ABSTRACT

Debate continues regarding the need for a booster vaccination in children who received a universal infant hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination. The aim was to explore the need and the strategies for the booster HBV vaccination. 8-year prospective cohort study was conducted among children aged 5–15 years in 2009–2010 in Zhejiang Province. The participants were divided into groups A (<0.1 mIU/mL), B (0.1 to < 1 mIU/mL) and C (1 to <10 mIU/mL) according to the pre-booster anti-HBs antibody levels. 5 μg (group I), 10 μg (group II), 20 μg hepatitis B vaccines (group III) or 5 μg hepatitis A and B (HAB) vaccines (group IV) with 0-1-6-month schedule were randomly administered to children negative for all markers. Blood samples were collected at baseline HBV marker testing, 1 month after the first dose, 1 month, 1 year, 5 years and 8 years after the third dose. Among 4170 children, 2326 (55.8%) were negative for all HBV markers. Group II showed the highest seropositive rates of 92.8%, 99.7%, 97.6%, 90.3% and 83.4% with GMTs of 4194.5 mIU/ml, 4163.9 mIU/ml, 466.9 mIU/ml, 190.6 mIU/ml, 122.6 mIU/ml from 1 month after dose 1 to 8 years after dose 3, respectively (P < .01). Participants in group C showed seropositive rates of 98.9%, 99.9%, 99.5%, 95.5%, 92.8% after the revaccination with GMTs of 6519.6 mIU/ml, 5267.4 mIU/ml, 547.1 mIU/ml, 249.5 mIU/ml, 155.3 mIU/ml, respectively, higher than group A and B (P < .001), except 1 month after the third dose. The 10 μg of HBV vaccine with a 0-1-6-month booster regimen may elicit robust responses and persist for 8 years or longer. Additionally, 1-dose revaccination maybe suitable for children with 1 to < 10 mIU/ml anti-HBs titers.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is still one of the most common chronic viral infections and the main cause of primary liver cancer deaths globallyCitation1. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 257 million people have been infected (defined as hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive), with 887000 deaths in 2015.Citation2 Approximately 30% of the population shows serological evidence of current or past HBV infection,Citation3-5 indicating that it is still a major global health problem. As a 2006 national HBV seroepidemiological survey shows, China still belongs to the high-intermediate area, with a rate of 7.18%.Citation6,Citation7 Due to the routine HBV immunization of infants and a completely free HBV vaccination programme for all neonates, substantial reductions in new HBV infections and in carriers has been observed in China and in other countries. In China, the HBsAg prevalence in the general population decreased from 9.75% in 1992 to 7.18% in 2006, from 1.0% in 2006 to 0.3% in 2014 in the 1-4-year-old population, and from 10.1% in 1992 to 5.5% in 2006 and to 2.6% in 2014 in the 1-29-year-old population.Citation8 In Korea, the HBsAg seropositivity rate was 2.6% in 1993 in school children aged 6 to 17 years old but decreased to 0.44% in middle school students in 2007. In addition, it was 0.9% in infants and toddlers living in Seoul in 1995, while in 2007, it decreased to 0.2% in toddlers aged 4 to 6 years old in 2007.Citation9

Although universal vaccination could induce protective antibodies (hepatitis B surface antibody, anti-HBs ≥ 10 mIU/ml) in most healthy children after a routine primary series of hepatitis B vaccines, the duration of protection after the primary series of vaccines remains unknown. Previous studiesCitation9,Citation10 indicated that revaccination or booster doses should be considered for vaccinated children.

In the present study, we included 2326 children who were negative for HBsAg, anti-HBs and hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) to explore the effects of booster immunization. Then, we divided these subjects into four groups according to the dose of the hepatitis B vaccine. We examined the titers of anti-HBs in children with primary vaccination, the effects of different pre-booster anti-HBs titers and different booster hepatitis vaccines and the 8-year follow-up effect of revaccination.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The present study was conducted in Yuhuan, Longquan and Kaihua Counties in Zhejiang Province in 2009 and 2010 and aimed to evaluate the long-term efficacy of booster vaccination among children aged 5 to 15 years old. First, we selected two towns in each country as research sites and clustered the subjects based on school enrollment. Then, we obtained the immunization information of all children from the child’s immunization certificate kept by their parents or by reviewing the child’s immunization card kept at the township hospital, and we selected children who met our inclusion criteria. Third, we selected subjects whose blood tests for HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc were negative. We randomly selected 4170 subjects; 535 eligible subjects completed 8 years of follow-up. The flow chart of the participants enrolled in this study is shown in . This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Zhejiang Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and we obtained written informed consent from each participant.

