ABSTRACT

During the 20th century, the discovery of modern vaccines and ensuing mass vaccination dramatically decreased the incidence of many infectious diseases and in some cases eliminated them. Despite this, we are now witnessing a decrease in vaccine confidence that threatens to reverse the progress made. Considering the different extents of low vaccine confidence in different countries of the world, both developed and developing, we aim to contribute to the discussion of the reasons for this, and to propose some viable scientific solutions to build or help restore vaccine confidence worldwide.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

What is the context?

Despite availability and benefits of vaccines, coverage is not always optimal.

This may be partly attributed to vaccine hesitancy, a global health threat defined as the delay in acceptance or the refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccines and vaccination services.

What is new?

Loss of trust is a key determinant to low vaccine confidence.

Misinformation and misconceptions about vaccine safety, about diseases and their transmissions, and mistrust in science appear to be among the most common reasons for vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccine hesitancy appears to contribute to suboptimal vaccination coverage, which may lead to disease outbreaks, increased health expenditures, and needless deaths.

What is the impact?

We acknowledge the important role played by healthcare practitioners and the media in individuals’ decisions. However, vaccine hesitancy has consequences beyond the individual.

To address this important problem, we believe in a collective approach to build trust. Key success factors lie in transparency on risks and benefits and access to scientifically valid information.

Introduction

Vaccination is one of the most important success stories of modern-day medicine, averting over 5 million deaths worldwide every year from 2010 to 2015. During the 20th century, mass vaccination resulted in dramatic decreases in the incidence and morbidity of many infectious diseases. In most countries, a number of infectious diseases have been mitigated and, in some cases, have been eliminated due to routine vaccination.1,Citation2 One human disease – smallpox – has been completely eradicated by the widespread use of specific vaccines, and poliomyelitis is on track to be the next.Citation1,Citation3 Every year vaccination prevents 2.7 million cases of measles, 2 million cases of neonatal tetanus, 1 million cases of pertussis, 600,000 cases of paralytic poliomyelitis and 300,000 cases of diphtheria.Citation3

In addition to directly preventing disease in vaccinees, vaccination indirectly reduces the likelihood of disease transmission. Unvaccinated individuals have a reduced risk of contracting the infection once a critically high proportion of the population has been immunized, a phenomenon known as herd immunity.Citation4,Citation5 Vaccination can also reduce antibiotic use,Citation6,Citation7 thereby having a direct effect on antimicrobial resistance, as shown by the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines that have substantially reduced the incidence of disease caused by antibiotic-resistant strains. In addition, experience with rotavirus and pneumococcal diseases has further shown that effective use of vaccines can reduce diagnostic and treatment costs, numbers of ambulatory care visits, medical interventions, and hospitalizations.Citation8–13 It can also prevent nosocomial infections, and, in other cases, indirectly prevent some types of cancer.Citation14 Dual vaccination with pneumococcal and influenza vaccines protects older adults with chronic illness from hospitalization for certain respiratory, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular diseases, thereby reducing the risk of intensive care unit admission and death.Citation15,Citation16

In addition to being effective in reducing disease prevalence and associated mortality, vaccination provides the benefit of averting costs of medical care. Ozawa et al.Citation17 examined the return on investment associated with achieving projected coverage levels for 10 antigens in 94 countries. They estimated that universal vaccination would yield a net return about 16 times greater than costs over the decade.Citation17 A further positive outcome of vaccination is the reduced workload for healthcare providers (HCPs) resulting from averted illness. This is particularly important in developing countries with a much lower density of HCPs, who are often overwhelmed by the number of patients requiring their attention. The assessment of the value of vaccines and vaccination needs to go beyond the direct impact on health and healthcare by considering the wider impact on societal and household economic well-being.Citation18

Because of all these proven benefits and the well understood importance of vaccination, suitable vaccination programs have been implemented around the world. Despite this, many countries still have vaccination coverage rates below that stipulated by the World Health Organization (WHO). These programs have therefore been focused on assuring that high vaccination coverage is achieved in all regions of the world to grant everyone protection. Unfortunately, these efforts are being undermined by a growing anti-vaccination movement. The hesitancy of individuals to have themselves and their children vaccinated can have a profound impact not only on their own health, but also on public health in general. Indeed, some vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) have reemerged in both developed and developing countries.Citation19–21 The resurgence of infectious diseases that are currently under control or have already been eradicated is a real danger.Citation22 Therefore vaccine hesitancy (VH) has been included in the WHO list of global health threats for 2019.Citation23

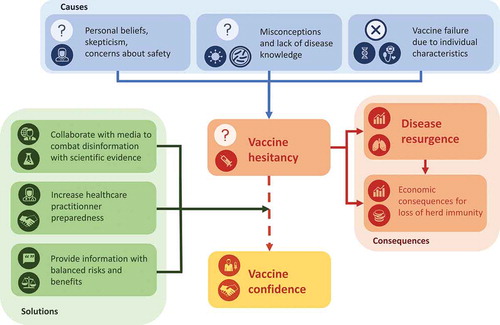

VH is defined by the WHO Vaccine Hesitancy Working Group as the ‘delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccine services’, and is a complex behavioral phenomenon ‘influenced by factors such as complacency, convenience and confidence’. VH is context-specific, varying across time, vaccines, places, and populations within a place.Citation24 Hence, a considerable number of children have delayed vaccination secondary to a wide range of causes.Citation25 With a focus on childhood vaccination, the present article aims to contribute to the discussion on causes and implications of the low vaccine confidence in developed and developing countries and to propose viable evidence-based solutions to improve vaccine confidence ().

