ABSTRACT

“Values-based decision-making” frameworks and models are widely described in the literature in various disciplines, including healthcare settings. However, there is a paucity of literature on the application of systematic methods or models in the biopharmaceutical research and development (R&D) field of drugs, vaccines, and immunotherapeutics.

In this report, we describe our model that uses company values along with framing questions in a five-step process to guide ethical decisions in the vaccines R&D context. The model uniquely supports practical prospective decision-making: employees are engaged as moral agents applying values and principles to guide their decision in a specific situation. We illustrate, by way of case studies, how the model is being used in practice. The consistent application of company values during decision-making calls upon employees to use their judgment, therefore reducing the need for the organization to systematically generate written instructions. Finally, we report on preliminary results of model adoption by teams within our organization, discuss its limitations and likely future contribution. We applied our model within a vaccines R&D context and believe its use can be extended to other areas where business-related decisions impact patients.

Introduction

Values-based decision making has been defined as “decision making based on the values of the organization and the goals these values support”,Citation1 and as organizational ethics which intentionally uses values to guide the decisions in a “proactive and not just reactive way”.Citation2,Footnote1

Ethical decision-making models have been widely applied and studied in many disciplines, particularly within the clinical healthcare context.Citation3 Although it is now recognized that decision making in the biopharmaceutical industry should be driven by values-based considerations,Citation4 there is a paucity of literature on systematic methods or decision models applied in this industry setting that innovates and produces drugs, vaccines, and immunotherapeutics.

Although many biopharmaceutical companies publicly communicate their core organizational values,Citation5-Citation8 there may be variations in their interpretation, and their application in day-to-day decision making may not be straightforward.

In this paper, we first describe our search for evidence of models used to make ethical and values-based decisions in the context of vaccines research and development (R&D) activities in a biopharmaceutical industry setting.

We then describe a practical model developed to aid prospective decision making and illustrate its practical application, using real case studies. Next, we report on how it is being introduced to employees through workshops and summarize feedback from attendees. Finally, we discuss the potential contribution, and limitations, of such a model in the biopharmaceutical R&D setting, as well as propose ways forward for its application and development.

Review of evidence on ethical decision making

(See search terms in Supplementary material)

There exists a substantial body of literature on ethical decision making in a wide range of disciplines (e.g., in psychological counseling, healthcare management, and in a business context), and decision-making models all tend toward a broadly similar format.Citation3,Citation9-Citation12 However, research into decision making in the biopharmaceutical industry is limited to a survey published in 2005,Citation13-Citation15 based on in-depth interviews with personnel from 13 bioindustry companies. It includes examples of pharmaceutical companies using a variety of initiatives to encourage employees to refer to company values while making important decisions. The survey findings support our assertion that these values can play an important part in making ethical decisions in business.

A more recent framework for ethical decision making in biopharmaceutical industry R&D has been described as “a useful model for translating ethical aspirations into action – to help ensure pharmaceutical human biomedical research is conducted in a manner that aligns with consensus ethics principles, as well as a sponsor’s core values.”Citation16 Although there is evidence for the usefulness of applying an ethical decision-making model to evaluate past real-life cases,Citation17 a model for systematic and prospective evaluation of decision options according to values has not yet been reported.

Due to the operative nature of the biopharmaceutical R&D context, models for decision-making need to facilitate the choice of options that will result in implementable solution. We propose a practical method to prospectively guide a decision through values-assessment of options (that is, what needs to be done from the choice of actionable solutions). In the same way that a “moral compass tool” approach relates the understanding and interpretation of moral concepts to the situated contexts of concrete practices,Citation18 our model defines and frames values in the operative context in which the decision takes place, rather than solely considering them in their abstract form on a theoretical-normative level (that is, what ought to be done following a certain ethical theory).

Our decision-making model is used within GSK Vaccines for resolving complex questions encountered within the R&D context that have an impact on the rights and well-being of patients and/or research participants, as well as questions around engagement with the scientific community. Such decisions are under the scope of the company’s Vaccines Medical Governance & Bioethics team and Chief Medical Officer, from product discovery until licensure and use by patients.

Values-based model for decision making

Understanding what values mean is important for how they will be applied in decision making. Previous researchers have shown that value sets used in decision-making frameworks, and even the meanings attributed to individual values, can vary between different healthcare organizations.Citation19 For example, “transparency” may be interpreted differently by different people, while if it is explicitly defined, there can be shared understanding and alignment among employees on what is meant by it and how they are expected to apply it.

