students ages 11–14 years reported work / school schedule conflicts as the primary reason for their children not receiving the HPV vaccine (p-value = 0.0113, ).

Table 3. Child’s vaccine history and experience with the HPV vaccine by child’s demographics and respondent’s gender.

Healthcare provider recommendation

shows a summary of the children’s HPV vaccination history for parents who received a recommendation by a healthcare professional to vaccinate their child against HPV. Overall, 32.5% of respondents reported that their child had received the HPV vaccine, and 48.1% had not vaccinated their child. Almost two-thirds (63.5%) of parents who received recommendations from a healthcare provider reported vaccinating their children against HPV. Of those who did not receive healthcare provider recommendations for the HPV vaccine, 8.2% reported vaccinating their children while 73.0% reported not vaccinating their children.

Table 4. Summary of HPV vaccination history by recommendation of healthcare provider.

Discussion

This study examined knowledge, awareness, and attitudes towards HPV and the HPV vaccine among parents / guardians of school children (4th–12th graders) as well as parent-reported HPV vaccination rates and provider recommendations. A high proportion of respondents in this study sample had heard of HPV and the HPV vaccine and thought that the HPV vaccine was good or important, which highlights the high level of public awareness and knowledge about HPV and the HPV vaccine in the RGV community. While research has shown that parents’ HPV-related knowledge and awareness are positively associated with HPV vaccination rates,Citation28 HPV vaccine initiation and completion rates in RGV remain low despite seemingly high levels of awareness and knowledge about HPV and the HPV vaccine.

Reasons for low vaccination rates

Parental vaccine beliefs, attitudes, and intentionsCitation20,Citation35 may be affecting these rates. The low HPV vaccination rates reported are reflective of the low recommendation rate by RGV healthcare providers for the HPV vaccine. Research has shown that healthcare provider / physician recommendation and parents’ trust in healthcare providers is positively associated with parents’ uptake of the HPV vaccine.Citation20,Citation21,Citation25,Citation26,Citation33 Survey respondents reported higher vaccination rates when they were recommended to get the HPV vaccine for their child by their healthcare provider compared to those who did not receive recommendations. Previous research has shown that parents who vaccinate their children are more likely to remember and report higher quality recommendations from providers, i.e., providers recommending HPV as high importance for patients at ages 11–12.Citation47 However, HPV vaccination rates in this study are relatively low even among those who did receive provider recommendations.Citation47 Less than two-thirds of respondents who received a recommendation reported vaccinating their child.

Parental hesitancy towards HPV vaccine uptake has been attributed to lack of information regarding the 2- and 3-dose series, side effects, and safety of the HPV vaccine.Citation20,Citation22,Citation37,Citation48–Citation50 In addition, recommendations for HPV vaccination may be attributed to area-based factors (eg, racial / ethnic composition, area-based socioeconomic status), social context (eg, social norms of behavior, knowledge, and risk perception), physical circumstances (eg, geographic accessibility), and economic conditions (eg, time demands, work / /school schedule, costs) in RGV.Citation51 Besides healthcare provider recommendations, the main reasons reported for not getting their child vaccinated are age (too young), child was not sexually active, safety concerns, and other reasons.Citation50

Healthcare provider recommendation

A recent study in South Carolina, a state with low HPV vaccination completion (34% for girls and 16% for boys), identified that lack of provider recommendation as a major barrier to uptake.Citation52 Similar to other studies, there were notable gender differences in how providers recommend the HPV vaccine.Citation15,Citation53,Citation54 In this study, higher percentages were reported if the respondent was female and if they had a female child aged ≥15 years old. Healthcare providers may recommend HPV vaccination less frequently to parents / guardians of male children.Citation20 While the HPV vaccine has been available for use in males since 2009 and has been recommended since 2011, the lower level of knowledge and awareness among male respondents and those with male children is reflected in the parent-reported vaccination rate. Male parents / guardians may be less likely to be educated or counseled about HPV, a sexually transmitted infection and its cancer-preventing vaccine. Although the HPV vaccine was initially heavily marketed towards women, educational interventions should target both parents of children who would benefit from this vaccine.Citation53

The survey results suggest that HPV vaccine uptake may be less attributable to a child’s gender, but rather if the healthcare provider recommended the HPV vaccine at all. The study results also suggest that the provider recommendations may be dependent on a child’s age. Healthcare providers may be less likely to discuss HPV or recommend the HPV vaccine when counseling younger patients, such as a 9-year-old presenting in the pediatric clinic with an acute ailment.Citation52 However, healthcare providers are more likely to improve uptake at recommended ages of 11–12 years old if they begin the conversations earlier with parents and students. More healthcare providers are likely to advocate the importance of the vaccine at older ages. In this study, the percentage of children reported by their parents to receive the HPV vaccine increased with age from 12.1% for those aged ≤10 to 42.9% for those aged ≥15. This gap in providing preventive care at recommended ages presents a missed opportunity for HPV education and vaccination.