Current situation and grounds for low vaccine confidence

Misinformation and hoaxes

Misinformation and lack of access to balanced and accurate information is a major contributor to low vaccine confidence. The impact of misinformation has grown with the easy and rapid proliferation of unfounded and invalid information through mass communication media.Citation26–29 In developed countries, the internet and social media have played a central role in the advancement of anti-vaccination movements and in shaping vaccination decision-making.Citation26,Citation28,Citation30 An analysis of vaccine criticism on the internet,Citation31 found that websites critical of vaccines argue that vaccines cause illness, claim conventional medicine is wrong, and make emotional appeals and allegations about conspiracies, civil liberty violations, totalitarianism, and immorality, whilst encouraging alternative medicine.Citation31 In a recent commentary, Heidi J Larson, the director of the Vaccine Confidence Project at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, stated that there was a ‘deluge’ of misinformation on social media that ‘should be recognized as a global public-health threat’.Citation32

Misinformation about vaccines abounds across all settings. The mode of propagation may differ, but fabricated information (hoaxes) about vaccines may gain traction when it is spread by opinion leaders. For example, in Cameroon, in 1990, one such rumor was spread that a tetanus vaccine was used to sterilize girls and women.Citation33 Five years later, vaccination rates against tetanus declined to as low as only 13%.Citation33 In Nigeria, in 2003, rumors that an oral polio vaccine (OPV) was an American conspiracy to sterilize Muslim girls and spread human immunodeficiency virus resulted in the suspension of OPV use in five northern Nigerian states.Citation34 Consequently, wild poliovirus cases in the country increased fivefold between 2002 and 2006, causing a nationwide epidemic.Citation34 Moreover, the Nigerian strains of poliovirus were transmitted across Africa and beyond and re-infected previously polio-free countries.Citation34,Citation35 In both cases, the rumors were endorsed by local opinion leaders.Citation33,Citation35 Over 40% of the worldwide wild polio virus cases recorded in 2011 and 2012 occurred in the common epidemiological block of Pakistan and Afghanistan.Citation36 Pakistani parents who had refused OPV in a region with nine annual OPV campaigns attributed their refusal mainly to the perception that the vaccine was associated with birth control and disapproval of religious leaders.Citation36 Pakistan and Afghanistan are the only two countries where polio has still not been eradicated.Citation37–42

Loss of trust and risk communication challenges

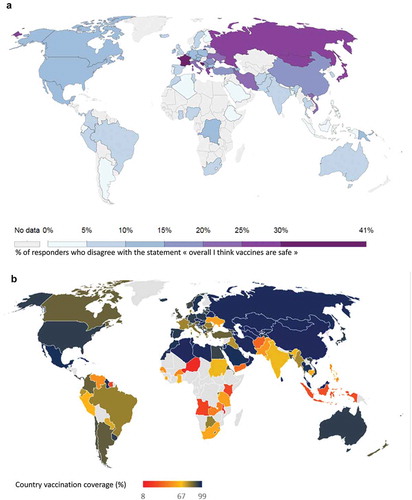

Several unfortunate events have negatively influenced public opinion and trust in vaccination and vaccine safety (), both in developped and developing countries, as exemplified below. When vaccine safety issues occur, they can be amplified and misrepresented leading to scaremongering behaviors and misinformation on social media. Furthermore, sub-optimal handling of difficult situations may decrease vaccine confidence and thereby adversely affect vaccination programs.

Figure 2. Perception of vaccine safety and measles vaccination coverage worldwide in 2015

In developing countries, such as Pakistan, polio eradication has been consistently undermined not only by religious extremism spreading rumors claiming that the vaccination is part of a Western conspiracy to sterilize Muslim persons, but also by the public’s loss of trust in the vaccination campaigns.Citation36,Citation38,Citation39 This loss of trust was fueled by a 2011 CIA plot that used a vaccination campaign to track down Osama bin Laden. As a result, health workers and vaccinator team members have been killed in numerous attacks from 2016 to 2019.Citation40–42

Also in developed countries, such as Japan, uncertainty and mistrust was triggered by the health authorities ambiguous choice to suspend the recommendation for routine human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination following allegations of adverse effects, while allowing the voluntary vaccination.Citation46,Citation47 A year later, the authorities concluded that the adverse reactions were not causally related to the HPV vaccine.Citation46,Citation48 However, they did not revoke the suspension of routine recommendation, thus exacerbating public confusion and uncertainty. While this was happening, unverified information spread through online media which reached and influenced a wider, worldwide audience.Citation46 Deaths from cervical cancer have increased by 9.6% in Japan in the past 10 years, and the HPV vaccination rate among girls eligible for vaccination dropped from 70% in 2013 to <1% in 2014.Citation48,Citation49 Still today, the Japanese health authorities have not resumed their recommendation for HPV vaccination. In Europe, public trust in the authorities was challenged and low adherence to influenza vaccination campaigns was recorded following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.Citation50,Citation51 The influenza outbreak had far fewer consequences than initially anticipated while the national budgets spent were considered by the Council of Europe to be disproportionate and unjustified.Citation51,Citation52 Consequently, the definition for pandemic used by the WHO was subject to public controversy, and received wide-spread media coverage. Public trust in the authorities was challenged and low adherence to subsequent influenza vaccination campaigns was recorded.Citation50,Citation51

HCP involvement

HCPs are the most frequent source of information regarding vaccination, and the interaction between patients or their parents and HCPs is at the core of maintaining confidence in vaccination.Citation53–55 Not only the knowledge, but also the attitude of the HCPs, are important to convey trust. The investigators of a 2014 national United States (US) survey also suggested that high quality recommendations from HCPs encouraged vaccination-hesitant parents to accept vaccination.Citation56 However, only one-third of the parents participating in the survey had received such high quality recommendation on HPV vaccination, and half of the parents had not received any recommendation for HPV vaccination.Citation56 A 2015 systematic review of studies conducted in the US found that HCPs did not strongly endorse the need for vaccination in their communication with parents.Citation57 Vaccinated HCPs are more likely to recommend vaccination to their patients than unvaccinated colleagues (57.5% vs. 43.8%, P <.001).Citation58,Citation59 Yet, recent surveys indicate low influenza vaccination rates across settings among HCPs, with 27% in two university hospitals in Ankara, Turkey, and 47.6% for US HCPs working in settings where vaccination was not required, promoted, or offered on-site.Citation59,Citation60 Among HCPs, reasons for not recommending pneumococcal vaccination included lack of knowledge about vaccinations benefits, fears of adverse events, and doubts about efficacy and safety.Citation59 It was also shown that HCPs who are knowledgeable about vaccines were more confident and more likely to recommend vaccination.Citation58 Educational interventions aimed at improving HCP knowledge and communication about vaccination improved HCPs’ knowledge and the vaccine uptake of HCPs and their patients.Citation58,Citation61

