?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Multicomponent interventions are effective in improving vaccine coverage. However, few studies have assessed their effect on timely vaccination. The aim of this study was to compare the proportion of children with vaccine delays at 2- and 12-month visits according to whether or not health centers have participated in an action research project on the organization of vaccination services for 0-5-year-olds. The action research project included a multicomponent intervention and was conducted between 2011 and 2015 in Quebec, Canada. An ecological before/after design was used for this analysis. A total of 264,579 DTaP-IPV-Hib (2-month visits) and 240,541 Men-C-C (12-month visits) vaccine doses were administered during 2011–2012 to 2014–2015 fiscal years, including 19% in 14 participating health centers and the remaining in 78 nonparticipating centers. Vaccine delays demonstrated a more pronounced decreasing trend in participating versus nonparticipating health centers (p < .0001 at 2 and 12 months). Between 2011–2012 and 2014–2015, participating centers managed to eliminate 35% of their vaccine delays at 2-month visits and 33% at 12-month visits, whereas nonparticipating centers eliminated 19% of delays at both visits. Our results are consistent with a positive impact of the multicomponent intervention, despite the fact that it had not specifically aimed at decreasing vaccine delays.

Introduction

Vaccination has eliminated or made possible to control the transmission of several vaccine-preventable diseases, in addition to limiting complications, hospitalizations, and deaths caused by related infections.Citation1,Citation2

Timeliness of childhood vaccinations remains suboptimal in many countries despite attaining high vaccine coverage.Citation3–6 Consequently, children with vaccine delays remain susceptible to vaccine-preventable diseases for a longer time, a fact that increases the risk of contracting these infections.Citation5 Vaccine delays at one or more vaccination visits before 24 months of age have also been associated with lower vaccine coverage by 24 months of age.Citation5,Citation7

Although multicomponent interventions have already demonstrated high levels of effectiveness in improving vaccine coverage, there is a limited number of published studies that examine the effect of such interventions on timely vaccination.Citation8–10 Multicomponent interventions may prove very effective in decreasing vaccine delays because a high number of risk factors are common to low vaccine coverage and noncompliance with the vaccination schedule.Citation11 However, disparities between these two indicators have already been reported in the same population, which justifies the need to obtain additional data regarding the impact of multicomponent interventions on vaccine delays.Citation4,Citation12-14

An appreciative inquiry action research project aiming to elaborate and test a multicomponent model on the Organization of Vaccination Services for 0-5-year-old children (hereinafter called OVS project) was conducted between 2011 and 2015 in 14 health centers of Quebec, Canada where the vaccination program is free of charge.Citation15,Citation16 The objective of the present analysis was to investigate the proportion of children with vaccine delays at 2- and 12-month visits according to whether or not health centers had participated in the OVS project.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We used an ecological before/after design comparing health centers participating in the OVS project with the health centers that had not.

Participation

Ninety-six (96) Health and Social Service Centers (HSSCs) existed in the province of Quebec (population roughly 8.4 million; about 84 000 births annually) between 2011 and 2015. Each HSSC provides services to a defined territory within one of the 18 health regions, including vaccination of 0-5-year-old children. Of these, 14 HSSCs in three health regions were included in the OVS project between 2011 and 2015.Citation15 These HSSCs were mainly selected on the basis of the interest expressed by their managers to invest their team in the project. All HSSCs in region A (8 out of 8) and about half of the HSSCs in regions B (1 out of 2) and C (5 out of 11) participated in the OVS project. Limited financial resources prevented the recruitment in a higher number of regions. The proportion of the population with low income (after tax)Citation17 was similar in both the participating (16%) and in the nonparticipating HSSCs (17%).

The 4 HSSCs within less populated northern health regions (Nord-du-Québec, Nunavik, Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James and Kawawachikamach) were excluded from the analysis because of differences in health services organization.

Intervention (action research project with a multicomponent intervention)

The OVS project has been previously described in the literature.Citation15 It was an action research project conducted with the Appreciative Inquiry approach and included regular coaching by the research team.Citation16 The “experimental” portion of the project corresponded to a multicomponent intervention.

Participants were asked to transform their reality to facilitate significant changes by collaborating with researchers while at the same time generating knowledge pertaining to these transformations. There is a fine line between researchers and participants. Researchers accompany the participants in their transformation process and the participants accompany the researchers in their understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The Appreciative Inquiry approach was used in order to build on existing strengths and successes.