In our model, GSK company valuesFootnote2 (transparency, respect, integrity and patient focus, known by the acronym TRIP) have been defined and their application facilitated by questions that help frame their meaning. For example, on what transparency means when applied to a proposed solution, by posing the framing question upfront: “How will we inform relevant stakeholders and share this decision?” the employee can reflect and assess whether their proposed action will be transparent. Other examples of framing questions for integrity, respect for people, and patient focus values are presented in .

Table 1. Values and framing questions.

In order to make decisions in an operative environment such as R&D, the context in which the decision takes place needs to be accounted for. We defined four contextual factors that influence the choice of decision options: Timing, Intent, Proportionality, and Perception (or TIPP, see ). The implementation of a decision must take place at a time when there is a legitimate need for it to occur, for example deciding to donate vaccines during humanitarian crisis. The intent of each option needs to be clarified so that its appropriateness may be assessed, for example whether the aim of an external presentation is to communicate science or convey promotional messages. The scale of the proposed solution should be proportional to the need, so that the question is resolved without creating additional problems – for example, using images as a way of communicating disease awareness should not raise unjustified fear. Feasibility and cost of options are also evaluated as part of proportionality, putting in perspective the responsible use of limited resources. Finally, the solution should be checked to ensure it will be perceived as consistent with regard to considered timing, intent, and proportionality.

Table 2. Contextual factors and framing questions.

Decision making steps

Structured decision making follows a logical flow from gathering background information to generating options and evaluating them. Evaluation of options is done according to a set of objective criteria that would qualify one option as most acceptable or favorable over other options.Citation20-Citation22 Ethical decision making, on the other hand, sees options evaluated according to moral criteria or values.Citation23 In our model we adopted company values as a basis for ethical evaluation and integrated them into the decision-making process, which aims to select the best possible option in the particular situation, taking into consideration the impacts on the various stakeholders. The integration of company values makes it easier for employees to relate to them, ensuring alignment and consistency between employees’ understanding on a personal and organizational level, as has already been described in a business context.Citation24

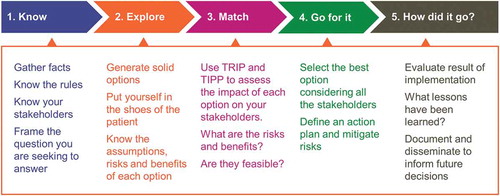

Our decision-making process comprises five steps, and the values assessment of options is integrated in Step 3 (). Our model has elements in common with others. It begins with the problem statement. It encourages users to put themselves in the shoes of the patient, and to check what rules and regulations apply to the specific situation.Citation18 But, uniquely, our model incorporates the company values into a structured assessment of the possible solutions ().

Model application

Although the model may be applied to decision-making by individuals, the experience reported here is derived from application by research teams. and describe two real-life examples of prospective decision-making, while illustrates a use of the model to interrogate a decision that pre-dates the implementation of the TRIP & TIPP model. When they encounter a complex question, it is usually escalated to an internal multidisciplinary bioethics board for their deliberation and decision. When using the model, members from the research team themselves generate decision options following steps 1 and 2, which they subsequently evaluate by using the values-based assessment of each option in step 3. Values assessment of options proposed by the team is concurrently performed by the board using the same model. All answers are collected by a mobile application developed for this purpose and the aggregate result of the responses is shared with the board, which includes a neutral facilitator with a relevant understanding of the business and bioethics. Deliberation is achieved following clarification on any points in which there are major discrepancies in the collected answers. Resolution is again sought in alignment with TRIP & TIPP principles.

This process allows for the so-called top-down (by bioethics board) and bottom-up (by research team) assessments to be complemented,Citation25 whereby both teams and board apply the same values-based decision-making model. Employees are thus engaged as moral agents at the center of decisions, which has the potential to increase their autonomy and competence, as has been reported in healthcare settings.Citation26,Citation27

Values-based decision making workshops: employee experience and feedback

The values-based decision-making model, known within the company as the “TRIP & TIPP model,” has so far been introduced to 956 employees in GSK Vaccines R&D with backgrounds in research, clinical, medical, safety or regulatory, through workshops in which hypothetical case studies are used to practice the methodology in a collaborative fashion. Approximately half of these attended a face-to-face session, in groups of 18 employees on average; the others took part in virtual sessions, in which groups of 24 employees on average connect online to an interactive session run by a live presenter. In both types of sessions, feedback was sought immediately afterward, and additionally by survey 6 months postsession.