Studies have shown, however, that HCPs’ knowledge about vaccination issues is variable and that training in vaccinology is poor or non-existent in medical curricula in many countries.Citation62 In a French hospital study, only 25% of HCPs were able to list correctly the three mandatory vaccines.Citation63 Similarly, only 12.9% of Greek HCPs correctly named the vaccines recommended for them by the Ministry of Health.Citation64 In an Australian hospital-based study, only 9.8% of HCPs were able to correctly identify the vaccines recommended for HCPs.Citation65

Complex dynamics of immunization

The ‘pathogen-host-vaccine’ triad can be complex. A small percentage of non-vaccinated persons are not infected during an outbreak while another small percentage of persons contract a disease despite being vaccinated against it. Therefore, some parents may question vaccine efficacy, but expecting 100% efficacy is not realistic. In rare instances, a vaccine may fail to mount the appropriate immune response, which may be due to handling errors,Citation66 or genetic determinants in the host or in the pathogen. Today, the mechanisms by which host and pathogen gene polymorphisms may influence immune responses to vaccines are better understood, but this complexity can be difficult to communicate (Supplement Text Box 1).Citation67,Citation103–112 Furthermore, the mitigation of severity and duration of the disease is an important benefit of routine vaccination. Therefore, although vaccines do not always produce a full immune response, they may nevertheless lessen disease symptoms, as seen with influenza, pertussis and rotavirus vaccines.Citation68–70 This protective effect should be emphasized, as it may not always have been fully appreciated by HCPs and the general population.Citation68

Healthism

An increasing number of parents in the developed world believe that a ‘natural lifestyle’ and better hygiene and sanitation will make diseases disappear and that acquiring immunity through having the disease is better. They describe children’s bodies as naturally perfect, and believe that the ways by which vaccines enter the body are unnatural. They thus feel capable of managing their children’s health without vaccines because of their closer-to-nature lifestyles.Citation71,Citation72 A significant proportion of such parents may be unaware of the severity of vaccine preventable diseases and their potential consequences.Citation71 Another key aspect relates to the use of complementary or alternative medicine instead of vaccines, and some practitioners (homeopaths, chiropractors, and naturopaths) have a negative view of vaccination and advise their clients accordingly.Citation73,Citation74

Skepticism toward science

The healthism attitude, but also the tendency to believe in conspiracy theories, might be explained by new patterns of behavior regarding scientific evidence: belief in science is decreasing and the willingness to accept nonscientific approaches is increasing all around the world.Citation75 The postmodern era we are living in is going through ‘an assault on science’ – as quoted by Kuntz.Citation76 In postmodernist thinking, scientists are not to be trusted and therefore people should control scientific research. Denialism has also been proposed as a term that might describe these attitudes.Citation77 Denialists might put forward fake experts to support their theories, thus trying to discredit the work of established experts and researches.Citation77 They also make selective use of flaws in isolated papers, and in doing so spread disbelief in all scientific data.Citation77 A study examining attitudes toward society members among vaccine-skeptics and non-skeptics found that vaccine skeptics are less likely to consider others as equals.Citation78 According to the authors, their finding should be taken into consideration when designing communication strategies for vaccines.Citation78

Consequences of low vaccine confidence

Medical consequences of low vaccine confidence

In a community, the incidence of VPDs is directly related to the number of unvaccinated persons.Citation79 The reemergence of infectious diseases such as measles and pertussis has been linked, among other factors, to an increase in the number of parents refusing to have their children vaccinated.Citation79 There is also a significant correlation between infectious diseases outbreaks and geographic aggregation of vaccination refusals.Citation79 Ultimately, vaccination refusal not only increases the likelihood of contracting infectious diseases for the unvaccinated individual but for the whole community as well.Citation79 For this reason, there is a need to reach a certain proportion of vaccinated individuals in the target population to prevent the occurrence of outbreaks.Citation1 Even a modest gap in vaccination protection will offer an opportunity for the infectious disease agent to proliferate and cause outbreaks.Citation80,Citation81

The decline in infectious disease incidence due to vaccination has created the impression that the diseases are becoming scarce and less harmful.Citation82 As evidence of this, the American Academy of Pediatrics reported that the percentage of parents who refused some vaccines almost doubled between 2006 and 2013, and that about 1 in 5 parents requested to delay vaccination.Citation83 In the case of pertussis for example, in many countries, fear of the consequences of the disease faded after achieving high vaccination rates over the years, and worries over vaccine safety gained attention.Citation82 This loss of vaccine confidence can be described as a ‘tragedy of the commons’, as it resulted in lowered vaccination rates, with consequent disease resurgence.Citation84 With respect to measles,Citation79,Citation85 in the Netherlands, a measles outbreak started in 2013, with most cases (91.7%) occurring in orthodox Protestants who opposed vaccination; almost all infected cases (96.5%) were unvaccinated.Citation86 In 2018, there were over 80,000 cases of measles in 47 European countries; 61% of patients required hospitalization and 72 died.Citation87 In early 2019, based on WHO data, measles case numbers were on the rise, with 40–700% increases reported in various regions.Citation88 2019 was also the year with the greatest number of measles cases in the history of the US since 1992: 1,282 cases (375 in 2018), mostly unvaccinated, in 31 states.Citation89

Economic consequences of low vaccine confidence

Vaccination is generally associated with cost savings. A study evaluating the measles national vaccination coverage among 29 European countries between 1998 and 2011 found that vaccination coverage and burden of disease had a significant negative correlation (−0.025, 95% confidence interval: −0.047 to −0.003).Citation90 The cost of measles therefore decreases with increasing vaccination rates. There was a societal cost savings of USD 13.5 billion in direct medical costs and USD 68.8 billion in total societal costs for the US society with routine childhood vaccination.Citation91,Citation92

Low vaccine confidence imposes a high economic burden on society as a whole, causing high direct healthcare costs, indirect productivity losses, and public health spending in the healthcare sector. Even small reductions in vaccination coverage have substantial public health and economic consequences.Citation80 It is estimated that a 5% reduction in measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination in the US would add a cost burden of USD 2.1 million to the annual public sector’s healthcare expenditures.Citation80