The research team and participants (community vaccinators and immunization program managers) collaborated to collectively improve the organization of vaccination services for 0-5-year-old children. They outlined the organization of their vaccination services and helped to develop an ideal model.Citation18 This model included 109 relevant actions that were divided into nine distinct components: 1) Population; 2) Immunization promotion; 3) Resources; 4) Contact with health services; 5) Training; 6) Vaccine management; 7) Data management and use; 8) Quality of the vaccination act; 9) Environment. On average, 31 actions were already in place in each participating HSSC. Altogether, 62 actions were implemented by HSSCs, with an average of nine actions per HSSC. The most frequently implemented actions are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The chosen actions were not specifically aimed at decreasing vaccine delays but instead were those actions that were deemed relevant by a given HSSC to improve the organization of vaccination services in general.

Variables

At the time of the OVS project, the Ministry of Health and Social Services required the use of indicators for the proportion of children with timely vaccination at the 2- and 12-month visits based on immunization data recorded by HSSCs.Citation19,Citation20 Vaccinations performed in private medical clinics (approximately 25% of children at the provincial level) were excluded from these indicators.

The proportion of children with vaccine delays (at 2-month visits) can be obtained by dividing the number of children who received their first vaccination dose for diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, and Haemophilus influenza type b (DTaP-IPV-Hib) after 2 months and 14 days by the total number of children who received their first vaccination dose prior to becoming 12 months of age. For the 12-month visits, this proportion is obtained by dividing the number of children who received the meningococcal C conjugate (Men-C-C) vaccine after 12 months and 14 days by the total number of children who received this vaccination dose prior to becoming 18 months of age. The proportions of children with vaccine delays accumulated at the end of each fiscal year (April 1 to March 31) were analyzed from 2011–2012 (1st year of coaching by the researcher team) to 2014–2015 (last year of coaching by the researcher team).

A change in the definition of these indicators occurred in April 2011 and prevented the interpretation of data obtained prior to the implementation of the OVS project. Due to a major organizational change in the Quebec health care system in April 2015 and a change in the information system used to document administered vaccines, data for subsequent fiscal years (2015–2016 to 2017–2018) are presented for exploratory purposes solely using the hypothesis of a long-lasting impact beyond the end of the OSV project.

Analysis

First, all participating HSSCs in Quebec were compared to all nonparticipating HSSCs. Consequently, participating HSSCs from a given health region were compared to nonparticipating HSSCs from the same region. For region A, where all HSSCs participated, the comparison was made with the remaining 12 nonparticipating Quebec health regions.

The absolute difference in the proportion of children with vaccine delays was calculated by subtracting the proportion of children with vaccine delays in 2011–2012 from the proportion of children with vaccine delays in 2014–2015. The relative difference was calculated using the following formula:

The absolute and relative differences were then compared between participating and nonparticipating regions.

Prevalence ratios, namely ratios between the proportion of children with vaccine delays in participating and nonparticipating HSSCs, were calculated for each fiscal year. We used a log binomial regression model with a log linkCitation21 to evaluate the change in the proportion of children with vaccine delays (dependent variable) according to their participation (independent variable: yes vs no) and to the respective fiscal year (independent variable: 2011–2012 vs 2014–2015). The multiplicative change in the prevalence ratio between participating and nonparticipating HSCCs at the end (2014–2015) versus the beginning (2011–2012) of the project was then estimated. This change was estimated in this model by including an interaction term between intervention years and participation. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA), with two-sided p < .05 (Wald test) considered statistically significant.

This project consisted of secondary analyses of existing anonymous data and met the criteria for waiver of ethics review by the Université Laval research ethics board.

Results

Fourteen out of 92 HSSCs participated in the OSV project from 2011–2012 to 2014–2015 fiscal years. There were approximately 350 000 births in these 92 HSSCs. During the same period, 264,579 first doses of the DTaP-IPV-Hib vaccine (2-month visits) and 240,541 first doses of the Men-C-C vaccine (12-month visits) administered in the 92 HSSCs were recorded. The 14 participating HSSCs administered 19% of these vaccine doses at 2- and 12-month visits (49,390 and 45,637 doses, respectively).