In a survey of 470 workshop participants who attended face-to-face sessions held between February 2017 and May 2019, 87% responded that they would find the model helpful for decision-making. Negative – though constructive – feedback was received from 1.8%. (Response rate = 82%). Feedback following virtual sessions held between October 2018 and June 2019 gave similar results: 91% of responders found the model helpful (response rate = 79%).

At 6 months after face-to-face workshop attendance, 49% of respondents said they had used the TRIP & TIPP model after the workshop and most of them (87%) found it useful (response rate 33%). Results from a 6-month survey following virtual workshop are similar: 44% used the model and 96% found it useful, but the response rate to this survey was lower (17%).

Discussion

This is in our opinion the first report of application and early assessment of a values-based decision-making model in the biopharmaceutical context. The novel element of the GSK Vaccines model is that, although it can be applied to both future and past cases (Boxes 1, 2, and 3), its primary purpose is to determine prospective solutions in line with company values. This distinguishes it from previously reported theoretical models that have been developed in order to test decisions already made.Citation17

Like most ethical decision-making models used in different fields, our model follows the pattern of facts gathering, option generation, option assessment according to ethical criteria, preferred option choice, and retrospective evaluation.Citation20-Citation22 Previous research in the field of business ethics has reported the need to complement consequentialist and deontological ethics approaches with a virtue-based orientation to make the most comprehensive ethics decision model.Citation28-Citation30 The foundational elements of our model apply such a complementary approach and uniquely support practical prospective decision making: employees are engaged as moral agents applying values and principles to guide their decision in a specific situation.

Practically, our model and its application dynamics (i.e., using group deliberations) help employees make decisions in a focused, structured way, moving away from a purely intuitive approach. Moral intuition is guided by the systematic use of explicit framing questions to increase the understanding and clarity of values during the process of decision-making. Value application is further facilitated by an explicit definition of the context with contextual questions. Increasing the recognition and clarity of the values inherent to practice-based decision making has been reported to promote sound ethical reasoning.Citation31 Moral intuition is further aided by the scoring of different options, which helps to detect and distinguish the ethical tension between the values that those options generate and where reasoning and discussion need to focus. For example, the value of respect in the case study in prompted a reflection on whether the status of “employees” ever justifies preferential access to vaccination over “citizens”.

Because of potential discrepancies between values at personal and organizational levels, it is important for individuals to have a good understanding of what organizational values intend and what the expectation is for them to behave in alignment with such values.Citation3 The framing of company values in our model helps to “bring those values to life” by connecting with the more personal intuitive level. Better application of company values has the potential to increase the autonomy and competence of employees involved, as it has been shown to do in healthcare settings.Citation26 We believe that by strengthening the alignment between company and personal values our employees can more easily assume the role of “moral agents” driving company decisions, which is also supported by the feedback received on our workshop exercises. Virtue-based training that emphasizes internal values rather than externally imposed rules, and focuses on the virtuous characteristics of staff, is expected to lead to responsible and exemplary behavior.Citation32,Citation33

From our experience, the application of company values to drive decision making reduces the need to systematically generate written instructions, such as new or more complex “standard operating procedures” (or SOPs), and could also potentially reduce the number and volume of existing instructions. For example, the company’s code of practice for scientific external engagement has been significantly reduced in length and complexity thanks to the introduction of the TRIP & TIPP values-based model.

There is also some evidence that when moral case deliberations involve actors in the healthcare setting, they can have a measurable positive impact on interpersonal relationships and increase their engagement with the ethical dimension of their work.Citation26 This supports our model’s dynamics, and in particular the involvement of impacted teams in evaluating options. This may also be preferable to the practice of routinely escalating ethical questions to a specific or senior board for resolution without engaging the ethical judgment of the team that is dealing with the situation on the ground.

The model facilitates continuous improvements through experienced learnings. Step 5 of the model, “How did it go?”, calls for retrospective evaluation of the result and documentation of the lessons learned. In practice, we have created a repository of all cases so that future decision making may benefit from comparison with previous cases. Experience so far has demonstrated the critical influence of contextual factors, which can result in quite different decisions in cases that may on the surface seem very similar (for an example of this, see the case in Box 2). Finally, in common with the healthcare setting, the biopharmaceutical industry shares a patient-centered mission. However, unlike the healthcare sector, the “patient” in the biopharmaceutical context is not known at the time decisions are made; hence, the decision needs to consider anonymous patients, research participants, currently healthy populations (in the context of vaccines), and very often future patients during drug development stages. It has been shown that when “someone” is distant and in the future, it is more difficult to make ethical decisions than when this someone is here and now and will be directly impacted by the decision.Citation34 This can also be related to the idea of ethical awakening coming from the “Other” where “ethics cannot be separated from leadership and leaders’ responsibility to Others”.Citation35 Therefore, we believe that by bringing the patient dimension into the “proximity” where practical decision-making takes place – as we do by having the specific value of “Patient Focus” – our model helps to evoke the “otherness” in employees’ minds, thus getting them closer to bringing the patient-related values to the forefront.