Future efforts to improve HPV vaccine uptake

Although the survey of Texas healthcare practitioners reports HPV vaccination recommendations at 94%,Citation34 this percentage is much lower in this study. There was a nearly even split on whether healthcare providers had recommended or not recommended the HPV vaccine to the study sample. Similar percentages concerning healthcare provider recommendation were seen when looking at student’s gender. Less than half of respondents with female students (46.5%) and 40.5% of respondents with male students received HPV vaccination recommendations from healthcare providers. About one-third of the respondents whose child did not receive the HPV vaccine reported that they had not received a recommendation from the child’s doctor.

The efforts to improve public awareness and knowledge of HPV and HPV-related cancer are futile if providers do not provide strong recommendations for the HPV vaccine. A strategy that has improved parental approval for vaccine uptake in other studies is emphasizing how the HPV vaccine prevents HPV infection and subsequently decreases the risk of HPV-related cancers in the future.Citation36,Citation55,Citation56 The change in the dose schedule from 3 doses to 2 doses should help increase completion rates among preadolescents and adolescents. Future research may benefit from distinguishing between completion of 2-dose and 3-dose HPV vaccines and exploring community-level factors (e.g., racial / ethnic composition, area-based socioeconomic status), social context, economic conditions, and physical circumstances that may affect vaccination rates.

In 2016, the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable identified system-level approaches for improved uptake of the HPV vaccine as an important research gap.Citation57 Future research should identify systemic barriers that may interfere with series completion. Intervention development should focus on improving accessibility and addressing the research gaps recommended by the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable. For example, improving accessibility would likely improve completion rates. Parents in this study reported significant difficulty for vaccine series initiation and completion because of work / school schedule conflicts. This is in line with findings from the National Immunization Survey (NIS) 2008–2012 data. NIS showed that low HPV vaccine uptake (16%) was due to systemic barriers, such as lack of access to clinics during hours of operation.Citation58 More frequently reported barriers included vaccine misinformation, worry about safety, and lack of knowledge about the vaccine.

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths to this study. First, it is one of the few studies assessing HPV and HPV vaccine in a medically underserved, economically disadvantaged, high-risk Hispanic population in Starr County, Texas. Specifically, this study provides current estimates of and disparities in HPV knowledge and awareness in an already disadvantaged population. This helps inform what interventions are needed and more importantly what subgroups to target to help increase vaccine uptake. Otherwise, there is a potential to increase health inequalities if there is low vaccine uptake. Second, we assessed a survey sample that includes males. This has become increasingly important as many HPV-associated cancers occur in men and the approval of the HPV vaccine for use among boys.Citation53 Next, we evaluate the role of parental gender and child’s age and gender in the uptake of the HPV vaccine among school-age children. Last, this study may elucidate the barriers or reasons for not initiating or completing HPV vaccination.

The current study also had limitations. First, we did not assess actual HPV vaccination patterns. The self-reported nature of our measures may pose limitations. For example, parents’ recall of HPV vaccine history and provider recommendations may be misreported. Second, we did not assess current healthcare provider awareness and recommendation practices, which could possibly explain the differences seen in the study responses. Third, low survey response rates may be attributed to the characteristics unique to the study population, i.e., lower health literacy / education, low socioeconomic status, vaccine belief / attitudes, and gender differences. The response rate was lower than expected due to other end-of-the-year activities and mandatory testing. The highest responses were from 7th- grade parents / guardians. A power analysis was conducted and confirmed that the response rate was powered to detect clinical meaningful differences. A fourth is the limited generalizability of our respondents, who were selected from a specific geographic area. The results may not be generalizable to the rest of the Texas or the US. The respondents may be more engaged because of current CPRIT efforts to improve HPV vaccine uptake. Next, the response rate was low and could lead to selection bias (undercoverage and volunteer response bias). It is possible that the low response rate reflects an underrepresentation of the problem. It might also reflect sensitivities about the general topic of HPV or lack of a baseline response incentive. The potential for bias increases if the respondents were different from nonrespondents, i.e., age, education, and socioeconomic status. Last, the current study included a small sample of male respondents, which may not be the representative of all RGCCISD male parents / guardians.

