ABSTRACT

Background: 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) has been used to prevent pneumococcal disease, and PPSV23 became available in 2003 in Hangzhou, China as a private-sector, vaccinee-chosen vaccine. No national guidelines for PPSV23 have been developed. We analyzed PPSV23 coverage and utilization in Hangzhou to determine patterns of PPSV23 use and the occurrence of adverse events following immunization (AEFI) in Hangzhou.

Materials and Methods: Individuals over 2 years of age in Hangzhou were included. Vaccination data during 2006–2017 was retrieved from Hangzhou’s Immunization Information System (HZIIS). We used descriptive epidemiological methods to determine PPSV23 usage patterns and AEFI occurrence.

Results: In 2017, there were 9,027,973 persons above 2 years of age with the coverage of PPSV23 of 2.98%. The coverage of PPSV23 among elders ranged from 0.17% to 0.69%, and the overall coverage was higher in urban areas (3.70%) than in rural (3.34%) and suburban areas (2.16%). 93.45% of 268957 recipients were vaccinated with PPSV23 at 2–4 years of age. 394 AEFI of PPSV23 cases were reported to the Chinese national adverse event following immunization information system (CNAEFIS) during 2008–2017, with the reporting rate of 140.39 per 100,000 doses.

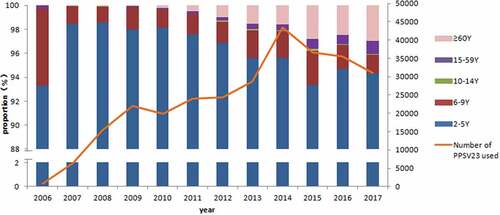

Conclusion: Persons in Hangzhou had overall low PPSV23 vaccination coverage especially for adults. Most of PPSV23 were used in children, while the proportion of the old population over 60 years slightly increased over year. PPSV23 was safe with a low reported AEFI rate, which was a little higher for children than for the elderly (over 60 years).

1. Introduction

Pneumococcal infections caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) may cause some serious illness, including meningitis, bacteremia, and pneumonia. S. pneumoniae is the leading cause of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). So far, more than 90 serotypes of S. pneumoniae have been detected. Before pneumococcal conjugate vaccines have been developed, 6–11 serotypes accounted for 70% of all IPD found in children worldwide.Citation1 In China, IPD is among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, especially among infants under two, adults over 65 years of age and individuals with immunocompromising diseases and other chronic conditions.

Vaccination has shown to be very effective in controlling PD in many developing countries.Citation2–3 Currently, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) has been used to prevent IPD among children. Before that, 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) has been used to prevent pneumococcal disease in China since 1998. PPSV23 produced by four vaccine manufacturers have ever been available in China, including 2 PPV23 produced by Merck and Sanofi Pasteur and 2 PPV23 produced by the Chengdu Institute of Biological Products and Yuxi Walvax Biotechnology Company of China.Citation4 In 2003, PPSV23 became available in Hangzhou; nonetheless, it was not included into Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI). Yet, so far, no national guidelines for PPSV23 have been developed. According to the vaccine specification, in Hangzhou, PPSV23 has been designed for patients who are 50 years or older and infants older than 2 years at increased risk of pneumococcal disease, and one dose PPSV23 is re-vaccination if someone need > 5 years. PPSV23 vaccination is carried out voluntarily and at one’s own expense.

In the present study, we determined the coverage of PPSV23, patterns of PPSV23 usage, and occurrence of adverse events following immunization (AEFI) in Hangzhou between 2006 and 2017.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Setting

Hangzhou is an economically developed city in Zhejiang Province of China, with a population of about 9,100,000. The census data were obtained from the information system of the National Center for Disease Prevention and Control. It consists of 16 districts, 6 of which are classified as urban areas (Shangcheng, Xiacheng, Jianggan, Gongshu, Xihu, and Xihufengjingmingsheng); 5 are suburb areas (Binjiang, Xiaoshan, Yuhang, Xiasha, Dajiangdong); while all other areas (Fuyang, Linan, Tonglu, Jiande, Chunan,) are considered rural areas. In Hangzhou, vaccinations were given only at vaccination clinics, and there are approximately 200 vaccination clinics in the city. Since 2005, Hangzhou Center for Disease Control and Prevention (HZCDC) created Hangzhou Immunization Information System (HZIIS), which is a computerized information system that contains immunization data and vaccine’s demographic information for Hangzhou, and supplementary entry of vaccination records since 2000.