The specific inclusion criteria were as follows: Children born between January 1, 1993, and January 1, 1997, who had received full doses of primary vaccination during infancy; never received a hepatitis B booster vaccination; willing to participate in the study and sign the informed consent form; without acute illness, fever and no allergies or severe reactions to vaccinations; all information regarding the study was provided by the subject’s parents or guardians; having no immune dysfunction; never received any immune suppressive therapy; at no risk of compromised immunity; never received any kind of vaccination within 4 weeks.

After acquiring informed consent from the subjects or from their parents or guardians, 3-ml blood samples were collected from each subject and preserved for HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc testing. Then, all the subjects were randomly administered a vaccination by intramuscular injection in the upper arm deltoid according to the immunization procedures for months 0, 1, and 6. Participants were stratified into four groups according to the dose of hepatitis B vaccine: group I, 5 μg (lot number: 20071223(1–9), Shenzhenkangtai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), group II, 10 μg (lot number: 20090309(01–06), Dalianhanxin Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), group III, 20 μg (lot number: 200802A21 (01–05), NCPC GeneTech Biotechnology Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) and group IV, hepatitis A (250 U inactivated HAV-Ag) and hepatitis B (5 μg) (HAB) combined vaccine (lot number: 2009040302, dosage: 250 U inactivated HAV-Ag and 5 μg HBsAg; Sinovac Biotech Co., LTD.). At 1 month after dose-1 and dose-3, 3-ml blood samples were collected from each subject and preserved for testing. One year, five years and eight years after the third dose, 2-ml blood samples were collected from the follow-up subjects and tested. In addition, subjects were divided into groups A (<0.1 mIU/mL), B (0.1 to <1 mIU/mL) and C (1 to <10 mIU/mL) according to the pre-booster anti-HBs antibody levels.

Lab testing

All frozen separated or fresh serum samples were sent to ADICON Clinical Laboratories Inc. in Hangzhou for the quantification of HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs by chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) during the 5-year follow-up. Samples collected at 8 years after dose 3 were sent to KingMed Diagnostics in Hangzhou for the quantification of anti-HBs by CLIA. An Architect-i2000 (Abbott Laboratories, USA) was used for the CLIA. The reagent lot number for the HBsAg tests was 70318HN00 (Abbott Laboratories), and an HBsAg ≥0.05IU/ml was considered positive. The reagents 75684M100 (Abbott Laboratories, USA) and 91245FN00 (Abbott Laboratories, USA) were used for the last anti-HBs tests, and an anti-HBs ≥10 mIU/ml was considered positive and able to provide protection against HBV infection. The commercial reagent 72448M100 (Abbott Laboratories, USA) was used for the anti-HBc tests, and S/CO≥1 was considered positive. Because we were unable to detect anti-HBs titers less than 0.01 mIU/ml, we assigned a value of 0.005 mIU/ml to these participants when calculating the geometric mean titer (GMT) of anti-HBs. When a log transformation was used for calculating the GMT, anti-HBs >15,000 mIU/mL were assigned a value of 15,000 mIU/mL at 1 month after dose-1 to 5 years after dose-3, while anti-HBs ≥1000 mIU/mL were recorded as 1000 mIU/mL at 8 years after dose-3.

Data analysis

We established a database using Epidata 3.2 (Epidata; Norway and Denmark), and statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 and Excel 2010. T-tests, one-way ANOVA tests, chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare variables among the study groups. The relationships between the GMT at different time points and age groups were compared by bivariate correlation tests. We used a two-tailed probability for the statistical tests, and p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline seroprevalence of HBV markers

Of the 4170 children aged 5 to 15 years old tested for HBV markers, 1.1% (44/4170) were HBsAg positive; 4.1% (171/4170) were anti-HBc positive; 40% (1668/4170) were positive for anti-HBs alone; and 55.8% (2326/4170) were negative for all markers ().