Proportion of children with vaccine delays between 2011-2012 and 2014-2015

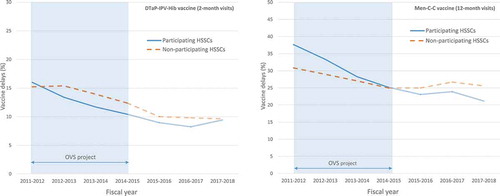

The proportions of children with vaccine delays at 2- and 12-month visits decreased more in the 14 HSSCs that participated in the OVS project than in the 78 nonparticipating HSSCs (). Between the fiscal years of 2011–2012 and 2014–2015, vaccine delays at 2-month visits decreased from 16% to 10% in participating HSSCs, whereas they decreased from 15% to 12% in nonparticipating ones (). Furthermore, at 12-month visits, vaccine delays also decreased more in participating HSSCs (from 38% to 25%) than in nonparticipating ones (31% to 25%). Vaccine delays at 12-month visits in participating HSSCs reached the levels of nonparticipating HSSCs at the end of the OVS project, although they were initially seven percentage points higher (). Between 2011–2012 and 2014–2015, participating HSSCs eliminated approximately 35% of their vaccine delays at 2-month visits and 33% at 12-month visits, whereas nonparticipating centers eliminated 19% of delays at both visits. Log binomial regression models revealed that the difference between participating and nonparticipating HSSCs was statistically significant (p < .001) both at the 2- and 12-month visits ().

Table 1. Proportion of children with vaccine delays at 2-month visits (DTaP-IPV-Hib vaccine) in participating and nonparticipating HSSCs

Table 2. Proportion of children with vaccine delays at 12-month visits (Men-C-C vaccine) in participating and nonparticipating HSSCs

Figure 1. Proportion of children with vaccine delays at 2-month visits (DTaP-IPV-Hib vaccine) and 12-month visits (Men-C-C vaccine) in participating (n = 14) and nonparticipating (n = 78) HSSCs. The proportion of children with vaccine delays (2-month visits) is obtained by dividing the number of children who received their first dose of DTaP-IPV-Hib vaccine after 2 months and 14 days by the total number of children who received their first vaccine dose prior to becoming 12 months of age. For 12-month visits, this proportion is obtained by dividing the number of children who received the Men-C-C vaccine after 12 months and 14 days by the total number of children who received this vaccine dose prior to becoming 18 months of age. Each fiscal year is from April 1 to March 31. DTaP-IPV-Hib, diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, inactivated polio, and Haemophilus influenza type b vaccine; HSSC, Health and Social Services Center; Men-C-C, Meningococcal C conjugate vaccine; OVS, Appreciative Inquiry action research project on the Organization of Vaccination Services for 0-5-year-old children, which included a multicomponent intervention

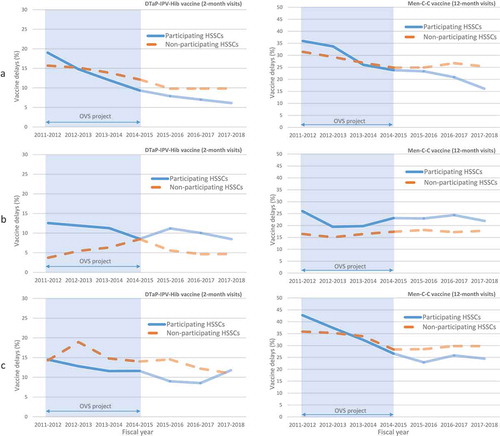

Participation in the OSV project was also associated with more favorable evolution of vaccine delays when analyzing individually each region with participating HSSCs (). At 2-month visits, participating HSSCs in regions A, B, and C eliminated 51%, 32%, and 20% of their vaccine delays, respectively, compared with 23%, −127% (increase in delays) and 19% in nonparticipating ones; differences were found to be statistically significant (). At 12-month visits, participating HSSCs in regions A, B, and C eliminated 34%, 11%, and 38% of their vaccine delays, respectively, compared with 20%, −6% (increase in delays) and 19% in nonparticipating ones; differences were also found to be statistically significant (). This more favorable trend was clearer in regions A and C (p < .001) where there were several participating HSSCs compared with region B (p = .04) where there was only one participating HSSC.