The Chinese national adverse event following immunization information system (CNAEFIS) is a passive surveillance system, which is the only and official vaccine safety surveillance system that collects AEFI cases in mainland China. AEFI were damages caused by the body tissues and organs, function, and suspected to be connected with vaccination response occurred in the process of vaccination or after vaccination.According to the causes, it can be divided into adverse reactions (including general reactions and abnormal reactions), vaccine quality accident, implementation error accident, coincidences and psychogenic reactions.

2.2. Target population

Individuals registered in HZIIS who received PPSV23, including children and adults.

2.3. Data resources

We conducted a cross-sectional study. The demographic information and the immunization records of PPSV23 of the target population from 2006 to 2017 were extracted from HZIIS on Dec 31, 2017. The demographic information included name, sex, birth date, current address. The census data were obtained from the information system of the National Center for Disease Prevention and Control . The information of AEFI after PPSV23 vaccination was collected from CNAEFIS, including date of report, age and sex of patient, kind and lot of suspect vaccine(s), description of the AEFI, the outcome of AEFI, et al.

2.4. Data analysis

The basic information from individuals who received PPSV23 were described. The coverage of PPSV23 was estimated and the determinants on vaccination of PPSV23 were also explored. PPSV23 AEFI per 100,000 populations was calculated by using the number of PPSV23 AEFI cases divided by the number of PPSV23 recipients. All statistical analyzes were performed and graphs created, using SPSS statistical software for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A value of P < .05 (2-sided) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. PPSV23 coverage

In 2017, the total population size of Hangzhou was 9,103,259. At the end of 2017, there were 9,027,973 persons above 2 years of age among whom 4,606,062 (51.02%) were males, and 4,421,911 (48.98%) were females Individuals who registered in HZIIS and received PPSV23 from 2006 to 2017 were 268,957, among whom 141,434 (52.59%) were males, and 127,523 (47.41%) were females.

The coverage of PPSV23 among persons above 2 years of age was 2.98%, while the highest coverage of 53.94% was observed among children aged 4 years, followed by 51.04% among children aged 5 years and 44.38% among children aged 6 years. The coverage of PPSV23 among elders ranged from 0.17% to 0.69%. The coverage was higher in males (3.07%) than in females (2.88%). The trends of coverage observed in males or females were similar to that in the general population (). The coverage in the urban areas was higher than in the rural areas and suburban areas, especially in children under 14 years old ().

Table 1. Coverage rates of PPSV23 by age and sex in Hangzhou in 2017

Table 2. Coverage rates of PPSV23 by age and living area in Hangzhou in 2017

3.2. Age of PPSV23 vaccination

Totally, 93.45% of 268957 recipients were vaccinated with PPSV23 at 2–4 years of age; 2 years of age was the main vaccination age that accounted for 75.72%. However, only 1.52% of recipients were vaccinated with PPSV23 at 60 years of age or above (). The number of those using PPSV23 increased by year and peaked in 2014, and then maintained a high level at 30,000 to 40,000 each year until the end of this study. The proportion of PPSV23 vaccination age changed with years. 2–5 years were still the main vaccination age, while the proportion of the old population over 60 years slightly increased over year ().

Table 3. Age distribution of PPSV23 vaccination in Hangzhou

3.3. AEFI of PPSV23

There were 394 AEFI of PPSV23 cases reported to CNAEFIS during 2008–2017, with the reporting rate of 140.39 per 100,000 doses. Of these, 372 were common adverse reactions, 10 were rare adverse reactions, and the other 12 were coincidental events. Of the 10 rare adverse reactions, 6 were anaphylactic rashes, 2 were febrile convulsions, and 2 were cellulitis. Reporting rates of those three classifications of PPSV23 AEFI were 132.55 per 100,000 doses, 3.56 per 100,000 doses, and 4.28 per 100,000 doses, respectively. The PPSV23 AEFI reporting rate was higher for children under 10 years old than the elderly over 60 years. ()

Table 4. Classification of reported PPSV23 AEFI Cases by vaccination age during 2008–2017

4. Discussion

Our results showed that the coverage of PPSV23 in Hangzhou was low, especially among adults; 2–5 years were the main vaccination age, while the proportion of the old population over 60 years slightly increased over year; approximately half of children 2–5 years of age received PPSV23 while fewer than 1% of adults over 60 years of age have been vaccinated with PPSV23. PPSV23 was used more often in urban areas than in rural and suburban areas. Besides, our data showed that the reported rate of PPSV23 AEFI was low, but it was higher for children than for the elderly (over 60 years).