Recruitment of participants

Of the 4170 participants assessed for eligibility, 2326 children met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the current study. Subjects with three negative indicators (HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc) were included, and blood samples were collected at 1 month after dose-1, 1 month, 1 year, 5 year and 8 year after dose-3. Eight years later, 1791 subjects were lost to follow-up (). The 535 remaining participants included 251 males and 284 females, with an average age of 9.7 ± 3.0 years. No statistically significant differences were observed between groups when stratified by sex ().

Table 1. Age and sex distribution of the study subjects

Persistence in protection from the hepatitis B vaccine

All 4170 participants were evaluated for seroprotection of anti-HBs induced by the primary hepatitis B vaccination series in infancy. A total of 2406 participants (57.7%) had an anti-HBs level of <10 mIU/ml, while 1764 (42.3%) participants had protective levels of anti-HBs (≥10 mIU/ml) that indicated continuous protection 5 ~ 15 years after the primary series of hepatitis B vaccination in infancy, with a GMT of 163.3 mIU/ml (95% CI: 135.3–191.4 mIU/ml). Among the 1764 individuals with a seroprotective level of anti-HBs, 28.2% had a low response (10 ≤ anti-HBs < 100 mIU/ml), 11.2% had a moderate response (100 ≤ anti-HBs < 1000 mIU/ml), and 2.9% had a high response (anti-HBs ≥ 1000 mIU/ml). The overall GMTs did not differ significantly by age (P > .05) ().

Table 2. PSR and GMT distributions stratified by age before the booster vaccination

Anamnestic response after the booster dose

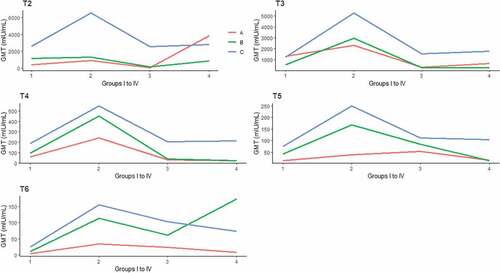

A total of 412, 1295, 377, and 242 individuals accepted the administration of booster vaccination in groups I to IV, respectively (). At 1 month after dose-1, 408 participants were available for follow-up in group I, and among them, 91.7% showed an anamnestic response, with a 776.9-fold increase in the GMT, ranging from 2.7 mIU/ml to 2097.6 mIU/ml. A total of 1271 participants were available for follow-up in group II, and 92.8% showed an anamnestic response, with a 1747.7-fold increase in the GMT, at 4194.5 mIU/ml. A total of 374 participants were available for follow-up in group III, and 91.4% showed an anamnestic response, with a GMT ranging from 2.5 mIU/ml to 1475.9 mIU/ml. A total of 238 participants were available for follow-up in group IV, and 93.7% showed an anamnestic response, with GMT of 2504.4 mIU/ml, which was 894.4 times higher than the pre-booster GMT of 2.8 mIU/ml. In group II, the GMT of the subjects was significantly higher than the GMTs of the subjects in the other three groups (P < .001) (, ). At 1 month after dose-3, 397, 1218, 377 and 226 participants were available for follow-up in groups I, II, III and IV, respectively. Among groups I to IV, 99.2%, 99.7%, 99.5% and 100% showed an anamnestic response, with GMTs of 1063.9, 4163.9, 1014.9 and 1343.3 mIU/ml, respectively. Similar to the first booster dose response, the GMT of group II was significantly higher than the GMTs of the other three groups (P < .001) (, ).