Limitations

Practical experience of the model we report here is limited, and there is a need to expand our case study database at GSK Vaccines. Gathering and analyzing more structured feedback from users – including information on how much and in what ways the tool helped them in their decision-making – will also supply information about how the model is applied in real life and the quality of the outcomes.

Our assessment of the medium-term impact of the training is limited by the small size of the data set. Although response rates to our six-month survey seem low, at 33% for the face-to-face and 17% for the virtual, they are in fact of a similar order to average response rates reported in the literature for online surveys in evaluating educational courses.Citation36 The higher response rate for the face-to-face workshops suggests these are more engaging than the virtual sessions. We are building on the experience from these preliminary surveys as a basis for designing a larger scale and more in-depth and structured survey to enable a robust assessment of our model and its use.

It could be argued that the values in our model do not provide clear moral guidance for action – a common criticism of principlism,Citation37 which also refers to decision making by applying the four biomedical ethics principles developed by Beauchamp & Childress (non-maleficence, beneficence, autonomy, justice).Citation38 As with principlism, the values in our model are specified, weighed and related to each other according to the specifics of the situation and organization. But in our model, moral guidance is further strengthened by the use of framing questions related to values and contextual factors, and the structured five-step approach.

Further, our model is not an automated tool based on algorithms; it relies on human judgment, which is prone to subjectivity resulting from differences in individual and personal understanding. In our approach, this risk is mitigated by the involvement of a neutral facilitator who has a relevant understanding of the business and bioethics but has no direct interest in the decision outcome. Furthermore, the multidisciplinary group assessment mitigates against subjectivity because of the many different perspectives represented.

There is a theoretical risk that the model could be (ab)used to justify a pre-chosen or preferred option. Related to this is the risk that certain values or preferences (e.g., consensus) may be given undue prominence in order to achieve a pre-chosen outcome. Such biases are avoided by giving priority to the value of patient focus. It is also important to gather and then document the consideration of quality data (facts, laws, regulations) to achieve the highest quality of generated options. Furthermore, there is the opportunity for continuous improvement and learning to increasingly avoid bias.

Finally, a further limitation is the likelihood of bias resulting from the decision-making team being company employees, with no independent actors. In fact, our model has been specifically developed for internal decision making because of the need to generate applicable solutions to the specific biopharmaceutical context, that is, R&D. Although it does not foresee systematic recourse to external (bioethics) expert advice or panels,Citation39 it does not preclude asking for or including such knowledge as appropriate. In some cases, specific questions may require input from independent stakeholders, for example, patient and/or ethical advisory groups.

Conclusions and way forward

This is in our opinion the first publication describing the implementation and early assessment of a values-based decision-making model in the biopharmaceutical industry. Our model brings an innovative approach through the integration of company values into option assessment, which guides and actively engages employees in the practical decision making. It has been applied within vaccines R&D scope but, as it provides a set of decision tools that can be applied by anyone in the line of accountable decision making, its application can be extended to other areas where business-related decisions impact patients.

We intend to further develop the model with more prospective case studies and refine its assessment, including impact on reduced length and number of written control standards (SOPs) in applicable areas. We plan to gather data regarding how often teams are using the model and how useful it is in their decision making; and to investigate which parts of the model the teams find to be clear and reliable and which need refinement and/or additional education. Equally, we would like to explore whether the methodology can be validated by comparing the examinations of similar cases by different teams to see if they arrive at similar decisions and/or lessons learned. By sharing our model, we encourage its application by other companies and also by stakeholders such as healthcare providers, patients, and investigators, which would be expected to contribute to the continuous refinement of the model and its application.

Box 1. Case study 1: Use of the model in human subject research.

Box 2. Case study 2: Use of the model for the assessment of vaccine access.

Box 3. Retrospective case: Children of minor parents in clinical research.