Conclusions

The HPV vaccination coverage in RGV is low, with only 28.2% initiation (≥1 dose) and 18.8% completion (≥2 doses) of the HPV vaccine series. Although parents and guardians of RGCCISD students (4th–12th graders) report high awareness of HPV and the HPV vaccine, healthcare providers need to actively engage with parents to discuss HPV and the HPV vaccine. A strong body of evidence speaks to the importance of increasing the frequency and quality of provider recommendations for HPV vaccination, especially in an economically disadvantaged, predominately Hispanic population. Given the positive influence of healthcare providers on parental decisions to the vaccine, future studies should examine various interventions and education that target underrecommended groups, men and Hispanics, to increase knowledge and awareness about HPV, the HPV vaccine, and HPV-associated cancers to promote greater HPV vaccine uptake and reduce parental hesitancy toward vaccination.

Materials and methods

Study overview

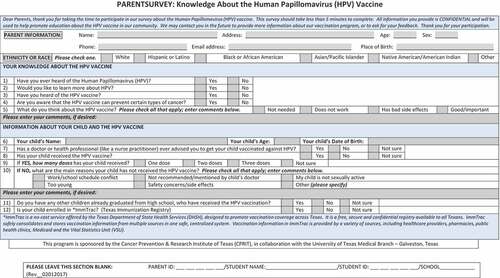

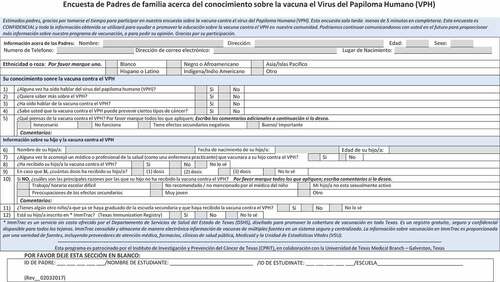

This study was conducted as part of the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT)-funded study to increase HPV vaccination in the RGV. Our CPRIT-funded project includes two components: educational events in Cameron, Hidalgo, and Starr Counties and implementation of the first school-based HPV vaccination program in Texas. The HPV Parent Survey “Knowledge about the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine” (Appendix A) was developed to assess parent-reported HPV vaccination rates as well as parental knowledge and attitudes toward the HPV vaccination before strategies were implemented to increase HPV vaccination uptake in the RGCCISD. Prior to the implementation of this study, the guidelines for the dosing schedule were changed. In October 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its guidelines and reduced the recommended dosing schedule for those initiating before age 15 to 2 doses given at least 6 months apart.Citation59,Citation60 Three doses are still recommended for those initiating on or after their 15th birthday and for people with certain immunocompromising conditions.Citation59 This affects the evaluation of vaccine completion in the population of interest in our study — changing the requirement from three doses to two doses for those initiating before age 15.

Survey participants and collection

The target audience for the Parent Survey was parents / guardians of RGCCISD students enrolled in grades 4–12. The UTMB Institutional Review Board approved the use of the HPV Parent Survey as a knowledge assessment tool and for the collection of sensitive confidential information. Surveys were distributed to 4th–12th grade students in RGCCISD homeroom classes. Students took the surveys home to their parents or guardians for completion. The RGCCISD encompasses 15 school campuses and 159 homerooms. Collection sites monitored for late submissions of completed surveys. The survey enrollment packet was provided in English and Spanish and included an introductory cover letter, HPV Parent Survey, CDC HPV factsheet, and return envelope. Several attempts were made to get a higher response, including reaching out to parents directly and working with school officials.