Figure 2. Proportion of children with vaccine delays at 2-month visits (DTaP-IPV-Hib vaccine) and 12-month visits (Men-C-C vaccine) (A) in region A (8 participating HSSCs versus 65 HSSCs in nonparticipating regions), (B) in region B (1 participating and 1 nonparticipating HSSC), and C) in region C (5 participating and 6 nonparticipating HSSCs). The proportion of children with vaccine delays (2-month visits) is obtained by dividing the number of children who received a first dose of DTaP-IPV-Hib vaccine after 2 months and 14 days by the total number of children who received their first vaccine dose prior to becoming 12 months of age. For 12-month visits, this proportion is obtained by dividing the number of children who received the Men-C-C vaccine after 12 months and 14 days by the total number of children who received this vaccine dose prior to becoming 18 months of age. Each fiscal year is from April 1 to March 31. DTaP-IPV-Hib, diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, inactivated polio, and Haemophilus influenza type b vaccine; HSSC, Health and Social Services Center; Men-C-C, Meningococcal C conjugate vaccine; OVS, Appreciative Inquiry action research project on the Organization of Vaccination Services for 0-5-year-old children, which included a multicomponent intervention

Exploratory analyses (2014-2015 to 2017-2018)

Since the final year of the OVS project (2015), the difference between participating and nonparticipating HSSCs regarding vaccine delays at 2-month visits has not increased (participating HSSCs: 10% in 2014–2015, 9% in 2017–2018; nonparticipating HSSCs: 12% in 2014–2015, 10% in 2017–2018). At 12-month visits, vaccine delays in participating HSSCs were decreased compared to nonparticipating ones (participating HSSCs: 25% in 2014–2015, 21% in 2017–2018; nonparticipating HSSCs: 25% in 2014–2015, 26% in 2017–2018; ).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to compare the timeliness of vaccinations at 2- and 12-month visits, depending on whether or not HSSCs had participated in the OVS project, which included a multicomponent intervention to improve the organization of vaccination services. During the period over which the OVS project occurred, improvements at 2- and 12-month visits were significantly more pronounced in participating HSSCs than in nonparticipating HSSCs. Participating HSSCs managed to decrease vaccine delays by one-third, whereas this decrease was smaller in nonparticipating HSSCs, i.e., approximately one-fifth. The evolution of vaccine delays was consistently more favorable when analyzing individually each region with participating HSSCs. Our analysis is consistent with a positive impact of the OVS project on vaccine delays, despite the fact that this project did not specifically aim at decreasing them.

Several events other than participation in the OVS project may have contributed to the overall decrease in vaccine delays observed in both groups. The introduction of provincial indicators in 2006 and the publication of the Quebec Plan for the Promotion of Immunization in 2009 may have encouraged a number of participating and nonparticipating HSSCs to implement changes in their organization of vaccination services before and during this study’s period.Citation19,Citation20,Citation22 More specifically, the Quebec Plan for the Promotion of Immunization, whose target was to improve vaccine coverage and age-appropriate vaccination, recommended the use of reminders and recall systems for 2-month visits.Citation22 This Plan could, therefore, have homogenized HSSCs practices regarding 2-month visits prior to the commencement of the OVS project, and thus limited the impact of the OVS project on vaccine delays. In the beginning of the OSV project, vaccine delays were lower at 2-month visits (~15%) compared to 12-month visits (~35%). Consequently, it was more difficult to implement significant improvements at 2-month visits. Not surprisingly, the absolute difference between participating and nonparticipating HSSCs was lower at 2-month (three percentage points) compared to 12-month visits (seven percentage points).

To our knowledge, there is only one intervention combining two or more components that has efficiently decreased vaccine delays in ambulatory settings. In this intervention performed in India, the researchers systematically observed and evaluated barriers to immunization during outreach immunization sessions.Citation6 They then proposed improvements including the recruitment of volunteers in an attempt to mobilize communities regarding vaccination, the recruitment of health care professionals including vaccinators, microplanning of immunization sessions, continuing education sessions for health workers, as well as monthly review of progress accomplished and operational problems encountered. The intervention managed to decrease vaccine delays for the 1st, 2nd and 3rd doses of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DPT) vaccine by 17, 21 and 34 days, respectively.