Since the introduction of PPSV23 as a non-EPI vaccine in Hangzhou, significant gaps in pneumococcal vaccine coverage persisted. In 2014, in the United States, 61.3% of adults aged 65 years and older received their recommended pneumococcal vaccines and the coverage among high-risk adults aged 19–64 years (smokers or those with chronic conditions such as diabetes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) was 20.3% .Citation5 The coverage of PPSV23 in Hangzhou was much lower than in the United States, and it was higher in children than in the elderly. The difference between the coverage in the two countries would due to the different recommendations for use of the vaccine:in the United States, it was never recommended for routine use among children, but was recommended for decades for elderly adults,while PPSV23 as a non-EPI vaccine in Hangzhou, China. Higher uptake among children may be due to more opportunity for children’s guardians to learn of the PPSV23 vaccination service during their children EPI program. Since the EPI clinicians were introducing the knowledge of pneumococcal vaccine in the daily publicity of vaccination, so as to raise parents’ awareness of vaccination. Consensus with the hazards of pneumonia, the safety of vaccination and advice on PPSV23 vaccination provided by family members may be the main factors influencing the older adults to receive PPSV23 vaccination .Citation6 In addition, older people typically visited the Community Health Center (CHC) in their residential districts, thus, systematic encouragement from healthcare physicians might be essential for increasing PPSV23 vaccination. Furthermore, people in suburb areas and the rural areas received less PPSV23 vaccination than those in urban areas due to economic reasons and vaccination awareness. an epidemiological study that was conducted to identify factors associated with the PPV23 in a large cohort of community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan showed that older adults who were female and current smokers were less likely to receive the PPV23.Citation7 Therefore, these population groups should be the primary targets of public health efforts to promote pneumococcal vaccination. Together with already established influencing aspects, including financial or health service delivery factors, our results may provide a basis for developing vaccination policy models that would achieve and maintain a high uptake of pneumococcal vaccination.

PPSV23 was developed to prevent PD in adults and people older than 2 who have certain underlying medical conditions.Citation8 In Hangzhou, PPSV23 was primarily administered to children between 2 and 4 years old, while very few of elderly persons (over 60 years old) received the vaccination. The incidence rate of PD increases with age. It has been estimated that the number of elderly will double between 2015 and 2050 (from 900 million to 2.1 billion) ;Citation9 thus, PD in older adults may become a significant public health concern in the future. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the vaccine effectiveness of PPSV23 in preventing IPD and all-cause CAP in the general population 50 years of age and older was 50%-54% and 4%-17%.Citation10 PPSV23 can minimize the severity of CAP among hospitalized patients and reduce the burden of other pneumococcal diseases. Vaccination with PPV23 is cost-effective and in some cases, a cost-saving strategy for the prevention of IPD in adults.Citation11 In Shanghai, China, the cost-effectiveness of adding PPSV23 to the immunization schedule for the elderly population (>60 years) was evaluated by using a decision-tree model. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of PPSV23 vaccination compared with no vaccination was 16,699 USD/quality-adjusted life years gained, which was lower than the per capita GDP of Shanghai ($16,840).Citation12 Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides are T-cell independent antigens, which makes them poorly immunogenic in those aged <2 years. In contrast to PPSV23, PCV was immunogenic in young children; it can reduce carriage of vaccine serotype pneumococcus and thus induce indirect protection. Following WHO’s suggestion, PPSV23 should be recommended to older adults instead of healthy children.

According to the data from pre-licensure clinical trials and other post-licensure studies, PPSV23 has a good safety profile. In the United States, reports submitted to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) following PPSV23 from 1990 to 2013 showed that injection site erythema and injection site pain were the most commonly reported non-serious adverse events, while fever was most commonly reported serious adverse event.Citation13 Moreover, an active surveillance of PPSV23 AEFI was conducted among 121,255 participants in China; the incidence of local adverse reaction was 0.34%, and the systemic adverse reaction was 0.29%.Citation14 Compared to the AEFI cases reported in China in 2014,Citation15 the incidence of total AEFI, common adverse reactions and rare adverse reactions in Hangzhou were all higher, mainly due to the sensitivity of the AEFI surveillance system. The safety profile of PPSV23 in children is similar to that in adults;Citation16 nevertheless, in our study, the reported rate of PPSV23 AEFI in children was higher than in the older population over 60 years. The reason may be that more attention was paid to the children’s health condition than to the elderly. In addition, 94.42% of PPSV23 AEFI reported in our study were common adverse reactions. Further studies of active surveillance of PPSV23 AEFI are necessary to reveal the real differences in incidence between children and the elderly.