Table 3. Anti-HBs titer distribution at 5 time points

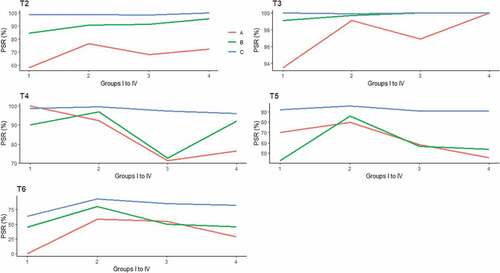

According to the pre-booster anti-HBs titers, the subjects were further classified into groups A, B, and C. We found that the subjects in group C showed seropositive rates of 98.8%, 98.9%, 98.6% and 100% after the first dose of the booster vaccine in groups I to IV, respectively. The corresponding GMTs were 2606.3, 6519.6, 2530.9 and 2801.4 mIU/mL in groups I to IV, respectively. The subjects in group B showed responses of 84.6%, 90.8%, 91.3% and 95.6% in groups I to IV, respectively. All the subjects in group A showed seropositive rates below 80% in the four groups. There were significant differences between different levels of pre-booster anti-HBs titers among each group (P < .001). At 1 month after dose-3, all the participants showed seropositive rate of nearly 100% (, ).

Table 4. Changes in PSR and GMTs stratified by pre-booster anti-HBs titers and different doses at the five time points

Long-term protection after the booster dose

After the full three doses of booster vaccines, follow-up for protection persistence was investigated. One year later, 252, 787, 285 and 119 participants in the four groups, respectively, were contacted. Among group I, the seropositive rate was 2.8% lower than that at 1 month after dose-3 (96.4% vs. 99.2%, P > .05), with corresponding GMTs decreasing from 1063.9 to 156.3 mIU/ml (P < .001). In group II, the seropositive rate was 97.6%, with a GMT of 466.9 mIU/ml. In group III, the PSR was 86.0%, with a corresponding GMT of 129.2 mIU/ml. In group IV, 92.4% of the participants had a protective level of anti-HBs, with a GMT of 154.0 mIU/ml. In group II, the GMT of the subjects was significantly higher than the GMT of the subjects in the other three groups (P < .001) (, ). Participants in group C still showed >90% seropositive rates and >100 mIU/mL in the corresponding GMTs in all four groups. The participants in group B still showed >90% seropositive rates, except for those in group III, and <100 mIU/mL of the corresponding GMTs, except for those in group II. The GMT in group A was significantly lower than the GMTs in groups B and C in groups II to IV (P < .001) ( and , ).

Figure 3. Long term investigation on genometric mean titers after booster vaccination among the four groups according to the baseline anti-HBs titers

At 5 years after dose-3, the seropositive rate in group I was 80.0%, with a GMT of 61.8 mIU/ml. In groups II to IV, the seropositive rates and GMTs were 90.3% and 190.6 mIU/ml, 75.1% and 89.8 mIU/ml, 75.4% and 75.9 mIU/ml, respectively. In group II, the GMT of the subjects was significantly higher than the GMTs of the subjects in the other three groups (P < .01) (). Similar to the changes at 1 year after dose-3, participants in group C still showed >90% seropositive rates in all four groups and >100 mIU/mL of the corresponding GMTs, except for those in group I. In group A, the seropositive rates were approximately 50%, except in group I and group II, and in group B, the seropositive rates were approximately 50%, except in group II. The GMT in group A was significantly lower than the GMTs in groups B and C in groups II and III (P < .001) ( and , and ).

At 8 years after dose-3, the seropositive rate in group I further decreased to 51.4%, with a corresponding GMT of 19.4 mIU/ml. A total of 83.4% of the subjects in group II still showed good protective levels of anti-HBs, and the average GMT was 122.6 mIU/ml. In group III, 70.7% of the participants had seroprotective anti-HBs, with a GMT of 72.6 mIU/ml, and in group IV, the rate was 66.7%, with a GMT of 87.6 mIU/ml. The GMT of the subjects in group II was significantly higher than the GMTs of the subjects in groups I (P < .001) and III (P < .05) (). In group I, the results showed seropositive rates of 0, 44.4% and 63.6% in groups A, B and C, respectively. The GMTs decreased below 10 mIU/mL in group A and B except group C (P > .05). In group II to IV, only the subjects in group C still showed >80% of seropositive rates. However, group C showed >100 mIU/mL in the corresponding GMTs in group II and III except group IV. There were significant differences of seropositive rate between the subjects with different pre-booster anti-HBs titers from group I to IV (P < .05). In addition, significant differences were for GMT between the subjects with different pre-booster anti-HBs titers in group II and III(P < .001) ( and , ).