Contributors and sources

Tatjana Poplazarova had the original idea for combining GSK values with the 4 contextual factors that influence the choice of decision into a formal decision-making model, and she wrote the manuscript first draft. All three authors were responsible for the model development, its introduction and implementation; they participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript and approved the final version.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Tatjana Poplazarova, Claar van der Zee, and Thomas Breuer are full-time employees of the GSK group of companies and hold shares in the GSK group of companies as part of their employee remuneration.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Sandrine Fontaine for her contribution to model development and implementation, as well as workshop delivery. Thanks are also due to Virginie Hamtiaux, Sami Liman, Christine Vanderlinden, Nathalie De Broux, Tuni Randall, Ana Hornillo, Louise Stevenson, Marie Bayle-Normand, Johannie Coenen, Philibert Goulet, Guglielmo Cervello and Birgit Van de Vliet of GSK Vaccines, and Aurore Jacques of Valesta, part of Oxford Global Resources, Mechelen, Belgium (on behalf of GSK Vaccines), for their respective contributions either to the model’s implementation, or workshop delivery.

We also thank Veronique Delpire and Mandy Payne of Words & Science, Brussels, Belgium (on behalf of GSK Vaccines) for their contributions in the form of editorial support, critical content review, bibliographical expertise and development of workshop material.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1700714.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We emphasize here a distinction between “values-based” and “value-based”. The term “value-based decision making” is widely used within the healthcare and business environments, and although there is no universally accepted definition, it frequently refers to considerations of financial or commercial nature (example: NHS England Value-Based Decision Making, https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2016/09/value-based-decisions.pdf). In our article, we use the term values-based to make it clear that we refer specifically to organizational ethical or mission values.

References

- Mills AE, Spencer EM. Values based decision making: a model for achieving the goals of healthcare. HEC Forum. 2005;17:18–32.

- McCartney JJ. Values based decision making in healthcare: introduction. HEC Forum. 2005;17(1):1–5. doi:10.1007/s10730-005-4946-4.

- Kotalik J, Covino C, Doucette N, Henderson S, Langlois M, McDaid K, Pedri LM. Framework for ethical decision making based on mission, vision and values of the institution. HEC Forum. 2014;26(2):125–33. doi:10.1007/s10730-014-9235-7.

- International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations. Code of practice: upholding ethical standards and sustaining trust. 2019 [accessed 2019 Jul 4]. https://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/IFPMA_Code_of_Practice_2019.pdf

- Eli Lilly and Company. Who we are. 2019 [accessed 2019 Jul 4]. https://www.lilly.com/who-we-are

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc. Our values. 2019 [accessed 2019 Jul 4]. https://www.merck.com/about/our-values/

- Novartis AG. Our culture and values help us fulfill our purpose. 2019 [accessed 2019 Jul 4]. https://www.novartis.com/our-company/our-culture-and-values

- GSK group of companies. Our culture and values. 2018 [accessed 2019 Jul 4]. https://uk.gsk.com/en-gb/careers/working-at-gsk/our-culture-and-values/

- Bonde S, Briant C, Firenze P, Hanavan J, Huang A, Li M, Narayanan C, Parthasarathy C, Zhao H. Making choices: ethical decisions in a global context. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22:343–66. doi:10.1007/s11948-015-9641-5.

- Markkula Centre for Applied Ethics. A framework for ethical decision making. 2009 May [accessed 2019 Jul 4]. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/a-framework-for-ethical-decision-making/

- Ling TJ, Hauke JM. The ETHICS model: comprehensive, ethical decision making. Paper based on a program presented at: 2016 American Counseling Association Conference; 2016 April 3; Montréal, Québec. [accessed 2019 Jul 4]. https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/vistas/the-ethics-model.pdf

- Ferrell OC, Fraedrich J, Ferrell L. Business ethics: ethical decision making & cases. Vol. 12, Boston (MA): Cengage Learning; 2018.

- Mackie JE, Taylor AD, Finegold DL, Daar AS, Singer PA. Lessons on ethical decision making from the bioscience industry. PLoS Med. 2006;3(5):605–10. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030129.

- Finegold D, Moser A. Ethical decision making in bioscience firms. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(3):285–90. doi:10.1038/nbt0306-285.

- Finegold DL, Bensimon CM, Daar AS, Eaton ML, Godard B, Knoppers BM, Mackie JE, Singer PA. Bioindustry ethics. New York (USA): Elsevier Academic Press; 2005.

- Van Campen LE, Therasse DG, Klopfenstein M, Levine RJ, Lilly E. Company’s bioethics framework for human biomedical research. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(11):2081–93. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1087987.