Survey questions/measures

Parents / guardians completed the survey. The exact survey questions are provided in Appendix A. Demographic information was collected for both the parent / guardian (age, gender, race / ethnicity, and place of birth) and the RGCCISD student (age). Survey participants were asked to provide their knowledge and awareness about HPV and the HPV vaccine. For their child, they were asked if they received a recommendation from a healthcare provider, if their child received the HPV vaccine and number of doses, and reasons why their child has not received the vaccine. They were also asked if they had other children who already graduated high school and if they were enrolled in ImmTrac, Texas Immunization Registry.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe parents’ knowledge and attitude and children’s experience. Chi-square tests were used to compare group differences. For groups with a limited count under null distribution (20% or more cells in the contingency table with an expected count less than 5), for which a Chi-square test might be misleading, a Fisher’s exact test was used instead. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We believe that our study was powered to detect clinical meaningful differences. We determined that our final sample size reached a power of 90% to detect at least effect size of 0.15 based on Chi-square test with 2 degrees of freedom.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor, Goldie Tabor, for her involvement in preparing this manuscript.

Special thanks to Iris Tijerina, the on-site coordinator in Starr County, Texas. Ms. Tijerina was responsible for the dissemination and collection of surveys. Special thanks to David (En Shou) Hsu for his work in data management and analysis.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dochez C, Bogers JJ, Verhelst R, Rees H. HPV vaccines to prevent cervical cancer and genital warts: an update. Vaccine. 2014;32(14):1595–601. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.081.

- Schiffman M, Wentzensen N, Wacholder S, Kinney W, Gage JC, Castle PE. Human papillomavirus testing in the prevention of cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(5):368–83. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq562.

- Thomas TL, Strickland O, Diclemente R, Higgins M. An opportunity for cancer prevention during preadolescence and adolescence: stopping human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancer through HPV vaccination. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5,Supplement):S60–S68. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.011.

- Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–19. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F.

- Emiko PM, Joseph A, Bocchini MD Jr, Hariri S, Harrell Chesson P, Robinette Curtis, MD PC, Mona Saraiya MD. Basic Information about HPV-associated cancers. Centers for disease control and prevention. [ Accessed 2014 Aug 24]. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cancers statistics. 2014. [Accessed 2015]. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emiko PM, Bocchini JA Jr, Susan Hariri MD, Chesson H, Curtis CR, Saraiya M, Unger ER, Markowitz LE. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. 2015. p. 300–03. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6411a3.htm.

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Chesson HW, Curtis CR, Gee J, Bocchini Jr JA, Unger ER. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(Rr–05):1–30.

- Shah PD, Gilkey MB, Pepper JK, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Promising alternative settings for HPV vaccination of US adolescents. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):235–46. doi:10.1586/14760584.2013.871204.

- Lee LY, Garland SM. Human papillomavirus vaccination: the population impact. F1000Res. 2017;6:866. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10493.2.

- Bloem P, Ogbuanu I. Vaccination to prevent human papillomavirus infections: from promise to practice. PLoS Med. 2017;14(6):e1002325. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002230.

- Hilton S, Hunt K, Bedford H, Petticrew M. School nurses’ experiences of delivering the UK HPV vaccination programme in its first year. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:226.

- Bosch X, Harper D. Prevention strategies of cervical cancer in the HPV vaccine era. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(1):21–24. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.07.019.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomasvirus vaccination - updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practice. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(49):1405–08. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5.

- Adjei Boakye E, Tobo BB, Rojek RP, Mohammed KA, Geneus CJ, Osazuwa-Peters N. Approaching a decade since HPV vaccine licensure: racial and gender disparities in knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2713–22. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1363133.

- Immunization and infectious diseases | healthy people 2020. 2015. [Accessed 2015 Aug 1]. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Fredua B, Williams CL, Meyer SA, Stokley S. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017;66(33):874–82. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007–2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2013 - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(29):591–95.

- President’s Cancer Panel Annual Report 2012–2013. Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: urgency for action to prevent cancer. [ Accessed 2018 Aug 29]. http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/ExecutiveSummary.htm#sthash.PcA0EnNk.dpbs.

- Newman PA, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Baiden, P, Tepjan, S, Rubincam, C, Doukas, Nand Asey, F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019206. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206.

- Anderson A, Taylor Z, Georges R, Carlson-Cosentino M, Nguyen L, Salas M, Vice A, Bernal N, Bhaloo T. Primary care physicians’ role in parental decision to vaccinate with HPV vaccine: learnings from a South Texas hispanic patient population. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;20(5):1236–42. doi:10.1007/s10903-017-0646-9.

- Furgurson KF, Sandberg JC, Hsu FC, Mora DC, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. HPV knowledge and vaccine initiation among Mexican-Born farmworkers in North Carolina. Health Promot Pract. 2019;20(3):445–54. doi:10.1177/1524839918764671.