The unnecessary economic burden for society caused by low vaccine confidence was clearly shown by evaluating the economic burden of several past measles outbreaks.Citation93–97 In 2011, the US experienced 16 measles outbreaks and the total economic burden on public health institutions was estimated to be in the range of USD 2.7–5.3 million.Citation98 In 2008, a measles outbreak in San Diego, that originated from an intentionally unvaccinated seven-year-old boy, cost the community nearly USD 177,000, which included medical care provision to the confirmed cases, tracking of suspected cases, quarantining people, enhancing surveillance, and following up an infected infant and related contacts in Hawaii.Citation94,Citation99 In 2013, in New York, the largest measles outbreak since 1992 infected 58 mostly intentionally unvaccinated persons, and the direct cost for controlling the outbreak was nearly USD 400,000.Citation97 In Ethiopia, from October 2011 to April 2012, a measles outbreak caused seven deaths among >5,000 infected children.Citation100 The economic burden of this outbreak corresponded to over USD 750,000. The health sector cost for the treatment of each case was two times the national health expenditure per person in 2010.Citation100

Proposed solutions

There is no single intervention to restore public confidence in vaccination, especially across countries that have very diverse sociocultural, economic and geopolitical backgrounds. Nevertheless, different strategies have been formulated to encourage vaccination among individuals reluctant to receive vaccines and among parents concerned about the risk of vaccines causing their children harm. Medical associations, the pharmaceutical industry, health authorities on local, national, and international levels are responsible for improving or restoring vaccine confidence; and we discuss some of these strategies below.

Regaining trust

Provision of valid information

One of the main reasons people make decisions based on unfounded information on vaccines is lack of trust in the healthcare system, public health organizations, the vaccine as a product, and the vaccine provider.Citation101,Citation102,Citation113 Transparency about vaccine risks and benefits and increasing the pool of available material for public use is crucial in restoring and maintaining trust (, ). Access to credible information driven by scientific responsibility and integrity should be facilitated and ensured for the public, vaccine providers (HCPs, nurses, midwives), and health authority officials.

BOX 1. A model example of risk communication

The public should also be aware of the rigorous process in place for the scientific evaluation of vaccines, the strict regulatory requirements to obtain approval, life-cycle management, and the continuous assessment of the safety profile after approval.

The pharmaceutical industry could do more to address people’s concerns with information suited to different audiences, such as video summaries of scientific articles,Citation104 and plain language summaries of clinical trials.

International and cross-sector partnerships

Several different international collaborations are monitoring the status of vaccine confidence across the globe, including Regional Technical Advisory Groups on Immunization (RITAG), Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE), Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP) which are initiatives of the WHO; The Vaccine Confidence project; and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. They provide information and/or recommendations on issues such as lack of vaccine confidence. Such collaborative efforts could expand to the provision of technical advice on operational plans for implementation by each country’s government.Citation22 According to a report from the WHO-SAGE, interventions that are most successful in improving vaccine confidence are multi-component strategies, some of which could involve the collaboration of several different sectors. Multi-component interventions such as exposure to a community influencer (e.g., trained personnel or family/community members),Citation105 or attendance to parent meetings in addition to receiving an information leaflet,Citation106 could improve vaccine uptake in settings where initial vaccine confidence is low. Other effective interventions that involve cross-sector partnerships include the use of web pages with tailored messages, which may be effective in improving vaccine compliance among vaccine-hesitant parents,Citation107 or the use of a mathematical modeling approach to shape a message describing potential consequences of reduced vaccination uptake, which have an impact on improving mothers’ opinion of childhood vaccines.Citation108 Partnerships between health authorities on an international level with the education sector, social partners, and public and private healthcare sectors would optimize awareness-raising campaigns, produce modern tools to increase vaccine confidence, and provide support to poorer countries.

Use of the media

The role of the media – including the internet – need not be negative. First, media could provide valuable resources and tools to physicians helping them to engage with their patients with personalized information, which is more effective than non-tailored information in improving compliance with recommended health behaviors.Citation109 Furthermore, health authorities should be able to harness the power of social media and use it to monitor trends in public opinion and respond accordingly.Citation110,Citation111 Unfounded allegations should be countered with scientific evidence on the risks and benefits of vaccines.Citation112 Raising positive voices, potentially using community influencers,Citation105 and sharing a cross-sector unified message presenting vaccine acceptation as the social norm, while acknowledging and positively valuing those who do accept vaccination,Citation113 could help combat misinformation and the growing distrust in science. Moreover, the health authorities should take lessons from successful past uses of media (Box 1),Citation114,Citation115 and proactively prepare a media communication plan ready to be implemented in the event of a safety issue.Citation112 Such a plan should include preparedness of media-trained spokespersons, and development of different sets of information depending on the audience and the means of communication (i.e., tailor-made for radio, newspapers, television, or social media).Citation112 However, communication planning must not be limited to crisis management,Citation112 but should be ongoing, proactively providing messages directly targeting the most crucial public concerns, taking into account social and cultural characteristics as well as geographical location influences.Citation116

Increase HCP preparedness

An information exchange is required when recommending a vaccine to a patient or to a parent. During this process, the HCP has to explain the nature and purpose of vaccines, present the scientific evidence including the risks and benefits for the child and for the community. Transparency about VPDs, vaccines, testing, ingredients, potential side effects and funding reduces mistrust.

It is also important to communicate this information positively. Researchers have found that a presumptive approach (i.e., assuming parents will opt for vaccination), was more efficient in convincing parents to have their children vaccinated, rather than a participatory approach (i.e., asking open questions involving parental decision-making).Citation117,Citation118 Patients’ and parents’ questions should be answered, and their fears, preferences, and values should be respected, as well as their autonomy and freedom of choice.Citation119,Citation120 The information provided must be clear, reliable, and include the latest findings on VPDs, vaccine safety and efficacy from credible sources. To provide the evidence that is needed by the parents to make informed decisions without oversaturating them with information, it is important that HCPs develop their ability to listen to parents’ concerns and communicate clear and understandable messages. Such an approach is key in building trustful communication between parents and HCPs and is one of the principles of motivational interviewing.Citation120 Using motivational interviewing techniques, the parents will receive information from the HCPs tailored to their needs, which actually helps them in resolving ambivalence about accepting vaccination.Citation120