- Merck CE. Vioxx: an examination of an ethical decision-making model. J Bus Ethics. 2007;76:451–61. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9302-3.

- Hartman L, Metselaar S, Widdershoven G, Molewijk B. Developing a ‘moral compass tool’ based on moral case deliberations: A pragmatic hermeneutic approach to clinical ethics. Bioethics. 2019;33(9):1012–1021. doi:10.1111/bioe.12617.

- Giacomini M, Kenny N, DeJean D. Ethics frameworks in Canadian health policies: foundation, scaffolding, or window dressing? Health Policy. 2009;89:58–71. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.04.010.

- Keeney RL. Decision analysis: an overview. Oper Res. 1982;30(5):803–38. doi:10.1287/opre.30.5.803.

- Guo KL. DECIDE: A decision-making model for more effective decision making by health care managers. Health Care Manag. 2008;27(2):118–27. doi:10.1097/01.HCM.0000285046.27290.90.

- Bradley R. Decision Theory: a formal philosophical introduction. London (England): London School of Economics and Political Science; 2014.

- Rest JR, Barnett R. Moral development: advances in research and theory. New York (NY): Praeger; 1986.

- James PS. Aligning and propagating organizational values. Procedia Econ Financ. 2014;11:95–109. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00180-4.

- Rasoal D, Skovdahl K, Gifford M, Kihlgren A. Clinical ethics support for healthcare personnel: an integrative literature review. HEC Forum. 2017;29:313–46. doi:10.1007/s10730-017-9325-4.

- Haan MM, van Gurp JLP, Naber SM, Groenewoud AS. Impact of moral case deliberation in healthcare settings: a literature review. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19:85. doi:10.1186/s12910-018-0325-y.

- Stolper M, Metselaar S, Molewijk B, Widdershoven G. Moral case deliberation in an academic hospital in the Netherlands. J Int Bioethique. 2012;23(3–4):53–66. doi:10.3917/jib.233.0053.

- Crossan M, Mazutis D, Seijts G. In search of virtue: the role of virtues, values and character strengths in ethical decision making. J Bus Ethics. 2013;113:567–81. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1680-8.

- Khalid K, Eldakak SE, Loke S-P. A structural approach to ethical reasoning: the integration of moral philosophy. Acad Strateg Manag J. 2017;16:81–113.

- Arjoon S. Ethical decision-making: a case for the triple font theory. J Bus Ethics. 2007;71(4):395–410. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9142-1.

- Wright-St Clair VA, Newcombe DB. Values and ethics in practice-based decision making. Can J Occup Ther. 2014;81(3):154–62. doi:10.1177/0008417414535083.

- Berling E, McLeskey C, O’Rourke M, Pennock RT. A new method for a virtue‑based responsible conduct of research curriculum: pilot test results. Sci Eng Ethics. 2019;25(3):899–910. doi:10.1007/s11948-017-9991-2.

- McLeskey CM, Berling EW, O’Rourke M, Pennock RT. Reviewing the responsible conduct of research (RCR) literature from a scientific virtue perspective. Presentation at: World Congress of Research Integrity; 2017 May 28–31; Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Jones TM. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: an issue-contingent model. Acad Manage Rev. 1991;16(2):366–95. doi:10.5465/amr.1991.4278958.

- Jones J. Leadership lessons from Levinas: revisiting responsible leadership. Leadersh Humanities. 2014;2(1):44–63. doi:10.4337/lath.

- Nulty DD. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess Eval High Educ. 2008;33(3):301–14. doi:10.1080/02602930701293231.

- Clouser KD, Gert B. A critique of principlism. J Med Philos. 1990;15(2):219–36. doi:10.1093/jmp/15.2.219.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Caplan AL, Teagarden JR, Kearns L, Bateman-House AS, Mitchell E, Arawi T, Upshur R, Singh I, Rozynska J, Cwik V, et al. Fair, just and compassionate: a pilot for making allocation decisions for patients requesting experimental drugs outside of clinical trials. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:761–67. doi:10.1136/medethics-2016-103917.

- Ott MA, Crawley FP, Sáez-Llorens X, Owusu-Agyei S, Neubauer D, Dubin G, Poplazarova T, Begg N, Rosenthal SL. Ethical considerations for the participation of children of minor parents in clinical trials. Pediatr Drugs. 2018 Jun;20(3):215–22. doi:10.1007/s40272-017-0280-y.