Comparison of antibody titers at the 5 time points

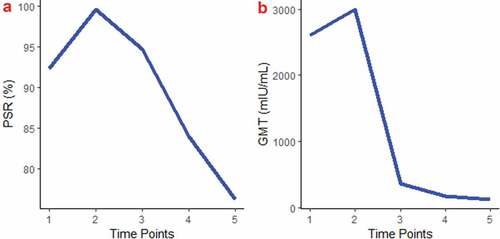

One month after the first dose and one month, one year, 5 years and 8 years after the third dose, the anti-HBs positive rates were 92.4%, 99.6%, 94.7%, 84.0% and 76.3%, respectively. The total anti-HBs positive rate increased by 7.2% after three full doses, and decreased by 4.9%, 15.6% and 23.3% after 1 year, 5 years and 8 years, respectively (P < .001) (, ).

Figure 4. Comparison of the total anti-HBs PSR (A) and GMTs (B) at 5 time points. Five time points: 1: 1 month after the dose-1; 2: 1 month after the dose-3; 3: 1 year after the dose-3; 4: 5 years after the dose-3; 5: 8 years after the dose-3

The total anti-HBs GMTs had a trend similar to the anti-HBs positive rates during the 8-year follow-up. The GMTs were 2603.5, 2992.3, 361.0, 176.2 and 128.1 mIU/ml at one month after the first dose and one month, one year, 5 years and 8 years after the third dose, respectively (P < .001). (, ).

Discussion

Our results showed that the HBsAg positive rate of children with primary vaccination was 1.1% and the anti-HBc positive rate was 4.1% five years later; these values were lower than the 7% anti-HBc positive rate and 2% HBsAg positive rate in Ping-Ing Lee’s study.Citation11 The reason may be that the infants’ mothers were negative for HBeAg in our study, while the mothers were positive for HBeAg in Ping-Ing Lee’s study, putting the children at higher risk for HBV infection. A study in Italy found that the anti-HBc positive rate of children born to HBsAg-negative mothers reached 2.7% 18 years after primary vaccination;Citation12 this was lower than the positive anti-HBc rate in our study. One possible reason is that Italy belongs to the low-intermediate region and China belongs to the high-intermediate region.Citation5 However, the sample in the Italy study was small (n = 112). A large-scale study in China (n = 5052) demonstrated that 13–23 years after primary vaccination, the anti-HBc positive rate of children was 6.39%, and the HBsAg positive rate was 1.58%, which is higher than that in the children in our study.Citation13 In addition, a study by Dr. Qu in China found that an adolescent booster vaccination against hepatitis B could decrease HBV breakthrough infection in high-risk adults whose mother was HBsAg positive during infancy.Citation14 All of the above studies suggest that a booster vaccination for protection against HBV is urgently needed.

Although some researchers favored a booster vaccination for hepatitis B, the optimal booster vaccination regimen has proved inconclusive so far. According to previous studies, a 3-dose 0-1-6-month booster protocol could elicit seroconversion rates of 95.3%–100%, implying that the 0-1-6-month booster protocol provides high anti-HBs seroconversion.Citation15,Citation16 In our study, 99.6% of the subjects with the same 3-dose booster protocol also developed anti-HBs positivity. Hence, the 0-1-6-month protocol could be an appropriate protocol for booster vaccination. A booster dose of 5 μg, 10 μg, 20 μg, 60 μg of hepatitis B vaccine and HAB vaccine was implemented in the majority of hepatitis B booster investigations.Citation16-22 Although all of the studies identified a good anamnestic response after the booster dose, most of them had short-term follow-up periods rather than long-term follow-up periods to monitor the booster vaccination efficacy. Consequently, this 8-year prospective cohort study could be the first long-term effect study on booster vaccinations for hepatitis B in children who received primary vaccination in infancy.

In this study, we found that 76.3% of subjects still had protective anti-HB titers, with a mean GMT of 128.1 mIU/mL after 8 years of follow-up. Wu Z et al.Citation23 observed that 91.05% of subjects still had protective anti-HBs titers after 5 years of booster vaccination. Lu S et al.Citation24 reported that 73.8% of participants had protective anti-HBs levels five years after booster vaccination, and McMahon et al.Citation25 found that 81.0% of participants had anti-HBs levels above 10 mIU/ml after one year of follow-up. Our result was different from the reported findings, which could be explained by multiple factors, including the different time period of follow-up, the different composition of the subjects and the different doses of hepatitis B vaccines. The results of group II were similar to those of Wu Z et al. for the same period of follow-up and dose of hepatitis B vaccines.