HCPs need support in fulfilling the requirements of this very important information process. HCPs with knowledge about the recommended vaccines and the respective VPDs are more likely to recommend vaccination.Citation58 Training courses on current knowledge and new developments regarding VPDs, vaccines, and related recommendations should be offered for HCPs at all levels of experience, from medical students to practicing physicians. The training should include techniques to manage difficult conversations with hesitant individuals.Citation58 Supplying HCPs with the communication tools to be used during this process is crucial. Moreover, as HCPs are often bound by time constrains, viable workload solutions should be implemented to allow the required time for the information exchange,Citation58 such as reimbursement of HCPs who vaccinate children with overdue routine childhood vaccinations schedules.Citation121,Citation122 Lastly, involving HCPs in the process of developing vaccination recommendations would improve their understanding and engagement in implementing them.Citation58

Conclusions

It seems there is a loss of trust in health authorities and science, also in the public and private health sectors, and rapid global sharing of misinformation are leading to an increase in the number of people questioning vaccines and sometimes delaying or refusing vaccination. Individual acceptance of vaccination depends on knowledge about the risks and benefits of vaccines, but also on more complex determinants such as cultural, religious, emotional, and social factors.Citation123,Citation124

Incorporating the progress and results of vaccine research into successful vaccination programs, and replacing misinformation with evidence-based communication is crucial in improving vaccine confidence and requires a multidisciplinary, cohesive, targeted, and managed approach. HCPs are the front-runners in the process of vaccination and should be well prepared with the appropriate knowledge to address decreased vaccine confidence. Respecting individuals’ beliefs and lifestyles while providing all scientifically founded information, including risks and benefits of vaccination, is fundamental in helping people understand the rationale and benefits of vaccination for both the individual and communities. The success of any vaccination strategy is determined by the people’s confidence in the vaccination system and their trust in health authorities; otherwise, vaccination strategies might become counterproductive.Citation111,Citation119 Strengthening of the vaccination system to maintain optimum vaccination rates in the long run, through education, legislation, regulation, supply chain improvements, and more, should be the priority for all parties involved in the provision of healthcare and is crucial to Sustainable Development Goals formulated for 2015–2030.Citation125

Abbreviations

| DTaP | = | diphtheria, tetanus toxoid, and acellular pertussis |

| DTP | = | diphtheria tetanus toxoids and pertussis |

| HCP | = | healthcare provider |

| HBV | = | hepatitis B virus |

| HLA | = | human leukocyte antigen |

| HPV | = | human papillomavirus |

| MMR | = | measles, mumps, and rubella |

| MS | = | multiple sclerosis |

| OPV | = | oral polio vaccine |

| RITAG | = | Regional Technical Advisory Groups on Immunization |

| PRR | = | pathogen recognition receptor |

| TLR | = | toll-like receptors |

| UK | = | the United Kingdom |

| US(A) | = | the United States (of America) |

| VH | = | vaccine hesitancy |

| VPD | = | vaccine-preventable disease |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

AD, MO, SO and SB are employed by the GSK group of companies and hold shares in the GSK group of companies. RA was an employee of the GSK group of companies and has now retired.

Contributorship

All authors participated to the conception and design of the manuscript. SB, AD and SO contributed to the acquisition of data. MO, RA, SB and SO participated to the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors revised the article critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval of the submitted version.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (79.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and manuscript coordination, on behalf of GSK. Amandine Radziejwoski coordinated the manuscript development and editorial support. Athanasia Benekou provided medical writing support.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1740559.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, Clemens J, Datta SK, John TJ, Lee BW, Lolekha S, Peltola H, Ruff TA, et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:140–46.

- Cohn A, Rodewald LE, Orenstein WA, Schuchat A. Immunization in the United States. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, Edwards KM, editors. Plotkin’s Vaccines. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier. 2018:1421–40.

- Remy V, Zollner Y, Heckmann U. Vaccination: the cornerstone of an efficient healthcare system. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2015;3:1.

- Fine P, Mulholland K, Scott J, Edmunds W. Community protection. In: Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit P, Edwards K editors. Plotkin’s vaccines. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier. 2018:1512–31.

- Scarbrough Lefebvre CD, Terlinden A, Standaert B. Dissecting the indirect effects caused by vaccines into the basic elements. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:2142–57.

- Palmu A, Jokinen J, Nieminen H, Rinta-Kokko H, Ruokokoski E, Puumalainen T, Borys D, Lommel P, Traskine M, Moreira M, et al. Effect of pneumococcal Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV10) on outpatient antimicrobial purchases: a double-blind, cluster randomised phase 3-4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:205–12.

- Klugman KP, Black S. Impact of existing vaccines in reducing antibiotic resistance: primary and secondary effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:12896–901.

- Hungerford D, Vivancos R, Read JM, Iturriza-Gomicronmara M, French N, Cunliffe NA. Rotavirus vaccine impact and socioeconomic deprivation: an interrupted time-series analysis of gastrointestinal disease outcomes across primary and secondary care in the UK. BMC Med. 2018;16:10.

- Hansen Edwards C, de Blasio BF, Salamanca BV, Flem E. Re-evaluation of the cost-effectiveness and effects of childhood rotavirus vaccination in Norway. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183306.

- Atherly DE, Lewis KD, Tate J, Parashar UD, Rheingans RD. Projected health and economic impact of rotavirus vaccination in GAVI-eligible countries: 2011–2030. Vaccine. 2012;30:A7–14.

- Andrade AL, Afonso ET, Minamisava R, Bierrenbach AL, Cristo EB, Morais-Neto OL, Policena GM, Domingues C, Toscano CM. Direct and indirect impact of 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction on pneumonia hospitalizations and economic burden in all age-groups in Brazil: A time-series analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184204.

- Afonso ET, Minamisava R, Bierrenbach AL, Escalante JJ, Alencar AP, Domingues CM, Morais-Neto OL, Toscano CM, Andrade AL. Effect of 10-valent pneumococcal vaccine on pneumonia among children, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:589–97.

- Izu A, Solomon F, Nzenze SA, Mudau A, Zell E, O’Brien KL, Whitney CG, Verani J, Groome M, Madhi SA. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines and hospitalization of children for pneumonia: a time-series analysis, South Africa, 2006–2014. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:618–28.

- Largeron N, Levy P, Wasem J, Bresse X. Role of vaccination in the sustainability of healthcare systems. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2015;3:1.