The strength of the present study was the use of HZIIS for data collection. HZIIS is a modern surveillance system that maintains all immunization data, which were collected after the persons contacted an immunization clinic. In addition, AEFI of PPSV23 cases were sensitively detected by CNAEFIS. Yet, this study has one limitation: it did not include people not registered in HZIIS, but we compared with the usage amount of PPSV23, the vaccination number in HZIIS was similar.

5. Conclusions

Persons in Hangzhou had overall low PPSV23 vaccination coverage, and most of PPSV23 were used in children. an integrated strategy that includes both PPSV23 and PCV should be recommended for the control and prevention of IPD. Education on pneumococcal diseases and PPSV23 vaccination should be used to increase the coverage, especially among those indicated populations. In addition, a national guideline for PPSV23 vaccination should be established in China. Further studies of active surveillance of PPSV23 AEFI are necessary to detect the differences of AEFI incidence between children and the elderly.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Ethical considerations

This study was determined to be exempt from ethical review by the Hangzhou CDC institutional review board. Data were de-identified when extracted from HZIIS and were not linked to individual identifiers.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the staff at county level Center for Disease Control and Prevention and in vaccination clinics in Hangzhou, for their vaccination service.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Johnson HL, Deloria-Knoll M, Levine OS, Stoszek SK, Freimanis Hance L, Reithinger R, Muenz LR, O’Brien KL. Systematic evaluation of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease among children under five: the pneumococcal global serotype project. PLoS Med. 2010;7(10):pii: e1000348. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000348.

- WHO.23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine: WHO position paper, October 2008, WER 2008, vol.83.p. 737–384.

- WHO. Meeting of the immunization strategic advisory group of experts, November 2007 – conclusions and recommendations. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2008;83(1):1–15.

- Wang HQ, an ZJ. Expert consensus on immunization for prevention of pneumococcal disease in China (2017) . Chin J Epidemiol. 2018;39:111–38.

- Williams WW, Lu PJ, O’Halloran A, Kim DK, Grohskopf LA, Pilishvili T. Surveillance of vaccination coverage among adult populationsÐUnited States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(1):1± 36. PMID:26844596. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6501a1.

- Liu S, Xu E, Liu Y, Xu Y, Wang J, Du J, Zhang X, Che X, Gu W. Factors associated with pneumococcal vaccination among an urban elderly population in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(10):2994–99. doi:10.4161/21645515.2014.972155.

- Chen CH, Wu MS, Wu IC. Vaccination coverage and associated factors for receipt of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in Taiwan. Medicine. 2018;97(5):e9773. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000009773.

- Wang Y, Jingxin L, Wang, Yuxiao Y, Gu W, Zhu F. Effectiveness and practical uses of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in healthy and special populations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(4):1003–12. doi:10.1080/21645515.2017.1409316.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World population prospects: the 2015 revision, key findings & advance tables. Working paper no. ESA/P/WP.241. 2015 [accessed 2016 Nov 3]. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/key_findings_wpp_2015.pdf

- Kraicer-Melamed H, O’Donnell S, Quach C. The effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 (PPV23) in the general population of 50 years of age and older: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2016;34(13):1540–50. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.024.

- Ogilvie I, Khoury AE, Cui Y, Dasbach E, Grabenstein JD, Goetghebeur M. Cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in adults: A systematic review of conclusions and assumptions. Vaccine. 2009;27(36):0–4904. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.061.

- Zhao D, Gai Tobe R, Cui M, He J, Wu B. Cost-effectiveness of a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine immunization programme for the elderly in Shanghai, China. Vaccine. 2016;34(50):6158–65. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.003.

- Miller ER, Moro PL, Cano M, Lewis P, Bryant-Genevier M, Shimabukuro TT. Post-licensure safety surveillance of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 1990–2013. Vaccine. 2016;34(25):2841–46. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.021.

- Zhang M, Zhou BL, Li W. Safety investigate of 23- valent pneumococcal poly saccharide vaccine . J Preventive Med Inf. 2013;29(9):798–800.

- Ye JK, Li KL, Xu DS. Analysis of surveillance for adverse events following immunization in China, 2014. Chin J Vaccines Immunization. 2016;22(2):125–37.

- Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA. Vaccines [M]. 7th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier; 2018. p. 835.