Two additional studies on multicomponent interventions have not proven effective to decrease vaccine delays. More specifically, LeBaron et al. in a study performed in 1992–1993, implemented a review of clinical immunization records to identify undervaccinated children and to subsequently contact their families.Citation23 Mobile van vaccinations near residences, free child care, transportation to providers and material incentives were also offered. On the other hand, Rodwald et al. in a study performed in 1994–1995, implemented a program to decrease missed vaccination opportunities in primary care offices (prompting) after using mail, phone, and home reminders of parents regarding their undervaccinated children (tracking/outreach).Citation24 In this intervention, the tracking/outreach component was effective, as it managed to decrease vaccine delays by 63 days. However, the program targeting physicians seemed to remain ineffective.

These three studies investigating the effect of multicomponent interventions on vaccine delays were performed in contexts significantly different from the one in which the OVS project was conducted. In addition, the components of the studied interventions varied greatly. The coaching provided by the researcher team to address the specific needs of participating HSSCs was a central component of the OVS project. The use of the Appreciative Inquiry approach was innovative in the field of immunization. Indeed, we identified solely one additional project that used this strategy to improve vaccination services. In this project, performed in Nepal, the organization of a three-day multi-stakeholders workshop based on the Appreciative Inquiry approach contributed significantly to declaring 823 villages (21%) and 10 districts (13%) as “fully immunized.”Citation25

This study has significant strengths. For example, it is one of the first studies that assesses the Appreciative Inquiry approach which aims at improving the organization of vaccination services. In the OVS project, participants chose the specific actions to work with as well as coaching modalities and desired level of intensity. Moreover, the evaluation covered a large number of HSSCs having administered and recorded more than 500,000 vaccines doses over a four-year period.

Our analysis is also subject to several limitations. Firstly, practical considerations forced the use of an ecological design that is unable to confirm a causal link between interventions and observed changes, since other factors may be involved. Secondly, HSSCs were selected on the basis of the interest shown by their managers. As several participating HSSCs may have been more inclined to decrease vaccine delays compared with nonparticipating HSSCs, the impact of the intervention may have been slightly overestimated. Thirdly, and following the completion of the OVS project, a centralizing reform of the Quebec health care system and significant budget cuts had a major impact on the coordination structures in public health which, in turn, led to staff shortage, including staff involved in immunization processes. Even if vaccine delays had exhibited more pronounced decreasing trends in participating HSSCs following the end of the project, this reform precluded the inclusion of 2015–2016 to 2017–2018 fiscal years in the main analysis. Fourthly, the key indicators used, namely the proportion of children with vaccine delays at 2- and 12-month visits, also have limitations. This is because these indicators fail to measure the number of days undervaccinated, which is critical in terms of assessing the potential burden of vaccine delays. The number of days undervaccinated only became available in 2015–2016 after a change in the information system. In addition, these indicators have only included vaccines administered in government-run health institutions (HSSCs). However, HSSCs provide the majority (about 75%) of vaccines administered to children across the province.Citation26 Finally, a change in the definitions for indicators prevented their use prior to the fiscal year of 2011–2012, which marked the beginning of the OVS project.

In conclusion, we observed a positive association between an action research project to improve the organization of vaccination services (including a multicomponent intervention) and timely vaccine uptake at 2- and 12-month visits. Multicomponent interventions appear to be promising in decreasing vaccine delays. Coaching community vaccinators and immunization program managers embraced the use of the Appreciative Inquiry strategy as an innovative approach to support the implementation of multicomponent interventions in the field of immunization. Studies with more robust designs are warranted to confirm the positive impact of such interventions on timely vaccination processes.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vladimir Gilca, Gaston De Serres, Danielle Auger, Eveline Toth, and Remi Gagné for their contribution to this paper. We would also like to thank Marie-France Richard for assisting us in the preparation of the manuscript. The OSV project has been funded by the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services. Finally, the authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.com) for the English language review.

References

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian immunization guide. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/canadian-immunization-guide.html.

- Schuchat A. Human vaccines and their importance to public health. Procedia Vaccinol. 2011;5:120–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.provac.2011.10.008.

- Kiely M, Boulianne N, Ouakki M, Audet D, Guay M, De Serres G, Dubé E Enquête sur la couverture vaccinale des enfants de 1 an et 2 ans au Québec en 2016. Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2018. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/2341.

- Fadnes LT, Nankabirwa V, Sommerfelt H, Tylleskär T, Tumwine JK, Engebretsen IMS. Is vaccination coverage a good indicator of age-appropriate vaccination? A prospective study from Uganda. Vaccine. 2011;29(19):3564–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.093.