- Hung I, Leung A, Chu D, Leung D, Cheung T, Chan C, Lam C, Liu S, Chu C, Ho P, et al. Prevention of acute myocardial infarction and stroke among elderly persons by dual pneumococcal and influenza vaccination: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1007–16.

- Ciszewski A. Cardioprotective effect of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Vaccine. 2018;36:202–06.

- Ozawa S, Clark S, Portnoy A, Grewal S, Brenzel L, Walker D. Return On Investment From Childhood Immunization In Low- And Middle-Income Countries, 2011–20. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:199–207.

- Chang AY, Riumallo-Herl C, Perales NA, Clark S, Clark A, Constenla D, Garske T, Jackson M, Jean K, Jit M, et al. The equity impact vaccines may have on averting deaths and medical impoverishment in developing countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37:316–24.

- Hotez P. America and Europe’s new normal: the return of vaccine-preventable diseases. Pediatr Res. 2019;85:912–14.

- Raslan R, El Sayegh S, Chams S, Chams N, Leone A, Hajj Hussein I. Re-emerging vaccine-preventable diseases in war-affected peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean region-an update. Front Public Health. 2017;5:283.

- Buliva E, Elhakim M, Tran Minh NN, Elkholy A, Mala P, Abubakar A, Emerging MS. Reemerging diseases in the World Health Organization (WHO) Eastern Mediterranean region-progress, challenges, and WHO initiatives. Front Public Health. 2017;5:276.

- European Commission. Strengthened cooperation against vaccine preventable diseases. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliaments, the Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. 2018 [accessed 2019 October 21]. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2018%3A245%3AFIN.

- World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. [accessed 2019 July 18]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE Working Group on vaccine hesitancy. 2014 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf.

- Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE). Immunization today and in the next decade. 2018 assessment report of the global vaccine action plan. 2018 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276967/WHO-IVB-18.11-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- Dube E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:1763–73.

- The Lancet Child Adolescent H. Vaccine hesitancy: a generation at risk. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019;3:281.

- Hussain A, Ali S, Ahmed M, Hussain S. The anti-vaccination movement: a regression in modern medicine. Cureus. 2018;10:e2919.

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Tracking anti-vaccination sentiment in eastern European social media networks. 2013 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.unicef.org/eca/reports/tracking-anti-vaccination-sentiment-eastern-european-social-media-networks.

- Dube E, Vivion M, MacDonald N. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14:99–117.

- Zimmerman R, Wolfe R, Fox D, Fox J, Nowalk M, Troy J, Sharp L. Vaccine criticism on the World Wide Web. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e17.

- Larson HJ. The biggest pandemic risk? Viral misinformation. Nature. 2018;562:309.

- Feldman-Savelsberg P, Ndonko F, Schmidt-Ehry B. Sterilizing vaccines or the politics of the womb: retrospective study of a rumor in Cameroon. Med Anthropol Q. 2000;14:159–79.

- Ghinai I, Willott C, Dadari I, Larson H. Listening to the rumours: what the northern Nigeria polio vaccine boycott can tell us ten years on. Glob Public Health. 2013;8:1138–50.

- Aylward RB, Heymann DL. Can we capitalize on the virtues of vaccines? Insights from the polio eradication initiative. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:773–77.

- Murakami H, Kobayashi M, Hachiya M, Khan Z, Hassan S, Sakurada S. Refusal of oral polio vaccine in northwestern Pakistan: a qualitative and quantitative study. Vaccine. 2014;32:1382–87.

- World Health Organization. Pakistan and Afghanistan: the final wild poliovirus bastion 4 January 2019. 2019 [accessed 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/pakistan-and-afghanistan-the-final-wild-poliovirus-bastion.

- Pakistan’s War on Polio Falters Amid attacks on health workers and Mistrust. The New York Times. 2019 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/29/world/asia/pakistan-polio-vaccinations-campaign.html?campaignId=7JFJX.

- Ali M, Ahmad N, Khan H, Ali S, Akbar F, Hussain Z. Polio vaccination controversy in Pakistan. Lancet. 2019;394:915–16.

- Pakistan polio: seven killed in anti-vaccination attack. BBC News. 2016 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36090891.

- Pakistan polio: mother and daughter killed giving vaccinations. BBC News. 2018 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-42738360.

- Killings of police and polio workers halt Pakistan vaccine drive. The Guardian. 2019 https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/apr/30/killings-of-police-and-polio-workers-halt-vaccine-drive-in-pakistan.

- Vanderslott S, Roser M Vaccination. 2015 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share-that-disagrees-that-vaccines-are-safe.

- Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301.

- World Health Organization. Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals - Data, statistics and graphics. 2015 [accessed 2019 Oct 17]. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/en/.

- Larson H, Wilson R, Hanley S, Parys A, Paterson P. Tracking the global spread of vaccine sentiments: the global response to Japan’s suspension of its HPV vaccine recommendation. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:2543–50.

- Gilmour S, Kanda M, Kusumi E, Tanimoto T, Kami M, Shibuya K. HPV vaccination programme in Japan. Lancet. 2013;382:768.

- Hanley SJ, Yoshioka E, Ito Y, Kishi R. HPV vaccination crisis in Japan. Lancet. 2015;385:2571.

- Ikeda S, Ueda Y, Yagi A, Matsuzaki S, Kobayashi E, Kimura T, Miyagi E, Sekine M, Enomoto T, Kudoh K. HPV vaccination in Japan: what is happening in Japan? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18:323–25.

- Trivellin V, Gandini V, Nespoli L. Low adherence to influenza vaccination campaigns: is the H1N1 virus pandemic to be blamed? Ital J Pediatr. 2011;37:54.

- Doshi P. The elusive definition of pandemic influenza. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:532–38.

- Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly. The handling of the H1N1 pandemic: more transparency needed. 2010 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. http://assembly.coe.int/CommitteeDocs/2010/20100604_H1N1pandemic_E.pdf.

- Mendel-Van Alstyne J, Nowak G, Aikin A. What is ‘confidence’ and what could affect it?: A qualitative study of mothers who are hesitant about vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36:6464–72.