After one booster dose of hepatitis B vaccine, all four groups showed good anamnestic responses, with over 4-fold increase in anti-HBs antibody concentrations after the challenge dose in subjects who were seronegative previously. After dose 3, all four groups still maintained good anamnestic responses. The rate of increase was higher than those in other findings.Citation16-26,Citation26,Citation27 Possible reasons may be as follows. Firstly, most of the subjects received only one challenge dose of hepatitis B vaccine.Citation16-21 Secondly, the dosage of revaccination was different, ranging from 0 to 0-1-month.Citation16-26 Thirdly, HBsAg endemicity may be one influencing factor as China still belongs to higher intermediate area.Citation5 Fourthly, the primary regimen was different. For instance, infant vaccination regimen was first week, 1–3 months, 6–9 months in the study by Norrozi M.Citation21 Others were 3, 5, 11 or 3, 5, 11–12 months.Citation17,Citation19 In addition, when comparing the GMTs among the four groups, the 10 μg hepatitis B vaccine achieved the best efficacy over time, which indicates that the 10 μg hepatitis B vaccine is suitable for booster vaccination with the 0-1-6-month protocol.

When the participants were split into groups A, B and C, we observed changes in anti-HBs antibodies over the 8-year follow-up after a 3-dose revaccination. We found that 1-dose revaccination could elicit robust and functional antibody responses in group B and C, while a serial 3-dose revaccination could elicit robust and functional antibody responses in group A. However, 8 years later, the protective anti-HBs titer only persisted in group C. The differences were significant among the groups with high anti-HBs titers in group C, which may indicate that there was no need for a second serial 3-dose booster vaccine in group C. One dose of revaccination maybe enough for children in group C with for their infancy maintaining good immune memory. In group A, 30–40% of the children did not elicit a robust response after the first dose of the booster vaccination, which suggests that more doses are needed for protection. This finding was consistent with previous studies. Spradling et al.Citation28 observed that 18- to 23-year-old subjects with pre-booster anti-HBs levels of 1 to 9 mIU/ml produced a better response to the booster dose than those with levels of 0 mIU/ml, indicating that the immune memory persisted even if the detectable anti-HBs was below 10 mIU/ml after the primary vaccination in the past. Federica Chiara et al.Citation29 found that pre-booster antibody titers of ≥2 mIU/mL may predict an anamnestic response to revaccination, and pre-booster levels of 0.1 mIU/mL tended to predict non-responders that may require a challenge vaccination. The existence of immune memory is reflected by the ability to elicit an anamnestic response to a booster dose. Based on the above studies and this theory, anti-HBs antibody levels below 0.1 mIU/ml could not elicit an anamnestic response to a booster dose without relatively long persistence. In addition, one dose of 5 μg, 10 μg, 20 μg HBV vaccines or HAB vaccines could not elicit anamnestic response in our study (Supplementary Table1). Although they could get good response for 0-1-6-month schedule, 5 year or 8 year later, the protective anti-HBs titer decreased dramatically, meriting further study.

Some limitations of our study should be taken into account. First, the rate of loss to follow-up was high, and we found that children aged 13–15 years accounted for the majority of the lost subjects (data not shown). We clustered subjects based on school enrollment; however, with the passage of time, some students graduated from their initial school and attended a new school outside of the research districts. Hence, there was a small sample size in this study, perhaps further affecting the reliability. Second, the primary hepatitis B vaccination efficacy data was unavailable to us, so we could not differentiate our results from the possibility of waning of antibodies over time and negative responses to primary immunization. Another limitation of this study was that the frequent rejection of blood sample collection over a short period of time caused a gap in data after the second booster dose.

The strengths of the study included exploration of the seroprevalence of a relatively large sample of children at 5–15 years old, with multiple vaccination dosages, and different baseline GMTs pre-booster. There has been no study to include an 8-year follow-up after the booster vaccination among children with full primary HBV vaccination.