- Fleming WS, Sznajder KK, Nepps M, Boktor SW. Barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccination in the VFC program. J Community Health. 2018;43(3):448–54. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0457-x.

- Sherman SM, Nailer E. Attitudes towards and knowledge about human papillomavirus (HPV) and the HPV vaccination in parents of teenage boys in the UK. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195801. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195801.

- Donahue KL, Hendrix KS, Sturm LA, Zimet GD. Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among 9–13 year-olds in the United States. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:892–98. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.10.003.

- Brown B, Gabra MI, Pellman H. Reasons for acceptance or refusal of human papillomavirus vaccine in a California pediatric practice. Papillomavirus Res. 2017;3:42–45. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2017.01.002.

- Clark SJ, Cowan AE, Filipp SL, Fisher AM, Stokley S. Understanding non-completion of the human papillomavirus vaccine series: parent-reported reasons for why adolescents might not receive additional doses, United States, 2012. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(3):390–95. doi:10.1177/003335491613100304.

- Rutten LJ, St Sauver JL, Beebe TJ, Wilson PM, Jacobson DJ, Fan C, Breitkopf CR, Vadaparampil ST, Jacobson RM. Clinician knowledge, clinician barriers, and perceived parental barriers regarding human papillomavirus vaccination: association with initiation and completion rates. Vaccine. 2017;35(1):164–69. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.012.

- Daley MF, Kempe A, Pyrzanowski J, Vogt TM, Dickinson LM, Kile D, Fang H, Rinehart DJ, Shlay JC. School-located vaccination of adolescents with insurance billing: cost, reimbursement, and vaccination outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(3):282–88. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.011.

- Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Gallivan S, Albertin C, Sandler M, Blumkin A. Effectiveness of a citywide patient immunization navigator program on improving adolescent immunizations and preventive care visit rates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(6):547–53. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.73.

- Allison MA, Hurley LP, Markowitz L, Crane LA, Brtnikova M, Beaty BL, Snow M, Cory J, Stokley S, Roark J, Kempe A. Primary care physicians’ perspectives about HPV vaccine. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20152488. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2488.

- Hswen Y, Gilkey MB, Rimer BK, Brewer NT. Improving physician recommendations for human papillomavirus vaccination: the role of professional organizations. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(1):42–47. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000543.

- Kornides ML, McRee AL, Gilkey MB. Parents who decline HPV vaccination: who later accepts and why? Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S37–S43. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.06.008.

- Javaid M, Ashrawi D, Landgren R, Stevens L, Bello R, Foxhall L, Mims M, Ramondetta L. Human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in texas pediatric care settings: a statewide survey of healthcare professionals. J Community Health. 2017;42(1):58–65. doi:10.1007/s10900-016-0228-0.

- Nickel B, Dodd RH, Turner RM, Waller J, Marlow L, Zimet G, Ostini R, McCaffery K. Factors associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination across three countries following vaccination introduction. Prev Med Rep. 2017;8:169–76. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005.

- Ganczak M, Owsianka B, Korzen M. Factors that predict parental willingness to have their children vaccinated against HPV in a Country with low HPV vaccination coverage. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:4. doi:10.3390/ijerph15061188.

- Lacombe-Duncan A, Newman PA, Baiden P. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability and decision-making among adolescent boys and parents: A meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. Vaccine. 2018;36(19):2545–58. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.079.

- Cipriano JJ, Scoloveno R, Kelly A. Increasing parental knowledge related to the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. J Pediatr Health Care. 2018;32(1):29–35. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.06.006.

- Nehme E, Patel D, Oppenheimer D, Karimifar M, Elerian N, Lakey D. Missed opportunity: human papillomavirus vaccination in Texas. Austin, TX: The University of TexasScience Center at Tyler/University of Texas System; 2017. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5756c8d1356fb02fbe7d19eb/t/5afc9508562fa76ce54a07e8/1526502668857/hpv_vaccination_in_texas_cit.pdf.

- Overview of HIV/AIDS in the Texas-Mexico Border Region | AIDS Education and Training Centers National Coordinating Resource Center (AETC NCRC). 2015. [ Accessed 2015 Aug 1]. http://aidsetc.org/border/profile-texas.

- Brown A. The unique challenges of surveying U.S. Latinos. Pew Research Center; 2015. [Accessed 2015 Aug 1]. https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/2015/11/12/the-unique-challenges-of-surveying-u-s-latinos/.