- Schmitt H, Booy R, Aston R, Van Damme P, Schumacher R, Campins M, Rodrigo C, Heikkinen T, Weil-Olivier C, Finn A, et al. How to optimise the coverage rate of infant and adult immunisations in Europe. BMC Med. 2007;5:11.

- Benninghoff B, Pereira P, Vetter V. Role of healthcare practitioners in rotavirus disease awareness and vaccination - insights from a survey among caregivers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(1):138–147.

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34:1187–92.

- Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1454–68.

- Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34:6700–06.

- Ciftci F, Sen E, Demir N, Ciftci O, Erol S, Kayacan O. Beliefs, attitudes, and activities of healthcare personnel about influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:111–17.

- Black CL, Yue X, Ball SW, Fink RV, de Perio MA, Laney AS, Williams WW, Graitcer SB, Fiebelkorn AP, Lu P-J, et al. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Health Care Personnel - United States, 2017–18 Influenza Season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1050–54.

- Leung SOA, Akinwunmi B, Elias KM, Feldman S. Educating healthcare providers to increase Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rates: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Vaccine X. 2019;3:100037.

- Vorsters A, Tack S, Hendrickx G, Vladimirova N, Bonanni P, Pistol A, Metlicar T, Pasquin M, Mayer M, Aronsson B, et al. A summer school on vaccinology: responding to identified gaps in pre-service immunisation training of future health care workers. Vaccine. 2010;28:2053–59.

- Loulergue P, Moulin F, Vidal-Trecan G, Absi Z, Demontpion C, Menager C, Gorodetsky M, Gendrel D, Guillevin L, Launay O. Knowledge, attitudes and vaccination coverage of healthcare workers regarding occupational vaccinations. Vaccine. 2009;27:4240–43.

- Maltezou H, Katerelos P, Poufta S, Pavli A, Maragos A, Theodoridou M. Attitudes toward mandatory occupational vaccinations and vaccination coverage against vaccine-preventable diseases of health care workers in primary health care centers. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:66–70.

- Tuckerman J, Collins J, Marshall H. Factors affecting uptake of recommended immunizations among health care workers in South Australia. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:704–12.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Provider’s Role: importance of Vaccine Administration and Vaccine Storage & Handling. 2019 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/admin/storage/providers-role-vacc-admin-storage.html.

- Poland G, Ovsyannikova I, Jacobson R. Application of pharmacogenomics to vaccines. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:837–52.

- Deiss RG, Arnold JC, Chen WJ, Echols S, Fairchok MP, Schofield C, Danaher PJ, McDonough E, Ridore M, Mor D, et al. Vaccine-associated reduction in symptom severity among patients with influenza A/H3N2 disease. Vaccine. 2015;33:7160–67.

- Parashar UD, Nelson EA, Kang G. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children. BMJ. 2013;347:f7204.

- Preziosi MP, Halloran ME. Effects of pertussis vaccination on disease: vaccine efficacy in reducing clinical severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:772–79.

- Reich J. Of natural bodies and antibodies: parents’ vaccine refusal and the dichotomies of natural and artificial. Soc Sci Med. 2016;157:103–10.

- Attwell K, Ward P, Meyer S, Rokkas P, Leask J. “Do-it-yourself”: vaccine rejection and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Soc Sci Med. 2018;196:106–14.

- Ernst E. Rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine: reasons and consequences for vaccination. Vaccine. 2001;20(Suppl 1):S90–93. discussion S89.

- Bryden G, Browne M, Rockloff M, Unsworth C. Anti-vaccination and pro-CAM attitudes both reflect magical beliefs about health. Vaccine. 2018;36:1227–34.

- Browne M, Thomson P, Rockloff M, Pennycook G. Going against the Herd: psychological and Cultural Factors Underlying the ‘Vaccination Confidence Gap’. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132562.

- Kuntz M. The postmodern assault on science. If all truths are equal, who cares what science has to say? EMBO Rep. 2012;13:885–89.

- Diethelm P, McKee M. Denialism: what is it and how should scientists respond? Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:2–4.

- Luyten J, Desmet P, Dorgali V, Hens N, Beutels P. Kicking against the pricks: vaccine sceptics have a different social orientation. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:310–14.

- Omer S, Salmon D, Orenstein W, deHart M, Halsey N. Vaccine refusal, mandatory immunization, and the risks of vaccine-preventable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1981–88.

- Lo N, Hotez P. Public health and economic consequences of vaccine hesitancy for measles in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:887–92.

- World Health Organization. World immunization week. Vaccines and the power to protect. 2019 [accessed 2019 Sep 3]. https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-immunization-week/world-immunization-week-2019/vaccines-and-the-power-to-protect.

- Gangarosa EJ, Galazka A, Wolfe C, Phillips L, Gangarosa R, Miller E, Chen R. Impact of anti-vaccine movements on pertussis control: the untold story. Lancet. 1998;351:356–61.

- Hough-Telford C, Kimberlin D, Aban I, Hitchcock W, Almquist J, Kratz R, O’Connor K. Vaccine delays, refusals, and patient dismissals: a survey of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):1–9.

- Romanus V, Jonsell R, Bergquist S. Pertussis in Sweden after the cessation of general immunization in 1979. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:364–71.

- Antona D, Levy-Bruhl D, Baudon C, Freymuth F, Lamy M, Maine C, Floret D. Parent du Chatelet I. Measles elimination efforts and 2008–2011 outbreak, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:357–64.

- Knol M, Urbanus A, Swart E, Mollema L, Ruijs W, van Binnendijk R, Te Wierik M, de Melker H, Timen A, Hahne S. Large ongoing measles outbreak in a religious community in the Netherlands since May 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20580.

- Thornton J. Measles cases in Europe tripled from 2017 to 2018. BMJ. 2019;364:l634.

- World Health Organization. New measles surveillance data for 2019. 2019. [accessed 2019 Oct 22]. https://www.who.int/immunization/newsroom/measles-data-2019/en/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks - Measles Cases in 2019. 2019 [accessed 2020 Jan 7]. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html.

- Colzani E, McDonald SA, Carrillo-Santisteve P, Busana MC, Lopalco P, Cassini A. Impact of measles national vaccination coverage on burden of measles across 29 member states of the European Union and European Economic Area, 2006–2011. Vaccine. 2014;32:1814–19.