Conclusions

In summary, all doses of the HBV vaccine elicited robust and functional antibody responses for 1 year, and the 10 μg HBV vaccine may elicit a robust response and persist for 8 years or longer; a 3-dose 10 μg hepatitis B vaccine is recommended as a booster among those with undetectable anti-HBs levels, particularly in children with 0.1 to <1 mIU/ml anti-HBs titers. Additionally, one booster vaccination maybe suitable for children with 1 to <10 mIU/ml anti-HBs titers.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.3 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the children and parents who volunteered to participate in this study. We appreciate the support of the staff from the Centres for Diseases Control and Prevention in Yu-Huan, Long-Quan and Kai-Hua Counties of Zhejiang Province.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1738169.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ott JJ, Horn J, Krause G, Mikolajczyk RT. Time trends of chronic HBV infection over prior decades-A global analysis. J Hepatol. 2017;66:48–54. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.08.013.

- WHO. Media centre-hepatitis B-fact sheet; 2017 Jul. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/.

- Hatzakis A, Van Damme P, Alcorn K, Gore C, Benazzouz M, Berkane S, Buti M, Carballo M, Cortes Martins H, Deuffic-Burban S, et al. The state of hepatitis B and C in the Mediterranean and Balkan countries: report from a summit conference. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20(suppl 2):1–20. doi:10.1111/jvh.2013.20.issue-s2.

- Trépo C, Chan HLY, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014;384:2053–63. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8.

- Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:1546–55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X.

- Bureau of disease prevention and control of Ministry of health, Chinese Center for disease control and prevention. Sero-epidemiologicalsurvey of hepatitis B among national population. Beijing (China): People’s Medical Press; 2011.

- Qiu Y, Ren J, Yao J. Healthy adult vaccination: an urgent need to prevent hepatitis B in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(3):773–78. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1086519.

- Cui F, Shen L, Li L, Wang H, Wang F, Bi S, Liu J, Zhang G, Wang F, Zheng H, et al. Prevention of chronic hepatitis B after 3 decades of escalating vaccination policy, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(5):765–72. doi:10.3201/eid2305.161477.

- Kim YJ, Li P, Hong JM, Ryu KH, Nam E, Chang MS. A single center analysis of the positivity of hepatitis B antibody after neonatal vaccination program in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:810–16. doi:10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.810.

- Alssamei FAA, Al-Sonboli NA, Alkumaim FA, Alsayaad NS, Al-Ahdal MS, Higazi TB, Elagib AA. Assessment of immunization to hepatitis B vaccine among children under five years in rural areas of Taiz, Yemen. Hepat Res Treat. 2017;2017(4):1–6. doi:10.1155/2017/2131627.

- Lee P-I, Lee C-Y, Huang L-M, Chang MH. Long-term efficacy of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and risk of natural infection in infants born to mothers with hepatitis B e antigen. J Pediatr. 1995;126:716–21. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(95)70398-5.

- Da Villa G, Roman L, Sepe A, Iorio R, Paribello N, Zappa A, Zanetti AR. Impact of hepatitis B vaccination in a highly endemic area of south Italy and long-term duration of anti-HBs antibody in two cohorts of vaccinated individuals. Vaccine. 2007;25:3133–36. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.044.

- Wang F, Shen L, Cui F, Zhang S, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Liang X, Wang F, Bi S. The long-term efficacy, 13–23 years, of a plasma-derived hepatitis B vaccine in highly endemic areas in China. Vaccine. 2015;33:2704–09. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.064.

- Wang YT, Chen TY, Lu -L-L, Wang M, Wang D, Yao H, Fan C, Qi J, Zhang Y, Qu C, et al. Adolescent booster with hepatitis B virus vaccines decreases HBV infection in high-risk adults. Vaccine. 2017;35(7):1064–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.062.

- Su FH, Chu FY, Bai CH, Lin YS, Hsueh YM, Sung FC, Yeh CC. Efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine boosters among neonatally vaccinated university freshmen in Taiwan. J Hepatol. 2013;58:684–89. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.036. PMID:23207141.

- Wang Z-Z, Gao Y-H, Wei L, Jin C-D, Zeng Y, Yan L, Ding F, Li T, Liu X-E, Zhuang H, et al. Long-term persistence in protection and response to a hepatitis B vaccine booster among adolescents immunized in infancy in the western region of China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):909–15. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1250990.