- Evans B, Quiroz RS, Athey L, McMichael, J., Albright, V., O’Hegarty, M. and Caraballo, R.S. Customizing survey methods to the target population - innovative approaches to improving. 2008. [Accessed 2015 Aug 1]. https://www.rti.org/sites/default/files/resources/evans_aapor08_paper.pdf.

- O’Hegarty M, Pederson LL, Thorne SL, Caraballo RS, Evans B, Athey L, McMichael J. Customizing survey instruments and data collection to reach hispanic/latino adults in border communities in Texas. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S159–S164. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.167338.

- Sanderson M, Coker AL, Eggleston KS, Fernandez ME, Arrastia CD, Fadden MK. HPV vaccine acceptance among Latina mothers by HPV status. J Women’s Health. 2009;18(11):1793–99. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1266.

- Center for Reproductive Rights. Nuestro voz, nuestro salud, nuestro Texas: the fight for women’s reproductive health in the Rio Grade Valley. New York (NY): Center for Reproductive Rights; 2015. [Accessed 2015 Aug 1]. https://reproductiverights.org/press-room/new-investigation-details-devastating-impact-of-texas-family-planning-cuts-on-latinas.

- CDC. HPV-associated cancers rates by race and ethnicity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published 2017. 2017 Jul 17 [Accessed 2018 Jun 12]. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/race.htm.

- Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1673–79. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0326.

- Hanson KE, Koch B, Bonner K, McRee AL, Basta NE. National trends in parental human papillomavirus vaccination intentions and reasons for hesitancy, 2010–2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(7):1018–26. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy232.

- Katz ML, Krieger JL, Roberto AJ. Human papillomavirus (HPV): college male’s knowledge, perceived risk, sources of information, vaccine barriers and communication. J Mens Health. 2011;8(3):175–84. doi:10.1016/j.jomh.2011.04.002.

- McKee C, Bohannon K. Exploring the reasons behind parental refusal of vaccines. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2016;21(2):104–09. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.104.

- Henry KA, Swiecki-Sikora AL, Stroup AM, Warner EL, Kepka D. Area-based socioeconomic factors and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among teen boys in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2017;18(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4567-2.

- Cartmell KB, Young-Pierce J, McGue S, Alberg, A.J., Luque, J.S., Zubizarreta, M. and Brandt, H.M. Barriers, facilitators, and potential strategies for increasing HPV vaccination: A statewide assessment to inform action. Papillomavirus Res. 2018;5:21–31. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2017.11.003.

- Marlow LA, Zimet GD, McCaffery KJ, Ostini R, Waller J. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination: an international comparison. Vaccine. 2013;31(5):763–69. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.083.

- Thomas TL, Strickland OL, Mothers HM, Fathers S. Human papillomavirus immunization practices. Fam Community Health. 2017;40(3):278–87. doi:10.1097/FCH.0000000000000104.

- Valdez A, Stewart SL, Tanjasiri SP, Levy V, Garza A. Design and efficacy of a multilingual, multicultural HPV vaccine education intervention. J Commun Healthc. 2015;8(2):106–18. doi:10.1179/1753807615Y.0000000015.

- Morales-Campos DY, Parra-Medina D. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccine initiation and completion among Latino mothers of 11- to 17-year-old daughters living along the Texas-Mexico Border. Fam Community Health. 2017;40(2):139–49. doi:10.1097/FCH.0000000000000144.

- Reiter PL, Gerend MA, Gilkey MB, Perkins, R.B., Saslow, D., Stokley, S., Tiro, J.A., Zimet, G.D. and Brewer, N.T. Advancing human papillomavirus vaccine delivery: 12 priority research gaps. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S14–S16. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.023.

- Cheruvu VK, Bhatta MP, Drinkard LN. Factors associated with parental reasons for “no-intent” to vaccinate female adolescents with human papillomavirus vaccine: National immunization survey - teen 2008–2012. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):52. doi:10.1186/s12887-017-0969-7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinician FAQ: CDC recommendations for HPV vaccine 2-dose schedules. Published 2016. accessed 2016 Nov 30. [accessed 2018]. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/downloads/hcvg15-ptt-hpv-2dose.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinician FAQ: CDC recommendations for HPV vaccine 2-dose schedules. 2016. [Accessed 2015 Aug 1]. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/2-dose/clinician-faq.html.