- Zhou F, Santoli J, Messonnier M, Yusuf H, Shefer A, Chu S, Rodewald L, Harpaz R. Economic evaluation of the 7-vaccine routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States, 2001. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1136–44.

- Filia A, Brenna A, Pana A, Cavallaro GM, Massari M, Ciofi Degli Atti ML. Health burden and economic impact of measles-related hospitalizations in Italy in 2002–2003. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:169.

- Dayan GH, Ortega-Sanchez IR, LeBaron CW, Quinlisk MP, Iowa Measles Response T. The cost of containing one case of measles: the economic impact on the public health infrastructure–Iowa, 2004. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e1–4.

- Sugerman DE, Barskey AE, Delea MG, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Bi D, Ralston KJ, Rota PA, Waters-Montijo K, Lebaron CW. Measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated population, San Diego, 2008: role of the intentionally undervaccinated. Pediatrics. 2010;125:747–55.

- Chen SY, Anderson S, Kutty PK, Lugo F, McDonald M, Rota PA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Komatsu K, Armstrong GL, Sunenshine R, et al. Health care-associated measles outbreak in the United States after an importation: challenges and economic impact. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1517–25.

- Ropeik D. How society should respond to the risk of vaccine rejection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:1815–18.

- Rosen JB, Arciuolo RJ, Khawja AM, Fu J, Giancotti FR, Zucker JR. Public health consequences of a 2013 measles outbreak in New York City. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:811–17.

- Ortega-Sanchez I, Vijayaraghavan M, Barskey AE, Wallace G. The economic burden of sixteen measles outbreaks on United States public health departments in 2011. Vaccine. 2014;32:1311–17.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of measles - San Diego, California, January-February 2008. 2008 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm57e222a1.htm.

- Wallace AS, Masresha BG, Grant G, Goodson JL, Birhane H, Abraham M, Endailalu TB, Letamo Y, Petu A, Vijayaraghavan M. Evaluation of economic costs of a measles outbreak and outbreak response activities in Keffa Zone, Ethiopia. Vaccine. 2014;32:4505–14.

- Navin M, Kozak A, Clark E. The evolution of immunization waiver education in Michigan: A qualitative study of vaccine educators. Vaccine. 2018;36:1751–56.

- Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, Paterson P. Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:1599–609.

- Suppli CH, Hansen ND, Rasmussen M, Valentiner-Branth P, Krause TG, Molbak K. Decline in HPV-vaccination uptake in Denmark - the association between HPV-related media coverage and HPV-vaccination. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1360.

- Povey M, Henry O, Riise Bergsaker MA, Chlibek R, Esposito S, Flodmark CE, Gothefors L, Man S, Silfverdal SA, Stefkovicova M, et al. Protection against varicella with two doses of combined measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine or one dose of monovalent varicella vaccine: 10-year follow-up of a phase 3 multicentre, observer-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;287–97. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2s8uwifwIwc#action=share.

- Galagan SR, Paul P, Menezes L, LaMontagne DS. Influences on parental acceptance of HPV vaccination in demonstration projects in Uganda and Vietnam. Vaccine. 2013;31:3072–78.

- Jackson C, Cheater FM, Harrison W, Peacock R, Bekker H, West R, Leese B. Randomised cluster trial to support informed parental decision-making for the MMR vaccine. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:475.

- Gowda C, Schaffer SE, Kopec K, Markel A, Dempsey AF. A pilot study on the effects of individually tailored education for MMR vaccine-hesitant parents on MMR vaccination intention. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:437–45.

- Kennedy A, Glasser J, Covello V, Gust D. Development of vaccine risk communication messages using risk comparisons and mathematical modeling. J Health Commun. 2008;13:793–807.

- Stahl J, Cohen R, Denis F, Gaudelus J, Martinot A, Lery T, Lepetit H. The impact of the web and social networks on vaccination. New challenges and opportunities offered to fight against vaccine hesitancy. Med Mal Infect. 2016;46:117–22.

- Global Vaccination Summit. Ten actions towards vaccination for all. 2019 [accessed 2019 Oct 7]. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/10actions_en.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Vaccination and trust. How concerns arise and the role of communication in mitigating crises. 2013 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/329647/Vaccines-and-trust.PDF.

- World Health Organization. Vaccine Safety Events: managing the communications response. 2013 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/187171/Vaccine-Safety-Events-managing-the-communications-response.pdf.

- Dubé E, MacDonald NE. Vaccination resilience: building and sustaining confidence in and demand for vaccination. Vaccine. 2017;35:3907–09.

- World Health Organization. Denmark campaign rebuilds confidence in HPV vaccination. 2018 [accessed 2019 Sep 30]. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/news/news/2018/3/denmark-campaign-rebuilds-confidence-in-hpv-vaccination.

- World Health Organization. Danish health literacy campaign restores confidence in HPV vaccination. 2019. [accessed 2019 Sep 30]. http://www.euro.who.int/en/countries/denmark/news/news/2019/01/danish-health-literacy-campaign-restores-confidence-in-hpv-vaccination?__scribleNoAutoLoadToolbar=true.

- Black S, Rappuoli R. A crisis of public confidence in vaccines. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:61mr61.

- Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, Heritage J, DeVere V, Salas HS, Zhou C, Taylor JA. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1998–2004.

- Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Salas HS, Devere V, Zhou C, Robinson JD. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132:1037–46.

- Williamson L, Glaab H. Addressing vaccine hesitancy requires an ethically consistent health strategy. BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19:84.

- Gagneur A, Gosselin V, Dube E. Motivational interviewing: A promising tool to address vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2018;36:6553–55.

- Australian Goverment Department of Health. Catch-up: incentives for vaccination providers and general practitioners. 2016 [accessed 2019 Dec 16]. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/catchup-incentives-vaccination-providers.pdf.

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. The organization and delivery of vaccination services in the European Union. Prepared for the European Commission. 2018 [accessed 2019 Dec 16]. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/2018_vaccine_services_en.pdf.

- Philip R, Shapiro M, Paterson P, Glismann S, Van Damme P. Is It Time for Vaccination to “Go Viral”? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:1343–49.

- Dube E, Gagnon D, Nickels E, Jeram S, Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy–country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Vaccine. 2014;32:6649–54.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2019 [accessed 2019 Oct 21]. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/.