- Zanetti A, Desole MG, Romanò L, d’Alessandro A, Conversano M, Ferrera G, Panico MG, Tomasi A, Zoppi G, Zuliani M, et al. Safety and immune response to a challenge dose of hepatitis B vaccine in healthy children primed 10 years earlier with hexavalent vaccines in a 3, 5, 11-month schedule: an open-label, controlled, multicentre trial in Italy. Vaccine. 2017;35:4034–40. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.047.

- Behre U, Van Der Meeren O, Crasta P, Hanssens L, Mesaros N. Lasting immune memory against hepatitis B in 12–13-year-old adolescents previously vaccinated with 4 doses of hexavalent DTPa-HBV-IPV/Hib vaccine in infancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;12(11):2916–20. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016.1202388.

- Avdicova M, Crasta PD, Hardt K, Kovac M. Lasting immune memory against hepatitis B following challenge 10–11 years after primary vaccination with either three doses of hexavalent DTPa-HBV-IPV/Hib or monovalent hepatitis B vaccine at 3, 5 a 11–12 months of age. Vaccine. 2015;33:2727–33. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.070.

- Van Der Meeren O, Behre U, Crasta P. Immunity to hepatitis B persists in adolescents 15–16 years of age vaccinated in infancy with three doses of hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccine. 2016;34:2745–49. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.013.

- Norrozi M, Azami A, Sarraf-neduad A, Chitsaz H, Rahmati N. Persistence of anti-HBs antibody and immune memory to hepatitis B vaccine, 18 years after infantile vaccination in students of Tehran University. Res Med. 2016;40(1):36–41.

- Spada E, Roman L, Me T, Zuccaro O, Paladini S, Chironna M, Coppola RC, Cuccia M, Mangione R, Marrone F, et al. Hepatitis B immunity in teenagers vaccinated as infants: an Italian 17-year follow-up study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:680–86. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12591.

- Wu Z, Yao J, Bao H, Lu S, Li J, Yang L, Jiang Z, Ren J, Xu K, Ruan B, et al. The effects of booster vaccination of hepatitis B vaccine on children 5–15 years after primary immunization: A 5-year follow-up study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(5):1251–56. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1426419.

- Lu S, Ren J, Li Q, Jiang Z, Chen Y, Xu K, Ruan B, Yang S, Xie T, Yang L, et al. Effects of hepatitis B vaccine boosters on anti-HBs- negative children after primary immunization. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):903–08. doi:10.1080/21645515.2016. 1260794. PMID:27905821.

- McMahon BJ, Dentinger CM, Bruden D, Zanis C, Peters H, Hurlburt D, Bulkow L, Fiore AE, Bell BP, Hennessy TW. Antibody levels and protection after hepatitis B vaccine: results of a 22-year follow-up study and response to a booster dose. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(9):1390–96. doi:10.1086/606119. PMID:19785526.

- Aypak C, Yüce A, Yıkılkan H, Görpelioğlu S. Persistence of protection of hepatitis B vaccine and response to booster immunization in 2- to 12-year-old children. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1761–66. doi:10.1007/s00431-012-1815-4.

- Yao J, Ren J, Shen L, Chen Y, Liang X, Cui F, Li Q, Jiang Z, Wang F. The effects of booster vaccination of hepatitis B vaccine on anti-HBs negative children 11–15 years after primary vaccination. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(10):1055–59. doi:10.4161/hv.7.10.15990.

- Spradling PR, Xing J, Williams R, Masunu-Faleafaga Y, Dulski T, Mahamud A, Drobeniuc J, Teshale EH. Immunity to hepatitis B virus infection two decades after implementation of universal infant hepatitis B vaccination: the association of detectable residual antibody and response to a single hepatitis B vaccine challenge dose. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20:559–61. doi:10.1128/CVI.00694-12. PMID:23408522.

- Chiara F, Bartolucci GB, Cattai M, Piazza A, Nicolli A, Buja A, Trevisan A. Hepatitis B vaccination of adolescents: significance of non-protective antibodies. Vaccine. 2013;32(1):62–68. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.074. PMID:24188755.