- Guerra FA. Delays in immunization have potentially serious health consequences. Pediatr Drugs. 2007;9(3):143–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.2165/00148581-200709030-00002.

- Kumar R. Effectiveness of planning and management interventions for improving age-appropriate immunization in rural India. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(2):97–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.08.059543.

- Kiely M, Boulianne N, Talbot D, Ouakki M, Guay M, Landry M, Sauvageau C, De Serres G. Impact of vaccine delays at the 2, 4, 6 and 12 month visits on incomplete vaccination status by 24 months of age in Quebec, Canada. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6235-6.

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. Increasing Appropriate Vaccination: Community-Based Interventions Implemented in Combination; 2015. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccination-Community-Based-in-Combination.pdf.

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. Increasing Appropriate Vaccination: Health Care System-Based Interventions Implemented in Combination; 2015. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Vaccination-Health-Care-System-Based.pdf.

- Crocker-Buque T, Edelstein M, Mounier-Jack S. Interventions to reduce inequalities in vaccine uptake in children and adolescents aged <19 years: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71:87–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207572.

- Tauil Mde C, Sato APS, Waldman EA. Factors associated with incomplete or delayed vaccination across countries: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2016;34(24):2635–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.016.

- Heininger U, Zuberbühler M. Immunization rates and timely administration in pre-school and school-aged children. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165(2):124–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-005-0014-y.

- Stein-Zamir C, Israeli A. Age-appropriate versus up-to-date coverage of routine childhood vaccinations among young children in Israel. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2017;13(9):2102–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2017.1341028.

- Suárez-Castaneda E, Pezzoli L, Elas M, Baltrons R, Crespin-Elías EO, Pleitez OAR, de Campos MIQ, Danovaro-Holliday MC. Routine childhood vaccination programme coverage, El Salvador, 2011-In search of timeliness. Vaccine. 2014;32(4):437–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.072.

- Guay M, Clément P, Vanier C, Briand S Quel est le meilleur mode d’organisation de la vaccination des enfants de 0-5 ans au Québec? Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2016. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/2070.

- Watkins JM, Mohr BJ, Kelly R. Appreciative inquiry: change at the speed of imagination. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

- Statistics Canada. Low-income measure, after tax (LIM-AT). [accessed Jan 3]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/dict/fam021-eng.cfm.

- Guay M, Clément P, Vanier C, Briand S. Plan de mise en oeuvre du modèle optimal d’organisation des services de vaccination 0-5 ans. Québec, Canada: Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2016. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/2071.

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Proportion des enfants recevant leur 1re dose de vaccin contre le méningocoque de sérogroupe C dans les délais (anciennement 1. 01.15)- Répertoire des indicateurs de gestion en santé et services sociaux. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. http://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/repertoires/indicateurs-gestion/indicateur-000164/?&txt=proportion%20des%20enfants&msss_valpub&date=DESC.

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Proportion des enfants recevant leur 1re dose de vaccin contre DCaT-HB-VPI-Hib dans les délais (anciennement 1. 01.14)- Répertoire des indicateurs de gestion en santé et services sociaux. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. http://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/repertoires/indicateurs-gestion/indicateur-000163/?&txt=proportion%20des%20enfants&msss_valpub&date=DESC.

- Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3(1):21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-3-21.

- È D, Sauvageau C, Boulianne N, Guay M, Petit G Plan québécois de promotion de la vaccination. Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2010. [accessed 2020 Jan 3]. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/1051.

- LeBaron CW, Starnes D, Dini EF, Chambliss JW, Chaney M. The impact of interventions by a community-based organization on inner-city vaccination coverage: fulton County, Georgia, 1992-1993. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(4):327–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.152.4.327.

- Rodewald LE, Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Barth R, Kraus R, Raubertas RF. A randomized study of tracking with outreach and provider prompting to improve immunization coverage and primary care. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):31–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.103.1.31.

- Khanal S. Progress toward measles elimination — Nepal, 2007–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(8):206–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6508a3.

- Boulianne N, Audet D, Ouakki M, Dubé E, De Serres G, Guay M. Enquête sur la couverture vaccinale des enfants de 1 an et 2 ans au Québec en 2014. Québec, Canada: Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2015. accessed 2020 Jan 3. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/1973.